Abstract

Background

This study examined the changes in the lipidome and associations with immune activation and cardiovascular disease (CVD) markers in youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus (YPHIV).

Methods

The serum lipidome was measured in antiretroviral therapy (ART)–treated YPHIV (n = 100) and human immunodeficiency virus–uninfected children (n = 98) in Uganda. Plasma markers of systemic inflammation, monocyte activation, gut integrity, and T-cell activation, as well as common carotid artery intima media thickness and pulse wave velocity (PWV), were evaluated at baseline and 96 weeks.

Results

Overall, median age was 12 years, and 52% were females. Total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein were similar between the groups; however, the concentrations of ceramides, diacylglycerols, free fatty acids, lysophosphatidylcholines, and phosphatidylcholines were higher in YPHIV (P ≤ .03). Increases in phosphatidylethanolamine (16:0 and 18:0) correlated with increases in soluble CD163, oxidized LDL, C-reactive protein, intestinal fatty acid binding protein, and PWV in YPHIV (r ≥ 0.3).

Conclusions

YPHIV successfully suppressed on ART have elevated lipid species that are associated with CVD, specifically palmitic acid (C16:0) and stearic acid (C18:0).

Keywords: lipids, cardiovascular disease, inflammation, immune activation, perinatally acquired HIV

Youth with perinatally acquired HIV in Uganda with viral suppression have evidence of lipidome alterations. Changes in palmitic and stearic acid are associated with increased inflammation and cardiovascular disease risk.

Wide access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from a fatal condition into a chronic disease. Today, there are approximately 5.1 million adolescents and young adults with HIV aged ≤25 years—millions with perinatally acquired HIV—most of whom (78%) reside in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Non-AIDS events such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) are becoming major causes of mortality and morbidity in adults with HIV [2, 3] and are threatening the success of ART.

Dyslipidemia is traditionally assessed with high-abundance lipids. New methods have been developed that allow for a finer characterization of these elements. “Lipidomics” is a branch of metabolomics and applies to studying lipid metabolism on a broad scale. Lipids are a diverse group of biomolecules that can store energy, activate genes, and modulate signaling pathways [4]. Current advancements in mass spectrometry allow the discovery and study of low-abundance lipids, which may circulate at micromolar or nanomolar blood levels [5].

Lipid species provide information about the total number of carbons and double bonds or saturation. Medium-sized saturated lipid classes and specifically ceramides (CERs), cholesterol esters (CEs), diacylglycerols (DAGs), sphingomyelins (SMs), and the phospholipids phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) are known to be associated with increased risk of CVD [6–8]. Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, on the other hand, are known to be cardioprotective [9].

HIV replication, its treatment with ART, and the inflammatory consequences of HIV infection all contribute to perturbations in metabolic and lipid profiles [10, 11]. Despite having similar traditional lipid panels, adults with HIV have elevated total free fatty acid levels compared to seronegative adults [12], and lipids with saturated chains have shown an association with increased risk of carotid artery plaque as measured by intima media thickness (IMT) over time [13]. The pathophysiological contributions of individual lipid species on CVD and inflammation in youth with perinatally acquired HIV (YPHIV) are largely unknown. In addition, there are unique differences in HIV and ART exposure (in utero) and treatment during periods of critical development that may exacerbate comorbidities in this population and lead to divergent mechanistic pathways compared to adults. We have previously reported in a pilot study lipidome differences between YPHIV and HIV-negative (HIV–) youth (N = 20) [14]. The current study investigates further the lipidomic signatures in the larger Ugandan cohort to (1) identify lipid perturbations specifically associated with HIV compared to lipid profiles in HIV– youth, (2) determine whether alterations in the lipidome are associated with systemic inflammation and immune activation in YPHIV, and (3) elucidate whether alterations in proinflammatory lipid pathways are associated with subclinical vascular disease in YPHIV over 96 weeks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This is a longitudinal analysis of data at baseline and 96 weeks later, from an observational cohort study of YPHIV and HIV– children prospectively enrolled at the Joint Clinical Research Center in Kampala, Uganda, as previously described [15, 16]. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Ugandan National Council of Science and Technology as well as the institutional review board of the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio. Caregivers gave written informed consent, and participants provided written informed assent as per research guidelines in Uganda. Inclusion criteria included ages between 10–18 years; those with active coinfections (malaria, tuberculosis, helminthiasis, pneumonia, and meningitis) as well as malnutrition or diarrhea in the last 3 months, those with pregnancy or intent to become pregnant, and those with diabetes or heart disease were excluded. YPHIV participants were on ART for at least 2 years with a stable regimen for at least the last 6 months with HIV-1 RNA <400 copies/mL. HIV– children were tested during clinic visits to confirm HIV-seronegative status.

Study Evaluations

Blood was drawn after an 8-hour fast. Blood was processed and serum, plasma, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs, both collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes) were cryopreserved for shipment to University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Ohio.

Cellular Markers of Monocyte and T-Cell Activation

Monocyte and T cells were phenotyped by flow cytometry [15]. CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation was defined as expression of CD38 and/or HLA-DR. Monocyte subset proportions were determined by the relative expression of CD14 and CD16.

Inflammation, Soluble Immune Activation, and Gut Markers

Biomarkers were selected based on prior data from YPHIV individuals in Uganda [17] as well as from adults with HIV showing association with CVD and other end organ diseases. Soluble CD14 (sCD14, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota) is a soluble marker of monocyte activation. Plasma markers of monocyte activation (soluble CD163 [sCD163]), systemic inflammation (soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), interleukin 6, and oxidized lipids (oxidized low-density lipoprotein [OxLDL]) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems; ALPCO, Salem, New Hampshire; and Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden). The intra-assay variability ranged between 4% and 8% and interassay variability was less than 10% for all markers. All assays were performed at the laboratory of N. T. F. at Ohio State University, Columbus. Laboratory personnel were blinded to group assignments and timepoints of the study evaluations.

Subclinical Vascular Disease

Intima media thickness and pulse wave velocity (PWV) measurements were performed in a standardized fashion as previously described [16].

Lipidomic Analysis

Lipidomic analysis of fasting serum samples was performed using the Sciex Lipidyzer platform (Sciex, Framingham, Massachusetts) [14]. Lipidyzer is a validated platform for quantitative lipidomics that utilizes a 5500 QTRAP-MS with SelexION differential ion mobility technology for sensitive and selective lipid analysis of the following lipid classes: CE, CER, DAG, dihydroceramide (DCER), free fatty acid (FFA), hexosylceramide (HCER), lactosylceramide (LCER), lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE), PC, PE, SM, and triacylglycerol (TAG). Approximately 1100 blood lipids spanning 13 lipid classes were profiled and quantitated using optimized mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry transitions for the targeted serum lipid species in addition to the stable isotope-labeled internal standards used for quantification. Results were expressed as concentration (µmol) of individual lipid species, of lipids grouped by class, and as composition or %mol contribution to the sum of all measured lipids. Lipidome assays were performed in the Nutrient and Phytochemical Analytic Shared Resource at Ohio State University.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were described using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. Baseline differences between YPHIV and HIV– children were determined using the χ2 test for categorical measures and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous measures. Differences in lipid class composition and concentration between YPHIV and HIV– at baseline were assessed using 2-sample t test, and dot plots were used to illustrate these differences. Comparisons of the average changes in these measures from baseline to 96 weeks between the 2 groups were assessed using a paired t test, and the average trends over time were shown using line plots stratified by group. In a subgroup analysis of YPHIV, effect modification of lipid composition and concentration by integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) medication change during the study period was investigated using a mixed-effects model with an interaction between time and INSTI medication change. Normality and homoscedasticity assumptions of statistical tests were satisfied using Q-Q plots and residual plots, where appropriate. Associations between changes in lipid levels and changes in immune activation markers and CVD measures were analyzed using Spearman correlations. To aid in the visualization of the complex relationships between all lipid species (as described in the lipidomic section) and biological markers, relevance network graphs were created using Gephi 0.10.1. We required that the correlation coefficients presented in the graphs met the following criteria: (1) at least 50% of the data were nonmissing, and (2) the correlation coefficient was ≥|0.4| for immune activation markers or ≥|0.3| for CVD measures. For CVD measures, the 0.3 cutoff was chosen because all correlations were <0.4. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate method. Significance was assessed at the .05 level and all other analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 software.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics are highlighted in Table 1. A total of 198 participants were included (100 YPHIV and 98 HIV–). Median age was 13 (IQR, 11.4–14.4) years, and 52% of participants were female. Overall, median body mass index (BMI) was 17.8 (IQR, 15.9–19.2) kg/m2. Among YPHIV, median CD4 cell count was 988 (IQR, 631–1210) cells/μL. At baseline, 84% YPHIV had viral load <50 copies/mL and remained undetectable at week 96. At baseline, 64% were on a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor–containing regimen, 28% were on lopinavir/ritonavir, and 2 participants were on dolutegravir; 72% had a past history of thymidine exposure (zidovudine, stavudine, didanosine). During the 96-week study period, 53% of participants had drug substitutions, 85% of whom switched to lamivudine, tenofovir, and dolutegravir for regimen optimization based on the Ugandan Ministry of Health HIV guidelines [18].

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | YPHIV (n = 100) |

HIV-Negative Children (n = 98) | Total (n = 198) |

P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 12.9 (11.5–14.7) | 12.7 (11.2–14.3) | 12.9 (11.4–14.4) | .399 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 53 (53.0) | 51 (52.0) | 104 (52.5) | .910 |

| HIV-related variables | ||||

| VL <20 copies/mL, No. (%) | 84 (84.0) | … | … | |

| CD4+ count, cells/µL | 988.0 (631.0–1310.0) | … | … | |

| CD4% | 34.5 (27.0–41.0) | … | … | |

| CD4+ count nadir, cells/μL | 631.0 (336.0–1113.0) | … | … | |

| ART duration, y | 9.9 (7.6–11.1) | … | … | |

| ART regimen, No. (%) | ||||

| NRTI | ||||

| Abacavir | 42 (42) | … | … | |

| Lamivudine | 1 (1) | … | … | |

| Tenofovir | 12 (12) | … | … | |

| Zidovudine | 33 (33) | … | … | |

| Nevirapine | 18 (18) | … | … | |

| Efavirenz | 46 (46) | … | … | |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 27 (28) | … | … | |

| Lifetime exposure to thymidine analogue, No. (%) | 72 (72) | … | … | |

| CVD and metabolic parameters | ||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 17.7 (15.8–19.1) | 18.0 (16.2–19.5) | 17.8 (15.9–19.2) | .497 |

| Waist:hip ratio | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | .041 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 107.0 (101.0–113.5) | 115.0 (106.0–122.0) | 111.0 (103.0–118.0) | .001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 65.0 (60.0–71.0) | 66.5 (62.0–73.0) | 66.0 (61.0–72.0) | .164 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 154.0 (134.0–173.0) | 148.0 (130.0–170.0) | 149.0 (132.5–171.0) | .517 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 48.0 (41.2–57.6) | 44.6 (38.3–54.1) | 46.1 (39.9–55.3) | .091 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 84.5 (68.0–104.0) | 83.0 (69.0–105.0) | 83.0 (69.0–104.0) | .798 |

| VLDL, mg/dL | 19.0 (13.0–23.0) | 17.0 (12.0–21.0) | 18.0 (13.0–22.0) | .121 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 93.0 (65.0–115.0) | 83.0 (62.0–105.0) | 88.0 (63.5–109.0) | .121 |

| HOMA | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | 1.1 (0.8–1.8) | .045 |

| Mean IMT, mm | 0.53 (0.49–0.55) | 0.51 (0.47–0.54) | 0.52 (0.48–0.54) | .067 |

| Max IMT, mm | 0.63 (0.60–0.68) | 0.60 (0.57–0.63) | 0.61 (0.59–0.65) | .001 |

| Pulse wave velocity, m/s | 5.7 (5.4–6.3) | 6.0 (5.5–6.6) | 5.8 (5.5–6.5) | .242 |

| Soluble markers of systemic inflammation and monocyte activation | ||||

| sCD14, pg/mL | 2113.8 (1755.0–2570.1) | 1675.4 (1446.6–1951.6) | 1874.94 (1556.1–2302.4) | <.001 |

| sCD163, ng/mL | 584.1 (401.6–737.0) | 685.7 (496.4–855.4) | 643.5 (453.8–797.4) | .033 |

| Zonulin, ng/mL | 6.1 (4.8–7.8) | 6.8 (5.5–8.4) | 6.6 (5.2–8.1) | .074 |

| I-FABP, pg/mL | 2139.2 (1701.7–3251.7) | 2255.8 (1696.4–3103.1) | 2199.0 (1699.0–3177.0) | .759 |

| BDG, pg/mL | 285.1 (230.5–490.0) | 448.7 (292.1–615.4) | 327.4 (257.6–547.6) | <.001 |

| hsCRP, ng/mL | 518.9 (186.0–1692.2) | 367.8 (128.1–1124.2) | 426.6 (164.3–1360.9) | .229 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 1.1 (0.8–2.1) | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 1.2 (0.8–2.0) | .910 |

| OxLDL | 40 065.1 (34 013.6–47 590.8) | 44 737.6 (37 387.9–52 520.8) | 42 530.4 (35 232.6–50 648.3) | .046 |

| sTNFRI, pg/mL | 905.4 (731.5–1034.3) | 959.9 (807.5–1111.4) | 936.4 (778.8–1081.2) | .040 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; BDG, Beta D Glucan; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, low-density lipoprotein; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HOMA, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; IMT, intima media thickness; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; OxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; sCD14, soluble CD14; sCD163, soluble CD163; TNFRI, Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I; VL, viral load; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; YPHIV, youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus.

aDifferences between groups calculated using χ2 test for categorical measures and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous measures.

Median ART duration was 10 years; all YPHIV were on cotrimoxazole for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis based on Ugandan HIV guidelines [18], and none of the participants were receiving tuberculosis medications. In dietary questionnaires, 85% of all participants stated using palm oil as the primary oil consumed.

The Lipidome

At baseline, total cholesterol, LDL, and high-density lipoprotein were similar between the groups; however, the composition and concentration of several lipid classes were higher in the YPHIV (Table 2). At baseline, the composition of total lipids was enriched for LCER (P = .004), LPC (P = .001), and PC (P = .018); saturated fatty acids were also significantly elevated in YPHIV. Lipid concentrations of CER (P < .001), DAG (P < .001), LPC (P < .001), and PC (P < .001), as well as lipid classes that contain saturated fatty acids, are shown in Figure 1 and were significantly higher among YPHIV compared to levels in adolescents without HIV. To note, LPC and PC composition and concentrations were both higher in YPHIV at baseline.

Table 2.

Comparison of Lipid Class Composition and Concentration Between Groups at Baseline

| Lipid Class | Lipid Composition, mol % | Lipid Concentrations, µmol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YPHIV | HIV-Negative Children | P Valuea | YPHIV | HIV-Negative Children | P Valuea | |

| CE | 38.48 (37.60–39.36) | 37.45 (36.02–38.87) | .341 | 3122.29 (2985.55–3259.03) | 3080.39 (2950.16–3210.62) | .774 |

| CER | 0.09 (0.09–0.09) | 0.09 (0.08–0.09) | .798 | 7.39 (6.99–7.79) | 6.28 (5.96–6.60) | <.001 |

| DAG | 0.43 (0.40–0.46) | 0.45 (0.42–0.48) | .497 | 34.81 (32.08–37.54) | 27.47 (25.32–29.62) | <.001 |

| DCER | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | .732 | 0.60 (0.56–0.63) | 0.56 (0.53–0.59) | .263 |

| FFA | 11.90 (11.14–12.66) | 13.41 (11.82–15.00) | .162 | 1023.54 (950.80–1096.28) | 1135.40 (1068.95–1201.84) | .065 |

| HCER | 0.05 (0.05–0.06) | 0.05 (0.05–0.06) | .732 | 3.75 (3.52–3.97) | 3.96 (3.73–4.19) | .308 |

| LCER | 0.041 (0.039–0.043) | 0.037 (0.035–0.039) | .015 | 2.99 (2.83–3.15) | 3.05 (2.88–3.22) | .750 |

| LPC | 3.75 (3.57–3.94) | 3.31 (3.11–3.51) | .006 | 301.62 (283.82–319.41) | 253.34 (240.24–266.44) | <.001 |

| LPE | 0.04 (0.04–0.04) | 0.06 (0.02–0.11) | .451 | 2.92 (2.69–3.14) | 2.86 (2.63–3.09) | .798 |

| PC | 24.09 (23.25–24.93) | 22.87 (22.32–23.43) | .047 | 1904.11 (1833.07–1975.15) | 1671.05 (1604.26–1737.85) | <.001 |

| PE | 1.62 (1.53–1.71) | 1.99 (1.39–2.58) | .341 | 128.11 (120.19–136.03) | 124.41 (117.30–131.51) | .627 |

| SM | 6.92 (6.55–7.29) | 7.08 (6.63–7.54) | .725 | 644.07 (606.50–681.64) | 772.31 (731.78–812.85) | <.001 |

| TAG | 13.00 (11.96–14.04) | 13.19 (11.99–14.39) | .865 | 1040.72 (951.04–1130.39) | 978.40 (906.90–1049.91) | .406 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range). Bolded P values were significant at the .05 level.

Abbreviations: CE, cholesterol ester; CER, ceramide; DAG, diacylglycerol; DCER, dihydroceramide; FFA, free fatty acid; HCER, hexosylceramide; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LCER, lactosylceramide; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; SM, sphingomyelin; TAG, triacylglycerol; YPHIV, youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus.

a P values calculated using 2-sample t test.

Figure 1.

Mean concentrations of lipids at baseline. Dot plots showing the mean baseline lipid levels in youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus (YPHIV) and human immunodeficiency virus– negative children (HIV–). Horizontal lines denote the 95% confidence interval (CI). A, Ceramides (CER). B, Diacylglycerol (DAG). C, Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC). D, Phosphatidylcholine (PC).

At 96 weeks, overall decreases in lipid composition and concentrations were more pronounced in YPHIV. Specifically, several lipid classes decreased in YPHIV: The proportional representation of CER (P < .001), DAG (P < .001), HCER (P = .003), LPC (P < .001), and PC (P < .001) within the lipid composition, as well as lipid concentrations of FFA (P = .014) and LPC (P = .036), decreased over time in YPHIV. However, the relative levels of FFA and SM within total lipids, as well as HCER, LCER, and LPE concentrations, increased in YPHIV (Table 3). In subgroup analyses, except for the lipid composition of CE, there was no differences in comparing lipid class changes over 96 weeks between YPHIV who switched to INSTI versus YPHIV who did not switch (Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, other than a milder decrease in PC and a larger decrease in TAG lipid composition, there was no difference over 96 weeks between YPHIV who remained on a protease inhibitor (PI) during the study period compared to those who were not on PIs (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 3.

Average Change in Lipid Class Composition and Concentration From Baseline to 96 Weeks for Youth With Perinatally Acquired Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and HIV-Negative Children

| Lipid Class | Lipid Composition, mol % | Lipid Concentrations, µmol | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YPHIV | HIV-Negative Children | YPHIV | HIV-Negative Children | |||||

| Δ | P Valuea | Δ | P Valuea | Δ | P Valuea | Δ | P Valuea | |

| CE | −0.21 (−1.54, 1.11) | .815 | 0.21 (−1.64, 2.06) | .875 | −9.56 (−195.93, 176.81) | .928 | 277.93 (133.44–422.43) | .001 |

| CER | −0.01 (−0.01, 0.00) | .001 | −.01 (−0.01, 0.00) | .080 | 0.00 (−0.50, 0.49) | .990 | 1.03 (0.61–1.45) | <.001 |

| DAG | −0.12 (−0.15, −0.08) | <.001 | −0.11 (−0.15, −0.06) | <.001 | 0.88 (−2.65, 4.41) | .750 | 2.27 (−.33, 4.87) | .162 |

| DCER | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | .271 | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.00) | .406 | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.06) | .910 | 0.07 (0.02–0.13) | .035 |

| FFA | 1.36 (0.25–2.48) | .046 | −0.14 (−2.23, 1.94) | .910 | −116.89 (−209.25, −24.53) | .041 | −99.04 (−188.50, −9.57) | .074 |

| HCER | −0.01 (−0.01, 0.00) | .011 | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.00) | .019 | 0.51 (0.28–0.73) | <.001 | 0.51 (0.30–0.72) | <.001 |

| LCER | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | .278 | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | .798 | 0.29 (0.10–0.48) | .014 | 0.34 (0.15–0.52) | .003 |

| LPC | −0.56 (−0.79, −0.32) | <.001 | −0.16 (−0.49, 0.16) | .428 | −25.56 (−49.34, −1.78) | .080 | 15.08 (−3.20, 33.35) | .187 |

| LPE | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.00) | .428 | −0.03 (−0.09, 0.03) | .456 | 0.93 (0.23–1.62) | .033 | 0.99 (0.59–1.39) | <.001 |

| PC | −3.13 (−4.05, −2.21) | <.001 | −1.21 (−2.53, 0.10) | .140 | 28.67 (−115.34, 172.68) | .795 | 225.26 (135.92–314.60) | <.001 |

| PE | −0.06 (−0.18, 0.05) | .406 | −0.46 (−1.20, 0.27) | .338 | 10.44 (−0.35, 21.23) | .121 | 16.61 (7.95–25.26) | .001 |

| SM | 3.41 (2.92–3.90) | <.001 | 3.25 (2.45–4.04) | <.001 | −25.96 (−69.10, 17.18) | .358 | 40.96 (−29.33, 111.25) | .375 |

| TAG | −1.20 (−2.50, 0.11) | .140 | −0.38 (−2.24, 1.49) | .795 | 112.81 (−16.79, 242.40) | .162 | 90.25 (−7.85, 188.34) | .140 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range). Bolded P values were significant at the .05 level.

Abbreviations: CE, cholesterol ester; CER, ceramide; DAG, diacylglycerol; DCER, dihydroceramide; FFA, free fatty acid; HCER, hexosylceramide; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LCER, lactosylceramide; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; SM, sphingomyelin; TAG, triacylglycerol; YPHIV, youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus.

a P values calculated using paired t test.

Compared to HIV– youth, DAG concentration remained elevated in YPHIV at both baseline and week 96 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diacylglycerol concentration changes (mean with confidence interval [CI]) by study group over time (27.47 vs 34.81 at baseline; and 29.86 vs 35.65 µmol at week 96 for human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]–negative [HIV–] children vs youth with perinatally acquired HIV [YPHIV], respectively; P ≤ .007).

Associations With Inflammatory and Gut Markers in YPHIV

In YPHIV, at baseline, several lipid classes correlated with multiple biomarkers: (1) with monocyte activation: composition of HCER and TAG correlated with sCD14 (ρ = .33, ρ = .2, respectively), CER, DAG, DCER, LPC, and TAG correlated with the proportional representation of inflammatory monocytes (CD14+CD16+; ρ = .21–.36), and DAG, LPC, and TAG correlated with patrolling monocytes (CD14dimCD16pos, ρ = .20–.25); (2) with T-cell activation: LPC and TAG correlated with activated CD4+ T cells (CD4+CD3+HLA-DR+; ρ = .28 for both); and DAG and TAG correlated with CD8+ T cells (CD8+HLA-DR+; ρ = .22–.28).

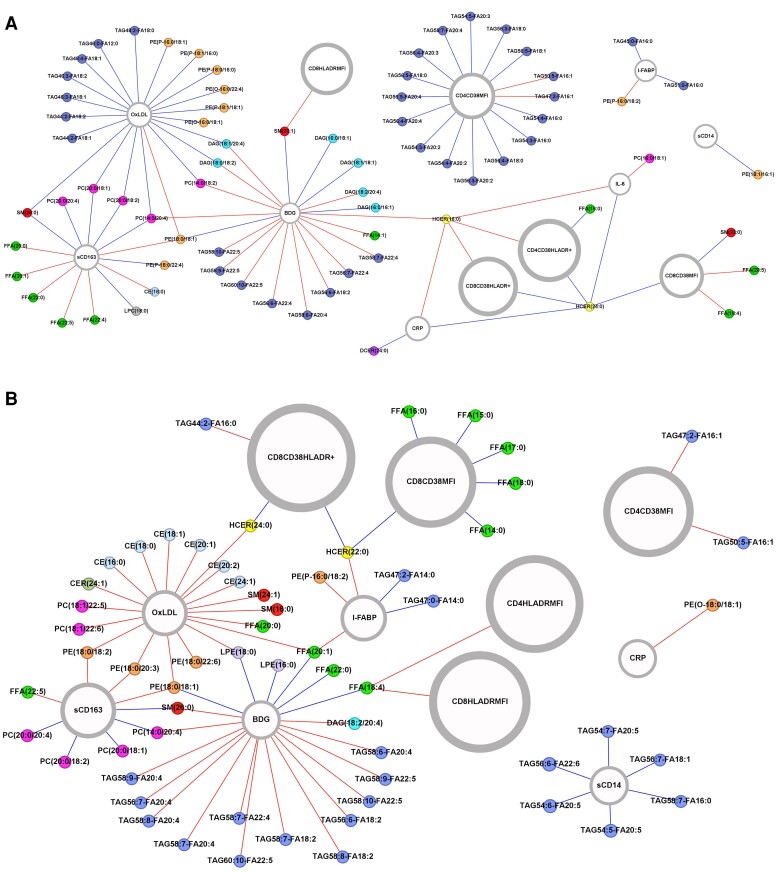

A network figure (Figure 3) highlights the associations in YPHIV between changes in lipid species compositions and concentrations and inflammatory biomarkers over 96 weeks with a correlation >|0.4|. Notable trends were only seen in YPHIV and included (1) the association between increases in PE 18:0 with increases in sCD163, OxLDL, hsCRP, and intestinal fatty acid binding protein (I-FABP); and (2) the predominant association with increases in long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) within TAGs and decreases in activated CD4 T cells, and with decreases in both microbial translocation marker sCD14 and gut integrity marker I-FABP. We have previously described changes over 96 weeks in biomarkers [17] and found that in YPHIV, hsCRP decreased by 40%, I-FABP and Beta D Glucan increased by 19% and 38%, respectively, and OxLDL and sCD14 remained stable.

Figure 3.

Relevance network graph depicting correlations >|0.4| between changes in the lipidome and changes in inflammatory biomarkers over 96 weeks. A, Composition of lipids. B, Concentration of lipids. Red edges show positive correlations and blue negative correlations. Inflammatory and immune activation biomarkers are in gray. Lipids are colored according to lipid class: cholesterol ester (CE), light blue; ceramide (CER), green; diacylglycerol (DAG), turquoise; diacylglycerol (DCER), purple; free fatty acid (FFA), bright green; hexosylceramide (HCER), yellow; lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), gray; lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE), lavender; phosphatidylcholine (PC), magenta; phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), orange; sphingomyelin (SM), red; triacylglycerol (TAG), blue. Abbreviations: BDG, Beta D Glucan; CRP, C-reactive protein; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; OxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; sCD14, soluble CD14.

Associations With Cardiometabolic Measures

We found that increases in medium chain (C18–20) saturated PC and PE correlated with increases in blood pressure and BMI over the study period (Supplementary Figure 2).

A network figure highlights the associations between changes in lipid species composition and concentrations and CVD markers over 96 weeks with a correlation >|0.3| (Figure 4). Notable trends were only seen in YPHIV. Specifically, increases in saturated CE and PC were associated with increases in IMT and increases in the compositional representation and concentrations of saturated acyl chains of PE (PE18:0) with increases in PWV over 96 weeks. Long chain polyunsaturated triacylglycerols were negatively associated with IMT and PWV. We have previously described changes over 96 weeks in CVD measures [16], and found that in YPHIV, IMT decreased and PWV increased (P ≤ .03).

Figure 4.

Relevance network graph depicting correlations between changes in the lipidome and changes in intima media thickness (IMT) and pulse wave velocity (PWV) in youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus over 96 weeks. A, Composition of lipids. B, Concentration of lipids. Red edges show positive correlations and blue negative correlations. Cardiovascular disease measures: mean IMT and PWV are in gray. Lipids are colored according to lipid class: cholesterol ester (CE), light blue; diacylglycerol (DCER), pink; free fatty acid (FFA), bright green; phosphatidylcholine (PC), magenta; phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), orange; sphingomyelin (SM), red; triacylglycerol (TAG), blue.

DISCUSSION

Basic lipid panels provide insufficient characterization and insight as to the fundamental metabolic perturbations in HIV infection and their relationship to both inflammation and CVD risk [19]. Few studies have investigated the molecular lipids that compose lipoproteins (lipidomic) in HIV [20] and their relationship to inflammation and CVD risk, but to our knowledge no studies have examined these associations in YPHIV. Overall, 5 lipid classes and their saturated fatty acid content were elevated in YPHIV (LCER, LPC, PC, CER, and DAG). Specifically, we found that in YPHIV only, increases in PE containing 16:0 (palmitic acid) and 18:0 (stearic acid) correlated with increases in systemic inflammation, immune activation, and arterial stiffness over 2 years, and that long chain PUFA correlated with decreases in inflammation and CVD marker progression.

In this study, we used a targeted lipid analysis technology that estimates concentrations using a mixture of internal standards, and we present lipid class concentration and composition (or percentage contribution to the sum of all measured lipids). Lipid fatty acid compositions are often used to describe the role of the lipidome on cardiometabolic outcomes, and recent findings suggest that serum concentrations of lipid fatty acids may be a more accurate reflections of the changes in lipids rather than percentage; we therefore decided to present both to be able to explain our findings in the context of other manuscripts and for ease of interpretation in metabolic and future therapeutic terms [21].

Compared to HIV– youth, perinatally acquired HIV was associated with a significantly altered lipidome that was abundant in saturated CER, DAG, LPC and PC lipid species, consistent with what we reported in our previous pilot data [14]. Our findings corroborate lipidomic analyses in HIV– youth who have known metabolic complications and increased CVD risk. LPC and PC levels are increased in children and youth who have obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [22], or type 1 diabetes [23]. In a large study of 990 HIV– adolescents (aged 12–18 years), LPCs were associated with multiple CVD risk factors including visceral abdominal fat, blood pressure, insulin resistance, and atherogenic dyslipidemia [24].

Similarly to Findings in Adults With HIV, Saturated DAGs Remain Elevated in YPHIV Throughout the Study Period and Despite Viral Suppression on ART

The lipidome composition can be impacted by age, sex [25], diet [26], and genetic background. Age and puberty may have contributed to the changes in the lipidome over the study period; however, YPHIV and HIV– were well matched demographically such that differences between the groups cannot be attributed to demographic factors.

Lipids and their metabolites can affect the differentiation of immune cells, particularly monocytes and T cells, as well as their activation and function, with important consequences for the balance between anti- and proinflammatory signals in diseases. Saturated fatty acids induce inflammasome activation and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling [27], in contrast, PUFAs inhibit inflammation and modulate the fatty acid oxidation pathway [28]. Underlying mechanisms include activation of TLR4, lipid raft formation, transcription factor activation, and gene expression. This is consistent with our findings: In our study we found notable trends with markers of inflammation and lipidome signatures that were only seen in YPHIV. Specifically, increases in stearic acid correlated with increases in markers of systemic inflammation, monocyte activation, and gut integrity over 2 years. In our pilot data, we have previously shown similarly that phospholipids with 16 and 18 carbons also correlated with systemic inflammation and monocyte activation markers [14]. In vitro exposure of PBMCs to these lipids results in monocyte activation and inflammatory cytokine production [29]. On the other hand, long chain PUFAs containing TAGs were correlated with decreases in T-cell activation, OxLDL, sCD14 (a marker of microbial translocation), and I-FABP. Stearic acid is known to activate the inflammasome and trigger interleukin 1β release in myeloid cells [30], as opposed to PUFAs, which decrease fatty acid oxidation pathways, and inflammatory mediators in macrophages and lymphocytes [31]. We have previously reported in this cohort, over 96 weeks, that immune activation, microbial translocation, and altered gut integrity persist over time in YPHIV despite viral suppression [17]. Findings from this lipidome analysis may suggest that perinatally acquired HIV–associated alterations in lipid profiles may either be a driver or the consequence of the inflammation associated with a disrupted gut barrier and microbial translocation.

Saturated fatty acids, especially those containing 12 to 16 carbon atoms, have been associated with higher risk of CVD and atherosclerosis [32]. PE is the second most abundant lipid and is abundant in mitochondria [33]. It is known to be involved in inflammatory processes after myocardial infarction by binding to macroglobulin, which increases the expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and decreases smooth muscle and collagen [34]. PE has been associated with peripheral occlusive arterial disease [35] and the inflammatory phase of myocardial infarctions [36]. Palmitic acid, specifically, is one of the most important acids of triglyceride in adipose tissue and has been linked to CVD [37]. Stearic acid, on the other hand, does not have a significant influence on lipid metabolism but can induce apoptosis and necrosis of endothelial cells and is associated with higher risk of ischemic heart disease [38]. In our study, increases in PE (16:0 and 18:0) correlated with increases in PWV or arterial stiffness only in YPHIV. This is concerning as PWV has been shown to predict cardiovascular mortality in older cohorts without HIV [39]. In addition, we have highlighted in a previous publication that PWV increased slightly in YPHIV compared to HIV– youth over 96 weeks [16]. This may suggest that palmitic and stearic acids may serve as promising early biomarkers in this population for CVD risk; however, future larger studies are required to confirm these findings. Both palmitic and stearic acid are found in vegetable and animal fats, with palm oil, coconut oil, and ghee being the most common forms, and also the major form of dietary fat used by the participants in this study. Lipid-lowering drugs, specifically statins, remain the primary therapy for CVD risk reduction, and the Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) study, the first large-scale study to study statin for CVD risk reduction in people with HIV [40], has generated the evidence needed to move forward with statin for CVD prevention in people with HIV with low-to-intermediate 10-year CVD risk [41]. However, data are insufficient to recommend for or against statin therapy in people under the age of 40 years, as stated by recent guidelines, which highlight the urgent need for prevention trials in younger adults who are at high lifetime risk of CVD.

Among the seronegative youth, we found that several lipid species including CE, PE, PC, and SM increased significantly over the study period and that SM remained elevated compared to YPHIV at both time points. We have also previously highlighted that markers of oxidative stress, monocyte activation, and activated T cells also increased over 96 weeks in the seronegative group [17]. These findings highlight that exposure to non-HIV adversities in sub-Saharan Africa, including socioeconomic stress, rising air pollution, and coinfections, likely all contribute to inflammation in this setting [42].

Our study was limited by the lack of detailed dietary data. The data generated here are exploratory; the study was not powered for lipidomics analyses. The demographics of YPHIV and HIV– children were well matched, however, and our study contains a detailed investigation into levels of inflammatory biomarkers. Our findings may also be applicable to a large proportion of YPHIVs, as the majority of adolescents with HIV reside in Eastern and Southern Africa [43]. In addition, although both IMT and PWV have been well correlated with the presence of coronary and carotic atherosclerosis [44], these measures have several limitations. PWV needs precise measurement of blood pressure, as well as the distance between target points of arteries [44], both of which can be difficult in a pediatric population. A main limitation of IMT is the lack of standardized accepted scan protocol [45]. We attempted to minimize variability by adapting a standardized protocol for both PWV and IMT, as previously described [16], as well as having the same study team members who performed the measurements during the study period.

In conclusion, we describe alterations in the lipidome in YPHIV in Uganda, despite viral suppression on long-term ART, and significant associations with saturated fatty acid increases that may exacerbate inflammation and CVD risk over time, whereas PUFAs appear protective. These novel lipid biomarkers, and specifically PE 16:0 and 18:0, may offer better prognostic value than conventional lipid measurements. Further longitudinal studies are warranted.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Sahera Dirajlal-Fargo, Pediatric Infectious Disease, Ann and Robert Lurie Children‘s Hospital, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Melica Nikahd, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Ohio State University, Columbus.

Kate Ailstock, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Ohio State University, Columbus.

Manjunath Manubolu, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Ohio State University, Columbus.

Victor Musiime, Department of Pediatrics, Makerere University; Joint Clinical Research Center, Kampala, Uganda.

Cissy Kityo, Joint Clinical Research Center, Kampala, Uganda.

Grace A McComsey, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Nicholas T Funderburg, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Ohio State University, Columbus.

Notes

Author contributions. S. D.-F. and N. T. F. designed the study. S. D.-F., N. T. F., and G. A. M. obtained funding. C. K. and V. M. oversaw study evaluations and monitoring. M. N. provided statistical support. K. A. and N. T. F. performed the biomarker assays and flow cytometry. M. M. performed the lipidomic analysis. S. D.-F. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to data analysis and reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content.

Disclaimer. The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center Clinical Research Center or the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health (grant numbers U01 AI168630 to N. T. F. and S. D.-F., and R21HD106579 to S. D.-F.). This publication was made possible through funding support of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center Clinical Research Center (UHCRC) and the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland (UL1TR002548) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of UHCRC or the NIH.

References

- 1. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) . UNAIDS global AIDS update 2023. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2024.

- 2. Paula AA, Schechter M, Tuboi SH, et al. Continuous increase of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and non-HIV related cancers as causes of death in HIV-infected individuals in Brazil: an analysis of nationwide data. PLoS One 2014; 9:e94636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elbirt D, Mahlab-Guri K, Bezalel-Rosenberg S, Gill H, Attali M, Asher I. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Isr Med Assoc J 2015; 17:54–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cucchi D, Camacho-Muñoz D, Certo M, Pucino V, Nicolaou A, Mauro C. Fatty acids—from energy substrates to key regulators of cell survival, proliferation and effector function. Cell Stress 2019; 4:9–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hinterwirth H, Stegemann C, Mayr M. Lipidomics: quest for molecular lipid biomarkers in cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2014; 7:941–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alshehry ZH, Mundra PA, Barlow CK, et al. Plasma lipidomic profiles improve on traditional risk factors for the prediction of cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2016; 134:1637–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laaksonen R, Ekroos K, Sysi-Aho M, et al. Plasma ceramides predict cardiovascular death in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes beyond LDL-cholesterol. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:1967–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stegemann C, Pechlaner R, Willeit P, et al. Lipidomics profiling and risk of cardiovascular disease in the prospective population-based Bruneck study. Circulation 2014; 129:1821–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eichelmann F, Prada M, Sellem L, et al. Lipidome changes due to improved dietary fat quality inform cardiometabolic risk reduction and precision nutrition [manuscript published online ahead of print 11 July 2024]. Nat Med 2024. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03124-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Funderburg NT, Mehta NN. Lipid abnormalities and inflammation in HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2016; 13:218–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lake JE, Currier JS. Metabolic disease in HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:964–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bowman E, Funderburg NT. Lipidome abnormalities and cardiovascular disease risk in HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2019; 16:214–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chai JC, Deik AA, Hua S, et al. Association of lipidomic profiles with progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis in HIV infection. JAMA Cardiol 2019; 4:1239–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dirajlal-Fargo S, Sattar A, Yu J, et al. Lipidome association with vascular disease and inflammation in HIV+ Ugandan children. AIDS 2021; 35:1615–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dirajlal-Fargo S, Albar Z, Bowman E, et al. Increased monocyte and T-cell activation in treated HIV+ Ugandan children: associations with gut alteration and HIV factors. AIDS 2020; 34:1009–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dirajlal-Fargo S, Zhao C, Labbato D, et al. Longitudinal changes in subclinical vascular disease in Ugandan youth with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76:e599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dirajlal-Fargo S, Strah M, Ailstock K, et al. Persistent immune activation and altered gut integrity over time in a longitudinal study of Ugandan youth with perinatally acquired HIV. Front Immunol 2023; 14:1165964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uganda Ministry of Health . Consolidated guidelines for the prevention and treatment of HIV and AIDS in Uganda. 2020. https://hivpreventioncoalition.unaids.org/en/resources/consolidated-guidelines-prevention-and-treatment-hiv-and-aids-uganda-november-2022. Accessed 30 September 2024.

- 19. Munger AM, Chow DC, Playford MP, et al. Characterization of lipid composition and high-density lipoprotein function in HIV-infected individuals on stable antiretroviral regimens. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015; 31:221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhao W, Wang X, Deik AA, et al. Elevated plasma ceramides are associated with antiretroviral therapy use and progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis in HIV infection. Circulation 2019; 139:2003–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schwertner HA, Mosser EL. Comparison of lipid fatty acids on a concentration basis vs weight percentage basis in patients with and without coronary artery disease or diabetes. Clin Chem 1993; 39:659–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mann JP, Jenkins B, Furse S, et al. Comparison of the lipidomic signature of fatty liver in children and adults: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2022; 74:734–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu Y, Dong G, Huang K, et al. Metabolomics and lipidomics studies in pediatric type 1 diabetes: biomarker discovery for the early diagnosis and prognosis. Pediatr Diabetes 2023; 2023:6003102. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Syme C, Czajkowski S, Shin J, et al. Glycerophosphocholine metabolites and cardiovascular disease risk factors in adolescents: a cohort study. Circulation 2016; 134:1629–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Audano M, Maldini M, De Fabiani E, Mitro N, Caruso D. Gender-related metabolomics and lipidomics: from experimental animal models to clinical evidence. J Proteomics 2018; 178:82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nam KN, Mounier A, Wolfe CM, et al. Effect of high fat diet on phenotype, brain transcriptome and lipidome in Alzheimer's model mice. Sci Rep 2017; 7:4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suganami T, Tanimoto-Koyama K, Nishida J, et al. Role of the Toll-like receptor 4/NF-kappaB pathway in saturated fatty acid–induced inflammatory changes in the interaction between adipocytes and macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007; 27:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:408–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bowman ER, Kulkarni M, Gabriel J, et al. Altered lipidome composition is related to markers of monocyte and immune activation in antiretroviral therapy treated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and in uninfected persons. Front Immunol 2019; 10:785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Robblee MM, Kim CC, Porter Abate J, et al. Saturated fatty acids engage an IRE1α-dependent pathway to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in myeloid cells. Cell Rep 2016; 14:2611–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bensinger SJ, Tontonoz P. Integration of metabolism and inflammation by lipid-activated nuclear receptors. Nature 2008; 454:470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mensink RP, Zock PL, Kester AD, Katan MB. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 77:1146–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patel D, Witt SN. Ethanolamine and phosphatidylethanolamine: partners in health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017; 2017:4829180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hakuno D, Kimura M, Ito S, et al. Hepatokine α1-microglobulin signaling exacerbates inflammation and disturbs fibrotic repair in mouse myocardial infarction. Sci Rep 2018; 8:16749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kunz F, Stummvoll W. Plasma phosphatidylethanolamine—a better indicator in the predictability of atherosclerotic complications? Atherosclerosis 1971; 13:413–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pistritu D-V, Vasiliniuc A-C, Vasiliu A, et al. Phospholipids, the masters in the shadows during healing after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24:8360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harvey KA, Walker CL, Pavlina TM, Xu Z, Zaloga GP, Siddiqui RA. Long-chain saturated fatty acids induce pro-inflammatory responses and impact endothelial cell growth. Clin Nutr 2010; 29:492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shramko VS, Polonskaya YV, Kashtanova EV, Stakhneva EM, Ragino YI. The short overview on the relevance of fatty acids for human cardiovascular disorders. Biomolecules 2020; 10:1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meaume S, Benetos A, Henry OF, Rudnichi A, Safar ME. Aortic pulse wave velocity predicts cardiovascular mortality in subjects >70 years of age. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21:2046–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grinspoon SK, Fitch KV, Zanni MV, et al. Pitavastatin to prevent cardiovascular disease in HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2023; 389:687–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents . Recommendations for the use of statin therapy as primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in people with HIV. 2024. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-arv/statin-therapy-people-hiv. Accessed 30 September 2024.

- 42. Calderón-Garcidueñas L, Villarreal-Calderon R, Valencia-Salazar G, et al. Systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and activation in clinically healthy children exposed to air pollutants. Inhal Toxicol 2008; 20:499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maulide Cane R, Melesse DY, Kayeyi N, et al. HIV trends and disparities by gender and urban-rural residence among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health 2021; 18(Suppl 1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim HL, Kim SH. Pulse wave velocity in atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2019; 6:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ravani A, Werba JP, Frigerio B, et al. Assessment and relevance of carotid intima-media thickness (C-IMT) in primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention. Curr Pharm Des 2015; 21:1164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.