Abstract

Background

The tobacco epidemic is one of the biggest threats to public health globally. This study evaluates the prevalence of smoking among Iranian university students.

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted in international databases (Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed) and domestic databases (Magiran, SID, Irandoc). Cross-sectional studies in Farsi and English from 2012 to 2023 were included. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale was used to assess the quality of the articles. Heterogeneity was examined using Cochran’s test and the I2 index. Due to high heterogeneity, a random effects model was employed to estimate smoking prevalence, and a funnel plot was used to assess publication bias.

Results

Out of 840 articles identified through the search, 149 records were removed as duplicates. Of the remaining 691 records screened for relevancy to the review question, 635 were excluded. Fifty-six reports were sought for full-text retrieval, and 54 full-text articles were successfully retrieved. However, 11 reports were excluded due to invalid data or insufficient information. Ultimately, 43 studies reporting the prevalence of smoking or the number of smokers in general, by gender, were included in the analysis. Specifically, 28 studies were included for males, 23 for females, and 43 for overall conditions. The overall prevalence of smoking was estimated to be 16% for both sexes combined, 26% for males, and 7% for females.

Conclusions

The prevalence of smoking among male and female students is high. Due to the high heterogeneity of the studies, the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution.

Trial registration

The study is registered in Prospero with the code CRD42021240264.

Keywords: Prevalence, Smoking, Students, Iran, Tobacco, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

The tobacco epidemic is one of the biggest public health threats the world has ever faced, killing more than 8 million people worldwide every year. More than 7 million of these deaths are caused by direct tobacco consumption, while about 1.3 million people die due to exposure to secondhand smoke. In 2020, 36.7% of men, 7.8% of women, and overall 22.3% of the world's population used tobacco. Smoking is the most common form of tobacco use worldwide. There are 1.3 billion cigarette smokers, about 80% of whom live in low- and middle-income countries [1]. Smoking causes 480,000 deaths in the United States each year (one in five deaths). Smoking damages almost all organs of the body and can cause cancer anywhere in the body (lungs, larynx, blood, bladder, etc.). Estimates show that smokers are more likely to have heart disease (2 to 4 times), stroke (2 to 4 times), lung cancer in men (25 times), and lung cancer in women (25.7 times) than non-smokers. Additionally, the risk of diabetes in active smokers is 30–40% higher than in non-smokers [2]. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) kill 41 million people annually, accounting for 74% of all deaths worldwide. To address this issue, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed the Package of Essential Noncommunicable (WHO-PEN) Disease Interventions for the control and prevention of cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, cancers, and diabetes. It also aims to reduce the four key risk factors: smoking, physical inactivity, improper nutrition, and alcohol consumption [3]. In Iran, to localize this intervention package and implement the WHO's recommendations, the Iran Package of Essential Noncommunicable (IraPEN) Disease Interventions program has been designed and integrated into the primary care program in health centers and bases since 2015 [4].

In recent years, the prevalence of smoking in Iran has increased, especially among young people and females, and the smoking age has decreased [5]. Upon entering the university, students may face various issues such as being away from their families, meeting new friends with different cultures, and mental challenges such as achieving success in doing multiple assignments, which can cause mental disorders such as depression and a tendency to use addictive substances [6].

Several studies in Iran have reported the prevalence of smoking among students, including the study by Panahi et al. (Tehran in 2018) with a rate of 23.8% [7], Mehri et al. in Kashan (2023) with a rate of 9.4 percent [8], Ghafari et al. in Tabriz (2022) with a rate of 6.6 percent [9], Moghadam Tabrizi et al. in Urumieh and Khoi (2022) with a rate of 17 percent [10], Zarei et al. in province East Azerbaijan (2023) with a rate of 17.4% [11] and the meta-analysis by Hagdoost and Mooszadeh in 2013, which reported the rate of smoking among male and female students was 19.8% (95%CI: 17.7–21.9) and 2.2% (95%CI: 1.4–3.02), respectively [12]. Considering that this systematic review and meta-analysis aim to provide reliable evidence for policymakers to evaluate the effectiveness of prevention programs, as smoking poses a significant challenge for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and the beginning of drug addiction and high-risk behaviors [13], we therefore relied on the results of studies that estimated the prevalence of smoking among students combined from the beginning of 2012 to the end of 2023 and compared it with the study by Moosazadeh and Haghdoost published in 2013.

Methods

The present study is a systematic review and meta-analysis that examines the amount of smoking among students. The report of this study is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [14]. This study is registered in PROSPERO with the code CRD42021240264.

Eligibility criteria

Cross-sectional studies in English or Farsi that investigated the prevalence of smoking in Iranian university students were included in the meta-analysis. Articles that were presented as posters at conferences and whose full text was not available were excluded from the study.

Search strategy

In this research, all articles were published, whose purpose was to determine the prevalence of smoking among Iranian students, from the beginning of 2012 to the end of 2023, in the international databases PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and domestic databases Magiran, SID, Irandoc. Based on the PICO formula, students were considered as a population and smoking as an outcome to retrieve and screen related studies. The keywords Smoking, Tobacco, Cigarette, Cigar, Students, and Iran were used to search for English articles, and the Persian equivalent of these keywords were used to search for Persian articles. The search syntax in international databases was as follows:

PubMed:

((("Tobacco Smoking"[Mesh] OR "Smokers"[Mesh] OR "Tobacco Use"[Mesh]) OR (Tobacco Smoking[Title/Abstract] OR cigarette[Title/Abstract] OR nicotine[Title/Abstract])) AND (student[Title/Abstract] OR school[Title/Abstract] OR university[Title/Abstract] OR college[Title/Abstract])) AND (Iran[Title/Abstract] OR Iranian[Title/Abstract])

Selection process

First, articles with titles and abstracts related to the study topic were selected. Then, following the inclusion criteria, the full text of the articles was independently reviewed by two researchers (AA and FH). If both researchers rejected an article, the reason was documented. In cases of disagreement, the article was reviewed by a third researcher (RN). The data from the studies were extracted independently by two researchers (AA and FH). These data included the name of the first author, the year of publication, the location of the study, sample size, prevalence, and the number of smokers in general and by gender.

Study risk of bias assessment

Newcastle–Ottawa scale was used to check the quality of articles [15]; This scale includes three parts: selection, comparability, and outcome, and the maximum score that can be obtained from each section is 5, 2, and 3, respectively. As a result, the maximum score that a cross-sectional study can get from this tool is 10.

Synthesis methods

To check the heterogeneity between studies, Cochran's test and I2 index were used (I2 index is less than 25% of low heterogeneity, between 25 and 75% of moderate heterogeneity, and more than 75% of high heterogeneity). Due to the high heterogeneity of the included studies, with a 95% confidence interval (CI), the random effect model was used to estimate the prevalence of smoking in general and separately in females and males. Data analysis was done using Jamovi software version 2.3.

Publication bias assessment

A funnel plot diagram was used to check the diffusion curve.

Results

Study selection

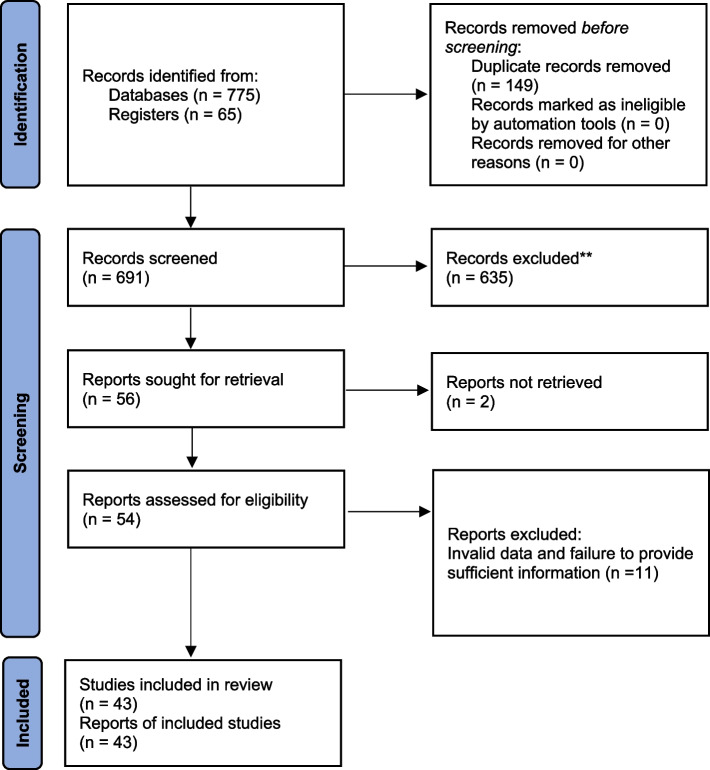

By searching selected international and domestic databases, a total of 840 articles were found (775 studies from international databases and 65 studies from national data sources). After removing duplicates, 691 articles entered the title and abstract review stage. A total of 635 articles unrelated to the topic of the present study were removed, and the full text of 56 articles was sought for retrieval. Two articles were excluded due to being inaccessible in full text. From the 54 articles assessed for eligibility, 11 articles were excluded due to invalid data and failure to provide sufficient information. Finally, studies that reported the prevalence of smoking or the number of smokers in general, either for both sexes or by gender, were included in the research. Consequently, 28 studies were included to report the prevalence of smoking among males, 23 studies for females, and 43 studies overall were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A PRISMA diagram illustrating the stages of identification, screening, and selection of studies on the prevalence of cigarette smoking among Iranian university students

Risk of bias in studies

The quality score of each study according to Newcastle–Ottawa is given in Table 1. The lowest and highest scores in the reviewed studies were 2 and 7, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics and important findings of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Name of the authors (year) | Place of study | Sample size | Overall prevalence of smoking (%) | Prevalence of smoking by gender (%) | Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment tool score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||||||

| 1 | Jalilian et al. (2016) [1] | Kermanshah | 601 | 11.6 | NR | NR | 6 |

| 2 | Vakilian et al. (2019) [2] | Shahroud | 1500 | 20 | NR | NR | 5 |

| 3 | Narimani et al. (2020) [3] | Ardabil | 215 | 37.2 | 44.8 | 26.7 | 6 |

| 4 | Kaveh et al. (2019) [4] | Shiraz | 462 | 11.7 | 8.5 | 3.2 | 6 |

| 5 | Maghsoudi et al. (2016) [5] | Larestan | 390 | 16.44 | 20.75 | 11.32 | 4 |

| 6 | Safiri et al. (2016) [6] | Tabriz | 1730 | 12.4 | 20.7 | 6.7 | 7 |

| 7 | Mansouri et al. (2020) [7] | 28 provinces in the Islamic Republic of Iran | 82,806 | 6 | 6.6 | 5.6 | 5 |

| 8 | Parami et al. (2020) [8] | Hamadan | 1258 | 15.4 | NR | NR | 4 |

| 9 | Shojaa et al. (2014) [9] | Gorgan | 538 | 6.1 | NR | NR | 4 |

| 10 | Amiri et al. (2021) [10] | Shahroud | 500 | 18.4 | NR | NR | 6 |

| 11 | Sahebihagh et al. (2017) [11] | Qazvin | 521 | 8.6 | 20.7 | 3.1 | 5 |

| 12 | Miri-Moghaddam et al. (2019) [12] | Zahedan | 500 | 15.2 | 26.5 | 8.7 | 6 |

| 13 | Keshavarz et al. (2013) [16] | NR | 325 | 10.8 | NR | NR | 6 |

| 14 | Allahverdipour et al. (2015) [13] | Tabriz | 1837 | 15.8 | 28.5 | 7.1 | 5 |

| 15 | Heydari et al. (2013) [14] | Tehran | 1271 | 31.1 | 31.1 | NR | 6 |

| 16 | Kabir et al. (2016) [15] | Karaj | 1959 | 9.3 | NR | NR | 6 |

| 17 | Taheri et al. (2014) [17] | Mashhad | 936 | 9.8 | 17.6 | 4.2 | 6 |

| 18 | Shekari et al. (2020) [18] | Tabriz | 3649 | 18.5 | 36.4 | 7.6 | 6 |

| 19 | Ghodousi et al. (2013) [19] | Isfahan | 537 | 18.7 | NR | NR | 4 |

| 20 | Nazemi et al. (2012) [20] | Shahroud | 1800 | 21.6 | NR | NR | 2 |

| 21 | Attari et al. (2015) [21] | Isfahan | 305 | 4.6 | 12.5 | 1.4 | 4 |

| 22 | Panahi et al. (2017) [22] | Tehran | 340 | 23.8 | 33.8 | 17.1 | 5 |

| 23 | Bashirian et al. (2011) [23] | Hamadan | 700 | 7 | NR | NR | 5 |

| 24 | Mokhtari et al. (2011) [24] | Guilan | 222 | 23 | 23 | NR | 5 |

| 25 | Tavakolizadeh et al. (2012) [25] | Gonabad | 279 | 9.8 | 14.4 | 4.1 | 3 |

| 26 | Ghodsi et al. (2012) [26] | Guilan | 222 | 23 | 23 | NR | 6 |

| 27 | Araban et al. (2015) [27] | Ahvaz | 170 | 14.1 | 36 | 3.5 | 7 |

| 28 | Rahimzadeh et al. (2016) [28] | Kurdistan | 288 | 17.36 | 25 | 11.25 | 4 |

| 29 | Shafiie et al. (2013) [29] | Bam | 760 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 1.4 | 5 |

| 30 | Shamsipour et al. (2012) [30] | Tabriz | 539 | 8.9 | 18 | 1.4 | 3 |

| 31 | Jafari et al. (2012) [31] | Kaleybar | 285 | 13.68 | 13.68 | NR | 6 |

| 32 | Mehdizadeh Noudehi et al. (2014) [32] | Tehran | 205 | 44.1 | 85.6 | 14.4 | 3 |

| 33 | Ghavami et al. (2014) [33] | Shahroud | 743 | 23 | NR | NR | 4 |

| 34 | Tarrahi et al. (2017) [34] | Khorramabad | 1131 | 3.7 | 7.3 | 1.6 | 6 |

| 35 | Halvaiepour et al. (2021) [35] | Isfahan | 450 | 20.2 | 28.4 | 13.2 | 7 |

| 36 | RezaKhani Mogaddam et al. (2013) [36] | Tehran | 720 | 22 | 35.6 | 9.1 | 4 |

| 37 | Mehri et al. (2023) [37] | Kashan | 681 | 9.4 | 16.7 | 3.35 | 7 |

| 38 | Ghaffari et al. (2022) [38] | Tabriz | 542 | 6.6 | 13 | 1.6 | 6 |

| 39 | Sadighpour et al. (2022) [39] | Tabriz | 500 | 18.88 | 35.81 | 4.12 | 6 |

| 40 | Moghaddam Tabrizi et al. (2023) [40] | Urmia/khoy | 450 | 17 | 29.2 | 6.8 | 3 |

| 41 | Zarei et al. (2023) [41] | East Azerbaijan Province | 334 | 17.4 | 30 | 7 | 6 |

| 42 | Shekari et al. (2022) [42] | Tabriz | 3666 | 15.7 | 26.6 | 2.2 | 5 |

| 43 | Adham et al. (2022) [43] | Ilam | 1894 | NR | 22.3 | NR | 6 |

Results of individual studies

A total of 43 selected studies have contributed 118,260 samples. The smallest sample size (170 people) was related to Araban et al.'s study and the largest sample size (82,806 people) was related to Mansouri et al.'s study. The highest and lowest percentages of smoking prevalence among males were 85.6% and 4.3%, and 26.7% and 1.4% for females. The characteristics of the selected studies are given in Table 1.

Results of syntheses

Table 2 showed a significant difference (p < 0.001) between the results of the studies and in other words, high heterogeneity of the studies.

Table 2.

Results of a meta analysis on the prevalence of cigarette smoking among Iranian students, stratified by gender, along with an assessment of study heterogeneity

| Tau | Tau2 | I2 | H2 | df | Q | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male and female | 0.079 | 0.0063 (SE = 0.0014) | 98.86% | 87.535 | 42.000 | 3002.845 | < .001 |

| Male | 0.106 | 0.0112 (SE = 0.0033) | 96.44% | 28.071 | 27.000 | 586.211 | < .001 |

| Female | 0.037 | 0.0014 (SE = 5e-04) | 92.91% | 14.106 | 22.000 | 226.022 | < .001 |

Tau2 Estimator: Restricted Maximum-Likelihood

Pooling the results of the studies using the random effect model indicates that the overall prevalence of smoking is approximately 16%, with 26% in males and 7% in females. For detailed 95% confidence intervals for these point estimates, please refer to Table 3. The corresponding Forest Plots can be found in Figs. 2, 3, and 4.

Table 3.

Results of the random effects model for estimating the prevalence of cigarette smoking among Iranian students by gender

| Estimate | Se | Z | p | CI Lower Bound | CI Upper Bound | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (Male and female) (k = 43) | 0.158 | 0.0123 | 12.8 | < .001 | 0.134 | 0.183 |

| Male(k = 28) | 0.259 | 0.0207 | 12.5 | < .001 | 0.218 | 0.299 |

| Female(k = 23) | 0.0658 | 0.00845 | 7.78 | < .001 | 0.049 | 0.082 |

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of smoking prevalence among Iranian students

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of smoking prevalence in Iranian male students

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of smoking prevalence in Iranian female students

Reporting bias

The publication bias was checked with a funnel plot (Fig. 5). Furthermore, Egger's regression test was used to assess funnel plot asymmetry, which its significancy can indicate publication bias in meta-analyses. The results of regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was Z = 5.039 and P < 0.001.

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the prevalence of smoking among Iranian students. The results of our study showed that 26% of male students, 7% of female students, and overall 16% of students smoked cigarettes. Smoking is more common among male students than female students. Males tend to smoke more than females, and males who experiment with smoking are far more likely to become regular smokers than females who experiment with smoking. This is because smoking by females is often considered an anti-social behavior and, in Islamic countries like Iran, it can be seen as a social disgrace [7]. However, the remarkable point of our study is that the amount of smoking among males and especially female students has increased significantly compared to the study by Haghdoost and Moosazadeh. Consequently, it appears that smoking among females has become more culturally accepted in Iranian society, potentially contributing to the foundation of an unhealthy community.

Smoking among Iranian students is 16%, which is considered a high rate. A systematic review and meta-analysis in Ethiopia conducted by Leshargie et al. in 2019 found similar results, with a smoking rate of 17.35% (95% CI: 13.21–21.49) [44]. The study by Guracho et al., conducted as a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2020 in Ethiopia, showed that the smoking rate among students in this country is 12.55% (95% CI: 10.39–14.72), which is lower than the rate of smoking among Iranian students [45].

A study conducted by Alotaibi et al. in 2019 found that the rate of smoking among Saudi students is similar to that of Iranian students. The smoking rate among male students in Saudi Arabia is 26% (95% CI: 24–29%) and 5% (95% CI: 3–7%) among female students. Comparing these results with the present study shows that Iranian male students have similar smoking rates to their Saudi counterparts, but Iranian female students smoke more than their Saudi counterparts (7% vs. 5%) [46]. This difference between countries can be attributed to various factors, including cultural, economic, and social factors, infrastructures, and strategies considered by countries to reduce smoking among students.

A study conducted by Nasser et al. in 2020 investigated the prevalence of smoking among students in 12 Arab countries. The highest rates of smoking were in Libya (80.2%), Jordan (80%), and Saudi Arabia (70.7%), while the lowest rates were in Yemen (7.4%) and the United Arab Emirates (9.4%). The comparison of these meta-analysis results with the current study shows that, except for Yemen and the United Arab Emirates, the rest of the Arab countries examined have much higher smoking rates than Iran (80.2%, 80%, 70.7% vs. 16%) [47].

Brazil and the Netherlands have successfully reduced tobacco use through the implementation of the Monitor, Protect, Offer, Warn, Enforce, Raise (MPOWER) tobacco control measures. Since 2010, Brazil has seen a relative 35% reduction in tobacco use, and the Netherlands is on the verge of achieving a 30% reduction target [48]. Similarly, Ireland has reduced smoking rates from 27% in 2004 to 18% in 2023 [49]. The measures taken by these countries include reducing cigarette advertising and promotion, increasing cigarette taxes, limiting the use of cigarettes in public places [50], providing smoking cessation services, prohibiting cigarette sales to minors, educating students about the types and effects of cigarettes, and scrutinizing the advertising techniques of tobacco companies [51]. Although Iran joined the FCTC1 in 2005 and has developed a national tobacco control program based on the six MPOWER criteria [52], this study shows an increase in smoking among students. Therefore, to effectively control smoking among students, stronger policies are needed to address the challenges of program failure.

The I2 value indicates significant heterogeneity among the included studies, necessitating further investigation into these differences. To address this high heterogeneity, a random-effects model was employed in this meta-analysis. This model assumes varying effects across different studies and applies distinct weightings to each study to compute the final result. Consequently, the results derived from this model are generally more valid under conditions of heterogeneity.

A funnel plot was utilized to assess publication bias. If the funnel plot is symmetrical, it suggests the absence of significant publication bias. While it seems to be symmetric, there are outliers’ results that could represent studies with unusual results, which might impact the overall findings.

One of the strengths of the current study is the review of non-electronic and unpublished sources and their inclusion in the meta-analysis. The limitations of this study include the high heterogeneity of the included studies, different definitions of cigarette smoking, and data collection by self-report method.

Conclusions

The findings of this study showed that 26% of male and 7% of female Iranian students smoke cigarettes. The comparison of the present study with the study conducted by Haghdoost and Moosazadeh shows that the amount of smoking among males and especially females has increased significantly. This suggests that current policies to reduce smoking among males have not been effective, and females tend to smoke more than before. Therefore, making students aware of the dangers of smoking and addressing the reasons why students smoke should be considered. Given the crucial role of females as future mothers, the health issues caused by smoking, and the significant financial burden it places on societies, inter-sectoral cooperation is essential to develop and implement effective policies.

Other information

Registration and protocol: The study is registered in Prospero with the code CRD42021240264. No protocol has been prepared.

Acknowledgements

All those involved in this study are writers of this manuscript

Abbreviations

- NCDs

Non-communicable diseases

- IraPEN

Iran’s package of essential noncommunicable diseases

Authors’ contributions

RN, AA, and FH designed the study. RN, AA, FH, and FS performed the literature search. AA, FH, and FS extracted the data. meta-analysis was conducted by RN. FS drafted the paper. Finally, all authors read, commented on, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was founded by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. (Grant Number: 47838).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Reza Negarandeh], upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Organizational Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1399.052).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jalilian F, Joulaei H, Mirzaei-Alavijeh M, Samannezhad B, Berimvandi P, Matin BK, et al. Cognitive factors related to cigarettes smoking among college students: An application of theory of planned. Soc Sci (Pakistan). 2016;11(7):1189–93. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vakilian K, Keramat A, Mousavi SA, Chaman R. Experience assessment of tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, and substance use among Shahroud university students by crosswise model estimation –The alarm to families. Open Public Health J. 2019;12(1):33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narimani S, Khezeli M, Babaei N, Rezapour S, Habibi M, Rohallahzadeh FZ. Risk-taking behaviors among students of Ardabil university of medical sciences, Iran. Iran J Psychiatr Behav Sci. 2021;14(4):e104784.

- 4.Jafari A, Keshavarzi S, Momenabadi V, Taheri M, Dehbozorgi F, Motazedian T-A. Evaluation of explanation of the BASNEF model on smoking waterpipe among the students one of the medical universities located in the south of Iran. Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. 2020;7(4):312–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maghsoudi A, Jalali M, Neydavoodi M, Rastad H, Hatami I, Dehghan A. Estimating the prevalence of high-risk behaviors using network scale-up method in university students of Larestan in 2014. J Substance Use. 2017;22(2):145–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safiri S, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Yunesian M, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Shamsipour M, Mansournia MA, et al. Subgrouping of risky behaviors among Iranian college students: a latent class analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treatment. 2016;12:1809–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Mansouri M, Sadeghi O, Roshanfekr P, Sharifi F, Varmaghani M, Yaghubi H, et al. Prevalence of smoking and its association with health-related behaviours among Iranian university students: a large-scale study. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(10):1251–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharareh P, Leili T, Abbas M, Jalal P, Ali G. Determining correlates of the average number of cigarette smoking among college students using count regression models. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shojaa M, Qhorbani M, Jouybari LM, Sanagoo A, Mohebi R, Bamyar R, et al. Prevalence of smoking among the students resided at dormitories in Golestan university of medical sciences. Iran Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2014;13(4):460–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amiri M, Khosravi A, Chaman R, Sadeghi Z, Sadeghi E, Raei M. Addiction potential and its correlates among medical students. Open Public Health Journal. 2021;14(1):32–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahebihagh MH, Hajizadeh M, Ansari H, Lesani A, Fakhari A, Mohammadpoorasl A. Modeling the underlying tobacco smoking predictors among 1st year university students in Iran. Int J Prevent Med. 2017;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Miri-Moghaddam M, Shahrakipour M, Nasseri S, Miri-Moghaddam E. Higher prevalence of water pipe compared to cigarette smoking among medical students in Southeast Iran. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2019;27(3):188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allahverdipour H, Abbasi-Ghahramanloo A, Mohammadpoorasl A, Nowzari P. Cigarette smoking and its relationship with perceived familial support and religiosity of university students in Tabriz. Iran J Psychiatry. 2015;10(3):136–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heydari G, Yousefifard M, Hosseini M, Ramezankhani A, Masjedi MR. Cigarette smoking, knowledge, attitude and prediction of smoking between male students, teachers and clergymen in Tehran, Iran, 2009. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(5):557–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabir K, Mohammadpoorasl A, Esmaeelpour R, Aghazamani F, Rostami F. Tobacco use and substance abuse in students of Karaj Universities. Int J Prev Med. 2016;7(1):105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keshavarz H, Khami MR, Jafari A, Virtanen JI. Tobacco use among iranian dental students: A national survey. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19(8):704–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taheri E, Ghorbani A, Salehi M, Sadeghnia HR. Cigarette smoking behavior and the related factors among the students of mashhad university of medical sciences in Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shekari F, Habibi P, Nadrian H, Mohammadpoorasl A. Health-risk behaviors among Iranian university students, 2019: a web-based survey. Arch Public Health. 2020;78(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Ghodousi A, Aminoroaia M, Attari A, Maracy M, Maghsoodloo S. The prevalance of cigarette smoking and some demographic and psychological characteristics in students of Islamic Azad University of Khorasgan. Iran J Res Behav Sci. 2013;10(6):401–10. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nazemi S, Chaman R, Davardoost N. Prevalence and reasons of inclination towards smoking among university students. 2012.

- 21.Attari A, Aminoroaia M, Maracy MR. The survey of frequency of cigarette smoking in the students of medical school in Isfahan university of medical sciences and its relation to some demographic characteristics and psychiatric symptoms. 2015.

- 22.Panahi R, Ramezankhani A, Tavousi M, Mehrizi A, Osmani F, Niknami S. Factors associated with smoking among students: Application of the Health Belief Model. Payesh (Health Monitor). 2017;16(3):315–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bashirian S, Fathi Y, Barati M. Comparison of efficacy and threat perception processes in predicting smoking among university students based on extended parallel process model. Avicenna J Clin Med. 2014;21(1):58–65. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mokhtari N, Ghodsi H, Asiri S, Kazemnezhad E. Relationship between Health Belief Model and smoking in male students of Guilan University of Medical Sciences. 2013.

- 25.Tavakolizadeh J, Moshki M, Moghimian M. The Prevalence of smoking and its relationship to self-esteem among students of Azad university of Gonabad. J Res Health. 2012;2(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghodsi H, Mokhtari Lake N, Asiri S, Kazem Nezhad Leili E. Prevalence and correlates of cigarette smoking among male students of Guilan University of Medical Sciences. J Holistic Nurs Midwifery. 2012;22(1):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Araban M, Karimy M, Taher M, Baiati S, Bakhtiari A, Abrehdari H, et al. Predictors of tobacco use among medical students of ahvaz university: A study based on theory of planned behavior. Journal of Education and Community Health. 2015;2(1):10–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahimzadeh M, Rastegar H, Fazel KJ. Prevalence and causes of tendency to cigarette and water pipe smoking among male and female physical education students in University of Kurdistan. J Health. 2016;7(5):680–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shafiie N, Shamsi A, Ghaderi M. Correlation between drug use, alcohol, smoking and psychiatric drugs with the academic progress in university students in Bam city. J Health Promotion Manage. 2013;2(1):49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shamsipour M, Bahador RK, Mohammadpoorasl A, Mansouri A. Smoking prevalence and associated factors to quit among Tabriz dormitory university medical students, Tabriz, Iran. 2012.

- 31.Jafari A. Spending Leisure Time Compared to Male Students in University of Payam Noor University of Counties Kaleibar, With an Amphasis on Sporting Activities and it was Impact on Smoking Trend (Irandoc) 2012.

- 32.Mehdizadeh Noudehi T. The Relationship between Mental Health and Academic Achievement among Cigarette Smokers & Non- smoker University Student 2014.

- 33.Ghavami K. Evaluation of Relation Ship Between Adult ADHD & Smoking In Students In Islamic Azad University In Shahrood In 1390 2014.

- 34.Tarrahi MJ, Mohammadpoorasl A, Ansari H, Mohammadi Y. Substance Abuse and its predictors in freshmen students of Lorestan universities: subgrouping of college students in West of Iran. Health Scope. 2017;6(4).

- 35.Halvaiepour Z, Nosratabadi M. Investigating the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and cigarette smoking in university students in Isfahan. Iran J Child Adolescent Trauma. 2022;15(2):319–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.RezaKhani Mogaddam H, Shojaezadah D, Sadeghi R, Pahlevanzadah B, Shakouri Moghaddam R, Fatehi V. Survey of prevalence and causes of the trend of hookah smoking in Tehran University Students of Medical Sciences 2010–2011. Toloo e Behdasht. 2013;11(4):103–13. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehri A, Rezvani Ghalhari M, Mazaheri-Tehrani A, Bashardoust P, Mohammadi M, Dehghani R. Prevalence of smoking and its related factors among students of Kashan university of medical sciences. Iran J Health Environ. 2023;16(3):565–78. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghaffari R, Osouli Tabrizi S, Abdolalipour S, Mirghafourvand M. Prevalence of cigarette smoking among iranian medical students and its relationship with mental health. Int J Health Promot Educ. 2022:1–12. 10.1080/14635240.2022.2138719.

- 39.Sadighpour A, Dolatkhah N, Khanzadeh S, Baradaran Binazir M, Heidari F. The prevalence and determinant factors of high-risk behaviours among medical students in North-West of Iran. Int J Health Promot Educ. 2023;61(4):158–68. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moghaddam Tabrizi F, Sharafkhani R, Heydari Z, Khorami Markani A, Ahmadi Aghziyarat N, Khalkhali HR. Estimating the prevalence of high-risk behaviors using network scale-up method in medical university students. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11:356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zarei M, Asheghi M, Abbasi A, Baradaran BM. The Prevalence, Effective Factors, and Nicotine Dependence Among Medical Students: A Cross-sectional Study. Tobacco Health. 2023;2(3):135–42. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shekari F, Mohammadpoorasl A, Nadrian H, Jafarabadi MA, Akbari H. Prevalence and Determinants of Non-daily Smoking Among Iranian University Students: A Web-based Survey. 2022.

- 43.Adham D, Afrashteh S, Alimohamadi Y, Maghsodlou-Nejad V, Khodadost B, Abbasi-Ghahramanloo A. Patterns of substance use and predictors of class membership among university male students: a latent class analysis. J Substance Use. 2023;28(4):629–35. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leshargie CT, Alebel A, Kibret GD, Birhanu MY, Mulugeta H, Malloy P, Wagnew F, Ewunetie AA, Ketema DB, Aderaw A, Assemie MA. The impact of peer pressure on cigarette smoking among high school and university students in Ethiopia: A systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0222572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Deressa Guracho Y, Addis GS, Tafere SM, Hurisa K, Bifftu BB, Goedert MH, Gelaw YM. Prevalence and factors associated with current cigarette smoking among Ethiopian university students: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Addict. 2020;2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Alotaibi SA, Alsuliman MA, Durgampudi PK. Smoking tobacco prevalence among college students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Nasser AM, Geng Y, Al-Wesabi SA. The prevalence of smoking (cigarette and waterpipe) among university students in some Arab countries: a systematic review. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 2020;21(3):583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Organization WHO. Tobacco use declines despite tobacco industry efforts to jeopardize progress 16/01/2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/16-01-2024-tobacco-use-declines-despite-tobacco-industry-efforts-to-jeopardize-progress.

- 49.(HRB) HRB. 20 years since Ireland banned smoking indoors with 800,000 fewer smokers today. 20/10/2022. Available from: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/40797/.

- 50.Romer D. Brazil’s efforts to reduce cigarette use illustrate both the potential successes and challenges of this goal. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(4):549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tobacco Free Ireland Annual Report 2021. Available from: https://assets.gov.ie/237726/7021f09a-13fa-4a05-aabb-cd22e742a0d1.pdf.

- 52.EMRO. Tobacco Free initiative. Available from: https://www.emro.who.int/tfi/news/islamic-republic-of-iran-qom-tobacco-free-city-initiative.html#:~:text=The%20Islamic%20Republic%20of%20Iran,of%20the%20Act%20in%202007.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Reza Negarandeh], upon reasonable request.