Abstract

Objective:

To summarize how Asian Americans negotiate involvement in shared decision-making (SDM) with their providers, the cultural influences on SDM, and perceived barriers and facilitators to SDM.

Methods:

This is a systematic review of qualitative studies. We searched six electronic databases and sources of gray literature until March 2021. Two reviewers independently screened studies, performed quality appraisal, and data extraction. Meta-synthesis was performed to summarize themes using a three-step approach.

Results:

Twenty studies with 675 participants were included. We abstracted 275 initial codes and grouped these into 19 subthemes and 4 major themes: (1) negotiating power and differing expectations in SDM; (2) cultural influences on SDM; (3) importance of social support in SDM; and (4) supportive factors for facilitating SDM.

Conclusions:

Asian Americans have important perspectives, needs, and preferences regarding SDM that impacts how they engage with the provider on medical decisions and their perception of the quality of their care.

Practice implications:

Asian American patients valued good communication and sufficient time with their provider, and that it is important for health professionals to understand patients’ desired level of involvement in the SDM process and in the final decision, and who should be involved in SDM beyond the patient.

Other:

This systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021241665).

Keywords: Systematic review, Decision making, shared, Asian Americans, Patient preference

1. Introduction

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a process where patients and providers work together to make a health-related decision that is best for the patient [1]. SDM has been recognized as the pinnacle of patient-centered care and previous research has found that SDM can lead to better knowledge, better patient satisfaction and trust, less decisional conflict, improved adherence to treatment, and better self-reported health [2,3,4]. However, majority of SDM research has been conducted within a relatively homogenous cultural frame, and little is known about the SDM preferences of Asian Americans, the fastest growing racial or ethnic group in the US [5,6].

While there is a recognition that culture influences the SDM process and that there is a need for culturally appropriate SDM and decision tools [5,7], there is still a gap in knowledge about how Asian Americans approach SDM with their providers, their desired roles and level of involvement, and what promotes or impedes their engagement in SDM. For instance, previous studies have highlighted Asian Americans’ preference for making important health decisions collectively with family members [8,9,10,11]; yet, most SDM research and decision tools conceptualize SDM as between patients and providers only. In addition, cultural values such as filial piety, collectivism, preservation of harmony, and respect for providers’ authority, may influence how they communicate with providers, their preferences for involvement in SDM, and how they make health decisions [9]. Finally, Asian Americans, of which approximately 70% are immigrants [12], face systemic barriers to health care due to language barriers, financial barriers, low health literacy, and difficulties navigating the US healthcare system [13]. Understanding their SDM needs and preferences is important in addressing Asian American health needs and bridging health disparities faced by this group.

To address this gap in knowledge, we conducted a systematic review of qualitative studies to examine how Asian Americans negotiate involvement in SDM with their providers, the cultural influences on SDM, and their perceived barriers and facilitators to SDM. There is an emerging body of formative qualitative studies addressing SDM among Asian Americans, as well as studies that are not explicitly about SDM but revealed perceptions of SDM within focus group and interview data. The focus on qualitative studies in this review allows us to capture the richness of the data and to allow for the identification of patterns and themes. Results from qualitative work was also better aligned with our purpose of examining contextual and cultural influences that may not be readily apparent with quantitative research methods.

2. Methods

We reported our findings in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and the ENTREQ Statement (Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research) [14,15].

2.1. Eligibility criteria

We included qualitative studies conducted in the U.S. reporting on SDM, in any health context, among Asian American adults living in the U.S. (includes Southeast Asian, South Asian, and East Asian sub-groups). We only included studies conducted in the US as Asian Americans’ experiences with SDM are unique to the US context, health care system, and lived experiences with US providers. If a study used mixed methods, only findings from the qualitative portion were included. Studies that focused on information-giving from clinicians were only included if they were in the context of SDM where there is more than one option for the patient.

2.2. Data sources

We searched 6 electronic databases in March 2021 (i.e., MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Sciences, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library). Sources of gray literature were searched through Google Scholar (first 100 search results) and ClinicalTrials.gov. Reference lists of relevant studies were also hand searched.

2.3. Electronic search strategy

An information specialist (YG) built the search strategy. The search was limited to populations in the U.S. and English language publications. We included terms related to Asian Americans and SDM (see Appendix Table 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy).

2.4. Study screening methods

We screened the title, abstract, and full-text of all articles retrieved from the search. Two reviewers (NQPT and KGM) independently screened studies for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by a third author (MLO or RJV).

2.5. Data collection process and data items

Two reviewers (NQPT and KGM) independently extracted data from included studies using a standardized pilot-tested form (see Appendix Table 2). Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by a third author (MLO or RJV).

2.6. Study risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (NQPT and KGM) independently conducted risk of bias assessment using the Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research from the Joanna Briggs Institute [16]. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by a third author (MLO or RJV).

2.7. Synthesis methods

Information from the results section of the abstract and the main text were synthesized using Atlas.TI (Scientific Software Development GmbH). For mixed-method studies, we analysed the qualitative components with Asian patients. For studies which included other types of study populations (e.g. health professionals, patients of other ethnic groups), we analysed the portions of the findings pertaining to Asian Americans. Four out of the 5 authors have expertise in SDM research. The lead author (NQPT) is a cultural insider with experience conducting culture-centered qualitative work, MLO is also member of a cultural minority and a knowledge synthesis researcher who provided guidance on the methodology of the systematic review.

Our meta-synthesis incorporated an inductive thematic analysis approach with three steps: (1) initial coding (coding the findings lineby-line to identify pertinent concepts), (2) descriptive coding (developing illustrative themes by grouping initial codes), and (3) analytic coding (grouping, analysing, and interpreting descriptive codes to identify broad analytical themes). Two reviewers (NQPT and KGM) independently conducted data synthesis and discussed codes after every coding step, before moving on to the next coding step. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by a third author (MLO or RJV). After the data synthesis was complete, all codes were presented to the study team for feedback. The coding process was iterative; for instance, after discussion with the study team, descriptive codes were changed based on new perspectives from forming the analytic themes.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

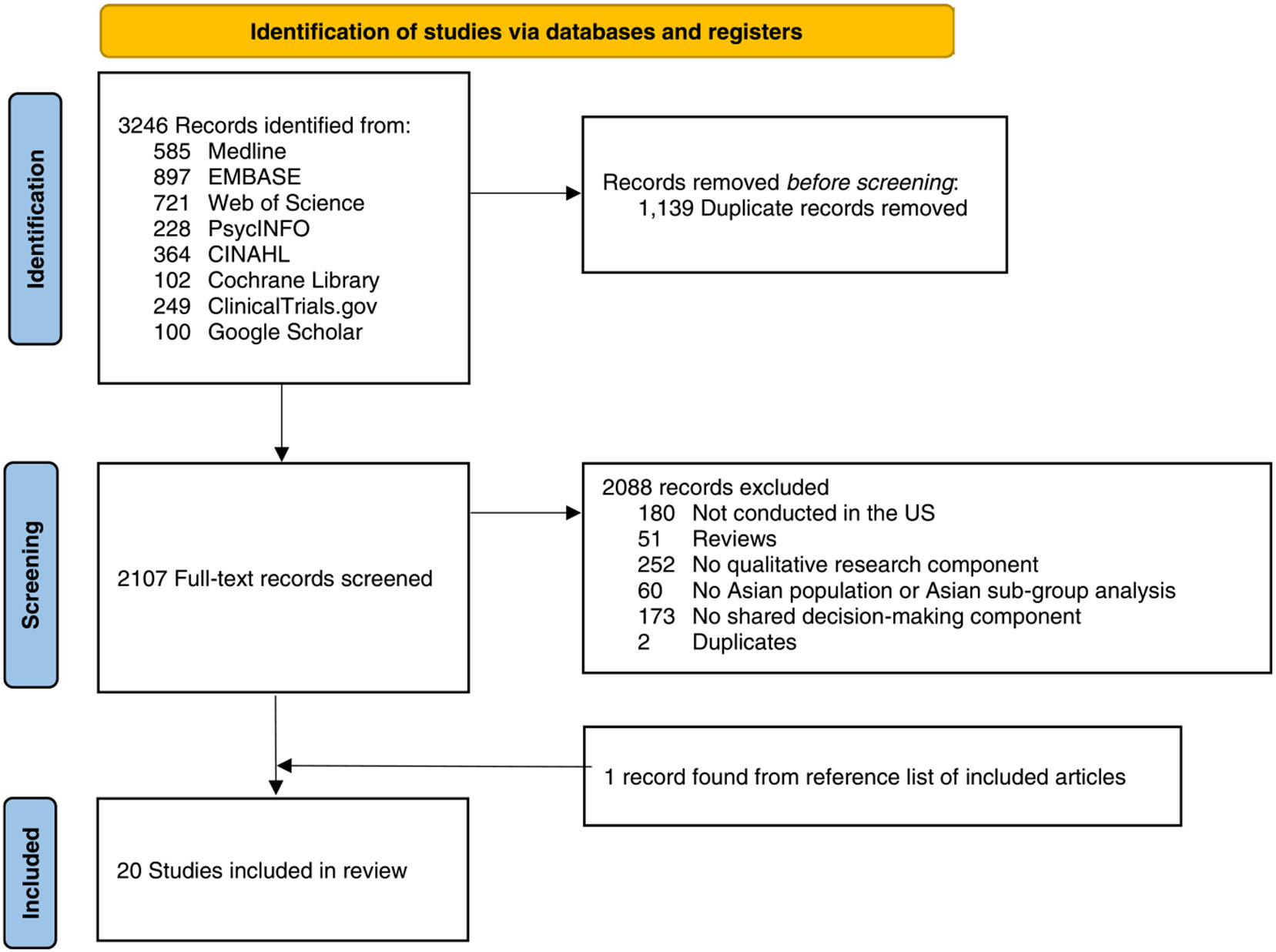

The flow diagram of study selection is in Fig. 1. We identified 2107 unique records and 20 studies met our eligibility criteria.

Fig. 1.

This flow chart illustrates the search strategy used to identify studies for inclusion in the current review.

3.2. Study and participant characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the study characteristics and Table 2 summarizes the participant characteristics. Of the 20 included studies, one study was a doctoral dissertation, and the other 19 studies were peer-reviewed publications. Studies were published between 1998 and 2020. The studies involved a total of 675 individuals. Study methods included interviews (n = 8), focus groups (n = 6), a combination of the two (n = 4), interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic observations (n = 1), and a case study (n = 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-synthesis.

| Source | Health Context | Study Objective | Inclusion / Exclusion Criteria |

Sampling Strategy | Study Design | Sample Size |

Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hesel et al. 2020[33] | End of life decision making | Explore the Hmong American beliefs that determine end-of-life care goals and strategies | 18 years and older, currently providing care to a seriously ill family member or who had done so in the past year | Purposive sampling | 20 interviews | 20 | None reported |

| Chang et al. 2020[26] | Hypertension management | Explore differences between Chinese American seniors’ descriptions of current and desired physician roles in hypertension management | 65 years or older, selfidentify as Chinese American, born outside of the USA, previous diagnosis of hypertension, prescribed antihypertensive medication, had a primary care physician, had health insurance, and could sit for an hour-long interview or a 1.5-h FG. Seniors excluded if they had a history of stroke, required help with medication administration, did not pass a 6-item cognitive screening, or were enrolled in a hypertension management program. | Not reported | 15 interviews, 4 focus groups | 57 | UCLA/Hartford Center of Excellence; UCLA NRSA General Internal Medicine Fellowship in Primary Care and Health Services Research; Los Angeles Stroke Prevention/Intervention Research Program (SPIRP) in Health Disparities Fellowship; UCLA Faculty Training Program in Geriatric Medicine, Psychiatry and Dentistry; the National Institute on Aging [grant number 1K24AG047899–01 to Dr. Sarkisian]; UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NIH/NCATS Grant # UL1TR001881); NIA Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research IV / Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly III |

| Bi et al. 2019[31] | Shared decision making about mental health | Identify barriers and facilitators to effective shared decision making, particularly regarding mental health decisions | Self-identified as AAPI, men who have sex with men (MSM), men who have sex with both men and women (MSMW), women who have sex with women (WSW), women who have sex with men and women (WSWM), and/or identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or genderqueer. | Purposive sampling | 40 interviews, 2 focus groups | 50 | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (IU18 HS023050) |

| Jun et al. 2018[23] | Prenatal genetic testing | Understand prenatal genetic testing decision-making processes | Having a high-risk pregnancy as identified by an obstetrician, recommended for genetic testing at 12–20 weeks’ gestation because of having at least one abnormal result of genetic screening, able to read and write in the English or Korean language. | Referrals, snowball sampling | 10 interviews | 10 | National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MEST) (No. 2011–0014531) |

| Fu et al. 2017[34] | Breast reconstruction after surgical treatment for breast cancer | Explores values and perceptions that may impact breast reconstruction decisions | Immigrant East Asian women treated for breast cancer (no further criteria reported) | Purposive sampling | 35 interviews | 35 | None reported |

| Lee et al. 2016[32] | Breast cancer treatment | Understand the role of the family in breast cancer treatment decision making | Self-identified as Chinese, Cantonese, Chinese–American or Taiwanese, diagnosed with early stage breast cancer 3–12 months before study entry, had no recurrence | Not reported | 123 semi-structured interviews | 123 | None reported |

| Kim et al. 2015[17] | HPV vaccination decision making | Explore knowledge, perceptions, and decision-making about HPV vaccination | Aged 21–65 years, selfidentified as Korean female, no mammogram and/or Pap test within the last two years, able to read and write in either Korean or English, from the control group of the parent study | Sampling considered age, marital status, educational level, length of stay in the US, and English proficiency for a diverse sample | 2 focus groups | 12 | National Cancer Institute (R01 CA129060) |

| Leung et al. 2014[24] | Diabetes management | Explore reasons for difficulties in diabetes management, particularly obtaining, processing, and understanding health information, and communicating with others about needs and preferences | First generation Chinese immigrants living in Los Angeles County, aged 45 years or older, diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes for at least 1 year | Purposive sampling | 2 interviews, 6 focus groups | 29 | HKU Overseas Fellowship Award 2013–2014 from the University of Hong Kong (project number: 102009239), the HKU/China Medical Board Grants 2011/2012 from the University of Hong Kong and the USC Edward R. Roybal Institute on Aging at the University of Southern California |

| Lim et al. 2012[15] | Breast cancer survivorship | To explore the relationships between cultural health beliefs, acculturation, treatment-related decisions, the doctor-patient relationship, and health behaviors | Diagnosed with breast cancer, had survived for one to five years after diagnosis (cancer stage 0–III), cancer free at the time of study | Purposive sampling | 2 focus groups | 11 | None reported |

| Lee et al. 2012[18] | Breast cancer care | Describe the communication needs and challenges of Chinese and Korean American women with breast cancer | Chinese and Korean breast cancer patients (no further criteria reported) | Convenience sample, diverse sample sought with respect to patient age, education levels, survivorship, and treatment options | 9 interviews | 9 | National Institute of Health-National Cancer Institute’s Community Network Program Center, ACCHDC U54 CNPA (1U54CA 153513–01, PI: Grace X. Ma) |

| Killoran et al. 2006[19] | Breast cancer surgical treatment | Explore cultural factors that influence the selection of treatments and the presentation of treatment options by providers | For focus groups: First language either Cantonese or Mandarin or English, Chinese American, a diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer. For semi-structured interviews: Chinese American breast cancer patients and nonpatients. For ethnographic observations: Breast cancer patient. | Not reported | 4 focus groups, 51 interviews, 4 ethnographic observations | 69 | National Cancer Institute (grant R01 CA901422–01); seed grant from the Stony Brook University and by National Cancer Institute Grant (R01 CA100810–01) |

| Ashing-Giwa et al. 2004[20] | Cervical cancer survivorship | Examine health related quality of life among cervical cancer survivors | Cervical cancer survivors (no further criteria reported) | Not reported | 2 focus groups | 10 | California Cancer Research Program (#2110008) |

| Frank et al. 1998[16] | End of life decision making | Explore attitudes about advanced care directives and the use of life-sustaining technology for end of life | Case was selected as a typical case representing other Korean American respondents in the sample (no further criteria reported) | N/A (case study) | 1 case study | 1 | Agency for Health Care Policy Research (Grant No. R01HS0700101A1) |

| Leng et al. 2012[21] | Cancer survivorship (any cancer; mostly breast or liver cancer) | Explore the informational and psychosocial needs of Chinese cancer patients | Non-U.S. born, of Chinese descent, primary language not English, proficiency in Mandarin or Cantonese, age 21–80 years, diagnosis of cancer (any type) | Not reported | 4 focus groups | 28 | No specific funding |

| Simon et al. 2021[27] | Perceptions of local healthcare delivery | Explore experiences receiving medical care and interactions with healthcare providers | Self-identified as Chinese, spoke Cantonese or Mandarin, age 21 and older, resided in Chicago’s Chinatown | Convenience sample | 6 focus groups | 56 | National Institutes of Health under Grants R01CA163830, R34MH100393, and U54CA203000 |

| Wang et al. 2013[22] | Breast cancer survivorship | Elucidate the similarities and differences in communication with physicians between Chinese and NHW breast cancer survivors | Over 21 years old, diagnosed with stage 0-IIa breast cancer, completed primary treatment within the past 1–5 years, had no recurrence or other cancers. Patients who had physician contraindications, reported mental clearly communicate with field staff in Chinese or English not invited to participate. | Random selection of breast cancer cases from the Greater Bay Area Cancer Registry, Chinese women were oversampled as little is known about their cancer care experiences | 25 interviews, 4 focus groups | 44 | Lance Armstrong Foundation Young Investigator Award; National Cancer Institute (R21 Grant# CA139408); National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000040C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California |

| Chawla 2011[28] | Breast cancer survivorship | Examine the navigation of the breast cancer care process and the role of social capital in obtaining cancer resources | South Asian descent, 18 years of age and older, had a prior diagnosis of breast cancer, resided in California | Snowball sampling | 25 interviews | 25 | National Institutes of Health Research Supplements to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research (PA-05–015); UCLA Dissertation Year Fellowship Award |

| Kim et al. 2017[29] | Decision making about Pap test | Understand how individuals makes decisions about Pap tests concerning their personal values | Korean immigrant women 21–65 years of age, able to read and write in English or Korean, had not undergone a hysterectomy | Not reported | 32 interviews | 32 | National Cancer Institute (Grant/ Award Number: R01CA129060); Clinical Trials Registry (Grant/Award Number: NCT00857636); Sigma Theta Tau International; Fahs-Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation |

| Nguyen et al. 2008[25] | Communication about cancer care | Examine elements of cancer-related communication experiences of older Vietnamese immigrants | Vietnamese immigrants, aged 50–70 years, no personal history of cancer | Purposive sampling, equal number of males and females | 20 interviews | 20 | National Cancer Institute (Grant Number 5P50CA095856–04) |

| Ashing et al. 2003[30] | Breast cancer survivorship | Compare health-related quality of life and psychosocial impact of breast cancer, and understand the cultural and socio-ecological factors influencing this | Asian American breast cancer survivors (no further criteria reported) | Not reported | 4 focus groups | 34 | Department of Defense (17–99–1–9106) |

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants included in the meta-synthesis.

| Source | Ethnicity of Participants |

Participant Number & Gender |

Mean Age |

Immigrant status | Years in US | Education level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hesel et al. 2020[33] | Hmong | 10 males, 10 females | 41 | 6 US-born, 8 born in Laos, 2 Thailand, 4 missing | NR* | 4 less than high school, 3 high school diploma/GED, 6 college degree, 7 graduate degree |

| Chang et al. 2020[26] | Chinese | 22 males, 35 females | 71.5 | All born outside the US | NR | Interviews: 3 less than 8th grade, 4 some high school, 2 high school diploma/GED, 2 vocational school or some college, 4 bachelor’s degree and above Focus groups: 11 less than 8th grade, 6 some high school, 9 high school diploma/GED, 8 vocational school or some college, 8 bachelor’s degree and above |

| Bi et al. 2019[31] | Multiple Asian subgroups | 37 males, 3 females, 10 other | NR | NR | NR | 11 some college or 2-year degree, 28 college graduate, 7 more than college, 4 missing |

| Jun et al. 2018[23] | Korean | 0 males, 10 females | 37.6 | All born in Korea | Mean = 5.7, SD = 2.5; Range = 4–14 | All had a minimum of a bachelor’s degree |

| Fu et al. 2017[34] | Multiple Asian subgroups | 0 males, 35 females | 51 | All born outside the US | Mean = 27.4; Range = 3–40 | 1 some elementary school, 2 elementary school, 4 middle school, 12 high school, 1 vocational school, 9 BS or BA, 3 MS, 1 PhD, 2 unknown |

| Lee et al. 2016[32] | Chinese | 0 males, 123 females | 48.7 | NR | Median = 13.6 | 19 elementary or less, 40 high school, 64 college and above |

| Kim et al. 2015[17] | Korean | 0 males, 12 females | 44.8 | 11 born in Korea, 1 born in the US | Mean = 16; Range = 3–32 | 88.5% some college |

| Leung et al. 2014[24] | Chinese | 18 males, 11 females | 63.6 | All born outside the US | Mean = 15; Range = 6–39 | 4 Grade 6 or less, 13 Grade 7–12, 4 no degree, 8 degree |

| Lim et al. 2012[15] | Korean | 0 males, 11 females | 53.8 | NR | NR | 1 less than high school, 3 high school graduate, 7 more than high school |

| Lee et al. 2012[18] | Multiple Asian subgroups | 0 males, 9 females | 54 | NR | Mean = 18.6; Range = 7–35 | 2 high school or less, 7 college graduate or above |

| Killoran et al. 2006[19] | Chinese | 0 males, 69 females | 56 | Focus group: 30 born outside the US Patient interviews: 21 born outside the US Non-patient interviews: 21 born outside the US |

Focus group: Mean = 17.4 Patient interviews: Mean = 17.8 Non-patient interviews: Mean = 12.2 |

Focus group: 14 less than 9 years, 8 were 9–12 years, 10 were 13–16 years, 2 were 17–18 years Patient interviewees: 9 less than 9 years, 5 were 9–12 years, 12 were 13–16 years, 2 were 17–18 years Non-patient interviewees: 4 less than 9 years, 5 were 9–12 years, 11 were 13–16 years, 1 were 17–18 years, 2 missing |

| Ashing-Giwa et al. 2004[20] | Multiple Asian subgroups | 0 males, 51 females | 48 | NR | NR | NR |

| Frank et al. 1998[16] | Korean | 0 males, 1 females | 79 | Born outside the US | Mean = 12 | NR |

| Leng et al. 2012[21] | Chinese | 16 males, 12 females | 57 | All born outside the US | 0.5–1 year (1); 1–2 years (4); 3–5 years (2); 6–9 years (1); 10–15 years (4); 16–20 years (2); more than 20 years (13); 1 missing | 1 (3–5 grades), 9 (6–9 grades), 6 (10–12 grades), 11 (more than 12 grades), 1 missing |

| Simon et al. 2021[27] | Chinese | 0 males, 56 females | NR | All born outside the US | 0–5 years (10); 6–10 years (12); 11–15 years (11); 16–20 years (7); more than 20 years (15) | 15 less than high school, 22 school graduate, 7 college 1–3 years, 9 college graduate or higher |

| Wang et al. 2013[22] | Chinese | 0 males, 44 females | 57.7 | 37 born outside the US, 7 US-born | Mean = 22.22 | US born Chinese: 7 more than high school Immigrant Chinese: 19 less than or high school level, 18 more than high school |

| Chawla 2011[28] | South Asian | 0 males, 25 females | 55 | All born outside the US | Mean = 28 | 1 high school, 6 college graduate, 18 graduate school or higher |

| Kim et al. 2017[29] | Korean | 0 males, 32 females | 48.7 | All born outside the US | Mean = 16.4 | 14 were high school graduates or less, 18 some college |

| Nguyen et al. 2008[25] | Vietnamese | 10 males, 10 females | 64.5 | All born outside the US | Median immigration year = 1992 | US Education: 12 had no education in the US, 3 vocational or trade school, 1 some college, 4 ESL |

| Ashing et al. 2003[30] | Multiple Asian subgroups | 0 males, 34 females | 56 | NR | NR | NR |

NR = Not reported

3.3. Risk of bias

The total quality scores ranged from 7 to 9 (see Appendix Table 3). Majority of the studies (n = 17; 85%) did not address the influence of the researcher on the research and vice versa. In addition, for 10 studies (50%), there was a lack of clarity about the congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology.

3.4. Synthesis of results

We abstracted 275 unique initial codes from the 20 studies and grouped these into 18 subthemes (see Table 3 for supporting quotations). The 18 subthemes were grouped into 4 major themes.

Table 3.

Themes, subthemes, and supporting quotations.

| Theme, citations | Subthemes | Supporting Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Negotiating power and differing expectations in SDM | ||

| 17, 22, 30, 31, 20, 18, 32, 19, 28, 15, 29, 23, 27, 26 | Role preference for final decision | “Since mine was detected at the early stage, I asked my own family doctor for her opinion. My family doctor said I could decide for myself. With my own doctor having said that, along with the information I had collected about the sickness and my own understanding of it, I felt that I did not need to do it. If, however, my own doctor told me I should, I would have done it (had a mastectomy) (Chinese immigrant, age 52, high school, 3 years in US, $10–20,000)” (Wang et al. 2013[24], p. 3320) “Even if he gives me options, I won’t understand. That is, say if you present this treatment or that treatment, you won’t know what they mean. Even if you tell me about that, it won’t be helpful for me. The final decisions still rest on the doctors.” (Simon et al. 2021[29], p. 9) |

| 18, 25, 24, 19, 23, 26, 22, 30, 21, 15, 27, 17 | Patient expectations of provider | “If the doctor gives me a choice, then they must not be an expert”. “Given the great lengths that physicians in this study went to present the options as equivalent and to give adequate time to explain BCT, it is ironic that, one of the themes found in the patient’s interviews was that being given a choice indicated a lack of authority on the physician’s part. For example, sometimes the patient explicitly stated that because the doctor offered her a choice, this indicated that the doctor lacked expertise and authority, and that the physician themselves did not know which choice was ‘better’. When a doctor did not offer a choice, they were then viewed as real experts who knew ‘what the right thing to do’ was.” (Killoran et al., 2006[21], p. 980) “Overall, there was an acceptance of the paternalistic doctor–patient relationship, and a reliance on the health care system to tell patients what to do and when to do it. When providers failed to recommend age-appropriate screening, however, important preventive health measures were overlooked. For example, 1 woman received regular mammography because of her doctor’s recommendation, but reported that she had never been advised to screen for colon cancer.” (Nguyen et al. 2008[27], p. 48) |

| 23, 16 | Distress associated with decision-making | “In Excerpt 2, Mrs. Kim explains in greater detail why it is unwise for patients to know their diagnoses. Disclosing a diagnosis of cancer to patients causes them to suffer and leads them to think obsessively about dying. When Mrs. Kim reflects upon her own case, she believes it was better to avoid such suffering. [Interviewer]: If anyone in your family had cancer, do you think it would be good to tell the person about their disease? [Respondent]: Reflecting on my experience, if the patient were to know their disease, it would cause anguish. So I think it would be better not to inform the patient, and in that way the patient could pass away less fearfully. In the case of cancer, the patient cannot stop thinking about their own death: it is not good.” (Frank et al. 1998[18], p. 409) “In addition, participants described that they were perturbed by the counseling process, which required a relatively long amount of time and involved detailed analysis. They were asked to review their family trees, which, at first glance, felt like a nuisance and seemed irrelevant to childbearing. One woman admitted, ‘Sometimes, the more steps I went through, the more worried I became. The less I know the better.’” (Jun et al. 2018[25], p. 132) |

| 30, 17, 34, 18, 24, 16 | Role preference for shared decision-making process | “The women who had daughters aged around 11–12 years—and hence were recommended by pediatricians or their children’s school to have their daughters vaccinated—appeared to have followed the decision/recommendation made by the authorities (pediatrician or school). One mother whose daughter received HPV vaccine due to school entry policy stated, ”I would not have vaccinated my daughter, had there not had any vaccination policy implemented at her school.”” (Kim et al. 2015[19],p. 6) “The women in the mixed groups specifically felt that patients must be actively involved and educated about their treatments: ”Even if you are educated, if you don’t get involved, nothing will come out of it. When you are active, it doesn’t matter whether you are high school graduate or you have a PhD. (Mixed group survivor)” (Ashing et al. 2003[32], p. 49) |

| 29, 15, 19 | Decisional regret | “One woman mentioned that she regretted not making a decision in terms of surgery. KABCS tended to hesitate in decisions about breast cancer reconstruction surgery because of their image as mothers or wives rather than their image as women. Family members may need to communicate with patients and try to understand their emotions and choices. The doctor said to do reconstruction surgery… My son asked a doctor in Korea. But the doctor said that if it were his mother, he would not recommend it… So my son didn’t want me to do it. So I didn’t do it… Now, I have regrets that I didn’t make that decision.” (Lim et al. 2012[17], p. 395) “Others stated in the focus groups, with some regret, that the doctor made the choice of BCT for them, and they felt disempowered in the process. While this may to some extent have been a reflection of the group norm established for the ‘safety’ of a MRM, many of these women were also interviewed, and detailed the conflict in that context as well.” (Killoran et al., 2006[21], p. 979) |

| 30, 22, 24, 20, 26, 19, 31, 29 | Patient autonomy and assertiveness | “[Interviewer: Who made the decision?] Of course I did it. Yeah, I was in the center of it all. Of course, I got information from my friends and also the news media. When doctors gave me recommendations, I did not just follow them blindly. I did the research first. Through the research, I learned better about the test, understood why it is necessary, and convinced myself to take the examination. So I make my own decisions [Screener]"” (Kim et al. 2017[31], p. 689) "You know. I try to ask lots of questions. And, things that I don’t understand, I ask for explanations (US-born Chinese, age 59, bachelor’s degree, $50–60,000)” (Wang et al. 2013[24], p. 3319) |

| 19, 30, 25, 28, 26, 34, 22, 27 | Willingness of provider to engage in shared decision-making | “When I asked the doctor questions, he simply told me ‘it’s how it is.’ When I asked him again, he just said ‘it’s how it is.’ He simply kept answering, ‘it’s how it is.’” (Simon et al. 2021[29], p. 9) “Another woman interviewed as part of the study developed a relationship with her breast cancer surgeon and sought his advice for her main surgery and later regarding whether to have reconstructive surgery. In her case, her shared decision-making style was compatible with her surgeon’s style. In addition, he also accommodated this woman’s involvement of family members in her decision-making process, at the time of her diagnosis: “When he gave me the diagnosis, he told me I needed to do further testing and also gave me various options about the surgery. What options I had, whether I should have a mastectomy or lumpectomy. I had some questions, but mostly my family folks asked questions. Decision is, once all my tests were done, I had to make the decision for the surgery, which way I wanted to go. He gave me all the information and I made the decision after I came home. But, the final decision was mine. And I was comfortable with that. As described, this South Asian woman felt comfortable with the information given to her about her treatment options and the surgeon’s willingness to answer her questions, as well as those of her family members. She also describes the way this surgeon took additional time with her to make sure she felt comfortable with her treatment decision, in other portions of the interview.” (Chawla 2011[30], p. 113) |

| Theme 2: Cultural Influences on SDM | ||

| 30, 16, 32, 19, 33, 29 | Cultural beliefs and decision-making | “In the focus-group discussions, the majority of Cantonese and Mandarin-speaking women described their reasoning for selecting a [modified radical mastectomy] (MRM) over [breastconserving treatment] (MRM) as due to ‘safety reasons.’ When deciding between a MRM and BCT the belief was ‘health comes first, why care about aesthetics.’ The assumption was that any choice that included aesthetic concerns was inherently less safe. Since conserving the breast was interpreted to be an issue concerning one’s appearance, their logic was that something else, such as their chances for survival, would be lost in the equation.” (Killoran et al., 2006[21], p. 977) “In Korean culture, the mother is responsible for taking caring of the entire family, including the children. Therefore, a majority of women in this study thought that they should stay healthy in order to care for their families. One mother stated, ‘I’m a wife and a mother and I believe the happiness of my family depends on my health. So I feel the responsibility to stay healthy [Under screener]’" (Kim et al. 2017[31], p. 691) |

| 34, 19 | Group norms and decision-making | “The other, a ‘fourth-generation Chinese-American,’ complained about the comments she heard from the community during her treatment that she should have done a MRM.” (Killoran et al., 2006[21], p. 978) “[Interviewer]: If the patient were your relative, then what kind of decision are you supposed to make? [Respondent]: If the patient were my child, then I would ask them to use the treatment in order to see my child alive even one more day. [Interviewer]: If the patient were your parent? [Respondent]: If my parent were aged and in such condition, well. as I would behave toward my child, I also would ask the same thing. I shouldn’t let them die. I would try my best. [Interviewer]: If the patient were you, then what do you expect your children would decide for you? [Respondent]: If my children wanted to see me even one more day, then they might ask for the treatment. I am the one who is going to die; so I don’t control the situation. [Interviewer]: When you think about the decision right now, would you want the treatment in order for your life to be extended if you were not conscious and had almost no hope to live? [Respondent]: I would rather pass away sooner, if by having my life extended it caused pain. [Interviewer]: But for others, you would ask for the treatment to extend the life? [Respondent]: In other cases, if the patient were either my child or my husband, then I would request the treatment in order to see them even a little longer. [Interviewer]: Then isn’t that contradictory? [Respondent]: Although it’s a contradiction, it’s the right thing to do [tori]. Don’t you think so? Would any children let their mother die without trying to save her by any means?” (Frank et al. 1998[18], p. 411) |

| 27, 26, 22, 18, 30, 21, 19 | Patient makes accommodations for provider | The doctor’s time is very precious…[Previously], I would go to the doctor and then, Aiya! I forgot to ask him that question. So, the next time, I wrote down a list of things to ask him. Then, we discuss these things…I would change myself. You do not need to change the doctor (Chinese immigrant, age 48, high school, 28 years in US, $50–60,000)* . (Wang et al. 2013[24], p. 3319) “Some patients described strategies that they used to help them with their language barriers such as bringing native English speakers with them to the doctor’s office and preparing a diary of symptoms in English to show the doctor. They thought these were very helpful in improving her communication with the physician.” (Lee et al. 2012[20], p. 4) |

| 21, 30, 34, 19, 32, 27, 23, 22, 25, 18, 24 | Importance of language support for minority patients | “Many of our interviewees felt more comfortable with interpreter services, most commonly for Mandarin or Cantonese. Although these women expressed that they would be willing to see an English-speaking physician, many sought care from Chinese-speaking physicians. Patients expressed increased sense of ease, understanding, and familiarity with native language speakers. “Some doctors are always talking with me and saying with me in English, but at that moment I got cancer. I just want to say native language.”” (Fu et al. 2017[36], p. 365e) “Despite having limited confidence that they can improve patient–provider interactions because of their limited English proficiency, we found that some Chinese women still placed the responsibility of language barriers onto themselves. They [internalized] the blame for language barriers, stating: “you can’t blame the doctors. It is our poor English to blame.”” (Simon et al. 2021[29], p. 10) |

| 33, 21, 25, 28 | Patient preference for racial, cultural, or gender concordance | “In our culture, we are very private. Having an outsider come to our home is nerve-wracking." (Hesel et al. 2020[35], p. 72) “Some described a preference for Chinese doctors and dissatisfaction with their current doctors. One explained, “My family doctor is a foreigner [American] and I think it’s hard to talk to him. If I had a Chinese doctor as my primary care doctor, then that would be best.” Another said, “We don’t understand our doctors. They are foreigners [Americans]. We can’t understand what they say. They don’t talk to us. They just type on their computers.”” (Leng et al. 2012[23], p. 3225) |

| Theme 3: Important of Social Support in SDM | ||

| 32, 23, 29 | Family role in decision-making | “I have thought about reconstruction or implant, at least it would not be so flat, you know. He (spouse) said no (to the surgeon). At home, I asked him, why not, let’s just have it at one side. He said it would be too much for me. One surgery was enough. He stressed that since he didn’t care, I didn’t need to suffer more.” (Lee et al. 2016[34], p. 1497) “As one survivor articulates, her husband, her sister, and other friends helped her obtain a consensus about her course of treatment. Her use of physicians within her social network ultimately helped her feel comfortable with multiple decisions during her cancer care: So, they decided that the best course of action would be for me to get four treatments, four chemo treatments ahead of time, wait a month, have the surgery, and then have the remaining chemo treatments. My husband pulled all these studies and my sister is a pharmacist who, you know, went and talked to her friends that were working with hospitals and were real familiar with chemo treatments and whatnot. So, I mean, I was very, very comfortable with my decision. And I didn’t even think twice about it. This is what I wanted. My husband wanted it. My sisters, you know, really talked to a lot of people. And, you know, doctors they knew and everyone. You know, there was a consensus. For this survivor, having a consensus of opinions from people whom she trusted helped her to feel comfortable with her course of cancer treatment. Although not explicitly stated here, this survivor was also referring to her decision to have a mastectomy, which was particularly difficult for her, because she was 28 years old at the time of her diagnosis.” (Chawla 2011[30], p. 143) |

| 18, 32, 30, 23, 28 | Importance of support in decision-making | “Some patients had no other choice but to follow the doctor when making decisions because they “had no one to ask questions and had no time to collect the related information about how to deal with cancer” (A 55-year old Chinese woman).” (Lee et al. 2012[20], p. 5) “Many women expressed the need for support from family members, friends or other resources to seek second opinions, find specialists and manage the health care system. ‘I wish there would have had someone to help me find a good doctor at the beginning. a Chinese doctor said I didn’t need to take the whole breast away but he could not accept my insurance. So, we asked around and finally found another doctor, but he wanted to remove the whole breast. I did not know where to get another doctor again.”” (Lee et al. 2016[34], p. 1496) |

| 34, 32, 29, 28, 17, 23 | Community role in decision-making | “Some participants mentioned that their neighbors within the Korean community were primary sources for decision-making. For instance, friends from church would share their prior experiences or refer the participants to others who had undergone similar ordeals. In fact, two of the four participants who refused to take amniocentesis described that amniocentesis results in miscarriage, a belief widely held among the Korean community in the U.S.” (Jun et al. 2018[25], p. 131) “As described in the quote below, one survivor discusses the way that having physicians in her personal network helped her feel that she had enough information to make educated decisions during her cancer treatment: Interviewer: It sounds like you had several doctors within your own personal network, like your family members and friends. What effect do you think that had on your experience? Survivor: Very positive. Because that way you can confirm one opinion. It’s like your second and third and fourth opinion. So, before you make your decision, you feel like that, okay, you are educated enough. And then you made a decision rather than just randomly you make a decision. If there is available, as many opinion, I will take it. Then, I feel more comfortable to make my decision based on that rather than just believing in one person and just start following their thing. Especially, with this kind of thing, where there is side effect. The use of physicians within this survivor’s personal network helped her obtain informal ""second, third, and fourth"" opinions that ultimately made her feel that she made educated decisions during her cancer treatment.” (Chawla 2011[30], p. 143) |

| Theme 4: Supportive Factors for Facilitating SDM | ||

| 24, 27, 28, 30, 22, 26 | Coping with time constraints | “Time with the physician was an important issue for the women in the Chinese and mixed groups. Many felt that they were not provided enough time to talk with the doctor because the doctor was too busy. Further, some felt that they had to wait a long time just to see the doctor: “He is very, very good doctor, but too busy everyday with patients. So I wait, we saw him only few minutes. He has no time to talk to you, but I still trust him because I know he is a very good doctor.” (Mixed group survivor)” (Ashing et al. 2003[32], p. 48) “As a result, patients may need to initiate discussions for the physician to listen and respond to concerns. One interviewee advised, “Generally speaking, if you ask him, he will explain to you. He won’t take the initiative to tell you.”” (Chang et al. 2020[28], p. 3474) |

| 21, 18, 26, 22, 19, 30, 15, 25, 23, 34 | Importance of information or explanation for patient | “At the same time, the majority of interviewees desired information on side effects and welcomed more detailed medication counseling. However, they perceived physicians as too busy. One interviewee recalled, “I once asked [my doctor] and he said, ‘The time I could spend on each patient is limited. I do not have enough time to explain to you the medication details.’” (Chang et al. 2020[28], p. 3475) “Many participants expressed a need for guidance in making decisions about treatment options and felt unable to challenge their doctors: “When I started to see a doctor and the doctor told me that I have to go through an operation and do chemotherapy, I basically had no other option. I had to choose between going through it and not going through it. I think that everyone basically has experienced this struggle, but at the end of course we submit to the doctor’s authority and carry on with the procedure.for us and medical treatment, we are completely in an ignorant state, we only can follow the doctor.”” (Leng et al. 2012[23], p. 3224) |

| 26, 15, 17, 28, 22 | Importance of a good patient-provider relationship | “The doctor was very different from what I expected; I found that he took really good care of me during our interaction, so I gained a lot of confidence in him.I think doctors have to treat patients as humans.so when the doctors tell patients news, first is the mammogram, then ultrasound, and biopsy. During the process, I think that doctors need to be very patient, to guide the patients and not just say do this or that, or just tell them the results. For patients, their heart sank and they feel very worried (Chinese immigrant, age 58, some college, 33 years in US, $90,000)” (Wang et al. 2013[24], p. 3319) “A woman complained she did not obtain enough medical information because of an uncomfortable relationship with her doctor, the language barrier, and limited time. “I had a few consultation sessions with a doctor before surgery… It was a little regretful because I did not get any detailed information."” (Lim et al. 2012[17], p. 394) |

3.4.1. Theme 1: Negotiating power and differing expectations in SDM

Overall, 19 studies contributed data for Theme 1. Numerous patients shared that they were used to, or expected, a more paternalistic decision-making process with their provider [25,27]. Across 12 studies, patients overwhelmingly preferred following the provider’s recommendations for the final decision [17,19,20,22,24,25,26,28,29,30,31,32]. This stemmed from their perception of the provider as an authority figure and having trust in the provider’s expertise [17,20,25,28,30]. In general, patients had high expectations of the provider’s expertise; they expected to be given solutions instead of being asked questions. In fact, 2 patients shared that they would question the provider’s expertise if given a choice about breast cancer treatment, as opposed to being told what they should do [21]. Further, some were willing to ask for second opinions or switch providers if they were not satisfied with their providers’ expertise [20,24,26,27,28]. Another common reason for this preference was that patients felt they lacked the knowledge or skills to make the decision or to correct or second-guess the provider. They were not confident of making the right decision even if presented with options [26,29,30], and some found the responsibility of making the right decision distressing [25]. For instance, 1 patient felt it was “strange” for the provider to engage him in SDM for diabetes management and that it was impossible for him to know more than the provider [26]. Patients also described feeling overwhelmed by the level of involvement in the SDM process, with 1 patient saying “the less I know the better” [23,25].

Conversely, some patients felt it was important to take responsibility for the final decision [17], and did not want to simply follow the provider’s recommendation [19,24,31]. In 3 studies, patients felt that they should be actively involved in the SDM process, such as being educated about the disease and having their preferences noted and respected [18,20,32]. Such patients were assertive in terms of their willingness to challenge providers [24,33], refusing certain types of treatment [32], being proactive and involved in their health care, educating themselves on their disease or treatment, and taking the initiative to ask questions [22,28,32]. In the context of breast cancer treatment, some patients described having to argue with their providers to have their choices respected [21], and some patients expressed regret that they deferred their decision about breast cancer treatment instead of asserting their preference [17,21]. Others asserted their agency in indirect ways, such as getting second opinions [28,30], changing doctors [24,28], or through non-adherence to medication or their treatment plan [21,28]. It is noteworthy that wanting to be actively involved in the SDM process did not necessarily translate into wanting to make the final decision on their own. One patient reported that she liked that her provider told her what she needed to do but gave her options and information, a process she described as a shared decision [30].

Patients who wanted to be more involved in decision-making also described challenges in terms of their providers’ willingness to involve them in SDM. Participants reported that some providers disliked being questioned about treatment decisions [30] or got impatient or dismissive when the patient attempted to ask more questions [27,29]. However, patients also described positive experiences, such as providers taking the time to explain their diagnosis and options, answering questions from the patient and their family members, giving the patient enough time to make a decision, and communicating clearly and effectively [30].

3.4.2. Theme 2: Cultural influences on SDM

Overall, 15 studies contributed data for Theme 2. Majority of our findings were from 2 studies on breast cancer treatment decisions [21,34] and 2 studies on end-of-life decision-making [18,35].

We found that it was a cultural norm for family members to be involved in decision-making, with some patients deferring the final decision to family members, such as their husband or their children [17,20,34]. Many women based their treatment decision on the needs of the family and were more concerned about staying alive for their family and minimizing disruptions to family life [21,31,34]. Concerns such as personal preferences or body image were described as secondary to the needs of the family. For Asian breast cancer patients, it was more common for women to select the more aggressive modified radical mastectomy (MRM) treatment over breast-conserving treatment (BCT), even if it went against the provider’s recommendations [21,34]. One patient shared that she considered doing an MRM, even though her provider said that would not make sense as the tumour was in her armpit [21]. According to some patients, breasts are a function of a woman’s as a wife or mother, and reconstruction in older women is considered an unnecessary procedure and even inappropriate as it was for “purely cosmetic” reasons [36]. Hence, MRMs were widely perceived as the safer and a more thorough option, and more likely to keep the patient alive longer for her family. Group norms also influenced this decision and there appeared to be social pressure to conform to the MRM treatment option. For instance, 1 patient shared that her community made negative comments about her not getting an MRM [21].

In a study with Hmong patients, they described the importance of involving family members in all caregiving or end-of-life decisions, and that if the provider were to only involve the patient, this would be viewed as the provider “trying to turn the patient against their family” [35]. In some cases, decision-making was perceived to be the responsibility of children towards their parents. In a case study with a Korean female about end-of-life decisions, she shared that even though her private preference would be for her life to not be prolonged, there was a cultural expectation that her children should be responsible for making the decision and that they were expected to choose interventions to prolong her life to show filial piety [18].

Cultural norms also influenced how patients engaged with their providers in the SDM process. Patients often reported making accommodations for the provider to maintain a good patient-provider relationship. Majority of these codes came from 1 study on Chinese immigrant women’s healthcare experiences with clinics in Chicago’s Chinatown [29]. One patient explained, “I feel that Chinese culture teaches us to be more considerate for doctors. If he is busy, then I would find information by myself, or I would find other ways to solve the problem myself” [29]. Some patients also prioritized preserving harmony with their provider over their own care. For instance, some patients reported that they were unwilling to get second opinions, change providers, or ask for a referral as they wanted to preserve harmony and help the provider “save face” as these actions may imply that the provider was not competent enough [29]. Three women reported refraining from asking questions or seeking clarifications when they felt that their providers were too busy or not in a good mood, saving these for when the provider is not “vexed” [29].

Among patients who were not proficient in English, many described a lack of interpreters at their clinic [27,32,34]. Even when translators were provided, one patient shared that some did not take the time to fully or accurately translate everything the doctor said, resulting in misunderstandings of the diagnosis or treatment [21,25]. For instance, one study found that “a number of patients misinterpreted the translators’ use of the Chinese word ‘partial’ (surgery) when translating ‘lumpectomy’ to mean that their treatment would be incomplete” [21]. Many patients relied on English-speaking family members or friends to go with them to see the provider. Even so, many patients felt that the language barrier impeded them from engaging meaningfully in the SDM process, such as understanding what procedures will be done and why [20,23], to ask the provider questions [20,25,29], or to advocate for themselves [23]. As a result, the language barrier was a source of stress and some patients described a preference for culturally and linguistically concordant providers in stressful health situations.

3.4.3. Theme 3: Importance of social support in SDM

Overall, 8 studies contributed data for Theme 3. Asian patients highlighted the role of their family and community in supporting them through decision-making. As highlighted in Theme 2, family members played a central role in decision-making, with patients sometimes deferring to their spouses or children for the final decision. Many patients felt upset if their family members (e.g. spouse, children) were not able to be present during the consultation with the provider or in making the decision [25,34]. Some patients’ spouses or children helped them with making a decision [25,31,33], helped them search for information online [32,34], provided emotional support during decision-making [25,34], and asked the doctor questions during the visit [34]. Friends and other community members, including doctors in their social networks, also helped patients with deciding between options or with providing second opinions [20,30,34].

3.4.4. Theme 4: Supportive factors for facilitating SDM

Overall, 14 studies contributed data for Theme 4. Patients across 6 studies highlighted providers’ time constraints as impacting their care, and that they did not have the opportunity to ask questions or seek clarification or felt that their questions were not answered to their satisfaction [24,28,29,30,32]. Some patients also noted that their provider would answer questions if asked but would not take initiative to share information unless prompted [24,28]. Despite them highlighting time as a constraint, patients were respectful of the providers’ limited time. When asked what she would change about her communication with her provider, one patient stated “I would change myself” [24]. Some simply refrained from asking questions as they felt bad taking up more of the provider’s time [26,28], and others stated that they would find other ways to get information or solve the issue themselves [29], or wait for another opportunity to ask their questions [24]. Related, and frequently compounded by time constraints, was that patients felt that providers did not provide enough explanation or detail about the diagnosis or treatment plan, including providing information on treatment alternatives or potential side effects that could be expected [28,32]. One patient shared that she did not know much about her diagnosis or treatment [24], one did not know which screening test was run on him [27], one did not know the stage of the disease until after the treatment choice was made [21], and another reported that he did not know what medication was prescribed to him [26].

Another supportive factor for SDM was a good patient-provider relationship. Many participants valued providers who were empathetic, communicated well, showed patience in answering questions, and involved important family members in the discussion [30]. These led patients to report greater trust and confidence in the provider. Some patients attributed this relationship as the driving factor for following the provider’s recommendations, complying with the treatment, or choosing the provider again.

3.5. Additional findings

Four studies provided qualitative descriptions of differences based on participant characteristics [21,24,25,32]. In the context of breast cancer care experiences, 2 studies reported that more acculturated women tend to engage in SDM, emphasize the importance of patients seeking information and being educated about their disease, ask questions, compel providers to answer their questions to their satisfaction, and challenge providers [24,32]. In the context of prenatal genetic testing, the women that preferred an independent role in decision-making were working in health-related fields and were proficient in English [25]. Interestingly, in the study on breast cancer treatment, the authors observed that regardless of education and income level, Chinese women believed that BCTs were not as safe as MRMs [21]. However, women born in Mainland China were more likely to hold this belief compared to women born in Hong Kong [21].

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This review employed a meta-synthesis approach of qualitative studies to assess how Asian Americans negotiate involvement in SDM with their providers, the cultural influences on SDM among Asian Americans, and their perceived barriers and facilitators to SDM.

4.1.1. Understanding patient preferences surrounding SDM

Our review found that for Asian Americans, family and community members play a crucial role in providing them with emotional, social, and functional support during the decision-making process, and that patients often either made the final decision with or deferred the decision to close family members. Hence, it is essential that family members are engaged in the SDM process. In addition, many of the studies found that Asian women valued their role as a wife or mother, and often made decisions based on collective (family) rather than individual benefit. In addition, the sociocultural context in which decisions are made and how subjective norms (i.e. an individuals’ belief that important others think they should or not engage in a behaviour [37]) influence the decision-making process has not been extensively studied. We found that for breast cancer treatment decisions, there were social expectations that women should choose MRMs (perceived as safer) over BCTs (perceived as for aesthetic purposes). These findings highlight the gender and cultural norms and expectations that factor into decision-making among Asian patients and bring a deeper understanding of some of the personal preferences Asian patients have that providers should consider when engaging them in SDM.

4.1.2. Understanding how patients navigate SDM with providers

Majority of the studies included in this review found that Asian patients viewed providers as an authority figure and respected their expertise and recommendations, though there was variation in preferences for making the final decision. These findings are aligned with existing SDM models that acknowledge that it is important to understand patient preferences for how the final decision is made, and that some patients may defer the decision to their provider [38]. It is also important to acknowledge that involvement in the SDM process may be distressing or burdensome for some patients, and some may view the SDM process as inferior care or lacking competence from the provider. Regardless of their preferences for involvement in the final decision, most patients valued being involved in some way in the SDM process and a good relationship with their provider. Even among patients that were more comfortable deferring the final decision, the absence of an SDM process may led to the perception that they had “no choice” but to follow the provider’s decision. These findings have 3 important implications for SDM. First, current definitions and standards of a good SDM process need to be tested with other ethnic groups that may operate from a different cultural frame, to understand what they consider SDM and what constitutes a shared decision, as well as their expectations from the SDM process and their provider. Second, it highlights the importance of distinguishing between patient preferences for involvement in the SDM process and involvement in the final decision (i.e. a patient that does not want to be involved in the final decision may still want to be involved in the SDM process). SDM models already define these as separate SDM steps [38,39]; however, in practice, many studies tend to only measure preferences for involvement in the final decision (e.g. the Control Preferences Scale [40] and Autonomy Preference Index [41]) and less attention has been given to preferences for involvement in the SDM process. Third, the findings suggest that there is value in involving patients in the SDM process (e.g., regarding decisional conflict and regret) even if they preferred to defer the final decision to someone else.

4.1.3. Limitations

Our review had several limitations. First, we aggregated all Asian sub-groups as Asian Americans for this analysis. Asian Americans are highly diverse with over 20 sub-groups and there is likely to be cultural variation between the sub-groups [42]. In addition, Chinese and Koreans, major Asian American sub-groups, made up majority of the study populations. Although we observed similar themes across studies, we are cautious in generalizing our findings to Asian Americans in general. Second, there are also likely variations in findings based on participant characteristics such as acculturation and education level; however, there was not enough data to make meaningful inferences. Similarly, most studies in our meta-synthesis only included female participants. Thus, our analysis may not capture culturally-relevant gender differences in the SDM preferences of Asian Americans. Finally, as we conducted a qualitative meta-synthesis, the included studies had diverse research designs, health contexts, and study quality.

4.2. Conclusion

This review showed that Asian Americans are not a monolith and there was wide variability in the expectations that patients had of providers in the SDM process and their preferences for involvement in the SDM process and the final decision. Consistent themes that emerged were the need for cultural sensitivity in the SDM process, and the importance of family and community members in the decision-making process, highlighting the importance of engaging them in SDM. These findings also aligned with a previous systematic review examining SDM for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities in the US [43]. Future SDM research is needed to more fully understand the cultural influences on SDM among Asian American subgroups, in order to improve the quality of their care and medical decisions, facilitate SDM at the patient’s desired level, and move towards culturally sensitive decision aids that can facilitate SDM between the provider and patient.

4.3. Practice implications

The findings from this review have practical implications for health professionals who wish to engage Asian American patients in SDM across a variety of health contexts. Similar to patients from other racial and ethnic groups, Asian patients in this review valued good communication with their provider and time with the provider to ask questions, which were considered to be the building blocks of a good patient-provider relationship and helped patients feel more comfortable with the decision. In addition, we found that it is important for health professionals to elicit the patient’s desired level of involvement in the SDM process and separately, their desired level of involvement in the final decision, and cater the SDM process and final decision to the patients’ preferences. For instance, there were many patients in this review who wanted to be involved in the decision-making process but preferred their provider to make recommendations on the final decision or to defer the decision to their provider. A lack of understanding of their preferences may lead to the perception that they are receiving inferior quality of care, even if the provider is attempting to engage the patient in SDM. Health professionals should also consider who should be involved in SDM beyond the patient, as the patients in this review highlighted the importance of family and community input in decision-making. Finally, health professionals should consider the language needs of patients, as language was reported as a barrier to communicating with their provider and effectively engaging in SDM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (grant RP190210), and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (support grant funded from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute under award number P30CA016672, using the Shared Decision Making Core and Clinical Protocol and Data Management System). Dr. Lopez-Olivo’s work is supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA237619).

Funding information

This study was supported by the CPRTP at MD Anderson Cancer Center and the CPRIT Postdoctoral Fellowship in Cancer Prevention (RP 170259, Drs. Shine Chang and Sanjay Shete, principal investigators).

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Naomi Q. P. Tan: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Kristin G. Maki: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Maria A. Lopez-Olivo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Yimin Geng: Methodology, Data acquisition. Robert J. Volk: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.pec.2022.10.350.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The SHARE Approach: A model for shared decision-making - Fact Sheet. 〈https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/profe ssional-training/shared-decision/tools/factsheet.html〉. Published 2020, September. Accessed April 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Mak 2015;35:114–31. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tan NQP, Nishi SP, Lowenstein LM, et al. Impact of the shared decision-making process on lung cancer screening decisions. Cancer Med 2022;11:790–7. 10.1002/cam4.4445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hughes TM, Merath K, Chen Q, et al. Association of shared decision-making on patient-reported health outcomes and healthcare utilization. Am J Surg 2018;216:7–12. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T, O’Brien MA. Cultural influences on the physician–patient encounter: the case of shared treatment decision-making. Patient Educ Couns 2006;63:262–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Budiman A, Ruiz NG Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S. Pew Research Center. 〈https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/09/asian-americans-are-the-fastest-growing-racial-or-ethnic-group-in-the-u-s/.Published〉 2021, April 9. Accessed April 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Alden DL, Friend J, Schapira M, Stiggelbout A. Cultural targeting and tailoring of shared decision making technology: a theoretical framework for improving the effectiveness of patient decision aids in culturally diverse groups. Soc Sci Med 2014;105:1–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Alden DL, Friend J, Lee PY, et al. Who decides: me or we? Family involvement in medical decision making in eastern and western countries. Med Decis Mak 2018;38:14–25. 10.1177/0272989X17715628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].McLaughlin LA, Braun KL. Asian and Pacific Islander cultural values: considerations for health care decision making. Health Soc Work 1998;23:116–26. 10.1093/hsw/23.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Corrigan PW, Lee E-J. Family-centered decision making for east asian adults with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2021;72:114–6. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gilbar R, Miola J. One size fits all? On patient autonomy, medical decision-making, and the impact of culture. Med Law Rev 2015;23:375–99. 10.1093/medlaw/fwu032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Budiman A, Ruiz NG Key facts about Asian Americans, a diverse and growing population. Pew Research Center. 〈https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-americans/Published〉 2021, April 29. Accessed April 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee S, Martinez G, Ma GX, Hsu CE, Robinson ES, Bawa J, et al. Barriers to health care access in 13 Asian American communities. Am J Health Behav 2010;34(1):21–30. 10.5993/AJHB.34.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:1–8. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021;88:105918. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. JBI Evid Implement 2015;13:179–87. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lim J-W, Baik OM, Ashing-Giwa KT. Cultural health beliefs and health behaviors in Asian American breast cancer survivors: a mixed-methods approach. Oncol Nurs Forum 2012;39:388–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Frank G, Blackhall LJ, Michel V, Murphy ST, Azen SP, Park K. A discourse of relationships in bioethics: patient autonomy and end-of-life decision making among elderly Korean Americans. Med Anthropol Q 1998;12:403–23. 10.1525/maq.1998.12.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kim K, Kim B, Choi E, Song Y, Han H-R. Knowledge, perceptions, and decision making about human papillomavirus vaccination among Korean American women: a focus group study. Women’S Health Issues 2015;25:112–9. 10.1016/j.whi.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lee S, Chen L, Ma GX, Fang CY. What is lacking in patient-physician communication: perspectives from Asian American breast cancer patients and oncologists. J Behav Health 2012:1. 10.5455/jbh.20120403024919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Killoran M, Moyer A. Surgical treatment preferences in Chinese-American women with early-stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2006;15:969–84. 10.1002/pon.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ashing-Giwa KT, Kagawa-Singer M, Padilla GV, et al. The impact of cervical cancer and dysplasia: a qualitative, multiethnic study. Psycho-Oncology 2004;13:709–28. 10.1002/pon.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Leng J, Lee T, Sarpel U, et al. Identifying the informational and psychosocial needs of Chinese immigrant cancer patients: a focus group study. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:3221–9. 10.1007/s00520-012-1464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang JH-y Adams IF, Pasick RJ, et al. Perceptions, expectations, and attitudes about communication with physicians among Chinese American and non-Hispanic white women with early stage breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:3315–25. 10.1007/s00520-013-1902-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jun M, Thongpriwan V, Choi J, Choi KS, Anderson G. Decision-making about prenatal genetic testing among pregnant Korean-American women. Midwifery 2018;56:128–34. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Leung AYM, Bo A, Hsiao H-Y, Wang SS, Chi I. Health literacy issues in the care of Chinese American immigrants with diabetes: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005294. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nguyen GT, Barg FK, Armstrong K, Holmes JH, Hornik RC. Cancer and communication in the health care setting: experiences of older Vietnamese immigrants, a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:45–50. 10.1007/s11606-007-0455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chang E, Lin V, Goh R, et al. Differences between current and desired physician hypertension management roles among chinese american seniors: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:3471–7. 10.1007/s11606-020-06012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Simon MA, Tom LS, Taylor S, Leung I, Vicencio D. ‘There’s nothing you can do… it’s like that in Chinatown’: Chinese immigrant women’s perceptions of experiences in Chicago Chinatown healthcare settings. Ethn Health 2021;26: 893–910. 10.1080/13557858.2019.1573973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chawla N. South asian women with breast cancer: navigating cancer care and the role of social capital in obtaining cancer resources [Dissertation]. Los Angeles: University of California,; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kim K, Kim S, Gallo JJ, Nolan MT, Han HR. Decision making about Pap test use among Korean immigrant women: a qualitative study. Health Expect 2017;20:685–95. 10.1111/hex.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tam Ashing K, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kagawa-Singer M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psycho-Oncology 2003;12:38–58. 10.1002/pon.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bi S, Gunter KE, Lopez FY, et al. Improving shared decision making for Asian American Pacific islander sexual and gender minorities. Med Care 2019;57:937–44. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lee SKC, Knobf MT. Family involvement for breast cancer decision making among Chinese–American women. Psycho-Oncology 2016;25:1493–9. 10.1002/pon.3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Helsel D, Thao KS, Whitney R. Their last breath: death and dying in a Hmong American community. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2020;22:68–74. 10.1097/Njh.0000000000000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fu R, Chang MM, Chen M, Rohde CH. A qualitative study of breast reconstruction decision-making among Asian immigrant women living in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;139:360e–368ee. 10.1097/Prs.0000000000002947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ajzen I. The social psychology of decision making. Soc Psychol: Handb Basic Princ 1996:297–325. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC. Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98(10):1172–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27 (10):1361–7. 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The control preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res Arch 1997;29(3):21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, Moskowitz MA. Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy. J Gen Intern Med 1989;4(1):23–30. 10.1007/BF02596485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yom S, Lor M. Advancing health disparities research: the need to include Asian American subgroup populations. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2021. 10.1007/s40615-021-01164-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Mead EL, Doorenbos AZ, Javid SH, Haozous EA, Alvord LA, Flum DR, et al. Shared decision-making for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2013;103(12):e15–29. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.