Summary

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) perturbs specific brain regions and, combined with electroencephalography (EEG), enables the assessment of activity within their connected networks. We present a resting-state TMS-EEG protocol, combined with a controlled experimental design, to assess changes in brain network activity during offline processing, following a behavioral task. We describe steps for experimental design planning, setup preparation, data collection, and analysis. This approach minimizes biases inherent to TMS-EEG, ensuring an accurate assessment of changes within the network.

For complete details of the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Bracco et al.1

Subject areas: Neuroscience, Cognitive Neuroscience, Biotechnology and bioengineering

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A TMS-EEG protocol to measure brain network activity during offline processing

-

•

Experimental and analytical steps to control confounding factors in TMS-EEG

-

•

Analysis pipeline to assess network activity changes after a behavioral task

Publisher’s note: Undertaking any experimental protocol requires adherence to local institutional guidelines for laboratory safety and ethics.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) perturbs specific brain regions and, combined with electroencephalography (EEG), enables the assessment of activity within their connected networks. We present a resting-state TMS-EEG protocol, combined with a controlled experimental design, to assess changes in brain network activity during offline processing, following a behavioral task. We describe steps for experimental design planning, setup preparation, data collection, and analysis. This approach minimizes biases inherent to TMS-EEG, ensuring an accurate assessment of changes within the network.

Before you begin

Institutional permissions

This experimental protocol was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local research ethics committee (National Health Service; West Coast of Scotland).

Introduction

Brain functions rely on the formation of neural ensembles. These consist of neurons distributed through the brain and coupled together to operate as functional units.2,3 When neural networks are active to support a specific brain function, they may become less sensitive to external perturbation due to their consistent pattern of activity. In a recent study, we demonstrated that following the interaction between two different memories (motor skill vs. declarative), the network involved in the offline interaction developed resistance to external perturbation.1 To perturb the network activity, we used single pulses of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) and concurrently measured its effect with electroencephalography (EEG). TMS was delivered during offline memory processing (resting state) over areas within the network implicated in the process.

EEG alone provides critical information about the current state of the brain and its spontaneous oscillatory activity. However, EEG simultaneously captures activity from multiple cortical areas, making it difficult to isolate the contribution of individual brain regions or specific networks. This is particularly challenging when studying offline processing during resting periods, such as in our study. In the absence of a task designed to activate the network of interest, subtle changes in the activity of the network may be masked by general activity unrelated to the brain process under assessment.

To overcome these limitations, we combined EEG with TMS. TMS transiently perturbs the spontaneous activity of the stimulated region and its connections, allowing us to interact with the activity within the network and assess its effects through EEG.4,5,6,7 Because the perturbed network is known by design, TMS coupled with EEG can highlight changes in the oscillatory activity within the network with a good signal-to-noise ratio. This provides crucial insights into the involvement of the network in the process of interest, as well as the current state of its activity and dynamics, during any stage of the process under investigation. In our study, we were interested in evaluating how two different neural circuits respond to TMS following memory interaction. We found a decrease in perturbation induced by TMS from baseline to post-memory formation. This occurred during offline memory processing within a specific circuit, i.e., the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).1 This result suggests that the offline memory processing led to the formation of a functional network overlapping with DLPFC that became resistant to perturbation. This was reflected in the reduced ability of TMS pulses to perturb the ongoing oscillatory activity, as the oscillations resisted their perturbing effects (Figure 1). Here, we provide general instructions for using our TMS-EEG protocol to study the effects of other offline brain processes on spontaneous oscillatory activity within specific networks of interest.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the hypothesized changes in brain network resistance to external perturbation

Network resistance to external perturbation arises when neural ensembles develop stable and consistent activity patterns due to offline processing (Neural ensembles activity). This stable pattern of activity makes the network less susceptible to disruption by external stimuli. For example, before a behavioral task, when the circuit (blue circles) is not yet engaged in specific processing, TMS perturbs the targeted network, and triggers a response of a certain amplitude (Amplitude of the perturbed oscillations before a task (Baseline)). In contrast, after the task, the network is engaged in the offline processing induced by the task, and it is less sensitive to the TMS pulse. As a consequence, the ongoing oscillation resists the perturbing effects of the pulse (Amplitude of the perturbed oscillations following a task (Offline processing)). This resistance may be detected as a decrease in the oscillatory activity perturbed by TMS during offline processing compared to baseline (Change(Offline-Baseline)). Red and blue arrows represent the amplitude of the perturbed oscillation induced by TMS, before and during offline processing, and its difference from baseline to offline processing (Change(Offline-Baseline)).

Planning the experimental design

CRITICAL: To assess changes in brain network resistance to perturbation during offline processing, certain decisions regarding the study design must be made. In this section, we outline some of the key considerations.

-

1.

Choose a behavioral task that engages the offline process of interest.

Note: In the original study, we wanted to determine how the interaction between memories of different types (motor skill vs declarative) shapes brain network dynamics.1 To achieve this, we selected two learning tasks that have previously been used to study the interaction of newly formed memories.8,9 Specifically, participants learned a motor sequence (motor skill memory; serial reaction time task) and, immediately after, a word list (declarative memory). Previous work has shown that, when learned in quick succession, the declarative memory interacts with the motor skill memory and leads to impaired motor skill retention.8,9,10,11 We perturbed participants' cortical oscillatory activity with single pulses of TMS and recorded their immediate effect using simultaneous EEG, both at baseline (before learning) and offline, during offline memory processing (after memory formation). Future studies may use resting-state TMS-EEG protocols to probe brain activity changes within a particular network due to other offline processes, including other types of memories, but also learning, attention, mental load, or physical effort.

-

2.

Select task-relevant brain areas.

Note: We chose the right DLPFC and left primary motor cortex (M1) because of their involvement in offline processing and the interaction between memories of different types.10,11

-

3.

Consider possible confounds and suitable controls.

Note: Changes in brain activity can be unrelated to the offline process under investigation, and for example, be due to fatigue as the experiment progresses. To account for possible confounds, you may want to choose a control condition with similar characteristics to the main condition but expected not to induce the hypothesized effects. For example, in the original study, we included a control group. Specifically, one group of participants learned a motor sequence followed by a word list (main tasks; main group; Figure 2A). In contrast, a second group performed a motor task without any serial structure before learning the word list (control tasks; control group; Figure 2A). This motor task performed by the control group was identical to the motor sequence task in every aspect except for the absence of a serial structure to be learned. Consequently, no memory formation occurred, and thus no interaction between memories could take place. While in our study we assessed group differences, a within-subject design with a control condition could also be implemented, depending on the process under investigation.

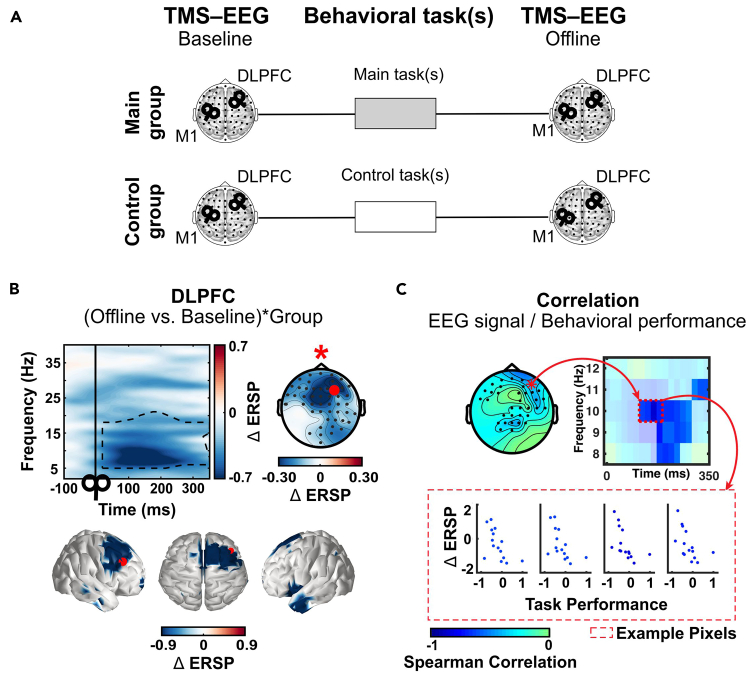

Figure 2.

Experimental design and expected outcomes

(A) Single TMS pulses are applied to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) or the primary motor cortex (M1) while the effects of TMS perturbation are recorded using EEG (black coils overlying a brain). TMS-EEG is recorded in the two groups before (baseline) and after (offline) behavioral performance. Our groups corresponded to a Main group of participants learning a motor sequence followed by a word list (main tasks), and a control group of participants performing a similar motor task, but with no sequence, followed by a word list (control task). By comparing these groups, we can identify how brain network resistance to perturbation is changed by offline processing (main versus control group). In the original paper, we chose a between-group design, but a within-group design can also be chosen depending on the offline process of interest.

(B) TMS-EEG results when DLPFC is stimulated. Results represent the interaction between the two groups, expressed in terms of changes in the response of DLPFC to single TMS pulses before (baseline) and after (offline) task performance. The figure shows that the change in DLPFC response differs significantly between the conditions ((offline versus baseline)∗group(main versus control). The identified cluster (dashed box; time-frequency plot) corresponds to frequencies within the alpha/beta range (6–23 Hz). In the time-frequency plots, the black vertical line and black coil indicate TMS-pulse onset (i.e., 0 ms). The black dashed boxes highlight the significant clusters (frequency range and duration). In the topographical plots, the red dot identifies the position of the TMS coil, while the small black dots show the channels included in the significant cluster. Both the time-frequency and topographical plots show the same clusters visualized in different ways. The three-dimensional clusters (time, frequency, and channel) are collapsed across channels—to give the time-frequency plot—or across both time and frequency—to give the topographical plot. Finally, in the spatial plots (3D average brain), a red dot indicates the position of the TMS coil (in anatomical space).

(C) Correlation results between alpha oscillatory activity perturbed by TMS and behavioral performance (e.g., in our case the result of memory interference). Results show a significant negative correlation between the tested behavioral performance and the change in the DLPFC response to a TMS pulse within the alpha range (8–12 Hz). The topographical plot shows the spatial distribution of the significant relationship between DLPFC response change and behavioral performance. These are identified using a cluster analysis (Spearman correlation) and the (three-dimensional) cluster is collapsed across time and alpha frequency band to create the topographical plot. Channels are then selected from the identified cluster to show the cluster in the time-frequency plot. Four representative pixels (red dashed rectangle) have been used to illustrate the relationship between power change (ΔERSP) and task performance. The color of the scatter dots and the corresponding time-frequency pixel indicates the Spearman correlation coefficient in the pixel. Figure reprinted and adapted with permission from Bracco et al., 2023.1 Only significant results are shown. For more details on the results, please refer to the original paper.

-

4.

Determine the most appropriate time for probing with TMS the brain networks of interest.

Note: Critical events related to offline memory interaction start immediately after memory formation.8,10,11,12 For this reason, we applied single pulses of TMS before and immediately after the last memory task, ensuring that the TMS protocol did not exceed 21 min to capture the network changes of interest.

-

5.

Choose an appropriate TMS intensity.

Note: Selecting the appropriate TMS intensity requires balancing the need for measurable and robust EEG activity (locally and distally) with the goal of minimizing TMS-evoked scalp muscle activity and multisensory responses, such as those due to coil vibration, coil click, and excitation of nerves in the skin. This balance is especially important for targets like the DLPFC, which are farther from the midline and more prone to muscle artifacts.13 In our study, we used 80% of the resting Motor Threshold (rMT) to minimize muscle contraction when targeting the DLPFC. This intensity has the additional advantage of reducing the likelihood of eliciting Motor Evoked Potentials (MEPs) when stimulating M1, which can lead to peripheral-evoked somatosensory potentials in EEG (re-afference) from approximately 40 ms after the TMS pulse.14,15 Although relatively low, this intensity elicits measurable EEG responses,16,17,18 and modulates activity in distally connected brain regions.19,20 Higher intensities may be considered depending on the target region, especially for areas closer to the midline.

Behavioral task preparation

Note: This section does not aim to provide an exhaustive task description as it falls beyond the scope of the present article. For more information on these behavioral tasks, please refer to the original paper.1 Instead, you are encouraged to select or design task(s) that best align with your hypothesis and the brain process of your interest. In the original study, we created a motor skill task, a motor performance task, and a word-list learning task using MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) along with its open-source toolbox Psychtoolbox (PTB-3) and Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, US). However, other software can also be used.

Experimental setting preparation

Timing: approximately 1 month

-

6.Prepare the experimental room:

-

a.Choose an appropriate room with low environmental electromagnetic noise to ensure high-quality EEG data recording.Note: In the original study, we used a Faraday cage.

-

b.Set up as many computers as you need for running your experiment.Note: In the original study we had (1) an experimental computer running the behavioral tasks and triggering the TMS stimulator(s), equipped with all the required software, in our case, MATLAB and ePrime (Psychology Software Tools Inc.); (2) a computer running the EEG recording software, in our case, BrainVision Recorder (Brain Products); and (3) a computer running a frameless stereotactic neuronavigation software, in our case, Brainsight (Rogue Research Inc., Montréal, QC, Canada).

-

c.Install a chin rest to maintain a fixed distance between the monitor and the participant’s eyes and reduce head movement during brain stimulation.Note: In our case, the distance from the screen was set to 800 mm.

-

d.Set up the TMS machine(s):Note: In our experiment, we used two identical TMS machines because we were interested in assessing resistance to external perturbation of two brain areas and their connected networks: the right DLPFC and left M1.

-

i.Choose the stimulator to use; for example, in our study, we used two biphasic TMS machines (Magstim Rapid2, Magstim Company) each connected to a figure-of-eight coil (Double 70 mm Alpha Coil).Note: Choosing the stimulation pulse configuration depends on balancing focality and effectiveness. While monophasic currents produce more focal corticospinal activation,21 biphasic pulses elicit activation at a lower motor threshold, requiring less TMS intensity.22,23 This lower intensity helps minimize muscle activation13 and indirect multisensory responses.24,25,26 As in our study we did not aim to target a highly specific brain region but rather to reduce stimulation intensity, we opted for biphasic stimulation and prioritized effectiveness over precise localization.27 We encourage choosing the stimulation pulse configuration depending on the specific goals of the experiment.

-

ii.Connect all used TMS machines to the experimental computer for automatic triggering (in our case, via parallel port).

-

i.

-

e.Connect TMS-compatible foam earphones to the experimental computer; these will be used to play masking noise during the stimulation and suppress potential TMS-related auditory responses.

-

f.Program a script to automatically control the delivery of TMS pulses:

-

i.Using ePrime or a similar software, set the color, font, size, and position of the text (for example, black, 17, Arial, center), create the first screen to inform the participants that the stimulation is about to start, and set the spacebar as a key to be pressed to initiate the stimulation.

-

ii.Create a fixation cross to be continuously displayed during the stimulation.

-

iii.Program the delivery of single TMS pulses with a random inter-stimulus interval (ISI).Note: In our case, we used a jitter between 4-6 s across the two brain targets. When planning the TMS protocol, the risk of inducing plastic changes and hysteresis effects is a crucial aspect to consider.28 An ISI of 4–6 s (or longer), both within and across the two stimulated areas, minimizes this risk. Additionally, to further mitigate the risk of inducing plastic changes, it is important to randomize the order of pulses across the two areas. This random distribution of pulses further reduces the likelihood of systematically inducing plasticity through repeated activation of the same cortical circuits. Finally, while this ISI minimizes the risk of inducing plastic changes, it also allowed us to collect sufficient trials within the 21-minute time frame. To ensure participant comfort, we divided the stimulation into short blocks of 84 pulses (42 per target region). By running the block three times per measurement time (baseline vs. offline), we delivered a total of 252 pulses before and after the behavioral tasks.

-

iv.Create the last screen to inform the participant that the stimulation block has ended.

-

i.

-

g.Prepare the masking noise to block TMS click-related auditory responses:

-

i.Using MATLAB or similar software, generate a signal composed of white noise.

-

ii.Export the signal as a .wav file.

-

iii.Install the appropriate software on the experimental computer to play the masking noise through earphones.

-

iv.Calibrate the volume of the auditory masking measuring the air pressure produced by the combination of the computer and the selected earphones at various volume levels to ensure that the noise does not surpass 90 dB during the recordings.Note: The air pressure can be gauged using a decibel meter along with a plastic tube approximately 1 cm in diameter and 3 cm in length. Both the decibel meter and the earphones should be connected to the tube to simulate the volume produced within the ear canal.Note: During the data collection for the original publication, we used white noise to mask the coil clicking sound.29,30,31 However, since then, Russo et al. have introduced the TMS Adaptable Auditory Control (TAAC), an open-source MATLAB application designed to program and play masking noise.32 TAAC combines white noise with random coil-click-like rattling sounds, offering an effective solution for masking the coil click.

CRITICAL: The strong magnetic pulse of the TMS coil can interfere with standard earphones. Additionally, standard earphones might not offer sufficient protection from the loud TMS click. Therefore, we recommend using earphones that transmit the sound via a long tube and ensuring that all the electronic components of the earphones are positioned sufficiently far from the TMS coil. When choosing an earphone model, opt for a low-impedance type if directly connected to the laptop. High-impedance earphones will require a separate amplifier.29,30,31,32

CRITICAL: The strong magnetic pulse of the TMS coil can interfere with standard earphones. Additionally, standard earphones might not offer sufficient protection from the loud TMS click. Therefore, we recommend using earphones that transmit the sound via a long tube and ensuring that all the electronic components of the earphones are positioned sufficiently far from the TMS coil. When choosing an earphone model, opt for a low-impedance type if directly connected to the laptop. High-impedance earphones will require a separate amplifier.29,30,31,32

-

i.

-

h.Set up the equipment for TMS-EEG/EMG recordings:

-

i.Choose a TMS-compatible EEG amplifier.

-

ii.Set a high sampling rate of (> 5000 Hz) and the amplifier band-pass filter to 0.1–1250 Hz.

-

iii.Select the electrodes you want to use for the recording, in our case 62 EEG (Fp1, Fpz, Fp2, AF7, AF3, AF4, AF8, F7, F5, F3, F1, Fz, F2, F4, F6, F8, FT7, FC5, FC3, FC1, FCz, FC2, FC4, FC6, FT8, T7, C5, C3, C1, Cz, C2, C4, C6, T8, TP7, CP5, CP3, CP1, CPz, CP2, CP4, CP6, TP8, TP10, P7, P5, P3, P1, Pz, P2, P4, P6, P8, PO3, POz, PO4, PO7, O1, Oz, O2, PO8, Iz), a reference electrode (AFz), a ground electrode (TP9), and electrode for electrooculography (EOG) to monitor eye movements and a dipole electrode for the first dorsal interosseus (FDI) muscle to record MEPs.Note: The ground and reference positions should be chosen depending on the design of the experiment and TMS targets. In our study, we used AFz as a reference because it is located on the midline and remains relatively neutral with respect to our stimulation sites, left M1 and right DLPFC. TP9 was used as a ground, as it was far from both coils. In general, positioning the reference and ground electrodes farther from the TMS coils helps to prevent accidental contact, which contributes to maintaining high overall EEG signal quality.33

-

iv.Connect the EEG/EMG amplifiers to the EEG computer and the experimental computer, i.e., to mark the onsets of the TMS pulse events in the recorded EEG/EMG signals.Note: The setup specifics may depend on the recording system used. In our case, the EEG amplifiers were connected to the EEG computer through a USB adapter. The adapter was connected to the EEG amplifiers via fiber-optic cables and to the EEG computer with a USB cable. Furthermore, the EEG computer was connected to the experimental computer via a parallel port.

-

i.

-

i.Setup the frameless stereotactic neuronavigation:

-

i.Connect the infrared camera (Polaris Vicra) to the USB port of the neuronavigation computer.

-

ii.Place one tracker on each of the TMS coils and calibrate their positions.

-

iii.Ensure that the position of the infrared camera can detect both the participant’s head tracker and the coil trackers simultaneously (in our case, in front of the participant, approximately 2 m away).

-

iv.For each participant, upload their previously recorded structural T1-magnetic resonance image (MRI) into the neuronavigation software (Brainsight TMS, Rogue Resolutions Ltd), reconstruct the participant’s skin and curvilinear brain, select the anatomical landmarks (tip of the nose, nasion, tragus of the right and left ears) that will be used to co-register the participant’s head position, and mark the stimulation targets using predefined coordinates. For the left M1, find the omega shape of the central sulcus. The coil position will be further adjusted during the experimental phase based on the most effective location for inducing reliable MEPs. For other brain regions, MNI or Talairach coordinates can be selected from previous literature. For example, the right DLPFC coordinates in our study were taken from previous repetitive TMS studies on memory interaction (10,11; x = 40, y = 32, z = 30).Note: The setup specifics and procedures may depend on the neuronavigation system. For example, when using Brainsight, as long as the optical trackers’ position is secured and has not been changed, the coil does not need to be calibrated for each participant. In some neuronavigation systems, the tracker is integrated into the coils and the calibration is performed by the manufacturer. In this latter case, step 1 i iii of Experimental setting preparation can be skipped altogether.

CRITICAL: At this stage, you should be ready to run your experiment. Before recruiting participants for your study, run a pilot to ensure that everything is working as it should.

CRITICAL: At this stage, you should be ready to run your experiment. Before recruiting participants for your study, run a pilot to ensure that everything is working as it should.

-

i.

-

a.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Deposited data | ||

| Behavioral and TMS–EEG data | Bracco et al.1 | Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7891964 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Microsoft PowerPoint | Microsoft | https://www.microsoft.com/ |

| E-Prime | Psychology Software Tools, Inc. | RRID:SCR_009567 |

| MATLAB | MathWorks | RRID:SCR_001622 |

| Psychophysics Toolbox | https://github.com/Psychtoolbox-3/Psychtoolbox-3 | RRID:SCR_002881 |

| Brainsight | Rogue Research, Inc. | RRID:SCR_009539 |

| BrainVision Recorder | Brain Products GmbH | RRID:SCR_016331 |

| EEGLAB | RRID:SCR_007292 | |

| FieldTrip | https://www.fieldtriptoolbox.org/ | RRID:SCR_004849 |

| TMS-EEG signal analyser (TESA) code repository | Rogasch et al.34,35 | https://github.com/nigelrogasch/TESA.git |

| FastICA algorithm | Hyvärinen et al.36 | https://research.ics.aalto.fi/ica/fastica/ |

| Source-based artifact-rejection techniques | Mutanen et al.35 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2020.06.079 |

| Nonparametric cluster-based statistical testing of EEG data | Maris and Oostenveld37 | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.024 |

| Example preprocessing script | Rogasch et al.38 | https://github.com/nigelrogasch/DXM_TMS-EEG_paper/tree/master/pre_processing/tms_eeg_pipeline1 |

| Tutorial for time-frequency transformation | N/A | https://www.fieldtriptoolbox.org/tutorial/timefrequencyanalysis/ |

| Tutorial for cluster-based statistics | N/A |

https://www.fieldtriptoolbox.org/tutorial/cluster_permutation_freq/ https://www.fieldtriptoolbox.org/faq/how_can_i_test_an_interaction_effect_using_cluster-based_permutation_tests/ |

| Other | ||

| The New York Head (ICBM-NY) | https://www.parralab.org/nyhead/ | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.12.019 |

| Magstim Rapid2 Transcranial Magnetic Stimulator | Magstim Company | https://www.magstim.com/ |

| Insert earphones | RadioEar | https://www.radioear.us/ |

| Polaris Vicra for neuronavigation tracking | NDI | https://www.ndigital.com/ |

| TMS-compatible EEG system (BrainAmp) | Brain Products GmbH, Gilching, Germany | https://www.brainproducts.com/ |

| 62 Ag/AgCl-sintered electrodes | EasyCap GmbH, Herrsching, Germany | https://www.easycap.de/ |

| Abralyt | EasyCap GmbH, Herrsching, Germany | https://www.easycap.de/ |

| ECI Electro-Gel | Electro-Cap International, Inc. | https://www.electro-cap.com/ |

| EMG system (BrainAmp ExG) | Brain Products GmbH, Gilching, Germany | https://www.brainproducts.com/ |

Step-by-step method details

Note: This section provides a step-by-step guide for conducting TMS-EEG recordings. It assumes that each participant has already been screened for the inclusion criteria (i.e., eligibility for MRI and TMS as per international guidelines,39,40 no medical, neurological, or psychiatric history, normal or corrected to normal vision), has signed the consent form, and has undergone an MRI scan to acquire their T1. The details of the MRI scan are omitted here, as they are beyond the scope of this article.

Participant welcoming

Timing: 10 min

-

1.

Welcome the participant and provide an overview of the experimental procedure.

-

2.Explain the structure of the experiment:

-

a.Use a cover story when explaining the aim of the study to maintain participants’ naivety about the expected results and avoid any unintended biases.

-

b.Answer any open questions that the participant may have without compromising the cover story.

-

a.

EEG preparation

Timing: 45–60 min

CRITICAL: Careful EEG preparation is essential to record brain responses with a good signal-to-noise ratio (for a complete review, please see31,33,41).

Note: We used passive electrodes. Some of the described procedures and parameters may be different for active electrodes.

-

3.Fit the EEG cap correctly:

-

a.Measure the participants’ head diameter with a measuring tape and select the cap size accordingly (e.g., 58 cm cap).

-

b.Identify the vertex as the point equidistant from the nasion and inion and the left and right-ear landmarks.

-

c.Fit the cap such that Cz is located at the vertex.

-

d.Verify that the cap is positioned correctly, with the z channels aligned to the midline between the nasion and inion.

-

a.

-

4.

Connect the EEG cap to the EEG amplifier to monitor the electrode impedances.

-

5.Prepare the ground and reference electrodes:

-

a.Gently guide the hair away with a blunt syringe or cotton stick so that you can see the bare skin under the electrode cavity.

-

b.Gently apply the abrasive paste to the skin under the EEG electrode with a blunt syringe or cotton stick and scrub the skin.

-

c.Fill the electrode cavities with conductive electrode gel.

-

d.Ensure that both the ground and reference electrodes have impeccable impedances well below 5 kΩ.

-

a.

Note: Higher impedances may lead to larger artifacts when TMS pulses are applied.33

-

6.Prepare the other electrodes:

-

a.Gently guide the hair away with a blunt syringe or cotton stick so that you can see the bare skin under the electrode cavity.

-

b.Gently apply the abrasive paste to the skin under the EEG electrodes with a blunt syringe or cotton stick.

-

c.Fill the electrode cavities with conductive electrode gel.

-

a.

Ensure that all the EEG channels have an impedance below 5 kΩ.

Note: Consider using an elastic net placed over the EEG cap. This can help to ensure that the cap adheres closely to the scalp and minimize cap movement.

EMG preparation

Timing: 5 min

CRITICAL: EMG electrodes must be carefully placed to record MEPs with a good signal-to-noise ratio (for a complete review, please see42).

-

7.Place the active, reference, and ground electrodes over the FDI muscle using the belly-tendon montage:

-

a.Attach the active electrode to the belly of the FDI.Note: The belly can be identified as the thickest part of the muscle when the participant is performing a contraction, for example, by gently pushing the thumb and index fingertip toward each other.

-

i.Wipe the belly with a disinfecting solution and scrub the epidermis with an abrasive paste to ensure low connection impedance.

-

ii.Attach the EMG electrode using tape.

-

iii.If dry electrodes are used (e.g., similar to EEG) also apply the abrasive paste and a conductive gel under the electrode.

-

i.

-

b.Attach the reference electrode to the tendon of the FDI.

-

i.Identify the tendon of the FDI at the proximal phalanx of the index finger.

-

ii.Wipe the skin over the tendon with a disinfecting solution and scrape the epidermis with the abrasive paste to ensure low connection impedance.

-

iii.Attach the EMG electrode using tape.

-

iv.If dry electrodes are used also apply the abrasive paste and conductive gel under the electrode.

-

i.

-

c.Attach the ground electrode.

-

i.Wipe the skin over the end of the ulna bone with a disinfecting solution and scrape the epidermis with the abrasive paste to ensure low connection impedance.

-

ii.Attach the EMG electrode using tape.

-

iii.If dry electrodes are used also apply the abrasive paste and conductive gel under the electrode.

-

i.

-

a.

Head and coil co-registration for the neuronavigation

Timing: 15 min

Note: Neuronavigation ensures an accurate placement of the TMS coil on the scalp and its continuous monitoring during stimulation. The infrared camera tracks the locations of the reflective trackers both on the coil and on the forehead of the participant. When using Brainsight for neuronavigation (as in our case) for the software to reliably measure the location of the coil with respect to the head, both the coil and head trackers need to be registered.

-

8.Register the coil with the neuronavigation:

-

a.Fix the optical trackers to the coil and ensure that they are securely attached.

-

b.Use the coil calibration tool of the neuronavigation system to register the locations of the tracker with respect to the coil (please see step 1 i iii of experimental setting preparation).

-

a.

-

9.Register the head of the participant to the neuronavigation:

-

a.Attach the head tracker to the head of the participant.Note: The tracker position should be positioned where it does not interfere with the coil placement, facing the infrared camera and possibly not touching the EEG electrodes.

-

b.Register the landmarks (tip of the nose, nasion, and left and right ears) with a neuronavigation stylus.

-

c.Acquire additional scalp points to enhance the accuracy of the head registration.

CRITICAL: The head tracker should not move during the recordings. To monitor it, it is advisable to mark the location of the head tracker with a marker pen on the scalp. If the tracker moves accidentally, the registration of the participant’s head must be repeated.

CRITICAL: The head tracker should not move during the recordings. To monitor it, it is advisable to mark the location of the head tracker with a marker pen on the scalp. If the tracker moves accidentally, the registration of the participant’s head must be repeated.

-

a.

Motor-hotspot and motor-threshold determination

Timing: 20–30 min

Note: In our study,1 single pulses of TMS were delivered to the left M1 and right DLPFC at 80% of the rMT. To ensure that the stimulation location of left M1 and the stimulation intensity are set up accurately, both the cortical motor hotspot and rMT must be carefully mapped.

-

10.Identify the motor hotspot using neuronavigation:

-

a.Using the neuronavigation software and the MRI map of the participant, find the omega shape of the central sulcus.

-

b.Place the coil above the precentral gyrus, on the tip of the omega pointing to the posterior direction.

-

c.Set the orientation of the coil to be perpendicular with respect to the central sulcus.

-

d.Set the power of the TMS machine to 50% of the maximum stimulator output.

-

e.Start mapping different locations on the cortex to find a location that results in reliable ∼50-μV peak-to-peak amplitudes in MEPs.

CRITICAL: When moving the coil, always rotate the coil so that the orientation remains perpendicular with respect to the central sulcus.Note: Some neuronavigation systems allow for the adjustment of the coil orientation based on the maximum electric field (max E-field).

CRITICAL: When moving the coil, always rotate the coil so that the orientation remains perpendicular with respect to the central sulcus.Note: Some neuronavigation systems allow for the adjustment of the coil orientation based on the maximum electric field (max E-field). -

f.If no MEPs are found, increase the stimulation intensity in 2–3% increments. If several locations cause large MEPs, decrease the stimulation intensity.

-

g.Once the location that causes the most reliable and largest MEPs, check that the stimulation orientation is optimal by varying the coil angle in ∼15-degree steps.

CRITICAL: Ensure that the stimulated muscle is relaxed throughout the mapping. Monitor the EMG signal and make sure that no spikes reflecting pre-innervation of the muscle are present. If needed, ask the participant to relax. Placing a pillow beneath the arm can help.

CRITICAL: Ensure that the stimulated muscle is relaxed throughout the mapping. Monitor the EMG signal and make sure that no spikes reflecting pre-innervation of the muscle are present. If needed, ask the participant to relax. Placing a pillow beneath the arm can help.

-

a.

-

11.Determine the rMT of the participant:

-

a.Once the motor hotspot is found, give 20 TMS pulses and count the number of MEPs, whose peak-to-peak amplitude exceeds 50 μV.

-

b.Decrease the stimulation intensity until less than half of 20 pulses result in 50-μV MEPs.

-

a.

Note: Resting MT is the smallest intensity that produced at least 10/20 50-μV MEPs.43

Note: When determining MT, you can first decrease the stimulus intensity with larger increments (e.g. 3%). Once MT is approaching, adjust the stimulation intensity to a 1% decrease to find an accurate estimate of MT.

-

12.

Register the coil position corresponding to the MEP hotspot.

-

13.

If you have multiple target areas, retrieve their location as defined in step 1 i of experimental setting preparation.

Auditory noise masking settings

Timing: 20 min

CRITICAL: Because of the large mechanical forces acting upon the coils, each TMS pulse causes a loud click sound. This can cause measurable auditory EEG responses that hinder the interpretation of the genuine transcranially evoked potentials.14,44,45,46 To mitigate this, noise masking can be played to participants’ ears.

-

14.Attach the earphones:

-

a.Offer appropriately sized ear inserts and assist participants in correctly fitting the earphones into their ears.

-

b.Fix the air tubes to the shoulders with Velcro straps or tape to prevent the earphones from moving during testing.

-

a.

-

15.Adjust the noise level to mask the TMS clicks for each participant:

-

a.Fix the coil above the left M1 in the location identified during motor-hotspot mapping.

-

b.Tilt the coil so that the wings of the figure-of-eight coil are perpendicular to the scalp. This orientation minimizes any direct transcranial activation of the cortex while ensuring realistic TMS-click volume.

-

c.Find the minimum noise volume sufficient to mask the coil clicks.

-

i.Set up the noise level to a very low volume (e.g., to 20% of the maximum volume of the computer) and start playing the masking white noise through the earphones.

-

ii.Deliver TMS pulses at 80% of rMT and ask the participant to mark any heard coil clicks by raising their thumb.

-

iii.If the participant can correctly notice any of the TMS pulses, increase the noise volume by 5% and repeat the previous step.

-

i.

-

a.

CRITICAL: The TMS click produces a loud noise that poses a risk to the participant's hearing. To ensure their safety, only foam ear inserts that effectively dampen external sounds and provide hearing protection should be utilized. Additionally, ordinary earphones should not be used, because the TMS-induced magnetic fields can interfere with their functionality.

Note: Rt-TEP, an open-source tool for real-time visualization of TMS-evoked potentials can be used to further ensure the absence of auditory responses.25 Rt-TEP allows us to collect EEG responses to 20–30 TMS pulses and observe whether the noise masking modulates the resulting TMS-evoked potentials (TEPs). Adjust the noise masking and if N100 or P200 responses are attenuated consider further adjusting the noise level until their amplitude is reduced or the participant’s comfort threshold is reached.32

Note: To complement careful experimental strategies aimed at minimizing auditory-evoked responses, we suggest using a post-hoc control analysis to assess the impact of auditory and other sensory responses on the final EEG signal. When TMS intensity is individually tailored, such as using rMT, phosphene threshold, or TMS-evoked potential amplitudes,33 participants with higher thresholds—and thus higher absolute stimulation intensities—may exhibit EEG responses with stronger contamination by sensory artifacts.14,25 In a previous study, we conducted a regression (cluster analysis) using absolute intensity as the predictor and TEPs amplitude (across channels and time points) as the dependent variable.26 This allowed us to identify topographies at latencies typically attributed to multisensory indirect responses.14,44,45 Thus this approach may be used as a control analysis to identify potential residual effects of indirect multisensory activations, and account for them if needed.26

Baseline TMS-EEG recording

Timing: 25 min

Note: To assess the changes in brain resistance to external perturbation, first, we must record the EEG activity perturbed by TMS at baseline, i.e., prior to the behavioral task(s). This activity will then be compared with the one elicited following the execution of the behavioral task(s).

-

16.Adjust the stimulation parameters:

-

a.Position the TMS coil over the target areas:

-

i.For M1, use the neuronavigation to position the coil over the defined motor hotspot.

-

ii.For the other brain areas, use the neuronavigation system to position the coil such that its center lays over the chosen coordinates.

-

iii.Rotate the coil such that the current runs roughly perpendicular with respect to the closest sulcus.

-

i.

-

b.Set the stimulation intensity of both TMS machines to the chosen intensity, in our case 80% of rMT.

-

a.

-

17.

Instruct the participant to relax, avoid excessive voluntary blinking, and fixate the gaze on a cross on the screen.

-

18.

Turn the EEG recording on.

-

19.Measure the first block of TMS-EEG data (baseline):

-

a.Switch the noise masking on, using the defined volume to mask the coil clicks.

-

b.Launch the script controlling the TMS units and showing the fixation cross on the screen.

-

c.Once all the pulses have been delivered, switch off the noise masking.

-

a.

Pause point: 2 min. Let the participant have a break, move their shoulders, and drink water.

-

20.

Repeat step 19 two more times.

-

21.

Turn off the EEG recording.

CRITICAL: Monitor the EEG data quality throughout the experiment. If unusual artifacts occur, pause the experiment, and try to improve the data quality.

CRITICAL: Before launching the EEG recording, check that the storage space of the EEG computer is sufficient for recording all the EEG data.

Behavioral task(s) administration

Timing: It varies depending on the administered task(s)

Note: The behavioral task(s) administration depends on the chosen tasks. Their administration and instructions should be kept consistent across participants and groups.

Offline TMS-EEG recording

Timing: 25 min

Note: To assess the changes in network response to external perturbation during offline processing, the TMS-EEG recordings should be repeated immediately after the behavioral task(s).

-

22.

Repeat steps 16–21.

Expected outcomes

The proposed protocol leverages the integration of EEG and TMS to assess changes in brain network resistance to perturbation during offline brain processing, such as the interaction between different types of memory.1 By perturbing the ongoing activity of a brain area with single pulses of TMS and observing the induced perturbation through EEG, we can estimate the current state of the targeted network. By comparing the EEG response to TMS before and after the execution of the behavioral task(s), we can identify any change attributable to the offline process under investigation (Figure 2A).

In our study, we tested the hypothesis that when memory processing is ongoing, the relevant brain network exhibits increased resistance to external perturbation. This resistance, resulting from offline processing, could manifest as a reduction in oscillatory changes induced by TMS (Figure 2B). The primary processing may occur within a specific network and be supported by specific oscillatory activity. The correlation between the observed changes in resistance to TMS perturbation and the studied behavior would then establish a relationship between neural activity and the offline process under investigation (Figure 2C). This would provide essential information about the relationship between neurophysiological changes within the brain networks and behavioral outcomes.

Quantification and statistical analysis

CRITICAL: Analysis pipelines for TMS-EEG data depend on the study aim as well as on the laboratory environment, the equipment used, and the applied experimental parameters, all of which influence the distribution of noise and artifact signals. Therefore, the following analysis pipeline should be considered an informed example and may not be optimal for every scenario.33,47,48 For tutorials and/or concrete examples of similar analysis pipelines used in this study, please refer to the key resources table, which includes relevant links.

Behavioral data analysis

Timing: It varies depending on the chosen task(s)

Note: The behavioral data analysis depends on the chosen task(s). Choose the most appropriate approach to your data.

TMS-EEG preprocessing

Timing: 5 h per participant

Note: The signal obtained from TMS-EEG recordings can be affected by various artifacts induced by TMS itself. These include the electromagnetic, recharge, and TMS-evoked muscular artifacts, among others (for a comprehensive overview, please refer to;33). This section describes the preprocessing pipeline employed in our study.1 This pipeline serves the purpose of removing the noise and TMS-related artifacts and those commonly detected within EEG signals, such as ocular movements and blinks, persistent muscular artifacts, line noise, and the presence of channels with suboptimal signal quality (please refer to Figure 3 for a graphical representation of the main steps from the raw EEG signal to a cleaned dataset).

Figure 3.

Main steps of TMS-EEG pre- and post-processing, from the raw to the clean signal for one representative participant and one stimulated target (left M1)

(A) Butterfly plot of the raw TMS-EEG signal.

(B and C) (B) The segment of the signal containing the electromagnetic artifact generated by the TMS pulse (from −2 to 6 ms relative to the TMS pulse) is removed and replaced with a mirrored version of the baseline signal from −2 to −8 ms. The recharge artifact is identified and (C) interpolated using a spline interpolation function.

(D) A first round of ICA is used to remove the independent components corresponding to blinks and horizontal eye movements. The typical topographies of these components are shown on top, with an example of their time course on the bottom.

(E) The SOUND function is used to automatically detect and remove recording noise, with the signal shown before (in red) and after (in blue) noise suppression.

(F) The SSP-SIR function is used to suppress muscle artifacts time-locked to the TMS pulse, with the signal shown before (in red) and after (in blue) artifact removal.

(G) A second round of ICA is used to remove residual continuous muscle artifacts.

(H and I) (H) Data is band-pass filtered from 2 to 40 Hz, and finally (I) transformed into ERSP. Butterfly plots represent the EEG signal around the TMS pulse (0 ms), with each blue and red line representing one of the 62 electrodes. The time-frequency plot represents the signal around the TMS pulse (0 ms) as an average across all 62 electrodes. The vertical black lines correspond to the TMS pulse.

-

1.Pre-process the EEG data with EEGLAB (UC San Diego, La Jolla CA, USA49) and the TMS–EEG signal analyzer plugin (TESA34,35):

-

a.Open the EEG data from one group (in our case, main or control group), measurement time (baseline or offline), and stimulated site (in our case, DLPFC or M1; Figure 3A) with EEGLAB.Note: TMS-EEG data from different experimental conditions are often concatenated at the start of the analysis pipeline and preprocessed together. The primary rationale is that when steps like ICA are used on the data, components are removed equally across conditions, thus preventing any bias deriving from the removal of different ICs across conditions. Additionally, having a larger dataset improves ICA estimation. However, when datasets have significantly different signal profiles—such as when stimulating different cortical sites or when data comes from separate sessions with slight variations in electrode positions—ICA decomposition can be sub-optimal. This is due to changes in artifact profiles and neural activity, which may affect ICA performance.50 For this reason, we chose to preprocess the data separately for each stimulation site and measurement time to ensure more accurate artifact removal and signal isolation. However, we recommend making this decision based on the specific characteristics of your dataset.Note: Data recorded with the Brain Vision Recorder requires the addition of the Brain Vision plugin for EEGLAB.

-

b.Construct the channel structure of the dataset by importing the channel locations from the standard BESA file and comparing the channel labels in the recorded EEG header file to the BESA template with the theoretical channel locations in the 10–20 EEG coordinate system.

-

c.Segment the data into 2400-ms long epochs, each consisting of 1200 ms of data around the TMS pulse.

-

d.De-mean the data.

-

e.Remove the line noise by fitting a perfect 50-Hz sine wave to the data using standard least-squares fitting.Note: When fitting the sine, exclude the time interval 0–300 ms to avoid fitting the sine wave to the meaningful TMS-evoked potentials.38Note: The frequency of the line noise can be 50 or 60 Hz, depending on the continent where the data has been recorded. There are several ways to filter this noise. Some other researchers apply a band-stop filter from 48 to 52 Hz or from 58 to 62 Hz, depending on the line noise frequency. However, in the presence of large TMS-evoked artifacts, this latter approach can lead to ringing artifacts.

- f.

-

g.Identify the recharge artifact (Figure 3B), cut the signal around the artifact, and interpolate it based on the surrounding signals using a spline interpolation function (38; Figure 3C).Note: For some TMS devices such as Magstim, the recharging delay depends on the stimulation intensity, and the onset and end of the recharging pulse artifact must be visually identified for each dataset before rejecting and interpolating this artifact.53 If other devices are used, the recharge artifact may not be present as some allow postponing the recharge further from the signal of interest.

-

h.Select all channels except the EOG and EMG.

-

i.Perform the independent component analysis (ICA;36; Figure 3D):

-

i.Remove very noisy channels from the dataset to prevent them from interfering with the ICA algorithms.

-

ii.Determine the maximum number of independent components via singular value decomposition and select the number of ICs accordingly.Note: A common approach is to plot the singular values in descending order and find the “kink” or “elbow” in the plotted singular value spectrum. The singular value index of the “kink” corresponds to the maximum number of included ICs.

-

iii.Run ICA using EEGLAB functions.

- iv.

-

v.Update the dataset by removing the selected IC.

-

i.

-

j.High pass filter the data from 2 Hz.

-

k.Baseline corrects the data using a baseline from −1000 to −10 ms with respect to the TMS pulse.

-

l.Visually inspect the data and reject the noisiest trials.

- m.

-

n.De-mean data.

- o.

- p.

-

q.Visually inspect the data and reject the noisiest trials.

-

r.Low pass filter the data, filtering from 40 Hz (Figure 3H).

-

s.Re-segment the data into 2000-ms long epochs, each consisting of 1000 ms of data around the TMS pulse to remove possible ringing artifacts due to filtering the dataset after dividing it into epochs.

-

t.Baseline correct the signal using a baseline of −5 to −500 ms with respect to the TMS pulse.

-

u.Visually inspect the data for the last time and reject the noisiest trials.

-

v.Save the preprocessed data.Note: One limitation of the applied spatial preprocessing methods, ICA, SOUND, and SSP-SIR, is that they all reduce the rank of the data.47 This must be considered when performing inverse estimation on the preprocessed data. Adequate regularization can mitigate the risk of overfitting during inverse estimation. Additionally, the gradual reduction in rank should be recognized throughout the preprocessing pipeline. For example, the maximum theoretical number of independent components (ICs) in a second round of ICA will be lower than in the first round, due to the rank reduction from the initial ICA, SOUND, and SSP-SIR.

CRITICAL: Visualize the data after each step to check that the analysis pipeline is not introducing any filtering artifacts, such as ringing around sharp artifact deflections.

CRITICAL: Visualize the data after each step to check that the analysis pipeline is not introducing any filtering artifacts, such as ringing around sharp artifact deflections.

-

a.

Sensor space EEG data analysis

Timing: 2 months

Note: This step enables the transformation of the sensor space EEG data into time-frequency data. To determine the effects of offline processing on the network resistance to external perturbation, we computed the event-related spectral perturbation (ERSP). ERSP is a measure that quantifies the ability of a specific event, e.g., the TMS pulse, to perturb the spontaneous spectral activity.57 Additionally, it is possible to perform a control analysis to assess how spontaneous oscillatory activity is affected. For this type of analysis, we can analyze the oscillatory activity not affected by the TMS pulses; i.e., prior to the TMS pulse.

Note: Typically, the effects of TMS perturbation on brain activity are observed with EEG below 40 Hz and last for about 300 ms following the pulse.58,59 Therefore, we restricted our analysis to the 2–40 Hz range and the 0–350 ms window following the pulse for ERSP. For spontaneous oscillatory activity, we analyzed the time window from −450 to −100 ms before the pulse, for consistency.

-

2.

Import the data into MATLAB’s FieldTrip toolbox.60

-

3.Compute the ERSP (Figure 3I):

-

a.Transform each trial into the time-frequency domain by applying a fast Fourier transform (500 ms sliding time windows moving in 20 ms steps, using a Hanning taper).

-

b.Transform the power at each frequency into decibels relative to the corresponding frequency-specific mean power during the 500 ms–100 ms period before the TMS pulse.

-

c.Compute the average across the trial-specific TMS-elicited power changes to obtain ERSP.

-

d.To factor out variability across participants in the ERSP at baseline,61,62,63 normalize the data of the baseline and offline measurement times by dividing the three-dimensional ERSP matrices (channels x time x frequency) by a common normalizer, i.e., the Frobenius norm of the 3D ERSP matrix of the baseline measurement time.

-

a.

-

4.Statistically compare changes in the TMS-elicited ERSP and the spontaneous oscillatory activity due to offline processing across your two experimental conditions (main or control group) by using a 2-by-2 non-parametric cluster-based statistics analysis using MATLAB and FieldTrip:37Note: The same analysis should be performed separately for data recorded following TMS over each target area and for both ERSP and spontaneous oscillatory activity data.

-

a.Restrict the data according to the research question:

-

i.For ERSP data, restrict the signal in time from 0 to 350 ms following the TMS.

-

ii.For spontaneous oscillatory activity data, restrict the signal in time from −450 to −100 ms before the pulse.

-

iii.In both cases, restrict the signal in frequencies from 2 to 40 Hz, while including all channels.

-

i.

-

b.Prepare a structure containing information about which channels are considered neighbors of each other. Use the 'triangulation' method based on a 2D projection of the channel positions.

-

c.Organize the data depending on the effect to be tested:

-

i.To test for the effect of Time (offline vs. baseline; within-group factor), merge the baseline data of the two groups to be compared (main and control group).

-

ii.To test for the Time∗Group interaction effect compute the difference between the offline and the baseline ERSP values in each measurement time (offline minus baseline).

-

i.

-

d.Choose the cluster-based analysis parameters:

-

i.Select the Monte Carlo method for calculating the significance probability, which estimates the p-value under the permutation distribution.

-

ii.Use the previously prepared neighbors’ structure and choose ‘2’ as the minimum number of channels required for a selected sample to be included as a part of a cluster.

-

iii.Select the statistical test to be used: the dependent samples T-test for the Time or Group (within-group) comparisons or the independent samples T-test for the Group (between-group) comparisons.

-

iv.Set the critical T score to be used as a threshold (α = 0.05) to determine, which channels-time-frequency samples are considered as significant.Note: The critical T-score value does not affect the family-wise error rate, i.e., the false alarm rate, at the final cluster-statistics level. It is only used to decide whether a sample should be included within a cluster of samples.

-

v.Set the initial T-tests to be run as two-tailed.

-

vi.Select the nonparametric statistical testing method (cluster) to correct for multiple comparisons and control for the family-wise error rate.

-

vii.Set the nonparametric cluster statistics to be run as two-tailed.

-

viii.Select the critical value to be used to threshold the T-statistics to control the false alarm rate of the permutation test (α = 0.05).Note: When running a two-tailed test, the results should be corrected. Fieldtrip gives two options for this correction: 1) cfg.correcttail = 'alpha'; which divides the set alpha level by two. Please note that, if this option is chosen, the reported p values will have to be corrected: if p < 0.5, then p = p∗2; if p > 0.5 then p = 2∗(1-p). 2) cfg.correcttail = 'prob'; which automatically multiplies the p-values with a factor of two and compares them to the original alpha level.

-

ix.Select the test statistic that is evaluated under the permutation distribution. Set this to a maximum value of the cluster-level statistics to which the actual clusters obtained from the planned tests are compared.Note: Specifically, during the permutation testing, the cluster-level statistics of each actual cluster will be compared against the distribution of maximum cluster-level statistics generated from random partitions of the data. Only those clusters that are larger than (1- α)∗100% of the simulated maximum cluster-level statistics are considered significant.

-

x.Select 10000 as the number of randomizations used to compute the nonparametric cluster statistics.

-

xi.Define the analysis design, specifying only the independent variable for paired T-test analysis, and both the independent variable and the number of subjects for unpaired T-tests.

-

i.

-

e.In the case of significant Time∗Group interaction effects, perform post-hoc cluster tests to explore the associated effects of time (offline vs. baseline) within each group (main vs. control group). This analysis should be run similarly to when testing the effect of Time but this time for each group separately.Note: Before performing the above-mentioned statistical comparisons, we advise ensuring that the baseline TMS-EEG recordings are not different across groups.

-

a.

-

5.Test the relationship between the ERSP data and behavior using two-tailed Spearman correlation cluster test statistics:

-

a.Select the behavioral measure that best aligns with your hypothesis.

-

b.Restrict the EEG signal in time from 0 to 350 ms following the TMS pulse, while all channels should be included.

-

c.Normalize the EEG data of the baseline and offline measurement times by dividing the three-dimensional ERSP matrices (channels x time x frequency) by a common normalizer, the Frobenius norm of the 3D ERSP matrix of the baseline measurement time.

-

d.To test for a frequency-based dissociation in behavioral performance, restrict the signal into two separate frequency bands (i.e., alpha, 8–12 Hz; beta, 13–23 Hz) and run the correlations for the two frequency bands separately.

-

e.Use all previously used parameters in the cluster testing, choosing the Spearman correlation test as the test statistic instead of T-tests.

-

a.

Source space EEG data analysis

Timing: 2 months

Note: To estimate the changes induced by offline processing directly at the cortical level, we performed the time-frequency analysis also in the source space.

-

6.Prepare the forward model and EEG datasets for subsequent inverse estimation.

-

a.Download the volumetric mesh from the open-source New York Head and the lead field matrix derived from its forward model.64Note: We used an average head model and lead-field matrix, but individual head models and lead-field matrices may be also computed.

-

b.Select the 2000-dipole model with free dipole orientations from the head-model structure.Note: The coarse head model was chosen to enhance the time-frequency and clustering computations. The free dipole model was chosen instead of the cortically constrained version because the exact cortical curvature of the average head model will not align perfectly with any of the participant-specific anatomies. The free dipole orientation ensures that the inverse estimation will be more robust against such anatomical imperfections.

-

c.Read the channel locations from the preprocessed EEG dataset and select the subset of rows of the lead-field matrix in the correct order.

-

d.Transform the lead-field matrix to the average reference.

-

e.Downsample the EEG data to 125 Hz.Note: The data was downsampled again to enhance the time-frequency and clustering computations.

-

a.

-

7.Compute the ERSP values for each cortical source, stimulus location, measurement time, and group.

-

a.Project the TMS-EEG signal of each participant, stimulus location (e.g., M1 vs. DLPFC), measurement time (baseline vs. offline), and group (main vs. control group), to the source space. Estimate the source activity, using minimum-norm estimation with singular-value-truncated regularization.65Note: The regularization level should be set to prevent overfitting noise while minimizing the discrepancy between the true and modeled EEG signals. The exact truncation level depends on the signal-to-noise ratio and dimensionality of the data. In our original study, we regularized the inverse estimates by retaining the 30 most significant dimensions.

-

b.Apply a wavelet transformation to each source time course enabling their representation in the time-frequency domain.

-

i.Specify the transformation parameters by setting the minimum number of cycles to 3 and adjusting the width of the Morlet wavelets to 0.5.

-

ii.Use a pad ratio of 1 to enhance the transformation’s precision and set the maximum frequency of interest to 30 Hz.Note: While these choices limit the frequency range of interest to 6–30 Hz, they make the source-space time-frequency analysis computationally feasible.

-

i.

-

c.Compute the ERSP for each cortical source, relative to the signal before the TMS pulse.

-

d.Normalize each of the source-specific ERSP maps with respect to the baseline session. As the normalizing factor, use the Frobenius norm of the channel x frequency x time-points matrices, using all the channels, all the studied frequencies (6–30 Hz), and the time points after the TMS-pulse.

-

a.

-

8.Highlight significant differences between the baseline to offline recording (effect of Time; offline vs. baseline; within-group) in the source space using a non-parametric permutation approach66:

-

a.For each participant, compute the ERSP changes from baseline to offline (offline minus baseline) in each source.

-

b.Draw 1000 random partitions, where the baseline and offline ERSP values are randomly shuffled within each participant. For each partition, perform step 28b.

-

c.For each time-frequency point, compute the maximum statistics across the whole cortical space and random partitions.

-

d.Label each time-frequency-spatial point as significant if the true ERSP difference exceeds 95% of the maximum statistics.

-

e.For each source, compute the average ERSP change across all the significant time-frequency points and all participants (from 0 to 350 ms after the TMS onset).

-

a.

-

9.Highlight the significant ERSP differences between groups.

-

a.Use the difference between offline and baseline recordings computed in step 28 for each group (main vs. control group).

-

b.Draw 1000 random partitions, where the participants are randomly shuffled between the compared groups (e.g., main and control group).

-

c.For each partition, perform step 28b.

-

d.For each time-frequency point, compute the maximum statistics across the whole cortical space and the random partitions.

-

e.Label each time-frequency-spatial point as significant if the true difference (main vs. control group) in the ERSP changes (baseline vs. offline) is larger than 95% of the maximum statistics.

-

f.For each source, compute the mean difference between the groups in ERSP change across all the significant time-frequency points.

-

a.

Note: This analysis should be performed separately for the stimulated targets (e.g., DLPFC and M1).

Limitations

TMS-EEG can be effectively used to evaluate the resistance of brain networks to external perturbations.7,58,59 However, when combined with EEG, TMS can introduce several types of artifacts and undesired indirect responses.26,44,45,67,68 Notably, TMS-induced muscle artifacts can significantly compromise the quality of the EEG signal, particularly when the regions of interest are distant from the midline of the scalp.13,69 For instance, stimulating the DLPFC is more likely to generate muscle artifacts compared to M1 stimulation.70 Additionally, inducing stronger muscle contractions may lead to more pronounced unwanted indirect cortical activations associated with multisensory responses.26 Both muscle artifacts and undesired responses can introduce bias in the interpretation of results.

In our study, we addressed this potential issue by using effective artifact-rejection techniques35,54,55,56 and implementing a test-retest design involving three distinct groups of participants performing different sets of behavioral tasks.1 This approach assumes that TMS should elicit comparable muscle artifacts and unwanted multisensory responses across sessions and groups. Future works could further investigate this matter, for example, by targeting both the left and right DLPFC. The stimulation of both regions would evoke consistent TMS-induced muscle artifacts and somatosensory responses.

In the original study, we used standard white noise to mask the TMS-coil clicks. We now encourage the adoption of more advanced methods to mitigate auditory responses, employing white noise masking combined with specific time-varying frequencies of the TMS click.32 Nowadays, it is also possible to visualize in real-time the responses evoked by TMS to optimize cortical activation and ensure that somatosensory and auditory responses to TMS stimuli are negligible.25 Some groups also promote the use of a thin foam layer between the TMS coil and the EEG cap to reduce bone conduction of the sound, and the incorporation of a realistic sham condition that elicits comparable artifacts and unwanted indirect cortical responses.14,67,71

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

During the EEG preparation, some of the electrodes might have impedances exceeding 5 kΩ.

Potential solution

-

•

You can re-scrub the surface of the skin with a cotton stick.

-

•

Double-check that you see the skin of the participant through the hole of the electrode.

-

•

Double-check that the electrode chip or c-ring is not dirty. If dirty, gently clean the electrode with a damp cotton stick.

-

•

Refill the electrode cavity with the conductive electrode gel.

Problem 2

EMG signals can be noisy and suffer from large line noise (at 50 or 60 Hz, depending on the continent).

Potential solution

-

•

Make a twisted pair of the active and reference electrodes, which minimizes the area formed by electrodes. This minimizes the loops between the leads and thus, the coupling of magnetic fields to the EMG measurement.

-

•

Move as much of the EMG cables to lie on the participant’s lap.

Problem 3

The infrared camera might fail to detect the participant’s or the coil’s trackers.

Potential solution

-

•

Ensure the camera is correctly connected to the power and the neuronavigation computer.

-

•

Ensure that the camera position enables the detection of all trackers concurrently.

-

•

Open the neuronavigation software section to visualize the camera detection range.

-

•

Make possible adjustments to the position and height of the camera based on the visual feedback provided by the neuronavigation software.

-

•

Ensure there are no potential sources of interference with the infrared lights used by the neuronavigation camera. These could include physical obstructions, strong ambient light, other infrared devices, materials and surfaces that may reflect or distort the infrared signals, etc.

Problem 4

The anatomy of the participant differs from the stereotypical representation of the motor cortex, described in detail in,72 and identifying the omega shape in the precentral gyrus can be difficult.

Potential solution

-

•

As a starting point, one can place the coil above the C3 channel and double-check using the neuronavigation that the coil center is located above the precentral gyrus and that the orientation of the coil is approximately perpendicular with respect to the central sulcus.

Problem 5

Unusual artifacts can occur during the EEG recordings.

Potential solution

-

•

Check and reduce any loops between the leads to avoid interference.33

-

•

Make sure the EEG cables are not pulling or adding any strain to the electrodes.

-

•

Check whether changing the arrangement of the electrodes’ leads attenuates the artifact.73

-

•

Check EEG electrode impedances.74 During long experiments, the conductive gel can dry out, reducing conductivity and increasing impedance. Reapply conductive gel if necessary.

-

•

Make sure the participant is seated comfortably. Discomfort can lead to muscle contractions, which may introduce artifacts into the EEG.

-

•

Remind participants to minimize movement and avoid blinking or clenching their jaw during critical recording periods.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Edwin M. Robertson (edwin.robertson@glasgow.ac.uk).

Technical contact

Technical questions on executing this protocol should be directed to and will be answered by the technical contacts, Martina Bracco (martina.bracco@icm-institute.org) and Tuomas P. Mutanen (tuomas.mutanen@aalto.fi).

Materials availability

This study did not generate any novel unique reagents.

Data and code availability

Original data have been deposited to Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7891964. References to software toolboxes used, as well as example data analysis scripts are provided in the key resources table. Any additional information is available from the lead and technical contacts upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR, FA9550-16-1-0191; Virginia, USA; FA9550-21-1-7057; London, UK) for supporting this work and for additional fellowship support (Marie Skłodowska-Curie 897941 to M.B.; Academy of Finland 321631 to T.P.M.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.R.; methodology, M.B., T.P.M., D.V., G.T., and E.M.R.; investigation, T.P.M. and M.B.; formal analysis, M.B. and T.P.M.; writing – original draft, M.B. and T.P.M.; writing – review and editing, M.B., T.P.M., D.V., G.T., and E.M.R.; visualization, M.B. and T.P.M.; funding acquisition, E.M.R.

Declaration of interests

T.P.M. has received consultation fees from Nexstim Plc (Helsinki, Finland) and is currently employed at Bittium Ltd (Oulu, Finland).

Contributor Information

Martina Bracco, Email: martina.bracco@icm-institute.org.

Tuomas P. Mutanen, Email: tuomas.mutanen@aalto.fi.

Edwin M. Robertson, Email: edwin.robertson@glasgow.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Bracco M., Mutanen T.P., Veniero D., Thut G., Robertson E.M. Distinct frequencies balance segregation with interaction between different memory types within a prefrontal circuit. Curr. Biol. 2023;33:2548–2556.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buzsáki G. Neural Syntax: Cell Assemblies, Synapsembles, and Readers. Neuron. 2010;68:362–385. doi: 10.1016/J.NEURON.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buzsáki G., Draguhn A. Neuronal olscillations in cortical networks. Science. 2004;304:1926–1929. doi: 10.1126/SCIENCE.1099745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bortoletto M., Veniero D., Thut G., Miniussi C. The contribution of TMS–EEG coregistration in the exploration of the human cortical connectome. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015;49:114–124. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUBIOREV.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thut G., Miniussi C. New insights into rhythmic brain activity from TMS-EEG studies. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009;13:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakatos P., Gross J., Thut G. Current Biology Review A New Unifying Account of the Roles of Neuronal Entrainment. Curr. Biol. 2019;29:R890–R905. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.07.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vernet M., Bashir S., Yoo W.K., Perez J.M., Najib U., Pascual-Leone A. Insights on the neural basis of motor plasticity induced by theta burst stimulation from TMS–EEG. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2013;37:598–606. doi: 10.1111/EJN.12069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown R.M., Robertson E.M. Behavioral/Systems/Cognitive Off-Line Processing: Reciprocal Interactions between Declarative and Procedural Memories. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10468–10475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2799-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutanen T.P., Bracco M., Robertson E.M. A Common Task Structure Links Together the Fate of Different Types of Memories. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:2139–2145.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen D.A., Robertson E.M. Preventing interference between different memory tasks. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:953–955. doi: 10.1038/NN.2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tunovic S., Press D.Z., Robertson E.M. A Physiological Signal That Prevents Motor Skill Improvements during Consolidation. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:5302–5310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3497-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosha N., Robertson E.M. Unstable Memories Create a High-Level Representation that Enables Learning Transfer. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mutanen T., Mäki H., Ilmoniemi R.J. The effect of stimulus parameters on TMS-EEG muscle artifacts. Brain Stimul. 2013;6:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]