Abstract

Introduction

We report a case of asymptomatic Thelazia callipaeda infection discovered incidentally during phacoemulsification cataract surgery in March 2024.

Case Presentation

A 77-year-old male patient presented with complaints of blurred vision. During a slit-lamp examination, trichiasis was observed, but the patient had no foreign body sensation or itching. He was diagnosed with cataract and underwent phacoemulsification cataract surgery. During the surgery, a white, wriggling worm was discovered in the conjunctival sac and removed. It was later identified as Thelazia callipaeda. The surgical eye was thoroughly washed and received anti-inflammatory medication postoperatively. No recurrence or new symptoms were reported during the 3-month follow-up period.

Conclusions

Thelazia callipaeda infection can be asymptomatic and incidentally discovered. A detailed preoperative examination, such as turning over the upper and lower eyelids to check the conjunctival sac, is necessary before the surgery. When a worm is discovered during surgery, it is crucial to remove it completely and thoroughly clean and disinfect the conjunctival sac.

Keywords: Thelazia callipaeda, Thelaziasis, Phacoemulsification, Ocular infection

Introduction

Thelaziasis is an ocular parasitic infection in wild and domestic animals, caused by nematodes from the genus Thelazia. Thelazia mainly includes two species: Thelazia californiensis discovered in North America and Thelazia callipaeda, which is primarily prevalent in Asia [1]. Known as the oriental eye worm due to its long-standing presence in Southeast Asia and India, the number of Thelazia infection cases has recently been increasing in Europe as well [2].

This nematode infects the conjunctival sacs and surrounding orbital tissues of various mammalian species, including humans. Canids are regarded as the main definitive hosts for Thelazia callipaeda, while drosophilid flies are considered the main vectors. These flies ingest embryonated eggs or primary‐stage (L1) larvae while feeding on the lacrimal secretions of definitive hosts. It takes about 2–4 weeks for the larvae to mature into infective third‐stage (L3) larvae within the body cavity of the flies. Third‐stage (L3) larvae and adult worms then parasitize the conjunctival sac of new hosts (Fig. 1) [2–4]. The mechanical damage inflicted by Thelazia on the conjunctival and corneal epithelium may lead to ocular discharge, which facilitates the feeding of flies on lachrymal secretions, thus transmitting the parasites [5].

Fig. 1.

Life cycle of Thelazia.

Symptoms of Thelazia infection mainly occur in the adult and larval stages and are characterized by tearing, epiphora, ocular discharge, conjunctivitis, keratitis, corneal opacity, or ulcers. Larvae could contribute to the pathogenesis of conjunctivitis because obvious symptoms were more often observed in animals infected with gravid females while asymptomatic infection mainly occurred in animals parasitized by male nematodes [6, 7]. Asymptomatic infections pose difficulties in the discovery and diagnosis of parasites. As a result, parasites may only be discovered during eye surgery.

In March 2024, we encountered a case of Thelazia callipaeda infection during phacoemulsification cataract surgery. The diagnosis and treatment details of this case are as follows.

Case Presentation

A 77-year-old male patient was admitted with a complaint of blurred vision in the right eye that had persisted for years. He had a history of phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation in the left eye. He reported no systemic disease or previous ocular symptoms.

The best corrected visual acuity was 20/166 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure, measured using noncontact tonometry, was 11 mmHg in both eyes. The slit-lamp examination revealed trichiasis in the right eye, while the lids and lid margins were normal. The conjunctival hyperemia was not evident, and there were no hemorrhagic spots. The cornea and anterior chamber were clear, the pupil was round and reacted briskly to light. The right lens had corticonuclear opacities. The left eye’s conjunctiva and cornea showed no abnormalities, and the intraocular lens was centrally positioned. The posterior segment of the eye, including the posterior lens capsule, vitreous, and fundus, appeared normal as verified by slit-lamp biomicroscopy lenses and B-scan ultrasonography. The lacrimal passage was irrigated to ensure the absence of chronic dacryocystitis and to prevent postoperative concurrent infections. Routine examinations, including a 12-lead electrocardiogram and blood tests, were also conducted to rule out systemic disorders.

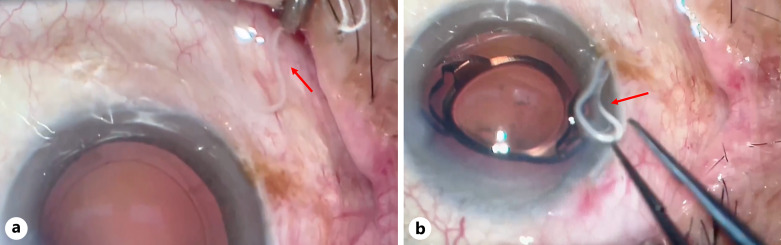

He was diagnosed with age-related cataract and trichiasis in the right eye. The trichiasis was promptly removed upon detection. Antibiotic eye drops were administered to both eyes three times a day for 2 weeks prior to the surgery. Phacoemulsification cataract surgery was performed under topical anesthesia with Alcaine (proparacaine hydrochloride 0.5%, Alcon) 2 weeks after the initial visit. During surgery, a nematode approximately 11 mm in length was noted in the surgical field (shown in Fig. 2a; online suppl. Video; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000541509). It protruded from the conjunctival sac of the lower eyelid, uncoiled, and exhibited a wriggling appearance. The surgeon completed the intraocular lens implant (Tecnis 1-Piece Acrylic IOL; ZCB; Johnson & Johnson Surgical Vision, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and removed the worm using microsurgery tweezers (shown in Fig. 2b; online suppl. Video). The conjunctival sac was thoroughly washed with sodium lactate Ringer’s solution and 0.5% povidone-iodine. After ensuring no remnants remained, the incision was sealed watertight, and the surgical eye was covered with tobramycin and dexamethasone eye ointment.

Fig. 2.

Video capture of the operation. a During the surgery, a slender, milky-white, semitranslucent linear organism (red arrow) was found in the conjunctival sac of the lower eyelid. b After implantation of intraocular lens, the surgeon removed the worm (red arrow) with microsurgery tweezers and rinsed the conjunctival sac thoroughly.

Post-surgery, we inquired about more details of the patient’s personal history. The patient, a farmer living in a village near a freshwater lake, reported no contact with animals such as dogs, cats, or foxes and no recollection of any prior instances of fly attacks on his eyes. There were no similar cases reported among his family or neighbors.

We organized the patient’s information and surgical video and consulted specialists from the Parasite Department of the Medical College of Soochow University. They identified the species as Thelazia callipaeda based on morphological characteristics.

As mechanical removal is the definitive treatment for human Thelazia callipaeda infection [8], the patient’s surgical eye was meticulously examined and washed to ensure no worm residues remained. The other eye was also examined and rinsed post-surgery. The patient received tobramycin dexamethasone eye drops, pranoprofen eye drops, and antibiotics eye drops four times a day for 1 month for anti-inflammatory and infection prevention. No vermifuge or special medical treatments were administered.

The patient was instructed to attend regular follow-up visits. During the 3-month follow-up, no abnormalities or recurrence were found. The patient’s visual acuity of the right eye remained at 20/25. Slit-lamp examination revealed healthy lids, white conjunctiva, a clear cornea, and a quiet anterior chamber. The intraocular lens was centrally positioned within the capsular bag. No residual Thelazia was found after thorough examination of the anterior and posterior segments using slit-lamp examination and B-scan ultrasonography, as Thelazia has also been reported in the vitreous cavity [9].

Discussion

Thelazia conjunctiva primarily parasitizes the orbital cavity and associated structures in both mammals and birds, including humans, rodents, monkeys, cattle, dogs, deer, pigs, foxes, cats, camels, and horses. Thelazia parasites feed on the tears and ocular secretions of their hosts and are commonly found in regions with poor hygiene and sanitation, particularly where humans cohabit with animals [5]. Infection is speculated to be associated with rural environments, inadequate personal hygiene, and low socioeconomic status [2, 10, 11].

In this case, the patient, a farmer from a rural area near a freshwater lake, denied any recent contact with animals such as dogs, cats, or foxes, or any eye contact with flies. It was hypothesized that the eye infection could be attributed to unhygienic practices, such as rubbing the eyes with hands contaminated by fruit flies carrying Thelazia callipaeda.

The patient had previously undergone left eye phacoemulsification in September 2023 by the same surgeon. In six follow-up visits after surgery, no traces of worms were found. Considering the 2-week interval between the patient’s last visit and the right eye surgery, it cannot be ruled out that parasitic ova or larvae develop into adult worms during the interval [2, 8].

Symptoms of Thelazia callipaeda infection are diverse and non-specific [7]. Before the operation, the patient only complained of blurred vision without any foreign body sensation, tearing, redness, or itching in the right eye, which may be relate to the patient’s adaptation to the sensation of trichiasis. Lower numbers of worms or a limited duration of infection may also contribute to this situation. The worm may have been hidden deep in the conjunctival sac and began to move after being stimulated by topical anesthetics and the eyelid opener during the operation. Additionally, trichiasis may have resulted in a less detailed examination of the conjunctival sac. This suggests the necessity of turning over the upper and lower eyelids to check the conjunctival sac during preoperative examination.

A limitation of this case is the absence of a pathological examination for the nematode, resulting in weaker diagnostic evidence. However, Thelazia is typically diagnosed by visualizing the parasite on the conjunctiva. Adult Thelazia worms are very active, slender, filiform, milky white, and semi-transparent. Under a microscope, they exhibit a rounded head and tail, distinct serrated transverse striations on the body surface, and a characteristic hexagonal, step-shaped mouth at the anterior end. Eggs or larvae can sometimes be observed in tears or other ocular secretions [8].

Another drawback was the delay in removing the worm immediately upon its discovery. The worm was detected after the removal of the lens cortex and was removed after the intraocular lens had been implanted. The worm was visible early in the surgery, but the surgeon did not notice it, as confirmed by reviewing the surgical video. Fortunately, the infection did not spread intraocularly through the anterior chamber, and there were no postoperative adverse reactions due to thorough cleaning and disinfecting of the conjunctival sac. We recommend that any worm discovered during a procedure should be promptly removed before continuing with the surgery.

According to our records, this case may be only the second report of Thelazia callipaeda discovered during phacoemulsification cataract surgery in China, with the first case reported in 2021 involving an 85-year-old male farmer [12]. In the first case, the patient experienced a foreign body sensation in the infected eye before undergoing surgery. However, in our case, the patient denied any discomfort and had no history of contact with animals or insects, making him a truly asymptomatic carrier. This posed a challenge in avoiding misdiagnosis based solely on medical history. The presence of trichiasis and the long interval between the last visit and the surgery day may have contributed to a less thorough preoperative examination. For asymptomatic individuals, it is imperative to conduct a meticulous, thorough, and standardized preoperative evaluation.

The case also indicates that if worms are found during surgery, it is essential to remove them entirely using smooth, non-sharp forceps or dull instruments without teeth, or even sponges, to avoid severing the worms. Spillage of worm contents onto the conjunctiva can cause toxic and secondary reactions. Additionally, lidocaine can aid in immobilizing and extracting the worm.

In conclusion, Thelazia callipaeda infection may be asymptomatic and unintentionally discovered. Maintaining good personal hygiene can reduce the likelihood of infection. A comprehensive examination, including a careful slit-lamp examination and turning over the upper and lower eyelids to check the conjunctival sac, is crucial, especially for patients with prolonged intervals between visits and surgeries, to minimize the risk of missed diagnoses. Thoroughly cleaning and disinfecting the conjunctival sac and entirely removing worms can contribute to a favorable prognosis for Thelazia callipaeda infection discovered during surgery. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material.

Acknowledgment

We would like to appreciate the Parasite Department of the Medical College of Soochow University to identify the worm.

Statement of Ethics

The case report was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (No. 447(2024)). The subject was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for all medical examinations, treatments, and also publication of this case report including any accompanying images. This report does not include any identifying patient information.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors state that there was no conflict of interest in documenting this study.

Funding Sources

This manuscript did not receive any funding.

Author Contributions

Xinzhu Chen collected the data and drafted the manuscript. Hanmu Guo collected the data, reviewed, and edited. Yanting Li performed follow-up after surgery, reviewed, and edited. Peirong Lu performed surgery and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This manuscript did not receive any funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Bradbury RS, Gustafson DT, Sapp SGH, Fox M, de Almeida M, Boyce M, et al. A second case of human conjunctival infestation with thelazia gulosa and a review of T. Gulosa in North America. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(3):518–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Otranto D, Mendoza-Roldan JA, Dantas-Torres F. Thelazia callipaeda. Trends Parasitol. 2021;37(3):263–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Otranto D, Traversa D. Thelazia eyeworm: an original endo- and ecto-parasitic nematode. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21(1):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang YJ, Liag TH, Lin SH, Chen HC, Lai SC. Human thelaziasis occurrence in Taiwan. Clin Exp Optom. 2006;89(1):40–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chowdhury R, Gogoi M, Sarma A, Sharma A. Ocular thelaziasis: a case report from Assam, India. Trop Parasitol. 2018;8(2):94–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smeal MG. Observations on the occurrence of Thelazia or eyeworm infection of cattle in Northern New South Wales. Aust Vet J. 1968;44(11):516–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Otranto D, Dutto M. Human thelaziasis, Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(4):647–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chanie M, Bogale B. Thelaziasis: biology, species affected and pathology (conjunctivitis) – a review. Acta Parasitologica Globalis. 2014;5(1):65–8. Available from: https://core.ac.uk/outputs/199937309/?utm_source=pdf&utm_medium=banner&utm_campaign=pdf-decoration-v1 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zakir R, Zhong-Xia Z, Chioddini P, Canning CR. Intraocular infestation with the worm, Thelazia callipaeda. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83(10):1194–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharma M, Das D, Bhattacharjee H, Islam S, Deori N, Bharali G, et al. Human ocular thelaziasis caused by gravid Thelazia callipaeda: a unique and rare case report. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(2):282–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rolbiecki L, Izdebska JN, Franke M, Iliszko L, Fryderyk S. The vector-borne zoonotic nematode thelazia callipaeda in the Eastern part of Europe, with a clinical case report in a dog in Poland. Pathogens. 2021;10(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li Y, Liu J, Tian Q, Guo D, Liu D, Ma X, et al. Thelazia callipaeda infection during phacoemulsification cataract surgery: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21(1):376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.