Abstract

Background

Cystinosis is a rare, incurable lysosomal storage disease caused by mutations in the CTNS gene encoding the cystine transporter cystinosin, which leads to lysosomal cystine accumulation in all cells of the body. Patients with cystinosis display signs of podocyte damage characterized by extensive loss of podocytes into the urine at early disease stages, glomerular proteinuria, and the development of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) lesions. Although standard treatment with cysteamine decreases cellular cystine levels, it neither reverses glomerular injury nor prevents the loss of podocytes. Thus, pathogenic mechanisms other than cystine accumulation are involved in podocyte dysfunction in cystinosis.

Methods

We used immortalized patient-derived cystinosis, healthy, and CTNS knockdown podocytes to investigate podocyte dysfunction in cystinosis. The results were validated in our newly in-house developed fluorescent ctns−/−[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)] zebrafish larvae model. To understand impaired podocyte functionality, static and dynamic permeability assays, tracer-metabolomic analysis, flow cytometry, western blot, and chemical and dynamic redox-sensing fluorescent probes were used.

Results

In the current study, we discovered that cystinosis podocytes demonstrate increased ferroptotic cell death caused by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS)-driven membrane lipid peroxidation. Moreover, cystinosis cells present a fragmented mitochondrial network with impaired tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) cycle and energy metabolism. Targeting mitochondrial ROS and lipid peroxidation improved podocyte function in vitro and rescued proteinuria in vivo in cystinosis zebrafish larvae.

Conclusions

Mitochondrial ROS contribute to podocyte injury in cystinosis by driving lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, which in turn lead to podocyte detachment. This finding adds cystinosis to the list of podocytopathies associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. The identified mechanisms reveal new therapeutic targets and highlight lipid peroxidation as an exploitable vulnerability of cystinosis podocytes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-024-05996-w.

Keywords: Cystinosis, Podocyte, Mitochondrial oxidative stress, Lipid peroxidation, Ferroptosis, ctns−/−[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)] zebrafish larvae model, MitoTEMPO, Liproxstatin-1

Introduction

Cystinosis is an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disease caused by bi-allelic mutations in the CTNS gene, which encodes the lysosomal cystine-proton co-transporter cystinosin that carries cystine from the lysosomal lumen to the cytosol [1, 2]. Cystinosin is ubiquitously expressed, and mutations in this protein lead to lysosomal cystine accumulation in all cells of the body. Although cystinosis is a multisystemic disease, kidneys are the most severely affected organs, with renal Fanconi syndrome being the early clinical feature of the disease [1, 3]. The standard treatment for cystinosis is the aminothiol cysteamine, which depletes lysosomal cystine by formation of cysteine and cysteamine-cysteine mixed disulfide, which can exit lysosomes via cysteine and PQLC2 transporters, respectively [4]. Cysteamine treatment postpones the deterioration of kidney function and delays the development of extra-renal complications, but it neither reverses renal Fanconi syndrome nor prevents kidney failure. Therefore, the majority of patients with cystinosis still undergo dialysis and transplantation during adolescence or early adult age [5–7].

While cystinosis is an archetypal proximal tubular disorder [1], patients also present with progressive glomerular dysfunction, characterized by the presence of high molecular weight (HMW) proteinuria and excessive shedding of podocytes into urine at an early age [8, 9]. Kidney biopsies are not routinely performed in patients with cystinosis; therefore, histological data are limited. Nevertheless, the presence of giant multinuclear podocytes is pathognomonic for cystinosis glomeruli, followed by the formation of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis lesions progressing to total glomerular collapse at advanced disease stages, despite cysteamine treatment [8, 10–12]. Excessive detachment and loss of podocytes into urine are present in patients with cystinosis in parallel with proximal tubular epithelial cell (PTEC) dysfunction, which is accompanied by alterations in the podocyte cytoskeleton and impaired protein kinase signaling [9].

Studies in cystinosis PTEC have convincingly demonstrated that cystinosin deficiency leads to mitochondrial dysfunction by affecting mitochondrial dynamics, decreasing cAMP levels and impairing mitophagy, providing a mechanistic basis for decreased ATP synthesis and increased generation of oxidative species [13–17].

In this study, we hypothesized that mitochondrial dysfunction may be also involved in podocyte dysfunction in cystinosis. Our findings demonstrate that cystinosis podocytes display impaired mitochondrial metabolism and increased mitochondrial ROS, the latter of which drives lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Importantly, targeting mitochondrial oxidative stress or lipid peroxidation improves podocyte function and restores the functionality of the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) in a cystinosis zebrafish larval model. These results provide a new direction for novel therapeutic approaches in cystinosis.

Methods

Cell culture and compounds

Unrelated cystinosis patient-derived podocyte cell lines (CTNS−/−#1 and CTNS−/−#2) carrying a 57Kb deletion on chromosome 17p13.2 and healthy podocytes (WT) were generated, conditionally immortalized and characterized in previous studies [9, 18]. Briefly, the urine was centrifuged at 300 xg for 5 min. Then, the pellet was washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/Ham’s F-12 (DMEM F-12, Biowest), supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Biowest), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Westburg), and 1% Insulin, Transferrin, and Selenium (ITS, Sigma). Podocytes were immortalized and subcloned using a temperature-sensitive Simian Virus 40 large T antigen (SV40T) and human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) telomerase [9]. The experiments were performed after 10 days of differentiation at 37 °C. Clinical characteristics of patients are presented in Additional file 2: Table S1. The following compounds (24-48h incubation) were used: 100 µM cysteamine (Sigma), 10 µM MitoTEMPO (Sigma) and 10 µM liproxstatin-1 (Selleckchem). HEK293T cells were cultured in high-glucose (4.5 g/l) DMEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Biowest) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Westburg).

Knockdown strategy and qPCR validation

CTNS knockdown was achieved in the wild-type (WT) podocyte line using an shRNA-expressing lentiviral vector (pLKO.1-shRNA) sourced from the Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms (BCCM). Two unique shRNA sequences were used to specifically target CTNS, generating two independent CTNS knockdown cell lines, termed shCTNS#1 and shCTNS#2:

shCTNS#1: CCGGGCCACCATTAAATGCAACCCTCTCGAGAGGGTTGCATTTAATGGTGGCTTTTTG

shCTNS#2: CCGGGTTGGACAACTTACTGTTTATCTCGAGATAAACAGTAAGTTGTCCAACTTTTTG

A control cell line (shCTR) was generated using a non-targeting shRNA sequence to confirm that any observed effects were specific to CTNS knockdown.

Lentiviral particles were produced in HEK293T cells, and transduction was conducted overnight on WT podocytes at 33 °C. The medium was then refreshed, and cells successfully transduced were selected using puromycin (1 μg/ml). Knockdown efficacy was validated by measuring cystine levels and assessing CTNS mRNA expression via qPCR.

To ensure that the newly generated isogenic cell lines retained podocyte identity, we confirmed the expression of several podocyte-specific markers, including C2AP, PODXL, SYNPO, and WT1. This marker panel confirmed the podocyte phenotype across all cell lines (Additional file 2: Figure S1).

For qPCR analysis, total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Quantitative PCR was conducted on the StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher) using Platinum® SYBR® Green SuperMix-UDG with ROX (Thermo Fisher). Each reaction included 0.2 μM of each primer and 1 μl of cDNA (5 ng/μl). Expression levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene β-ACTIN. Primers used for qPCR were as follows:

CTNS: FW: 5′-CAGCGCCATTAGCATCATAAA-3′, RV: 5′-GAAACTGCTCCTTGATGTA-3′

C2AP: FW: 5′-AGGCTGGTGGAGTGGAAC-3′, RV: 5′-CAGAGAAGGTATAGGTGAAGTAGG-3′

PODXL: FW: 5′-CTTGAGACACAGACACAGAG-3′, RV: 5′-CCGTATGCCGCACTTATC-3′

SYNPO: FW: 5′-AGCCCAAGGTGACCCCGAAT-3′, RV: 5′-CCCTGTCACGAGGTGCTGGC-3′

WT1: FW: 5′-GGACAGAAGGGCAGAGCAACCA-3′, RV: 5′-GTCTCAGATGCCGACCGTACAA-3′

β-ACTIN: FW: 5′-AAGAGCTACGAGCTGCCTGA-3′, RV: 5′-GACTCCATGCCCAGGAAGG-3′

13C6-glucose labeling and mass spectrometry

After 10 days of differentiation, podocytes were cultured in DMEM-F12 without glucose (Biowest) and supplemented with 17.49 mM 13C6-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) for 48 h. Cells were washed with ice-cold 0.9% w/v NaCl solution and metabolites were extracted using 80% v/v methanol and 0.2% w/v myristic acid-d27 as the internal standard. Following extraction, measurements were performed using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 LC System (Thermo Scientific) coupled with a Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) operated in negative mode. Briefly, 10 μl of the sample was injected onto a Poroshell 120 HILIC-Z PEEK Column (Agilent InfinityLab). A linear gradient was applied starting with 90% solvent A (acetonitrile) and 10% solvent B (10 mM Na-acetate in mqH2O, pH 9.3). From 2 to 12 min, the gradient was changed to 60% B. The gradient was maintained at 60% B for 3 min and then decreased to 10% B. The chromatography was stopped at 25 min. The flow rate was constant at 0.25 ml/min. The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C. The mass spectrometer was operated in full scan (range 70–1050) and negative mode using a spray voltage of 2.8 kV, capillary temperature of 320 °C, sheath gas at 45 u and auxiliary gas at 10 u. The AGC target was set at 3.0E + 006, using a resolution of 70,000. Data were collected using Xcalibur software (Thermo Scientific). Data analysis was performed by integrating the peak areas (Elucidata). The raw abundance values of metabolites were normalized to the internal standard (myristic acid-d27) and protein levels.

RoGFP2-based redox imaging and quantification of the mitochondrial network

Plasmids encoding cytosolic (pMF1707), peroxisomal (pMF1706), or mitochondrial (pMF1762) roGFP2 were purified using the PureLink™ HiPure Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Thermo Scientific) as previously described [19–21]. Podocytes were transfected using JetPRIME reagent and fluorescence was evaluated using an inverted IX-81 microscope (Olympus) equipped with a temperature and CO2-controlled chamber. Ratiometric measurements were performed as described previously [20]. Briefly, the camera exposure times were set at a ratio of 1:2 to acquire images at 400 (for GSSG) and 480 (for GSH) nm excitation wavelengths, respectively. Random fields of cells were imaged with the same 400/480 nm exposure time ratios, and images with signal intensities within the linear dynamic range of the camera were retained for analysis using cellSens image software (Olympus). Mitochondrial network quantification was performed as previously described [22]. Briefly, pictures containing the podocytes expressing the mitochondrial roGFP2 were processed using the following workflow using ImageJ software: 1. “Process→Filters→Unsharp Mask”; 2. “Process→Enhance local contrast (CLAHE)” (omit fast option); 3. “Process→Binary→ Make binary”; 4. “Process→Binary→ Skeletonize”; 5. Analyze→Skeleton→Analyze Skeleton (2D/3D). The number of fragments (mitochondrial independent network unit expressed as a skeleton) was normalized relative to the total cell surface area. Original images for Fig. 1e-f, along with the final morphological skeletons generated by the macro tool, can be found in Additional File 3.

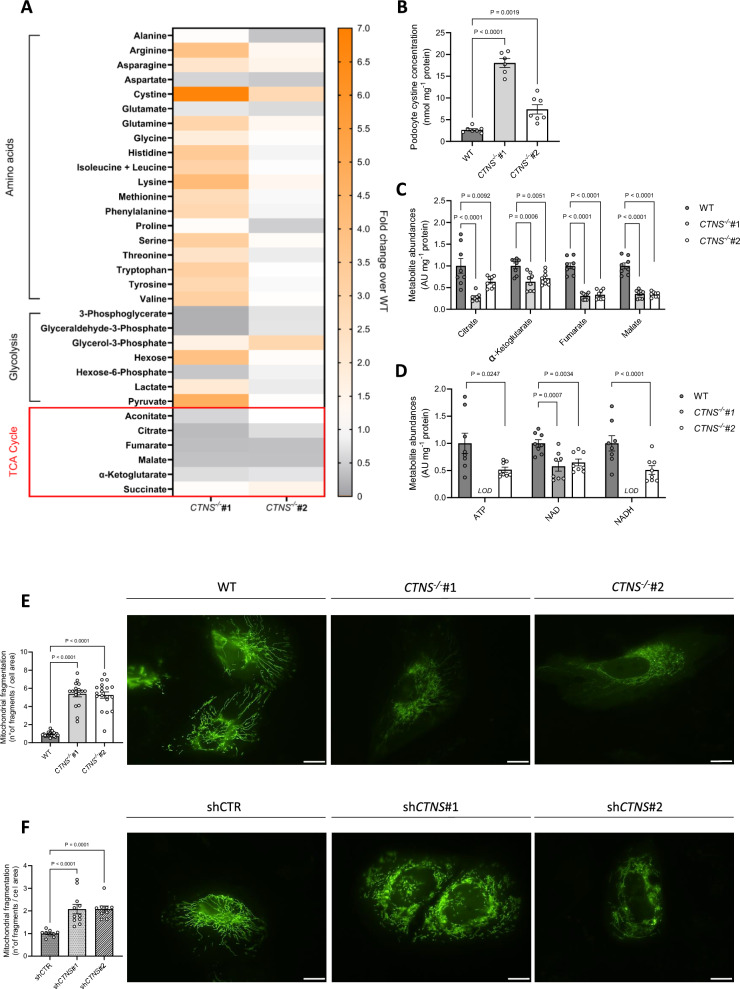

Fig. 1.

Cystinosis podocytes display impaired mitochondrial metabolism and a fragmented mitochondrial network. a. Intracellular metabolite levels in CTNS−/−#1 and CTNS−/−#2 normalized to WT podocytes measured by LC–MS (n = 3 biological experiments, n ≥ 2 technical replicates). b. Cystine concentrations in WT, CTNS−/−#1, and CTNS−/−#2, expressed as nmol mg⁻1 protein. (n ≥ 6 biological experiments, n = 2 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s one-way ANOVA. (c, d) c. Citrate, α-ketoglutarate, fumarate, and malate levels in CTNS−/−#1 and CTNS−/−#2, normalized to WT podocytes and protein (mg⁻1), d. ATP, NAD, and NADH levels in CTNS−/−#1 and CTNS−/−#2, normalized to WT podocytes and protein (mg⁻1). (n = 3 biological experiments, n ≥ 2 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: linear mixed model for each metabolite. AU = arbitrary units. LOD = below the limit of detection. Each dot represents a technical replicate. (e, f) Mitochondrial fragmentation in cells expressing the mitochondrial roGFP2 redox sensor. Left panel: quantification of mitochondrial fragmentation (number of fragments normalized to cell area) in e. CTNS−/−#1 and CTNS−/−#2 normalized to WT podocytes; f. shCTNS#1 and shCTNS#2 normalized to shCTR. (n = 4 biological experiments, n ≥ 4 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: linear mixed model. Each dot represents an individual cell measurement. Right panels: representative images of mitochondrial networks. Scale bar: 20 μm. Unless noted, each dot represents a biological experiment

Seahorse XFe96 mitochondrial analysis

Mitochondrial function in podocytes was analyzed using the Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer and the MitoStressTest protocol (Agilent Technologies). Podocytes were seeded at a density of 20,000 cells per well on XFe96 cell culture microplates (Agilent Technologies) and differentiated in podocyte medium for 10 days at 37 °C. Optimization of cell density and the working concentrations of mitochondrial inhibitors were conducted in preliminary experiments to ensure robust assay performance. On the assay day, XF DMEM assay medium (pH 7.4) was prepared by supplementing XF DMEM Base Medium (Agilent Technologies) with 25 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate, and 2 mM glutamine. Cells were washed and incubated with the assay medium, then equilibrated for 45 min at 37 °C in a non-CO₂ incubator to stabilize their metabolic state prior to measurements. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was monitored to evaluate mitochondrial function. Baseline OCR measurements were recorded over four cycles to establish basal respiration. Mitochondrial inhibitors were sequentially injected to target specific respiratory chain complexes. Oligomycin (1.5 µM) was used to inhibit ATP synthase (Complex V) and assess ATP-linked respiration. FCCP (2 µM) was injected to uncouple oxidative phosphorylation, measuring maximal respiration capacity. Finally, antimycin A (2.5 µM) and rotenone (1.25 µM) were added to inhibit Complex III and Complex I, respectively, determining non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption. For each phase of the experiment, OCR measurements were recorded over three cycles to capture the cellular response to the inhibitors. Data analysis was performed using the Seahorse XFe96 WAVE software (version 2.6.3.5, Agilent Technologies). OCR values were normalized to protein concentration in each well, quantified using the BCA protein assay.

Superoxide anion detection

Cells were incubated with MitoSOX (5 μM) for 25 min at 37 °C. Following incubation, cells were washed with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) to remove any unbound dye. Fluorescence intensities were then measured using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices SpectraMax iD3) with excitation at 510 nm and emission at 580 nm. Fluorescence readings were normalized to protein concentrations to account for differences in cell number.

Western blot

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with protease (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (Merck Sigma). Protein concentration was determined using a standard protein assay, and at least 15 μg of each sample was loaded onto a NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis–Tris gel (Thermo Scientific). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using the iBlot2 system (Thermo Scientific). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk in TBS-T, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2; Abcam #13,194, 1:1000), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE; Abcam #ab46545, 1:1000) or β-actin (Merck Sigma #A5441, 1:10,000). Following primary antibody incubation, membranes were incubated with HRP-linked anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Dako) for 1 h at room temperature. Chemiluminescent signals were captured using a Syngene Chemi XRQ System. Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ software, and protein expression was normalized to to β-actin as the loading control. For quantification of 4-HNE data, the total band intensities of all 4-HNE adducts under each condition were calculated and normalized to β-actin.

Flow cytometry

Podocytes were collected and stained with 10 μM of the lipid peroxidation sensor BODIPY™ 581/591 C11 (Thermo Scientific) and ZombieNIR viability dye (Biolegend 1:1000) for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark [23]. Cells incubated with 10 µM of the ferroptosis inducer RSL3 (Selleckchem) for 30 min were used as positive control. After staining, the cells were resuspended in FACS buffer (3% FBS, 2.5 mM EDTA in PBS) for flow cytometric analysis. The samples were analyzed using a BD Fortessa (BDBiosciences) flow cytometer, and data were processed using FlowJo software.

Adhesion assay

Equal amounts of podocytes were seeded in 24-well plates for high-throughput microscopy (Ibidi). After allowing the cells to attach by incubating them at 37 °C for 6 h, the cells were washed three times in PBS to remove any non-adherent cells. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Alpha Aesar) to preserve cellular structure. To visualize the cell nuclei, the cells were stained with Hoechst 33,342 (Thermo Scientific). Random images of each well were taken with the Operetta CLS High Content Screening Microscope (Perkin-Elmer), and the Harmony High-Content Imaging and Analysis Software (Perkin-Elmer) was used to evaluate the number of cells attached to each condition.

Static permeability assay

Static permeability was evaluated as previously described [24]. Briefly, 8 × 104 podocytes were seeded onto the upper surface of a 12-well insert with a 3 μm pore size (Falcon), which had been pre-coated with collagen IV (Sigma) for cell adherence. The inserts were placed in a 12-well plate (Falcon), and the cells were cultured to achieve differentiation. Permeability was evaluated by adding 1 mg/ml FITC-labeled BSA (Sigma) dissolved in phenol red-free medium to the bottom well, beneath the insert containing the differentiated podocytes. The plate was incubated for 3 h at 37 °C to allow for diffusion through the cell monolayer. After incubation, the fluorescence of the medium in the lower chamber was measured using a spectrophotometer (Glomax), with excitation and emission settings at 475 nm and 500–550 nm, respectively.

Dynamic permeability assay

Dynamic permeability was evaluated using a Millifluidic system (IVTech Srl) consisting of two parallel circuits that simulate glomerular perfusion, as previously described [24]. Differentiated podocytes (8 × 104 per bioreactor) were seeded onto a collagen IV-coated polyethylene terephthalate membrane (0.45 µm pore size; ipCELLCULTURE™). After 24 h, the bioreactor was connected to the Millifluidic system with a flow rate set to 80 μl/min. Permeability was assessed by introducing FITC-BSA into the lower compartment of the chamber. After 3 h of continuous perfusion, samples from the upper chamber were collected to measure the transmembrane passage of FITC-BSA. Fluorescence intensity was determined as described in the Static Permeability Assay section.

Zebrafish maintenance and compounds

Zebrafish were handled and maintained in compliance with KU Leuven animal welfare regulations as previously described [25]. Details regarding the generation of the cystinosis ctns−/− and ctns+/+[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)] zebrafish lines have been described in previous studies [26, 27]. Cysteamine (100 µM, Sigma), MitoTEMPO (10 µM, Sigma), and liproxstatin-1 (10 µM, Selleckchem) were prepared in Danieau’s solution without methylene blue. Compounds were administered starting at 48 h post-fertilization (hpf) and refreshed daily until the study endpoint at 120 hpf.

ctns−/−[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)] zebrafish larvae model

To generate the ctns−/−[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)] zebrafish line, which expresses vitamin D-binding protein tagged with EGFP for proteinuria detection, ctns−/− zebrafish were crossed with ctns+/+[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)]. Larvae from this cross were screened for EGFP expression, and body fluorescence was assessed at 120 hpf using a SteREO Discovery V8 microscope (Zeiss). EGFP-positive larvae were raised to adulthood, and ctns+/+[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)] individuals were separated from ctns−/−[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)] through genotyping of the ctns gene as previously described [26]. The presence of EGFP was confirmed via PCR, and cystine accumulation was measured to verify the effect of the cystinosin mutation. Mating and fertility studies followed established protocols [25], with hatched eggs evaluated at 72 hpf and assessments of deformity and mortality conducted at 120 hpf.

To measure DBP-EGFP fluorescence intensity in the liver, 120 hpf larvae were fixed overnight at 4 °C in 4% PFA (Alpha Aesar) in PBS, then washed in PBS (3 × 5 min) and incubated in 30% sucrose (Merck) overnight. The larvae were then embedded in cryosection molds (Electron Microscopy Sciences) using gelatin from cold water fish skin (Sigma) mixed with 15% sucrose, frozen on dry ice, and sectioned into 4 µm slices using an NX70 cryotome (Thermo Scientific). Sections were subsequently stained with Hoechst 33,342 (Thermo Scientific) and mounted with fluorescence mounting medium (DAKO). Liver fluorescence was imaged with an Eclipse CI microscope (Nikon), and fluorescence intensity was quantified and normalized to liver surface area using ImageJ software.

For compound toxicity assessment, non-dysmorphic larvae were exposed to the compounds from 48 hpf, with daily monitoring for mortality through 120 hpf.

Evaluation of the glomerular proteinuria in zebrafish larvae

Glomerular proteinuria was evaluated by monitoring fluorescence intensity in the zebrafish eye lens as previously established [28]. Briefly, at least 60 larvae (n ≥ 60) were immobilized in a 3% (w/v) methylcellulose mounting solution (Sigma) prepared in Danieau’s solution. Images of the lens were captured using a SteREO Discovery V8 stereomicroscope (Zeiss) equipped with a GFP filter and AxioCam MRc5 (Zeiss). ZEN blue software (Zeiss) was used to acquire the images. The fluorescence intensity of each lens was subsequently quantified using ImageJ software, with values normalized to the lens surface area.

Cystine measurements

Cystine levels in podocytes and zebrafish larvae (120 hpf; n = 20 per condition) were determined following previously established methods [26, 29]. Samples were prepared in a total volume of 200 μl containing 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM, Sigma) and 100 μl of 12% sulfosalicylic acid (SSA, Sigma). Measurements were normalized to protein concentrations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism for Windows (v. 10.2.2, GraphPad Software) and R (v. 4.4.2, R Project for Statistical Computing). The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Brown-Forsythe test, complemented by visual inspection of QQ-plots. Outliers were identified and excluded using the ROUT test (Q = 1%).

For comparisons between two groups, a two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction was applied to normally distributed data. For comparisons across more than two groups, one-way ANOVA was used for normally distributed data, followed by Dunnett’s or Šídák’s multiple comparisons tests, as appropriate. For non-normally distributed data, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied.

Western blot quantification was analyzed using a one-sample t-test, comparing the sample mean against a hypothetical mean of one. Fertility, deformity, and mortality data in zebrafish larvae were analyzed using the Chi-square test to assess significant differences in categorical outcomes between experimental groups. Survival data were analyzed using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test to compare survival curves and evaluate statistical differences in survival rates over time.

For experiments involving multiple technical replicates, a linear mixed model in R was used to account for intra-group variability and repeated measures. All other statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism. Graphs represent the combined data from at least three independent biological experiments. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. P-values are indicated on the graphs, with P-values less than 0.0001 reported as "P < 0.0001."

Results

Cystinosis podocytes display impaired mitochondrial metabolism and a fragmented mitochondrial network

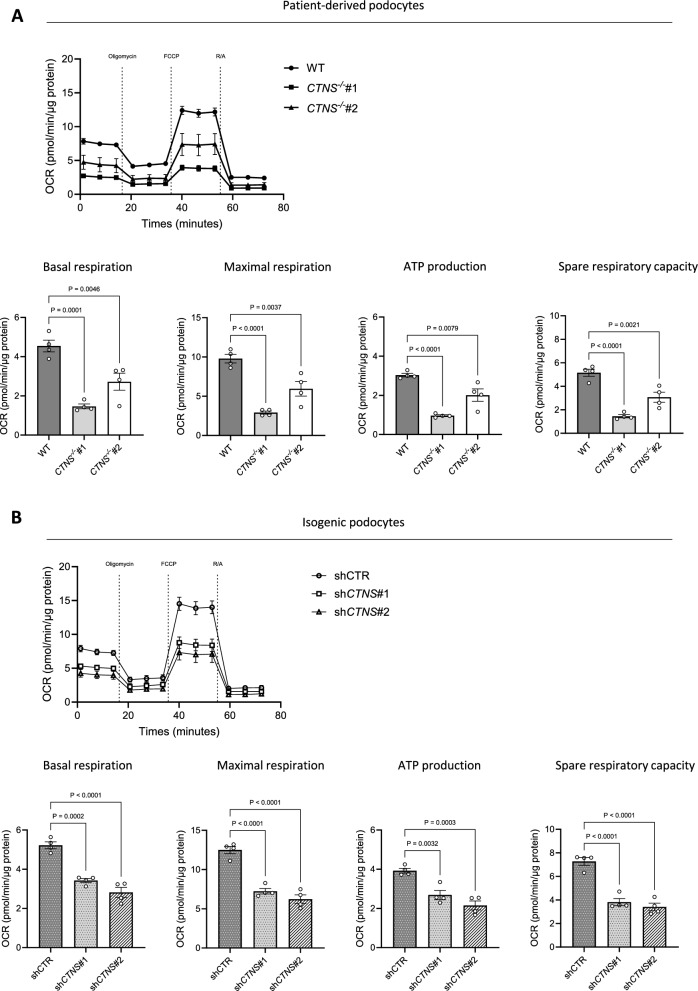

Intracellular cystine exists exclusively in non-reductive organelles, whereas under reductive conditions, such as in the cytosol, the monomeric cysteine form predominates. Cysteine has several cellular functions, ranging from antioxidant regulation to protein synthesis [30, 31]. To elucidate the mechanism of podocyte dysfunction in cystinosis, we initially tested how cystinosin deficiency affects intracellular metabolites in patient-derived CTNS−/− podocytes (CTNS−/−). In addition to increased cystine levels, we observed changes in intracellular amino acids, glycolysis intermediates, and TCA cycle metabolites compared with wild-type (WT) cells (Fig. 1a-b). Moreover, in the two patient cell lines studied, we observed a significant decrease in mitochondrial metabolites, specifically citrate, α-ketoglutarate, fumarate and malate (Fig. 1c). In addition, there was a decrease in the levels of the energy metabolites ATP, NAD, and NADH (Fig. 1d). Notably, cystinosis podocytes showed substantially decreased 13C6-glucose incorporation into TCA cycle metabolites, but not pyruvate or lactate (Additional file 1: Fig. S1A-B). While cysteamine successfully decreased cystine levels in cystinosis podocytes, it did not improve the alterations in TCA cycle or energy metabolites (Additional file 1: Fig. S1C-I). Moreover, patient-derived CTNS−/− podocytes displayed a fivefold increase in mitochondrial fragmentation compared with WT podocytes (Fig. 1e). To confirm that mitochondrial fragmentation was specifically caused by cystinosin deficiency and not by other patient-specific factors, we used short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to genetically silence the CTNS gene in WT podocytes, generating two isogenic cell lines, shCTNS#1 and shCTNS#2. In the control cell line (shCTR), the CTNS gene was not downregulated. In contrast, in the shCTNS lines, CTNS mRNA expression was specifically reduced (Additional file 1: Fig. S1J). In line, increased cystine levels were confirmed in the shCTNS lines (Additional file 1: Fig. S1K). As a result, we observed a twofold increase in mitochondrial fragmentation in the shCTNS lines compared with the shCTR control, mirroring the mitochondrial fragmentation seen in patient-derived cells (Fig. 1f). Since mitochondrial fragmentation often correlates with compromised mitochondrial function [32, 33], we further investigated mitochondrial function using the Seahorse MitoStress test in both patient-derived podocytes and isogenic cell lines. Our analysis revealed decreased basal and maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and reduced ATP production in both models compared to controls (Fig. 2a-b). Overall, this observation indicates that loss of cystinosin leads to mitochondrial dysfunction.

Fig. 2.

Cystinosis podocytes reveal decreased respiratory activity. Seahorse assay. (a, b) Upper panel: Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in a. WT, CTNS−/−#1, and CTNS−/−#2, and b. shCTR, shCTNS#1, and shCTNS#2 at baseline and following injection of oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone/antimycin A (R/A). Final concentrations: oligomycin (1.5 μM), FCCP (2 μM), rotenone (1.25 μM) and antimycin A (2.5 μM). Lower panel: quantification of basal respiration, maximal respiration, ATP production, and spare respiratory capacity in a. WT, CTNS−/−#1, and CTNS−/−#2, and b. shCTR, shCTNS#1, and shCTNS#2 (n = 4 biological experiments, n = 10 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s one-way ANOVA. For each experiment, values were normalized to protein levels. Each dot represents a biological experiment

Cystinosis podocytes show an altered mitochondrial glutathione redox state and elevated lipid peroxidation

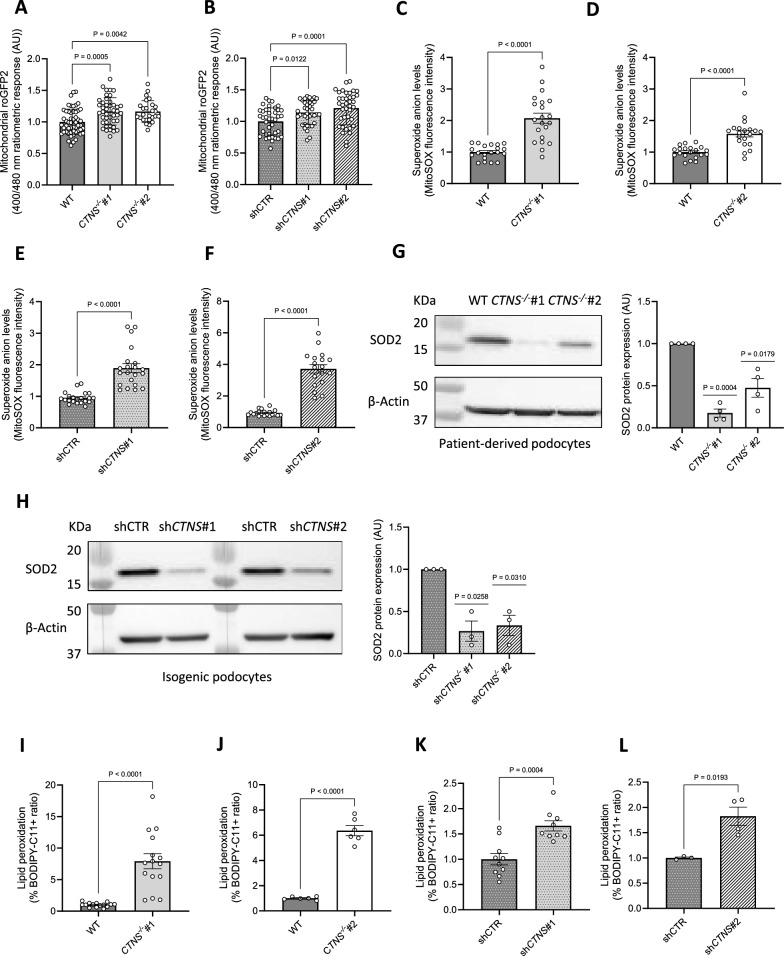

Mitochondrial dysfunction can compromise oxidative status [34]. To investigate whether the loss of cystinosin induces oxidative stress, we measured the glutathione redox potential in living cells transfected with roGFP2 redox sensors [21] and observed a shift toward an oxidative state specifically in mitochondria (Fig. 3a-b), but not in the cytosol or peroxisomes (Additional file 1: Fig. S2A-B). Furthermore, cysteamine treatment failed to alleviate mitochondrial oxidative stress (Additional file 1: Fig. S2C-D).

Fig. 3.

Cystinosis podocytes show an increased mitochondrial glutathione redox state and elevated lipid peroxidation. (a, b) In situ quantification of the mitochondrial glutathione redox potential in a. CTNS−/−#1 and CTNS−/−#2 normalized to WT podocytes, b. shCTNS#1 and shCTNS#2 normalized to shCTR. (n ≥ 4 biological experiments, where each dot represents the average ratio calculated from 10 measurements within a single cell). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s One-Way ANOVA. AU = arbitrary unit. (c, d, e, f) Superoxide anion levels measured using the mitochondrial superoxide indicator MitoSOX in c. CTNS−/−#1 normalized to WT podocytes and protein content, d. CTNS−/−#2 normalized to WT podocytes and protein content, e. shCTNS#1 normalized to shCTR and protein content, f. shCTNS#2 normalized to shCTR and protein content. (n = 3 biological experiments, n ≥ 5 technical replicates) Statistical analysis: linear mixed model. Each dot represents a technical replicate. (g, h) Left panel: Representative western blot image of Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2) in g. WT, CTNS−/−#1, and CTNS−/−#2, and h. shCTR, shCTNS#1, and shCTNS#2. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Right panel: Quantification of SOD2 protein expression relative to β-Actin. (n = 4 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate). Statistical analysis: one-sample t-test, with WT set as the reference. AU = arbitrary units. (i, j, k, l) Ratio of the percentages of BODIPY-C11 + cells measured by flow cytometry in i. CTNS−/−#1 normalized to WT, j. CTNS−/−#2 normalized to WT, k. shCTNS#1 normalized to shCTR, and l. shCTNS#2 normalized to shCTR. (n ≥ 4 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate). Statistical analysis: Welch’s unpaired t-test. Unless noted, each dot represents a biological experiment

Superoxide anions (O2•–) are the primary contributors of ROS in mitochondria [35–37]; therefore, we measured O2•– levels and found that cystinosis podocytes displayed increased O2•– (Fig. 3c–f) that were not reduced by cysteamine treatment (Additional file 1: Fig. S2E-G). Consistently, cystinosis podocytes showed decreased expression of the antioxidant enzyme SOD2 (Fig. 3g-h), the main O2•– scavenger in mitochondria [38, 39]. These findings indicate that cystinosin deficiency leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, increased O2•– levels, and reduced SOD2 expression.

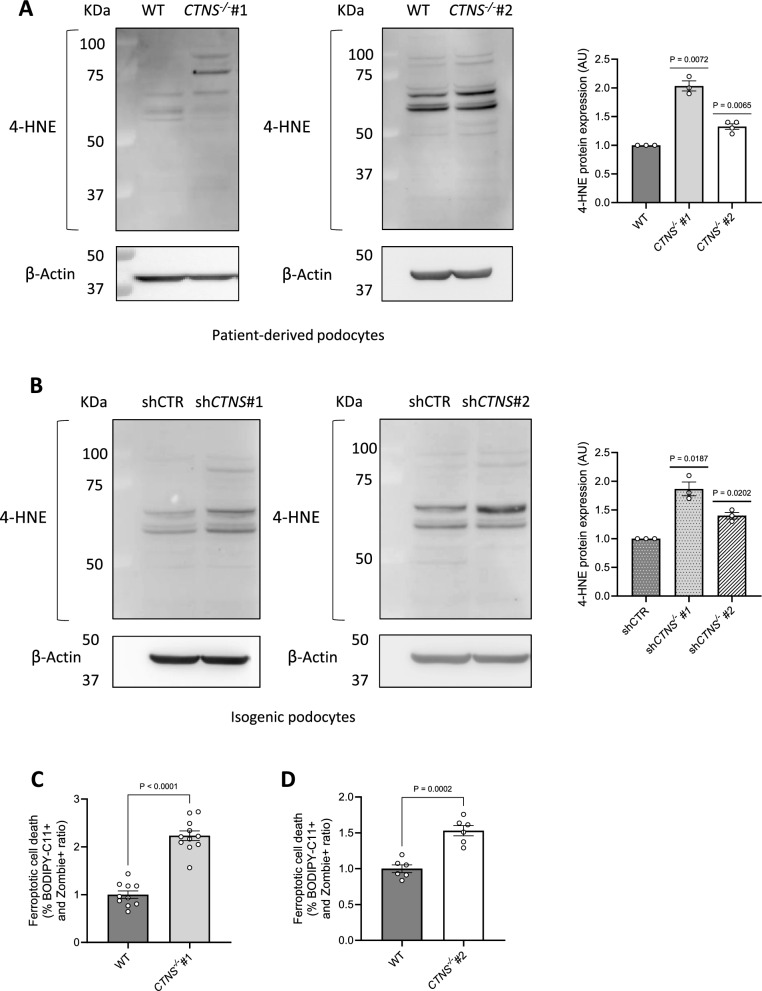

Elevated levels of O2•–, resulting from the depletion of compensatory mechanisms primarily mediated by superoxide dismutases, are known to trigger lipid peroxidation [40]. Lipid species present in the cell membranes can be affected by peroxidation, a process by which free radicals such as O2•–, oxidize lipid carbon–carbon double bond(s) [41, 42]. Quantification of oxidized membrane lipids revealed that cystinosis podocytes exhibit increased lipid peroxidation (Fig. 3i–l). This peroxidation generates lipid alkenyls, such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), which can interfere with cellular signaling by covalently binding to proteins, nucleic acids, and membrane lipids [43]. To investigate the consequences of enhanced lipid peroxidation, we assessed 4-HNE incorporation into cellular proteins and found increased levels of 4-HNE-protein adducts in cystinosis podocytes (Fig. 4a-b).

Fig. 4.

Cystinosis podocytes present increased 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) protein expression and ferroptotic cell death. (a, b) Representative western blot analysis of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE)-conjugated protein levels. a. Left panel: WT and CTNS−/−#1; central panel: WT and CTNS−/−#2, with β-Actin used as the loading control. Right panel: quantification of 4-HNE protein expression normalized to β-Actin. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate). Statistical analysis: one-sample t-test, with WT set as the reference. b. Left panel: shCTR and shCTNS#1; central panel: shCTR and shCTNS#2, with β-Actin used as loading control. Right panel: quantification of 4-HNE protein expression normalized to β-Actin. (n = 3 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate). Statistical analysis: one-sample t-test, with shCTR set as the reference. (c, d) Ratio of the percentages of BODIPY-C11 + cells among dead podocytes (Zombie) measured by flow cytometry. c. CTNS−/−#1 normalized to WT; d. CTNS−/−#2 normalized to WT. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate). Statistical analysis: Welch’s unpaired t-test Each dot represents a biological experiment

Excessive lipid peroxidation is a key driver of ferroptotic cell death [40]. Of note, we discovered increased ferroptosis in patient-derived CTNS−/− podocytes (Fig. 4c-d).

Targeting mitochondrial ROS or inhibiting lipid peroxidation improves cell adhesion and reduces podocyte monolayer permeability

Increased ROS originating from damaged mitochondria has been shown to impair cellular adhesion [44, 45]. As cystinosis patients present excessive podocyte loss into the urine and HMW proteinuria [8, 9], we evaluated cell adhesion (Additional file 1: Fig. S3A) and the permeability of the podocyte monolayer using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled bovine serum albumin (FITC-BSA) (Additional file 1: Fig. S3B) [24]. We confirmed that patient-derived CTNS−/− podocytes demonstrated decreased cell adhesion (Fig. 5a) and increased FITC-BSA permeability (Fig. 5b). Similar results were obtained in isogenic podocyte cell lines, which exhibited similar defects in adhesion and permeability (Fig. 5c-d).

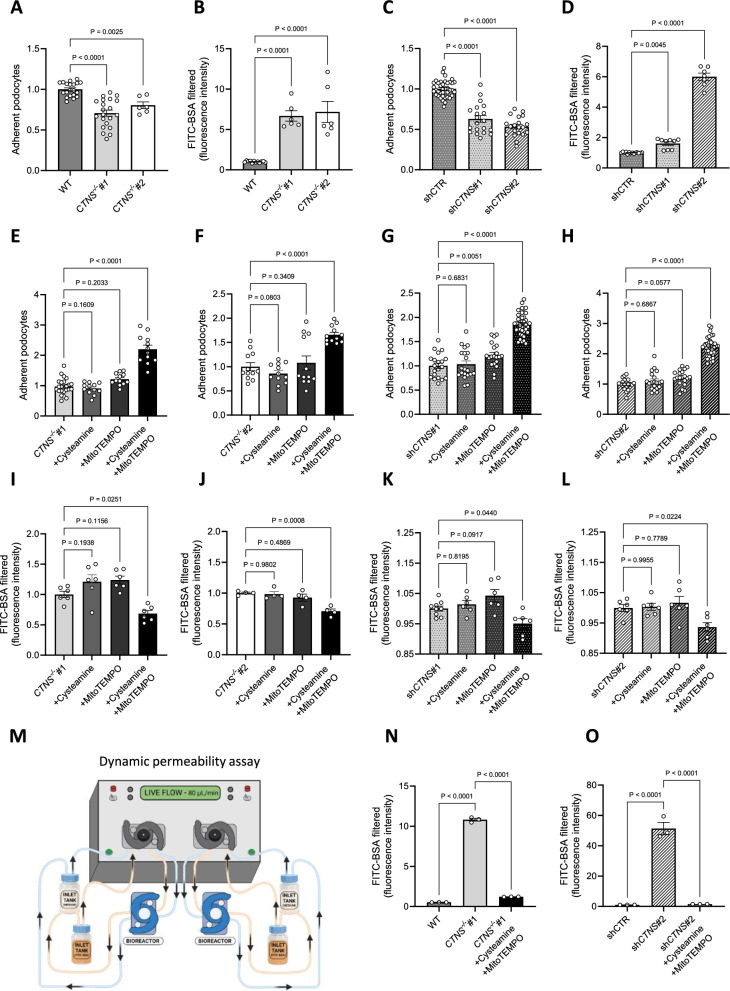

Fig. 5.

Targeting mitochondrial ROS improves cell adhesion and reduces podocyte permeability. (a) Adherence of CTNS−/−#1 and CTNS−/−#2, normalized to WT podocytes. Each dot represents the relative number of podocytes attached in one well. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n ≥ 3 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: linear mixed model. (b) Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled bovine serum albumin (FITC-BSA) fluorescence quantification in CTNS−/−#1 and CTNS−/−#2, normalized to WT. (n ≥ 6 biological experiments, n = 4 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s One-Way ANOVA. (c) Adherence of shCTNS#1 and shCTNS#2, normalized to shCTR. Each dot represents the relative number of podocytes attached in one well. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n ≥ 3 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: linear mixed model. (d) FITC-BSA fluorescence quantification in shCTNS#1 and shCTNS#2, normalized to shCTR. (n ≥ 7 biological experiments, n = 4 technical replicates. Statistical analysis: Dunn’s Kruskal–Wallis. (e, f, g, h) Adherence of cells incubated with 100 µM cysteamine, 10 µM MitoTEMPO, or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM MitoTEMPO for 48 h, normalized to e. CTNS−/−#1, f. CTNS−/−#2, g. shCTNS#1, and h. shCTNS#2. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n ≥ 3 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: linear mixed model. (I, j, k, l) FITC-BSA fluorescence quantification of cells incubated with 100 µM cysteamine, 10 µM MitoTEMPO, or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM MitoTEMPO for 48 h, normalized to i. CTNS−/−#1, j. CTNS−/−#2, k. shCTNS#1, and l. shCTNS#2. (n ≥ 4 biological experiments, n ≥ 3 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s One-Way ANOVA. (m) Millifluidic system to assess podocyte dynamic permeability. Podocytes were seeded in a bioreactor and perfused with media. The figure was created using biorender.com. (n, o) Quantification of FITC-BSA fluorescence intensity in the upper chamber medium after perfusion in n. WT, CTNS−/−#1 + 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM MitoTEMPO, and o. shCTR, shCTNS#2 + 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM MitoTEMPO for 48 h. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n = 4 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s One-Way ANOVA. Unless noted, each dot represents a biological experiment

Next, we investigated whether targeting mitochondrial oxidative stress could improve the cell adhesion and reduce permeability of cystinosis podocytes. While cysteamine treatment alone had no effect, co-treatment with the mitochondrial O2•– scavenger MitoTEMPO led to improved cell adhesion (Fig. 5e–h) and reduced podocyte layer permeability (Fig. 5i–l) [46], suggesting that mitochondrial oxidative damage causes podocyte loss in CTNS-deficient cells.

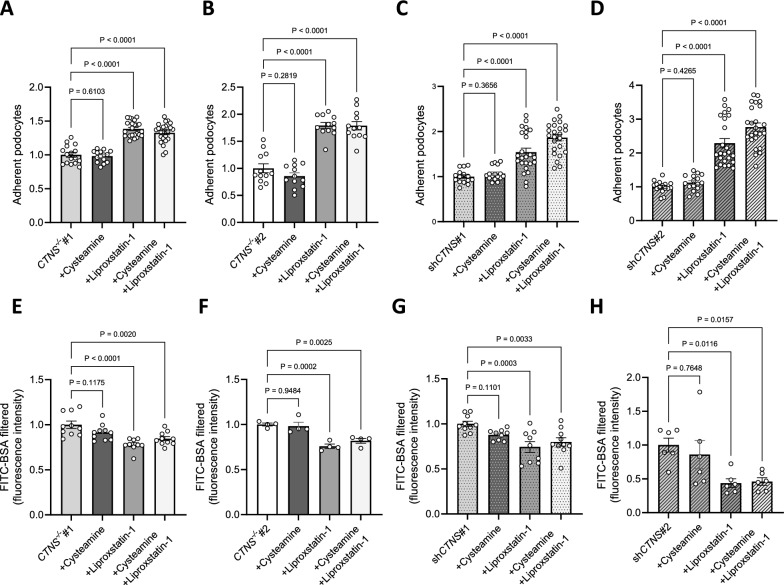

To validate these findings in a more physiological setting, we conducted a permeability assay under dynamic conditions using a Millifluidic system, which allows continuous perfusion of the cell monolayer under shear stress (Fig. 5m) [24]. In this system, cystinosis podocytes exhibited increased permeability, which was reduced with the combinatorial treatment using MitoTEMPO and cysteamine (Fig. 5n-o). Additionally, incubating cystinosis podocytes with the lipid peroxidation scavenger liproxstatin-1 improved cell adhesion (Fig. 6a–d) and reduced permeability (Fig. 6e–h) [47].

Fig. 6.

Inhibiting lipid peroxidation improves cell adhesion and reduces podocyte permeability. (a, b, c, d) Adherence of cells incubated with 100 µM cysteamine, 10 µM liproxstatin-1, or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM liproxstatin-1 for 48 h, normalized to a. CTNS−/−#1, b. CTNS−/−#2, c. shCTNS#1, and d. shCTNS#2. Each dot represents the relative number of podocytes attached in one well. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n ≥ 3 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: linear mixed model. (e, f, g, h) FITC-BSA fluorescence quantification of cells incubated with 100 µM cysteamine, 10 µM liproxstatin-1, or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM liproxstatin-1 for 48 h, normalized to e. CTNS−/−#1, f. CTNS−/−#2, g. shCTNS#1, and h. shCTNS#2. (n ≥ 4 biological experiments, n = 4 technical replicates). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s One-Way ANOVA. Unless noted, each dot represents a biological experiment

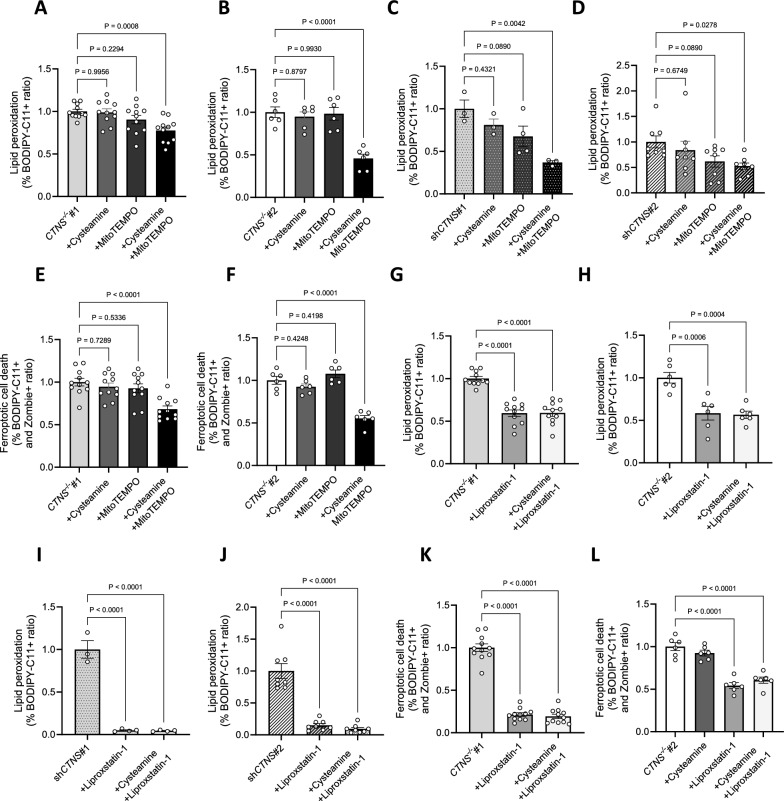

To determine causality, we investigated whether lipid peroxidation is driven by mitochondrial ROS. To address this hypothesis, we treated cystinosis podocytes with MitoTEMPO and cysteamine and measured lipid peroxidation levels. While cysteamine alone had no effect, we found that MitoTEMPO supplementation decreased lipid peroxidation (Fig. 7a–d), suggesting that lipid peroxidation in cystinosis podocytes is caused by mitochondrial ROS. Next, we evaluated whether the combinatorial treatment with cysteamine and MitoTEMPO or liproxstatin-1 alone could mitigate lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Our results showed that both treatments reduced these pathogenic processes (Fig. 7e–l). Finally, we evaluated whether reducing lipid peroxidation affected 4-HNE protein incorporation and found that treatment with MitoTEMPO in combination with cysteamine or liproxstatin-1 effectively decreased 4-HNE protein levels (Fig. 8a-b).

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial oxidative stress induces lipid peroxidation in cystinosis podocytes. (a, b, c, d) Ratio of the percentages of BODIPY-C11 + cells measured by flow cytometry incubated with 10 µM cysteamine, 10 µM MitoTEMPO, or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM MitoTEMPO for 48 h, normalized to a. CTNS−/−#1, b. CTNS−/−#2, c. shCTNS#1, and d. shCTNS#2. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s One-Way ANOVA. (e, f) Ratio of the percentages of BODIPY-C11 + cells among dead podocytes (Zombie) measured by flow cytometry incubated with 100 µM cysteamine, 10 µM MitoTEMPO, or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM MitoTEMPO for 48 h, normalized to e. CTNS−/−#1 and f. CTNS−/−#2. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s One-Way ANOVA. (g, h, i, j) Ratio of the percentages of BODIPY-C11 + cells measured by flow cytometry incubated with 10 µM liproxstatin-1 or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM liproxstatin-1 for 48 h, normalized to g. CTNS−/−#1, h. CTNS−/−#2, i. shCTNS#1, and j. shCTNS#2. Data for the CTNS−/−#1, CTNS−/−#2, shCTNS#1, and shCTNS#2 groups are the same as those in (A-D), respectively. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s One-Way ANOVA. (k, l) Ratio of the percentages of BODIPY-C11 + cells among dead podocytes (Zombie) measured by flow cytometry incubated with 10 µM liproxstatin-1 or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM liproxstatin-1 for 48 h, normalized to k. CTNS−/−#1 and l. CTNS−/−#2. Data for the CTNS−/−#1 and CTNS−/−#2 groups are the same as those in (e–f), respectively. (n ≥ 3 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate). Statistical analysis: Dunnett’s One-Way ANOVA. Each dot represents a biological experiment

Fig. 8.

Combinatorial treatment with cysteamine and MitoTEMPO or liproxstatin-1 decreases 4-HNE protein expression in cystinosis podocytes. (a, b) Left panel: Representative western blot image of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE)-conjugated protein levels in a. CTNS−/−#1 and b. CTNS−/−#2 treated with 100 µM cysteamine, 10 µM MitoTEMPO, 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM MitoTEMPO, 10 µM liproxstatin-1, or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM liproxstatin-1 for 48 h. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Right panel: Quantification of 4-HNE protein expression normalized to β-Actin. (n = 4 biological experiments, n = 1 technical replicate) Statistical analysis: one-sample t-test, with WT set as the reference. AU = arbitrary units. Each dot represents a biological experiment

Scavenging mitochondrial oxidative stress and inhibiting lipid peroxidation decreases proteinuria in DBP-EGFP cystinosis zebrafish larvae

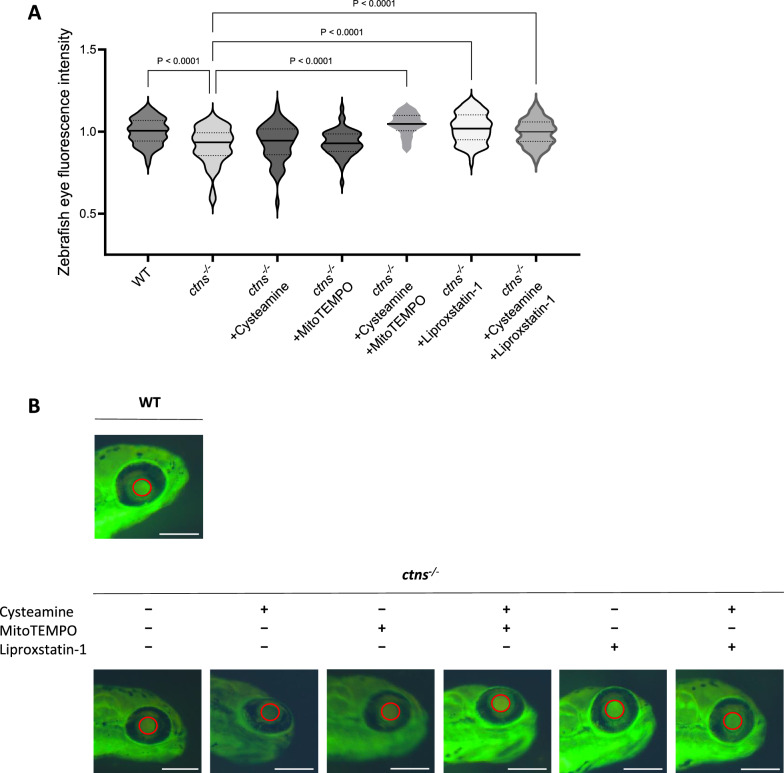

To validate our in vitro findings in vivo, we investigated whether targeting oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation could restore GFB functionality in a larval zebrafish model of cystinosis. To address this question, we developed a double transgenic cystinosis zebrafish ctns−/−[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)] (ctns−/−) by crossing the cystinosis zebrafish [26], with the ctns+/+[Tg(fabp10a:gc-EGFP)] (WT) zebrafish expressing the EGFP-tagged vitamin D binding protein (DBP-EGFP) for the detection of proteinuria [27]. First, we validated this new model and showed that the mutation in the ctns−/− gene induced cystine accumulation, increased the number of unfertilized eggs, decreased eggs hatching and increased deformity and mortality (Additional file 1: Fig. S4A–E). In the control fish line, DBP-EGFP is retained by healthy glomeruli, resulting in high levels of green fluorescence in the eyes [27, 28]. To assess glomerular function, we quantified the fluorescence intensity of DBP-EGFP in the eyes and found that it was significantly decreased in the ctns−/− DBP-EGFP zebrafish larvae (Fig. 9a-b). Importantly, the decrease in DBP-EGFP fluorescence was independent of hepatic DBP-EGFP production (Additional file 1: Fig. S4F).

Fig. 9.

Scavenging mitochondrial oxidative stress and inhibiting lipid peroxidation rescues proteinuria in DBP-EGFP cystinosis zebrafish larvae. a. Quantification of DBP-EGFP fluorescence intensity in the eyes of 120 h post-fertilization (hpf) zebrafish larvae. Data include WT (ctns+/+), ctns−/−, and ctns−/− larvae treated from 48 to 120 hpf with 100 µM cysteamine, 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM MitoTEMPO, 10 µM liproxstatin-1, or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM liproxstatin-1. n ≥ 60 zebrafish larvae per condition. Statistical analysis: Šídák's One-Way ANOVA. Fluorescence intensity is normalized to WT and presented as a violin plot. b. Representative images of 120 hpf zebrafish larvae eyes for WT, ctns−/−, and ctns−/− treated with 100 µM cysteamine, 10 µM MitoTEMPO, 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM MitoTEMPO, 10 µM liproxstatin-1, or 100 µM cysteamine + 10 µM liproxstatin-1. Red circles highlight areas where DBP-EGFP fluorescence intensity was measured. Scale bar: 250 µm

Subsequently, we treated ctns−/− zebrafish larvae with cysteamine alone, with a combination treatment cysteamine + MitoTEMPO, or with the lipid peroxidation inhibitor liproxstatin-1 [47], and confirmed that none of these compounds were toxic (Additional file 1: Fig. S4G). Strikingly, we discovered that scavenging mitochondrial ROS in combination with cysteamine or the sole treatment with liproxstatin-1 improved egg hatching (Additional file 1: Fig. S4H) and restored eye fluorescence of DBP-EGFP in the ctns−/− zebrafish larvae to the WT level (Fig. 9a-b), indicating a rescue of glomerular proteinuria.

Discussion

The mechanism of kidney disease in cystinosis has been most extensively studied in the proximal tubules, as this nephron segment is initially affected by the disease [48]. For instance, defective lysosomal cystine export has been shown to impair mTORC1 signaling, disrupt autophagy, and cause the accumulation of damaged mitochondria. Consequently, this leads to excessive mitochondrial ROS generation, resulting in tight junction disruption and dedifferentiation of PTEC, thereby contributing to the development of renal Fanconi syndrome in cystinosis [15, 49]. Kidney proximal tubules heavily depend on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to generate ATP for the basolateral sodium–potassium ATPase, which establishes the transmembrane sodium gradient necessary to drive the activity of numerous apical transporters [50].

Although glomerular podocytes and proximal tubules are close neighbors within the nephron, their metabolic processes differ significantly [51]. While earlier research showed that mitochondrial metabolism accounts for approximately 80% of cellular respiration in mouse podocytes [52], more recent data challenged this assumption, demonstrating that anaerobic glycolysis and fermentation of glucose to lactate are the key energy sources in these cells [53]. Nonetheless, upon stress, impaired mitochondrial respiration and increased ROS in podocytes are contributing factors in several pathological conditions [54, 55].

In the current study, we aimed to investigate energy metabolism in cystinosis podocytes and demonstrated that cystinosin deficiency rewires podocyte metabolism, impairing TCA cycle and increasing mitochondrial oxidative stress. Interestingly, we identified mitochondria-derived O2•– as the causative agent of lipid peroxidation, leading to podocyte detachment in cystinosis.

In this regard, our study adds cystinosis to the list of podocytopathies that present mitochondrial dysfunction.

Investigating podocytes in cystinosis has been hampered for a long time by the absence of suitable in vitro and in vivo models. While patients with cystinosis develop podocyte dysfunction starting from an early age [9], cystinosis rodent models only partially reproduce the glomerular phenotype [56–58]. In the present study, we used patient-derived CTNS−/− podocytes isolated from urine and isogenic shRNA podocytes. The latter allowed us to directly study the effects of cystinosin loss without the potential confounding factors that could arise from patient-specific genetic variability. Interestingly, although both patient-derived cell lines carried the same homozygous 57 kb deletion, which completely abolishes cystinosin expression, one cell line exhibited more severe impairments, reflecting the intra-patient variability.

Using the shRNA cell models we could validate our findings from the patient-derived cell lines. Despite the incomplete knockdown of CTNS mRNA, the metabolic alterations in shRNA-downregulated and patients’ derived cell lines were similar, suggesting that even partial cystinosin loss is sufficient to cause mitochondrial dysfunction, excessive ROS generation, and increased lipid peroxidation in podocytes.

Although our study did not uncover a mechanistic link between cystinosin loss and mitochondrial dysfunction in podocytes, it is plausible to speculate that mechanisms similar to those identified in cystinosis proximal tubules—such as impaired mitophagy leading to the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and excessive production of reactive oxygen species depleting cellular ant oxidative resources—might underlie the mitochondrial dysfunction observed in cystinosis podocytes.

An important goal of our study was to identify novel drug targets to mitigate podocyte dysfunction in cystinosis. This is particularly important, as the current standard-of-care treatment, cysteamine, which reduces cystine accumulation, neither improves glomerular dysfunction nor cures kidney failure [1, 9]. We showed that while cysteamine alone had no effect, adding the mitochondrial O2•–scavenger MitoTEMPO to cysteamine significantly improved ROS-induced lipid peroxidation and enhanced podocytes adherence. It remains unclear why cysteamine is insufficient to target ROS, as next to its cystine depleting action, the drug has been described as an antioxidant by increasing cysteine availability and therefore increasing the synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione [59]. We hypothesize that the failure of cysteamine to correct the deteriorative effects of ROS in cystinosis podocytes might be due to the hydrophilic nature of the molecule, which does not allow a direct action on the cell membranes (mitochondrial and cytoplasmic), which are lipid-enriched. Moreover, cysteamine may be insufficient to compensate for the absence of cystinosin, which plays a key role in supplying cysteine for cytosolic glutathione synthesis, a critical factor for the activity of the anti-ferroptotic enzyme glutathione peroxidase 4. [60]. In contrast, combinatorial treatment might have a dual effect on mitochondrial respiration. However, in cystinosis PTEC, cysteamine has been shown to improve mitochondrial function by increasing cAMP levels and enhancing complex I and V activity [14], pointing again to the differences in metabolism between podocytes and the proximal tubules.

In chronic kidney disease patients, MitoTEMPO has been shown to ameliorate microvascular function [61]. Its beneficial effects have been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo, where it improves mitochondrial function [62], reduces kidney damage and mitigates the loss of endothelial cells and podocytes in experimental diabetic nephropathy [63]. Additionally, MitoTEMPO has shown similar protective effects in models of cardiovascular damage, inflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases [62]. A related compound, MitoQ, has also been successfully tested in clinical trials, demonstrating benefits comparable to MitoTEMPO [62, 64, 65].

Remarkably, our study identified the lipid peroxide scavenger liproxstatin-1 as a potent agent for improving podocyte function, even without cysteamine supplementation. The high therapeutic potential of liproxstatin-1 may be attributed to its dual action as both a mitochondrial and plasma membrane antioxidant [66]. Importantly, previous studies have shown the efficacy of liproxstatin-1 and ferrostatin-1 as inhibitors of lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in experimental models of acute kidney injury, neurological diseases, cardiomyopathy, liver failure, and cancer [67]. Our data suggest that liproxstatin-1 or similar-acting compounds might be of broader interest in different podocyte diseases accompanied by increased oxidative stress such as nephrotic syndrome, diabetic nephropathy, or IgA nephropathy [54]. However, further studies are needed to fully understand the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of these compounds in rodents and humans to bring these compounds to the clinical applications [67].

While testing rodent models of cystinosis was beyond the scope of this study, we utilized a cystinosis zebrafish larval model to assess glomerular dysfunction [25, 26]. Importantly, zebrafish have been used by other investigators to study lipid peroxidation and the effects of potential treatments, underscoring the usefulness of this model for answering our research questions [68]. In order to evaluate potential treatments for restoring GFB function, we developed a double transgenic fluorescence zebrafish lacking cystinosin and expressing the DBP-EGFP for quantifying proteinuria. Indeed, cystinosis larvae showed proteinuria, highlighted by the 10% loss of eye fluorescence, which could be rescued by targeting mitochondrial ROS or lipid peroxidation. Ten percent decrease in eye fluorescence of the DBP-EGFP reflects the moderate degree of proteinuria observed in cystinosis patients, which occurs without a significant reduction in plasma protein levels (Additional file 2: Table S1). The restoration of proteinuria by novel drug compounds in cystinosis larvae validates our in vitro findings and provides a strong rationale for further testing of these compounds in rodent models of cystinosis and, ultimately, in human clinical trials.

Further studies using a rat model of cystinosis [69] will analyze the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of MitoTEMPO and liproxstatin-1. We will assess their effectiveness in alleviating kidney dysfunction (podocytes and proximal tubules), mitigating mitochondrial oxidative stress, and inhibiting lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in this advanced models. Furthermore, we will examine their safety profiles, including potential adverse effects and tolerability.

Conclusions

Collectively, our findings demonstrate that increased O2•– production, and subsequent lipid peroxidation, drive podocyte detachment and ferroptosis, which play a key role in podocyte injury in cystinosis. Targeting these mechanisms may offer a new therapeutic approach for treating nephropathic cystinosis.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge G. Doglioni, A. Cuadros, J.F. Garcia, J. Duarte, P.A. Manzano, G. Rinaldi and S.M. Fendt (VIB Laboratory of Cellular Metabolism and Metabolic Regulation, KU Leuven) for their valuable advice and expertise in the manuscript. We thank C.T. Cologna and S.D. Craemer (VIB Metabolomics Expertise Center & Core, KU Leuven) for their guidance and input regarding metabolic analysis. We thank J. Lamote (VIB FACS Core, KU Leuven) for providing advice and expertise for flow cytometry experiments and O.C. Adebayo (KU Leuven) for her support in the generation of shCTNS cell lines. In addition, we acknowledge I. Bongaers (Laboratory of Pediatric Nephrology) for her support in microscopy imaging; K. Lambaerts, F. Hendrickx and K. van Kelst for their assistance in the aquatic facility (KU Leuven), and M. Derweduwe and F. De Smet (Laboratory for Precision Cancer Medicine, KU Leuven) and the Bio Imaging Core (VIB, KU Leuven) for their support and assistance. We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Alessandra Tammaro (Laboratory of Pathology, Amsterdam UMC) for her invaluable input in developing this manuscript. We also thank Dr. Jesper Kers (Laboratory of Pathology, Amsterdam UMC) and Peiqi Sun (Laboratory of Pathology, Amsterdam UMC) for their contributions to statistical analyses and their overall input throughout the development of this work. Additionally, we extend our thanks to Marjolein Turkenburg and Lodewijk IJlst (Gastroenterology, Endocrinology, and Metabolism, Amsterdam UMC) for their support and contributions to the Seahorse experiments. We also acknowledge J. Heigwer and the European Joint Program Rare Disease Fellowship and the laboratory of B. Bussolati. Finally, we are grateful to BCCM/GeneCorner and the Hercules Foundation for providing the shCTNS plasmids.

Abbreviations

- 4-HNE

4-Hydroxynonenal

- BCCM

Belgian coordinated collections of microorganisms

- CTNS

Cystinosin

- DBP-EGFP

EGFP-tagged vitamin D binding protein

- FITC-BSA

Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled bovine serum albumin

- FSGS

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- GFB

Glomerular filtration barrier

- HBSS

Hank’s balanced salt solution

- HMW

High molecular weight

- hTERT

Human telomerase reverse transcriptase

- ITS

Insulin, transferrin, and selenium

- OCR

Oxygen consumption rate

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation

- PTEC

Proximal tubular epithelial cell

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- shRNA

Short hairpin RNA

- SOD2

Superoxide dismutase 2

- O2•–

Superoxide anions

- SV40T

Simian virus 40 large T antigen

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid cycle

- WT

Wild type

Author contributions

SPB, TB, ST, FS, and AF designed and performed experiments. CL, MF, BG, NE, FOA, BB, LvdH and EL provided intellectual support. SC and BMG provided support for the cystine measurements. SPB drafted the manuscript. EL and LvdH contributed to the manuscript writing. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

SPB received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under the EJP RD COFUND-EJP N° 825575. We thank FWO Vlaanderen for the support to TB (11A7823N), EL (18011120N) and the KU Leuven C1 Grant for EL and LvdH (C14/17/11). EL and LvdH are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Kidney Diseases (ERKNet).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the University-Hospitals Leuven (S54695). Zebrafish were handled and maintained in compliance with the KU Leuven animal welfare regulations with ethical approval n.142/2019.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tjessa Bondue, Sarah Tassinari, Lambertus van den Heuvel and Elena Levtchenko have authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Elmonem MA, Veys KR, Soliman NA, van Dyck M, van den Heuvel LP, Levtchenko E. Cystinosis: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David D, Princiero Berlingerio S, Elmonem MA, Oliveira Arcolino F, Soliman N, van den Heuvel B, et al. Molecular Basis of Cystinosis: Geographic Distribution, Functional Consequences of Mutations in the CTNS Gene, and Potential for Repair. Nephron. 2019;141(2):133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gahl WA, Thoene JG, Schneider JA. Cystinosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(2):111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jezegou A, Llinares E, Anne C, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, O’Regan S, Aupetit J, et al. Heptahelical protein PQLC2 is a lysosomal cationic amino acid exporter underlying the action of cysteamine in cystinosis therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(50):E3434–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markello TC, Bernardini IM, Gahl WA. Improved renal function in children with cystinosis treated with cysteamine. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(16):1157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gahl WA, Balog JZ, Kleta R. Nephropathic cystinosis in adults: natural history and effects of oral cysteamine therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(4):242–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brodin-Sartorius A, Tete MJ, Niaudet P, Antignac C, Guest G, Ottolenghi C, et al. Cysteamine therapy delays the progression of nephropathic cystinosis in late adolescents and adults. Kidney Int. 2012;81(2):179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilmer MJ, Christensen EI, van den Heuvel LP, Monnens LA, Levtchenko EN. Urinary protein excretion pattern and renal expression of megalin and cubilin in nephropathic cystinosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(6):893–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanova EA, Arcolino FO, Elmonem MA, Rastaldi MP, Giardino L, Cornelissen EM, et al. Cystinosin deficiency causes podocyte damage and loss associated with increased cell motility. Kidney Int. 2016;89(5):1037–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lusco MA, Najafian B, Alpers CE, Fogo AB. AJKD atlas of renal pathology: cystinosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(6):e23–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumner S, Weber LT. Nephropathic Cystinosis: Symptoms, Treatment, and Perspectives of a Systemic Disease. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broyer M, Niaudet P. Cystinosis. In: Saudubray J-M, van den Berghe G, Walter JH, editors. Inborn Metabolic Diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012. p. 617–24.

- 13.De Rasmo D, Signorile A, De Leo E, Polishchuk EV, Ferretta A, Raso R, et al. Mitochondrial dynamics of proximal tubular epithelial cells in nephropathic cystinosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;21(1):192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellomo F, Signorile A, Tamma G, Ranieri M, Emma F, De Rasmo D. Impact of atypical mitochondrial cyclic-AMP level in nephropathic cystinosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(18):3411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Festa BP, Chen Z, Berquez M, Debaix H, Tokonami N, Prange JA, et al. Impaired autophagy bridges lysosomal storage disease and epithelial dysfunction in the kidney. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilmer MJ, Kluijtmans LA, van der Velden TJ, Willems PH, Scheffer PG, Masereeuw R, et al. Cysteamine restores glutathione redox status in cultured cystinotic proximal tubular epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812(6):643–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sansanwal P, Yen B, Gahl WA, Ma Y, Ying L, Wong LJ, et al. Mitochondrial autophagy promotes cellular injury in nephropathic cystinosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(2):272–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saleem MA, O’Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, et al. A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(3):630–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivashchenko O, Van Veldhoven PP, Brees C, Ho YS, Terlecky SR, Fransen M. Intraperoxisomal redox balance in mammalian cells: oxidative stress and interorganellar cross-talk. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(9):1440–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramazani Y, Knops N, Berlingerio SP, Adebayo OC, Lismont C, Kuypers DJ, et al. Therapeutic concentrations of calcineurin inhibitors do not deregulate glutathione redox balance in human renal proximal tubule cells. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4): e0250996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lismont C, Walton PA, Fransen M. Quantitative Monitoring of Subcellular Redox Dynamics in Living Mammalian Cells Using RoGFP2-Based Probes. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1595:151–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valente AJ, Maddalena LA, Robb EL, Moradi F, Stuart JA. A simple ImageJ macro tool for analyzing mitochondrial network morphology in mammalian cell culture. Acta Histochem. 2017;119(3):315–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez AM, Kim A, Yang WS. Detection of Ferroptosis by BODIPY 581/591 C11. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2108:125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iampietro C, Bellucci L, Arcolino FO, Arigoni M, Alessandri L, Gomez Y, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of urine-derived podocytes from patients with Alport syndrome. J Pathol. 2020;252(1):88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berlingerio SP, He J, De Groef L, Taeter H, Norton T, Baatsen P, et al. Renal and Extra Renal Manifestations in Adult Zebrafish Model of Cystinosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elmonem MA, Khalil R, Khodaparast L, Khodaparast L, Arcolino FO, Morgan J, et al. Cystinosis (ctns) zebrafish mutant shows pronephric glomerular and tubular dysfunction. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou W, Hildebrandt F. Inducible podocyte injury and proteinuria in transgenic zebrafish. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(6):1039–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanke N, King BL, Vaske B, Haller H, Schiffer M. A Fluorescence-Based Assay for Proteinuria Screening in Larval Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Zebrafish. 2015;12(5):372–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veys K, Berlingerio SP, David D, Bondue T, Held K, Reda A, et al. Urine-Derived Kidney Progenitor Cells in Cystinosis. Cells. 2022;11(7):1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serpa J. Cysteine as a Carbon Source, a Hot Spot in Cancer Cells Survival. Front Oncol. 2020;10:947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levtchenko E, de Graaf-Hess A, Wilmer M, van den Heuvel L, Monnens L, Blom H. Altered status of glutathione and its metabolites in cystinotic cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(9):1828–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen W, Zhao H, Li Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah SI, Paine JG, Perez C, Ullah G. Mitochondrial fragmentation and network architecture in degenerative diseases. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9): e0223014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhatti JS, Bhatti GK, Reddy PH. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in metabolic disorders—a step towards mitochondria based therapeutic strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863(5):1066–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tirichen H, Yaigoub H, Xu W, Wu C, Li R, Li Y. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and their contribution in chronic kidney disease progression through oxidative stress. Front Physiol. 2021;12: 627837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol Rev. 2014;94(3):909–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brand MD, Affourtit C, Esteves TC, Green K, Lambert AJ, Miwa S, et al. Mitochondrial superoxide: production, biological effects, and activation of uncoupling proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37(6):755–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melov S, Coskun P, Patel M, Tuinstra R, Cottrell B, Jun AS, et al. Mitochondrial disease in superoxide dismutase 2 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(3):846–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitada M, Xu J, Ogura Y, Monno I, Koya D. Manganese superoxide dismutase dysfunction and the pathogenesis of kidney disease. Front Physiol. 2020;11:755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao N, et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(2):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ayala A, Munoz MF, Arguelles S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014: 360438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaschler MM, Stockwell BR. Lipid peroxidation in cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;482(3):419–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhong H, Yin H. Role of lipid peroxidation derived 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) in cancer: focusing on mitochondria. Redox Biol. 2015;4:193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiarugi P. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of cell adhesion. Ital J Biochem. 2003;52(1):28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koo MA, Lee MH, Park JC. Recent Advances in ROS-Responsive Cell Sheet Techniques for Tissue Engineering. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trnka J, Blaikie FH, Smith RA, Murphy MP. A mitochondria-targeted nitroxide is reduced to its hydroxylamine by ubiquinol in mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44(7):1406–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zilka O, Shah R, Li B, Friedmann Angeli JP, Griesser M, Conrad M, et al. On the Mechanism of Cytoprotection by Ferrostatin-1 and Liproxstatin-1 and the Role of Lipid Peroxidation in Ferroptotic Cell Death. ACS Cent Sci. 2017;3(3):232–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamalpoor A, Othman A, Levtchenko EN, Masereeuw R, Janssen MJ. Molecular Mechanisms and Treatment Options of Nephropathic Cystinosis. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27:673–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berquez M, Chen Z, Festa BP, Krohn P, Keller SA, Parolo S, et al. Lysosomal cystine export regulates mTORC1 signaling to guide kidney epithelial cell fate specialization. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoogstraten CA, Hoenderop JG, de Baaij JHF. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Kidney Tubulopathies. Annual Review of Physiology. 2024;86(Volume 86, 2024):379–403. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Gujarati NA, Vasquez JM, Bogenhagen DF, Mallipattu SK. The complicated role of mitochondria in the podocyte. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2020;319(6):F955–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abe Y, Sakairi T, Kajiyama H, Shrivastav S, Beeson C, Kopp JB. Bioenergetic characterization of mouse podocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299(2):C464–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brinkkoetter PT, Bork T, Salou S, Liang W, Mizi A, Ozel C, et al. Anaerobic Glycolysis Maintains the Glomerular Filtration Barrier Independent of Mitochondrial Metabolism and Dynamics. Cell Rep. 2019;27(5):1551-66 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu YT, Wan C, Lin JH, Hammes HP, Zhang C. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress and Cell Death in Podocytopathies. Biomolecules. 2022;12(3):403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ge M, Fontanesi F, Merscher S, Fornoni A. The Vicious Cycle of Renal Lipotoxicity and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Front Physiol. 2020;11:732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimizu Y, Yanobu-Takanashi R, Nakano K, Hamase K, Shimizu T, Okamura T. A deletion in the Ctns gene causes renal tubular dysfunction and cystine accumulation in LEA/Tohm rats. Mamm Genome. 2019;30(1–2):23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nevo N, Chol M, Bailleux A, Kalatzis V, Morisset L, Devuyst O, et al. Renal phenotype of the cystinosis mouse model is dependent upon genetic background. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(4):1059–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krohn P, Rega LR, Harvent M, Festa BP, Taranta A, Luciani A, et al. Multisystem involvement, defective lysosomes and impaired autophagy in a novel rat model of nephropathic cystinosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2022;31(13):2262–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Besouw M, Masereeuw R, van den Heuvel L, Levtchenko E. Cysteamine: an old drug with new potential. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18(15–16):785–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Armenta DA, Laqtom NN, Alchemy G, Dong W, Morrow D, Poltorack CD, et al. Ferroptosis inhibition by lysosome-dependent catabolism of extracellular protein. Cell Chem Biol. 2022;29(11):1588-600.e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kirkman DL, Muth BJ, Ramick MG, Townsend RR, Edwards DG. Role of mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species in microvascular dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018;314(3):F423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pedraza-Chaverri APJ-UaJ. Promising Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Mitochondria in Kidney Diseases: From Small Molecules to Whole Mitochondria. Future Pharmacology. 2022.

- 63.Qi H, Casalena G, Shi S, Yu L, Ebefors K, Sun Y, et al. Glomerular Endothelial Mitochondrial Dysfunction Is Essential and Characteristic of Diabetic Kidney Disease Susceptibility. Diabetes. 2017;66(3):763–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rossman MJ, Santos-Parker JR, Steward CAC, Bispham NZ, Cuevas LM, Rosenberg HL, et al. Chronic Supplementation With a Mitochondrial Antioxidant (MitoQ) Improves Vascular Function in Healthy Older Adults. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1056–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gane EJ, Weilert F, Orr DW, Keogh GF, Gibson M, Lockhart MM, et al. The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant mitoquinone decreases liver damage in a phase II study of hepatitis C patients. Liver Int. 2010;30(7):1019–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oh SJ, Ikeda M, Ide T, Hur KY, Lee MS. Mitochondrial event as an ultimate step in ferroptosis. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.von Samson-Himmelstjerna FA, Kolbrink B, Riebeling T, Kunzendorf U, Krautwald S. Progress and Setbacks in Translating a Decade of Ferroptosis Research into Clinical Practice. Cells. 2022;11(14):2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao M, Hu J, Zhu Y, Wang X, Zeng S, Hong Y, et al. Ferroptosis and Apoptosis Are Involved in the Formation of L-Selenomethionine-Induced Ocular Defects in Zebrafish Embryos. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hollywood JA, Kallingappa PK, Cheung PY, Martis RM, Sreebhavan S, Atiola RD, et al. Cystinosin-deficient rats recapitulate the phenotype of nephropathic cystinosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2022;323(2):F156–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.