Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant global health issue, characterized by high rates of morbidity and mortality, along with substantial economic strains on healthcare systems. This study explores the potential of Aminophylline (AMP), a medication traditionally used for cardiovascular conditions and bronchiectasis, to enhance TBI outcomes by protecting against neuronal damage. Our findings indicate that AMP treatment significantly reduces neuronal ferroptosis in the cortex, leading to less tissue damage and notable improvements in cognitive and motor functions in mice subjected to controlled cortical impact (CCI). Additionally, we found that TBI resulted in decreased expression of miR-128-3p, a reduction that was further strengthened by AMP treatment. Gain-of-function experiments showed that overexpressing miR-128-3p increases neuronal ferroptosis by targeting Slc7a11, indicating how AMP mitigates cognitive and motor impairments in CCI mice. This study highlights the potential of AMP in treating TBI through the miR-128-3p/Slc7a11 pathway, marking the first report of its protective effects against ferroptosis in TBI.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-025-05601-3.

Keywords: Aminophylline, Traumatic brain injury, Ferroptosis, miR-128-3p, SLC7A11

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is defined as an alteration in the brain function, or other evidence of brain pathology, caused by an external force [1, 2]. TBI has been a major cause of death and disability worldwide, making it a global public health concern [2, 3]. In 2019, it was reported that there were more than 50 million TBI patients worldwide, with 18 million cases in China annually [3]. Current therapeutic strategies for TBI include cellular-based, pharmaceutical, neural stimulation, hyperbaric oxygen therapies, among others [4]. However, the prognosis of TBI patients remains poor, with a rehabilitation rate only approximately 50% [5, 6]. Therefore, it is crucial to explore more effective and affordable therapies for TBI.

Aminophylline (AMP) is an intravenous medication that is widely used and with low cost. It is a combination of theophylline and ethylenediamine (2:1) [7]. Ethylenediamine enhances the water solubility while theophylline is responsible for the pharmacological effect of AMP [8]. As a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, theophylline has been shown to increase cyclic adenine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic 3′,5′ guanosine monophosphate concentrations, resulting in vascular smooth muscle relaxation in multiple organs, including the brain [9]. As a histone deacetylase activator, AMP was demonstrated to activate phosphoinositide-3-kinase-delta (PI3Kδ) to perform anti-oxidative stress [10]. Additionally, accumulative studies have reported that AMP improves mitochondrial biogenesis [11], enhances reactive oxygen species (ROS) concentration [12], elevates malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, lowers the glutathione (GSH) levels, and regulates lipid metabolism [13, 14]. These observed phenotypes align with the characteristic features of ferroptosis [15], prompting us to question whether AMP can mitigate this well-established form of cell death. Iron overload and ferroptosis play significant roles in the pathophysiological processes underlying brain injury [16, 17]. In recent years, numerous studies have shown that inhibiting ferroptosis in brain injury can effectively prevent neuronal death and improve cognitive function in injured mice [18–20]. Consequently, it is worthwhile to investigate the potential anti-ferroptotic effects of AMP in TBI, as well as elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms responsible for these effects.

Previous studies have shown that miRNA profiling is largely altered following TBI, and plays a critical regulatory role in its pathogenesis [21]. For instance, Han and Sabirzhanov et al. reported that miR-21 can protect neurons from apoptosis by activating the phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN)- V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (Akt) signaling pathway through suppressing PTEN expression [22, 23]. Sun et al. uncovered that miR-27a protected against TBI via suppressing forkhead box class O3a (FoxO3a)-mediated neuronal autophagy following TBI by inhibiting FoxO3a protein expression [24]. Our team previously demonstrated that miR-212-5p inhibited neuronal ferroptosis by targeting prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase-2 (Ptgs2) following TBI [25]. Based on the significant role of miRNA in the central nervous system (CNS), as well as the possible anti-ferroptosis effect of AMP, we introduced miRNA profiling and various validation experiments to explore the miRNA mechanisms through which the AMP exerts its protective role in a CCI mouse model.

Materials and methods

Animals

We used male C57 BL/6Jmice aged 10–12 weeks and weighing 20–23 g. The mice were housed in an animal facility that was approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, and maintained under a 12-h light/dark cycle at a temperature of 22 °C to 25 °C and 50% relative humidity. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the regulations of the Animal Care and Experimental Committee of Sichuan University and approved by the committee (Approval No. K2021024).

CCI model

In brief, the mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and then maintained at a 2% concentration before being mounted on a stereotaxic frame. A midsagittal incision was made in the scalp and periosteum under sterile conditions. A 4.5-mm diameter craniotomy was then performed posteriorly up to the coronal suture with a surgical drill, and a 3-mm flat hitting tip was vertically placed on the exposed dural surface for cortical impact. The impact speed of the CCI device was set to 5.0 m/s, with a depth of 2.0 mm and a dwell time of 100ms. After the impact, the bone window was covered with a sterile plastic film, and the skin was intermittently sutured and disinfected. For more details, please refer to Xiao et al. [25].

Morris water maze

The Morris water maze (MWM) was used to evaluate spatial memory performance as described previously [26–28]. Four trials (n = 5) were conducted per day, during which, mice were randomly assigned to start from one of four location (north, south, east, or west) and placed in the pool facing the wall. The mice had up to 90 s to find the submerged platform, and if they failed to do so, they were placed on the platform by the experimenter and allowed to remain there for 10 s. Mice were placed in a warming chamber for at least 4 min between trials. To control possible differences in visual acuity or sensorimotor function between groups, two trials were conducted using a visible platform raised 1 cm above the surface of the water. MWM consisted of a spatial exploration task conducted from day 7 to 13 (primarily assessing the animals’ learning and memory abilities) and a probe trial on day 13, following the spatial exploration task (assessing the animals’ memory retention). Additionally, swimming speed was recorded during the probe trial to evaluate motor function at a later post-injury time point. Data were excluded if mice died during experiment.

Modified neurological severity score

To evaluate the neurological function, the modified neurological severity score (mNSS) test was conducted according to previous study [29]. The tests (n = 6) were carried out at 6, 24, 48 and 72 h after CCI. The mNSS includes motor function (including muscle status and abnormal movement), sensory function (such as visual, tactile, and proprioceptive abilities), reflexes, and balance. One point is awarded if the mice are unable to perform the test or lack an expected reaction; thus, the higher the score, the more severe the injury (severe TBI: 13–18 scores; moderate TBI: 7–12 scores; mild TBI: 1–6 scores).

Rotarod test

Rotarod test (n = 5) was used to assess the acquisition of skilled behavior in mice following a previously described procedure [30]. The mouse was placed on the rotarod cylinder and the time for which the animal remained on the rotarod was measured. The speed was slowly increased from 4 to 40 rpm. If the animal fell off the rungs during a trial, it was immediately placed back on up to 5 times. A fall was recorded if the animal failed to remain on the rotating rod for 180 s. We conducted the Rotarod test immediately following the injury to assess the animals’ motor coordination and balance. The experiment was conducted five times, on days 0, 1, 3, 5, and 7 post-injury. The habituation time and daily schedule remained the same as for the initial test.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

On day 30 post-CCI, a MRI scan was performed using a 7 Tesla Bruker Biospec USR 70/30 MRI system (Bruker Biospin GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany). This imaging was specifically undertaken to assess the extent of brain injury. The scan sequence used was the T2-weighted RARE (Rapid Acquisition with Relaxation Enhancement), with the following parameters: a repetition time (TR) of 5209.436 ms and an echo time (TE) of 60 ms; the field of view (FOV) was set at 20 × 20 mm. The acquisition matrix was configured to 256 × 128, spanning 25 slices each 0.5 mm thick, with 8 averages and a RARE factor of 8. The extent of brain damage was quantified using the formula: Damage (%) = (Damage / Total brain volume) × 100%.

Intracerebroventricular injection

The miR-128-3p agomir and negative control (NC) were purchased from RiboBio (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China). On the 4th and 2nd day prior to TBI, mice were placed in the stereotaxic frame, followed by 10 µl of 5 nM miR-128-3p agomir or NC injected into the right lateral ventricle at a rate of 1 µl/min for 10 min. The syringe was positioned at the following coordinates: AP − 0.9 mm, ML + 1.0 mm, and DV − 2.0 mm.

Western blotting

Cortical tissues from isolated mice were extracted 48h after TBI, followed by rapid transfer to liquid nitrogen. The tissues were lysed using RIPA reagent (Beyotime, Haimen, Jiangsu, China) containing 1% PMSF (Beyotime, Haimen, Jiangsu, China), and the extracted total proteins were subsequently quantified using a BCA assay kit (Beyotime, Haimen, Jiangsu, China). Protein samples were separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS polyacrylamide gels, and then the antigens were electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P Transfer membrane, Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The next day, they were incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibody (1:10,000) for 1 h at room temperature and detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL) (Biosharp, China) and ECL chemiluminescent substrate (Ultra Sensitive) (Biosharp, China). NIH Image J software (Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to quantify the band density, with β-actin serving as a loading control.

Primary antibody: NFE2L2 (Proteintech, #16396-1-AP, 1:1000), NOX2 (Abcam, #ab129068, 1:1000), HSPB1 (Abcam, #ab32501, 1:1000), ALOX8 (Proteintech, #13073-1-AP, 1:1000), GPX4 (Abcam, #ab125066, 1:1000), SLC7A11 (Abcam, #ab37185, 1:1000), STEAP3 (Abcam, #ab151566, 1:1000), ACSL4 (Abcam, #ab155282, 1:1000) and ACTB(β-actin) (ZENBIO, #R23613, 1:5000).

Mouse cortical RNA-seq and data analysis

Cells were obtained from cortex of uninjured and injured mice following CCI at 3 h and 6 h, and the total RNA was extracted following the protocol as described previously [25]. Four replicate samples for each group. The quality of RNA samples and high-throughput sequencing were accomplished by Ouyi Biology Medical Science Technology Co. DESeq [31] was applied to screen for differentially expressed miRNAs between Sham and TBI samples after removing zero counts in all replicates. Differentially expressed miRNAs were identified between the two groups at a P value of < 0.05 and absolute log2 Fold Change ≥ 0.3. The quality of replicates was assessed by calculating the pairwise Spearman correlation coefficient. Meanwhile, the expression values of the differential miRNAs of the three sample (sham,3 h and 6 h) values normalized by fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) are presented as a heatmap and volcano map.

KEGG and GO analysis

The target genes of miRNAs were predicted using the Miranda (version 3.3a) [32]. Enrichment analysis of target genes for differential miRNAs is based on the Gene Ontology (GO)-based functional enrichment and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). They were used to analyzed the differential genes screened from these two groups and their role in signaling pathways to explore their function. GO and KEGG pathway analysis were carried out using the online database String (version 10.5) with the default mouse genome as background and R package clusterProfiler (version 3.12.0). And Benjamini-Hochberg multiple tests were applied for adjustment of multiple testing. Functional category terms with an FDR of no more than 0.05 were regarded as significant categories.

Cell culture

The immortalized mouse hippocampal neuron line HT22 was purchased from Honsun Biological Technology (Shanghai, China) and were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Hyclone, Utah, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, CA, USA) and 1% penicillin‒streptomycin (Gibco, CA, USA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Cell transfection

The mmu-miR-128-3p mimic (5’-UCACAGUGAACCGGUCUCUUU-3’), mmu-miR-128-3p inhibitor (5’-AAAGAGACCGGUUCACUGUGA-3’) and its negative control (mmu-miR67-3p, 5’-UCACAACCUCCUAGAAAGAGUAGA-3’) were purchased from Jinmai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Slc7a11 siRNA#1(SS: GCAGCGACUGCUGUGAUAUTT, AS: AUAUCACAGCAGUCGCUGCTT), siRNA#2(SS: GCAGUGAUGGUCCUAAAUATT, AS: UAUUUAGGACCAUCACUGCTT) and Negative Control were purchased from Genepharma Co. (Shanghai, China). The HT22 cells were dissociated using 0.25% trypsin (Gibco, New York, USA) and counted with a Neubauer hemocytometer. Transfections were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Briefly, the miR-mimic (20 µM), inhibitor (20 µM) or siRNA (20 µM) and transfection reagent were diluted in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) serum-free medium. After mixing and incubating at room temperature for 15 min, the mixture was transfected into HT-22 cells. This transfect solution was added into the culture plates for 6 h of transfection, followed by replacing with the complete DMEM medium.

Mitotracker staining

To assess mitochondrial morphology, cells were seeded in 24-well glass-bottom culture plates suitable for microscopy. Following experimental treatments, HT22 cells were stained with Mitotracker Red CMXRos (Product No. M7512) from Invitrogen to visualize mitochondria. A stock solution was prepared according to the recommended concentration of 1 mM. For use, the stock solution was diluted 1:5000 in DMEM to prepare the working solution. Cells were then incubated with the Mitotracker-containing working solution for 30 min at 37 °C. After staining, cells were gently washed two to three times with pre-warmed PBS at 37 °C. Complete DMEM medium with 10% FBS was added to cover the cells in preparation for imaging. Observations and image acquisition were performed using the Zeiss LSM 810 confocal microscope in Airyscan mode (Ex/Em 579/599 nm). Mitochondrial morphology was analyzed by randomly acquiring five fields of view per group using a 63x objective. The analysis was performed using the MiNA plugin for ImageJ (Version 1.54, NIH, USA), which analyzes mitochondrial network morphology and structure [33]. The average cellular mitochondrial length was selected as the parameter for statistical analysis and comparison.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation was detected using BODIPY™ 581/591 C11 (D3861; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, cells adherently cultured were incubated directly with 2 µM BODIPY™ 581/591 C11 for 30 min at 37 °C. Confocal microscopy was used to assess fluorescence, employing a 20x objective lens on an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Japan). The laser parameters were as follows: for Cy2, an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and a detection range of 500–540 nm; for Cy3, an excitation wavelength of 561 nm and a detection range of 570–620 nm.

Fe (II) detection

To detect intracellular Fe (II), FerroOrange (no. F374, Dojindo, Japan) was utilized according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, after removing the culture medium, the harvested cells were washed twice with PBS and then co-incubated with a 1 µmol/L FerroOrange working solution at 37 °C for 30 min. After the incubation, the cells were washed with PBS. Fluorescent images were obtained using a Keyence BZ-X800 fluorescence microscope (Keyence, Japan) with the TRITC filter (Ex: 545/25 nm, Em: 605/70 nm). The signal intensity per cell was measured with ImageJ (Version 1.54, NIH, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

HT-22 cells under different culture conditions were washed with 1×PBS three times and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Then, the cells were washed with 1×PBS three times and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 20 min. Following 1×PBS washing three times, the cells were blocked with 3% BSA for 60 min and incubated with the primary antibody SLC7A11 (#ab37185, 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, USA) at 4℃ overnight. The next day, the cells were incubated with the secondary anti-rabbit antibody fluorescein isothiocyanate (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, USA) and in the dark at room temperature for 60 min. Following 1×PBS washing three times, the cells were stained with DAPI and mounted with fluorescent mounting media. Imaging was performed using two channels: DAPI (blue) and FITC (green), and the cells were observed under an EVOS FL Auto 2 fluorescence microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The signal intensity per cell was measured with ImageJ (Version 1.54, NIH, USA).

Reporter plasmid construction and luciferase reporter assay

The 3’-UTR of Slc7a11 mRNA was gained from UCSC (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and the seed sequence targeted by miR-128-3p was predicted by using TargetScanMouse8.0 (http://www.targetsan.org/vert_72/). All the work to insert the 3′-UTR wild-type sequence or mutant sequence of Slc7a11 to pmirGLO Dual-Luciferase miRNA Target Expression Vector (pmirGLO) were accomplished by Jinmai Biotechnology Co. Ltd. The HT-22 cells were coinfected with empty (pmirGLO), wild-type (pmirGLO-WT-Slc7a11) or mutant-type (pmirGLO-MT-Slc7a11) reporter vectors and miR-128-3p mimics by Lipofectamine 3000 reagent. After 24 h transfection, cells were harvested and examined with the dual-luciferase reporter assay (Yeasen, Shanghai, China). Three independent experiments were conducted, each group consisting of five replicate wells of cells, and Renilla luciferase was used to normalize Firefly luciferase.

MDA assay

The MDA levels in both the cerebral cortex and HT-22 cell samples were measured using the Lipid Peroxidation (MDA) Assay Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The procedure was carried out in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the samples were weighed and homogenized in the RIPA buffer (Solarbio, Nanjing, China) containing 1% phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) on ice for 20 min, and then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C to collect the supernatant. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the BCA assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The MDA in the sample reacted with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) to generate an MDA-TBA adduct, which was colorimetrically quantified at OD = 532 nm. The MDA levels were normalized to the protein concentration of tissue or cell samples.

GSH assay

The levels of reduced GSH in the cerebral cortex and cell samples were determined using the GSH and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) Assay Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the total GSH level (GSH + GSSG) was initially determined by converting GSSG to GSH. Following the removal of GSH in the protein sample using a 1 mol/L 2-vinylpyridine solution, the GSSG level was then quantified using the same method as for total GSH detection. Detection was performed by measuring the absorbance value at a wavelength of 412 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy HT, CA, USA). The GSH level was calculated by subtracting the amount of GSSG from total GSH, as described previously [34].

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

The RNA was extracted from cerebral cortex and HT-22 cells by using TRizol reagent (Invitrogen, California, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The reverse transcription of miRNA was achieved with TransScript® miRNA First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). The qRT-PCR of miRNA was performed using TransScript®Green miRNA Two-Step qRT-PCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). The reverse transcription of mRNA was performed using Hifair® III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR (gDNA digester plus) (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) and qRT-PCR was conducted applying Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Low Rox) (Yeasen, Shanghai, China). For the animal experiment, each group consisted of five samples, and the cerebral cortex was obtained 48 h post-injury. As for the cell measurements, each group was composed of three samples. The data were calculated using the formula 2–ΔΔCT. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward Primer (5’-3’) | Reverse Primer (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| Gpx4 | GTGTAAATGGGGACGATGCC | CCTTCTCTATCACCTGGGGC |

| Acsl4 | AGCGTTCCTCCAAGTAGACC | GTCCTTCGG-TCCTAGTCCAG |

| Nox2 | TTG-GGGCTGAATGTCTTCCT | AGTGCTGACCCAAGGAGTTT |

| Slc7a11 | TCTGACGATGGTGATGATCT | GGGATGAAGAGAGGCACCTT |

| Nfe2l2 | TGCCCACATTCCCAAACAAG | ATATCCAGGGCAAGCGACTC |

| Hspb1 | GAAAGGCAGGACGAACATGG | TGGAGGGAGCGTGTATTTCC |

| Steap3 | TGGGCTGAGGAAGAAGTCTG | AGGTGAGTGTGTGCATTGTG |

| Alox8 | CTCTGCGATGAAGAATGCCA | GTGGGAATGGGTCAGAAGGA |

| β-Actin | GTGGGAATGGGTCAGAAGGA | GGAGCCCTTTGACTTTCAGC |

| miR-128-3p | UCACAGUGAACCGGUCUCUUU | AAAGAGACCGGUUCACUGUGA |

| U6 | CGATTAGAGACATAGCAAGC | GCGTTTAAGCACTTCGCAAGGT |

Perl’s prussian blue staining

Iron accumulation in cells or cerebral cortex was detected using the Prussian Blue Iron Stain Kit (Enhance With DAB) (Solarbio, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Paraffin sections were hydrated routinely, while cells were washed three times by 1×PBS and fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min. The slices were then incubated with Perl’s Working Solution. Afterward, the Incubation Working Solution (1:9) was dropped on the tissue or cells. And then the Enhanced Working Solution (C1: C2: 1×PBS = 1:1:18) was added on the tissue or cells. Finally, the slices stained with Redyeing Solution. For more details, please refer to Bao et al. [35]. The number of positive cells was counted in the Image J software (Version 1.54, NIH, USA) after 6 randomly selected fields of view.

Nissl staining

The test was similar to the ref [36]. Paraffin sections were dewaxed routinely with xylene and hydrated with gradient alcohol while cells were washed three times by 1×PBS and fixed by PFA for 20 min. The sections were soaked in Nissl Staining Solution (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and then rinsed with ddH2O for three times and dehydrate in gradient ethanol, transparent by xylene and seal with resinene. Each slice was examined microscopically at 40× magnification, with six randomly selected visual fields chosen for observation. Injured cells were identified by characteristics such as neuronal edema, increased intercellular space, and a reduction in Nissl bodies in the cytoplasm [37]. For detailed quantitative methods, please refer to Ooigawa et al. [38]. Quantification of each slice was performed using ImageJ software (Version 1.54, NIH, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A Student’s t-test was used to compare means of the two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparisons among multiple groups and post-hoc Tukey’s test was applied to identify specific differences between groups. The data of escape latency were analyzed using repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. All data analysis was done using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A value of p < 0.05 is considered to be statistically significant.

Results

AMP provides cortical protection and alleviates cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction in mice following CCI

Mice were divided randomly into four groups. Sham group and TBI group were treated with normal saline. TBI-AMP (TBI-A) group received CCI and treated with AMP. Sham-AMP (Sham-A) group received sham operation and AMP administration. The effects of AMP on cognitive and motor function of mice were assessed using mNSS [39], Rotarod test [40], and MWM [41], respectively. MRI examinations were conducted on mice 30 days post-injury to observe the area of brain lesions and assess the extent of injury repair (Fig. 1a). As shown in Fig. 1b, the mNSS scores significantly increased in mice subjected to TBI, suggesting impaired neural functions. Notably, the TBI-A group showed lower mNSS scores than the TBI group on post-injury 6 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h, demonstrating that AMP treatment partly attenuates neural impairments in mice following TBI. In order to estimate motor coordination ability [40], we performed the Rotarod test after treatment. We found that TBI group mice had shorter stay time on the rotarod compared to the Sham group. However, AMP treatment extend the stay time of the TBI-AMP group mice compared to the TBI group mice (Fig. 1c), indicating that AMP can improve motor coordination disability of mice following TBI.

Fig. 1.

AMP alleviates cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction in mice following CCI and also provides cortical protection (a) Schematic diagram illustrating the strategy to evaluate the therapeutic effects of AMP on cognitive and motor functions, along with MRI scans of injury areas in mice after CCI. (b) mNSS for each group of mice, with mean scores plotted from 0 to 72 h. The mNSS data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA for repeated measures. Data were collected from six mice per group. Statistical significance is indicated by *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p < 0.001 and ****p = < 0.0001. (c) Rotarod test results for each group of mice, showing the mean latency plotted from the 0th to the 7th day. Latency data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA for repeated measures. Data from six mice in each group were used. Statistical significance is indicated by *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p < 0.001 and ****=p < 0.0001. (d) MWM results for each group of mice, plotting mean escape latency from the 7th to the 13th day. Escape latency data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA for repeated measures. Data from six mice in each group were used. Statistical significance is indicated by *=p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p < 0.001 and ****=p < 0.0001. (e) Typical motion trails for each group in the spatial probe test of the MWM. (f-g) The speed in the spatial probe test and the frequency of crossing quadrant where the platform located on the 13th day Data from six mice in each group were calculated, significant differences were obtained by one-way ANOVA followed by Post hoc comparisons with Tukey’s test, and the results are expressed as * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01. (h) T2-weighted image sequences were used to assess the area of brain lesions in mice on day 30 post-CCI. (i) The proportion of brain lesion area to total brain volume was calculated from MRI results, for each group, n = 6 and the values are presented as the mean ± S.D. Significant differences were obtained by Student’s t-test followed by Post hoc comparisons with Tukey’s test, and the results are expressed as****=p < 0.0001. CCI, controlled cortical impact; MWM, Morris Water Maze; mNSS, modified neurological severity score; AMP, aminophylline; TBI, traumatic brain injury; TBI-A, traumatic brain injury- aminophylline; Sham-A, Sham-aminophylline

To evaluate the spatial learning and memory abilities of mice, both training trials and probe trials were performed using the Morris Water Maze (MWM) [42]. The results showed that the TBI group remarkably prolonged the latencies on days 7 to 13 compared to Sham group, indicating that TBI impaired spatial learning ability of mice. The AMP treatment shortened the latencies on the day 12 and 13 compared to TBI group (Fig. 1d), suggesting that AMP relieves learning impairment caused by TBI. The probe trials showed that the TBI group took a complex route to the quadrant where platform located, whereas mice in TBI-A group were able to arrive more quickly at the platform (Fig. 1e). Moreover, the swimming speed of TBI group was significantly lower than that of Sham group, but this change was attenuated after AMP treatment (Fig. 1f). By comparison, post-injury AMP treatment exhibited more enhanced frequency of passing through the platform quadrant than the TBI group (Fig. 1g), indicating that AMP prevented spatial learning and memory dysfunction in mice subjected to TBI. MRI results at 30 days post-injury showed that, compared to the TBI group, the lesion area in the TBI-A group was reduced, indicating that AMP has a protective effect on cortical tissue (Fig. 1h and i). Altogether, these findings demonstrate that AMP not only attenuates cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction following TBI but also provides protection to the cortical tissue in mice.

AMP inhibits ferroptosis in TBI mice

To further investigate whether AMP inhibits neuronal ferroptosis in TBI, we detected the expression changes of ferroptosis-related genes at the mRNA and protein levels 48 h after injury. Previous studies have demonstrated that acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4), arachidonate 8-lipoxygenase (ALOX8), NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) and six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3(STEAP3)exacerbate ferroptosis, while glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), nuclear factor, erythroid derived 2, like 2 (NFE2L2), SLC7A11 and heat shock protein family B (small) member 1 (HSPB1) prevent it [43–51]. Here we found that TBI led to an increase in the mRNA expression levels of Alox8, Nox2, Nfe2l2, Hspb1, Steap3, and Gpx4 (Fig. 2a). Additionally, we noted an elevation in the protein expression of SLC7A11 48 h post-injury (Fig. 2b). This finding aligns with our previous research [25]. Upon administering AMP treatment, there was a significant rise in both mRNA and protein levels of HSPB1, SLC7A11, GPX4, and NFE2L2 (Fig. 2a-b). Interestingly, the treatment also reversed the injury-induced upregulation of ACSL4, ALOX8, STEAP3 and NOX2 (Fig. 2a-b). These results suggest that AMP may play a role in inhibiting neuronal ferroptosis in the cortex of TBI mice.

Fig. 2.

AMP inhibits ferroptosis in TBI mice. (a) The relative mRNA expression of Acsl4, Alox8, Hspb1, Slc7a11, Steap3, Gpx4, Nf2l2 and Nox2 in TBI, TBI-A and sham groups 48 h post-injury, and β-actin was used as a normalization control (n = 5). The data were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCT method. (b) Protein levels of ferroptosis-related genes post-CCI. Cortical expression of ACSL4, ALOX8, HSPB1, SLC7A11, STEAP3, GPX4, NFE2L2, and NOX2 were measured in the TBI, TBI-AMP, and sham groups at 48 h, and the results are presented in bar graphs. (c-d) MDA (c) and GSH (d) levels in the ipsilateral cortex of mouse in each group. Data from five mice in each group were calculated. (e-f) Representative Perl’s staining (e) and Nissl staining (f) pictures of the ipsilateral cortex. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed with the Student’s t-test, with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 indicating statistical significance. TBI, traumatic brain injury; TBI-A, traumatic brain injury-aminophylline; Sham-A, Sham-aminophylline; MDA, malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione

In order to validate the ferroptosis-inhibiting effect of the AMP, we next measured MDA and GSH [52]. We found that the level of MDA was increased and GSH production was depressed after TBI, whereas AMP reversed the results (Fig. 2c and d). Perl’s staining and Nissl staining further confirmed that TBI caused iron overload and neuronal injury. As expected, AMP injection restored this alternation (Fig. 2e and f). Taken together, these results provide evidence that AMP prevents ferroptosis in the cerebral cortex following TBI.

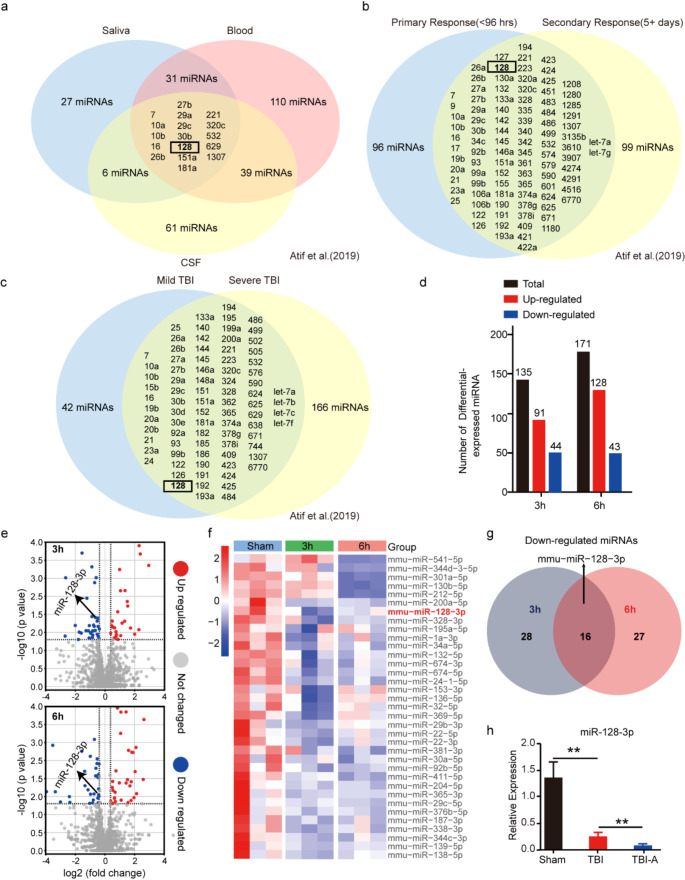

AMP suppresses miR-128-3p expression to alleviate neuronal ferroptosis following TBI

To explore the miRNA-related mechanisms underlying ferroptosis induced by TBI, we first analyzed 14 clinical studies of human TBI patients included in the review by Atif et al., all of which examined miRNAs in the biofluids of the patients [53]. These studies encompassed different biofluids (CSF, blood, and saliva), various periods post-TBI, and different severity levels of TBI. Among the findings, 17 miRNAs showed significant changes across all three biofluids following TBI (Fig. 3a), 96 miRNAs demonstrated significant alterations during the primary response (< 96 h) and secondary response (5 + days post-TBI) (Fig. 3b), and 83 miRNAs exhibited significant changes between mild and severe cases of TBI (Fig. 3c). Notably, miR-128 consistently showed significant alterations across these studies, indicating its potential as a biomarker for TBI. However, miR-128 levels were found to increase in the blood of TBI patients but decrease in their saliva [53]. Integrating various studies, Atif et al. identified a general decrease in miR-128 levels following traumatic brain injury (TBI). However, they did not thoroughly investigate the functional role of miR-128 after TBI [53]. To clarify the mechanisms by which miRNA influences ferroptosis in the mouse cortex following TBI, we extracted total RNA from the injured cerebral cortex at 3 h and 6 h post-TBI, as well as from the corresponding region in the Sham group. Subsequently, we performed miRNA sequencing. Compared to the Sham group, 44 miRNAs decreased and 91 miRNAs increased at 3h after TBI. At 6 h post-injury, CCI resulted in the downregulation of 43 miRNAs, and the upregulation of 128 miRNAs (Fig. 3d). To analyze the biological pathways potentially involved with the altered miRNAs following TBI, we conducted KEGG and Gene Ontology (GO) analyses on these miRNAs (Fig.S1). KEGG analysis showed that these miRNAs are involved in multiple pathways, mainly including the Wnt signaling pathway, Hippo signaling pathway, phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt signaling pathway, and adenosine 5’-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway (Fig.S1a and Fig.S1b), which have been reported to be involved in ferroptosis previously [54–57]. Additionally, the GO analysis demonstrated that these miRNAs participate in the regulation of oxidative stress, hypoxia, and ferric iron metabolism at both 3h and 6 h (Fig.S1c and S1d). Among these miRNAs, we concentrated on those with consistent differential expression at both time points and conducted a detailed literature review on them. Notably, miR-128-3p—a mature sequence of miR-128—has been reported to be enriched in the brain tissue following traumatic brain injury [58], and has been proven to promote oxidative stress, impair mitochondrial function and exacerbate intracellular iron accumulation leading to ferroptosis [59, 60], was down-regulated at both 3h and 6 h timepoints after the injury (Fig. 3e-g). We further conducted qRT-PCR experiments to investigate the expression changes of miR-128-3p at a later time point (48 h) after brain injury. These experiments validated the results of our analysis and corroborated the downregulation of miR-128 observed in the analysis of 14 human TBI clinical studies. Interestingly, we observed that this change was amplified when treated with AMP (Fig. 3h). Our literature review revealed that the downregulation of miR-128-3p might play a protective role in neuronal death following TBI [59–61]. Furthermore, in the pathway enrichment analysis of our TBI sequencing data (Figure S1), we observed significant changes in ferroptosis-related pathways, which led us to propose this hypothesis: Under TBI conditions, miR-128-3p is downregulated to counteract ferroptosis induced by the insult. Additionally, AMP reduces miR-128-3p expression, thereby enhancing this anti-ferroptosis effect.

Fig. 3.

AMP suppresses miR-128-3p expression to alleviate neuronal ferroptosis following TBI (a) Venn diagram illustrates the distribution of 291 miRNAs detected in various biofluids. These miRNAs are found in saliva (blue), blood (red), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF, yellow), with overlaps indicating miRNAs identified in multiple biofluids. The data were sourced from Atif et al. [53]. (b) Venn diagram categorizes these 291 miRNAs by the timing of their response. miRNAs in the blue circle are from biofluid samples (blood, saliva, or CSF) collected within 96 h post-injury, while those in the yellow circle are identified at least 5 days post-injury. The data were sourced from Atif et al. [53]. (c) Venn diagram organizes the 291 miRNAs by the severity of brain injury (mild or severe). miRNAs linked to mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) appear in blue, whereas those associated with severe TBI are in yellow. Overlaps represent miRNAs identified in studies of both mTBI and severe TBI. The data were sourced from Atif et al. [53]. (d) The number of differentially expressed miRNAs in the mice ipsilateral cortex at 3 h and 6 h after TBI. (e) Volcano plot for differentially expressed miRNAs in the ipsilateral cortex at 3 h and 6 h after TBI. (f) Heatmap of down-regulated miRNAs identified by RNA-seq. (g) Venn diagram of down-regulated miRNAs in the ipsilateral cortex at 3 h and 6 h after TBI. (h) qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of miR-128-3p in each treatment group. Data from five mice in each group were calculated. U6 was used as normalization control and data were expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed with the student’s t-test, **p < 0.01

To investigate the role of miR-128-3p downregulation in neuronal ferroptosis, we transfected HT22 cells with miR-128-3p inhibitor/NC and induced ferroptosis using Erastin (Fig. 4a). Validation experiments showed that transfection with the inhibitor significantly reduced miR-128-3p levels in HT22 cells, achieving a high knockdown efficiency (Fig. 4b). Notably, compared to the NC group, miR-128-3p knockdown resulted in lower MDA levels and higher GSH levels in Erastin-induced HT22 cells (Fig. 4c-d), indicating an enhancement in cellular antioxidant capacity. Additionally, Nissl staining revealed that the miR-128-3p inhibitor group exhibited more uniform distribution of Nissl bodies and more intact cell structures (Fig. 4e-f), suggesting that miR-128-3p knockdown protects neuronal integrity. Iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation are key features of ferroptosis. Perls’ blue staining results demonstrated that, after miR-128-3p knockdown, the number of cells with iron deposits was significantly lower compared to the NC group (Fig. 4g-h). FerroOrange iron ion staining also showed reduced iron content in HT22 cells following miR-128-3p knockdown (Fig. 4i-j). Furthermore, BODIPY C11 lipid peroxidation staining indicated a lower degree of lipid peroxidation in HT22 cells with miR-128-3p knockdown (Fig. 4k-l). These results suggest that downregulation of miR-128-3p alleviates neuronal ferroptosis, thereby exerting a protective effect on neurons.

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of miR-128-3p alleviates ferroptosis in HT22 cells. (a) Schematic diagram illustrating the transfection procedure and subsequent examinations of MDA and GSH levels, and staining. (b) qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of miR-128-3p in each treatment group (n = 3). BLANK, cells without transfection; NC, cells transfected with miR-67-3p (negative control); miR-128-3p inhibitor, cells transfected with miR-128-3p inhibitor. The data were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCT method with U6 as the normalization control. (c-d) Levels of MDA (c) and GSH (d) in erastin-induced HT-22 cells post-transfection with miR-128-3p (n = 3). (e-f) Representative images of Nissl staining and corresponding bar charts showing the number of damaged cells. (g-h) Representative images of Perl’s staining and corresponding bar charts showing the number of positive cells. (i-j) Representative images of FerroOrange staining (yellow: Fe²⁺) and corresponding bar charts showing FerroOrange fluorescence intensity. (k-l) Representative staining results of BODIPY™ 581/591 C11 (lipid peroxidation sensor) (red: reduced state; green: oxidized state). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed using the Student’s t-test. Significance levels are indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. NC + E: negative control + Erastin; Inhibitor + E: miR-128-3p inhibitor + Erastin

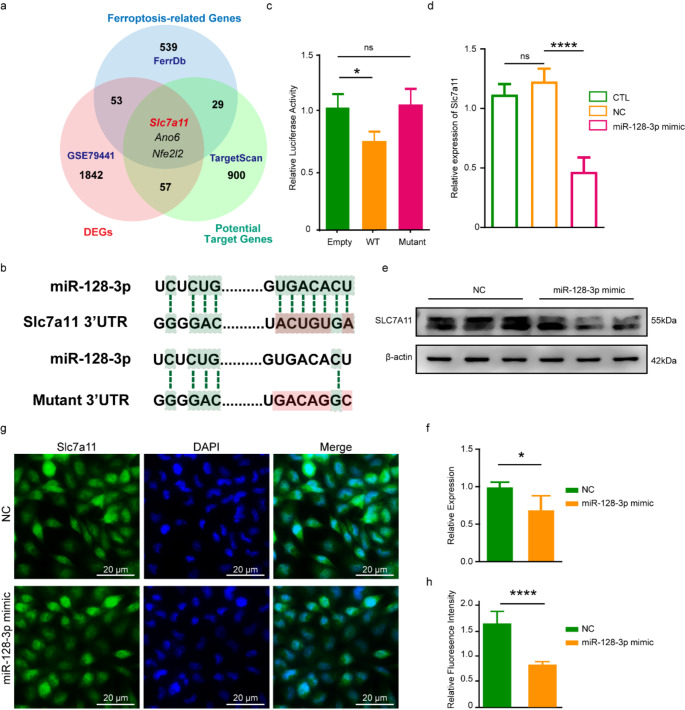

AMP ameliorates ferroptosis of cortex neurons following TBI by targeting miR-128-3p/ Slc7a11 axis

To identify the target of miR-128-3p in ferroptosis, we predicted genes with potential binding sites of miR-128-3p using bioinformatics tool TargetScanMouse8.0 (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/) and found 988 possible targets (Table S1). We took intersection of the above genes and the genes known to be involved in ferroptosis (Driver/Suppressor/Marker/Unclassified gene) screened out using FerrDb (http://www.zhounan.org/ferrdb/current/) (Table S2), as well as mRNAs that are differentially expressed following TBI acquired from the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo;GSE79441) (Table S3) [25]. 3 genes-SLC7A11, Anoctamin 6 (ANO6) and NFE2L2, fell into the intersection (Fig. 5a). We focused on SLC7A11 because it plays a crucial role in the ferroptosis pathway, yet its regulation by miRNAs in the context of TBI has been insufficiently explored.

Fig. 5.

miR-128-3p directly targets SLC7A11. (a) Schematic diagram outlining the strategy to identify the target gene of miR-128-3p. (b) Sequence alignment of miR-128-3p with the 3′-UTR of SLC7A11. The seed sequence of miR-128-3p and its binding sites within the 3′-UTR are highlighted in green. (c) Luciferase assay results demonstrating miR-128-3p targeting of SLC7A11 in HT-22 cells (n = 5). “Empty” refers to cells transfected with the pmirGLO vector alone; “WT” to cells with pmirGLO-WT-SLC7A11; and “Mutant” to cells with pmirGLO-MT-SLC7A11. (d) qRT-PCR results of Slc7a11 across different groups. β-Actin was used as a normalization control and data was expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed with the Student’s t-test. (e-f) Western blot results (e) and statistical analysis (f) for SLC7A11 in groups transfected with miR-128-3p or NC. (g-h) Immunofluorescence staining for SLC7A11 expression (g) and quantitative analysis of the signal (h). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed using the Student’s t-test, with *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001

We conducted a dual-luciferase activity assay in the HT22 to validate the direct regulation of miR-128-3p onto Slc7a11 (Fig. 5b). Results showed that the luciferase activity of pmirGLO Dual-Luciferase miRNA Target Expression Vector (pmirGLO)-wild type (WT)-Slc7a11 vector was significantly decreased upon co-transfection with miR-128-3p mimic in the HT-22 cells, whereas the administration of pmirGLO-mutant (MT)-Slc7a11 vector had no effect on the luciferase activity (Fig. 5c). These findings demonstrated that the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of Slc7a11 is a direct target of miR-128-3p. To further confirm the direct regulatory effect of miR-128-3p on SLC7A11, we examined the expression of SLC7A11 in the HT-22 cells, at the mRNA and protein level. We found a significant down-regulation of SLC7A11 in the cells transfected with the miR-128-3p (Fig. 5d-h). These findings demonstrate that miR-128-3p directly targets and down-regulates SLC7A11 in neurons, which could be the mechanism through which miR-128-3p promotes neuronal ferroptosis.

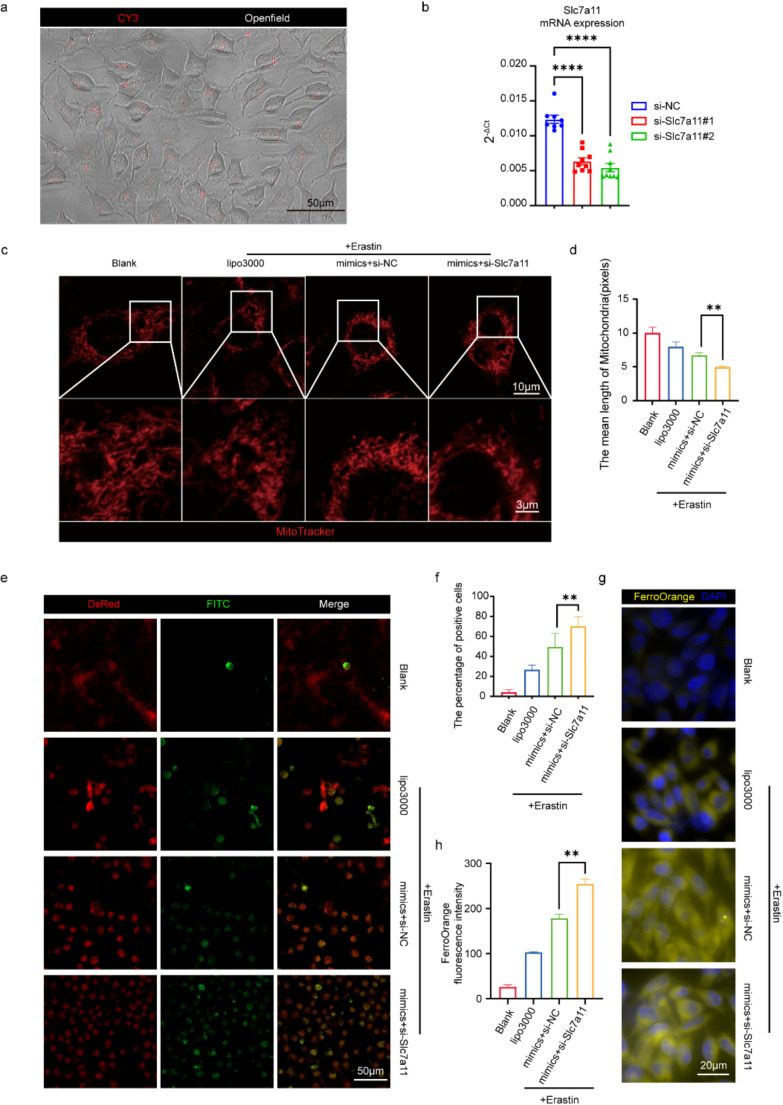

To verify whether miR-128-3p modulates ferroptosis by negatively regulating the expression of SLC7A11, we employed siRNA to knock down SLC7A11 expression in the HT22 cell line. Using the mRNA sequence of Slc7a11, we designed two CY3-labeled siRNAs: si-Slc7a11#1 and si-Slc7a11#2. After transfecting HT22 cells for 48 h, microscopic observation showed that nearly all cells exhibited CY3 signals in the cytoplasm, indicating a transfection efficiency suitable for subsequent analyses (Fig. 6a). qPCR analysis of the NC group, si-Slc7a11#1 group, and si-Slc7a11#2 group revealed that both si-Slc7a11#1 and si-Slc7a11#2 significantly knocked down Slc7a11 expression, with reductions below 50%. si-Slc7a11#2 demonstrated the most effective knockdown and was used in subsequent experiments (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

miR-128-3p Modulates Neuronal Ferroptosis by Down-regulating Slc7a11. (a) Representative image showing the distribution of CY3 signal within HT22 cells 48 h post-transfection with si-Slc7a11. (b) qRT-PCR analysis of Slc7a11 mRNA levels in cells transfected with si-Slc7a11#1, si-Slc7a11#2, and NC (negative control), using β-Actin as an internal reference. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed using the Student’s t-test, with ****p < 0.0001. (c-d) Representative MitoTracker staining images and bar charts showing the average chromosome length for four groups: Blank, Lipo3000 + Erastin, miR-128-3p mimic + si-Slc7a11 + Erastin, and miR-128-3p mimic + si-NC + Erastin (red: mitochondria). (e-f) Representative images and bar charts quantifying oxidized positive cells of BODIPY™ 581/591 C11 staining, a lipid peroxidation sensor, showing reduced cells in the DsRed channel (red) and oxidized cells in the FITC channel (green). (g-h) FerroOrange staining and bar charts showing FerroOrange fluorescence intensity across four groups, indicating Fe²⁺ (yellow) in HT22 cells

Additionally, we induced ferroptosis in Slc7a11-KD HT22 cells by adding Erastin and assessed mitochondrial morphology, the proportion of oxidized cells, and divalent iron ion deposition 24 h post-treatment using MitoTracker, BODIPY, and FerroOrange, respectively. This was to analyze whether Slc7a11-KD could exacerbate ferroptosis induced by the miR-128-3p mimic. Mito Tracker staining indicated more severe mitochondrial damage in the Slc7a11-KD group, with normal rod-like structures transforming into punctate mitochondria and a reduced number of mitochondria, suggesting that Slc7a11-KD intensified mitochondrial damage in HT22 cells (Fig. 6c-d). BODIPY staining showed a higher density of oxidized cells in the Slc7a11-KD group, indicating increased oxidation in HT22 cells (Fig. 6e-f). FerroOrange probes detected more concentrated divalent iron signals in the cytoplasm of Slc7a11-KD group cells, suggesting more severe cytoplasmic iron deposition (Fig. 6g-h). These results confirm that SLC7A11 is a key gene through which miR-128-3p regulates ferroptosis.

To study whether AMP exerts a neuroprotective effect by suppressing miR-128-3p/ Slc7a11 axis, we introduced the gain of function study, we injected miR-128-3p agomir into the right ventricle of mice prior to the injury [62]. We divided these mice into four groups: Sham group, TBI group, TBI-A group and TBI-AMP-miR-128-3p agomir (TBI-A-Agm) group. TBI-A-Agm group was injected miR-128-3p agomir on the fourth and second day before the TBI. We treated TBI-A group and TBI-A-Agm group with AMP by intraperitoneal injection, while Sham and TBI group with normal saline on the day 0 and day 1 after TBI. We examined Slc7a11 expression in the cerebral cortex of mice using qRT-PCR, observed the damage through transmission electron microscope (TEM) and Nissl’s staining on the day 2 after TBI, and assessed neurological function by MWM on the days 7 to 12 (Fig. 7a). We observed that AMP treatment enhanced Slc7a11 mRNA expression, while miR-128-3p overexpression attenuated this effect (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, TEM scanning results (Fig. 7c) revealed that, in the cerebral cortex of the TBI group, the nucleus was nearly intact while the mitochondrial ridges were reduced or even disappeared. The outer membrane of the mitochondria was broken and wrinkled, and the mitochondrial was darkened. In the TBI-A group, the nucleus, and the mitochondria of the injured cortex were relatively normal, even though the cell membrane was slightly injured. When treated with miR-128-3p agomir, although the nucleus of the cerebral cortex remains normal, the mitochondrial membrane and crest were slightly swollen. Nissl staining results indicate that TBI led to a reduction in the number of Nissl bodies in cortical neurons. However, AMP administration mitigated this effect, allowing for the observation of Nissl bodies in the neurons. Conversely, the treatment with miR-128-3p agomir negated the therapeutic effects of AMP. In the TBI-A-Agm group, the extent of neuronal damage was similar to that in the TBI group, with no discernible Nissl bodies observable (Fig. 7d). These results demonstrated that the anti-ferroptosis effect of AMP in TBI was blocked by excessive miR-128-3p. These in vivo findings further supported that AMP ameliorates neuronal ferroptosis by targeting miR-128-3p/Slc7a11 axis.

Fig. 7.

AMP ameliorates ferroptosis of cortex neurons following TBI by targeting miR-128-3p/Slc7a11 axis. (a) Schematic diagram of strategy to assess the effects of AMP on cognitive impairment and motor dysfunctions in mice following CCI by miR-128-3p/Slc7a11 axis and intracerebroventricular injection site. (b) The relative mRNA expression of Slc7a11 in sham, TBI, TBI-A and TBI-A-Agm groups (n = 3). β-Actin was used as a normalization control. (c) Representative TEM scanning pictures of the ipsilateral cortex. (d) Representative Nissl’s staining pictures of the ipsilateral cortex. (e) MWM test (n = 5), mean escape latency for each group was plotted during the 7th to 11th day. Data of escape latency are performed using two-way ANOVA for repeated measures. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (TBI vs. TBI-A), and **p < 0.01 (TBI-A vs. TBI-A-Agm). (f-g) The speed (f) and the typical motion trail (g) of each group in the spatial probe test. (h) The frequency of crossing quadrant where the platform located on the 12th day. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. Significant differences were obtained by one-way ANOVA followed by Post hoc comparisons with Tukey’s test, and the results are expressed as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. TBI-A-Agm, traumatic brain injury-aminophylline-miR-128-3p agomir, TEM, transmission electron microscope

As a result, the MWM test showed that pre-treatment with miR-128-3p agomir before AMP administration remarkably prolonged the latencies of mice on days 9–11 (Fig. 7e), decelerated the swimming speed (Fig. 7f), increased the swimming distance (Fig. 7g), and reduced the frequency of passing through the quadrant (Fig. 7h) compared with the TBI-A group. These results demonstrated that miR-128-3p blocked the memory and learning improvement in TBI treatment.

In conclusion, our study shows for the first time that miR-128-3p is a critical regulator of neuronal ferroptosis in which Slc7a11 is the direct target. Our study also suggests that AMP alleviates the ferroptosis of cortex neurons and improves the neurological outcomes of TBI, potentially involving the modulation of the miR-128-3p/Slc7a11 axis.

Discussion

In this study, we firstly report that AMP can be a potential treatment for TBI regarding its anti-ferroptosis effect and its role in ameliorating neurological dysfunction in experimental TBI animals. We also demonstrate that the underlying mechanism through which the AMP exerts these neuroprotective effects is the inhibition of miR-128-3p and the subsequent rehabilitation of SLC7A11. To the best of our knowledge, these anti-ferroptosis effects of AMP and the related miRNA mechanisms have not been reported in the literature.

Following TBI, the body activates protective mechanisms, which involve the upregulation or downregulation of specific genes and pathways to mitigate the detrimental effects of the injury. Further modulation of these genes and pathways can promote repair or improve the negative consequences of the injury, thereby facilitating recovery of both motor and cognitive functions [63]. In our study, we observed a reduction in miR-128 levels after TBI. A review of the literature revealed that miR-128 is highly expressed in the brain and plays a crucial role in neuronal plasticity. Notably, both animal and in vitro studies have shown that inhibition of miR-128-3p reduces infarct volume and neuronal cell death induced by ischemic stroke, providing neuroprotective effects [64]. However, it has not yet been reported whether downregulation of miR-128-3p similarly protects neurons following TBI. Therefore, we further decreased miR-128-3p levels using AMP to investigate whether this treatment could enhance functional recovery and improve the prognosis in an animal model.

miRNA, an important type of gene expression regulators, exhibits differential expression in various diseases [65], including TBI [53]. miRNA has simple structure, extreme stability, conservative property, and cell specificity [66–68]. These properties make miRNA an ideal target [69]. Here in this study, we show for the first time that miR-128-3p can aggravate ferroptosis through increasing MDA and ferric ion accumulation while reducing GSH levels and destroying Nissl bodies in neurons. These findings investigated that miR-128-3p may be a potential target for the treatment of post-TBI ferroptosis. Analysis of 14 human TBI samples and subsequent miRNA profiling and validation experiments in mice demonstrate a decrease in miR-128-3p levels following injury. Based on the functional study, we assume this reduction post-injury is a protective event against ferroptosis and thus the miR-128-3p could be a potential target for TBI treatment. Notably, our RNA sequencing analysis of mouse indicates that the expression of miR-128-3p did not differ significantly between the TBI and the Sham group 24 h post-injury, suggesting that miR-128-3p expression in brain injury is a dynamic process, and therapeutics targeting miR-128-3p may have a time window. The underlying causes of these changes and the differences in expression levels at different time points require more future investigation.

Our research discovered that AMP alleviates TBI by inhibiting neuronal ferroptosis through miR-128-3p/Slc7a11. SLC7A11 is a key regulator of ferroptosis, which controls cystine metabolism to affect cystine and GSH levels in cells, and indirectly enhances GPX4 activity to decrease lipid peroxide accumulation and alleviates ferroptosis [49, 70]. Our study found the direct regulation of Slc7a11 by miR-128-3p in neurons after TBI, via database prediction and validation experiments. However, there are still several other potential targets of miR-128-3p remain unstudied, for instance, Ano6 and Nfe2l2. Ano6 encodes transmembrane protein 16 F (TMEM16F), also known as Anoctamin (ANO) 6, which belongs to the anoctamin family. They are involved in various functions such as ion transport, phospholipid scrambling, and regulation of several membrane proteins [71]. Schreiber et al. reported that TMEM16F is involved in lipid regulation that is closely related to ferroptosis [72]. Another study revealed that TMEM16F may be activated by an increase in cytosolic ROS and consecutive peroxidation of plasma membrane lipids to induce ferroptosis [73]. Till now, there are few reports regarding whether TMEM16F is involved in the regulation of pathophysiological process of TBI. Nfe2l2 encodes nuclear factor E2 related factor 2(Nrf2), a key regulatory factor required for cells to maintain an oxidative steady state [74]. Increasing research have found Nrf2 signaling inhibits ferroptosis [75–77]. Accumulating studies have validated that Nrf2 signaling network participates in the regulation of ferroptosis in TBI. Li et al. found Nrf2 prevents neuronal ferroptosis in TBI by targeting hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1) [78]. Additionally, Nrf2 has been demonstrated to suppress neuronal ferroptosis by promoting antioxidant response element (ARE) expression [79]. Whether other mechanisms of Nrf2 regulate ferroptosis in TBI also needs to be further explored. Taken together, we believe these potential targets also deserve to be investigated in future studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We express our deep gratitude to these organizations for their financial support and commitment to advancing scientific inquiry.

Abbreviations

- TBI

Traumatic Brain Injury

- AMP

Aminophylline

- CCI

Controlled Cortical Impact

- miRNA

microRNA

- Slc7a11

recombinant Solute carrier family 7, member 11

- cAMP

cyclic Adenine Monophosphate

- PI3Kδ

Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase-delta

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- GSH

Glutathione

- PTEN

Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog Deleted on Chromosome 10

- Akt

V-Akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog

- FoxO3a

Forkhead box class O3a

- Ptgs2

Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase-2

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- FBS

Fetal Bovine Serum

- PMSF

Phenylmethanesulfonyl Fluoride

- TBA

Thiobarbituric Acid

- GSSH

oxidized Glutathione

- RT-PCR

Reverse Transcription PCR

- qRT-PCR

Real-Time quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- pmirGLO

pmirGLO Dual-Luciferase miRNA Target Expression Vector

- DAPI

Dye 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- MWM

Morris Water Maze

- mNSS

modified Neurological Severity Score

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- ACSL4

Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long chain family member 4

- ALOX8

Arachidonate 8-Lipoxygenase

- NOX2

NADPH Oxidase 2

- STEAP3

Six-Transmembrane Epithelial Antigen of the Prostate 3

- GPX4

Glutathione Peroxidase 4

- NFE2L2

Nuclear Factor, Erythroid derived 2, like 2

- Nrf2

Nuclear Factor E2 related factor 2

- HSPB1

Heat Shock Protein family B (small) member 1

- ANO6

Anoctamin 6

- Wnt

int/Wingless

- Hippo

Hippopotamus

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide-3-kinase

- AMPK

Adenosine 5‘-Monophosphate -activated Protein Kinase

- TMEM16F

Transmembrane protein 16 F

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- MT

Mutant Type

- WT

Wide Type

- UTR

Untranslated Region

- TEM

Transmission Electron Microscope

Author contributions

M.L., Y.X., J.L., X.Z. and Y.S. carried out the experiments. R.Y., Yuwen S. and Yihan S. performed data analysis. Q.Y. and M.Liao wrote the manuscript with support from M.Lv and X.C. W.L., X.C. and X.H. conceived the original idea and supervise the project.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China to Xiameng Chen (No. 82202077) and the Sichuan Science and Technology Program to Xiameng Chen (No. 23NSFSC4762).

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the [FerrDb] and [GEO] repository, [http://www.zhounan.org/ferrdb/current/], [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo;GSE79441].

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan University (No. K2021024).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Li Manrui, Yang Xu and Jinyuan Liu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xin Hu, Email: huxingxxy@gmail.com.

Xiameng Chen, Email: xmchen990@gmail.com.

Weibo Liang, Email: liangweibo@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Menon DK, Schwab K, Wright DW, Maas AI (2010) Position statement: definition of traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 91(11), 1637–1640. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21044706. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Maas AIR, Menon DK, Adelson PD, Andelic N, Bell MJ, Belli A, Yaffe K (2017) Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol, 16(12). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29122524. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30371-X [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jiang J-Y, Gao G-Y, Feng J-F, Mao Q, Chen L-G, Yang X-F, Huang X-J (2019) Traumatic brain injury in China. Lancet Neurol, 18(3), 286–295. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30784557. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30469-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Yang X, Chen L, Pu J, Li Y, Cai J, Chen L, Huang H (2022) Guideline of clinical neurorestorative treatment for brain trauma (2022 China version). J Neurorestoratology 10(2). 10.1016/j.jnrt.2022.100005

- 5.Rosenfeld JV, Maas AI, Bragge P, Morganti-Kossmann MC, Manley GT, Gruen RL (2012) Early management of severe traumatic brain injury. Lancet, 380(9847), 1088–1098. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22998718. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60864-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Stein SC, Georgoff P, Meghan S, Mizra K, Sonnad SS (2010) 150 years of treating severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic review of progress in mortality. J Neurotrauma, 27(7), 1343–1353. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20392140. 10.1089/neu.2009.1206 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Zafar Gondal A, Zulfiqar H (2022) Aminophylline: StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL) [PubMed]

- 8.Rudusky BM (2005) Aminophylline: exploring cardiovascular benefits versus medical malcontent. Angiology, 56(3), 295–304. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15889197 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Rabe KF, Magnussen H, Dent G (1995) Theophylline and selective PDE inhibitors as bronchodilators and smooth muscle relaxants. Eur Respir J, 8(4), 637–642. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7664866 [PubMed]

- 10.To Y, Ito K, Kizawa Y, Failla M, Ito M, Kusama T, Barnes PJ (2010) Targeting phosphoinositide-3-kinase-delta with theophylline reverses corticosteroid insensitivity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 182(7), 897–904. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20224070. 10.1164/rccm.200906-0937OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wei G, Sun R, Xu T, Kong S, Zhang S (2019) Aminophylline promotes mitochondrial biogenesis in human pulmonary bronchial epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 515(1), 31–36. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31122698. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Khan S, Arif SH, Naseem I (2019) Interaction of aminophylline with photoilluminated riboflavin leads to ROS mediated macromolecular damage and cell death in benzopyrene induced mice lung carcinoma. Chem Biol Interact, 302, 135–142. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30776357. 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Li J, Zhao P, Yang L, Li Y, Tian Y, Li S, Bai Y (2017) Integrating 3-omics data analyze rat lung tissue of COPD states and medical intervention by delineation of molecular and pathway alterations. Biosci Rep, 37(3). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28450497. 10.1042/BSR20170042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Caruso MK, Roberts AT, Bissoon L, Self KS, Guillot TS, Greenway FL (2008) An evaluation of mesotherapy solutions for inducing lipolysis and treating cellulite. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg, 61(11), 1321–1324. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17954040 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Brent RS (2022) Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell, 185(14), 2401–2421. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867422007085. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Zhiwen G, Zhiliang G, Ruibing G, Ruidong Y, Wusheng Z, Bernard Y (2021) Ferroptosis and traumatic brain injury. Brain Research Bulletin, 172, 212–219. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S036192302100126X. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2021.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Tang S, Gao P, Chen H, Zhou X, Ou Y, He Y (2020) The Role of Iron, Its Metabolism and Ferroptosis in Traumatic Brain Injury. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 14. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fncel.2020.590789. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.590789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Cheng Y, Qu W, Li J, Jia B, Song Y, Wang L, Luo C (2022) Ferristatin II, an Iron uptake inhibitor, exerts neuroprotection against traumatic brain Injury via suppressing ferroptosis. ACS Chem Neurosci 13(5):664–675. 10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenny EM, Fidan E, Yang Q, Anthonymuthu TS, New LA, Meyer EA, Bayir H (2019) Ferroptosis contributes to neuronal death and functional Outcome after traumatic brain Injury. Crit Care Med 47(3):410–418. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H, He S, Wang J, Li C, Liao Y, Zou Q, Chen R (2022) Tetrandrine ameliorates traumatic Brain Injury by regulating autophagy to reduce ferroptosis. Neurochem Res 47(6):1574–1587. 10.1007/s11064-022-03553-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma F, Zhang X, Yin K-J (2020) MicroRNAs in central nervous system diseases: A prospective role in regulating blood-brain barrier integrity. Exp Neurol, 323, 113094. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31676317. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Sabirzhanov B, Zhao Z, Stoica BA, Loane DJ, Wu J, Borroto C, Faden AI (2014) Downregulation of miR-23a and miR-27a following experimental traumatic brain injury induces neuronal cell death through activation of proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. J Neurosci, 34(30), 10055–10071. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25057207. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1260-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Han Z, Chen F, Ge X, Tan J, Lei P, Zhang J (2014) miR-21 alleviated apoptosis of cortical neurons through promoting PTEN-Akt signaling pathway in vitro after experimental traumatic brain injury. Brain Res, 1582, 12–20. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25108037. 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sun L, Zhao M, Wang Y, Liu A, Lv M, Li Y, Wu Z (2017) Neuroprotective effects of miR-27a against traumatic brain injury via suppressing FoxO3a-mediated neuronal autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 482(4), 1141–1147. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27919684. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Xiao X, Jiang Y, Liang W, Wang Y, Cao S, Yan H, Zhang L (2019) miR-212-5p attenuates ferroptotic neuronal death after traumatic brain injury by targeting Ptgs2. Molecular brain, 12(1), 78. Retrieved from 10.1186/s13041-019-0501-0. doi:10.1186/s13041-019-0501-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Cognitive Deficits Following Traumatic Brain Injury Produced by Controlled Cortical Impact (1992) Journal of Neurotrauma, 9(1), 11–20. Retrieved from https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/neu.1992.9.11 doi:10.1089/neu.1992.9.11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Long DA, Ghosh K, Moore AN, Dixon CE, Dash PK (1996) Deferoxamine improves spatial memory performance following experimental brain injury in rats. Brain Research, 717(1), 109–117. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0006899395015000. 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01500-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Bermpohl D, You Z, Korsmeyer SJ, Moskowitz MA, Whalen MJ (2006) Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice Deficient in Bid: Effects on Histopathology and Functional Outcome. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 26(5), 625–633. Retrieved from 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600258. doi:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600258 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Yuan J, Zhang J, Cao J, Wang G, Bai H (2020) Geniposide Alleviates Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats Via Anti-Inflammatory Effect and MAPK/NF-kB Inhibition. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 40(4), 511–520. Retrieved from 10.1007/s10571-019-00749-6. doi:10.1007/s10571-019-00749-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Shiotsuki H, Yoshimi K, Shimo Y, Funayama M, Takamatsu Y, Ikeda K, Hattori N (2010) A rotarod test for evaluation of motor skill learning. J Neurosci Methods 189(2):180–185. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.S., A. (2010) Analysing RNA-Seq data with the DESeq package

- 32.John B, Sander C, Marks DS (2006) Prediction of human MicroRNA targets. In: Ying S-Y (ed) MicroRNA protocols. Humana, Totowa, NJ, pp 101–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valente AJ, Maddalena LA, Robb EL, Moradi F, Stuart JA (2017) A simple ImageJ macro tool for analyzing mitochondrial network morphology in mammalian cell culture. J h 119(3):315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma W-Q, Sun X-J, Zhu Y, Liu N-F (2021) Metformin attenuates hyperlipidaemia-associated vascular calcification through anti-ferroptotic effects. Free Radic Biol Med, 165, 229–242. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33513420. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Bao Z, Liu Y, Chen B, Miao Z, Tu Y, Li C, Ji J (2021) Prokineticin-2 prevents neuronal cell deaths in a model of traumatic brain injury. Nature Communications, 12(1), 4220. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34244497. 10.1038/s41467-021-24469-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Wan T, Wang Z, Luo Y, Zhang Y, He W, Mei Y, Huang Y (2019) FA-97, a New Synthetic Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Derivative, Protects against Oxidative Stress-Mediated Neuronal Cell Apoptosis and Scopolamine-Induced Cognitive Impairment by Activating Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2019, 8239642. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31885818. 10.1155/2019/8239642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Wang Y-M, Song Z, Qu Y, Lu L-Q, J. I., Pathology E (2019) Down-regulated miR-21 promotes learning-memory recovery after brain injury. 12(3):916 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Ooigawa H, Nawashiro H, Fukui S, Otani N, Osumi A, Toyooka T, Shima KJA n (2006) The fate of Nissl-stained dark neurons following traumatic brain injury in rats: difference between neocortex and hippocampus regarding survival rate. 112:471–481 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Liu W, Chen Y, Meng J, Wu M, Bi F, Chang C, Zhang L (2018) Ablation of caspase-1 protects against TBI-induced pyroptosis in vitro and in vivo. J Neuroinflamm 15(1):48. 10.1186/s12974-018-1083-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks SP, Dunnett SB (2009) Tests to assess motor phenotype in mice: a user’s guide. Nat Rev Neurosci, 10(7), 519–529. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19513088. 10.1038/nrn2652 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Jacovides CL, Ahmed S, Suto Y, Paris AJ, Leone R, McCarry J, Pascual JL (2019) An inflammatory pulmonary insult post-traumatic brain injury worsens subsequent spatial learning and neurological outcomes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 87(3), 552–558. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31205212. 10.1097/TA.0000000000002403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Vorhees CV, Williams MT (2006) Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Protoc, 1(2), 848–858. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17406317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Seibt TM, Proneth B, Conrad M (2019) Role of GPX4 in ferroptosis and its pharmacological implication. Free Radic Biol Med, 133, 144–152. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30219704. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Tamil Selvan A, Elizabeth Megan K, Hülya B (2016) Therapies targeting lipid peroxidation in traumatic brain injury. Brain Research, 1640, 57–76. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006899316300403. 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Alok K, James PB, Dulce-Mariely A-C, Bogdan AS, Alan IF, David JL (2016) NOX2 drives M1-like microglial/macrophage activation and neurodegeneration following experimental traumatic brain injury. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 58, 291–309. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S088915911630352X. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.07.158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Chen X, Li J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D (2021) Ferroptosis: machinery and regulation. Autophagy, 17(9), 2054–2081. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32804006. 10.1080/15548627.2020.1810918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Forcina GC, Pope L, Murray M, Dong W, Abu-Remaileh M, Bertozzi CR, Dixon SJ (2022) Ferroptosis regulation by the NGLY1/NFE2L1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 119(11), e2118646119. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35271393. 10.1073/pnas.2118646119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Yang W-H, Chi J-T (2020) Hippo pathway effectors YAP/TAZ as novel determinants of ferroptosis. Mol Cell Oncol, 7(1), 1699375. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31993503. 10.1080/23723556.2019.1699375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Koppula P, Zhuang L, Gan B (2021) Cystine transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: ferroptosis, nutrient dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell, 12(8), 599–620. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33000412. 10.1007/s13238-020-00789-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Sha W, Hu F, Xi Y, Chu Y, Bu S (2021) Mechanism of Ferroptosis and Its Role in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Diabetes Res, 2021, 9999612. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34258295. 10.1155/2021/9999612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Jia B, Li J, Song Y, Luo C (2023) ACSL4-Mediated Ferroptosis and Its Potential Role in Central Nervous System Diseases and Injuries. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(12), 10021. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/24/12/10021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Gan B (2021) Mitochondrial regulation of ferroptosis. J Cell Biol, 220(9). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34328510. 10.1083/jcb.202105043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Atif H, Hicks SD (2019) A Review of MicroRNA Biomarkers in Traumatic Brain Injury. J Exp Neurosci, 13, 1179069519832286. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30886525. 10.1177/1179069519832286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Wang Y, Zheng L, Shang W, Yang Z, Li T, Liu F, Jia J (2022) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling confers ferroptosis resistance by targeting GPX4 in gastric cancer. Cell Death Differ, 29(11), 2190–2202. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35534546. 10.1038/s41418-022-01008-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Yi J, Zhu J, Wu J, Thompson CB, Jiang X (2020) Oncogenic activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling suppresses ferroptosis via SREBP-mediated lipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 117(49), 31189–31197. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33229547. 10.1073/pnas.2017152117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Magesh S, Cai D (2022) Roles of YAP/TAZ in ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol, 32(9), 729–732. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35701310. 10.1016/j.tcb.2022.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Huang Y, Wu H, Hu Y, Zhou C, Wu J, Wu Y, Sun J (2022) Puerarin Attenuates Oxidative Stress and Ferroptosis via AMPK/PGC1α/Nrf2 Pathway after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Antioxidants (Basel), 11(7). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35883750. 10.3390/antiox11071259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.O’Connell GC, Smothers CG, Winkelman C (2020) Bioinformatic analysis of brain-specific miRNAs for identification of candidate traumatic brain injury blood biomarkers. Brain Inj 34(7):965–974. 10.1080/02699052.2020.1764102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y, Guo S, Wang S, Li X, Hou D, Li H, Jiang X (2021) LncRNA OIP5-AS1 inhibits ferroptosis in prostate cancer with long-term cadmium exposure through miR-128-3p/SLC7A11 signaling. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, 220, 112376. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34051661. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112376 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Xuerong Z, Yue J, Lei L, Lina X, Zeyao T, Yan Q, Jinyong P (2019) MicroRNA-128-3p aggravates doxorubicin-induced liver injury by promoting oxidative stress via targeting Sirtuin-1. Pharmacological Research, 146, 104276. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S104366181930266X. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104276 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Teh DBL, Prasad A, Jiang W, Zhang N, Wu Y, Yang H, All A (2020) Driving Neurogenesis in Neural Stem Cells with High Sensitivity Optogenetics. NeuroMolecular Medicine, 22(1), 139–149. Retrieved from 10.1007/s12017-019-08573-3. doi:10.1007/s12017-019-08573-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Li Y, Mao L, Gao Y, Baral S, Zhou Y, Hu B (2015) MicroRNA-107 contributes to post-stroke angiogenesis by targeting Dicer-1. Sci Rep, 5, 13316. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26294080. 10.1038/srep13316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Jain KK, Jain K K. J. T. h. o. n. (2019). Neuroprotection in traumatic brain injury. 281–336

- 64.Yan Q, Sun Sy, Yuan S, Wang Xq, Zhang Z (2020) Inhibition of microRNA-9‐5p and microRNA‐128‐3p can inhibit ischemic stroke‐related cell death in vitro and in vivo. 72(11):2382–2390 c. J. I. l [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ (2017) MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 16(3), 203–222. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28209991. 10.1038/nrd.2016.246 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, Cai X, Yin Y, Wang K, Zhang C-Y (2008) Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res, 18(10). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18766170. 10.1038/cr.2008.282 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Tewari M (2008) Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 105(30), 10513–10518. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18663219. 10.1073/pnas.0804549105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]