Abstract

Background

Alarm fatigue, a phenomenon referring to clinicians being desensitized to the high volume of monitoring alarms, can impact the working environment, clinical care and patient outcomes. Explorations and understandings of alarm fatigue have yet to be a focus of attention in the Australian context.

Aim

To describe the prevalence and type of alarms activated in intensive care and cardiac units in a major metropolitan hospital in Victoria, Australia.

Study Design

This study was a descriptive observation study of patient monitoring data gathered over a 1‐month time frame during April 2019. Data from the Philips Healthcare IntelliVue® Patient Monitoring system were extracted. After classifying the alarms into types (clinical or technical) and levels of urgency (lower or higher priority), further descriptive analysis was conducted to quantify the most prevalent alarms.

Results

During the study period, a total of 271 414 activated alarms were identified. The majority were clinical alarms (89.1%) compared with technical alarms (10.9%). Clinical alarms tended to be classified as high priority (55.1%); the most common were heart rate (36.7%) and premature ventricular contraction (18.8%). Technical alarms were predominantly electrocardiogram lead disconnection (89%). The frequency of alarms per patient‐bed day was highest in the acute cardiac unit (98 alarms) compared with the intensive care unit (67 alarms).

Conclusion

Staff education and a culture of individual alarm customization might influence the number of alarms activated in the study settings. Further research is also required to examine alarm fatigue in other Australian critical care settings, and responses to alarms by clinicians, and whether these responses are calibrated to detect clinical deterioration and sentinel events.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

A bundle of interventions should be in place to increase the accuracy of alarm monitoring and to reduce non‐actionable alarms in order to reduce the possible impacts on clinicians, patients and their families/visitors.

Keywords: alarm activation, alarm fatigue, Australia, cardiac care, intensive care

What is known about the topic

The specificity of clinical monitoring alarms has become a trade‐off for their high sensitivity, resulting in a large number of false or non‐actionable alarms in critical care.

Alarm fatigue can impact the clinical environment, clinical care and patient outcomes while there is a lack of attention to this topic in Australian settings.

Predominant research in this area is in the intensive care setting, while limited research is in the cardiac care setting.

What this paper adds

Prevalence of alarm activations in one of Australia's leading quaternary referral intensive care and cardiac care centres.

Recommendations for the management of each type of clinical and technical alarms.

1. INTRODUCTION

Critical care settings are equipped with a myriad of technology used to convey information about patients' health conditions such as respiratory rate, oxygen saturations (SpO2), heart rate and blood pressure. Outside preset parameters, these devices prompt care by notifying nurses through the process of ‘alarming’. To capture clinical events, the specificity of alarms has become a trade‐off for their high sensitivity, resulting in a large number of false or non‐actionable alarms. 1

The number of alarm alerts varies across clinical settings and can range from 100 to 1000 alarms per patient per day. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 The majority of these alarms, in some cases up to 99.5%, are not considered to reflect a true and urgent deterioration in the patient's condition or require clinical actions. This volume of non‐actionable alarms has given rise to a phenomenon called alarm fatigue—the situation whereby clinicians are desensitized to alarm activation. 7 , 8 , 9 Factors known to contribute to this phenomenon include understaffing or inadequate staff training, 10 nurse perception regarding the accuracy of the alarms and the alarm limits. 11

Alarm fatigue can impact the clinical environment, clinical care and patient outcomes. The alarm glut contributes to cacophony in the health care environment. 2 , 12 The excessive noise pollution can affect nurse concentration and disrupt patient care. 13 , 14 , 15 Among patients, excessive alarms can cause anxiety, sleep deprivation and prolong recovery 1 , 16 as well as dissatisfaction with the care. 17 An early integrative review determined that desensitization to alarms among clinicians can lead to coping strategies such as muting, overriding and/or ignoring alarms, which can result in sentinel events. 18 Bach 19 reported the results of the US Food and Drug Administration database exploration that determined that 566 Americans died because of missed alarms during 2005–2008. Subsequent research in the United States found that of the 98 alarm‐related incidents during 2009–2012 that were voluntarily reported to the Joint Commission, 2 80 were fatal, 13 led to permanent function losses and five extended the patient's hospitalization.

For over a decade in the United States, the issue of alarm fatigue has been recognized as one of the 10 most critical health technology hazards based on breadth, frequency and insidiousness. 20 Alarm management became a National Patient Safety Goal in 2013, 2 and remained so in the 2024 update, 12 with the goal to reduce alarm fatigue and improve the clinical effectiveness of alarms. 2 This goal translated into systems and system modifications to enhance alarm safety by identifying critical alarms, issuing guidelines for alarm limits, standardizing response procedures, providing adequate staff training and re‐evaluating activities. 2

2. JUSTIFICATION FOR STUDY

It appears that alarm fatigue has been neglected in Australia. Only one Australian study was identified that was conducted in 2014. 21 This study involved a small survey of 48 nurses in a regional critical care unit, which found that nurses felt desensitized to and/or were unaware of how to respond to some alarms, and questioned the accuracy of the alarm and its settings. 21 In Australia, there is a lack of knowledge about the number of alarm activations and type, the magnitude of alarm fatigue and associated sentinel events. Yet there is capacity, once the phenomenon of alarm activation and fatigue in the local environment is known, to draw upon strategies already implemented elsewhere to create practice change.

3. AIM

The study aimed to describe the number and types of alarms, and the most common alarms activated to guide decisions about alarm management within the intensive care unit (ICU) and cardiac units in a major metropolitan hospital in Victoria, Australia.

4. DESIGN AND METHODS

4.1. Design

This study was a descriptive observation study of patient monitoring data gathered over a 1‐month time frame. Patient monitoring data for April 2019 were extracted from the Philips Healthcare IntelliVue® Patient Monitoring system. Patient admission data and staffing profiles during the study period were also obtained to provide a contextual understanding of the phenomenon of alarm fatigue in the study setting.

4.2. Setting

The setting for this study was a 24‐bed acute cardiac unit, a 48‐bed stepdown cardiac unit and a 45‐bed ICU located in Melbourne, Australia. In 2019, the three units collectively admitted approximately 8200 patients. The ICU is regarded as one of Australia's leading quaternary referral centres, providing state‐wide services for heart and lung transplantation, including paediatric lung transplantation, burns, adult trauma and hyperbaric medicine. The cardiac units are two of the leading cardiology and cardiothoracic services for Victoria and are a state‐wide referral centre for a broad range of conditions and procedures, including the management of ischaemic heart disease, arrhythmias, valvular heart disease, advanced heart failure, cardiac transplant and cardiothoracic surgery.

4.3. Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was received from La Trobe University’s Human Research Ethics Committee on 12th March 2019 prior to commencing the study (Project ID: 57/19).

4.4. Data collection

Excel files of data generated from the patient‐monitoring system were exported by a biomedical engineer and transferred to the research team using a secure password‐protected network. All patient beds across the units had the ability to provide continuous patient monitoring and were equipped with the Philips Healthcare IntelliVue® Patient Monitoring system. The Philips Patient Monitoring system has 22 arrhythmia alarms and 68 patient alarms measuring physiological parameters that can be customized by clinicians, and 252 technical alarms that cannot be customized. All three clinical units had the irregular heart rate alarm (which is a duplicate alarm for atrial fibrillation [AF] deactivated) to reduce the number of alarms. The major difference across the units was that the ICU had wider alarm limits than the cardiac units for respiratory rate, SpO2, blood pressure and the frequency of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) (see Table 1). In addition, the ICU had deactivated the respiratory rate alarm, most PVC alarms and ST‐segment monitoring.

TABLE 1.

Default alarm settings.

| Alarm | Threshold | Cardiac units | Intensive care unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | High | 120 | 120 |

| Low | 50 | 50 | |

| Arterial systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | High | 180 | 180 |

| Low | 100 | 90 | |

| Arterial diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | High | 100 | 90 |

| Low | 50 | 50 | |

| Arterial mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg) | High | 100 | 110 |

| Low | 70 | 60 | |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | High | 25 | 30 |

| Low | 10 | 8 | |

| Oxygen saturation (SpO2, %) | High | 100 | 100 |

| Low | 93 | 90 | |

| Oxygen desaturation limit (%) | 89 | 85 |

Note: bpm = beats per minute; mmHg = millimetres of mercury.

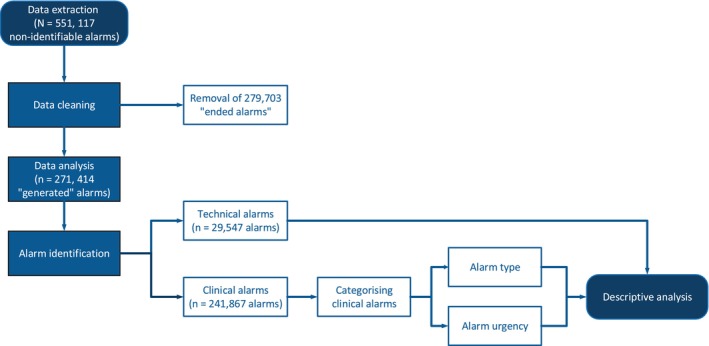

4.5. Data analysis

Data were analysed using Excel and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 25.0). Following data retrieval, ‘generated’ and ‘ended’ alarms were identified based on the recorded data. The ‘generated’ alarms indicated when an alarm was triggered, and the ‘ended’ alarms indicated either that the alarm condition was no longer present or the alarm had been turned off. The ‘ended’ alarms, which did not create an auditory stimulus, were excluded from the analysis (see Figure 1 for the study analytical procedure). Clinical alarms were then differentiated from technical alarms by clinical expert team members. Clinical alarms represented physiological alterations beyond the upper or lower programmed alarm limits. Clinical alarms were further categorized according to their urgency: (1) high priority alarms such as a potentially life‐threatening events (i.e., asystole or ventricular fibrillation) and (2) low priority alarms (i.e., respiratory alarm limit violations or non‐life‐threatening arrhythmia conditions such as ventricular bigeminy). Technical alarms indicate that the monitor cannot measure or detect alarm conditions reliably such as SpO2 probe disconnected, electrocardiogram (ECG) lead interference or leads off or telemetry battery low or empty. Subsequently, frequencies and descriptive statistics were conducted to explore characteristics of the alarms.

FIGURE 1.

Study process.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Quantification of alarm activation

In a 1‐month period, 551 117 monitoring alarms were activated; 271 414 ‘generated’ alarms and 279 703 ‘ended’ alarms (Table 2). The ‘generated’ alarms comprised clinical alarms (n = 241 867; 89.1%) and technical alarms (n = 29 547; 10.9%). The prevalence of all alarms (n = 114 597; 42.2%) and of technical alarms (n = 16 599; 14.5%) was highest in the stepdown cardiac unit (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Alarm characteristics.

| Alarm types | Acute cardiac, n (%) | Stepdown cardiac, n (%) | Intensive care unit, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total alarms | 75 704 (27.9) | 114 597 (42.2) | 81 113 (29.9) | 271 414 (100.0) | |

| Alarm type | Clinical | 68 904 (91.0) | 97 998 (85.5) | 74 965 (92.4) | 241 867 (89.1) |

| Technical | 6800 (9.0) | 16 599 (14.5) | 6148 (7.6) | 29 547 (10.9) | |

| Urgency of clinical alarms | Lower priority | 36 188 (52.5) | 41 851 (42.7) | 30 602 (40.8) | 108 641 (44.9) |

| Higher priority/potentially life threatening | 32 716 (47.5) | 56 147 (57.3) | 44 363 (59.2) | 133 226 (55.1) | |

| Clinical alarms (n = 241 867) | Heart rate | 23 747 (34.5) | 51 371 (52.4) | 13 695 (18.3) | 88 813 (36.7) |

| All PVC | 17 319 (25.1) | 24 442 (24.9) | 3828 (5.1) | 45 589 (18.8) | |

| SpO2 | 6370 (9.2) | 6005 (6.1) | 13 942 (18.6) | 26 317 (10.9) | |

| ABP | 2526 (3.6) | 7 (<0.1) | 21 014 (28.0) | 23 547 (9.8) | |

| Respiratory rate | 6689 (9.8) | 6922 (7.1) | 7656 (10.2) | 21 267 (8.7) | |

| AF | 440 (0.6) | 3961 (4.0) | 1608 (2.1) | 6009 (2.5) | |

| Pause | 1323 (1.9) | 2107 (2.2) | 434 (0.6) | 3864 (1.6) | |

| ST‐alarm | 2582 (3.7) | 85 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2667 (1.1) | |

| Technical alarms (n = 29 547) | ECG leads off | 5788 (85.1) | 14 572 (87.8) | 5928 (96.4) | 26 288 (89.0) |

| Telemetry battery related | 874 (12.9) | 1865 (11.2) | 7 (0.1) | 2746 (9.3) | |

| Other | 138 (2.1) | 162 (1.0) | 213 (3.5) | 513 (1.7) | |

Note: Percentage per clinical unit. ST‐alarm: ST‐segment alarm; Pause: no heartbeat detected for a time period greater than the pause threshold (measured in seconds).

Abbreviations: ABP, arterial blood pressure (inclusive of all invasive arterial monitoring); AF, atrial fibrillation; ECG, electrocardiogram; PVC, premature ventricular contraction; SpO2, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation.

Technical alarms were categorized as either ECG leads off, battery related and other alarms (Table 3). ECG leads off represented the vast majority of technical alarms in all units. Battery‐related alarms (n = 2746, 9.3%) included telemetry battery, battery status (low/empty), functioning status (malfunction) or the charger status of each of the batteries of the patient monitor. Other technical alarms (n = 513; 1.7%) were related to non‐invasive blood pressure cuff (not deflated or cuff pressure exceeded the overpressure safety limit), lead set unplugged, charger malfunction or alarms to notify clinicians to check the patient's identification or ECG source.

TABLE 3.

Patient admission and staffing profile during 1–30 April 2019.

| Patient admission profile | Acute cardiac | Stepdown cardiac | Intensive care unit | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n | n | |

| Total bed days during April 2019 | 773 | 1270 | 1217 | 3260 |

| Number of patient admissions during April 2019 | 120 | 249 | 219 | 588 |

| Number of patient admissions in 2019 | 1664 | 3593 | 2495 | 7752 |

| Number of all alarms per patient | 630.9 | 460.2 | 370.4 | 1461.5 |

| Number of clinical alarms per patient | 574.2 | 393.6 | 342.3 | 1310.1 |

| Number of technical alarms per patient | 56.7 | 66.7 | 28.1 | 151.5 |

| Number of alarms per patient‐bed day | 97.9 | 90.2 | 66.6 | 254.7 |

| Number of clinical alarms per patient‐bed day | 89.1 | 77.2 | 61.6 | 227.9 |

| Number of technical alarms per patient‐bed day | 8.8 | 13.1 | 5.1 | 27 |

| Staffing profile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Staff number (head count) | 66 | 77 | 376 |

| Actual FTE | 50.5 (100%) | 62.2 (100%) | 301.6 (100%) |

| Non‐direct nurse a FTE | 4.6 (9.1%) | 1.9 (3.1%) | 21.7 (7.2%) |

| Associate Nurse Managers FTE | 3.6 (7.1%) | 6.0 (9.6%) | 22.9 (7.6%) |

| Senior nurse FTE (>10 years of experience) | 15.6 (30.9%) | 7.7 (12.4%) | 95.6 (31.7%) |

| Moderately experienced staff FTE (5–10 years of experience) | 15.2 (30.1%) | 13.0 (20.9%) | 111.5 (37.0%) |

| Junior nurse FTE (1–≤5 years of experience) | 6.4 (12.7%) | 25.8 (41.5%) | 49.8 (16.5%) |

| Graduate nurses FTE (≤1 year of experience) | 5.1 (10.1%) | 7.8 (12.5%) | 0.0 (0.0%) |

| Critical Care Registered Nurse | 20.6 (40.9%) | 6.48 (10.4%) | 239 (79.4%) |

| Nurse: patient ratio | 1:2–1:3 | 1:4 | 1:1–1:2 |

Abbreviation: FTE, full‐time equivalent.

Including nurse unit managers, nurse educators and equipment nurses.

The five most frequently occurring clinical alarms in all three wards were heart rate, all types of PVC, SpO2, arterial blood pressure (ABP) and respiratory rate alarms (Table 2).

5.2. Contextual information

Among the three units, the acute cardiac unit recorded the lowest number of bed days and number of patients during the study period while recording the highest number of total alarms, clinical alarms, alarms per patient and alarms per patient‐bed day (Table 3). On the other hand, the numbers of technical alarms per patient and per patient‐bed day were lowest in the ICU. The staffing profiles of the three units, based on the number of full‐time equivalent (FTE) staff employed, are described and highlight differences in patient ratios, which favour the ICU setting, as expected, with the ICU having higher patient ratios, fewer junior staff and a higher proportion of critical care registered nurses (Table 3).

6. DISCUSSION

This study describes the number and type of alarms activated in the units in a major metropolitan hospital in Victoria. To our knowledge, this research is the first to quantify alarm activation of patient monitoring systems in an ICU and cardiac Australian context.

6.1. Alarm frequency

The frequency of alarm activations and the number of alarms per patient‐bed day were lower in the ICU as compared to the cardiac units, a finding contrasting with that in other contexts. 22 , 23 The number of alarms activated in the ICU was also lower than in many other adult ICUs. 22 , 24 This was an unexpected finding given the high acuity of patients admitted to the ICU in the study institution, which is one of the largest and most complex case mixes in Australia.

Our findings support the literature that staff experience and training, 15 , 25 workplace alarm culture, 16 , 19 , 26 as well as policies/procedures on setting alarm limits 11 , 19 , 27 can influence the management of clinical alarms in practice. More specifically, as compared to the cardiac units, the study ICU had (1) higher nurse‐to‐patient ratios (see Table 3), (2) greater proportion of critical care registered nurses who might have been equipped with additional training regarding alarm customization (see Table 3), (3) wider default settings (for respiratory rate, SpO2, invasive blood pressure alarms, see Table 1), (4) deactivation of some clinical alarms (mentioned above) and (5) differences in policies for recognizing and responding to clinical deterioration. In particular, the default clinical alarm limits in the cardiac units are linked to the hospital's Clinical Review Criteria, which are intended to trigger a mandatory medical review for abnormal vital signs to escalate care when clinical deterioration occurs. Note that this process was mandatory in the cardiac units but not in the ICU. This can be considered a hurdle to nurses in the cardiac units who are likely reluctant to alter a patient's alarm limits outside of the hospital's Clinical Review Criteria without assessment by a medical officer.

There have been limited and older cardiac‐focused studies exploring the experience of alarm activation in a cardiac setting. 28 , 29 The number of alarms activated in the two cardiac units in the current study was higher than that previously reported in other cardiac settings. 28 , 29 This finding reflects the high acuity of patients admitted to the study institution, which is a tertiary referral centre that provides specialized services for patients with advanced heart failure, mechanical assist devices and heart transplantation for Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. This study included additional data on physiological alarms such as heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and SpO2, and technical alarms, while other studies in cardiac settings focused exclusively on arrhythmia alarms. 28 , 29 The limited evidence from other cardiac settings also restricts some comparisons we would like to make on specific clinical alarms.

6.2. Clinical alarms and implications

We found findings similar to previous studies in terms of most frequently activated alarms: heart rate 22 , 26 followed by PVC. 6 High heart rate alarms reflect the high acuity of patients and high rates of postoperative AF encountered in cardiac surgical patients. Other studies found that a high proportion of heart rate alarms were false/non‐actionable and caused by artefact on the ECG (i.e., patient movement), or double counting of P‐waves and T‐waves 26 which might also be the case in our study. Meanwhile, PVC alarms were one of the most common rhythms detected in the clinical setting 30 , 31 and found in most individuals undergoing cardiac monitoring. 32 In our study, PVC alarms were far more common in the cardiac units than in the ICU. This may be explained by a greater prevalence of structural heart disease in the cardiac units predisposing to PVCs and that the ICU deactivated most of the PVC alarms and widened parameters for the frequency of PVCs. Considering the high volume of PVC alarms that are not immediately life threatening, deactivation of some PVC alarms has been recommended. 33

Consistent with other studies, the two most common alarm types in our ICU were invasive arterial blood pressure 6 , 22 , 34 (ABP: including breaches in systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressure, and ABP disconnect) and SpO2. 22 Despite the frequency of ABP monitoring alarms in the ICU, there is a lack of recommendations in the literature that specifically describe strategies to reduce the number of ABP monitoring alarms, other than silencing alarms for interventions such as blood sampling. Meanwhile, a proportion of SpO2 alarms is likely false/non‐actionable because of poor perfusion, motion artefact or default settings that are not customized to the patient. 11 , 35 Using an alternate monitoring site such as the earlobe or forehead could be explored to assess whether it offers reduced impact of poor perfusion or motion artefact. Furthermore, decreasing the threshold of the low SpO2 alarm limit and adding delays before an alarm is triggered has been shown to increase the clinical validity of these alarms. 35 , 36 A short alarm delay for SpO2 monitoring has been shown to allow brief episodes of desaturations, caused by motion artefact, to be autocorrected without adverse outcomes. 37 Indeed, in this study, although conducted in 2011, Welch found that reducing the SpO2 threshold from 90% to 88% resulted in a 45% reduction in total alarms and a 70% reduction when increasing the alarm delay from 5 to 15 s without compromising patient safety. 37 Perhaps this could be considered a default setting for SpO2 alarms to reduce alarm activation.

The number of respiratory alarms in our study was lower than previously reported from those conducted over a decade ago. 38 , 39 This could be because the respiratory rate alarms, based on ECG monitoring, had been turned off in the default settings in this study's ICU setting. Furthermore, about 70% of patients admitted to the study ICU are mechanically ventilated or require non‐invasive ventilation which incorporate respiratory rate and apnoea alarm's as well as other forms of respiratory monitoring such as end‐tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) monitoring that are not captured by the Philips Patient Monitoring system. According to a seminal study by Drew et al., 38 there was anecdotal evidence of flat line respiratory waveforms in patients on mechanical ventilation or breathing normally, which suggests a problem with the detection of respiration using thoracic impedance derived from ECG monitoring. This underscores the importance of correct electrode placement for respiratory measurement.

One surprising finding was the low frequency of AF alarms compared with other studies. 38 This alarm type is one of the most common arrhythmias encountered in practice. 9 , 40 , 41 The presence of AF can generate repetitive AF alarms if not deactivated in patients with persistent AF. In practice, it is important to recognize when a patient develops AF to assess the response of the arrhythmia and initiate prompt treatment. However, it is unnecessary to have this alarm for patients with chronic AF or when treatment has already been initiated and rate control is adequate. 33 The low frequency of AF alarms may suggest that nurses at the study institution were selectively deactivating AF alarms.

In our study, ST‐segment monitoring alarms were only activated in the acute cardiac unit, similar to the study by Drew et al. 38 which included five adult ICUs where only the cardiac ICU utilized ST‐segment monitoring. This practice is consistent with practice guidelines that encourage ST‐segment monitoring for patients with acute coronary syndrome, after percutaneous coronary intervention, and following cardiac surgery to identify episodes of myocardial ischaemia. 33 Despite the potential advantages of this technology, ST‐segment monitoring has been found to elicit a large proportion of false/non‐actionable alarms. For example, Drew et al. 38 found that the vast majority of these alarms (91%) were false alarms caused by changes in body position. These authors 38 recommended implementing delays in ST‐segment changes to eliminate brief spikes in the ST‐segment from patient movement to reduce the number of false alarms.

6.3. Technical alarms

The finding of 10.9% of technical alarms was consistent with two other studies in the ICU setting from Germany 39 and the United States. 38 The vast majority of technical alarms in all three units were caused by ECG leads off, which is consistent with the study by Drew et al. 38 Another common source of technical alarms was low or empty telemetry battery alarms.

The higher number of technical alarms was greatest in the cardiac stepdown unit. This might be attributable to the greater proportion of ambulatory patients on telemetry monitoring as opposed to hardwire monitoring in the stepdown cardiac unit that might result in accidental lead disconnection and low battery alarms. Meanwhile, in the ICU setting, sweating is commonly seen in critically unwell patients and could cause poor electrode‐to‐skin contact.

Dried ECG electrodes, motion artefact and poor skin‐electrode contact can trigger false and technical alarms. Evidence published approximately a decade prior highlights some strategies to address these issues. 42 , 43 For example, proper skin preparation and daily electrode changes improved signal acquisition and reduced artefact and have been shown to reduce the number of monitoring alarms by 46% in a cardiology unit. 42 In another study, the use of disposable lead wires was associated with significantly fewer technical ECG alarms than reusable lead wires. 43 In addition, the manufacturer recommended daily battery changes for telemetry units to reduce the number of battery alarms.

7. LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations. First, other alarm‐generating medical devices utilized in the critical care environment, such as infusion pumps, ventilators, non‐invasive ventilation, tube feeding pumps, dialysis machines, bed alarms and compression devices, were not quantified because data retrieval from this technology was not yet possible at the time of data collection. This study may thus underestimate the true number of alarms in the study setting. Second, alarm burden was reported as the average number of alarms per patient per day to be consistent with most studies investigating alarm fatigue. This finding is likely skewed because often, in practice, a small number of patients create most of the alarm burden. 44 Third, because of the retrospective study design we were unable to determine what proportion of alarms was true/false and/or actionable/non‐actionable as well as examine staff's actions towards the alarms. This was because data extracted from the Philips Patient Monitors only provided a frequency count of activated alarms. Fourth, this study did not survey nurses to quantify the experience of alarm fatigue among staff and calibrate it to the quantity or type of alarms reported. Fifth, we assumed that patient acuity may have an impact on the number of alarms; however, data on illness severity were not collected nor has this been reported in other published studies on alarm fatigue to make any comparison between published studies. Finally, this study was undertaken in one major metropolitan hospital that included highly specialized ICU and cardiac units, which may limit the generalizability to other clinical settings. To address the above methodological limitations, we recommend that future research (1) use a prospective design to identify true/false clinical alarms, (2) incorporate a larger sample including multiple sites and regions, (3) collect data on patient acuity and (4) appraise the impact of alarm activation on staff, patients and their visitors.

8. IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Based on our findings, several practice guidelines 2 , 12 , 33 , 45 and review papers, we provide some recommendations to practice. We recommend a bundle of interventions including, first, establishing a multidisciplinary team to review widening default alarm limits, adding alarm delays, and deactivating non‐actionable alarms such as some PVC alarms, and duplicate alarms such as AF and irregular heart rate. Second, as it was evident in our study that staff experience and training and organizational policies can positively influence alarm management, we recommend providing staff with education/training and support on alarm customization and developing protocols to ensure alarm limits are checked at the commencement of a shift that encourage nurses to customize alarm limits within established parameters. Third, reinforcing correct electrode placement, optimal skin preparation, daily replacement of ECG electrodes and best lead selection are essential to ensure proper signal acquisition, increase ECG amplitude and reduce artefact. Fourth, we recommend evaluating equipment such as lead wires and SpO2 probes, and daily replacement of telemetry batteries to reduce nuisance alarms and daily medical reviews to discontinue monitoring. Additional strategies could also include placing SpO2 sensors on warm and well‐perfused extremities and pausing alarms during patient interventions if safety allows.

9. CONCLUSION

This study represents an important step in understanding alarm fatigue by first examining the number and type of alarms in a 1‐month period in an Australian metropolitan critical care setting. Relative to other studies, the number of alarms in our study was lower in the ICU setting as than that in the cardiac units, potentially because of staff experience and training, ward policy on multidisciplinary team review, alarm settings and individual alarm customization. We also attempted to provide recommendations for practice focussing on the use of a bundle of interventions from organizational strategies to some individual alarms. We highlighted literature gaps and warranted future quality research examining alarm fatigue in other Australian critical care settings, specifically to identify true/false clinical alarms, contributing factors to alarm fatigue, and its impact on staff and patient safety.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by The Alfred Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

We received funding from The Alfred Health, whose data were used in this study. B.M. and A.C. were previous employees at The Alfred Health. The data ownership and employment did not affect the data analysis and interpretation of the findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are thankful to Alfred Health for providing financial and operational support that enabled this study; Mr Robert Barnett, Chief Biomedical Engineer, Alfred Health, for providing biomedical engineering support for data extraction; and Associate Professor Wendy Pollock for her valuable feedback and insights on an earlier version of this article. Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Nguyen V, MacDonald B, Cignarella A, Miller C. A descriptive investigation of alarm activation in a critical care setting. Nurs Crit Care. 2025;30(2):e13302. doi: 10.1111/nicc.13302

Van Nguyen and Brendan MacDonald are joint first authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from The Alfred Health. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the author(s) with the permission of The Alfred Health.

REFERENCES

- 1. Srinivasa E, Mankoo J, Kerr C. An evidence‐based approach to reducing cardiac telemetry alarm fatigue. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2017;14(4):265‐273. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Joint Commission . Sentinel event alert . 2013. [PubMed]

- 3. Gorisek R, Mayer C, Hicks WB, Barnes J. An evidence‐based initiative to reduce alarm fatigue in a burn intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2021;41(4):29‐37. doi: 10.4037/ccn2021166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jämsä JO, Uutela KH, Tapper AM, Lehtonen L. Clinical alarms and alarm fatigue in a university hospital emergency department‐a retrospective data analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021;65(7):979‐985. doi: 10.1111/aas.13824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Unal A, Arsava EM, Caglar G, Topcuoglu MA. Alarms in a neurocritical care unit: a prospective study. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022;36(4):995‐1001. doi: 10.1007/s10877-021-00724-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yeh J, Wilson R, Young L, et al. Team‐based intervention to reduce the impact of nonactionable alarms in an adult intensive care unit. J Nurs Care Qual. 2020;35(2):115‐122. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sowan A. Effective dealing with alarm fatigue in the intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2024;80:103559. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2023.103559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fleischman W, Ciliberto B, Rozanski N, Parwani V, Bernstein SL. Emergency department monitor alarms rarely change clinical management: an observational study. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(6):1072‐1076. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewandowska K, Weisbrot M, Cieloszyk A, Mędrzycka‐Dąbrowska W, Krupa S, Ozga D. Impact of alarm fatigue on the work of nurses in an intensive care environment‐a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):1‐14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jeong YJ, Kim H. Critical care nurses' perceptions and practices towards clinical alarms. Nurs Crit Care. 2023;28(1):101‐108. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patel NZ, Patel DV, Phatak AG, Patel VG, Nimbalkar SM. Reducing false alarms and alarm fatigue from pulse oximeters in a neonatal care unit: a quality improvement study. J Neonatol. 2022;36(2):135‐142. doi: 10.1177/09732179221100531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Joint Commission . Hospital: 2024 national patient safety goals . https://www.jointcommission.org/‐/media/tjc/documents/standards/national‐patient‐safety‐goals/2024/npsg_chapter_hap_jan2024.pdf 2024.

- 13. Ruppel H, Funk M, Clark JT, et al. Attitudes and practices related to clinical alarms: a follow‐up survey. Am J Crit Care. 2018;27(2):114‐123. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2018185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petersen EM, Costanzo CL. Assessment of clinical alarms influencing nurses' perceptions of alarm fatigue. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36(1):36‐44. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alsuyayfi S, Alanazi A. Impact of clinical alarms on patient safety from nurses' perspective. Inform Med Unlocked. 2022;32:101047. doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2022.101047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winters BD, Slota JM, Bilimoria KY. Safety culture as a patient safety practice for alarm fatigue. JAMA. 2021;326(12):1207‐1208. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.8316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hweidi IM. Jordanian patients' perception of stressors in critical care units: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(2):227‐235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cvach M. Monitor alarm fatigue: an integrative review. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2012;46(6):268‐277. doi: 10.2345/0899-8205-46.4.268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bach TA, Berglund L‐M, Turk E. Managing alarm systems for quality and safety in the hospital setting. BMJ Open Quality. 2018;7(3):e000202. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Emergency Care Research Institute . Top 10 Health Technology Hazards for 2016. Emergency Care Research Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Christensen M, Dodds A, Sauer J, Watts N. Alarm setting for the critically ill patient: a descriptive pilot survey of nurses' perceptions of current practice in an Australian regional critical care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2014;30(4):204‐210. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Allan SH, Doyle PA, Sapirstein A, Cvach M. Data‐driven implementation of alarm reduction interventions in a cardiovascular surgical ICU. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(2):62‐70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bi J, Yin X, Li H, et al. Effects of monitor alarm management training on nurses' alarm fatigue: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(21–22):4203‐4216. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poncette AS, Wunderlich MM, Spies C, et al. Patient monitoring alarms in an intensive care unit: observational study with do‐it‐yourself instructions. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(5):e26494. doi: 10.2196/26494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nyarko BA, Nie H, Yin Z, Chai X, Yue L. The effect of educational interventions in managing nurses' alarm fatigue: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(13–14):2985‐2997. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruppel H, Funk M, Kennedy HP, Bonafide CP, Wung SF, Whittemore R. Challenges of customizing electrocardiography alarms in intensive care units: a mixed methods study. Heart Lung. 2018;47(5):502‐508. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu M, Sun Z, Ye W, et al. Optimization strategies to reduce alarm fatigue in patient monitors. Paper presented at: 2020 Computing in Cardiology; September 13–16 2020.

- 28. Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24(4):387‐388. doi: 10.4037/NCI.0b013e3182a903f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cvach MM, Frank JR, Doyle KP, Stevens KZ. Use of pagers with an alarm escalation system to reduce cardiac monitor alarm signals. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014;29(1):9‐18. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182a61887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Suba S, Hoffmann TJ, Fleischmann KE, et al. Evaluation of premature ventricular complexes during in‐hospital ECG monitoring as a predictor of ventricular tachycardia in an intensive care unit cohort. Res Nurs Health. 2023;46(4):425‐435. doi: 10.1002/nur.22314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suba S, Hoffmann TJ, Fleischmann KE, et al. Premature ventricular complexes during continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in the intensive care unit: occurrence rates and associated patient characteristics. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(13–14):3469‐3481. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marcus GM. Evaluation and management of premature ventricular complexes. Circulation. 2020;141(17):1404‐1418. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al. Update to practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(19):e273‐e344. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sowan AK, Gomez TM, Tarriela AF, Reed CC, Paper BM. Changes in default alarm settings and standard in‐service are insufficient to improve alarm fatigue in an intensive care unit: a pilot project. JMIR Hum Factors. 2016;3(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.5098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lansdowne K, Strauss DG, Scully CG. Retrospective analysis of pulse oximeter alarm settings in an intensive care unit patient population. BMC Nurs. 2016;15(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0149-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Paine CW, Goel VV, Ely E, et al. Systematic review of physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and pragmatic interventions to reduce alarm frequency. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):136‐144. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Welch J. An evidence‐based approach to reduce nuisance alarms and alarm fatigue. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2011;45:46‐52. doi: 10.2345/0899-8205-45.s1.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Drew BJ, Harris P, Zègre‐Hemsey JK, et al. Insights into the problem of alarm fatigue with physiologic monitor devices: a comprehensive observational study of consecutive intensive care unit patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Siebig S, Kuhls S, Imhoff M, Gather U, Schölmerich J, Wrede CE. Intensive care unit alarms—how many do we need? Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):451‐456. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brieger D, Amerena J, Attia J, et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation 2018. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(10):1209‐1266. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2018.06.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stiglich YF, Dik PHB, Segura MS, Mariani GL. The alarm fatigue challenge in the neonatal intensive care unit: a “before” and “after” study. Am J Perinatol. 2023;41:e2348‐e2355. doi: 10.1055/a-2113-8364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cvach MM, Biggs M, Rothwell KJ, Charles‐Hudson C. Daily electrode change and effect on cardiac monitor alarms: an evidence‐based practice approach. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013;28(3):265‐271. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31827993bc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Albert NM, Murray T, Bena JF, et al. Differences in alarm events between disposable and reusable electrocardiography lead wires. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(1):67‐73; quiz 74. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gross B, Dahl D, Nielsen L. Physiologic monitoring alarm load on medical/surgical floors of a community hospital. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2011;45:29‐36. doi: 10.2345/0899-8205-45.s1.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. American Association of Critical Care Nurses . Managing alarms in acute care across the life span: electrocardiography and pulse oximetry. Crit Care Nurse. 2018;38(2):e16‐e20. doi: 10.4037/ccn2018468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from The Alfred Health. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the author(s) with the permission of The Alfred Health.