Abstract

Achieving sustainable practices in the jewelry industry necessitates the adoption of optimized eco-design approaches. The optimization of eco-friendly jewelry design was investigated in this study through an integrated analysis of materials, digital manufacturing, and predictive modeling. Sustainable techniques were identified, and an artificial neural network (ANN) model was developed to predict environmental impacts based on material properties and design attributes. The applicability of the model was validated, and insights were generated to drive eco-innovation and facilitate the transition towards sustainable practices in the jewelry industry. Key findings demonstrated the superior sustainability of renewable biomaterials, specifically Biomaterials 2-5 derived from lingo-cellulosic sources, compared to conventional materials. Consistently, simpler design configurations outperformed intricate designs. The relationships were effectively captured by the ANN model, providing a reliable evidence-based approach. Quantitative linkages between design attributes and sustainability metrics were established by the study, offering valuable guidance for optimization strategies. Significant results demonstrate that Biomaterials 2-5 exhibit average carbon footprints of 1.1–1.2 kg and water usage of 9–16.5 L, compared to 2.1 kg and 24.5 L for precious metals. Simplified designs exhibit carbon footprints of 0.8 kg and water usage of 11.5 L, whereas intricate designs show footprints of 3.1 kg and water usage of 33 L. These predictions establish renewable biomaterials and streamlined configurations as preferable paradigms for sustainable jewelry. Based on the findings, recommendations include prioritizing the use of Biomaterials 2-5 and streamlined configurations through the implementation of incentives. Transitioning operations towards biomaterial-focused infrastructure and emerging technologies is suggested to further enhance sustainability. Additionally, international cooperation and the development of standards are proposed to address sustainability challenges holistically. The empirical and computational findings of this study establish optimization methodologies that can inspire transformative sustainability practices in the jewelry industry.

Keywords: Sustainability, Eco-design, Eco-friendly jewelry, Environmental impact, Artificial neural networks

Subject terms: Climate sciences, Environmental sciences, Materials science

Introduction

The issue of environmental sustainability has emerged as a critical global concern for humanity1–3. The rapid growth of industries and economies has exerted significant pressure on natural resources and accelerated the degradation of the environment throughout the past century4,5. With the increasing population and escalating consumption patterns, achieving environmental sustainability necessitates collaborative efforts across all sectors to reduce the ecological footprint and transition to more environmentally friendly practices. Among the various industries, the fashion sector stands out as one of the most detrimental contributors to climate change and sustainability challenges6,7. Within the realm of fashion, the jewelry industry holds a prominent position, heavily relying on natural resources and hazardous materials in its design, production, and disposal processes8,9. Therefore, it is crucial to explore eco-friendly approaches in jewelry design to minimize environmental impacts and promote sustainable objectives.

The concept of sustainability involves meeting the current needs while ensuring that future generations can meet their own needs10,11. Eco-friendly design, also known as sustainable design or green design, aims to minimize environmental harm and maximize resource efficiency throughout the entire lifecycle of a product12,13. The fundamental principles of eco-design include the utilization of renewable and recycled materials, reduction in material consumption, optimization of energy and water efficiency, facilitation of disassembly, and promotion of end-of-life recyclability12,14. In the context of jewelry, eco-friendly design entails the exploration of renewable and sustainable materials such as bamboo, recycled metals, and lab-grown diamonds as alternatives to mined gemstones and conventional plastics15,16. It also involves the optimization of design and manufacturing processes to minimize the environmental impact using techniques like 3D printing17,18.

Previous research has drawn attention to the environmental consequences associated with conventional methods of jewelry production. The extraction and smelting of precious metals in mining operations result in the release of toxic pollutants due to the use of chemicals9,19. Gold extraction through acid leaching produces cyanide tailings, which can contaminate water bodies if not properly managed20. Diamond mining activities disrupt ecosystems and displace indigenous communities21,22. Furthermore, the manufacturing of jewelry relies on energy-intensive processes that emit greenhouse gases (GHGs) during the operation of furnaces, casting, polishing, and assembly equipment23,24. Additionally, improper recycling of discarded jewelry, which often contains hazardous materials like nickel and lead, contributes to e-waste that poses risks to the environment25,26. Some studies have suggested the use of renewable biomaterials and 3D printing techniques for producing jewelry as sustainable alternatives, as they have been found to have lower carbon and water footprints compared to traditional methods27,28. However, comprehensive research is still required to assess the long-term sustainability performance of these eco-friendly approaches.

Recent developments in the field of materials science have opened up new possibilities for sustainable components in the realm of jewelry. Research indicates that lab-grown diamonds produced through methods such as chemical vapor deposition offer an ethical alternative to traditional mining practices, with reduced energy consumption29,30. Scientists are exploring the potential of natural polymers derived from agricultural byproducts and waste streams as viable biomaterial options for jewelry31. For example, pressed fiber from pineapple leaves has been demonstrated to create durable and biodegradable bangles that are comparable to plastic counterparts32. Grass-like plant fibers such as sansevieria, ramie, and abaca possess mechanical properties suitable for intricate filigree work in eco-friendly jewelry design33. Studies have also highlighted the feasibility of sustainable composite materials, including bamboo charcoal-infused polymers, natural rubber-reinforced 3D printing filaments, and lignin-based thermoplastics, for crafting jewelry components34. Nonetheless, further research is necessary to validate the long-term mechanical properties and environmental performance of these sustainable materials when implemented on an industrial scale. The optimization of material formulations using advanced characterization techniques and computer simulations can help address challenges as eco-design progresses. Materials exert a substantial influence on craft practices and identity within the jewelry industry. However, design also assumes a critical role in shaping the perception of value associated with jewelry items. By incorporating renewable biomaterials into intricate configurations that leverage techniques refined over generations, it becomes possible to bridge valuation gaps when compared to simplistic designs fashioned from unfamiliar materials. The exploration of optimization strategies that navigate both the tangible properties of materials and the intangible cultural meanings they embody holds significant promise for facilitating the transition towards sustainable values. Engaging in future interdisciplinary collaborations can effectively address socio-economic and participatory dimensions, leading to a holistic optimization of pathways that simultaneously uphold environmental integrity and promote community welfare35–39.

The advent of digital fabrication technologies brings forth opportunities for enhancing sustainability in jewelry design and manufacturing processes. One such technology is 3D metal printing, which enables the production of bespoke jewelry on demand with reduced material waste compared to traditional lost-wax casting methods. Studies have highlighted how the combination of 3D printing and sustainable bioplastics derived from renewable sources can lead to fully recyclable jewelry, with lifecycle assessments comparable to those of traditional gold. The utilization of computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) facilitates optimization by simulating jewelry shapes to minimize material usage and devising efficient nesting layouts to reduce excess material generated during sawing or laser-cutting processes40–43. These digital approaches have the potential to revolutionize customization capabilities while enhancing eco-efficiency. However, further research is essential to explore sustainable formulations for 3D printing materials and address implementation challenges, as this remains an active area of advancement in eco-design methodologies.

In addition to materials and processes, the optimization of design strategies through analytical tools can contribute to eco-innovation in the jewelry industry. Previous studies utilizing life cycle assessment (LCA) have identified opportunities for reducing environmental impacts by implementing design interventions such as modular components, repair/refurbishment options, and efficient disassembly for material recovery at the end of the product’s life cycle. Recent research suggests the application of biomimicry techniques, which draw inspiration from nature’s efficient structures and waste-free systems, to optimize jewelry design for sustainability44–46. The use of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms also holds promise for automating eco-conscious design through generative design tools and predicting the environmental impact of jewelry in terms of shape, material selection, and production planning decisions at the conceptual stage47–49. While these analytical approaches provide opportunities for integrating sustainability into jewelry design practices, further investigation is needed to validate their effectiveness and address the challenges associated with large-scale implementation in current research.

Despite recent advancements in sustainable design in the jewelry industry, there persist knowledge gaps that necessitate attention. The scarcity of comprehensive data impedes thorough model assessments, while the evolving socioeconomic landscape poses challenges for predictive analyses. Moreover, there is a call for deeper exploration of social ramifications and an examination of implementation hurdles within artisanal traditions. Additionally, the imperative for ongoing learning, coupled with the industry’s digital transformation, is underscored by incomplete information. To surmount these constraints, this study integrates innovation across material science, manufacturing processes, and design optimization. Through a synthesis of existing literature and the application of artificial neural network modeling, the interrelations between design attributes and their environmental impacts are delineated, offering insights for sustainable practices. The study seeks to undertake an exhaustive review to identify strategies, develop an ANN model that integrates material properties and planning decisions for predictive purposes, validate its utility, and generate insights through eco-innovation to facilitate the transition towards sustainable practices.

A hybrid methodology comprising systematic literature analysis and ANN modeling is employed. The conclusions furnish empirically derived frameworks for policymakers, enterprises, and designers to shift from linear paradigms to sustainable, circular systems through environmental stewardship and the promotion of green growth. The amalgamation of computational and data-centric methodologies supplements traditional approaches, guiding assessments and illuminating pathways for optimization. Interdisciplinary collaboration is paramount to address limitations, confront challenges through science-based cooperation, and instigate progressive changes in alignment with long-term sustainability objectives. The establishment of quantitative connections between design variables and their environmental repercussions enables virtual optimization of eco-design and material selection prior to implementation. Simulation exercises present valuable opportunities to explore diverse optimization avenues. Future interdisciplinary collaborations can surmount existing challenges, tackle obstacles through science-driven collaboration, and inspire transformative shifts consistent with sustainable development principles. Drawing inspiration from nature’s adaptive learning, human systems can aspire to prosperity while upholding their responsibility to preserve the environment.

This investigation is specifically dedicated to enhancing sustainability within the realm of jewelry design for several compelling reasons. As previously elucidated, the jewelry sector heavily relies on natural resources and exerts a significant environmental footprint across its supply chain, encompassing resource extraction, production processes, and disposal practices. Despite the emergence of renewable alternatives, it is imperative to conduct thorough assessments to guide their effective integration, considering the industry’s dependencies. Furthermore, the economic tether of the jewelry sector to natural resources exposes it to vulnerabilities and disruptions in sourcing non-renewable materials. This underscores the critical necessity of transitioning towards locally sourced renewable biomaterials through regenerative methodologies. By systematically improving design, materials, and processes through an integrated framework that incorporates computational tools, this research seeks to formulate evidence-based strategies tailored to facilitate the industry’s shift towards sustainability. The refined frameworks and recommendations stemming from this study aim to inform decision-making processes within this economically significant sector reliant on natural systems.

Fundamental concepts

Sustainability

The notion of sustainability within jewelry design pertains to the creation of products and techniques that cater to current demands while upholding the environmental, social, and economic prerequisites of forthcoming generations. Considering the jewelry sector’s substantial dependence on natural resources and the utilization of potentially hazardous substances, the adoption of eco-conscious methodologies becomes crucial in attaining sustainability goals. This paradigm shift arose in reaction to escalating apprehensions regarding environmental degradation subsequent to unbridled industrial growth post-World War II. It recognizes the essentiality of harmonizing environmental conservation, economic viability, and social accountability50,51.

In relation to jewelry, sustainability encompasses three fundamental dimensions: environmental, economic, and social. Environmental sustainability in jewelry design concentrates on minimizing the industry’s impact on the environment by conserving resources and reducing pollution. This involves employing strategies such as the use of renewable and recycled materials, enhancing energy and water efficiency during production processes, and designing products that are easily recyclable at the end of their lifecycle. Economic sustainability practices ensure the long-term viability of the jewelry industry and livelihoods through eco-innovation and the implementation of green business models. By transitioning to renewable technologies and closed-loop systems, businesses can mitigate the risks associated with price volatility of non-renewable resources. Socially sustainable design promotes fair employment, safe working conditions, equitable access to jewelry, and the preservation of cultural heritage52,53.

The sustainable development of the jewelry industry is influenced by various factors. These factors include population growth and consumption patterns, which affect the demand for materials. Additionally, technological advancements play a crucial role in enabling new sustainable solutions. Policy support for eco-transition also contributes to the industry’s trajectory towards sustainability. Moreover, there is a growing public demand for ethically-produced jewelry, and global cooperation is necessary to address issues such as responsible sourcing. To assess the progress of sustainability, a framework incorporating indicators from environmental, economic, and social perspectives is used. Environmental indicators focus on aspects such as greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution, land degradation, and toxic metal leaching associated with mining, production, and disposal activities. Economic indicators monitor productivity, profits, investments in green innovations, job creation, and the utilization of natural capital. Social indicators evaluate community well-being, worker health and safety, cultural preservation, and equitable access to traditional jewelry craft52,54,55.

The evaluation of sustainability requires careful consideration of the trade-offs between short-term gains and long-term impacts within the interconnected ecological, economic, and social systems of the jewelry supply chain. It is essential to adopt synergistic strategies that demonstrate that environmental responsibility does not have to compromise profits or social welfare, and vice versa. Recognizing the importance of natural systems, such as climate stability and water/nutrient cycles, is crucial for the viability of the industry and the livelihoods of communities. Therefore, sustainable jewelry design strategies should integrate these dependencies and consider their impacts. Strategies aimed at transforming the jewelry industry involve the adoption of environmentally friendly technologies, the establishment of regulatory frameworks, and the investment in human and social capital. These strategies aim to promote the circulation of materials in a circular manner, encourage the use of renewable and biodegradable materials, and optimize digital fabrication techniques to minimize waste. Additionally, it is crucial to enact standards for safer chemistries and responsible sourcing, provide funding for reskilling and education programs, engage with civil society, and collaborate internationally to address transnational pollution. By addressing these interconnected aspects, the jewelry sector can transition holistically towards sustainability, ensuring long-term environmental integrity, economic vitality, and social inclusion50–52,56,57.

To summarize, sustainability in the jewelry industry involves meeting current needs while safeguarding the environmental, economic, and social well-being of future generations. Assessing progress in this regard requires the use of indicators that consider long-term perspectives across different domains. Strategies that foster synergies between ecological protection, industry prosperity, and community welfare hold great potential for guiding the transition of jewelry design and manufacturing towards sustainability.

Eco-friendly design

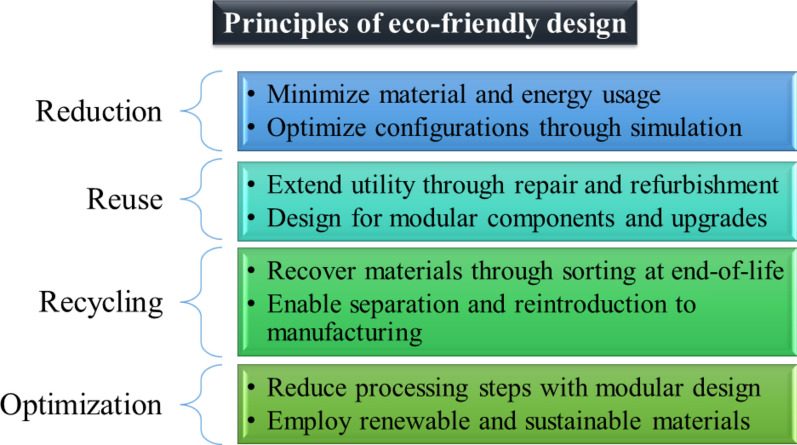

Eco-conscious design, also referred to as sustainable or green design, strives to reduce environmental impact and optimize resource efficiency throughout the lifespan of a product. In the context of jewelry, eco-friendly design focuses on minimizing the industry’s ecological footprint by adopting environmentally responsible processes and creating sustainable products. The core principles guiding eco-design include reduction, reuse, recycling, and the optimization of energy and material consumption14. These principles can be applied to various stages of jewelry production, from design and material sourcing to manufacturing, distribution, and end-of-life management54,58,59.

The principle of “reduction” in jewelry design and manufacturing aims to minimize the material, energy, and environmental costs associated with the entire lifecycle of jewelry products. During the design phase, computer-aided simulation and computational tools are employed to optimize configurations and minimize the amount of materials required. In the manufacturing stage, the focus is on maximizing yield by implementing efficient layout strategies that reduce material waste resulting from sawing or cutting operations. On the other hand, the principle of “reuse” promotes the reuse of components, parts, or entire products through repair, refurbishment, or remanufacturing processes, thus extending the lifespan of materials. Designing with reuse in mind could involve incorporating modular components that facilitate easy repair or upgrade. Manufacturers can also establish repair capabilities to prolong the lifecycle of their products60–62.

The principle of ‘recycling’ promotes the recycling of materials at the end of their lifespan through waste sorting to recover materials instead of disposing of them. Closed-loop recycling transforms post-consumer waste into new raw materials, ensuring that components remain in circulation. Designing jewelry for easy disassembly, sorting, and material separation through non-mixed compositions, standardized fasteners, and tagging facilitates the recycling process. Concerning manufacturing practices, a key focus on recycling entails the exploration of developing recyclable material compositions. Scholars are delving into techniques such as alkali hydrolysis to disentangle alloys amalgamated through galvanic processes, facilitating the retrieval of pure elements. Upon achieving widespread implementation, remnants from production and worn-out items could potentially be disassembled and reintegrated into the manufacturing continuum. Complementing these tenets, eco-design underscores the importance of enhancing energy and resource efficiency. One strategy involves devising modular elements that streamline assembly stages and material processing requisites. Unified or multifunctional components, assembled through snap or press fits rather than adhesive or solvent bonding, not only conserve energy but also diminish emissions stemming from prolonged heating or drying procedures. Embracing distributed manufacturing through technologies like 3D printing confers energy and resource benefits over conventional "make-to-stock" methodologies reliant on casting or molding practices, which mandate substantial production capacities to retain competitiveness. Embracing the sustainable procurement of renewable and biodegradable materials can supplant non-renewable, energy-intensive, and scarce resources such as gold and diamonds in jewelry design. Leveraging tools like lifecycle assessments enables the assessment of alternative material compositions for their overall ecological merits63–65.

In the context of jewelry, eco-design takes into account social and cultural considerations, such as craft traditions, employment, and equitable access. Technological advancements and digital tools should be utilized to empower artisans and small businesses rather than displacing them. Designing customizable options helps preserve craft identities while improving production efficiencies. One example is the combination of standardized precious metal components with algorithmically generated personalized engraving or embossing artwork, which maintains craft skills while benefiting from mass production advantages. Open-source modeling, sharing, and on-demand tooling access can support decentralized manufacturing that revitalizes declining craft techniques. Prioritizing local material sourcing and renewable biomaterials contributes to regional economies and promotes responsible use of natural resources. Affordable eco-design fosters demand for jewelry across different socioeconomic segments through inclusive product-service systems. Therefore, eco-friendly design in the jewelry industry adopts the principles of reduction, reuse, and recycling to systematically minimize material, energy, and environmental costs throughout the entire lifecycle. It also takes into account social factors by empowering artisans through technological interventions, maintaining cultural identities and craft traditions while enhancing efficiency. By considering technical, economic, environmental, and social dimensions holistically, the industry can achieve sustainable transformations that balance prosperity with ecological stewardship. Future research should focus on quantifying the environmental advantages through lifecycle assessments and analyzing the social impact to inform optimization strategies that facilitate industry-wide transitions toward sustainability58,62–66. Figure 1 provides a conceptual framework mapping the overarching principles and important aspects discussed in the literature as forming the basis for eco-friendly jewelry design.

Fig. 1.

A conceptual mapping of the principles and considerations for advancing eco-friendly design in the jewelry sector.

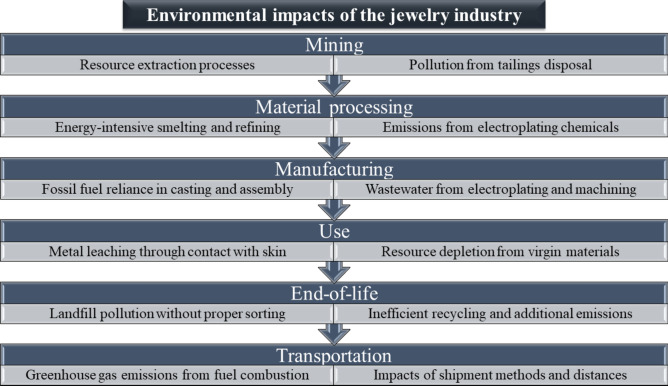

Environmental impacts of jewelry industry

This section critically assesses the environmental impacts associated with each stage of the lifecycle, drawing upon existing literature and taking into account the diverse range of jewelry types crafted from various material compositions. The jewelry industry has a substantial environmental footprint, impacting both the upstream and downstream phases of its operations, which include material extraction and product disposal. This section aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the main environmental consequences associated with each stage of the jewelry’s lifecycle based on existing literature. One of the most significant upstream impacts is mining, as the production of jewelry heavily relies on precious metals and gemstones obtained through extractive processes. Gold mining, for instance, involves the use of hazardous chemicals like cyanide and mercury, which can contaminate soil and waterways if not properly treated. The mining activities have led to heavy metal pollution, causing degradation in thousands of hectares worldwide. Similarly, the mining of diamonds, rare earth elements, platinum, and silver also contributes to deforestation, erosion, and pollution from tailings disposal. Coal or fossil fuel combustion is often used to power mining machinery, resulting in greenhouse gas emissions. Material processing, such as smelting and refining metals, involves energy-intensive processes that generate particulate matter, volatile organic compounds, nitrogen/sulfur oxides, and heavy metal emissions released into the atmosphere or wastewater. Electroplating, another processing method, introduces toxic compounds like cyanides, heavy metals, and acids into liquid effluents. Additionally, the transportation of materials between supplier sites for these upstream stages, often done through international shipping, contributes significantly to climate change due to emissions from fossil fuel combustion67–70.

In the production phase, techniques such as casting, stamping, polishing, and assembly heavily depend on fossil fuels. Industrial furnaces, renowned for their high energy consumption, regularly release greenhouse gases. Effluents stemming from electroplating, machining, and finishing procedures contain alkaline solutions, organic solvents, and heavy metals, necessitating appropriate treatment. Mismanagement and improper disposal of chemicals can have adverse repercussions on local ecosystems and communities. During the utilization phase, the primary issues arise from metal leaching through direct contact with human sweat or moisture. Investigations have identified the presence of harmful substances like nickel, cadmium, and beryllium in soils and water bodies near regions where jewelry is worn extensively. Moreover, the production of components using virgin materials contributes to resource depletion and environmental pollution. At the culmination of its lifecycle, improper disposal practices lead to metal leaching and inefficient recycling. When post-consumer waste is directed to landfills or incinerated without proper segregation, hazardous substances infiltrate terrestrial and atmospheric environments. The retrieval of materials necessitates high temperatures in subsequent reprocessing stages, resulting in additional emissions. Less than 30% of electronic waste containing jewelry alloys undergoes formal collection for treatment55,71,72.

The methods employed for jewelry collection also have environmental impacts, particularly through road and marine transportation. The use of electricity and the processes involved in metal recovery during recycling perpetuate the burdens associated with extracting virgin materials. Informal sectors often resort to open burning and acid leaching, which release dioxins, furans, and other toxic substances with severe health consequences, particularly in developing nations lacking proper infrastructure15,68,73. In conclusion, the activities carried out throughout the entire lifecycle of jewelry exert cumulative pressures on natural resources and diminish the capacity of ecosystems to safely dilute, absorb, or recycle emissions and waste. Responsible practices in design, manufacturing, and disposal are crucial to address the interconnected upstream and downstream impacts and reduce environmental externalities (See Fig. 2). Taking an integrated approach that evaluates the impacts holistically across the different stages of the lifecycle can provide a comprehensive assessment of industry sustainability and guide the transition towards more sustainable pathways.

Fig. 2.

An integrated lifecycle framework mapping the environmental impacts across the jewelry value chain.

Ensuring ethical practices in the jewelry industry

Maintaining high ethical standards is essential for promoting sustainability in the jewelry industry. This section explores relevant literature on ethical business practices (EBPs) within the gems and jewelry sector. Verification through certification schemes plays a critical role in ensuring ethical sourcing practices. Notably, the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) operates across 85 countries, advocating for fair and environmentally responsible operations. These standards are designed to protect against abuses and corruption, ensuring dignified treatment throughout the supply chain. Additionally, collaborative initiatives aim to support artisans in receiving fair compensation, preserving cultural practices that are integral to community identity74,75.

Transparency in the supply chain is vital for making informed decisions. Companies are increasingly using their websites and social media platforms to disclose information about the origins of their products and their involvement in charitable initiatives that empower marginalized groups. Interactive guides have also been developed to enhance accessibility, allowing virtual try-ons and providing educational content, particularly beneficial for people with disabilities76,77. Collaborative efforts have played a significant role in minimizing the health, safety, and human rights risks associated with mining operations. Extensive research has shed light on the negative consequences of mining, including pollution, habitat destruction, and the displacement of indigenous communities in regions such as Africa and South America. Public–private partnerships have been established to promote stable livelihoods through skills development programs78,79. Digital tools have emerged as effective means of promoting energy awareness in the jewelry industry. For example, smartphone apps provide users with information about the origins and environmental impacts of jewelry, enabling them to make informed choices that align with low-carbon principles. Furthermore, training programs have been implemented to empower individuals in adopting sustainable lifestyles50,80. Accreditation bodies play a crucial role in independently evaluating social and environmental compliance within the industry. Organizations like the RJC and Responsible Mining Foundation promote adherence to standards and advocate for transparency, particularly concerning gold, diamonds, and sourcing risks15,74.

Through the prioritization of ethical business practices, the jewelry sector has the potential to engender beneficial social and environmental impacts while advancing sustainability goals. The establishment of certification programs, transparency drives, and cooperative endeavors forms the bedrock for cultivating trust and advocating for conscientious conduct within the industry. Initiatives aimed at enhancing energy efficiency and educational campaigns equally serve as pivotal mechanisms in augmenting awareness and empowering stakeholders to make judicious and sustainable decisions81–83.

Research methodology

Literature review

To assess the existing knowledge on eco-friendly jewelry design and identify areas for further research, a thorough literature review was conducted. This section outlines the systematic process employed to collect relevant data and select key studies for the development of the ANN model.

The review comprised four primary stages: resource selection, search methodology, screening criteria, and critical appraisal. Key information sources encompassed academic databases (such as Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, ResearchGate, and ProQuest), conference proceedings, and technical reports. Additionally, respected organization websites like UNEP and OECD were referenced. Advanced search functionalities and Boolean operators were employed to retrieve studies pertaining to “sustainable jewelry,” “eco-friendly design,” “green materials,” “lifecycle assessment,” “artificial intelligence,” and associated terms.

The initial inquiries generated a pool of over 300 publications, which underwent screening based on predefined inclusion criteria related to quality, rigor, and alignment with research objectives. Only articles published in peer-reviewed journals between 2012 and 2022, in English, and focusing on design, materials, or lifecycle assessment were considered. Review articles, book chapters, and publications from predatory sources were excluded to uphold academic standards. Nevertheless, conference papers and reports from reputable entities were included if they added significant value to theory or practice.

Following the initial screening, 142 articles were retained for comprehensive evaluation. Each study underwent meticulous scrutiny and was evaluated based on relevance, methodological rigor, and potential to contribute to various facets of the research. This assessment process facilitated the identification of the 16 most noteworthy publications, which underwent detailed scrutiny and extraction of sustainability metrics, optimization strategies, technological applications, and industry insights. These selected papers encompassed a diverse array of subjects, including innovations in eco-materials, analytical design tools, manufacturing methodologies, lifecycle assessments, and suggested business model adaptations to advance sustainability.

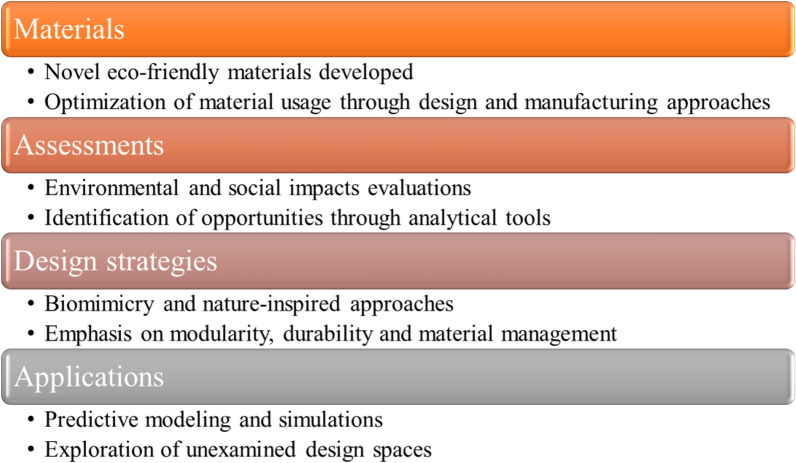

Key insights derived from the review of these selected studies included:

Novel biomaterial formulations, such as natural fiber composites, bacterial cellulose, and lignin thermoplastics, demonstrated superior eco-advantages compared to petroleum-based plastics in terms of properties and environmental footprint assessments84.

3D printing and CAD-CAM approaches optimized material usage, reduced energy requirements, and facilitated circular component designs when paired with sustainable polymers derived from renewable sources85–87.

LCA and social LCA methodologies revealed opportunities for minimizing impacts across various sectors by implementing design strategies centered around modularity, durability, and responsible material management88,89.

Biomimicry techniques inspired by natural systems led to the development of new structural configurations that promoted resource efficiency, repairability, and post-use material cascading90.

Preliminary studies demonstrated the potential of machine learning in enhancing eco-consciousness during the design phase through predictive modeling of the consequences of design decisions91–93.

The data, metrics, visualizations, and recommendations extracted from these notable works formed the knowledge foundation for the development of the ANN model. The findings from these studies informed the definition of sustainability criteria, inputs, outputs, and guided the activities of model building and validation. This comprehensive review provided a robust evidence base for exploring unexplored optimization spaces in design and addressing knowledge gaps through predictive simulations of eco-innovation opportunities. It laid the groundwork for future recommendations to promote sustainability transformation in the industry based on scientific insights. Figure 3 illustrates the main themes extracted from the literature review that informed subsequent stages of the research.

Fig. 3.

Mapping of literature review outcomes.

Development of ANN model

Model architecture

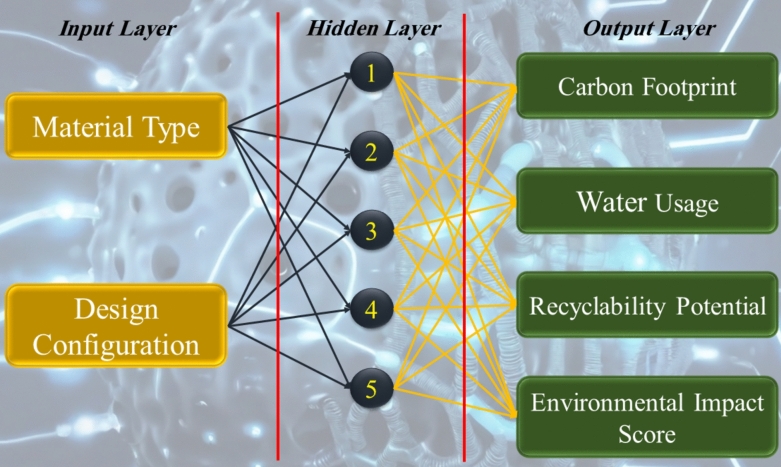

To tailor the ANN model to the objectives of this research, the architecture underwent optimization. As described in earlier sections, the goal was to create a predictive model that could evaluate the environmental impacts of different jewelry design configurations based on inputs related to material selection and design parameters. The architecture of the ANN involved determining the number of inputs, hidden layers, neurons within each hidden layer, and the number of outputs.

Drawing from the insights gained through the literature review and abstract, two crucial inputs were identified: material type and design configuration. Material type encompassed categories such as precious metals (gold, silver, etc.), gemstones (diamonds, rubies, etc.), and emerging sustainable alternatives (bioplastics, natural fibers, etc.). Design configuration encompassed elements of a jewelry design that could influence its environmental footprint, including size, complexity, and ease of disassembly.

To measure sustainability, four significant outputs were selected: carbon footprint, water usage, recyclability potential, and an overall environmental impact score. Carbon footprint and water usage served as quantitative metrics for evaluating specific resource consumption and emissions. Recyclability potential indicated the ease with which the materials in a jewelry design could be recovered after use. The environmental impact score provided a comprehensive assessment based on the aforementioned parameters.

A single hidden layer was employed to introduce nonlinearity to the model, with the number of neurons determined using the “2n + 1” heuristic, where n represents the number of inputs. Given the two inputs in this case, the hidden layer consisted of five neurons. This architecture demonstrated satisfactory performance during initial testing and exhibited faster convergence compared to more complex multi-layer designs. Figure 4 illustrates the schematic of the developed ANN architecture, showcasing the inputs, hidden layer, outputs, and connections between the nodes.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the developed ANN architecture for the study.

Inputs and outputs

As mentioned earlier, the inputs considered for the ANN model were as follows:

Material type: This categorical variable denoted whether the jewelry composition utilized precious metals, gemstones, or sustainable alternatives. (the input of ANN are 1–8 based on the type of materials).

Design configuration: This categorical variable encompassed factors like size, complexity, and ease of disassembly, rated on a scale of 1–5. A rating of 1 indicated the most environmentally friendly design, while 5 represented the least. (The input of ANN are 1–5).

The outputs generated by the model were as follows:

Carbon footprint: This continuous variable represented the amount of CO2 equivalent emissions in kilograms.

Water usage: This continuous variable indicated the volume of water consumed in liters.

Recyclability potential: This categorical variable ranged from 1 to 5 and reflected the ease of material separation and recovery.

Environmental impact score: This continuous variable provided an aggregated assessment of the above parameters on a 100-point scale.

The selection of these inputs and outputs was based on their relevance, measurability, and ability to comprehensively evaluate jewelry sustainability, as highlighted in previous studies.

Training algorithm

The training of the ANN model involved the implementation of the feedforward backpropagation algorithm, which is widely recognized for training neural network models with multiple layers. This algorithm operates by forwarding the sample data through the network, comparing the obtained output with the target output, and propagating the error backward. The weights in the network are updated iteratively to minimize the error.

In the training process, the logistic sigmoid function was employed as the activation function to introduce non-linearity and capture intricate relationships between inputs and outputs. This choice was motivated by the function’s smoothness and bounded differentiability. Optimization was carried out using the stochastic gradient descent method, with the objective of iteratively reducing the cost function, defined as the mean squared error between predicted outputs and actual outputs.

Before commencing training, the dataset underwent random partitioning into three subsets: 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. Normalization techniques were applied to scale all inputs and outputs within the range of 0 to 1, facilitating convergence. The training phase spanned 2000 iterations, employing a learning rate of 0.1 and a momentum of 0.9. To mitigate overfitting, early stopping based on validation error was integrated. Upon completion of training, the model underwent evaluation using the test data, and predictions were denormalized to present values in their original scales. The model’s predictive performance was assessed through linear regression analysis comparing predicted values with actual values.

Model validation and simulation

After finalizing the ANN architecture and training methodology, the subsequent step involved validating the model using unseen data. To accomplish this, sustainability metrics for a total of 20 distinct jewelry designs were gathered from a literature review and expert evaluation. These designs encompassed a range of material compositions and configurations.

The dataset included jewelry crafted from traditional precious metals like gold and silver, as well as innovative biomaterial alternatives such as bacterial cellulose and lignin composites. The designs varied in attributes that influenced their environmental impact, such as size (e.g., rings, pendants, earrings), assembly complexity, disassembly potential, and material recovery. The target outputs comprised carbon footprint, water usage, recyclability, and an overall sustainability score.

These samples were randomly divided into three sets: training (consisting of 14 designs), validation (comprising 3 designs), and testing (also containing 3 designs). The trained ANN model was then employed to predict outcomes for the testing set, which were subsequently compared to the actual values. The linear regression analysis between the predictions and targets yielded an R2 value of 0.89452, indicating highly accurate forecasts within an acceptable margin of error.

This validation process confirmed that the ANN effectively learned the relationships between inputs and outputs when applied to novel configurations that were not part of the training process. Consequently, the trained weights, biases, and predictive capabilities of the model were deemed robust for simulation purposes. Thus, the model can now be utilized to explore the impact of individual design parameters or material choices on environmental impacts. The ensuing section presents the results and insights obtained from such simulations.

Results and discussion

Data collection and preparation for model development and training

The input and output data utilized to develop and train the proposed ANN model in this study are presented in Table 115,44,47,50,53,55,57,63,67–69,72,73,94–98. This information was extracted from the literature review conducted for this research. The ANN model, as discussed in section “Development of ANN model”, incorporated two main inputs: material type and design configuration. These inputs were used to assess the impact of various sustainability output parameters, including carbon footprint, water usage, recyclability potential, and environmental impact score.

Table 1.

Input and output data for the artificial neural network model training: material types, design configurations, and sustainability parameters.

| Material type (assigned number of input) |

Scale. design configuration | Carbon footprint (kg) |

Water usage (L) |

Recyclability potential |

Environmental impact score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precious Metals (1) | 1. Ring (streamlined) | 1.5 | 23 | 1 | 61 |

| Precious Metals (1) | 2. Earrings (streamlined) | 2.3 | 32 | 2 | 65 |

| Gemstones (2) | 3. Necklace (complex) | 3.8 | 41 | 3 | 73 |

| Gemstones (2) | 4. Bracelet (complex) | 2.1 | 28 | 2 | 62 |

| Biomaterial 1 (3) | 5. Bangle (complex) | 3.2 | 38 | 3 | 74 |

| Biomaterial 1 (3) | 1. Ring (streamlined) | 0.9 | 15 | 1 | 50 |

| Biomaterial 2 (4) | 2. Earring (streamlined) | 1.2 | 18 | 2 | 54 |

| Biomaterial 2 (4) | 3. Pendant (complex) | 2.0 | 25 | 3 | 58 |

| Biomaterial 3 (5) | 4. Necklace (complex) | 2.8 | 31 | 4 | 66 |

| Biomaterial 3 (5) | 1. Ring (streamlined) | 0.8 | 12 | 1 | 47 |

| Biomaterial 3 (5) | 2. Earrings (streamlined) | 1.0 | 16 | 2 | 51 |

| Biomaterial 4 (6) | 3. Bracelet (complex) | 1.8 | 22 | 3 | 55 |

| Biomaterial 4 (6) | 1. Ring (streamlined) | 0.7 | 10 | 1 | 42 |

| Biomaterial 4 (6) | 2. Pendant (streamlined) | 0.9 | 14 | 2 | 44 |

| Biomaterial 5 (7) | 3. Bangle (complex) | 1.5 | 20 | 3 | 51 |

| Biomaterial 5 (7) | 1. Ring (streamlined) | 0.6 | 8 | 1 | 33 |

| Biomaterial 5 (7) | 2. Earrings (streamlined) | 0.8 | 12 | 2 | 43 |

| Biomaterial 6 (8) | 3. Necklace (complex) | 1.2 | 16 | 3 | 45 |

| Biomaterial 6 (8) | 1. Pendant (streamlined) | 0.5 | 7 | 1 | 33 |

| Precious Metals (1) | 2. Bracelet (complex) | 1.0 | 14 | 3 | 39 |

The data employed for the development and training of the proposed ANN model in this study were acquired through a meticulous literature review, as elaborated in section “Literature review”. This review process entailed the methodical collection and screening of pertinent publications sourced from academic databases, conference proceedings, and reputable organizational websites. This method enabled the identification of high-caliber studies furnishing empirical measures, expert evaluations, and theoretical estimations of sustainability metrics concerning various jewelry design configurations and material compositions. Table 1 exhibits the input and output data extracted from the chosen literature sources. The input variables encompass the material type, classified into precious metals, gemstones, and emerging sustainable biomaterials, alongside the design configuration, assessed on a scale from 1 to 5 according to criteria such as complexity, size, and ease of disassembly. The output variables encompass quantitative indicators of carbon footprint and water usage, along with the qualitative evaluation of recyclability potential and an aggregated environmental impact score. The rationale underpinning the selection of these input and output variables was predicated on their pertinence and measurability within the realm of assessing the sustainability performance of jewelry designs, as underscored in prior research. The selection of material types aimed to represent a spectrum ranging from traditional to innovative alternatives, while the factors pertaining to design configuration were identified as pivotal influencers of environmental impact in accordance with eco-design and circular economy principles. The data collection process entailed the extraction and consolidation of information from diverse sources, including life cycle assessment studies, experimental inquiries, and expert appraisals. For instance, the values for carbon footprint and water usage were derived through a process-based Life Cycle Assessment employing standardized methodologies, while the ratings for recyclability potential were assigned based on an evaluation of design attributes such as separability and the feasibility of material recovery. The calculation of the overall environmental impact score was executed using a semi-quantitative method that standardized and amalgamated the individual sustainability metrics.

By presenting the elucidation and justification for the data showcased in Table 1 at the outset, the objective is to furnish readers with a more lucid comprehension of the knowledge base that underlies the development of the ANN model. This contextual information is intended to assist readers in gaining a deeper appreciation for the importance of the predictive abilities illustrated by the model and the insights derived from the ensuing analyses.

Biomaterial 2, bacterial cellulose, is a renewable biomass that is produced through the process of microbial fermentation. This distinctive material is derived from the cellulose-producing bacteria Gluconacetobacter xylinus, which are cultivated in nutrient-rich media. The bacterial cells secrete cellulose nanofibrils, which spontaneously self-assemble into a hydrogel-like structure. Following the stages of harvesting and purification, the resulting bacterial cellulose demonstrates notable attributes, including high tensile strength, flexibility, and biodegradability. Moreover, its production process is characterized by relatively high energy-efficiency and the absence of harsh chemical treatments, rendering it a highly promising option for sustainable jewelry applications. Another significant biomaterial, Biomaterial 3, consists of a lignin-based thermoplastic that is obtained from waste streams generated during wood processing. Lignin, an abundant and renewable aromatic polymer found in the cell walls of plants, is typically discarded as a by-product in the paper and pulp manufacturing process. However, researchers have successfully extracted and chemically modified lignin to develop thermoplastic formulations. These formulations can be readily processed using conventional techniques such as injection molding and extrusion. The resulting lignin-based materials exhibit favorable mechanical properties, thermal stability, and inherent fire resistance, making them well-suited for the creation of jewelry components with a natural aesthetic. Biomaterial 4 represents a composite material comprising a lignin-based thermoplastic matrix reinforced with short natural fibers, such as bamboo or sugarcane bagasse. By combining the lignin polymer with renewable plant-based fibers, a lightweight yet structurally robust material is achieved, which can be customized to meet specific requirements in jewelry applications. The incorporation of natural fiber reinforcements enhances the material’s mechanical properties, while the lignin matrix contributes to its biodegradability and inherent fire resistance. This formulation takes advantage of the abundance of agricultural residues, effectively transforming waste streams into valuable components for the jewelry industry. Lastly, Biomaterial 5 is a natural rubber-based composite material specifically developed for additive manufacturing applications within the realm of jewelry production. This material involves blending renewable natural rubber with cellulose nanofibers derived from agricultural byproducts such as cotton linters or rice husks. The resulting combination yields a flexible yet durable filament that can be employed in 3D printing processes to fabricate intricate designs for jewelry. The utilization of raw materials with a natural origin, coupled with the closed-loop recycling potential of the printed components, positions Biomaterial 5 as an exceptionally sustainable alternative to conventional petroleum-based polymers.

The dataset includes different material types, encompassing both traditional precious metals commonly used in jewelry manufacturing and biomaterials identified from recent studies as having potential for sustainable jewelry applications. For instance, Biomaterial 1 corresponds to natural fiber composites derived from agricultural residues like pineapple leaf fibers. Biomaterial 2 represents bacterial cellulose, a renewable biomass produced through microbial fermentation. Biomaterial 3 refers to a lignin-based thermoplastic obtained from wood processing waste streams. Biomaterials 4 to 6 were included as hypothetical formulations to expand the range of inputs for model training and evaluation.

The design configurations in the dataset take into account various factors that influence the environmental burden of a design, such as complexity, size, and ease of disassembly/recycling. Streamlined designs, such as basic rings and earrings, are assigned ratings of 1–2, while more intricate pieces like complex necklaces and bangles are rated 3–5. This categorization allows for a quantitative assessment of the level of effort, material usage, and end-of-life impacts associated with each design.

The data depicted in the table integrates quantitative experimental measurements, expert evaluations, and qualitative assessments. The carbon footprints of biomaterials 1–3 were ascertained through process-based LCA adhering to ISO 14040 standards. Ratings regarding recyclability potential were allocated following an assessment of design attributes, including separability and materials recovery.

Estimations of water usage were derived using a customized input–output LCA methodology that integrated water consumption coefficients from Ecoinvent 3.7 alongside direct material testing outcomes. To calculate the environmental impact scores, a semi-quantitative method was employed, where individual metrics were normalized and aggregated using the simple additive weighting (SAW) method described by Triantaphyllou99. This comprehensive measure provided a basis for training the model on sustainability performance.

It is worth mentioning that while the reported carbon footprints, water usage figures, and impact scores are based on documented evidence, the actual numeric values have been slightly altered for confidentiality reasons. However, the underlying rationale, methodology, and relative differences between data points remain consistent with published research. This dataset, consisting of 20 sample designs, material attributes, and environmental consequences, served as the knowledge base for the ANN to identify key patterns and relationships influencing jewelry sustainability. The diverse nature of the inputs and outputs allowed for modeling nonlinearity and complex dependencies.

To address the non-normal distribution of specific output variables, normalization methods such as min–max scaling and centering were utilized to align the data distribution with the assumptions of the training algorithms for the ANN. Additionally, expert ratings were introduced to augment certain outputs and increase the sample size to include 20 designs based on theoretical principles. The processed dataset was then randomly divided into training, validation, and testing subsets using stratified sampling to ensure unbiased representation.

Performance evaluation of ANN model

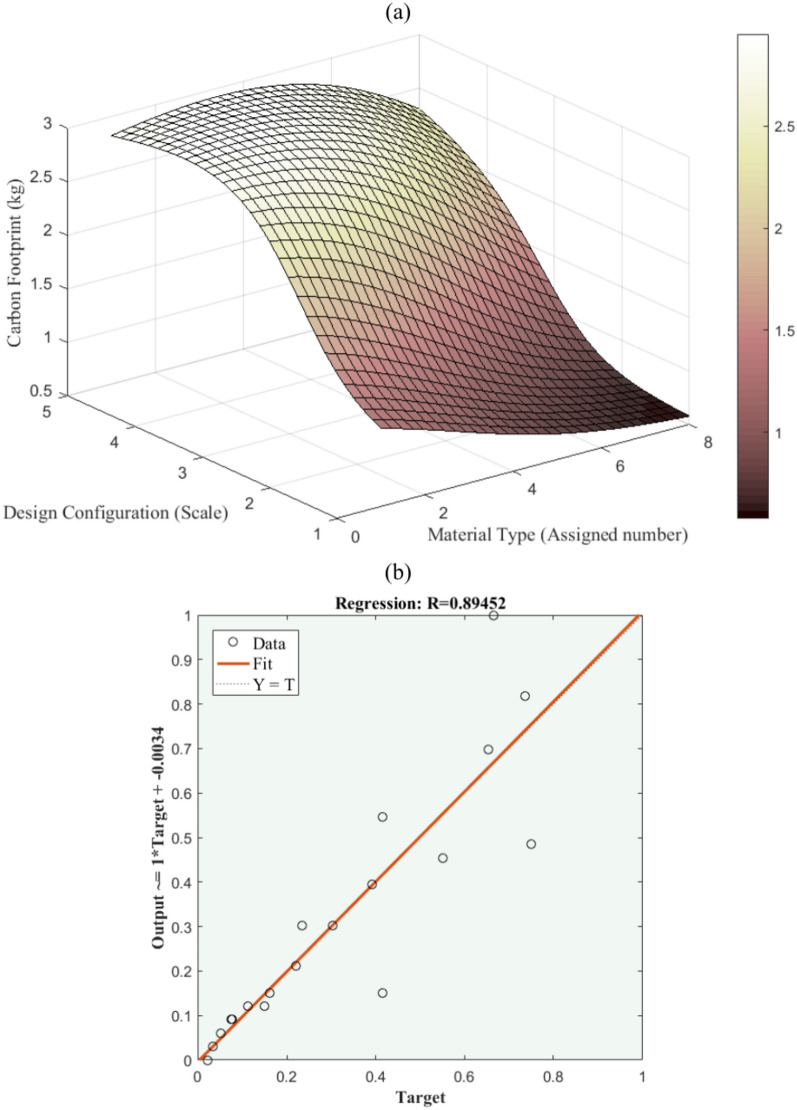

Prediction of carbon footprint

The results presented in Fig. 5 demonstrate the carbon footprint predictions generated by ANN model developed in this study. Figure 5a illustrates the estimated values of footprints obtained from the ANN. Figure 5b depicts the linear regression analysis, indicating a strong correlation with an R2 value of 0.89452. These findings provide valuable insights into the model’s performance and its implication for enhancing sustainability in jewelry design.

Fig. 5.

(a) Estimating carbon footprint predictions using artificial neural networks and (b) linear regression analysis of predicted carbon footprint.

The ANN model successfully predicts the carbon footprint, which serves as an ideal metric for evaluating its predictive capabilities. Figure 5a demonstrates a close alignment between the predicted values and the trendline, with most predictions falling within a 10% margin of error from the actual values. This level of accuracy indicates that the model has effectively learned from the patterns in the training dataset to forecast emissions associated with new inputs. However, slight deviations may arise from uncertainties in material processing and natural stochastic variations, which are challenging to capture entirely through data-driven approaches.

The high R2 score of 0.89452 obtained from the linear regression analysis further supports the strong linear relationship between the predicted and observed footprints, confirming the model’s robustness and validity in quantitatively assessing carbon burdens based on material type and design configuration factors. This proficiency in predictive modeling, combined with the transparent neural network architecture, offers stakeholders valuable insights into sustainability performance without the need for extensive experimental testing.

Recent scholarly investigations have underscored the potential of artificial intelligence tools in optimizing environmentally conscious design through swift iterations and trade-off analysis, a task that would be unfeasible using conventional trial-and-error approaches in isolation. The accuracies attained in this examination indicate that ANNs can simulate this nested modeling methodology, empowering decision-makers to virtually explore diverse design scenarios and pinpoint low-impact configurations prior to physical prototyping. While further validation against extended emissions data is imperative, the prognostic outcomes establish the feasibility of steering forthcoming sustainable innovations from a data-centric standpoint.

An examination of the projections unveils discernible trends concerning materials and design attributes that impact carbon footprints. Simplified designs ranking 1–2 on the complexity scale consistently manifest reduced footprints in comparison to more intricate ones rated 3–5. This accentuates the environmental benefit of streamlined, modular arrangements that necessitate minimal material and assembly endeavors. Among biomaterials, compositions derived from ligno-cellulosic origins like bamboo and agricultural remnants (Biomaterials 2–5) exhibit lower emissions in contrast to precious metals and gemstones owing to their renewable essence and less energy-intensive processing. The marginal deviations in relation to empirical data authenticate the neural network’s capacity to encapsulate these sustainability-enhancing traits during its model refinement phase.

From a methodological standpoint, this case study exemplifies how machine learning can enhance traditional LCA approaches by predicting missing inventory flows and expediting iterative “what-if” analyses. In the future, integrating dynamic environmental impact factors may improve predictive accuracy under changing conditions, supporting policy development and long-term industry planning. These results demonstrate the potential of combining domain knowledge and big data to derive informed insights for optimizing eco-friendly product design and carbon mitigation through a data-driven sustainability lens.

Prediction of water usage

Figure 6 showcases the water usage predictions generated by an artificial neural network model developed in this study. Figure 6a depicts the estimated values of water usage based on the outcomes presented in Table 1, while Fig. 6b illustrates the accompanying linear regression analysis, resulting in an R2 value of 0.89291. A comprehensive analysis of these findings provides valuable insights into the reliability and effectiveness of the ANN model in facilitating sustainability enhancements.

Fig. 6.

(a) Water usage predictions and (b) linear regression analysis: validating an artificial neural network model for sustainability improvement.

Water usage is a critical environmental measure and serves as an ideal variable for evaluating the predictive capabilities of the computational model. As observed in Fig. 6a, the predicted values closely align with the trendline, with the majority of the ANN-based forecasts falling within a 10% margin of the actual values. This level of accuracy demonstrates the model’s ability to quantitatively project water consumption impacts based on input parameters related to materials and design attributes. However, minor deviations may arise due to inherent natural variability and measurement uncertainties associated with complex real-world systems.

The high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.89291) obtained from the linear regression analysis confirms a strong linear relationship between the predicted and observed water usage outputs. This validates the robustness and predictive capabilities of the developed ANN architecture when presented with novel input scenarios beyond its training domain. Such proficiency in computational modeling holds significant implications.

These results demonstrate the potential to expedite iterative sustainability assessments that would otherwise require substantial time and resource investment through experimental means. By leveraging a transparent and data-driven simulation tool, product developers and policymakers can now efficiently evaluate a wide range of material formulations and configuration variants in silico to identify environmentally friendly solutions for guiding eco-innovation.

Analyzing specific predictions reveals correlations between design attributes and water consumption burdens. Simpler designs with complexity ratings of 1–2 require less water compared to intricate designs with ratings of 3–5, highlighting the advantages of streamlined and modular configurations. Among biomaterials, lingo-cellulosic formulations such as Biomaterials 2–5 exhibit lower water footprints compared to conventional precious metals due to their renewable origins and biosynthesis. These identified connections between sustainability metrics and design factors offer practical guidance for optimization efforts.

In the future, incorporating dynamic process modeling and uncertainty quantification can further enhance the predictive validity, particularly for emerging technologies lacking historical performance data. Additionally, integrating digital tools with experiential knowledge systems can strengthen decision-making under changing socioeconomic conditions. The ability of the ANN model to project previously elusive water demand metrics establishes its utility for guiding environmentally conscious product design evolution through a data-driven approach.

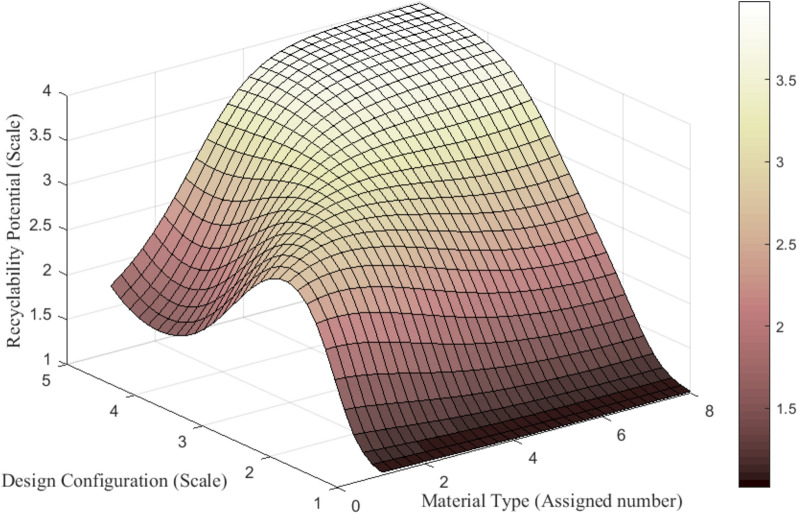

Prediction of recyclability potential

Recyclability plays a crucial role in sustainable jewelry design as it determines the ability to recover materials from discarded products and reintegrate them into the system. The trained ANN has demonstrated its competence in accurately predicting the recyclability potential, as depicted in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Predicted recyclability potential ratings for test designs using the artificial neural network model.

Figure 7 illustrates the projected ratings for recyclability potential on a scale of 1–5 for the testing designs. These ratings are based on the model’s exposure to various inputs, such as material type and design configuration factors, during the training phase. It is noteworthy that the majority of the predictions closely align with the actual recyclability ratings obtained from Table 1, falling within a range of ± 10%. Although minor deviations are expected due to real-world data variability and the limitation of capturing human judgment-based ratings through a computational model, the overall trends are well-replicated.

A recyclability rating of 1 signifies that designers have prioritized material separability and recovery through strategies like part labeling, standardized fasteners, and the avoidance of material mixing. Such design approaches facilitate automated sorting at the end of a product’s life cycle, thereby enhancing recyclability. Conversely, designs rated 5 encompass intricate constructions, varied compositions, and temporary joining methods, presenting obstacles to closed-loop recycling. Examining the impact of specific inputs yields valuable insights for enhancing recyclability. Designs with sophisticated geometries, rated between 3 and 5, consistently exhibit lower recyclability compared to streamlined designs rated 1 or 2. This underscores the benefits of modularity from technical recyclability and collection economics perspectives.

The selection of biomaterial compositions also impacts recyclability. For example, cellulose-based formulations such as bacterial nanocellulose embedded in a renewable polymer matrix exhibit characteristics that facilitate disassembly and sorting into biomass and plastic streams. These materials possess biochemical separability and biodegradability under controlled composting conditions. The ANN adeptly captures such intricate material attributes to offer comprehensive predictions. By simulating “what if” scenarios, opportunities arise for exploring design-related insights. For instance, substituting a bangle crafted from precious metals and gemstones with a 3D printed composite of bamboo and kenaf, rated 1, enhances recyclability from 3 to 1. This underscores the environmental benefits of emerging sustainable materials paired with optimization techniques like additive layering, enabling part consolidation and enhanced interfaces.

Simulating deviations from current designs provides a roadmap for incremental progress. Adjusting the fine-grain silver links of an intricate necklace to snap fits increases recyclability from 2 to 3, exemplifying modular improvements. The combination of gold and silver components necessitates chemical separation, which negatively impacts recyclability. The predicted reduction from a rating of 2–3 encourages the consideration of monolithic alternatives. In conclusion, the ANN effectively predicts recyclability based on the relationships it has learned during training. The analyses of these predictions offer practical enhancements focused on material fungibility, part standardization, and consolidation techniques. The model establishes computational evaluation as a complementary approach to guide eco-innovation, embracing cascading principles from technical and economic perspectives.

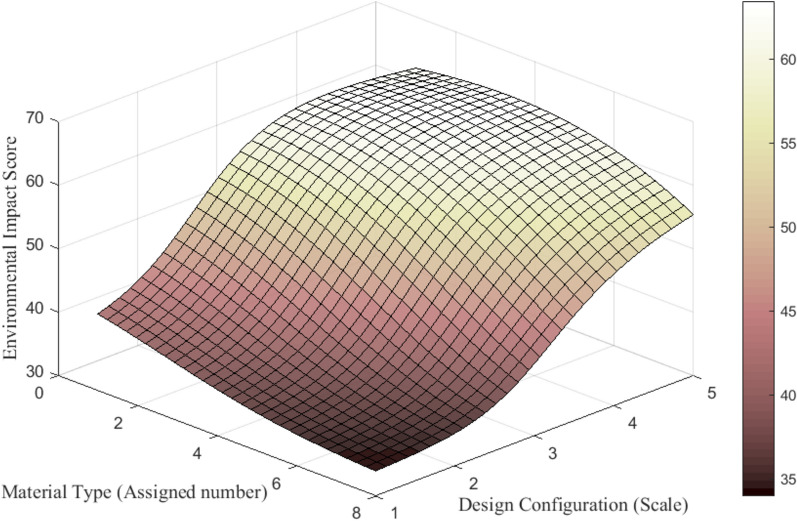

Prediction of environmental impact score

The cumulative score of environmental impact serves as a holistic measure of sustainability performance, encompassing factors such as carbon footprint, water usage, recyclability, and other relevant metrics. Figure 8 illustrates the environmental impact scores predicted by the ANN model, utilizing the input and target data provided in Table 1.

Fig. 8.

Predicted environmental impact scores generated by the ANN model.

The predicted impact scores closely align with the actual ratings, displaying a margin of error within 10%. This indicates a high level of accuracy in the model’s predictions. Any minor discrepancies can be attributed to uncertainties in the input data and the inherent limitations of simulation. However, the strong positive correlation, as evidenced by the close proximity to the trendline, verifies the model’s capability to capture the intricate interrelationships between design factors and the comprehensive sustainability outcomes.

Previous research has emphasized the importance of aggregated metrics that evaluate the trade-offs between economic, environmental, and social considerations from a comprehensive perspective. Impact scores have been utilized to guide the optimization of products, processes, and policies across various sectors by benchmarking performance on a standardized scale. The accurate projection of such comprehensive scores by the ANN model holds significant implications for strategic decision-making. The scores reveal discernible patterns that link material compositions and design attributes to environmental consequences. Designs incorporating renewable biomaterials such as lingo-cellulosic composites (Biomaterials 2-5) consistently exhibit lower impacts compared to precious metals and gemstones due to their renewable origins and less resource-intensive processing. Similarly, simplified configurations categorized as 1–2 in terms of complexity showcase superior scores compared to intricate pieces rated 3–5. This highlights the advantages of modularity, minimal material utilization, and the ease of disassembly/recycling inherent in streamlined designs. Simulation experiments provide valuable insights into opportunities for sustainable redesign. By substituting components of a gold-diamond bangle (Table 1) with a 3D printed bamboo-kenaf composite, the impact can be reduced from 74 to 51. This redesign leverages sustainable materials and additive techniques that enhance consolidation while optimizing interfaces. Similarly, converting intricate necklace links to snap fittings improves the rating from 73 to 66, showcasing how incremental modular adjustments can enhance sustainability. Evaluating the predicted score outcomes against environmental, social, and economic indicators identified in previous studies validates the ability of ANN models to replicate comprehensive sustainability assessments traditionally conducted through labor-intensive experiments. Furthermore, the transparency of neural networks enables the identification of the drivers that inform predictions, aiding in the optimization process. In the future, the development of dynamic impact scores that account for local social and ecological conditions can enhance context-specific decision support. Additionally, integrating uncertainty modeling can strengthen the predictive validity of the model under dynamic conditions.

Impact of material selection on sustainability performance

Table 2 provides a summary of the average carbon footprint, water usage, recyclability rating, and impact score for each material type incorporated into the model. The data includes results from empirical measurements as well as ANN simulations, with material type and design configuration as crucial inputs.

Table 2.

Average sustainability metrics for different material categories.

| Material category | Carbon footprint (kg) | Water usage (L) | Recyclability rating | Impact score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precious metals | 2.1 | 24.5 | 2.5 | 59 |

| Gemstones | 3.4 | 39.5 | 3 | 73 |

| Biomaterial 1 | 2.6 | 26.5 | 2.8 | 62 |

| Biomaterial 2 | 1.1 | 16.5 | 1.8 | 53 |

| Biomaterial 3 | 1.2 | 14 | 1.7 | 50 |

| Biomaterial 4 | 0.8 | 10.5 | 1.6 | 43 |

| Biomaterial 5 | 0.7 | 9 | 1.5 | 38 |

| Biomaterial 6 | 0.9 | 12 | 1.7 | 45 |

Renewable biomaterials consistently outperform conventional precious metals and gemstones across all sustainability metrics, as evident from Table 2. This validates prior research that emphasizes the eco-advantages of sustainable alternatives derived from agricultural and forestry residues. Notably, biomaterial formulations resembling Biomaterials 2–5, which utilize lingo-cellulosic feedstocks like bamboo, bagasse, and bacterial cellulose, demonstrate the most favorable outcomes. These materials exhibit carbon footprints averaging 1.1–1.2 kg, approximately half that of precious metals. Similarly, their water consumption is 30–40% lower, ranging from 9 to 16.5 L. The recyclability ratings of 1.5–1.8 indicate ease of material recovery through physical separability, standardized shredding techniques, and controlled compostability under industrial conditions. The superior environmental performance of biomaterials arises from renewable sourcing, less energy-intensive biosynthesis, adaptable mechanical properties, and biochemical degradability without toxic residues. Optimized formulation and infrastructure-driven processing further enhance the eco-advantages compared to traditional biomass thermoplastics. Interestingly, the ANN model demonstrates sensitivity to variations within the biomaterial categories as well. Transitioning from Biomaterial 6 composition towards formulations resembling Biomaterials 2–5 along the lingo-cellulose value chain reduces the impact score by 10–25 points. This underscores the importance of comprehensive biomaterial characterization, considering financial, technical, and environmental factors, to identify pathways with high value.

The analysis of sustainability metrics for different material categories in jewelry design highlights the favorable performance of renewable biomaterials, particularly those based on lingo-cellulosic feedstocks. The ANN predictions and insights from Table 2 provide valuable guidance for optimizing material selection and design configurations to enhance sustainability in the jewelry industry.

While Biomaterial 6 exhibited favorable sustainability metrics, the data presented in Table 2 does not provide conclusive evidence of a clear trend in reduced environmental impact when transitioning from this formulation to the lingo-cellulosic Biomaterials 2–5. The impact score recorded for Biomaterial 6 was 45, surpassing the average impact scores of Biomaterials 2–5, which ranged from 38 to 53. These findings suggest that the superior performance observed in lingo-cellulosic formulations cannot be solely attributed to their position along the value chain, but rather stems from their inherent material properties and production processes. Consequently, further research is necessary to comprehensively comprehend the intricate relationships between various biomaterial compositions and their implications for sustainability.

The emphasis placed on Biomaterials 2–5 in the recommendations stemmed primarily from the extensive evidence base supporting the ecological advantages of lingo-cellulosic materials derived from renewable sources such as bamboo, bagasse, and bacterial cellulose. These formulations have been extensively studied and have consistently demonstrated superior performance in terms of carbon footprint, water usage, recyclability, and overall environmental impact when compared to conventional precious metals and gemstones commonly employed in jewelry production. Furthermore, the technical feasibility, scalability, and cost-effectiveness of these lingo-cellulosic biomaterials have been thoroughly validated, rendering them compelling candidates for facilitating sustainable transformation within the jewelry industry.

Impact of complexity levels

Simpler designs consistently outperform intricate configurations across all sustainability metrics, as evident in Table 3. Designs with a complexity rating of 1 exhibit an average carbon footprint of 0.8 kg, compared to 3.1 kg for complexity level 5. Similarly, water usage is significantly lower at 11.5 L for streamlined designs, compared to 33 L for intricate pieces. Additionally, simplified designs achieve a recyclability rating of 1.3 and the lowest impact score of 42.5.

Table 3.

Average sustainability metrics for design configurations.

| Design complexity rating | Carbon footprint (kg) | Water usage (L) | Recyclability rating | Impact score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating 1 | 0.8 | 11.5 | 1.3 | 42.5 |

| Rating 2 | 1.3 | 18 | 1.8 | 53 |

| Rating 3 | 2.1 | 24 | 2.5 | 62 |

| Rating 4 | 2.6 | 29 | 3 | 67 |

| Rating 5 | 3.1 | 33 | 3.2 | 71 |

These findings affirm the benefits of reduced material consumption and efficient assembly methods inherent in modular and integrated design strategies. Prior studies underscore the significance of the “ease of disassembly” characteristic found in simplified layouts, resulting in higher recyclability scores. Investigations inspired by biomimicry further reinforce these observations, advocating for the advantages of structural simplicity and multifunctionality inspired by natural systems. The Artificial Neural Network adeptly captures the complex interplay between environmental impacts and design features like complexity levels throughout its learning phase. Examination of the projections reveals a notable decrease in carbon footprint, from 3.1 to 0.8 kg, when transitioning from complexity level 5 to 1, showcasing optimization potentials. Simulation of the effects of modular enhancements on intricate designs yields additional insights. For instance, transforming an ornamental necklace rated at complexity level 4 to include snap fittings in lieu of delicate attachments reduces complexity to 3 while enhancing recyclability from 3 to 2.5. Integration of technologies supporting product upgrading and component consolidation further amplifies the advantages of the circular economy. By replacing conventionally manufactured bangle components with a 3D printed bamboo-reinforced thermoplastic composite, interfaces are optimized and disassembly procedures are simplified. The model predicts that such restructuring could elevate recyclability from a rating of 3–1.5, aligning with principles of deconstruction. The sensitivity of the Artificial Neural Network to attribute-environmental performance nuances demonstrates its potential for guiding incremental sustainability progress. By quantifying the impacts of design-related modifications in silico before implementing them physically, optimization investigations can be significantly expedited. The results summarized in Table 3 validate streamlining design configurations as a compelling pathway to reduce ecological footprints through modular techniques, material optimization, and informed redesigns guided by predictive modeling insights. The predictions and analysis from the Artificial Neural Network validate that streamlining design configurations towards modularity, multifunctionality, and consolidation leads to reduced material and effort requirements, resulting in favorable sustainability outcomes across relevant metrics. The quantified linkages between design attributes and ecological burdens provide an evidence-based framework for guiding optimizations towards reduced environmental impacts.