Abstract

Allergic conjunctivitis is a common ocular allergic condition. This study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) regarding allergic conjunctivitis among patients. A cross-sectional study was conducted at the outpatient clinic of the Eye Hospital of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences from March to June 2024. Patients completed an online self-designed questionnaire to gather demographic data and KAP scores, which were compared across demographics. Correlations among KAP scores were analyzed, and factors influencing practices were explored using multivariate logistic regression. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized to validate the KAP hypothesis. A total of 482 valid questionnaires were collected, yielding a validity rate of 93.77%. Among the respondents, 329 (68.26%) were female. The mean scores were 11.48 ± 6.90 (knowledge), 29.70 ± 4.33 (attitude), and 31.09 ± 8.71 (practice). Significant positive correlations were found between knowledge and attitude (r = 0.214, P < 0.001), knowledge and practice (r = 0.352, P < 0.001), and attitude and practice (r = 0.303, P < 0.001). SEM indicated that knowledge directly influenced attitude and, in turn, influenced practice. The study highlights a knowledge gap about allergic conjunctivitis, indicating a need for targeted educational interventions to improve attitudes and practices.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-87518-2.

Keywords: Allergic conjunctivitis, Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, Cross-sectional study

Subject terms: Eye diseases, Conjunctival diseases

Introduction

Allergic conjunctivitis is a common ocular surface disease that encompasses various subtypes, including perennial, seasonal, atopic, and vernal keratoconjunctivitis1–3. This condition is often associated with xerophthalmia and tear film instability, contributing to its complexity4. Epidemiological data indicate that allergic conjunctivitis affects approximately 15–20% of the general population in developed countries and 40–60% of individuals with allergies5,6. The primary symptoms—red, itchy eyes—have been described as ‘extremely bothersome,’ comparable to nasal congestion in allergic individuals7. These symptoms, along with tearing, photophobia, burning sensations, and increased secretions, significantly impair quality of life, complicating daily activities and affecting visual acuity8,9.

Exposure to allergens has increased due to environmental factors such as air pollution, as well as the frequent use of eye cosmetics and contact lenses. This has heightened the prevalence of IgE-mediated allergic reactions, reported to affect over 25% of the population outside China10–12. In severe cases, patients may develop corneal infections, posing a serious threat to their vision12,13. Treatment strategies for allergic conjunctivitis include antihistamines, short-term corticosteroids, mast cell stabilizers, and both subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy, aimed at providing symptomatic relief10,14,15. For patients with severe allergic conjunctivitis, immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine eye drops are also prescribed16. However, the challenge remains in the brief duration of efficacy of these eye drops in the conjunctival sac, which often leads to frequent relapses upon re-exposure to allergens17.

The knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) model posits that knowledge forms the foundation for behavior change, with attitudes and beliefs serving as the driving forces behind this transformation18. According to the KAP theory, the process of human behavior change unfolds in three sequential steps: the acquisition of knowledge, the formation of attitudes/beliefs, and the establishment of practices/behaviors19. While acquiring knowledge is crucial, it alone does not guarantee behavior change. Instead, it should precipitate a shift in perception, which in turn influences behavior20.

Recent years have seen a marked increase in the prevalence of allergic diseases, affecting 30–40% of the global population21. Identifying allergen sensitization is critical for providing tailored allergen avoidance education and prescribing personalized specific allergen immunotherapy22,23. Previous studies have highlighted a deficiency in patients’ understanding of their allergic conditions. For instance, among respiratory internal medicine asthma patients in Spain, only 49% were aware of all their allergens24. This gap in knowledge, coupled with poor attitudes but good practices among patients with allergic rhinitis (AR), underscores the complex relationship between knowledge, attitudes, and practices in managing allergic diseases.

Allergic diseases significantly impair quality of life and can lead to severe symptoms, necessitating a better understanding of disease management from the patient’s perspective. This understanding is essential for guiding clinical practices to improve treatment methods and educational strategies. Particularly for those suffering from allergic conjunctivitis, where daily life and vision can be severely affected, there is a distinct need for personalized and effective treatment strategies to enhance compliance and quality of life. However, to our knowledge, there has been no KAP study focused on Chinese patients with allergic conjunctivitis, underscoring the need for this research.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the outpatient clinic of the Eye Hospital of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences from March 1, 2024, to June 20, 2024, targeting patients diagnosed with allergic conjunctivitis. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Eye Hospital of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Approval No. YKEC-KT-2022-007-P004). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Presence of symptoms consistent with allergic conjunctivitis, such as itchy eyes, which may be accompanied by discomfort including burning sensations, dryness, redness, sensations of a foreign body, tearing, conjunctival congestion, plasma or mucus discharge, and/or bulbar conjunctival/eyelid edema25; (2) Age between 18 and 70 years, inclusive of both males and females; (3) Eyelid tissue not obscuring the conjunctival examination; (4) Ability to understand and willingness to complete the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Patients with infectious conjunctivitis, drug-toxic conjunctivitis, autoimmune keratoconjunctivitis, dry eye disease, or certain lacrimal duct diseases were excluded to ensure diagnostic specificity and rule out other differential diagnoses. No exclusion criteria were established initially; however, individuals who were unable to respond, as well as those who provided duplicate or incomplete responses to the questionnaire, were excluded during the subsequent analysis process.

Questionnaire and quality control

The questionnaire was initially piloted with 50 participants, achieving a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.926, which indicates high internal consistency. The questionnaire was structured into four sections: demographic information (including age, gender, medical history, etc.), knowledge, attitudes, and practices. This study aims to investigate the KAP concerning allergic conjunctivitis among affected patients. The questionnaire was designed with reference to the Chinese Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Allergic Conjunctivitis (2018) developed by the Ophthalmology Branch of the Chinese Medical Association. The questionnaire content was revised by three experts in the field of ophthalmology. Formal data were tested for reliability and validity after collection: the Cronbach’s coefficient for the total questionnaire was 0.982, and for knowledge, attitudes, and practices were 0.821, 0.869, and 0.921, respectively. In addition, the KMO value was 0.981.

In this study, the knowledge section is broadly divided into causes, symptoms, treatment modalities, and disease management of allergic conjunctivitis. The attitude section addresses the importance of the disease, the effectiveness of the treatments, and prognostic concerns. The practice section focuses on the actual practice of treatment and management of the disease. The knowledge section comprised 12 questions (excluding one control question) and utilized a scoring system where ‘very knowledgeable’ was awarded 2 points, ‘heard of it’ 1 point, and ‘unclear’ 0 points, with the total possible score ranging from 0 to 24. The attitudes section consisted of 8 questions, employing a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ (5 points) to ‘strongly disagree’ (1 point), and a total score range of 8 to 40. The practices section included 10 questions, also using a five-point Likert scale, with scoring from ‘always’ (5 points) to ‘never’ (1 point), and a total score range of 10 to 50. Scores exceeding 70% of the maximum possible in each section were considered indicative of adequate knowledge, a positive attitude, and proactive practice26.

Data collection was conducted using electronic questionnaires, accessible via QR code scans on WeChat, and paper copies distributed at the clinic. Initially, a total of 514 questionnaires were distributed. The exclusion criteria applied were as follows: (1) Refusal to participate (2 cases); (2) Response time under 90 s (15 cases); (3) Age below 18 years (5 cases); (4) Incorrect responses to control questions (10 cases). After these adjustments, 482 valid questionnaires remained. Prior to the administration of the questionnaire, the research team and support staff received training to ensure informed consent was properly obtained. Patients were informed about the study’s purpose and potential risks before participation, which was voluntary. The Ethics Review Committee reviewed all processes to ensure patient confidentiality and the non-disclosure of personal information. Researchers were instructed not to provide guidance during the questionnaire completion, allowing patients to respond based on their actual conditions and honestly.

A quality control manager oversaw adherence to standard operating procedures and supervised the survey’s quality control measures. Additionally, a data manager was responsible for data entry, editing, and management, ensuring the integrity of the collected information.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed on the demographic data of the respondents and their Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) scores. Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD), while categorical variables and responses to each question were presented as frequencies (percentages). Differences in knowledge (K), attitude (A) and practice (P) scores across various demographic groups were examined using univariate analysis for independent samples. For these intergroup comparisons, the Mann-Whitney U test was utilized for two groups, and the Kruskal-Wallis H test was employed for comparisons involving three or more groups. The relationships between knowledge, attitude, and practice scores were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

A binary logistic regression (univariate and multivariate) was conducted using 70% of the total practice score as cutoff as the dependent variable to identify potential risk factors in the demographic data. Univariate variables with P < 0.05 were enrolled in multivariate regression. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized to explore the interrelationships among knowledge (K), attitudes (A), and practices (P). All analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Basic information on the population

The mean age of participants was 38.26 ± 11.54 years. Of these participants, 329 (68.26%) were females, 233 (48.34%) held a bachelor’s degree, 267 (55.39%) reported allergies at sites other than the eyes, 372 (77.18%) had mild conjunctivitis, 136 (28.22%) used makeup daily, 121 (25.1%) owned pets, and 64 (13.28%) wore contact lenses or cosmetic lenses regularly.

The mean scores for knowledge, attitudes, and practices were 11.48 ± 6.90 (range 0–26), 29.70 ± 4.33 (range 8–40), and 31.09 ± 8.71 (range 10–50), respectively. Regarding unhealthy lifestyle habits, excessive use of electronic devices (356 cases) and eye rubbing (317 cases) were most frequently reported (Fig. 1). Demographic characteristics influenced the scores significantly; knowledge scores varied by gender (P = 0.019), residence (P = 0.008), and monthly household income per capita (P = 0.038). Attitude scores differed significantly across educational levels (P < 0.001), monthly household income per capita (P = 0.033), dry eye disease status (P = 0.005), family history of conjunctivitis (P < 0.001), and pet ownership (P < 0.001). Practice scores were influenced by residence (P = 0.002) and the presence of allergic diseases at other sites (P = 0.011) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Patients’ daily unhealthy lifestyle habits.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and KAP scores.

| Variables | N (%) | Knowledge, mean ± SD | P | Attitude, mean ± SD | P | Practice, mean ± SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 482 | 11.48 ± 6.90 | 29.70 ± 4.33 | 31.09 ± 8.71 | ||||

| Age | 38.26 ± 11.54 | ||||||

| Gender | 0.019 | 0.833 | 0.119 | ||||

| Male | 153 (31.74) | 10.37 ± 6.75 | 29.81 ± 4.36 | 30.05 ± 8.34 | |||

| Female | 329 (68.26) | 12.00 ± 6.92 | 29.65 ± 4.32 | 31.43 ± 8.87 | |||

| Residence | 0.008 | 0.562 | 0.002 | ||||

| Rural | 77 (15.98) | 9.42 ± 6.26 | 29.94 ± 4.03 | 28.32 ± 9.73 | |||

| Urban | 405 (84.02) | 11.87 ± 6.96 | 29.65 ± 4.39 | 31.61 ± 8.42 | |||

| Education | 0.092 | < 0.001 | 0.193 | ||||

| High school and below | 52 (10.79) | 10.73 ± 7.15 | 30.44 ± 4.98 | 31.02 ± 9.33 | |||

| Post-secondary degree | 78 (16.18) | 9.82 ± 6.55 | 31.05 ± 3.95 | 31.50 ± 8.73 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 233 (48.34) | 11.68 ± 6.67 | 30.04 ± 4.09 | 31.69 ± 8.73 | |||

| Master’s degree and above | 119 (24.69) | 12.50 ± 7.31 | 27.82 ± 4.18 | 29.66 ± 8.32 | |||

| Monthly household per capita income | 0.038 | 0.033 | 0.387 | ||||

| < 5000 | 119 (24.69) | 10.17 ± 6.95 | 30.23 ± 4.59 | 30.19 ± 9.94 | |||

| 5000–10,000 | 145 (30.08) | 11.09 ± 6.73 | 29.79 ± 4.38 | 31.04 ± 8.34 | |||

| 10,000–20,000 | 127 (26.35) | 12.16 ± 6.93 | 29.96 ± 4.20 | 31.61 ± 8.02 | |||

| > 20,000 | 91 (18.88) | 12.88 ± 6.80 | 28.49 ± 3.91 | 31.60 ± 8.56 | |||

| With allergic diseases in other parts of body | 0.578 | 0.074 | 0.011 | ||||

| Yes | 267 (55.39) | 11.62 ± 6.90 | 29.37 ± 3.97 | 32.00 ± 7.81 | |||

| No | 215 (44.61) | 11.31 ± 6.92 | 30.10 ± 4.72 | 29.96 ± 9.62 | |||

| With dry eye disease | 0.968 | 0.005 | 0.169 | ||||

| Yes | 246 (51.04) | 11.52 ± 6.80 | 29.19 ± 4.14 | 31.61 ± 7.39 | |||

| No | 236 (48.96) | 11.44 ± 7.03 | 30.23 ± 4.47 | 30.54 ± 9.89 | |||

| Have experienced eye surgery | 0.195 | 0.144 | 0.564 | ||||

| Yes | 60 (12.45) | 10.33 ± 6.66 | 28.95 ± 4.24 | 30.50 ± 7.38 | |||

| No | 422 (87.55) | 11.64 ± 6.93 | 29.81 ± 4.34 | 31.17 ± 8.89 | |||

| Severity of conjunctivitis | 0.898 | 0.223 | 0.222 | ||||

| Mild | 372 (77.18) | 11.42 ± 6.82 | 29.53 ± 4.33 | 30.71 ± 9.04 | |||

| Moderate | 93 (19.29) | 11.63 ± 7.21 | 30.20 ± 4.40 | 32.47 ± 7.34 | |||

| Severe | 17 (3.53) | 12.06 ± 7.34 | 30.71 ± .3.84 | 31.82 ± 7.94 | |||

| With immediate family members have conjunctivitis | 0.288 | < 0.001 | 0.442 | ||||

| Yes | 124 (25.73) | 11.04 ± 6.72 | 28.01 ± 3.95 | 31.57 ± 7.40 | |||

| No | 358 (74.27) | 11.63 ± 6.97 | 30.28 ± 4.31 | 30.92 ± 9.12 | |||

| Have a habit of wearing makeup daily | 0.764 | 0.540 | 0.345 | ||||

| Yes | 136 (28.22) | 11.25 ± 7.01 | 29.49 ± 4.18 | 30.51 ± 8.73 | |||

| No | 346 (71.78) | 11.57 ± 6.87 | 29.78 ± 4.39 | 31.32 ± 8.71 | |||

| Have pets | 0.118 | < 0.001 | 0.723 | ||||

| Yes | 121 (25.1) | 10.76 ± 7.05 | 28.49 ± 3.68 | 30.74 ± 7.82 | |||

| No | 361 (74.9) | 11.72 ± 6.85 | 30.11 ± 4.46 | 31.20 ± 9.00 | |||

| Wear contact lenses or cosmetic lenses daily | 0.570 | 0.984 | 0.777 | ||||

| Yes | 64 (13.28) | 11.13 ± 7.03 | 29.77 ± 4.48 | 31.67 ± 9.86 | |||

| No | 418 (86.72) | 11.54 ± 6.89 | 29.69 ± 4.31 | 31.00 ± 8.53 |

The distribution of knowledge, attitude, and practice scores

The distribution of knowledge scores revealed that the highest levels of uncertainty were reported for the statements: “Severe allergic conjunctivitis may require local or systemic anti-inflammatory treatment, such as cyclosporine eye drops or oral anti-allergy medications” (K6, 42.32% unclear), “Long-term allergic conjunctivitis may lead to allergic keratitis, increasing the risk of ocular complications” (K10, 39.63% unclear), and “Anti-allergy medications can alleviate symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis, such as antihistamines and corticosteroid eye drops” (K5, 35.68% unclear) (Table S1).

In terms of attitudes, 34.33% strongly agreed that allergic conjunctivitis impacts their quality of life (A1), 32.57% strongly agreed it affects their work or study (A2), and 25.73% were highly concerned about disease recurrence (A6). Additionally, 31.54% agreed that the treatment process was cumbersome (A7) (Table S2).

Responses to the practice dimension indicated that 28.01% never undertook allergen testing to monitor their allergen sensitivity (P10), 19.5% never used medications for allergic conjunctivitis regularly (P1), and 19.29% never timely changed or cleaned their glasses or contact lenses to prevent allergic conjunctivitis (P6) (Table S3).

Correlation between knowledge, attitude, and practice

Further analysis revealed positive correlations between knowledge and attitude scores (r = 0.214, P < 0.001), knowledge and practice scores (r = 0.352, P < 0.001), and between attitude and practice scores (r = 0.303, P < 0.001) (Table S4).

The multivariate analysis of practice

Multivariate logistic regression showed that knowledge score (OR 1.057, 95% CI [1.024–1.092], P < 0.001), attitude score (OR 1.194, 95% CI [1.129–1.262], P < 0.001), being male (OR 0.585, 95% CI [0.356–0.959], P = 0.034), and rubbing their eyes with hands (OR 0.559, 95% CI [0.354–0.883], P = 0.013) were independently associated with practice (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of factors influencing practices.

| Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Knowledge scores | 1.087 (1.054–1.120) | < 0.001 | 1.057 (1.024–1.092) | < 0.001 |

| Attitude scores | 1.208 (1.146–1.273) | < 0.001 | 1.194 (1.129–1.262) | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.012 (0.995–1.029) | 0.164 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 0.618 (0.396–0.966) | 0.035 | 0.585 (0.356–0.959) | 0.034 |

| Female | ref | ref | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | ref | |||

| Urban | 1.504 (0.843–2.683) | 0.167 | ||

| Education | ||||

| High school and below | ref | |||

| College | 1.228 (0.543–2.778) | 0.622 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 1.645 (0.817–3.315) | 0.164 | ||

| Master’s degree and above | 1.026 (0.474–2.219) | 0.949 | ||

| Average monthly household income | ||||

| < 5000 | ref | |||

| 5000–10,000 | 1.158 (0.672–1.995) | 0.598 | ||

| 10,000–20,000 | 1.038 (0.588–1.830) | 0.898 | ||

| > 20,000 | 1.467 (0.808–2.662) | 0.208 | ||

| With allergic diseases in other parts of body | ||||

| Yes | 1.428 (0.954–2.136) | 0.084 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| With dry eye disease | ||||

| Yes | 0.870 (0.586–1.291) | 0.489 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| Have experienced eye surgery | ||||

| Yes | 0.657 (0.344–1.257) | 0.205 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| Severity of conjunctivitis | ||||

| Mild | ref | |||

| Moderate | 1.517 (0.936–2.458) | 0.091 | ||

| Severe | 1.504 (0.542–4.175) | 0.433 | ||

| With immediate family members have conjunctivitis | ||||

| Yes | 1.082 (0.691–1.694) | 0.730 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| Wear makeup regularly | ||||

| Yes | 0.818 (0.522–1.280) | 0.378 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| Have pets | ||||

| Yes | 0.729 (0.454–1.171) | 0.191 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| Wear contact lenses or beauty lenses regularly | ||||

| Yes | 1.156 (0.654–2.043) | 0.619 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| Smoke | ||||

| Yes | 0.771 (0.423–1.407) | 0.397 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| Drink | ||||

| Yes | 0.716 (0.424–1.211) | 0.213 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| Use electronic products excessively | ||||

| Yes | 0.637 (0.412–0.983) | 0.042 | 0.702 (0.433–1.138) | 0.151 |

| No | ref | ref | ||

| Rub eyes with hands | ||||

| Yes | 0.547 (0.364–0.822) | 0.004 | 0.559 (0.354–0.883) | 0.013 |

| No | ref | ref | ||

| Go out for exercise rarely | ||||

| Yes | 1.179 (0.793–1.753) | 0.415 | ||

| No | ref | |||

| Consume seafood, spicy foods, allergens, or sweet and greasy foods frequently | ||||

| Yes | 0.932 (0.626–1.389) | 0.730 | ||

| No | ref | |||

Structural equation modeling

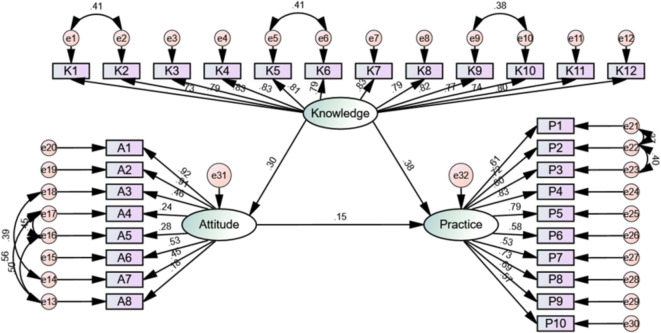

The structural model’s fit indices (CMIN/DF = 3.639, RMSEA = 0.074; IFI = 0.893; TLI = 0.881; CFI = 0.892) exceeded the respective threshold values, indicating a satisfactory fit (Table 3). SEM demonstrated that knowledge directly influenced attitude (β = 0.092, P = 0.001) and attitude influenced practice (β = 0.780, P = 0.017) (Table S5 and Fig. 2). Knowledge had direct effects on both attitude (β = 0.302, P = 0.009) and practice (β = 0.378, P = 0.011), while attitude directly impacted practice (β = 0.148, P = 0.010). Knowledge also indirectly affected practice through attitude (β = 0.045, P = 0.006) (Table 4; Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Fit Indices of the structural equation model (SEM).

| Model fit indices | Ref. | Measured results |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | 1–3 excellent, 3–5 good | 3.639 |

| RMSEA | < 0.08 good | 0.074 |

| IFI | > 0.8 good | 0.893 |

| TLI | > 0.8 good | 0.881 |

| CFI | > 0.8 good | 0.892 |

Fig. 2.

Structural equation model diagram.

Table 4.

Direct and indirect effects of the SEM model.

| Model paths | Standardized total effects | Standardized direct effects | Standardized indirect effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P | β (95%CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | |

| Knowledge → Attitude | 0.302 (0.193–0.394) | 0.009 | 0.302 (0.193–0.394) | 0.009 | ||

| Knowledge → Practice | 0.422 (0.318–0.498) | 0.012 | 0.378 (0.276–0.479) | 0.011 | ||

| Attitude → Practice | 0.148 (0.042–0.253) | 0.010 | 0.148 (0.042–0.253) | 0.010 | ||

| Knowledge → Practice | 0.045 (0.013–0.087) | 0.006 | ||||

Discussion

The study indicates that while patients generally exhibit positive attitudes towards managing allergic conjunctivitis, their knowledge level remains inadequate, and actual practices are insufficiently proactive. To enhance patient outcomes, it is crucial for healthcare providers to implement targeted educational programs that not only increase patient knowledge but also encourage the translation of positive attitudes into consistent, effective self-management practices.

This study underscores a critical deficiency in the awareness of allergic diseases among patients, despite generally positive behaviors and passive practices in managing allergic conjunctivitis. Notably, a previous study revealed that a significant majority of caregivers for children with conjunctivitis were unaware of the symptoms of the disease (69.2%), and a staggering 83% did not know the side effects of the prescribed eye drops27. Similar trends of knowledge deficits coupled with suboptimal attitudes were observed among patients with other allergic conditions. For instance, a study in China found that patients with allergic rhinitis exhibited positive behaviors but lacked sufficient knowledge and displayed poor attitudes towards their condition28. Moreover, research on asthma patients highlighted a pervasive lack of understanding about the allergic nature of their disease, with only 49% of patients being aware of all their allergens24. These findings collectively suggest that insufficient proactive management approaches among patients might contribute to suboptimal disease control and management outcomes.

Significant differences were observed across various demographic variables. For instance, knowledge scores significantly differed by gender, with males scoring lower than females, and by residence, with urban residents scoring higher than rural ones. These differences were supported by multivariate logistic regression, which also indicated that being male was associated with lower practice scores, suggesting gender-specific barriers to effective disease management29. Similarly, educational attainment significantly affected attitudes, highlighting the role of socio-economic factors in shaping health perceptions30, a finding mirrored in the attitudes’ influence on practices in both correlation and regression analyses.

The lack of differences in practice scores with respect to education, despite variations in knowledge and attitudes, suggests that other unmeasured factors such as accessibility to healthcare services or cultural influences might play a role31. The influence of pet ownership on attitudes but not on practices might be due to the emotional and psychological support pets provide, which does not necessarily translate into proactive health behaviors32. The SEM results further confirmed these direct and indirect effects, illustrating that enhanced knowledge could elevate practice levels indirectly by modifying attitudes.

In the knowledge dimension, a notable proportion of participants indicated uncertainty about several key aspects of allergic conjunctivitis, such as the potential severity of the disease and the specifics of its treatment. This gap is particularly significant in the understanding of how severe allergic reactions may require systemic treatment, and the role of allergen avoidance in preventing outbreaks. Previous study have shown similar trends where patient awareness significantly impacts their management of chronic conditions33. To improve these knowledge gaps, targeted educational programs should be developed, focusing on the severity and chronic nature of allergic conjunctivitis, the importance of regular environmental cleaning, and the effectiveness of various treatment options. These programs could be integrated into routine clinical visits and supported by online resources and workshops, ensuring that they are accessible and practical for patients to implement34,35.

Regarding attitudes, while a majority of patients recognize the impact of allergic conjunctivitis on their quality of life, there is a significant perception that treatment costs are high and the treatment process cumbersome. This could deter adherence to recommended management practices. To address these concerns, healthcare providers could offer clear communication about treatment options and expected outcomes, potentially through personalized treatment plans that are cost-effective and less burdensome. Furthermore, establishing patient support groups could help individuals feel more optimistic about their prognosis by sharing experiences and strategies for managing the disease effectively36,37.

The practice dimension shows that a significant number of patients do not consistently use medication or follow preventive measures such as regular allergen testing and environmental cleaning. This inconsistency may be linked to the previously noted gaps in knowledge and less positive attitudes towards the treatment process. Healthcare professionals should thus focus on reinforcing the importance of consistent medication use, regular follow-ups, and environmental management through structured education programs. Additionally, simplifying treatment regimens and providing reminders via digital tools like mobile apps could enhance adherence and make disease management less overwhelming for patients38,39.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to establish causality between knowledge, attitudes, and practices among patients with allergic conjunctivitis. Second, the use of an online questionnaire may have introduced selection bias, as it likely excluded patients without internet access or those less proficient with digital technology, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings. Third, the study was conducted at a single center, the Eye Hospital of the China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, which may limit the applicability of the results to other geographic or demographic settings where patient experiences and access to healthcare might differ.

In conclusion, patients demonstrated inadequate knowledge, positive attitudes, and insufficiently proactive practices in managing allergic conjunctivitis. Enhancing patient education programs on allergic conjunctivitis could significantly improve both attitudes and practices, potentially leading to better management and outcomes for sufferers.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Ke Song, Shanshan Ye, Jiantao Song and Zefeng Kang carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Ke Song and Shanshan Ye performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. This work was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Eye Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (YKEC-KT-2022-007-P004). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alqurashi, K. A., Bamahfouz, A. Y. & Almasoudi, B. M. Prevalence and causative agents of allergic conjunctivitis and its determinants in adult citizens of Western Saudi Arabia: A survey. Oman J. Ophthalmol.13, 29–33 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller, A. Allergic conjunctivitis: An update. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol.268, 95–99 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villegas, B. V. & Benitez-Del-Castillo, J. M. Current knowledge in allergic conjunctivitis. Turk. J. Ophthalmol.51, 45–54 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villani, E., Rabbiolo, G. & Nucci, P. Ocular allergy as a risk factor for dry eye in adults and children. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol.18, 398–403 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonardi, A. et al. Ocular allergy: Recognizing and diagnosing hypersensitivity disorders of the ocular surface. Allergy67, 1327–1337 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosario, N. & Bielory, L. Epidemiology of allergic conjunctivitis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol.11, 471–476 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bielory, L. et al. Ocular and nasal allergy symptom burden in America: The allergies, immunotherapy, and rhinoconjunctivitis (AIRS) surveys. Allergy Asthma Proc.35, 211–218 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonardi, A. Allergy and allergic mediators in tears. Exp. Eye Res.117, 106–117 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virchow, J. C. et al. Impact of ocular symptoms on quality of life (QoL), work productivity and resource utilisation in allergic rhinitis patients—An observational, cross sectional study in four countries in Europe. J. Med. Econ.14, 305–314 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger, W. E., Granet, D. B. & Kabat, A. G. Diagnosis and management of allergic conjunctivitis in pediatric patients. Allergy Asthma Proc.38, 16–27 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding, Y. et al. Quercetin as a Lyn kinase inhibitor inhibits IgE-mediated allergic conjunctivitis. Food Chem. Toxicol.135, 110924 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazaki, D. et al. Epidemiological aspects of allergic conjunctivitis. Allergol. Int.69, 487–495 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuruvilla, M., Kalangara, J. & Lee, F. E. E. Neuropathic pain and itch mechanisms underlying allergic conjunctivitis. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol.29, 349–356 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elieh Ali Komi, D., Rambasek, T. & Bielory, L. Clinical implications of mast cell involvement in allergic conjunctivitis. Allergy73, 528–539 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fauquert, J. L. Diagnosing and managing allergic conjunctivitis in childhood: The allergist’s perspective. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol.30, 405–414 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vazirani, J. et al. Allergic conjunctivitis in children: Current understanding and future perspectives. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol.20, 507–515 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zi, Y. et al. The effectiveness of olopatadine hydrochloride eye drops for allergic conjunctivitis: Protocol for a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore)99, e18618 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao, L. et al. Medical and non-medical students’ knowledge, attitude and willingness towards the COVID-19 vaccine in China: A cross-sectional online survey. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother.18, 2073757 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Twinamasiko, N. et al. Assessing knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19 public health preventive measures among patients at Mulago National Referral Hospital. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy14, 221–230 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, J., Chen, L., Yu, M. & He, J. Impact of knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP)-based rehabilitation education on the KAP of patients with intervertebral disc herniation. Ann. Palliat. Med.9, 388–393 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters, R. L., Mavoa, S. & Koplin, J. J. An overview of environmental risk factors for food allergy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19, 722 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casale, T. B. et al. The role of aeroallergen sensitization testing in asthma management. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract.8, 2526–2532 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klimek, L. et al. ARIA guideline 2019: Treatment of allergic rhinitis in the German health system. Allergol. Sel.3, 22–50 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roger, A. et al. Knowledge of their own allergic sensitizations in asthmatic patients and its impact on the level of asthma control. Arch. Bronconeumol.49, 289–296 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts, G. et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Allergy73, 765–798 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, F. & Suryohusodo, A. A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice assessment toward COVID-19 among communities in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health10, 957630 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wadhwani, M., Kursange, S., Chopra, K., Singh, R. & Kumari, S. Knowledge, attitude, and practice among caregivers of children with vernal keratoconjunctivitis in a tertiary care pediatric hospital. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus58, 390–395 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu, W. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice towards allergic rhinitis in patients with allergic rhinitis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health23, 1633 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandt, G. et al. Medical students’ perspectives on LGBTQI+ healthcare and education in Germany: Results of a nationwide online survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19, 10010 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghuloum, S., Mahfoud, Z. R., Al-Amin, H., Marji, T. & Kehyayan, V. Healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward patients with mental illness: A cross-sectional study in Qatar. Front. Psychiatry13, 884947 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oshodi, T. O. et al. Registered nurses’ perceptions and experiences of autonomy: A descriptive phenomenological study. BMC Nurs.18, 51 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang, L., Liu, S., Li, H., Xie, L. & Jiang, Y. The role of health beliefs in affecting patients’ chronic diabetic complication screening: A path analysis based on the health belief model. J. Clin. Nurs.30, 2948–2959 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cilli, E., Ranieri, J., Guerra, F., Ferri, C. & Di Giacomo, D. Naturalizing digital and quality of life in chronic diseases: Systematic review to research perspective into technological advancing and personalized medicine. Digit. Health8, 20552076221144857 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bielory, L. et al. ICON: Diagnosis and management of allergic conjunctivitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol.124, 118–134 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iordache, A. et al. Relationship between allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis (allergic rhinoconjunctivitis)—Review. Rom. J. Ophthalmol.66, 8–12 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leonardi, A. et al. Allergic conjunctivitis management: Update on ophthalmic solutions. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep.24, 347–360 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sacchetti, M. et al. Allergic conjunctivitis: Current concepts on pathogenesis and management. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents32, 49–60 (2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kassumeh, S., Brunner, B. S., Priglinger, S. G. & Messmer, E. M. New and future treatment approaches for allergic conjunctivitis. Ophthalmologie121, 180–186 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kausar, A., Akhtar, N. & Akbar, N. Epidemiological aspects of allergic conjunctivitis. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad34, 135–140 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.