Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progresses as a continuum, from preclinical stages to late-stage cognitive decline, yet the molecular mechanisms driving this progression remain poorly understood. Here, we provide a systems-level map of protein-protein interaction (PPI) network dysfunction across the AD spectrum and uncover epichaperomes—stable scaffolding platforms formed by chaperones and co-factors—as central drivers of this process. Using over 100 human brain specimens, mouse models, and human neurons, we show that epichaperomes emerge early, even in preclinical AD, and progressively disrupt multiple PPI networks critical for synaptic function and neuroplasticity. Glutamatergic neurons, essential for learning and memory, exhibit heightened vulnerability, with their dysfunction driven by protein sequestration into epichaperome scaffolds, independent of changes in protein expression. Notably, pharmacological disruption of epichaperomes with PU-AD restores PPI network integrity and reverses synaptic and cognitive deficits, directly linking epichaperome-driven network dysfunction to AD pathology. These findings establish epichaperomes as key mediators of molecular collapse in AD and identify network-centric intervention strategies as a promising avenue for disease-modifying therapies.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a highly complex and currently untreatable neurodegenerative disorder that unfolds over decades, leading to progressive cognitive decline, primarily affecting memory and executive functions1. AD is now recognized as a disease continuum, spanning from preclinical to symptomatic stages, rather than a condition with a discrete onset. Pathophysiological changes begin years before clinical symptoms emerge, in a stage known as preclinical AD2,3. This recognition has reframed the study of AD, emphasizing the need to understand the molecular mechanisms driving disease progression across its full spectrum4.

Advances in genetics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics—coupled with sophisticated neuroimaging—have provided critical insights into AD pathology, revealing widespread molecular and cellular dysregulation and large-scale remodeling of brain networks5–11. Yet, despite these breakthroughs, a fundamental gap remains: What drives the progressive molecular collapse of brain networks, and how does this dysfunction evolve over time? Current models, which primarily focus on protein aggregation, amyloid plaques, and tau tangles, fail to fully explain the early molecular events that disrupt cellular networks, ultimately leading to cognitive decline.

To answer these questions, we must look beyond individual disease hallmarks and investigate how protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks are dysregulated in AD. PPIs govern nearly every cellular process12–14, and their perturbation is thought to drive key aspects of AD pathology15,16. However, mapping these dynamic alterations has remained a major challenge due to the sheer complexity of the interactome and the transient nature of many PPIs17. Existing technologies often fail to capture the evolving network dysfunctions in AD, particularly at early disease stages, limiting our ability to identify upstream molecular drivers of neurodegeneration. Addressing this challenge is critical for both understanding AD pathogenesis and identifying therapeutic interventions that can halt or reverse disease progression before irreversible damage occurs.

A systems-level approach is required—one that captures not just static molecular changes but also the dynamic, network-wide reorganization of protein interactions occurring throughout AD. The discovery of epichaperomes, stable disease-associated hetero-oligomeric assemblies of tightly bound chaperones and co-chaperones, offers a crucial breakthrough in this regard18. These pathological scaffolding platforms, which emerge specifically under disease conditions19–23, actively remodel PPI networks, hijacking cellular pathways that are critical for neuronal function20,24,25. By rewiring these networks, epichaperomes drive widespread cellular dysfunction and contribute to the progression of neurodegenerative processes20,24,25.

Leveraging this framework, we applied a novel approach to systematically map epichaperome-driven PPI network dysregulation across the AD spectrum. Using a comprehensive collection of over 100 postmortem human brain specimens, combined with experimental validation in AD mouse models and human neurons, we integrated epichaperome biology with our dysfunctional Protein-Protein Interactome (dfPPI) analysis platform26 to define how PPI networks are progressively disrupted across AD stages. This approach enables a level of molecular resolution previously unattainable, allowing us to track the evolution of network dysfunction from early preclinical phases to late-stage disease.

Our study provides an unprecedented systems-level map of progressive network dysfunction across the AD continuum, revealing how key cellular pathways are disrupted from early preclinical stages to advanced disease. By integrating epichaperome biology with dfPPI analysis, we uncover a trajectory of molecular dysfunction that begins with the selective vulnerability of glutamatergic neurons and expands to affect broader neuronal circuits and cellular processes over time. Early disruptions are centered on pathways critical for synaptic plasticity and excitatory neurotransmission, including transmission across chemical synapses, glutamatergic synapse signaling, actin remodeling, and long-term potentiation—deficits that manifest well before overt cognitive symptoms emerge. These early perturbations coincide with neuroinflammatory activation and dysregulation of translation initiation and phospholipid metabolism, suggesting a multifaceted molecular cascade that progressively undermines neuronal function. As AD advances, additional network dysfunctions emerge, including impairments in autophagy, iron metabolism, endocytosis, and intracellular trafficking, further exacerbating disease pathology.

Our findings establish epichaperomes as key drivers of these progressive network disruptions. By acting as pathological scaffolding platforms, epichaperomes dynamically rewire protein interactions, leading to maladaptive sequestration of proteins critical for learning and memory, such as Synapsin 1. Notably, the early and selective vulnerability of glutamatergic neurons to epichaperome-driven dysfunction provides a molecular framework for understanding why these neurons are among the first to be affected in AD.

Crucially, we demonstrate that these widespread dysfunctions are not only detectable and mappable but also reversible. Pharmacological disruption of epichaperomes restores PPI network integrity, synaptic function, and cognitive performance in both human neuronal models and APP NL-F mouse models, even at later disease stages. These results challenge the notion that AD-associated dysfunction is irreversible and position network-targeting interventions as a viable therapeutic approach for halting or even reversing cognitive decline.

By systematically dissecting the evolving molecular architecture of AD, this study highlights the central role of network dysfunction in disease pathogenesis and establishes epichaperomes as both a mechanistic driver and an actionable therapeutic target. These findings pave the way for precision medicine strategies aimed at preventing, delaying, or reversing AD-related network dysfunction before irreversible neurodegeneration occurs.

Results

Epichaperomes across the AD spectrum

To determine when epichaperomes form along the AD continuum, we initially focused on detecting epichaperomes in the frontal cortex {Brodmann area 9 (BA9)} of postmortem brain specimens from individuals at various stages of cognitive impairment, ranging from non-cognitively impaired aged individuals (NCI) through those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD dementia. To ensure the robustness and generalizability of our findings, we analyzed samples across multiple patient cohorts (Fig. 1a), incorporating a diverse range of genetic backgrounds, environmental exposures, and clinical manifestations. This approach provided a comprehensive view of epichaperome formation across the AD spectrum, including stages preceding the onset of AD. Details on human postmortem brain specimens and associated variables are found in Supplementary Data 1, which contains de-identified patient sample IDs along with assigned variables, including sex, postmortem interval (PMI), age, and clinical covariates such as pathology scores, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and Braak stage.

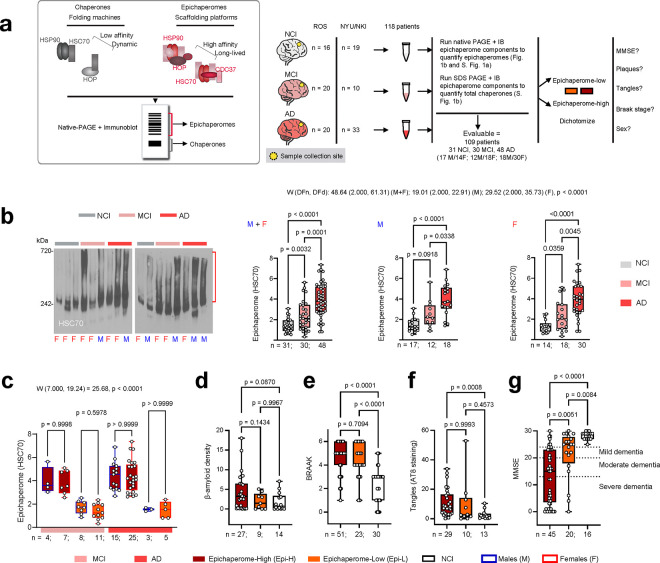

Figure 1. Epichaperome formation emerges early in disease, persists across the AD continuum, and correlates with worse cognitive scores.

a Experimental design. The cartoon depicts the biochemical distinction between epichaperomes (oligomeric high-molecular weight assemblies with chaperones and co-chaperones nucleating on HSP90 and HSC70) and chaperones (smaller, dynamic assemblies). Due to this distinction, epichaperomes are separated using native PAGE, followed by visualization by immunoblotting with antibodies against epichaperome constituent chaperones (e.g., HSC70). Post-mortem frontal cortex samples from human brains spanning non-cognitively impaired (NCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) stages were assessed for epichaperome content. Patients were then categorized into epichaperome-high and epichaperome-low groups, and their Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Braak stage, tangles, amyloid, and sex were compared across these groups. All data are plotted using a min-to-max box-and-whisker plot, with individual data points representing all values in the dataset. The box indicates the interquartile range, and the line within the box marks the median. Data were analyzed using Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA with Dunnett’s T3 post-hoc test. b Epichaperome levels as in a, evaluated in NCI, MCI, and AD groups, with data shown for males (M) and females (F) combined, as well as separated by sex. Gel, representative patients profiles of the n = 108 evaluable samples. c Epichaperome levels as in a in MCI and AD patients divided into low- and high-epichaperome groups, with further separation by sex (male: M, female: F). d-g Amyloid (β-amyloid density), W (2.000, 26.69) = 2.720, p = 0.0841 (d), Braak score, W (2.000, 51.30) = 27.70, p < 0.0001 (e), tangles (AT8 staining), W (2.000, 19.95) = 8.456, p = 0.0022 (f), and MMSE scores, W (2.000, 37.31) = 53.22, p < 0.0001 (g), in epichaperome-high (MCI+AD), epichaperome-low (MCI+AD), and NCI groups. Graphs present individual values for each patient in these categories. Source data are provided as Source Data file.

Our analysis included 118 patients from two distinct cohorts: the Rush Religious Orders Study (ROS) cohort27 (NCI: n=16, 6M/10F, age: 86.1 ± 3.8 years, PMI: 15 ± 8 h; MCI: n=20, 8M/12F, age: 90.3 ± 4.6 years, PMI: 10 ± 6 h; AD: n=20, 7M/13F, age: 90.4 ± 3.4 years, PMI: 11±7 h) and the NYUGSOM/NKI cohort (NCI: n=19, 12M/7F; age: 71.4 ± 17.7 years, PMI: 13 ± 8 h; MCI: n=10, 4M/6F; age: 85.6 ± 5.0 years, PMI: 13 ± 10 h; AD: n=33, 11M/22F; age: 79.0 ± 9.9 years, PMI: 11 ± 5 h). This multi-cohort approach allowed for a thorough understanding of epichaperome dynamics in a vulnerable brain region across various stages and populations of AD.

Epichaperomes, characterized by stable, high-molecular-weight assemblies, are distinct from transient chaperone complexes and can be differentiated using native PAGE separation20,22,23. Therefore, to detect and quantify epichaperomes, we employed a validated biochemical method that combines native PAGE with immunoblotting, targeting specific components of epichaperomes such as heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), heat shock cognate protein 70 (HSC70), Hsp70-Hsp90 organising protein (HOP; aka STIP1), and HSP90 co-chaperone cell division cycle 37 (CDC37) (Fig. 1a). We found that while chaperone complexes were consistently present in both normal and diseased brains, epichaperomes were predominantly associated with AD pathology and were detected in the frontal cortex of both MCI and AD patients (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1a).

We observed that epichaperome levels were significantly elevated as early as the MCI stage (p = 0.0032) and escalated further in AD (NCI to AD, p < 0.0001; MCI to AD, p = 0.0001), a trend consistent across both female and male patients (Fig. 1b). Notably, this increase occurred despite minimal changes in the overall concentration of chaperones across NCI, MCI, and AD groups (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b), reinforcing that epichaperome formation is independent of total chaperone protein levels, as reported21–23,28,29.

To understand whether differing epichaperome levels correspond to distinct pathological and clinical features, we dichotomized MCI and AD patients into epichaperome-high (Epi-H) and epichaperome-low (Epi-L) groups. The threshold was calculated based on the mean epichaperome levels in the NCI group plus 2 standard deviations, classifying 65.4% of patients as Epi-H and 34.6% as Epi-L (Supplementary Data 1). This stratification allowed us to assess whether epichaperome formation associates with specific pathological markers or cognitive decline across the AD spectrum.

We found no significant difference in the distribution of males and females between the Epi-H and Epi-L cohorts, confirming that sex does not influence epichaperome levels (Fig. 1c). We next analyzed whether there was a relationship between epichaperome levels and β-amyloid density (via 4G8, 6F/3D, and 10D immunostaining), Braak stage (tau pathology), phosphorylated tau (via AT8 staining), and MMSE scores (cognitive function)30,31 (Fig. 1d–g).

Regarding pathology, our analysis revealed that the Epi-H cohort predominantly included patients with the highest β-amyloid positivity, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (Epi-H vs Epi-L, p = 0.1434; Epi-H vs NCI, p = 0.0870; Fig. 1d). Additionally, we observed significant differences in tau pathology between both the Epi-H and Epi-L groups compared to NCI individuals, as reflected in Braak staging and AT8 levels (Fig. 1e,f, p < 0.0001 for Braak stage in Epi-H vs NCI and Epi-L vs NCI; p = 0.0008 for AT8 in Epi-H vs NCI). However, there was no difference in tau pathology between the Epi-H and Epi-L groups themselves (p = 0.7094 for Braak stage and p = 0.9993 for AT8). Overall, these results imply that epichaperomes may play a significant role in AD independently of direct involvement with amyloid plaques or tau pathology.

On the cognitive front, we found that the higher the epichaperome levels, the more pronounced the cognitive decline (Fig. 1g). Both Epi-H and Epi-L AD and MCI patients exhibited significantly greater impairment than NCI individuals (p = 0.0084 for NCI vs. Epi-L and p < 0.0001 for NCI vs. Epi-H), with Epi-H samples showing significantly greater impairment (lower MMSE scores) than Epi-L samples (p = 0.0051 for Epi-H vs. Epi-L), highlighting a clear link between epichaperome levels and cognitive impairment, with epichaperome formation potentially initiating cognitive decline and driving worsening dysfunction as the disease progresses through the AD continuum.

These results establish that epichaperomes emerge early in AD and increase with disease progression, paralleling cognitive decline. Their presence in the majority of MCI and AD patients suggests they contribute to disease pathogenesis. To determine how epichaperomes drive dysfunction, we next examined their impact on cellular pathways and PPI networks across the AD spectrum.

Networks dysregulated by epichaperomes across the AD spectrum

To this end, we applied a chemoproteomic method, dysfunctional Protein-Protein Interactome (dfPPI)26, to human postmortem brain specimens from the NYUGSOM/NKI cohort {NCI, n = 19; MCI, n = 10; AD, n = 33; and Parkinson’s disease (PD) n = 18} (Fig. 2a). PD samples were included to serve as a comparative disease control, given that epichaperomes also form in PD32 but likely dysregulate different cellular processes compared to AD, allowing for the assessment of disease-specific epichaperome-mediated network disruptions.

Figure 2. Networks dysregulated by epichaperomes across the AD continuum.

a Schematic of the experimental design. The diagram illustrates the application of the dysfunctional Protein-Protein Interactome (dfPPI) method to analyze human brain specimens from NYU/NKI cohort including NCI, MCI, and AD, as well as PD samples for comparative control. This panel outlines the chemoproteomic approach used to identify and map the proteins and networks dysregulated by epichaperomes. b Reactome mapping of dfPPI results. This panel visualizes the pathways that are differentially enriched or disrupted across the AD continuum, with specific comparisons such as MCI vs. AD, AD vs. NCI and MCI vs. AD highlighted to show distinct shifts in protein enrichment and pathway engagement. c Map of dysregulated processes across the AD continuum displays the functional alterations driven by epichaperomes from early stages to late-stage disease. Each row represents a pathway, with major processes selected for representation to manage the complexity of the data. Refer to Supplementary Data 2 for complete datasets and analytics.

dfPPI is a powerful interactomic method that uncovers the dynamics of PPIs within the context of epichaperome-mediated perturbations26. This approach employs affinity-based probes to capture epichaperomes along with the proteins and protein complexes they sequester in disease states, representing the complement of dysfunctional, disease-associated PPIs in each condition. These captured interactors are then identified and quantified through mass spectrometry, followed by bioinformatic analyses integrating PPI and pathway databases. This enables the derivation of disease stage-specific PPI network rewiring and the functional consequences of such systems-level alterations26, including dynamic network changes across the AD spectrum. By revealing how epichaperomes rewire PPIs and alter cellular functions in a disease-specific manner, dfPPI can provide critical insights into the molecular underpinnings of AD. The complete datasets and associated analytics are found in Supplementary Data 2.

Across all MCI patients, dfPPI identified 4,214 proteins sequestered by epichaperomes (FC>1 MCI vs. NCI), and 3,998 proteins were similarly sequestered in AD patients (FC>1 AD vs. NCI). Comparison between MCI and AD revealed distinct shifts in protein enrichment, with 2,549 proteins preferentially enriched in AD (FC>1 AD vs. MCI) and 2,923 in MCI (FC>1 MCI vs. AD). Upon applying recommended statistical cutoffs21, 1,814 proteins were identified in MCI (MCI vs. NCI) and 2,090 in AD (AD vs. NCI), highlighting widespread network disruptions even at early stages. Importantly, the functional dysregulation caused by epichaperomes was already fully manifest in MCI patients, as indicated by the large number of altered PPIs.

Reactome mapping revealed 403 protein pathways rewired in MCI and 333 in AD (p.adjust < 0.05). The identification of more pathways in MCI underscores the significant functional changes that occur early in the disease, with epichaperome formation driving a large-scale network disruption before the transition to full-blown AD. Comparing MCI and AD, 253 pathways were preferentially enriched in MCI and 38 in AD, further supporting the notion that epichaperomes initiate widespread dysfunction early in the disease, setting the stage for a cascade of changes that continue to unfold as AD progresses. This pattern suggests that while the disease exacerbates some pathways in AD, new pathways are unleashed later in the continuum, reflecting an evolving landscape of cellular dysfunction (Fig. 2b).

Among the earliest epichaperome-mediated disruptions are pathways governing synaptic function and plasticity33–40, such as transmission across chemical synapses, glutamatergic synapse, post-NMDA receptor activation events, protein-protein interactions at synapses, actin remodeling, intracellular signaling by second messengers, MAPK family signaling cascades, neurotrophin signaling, long-term potentiation, axon guidance, and the neurotransmitter release cycle (Fig. 2b,c). These pathways are critical for maintaining synaptic communication and stability, processes fundamental to learning and memory, which are significantly impaired in the early stages of AD41–44.

Additionally, early epichaperome-driven dysfunction extends to neuroinflammatory responses, including pathways involved in cytokine signaling, inflammasomes, interleukin-1 family signaling, and antigen presentation (Fig. 2b,c), reflecting an early unleashing of inflammatory processes that contribute to neuronal damage45–49. These inflammatory responses likely play a key role in the early neuronal dysfunction observed in MCI, even before overt cognitive decline is evident.

Processes related to cell cycle reentry, translation initiation, and phospholipid metabolism are also dysregulated by epichaperomes at the MCI stage (Fig. 2b,c). This suggests that epichaperome formation in neurons may inappropriately push them to re-enter the cell cycle, disrupt protein synthesis, and ultimately compromise neuronal function50,51. As the disease progresses, epichaperome-mediated dysregulation of autophagy, iron metabolism, trafficking, and endocytosis becomes more pronounced (Fig. 2b,c), leading to impaired cellular waste removal and nutrient recycling, and contributing to the buildup of toxic proteins52–54.

In AD, the reliance of metabolic, vascular, and complement cascade pathways55–57 on epichaperomes becomes increasingly evident (Fig. 2b,c), reflecting their pivotal role in driving systemic dysfunction that exacerbates neuronal damage and accelerates cognitive decline. The epichaperome-mediated dysregulation of complement cascade processes further suggests that a sustained and detrimental inflammatory response persists throughout the AD continuum, driven by the aberrant scaffolding activity of epichaperomes.

In summary, these results highlight that epichaperomes begin to disrupt critical brain networks early in the AD spectrum with widespread functional alterations already fully manifest in MCI. These changes continue to cascade as the disease progresses, impairing essential neuronal processes and contributing to systemic dysfunction. The evolving nature of these network disruptions underscores the pivotal role of epichaperomes in reshaping brain function, driving both early and late-stage AD pathology.

Trajectory of epichaperome formation in AD

Given that widespread epichaperome-mediated dysfunctions are already manifest in the MCI stage, this raises the question of how early in the disease these disruptions begin. While our human patient samples cover MCI and AD stages, they do not include preclinical AD, a phase where significant brain changes occur prior to clinical symptom onset. The systems-level analysis in MCI revealed that epichaperomes are already driving widespread dysfunction at this early stage, strongly indicating that epichaperome formation may begin even earlier—during preclinical AD. To investigate these earliest stages of epichaperome formation, we utilized the APP NL-F mouse model, which replicates the full spectrum of AD, from preclinical stages to late-stage disease58. We conducted a detailed analysis of epichaperome formation at various ages (2, 3, 5, 7, 12, and 15 months) to encompass the full disease trajectory. As controls, we used C57BL/6J (wild-type, WT) mice (Fig. 3a).

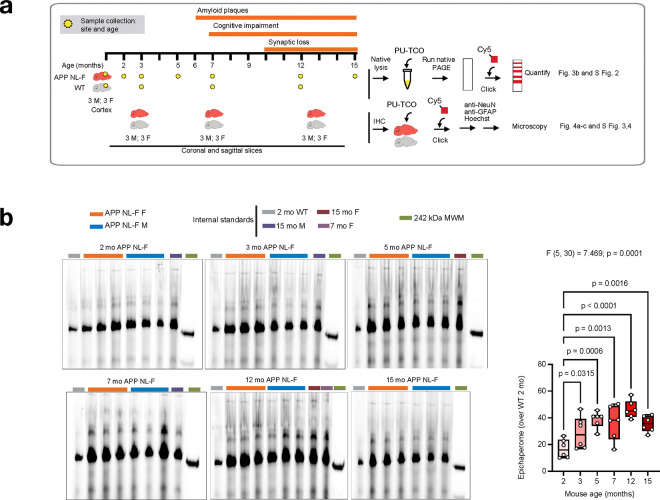

Figure 3. Epichaperome formation begins in the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

a Study design to assess the spatiotemporal trajectory of epichaperome formation in AD-vulnerable brain regions of APP NL-F mice compared to control (WT) mice, with the aim of identifying anatomical and cellular vulnerability to epichaperome formation over time. Epichaperome levels were analyzed both in the cortex (via native PAGE separation and detection with PU-TCO clicked to Cy5 dye) and across the whole brain (using confocal microscopy on sagittal and coronal slices stained with PU-TCO clicked to Cy5 dye) at targeted age intervals. For native PAGE and immunodetection analysis, assessments were conducted at 2, 3, 5, 7, 12, and 15 months of age, with 3 males and 3 females per group, focusing on cortical regions associated with cognitive and synaptic vulnerability in AD. For microscopy-based analyses, coronal sections representing key AD-vulnerable regions (dentate gyrus, CA1, CA3, dorsal subiculum, entorhinal cortex, and frontal cortex) were examined at 3, 7, and 12–14 months of age in 3 male and 3 female mice per group. This design allowed for a detailed analysis of the spatiotemporal progression and regional specificity of epichaperome formation across AD-relevant stages in APP NL-F mice. b Trajectory of epichaperome levels in the APP NL-F mouse cortex across disease stages, evaluated via native PAGE separation and detection with PU-TCO clicked to Cy5 dye. See Supplementary Fig. 2 for WT mice. Data are plotted using a min-to-max box-and-whisker plot, with data points representing individual mice. The box indicates the interquartile range, and the line within the box marks the median. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by the Two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli for multiple comparisons, with p < 0.05 considered significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In APP NL-F mice, amyloid plaques composed of Aβ42 begin forming around 6 months of age59, but significant changes in brain function, such as hypersynchrony—excessive synchronized activity between brain regions—emerge as early as 3 months60. This hypersynchrony is most prominent in the hippocampal and frontal/cingulate networks and parallels neural disruptions observed in preclinical AD. These early changes occur well before synaptic loss, which typically manifests between 9 and 12 months59. Cognitive flexibility impairments are evident by 3 months, followed by spatial memory deficits at 7 months, representing the transition from preclinical AD to MCI and later symptomatic stages58. The APP NL-F model, therefore, enables investigation of epichaperome formation across all stages, including preclinical changes.

By combining native PAGE separation with blotting using PU-TCO, an epichaperome-specific small molecule probe32, we detected epichaperome formation in the cortex of APP NL-F mice as early as 2–3 months (Fig. 3b)—well before the onset of amyloid plaque formation (reported at 6 months)59 and prior to the emergence of spatial memory deficits (reported at 7–8 months)58. Epichaperome levels increased gradually, peaking between 5–7 months and remaining high thereafter (Fig. 3b). Similar to the human condition, epichaperomes were predominantly present in APP NL-F mice compared to WT controls and their presence was independent of chaperone concentration in the cortex (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b).

To further confirm epichaperome formation during the preclinical stage of AD and investigate the specific cellular vulnerabilities to epichaperome formation, we performed click chemistry labeling on brain slices using PU-TCO (epichaperome probe) and PU-NTCO (control probe) (Fig. 3a, 4a–c and Supplementary Figs. 3,4)32. Slices were counterstained with Hoechst to visualize individual cells, and immunostaining for NeuN and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) distinguished neurons from astrocytes. WT mice, as well as slices pre-treated with the epichaperome disruptor PU-H71, served as negative controls18,61, with no detectable signal in these conditions, confirming probe specificity (Supplementary Fig. 3,4).

Figure 4. Epichaperomes form in key AD-vulnerable brain cells and regions, progressively increasing in levels and spatial distribution as disease advances in APP NL-F mice.

a Epichaperome quantification in APP NL-F mice at 3, 7, and 12–14 months of age (3 females and 3 males per group) highlights their early formation and progressive accumulation in AD-vulnerable brain regions. Coronal brain slices stained with PU-TCO clicked to Cy5 dye, corresponding to Bregma −1.22 mm to −2.54 mm (Allen Brain Atlas, images 80–87), were analyzed across regions associated with memory and cognitive function. Data are presented with box and whiskers indicating the minimum to maximum range, with the interquartile range boxed and the median line indicated. Each data point represents an individual brain slice. Statistical analysis among regions within each age group was performed using Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA (F*(DFn, DFd) = 12.56 (20.00, 160.3); p < 0.0001) with Dunnett’s post-hoc test. See also Supplementary Fig. 4,5. b Schematic illustration of the spatiotemporal trajectory of epichaperome formation in APP NL-F mice, showing highest early levels in the CA3 and dentate gyrus at 3 months, with CA1 following in intensity and dorsal subiculum, entorhinal cortex, and frontal cortex subsequently affected. Levels in all regions progressively increase by 7 months, with widespread, equally high levels across all regions by 12–14 months, suggesting a gradual progression from initial epichaperome formation in CA3 and DG toward CA1, dorsal subiculum, entorhinal cortex, and eventually the frontal cortex. Figure adapted using Allen brain, coronal slice image 85. c Representative sagittal slice of an APP NL-F mouse brain as in a stained with PU-TCO clicked to Cy5 dye, showing epichaperome formation. Inset 1 highlights the hippocampus, revealing strong epichaperome staining in the dentate gyrus (DG) and CA3-CA1 regions. Zoomed-in regions 2–4 show intense signal in glutamatergic neurons and surrounding astrocytes. GFAP marks astrocytes, NeuN labels neurons, and Hoechst marks nuclei. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We analyzed epichaperome formation in key AD-vulnerable brain regions in APP NL-F mice at 3, 7, and 12–14 months of age, focusing on hippocampal subfields (pyramidal layers of CA1 and CA3, the polymorph and granule cell layers of the dentate gyrus, DG), dorsal subiculum, entorhinal cortex, and frontal cortex (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 5). These regions, associated with synaptic plasticity, spatial navigation, contextual memory, and executive functions, represent key circuits progressively affected in AD62,63.

At 3 months, epichaperome signal was already detectable, with the strongest signal observed in CA3 and the DG, followed closely by CA1, then dorsal subiculum, entorhinal cortex, and frontal cortex (Fig. 4a). Quantitative analysis revealed no significant difference between CA3 and DG. Signal in CA1 was slightly lower but not significantly different compared to the DG, while epichaperome levels in hippocampal regions (CA3, DG) were significantly higher than in subiculum and cortical regions (e.g., DG vs. entorhinal cortex, p = 0.0075; DG vs. frontal cortex, p = 0.0183). WT mice showed no detectable signal in any region (DG APP vs. WT, p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

By 7 months, epichaperome levels had increased across all brain regions analyzed, with the highest levels in CA3, CA1, and DG. The difference among these hippocampal subfields (CA3, DG, and CA1) and the dorsal subiculum was no longer observed (p values were > 0.9999), indicating a progressive spread within hippocampal formation subfields. Despite this convergence in hippocampal subfields, significant differences remained between hippocampal and cortical regions, with DG levels still significantly higher than both entorhinal cortex (p = 0.0053) and frontal cortex (p = 0.0063). WT mice continued to show no detectable signal in any region, reinforcing that epichaperome formation is specific to the AD disease progression observed in APP NL-F mice.

At 14 months, epichaperome levels reached comparably high intensities across all regions, with no significant differences among them (p values > 0.9999 across comparisons). WT mice again showed no detectable epichaperome signal (Supplementary Fig. 4).

These findings demonstrate that epichaperome formation follows a distinct spatiotemporal trajectory in AD-vulnerable regions (Fig. 4b) paralleling findings in human AD62,63. Initial high levels are detected in CA3 and DG at the early preclinical stage (3 months), followed closely by CA1, then dorsal subiculum, entorhinal cortex, and finally the frontal cortex. This progression suggests that epichaperome formation initiates in DG/CA3 and gradually spreads, involving sequentially larger brain areas as the disease advances, with a continuous increase in levels across all regions by late-stage disease (12–14 months).

Notably, these earliest vulnerable regions—CA3, DG, and CA1—are primarily composed of excitatory neurons, particularly glutamatergic neurons, which are critical for synaptic plasticity and memory35. Indeed, in terms of earliest cellular vulnerability, high-resolution imaging of the 3-month-old APP NL-F hippocampus revealed pronounced epichaperome formation in glutamatergic neurons and adjacent astrocytes, affecting soma, nuclei, and projections at early stages (see inset showing glutamatergic neurons in CA3, Fig. 4c). This suggests a region-specific susceptibility rooted in the cellular composition, with epichaperome formation targeting glutamatergic neurons and their functionally supportive glia, potentially disrupting the synaptic plasticity and cognitive functions associated with these regions at the earliest stages of AD onset.

In sum, our analysis of the APP NL-F mouse model revealed that epichaperome formation begins in the early, preclinical stages of AD, well before the onset of amyloid plaque formation and cognitive decline. Epichaperomes were detectable as early as 2–3 months (preclinical stage), with levels peaking between 5–7 months (MCI stage), particularly in hippocampal subfields known for their excitatory, glutamatergic composition. By the late-stage disease (12–14 months), epichaperome levels reached comparably high intensities across all brain regions analyzed, indicating a widespread and homogenized pattern of epichaperome formation. This region- and cell-type-specific vulnerability underscores the selective impact of epichaperomes on key brain areas essential for memory and synaptic function, positioning glutamatergic neurons as pivotal drivers of early network disruptions. The continuous expansion and escalation of epichaperome formation across interconnected brain regions support a model in which epichaperomes contribute to the structural and functional progression of AD, ultimately driving widespread network dysfunction by late-stage disease.

Glutamatergic neurons vulnerability to epichaperome formation

Given the early formation of epichaperomes in glutamatergic neurons observed in the APP NL-F mouse model, we sought to determine whether human neurons display a similar vulnerability under AD-related stress. To investigate this, we used human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived glutamatergic neurons (iGlut) to explore epichaperome formation under disease-relevant conditions (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 6a-c). We confirmed that iGlut neurons, when derived from healthy patients, exhibited minimal to no epichaperome levels under normal conditions, commensurate with epichaperome formation being a feature specific to disease18,24 (Supplementary Fig. 6a-c).

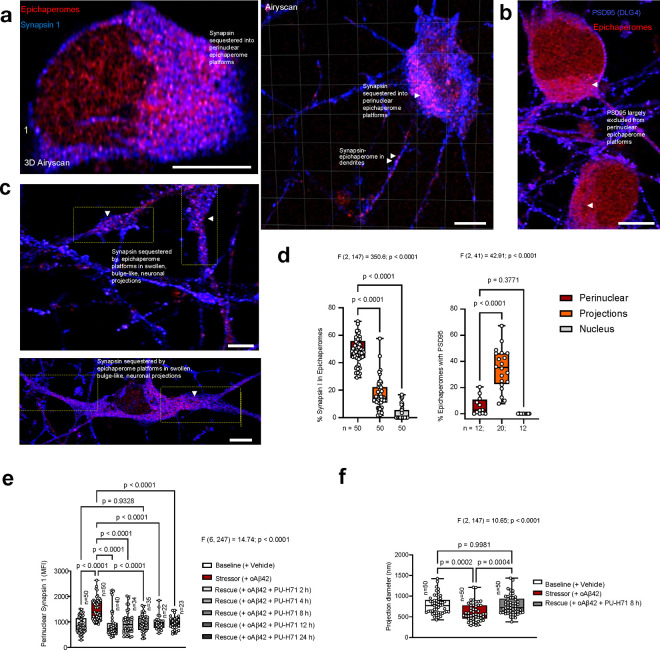

Figure 5. Glutamatergic neurons form epichaperomes under Alzheimer’s disease-related stressors.

Micrographs display human iCell Glutamatergic Neurons (iGluts) treated with oligomeric Aβ42, highlighting the susceptibility of these neurons to epichaperome formation under Alzheimer’s disease-related stressors. The main images show widespread epichaperome presence throughout the neuronal soma and projections. Inset 1 emphasizes large perinuclear epichaperome platforms as well as the formation of nuclear platforms. Zoomed-in regions 2 and 3 detail epichaperome signals within axonal swellings and dendritic spines, respectively. Region 4, an additional zoom of region 3, is co-stained with PSD95 to further highlight the localization of epichaperomes in dendritic spines. Epichaperomes are marked by PU-TCO clicked to cy5 (red), neurons by anti-betaIII tubulin (green), and PSD95 is shown in blue. See also Supplementary Fig. 3 and 4. Micrographs are representative of 50 neurons from three independent experiments. Scale bars, 5 μm.

We had previously shown that application of oligomeric Aβ42 (oAβ42), a well-established AD-related stressor64,65, causes significant alterations in glutamatergic neurons, including synaptic protein redistribution, such as Synapsin 1, as well as cytoskeletal disruptions66. These changes impair synaptic plasticity and alter neurotransmitter release66, making this model ideal for further exploration of epichaperome formation. Indeed, we found that treatment with oAβ42, but not scrambled Aβ peptide, robustly induced epichaperome formation in iGlut neurons (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 6a-c). This was corroborated in another cellular model, N2a neuronal cells, where similar results were observed (Supplementary Fig. 7a-c).

Epichaperomes formed large platforms within the soma, spanning both the cytosolic and nuclear regions, with pronounced perinuclear formations. Additionally, epichaperomes were present in neuronal projections, including within dendritic spines (Fig. 5). Notably, in projections exhibiting morphological abnormalities—specifically, being thicker and shorter than typical—epichaperomes accumulated at sites of swelling. These sites also displayed disrupted cytoskeletal structure as indicated by altered βIII tubulin staining, a hallmark contributing to synaptic dysfunction and impaired connectivity in various neurodegenerative conditions, including AD and PD67,68.

In conclusion, these cell-based findings confirm that glutamatergic neurons are particularly susceptible to epichaperome formation under AD-related stress. The extensive formation of epichaperomes throughout the neuronal soma and projections underscores the vulnerability of these neurons, with significant implications for synaptic function and neuronal integrity. The accumulation of epichaperomes in regions essential for neurotransmission, such as dendritic spines and axonal swellings, strongly supporting a role in the synaptic dysfunction observed in AD.

Synaptic function remodeling across the AD continuum

Building on earlier findings of epichaperome formation in glutamatergic neurons and their involvement in synaptic dysfunction, we focused on how epichaperomes impact key glutamatergic neuron-dependent pathways related to synaptic function and plasticity across the AD spectrum (Fig. 6a–c and Supplementary Data 3). These dfPPI-identified pathways—such as transmission across chemical synapses, glutamatergic synapses, PPIs at synapses, and axon guidance (Fig. 6a,b)—are critical for neuron-to-neuron communication and the maintenance of cognitive functions, particularly learning and memory, which are heavily reliant on glutamatergic neurotransmission69.

Figure 6. Impact of epichaperomes on synaptic function and plasticity across the AD continuum.

a Changes in specific proteins within pathways related to synaptic function and plasticity across the AD continuum, based on dysfunctional Protein-Protein Interactome (dfPPI) analysis. Blue bars represent proteins sequestered by epichaperomes in one comparison, while red bars indicate proteins that are less sequestered or not captured in subsequent stages, showing how the composition of proteins affected by epichaperomes evolves as the disease progresses from mild cognitive impairment through advanced stages of AD. dfPPI detected changes in PD and APP NL-F mice (15 mo F) and protein expression changes in AD detected by quantitative proteomics in bulk brain tissue (NeuroPro database) are shown for comparison. b Adapted KEGG glutamatergic synapse pathway illustrates synaptic proteins impacted by epichaperomes across the AD continuum. c The Venn diagram compares proteins identified by dfPPI as sequestered by epichaperomes in AD versus changes in protein expression in AD detected by quantitative proteomics in bulk brain tissue (NeuroPro database). This comparison highlights that protein sequestration into epichaperomes occurs independently of overall expression changes. See Supplementary Data 3,4 for complete datasets and analytics.

Our analysis of the dfPPI data revealed that proteins involved in these critical synaptic processes were sequestered by epichaperomes (depicted by blue bars, Fig. 6a) early in the disease, during the MCI stage (see MCI vs. NCI), and remained sequestered as the disease progressed (see MCI vs. NCI and AD vs. MCI, blue bars). Interestingly, we observed dynamic changes as AD advanced, with new proteins being recruited to epichaperomes (blue bars) and others excluded (red bars). This dynamic remodeling suggests that the synaptic dysfunction observed early in the disease is not static but evolves as epichaperomes continuously reorganize protein networks, and that epichaperome-mediated remodeling of synaptic networks is an evolving process, continually reshaping protein interactions. Importantly, these changes were AD-specific, as the patterns of protein sequestration and exclusion differed when comparing AD and PD (Fig. 6a, see AD vs. NCI compared to PD vs. NCI), supporting the idea that epichaperome-driven disruption manifests differently functionally across distinct neurodegenerative disorders.

A crucial finding from our study is that the sequestration of proteins into epichaperomes occurred independently of changes in protein expression levels. When comparing the proteins identified by dfPPI as sequestered by epichaperomes to those detected by quantitative proteomics in bulk brain tissue (total protein, NeuroPro database)70, we found that the expression of epichaperome-sequestered proteins remained unchanged in AD for the majority (79.95% of proteins), with only a small fraction showing changes in concentration (9.88% with decreased levels and 8% with increased levels in AD vs. NCI) (see NeuroPro data versus dfPPI data, Fig. 6a,c and Supplementary Data 4). This stands in contrast to the classical view that changes in protein expression are key drivers of disease. Here, it is the sequestration into epichaperome platforms, rewiring their local interactome, that drives functional disruption.

To further support this notion, we focused on Synapsin 1 (SYN1)—a key synaptic protein that we identified as an epichaperome interactor in AD (Supplementary Data 2). Previous studies have shown that Synapsin 1 levels remain either unchanged or slightly decreased in AD brains and in cellular and mouse models of AD70–72. Despite these minimal changes in expression, Synapsin 1 mislocalization is often observed in these disease models and is directly linked to Synapsin dysfunction. This mislocalization affects axonal transport, reduces synaptic vesicle availability at presynaptic terminals, and disrupts neurotransmitter release, ultimately impairing synaptic plasticity and memory68,73,74.

Using iGlut neurons under oAβ42 stress and high-resolution microscopy (Airyscan), we confirmed that this stressor does indeed lead to Synapsin 1 mislocalization without significantly altering Synapsin 1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 8a-c). Under normal physiological conditions, Synapsin 1 is typically localized at presynaptic terminals, where it binds to synaptic vesicles and helps maintain them in the reserve pool, controlling their availability for release during synaptic transmission74,75. However, in neurons exposed to stress, we observed a markedly different distribution: Synapsin 1 was found primarily in the perinuclear region, rather than at presynaptic terminals, and was largely associated with epichaperome platforms at this location (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 8a-c,9a,b). Smaller, focal formations of epichaperomes and Synapsin 1 were also observed throughout axons and dendrites (Fig. 7a,b). Notably, neurons displaying altered projection morphology—characterized by shorter, thicker structures—showed increased Synapsin 1 sequestration into epichaperomes at the base of these projections and along swollen or bulge-like structures (Fig. 7b). Not all synaptic proteins showed similar epichaperome sequestration, as for example PSD95 (aka DLG4), was largely excluded from perinuclear platforms (Fig. 7c). Crucially, treatment with the epichaperome disruptor PU-AD restored Synapsin 1 distribution (Fig. 7d and Supplementary Fig. 9a,b) to normal levels (baseline vs 8 h PU-H71, p = 0.9328), demonstrating that the negative impact of epichaperome sequestration of Synapsin 1 manifests, in part, through altered physiological cellular localization. This restoration was accompanied by a reversal of projection morphology abnormalities, with neuronal projections regaining baseline-like structural integrity (Fig. 7e and Supplementary Fig. 9a,b).

Figure 7. Epichaperomes sequester Synapsin 1 altering its physiological cellular location and distribution.

a,b Micrographs - representative of 50 neurons from three independent experiments - show human iCell Glutamatergic Neurons (iGlut neurons) treated with oligomeric Aβ42 (100 nM, 24 h), highlighting Synapsin 1 sequestration by epichaperomes into perinuclear platforms (a) and at aberrant neuronal projection sites (b). c PSD95, another important synaptic protein, is largely excluded from the large perinuclear epichaperome platforms. Epichaperomes are marked by PU-TCO clicked to Cy5 (red), while Synapsin 1 and PSD95 are shown in blue. Scale bars represent 5 μm. d Colocalization analysis of epichaperomes with Synapsin 1 and PSD95 in the specified neuronal regions, indicating their spatial association across these cellular regions. e,f Rescue: iGlut neurons were exposed to stressor (100 nM oligomeric Aβ42, 24 h) followed by treatment with an epichaperome disruptor (1 μM PU-H71, 2 to 24 h). d-f All data are plotted using a min-to-max box-and-whisker plot, where individual data points represent analyzed regions across 50 neurons for Synapsin 1 and 12 for PSD95 (d) and individual neurons for (e) and individual projections for (f) from 3 independent experiments. The box indicates the interquartile range, and the line within the box marks the median. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc test. See also Supplementary Fig. 9. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In summary, these synaptic interrogation findings indicate that epichaperome formation significantly impacts pathways related to synaptic function and plasticity early in AD and continues to remodel these pathways as the disease progresses. Proteins involved in these pathways, such as Synapsin 1, are sequestered by epichaperomes, leading to their altered distribution, which may impact function despite no changes in cellular protein concentration. This underscores the vulnerability of glutamatergic neurons to epichaperome formation and the continuous disruption of synaptic processes throughout the disease continuum. While a detailed molecular understanding of this sequestration is beyond the scope of this study, these results link prior findings of synaptic protein mislocalization in stressed neurons to a mechanism: sequestration into epichaperome platforms as a root cause of mislocalization.

Trajectory of epichaperome-mediated synaptic dysfunction

Given the evolving impact of epichaperome formation on glutamatergic synaptic function, we next sought to better delineate the linear trajectory of these synaptic disruptions as the disease progresses. Specifically, we aimed to determine whether the increasing levels of epichaperomes observed throughout AD correlate with a broadening impact on additional synaptic pathways and neuronal types beyond glutamatergic neurons. To explore this, we applied dfPPI to female APP NL-F mice at 7 months of age—when cognitive deficits begin to appear—and 15 months of age—when cognitive deficits become more severe—along with age-matched wild-type (WT) controls (Fig. 8a and Supplementary Data 5).

Figure 8. Temporal trajectory of synaptic networks dysregulated by epichaperomes in APP NL-F mice and human AD brains.

a Schematic of the experimental design. The diagram illustrates the application of the dysfunctional Protein-Protein Interactome (dfPPI) method to analyze brain specimens from APP NL-F mice at 7 months (early-stage cognitive decline) and 15 months (late-stage cognitive decline), as well as age-matched wild-type (WT) controls for comparison. b,c Reactome pathway analysis of dfPPI results in APP NL-F mice. The maps display the pathways dysrupted across the disease continuum, with b showing the shift in pathways between 7 and 15 months of age (APP 7mo F > APP 15mo F, reflecting changes in the MCI human disease) and c highlighting late-stage changes (APP 15mo F > APP 7mo F, reflecting changes observed in late-stage human AD). Specific synaptic pathways related to glutamatergic dysfunction in early stages (7mo) and additional disruptions involving inhibitory circuits, such as GABAergic signaling, in later stages (15mo) are highlighted. d Similar analysis in human AD patients, comparing epichaperome-high (EpiHigh) vs. epichaperome-low (EpiLow) cohorts. These results show broader synaptic dysfunction across multiple neuronal subtypes in patients with elevated epichaperome levels, underscoring the progressive nature of epichaperome-mediated network dysfunction in AD. Refer to Supplementary Data 5,6 for complete datasets and analytics.

We found that protein network dysfunctions in APP NL-F mice closely mirrored patterns observed in human AD brains. At 7 months, these mice displayed dysfunctions across a range of pathways that are also disrupted in early-stage human AD, including signaling, inflammatory responses, cell cycle re-entry, transcription, RNA metabolism, and stress responses (Fig. 8b). Notably, synaptic dysfunction was akin to that seen in human MCI disease, with disruptions in glutamatergic neuronal activities, such as NMDA receptor activation, neurotransmitter release, AMPA receptor signaling, synaptic plasticity, and synaptic protein interactions (Fig. 8b). Metabolic dysfunction was primarily in phospholipid metabolism, and thus less pronounced compared to human disease.

By 15 months, additional dysfunctions were evident, closely aligning with late-stage human AD. This included disruptions in metabolic pathways, vascular events, axon guidance, cellular adhesion, and extracellular matrix organization (Fig. 8c). There was a significant shift from early glutamatergic dysfunction to broader disruptions of both excitatory and inhibitory circuits and presynaptic mechanisms. Newly affected pathways included GABAergic signaling, kainate receptor activity, G protein-gated potassium channels, and neurexin/neuroligin signaling, highlighting the disease’s impact on inhibitory circuits and presynaptic processes (Fig. 8c)76–79. These changes suggest a broader neuromodulatory dysregulation, affecting calcium homeostasis and synaptic architecture, crucial for maintaining neuronal communication and stability.

In summary, the transition from 7 to 15 months reflects a shift from early-stage glutamatergic dysfunction to broader synaptic and neuronal network disruptions, involving both excitatory and inhibitory pathways. This suggests that as the disease progresses, and epichaperomes expand their negative impact, not only glutamatergic neurons but also other neuronal subtypes become affected by epichaperomes, leading to widespread brain network failure.

We confirmed this progression in human AD patients. Similar to the broader synaptic dysfunctions observed in the 15-month-old APP NL-F mouse brains, patients with higher epichaperome levels (Epi-H) exhibited a broader spectrum of disrupted synaptic functions compared to those with lower epichaperome levels (Epi-L) (Fig. 8d and Supplementary Data 6). In Epi-H patients, the disruption extended beyond the glutamatergic networks observed in earlier disease stages, encompassing additional synaptic pathways and involving multiple neuronal subtypes, much like the progression seen in the APP NL-F model at 15 months.

This indicates that as epichaperome levels increase, an expanding set of synaptic pathways and neuronal types become progressively affected. The progression from initial glutamatergic dysfunctions to broader synaptic disruption highlights the dynamic and expanding influence of epichaperomes on brain networks. The data demonstrate that worsening cognitive symptoms in AD are closely linked to the spread and intensification of epichaperome activity. As epichaperome levels rise and these platforms extend to additional cells and brain regions, they progressively co-opt new synaptic networks, further accelerating cognitive decline and exacerbating neuronal dysfunction.

Validation of epichaperome-mediated dysfunctions

Our postmortem human studies identified numerous protein networks dysregulated by epichaperomes across the AD spectrum particularly those related to synaptic function, neuroplasticity, and memory. To directly link these disruptions to epichaperome formation and determine whether they are reversible, we turned to the APP NL-F mouse model. This model is ideal for two key reasons: first, the same synaptic pathways disrupted by epichaperomes in human AD were also identified in APP NL-F mice through dfPPI, establishing a consistent link between epichaperome formation and synaptic dysfunction in both species. Second, the glutamatergic neurons in the hippocampus—responsible for executing these synaptic functions—were found to be particularly vulnerable to epichaperome formation early in disease progression, a pattern mirrored in human AD.

These early epichaperome formations target glutamatergic neurons, particularly affecting excitatory synapses and disrupting synaptic plasticity and cognitive functions. This selective vulnerability underlies early-stage deficits in memory and learning, driven by disruptions in key pathways such as those involved in long-term potentiation (LTP) and neurotransmitter release. As the disease progresses, epichaperomes expand beyond glutamatergic neurons, sequestering additional synaptic proteins and disrupting other neuronal types, including GABAergic neurons and inhibitory circuits. This progression culminates in broader disruptions of synaptic networks, as seen in the dfPPI analysis of 15-month-old APP NL-F mice, where both excitatory and inhibitory pathways are compromised.

Therefore, to test the hypothesis that epichaperomes directly contribute to memory dysfunction and validate our dfPPI findings, we assessed synaptic plasticity and memory through the 2-day radial-arm water maze (RAWM), fear conditioning, object location tasks (OLT), and LTP— a type of synaptic plasticity that is thought to underlie memory formation— in APP NL-F and WT mice treated with either an epichaperome disruptor, PU-AD, or with vehicle control (Fig. 9a, 10a). These tasks measure hippocampus-dependent functions such as spatial memory, associative learning, and recognition memory, which dfPPI indicated are dysregulated by epichaperomes. Each test reflects different aspects of the synaptic networks impacted by epichaperomes, providing direct functional readouts of the protein networks disrupted by epichaperome formation in AD.

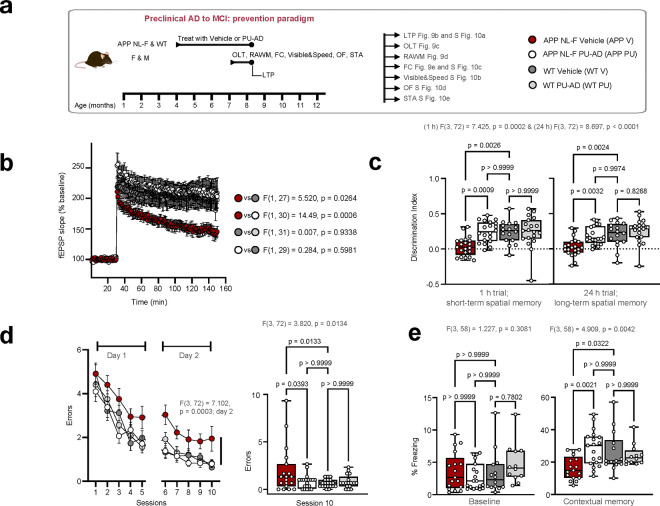

Figure 9. PU-AD treatment prevents synaptic plasticity and memory deficits in APP NL-F mice.

a Schematic of the experimental design for APP NL-F (APP) and WT littermates treated with vehicle (V) or PU-AD (PU) as indicated. Treatment started at an age where the mice do not exhibit deficits (4 months of age), and continued for 3 months, until an age when the mice display moderate impairments (4 months of age). OLT, object location task; RAWM, radial arm water maze; FC, fear conditioning; OF, open field; STA, sensory threshold assessment; LTP, long-term potentiation. b LTP as in a measured as fEPSP slope (% baseline) over time in hippocampal slices from individual mice. LTP measures synaptic plasticity, with higher fEPSP slopes indicating stronger synaptic responses. Graph, mean ± s.e.m., two-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA. Slices: n = 15 (3M,5F) for APP V; n = 17 (4M,3F) for APP PU; n = 14 (4M,5F) for WT V; and n = 19 (5M,6F) for WT PU. c Discrimination index (DI) in the OLT reflects the ability of individual mice to distinguish between moved and non-moved objects. Short-term spatial memory was determined as in a with a 1-hour interval between the learning and the test trial, and long-term spatial memory with a 24-hour interval between trials. Higher DI indicates better spatial memory. Mean ± s.e.m., one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc, n = 21 (11M,10F) for APP V; n = 20 (11M,9F) for APP PU; n = 16 (9M,7F) for WT V; n = 19 (9M,10F) for WT PU. d RAWM performance, shown as mean ± s.e.m. errors made over sessions, evaluates short-term reference memory and spatial learning. Mice as in a were tested over two days, with performance assessed in 10 sessions, where fewer errors indicate improved memory and learning. Dara were analyzed via two-way RM ANOVA across all groups for day 2 and one-way ANOVA for block 10 with Bonferroni’s post-hoc, n = 19 (10M,9F) for APP V; n = 20 (10M,10F) for APP PU; n = 20 (11M,9F) for WT V; and n = 17 (9M,8F) for WT PU. e Percentage of freezing, representing fear response in individual mice as in a, measured before shock (baseline) and 24 hours later (contextual memory). Higher percentages of freezing indicate stronger associative memory of the aversive stimulus. Graph, mean ± s.e.m., one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc, n = 17 (8M,9F) for APP V; n = 19 (10M,9F) for APP PU; n = 14 (8M,6F) for WT V; and n = 12 (6M,6F) for WT PU. See also Supplementary Fig. 10. Source data are provided as Source Data file.

Figure 10. PU-AD treatment restores synaptic plasticity and memory deficits in APP NL-F mice.

a Schematic of the experimental design for APP NL-F (APP) and WT littermates treated with vehicle (V) or PU-AD (PU) as indicated. Treatment started at an age where the mice already exhibit memory deficits (7 months of age), and continued for 3 months, until an age when the mice display severe impairments (10 months of age). OLT, object location task; RAWM, radial arm water maze; FC, fear conditioning; OF, open field; STA, sensory threshold assessment; LTP, long-term potentiation. b LTP measured as fEPSP slope (% baseline) over time in hippocampal slices from individual mice as in a. Graph, mean ± s.e.m., two-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA. n = 16 (4M,5F) for APP V; n = 16 (4M,3F) for APP PU; n = 16 (5M,4F) for WT V; and n = 15 (4M,4F) for WT PU. c OLT data for mice as in a with short-term spatial memory determined at 1 h between the learning and the test trial, and long-term spatial memory with 24 h separation between the two trials. Mean ± s.e.m., one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc, n = 16 (9M,7F) for APP V; n = 15 (7M,6F) for APP PU; n = 16 (7M,9F) for WT V; n = 14 (7M,7F) for WT PU. d RAWM performance: mean ± s.e.m. errors over sessions, analyzed via two-way RM ANOVA across all groups for day 2 and one-way ANOVA for block 10 with Bonferroni’s post-hoc, n = 12 (6M,6F) for APP V; n = 12 (7M,5F) for APP PU; n = 17 (8M,9F) for WT V; and n = 18 (9M,9F) for WT PU. e Percentage of freezing, representing fear response in individual mice, measured before shock (baseline) and 24 h later (contextual memory). Mean ± s.e.m., one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc, n = 16 (9M,7F) for APP V; n = 11 (6M,5F) for APP PU; n = 18 (10M,8F) for WT V; and n = 13 (6M,7F) for WT PU. See also Supplementary Fig. 11. Source data are provided as Source Data file.

For example, LTP directly reflects the ability of synapses to strengthen over time80. dfPPI analysis showed that epichaperome formation disrupted key protein networks involved in LTP, impairing synaptic strength and memory processes. OLT evaluates both short-term and long-term spatial memory, processes directly tied to synaptic plasticity and glutamatergic signaling81, which were disrupted in AD according to dfPPI analysis. Similarly, RAWM assesses short-term reference memory and spatial learning, functions that rely on intact hippocampal processes82. dfPPI identified networks involved in axon guidance and synaptic transmission as particularly affected by epichaperome formation, contributing to the spatial learning impairments observed in APP NL-F mice. Lastly, fear conditioning, which assesses hippocampal-amygdala interactions for associative memory83, also showed deficits related to epichaperome-mediated disruption.

APP NL-F mice at 7 months exhibited significant synaptic plasticity impairments (measured by LTP) and memory dysfunction (assessed through the four behavioral tests) compared to age-matched WT mice (Fig. 9b–e). Given this trajectory of cognitive decline, we examined whether pharmacologic epichaperome disruption using the agent PU-AD20 could prevent or reverse impairments by treating mice presymptomatically (4–7 months, prevention, Fig. 9a–e) or postsymptomatically (7–10 months, reversal, Fig. 10a–e).

PU-AD treatment, given at the target engaging dose of 75mg/kg administered 3xweek20, successfully prevented and reversed LTP impairments. In the prevention group, 3-month PU-AD treatment rescued synaptic plasticity deficits compared to vehicle-treated controls (p=0.0006) (Fig. 9b). In the reversal group, PU-AD significantly restored LTP after synaptic deficits had already manifested (p=0.0008) (Fig. 10b). This demonstrates that PU-AD can both prevent and restore synaptic plasticity, returning LTP levels to those seen in WT mice, highlighting its potential in addressing synaptic dysfunction across disease stages. Additionally, PU-AD did not affect basal synaptic transmission, as shown by the input-output relationship in both WT and APP NL-F mice (Supplementary Fig. 10a,11a), confirming that PU-AD specifically targets pathological disruptions caused by epichaperomes without disturbing normal synaptic functions.

Similarly, PU-AD treatment effectively rescued both short-term and long-term spatial memory deficits in the OLT (Fig. 9c,10c). Untreated APP NL-F mice spent similar time exploring both moved and non-moved objects, indicating impaired spatial memory, while PU-AD-treated mice in both prevention and reversal paradigms showed a significant preference for the moved object, mirroring WT behavior (p=0.0006 for short-term, p=0.0002 for long-term memory in the prevention group; p=0.0024 and p=0.0066, respectively, in the reversal group). This suggests that PU-AD can restore hippocampal-dependent spatial memory impaired by epichaperome formation.

Further, RAWM testing revealed that PU-AD treatment significantly reduced spatial memory errors in both paradigms (p=0.0295 in prevention; p=0.0318 in reversal), effectively reversing deficits to levels comparable to WT mice (Fig. 9d,10d). Fear conditioning also showed significant recovery in contextual memory, with PU-AD treatment preventing and restoring deficits (p=0.0016 in prevention, p=0.0294 in reversal) (Fig. 9e,10e). Control experiments, including open field, visible platform, and sensory threshold tests, confirmed that these improvements were due to cognitive recovery rather than differences in motor or sensory function (Supplementary Fig. 10b-e,11b-e).

Crucially, PU-AD did not alter memory or LTP in WT mice (Fig. 9,10), confirming that epichaperome formation is specifically associated with disease processes, and PU-AD does not interfere with normal brain function. This underscores the disease-selective nature of epichaperomes and the precision of PU-AD in targeting pathological changes without affecting healthy neuronal processes.

The improvements in spatial memory and LTP following PU-AD treatment in APP NL-F mice provide strong evidence confirming the direct role of epichaperomes in driving synaptic dysfunction and cognitive impairment across the AD continuum. By preventing and reversing the synaptic disruptions in both early and late stages of the disease, PU-AD validates the dfPPI findings, showing that epichaperomes directly contribute to the network dysfunctions identified in both human and mouse models of AD.

Importantly, these results underscore not only the therapeutic potential of epichaperome disruption but also confirm that epichaperomes are a key driver of the cognitive dysfunction observed across the AD spectrum. The ability of PU-AD to restore normal synaptic function, particularly in glutamatergic and broader synaptic networks, highlights the direct link between epichaperome formation and synaptic PPI network dysfunction. This reinforces the idea that targeting epichaperomes could be an effective strategy for both preventing and reversing AD-related cognitive decline.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that epichaperomes play a central and active role across all stages of the AD spectrum, from the earliest preclinical phases through to advanced cognitive decline. Rather than being byproducts of disease, epichaperomes drive the progressive collapse of neuronal networks by persistently rewiring PPI interactions. This network-level disruption contributes to brain dysfunction, particularly affecting synaptic function and cognition, long before clinical symptoms manifest. By revealing how epichaperomes reshape molecular networks, our findings address a critical gap in AD research: understanding the mechanistic basis of early synaptic failure and progressive neurodegeneration. This represents a paradigm shift: rather than focusing on protein aggregation or on individual proteins, our study underscores the broader concept of network-targeting therapy to address the interconnected dysfunctions underlying AD pathology. This perspective complements existing models of AD, which have traditionally centered on amyloid and tau pathology.

Importantly, our findings underscore the progressive nature of epichaperome-mediated dysfunction: the higher the epichaperome levels, the more pronounced the network disruption. Our analysis reveals a dynamic trajectory of network remodeling, starting with localized disruptions in glutamatergic neurons and expanding to impact broader neuronal networks and brain regions as the disease progresses. This dynamic remodeling highlights epichaperomes as active and evolving contributors to AD pathology, rather than static features of diseased cells. As these pathological scaffolding platforms increase and extend to additional brain cells and regions, they co-opt new PPI networks, further exacerbating neuronal dysfunction. This progressive co-opting indicates that epichaperomes do not merely affect individual proteins or pathways. Rather, epichaperomes continuously and aberrantly reshape entire cellular networks, making network-targeting approaches particularly relevant.

A key insight from this study is that epichaperome formation disrupts neuronal protein function without altering gene expression or protein abundance. This challenges the prevailing view that AD pathology is primarily driven by transcriptional or proteomic changes. Instead, we identify maladaptive PPI network rewiring via epichaperome sequestration as an early and central driver of cognitive dysfunction.

Our results also highlight the selective vulnerability of glutamatergic synapses to epichaperome formation. These synapses, which mediate excitatory signaling in the brain, are critical for cognitive processes such as learning and memory84,85. Because glutamatergic neurons rely on finely tuned synaptic mechanisms, they are particularly sensitive to disruptions in PPI networks. The sequestration of Synapsin 1 into epichaperome platforms results in its mislocalization, impairing synaptic function at the earliest disease stages. This could provide a molecular explanation for why synaptic failure precedes the emergence of amyloid plaques or tau tangles in AD.

As AD progresses, epichaperome-driven dysfunction spreads beyond glutamatergic neurons, impacting inhibitory circuits and neuromodulatory pathways. This mirrors the evolving complexity of the disease process, where early memory deficits give way to broader cognitive impairments, such as executive dysfunction and attentional decline86–88. This shift from localized synaptic dysfunction to widespread network disruption reinforces the importance of early intervention—once epichaperomes form, they not only drive synaptic failure but also establish a framework for escalating neuronal dysfunction16,24.

Our findings provide strong evidence that epichaperome disruption, through pharmacological intervention, offers a compelling therapeutic strategy. The recovery of synaptic function and cognitive performance in APP NL-F mice, even at advanced stages of dysfunction, suggests that targeting epichaperomes could reverse functional impairments across the AD spectrum. Targeting epichaperomes, therefore, offers a network-centric therapeutic approach, emphasizing the potential of reversing systemic, multi-pathway disruptions through a single intervention that could potentially halt or even reverse the complex network failures seen in AD.

Beyond its mechanistic and therapeutic implications, this study provides a comprehensive systems-level map of progressive protein network dysfunction across the AD continuum. By leveraging dfPPI analysis across human and murine brain specimens, validated in mouse models and cellular systems, we define a trajectory of network disruption that begins with early miswiring and expands to broad dysfunctions in disease-associated pathways. This framework extends beyond AD, as PPI network dysregulation is a hallmark of many neurodegenerative and complex diseases, underscoring the broader applicability of network-based approaches in disease research. Additionally, the interactomics datasets generated here provide a valuable resource for the research community, enabling further investigations into the evolving architecture of disease-associated protein networks and their therapeutic potential. Together, these findings establish network biology as a critical framework for understanding disease progression and identifying novel intervention strategies.

In summary, this study redefines AD as a disease of progressive network instability, where the early miswiring of PPI networks—not merely protein aggregation—drives synaptic dysfunction and cognitive decline. We show that epichaperomes act as scaffolding platforms that orchestrate this dysfunction, revealing network dysregulation as both a disease driver and a therapeutic target. Crucially, we demonstrate that these pathological network changes are not only detectable and mappable but also reversible, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention aimed at restoring network resilience. Moving forward, targeting epichaperomes or their downstream effects may offer a paradigm shift in AD treatment—one that prioritizes stabilizing disrupted protein networks rather than focusing on traditional disease hallmarks or single-protein targeting.

METHODS

Human biospecimens research ethical regulation statement

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations for research involving human participants. Postmortem BA9 brain specimens from NCI, MCI, and AD cases were obtained from participants enrolled in the Rush Religious Orders Study (RROS)27,89,90. Each participant underwent comprehensive annual premortem clinical assessments and postmortem neuropathological evaluations. Exclusion criteria included evidence of mixed dementias, Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body disease, frontotemporal dementia, argyrophilic grain disease, vascular dementia, hippocampal sclerosis, and/or strokes/lacunes, as determined by a neurologist23,80,81. The RROS cohort offers a high-quality biospecimen tissue repository with low PMI case materials, high RNA integrity values, and optimal protein concentration, ensuring robust sample quality. A second cohort of BA9 brain tissue samples – designated as the NYUGSOM/NKI cohort - was obtained from tissue banks including the NIH Neurobiobank University of Miami Brain Endowment Bank (UMBEB), Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (CNDR), University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, and the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Brain Resource Center (JHMIBRC). Tissue integrity was confirmed for each case prior to conducting epichaperomics and associated biochemical and functional validation studies. Detailed data on age, sex, PMI, and additional variables are available in Supplementary Data 1. All tissue samples were collected with written informed consent and were de-identified before use in this research. While this study primarily focused on elucidating molecular mechanisms disrupted by epichaperome formation in AD, irrespective of sex, we aimed for a balanced distribution across sexes within each patient group to the extent possible. The distribution reflects a higher number of female participants, aligning with AD demographics. Accordingly, selection was not biased by sex, and sample composition reflects the natural prevalence of AD across sexes.

Animal research ethical regulation statement

All animal studies were conducted in compliance with institutional guidelines and under the following Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved protocols: #05–11-024 and #04–03-009 for Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), AC-AABL0550 and AC-AABQ5559 for Columbia University, and #5832.8 and #6348.11 as per the Animal Resource Centre (ARC) administrative system at the University of Toronto. Founder male and female C57BL/6 mice (RRID:IMSR JAX:000664) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Founder APPNL-F/NL-F mice (RRID:IMSR_RBRC06343), referred to here as APP NL-F, were obtained from RIKEN BioResource Center (Tokyo, Japan). These mice are genetically engineered to carry humanized mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, specifically the Swedish (NL) and Iberian (F) mutations. These mutations increase the production of Aβ42 peptides and elevate the Aβ42 to Aβ40 ratio, closely mirroring the amyloid profiles seen in human AD59. Breeding colonies for each genotype were established using founder mice, and progeny from these colonies were used for all experiments. Genotypes were confirmed using a combination of primers (5’-ATCTCGGAAGTGAAGATG-3’; 5’-ATCTCGGAAGTGAATCTA-3’; 5’-TGTAGATGAGAACTTAAC-3’; 5’-CGTATAATGTATGCTATACGAAG-3’)59. The PCR template involves 35 cycles consisting of 94°C for 30 sec followed by 58°C for an additional 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec and the reaction is quenched at 4°C. This protocol results in a wild-type band at 700 bp and the APP NL-F/NL-F positive mice at 400 bp. It should be noted that a non-specific band is occasionally observed slightly higher than the wild-type band and a positive sample should be run on the same gel to unequivocally identify the true wild-type animals. Mice were housed in groups of 4–5 per individually ventilated cage under a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 a.m. and off at 6:00 p.m.), with controlled temperature (22 ± 1 °C) and humidity (30–70%). Food and water were provided ad libitum. All mice were monitored daily for clinical signs to ensure animal welfare.

Reagents and chemical synthesis

All commercial chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich or Fisher Scientific and used without further purification. The PU-TCO epichaperome probe and the PU-NTCO control probe, as well as the dfPPI chemical probes - PU-beads and control beads - were generated using published protocols23,26,32. The identity and purity of each probe was characterized by MS, HPLC, TLC, and NMR. Purity of target compounds has been determined to be >95% by LC/MS on a Waters Autopurification system with PDA, MicroMass ZQ and ELSD detector and a reversed phase column (Waters X-Bridge C18, 4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm) eluted with water/acetonitrile gradients, containing 0.1% TFA. Stock solutions of all compounds were prepared in molecular biology grade DMSO (Sigma Aldrich) at 1,000× concentrations.

Cell lines and culture conditions

Differentiated iPSC-derived glutamatergic neurons (iGluts) were obtained from Fujifilm Cellular Dynamics (iCell GlutaNeurons, 01279, Catalog # R1116). Neurons were cultured according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a humidified, sterile environment at 37°C and 5% CO2. Before plating, 4-well glass plates (Cellvis, C4–1.5H-N) were coated with 15 mg mL−1 Poly-L-Ornithine (Sigma Aldrich, P3655) as a base layer, incubated 3 h at room temperature. Plates were then washed three times with HBSS and further coated with 0.028 mg mL−1 Matrigel solution (Corning, 354230), incubated overnight at 37°C. Neurons were seeded at 12.5 × 104 cells per well. The neuron culture medium consisted of BrainPhys Neuron Medium (STEMCELL Technologies, 05790), iCell Neural Supplement B, iCell Nervous System Supplement, N-2 Supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 17502–048), laminin (Sigma-Aldrich, L2020), and penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140–122), and was refreshed every two days. N2a cells (CCL-131, RRID: CVCL_0470) were purchased from ATCC and are derived from the brain tissue of a female mouse. PCR analysis confirmed the absence of male-specific Sry gene products. N2a cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11965–092) supplemented with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10082–147) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140–122). Culture media was changed every 2–3 days. All cell lines used in this study were tested and authenticated to be free of human infectious agents and mycoplasma contamination. They were verified through short tandem repeat profiling and underwent karyotyping to confirm the absence of significant chromosomal rearrangements post-reprogramming or differentiation. Cell line selection was not based on gender, sex, or ethnicity.

Stressor preparation and cell treatment