Abstract

The differentiation and functionality of virus-specific T cells during acute viral infections are crucial for establishing long-term protective immunity. While numerous molecular regulators impacting T cell responses have been uncovered, the role of cellular prion proteins (PrPc) remains underexplored. Here, we investigated the impact of PrPc deficiency on the differentiation and function of virus-specific T cells using the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) Armstrong acute infection model. Our findings reveal that Prnp–/– mice exhibit a robust expansion of virus-specific CD8+ T cells, with similar activation profiles as wild-type mice during the early stages of infection. However, Prnp–/– mice had higher frequencies and numbers of virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells, along with altered differentiation profiles characterized by increased central and effector memory subsets. Despite similar proliferation rates early during infection, Prnp–/– memory CD8+ T cells had decreased proliferation compared with their wild-type counterparts. Additionally, Prnp–/– mice had higher numbers of cytokine-producing memory CD8+ T cells, indicating a more robust functional response. Furthermore, Prnp–/– mice had increased virus-specific CD4+ T cell responses, suggesting a broader impact of PrPc deficiency on T cell immunity. These results unveil a previously unrecognized role for PrPc in regulating the differentiation, proliferation, and functionality of virus-specific T cells, providing valuable insights into immune system regulation by prion proteins during viral infections.

Keywords: LCMV, memory T cells, prions, T cells, viral infection

Introduction

During acute viral infection, naïve CD8+ T cells clonally expand and differentiate into effector T cells, which mediate direct killing of virally infected cells.1 Upon viral clearance, the majority of responding CD8+ T cells undergo apoptosis, while the few survivors differentiate into memory T cells.2,3 Memory T cells undergo transcriptional programming and are equipped with robust recall capacity for earlier acquisition of effector functions compared with naïve T cells.4–6 Memory T cells are poised for pathogen recognition and are key in providing long-term protective immunity to the host.7–9 During acute infection, effector CD8+ T cells acquire molecular signatures that dictate their memory differentiation trajectories.9–11 Long-term survival and recall capacity heterogeneity within memory T cells is noted by the various subsets that have been identified. Central memory T (Tcm) cells are the longest-lived, whereas effector memory T (Tem)6 and terminal effector memory T (Ttem) cells have more potent cytotoxic activity but have a terminal fate.12,13 While multiple molecular players in the differentiation process of memory CD8+ T cells have been identified, efforts continue to identify the cell-extrinsic and cell-intrinsic mechanisms that regulate the development of these cells.

Cellular prion proteins (PrPc) are glycoproteins primarily located at the outer plasma membrane.14 While expressed on neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, they are also expressed on hematopoietic stem cells.15–17 Misfolded, pathologic prions (PrPSc) have been well studied for their role in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, which result in fatal neurodegenerative diseases including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans.18–20 As the prion hypothesis suggests, this is a transmissible infectious disease in which prion proteins can sporadically undergo conformational changes, leading to misfolding and aggregation.21,22 These new isoforms (PrPSc) are characterized by increased beta-sheets and are more resistant to proteases, causing synaptic loss and neurotoxicity.23

While prion proteins have been extensively investigated in neuropathology, they have also been identified for playing a role in regulating the immune response. Prion protein–deficient mice (Prnp–/–) mice have normal development and longevity24–26 and similar T cell and B cell cellularity to wild-type (WT) mice.27,28 However, under inflammatory conditions, PrPc can be upregulated on activated T cells.29–31 In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis studies, PrPc negatively regulated T cell activation and function, as shown by the increased T cell proliferation, infiltration, and cytokine production in spinal cord, cerebellum, and forebrain of Prnp–/– mice, resulting in more aggressive disease.29,32,33 Prnp–/– mice also showed decreased systemic bacteremia in a streptococcal sepsis infection.29 Depleting PrPc from HIV-infected T cells led to increased viral replication, and this was also evident in microglia.34 PrPc was found to be protective against influenza viral infection, in which Prnp–/– infected mice had higher viral titers, weight loss, and mortality in compared with WT mice.35,36 These studies highlight an important modulatory role for PrPc in the immune system. However, how PrPc regulates virus-specific T cell memory has been underexplored.

In this study, we investigated the role of cellular prion proteins in the differentiation of virus-specific T cells using the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) Armstrong acute infection model. Prnp–/– Armstrong infected mice had a robust expansion of virus-specific CD8+ T cells by the peak of clonal expansion. Furthermore, Prnp–/– and WT virus-specific CD8+ T cells had similar activation profiles during early stages postinfection, as shown by similar proliferation, accumulation, cytokine production, and PD-1 expression levels. However, by late stages of infection when T cells differentiate into memory cells, Prnp–/– mice had higher frequencies and numbers of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared with WT mice. Furthermore, while Prnp–/– memory CD8+ T cells had decreased proliferation, we observed increased numbers of Tcm, Tem, and Ttem cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT mice. Consistent with the improved memory response in Prnp–/– mice, we also observed higher frequencies and numbers of cytokine-producing T cells. We also noted an increased virus-specific CD4+ T cell response in Prnp–/– mice at the effector and memory phase of the response, as shown by the higher numbers and frequencies of cytokine-producing cells. Our findings show that PrPc deficiency negatively regulates the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of virus-specific T cells, which impacts their differentiation toward memory and adds to our understanding of immune system regulation by prion proteins.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and then bred in specific pathogen–free facilities and maintained in biosafety level 2 facilities after infection in the vivarium at the University of California, Irvine. C57BL/6J Prnp–/– mice were generously provided by Dr Christina Sigurdson (University of California San Diego) with permission from Dr Adriano Aguzzi (Universität Zürich). Both female and male mice were used and were greater than 6 weeks of age. All experiments were approved by the animal care and use committees at the University of California, Irvine (AUP-21-124).

Virus titers and infections

The LCMV Armstrong24 strain was propagated in baby hamster kidney cells and titrated on Vero African green monkey kidney cells. Frozen stocks were diluted in Vero cell media and mice were infected by intraperitoneal injection of 2 × 105 plaque-forming units of the LCMV arm.

Flow cytometry

Cells from infected spleens were dissociated in Hanks’ Buffered Salt Solution. For cell surface staining, 2 × 106 cells were incubated with antibodies in staining buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, 2% fetal bovine serum, and 0.01% NaN3) for 20 min at 4 °C. H-2Db-GP33–41, H-2Db-GP276–286, H-2Db-NP396–404, and IAb-66–77 tetramers (National Institutes of Health core facility) were stained for 1 h 15 min at room temperature. For functional assays, 2 × 106 cells from infected spleens were cultured for 4 h at 37 °C with 2 µg/mL of GP33–41, GP276–286, NP396–404, and GP61–80 peptides (AnaSpec) in the presence of brefeldin A (1 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were then stained with antibodies for expression of surface proteins, fixed, permeabilized, and stained with antibodies for intracellular cytokine detection. The culture media used was RPMI-1640 containing 10 mM HEPES, 1% nonessential amino acids and L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, and penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics. The following anti-mouse antibodies were used in this study: BioLegend CD4 (RM4-5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD127(A7R34), KLRG-1 (2F1/KLRG1), CD62L (MEL-14), interferon γ (IFN-γ) (XMG1.2), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (MP6-XT22), PD-1 (29F.1A12), and CD107 (H4A3).

Data analysis

Flow cytometry data was analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar) version 10.10. Graphs were made using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software) version 10.4.0, and GraphPad Prism was used for statistical analysis to compare outcomes using a 2-tailed unpaired t test. Significance was set to P < 0.05 and represented as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.005, and ****P < 0.0001. Error bars show the SEM.

Results

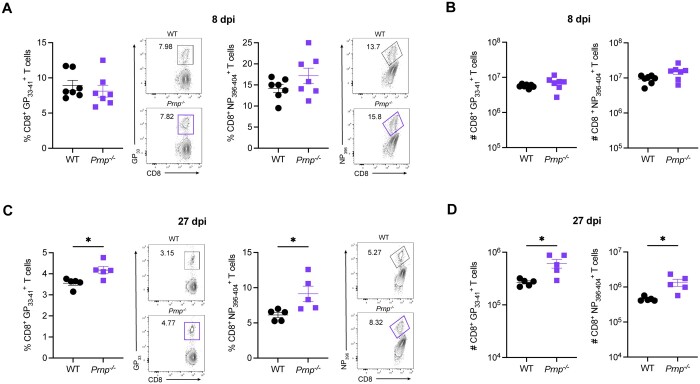

Prnp–/– mice have increased virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells after LCMV infection

To evaluate the role of cellular prion proteins in CD8+ T cells during an acute viral infection, we infected WT or Prnp–/– mice with LCMV Armstrong and compared the frequencies and numbers of tetramer+ CD8+ T cells between WT and Prnp–/– mice at 8 and 27 days postinfection (dpi). At 8 dpi, we observed similar frequencies and numbers of and CD8+ T cells in the spleens of WT and Prnp–/– mice (Fig. 1A, B). At 27 dpi, we observed significantly increased frequencies of and CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 1C). Importantly, we also found significantly increased numbers of tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT mice at this late time point postinfection (Fig. 1D). These findings showed that while prion protein deficiency on CD8+ T cells did not seem to impact the early effector T cell response, prion protein deficiency did impact the development of memory T cells after viral clearance.

Figure 1.

Prnp deletion results in increased virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells. WT and Prnp–/– mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong and spleens were harvested at indicated time points. (A) Frequencies of tetramer+ CD8+ T cells at 8 dpi and representative FACS plots. (B) Numbers of tetramer+ CD8+ T cells at 8 dpi. (C) Frequencies of tetramer+ CD8+ T cells at 27 dpi and representative FACS plots. (D) Numbers of tetramer+ CD8+ T cells at 27 dpi. *P < 0.05.

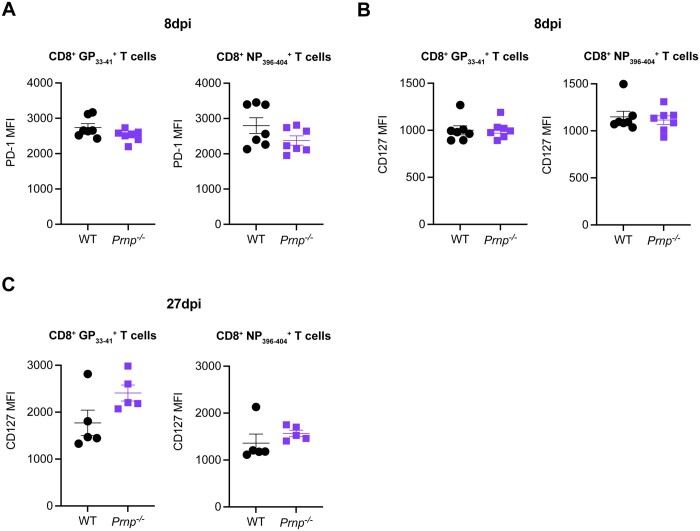

Prnp–/– and WT virus-specific CD8+ T cells have similar PD-1 and interleukin-7Rα expression levels

We next investigated whether cellular prion protein deficiency changed T cell activation by evaluating PD-1 expression or survival by evaluating interleukin (IL)-7Rα (CD127) expression at 8 and 27 dpi. At 8 dpi, we observed no differences in PD-1 expression (Fig. 2A) or CD127 expression (Fig. 2B) on GP33–41, and NP396–404 CD8+ T cells between WT and Prnp–/– mice. At 27 dpi, we noted that overall CD127 expression levels were higher than at 8 dpi, consistent with the memory phenotype of virus-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2C). Even though we noted no significant differences between WT and Prnp–/– virus-specific CD8+ T cells, we observed a trend toward increased expression levels on tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice (Fig. 2C). These findings again suggested that PrPc deficiency on antiviral CD8+ T cells did not seem to impact early effector responses but may impact differentiation into memory cells.

Figure 2.

Prnp deletion does not change PD-1 and CD127 expression levels in virus-specific CD8+ T cells. WT and Prnp–/– mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong and spleens were harvested at indicated time points. (A) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PD-1 in tetramer+ CD8+ T cells at 8 dpi. (B) MFI of CD127 in tetramer+ CD8+ T cells at 8 dpi. (C) MFI of CD127 in tetramer+ CD8+ T cells at 27 dpi.

Prnp–/– memory CD8+ T cells have decreased proliferation

We next assessed the proliferation of effector and memory CD8+ T cells at 8 and 27 dpi. At 8 dpi, we observed greater than 95% Ki67+ GP33–41 and NP396–404 CD8+ virus-specific T cells in both WT and Prnp–/– mice, which indicated a high proliferation rate of effector T cells (Fig. 3A). At 27 dpi, we observed significantly lower frequencies of Ki67+ GP33–41 and NP396–404 CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 3B). These findings showed similar proliferation of effector CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice early during the response to viral infection, but Prnp–/– virus-specific memory T cells had reduced proliferation at late stages of viral infection.

Figure 3.

Prnp deletion results in decreased proliferation of virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells. WT and Prnp–/– mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong and spleens were harvested at indicated time points. (A) Frequencies of Ki67+ in tetramer+ CD8+ T cells at 8 dpi. (B) Frequencies and FACS plot representative of Ki67+ in tetramer+ CD8+ T cells at 27 dpi. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001.

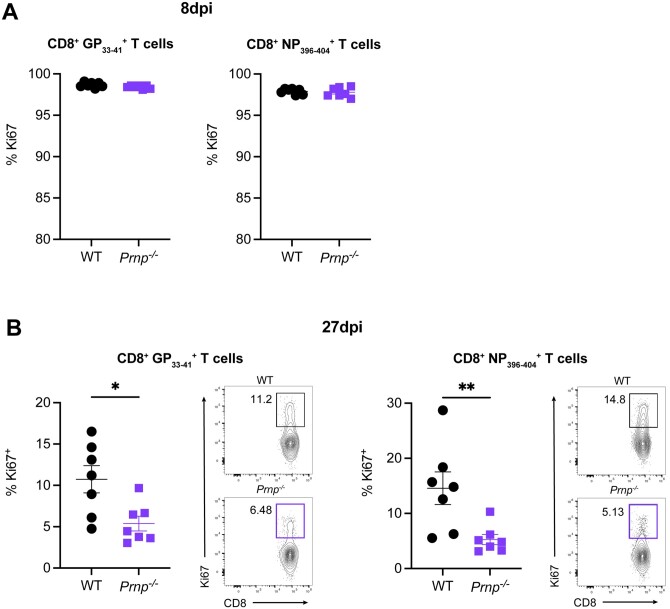

Prnp deficiency impacts memory CD8+ T cell differentiation

We next characterized the differentiation phenotypes of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. We evaluated the frequencies of Tcm, Tem, and Ttem CD8+ T cells based on CD62L vs CD127 expression at 27 dpi. We observed no differences in Tcm cell frequencies of CD8+ T cells between WT and Prnp–/– mice (Fig. 4A). However, Prnp–/– mice had significantly increased frequencies of Tem cells and significantly decreased frequencies of Ttem CD8+ T cells compared with WT mice (Fig. 4A). These trends were mirrored in CD8+ T cells, with no differences in Tcm cell frequencies, significantly increased Tem cell frequencies, and significantly decreased Ttem frequencies in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT by 27 dpi (Fig. 4B). We next enumerated the total number of memory CD8+ T cell subsets at 27 dpi in the spleen and observed higher numbers of Tcm, Tem, and Ttem CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4C). Higher absolute numbers of these memory T cell subsets were also present within the CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– infected mice (Fig. 4D). We also observed a higher ratio of Tem to Ttem cells in Prnp–/– compared with WT mice (Fig. 4E). These findings showed that Prnp expression regulates the differentiation and accumulation of subsets of memory CD8+ T cells following LCMV Armstrong infection.

Figure 4.

Prnp deletion alters virus-specific memory CD8+ T cell subset differentiation. WT and Prnp–/– mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong and spleens were harvested at 27 dpi. Frequencies and representative FACS plots of Tcm cells (CD127+, CD62L+), (Tem cells (CD127+, CD62L–), and Ttem cells (CD127–, CD62L–) in (A) GP33–41 tetramer+ and (B) GP394–404 tetramer+ CD8+ T cells. Numbers of Tcm cells (CD127+, CD62L+), Tem cells (CD127+, CD62L–), and Ttem cells (CD127–, CD62L–) in (C) GP33–41 tetramer+ and (D) GP394–404 tetramer+ CD8+ T cells. (E) The ratio of Tem cells to Ttem cells is shown for each tetramer. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.005, and ****P < 0.0001.

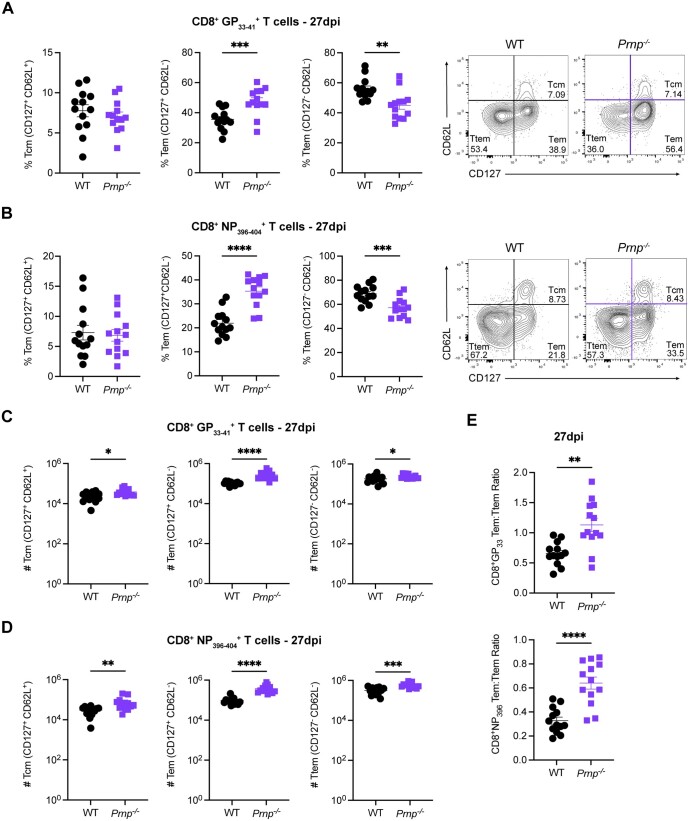

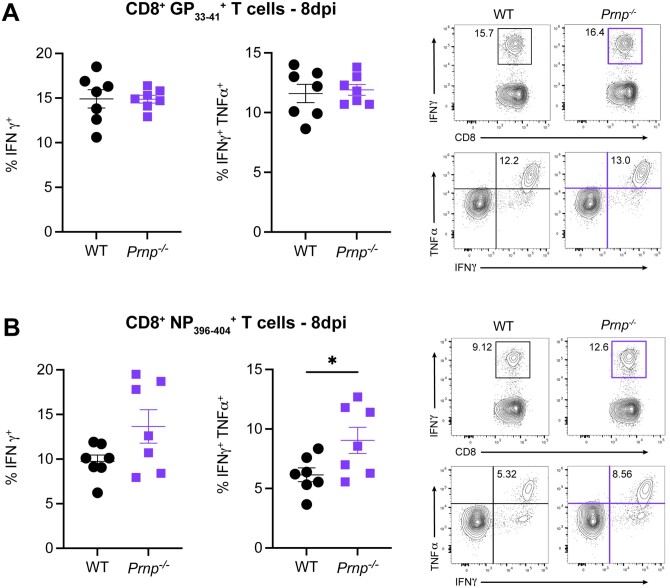

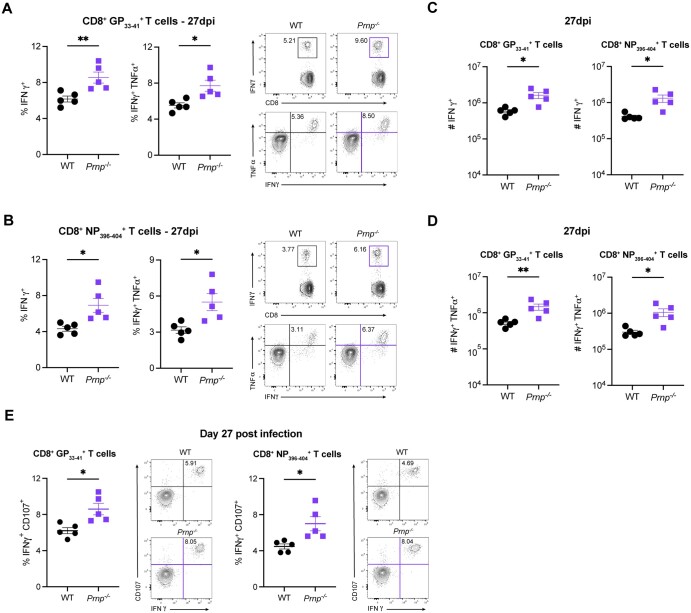

Prnp deficiency increases the numbers of cytokine-producing memory CD8+ T cells

We next assessed the functional changes in virus-specific CD8+ T cells by evaluating cytokine production by ex vivo peptide stimulation with either GP33–41 or NP396–404 at 8 and 27 dpi. At 8 dpi, we observed similar frequencies of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ CD8+ T cells in WT and Prnp–/– mice (Fig. 5A, B). At 27 dpi, we observed significantly higher frequencies of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+ TNFα+ CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT (Fig. 6A, B). Furthermore, we found significantly higher numbers of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 6C, D). We also observed higher frequencies of IFNγ+CD107+ GP33–41 and NP396–404 specific CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 6E). Collectively, these findings show that while functional memory CD8+ T cells are present in WT mice after Armstrong infection, Prnp deficiency increases the number of cytokine-producing memory T cells.

Figure 5.

Prnp deletion does not change the effector function of virus-specific effector CD8+ T cells early postinfection. Spleens were isolated from WT and Prnp–/– LCMV Armstrong–infected mice at 8 dpi and stimulated ex vivo with indicated LCMV peptides. Frequencies and representative FACS plots of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ in (A) GP33–41 peptide–stimulated and (B) NP396–404 peptide–stimulated CD8+ T cells. *P < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Prnp deletion increases the numbers of cytokine-producing virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells. Spleens were isolated from WT and Prnp–/– LCMV Armstrong–infected mice at 27 dpi and stimulated ex vivo with indicated LCMV peptides. Frequencies and representative FACS plots of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ in (A) GP33–41 peptide–stimulated and (B) NP396–404 peptide–stimulated CD8+ T cells. Numbers of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ in (C) GP33–41 peptide–stimulated and (D) NP396–404 peptide–stimulated CD8+ T cells. (E) The frequencies of IFNγ+CD107+ CD8+ T cells stimulated with GP33–41 and NP396–404 peptides and representative FACS plots. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001.

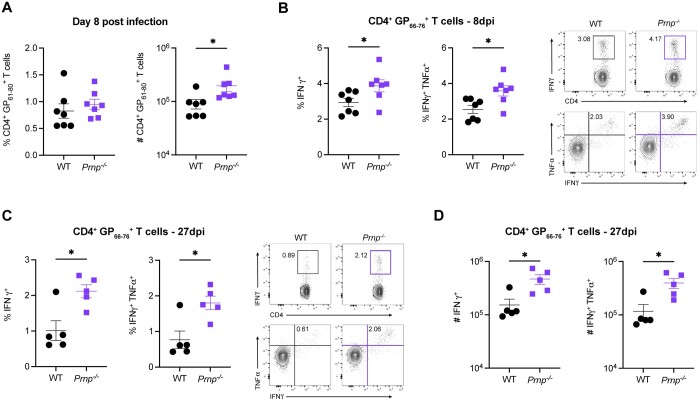

Prnp–/– mice have increased numbers of virus-specific CD4+ T cells after LCMV infection

To evaluate the role of cellular prion proteins in CD4+ T cells, we infected WT or Prnp–/– mice with LCMV Armstrong and compared the frequencies and numbers of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells between WT and Prnp–/– mice at 8 and 27 dpi. At 8 dpi, we observed similar frequencies and increased numbers of CD4+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT (Fig. 7A). Similarly, Prnp–/– mice had significantly higher frequencies and numbers of IFN-γ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ CD4+ T cells after peptide stimulation (Fig. 7B). These differences in Prnp–/– infected mice were maintained with higher frequencies and numbers of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ CD4+ T cells at 27 dpi (Fig. 7C, D). Our findings showed that virus-specific CD4+ T cell functional responses are increased in Prnp–/– mice early during infection and these differences continue into the stages of memory T cell differentiation.

Figure 7.

Prnp deletion results in increased numbers of virus-specific CD4+ memory T cells. Spleens were isolated from WT and Prnp–/– LCMV Armstrong–infected mice at and 8 and 27 dpi, and the immune response was characterized. (A) Frequencies and numbers of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells at 8 dpi. (B) Frequencies and representative FACS plots of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ in GP66–76 peptide–stimulated ex vivo CD4+ T cells at 8 dpi. (C) Frequencies and FACS plot representatives of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ in GP66–76 peptide–stimulated ex vivo CD4+ T cells at 27 dpi. (D) Numbers of IFNγ+ and IFNγ+TNFα+ in GP66–76 peptide–stimulated ex vivo CD4+ T cells at 27 dpi. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

While prion proteins have been widely studied in the brain, less is known regarding their function during immune responses. Previous work has shown that PrPc is expressed and upregulated on activated T cells,29–31 and other studies have suggested that PrPc deficiency directly regulates the T cell inflammatory response.29,32–34 In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of cellular prion proteins in virus-specific T cell differentiation during an acute viral infection. We found that Prnp–/– and WT mice had similar frequencies and numbers of virus-specific CD8+ T cells at the peak of T cell expansion. However, at late stages postinfection, we observed higher frequencies and numbers of virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice. We observed similar proliferation of Prnp–/– and WT CD8+ T cells at the peak of T cell expansion, but memory Prnp–/– CD8+ T cells had decreased proliferation compared with WT cells. Consistent with the increased memory CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice, we also observed higher numbers of Tcm, Tem, and Ttem cells compared with WT mice. Cytokine-producing Prnp–/– memory CD8+ T cells were also increased compared with WT postinfection. We also observed higher numbers of virus-specific CD4+ T cells after LCMV infection in Prnp–/– mice. These findings uncover a role for PrPc expression in the development and differentiation of memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells during acute viral infection.

After the virus is cleared, most effector T cells undergo apoptosis, while a few acquire transcriptional signatures that ensure their survival and differentiation.3,5 Tcm cells are long-lived memory cells that maintain the memory T cell pool, and mediate potent recall responses.4,13,37 Tem cells are shorter-lived and terminally fated compared with Tcm cells but exhibit potent effector functions.4,13,37,38 Ttem cells are abundant at early stages of infection, and while they have potent cytotoxic functions, they have the shortest lifespan, with limited multipotency and recall capacity.12 We observed that prion protein deficiency primarily resulted in changes in the frequencies of effector memory subsets at late stages of infection, with no differences in the frequencies of Tcm cells in Prnp–/– mice, increased Tem cell frequencies, and decreased Ttem cell frequencies. Interestingly, when enumerated, all 3 subsets of memory cells were present at higher numbers in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT mice. These findings showed that cellular prion protein expression in mice limited the responding T cell pool. More specifically, PrPc negatively regulated the differentiation and accumulation of memory T cells.

Negative regulation by prion proteins in T cells was previously reported in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, in which PrPc deficiency led to higher T cell cytokine production including IFNγ, TNFα, IL-2, and IL-17α along with increased pathology.29,32,33 Consistent with these findings, we also observed higher frequencies and numbers of cytokine-producing LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice but only at the memory phase. Previously, PrPc stimulation with antibodies resulted in an increased abundance of M2 macrophages protecting mice from lethal influenza.35 Additionally, Prnp–/– mice infected with influenza were shown to have a dysregulated immune response with higher IL-6, IFNγ, and TNFα levels, which led to weight loss, higher viral titers, and mortality.36 In contrast to infection with influenza, we observed similar frequencies and numbers of effector CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice compared with WT, and all mice survived the LCMV Armstrong infection. This phenotype is consistent with a prior study that also showed that virus-specific CD8+ T cells in Prnp–/– mice were similar to WT early after infection.39 However, we observed higher frequencies and numbers of memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells postinfection. Together, these studies show that PrPc plays an important role in regulating T cells, and outcomes of the response can vary depending on the antigen. These studies, including ours, show that cellular prion proteins are a negative regulator of the T cell response that limits the differentiation, proliferation, and accumulation of virus-specific memory T cells.

Collectively, these findings underscore the intricate regulatory role of prion proteins in shaping the differentiation, proliferation, and numbers of cytokine-producing virus-specific T cells during acute viral infection. Future studies exploring the underlying mechanisms and delineating cell-intrinsic vs. cell-extrinsic effects of prion proteins on antiviral T cell responses are warranted. Such investigations hold promise for unraveling novel therapeutic strategies aimed at harnessing the immune-modulatory properties of prion proteins in combating viral infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the current and former members in the Tinoco Laboratory for all their constructive comments and advice during this project.

Contributor Information

Karla M Viramontes, Center for Virus Research, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Charlie Dunlop School of Biological Sciences, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States.

Melissa N Thone, Center for Virus Research, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Charlie Dunlop School of Biological Sciences, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States.

Julia M DeRogatis, Center for Virus Research, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Charlie Dunlop School of Biological Sciences, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States.

Emily N Neubert, Center for Virus Research, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Charlie Dunlop School of Biological Sciences, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States.

Monique L Henriquez, Center for Virus Research, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Charlie Dunlop School of Biological Sciences, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States.

Jamie-Jean De La Torre, Center for Virus Research, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Charlie Dunlop School of Biological Sciences, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States.

Roberto Tinoco, Center for Virus Research, Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Charlie Dunlop School of Biological Sciences, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States.

Author contributions

R.T. conceived, designed, directed, and obtained funding for the project. K.M.V. and R.T. designed and analyzed experiments, K.M.V., M.N.T., and R.T. wrote the manuscript. K.M.V. carried out and led all experiments with help from M.N.T., J.M.D, E.N.N., M.L.H. and J.-J.D.L.T. All authors provided feedback and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 AI137239 to R.T.), a T32 Microbiology and Infectious Diseases training grant (T32AI141346 to K.M.V.), NIH Initiative for Maximizing Student Development training grant (GM055246 to K.M.V.), a National Cancer Institute Interdisciplinary Cancer Research Training Grant (T32CA009054 to M.N.T. and J.M.D.), a T32 virus-host interactions: a multi-scale training program grant (T32AI007319 to E.N.N.), and a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/NIH Interdisciplinary Skin Biology Training Program grant (T32AR080622 to J.-J.D.L.T.).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Butz EA, Bevan MJ. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity. 1998;8:167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Badovinac VP, Porter BB, Harty JT. Programmed contraction of CD8(+) T cells after infection. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wherry EJ et al. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaech SM, Hemby S, Kersh E, Ahmed R. Molecular and functional profiling of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Cell. 2002;111:837–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barski A et al. Rapid recall ability of memory T cells is encoded in their epigenome. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flynn KJ et al. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary influenza pneumonia. Immunity. 1998;8:683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lukens MV et al. Characterization of the CD8+ T cell responses directed against respiratory syncytial virus during primary and secondary infection in C57BL/6 mice. Virology. 2006;352:157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Memory CD8 T-cell differentiation during viral infection. J Virol. 2004;78:5535–5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gray SM, Kaech SM, Staron MM. The interface between transcriptional and epigenetic control of effector and memory CD8(+) T-cell differentiation. Immunol Rev. 2014;261:157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaech SM, Cui W. Transcriptional control of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:749–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Milner JJ et al. Delineation of a molecularly distinct terminally differentiated memory CD8 T cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:25667–25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sallusto F, Lenig D, Förster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Linden R. The biological function of the prion protein: a cell surface scaffold of signaling modules. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang CC, Steele AD, Lindquist S, Lodish HF. Prion protein is expressed on long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells and is important for their self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2184–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamasaki T, Suzuki A, Hasebe R, Horiuchi M. Flow cytometric detection of PrP(Sc) in neurons and glial cells from prion-infected mouse brains. J Virol. 2018;92: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moser M, Colello RJ, Pott U, Oesch B. Developmental expression of the prion protein gene in glial cells. Neuron. 1995;14:509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goodbrand IA, Ironside JW, Nicolson D, Bell JE. Prion protein accumulation in the spinal cords of patients with sporadic and growth hormone associated Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurosci Lett. 1995;183:127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gibbs CJ Jr et al. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (spongiform encephalopathy): transmission to the chimpanzee. Science. 1968;161:388–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Will RG et al. A new variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in the UK. Lancet. 1996;347:921–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ma J, Wang F. Prion disease and the 'protein-only hypothesis'. Essays Biochem. 2014;56:181–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Griffith JS. Self-replication and scrapie. Nature. 1967;215:1043–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McKinley MP, Bolton DC, Prusiner SB. A protease-resistant protein is a structural component of the scrapie prion. Cell. 1983;35:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bueler H et al. Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature. 1992;356:577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prusiner SB et al. Ablation of the prion protein (PrP) gene in mice prevents scrapie and facilitates production of anti-PrP antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10608–10612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Manson JC et al. 129/Ola mice carrying a null mutation in PrP that abolishes mRNA production are developmentally normal. Mol Neurobiol. 1994;8:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu T et al. Normal cellular prion protein is preferentially expressed on subpopulations of murine hemopoietic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:3733–3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kubosaki A et al. Distribution of cellular isoform of prion protein in T lymphocytes and bone marrow, analyzed by wild-type and prion protein gene-deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ingram RJ et al. A role of cellular prion protein in programming T-cell cytokine responses in disease. FASEB J. 2009;23:1672–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mabbott NA, Brown KL, Manson J, Bruce ME. T-lymphocyte activation and the cellular form of the prion protein. Immunology. 1997;92:161–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cashman NR et al. Cellular isoform of the scrapie agent protein participates in lymphocyte activation. Cell. 1990;61:185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu W et al. Pharmacological prion protein silencing accelerates central nervous system autoimmune disease via T cell receptor signalling. Brain. 2010;133:375–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsutsui S, Hahn JN, Johnson TA, Ali Z, Jirik FR. Absence of the cellular prion protein exacerbates and prolongs neuroinflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1029–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alais S et al. Functional mechanisms of the cellular prion protein (PrP(C)) associated anti-HIV-1 properties. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:1331–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chida J et al. Prion protein signaling induces M2 macrophage polarization and protects from lethal influenza infection in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chida J et al. Prion protein protects mice from lethal infection with influenza A viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bachmann MF, Wolint P, Schwarz K, Jäger P, Oxenius A. Functional properties and lineage relationship of CD8+ T cell subsets identified by expression of IL-7 receptor alpha and CD62L. J Immunol. 2005;175:4686–4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martin MD, Badovinac VP. Defining memory CD8 T cell. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Genoud N et al. Disruption of Doppel prevents neurodegeneration in mice with extensive Prnp deletions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4198–4203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.