Abstract

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) is a complex and progressive disease characterized by elevated pulmonary vascular resistance and right heart failure. Current therapies primarily focus on pulmonary vasodilation; however, novel approaches that target the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms—such as TGF-β signalling, epigenetic alterations, growth factors, inflammation, and extracellular matrix remodelling—are promising alternatives for improving treatment outcomes. This is a review of recent advances in the development of innovative therapeutic strategies for PAH.

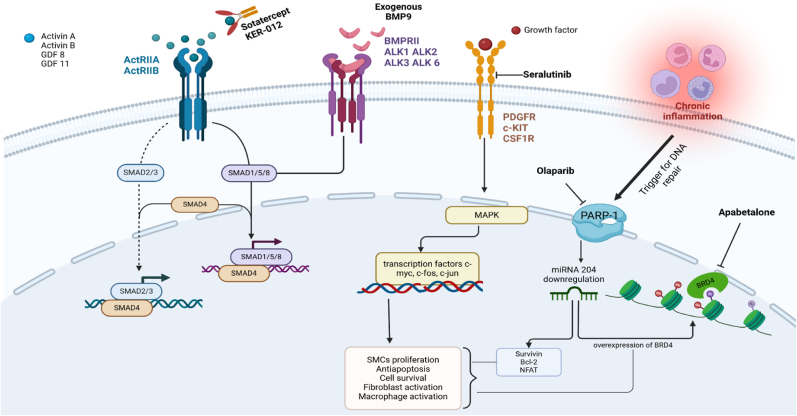

The first section of this paper explores approaches targeting TGF-β signalling, both acting directly on receptors through drugs like Sotatercept and exogenous BMP9, and indirectly, inhibiting the degradation of key receptors, such as BMPR2. Subsequent sections describe treatments that target epigenetic regulators, e.g. poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) inhibitors and direct BRD4 antagonists, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Seralutinib), and therapies aimed at inflammation, such as IL-6 inhibitors, CD-20 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies that prevent macrophage migration. Finally, strategies that target the serotonin pathway, and other metabolic and hormonal pathways are described.

This review includes both preclinical and clinical trial data that support efficacy, safety and the future potential of such therapies. Collectively, these therapeutic approaches can be valuable in treating PAH by targeting multiple aspects of its pathogenesis, potentially resulting in improved clinical outcomes for patients affected by this debilitating, life-limiting condition.

Keywords: Pulmonary arterial hypertension

1. Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare condition characterised by vasoconstriction and remodelling of pulmonary arterioles. The consequent rise in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) results in an increase in right ventricular (RV) afterload that progresses rapidly to heart failure. The associated morbidity and mortality remain considerable, despite recent advances in medical therapies and transplantation.

For the last 30 years, the mainstay of treatment of PAH have been drugs targeting endothelial dysfunction, i.e. pulmonary vasodilators. In the healthy pulmonary vasculature, the tone of the arterioles is maintained by endothelial derived mediators such as endothelin-1 (ET-1), nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin (PGI2). ET-1 is a vasoconstrictor and mitogen, whereas NO and PGI2 are vasodilators and have anti-proliferative and anti-platelet actions [1]. In PAH there is an excess of ET-1 production and a relative deficiency of NO and PGI2.

The three main classes of pulmonary vasodilators are.

-

-

ET-1 receptor antagonists;

-

-

Drugs that enhance the NO pathway (through production of cyclic GMP)- phosphodiesterase inhibitors and soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators; and

-

-

Drugs that enhance the PGI2 pathway, including prostacyclin itself, analogues of PGI2, and agonists of the PGI2 receptor (IP).

Use of these drugs has resulted in a reduction in morbidity and mortality, with the median survival improving from 2.8 years to 6–8 years in the latest registries [[2], [3], [4]].

Despite this, both morbidity and mortality remain unacceptably high. Although some, or all, of the pulmonary vasodilators may influence remodelling of the pulmonary vascular bed in in-vitro models, their main clinical action is considered to be vasodilation. However, pathological specimens do indicate that the main pathological feature of PAH is remodelling, at least in advanced cases where specimens are most often available [1]. Such remodelling includes abnormal proliferation of all three layers of the vessel; endothelium, smooth muscle and adventitia (Fig. 1). Much work has been performed aimed at understanding the molecular pathways underlying pulmonary vascular remodelling in PAH and, in particular, those responsible for cell proliferation and apoptosis. These pathways involve: 1. The transforming growth factor-beta superfamily signalling; 2. Epigenetic mechanisms; 3. Growth factor signalling; 4. Inflammation; and 5. Hormonal and metabolic signalling.

Fig. 1.

Illustrates the TGF-β signalling pathways, which is divided into the Smad 1/5/8 and Smad 2/3 branches. Under normal conditions, these pathways are balanced. However, in PAH there is a shift towards the predominance of the Smad 2/3 pathway, leading to remodelling of pulmonary arterioles. This remodelling includes the abnormal proliferation of all three layers of the vessel: the endothelium, smooth muscle, and adventitia.

The following sections summarise the evidence supporting involvement of these processes and pathways in the pathogenesis of PAH, and associated therapeutic strategies, including current and upcoming trial data where available.

2. Therapeutic strategies targeting TGF-β signalling

The transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily consists of two major pathways: the TGF-β–activin–nodal branch and the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)–growth differentiation factor (GDF) branch. The first group includes the ligands TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3, activins A (ActA) and B, and GDF 1, 3, 9, 10, and 11, which interact with the receptors TGF-β2RII, ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7 [5]. The second group encompasses most BMP ligands (including BMP9) and GDF 5, 6, and 7, binding to the receptors BMPR2, ALK1, ALK2, ALK3, and ALK6. The TGF-β–activin–nodal branch activates the Smad 2/3 pathway, while the BMP-GDF branch activates the Smad 1/5/8 pathway [5].

In PAH, there is a notable dysregulation of TGF-β signalling, with predominance of Smad 2/3 signalling over Smad 1/5/8. This imbalance is thought to contribute to endothelial dysfunction, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and excessive deposition of the extracellular matrix [6]. (Fig. 1) One of the best-known causes of imbalance between these two pathways are mutations of the BMPR2 gene, which cause a reduction in the activation of the Smad 1/5/8 pathway. Mutations of this gene have been strongly implicated in the development PAH, and are present in the majority (75 %) of heritable PAH cases and up to 40 % of idiopathic PAH cases [7,8].

Consequently, recent research has focused on targeting the TGF-β signalling pathways through cell membrane receptors or within the cell (e.g. at the level of the DNA, cytoplasm, or lysosomes) to restore the proliferative/anti-proliferative balance. This has already led to a recently approved drug, Sotatercept, and has opened the door to further therapeutic targets for PAH, discussed below [9].

2.1. Targeting TGF-β signalling through cell membrane receptors

2.1.1. Activin receptors

2.1.1.1. Sotatercept

Sotatercept is a humanised fusion protein that sequesters the ligands Activin A/B and GDF 8/11 which bind to activin type IIA receptor (ActRIIA), thereby reducing ActRIIA–Smad2/3 signalling, and shifting the balance towards antiproliferative pathways (Fig. 2). Previous work by Yung et al. reported that expression of Activin A and GDF 8/11 was increased in patients with PAH and animal models. Using a potent ligand trap (ActRIIAFc) against Activin A and GDF-8/11, the authors demonstrated reduced proliferation of endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vitro and improved hemodynamics, RV hypertrophy, RV function, and arteriolar remodelling in PAH animal models [10]. Subsequent published studies have reported promising results with this novel therapy.

Fig. 2.

Illustrates various therapeutic approaches in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Sotatercept, a fusion protein, binds to ligands of Activin receptors, preventing activation of the ActRIIA and ActRIIB receptors and inhibiting the Smad 2/3 pathway. Exogenous BMP9 enhances the Smad 1/5/8 pathway, particularly in cases of BMPR2 deficiency. Seralutinib blocks growth factor binding to PDGF, c-kit, and CSF1 receptors, inhibiting the MAPK pathway and reducing the transcription of c-fos, c-jun, and c-myc, which are involved in antiapoptosis and cell proliferation. Chronic inflammation activates PARP1, leading to downregulation of miRNA-204, which in turn increases BRD4 expression and promotes antiapoptotic effects. Olaparib and apabetalone inhibit BRD4 effects indirectly and directly, respectively. BMP9: Bone Morphogenetic Protein 9, BMPR2: Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor Type 2, PDGF: Platelet-derived Growth Factor, c-kit: Tyrosine kinase receptor, CSF1: Colony Stimulating Factor 1, MAPK: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase, PARP1: Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase 1, miRNA-204: MicroRNA 204, BRD4: Bromodomain Containing 4.

The PULSAR study was a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial assessing the efficacy and safety of Sotatercept in 106 patients with WHO Group 1 PAH on stable background pulmonary vasodilator therapy. It included a 24-week placebo-controlled phase followed by an 18-month active treatment extension, with the primary outcome being change in PVR from baseline [11]. Results showed a significant reduction in PVR for the Sotatercept group compared to placebo, with least-square mean differences of −146 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ (95 % confidence interval (CI), −241.0 to −50.6; p = 0.003) and −240 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ (95 % CI, −329.3 to −149.7; p < 0.001) in patients who received the doses of 0.3 mg/kg and 0.7 mg/kg, respectively, compared to the placebo group. Moreover, improvements in the 6-min walk distance (6MWD) were observed, with least-squares mean differences of 29.4 m for the lower dose group and 21.4 m for the higher dose group. A significant reduction in NT-proBNP levels was noted. The most common adverse event was thrombocytopenia, occurring in 12 % of patients receiving the higher dose, while haemoglobin (Hb) levels increased in 3 %–17 % of patients, with the highest increase observed in the 0.7 mg/kg group [11].

During the extension phase, participants who were initially allocated to placebo and thereafter received active treatment demonstrated a significant reduction of −219.5 (43.7) dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ (p < 0.0001) [12] The drop in PVR in this group was similar to that achieved by patients allocated to the active arm (between-group difference in PVR of −13.3 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵, p = 0.79). Secondary endpoints were also met, including improvements in 6MWD (increased from a mean ± SD of 409 ± 66 m to 480 ± 73 m, p < 0.001), and WHO-FC (improved from a mean ± SD of 2.4 ± 0.5 to 1.9 ± 0.6, p < 0.001), similar to the group allocated to active treatment. In terms of safety, 4.8 % participants reported treatment-emergent adverse events (AE) considered related to the study drug. Telangiectasia was reported as a new event in 11 % of participants after 1.5 years of treatment and was, therefore, added as an adverse event of special interest (AESI) for phase 3 studies of Sotatercept [12].

In the phase 2 SPECTRA trial, Sotatercept improved peak oxygen uptake, 6MWD, and resting and peak exercise hemodynamics assessed through invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing (iCPET), with a mean change of 102.74 mL/min (95 % CI, 27.72–177.76; p < 0.001) after 24 weeks of treatment [13]. Similarly, an ongoing trial at the Mayo clinic (NCT06409026) will assess iCPET performance after 36 weeks of therapy [14].

Building on the PULSAR trial, the phase III STELLAR trial was a double-blind study in which 324 patients with PAH classified as WHO-FC II or III and on stable background PAH therapy were randomized to receive either Sotatercept or placebo [15]. The primary endpoint of the trial was the change in 6MWD at week 24. The median change from baseline in 6MWD was 34.4 m (95 % CI, 33.0 to 35.5) in the Sotatercept group compared to 1.0 m (95 % CI, −0.3 to 3.5) in the placebo group, with a location shift of 40.8 m (95 % CI, 27.5 to 54.1; p < 0.001), favouring Sotatercept. Other secondary endpoints included a reduction in PVR, with median changes from baseline at week 24 of −165.1 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ (95 % CI, −176.0 to −152.0) in the Sotatercept group and 32.8 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ (95 % CI, 26.5 to 40.0) in the placebo group. Additionally, a significant reduction in NT-proBNP levels were observed, with median changes of −230.3pg/ml (95 % CI, −236.0 to −223.0) for Sotatercept and 58.6 pg/ml (95 % CI, 46.0 to 67.0) for the placebo arm. The study also demonstrated an increased time to clinical worsening or death, with a hazard ratio of 0.16 (95 % CI, 0.08 to 0.35) for the Sotatercept group compared to the placebo group after a median follow-up of 32.7 weeks [15]. In this study, common side effects present in the PULSAR study were confirmed, with epistaxis, telangiectasia, and dizziness more frequent in the Sotatercept group, and an increase in Hb by more than 2.0 g/dL in 12.3 % of patients treated. Thrombocytopenia was present in 6.1 % of the sotatercept group vs 2.5 % of the control group.

The ongoing phase III SOTERIA study (NCT04796337) will evaluate the long-term safety of this drug for up to 50 months in 700 adults with PAH who have previously participated in Sotatercept studies, while also assessing continued efficacy [15]. The ongoing HYPERION trial (NCT04811092) will evaluate the effects of Sotatercept on time to clinical worsening (first confirmed morbidity event or death) in 444 participants newly diagnosed with PAH who are at intermediate or high risk of disease progression [16]. Similarly, the ZENITH trial (NCT04896008) will focus on 166 WHO III or IV FC patients to evaluate the effects of Sotatercept on time to first event for a combined endpoint of all-cause death, lung transplantation, or PAH worsening-related hospitalization ≥24 hours [17].

Interestingly, CADENCE is a trial that will assess the efficacy, safety and tolerability of this therapy in patients with combined pre and post-capillary PH due to HFpEF [18].

2.1.1.2. KER-012

One of the concerns with Sotatercept, and ligand traps in general, is the lack of specificity for ligands, which may lead to unwanted side-effects, such as increase in Hb, thrombocytopenia and telangiectasia. Therefore, there has been a push to develop more tailored ligand traps. An example of this is Ker-012, a fusion protein based on the activin receptor ActRIIB, which preferentially binds activin A and B, GDF8, and GDF11. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that KER-012 did not increase haemoglobin or red cell count in non-human primates. The randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial TROPOS (NCT05975905) will determine the efficacy and safety of KER-012 compared to placebo in adults with PAH and stable background therapy after 24 weeks [19].

2.1.2. BMP 9 signalling

BMP9, also known as GDF2, is a circulating ligand primarily produced in the liver. It binds to the receptors ALK1 and BMPR2 which, as described earlier, are key in the development of PAH. Patients with GDF2 mutations are more likely to develop PAH [20]. Despite great interest, there are as yet only pre-clinical data on BMP9 as a potential treatment target, with contradictory results. As expected, some studies suggest that BMP9 signalling through non-mutated BMPR2 receptors may have beneficial effects in PAH, enhancing overall signalling through the Smad 1/5/8 pathway. Long et al. reported that exogenous BMP9 administration in animal studies improved RV function and reduced pulmonary dysfunction, underlining the potential of BMP9 as a therapeutic agent for balanced TGF-β signalling [21]. (Fig. 2).

On the other hand, Tu et al. demonstrated that the suppression of BMP9 (using anti-BMP9 antibodies) prevented chronic hypoxia-induced PH in animal models, and BMP9 ligand traps reduced the proliferation of pulmonary vascular cells, inflammatory cell infiltration, and reverted PH in vivo [22]. According to the authors, this counterintuitive result could be explained by the complexity of BMP signalling, including the expression of the vasoconstrictor ET-1, and the reduction of the vasodilator apelin [23,24]. Therefore, whether specifically targeting BMP9 will be clinically useful is yet to be determined.

2.2. Targeting TGF-β signalling through the cytoplasm

Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor primarily used as an immunosuppressant in transplant patients, which has been investigated for its potential in PAH. It acts on BMPR2 signalling abolishing the interaction between the receptor and its repressor FKBP12, thus enhancing BMP signalling in the context of BMPR2 deficiency [59]. A phase IIa trial examined the safety of a 16-week treatment with low-level Tacrolimus in PAH patients, but failed to show an effect on symptoms, exercise tolerance, RV function or serological heart failure markers [59].

2.3. Targeting TGF-β signalling through lysosomes and the endoplasmic reticulum

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, primarily known as anti-malarial and immunomodulatory drugs, have gained attention for their potential role in PAH due to their anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative properties. They reduce lysosomal activity, by impairing autophagosome fusion with lysosomes. This leads to accumulation of ineffective autophagosomes, and activation of apoptosis pathways and cell death [25]. In PAH, lysosomal deficiency could be beneficial by reducing BMPR2 degradation and promoting SMCs apoptosis [26]. Indeed, Long et al. demonstrated that chloroquine prevented loss of the BMPR2 protein, reduced autophagy pathways and increased apoptosis of pulmonary artery SMCs in animal models with PAH [27].

Furthermore, particular mutations in BMPR2 involving cysteine residues can cause protein misfolding, leading to retention of BMPR2 in the endoplasmic reticulum [28]. Dunmore et al. have demonstrated that chemical chaperones, like 4-Phenylbutirrate, can restore BMPR2 signalling through SMAD 1/5 in animal models carrying those mutations [29].

The promising STRATOSPHERE 2 study is a randomised placebo-controlled phase II trial, run in the UK, which will evaluate hydroxychloroquine and phenylbutyrate in patients with idiopathic or hereditary PAH caused by mutations in BMPR2 in WHO functional class I-IV and on stable PAH therapy [30].

Another novel approach targeting the degradation of BMPR2 was recently evaluated. E3 ligase inhibitor (Smurf-1) LTP001 targets the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which plays a role in the degradation of BMPR2. Thus, its action is to stabilize BMPR2 and enhance its function. The phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled trial NCT05135000 aimed to explore the efficacy and clinical profile of LTP001 in 44 patients with PAH for 24 weeks, with the possibility of enrolling them in the extension study at the end of 52 weeks [31]. However, the study was terminated early as interim analysis showed no benefit. A new study will soon be conducted using a higher dose of LTP001.

In conclusion, the exploration of TGF-β signalling is leading to new therapeutic strategies for PAH management, with promising recent and ongoing clinical trials.

3. Therapies targeting epigenetic alterations and DNA

Epigenetics is defined as regulation of gene expression without modifying the DNA sequence. Major epigenetic phenomena include DNA methylation, histone modifications via acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, and non-coding RNA modifications [32].

Epigenetic changes can be triggered by diverse causes such as exposure to drugs, environmental changes and inflammation. There is increasing evidence that epigenetic regulation is important in the pathogenesis of PAH.

PAH is associated with chronic inflammation, which is associated with sustained DNA damage and subsequent overexpression of a key enzyme for DNA repair, the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) [33]. PARP-1 activation causes microRNA-204 downregulation, which leads to excessive proliferation and antiapoptosis of pulmonary arterial SMCs through the expression of oncogenes, such as nuclear factor of activated T cells, B-cell lymphoma 2, and Survivin [34]. MicroRNA-204 downregulation leads to sustained cell survival and proliferation and overexpression of the epigenetic reader bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) (Fig. 2) [35]. Directly inhibiting BRD4, or avoiding microRNA-204 downregulation by inhibiting PARP-1 might be beneficial to PAH patients by reducing excessive SMCs proliferation in pulmonary arteries.

Olaparib is a PARP inhibitor used in cancer therapy, including some ovarian, breast, and prostate cancers [36]. The OPTION trial is a multicenter, open-label, phase 1B study, which will assess the safety of Olaparib in PAH patients on stable therapy, as well as its efficacy on haemodynamics by performing cardiac catheterization at baseline and 24 weeks [37].

Apabetalone is an oral small molecule inhibitor of BRD4, which was studied during an open-label, single-arm, 16-week, early phase I trial in addition to usual recommended PAH therapy. Exploratory analysis suggested potential improvements in PVR and cardiac output (−140 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ and +0.73L/min, respectively) [38]. Further evidence is awaited.

4. Therapies targeting growth factors

Other key factors involved in the pathogenesis of PAH include platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R), and stem cell factor receptor (c-KIT). PDGFR activation leads to excessive SMCs proliferation and adventitial fibroblast activation, CSF1R causes macrophage recruitment and activation that contributes to inflammation, and c-KIT is responsible for increasing mast cell survival, further enhancing inflammatory and fibrotic processes in PAH. Thus, all these factors are potential targets for PAH therapies (Fig. 2) [39].

Imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, initially used for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia, targets not only BCR-ABL, but also PDGFR and c-KIT and has, thus, been investigated as a potential PAH treatment. The IMPRES phase III clinical trial demonstrated that Imatinib reduced pulmonary arterial pressure, PVR and improved exercise capacity. Notably, many of the patients included were already on triple background therapy and had severe PAH. However, concerns about its safety and tolerability were raised, with the most frequent AEs being nausea, peripheral oedema, diarrhoea, vomiting, and periorbital oedema. Importantly, subdural hematomas occurred in 4.2 % of patients, all of whom were receiving concurrent anticoagulation therapy (a standard of therapy at the time) [40]. This tempered commercial interest in Imatinib at the time. However, a UK study, PIPAH, is now investigating optimal dosing of Imatinib in PAH patients who are not on anticoagulation [41].

Seralutinib targets the same receptors as Imatinib but is administered as an inhalant, acting directly on the pulmonary vasculature, and potentially minimizing side effects. Preclinical studies in rodent models have shown that Seralutinib reduced pulmonary artery wall thickness, decreased SMCs proliferation and lowered inflammation in lung tissues. It also reduced PAP and RV hypertrophy, suggesting that it not only inhibits key pathways driving PAH, but may also reverse some pathological changes in the pulmonary vasculature [42]. The pivotal phase II trial, TORREY, evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of inhaled Seralutinib in 80 patients with PAH, WHO-FC class II and III, already on stable PAH therapy [43]. The least squares mean change from baseline to week 24 in PVR was −96.1 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ (95 % CI -183.5 to −8.8; p = 0.03) between the Seralutinib and the placebo groups. Cough was a common side effect, present in 44 % of patients treated (but was also reported in 38 % of patients receiving placebo). Interim results from the open-label extension of this study have shown good tolerance for up to 72 weeks, with the most common AEs being headache and cough. These AEs led to study discontinuation in 24.3 % of patients, with rare cases of temporary transaminitis also noted. In the Seralutinib continuation group, PVR decreased further from week 24 to week 72 (median change −47.5 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵); in the placebo-to-Seralutinib group the median change was −47.0 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ [44].

The phase 3 study PROSERA trial will evaluate whether Seralutinib improves exercise capacity after 24 weeks. This will be the first trial to also assess time to clinical worsening, defined as death from any cause, hospitalization for worsening of PAH, the need to increase the dose or type of PAH therapies, and other important clinical outcomes. An open-label extension study will evaluate long-term safety, tolerability, and the efficacy of inhaled Seralutinib in subjects who have completed the previous study, focusing on AEs from baseline up to 4 years [45].

5. Therapies targeting inflammation

Chronic inflammation caused by cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6), is another mechanism implicated in the pathogenesis of PAH. Moreover, cytokine levels have been shown to negatively correlate with prognosis in idiopathic and heritable PAH [46]. A phase 2 open-label trial conducted in the UK evaluated the safety and efficacy of the IL-6 receptor antagonist Tocilizumab in PAH patients over a 6-month period. While the adverse events observed were consistent with previously known effects, there was no significant change in PVR from baseline after treatment [47]. Interestingly, an ongoing trial called SATISFY-JP is targeting immune-responsive phenotypes by assessing the efficacy of Tocilizumab in group 1 PAH patients with elevated IL-6 levels. This trial will measure changes in PVR and 6MWD from baseline to 24 weeks [48].

Rituximab targets inflammation by directly acting on the CD20 receptor present on B cells, which are implicated in autoimmune conditions, such as systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which are often associated with PAH [49]. A prospective, multicentre, phase 2 randomized trial assessed the safety and efficacy of Rituximab in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated PAH without severe interstitial lung disease. Although the treatment was deemed safe, it did not significantly improve the primary endpoint of 6MWD compared to the control group (p = 0.12), nor did it show a significant change in PVR after 24 weeks [50]. An ongoing single-centre trial is evaluating the safety and efficacy of Rituximab in 50 patients with PAH associated with SLE [51].

Novel therapies targeting inflammation include cardiosphere-derived cells, which are multipotent cells that secrete exosomes capable of influencing other cells through epigenomic and transcriptomic mechanisms [52]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated their anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects in PAH [53]. A phase 1a and 1b study evaluated the safety of this therapy in 26 patients with various forms of PAH. Exploratory endpoints included RV volumes, exercise capacity, diffusing capacity, and hemodynamics; findings were encouraging though preliminary, supporting further investigation in future trials [54].

6. Therapies targeting extracellular matrix and vascular smooth muscle proliferation

Neutrophils are well-known for their role in the pathogenesis of PAH. They contribute to this process by releasing elastase, which degrades the extracellular matrix, and leads to subsequent remodelling, through migration and proliferation of SMCs and fibroblasts [55]. In PAH patients, there are elevated levels of neutrophil elastase and reduced levels of its endogenous inhibitor, elafin. This imbalance is associated with a more severe clinical presentation and worse laboratory, imaging and hemodynamic findings [56]. A small phase I trial assessed the safety and tolerability of elafin (Tripelestat) in 30 healthy volunteers, supporting further investigation in a phase II trial [57].

Another promising therapy is the monoclonal antibody ZMA001, which prevents monocytes and macrophages from migrating and contributing to pulmonary vascular remodelling. A phase 1 randomized, double-blind study will investigate the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of intravenous ZMA001 in 96 healthy subjects [58].

7. Therapies targeting the serotonin pathway

Serotonin, a neurotransmitter and autacoid, contributes to the proliferation and contraction of SMCs in the pulmonary vasculature. The enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) mediates the conversion of tryptophan to serotonin and is overexpressed in the pulmonary endothelial cells of patients with PAH [60].

The ELEVATE 2 trial investigated Rodatristat, a potent peripheral inhibitor of TPH1. This phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study evaluated changes in PVR as the primary endpoint, while secondary endpoints included changes in 6MWD, NT-proBNP levels, and echocardiographic indicators of disease progression over a 24-week period [61]. Disappointingly, the results were negative: the least-squares mean change in PVR from baseline to week 24 was 339.0 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ (95 % CI 79.4–651.4, p = 0.012) for the Rodatristat 300 mg group, while the 600 mg group had a mean increase of 425.7 dyn·sec·cm⁻⁵ (mean difference of 452.1 [95 % CI 168.3–735.9], p = 0.018) compared to placebo. Additionally, there were increases in NT-proBNP and right atrial pressure, along with decreases in stroke volume and cardiac index. These findings suggest that serotonin exerts a dual role in PAH patients, leading to hyperproliferation of SMCs, but also contributing to myocardial contractility. Thus, reducing serotonin concentration in this setting may have detrimental effects [62].

8. Novel therapies for “old” pathways

Soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) is a well-established target for treating PAH, as it activates cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which leads to the relaxation of SMCs. sGC can be targeted indirectly through nitric oxide (NO) activation or directly with sGC stimulators. Riociguat is approved for PAH and CTEPH in cases where pulmonary endoarterectomy (PEA) is not feasible or when patients have persistent or recurrent PH after PEA [63]. However, NO primarily stimulates sGC when it is in its heme-containing form. In conditions of oxidative stress, sGC can lose its heme and converts to an unresponsive isoform known as heme-free apo-sGC. This shift can reduce the effectiveness of vasodilator therapies that involve NO and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE5i) [64]. To address this issue, a phase I trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of inhaled Mosliciguat, an sGC activator that binds specifically to the heme-free apo-sGC causing its activation in animal models [65]. Experiments showed that inhaled Mosliciguat had the same efficacy on PAP as inhaled iloprost, bosentan or sildenafil, with no negative effect on blood pressure, therefore overcoming potential treatment limitations of conventional PAH therapies.

Prostacyclin has an established role in the management of PAH. When its receptor is activated, prostacyclin initiates a G-protein coupled signalling cascade that results in an increase in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). This increase in cAMP causes vasodilation, inhibition of SMC proliferation, platelet aggregation suppression and modulation of inflammatory responses [66]. Ralinepag is a novel oral prostacyclin analogue that differs from existing therapies, such as selexipag and treprostinil, by having an extended terminal half-life of 24 hours, thus minimizing fluctuations in plasma concentrations. In a double-blind Phase 2 clinical trial, Ralinepag demonstrated significant efficacy, meeting its primary endpoint by achieving a least-squares mean change in PVR of −29.8 % compared to placebo (p = 0.03), with a lower likelihood of deterioration in functional class [67]. A phase 3 trial is currently under way to further assess the efficacy and safety of this therapy in a cohort of 1000 patients with Group I PAH, with the primary endpoint of time-to-first clinical worsening [68].

9. Miscellaneous

Table 1 presents recent and ongoing trials analysing novel therapies for PAH targeting hormonal and metabolic pathways. Notably, some trials have been prematurely terminated due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1.

Recent or ongoing trials targeting hormonal, metabolic or miscellaneous pathways.

| DRUG | MECHANISM OF ACTION | TRIAL NAME | PHASE | SAMPLE SIZE | PRIMARY OUTCOME | STATUS | RESULTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormonal pathway | |||||||

| Fulvestrant | Blockade of estrogen receptor α | NCT02911844 | 2 | 5 | Change from baseline, 9 weeks, of: - Plasma Estradiol Levels - TAPSE - 6MWD - NT-proBNP level |

Completed | No primary outcomes met |

| Anastrozole | Aromatase inhibitor | PHANTOM (NCT03229499) | 2 | 84 | Change from baseline in 6MWD, 6 months | Completed | No primary outcome met |

| Tamoxifen | Selective estrogen receptor modulator | NCT03528902 | 2 | 18 | Change in TAPSE, 24 weeks | Completed | Not available |

| DHEA | Involved in sexual hormone biosynthesis | NCT03648385 | 2 | 24 | Change in RV longitudinal strain measured by cardiac MRI, 18 weeks | Active, not recruiting | Not available |

| Metabolic pathway | |||||||

| Metformin | Anti-diabetic | NCT03349775 | 1 | 21 | Change in rest mPAP, 3 months Change in peak exercise mPAP/CO, 3 months |

Terminated | No primary outcomes met |

| Metformin | Anti-diabetic | NCT03617458 | 2 | 73 | Change in 6MWD, 12 weeks Change in WHO-FC, 12 weeks |

Active, not recruiting | Not available |

| Dapagliflozin | Anti-diabetic, pleiotropic effect | NCT05179356 | 2 | 52 | Change in VO2 max, 3 months | Recruiting | Not available |

| Empagliflozin | Anti-diabetic, pleiotropic effect | NCT05493371 | 2 | 8 | Safety, tolerability, feasibility, 12 weeks | Recruiting | Not available |

| Empagliflozin | Anti-diabetic, pleiotropic effect | NCT06554301 | 1 | 72 | Change in 6MWD, 12 weeks | Not yet recruiting | Not available |

| Other | |||||||

| Pemziviptadil | Vasoactive intestinal peptide type II receptor agonists | NCT03556020 | 2 | 35 | Safety, tolerability, change in PVR, 16 weeks | Terminated | Not available |

TAPSE: Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion, 6MWD: 6-Minute Walk Distance, mPAP: Mean Pulmonary Arterial Pressure, WHO-FC: World Health Organization Functional Class, PVR: Pulmonary Vascular Resistance, DHEA: Dehydroepiandrosterone.

10. Concluding remarks

The exploration of novel therapeutic strategies in PAH is expanding rapidly, with promising preclinical and clinical data suggesting that some of these therapies may offer significant improvements over current treatments. Targeting key molecular pathways involved in vascular remodelling, such as TGF-β signalling, growth factors and epigenetic regulators, represents a paradigm shift in PAH treatment. Although many of these therapies are still in early clinical stages, some have demonstrated the potential to offer more targeted and personalized approaches. However, continued research is required to optimize dosing, evaluate long-term safety and determine the most appropriate patient populations for each therapeutic approach.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Giulia Guglielmi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Konstantinos Dimopoulos: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. S. John Wort: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:John Wort reports a relationship with Janssen, Ferrer, MSD that includes: funding grants and travel reimbursement. Konstantinos Dimopoulos reports a relationship with Janssen-Cilag Ltd that includes: speaking and lecture fees. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

John Wort and Konstantinos Dimopoulos serve the IJCCHD Editorial Board but had no involvement with the handling of this paper.

References

- 1.Humbert M., Guignabert C., Bonnet S., et al. Pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension: state of the art and research perspectives. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01887-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Alonzo G.E., Barst R.J., Ayres S.M., et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(5):343–349. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendriks P.M., Staal D.P., van de Groep L.D., et al. The evolution of survival of pulmonary arterial hypertension over 15 years. Pulm Circ. 2022;12(4) doi: 10.1002/pul2.12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucly A., Weatherald J., Savale L., et al. External validation of a refined four-stratum risk assessment score from the French pulmonary hypertension registry. Eur Respir J. 2022;59(6) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02419-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guignabert C., Humbert M. Targeting transforming growth factor-β receptors in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(2) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02341-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rol N., Kurakula K.B., Happé C., Bogaard H.J., Goumans M.J. TGF-Β and BMPR2 signaling in PAH: two Black sheep in One family. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(9):2585. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machado R.D., Eickelberg O., Elliott C.G., et al. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1, Supplement):S32–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morisaki H., Nakanishi N., Kyotani S., Takashima A., Tomoike H., Morisaki T. BMPR2 mutations found in Japanese patients with familial and sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension. Hum Mutat. 2004;23(6):632. doi: 10.1002/humu.9251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunmore B.J., Jones R.J., Toshner M.R., Upton P.D., Morrell N.W. Approaches to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension by targeting BMPR2: from cell membrane to nucleus. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117(11):2309–2325. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yung L.M., Yang P., Joshi S., et al. ACTRIIA-Fc rebalances activin/GDF versus BMP signaling in pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(543) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz5660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humbert M., McLaughlin V., Gibbs J.S.R., et al. Sotatercept for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(13):1204–1215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humbert M., McLaughlin V., Gibbs J.S.R., et al. Sotatercept for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: PULSAR open-label extension. Eur Respir J. 2023;61(1) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01347-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waxman A.B., Systrom D.M., Manimaran S., de Oliveira Pena J., Lu J., Rischard F.P. SPECTRA phase 2b study: impact of sotatercept on exercise tolerance and right ventricular function in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Heart Fail. 2024;17(5) doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.123.011227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy Y. clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. Effect of sotatercept on central cardiopulmonary performance and peripheral oxygen transport during exercise in pulmonary arterial hypertension.https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06409026 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoeper M.M., Badesch D.B., Ghofrani H.A., et al. Phase 3 trial of sotatercept for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1478–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2213558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acceleron Pharma, Inc. clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. A wholly-owned subsidiary of merck & Co., inc., Rahway, NJ USA. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Study to evaluate sotatercept when Added to background pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) Therapy in newly diagnosed intermediate- and high-risk PAH patients.https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04811092 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acceleron Pharma, Inc. A wholly-owned subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ USA. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Study to evaluate sotatercept when Added to Maximum Tolerated background Therapy in participants with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) World Health Organization (WHO) functional class (FC) III or FC IV at high risk mortality. clinicaltrials.gov. 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04896008

- 18.Acceleron Pharma, Inc. clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. A wholly-owned subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ USA. A phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Effects of sotatercept versus Placebo for the Treatment of combined Postcapillary and Precapillary pulmonary hypertension (Cpc-PH) Due to heart failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF)https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04945460 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Study Details | A Study to Investigate the Safety and Efficacy of KER-012 in Combination With Background Therapy in Adult Participants With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) (TROPOS Study). | ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05975905?cond=Pulmonary%20Arterial%20Hypertension&term=ker-012&rank=1.

- 20.Wang X.J., Lian T.Y., Jiang X., et al. Germline BMP9 mutation causes idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(3) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01609-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long L., Ormiston M.L., Yang X., et al. Selective enhancement of endothelial BMPR-II with BMP9 reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):777–785. doi: 10.1038/nm.3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tu L., Desroches-Castan A., Mallet C., et al. Selective BMP-9 inhibition partially protects against experimental pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;124(6):846–855. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Star G.P., Giovinazzo M., Langleben D. Bone morphogenic protein-9 stimulates endothelin-1 release from human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells: a potential mechanism for elevated ET-1 levels in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Microvasc Res. 2010;80(3):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poirier O., Ciumas M., Eyries M., Montagne K., Nadaud S., Soubrier F. Inhibition of apelin expression by BMP signaling in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303(11):C1139–C1145. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00168.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauthe M., Orhon I., Rocchi C., et al. Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy. 2018;14(8):1435–1455. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1474314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durrington H.J., Upton P.D., Hoer S., et al. Identification of a lysosomal pathway regulating degradation of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(48):37641–37649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.132415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long L., Yang X., Southwood M., et al. Chloroquine prevents progression of experimental pulmonary hypertension via inhibition of autophagy and lysosomal bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor degradation. Circ Res. 2013;112(8):1159–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobolewski A., Rudarakanchana N., Upton P.D., et al. Failure of bone morphogenetic protein receptor trafficking in pulmonary arterial hypertension: potential for rescue. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(20):3180–3190. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunmore B.J., Yang X., Crosby A., et al. 4PBA restores signaling of a cysteine-substituted mutant BMPR2 receptor found in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2020;63(2):160–171. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0321OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust StratosPHere: optimal biomarkers to ascertain target engagement in therapies targeting the BMPR2 pathway in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) clinicaltrials.gov. 2023 https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05767918 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novartis Pharmaceuticals . Tolerability of LTP001 in participants with pulmonary arterial hypertension. clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. A randomized, participant- and investigator-blinded, placebo-controlled study to investigate efficacy, safety.https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05135000 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Handy D.E., Castro R., Loscalzo J. Epigenetic modifications: basic mechanisms and role in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011;123(19):2145–2156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.956839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meloche J., Pflieger A., Vaillancourt M., et al. Role for DNA damage signaling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2014;129(7):786–797. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courboulin A., Paulin R., Giguère N.J., et al. Role for miR-204 in human pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Exp Med. 2011;208(3):535–548. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meloche J., Potus F., Vaillancourt M., et al. Bromodomain-containing protein 4: the epigenetic origin of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2015;117(6):525–535. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lynparza | European medicines agency (EMA) January 9, 2015. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/lynparza

- 37.Provencher S. clinicaltrials.gov; 2023. Olaparib for pulmonary arterial hypertension: a multicenter clinical trial.https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03782818 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Provencher S., Potus F., Blais-Lecours P., et al. BET protein inhibition for pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(11):1357–1360. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202109-2182LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perros F., Montani D., Dorfmüller P., et al. Platelet-derived growth factor expression and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(1):81–88. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1037OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoeper M.M., Barst R.J., Bourge R.C., et al. Imatinib mesylate as add-on therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the randomized IMPRES study. Circulation. 2013;127(10):1128–1138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilkins M.R., Mckie M.A., Law M., et al. Positioning imatinib for pulmonary arterial hypertension: a phase I/II design comprising dose finding and single-arm efficacy. Pulm Circ. 2021;11(4) doi: 10.1177/20458940211052823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galkin A., Sitapara R., Clemons B., et al. Inhaled seralutinib exhibits potent efficacy in models of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2022;60(6) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02356-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frantz R.P., Benza R.L., Channick R.N., et al. TORREY, a Phase 2 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of inhaled seralutinib for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2021;11(4) doi: 10.1177/20458940211057071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sitbon O., Sahay S., Escribano Subías P., et al. A14. Building lego(LAND): LESSONS LEARNED from large scale clinical trials in PAH. American thoracic society International Conference Abstracts. American Thoracic Society; 2024. Interim results from the phase 1B and phase 2 TORREY open-label extension study of seralutinib in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) A1011-A1011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.GB002, Inc. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of oral Inhalation of Seralutinib for the Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05934526 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soon E., Holmes A.M., Treacy C.M., et al. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines predict survival in idiopathic and familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122(9):920–927. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.933762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toshner M., Church C., Harbaum L., et al. Mendelian randomisation and experimental medicine approaches to interleukin-6 as a drug target in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2022;59(3) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02463-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamura Y., Takeyasu R., Takata T., et al. SATISFY-JP, a phase II multicenter open-label study on Satralizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, use for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with an immune-responsive-phenotype: study protocol. Pulm Circ. 2023;13(2) doi: 10.1002/pul2.12251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanges S., Guerrier T., Duhamel A., et al. Soluble markers of B cell activation suggest a role of B cells in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.954007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zamanian R.T., Badesch D., Chung L., et al. Safety and efficacy of B-cell depletion with Rituximab for the treatment of systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(2):209–221. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202009-3481OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chinese SLE Treatment And Research Group . clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. Efficacy and mechanism of anti-CD20 antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus associated pulmonary arterial hypertension based on multi omics studies.https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05828147 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Middleton R.C., Fournier M., Xu X., Marbán E., Lewis M.I. Therapeutic benefits of intravenous cardiosphere-derived cell therapy in rats with pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One. 2017;12(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ibrahim A.G.E., Cheng K., Marbán E. Exosomes as critical agents of cardiac regeneration triggered by cell therapy. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;2(5):606–619. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewis M.I., Shapiro S., Oudiz R.J., et al. The ALPHA phase 1 study: pulmonary ArteriaL hypertension treated with CardiosPHere-Derived allogeneic stem cells. EBioMedicine. 2023;100 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson K., Rabinovitch M. Exogenous leukocyte and endogenous elastases can mediate mitogenic activity in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by release of extracellular-matrix bound basic fibroblast growth factor. J Cell Physiol. 1996;166(3):495–505. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199603)166:3<495::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sweatt A.J., Miyagawa K., Rhodes C.J., et al. Severe pulmonary arterial hypertension is characterized by increased neutrophil elastase and relative elafin deficiency. Chest. 2021;160(4):1442. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zamanian R.T. clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. Safety and tolerability of escalating doses of subcutaneous elafin (Tiprelestat) injection in healthy normal subjects.https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03522935 [Google Scholar]

- 58.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Tolerability and pharmacokinetics of intravenous ZMA001 in healthy subjects. clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. A phase 1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-ascending dose study to evaluate the safety.https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05967299 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spiekerkoetter E., Sung Y.K., Sudheendra D., et al. Randomised placebo-controlled safety and tolerability trial of FK506 (tacrolimus) for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02449-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eddahibi S., Guignabert C., Barlier-Mur A.M., et al. Cross talk between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2006;113(15):1857–1864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lazarus H.M., Denning J., Wring S., et al. A trial design to maximize knowledge of the effects of rodatristat ethyl in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (ELEVATE 2) Pulm Circ. 2022;12(2) doi: 10.1002/pul2.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sitbon O., Skride A., Feldman J., et al. Safety and efficacy of rodatristat ethyl for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (ELEVATE-2): a dose-ranging, randomised, multicentre, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;12(11):865–876. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(24)00226-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Humbert M., Kovacs G., Hoeper M.M., et al. ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(38):3618–3731. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac237. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stasch J.P., Schmidt P., Alonso-Alija C., et al. NO- and haem-independent activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase: molecular basis and cardiovascular implications of a new pharmacological principle. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136(5):773–783. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Becker-Pelster E.M., Hahn M.G., Delbeck M., et al. Inhaled mosliciguat (BAY 1237592): targeting pulmonary vasculature via activating apo-sGC. Respir Res. 2022;23(1):272. doi: 10.1186/s12931-022-02189-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mitchell J.A., Ahmetaj-Shala B., Kirkby N.S., et al. Role of prostacyclin in pulmonary hypertension. Global Cardiol Sci. Pract. 2014;2014(4):382. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2014.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torres F., Farber H., Ristic A., et al. Efficacy and safety of ralinepag, a novel oral IP agonist, in PAH patients on mono or dual background therapy: results from a phase 2 randomised, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(4) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01030-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Therapeutics United. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of ralinepag when Added to PAH Standard of Care or PAH specific background Therapy in subjects with WHO group 1 PAH. clinicaltrials.gov. 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03626688