Abstract

Haemonchus contortus is a pathogenic nematode that infects small ruminants. Chemotherapy is the main treatment for these parasitic infections, but the rapid rise of drug resistance calls for the development of new anthelmintics. To support this, optimizing screening assays is vital for identifying new drugs. The exsheathed L3 (xL3) stage of H. contortus is often used in in vitro evaluations; however, it has been observed that it is less sensitive than the adult stage, possibly due to enhanced detoxification pathways. To explore this hypothesis, inhibitors of xenobiotic detoxification pathways were tested on the activity (IC50) of four anthelmintics—monepantel (MOP), levamisole (LEV), ivermectin (IVM), and albendazole sulfoxide (ABZ SO)—in xL3 using an automated motility assay. The inhibitors used were piperonyl butoxide (PBO) for phase I metabolism, 5-nitrouracil (5-NU) for phase II metabolism, and zosuquidar (ZOS) inhibiting efflux transport proteins. PBO increased MOP IC50, likely due to reduced formation of the active metabolite monepantel sulfone. IC50 of MOP with 5-NU and IVM with PBO were both diminished, suggesting differences in metabolism between xL3 and the existing reports for the adult stage. Coincubation of LEV and IVM with ZOS also reduced IC50, confirming previous studies. ABZ SO was unaffected by the inhibitors. The use of inhibitors of xenobiotic detoxification pathways led to significant changes in the in vitro activity of the anthelmintics evaluated in H. contortus xL3 stage. Further studies, as ex vivo parasite diffusion assays in the xL3 stage, should be conducted to directly assess the impact on detoxification pathways.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Haemonchus contortus, Automated motility assay, Xenobiotics, Detoxification pathways

Introduction

Helminthiases are infection diseases originated by parasitic worms that cause relevant morbidity and mortality worldwide and represent a problem in both human and animal health (Becker et al. 2018; Vercruysse et al. 2018), causing the main losses in annual global food production (Lane et al. 2015; Charlier et al. 2020; Rehman and Abidi 2022). Particularly, haemonchosis is one of the most pathogenic infestations caused by the blood-feeding parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus, affecting small ruminants and generating substantial economic losses (Adduci et al. 2022). The chemotherapy control of haemonchosis, as well as other diseases caused by gastrointestinal nematodes, has been preferred due to costs, effectiveness, and simplicity in its administration, but the extensive and inappropriate use of marketed anthelmintic drugs has given rise to resistance worldwide (Torres-Acosta et al. 2012; Preston et al. 2019; Rose Vineer et al. 2020). In this sense, the problem of anthelmintic resistance exposes the need to develop new anthelmintic drugs, which requires validated activity screening assays, that allow the identification of new compounds, as well as the generation of livestock management strategies to slow down the development of this phenomenon.

The development and application of in vitro methods involving living helminths to detect potential anthelmintic molecules, such as physiology-based assays, represent an area of considerable interest. In these tests, the parasites are cultured in vitro in the presence of the compound to be evaluated, and phenotypic parameters (such as viability, motility, and worm growth) are studied (Rohwer et al. 2012). Each validated assay has its own set of advantages and disadvantages. For instance, to evaluate compounds against H. contortus in anthelmintic activity assays, it is of great interest the use of the target adult stage, but it requires the necropsy of the sheep for the extraction of the parasites from the abomasum and their immediate culture (they cannot be preserved) (O’Grady and Kotze 2004). An interesting alternative to the use of the adult stage is the use of exsheathed L3 (xL3s), the first parasitic stage of this nematode (Preston et al. 2015). This approach presents several advantages: the possibility of preserving L3 stage parasitic material, which can be stored for up to 3 months at 10 °C without affecting phenotypes; the relatively simple L3s exsheathment procedure to obtain xL3; and the fact that xL3s are more susceptible than L3s to the commercialized anthelmintics tested (more than 100 times) (Preston et al. 2015). However, a problem with the use of larval stages in the screening of new molecules is the high proportion of false negative results compared to the study of anthelmintic activity in the adult stage (Munguía et al. 2022). This may be attributed, among other reasons, to a greater activity of the detoxification mechanisms in the larval stages compared to the adult stage (Barrett 2009; Geary 2016). The study of xenobiotic’s detoxification mechanisms in helminths, both metabolism and transport protein-mediated efflux by members of the ABC family, has focused mainly on explaining the development of resistance to anthelmintics, comparing these detoxification mechanisms between strains of H. contortus with different susceptibility to these drugs (Bartley et al. 2009; Vokřál et al. 2012, 2013b; Sarai et al. 2013, 2014; AlGusbi et al. 2014; Raza et al. 2015, 2016b, 2016c; Stuchlíková et al. 2018; Kellerová et al. 2019, 2020; Tuersong et al. 2023). However, few reports study the detoxification mechanisms between different stages of the same strain of H. contortus (Kotze et al. 2006; Laing et al. 2015; Ma et al. 2018; Dimunová et al. 2022; Giglioti et al. 2022). Gaining insight into these differences may help to optimize future screening assays with different stages of H. contortus. Furthermore, understanding how new molecules with anthelmintic activity interact with the various xenobiotic detoxification mechanisms in parasites and determining their parasite bioavailability could provide information on possible mechanisms of resistance or cross-resistance with other anthelmintics.

This work aims to understand the differences observed in our previous work in the sensitivity to commercial anthelmintics between the xL3 larval stage and the adult stage of H. contortus (Munguía et al. 2022). For this purpose and considering the assumption that the presence of xenobiotic detoxification mechanisms is increased in the larval stages of this nematode, we study the influence of inhibitors of the xenobiotic-metabolizing cytochrome P450 family enzymes (CYP), the uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, UGT) enzymes and the efflux transporters proteins (Pgp) on the activity of anthelmintic drugs in the xL3 stage using an automated motility assay.

Methods

Chemicals

Ivermectin (IVM, PHR1380), levamisole (LEV, PHR1798), and albendazole (ABZ, PHR1281) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, USA, as pharmaceutical secondary standard grade (certified reference material); albendazole sulfoxide (ABZ SO, SC-205838) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA, as analytical standard grade (purity ≥ 98%); zosuquidar hydrochloride (ZOS, SML1044), piperonyl butoxide (PBO, 45,626), and 5-nitrouracil (5-NU, 852,767) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, USA, as analytical standard grade (purity ≥ 98%). Monepantel (MOP, Zolvix™, Novartis, Switzerland) was purchased from local suppliers and diluted 1/378 times in dimethyl sulfoxide for its use in assays (concentration 200 ×). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used to solubilize the anthelmintics and inhibitors and was purchased from Carlo Erba, France, with analytical purpose quality. The anthelmintics were selected with the aim of including the chemical families of the commercialized treatments for this parasite. During the development and validation of the automated motility assay for the xL3 stage, both benzimidazoles ABZ and fenbendazole were tested, but due to their low solubility, the maximum concentration without product precipitation was 20 µM. To include the benzimidazole family in the assay validation, the ABZ SO (ABZ active metabolite marketed as ricobendazole) was performed. On the other hand, the inhibitors 5-NU, PBO, and ZOS were selected based on previous reports in the literature where their influence on the activity of anthelmintic drugs on H. contortus was evaluated (Kotze et al. 2006, 2014; Raza et al. 2015).

Haemonchus contortus production and maintenance

Artificial infestations of H. contortus from the anthelmintic-susceptible McMaster isolate (Kirby) in sheep were maintained at a private farm called “Se puede,” at Empalme Olmos, Uruguay, as we have previously described (Munguía et al. 2022). The animal protocol complied with Uruguayan Law No. 18.611. Experimental protocol was reviewed and approved for this study by IACUC of Facultad de Química – Udelar, Uruguay (file N° 101,900–500053-21).

Third-stage larvae (L3s) were obtained from H. contortus eggs by incubation of humidified feces from infested sheep at 27 °C for 1 week according to (Mes et al. 2007). Once collected, L3s were maintained in distilled water at 5–9 °C for up to 90 days.

L3s were exsheathed according to Preston et al. (2015). The exsheathed L3s (xL3s) were washed once with Luria Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 100 IU/ml of penicillin, 100 µg/ml of streptomycin, and 2.5 µg/ml of amphotericin and resuspended in this supplemented LB, designated as LB*.

In vitro anthelmintic assays

A whole-organism automated motility assay was utilized to evaluate the effects of inhibitors of the xenobiotic metabolizing CYP and UGT enzymes, as well as efflux transporters proteins, on the activity of anthelmintic drugs on the motility of xL3s of H. contortus, as described in our previous work (Munguía et al. 2022). Briefly, the xL3 suspension in LB* was transferred to sterile 96-well flat bottom microplates (CellStar, Greiner) (300 xL3s in 50 μl of LB supplemented per well). Then, 50 μl of the compound’s solutions (prepared in LB* and 1% v/v DMSO at a 2 × concentration) were added to each well to obtain a final 1 × concentration of anthelmintic and/or inhibitor and 0.5% v/v DMSO (six replicates each) (see Table 1 for the drug concentration ranges assayed).

Table 1.

Range of concentrations of commercial anthelmintics monepantel (MOP), levamisole (LEV), albendazole sulfoxide (ABZ SO), and ivermectin (IVM) and the inhibitors piperonyl butoxide (PBO), 5-nitrouracil (5-NU), and zosuquidar (ZOS) assayed per well in the different in vitro assays

| xL3s motility assay (µM) | xL3s to L4 development assay (µM) | |

|---|---|---|

| MOP | 0.02–0.7 | – |

| LEV | 0.80–50 | – |

| IVM | 0.02–2.8 | – |

| ABZ SO | 0.03–200 | – |

| PBO* | 3.91–250 | 3.91–250 |

| 5-NU* | 160–10,000 | 160–10,000 |

| ZOS* | 0.39–25 | 0.39–25 |

*The effect of the inhibitors on the motility and development of xL3 was evaluated to determine the concentrations at which they were not toxic to the larvae. Then, the inhibitors were coincubated with the different anthelmintics in the xL3 motility assay

Culture medium control (LB* medium), negative control (vehicle, 50 μl of 1% v/v DMSO LB*, giving a final concentration of 0.5% v/v DMSO in LB* in the well) and positive control (50 μl of ABZ 40 μM in 1% v/v DMSO LB*, giving a final concentration of ABZ 20 μM and 0.5% v/v DMSO in LB* in the well) were also tested in each plate. The plates were incubated at 40 °C in a humidified incubator with a 10% CO2 atmosphere for 72 h.

xL3 automated motility assay

The motility assessment of the xL3 stage was performed using an automated tracking apparatus: WMicrotracker One (Phylumtech, Argentina) (Liu et al. 2019; Risi et al. 2019; Munguía et al. 2022). The worm motility measurements of each well were carried out at 24, 48, and 72 h for 30 min at 20–22 °C. The raw motility data was normalized against the motility measurements obtained for the DMSO control group to remove plate-to-plate variation by calculating the percentage of motility of each treatment as follows:

| 1 |

An ordinary one-way ANOVA test was conducted on each assay utilizing raw motility data once the normal distribution had been confirmed, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test against the DMSO control group, with 95% confidence using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.2, 2021, for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A probability of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was restricted and recommended for its use comparing several experimental groups against a single control group, as the DMSO control.

The data from the concentration–response curves of the different commercial anthelmintics in the presence or absence of inhibitors were transformed to log10 to determine the anthelmintics concentrations that leads to 50% of maximal response (IC50) from at least three independent and averageable trials (two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Šídák test, P < 0.05, GraphPad Prism version 9.0.2, 2021). The data was adjusted using a variable slope and a four-parameter logarithmic equation (Eq. 2), where A1 is the bottom asymptote, A2 is the top asymptote, log × 0 is the center of the curve and represents the log IC50, and P is the Hill variable slope of the logarithmic dose–response curve.

| 2 |

The IC50 (Eq. 3) was determined using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.2, 2021, for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

| 3 |

A comparison of the IC50 values of each anthelmintic in the presence and absence of each inhibitor was conducted using an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, with 95% confidence interval, P < 0.05, GraphPad Prism version 9.0.2, 2021.

xL3 to L4 development assay

For the xL3 to L4 development assay, we proceeded according to bibliography (Preston et al. 2015) with minor modifications as described in our previous work (Munguía et al. 2022). In brief, the plates tested for xL3 motility were re-incubated for four more days at 40 °C and 10% v/v CO2, completing a total of seven days of incubation. Then, worms were fixed with 50 μl of a 1% iodine solution, and 20 μl of each well was examined at 10 × magnification (Nikon TS100, inverted microscope, Tokyo, Japan) to assess their development, based on the presence or absence of a well-developed pharynx characteristic of H. contortus L4s.

The number of L4s was expressed as a percentage of the total worm number present in the 20 μl larval suspension examined under the microscope. Each concentration of inhibitor compound (PBO, 5-NU, or ZOS) was tested by triplicate, at least in three different trials, to determine the maximum concentration of inhibitor to be used in coincubations with anthelminthics in the xL3 motility assay, without affecting the development of xL3 by its own. An ordinary one-way ANOVA test was conducted on each assay once the normal distribution of data was confirmed and was followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test against the DMSO control group, with 95% confidence, using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.2, 2021, for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A probability of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Determination of the concentration of inhibitors to be tested in coincubation with anthelmintics

First, an evaluation of PBO, 5-NU, and ZOS at different concentrations was carried out in the xL3 stage of H. contortus to determine the concentrations of inhibitors that did not affect the motility of the xL3 nor its development to L4 (see Table 1). Of the 5-NU concentrations tested, none decreased the motility of xL3 or its development to L4, compared to the DMSO control (one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test, P < 0.05). In the case of incubations with PBO, the motility values obtained were significantly higher than the DMSO control for the 250 and 125 µM concentrations. Furthermore, PBO at 250, 125, 62.5, and 31.25 µM significantly affected the development of xL3 to the L4 stage (one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test, P < 0.05). The incubation of the xL3 with ZOS, the Pgp inhibitor, increased the motility significantly at 25, 12.5, and 6.25 µM compared to the DMSO control, and no significant impairment was observed in the development to the L4 stage (one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test, P < 0.05). Given these results, the selected concentrations of inhibitors for coincubations with anthelmintic drugs were as follows: 5000 µM 5-NU, 15.6 µM PBO, and 3.13 µM ZOS.

Coincubation of anthelmintics and inhibitors

The anthelmintics Monepantel (MOP), Albendazole sulfoxide (ABZ SO), Levamisole (LEV), and Ivermectin (IVM) were tested in the xL3 motility assay in the presence and absence of each inhibitor under study. The anthelmintic concentration ranges studied are shown in Table 1. At least three replicates of each condition were carried out and evaluated to ensure that they could be averaged with each other (two-way ANOVA with posterior Holm-Šidák test, P < 0.05), the averaged data were fitted to dose–response curves from which the IC50 and A2 (top asymptote) values at 24 and 72 h were obtained, according to Eq. 2 and Eq. 3 (see Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) ± standard error (SE) of commercial anthelmintics monepantel (MOP), levamisole (LEV), albendazole sulfoxide (ABZ SO), and ivermectin (IVM) alone or in combination with the inhibitors piperonyl butoxide (PBO), 5-nitrouracil (5-NU), and zosuquidar (ZOS) at 24 h and 72 h post-incubation

| Control | n | + PBO 15.6 µM | n | + 5NU 5 mM | n | + ZOS 3.13 µM | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 ± SE (µM) (24 h) | ||||||||

| MOP | 0.242 ± 0.077a | 8 | 0.229 ± 0.023 | 3 | 0.109 ± 0.065a | 4 | 0.231 ± 0.028 | 3 |

| LEV | 5.239 ± 1.023b | 9 | 4.418 ± 0.654 | 3 | 8.333 ± 2.677 | 4 | 3.728 ± 0.489b | 3 |

| IVM | 0.200 ± 0.040c | 7 | 0.105 ± 0.024c | 3 | 0.121 ± 0.047 | 3 | 0.102 ± 0.052 | 3 |

| ABZ SO | 1.509 ± 0.836 | 7 | 1.097 ± 1.115x | 3 | 20.846 ± 88,183.756x | 3 | 1.478 ± 0.727 | 3 |

| IC50 ± SE (µM) (72 h) | ||||||||

| MOP | 0.091 ± 0.019d,e,f | 8 | 0.122 ± 0.010d | 3 | 0.049 ± 0.012 e | 4 | 0.126 ± 0.015 f | 3 |

| LEV | 8.745 ± 2.920g,h | 9 | 7.998 ± 1.079 | 3 | 13.141 ± 1.452g | 4 | 6.144 ± 0.711h | 3 |

| IVM | 0.369 ± 0.052 i | 7 | 0.307 ± 0.059 | 3 | 0.369 ± 0.059 | 3 | 0.257 ± 0.036 i | 3 |

| ABZ SO | 4.652 ± 1.037 | 7 | 3.606 ± 1.205 | 3 | 3.061 ± 1.373 | 3 | 4.653 ± 2.009 | 3 |

n, number of assays averaged to determine the IC50

Cells with the same letter represent a significant difference between the IC50 values for the anthelmintic coincubated with the inhibitor compared to the anthelmintic alone (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, P < 0.05)

X represents an error in the curve adjustment (greater error than IC50 value)

The positive control, albendazole 20 µM, is included in each assay. The percentage motility and SEM, using the DMSO control as the 100% reference point, are 75 ± 25 for 24 h and 23 ± 12 for 72 h

Table 3.

Upper asymptote (A2) ± standard error (SE) of commercial anthelmintics monepantel (MOP), levamisole (LEV), albendazole sulfoxide (ABZ SO), and ivermectin (IVM) alone or in combination with the inhibitors piperonyl butoxide (PBO), 5-nitrouracil (5-NU), and zosuquidar (ZOS) at 24 h and 72 h post-incubation

| Control | n | + PBO 15.6 µM | n | + 5NU 5 mM | n | + ZOS 3.13 µM | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 ± SE (µM) (24 h) | ||||||||

| MOP | 132.252 ± 9.496a,b | 8 | 113.690 ± 4.675a | 3 | 148.212 ± 58.086 | 4 | 116.600 ± 5.107b | 3 |

| LEV | 112.867 ± 14.202c | 9 | 103.937 ± 8.328 | 3 | 81.764 ± 15.267c | 4 | 113.429 ± 9.301 | 3 |

| IVM | 87.363 ± 10.195 | 7 | 96.022 ± 16.601 | 3 | 75.214 ± 19.015 | 3 | 50.919 ± 23.066 | 3 |

| ABZ SO | 117.558 ± 6.165d | 7 | 119.798 ± 9.794 | 3 | 138.904 ± 13.797 | 3 | 103.398 ± 5.402d | 3 |

| A2 ± SE (µM) (72 h) | ||||||||

| MOP | 115.838 ± 12.855 | 8 | 108.232 ± 5.035 | 3 | 110.209 ± 17.786 | 4 | 113.154 ± 7.920 | 3 |

| LEV | 110.928 ± 25.277 | 9 | 108.140 ± 8.710 | 3 | 93.867 ± 5.552 | 4 | 109.229 ± 6.481 | 3 |

| IVM | 99.701 ± 6.882e,f,g | 7 | 78.874 ± 6.761e | 3 | 81.240 ± 6.520f | 3 | 56.530 ± 4.175g | 3 |

| ABZ SO | 109.440 ± 6.185 | 7 | 125.058 ± 10.773 | 3 | 104.291 ± 7.733 | 3 | 111.075 ± 7.261 | 3 |

n, number of assays averaged to determine the fitting curve

Cells with the same letter represent a significant difference between the A2 values for the anthelmintic coincubated with the inhibitor compared to the anthelmintic alone (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, P < 0.05)

The positive control, albendazole 20 µM, is included in each assay. The percentage motility and SEM, using the DMSO control as the 100% reference point, are 75 ± 25 for 24 h and 23 ± 12 for 72 h

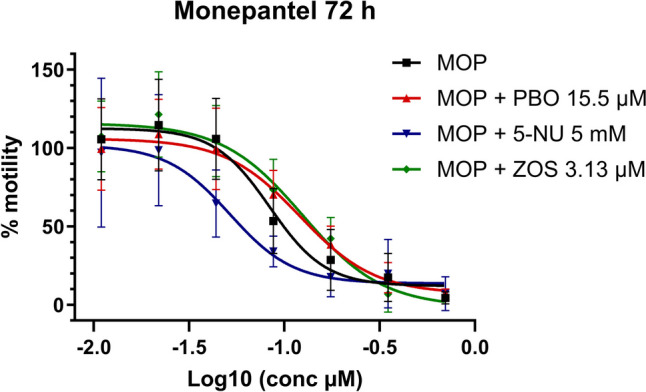

As can be seen in Fig. 1 and Table 2, the CYP enzymes inhibitor, PBO, and the efflux transporters inhibitor, ZOS, caused a significant increase in the IC50 value of MOP after 72 h of incubation (t(7.497) = 3.468, P = 0.0094 and t(4.340) = 3.179, P = 0.0299 respectively), resulting in a decrease in the activity of this drug. In Table 3, it is observed that a significant decrease in the A2 values of MOP coincubated with PBO or ZOS after 24 h of incubation (t(7.705) = 4.309, P = 0.0028 and t(7.126) = 3.503, P = 0.0097 respectively), suggesting that motility is diminished at lower doses of MOP when it is coincubated with these inhibitors. On the other hand, a significant decrease in the IC50 value of MOP was observed, both at 24 (t(7.149) = 3.142, P = 0.0159) and 72 h (t(9.138) = 4.735, P = 0.0010) of incubation, in the presence of the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzyme inhibitor 5-NU, resulting in enhanced drug activity.

Fig. 1.

Monepantel (MOP) dose–response curve in xL3s automated motility assay, at 72 h, alone or in combination with piperonyl butoxide (PBO), 5-nitrouracil (5-NU), or zosuquidar (ZOS). Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of at least three different experiments, with six replicates for each concentration

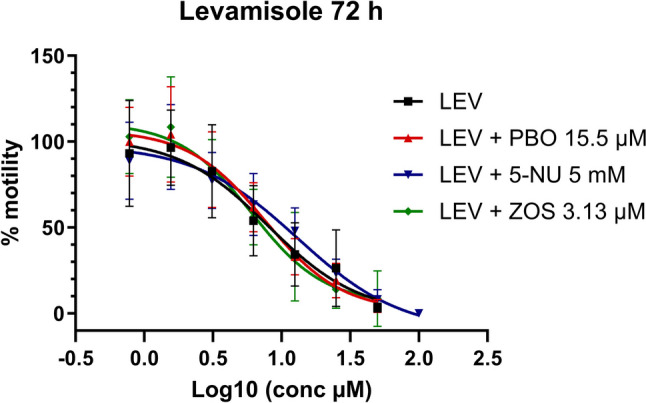

In the experiments with LEV, ZOS caused a significant decrease in its IC50 values, (Table 2 and Fig. 2), both at 24 (t(7.888) = 3.414, P = 0.0094) and 72 h (t(9.852) = 2.462, P = 0.0339) of incubation. Furthermore, the coincubation with 5-NU produced a significant increase in the IC50 value of LEV after 72 h of incubation (t(10.62) = 3.621, P = 0.0043) and a significant decrease in A2 value at 24 h of incubation (t(5.449) = 3.463, P = 0.0157), while PBO did not affect LEV activity, at 24 or 72 h of incubation.

Fig. 2.

Levamisole (LEV) dose–response curve in xL3s automated motility assay, at 72 h, alone or in combination with piperonyl butoxide (PBO), 5-nitrouracil (5-NU), or zosuquidar (ZOS). Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of at least three different experiments, with six replicates for each concentration

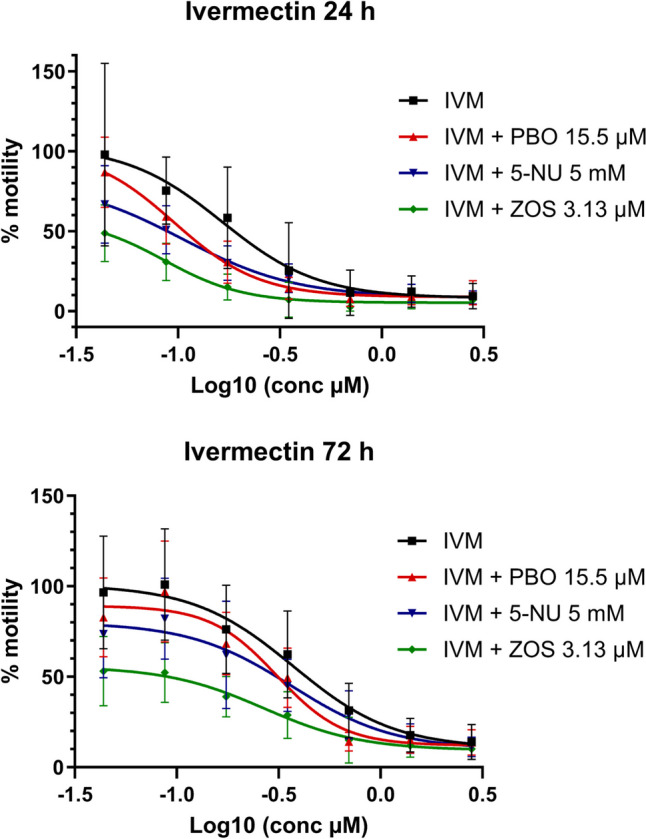

The results of the incubation of IVM with ZOS showed a significant decrease in the IC50 value for the anthelmintic drug, at 72 h (t(5.596) = 3.876, P = 0.0094), as well as incubation with PBO at 24 h (t(6.365) = 4.626, P = 0.0031) (Table 2 and Fig. 3), resulting in increased anthelmintic activity in both cases. On the other hand, the presence of 5-NU did not affect significantly IVM IC50 at 24 or 72 h of incubation.

Fig. 3.

Ivermectin (IVM) dose–response curve in xL3s automated motility assay, at 24 and 72 h, alone or in combination with piperonyl butoxide (PBO), 5-nitrouracil (5-NU), or zosuquidar (ZOS). Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of at least three different experiments, with six replicates for each concentration

Due to the differences observed in the upper asymptotes of the ivermectin dose–response curves, in the presence or absence of inhibitors, it was studied whether the value of the upper asymptote (the minimum effect achieved expressed as % of motility, A2, see Eq. 2.) varies significantly in the presence of inhibitors (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, P < 0.05). It was observed that after 72 h of incubation, the A2 value in the IVM dose–response curves was significantly lower for all coincubation experiments with inhibitors (t(3.913) = 4.440, P = 0.0119 for PBO; t(4.057) = 4.035, P = 0.0152 for 5-NU; and t(6.453) = 12.17, P < 0.0001 for ZOS), showing a greater anthelmintic effect even at the lowest concentrations of IVM tested. It is noteworthy that for coincubation with ZOS, an inhibitor of efflux transporter proteins, the maximum motility achieved at 72 h does not exceed 60% (Table 3).

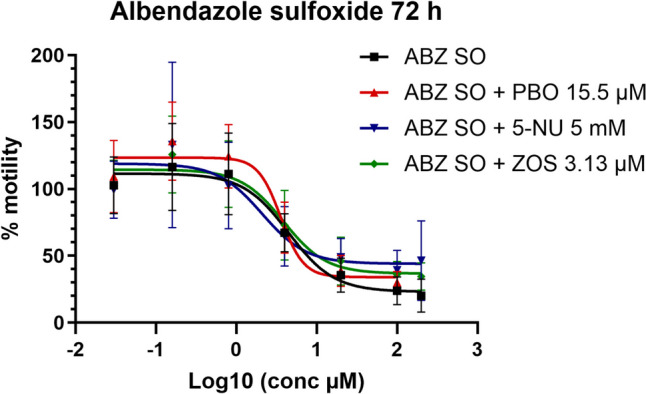

As presented in Table 2 and Fig. 4, none of the inhibitors coincubated with ABZ SO affected the value of its IC50 at 24 or 72 h of incubation, and as presented in Table 3, only ABZ SO with ZOS A2 value at 24 h was significantly decreased, an observation that was not sustained at 72 h.

Fig. 4.

Albendazole sulfoxide (ABZ SO) dose–response curve in xL3s automated motility assay, at 72 h, alone or in combination with piperonyl butoxide (PBO), 5-nitrouracil (5-NU), or zosuquidar (ZOS). Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of at least three different experiments, with six replicates for each concentration

Discussions

Haemonchus contortus is characterized by having a high biotic potential which results in significant genetic diversity. This, in turn, confers a remarkable capacity to generate new mutations, which in the face of positive selection, such as in conditions of misuse of anthelmintics, can be perpetrated and increase in frequency, leading to a rapid propensity to develop resistance to anthelmintic drugs (Gilleard 2013). Therefore, it is of interest to work on the discovery of new anthelmintic drugs, as well as to develop validated in vitro activity assays for their evaluation. In this sense, the in vitro automated motility assay in the xL3 H. contortus stage developed by our group (Munguía et al. 2022), presented the limitation of having lower sensitivity to the commercial anthelmintics tried, since lower concentrations were necessary to affect adult motility. In order to understand these differences and taking as a hypothesis that xenobiotic detoxification mechanisms are increased in larval stage (Barrett 2009; Geary 2016), the influence of inhibitors of some of the detoxification pathways on the activity of anthelmintic drugs was evaluated in the xL3 automated motility assay.

Firstly, the presence of all three inhibitors significantly affected the IC50 value at 72 h for MOP. In the case of coincubation with PBO, the IC50 value of MOP increased significantly (Table 2). MOP is transformed to its metabolites monepantel sulfoxide (MOP SO) and monepantel sulfone (MOP SO2) by CYP enzymes as well as flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO) protein family (Stuchlíková et al. 2014; Matoušková et al. 2016). MOP and its active metabolite, MOP SO2, are agonists of MPTL-1 betaine-gated ion channel (Baur et al. 2015), and potentiate the choline-activated currents mediated by DEG-3/DES-2 receptors in a concentration-dependent way without opening the channels by itself, acting as positive allosteric modulators (Rufener et al. 2010). Regarding this last pharmacological target, it has been proved that MOP SO2 can enhance the currents of the DEG-3/DES-2 choline-gated ion channel five times more than MOP (Rufener et al. 2010). The important role of MOP SO2 in the net anthelmintic activity of MOP may explain that a decrease in its intraparasitic concentration, due to the action of PBO inhibitor, can lead to an increase in the IC50 obtained for MOP on xL3 motility, resulting in a decrease in their anthelmintic activity. Another interesting observation was that the presence of 5-NU significantly decreased the IC50 value of MOP, increasing its activity and diminishing the motility of xL3 at 24 and 72 h of incubation. This represents an important difference in comparison with the adult stage of H. contortus since it is reported that MOP does not undergo phase II metabolism in that stage (Stuchlíková et al. 2014). In the xL3 stage, enzymes such as UDP-glucuronyltransferase could metabolize MOP, or its active metabolite MOP SO2, and reduce its intraparasitic concentration; therefore, the action of 5-NU may enhance the concentration of both molecules and explain the significant decrease in the IC50 value. Regarding the coincubation of MOP with ZOS, a significant increase in the IC50 was observed. A comparable outcome was obtained in Raza’s thesis (Raza 2016), in which the same coincubation increased the IC50 value of MOP in the larval development assay (LDA) against H. contortus. This phenomenon may be attributed to pharmacokinetic interaction. In one scenario, MOP could be retained in the intracellular medium where it is more available for metabolism, increasing the probability that inactive metabolites could be formed (Raza 2016); another explanation is a decrease in the formation of the MOP SO2 metabolite due to competition with ZOS for the CYP enzymes (Nielsen et al. 2021), an alternative independent of MOP being a Pgp substrate. Given that MOP is affected by all three detoxification pathways and could therefore be a substrate of several of these enzymes, it is plausible that the helminth could increase some protein expression, like ABC transporters reported for H. contortus (Raza et al. 2016a) or CYPs as reported for mammals (Stuchlíková et al. 2015), and rapidly develop pharmacokinetic mechanisms of resistance.

In the experiments with LEV, the coincubation with efflux transporter inhibitor ZOS decreased significantly its IC50 at 24 and 72 h of incubation, enhancing its effect on xL3 motility. These results align with those reported by Raza et al. (2015), where the influence of different efflux protein inhibitors on LEV and IVM activity in larval development (LDA) and larval migration (LMA) assays were studied. Their work demonstrates that ZOS is capable of increasing LEV activity in the LDA assay, for both the Kirby susceptible strain and the resistant Wallangra strain. Additionally, working with the xL3 stage of Kirby strain, we were able to see that ZOS could increase LEV activity even at 24 h of incubation in the motility assay.

The enhancing effect of ZOS on the anthelmintic IVM was also observed. In this case, a significant decrease in the IC50 value for IVM was observed at 72 h of incubation. It is known that IVM is a substrate of different efflux transporters and that its overexpression is a contributing factor to the development of resistance in nematodes (Lespine et al. 2007).

The coincubation of IVM with CYP inhibitor PBO resulted in increased anthelmintic activity of IVM at 24 h of incubation. This result obtained for the xL3 stage contrasts with the metabolism pattern that has been reported for IVM in the adult stage, where the absence of phase I or phase II metabolites for the drug has been described (Vokřál et al. 2013a) but correlates with results obtained for the same coincubation in larval stages of Cooperia oncophora and Ostertagia ostertagi (AlGusbi et al. 2014). The expression of genes that code for CYP enzymes has been studied, observing that CYP expression was generally highest in one or more larval stages with only a small subset of CYPs showing higher adult expression (Laing et al. 2015). Since during the free-living larval stages, the parasites are exposed to a wider range of environmental toxins, these stages may require greater CYP activity to detoxify exogenous compounds in comparison to the adult stage (Laing et al. 2015). Although in the present work, we used a parasitizing stage of H. contortus, xL3, differences were observed in the detoxification mechanisms compared to the adult stage, as it occurs with free-living larval stages.

Another parameter studied in the dose–effect curves was the upper asymptote, A2, which is shown in Table 3. For IVM, the three inhibitors significantly reduce the A2 value at 72 h. This could be related to the bioavailability of the anthelmintic, increasing its uptake (by inhibition of the Pgp) or decreasing its metabolism (either phase I or phase II). Furthermore, it was observed that coincubation with ZOS presents the most notable influence on the value of A2, reducing it to almost half, which explains a substantial influence of Pgp proteins in the intraparasitary diffusion of IVM.

Finally, within the group of benzimidazole anthelmintics, the influence of the inhibitors on the activity of ABZ SO, a metabolite of ABZ, was studied. As mentioned in the “Methods” section, it was not possible to obtain dose–response curves for ABZ in the xL3 motility assay due to solubility issues. The maximum concentration that could be tested without precipitation was 20 µM, which prevents the determination of the lower asymptote of the activity curve at higher concentrations. The metabolite ABZ SO exhibits anthelmintic activity, reaching an area under the curve (AUC) four times higher than ABZ after an intraruminal dose of 7.5 mg/kg of ABZ; therefore, this metabolite plays a substantial role in the efficacy of ABZ (Alvarez et al. 1999). The coincubation experiments of ABZ SO with the metabolism inhibitors tested did not show significant differences in comparison to the activity obtained for the anthelmintic alone, even though it is well known that ABZ SO suffers phase I and phase II metabolism in the adult stage of H. contortus (Stuchlíková et al. 2018; Dimunová et al. 2022). In previous works, it was proved that the activity of metabolizing enzymes in adults was higher in a resistant strain (IRE) than in a susceptible one (ISE) (Vokřál et al. 2013b), and the metabolites formed were also greater in the IRE strain (Stuchlíková et al. 2018). For juvenile stages, the differences observed between strains were consistent, and there were also found metabolites from both pathways (Kellerová et al. 2020). In our work, since Kirby is also a susceptible strain, it may have less metabolic capacity for ABZ SO, and particularly for this anthelmintic, the inhibition of the possible metabolic pathways would not be as relevant to result in significant differences.

The results obtained using inhibitors of xenobiotic detoxification pathways led to significant changes in the in vitro activity of the anthelmintics evaluated in the H. contortus xL3 stage. This could suggest that the differences in sensitivity to commercial anthelmintics observed between the xL3 larval stage and the adult stage of H. contortus may be due to enhanced detoxification mechanisms in larvae compared to adults. To confirm this hypothesis, further studies should directly assess the impact of these inhibitors on the intraparasitic concentrations of anthelmintics and their relevant metabolites. This could be achieved through ex vivo diffusion studies of anthelmintics in the presence and absence of the inhibitors PBO, 5-NU, and ZOS.

Conclusions

The conducted intervention in the xenobiotic detoxification pathways in Haemonchus contortus exsheathed L3 stage leads to results that note significant changes in the in vitro activity of the anthelmintics evaluated. These observations allow us to suggest that there could exist differences in the metabolism of xenobiotics between the xL3 stage compared to reports for the adult stage and, at some point, could explain the lower sensitivity to commercial anthelmintics detected for the xL3 motility assay in comparison to adult stage motility assay. These results also opened the possibility to add this kind of intervention in the in vitro assays in a way to understand the parasitic pharmacokinetics of new molecules. To complement the observations obtained, it remains to perform ex vivo parasite diffusion assays in the xL3 stage to determine concentrations of the anthelmintics and metabolites of interest and identify other metabolites that could be present in this stage, in the presence and absence of the inhibitors evaluated, and correlate the results with the activity data presented in this work.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Juan Salles and technicians Mario Salles, Karina Ducce and Nicolás Salles from the private farm called “Se puede”, at Empalme Olmos, Uruguay, for their technical assistance with the artificial infection of sheep and the care of animals.

Abbreviations

- xL3

Exsheathed larval L3 stage of Haemonchus contortus

- MOP

Monepantel

- MOP SO2

Monepantel sulfone

- LEV

Levamisole

- IVM

Ivermectin

- ABZ SO

Albendazole sulfoxide

- PBO

Piperonyl butoxide

- 5-NU

5-Nitrouracil

- ZOS

Zosuquidar

- IC50

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- CYP

Cytochrome P450 family enzymes

- UGT

Uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase

- Pgp

Efflux transporters proteins

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

Author contribution

MN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Research, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing- Review and Editing. GD: Research, Proofreading and Editing JS: Research, Proofreading and Editing MEM: Research, Formal analysis, Resources, Proofreading and Editing BM: Conceptualization, Validation, Resources, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Programa de Desarrollo de Ciencias Básicas (PEDECIBA, Uruguay) and CSIC – Udelar research project 366 (Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica de la Universidad de la República, Uruguay). MN acknowledges CSIC – Udelar for the postgraduate scholarship.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Artificial infection in sheep with third stage larvae (L3) of H. contortus from the anthelmintic-susceptible McMaster isolate (Kirby) was maintained at a private farm called “Se puede,” at Empalme Olmos, Uruguay, as we have previously described (Munguía et al. 2022). The animal protocol complied with Uruguayan Law No. 18.611. Experimental protocol was reviewed and approved for this study by IACUC of Facultad de Química – Udelar, Uruguay (file N° 101900–500053-21).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adduci I, Sajovitz F, Hinney B et al (2022) Haemonchosis in sheep and goats, control strategies and development of vaccines against Haemonchus contortus. Animals 12:2339. 10.3390/ani12182339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlGusbi S, Krücken J, Ramünke S et al (2014) Analysis of putative inhibitors of anthelmintic resistance mechanisms in cattle gastrointestinal nematodes. Int J Parasitol 44:647–658. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez LI, Sánchez SF, Lanusse CE (1999) In vivo and ex vivo uptake of albendazole and its sulphoxide metabolite by cestode parasites: relationship with their kinetic behaviour in sheep. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 22:77–86. 10.1046/j.1365-2885.1999.00194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J (2009) Forty years of helminth biochemistry. Parasitology 136:1633–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley DJ, McAllister H, Bartley Y et al (2009) P-glycoprotein interfering agents potentiate ivermectin susceptibility in ivermectin sensitive and resistant isolates of Teladorsagia circumcincta and Haemonchus contortus. Parasitology 136:1081–1088. 10.1017/S0031182009990345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baur R, Beech R, Sigel E, Rufener L (2015) Monepantel irreversibly binds to and opens Haemonchus contortus MPTL-1 and Caenorhabditis elegans ACR-20 receptors. Mol Pharmacol 87:96–102. 10.1124/mol.114.095653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SL, Liwanag HJ, Snyder JS et al (2018) Toward the 2020 goal of soil-transmitted helminthiasis control and elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12:e0006606. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier J, Rinaldi L, Musella V et al (2020) Initial assessment of the economic burden of major parasitic helminth infections to the ruminant livestock industry in Europe. Prev Vet Med 182:105103. 10.1016/J.PREVETMED.2020.105103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimunová D, Navrátilová M, Kellerová P et al (2022) The induction and inhibition of UDP-glycosyltransferases in Haemonchus contortus and their role in the metabolism of albendazole. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 19:56–64. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2022.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary TG (2016) Haemonchus contortus: applications in drug discovery. Adv Parasitol 93:429–463. 10.1016/bs.apar.2016.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglioti R, Silva Ferreira JF da, Luciani GF et al (2022) Potential of Haemonchus contortus first-stage larvae to characterize anthelmintic resistance through P-glycoprotein gene expression. Small Ruminant Research 217:106864. 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2022.106864

- Gilleard JS (2013) Haemonchus contortus as a paradigm and model to study anthelmintic drug resistance. Parasitology 140:1506–1522. 10.1017/S0031182013001145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerová P, Matoušková P, Lamka J et al (2019) Ivermectin-induced changes in the expression of cytochromes P450 and efflux transporters in Haemonchus contortus female and male adults. Vet Parasitol 273:24–31. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerová P, Navrátilová M, Nguyen LT, et al (2020) UDP-Glycosyltransferases and albendazole metabolism in the juvenile stages of Haemonchus contortus. Front Physiol 11. 10.3389/fphys.2020.594116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kotze AC, Dobson RJ, Chandler D (2006) Synergism of rotenone by piperonyl butoxide in Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriformis in vitro: potential for drug-synergism through inhibition of nematode oxidative detoxification pathways. Vet Parasitol 136:275–282. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotze AC, Ruffell AP, Ingham AB (2014) Phenobarbital induction and chemical synergism demonstrate the role of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in detoxification of naphthalophos by Haemonchus contortus larvae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7475–7483. 10.1128/AAC.03333-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing R, Bartley DJ, Morrison AA et al (2015) The cytochrome P450 family in the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Int J Parasitol 45:243–251. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane J, Jubb T, Shephard R et al (2015) Priority list of endemic diseases for the red meat industries

- Lespine A, Martin S, Dupuy J et al (2007) Interaction of macrocyclic lactones with P-glycoprotein: structure-affinity relationship. Eur J Pharm Sci 30:84–94. 10.1016/j.ejps.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Landuyt B, Klaassen H et al (2019) Screening of a drug repurposing library with a nematode motility assay identifies promising anthelmintic hits against Cooperia oncophora and other ruminant parasites. Vet Parasitol 265:15–18. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G, Wang T, Korhonen PK et al (2018) Molecular alterations during larval development of Haemonchus contortus in vitro are under tight post-transcriptional control. Int J Parasitol 48:763–772. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matoušková P, Vokřál I, Lamka J, Skálová L (2016) The role of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes in anthelmintic deactivation and resistance in helminths. Trends Parasitol 32:481–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mes TH, Eysker M, Ploeger HW (2007) A simple, robust and semi-automated parasite egg isolation protocol. Nat Protoc 2:486–489. 10.1038/nprot.2007.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munguía B, Saldaña J, Nieves M et al (2022) Sensitivity of Haemonchus contortus to anthelmintics using different in vitro screening assays: a comparative study. Parasit Vectors 15. 10.1186/s13071-022-05253-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nielsen RB, Holm R, Pijpers I et al (2021) Oral etoposide and zosuquidar bioavailability in rats: effect of co-administration and in vitro-in vivo correlation of P-glycoprotein inhibition. Int J Pharm X 3:100089. 10.1016/j.ijpx.2021.100089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady J, Kotze AC (2004) Haemonchus contortus: in vitro drug screening assays with the adult life stage. Exp Parasitol 106:164–172. 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S, Jabbar A, Nowell C et al (2015) Low cost whole-organism screening of compounds for anthelmintic activity. Int J Parasitol 45:333–343. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S, Piedrafita D, Sandeman M, Cotton S (2019) The current status of anthelmintic resistance in a temperate region of Australia; implications for small ruminant farm management. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports 17:100313. 10.1016/J.VPRSR.2019.100313razaa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza A (2016) The role of drug efflux systems in anthelmintic resistance in parasitic nematodes. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The University of Queensland

- Raza A, Bagnall NH, Jabbar A, et al (2016a) Increased expression of ATP binding cassette transporter genes following exposure of Haemonchus contortus larvae to a high concentration of monepantel in vitro. Parasit Vectors 9. 10.1186/s13071-016-1806-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Raza A, Kopp SR, Bagnall NH et al (2016b) Effects of in vitro exposure to ivermectin and levamisole on the expression patterns of ABC transporters in Haemonchus contortus larvae. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 6:103–115. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza A, Kopp SR, Kotze AC (2016c) Synergism between ivermectin and the tyrosine kinase/P-glycoprotein inhibitor crizotinib against Haemonchus contortus larvae in vitro. Vet Parasitol 227:64–68. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza A, Kopp SR, Jabbar A, Kotze AC (2015) Effects of third generation P-glycoprotein inhibitors on the sensitivity of drug-resistant and -susceptible isolates of Haemonchus contortus to anthelmintics in vitro. Vet Parasitol 211:80–88. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman A, Abidi SMA (2022) Livestock health: current status of helminth infections and their control for sustainable development. In: Advances in Animal Experimentation and Modeling. Elsevier, pp 365–378

- Risi G, Aguilera E, Ladós E et al (2019) Caenorhabditis elegans infrared-based motility assay identified new hits for nematicide drug development. Vet Sci 6:29. 10.3390/vetsci6010029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwer A, Lutz J, Chassaing C et al (2012) Identification and profiling of nematicidal compounds in veterinary parasitology. Parasitic Helminths. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany, pp 135–157 [Google Scholar]

- Rose Vineer H, Morgan ER, Hertzberg H et al (2020) Increasing importance of anthelmintic resistance in European livestock: creation and meta-analysis of an open database. Parasite 27:69. 10.1051/parasite/2020062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufener L, Baur R, Kaminsky R et al (2010) Monepantel allosterically activates DEG-3/DES-2 channels of the gastrointestinal nematode Haemonchus contortus. Mol Pharmacol 78:895–902. 10.1124/mol.110.066498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarai RS, Kopp SR, Coleman GT, Kotze AC (2013) Acetylcholine receptor subunit and P-glycoprotein transcription patterns in levamisole-susceptible and -resistant Haemonchus contortus. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 3:51–58. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarai RS, Kopp SR, Coleman GT, Kotze AC (2014) Drug-efflux and target-site gene expression patterns in Haemonchus contortus larvae able to survive increasing concentrations of levamisole in vitro. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 4:77–84. 10.1016/J.IJPDDR.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuchlíková L, Jirásko R, Vokřál I et al (2014) Metabolic pathways of anthelmintic drug monepantel in sheep and in its parasite (Haemonchus contortus). Drug Test Anal 6:1055–1062. 10.1002/dta.1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuchlíková L, Matoušková P, Bártíková H et al (2015) Monepantel induces hepatic cytochromes p450 in sheep in vitro and in vivo. Chem Biol Interact 227:63–68. 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuchlíková LR, Matoušková P, Vokřál I et al (2018) Metabolism of albendazole, ricobendazole and flubendazole in Haemonchus contortus adults: sex differences, resistance-related differences and the identification of new metabolites. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 8:50–58. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2018.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Acosta JFJ, Mendoza-de-Gives P, Aguilar-Caballero AJ, Cuéllar-Ordaz JA (2012) Anthelmintic resistance in sheep farms: update of the situation in the American continent. Vet Parasitol 189:89–96. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuersong W, Liu X, Wang Y et al (2023) Comparative metabolome analyses of ivermectin-resistant and -susceptible strains of Haemonchus contortus. Animals 13:456. 10.3390/ani13030456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercruysse J, Charlier J, Van Dijk J et al (2018) Control of helminth ruminant infections by 2030. Parasitology 145:1655–1664. 10.1017/S003118201700227X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vokřál I, Bártíková H, Prchal L et al (2012) The metabolism of flubendazole and the activities of selected biotransformation enzymes in Haemonchus contortus strains susceptible and resistant to anthelmintics. Parasitology 139:1309–1316. 10.1017/s0031182012000595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vokřál I, Jedličková V, Jirásko R et al (2013a) The metabolic fate of ivermectin in host (Ovis aries) and parasite (Haemonchus contortus). Parasitology 140:361–367. 10.1017/S0031182012001680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vokřál I, Jirásko R, Stuchlíková L et al (2013b) Biotransformation of albendazole and activities of selected detoxification enzymes in Haemonchus contortus strains susceptible and resistant to anthelmintics. Vet Parasitol 196:373–381. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.