Abstract

Background

Stuttering development in preschool children might be influenced by parents' concern, awareness and knowledge. Indirect treatment may therefore be appropriate. Intervention in a group format has been shown to be positive for stuttering and an online procedure increases the accessibility of the intervention.

Aims

The aim of this study was to investigate whether an online indirect group treatment for children who stutter could increase parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering, reduce the impact of stuttering on the child and parents as well as reduce stuttering severity.

Methods and Procedures

All children having an ongoing contact with a speech‐language pathologist at the included clinics and meeting the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. The participants were five families with children, aged 3:7–4:5, who had been stuttering for at least 12 months. Treatment consisted of six weekly online group sessions for parents, followed by 15 weeks of home consolidation. A single‐subject research design replicated across participants was used to investigate changes over baseline, treatment and consolidation phase. The outcome measures were Palin Parent Rating Scales and severity ratings of stuttering reported by parents. Mean values of each week's daily parent ratings of stuttering were used and converted to defined scale steps. Changes in all variables were visually analysed for each participant. Scale steps representing the mean values from baseline measurements were compared with those from the consolidation phase to analyse changes in scale steps (clinical relevance).

Outcome and Results

The findings indicate increased parents’ knowledge about stuttering and confidence in how to support their child, as well as a positive trend in the impact of stuttering on child and parents, and stuttering severity, during the intervention. The size of the changes in the included outcome measures (e.g., from low to high or very high) varied between participants. The changes were clinically relevant in one to three, out of four, outcome measures for each child, also for those at risk of persistent stuttering.

Conclusions and Implications

The online group format can be an effective way to increase parents’ ability to handle the child's stuttering at an early stage. Further studies are needed to ensure what treatment effects can be expected, following this indirect online format.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

What is already known on the subject

Indirect therapy involving parents has been shown to benefit preschool children who stutter. These therapies typically include providing information about stuttering, teaching strategies for managing stuttering and improving overall communication skills.

What this paper adds to existing knowledge

This study evaluates a novel form of online group therapy (involving five families) which has not been previously studied. The results demonstrate that most of the parents gain knowledge and confidence in managing their child's speech disorder. Additionally, some parents report a reduced negative impact of stuttering on both the child and the family after the treatment.

What are the potential or actual clinical implications of this work?

This approach can be a valuable tool for speech and language therapists working with preschool children who stutter. The online format offers a practical option for families who face challenges attending in‐person sessions, while also providing opportunities to connect with other parents in similar situations.

Keywords: clinically relevant change, group treatment, online treatment, parental skills, preschool children, single‐subject design, stuttering

INTRODUCTION

Stuttering is a neurodevelopmental disorder, and the primary symptoms are speech disfluencies (Smith & Weber, 2017). According to the multifactorial dynamic pathways theory (Smith & Weber, 2017) stuttering usually begins when the neural networks, which support language, speech and emotional functions, develop. Rapid changes in these systems can have an impact on the development of stuttering. The incidence of stuttering in childhood is 5%–8% and the life span prevalence is <1% (Yairi & Ambrose, 2013). The indications if a child's stutter will persist or recover might be seen during the first year from onset, but the recovery process tends to be completed during the second or third year (Sugathan & Maruthy, 2021). A review by Sugathan and Maruthy (2021) suggests that a sharp decline in stuttering 1 year after onset indicates a higher chance of transient stuttering. Children with poor phonological abilities and a stable nature of stuttering 1 year post onset tend to be at higher risk for persistent stuttering. Studies of family history of stuttering, onset and gender have reported contradictory findings (Sugathan & Maruthy, 2021).

Stuttering can affect the ability to communicate from an early age. According to parental reports, children as young as 2 years old have been found to be aware of stuttering and children's reactions to their stuttering increase with age and stuttering severity (Boey et al., 2009). Children who stutter have more negative attitudes towards communication compared to children who do not stutter (Clark et al., 2012; Vanryckeghem et al., 2005) and are more likely to experience emotional, behavioural and social difficulties than non‐stuttering children (McAllister, 2016). Stuttering may not only have an impact on the child but also the parents. Langevin and colleagues (2010) report that the majority of the parents in their study were affected by their child's stuttering. The parents expressed anxiety, frustration, self‐blame and uncertainty about what to do about the child's stuttering. Berquez and Kelman (2018) report that even parents of children who have been stuttering only for a short time worry about their child's well‐being, risk of bullying and future relationships and employment.

There are several options available to assess outcome related to stuttering intervention in young children. The Palin Parent Rating Scales (Palin PRS) were developed by Millard and Davis (2016) to provide researchers or clinicians with information regarding the child's stuttering beyond the clinic. The generated data can be used to support decisions about therapy and to evaluate progress over time. Palin PRS is a standardised measure that consists of total 19 items divided into three component factors: Factor 1: Impact of Stuttering on the Child (7 items), Factor 2: Severity of Stuttering and Impact on the Parents (7 items) and Factor 3: Parents’ Knowledge and Confidence in Managing the Stuttering (5 items). Internal consistency for each scale has been studied and the results indicate that the Palin PRS is a reliable tool for parents of children under 7:0 years and aged 7:0–14:6 years (Millard & Davis, 2016). Another way to obtain information about stuttered speech outside clinic is parent‐reported severity rating (SR). Parent‐reported SR is considered highly appropriate as an outcome measure in intervention for young children who stutter (Onslow et al., 2018).

For preschool children, there are several options for intervention (Shenker & Santayana, 2018), indirect methods (Franken & Laroes, 2021; Kelman & Nicholas, 2020) and direct methods (Onslow et al., 2021). Intervention is indicated if parents are worried and request help to support their child, and/or if the stuttering has a negative impact on the child's ability to communicate and well‐being (Millard et al., 2018). Therefore, therapy should not only be offered to children whose stuttering seems to be firmly established. Berquez and Kelman (2018) suggest that the clinical focus in therapy for children who stutter might include increasing openness and parents’ understanding about stuttering as well as exploring parents’ emotional responses to their child's stuttering.

It is important to involve parents in stuttering treatment for children of all ages. This is because a child's stuttering often affect the parents, and their reactions might also have an impact on the development of stuttering (Berquez & Kelman, 2018). RESTART‐Demands and Capacities Model (RESTART‐DCM) and Palin Parent Child Interaction Therapy (Palin PCIT) are both indirect treatment approaches, involving parents, for young children who stutter (Franken & Laroes, 2021; Kelman & Nicholas, 2020). The online indirect group treatment in the present study was based on these methods. In indirect methods parents focus on changes in environment and verbal interactions with the child (Berquez & Kelman, 2018; Millard et al., 2018). The assumption is that parents may facilitate fluency by understanding their own emotional and behavioural reactions to their child's stuttering and making modifications in their everyday life. According to Packman the primary role of indirect treatment procedures is to raise the threshold at which moments of stuttering are triggered (Packman, 2012). Indirect treatment is directed to modulating factors, such as reducing time pressure and other environmental demands.

The impact of sharing similar experiences with other people (universality), interpersonal learning, and having the opportunity to offer support to each other (altruism) are all therapeutic factors which are unique for group therapy (Yalom and Leczsc, 2005). Studies have reported that parents appreciate the opportunity to connect with other parents who have children with similar difficulties as well as share their own experiences and learn from each other (Levickis et al., 2020; Rensfeldt Flink et al., 2020). Indirect intervention in a group format might also be a cost‐effective alternative to individual treatment (Boyle et al., 2007).

Online treatment can ensure families to receive equal care regardless distance to specialist services or other aggravating circumstances (O'Brian et al., 2014). Lowe and colleagues (2013) conclude that telehealth is a potential contribution to stuttering treatment but highlight the need of more research in the area to evaluate the eventual cost benefit and to develop clinical guidelines, to ensure an equivalent standard to in‐clinic treatment. For preschool children who stutter it is necessary to further explore effects and efficiency of telehealth methods. A systematic review by McGill and colleagues (2019) found only a few studies on stuttering treatment using live‐streamed video telepractice. Given the limited research on this topic McGill and colleagues suggest more studies concerning the effects of online treatment, randomised controlled trials as well as single‐subject designs.

As already described stuttering can have a high impact on children and parents already a short time after onset, and therapy should therefore not only be offered to children whose stuttering seems to be firmly established. An online indirect group treatment for parents of children who stutter might be an effective way to reach many parents with information and understanding of how to handle the child's stuttering at an early stage. An increased awareness about interaction strategies and factors affecting stuttering are expected to have a positive impact on the interaction with the child. This, in turn, is hypothesised to improve the child's confidence in speaking situations, reduce stuttering severity and decrease parents’ anxiety level. Hence, the aim of this study was to explore whether an online indirect group treatment for children who stutter could increase parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering, reduce the impact of stuttering on the child and parents as well as reduce stuttering severity. The research question was: Does the online indirect group treatment affect the following variables, and if so, how?

The parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing stuttering

The impact of stuttering on the child

The severity of the child's stuttering

The impact of stuttering on the parents

METHOD

The objective of the present study was to describe and evaluate an online indirect group treatment for preschool children who stutter. In doing so eventual changes in parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing stuttering, impact of stuttering (on children and parents) as well as stuttering severity were investigated. All variables were analysed as single cases and with regard to clinically relevant changes.

Setting and design

This study was conducted at a speech‐language pathology clinic within the region of XXX that receives referrals from child health care centres and other speech‐language pathology clinics. The study was a single‐case design replicated across participants and consisted of three phases, baseline (A), treatment (B) and consolidation (C).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (no 2022‐01137‐01).

Participants

The recruitment process lasted for 3 months, and the target was to find six families who could participate in the study. All children having an ongoing contact with a speech‐language pathologist (SLP) within the Health Care Services in XXX, and meeting the inclusion criteria, were invited to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows.

The child should

be below the age of 4:6 years at the start of the study.

have stuttered for a minimum of 12 months.

have been diagnosed by an SLP with high competence in fluency disorders.

not previously participated in a stuttering treatment program.

speak Swedish as the main language at home.

Many children did not meet the criteria and some parents declined intervention because of low incentive, due to their child's mild stuttering. Finally, five families decided to take part in the study. Information about predictive factors, such as family history of stuttering and trend in stuttering development, was collected from the parents and will be discussed in relation to the specific child's treatment outcome (see Table 1). Pseudonyms were used.

TABLE 1.

Summary information about the children.

| Child | Age a | Onset b | Time c | Development d | Heredity e | SSD f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emma | 3:10 | 2:5 | 17 | Decline | No | No |

| Gabriel | 3:7 | 2:6 | 13 | Decline | Yes (p) | Yes |

| Julian | 4:5 | 3:5 | 12 | Varying | Yes (p) | Yes |

| Olivia | 4:3 | 2:3–3:3 | 12–24 | Varying | Yes | No |

| William | 4:0 | 2:11 | 13 | Stable | Yes | No |

Age at start of the study y:m.

Reported onset of stuttering y:m.

Time since reported onset of stuttering in months.

Parents’ description of stuttering development since onset.

History of stuttering in the family (p = persistent).

Speech sound disorder according to SLP assessment.

Abbreviations: SLP, speech‐language pathologist; SSD, speech sound disorder.

Seven out of 10 parents completed all ratings (Palin PRSs and SR of stuttering) during the study period. One family failed to complete their Palin PRSs twice (B and C1), and two parents failed to fill in the last page of Palin PRSs one time each (A1, B). One parent (Gabriel's father) could not attend either the six group sessions during treatment phase, or the last session in group during consolidation phase. The father received the information from the mother, and the written material, and participated in the treatment at home. In the end of the study period, the parents (n = 8) answered questions regarding compliance to the treatment (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary information about the parents’ participation in the group sessions and their compliance with the treatment during consolidation phase.

| Child | Group sessions a | Parent child time b | Everyday conversations c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emma | Both (5;4) | Often | Often/very often |

| Gabriel | One (5;0) | Often | Very often |

| Julian | Both (7;5) | Sometimes/often | Often |

| Olivia | Both (5;5) | Very often | Very often |

| William | Both (7;5) | Sometimes/often | Very often |

The parents’ participation in group treatment (number of participated sessions for each parent, mother; father).

How often the child got Parent Child Time during consolidation phase according to the parents’ answer in the written evaluation (Very often, Often, Sometimes, Seldom, Never).

How often the parents followed interaction strategies in everyday conversations during consolidation phase according to the parents’ answer in the written evaluation (Very often, Often, Sometimes, Seldom, Never).

Procedure

Intervention

The treatment was based on indirect methods for children who stutter, namely, Palin PCIT (Kelman & Nicholas, 2020) and RESTART‐DCM (Franken & Laroes, 2021). The most salient similarities with these methods were the core components Parent Child Time and Interaction strategies.

The parents of the children who stutter participated in the online indirect group treatment under the direction of two SLPs working with fluency disorders, of whom one was the first author. The treatment took place once a week, 75‐min sessions, during a period of 6 weeks. The targets of the treatment were to increase parents’ confidence about how to handle the child's stuttering and increase the child's confidence in communicating, as well as to reduce the severity rate of the child's stuttering and parental anxiety.

The main focus in the treatment was structured discussions about why different interaction strategies might be helpful and how the parents could implement these strategies at home. A new strategy was presented each week (see Table 3) and a compendium, developed by the first author, with information about the interaction strategies was distributed prior to the treatment. During the sessions parents also received general information about stuttering and factors that might have an impact on the child's stuttering, through short lectures and group discussions where parents exchanged thoughts, feelings and experiences (see themes in Table 3). The discussions, together with all other treatment components, aimed to increase the parents’ understanding about childhood stuttering and reduce their anxiety.

TABLE 3.

Overview of the online indirect group treatment for preschool children who stutter.

| Week | Interaction strategies | Theme group discussion |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Follow the child's lead in play | Onset, pattern of change and causal theories of stuttering |

| 2 | Use more comments than questions | Openness about stuttering |

| 3 | Slow down the rate of speech | Routines, pace of life, stress, food and sleep |

| 4 | Give the child time and increase pause time | Turn‐taking |

| 5 | Listen actively | Self‐confidence and self‐esteem |

| 6 | Use language appropriate for the child's level | Needs and requests from the group |

Between sessions the parents were required to alternate practice of home assignments 15 min/day (Parent Child Time), during which the child got undivided attention and the sense of being seen and heard (Franken & Laroes, 2021). The parents were also expected to follow the interaction strategies in everyday conversations. The parents registered every Parent Child Time in a practice chart and at the start of every online treatment session the home assignments were followed up in the group.

After the 6‐week treatment period the intervention continued at home, and every family had additional contacts three times during a period of 15 weeks (consolidation phase). The first two were individual online sessions where the parents were able to get support and communicate experiences and challenges. The last session was in group format, where all parents shared their experiences from the home training period (see Table 4 for distribution of all sessions).

TABLE 4.

Summary of treatment sessions and data collection points.

| Baseline (A) | Treatment (B) | Consolidation (C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| Treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group a | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Individual b | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SR c | A1 | A2 | A3 | B | C1 | C2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PRS‐S d | A1 | A2 | A3 | B | C1 | C2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The parents participated in the group treatment once a week during Treatment phase (marked with X).

The parents had additional contacts three times during Consolidation phase (marked with X).

The parents rated stuttering severity (SR) daily during six separate weeks (week 1 = A1, week 5 = A2, week 9 = A3, week 15 = B, week 23 = C1 and week 30 = C2).

The parents completed Palin Parent Rating Scales (PRS‐S) six times each (week 1 = A1, week 5 = A2, week 9 = A3, week 15 = B, week 23 = C1 and week 30 = C2) during the study period.

Outcome measures

Two different measurements were used to answer the research question, the Palin PRS‐Swedish (PRS‐S) and SR. The four variables were measured as follows:

The parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing stuttering: Factor 3 PRS‐S (all 5 items)

The impact of stuttering on the child: Factor 1 PRS‐S (all 7 items)

The severity of the child's stuttering: SR

The impact of stuttering on the parents: Factor 2 PRS‐S (3 selected items)

In the present study the parents completed the Swedish version of the Palin PRSs, PRS‐S, individually (Malmström & Tidelius, 2018). Due to General Data Protection Regulation the data protection officer within the region did not allow parents to use the online version of the questionnaire. A paper version was therefore produced with permission of the authors. The parents answered the questions by selecting a number between 0 and 10 on the scale, and then returned the filled‐out questionnaire to the researcher by post. The online version of the Palin PRS was then used, with fictive patients, to convert raw scores to weighted factor scores (0–10), stanine score and category ratings (Very high, High, Moderate, Low, Very low).

The parents rated the severity of their child's stuttering (SR) together on a scale between 0 and 9, where 0 = no stuttering, 1 = extremely mild stuttering and 9 = extremely severe stuttering (Onslow et al., 2021). In an individual session, just before the start of the baseline phase, the parents were instructed on how to use the scale and record SRs. Examples from the child's previous SLP assessments were used as anchors for perceptual reference. The parents made SR for the speech they heard during the day, and the ratings should reflect the typical speech. Parents sent their ratings by text messages to the first author.

The concept of clinical significance can be defined as ‘a recognizable treatment change that is valued by the clinician, client, and relevant others’ (Finn, 2003, p. 215). Millard and colleagues (2018) suggested criteria for a clinically significant change as a positive shift from one category to another on Palin PRS, for example, a reduction from High to Moderate impact on the child (Factor 1). In this study, similar criteria were used for the three factors in Palin PRS‐S. Since no equivalent criteria were found for SR in the literature, the same definition was used for this variable. Thus, a positive shift from one category to another was considered clinically relevant, for example, a reduction from Moderate to Mild severity. The concept clinically ‘significant/meaningful’ can be equated with clinically ‘relevant’, which is the term used in the present study.

Data analysis

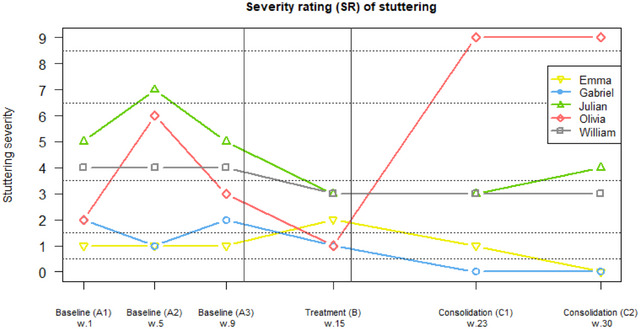

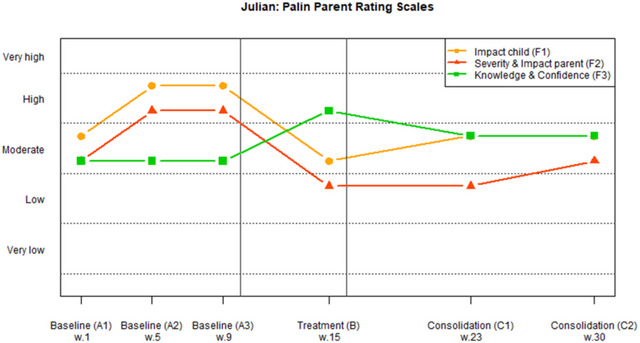

When presenting the results of stuttering SR (Figure 1) mean values for each week of the parents’ daily ratings were used. In accordance with Onslow and colleagues (2021) the parents rated stuttering severity on a scale of 0–9, where only 0, 1 and 9 were labelled. However, in the result section ratings are represented by the following labels: 0 = no stuttering, 1 = extremely mild stuttering, 2–3 = mild stuttering, 4–6 = moderate stuttering, 7–8 = severe stuttering, 9 = extremely severe stuttering, in order to determine whether an eventual shift was clinically relevant or not. When presenting the results of Palin PRS (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6), mean values of the ratings from both parents’ individual ratings were used. Individual ratings in stanine are found in Table 5.

FIGURE 1.

Mean values for each week (1, 5, 9, 15, 23, 30) of parents’ daily severity rating (SR) of stuttering (0 = no stuttering, 1 = extremely mild stuttering, 2–3 = mild stuttering, 4–6 = moderate stuttering, 7–8 = severe stuttering 9 = extremely severe stuttering).

FIGURE 2.

Emma's parents’ mean ratings on Palin PRS‐S for week 1, 5, 9, 15, 23 and 30. For Factor 1 ‘Impact of stuttering on the child’ and Factor 2 ‘Severity of stuttering and impact on the parents’ a decrease indicates an improvement. For Factor 3 ‘Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering’ an increase indicates an improvement. Abbreviation: PRS‐S, Parent Rating Scales‐Swedish.

FIGURE 3.

Gabriel's parents’ mean ratings on Palin PRS‐S for week 1, 5, 9, 15, 23 and 30. For Factor 1 ‘Impact of stuttering on the child’ and Factor 2 ‘Severity of stuttering and impact on the parents’ a decrease indicates an improvement. For Factor 3 ‘Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering’ an increase indicates an improvement. Abbreviation: PRS‐S, Parent Rating Scales‐Swedish.

FIGURE 4.

Julian's parents’ mean ratings on Palin PRS‐S for week 1, 5, 9, 15, 23 and 30. For Factor 1 ‘Impact of stuttering on the child’ and Factor 2 ‘Severity of stuttering and impact on the parents’ a decrease indicates an improvement. For Factor 3 ‘Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering’ an increase indicates an improvement. Abbreviation: PRS‐S, Parent Rating Scales‐Swedish.

FIGURE 5.

Olivia's parents’ mean ratings on Palin PRS‐S for week 1, 5, 9, 15, 23 and 30. For Factor 1 ‘Impact of stuttering on the child’ and Factor 2 ‘Severity of stuttering and impact on the parents’ a decrease indicates an improvement. For Factor 3 ‘Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering’ an increase indicates an improvement. Abbreviation: PRS‐S, Parent Rating Scales‐Swedish.

FIGURE 6.

William's parents’ mean ratings on Palin PRS‐S for week 1, 5, 9, 15, 23 and 30. For Factor 1 ‘Impact of stuttering on the child’ and Factor 2 ‘Severity of stuttering and impact on the parents’ a decrease indicates an improvement. For Factor 3 ‘Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering’ an increase indicates an improvement. Abbreviation: PRS‐S, Parent Rating Scales‐Swedish.

TABLE 5.

Overview of the collected data in five color‐coded categories.

| Palin Parent Rating Scales (stanine) | Severity Rating (0–9) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Impact child’ (F1) a | ‘Severity & Impact parent’ (F2) b | ‘Knowledge & confidence’ (F3) c | Mean (min‐max) d | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Baseline | Treatment | Consolidation | Baseline | Treatment | Consolidation | Baseline | Treatment | Consolidation | Baseline | Treatment | Consolidation | |||||||||||||

| Participant | A1 | A2 | A3 | B | C1 | C2 | A1 | A2 | A3 | B | C1 | C2 | A1 | A2 | A3 | B | C1 | C2 | A1 | A2 | A3 | B | C1 | C2 |

| Emma | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mother | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| father | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 6 | * | 8 | 9 | (1–2) | (0–2) | (0–2) | (1–3) | (1–2) | (0–1) |

| Gabriel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mother | 6 | 9 | 7 | * | * | 7 | 7 | 9 | 8 | * | * | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | * | * | 9 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| father | 6 | 8 | 5 | * | * | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | * | * | 8 | * | 9 | 6 | * | * | 8 | (1–4) | (1–2) | (1–3) | (1–2) | (0–1) | (0–1) |

| Julian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mother | 6 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| father | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (3–7) | (6–8) | (4–6) | (2–4) | (2–3) | (3–4) |

| Olivia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mother | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 9 |

| father | 8 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | (1–3) | (4–7) | (2–4) | (1–2) | (8–9) | (8–9) |

| William | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mother | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| father | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (4) | (4) | (4) | (3–4) | (3–4) | (2–3) |

Note: Green indicates the lowest impact or severity rating and the highest knowledge and confidence. Red indicates the highest impact or severity rating and the lowest knowledge and confidence.

Factor 1: Impact of stuttering on the child (Stanine 1–2: Very high impact, Stanine 3–4: High impact, Stanine 5–6: Moderate impact, Stanine 7–8: Low impact, Stanine 9: Very low impact).

Factor 2: Severity of stuttering and impact on the parents (Stanine 1–2: Very high impact, Stanine 3–4: High impact, Stanine 5–6: Moderate impact, Stanine 7–8: Low impact, Stanine 9: Very low impact).

Factor 3: Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering (Stanine 1–2: Very low, Stanine 3–4: Low, Stanine 5–6: Moderate, Stanine 7–8: High, Stanine 9: Very high).

Mean of the parents’ daily ratings of stuttering severity (0 = No stuttering, 1 = Extremely mild stuttering, 2–3 = Mild stuttering, 4–6 = Moderate stuttering, 7–8 = Severe stuttering, 9 = Extremely severe stuttering).

Missing data.

In order to determine whether the changes were clinically relevant, mean values of the parents’ individual ratings on Palin PRS‐S for A1, A2 and A3 in baseline phase, were compared to final ratings in consolidation phase (C2). Mean values of the parents’ daily ratings of stuttering severity for A1, A2 and A3 in baseline phase were compared to final ratings in consolidation phase (C2) to determine whether the changes in severity were clinically relevant.

Since Factor 2 in Palin PRS measures both stuttering severity and impact on parents, there are no outcome measures about the impact on parents only. Therefore, the raw scores on question 5–7 (i.e., three selected items from Factor 2, Palin PRS‐S), regarding parental anxiety, were analysed separately in order to see changes in that specific domain (Table 6). Mean values of the parents’ individual ratings for A1, A2 and A3 in baseline phase, and mean values of the parents’ individual ratings on Palin PRS‐S for C2 in consolidation phase are displayed in the result.

TABLE 6.

Mean values of the parents’ ratings on items regarding the impact of stuttering on the parents (Factor 2, Palin PRS).

| The impact of stuttering on the parents a | ||

|---|---|---|

| Child | Baseline (A1, A2, A3) b | Consolidation (C2) c |

| Emma | 9 (7–10) | 10 (9–10) |

| Gabriel | 7 (6–10) | 8 (7–9) |

| Julian | 4 (0–7) | 6 (5–7) |

| Olivia | 8 (4–10) | 5 (1–9) |

| William | 8 (6–10) | 8 (7–9) |

Note: Grey colour indicates a positive change from baseline to consolidation.

Three questions in Palin PRS measures the impact of stuttering on the parents: ‘How worried are you about your child's stuttering?’, ‘How anxious are you about your child's future because of the stuttering?’ and ‘How much of an impact does the stuttering have on your family?’.

Mean values of raw score of the parent's ratings in A1, A2 and A3, 0 = as much as I/it could, 10 = not/none at all, (min‐max).

Mean values of raw score of the parent's ratings in C2, 0 = as much as I/it could, 10 = not/none at all, (min‐max).

Abbreviation: PRS, Parent Rating Scales.

Overview of procedures

The baseline phase (A) lasted for 9 weeks. The parents were required to rate the stuttering SR daily, during 3 separate weeks, and complete Palin PRS‐S three times each (see Table 4). The families did not receive any intervention during this phase. The treatment phase (B) then went on for 6 weeks. During the last week of the treatment phase the parents rated the severity of the child's stuttering daily and completed Palin PRS‐S once. Finally, the consolidation phase (C) lasted 15 weeks, thus the total duration of the study was 6 months. The parents continued to treat the child daily and followed the interaction strategies they had learned in the group treatment. During two separate weeks the parents rated the severity of the child's stuttering daily and completed Palin PRS‐S two times each. The first author reminded the parents to start record SRs and to complete Palin PRS by text messages.

RESULTS

In the following, results for SRs are presented for all children in Figure 1, and the results from PRS‐S are presented for each individual child in Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Because the parents’ values are linked to a specific child, which represents one specific case in the study, the figures mean values for each child's parent dyad are displayed. An overview of all results (including separate ratings from each individual in the parent dyad) for all children can be found in Table 5.

Emma

Emma had been stuttering for 1 year and 5 months when the study started, and the parents described a decline in stuttering severity since onset. There was no history of stuttering in the family and Emma had no speech sound disorder (SSD).

Emma had a Mild/Extremely mild stuttering during all phases and was stutter free the last week (C2) in consolidation (see Figure 1). As seen in Table 5 there are missing data for Factor 3 Palin PRS‐S (B). Figure 2 illustrates that the impact of stuttering on the child (Factor 1) decreased from Moderate/Low during baseline to Low/Very low in consolidation (C1 and C2). Factor 2, Severity of stuttering and impact of stuttering on parents, decreased from Low/Very low during baseline to Very low in consolidation. Factor 3, Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering increased from Low to Very high. The changes were clinically relevant for three out of four outcome measures: ‘Knowledge & Confidence’, ‘Impact child’ and ‘Stuttering Severity Rating’.

Gabriel

Gabriel had been stuttering for about a year when the study started, and the parents described a decline in stuttering severity since onset. There was a history of persistent stuttering in the family (Gabriel's father) and Gabriel had SSD according to SLP assessment.

Stuttering severity changed from Mild/Extremely mild to almost stutter free speech during the study period (see Figure 1). As seen in Figure 3 and Table 5 there are missing data for Palin PRS‐S for treatment (B) and consolidation (C1) and Factor 3 PRS‐S (A1). When comparing baseline with C2 the impact of stuttering on the child was Moderate/Low during baseline and Low in C2. Severity of stuttering and impact on parents was Low/Very low during baseline and Very low in C2. Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering increased from High to Very high. The changes were clinically relevant for three out of four outcome measures: ‘Knowledge & Confidence’, ‘Stuttering Severity Rating’ and ‘Severity & Impact parent’.

Julian

Julian had been stuttering for 1 year when the study started, and the parents described that it had been a varying degree of stuttering severity since onset. There was a history of persistent stuttering in the family (Julian's mother's uncle) and Julian had SSD according to SLP assessment.

As seen in Figure 1 the severity of stuttering changed from Severe/Moderate during baseline to Moderate/Mild during C1 and C2. Figure 4 illustrates that the impact of stuttering on the child decreased from High/Moderate during baseline to Moderate in consolidation. Severity of stuttering and impact on parents decreased from High/Moderate during baseline to Moderate/Low in consolidation. Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering increased during the study period but was still in Moderate category. The changes were clinically relevant for two out of four outcome measures: ‘Impact child’ and ‘Severity & Impact parent’.

Olivia

Olivia had been stuttering for 1–2 years when the study started. The parents described that the stuttering had been intermittent, and therefore it was difficult for them to remember the first period of stuttering. There was a history of recovered stuttering in the family (Olivia's grandfather) and Olivia had no SSD.

The severity of stuttering varied from extremely mild to extremely severe during the study period (see Figure 1). As seen in Figure 5 the impact of stuttering on the child increased from Very low/Low during baseline to Moderate in consolidation. The impact of stuttering on the parents increased from Very low/Low during baseline to Moderate/High in consolidation. Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering increased from Very low to Moderate. The changes were clinically relevant for one out of four outcome measures: ‘Knowledge & Confidence’.

William

William had been stuttering for about a year when the study started, and the parents described a stable degree of stuttering severity since onset. There was a history of stuttering in the family (William's older sister) and William had no SSD.

As seen in Figure 1 the severity of stuttering decreased from Moderate during baseline to Mild in consolidation. Figure 6 illustrates that the impact on the child was Moderate/Low during baseline and Low in consolidation. Severity of stuttering and impact on parents decreased from Low to Low/Very low. Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering increased from Moderate to High. The changes were clinically relevant for three out of four outcome measures: ‘Knowledge & Confidence’, ‘Impact child’ and ‘Stuttering Severity Rating’.

Summary of clinically relevant changes

For four families there was a clinically relevant increase in parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering (see Table 7). For three out of five children there was a clinically relevant reduction in the impact of stuttering on the child. For three children there was a clinically relevant reduction in parents’ ratings of stuttering severity. For two of the families there was a clinically relevant reduction in the severity of stuttering and impact of stuttering on the parents.

TABLE 7.

Summary of clinically relevant changes for all outcome measures.

|

‘Knowledge & confidence’ a (Factor 3, PRS‐S) |

‘Impact child’ a (Factor 1, PRS‐S) |

‘Severity Rating’ b |

‘Severity & impact parent’ a (Factor 2, PRS‐S) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child |

Baseline (A1, A2, A3) |

Consolid. (C2) |

Baseline (A1, A2, A3) |

Consolid. (C2) |

Baseline (A1, A2, A3) |

Consolid. (C2) |

Baseline (A1, A2, A3) |

Consolid. (C2) |

| Emma | Moderate | Very high | Low | Very low | Extr. mild | No stutter. | Very low | Very low |

| Gabriel | High | Very high | Low | Low | Mild | No stutter. | Low | Very low |

| Julian | Moderate | Moderate | High | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High | Low |

| Olivia | Very low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Mild | Extr. severe | Low | High |

| William | Moderate | High | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Mild | Low | Low |

| Total | 4/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | ||||

Note: Grey colour indicates a clinically relevant change.

Category ratings of the three factors of Palin Parent Rating Scales (Very high, High, Moderate, Low, Very low).

Category ratings of stuttering severity rating (No stuttering, Extremely mild, Mild, Moderate, Severe, Extremely severe).

Abbreviations: PRS, Parent Rating Scales; SR, stuttering severity.

The fourth research question concerned the impact of stuttering on the parents. Therefore, the raw scores on Questions 5–7 (Factor 2, Palin PRS‐S), regarding parental anxiety, were analysed separately in order to see changes from baseline to the end of the study period (see Table 6).

The results showed a clinical relevant positive change in the impact of stuttering on the parents during the consolidation phase compared to the baseline.

DISCUSSION

In the present study five families were followed during an online group treatment developed specifically for preschool children who stutter. The findings indicate increased parents’ knowledge about stuttering and confidence in how to support their child, as well as a positive trend in the impact of stuttering on child and parents, and stuttering severity, during the intervention.

The parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering. One of the central targets with this intervention was to increase parents understanding of how to support their child. As expected, most parents (four out of five couples) had a clinically relevant increase in knowledge and confidence in managing their child's stuttering. Findings indicate that this target can be improved for some families even though the child did not have a reduction in severity or impact of stuttering. However, overall, there seems to be a relation between stuttering severity and confidence in parental skills. In indirect treatment, parents have an important role, and increasing their confidence and knowledge about stuttering seems to be one of the core factors for the outcome (Berquez & Kelman, 2018; Millard et al., 2018). Since the present treatment was in a group format, the content should be applicable for a large number of families with children who stutter. Parents learned a variety of interactions strategies and got a broad knowledge about factors that can have an impact on stuttering. During the consolidation period they could choose the most appropriate parts for their specific family and practice at home.

The impact of stuttering on the child. There was a clinically relevant reduction in the impact of stuttering for three of the children. For the child who had an increased impact it was connected to an increase in stuttering severity. In the present study, the reduction in impact on the child might be related to the instructions to the parents, to follow the child's lead and listen actively, and to some of the themes in group conversations (openness about stuttering, self‐confidence and self‐esteem). If parents respond in a supportive way and understand their own reactions, it might contribute to a positive attitude to the child's ability to communicate (Berquez & Kelman, 2018; Guttormsen et al., 2015). During the present study period we only investigated the parents’ perception of the impact of stuttering on the child (Factor 1, Palin PRS). Millard and colleagues (2018) found that parents noticed a reduction in the impact of the child several months later than observed by the child, according to the children's attitude to their own communication. With this in mind, a follow‐up might have added some valuable information.

The severity of the child's stuttering. In three children there was a clinically relevant reduction in stuttering severity. Two of them already had a decline in stuttering severity since onset which could indicate an ongoing spontaneous recovery. In the indirect treatment in present study, parents were encouraged to create a fluency‐inducing environment by following interaction strategies during Parent Child Time, and in everyday conversations. Our findings indicate that the treatment might affect the severity of stuttering, even for children with a less positive prognosis. Three of the children had a positive treatment outcome despite the occurrence of several risk factors for persistent stuttering (e.g., family history of stuttering, SSD and stable pattern since onset; Sugathan & Maruthy, 2021). On the other hand, one child with a family history of stuttering had a very varying degree of stuttering during the study period, which makes it difficult to draw any conclusions regarding the treatment's impact on stuttering severity. However, Millard and colleagues (2018), emphasise that a clinically relevant change in a single factor, for this child ‘Parents’ knowledge and confidence in managing the stuttering’, might be enough to be meaningful for the family.

The impact of stuttering on the parents. When analysing questions regarding impact on parents (see Table 6), and comparing them with rating of stuttering severity, the results show that three families had a reduction in both stuttering severity and parental anxiety. One child had a more severe stuttering in the end of the study period, and the child's parents reported an increased anxiety level. This is in line with the psychometric evaluation of Palin PRS, which indicated that items related to stuttering severity correlated with items related to the impact stuttering had on parents (Millard & Davis, 2016). Hence, the results in the present study show similar tendencies. When analysing factor 2 data demonstrated some differences in individual parents in a dyad (see Table 5). This indicates that stuttering can be experienced and affect parents in different ways. This is a finding that is of interest for further investigation; however, this goes beyond the scope of the present study.

Method discussion

Parent‐reported ratings were chosen as the outcome measures, and the main reason was to obtain observations of the child's fluency outside the clinic during a longer period of time, which may be a more valid measure than percentage of syllables stuttered (Onslow et al., 2018). Parent ratings also include struggle and tension, which is not reflected in stuttering frequency scores (Millard et al., 2018). Nevertheless, because of the variable nature of stuttering in young children it is not possible to know if the results are related to the treatment or to variabilities in the child's stuttering.

The data show differences between the parents’ individual ratings (see Table 5). In the figures mean values for each child's parent dyad are displayed. Mean values were also used in the analyses of clinically relevant changes. This choice meant that an individual parent rating, indicating clinically relevant change, was not considered.

Another limitation is that the first author, who collected and analysed the data, also was one of the SLPs conducting the group treatment. This might have an impact on the interpretation of the results and could also have affected parents’ ratings to be more positive. To avoid multiple roles and bias, the researcher should preferably be independent. The absence of a later follow‐up is also a limitation since there is no information on long‐term outcome of the treatment. It is possible that effects of the indirect treatment became more noticeable after a longer period than 3–4 months.

Clinical implications

Group treatment might be a suitable alternative to individual intervention since similar strategies are often helpful for different families. The online group format inhibited an individual focus and control, but on the other hand, enabled parents to connect with each other, which has been shown to be meaningful in previous studies (Levickis et al., 2020; Rensfeldt Flink et al., 2020). Hence, the possibility to participate in discussions with other parents of children who stutter might, for some parents, be as valuable as getting individual feedback and adjustments from the SLP.

Based on observations during the group sessions, the verbal activity in the group varied. For some parents, an in‐clinic group might have been a better option, since an online format can affect turn‐taking and eye contact in a negative way. On the other hand, this could have prevented participation for some parents, due to circumstances, such as work hours, long distances etc., and thus they declined intervention. The online format increases the accessibility and can be an alternative or a complement to in‐clinic treatment programs.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings indicate increased parents’ knowledge about stuttering and confidence in how to support their child, as well as a positive trend in stuttering severity, and the impact of stuttering on child and parents, during the intervention. These changes were reflected in clinically relevant and positive changes in one to three, out of four, outcome measures for each child, even for those at risk of persistent stuttering. The variable nature of stuttering and the chance of spontaneous recovery makes it difficult to know if the reduction in stuttering severity was primarily related to the treatment. The online format increases accessibility, and the group format enables parents to connect with each other. The format presented in this study can be an effective way to increase parents’ ability to handle the child's stuttering at an early stage. The treatment can be an alternative or a complement to in‐clinic treatment programs, but a line of replication studies is needed in order to generalise the results to the population of preschool children who stutter.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no conflict of interest and are solely responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Gembäck, C. , McAllister, A. , Femrell, L. & Lagerberg, T.E. (2025) Online indirect group treatment for preschool children who stutter—effects on stuttering severity and the impact of stuttering on child and parents. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 60, e70008. 10.1111/1460-6984.70008

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Berquez, A. & Kelman, E. (2018) Methods in stuttering therapy for desensitizing parents of children who stutter. American Journal of Speech‐Language Pathology, 27, 1124–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boey, R.A. , Van de Heyning, P.H. , Wuyts, F.L. , Heylen, L. , Stoop, R. & De bodt, M.S. (2009) Awareness and reactions of young stuttering children aged 2–7 years old towards their speech disfluency. Journal of Communication Disorders, 42, 334–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle J., Mccartney E., Forbes J. & O'hare A. (2007) A randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of direct versus indirect and individual versus group modes of speech and language therapy for children with primary language impairment. Health Technology Assessment, 11(25), 1–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C.E. , Conture, E.G. , Frankel, C.B. & Walden, T.A. (2012) Communicative and psychological dimensions of the KiddyCAT. Journal of Communication Disorder, 45, 223–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn, P. (2003) Evidence‐based treatment of stuttering: II. Clinical significance of behavioral stuttering treatments. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 28, 209–218. 10.1016/S0094-730X(03)00039-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken, M.C. & Laroes, E. (2021) Restart‐DCM Method. Available from: https://www.restartdcm.nl

- Guttormsen, L.S. , Kefalianos, E. & Næss, K.‐A.B. (2015) Communication attitudes in children who stutter: a meta‐analytic review. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 46, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, E. & Nicholas, A. (2020) Palin Parent Interaction Therapy for early childhood stammering, 2nd edition, New York, NY: CRC Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Langevin, M. , Packman, A. & Onslow, M. (2010) Parent perceptions of the impact of stuttering on their preschoolers and themselves. Journal of Communication Disorders, 43, 407–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levickis, P. , McKean, C. , Wiles, A. & Law, J. (2020) Expectations and experiences of parents taking part in parent–child interaction programmes to promote child language: a qualitative interview study. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 55(4), 603–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe R., O'brian S., Onslow M. (2013) Review of telehealth stuttering management. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 65, 223–238. 10.1159/000357708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmström, E. & Tidelius, H. (2018) Palin parent rating scales for children who stutter‐ translation and evaluation of reliability. In: Unpublished degree project in speech and language pathology, Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology, Division of Speech and Language Pathology, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, J. (2016) Behavioural, emotional and social development of children who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 50, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill, M. , Noureal, N. & Siegel, J. (2019) Telepractice treatment of stuttering: a systematic review. Telemedicine and e‐health, 25(5), 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard, S.K. & Davis, S. (2016) The Palin Parent Rating Scales: parents’ perspectives of childhood stuttering and its impact. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59, 950–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard, S.K. , Zebrowski, P. & Kelman, E. (2018) Palin parent‐child interaction therapy: the Bigger Picture. American Journal of Speech‐Language Pathology, 27, 1211–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brian, S. , Smith, K. & Onslow, M. (2014) Webcam delivery of the Lidcombe program for early stuttering: a phase I clinical trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57, 825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onslow M., Jones M., O'brian S., Packman A., Menzies R., Lowe R., Arnott S., Bridgman K., De Sonneville C., Franken M.‐C. (2018) Comparison of percentage of syllables stuttered with parent‐reported severity ratings as s primary outcome measure in clinical trials of early stuttering treatment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61, 811–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onslow, M. , Webber, M. , Harrison, E. , Arnott, S. , Bridgman, K. , Carey, B. , Sheedy, S. , O'Brian, S. , MacMillian, V. , Lloyd, W. & Hearne, A. (2021) The Lidcombe Program treatment guide (version 1.3). Retrieved from www.lidcombeprogram.org

- Packman, A. (2012) Theory and therapy in stuttering: a complex relationship. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 37, 225–233. 10.1016/j.jfludis.2012.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensfeldt Flink, A. , Åsberg Johnels, J. , Broberg, M. & Thunberg, G. (2020) Examining perceptions of a communication course for parents of children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 68, 156–167. 10.1080/20473869.2020.1721160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenker, R.C. & Santayana, G. (2018) What are the options for the treatment of stuttering in preschool children? Seminars in Speech and Language, 39, 313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith & Weber (2017) How stuttering develops: the multifactorial dynamic pathways theory. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60, 2483–2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugathan, N. & Maruthy, S. (2021) Predictive factors for persistence and recovery of stuttering in children: a systematic review. International Journal of Speech‐Language Pathology, 23 (4), 359–371. 10.1080/17549507.2020.1812718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanryckeghem, M. , Brutten, G.J. & Hernandez, L.M. (2005) A comparative investigation of the speech‐associated attitude of preschool and kindergarten children who do and do not stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorder, 30, 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yairi, E. & Ambrose, N. (2013) Epidemiology of stuttering: 21st century advances. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 38(2), 66–87. 10.1016/j.jfludis.2012.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalom, I.D. & Leczsc, M. (2005) The theory and practice of group psychotherapy, 5th edition, New York: The Random House. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.