ABSTRACT

Cognitive impairment can negatively influence daily functioning. Current cognitive measures are essential for diagnosing cognitive impairment, but findings on these tests do not always represent the level of cognitive functioning in daily life. Therefore, this study aimed to design a structured measurement instrument to observe and rate the impact of cognitive impairment in daily life, named the cognition in daily life scale for persons with cognitive problems (CDL). In this paper we describe the development, expected usability, and psychometric properties (content and face validity) of the instrument. The CDL was established through three consecutive development phases: (1) item selection, (2) item categorization and comparison, and (3) item revision and manual construction. Subsequently, a panel of eleven international experts rated the relevance of the selected items and provided comments on the expected usability and face validity. Content validity was estimated with the content validity index, based on which four items were removed. The experts’ comments led to minor adjustments of the manual, domains, and formulation of the maintained items. The final instrument consists of 65 items describing behaviour that relies on cognitive functions within six domains. Future research should focus on evaluating the construct validity and reliability of the CDL.

KEYWORDS: Cognitive functioning, Neuropsychological assessment, Ecological validity, Content validity, Observation

Introduction

Cognitive functioning can be significantly impacted by a range of brain conditions, including stroke, traumatic brain injury, hypoxic brain injury, or brain damage caused by neurological diseases. Impaired cognitive functioning can influence a person’s functioning in daily activities, such as work or hobbies, and their relationships with other people, which subsequently affects their quality of life (Azouvi et al., 2017; van der Kemp et al., 2019; Rabinowitz & Levin, 2014; Libeson et al., 2020). In general, cognition is defined as “an information-handling process that covers the whole process of an individual's capacity to perceive, register, store, retrieve and use information” (Lezak et al., 2004). Cognitive impairments can therefore occur across various domains, such as memory or attention. The influence of these cognitive impairments on everyday functioning is referred to as cognition in daily life and comprises the cognitive component of spontaneous behaviour. A term closely related to this is functional cognition, which refers to the ability to accomplish daily activities that rely on cognitive processes (Donovan et al., 2008). The difference is that functional cognition is the ability to actually perform the task, while cognition in daily life refers to the cognitive processes and abilities involved in carrying out tasks. For instance, when considering the tasfk of cooking a meal, cognition in daily life examines the underlying cognitive functioning such as attention, memory, and planning involved in successfully completing the task, instead of evaluating the accomplishment itself (Domensino et al., 2022). Understanding the impact of cognitive impairments on daily life is important for providing individuals with the necessary support and treatment. It acknowledges the fact that many life domains can be affected by a brain condition, while also encompassing the capacity to compensate for any cognitive impairments. This way, measuring cognition in daily life is important for doing justice to the experiences of persons with brain conditions.

Cognitive impairments are usually measured with cognitive tests as part of a neuropsychological assessment (NPA) (van Heugten et al., 2020). The cognitive test battery in an NPA provides a normative application of performance-based assessments of several cognitive strengths and weaknesses in a controlled setting (Harvey, 2022), and is a prerequisite for determining the presence of cognitive impairment. However, there can be a gap between the results on cognitive tests and the extent to which these impairments lead to limitations on everyday tasks that are caused by cognitive functioning. On the one hand, a patient with a good score on cognitive tests in a controlled testing environment – indicating the absence of severe cognitive dysfunction – , can still face challenges with tasks requiring cognitive functioning in the complexity of daily life (Chaytor & Schmitter-Edgecombe, 2003). On the other hand, a patient who performs poorly on cognitive tests may be able to use effective compensatory strategies in daily life and function adequately (Chaytor & Schmitter-Edgecombe, 2003). Thus, since cognitive tests are designed to measure cognitive strengths and weaknesses in a controlled setting and focus on one aspect of cognition at a time, the results on these tests are not always on a one-to-one basis generalizable to daily life situations requiring the integration of multiple cognitive functions in a multi-sensory environment. Therefore, cognitive tests can have limited ecological validity (Chaytor & Schmitter-Edgecombe, 2003; Chevignard et al., 2000), which is why NPAs ideally include other assessment approaches (Madsø et al., 2021) to capture the impact of various cognitive impairments on complex tasks in a real-world environment.

Recently, we proposed a continuum of measurement instruments for cognition, ranging from single-domain cognitive tests to measurements of cognition in a daily life setting (Domensino et al., 2022). We concluded that the most accurate representation of real-world outcomes is through direct observation of spontaneous behaviour of the person in their own environment (Domensino et al., 2022; Marcotte et al., 2010), resulting in high ecological validity (Bouwens et al., 2008). However, existing observational measures are often unstructured (Bootes & Chapparo, 2002), focus on the ability to successfully, (in)dependently and safely perform tasks such as activities of daily living (ADLs; Edemekong et al., 2017), or rely on the evaluation of instructed behaviour, as is the case for the kitchen task assessment (KTA; Baum & Edwards, 1993). Some examples of structured observational instruments focused on spontaneous behaviour do exist, such as the Behavioral Assessment Tool for Cognition and Higher Function (BATCH) (Miller et al., 2007) and the Nurses’ Observation Scale of Cognitive Abilities (NOSCA) (Persoon et al., 2011). Both instruments show excellent reliability and validity, but were designed for use in specific populations, such as neuropsychiatric patients (Miller et al., 2007) and geriatric patients (Persoon et al., 2011), respectively, and therefore have specific measurement aims that do not generalize to other populations. Additionally, the Hoensbroeck Disability Scale for Brain Injury (HBSH) (Torenbeek et al., 1998) is an observation instrument for cognition in daily life that was developed over 25 years ago. Despite its historical significance to raising awareness of measuring cognition in daily life in Dutch healthcare, it is currently considered somewhat outdated, and its structure does not correspond to cognitive domains that are distinguished in contemporary NPA.

Since widely available, well-validated, and applicable standardized measurement instruments for the measurement of cognition in daily life are currently lacking, we recently developed a structured measurement instrument to assess the impact of cognitive impairment in daily life, named the cognition in daily life scale for persons with cognitive problems (CDL). We designed the CDL according to the following criteria (Domensino et al., 2022): it needs to cover multiple neurocognitive domains (e.g., attention, memory, executive functioning, and/or language [Harvey, 2022]); include daily life situations; not interfere with a patient’s daily tasks or involve instructed behaviour; and be applicable for use in populations with brain conditions of different etiologies and severities. The first step in the validation process of any measurement instrument is to establish its content validity to ensure the items accurately represent the underlying construct of cognition (Sireci, 1998). Therefore, the aim of the present study was twofold, (1) to describe the development of the CDL, and (2) to assess the initial psychometrics properties (content and face validity) of the instrument.

Materials and methods

Instrument development

Phase 1: Establishing the initial item inventory

The item inventory of the CDL was based on six existing instruments. Three of these are validated observation measures of spontaneous behaviour and were previously identified in a review on the various approaches to measuring cognition (Domensino et al., 2022), namely, the Behavioral Assessment Tool for Cognition and Higher Function (BATCH) (Miller et al., 2007), Nurses’ Observation Scale of Cognitive Abilities (NOSCA) (Persoon et al., 2011), and the Hoensbroeck Disability Scale for Brain Injury (HBSH) (Torenbeek et al., 1998). Additionally, three instruments were included because of their potential relevance to the topic based on consensus among the authors, even though they have not been validated as observation measures of spontaneous behaviour and were therefore not included in the review. These measures included the cognition subscale of the WCN Observation list for Cognition, emotion, and behaviour (WOLC) (van Heugten et al., 2003), the Árnadóttir OT-ADL Neurobehavioural Evaluation (A-ONE) (Árnadóttir, 1992), and the Interdisciplinary Cognitive Intervention manual (ICB) (Spikman et al., 2014). The ICB is a care protocol manual used to observe patients with cognitive difficulties.

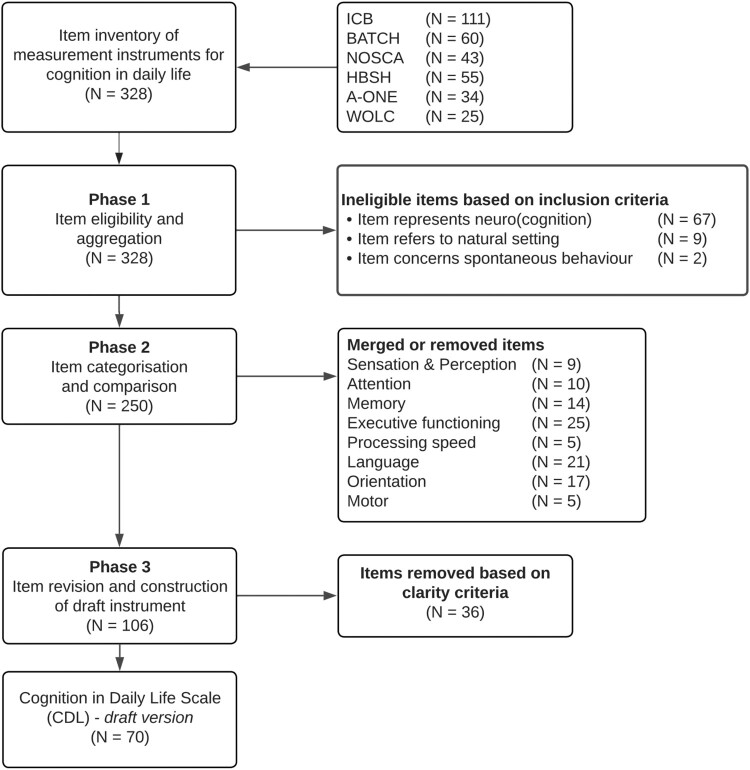

All items of these selected instruments were taken into consideration (N = 328) and were evaluated by AD and a research assistant. Subsequently, iterative consensus meetings among the author team were organised to evaluate the items against three inclusion criteria that together define cognition in daily life (Domensino et al., 2022). These criteria were: (1) the item represents (neuro)cognitive functioning based on the cognitive domains that are specified in phase 2, (2) the item refers to a natural setting (i.e., the patient’s everyday environment, which can include but is not limited to a clinical setting), and (3) the item concerns spontaneous behaviour. These criteria were proposed to ensure this procedure resulted in the selection of 250 items. An overview of the item selection process is specified in the flowchart depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of item selection for the CDL.

Phase 2: Item categorization and comparison

The 250 selected items were aggregated and classified into six cognitive domains: (1) alertness, processing speed and attention; (2) perception; (3) memory; (4) actions (praxis); (5) language and communication; and (6) task behaviour (executive functioning). The domains were based on the selected instruments and compared to the suggested domains for measuring functional cognition after stroke by Donovan and colleagues (Donovan et al., 2008). We deliberately chose to include only domains of neurocognition, since measuring other forms of cognition in daily life – such as social cognition – is beyond the scope of the instrument. After the categories were set, the selected items were categorized and compared based on similarities in their description. The ICB was used as the departure point for the comparison as it comprised the most items (N = 87). Similar items were merged, for instance by adding examples originating from one item to a more clearly formulated item from another scale, which resulted in 106 items. The categorization and comparison of items was based on discussions among AD and a research assistant and were cross validated by the other members of the author team.

Phase 3: Item revision and manual construction

All remaining items were further examined and rewritten in accordance with three criteria as proposed by Streiner and colleagues (Streiner et al., 2015), namely, avoid negative items, avoid ambiguity, and keep the items short. Following the revision of items, all items were incorporated into the draft version of the CDL. Subsequent group discussions among the authors resulted in the elimination of 36 redundant items (when two items exhibited excessive similarity) or unclear items (when, despite item rewriting, multiple interpretations remained possible). This process resulted in the final selection of 70 items across six cognitive domains.

Finally, a manual was written with a description of the instrument, instructions on the observation procedure, and guidelines for the scoring system. The scoring system was designed according to the recommendations proposed by Streiner and colleagues (Streiner et al., 2015) in order to maximize precision and minimize bias. The rating scale consists of the scoring of frequency and severity of behaviour, which are rated from 0 (not present) to 3 (always present) for frequency, and 0 (not present) to 3 (severe problem) for severity. The same type of rating scale is used in the neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI; Cummings, 2020), which is proven to be valid and has been used in over 350 clinical trials.

Content validity

Study design

This mixed-method study was designed according to the adapted COSMIN guidelines for observational instruments proposed by Madsø and colleagues (Madsø et al., 2021). The study recruited an international expert panel to determine the content validity of the draft CDL, which resulted from the development process described in the previous section.

Participants

A snowball sampling technique was used to recruit participants based on professional connections of the research network of the authors. Eleven experts from four different countries (Netherlands, UK, Australia, and USA) were invited to participate. The minimum sample size to avoid chance agreement is five participants (Zamanzadeh et al., 2014), however, because larger samples allow for the use of less stringent cut-off values in item selection procedures (Lynn, 1986) we decided on the current sample size. Participants were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) having a background in and knowledge of neuropsychology, (2) having experience in evaluating measurement instruments that can be used to assess cognition, and (3) being or having been employed in healthcare settings for persons with brain conditions (rehabilitation, neurology/neurosurgery, neuropsychiatry, elderly care, or disability care), or in research areas associated with these disciplines. Participants were ineligible if they had been involved in the development of the CDL to avoid bias.

Procedure

Experts were requested to participate via email, which included a briefing letter with information on the project and an outline of the procedure. Participants could reply to the invitation in the email to be enrolled, after which they received a personal link to the online questionnaire provided through Qualtrics (2014). After providing informed consent, participants answered questions on demographic and professional information, and questions on item relevance, expected usability, and comprehensibility. The questionnaire took approximately 30 minutes to complete. The experts’ suggestions were considered in a subsequent project team discussion and implemented when appropriate.

The current study was exempted from ethical review as no private or sensitive data were collected. Collected information was based on expert opinion only. Regardless, potential experts were informed about the study objectives and procedures. Data was stored according to the General Data Protection Regulation. Participants provided informed consent by agreeing to the invitation that they received.

Materials

Demographic and professional information

Demographic questions included age, gender, and country of residence. Questions about employment included information on the type of institution experts work at and their years of experience in evaluating measurement instruments that can be used to assess adult patients or their years of employment in care facilities.

Content and face validity/expected usability

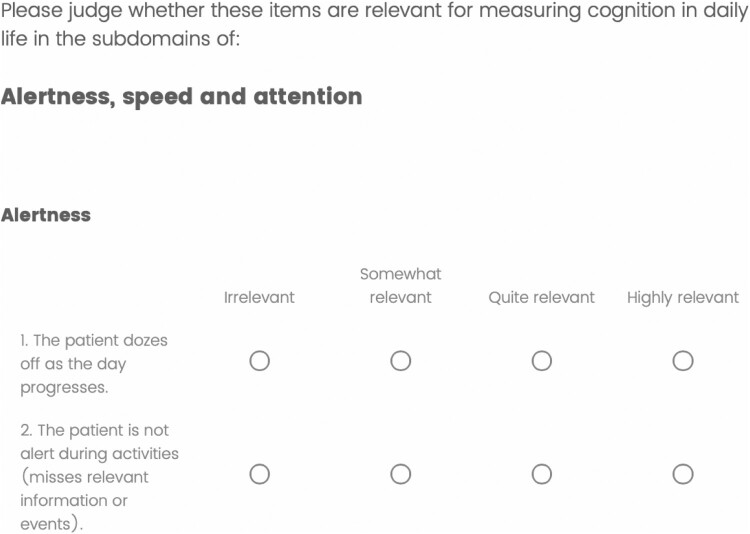

Experts received an online questionnaire in which they were asked to evaluate each of the proposed items in the draft version of the CDL (70 items across 6 domains) in terms of relevance within the proposed subdomain of cognition in daily life. Item relevance was measured on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (irrelevant) to 4 (highly relevant) (Lynn, 1986). A screenshot of the questionnaire is included in Appendix 1. After each domain, the experts could elaborate on their opinion regarding the items they rated irrelevant or somewhat relevant, and whether they considered the items more fitting in a different subdomain.

At the end of the questionnaire, experts were asked additional questions related to the face validity, comprehensibility, and whether they expected the instrument to be feasible for use. Face validity refers to the degree to which an instrument appears to test the represented construct (Taherdoost, 2016) and was assessed by the question “What do you think of the overall correspondence of the instrument to the construct cognition in daily life?”. Appendix 1 shows a complete overview of all the questions that were presented to the experts. These questions cover the COSMIN criteria of relevance and comprehensibility for evaluating the content validity of outcome measures (Terwee et al., 2018).

Data analysis

The present study made use of both qualitative and quantitative data analysis. Comments on face validity and expected usability were thematically coded and summarized based on a mixture of the general inductive approach for analysing qualitative evaluation data (Thomas, 2003) and the deductive method. The deductive method was used by posing specific questions to the experts related to our research question. The inductive method was used when the answers to a question encompassed multiple themes that we had not considered before but were deemed important to code. The experts’ suggestions were discussed among members of the research team and applied when considered appropriate.

The content validity of each item was established with the content validity index (CVI) (Polit et al., 2007), which was calculated as (number of experts giving a rating of either 3 or 4)/(total number of experts). The cut-off for item relevance was set at 0.78 (Lynn, 1986; Stewart et al., 2005). Items below the cut-off were discarded. A CVI for the total scale (S-CVI) was also calculated by averaging the CVI’s of the retained items. The cut-off score for the S-CVI was set at .90 (Polit et al., 2007). An S-CVI below the cut-off score would require another round of expert reviews.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 shows an overview of the expert panellists’ demographic characteristics. The experts were aged between 39 and 69, and with an average 25 years of experience in evaluating measurement instruments that can be used to assess adult patients or being/having been employed in care facilities.

Table 1.

Demographic and professional information (N = 11).

| Variables | n |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 6 |

| Male | 4 |

| I would rather not say | 1 |

| Age | |

| 39–48 | 5 |

| 49–58 | 3 |

| 59–69 | 2 |

| I would rather not say | 1 |

| Country | |

| Netherlands | 6 |

| UK | 2 |

| USA | 1 |

| Australia | 2 |

| Current employment* | |

| University | 9 |

| Rehabilitation center | 6 |

| Hospital | 4 |

| Other | 2 |

Note.* = Several participants were employed at more than one type of institution.

Content validity score

Table 2 shows the CVIs for each item on the draft version of the CDL. Out of the 70 items, only four (item 16, 20, 33, and 44) had a CVI lower than 0.78 and were removed. Forty-three percent of the items obtained a score of 1. All experts agreed that these items were highly relevant to measure cognition in daily life. The S-CVI was 0.94, therefore, no further round of expert reviews was necessary.

Table 2.

CVI for each item in the draft version of the Cognition in Daily Life questionnaire.

| Domain | Item # in draft version | Question in draft version | CVI | Question in final version | Item # in final version |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alertness, processing speed and attention | |||||

| Alertness | 1 | The patient dozes off as the day progresses | 0.82 | The patient shows signs of drowsiness as the day progresses | 1 |

| 2 | The patient is not alert during activities (misses relevant information or events). | 1 | The patient is not alert during activities (misses relevant information or events). | 2 | |

| Information processing speed | 3 | The patient cannot keep up with the speed in which information is provided (e.g., reading subtitles) and thus misses information. | 0.82 | The patient cannot keep up with the speed in which information is provided (e.g., reading subtitles or following a conversation) and thus misses information. | 3 |

| 4 | The patient performs tasks slowly (e.g., getting dressed or making coffee). | 1 | The patient performs tasks slowly (e.g., getting dressed slowly when under pressure to leave the house). | 4 | |

| 5 | The patient responds slowly (e.g., in a conversation or to instructions). | 1 | The patient responds slowly (e.g., in a conversation or to instructions). | 5 | |

| Automatic attention | 6 | The patient’s attention is not automatically drawn to relevant information from the environment. | 1 | The patient’s attention is not automatically drawn to relevant information from the environment (e.g., does not notice a person who just walked into the room). | 6 |

| 7 | The patient pays insufficient attention to one side of his/her body (e.g., forgets to wash the affected side, bumps into objects on the affected side). | 1 | The patient pays insufficient attention to one side of his/her body or one side of space (i.e., neglect) (e.g., forgets to wash the affected side, bumps into objects on the affected side). | 7 | |

| Focused attention | 8 | The patient is not able to focus on a task (when there are no distractions). | 0.91 | The patient cannot stay focused during an activity for an extended time (e.g., when following a conversation or performing a task). | 8 |

| 9 | The patient is not able to focus on a task when there are distractions. | 1 | The patient is not able to focus on a task when there are distractions. | 9 | |

| Divided attention | 10 | The patient has difficulties doing two things at the same time (e.g., talking and walking). | 1 | The patient has difficulties doing two things at the same time (e.g., talking and walking). | 10 |

| 11 | The patient has difficulties switching between activities. | 1 | The patient has difficulties switching between two simultaneous activities or sources of information. | 11 | |

| Sustained attention | 12 | The patient cannot stay focused during an activity (e.g., when following a conversation or performing a task). | 0.91 | The patient cannot stay focused on an activity for an extended period of time (e.g., when following a conversation or performing a task.) | 12 |

| Perception | |||||

| Visual perception | 13 | The patient does not recognize objects, or mistakes them for something else. | 1 | The patient does not recognize objects, or mistakes them for something else. | 13 |

| 14 | The patient does not recognize familiar faces. | 0.91 | The patient does not recognize familiar faces. | 14 | |

| 15 | The patient does not recognize letters, symbols and/or numbers. | 0.91 | The patient does not recognize letters, symbols and/or numbers. | 15 | |

| 16 | The patient does not recognize possessions as his/her own (e.g., his/her own glasses). | 0.64 | This item was removed | ||

| Auditory perception | 17 | The patient does not recognize sounds or does not respond adequately to sounds (e.g., sound of alarm clock). | 0.91 | The patient does not recognize sounds or does not respond adequately to sounds (e.g., sound of alarm clock). | 16 |

| Spatial perception and orientation | 18 | The patient gets lost in a familiar environment. | 0.91 | The patient gets lost in a familiar environment. | 17 |

| 19 | The patient gets lost in an unfamiliar environment (e.g., supermarket or other department of the care facility). | 0.91 | The patient gets lost in an unfamiliar environment (e.g., supermarket or other department of the care facility). | 18 | |

| 20 | The patient looks for an object that is in the room but cannot find it (e.g., glasses on the table). | 0.73 | This item was removed | ||

| 21 | The patient cannot estimate the distance to or position of an object in relation to him/herself and therefore misses the object when reaching for it. | 1 | The patient cannot estimate the distance to or position of an object in relation to him/herself and therefore misses the object when reaching for it. | 19 | |

| Memory | |||||

| Orientation in time and place | 22 | The patient does not know where he/she is. | 1 | The patient does not know where he/she is. | 20 |

| 23 | The patient does not know whether it is morning, afternoon or evening. | 0.91 | The patient does not know whether it is morning, afternoon or evening. | 21 | |

| 24 | The patient does not know what day it is. | 0.82 | The patient does not know what day it is. | 22 | |

| Autobiographical information | 25 | The patient does not know his/her own personal data (address, date of birth, etc.). | 0.82 | The patient does not know his/her own personal data (address, date of birth, etc.). | 23 |

| 26 | Patient does not remember autobiographical information (e.g., personal events in the past). | 0.91 | Patient does not remember autobiographical information (e.g., personal events in the past). | 24 | |

| 27 | The patient fills the gaps in his/her memory with incorrect information (confabulates). | 0.91 | This item was moved to 65 | ||

| Prospective memory | New item: The patient does not show up to scheduled appointments. | 25 | |||

| Acquisition and encoding of information | 28 | The patient cannot recall recent information that has to be applied immediately (e.g., instructions on how to perform a task). | 0.82 | The patient cannot recall recent information that has to be applied immediately (e.g., instructions on how to perform a task). | 26 |

| 29 | The patient is not able to learn new tasks (habit formation). | 1 | The patient is not able to learn new tasks (habit formation) (e.g., operating a new coffee machine) | 27 | |

| Retention of information | 30 | The patient is not able to continue an activity after an interruption, because the patient does not remember what he/she was doing. | 0.91 | The patient is not able to continue an activity after an interruption, because the patient does not remember what he/she was doing. | 28 |

| Recall of information | 31 | The patient does not remember any events, not even when asked to recall a specific event (e.g., remember we had pasta for dinner yesterday?). | 0.91 | The patient has difficulty remembering recent events, not even when asked to recall a specific event (e.g., remember what we had for dinner yesterday?). | 29 |

| Recognition | New item: The patient doesn’t spontaneously remember previously retained information but does recognize it when it’s mentioned (e.g., remember we had pasta for dinner yesterday?) | 30 | |||

| Actions | |||||

| Organization of actions | 32 | The patient performs the parts of an action in an incorrect order (i.e., apraxia) (e.g., when getting dressed). | 1 | The patient performs the parts of an action in an incorrect order (i.e., apraxia) (e.g., when getting dressed). | 31 |

| 33 | The patient performs movements in a clumsy way. | 0.73 | This item was removed | ||

| Use of objects | 34 | The patient uses objects in an incorrect, clumsy or unsafe way. | 1 | The patient uses objects in an incorrect, clumsy or unsafe way. | 32 |

| 35 | The patient uses the wrong object to perform an activity (e.g., uses a comb to clean his/her teeth). | 1 | The patient uses the wrong object to perform an activity (e.g., uses a comb to clean his/her teeth). | 33 | |

| Language & communication | |||||

| Understanding of spoken language | 36 | The patient does not respond (adequately) to single spoken words. | 1 | The patient does not respond adequately to spoken language (e.g., does not understand the meaning). | 34 |

| 37 | The patient does not respond (adequately) to spoken sentences. | 0.91 | This item was combined with draft version item #36 | ||

| 38 | The patient does not respond to spoken information consisting of several sentences (e.g., a route description and/or instructions). | 1 | The patient does not respond to spoken information consisting of several sentences (e.g., a route description and/or instructions). | 35 | |

| 39 | The patient does not understand figurative language and/or metaphors and humor (e.g., “my hands are tied”). | 1 | The patient does not understand figurative language and/or metaphors and humor (e.g., “my hands are tied”). | 36 | |

| Language production | 40 | The patient cannot come up with correct words or names. | 1 | The patient cannot come up with correct words or names. | 37 |

| 41 | The patient says other words than what he/she means (paraphasia). | 0.91 | The patient says other words than what he/she means (paraphasia). | 38 | |

| 42 | The patient cannot put into words what he/she means (exactly). | 0.91 | The patient cannot verbally express what he/she means (exactly). | 39 | |

| 43 | The patient cannot formulate correct sentences. | 0.91 | The patient cannot formulate grammatically correct sentences. | 40 | |

| Speaking | 44 | The patient cannot speak | 0.73 | This item was removed | |

| Reading | 45 | The patient cannot understand single written words. | 1 | The patient cannot understand single written words. | 41 |

| 46 | The patient cannot understand written sentences and/or texts. | 1 | The patient cannot understand written sentences and/or texts. | 42 | |

| Writing | 47 | The patient cannot write single words. | 1 | The patient cannot write single words. | 43 |

| 48 | The patient cannot write sentences and/or texts. | 1 | The patient cannot write sentences and/or texts. | 44 | |

| Language content | 49 | When telling a story, the patient cannot distinguish between what is important and what is less important (is not to the point). | 1 | When telling a story, the patient cannot distinguish between what is important and what is less important (is not to the point). | 45 |

| 50 | The patient skips from one subject to another. | 0.91 | The patient finds it hard to stay on topic and drifts off topic in conversation (i.e., tangential speech). | 46 | |

| Social communication skills | 51 | The patient does not make eye contact in a conversation. | 0.91 | The patient does not make eye contact in a conversation. | 47 |

| 52 | The patient interrupts others in a conversation. | 0.91 | The patient interrupts others in a conversation. | 48 | |

| Item moved: The patient does not start a conversation. | 49 | ||||

| Insight into own situation | 53 | The patient denies any limitations, although they are obviously present. | 0.82 | This item was removed | |

| 54 | The patient is aware of his/her limitations but shows little insight into the consequences in daily life. | 0.91 | This item was removed | ||

| Task behaviour | |||||

| Goal setting | 55 | The patient cannot really determine what needs to be done when performing a new activity. | 0.91 | The patient cannot really determine what needs to be done to achieve his/her goal when performing a new activity. | 50 |

| 56 | The patient sets unrealistic goals. | 1 | The patient sets unrealistic goals (e.g., being able to work full-time immediately after being away for a long time). | 51 | |

| 57 | The patient only sets short-term goals (activity), no medium-term (day or week planning) and/or long-term (months, years) goals. | 0.82 | The patient only sets short-term goals (activity), no medium-term (day or week planning) and/or long-term (months, years) goals. | 52 | |

| 58 | The patient cannot think of solutions to a problem. | 1 | The patient cannot think of solutions to a problem. | 53 | |

| 59 | The patient does not prioritize and starts an activity without thinking. | 1 | The patient does not prioritize his/her activities. | 54 | |

| Planning and organization | 60 | The patient does not apply a step-by-step or efficient approach (e.g., when looking for an object). | 0.91 | The patient does not apply a step-by-step or efficient approach during an everyday task (e.g., when looking for an object). | 55 |

| 61 | The patient is not able to execute a plan. | 1 | The patient is not able to execute a scheduled plan. | 56 | |

| 62 | The patient does not anticipate events or activities (e.g., does not bring a towel when taking a shower or does not put on a coat when going outside). | 0.91 | The patient does not anticipate events or activities (e.g., does not put on a coat when going outside because he/she didn’t anticipate the weather conditions). | 57 | |

| Demonstrating initiative | 63 | The patient does not perform everyday activities on his/her own initiative (e.g., daily routines such as walking the dog or washing the dishes after dinner). | 1 | The patient does not perform everyday activities on his/her own initiative but performs these actions readily with prompting (e.g., daily routines such as walking the dog or washing the dishes after dinner). | 58 |

| 64 | The patient does not start non-routine activities on his/her own initiative (e.g., making an appointment at the hairdresser’s). | 0.91 | The patient does not start non-routine activities on his/her own initiative but performs these actions readily with prompting (e.g., making an appointment at the hairdresser’s). | 59 | |

| Self-inhibition | 65 | The patient does not start a conversation. | 0.91 | The patient starts an activity without thinking | 60 |

| 66 | The patient constantly starts something new. | 0.91 | The patient cannot control him/herself (i.e., stop inadequate on own initiative) (e.g., eats food when in sight of it or makes inappropriate remarks). | 61 | |

| 67 | The patient cannot control him/herself (e.g., eats food when in sight of it or makes inappropriate remarks). | 1 | This item was combined with the previous item. | ||

| Flexibility | 68 | The patient gets overwhelmed when plans change. | 0.82 | The patient is upset when plans change. | 62 |

| 69 | The patient cannot switch to new /another procedure if the situation requires this. | 0.91 | The patient cannot switch to new /another procedure if the situation requires this. | 63 | |

| Self-monitoring | 70 | The patient does not check what he/she is doing and fails to make corrections if necessary. | 0.91 | The patient does not monitor what he/she is doing and fails to make corrections if necessary. | 64 |

| This item was moved from 27. The patient fills the gaps in his/her memory or perception with incorrect information and is not able to judge the representation as false (confabulates) | 65 | ||||

Note. Domains in bold represent the overarching domains. Subdomains in italics were newly added in the final version. CVI scores indicated in bold are below the threshold of 0.78. Under “question in final version” the items that were rephrased are underlined, and text in bold refers to the removal, addition, or combination of items in the final version compared to the draft version.

Qualitative results of expected usability and face validity

In response to the open-ended questions, experts commented on the content, formulation, missing items, and expected usability of the CDL. Appendix 1 shows the questions that were asked to deduce the topics for the analysis. This feedback was discussed among members of the project team and the remaining items were revised accordingly. Table 2 shows the changes that were made based on the recommendations by the experts. Below, the topics from the qualitative analysis are presented separately.

Topic 1: Content

Most items accurately represent the underlying construct of cognition, and fit within the domains they were originally placed in. Nonetheless, following the experts’ remarks, the items on insight (draft version item 53 and 54) and speaking (draft version item 44) were removed because they do not strictly relate to cognition: “Speaking is a motor function I would argue.” And “Why include insight, since this is not a cognitive/activities domain; I understand the relevance, but then other neuropsychiatric symptoms would be relevant as well”. The item related to speaking (item 44: the patient cannot speak) also obtained a low CVI score.

Sometimes items were perceived to be too similar, which is why they were merged into a single item. For example, items 36 and 37 in the draft version were combined into item 34 in the final version. Both items were related to understanding language, although one was specifically about words and the other about sentences. This difference would be too difficult to observe in daily life.

Two items did not fit within the domain they were originally placed in. In the final version, item 49 was moved from demonstrating initiative to social communication because it explicitly concerns starting a conversation. Secondly, item 65 in the final version refers to confabulation and was moved from memory to self-monitoring after a comment that confabulation does not necessarily involve memory but signifies a deficit in reality monitoring.

Topic 2: Formulation

Overall, the experts found the CDL to be comprehensive, clear, and helpful for structuring their observations. They did recognize some ambiguity in the wording of several items and recommended improvements. For example, item 31 in the draft version (Table 2) “The patient does not remember any events, not even when asked to recall a specific event” was changed to “The patient has difficulty remembering recent events" to clarify the distinction between long-term memory and short-term recall. Similarly, to clarify certain items (e.g., item 6) the experts recommended to add examples, which can be found in Table 2.

Topic 3: Missing items

Experts could remark on which subdomains or items they found were missing. Following the experts’ remarks, we added item 25 on prospective memory. Moreover, item 31 in the draft version was split into items 29 (recall) and 30 (recognition) in the final version because they signify different aspects of memory. Several experts recommended the addition of social cognition to the instrument; however, this suggestion was not included. This decision will be further elaborated on in the discussion.

Topic 4: Expected usability

Lastly, the experts remarked on their expectations of the usability of the instrument in practice: “This will be a great guide to assure nothing is missed. I also think patients and families will relate well to the questions’. The experts remarked that the scores on the instrument can result in deeper discussion with the patient to obtain an even more complete view of their problems or can motivate the health professional to do more elaborate testing to explore the problem further: “Positive answers can clearly lead to more detailed questions to explore the problem further”. On the other hand, the experts cautioned that some items may be difficult to observe by an external observer, especially if the observer is not trained in recognizing cognitive problems.

All experts worked with people with brain injury and were asked whether they thought the CDL was suitable for this population. One of the participants commented “[…] perhaps different items should be added for use in a geriatric population. But this is not my field of expertise. Items are relevant for ABI behaviour in a rehabilitation centre.”

Experts were also asked about their opinion on the scoring system. Overall, responses to the rating scale were positive. The dimensions (frequency and severity) made a lot of sense to the experts: “I think respondents will find the combination of frequency and severity allows them to convey their impressions accurately”. Nonetheless, good instructions are needed to understand the differences in frequency and severity, and to give meaning to the total score of each domain.

Final instrument

The final version of the CDL consists of 65 items describing behaviour across 6 cognitive domains: (1) alertness, processing speed and attention; (2) perception; (3) memory; (4) actions (praxis); (5) language and communication; (6) task behaviour (executive functioning). All items are rated on a frequency times severity scale, producing a score for each cognitive domain separately. The final version is presented in Table 2.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe the development and evaluate the face and content validity of an observational measurement instrument for cognition in daily life, the CDL. The final CDL consists of 65 items across 6 cognitive domains and obtained a high content validity score. Similar scores were found in previous content validation studies of similar measurement instruments (Caruso et al., 2016; Juengst et al., 2019; Smits-Engelsman et al., 2020). The final CDL is a standardized measurement instrument that describes behaviour pointing towards problems in multiple cognitive domains; includes daily life situations; does not interfere with a patient’s daily tasks or involve instructed behaviour; and is applicable for use in brain injured populations with different aetiologies and severities.

Despite the high content validity score, the experts made suggestions for changes in wording and missing subdomains or items. Consequently, items on prospective memory, recall, and recognition were added to the instrument. Moreover, the manual was edited to clarify the distinction between frequency (how often does the example happen) and severity (to what extent is the patient restricted by this). The updated manual was included in Appendix 2. The experts also suggested to add social cognition as a separate domain to the CDL. Social cognition is a complex construct existing of multiple subdomains (e.g., emotion perception, theory of mind, social communication, identity recognition and empathy) (Wallis et al., 2022). Therefore, despite its significance to understanding the consequences of brain impairment in everyday life, it was decided not to include social cognition in the instrument. Following the same line of reasoning, the subdomains speech and insight were removed from the instrument, as they did not pertain to cognition in the narrow sense (Harvey, 2022). The main domains were not changed, and experts agreed on their completeness. Donovan and colleagues (Donovan et al., 2008) suggested 10 domains of functional cognition for stroke to inspire structured, ecologically valid measures of post-stroke cognition; language, reading and writing, numeric/calculation, limb praxis, visuospatial function, social use of language, emotion regulation, attention, executive function, and memory. The CDL includes eight of the suggested domains by Donovan et al., although three of these (language, reading and writing, and social use of language) were combined into one domain (language and communication). Calculation was not included as it is not considered a neurocognitive domain, but rather a cognitive process necessitating cognitive functions in the domains included in the CDL. Emotion regulation was not included as it is considered to be part of social cognition, and should therefore be observed with a specific measurement instrument.

In addition to the relevance rating, the experts were asked to judge the expected usability of the instrument. One of the experts questioned the applicability of the CDL to geriatric populations. Given that the CDL covers all subdomains of memory, we anticipate that the instrument can be used to capture cognitive problems in this population. However, some of the domains that are covered by the CDL may have limited relevance to patients of geriatric wards. Future research is needed to indicate whether the domains of the CDL can be scored and interpreted independently. This could allow for the administration of only those domains in which the clinician expects problems. The experts also cautioned that the measure may be difficult to use by untrained observers. To ascertain correct use of the instrument, it was decided that the current version of the CDL can only be administered by healthcare professionals who have at least obtained a bachelor’s degree with sufficient training in cognitive functioning, such as psychologists, occupational therapists, behaviour specialists, and nurses. This has important implications for the implementation of the CDL in outpatient settings; even though the behaviours described in the CDL do also pertain to life outside of a healthcare institution, it is unsure whether lay observers, such as family members, will also be able to complete the CDL. Nonetheless, the CDL could still be used in outpatient settings as part of community-based care.

The rating scale of the instrument was evaluated positively by the experts. Previous research (Fernandez et al., 2008) has shown that a frequency times severity scale is a valuable rating scale because it allows the observer to track the frequency, incidence, and dynamics of various phenomena over time. However, some of the experts commented that it might be complicated to distinguish frequency from severity of each sample behaviour, which led to the addition of scoring examples to the CDL’s manual.

It is important to note that the CDL is intended to complement, but not substitute cognitive tests as part of an NPA. Cognitive tests are essential for establishing an objective representation of standardized, cognitive performance, although the results on these tests may not directly translate to daily life. While the CDL provides an accurate and objective description of cognitive restrictions in daily life, it cannot be used to infer conclusions about cognitive impairment. Therefore, as part of an NPA, it would be useful to compare the results on both instruments to supply holistic, multidisciplinary diagnostics of the cognitive consequences of brain impairment.

Another key application of the CDL is in the evaluation of interventions aimed at managing cognitive problems in daily life. Cognitive rehabilitation is commonly applied to teach patients compensatory strategies which help them cope with cognitive impairments in their daily life. Even though it is believed to be effective for improving functioning (Cicerone et al., 2019), the results on cognitive tests are unlikely to reflect this improvement (Chaytor & Schmitter-Edgecombe, 2003; Chevignard et al., 2000; Cicerone, 2005). An instrument focusing on cognition in daily life could therefore provide more specific information on the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation for increasing cognitive functioning in daily life (van Heugten et al., 2020).

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths. The development and content validity assessment of the CDL followed the adapted COSMIN guidelines for observational measures (Madsø et al., 2021). The construct of cognition in daily life was previously defined through literature review and group discussions (Domensino et al., 2022). Decisions were made on the aim of the instrument as a tool for the evaluation of cognition in daily life across a broad group of patients with cognitive problems. Subsequently, items were selected based on existing cognition instruments, which is a method also used in several other highly rated observational instruments (Lawton et al., 1999; Lawton et al., 1996; Casey et al., 2014; Clare et al., 2012; Wood, 2005). Lastly, relevance and comprehensibility were evaluated by the expert panel during the content validity study.

The inclusion of international experts with an average of 25 years of experience with cognition measurement has ensured the relevance of the CDL for neuropsychological assessment and applicability to a wide variety of settings and patient populations. By translating the CDL to English and including experts from multiple countries, we created the opportunity for international implementation of the instrument. Moreover, the item inventory and cognitive domains which formed the basis of the CDL were derived from existing measures that are already accepted in the field, which enhances implementation chances of the instrument (Swinkels et al., 2011).

Our study also had some limitations. First, we used the content validity index (CVI) to quantify content validity. Although the CVI is the most widely used approach, there is a high possibility of a chance agreements due to the 4-point scale (Almanasreh et al., 2019). However, the risk of a chance agreement is reduced in a sample of 8–12 experts (Polit et al., 2007), and we included 11. Additionally, we made use of a structured content validity assessment form and asked the panel for additional comments with regards to their rating, which is considered good practice (Almanasreh et al., 2019). While experts from various countries were included, the geographical scope was limited to the Netherlands, the UK, Australia, and the US. Although we recognize the significance of ensuring newly developed instruments are applicable across diverse cultures, we believe that behaviors pertaining to cognition in daily differ among cultures. We therefore intentionally selected experts from countries sharing similar cultures and healthcare systems with the Netherlands.

Second, the COSMIN guidelines recommend additional rounds of expert reviews after modification of the instrument (Almanasreh et al., 2019), which was not implemented given the high overall content validity score. Additionally, changes in wording of the remaining items were minor, and only three items were added based on expert comments. Therefore, it is unlikely that more rounds of expert reviews would have yielded different results. The COSMIN guidelines also suggest piloting a new instrument to assess feasibility, which was not part of the current study, but is one of the proposed aims of future research into the CDL.

A last limitation relates to the nature of the instruments included in the study. In a previous review (Domensino et al., 2022) we identified the Utrecht Scale for Evaluating Rehabilitation (USER) (Ten Brink et al., 2017) as a suitable instrument for the measurement of cognition in daily life together with the BATCH, NOSCA, and HBSH. However, after careful consideration the USER was judged unsuitable for inclusion in the instrument as it lacks descriptive items reflecting spontaneous behaviour. Instead, the A-ONE was included despite its focus on task-oriented behaviour because some of the items were considered useful to the purpose of the instrument. In the end, only one item in the final CDL was based on the A-ONE.

Future research

Before the CDL is ready for use in daily practice, several further steps need to be taken. First, future research should investigate the usability of the CDL through pilot-testing in a sample of persons with cognitive problems (Donovan et al., 2008). Second, the construct validity, convergent and discriminant validity, and test-retest and interrater reliability of the instrument should be assessed to evaluate the ability of the CDL to provide stable and consistent results (Taherdoost, 2016). Similarly, an internal consistency assessment should be conducted to evaluate the relative contribution of each item to the underlying construct and estimate the maximum number of allowable missing items, or items that are scored as “not observed”. In addition, the responsiveness of the CDL should be tested to examine its suitability for evaluating rehabilitation effects (Terwee et al., 2003). Moreover, the results of the CDL need to be compared with the results of cognitive tests, as well as unstructured observations of healthcare professionals, to evaluate how multiple indices of cognition relate to each other. Eventually, future research may aim to expand the available set of instruments for measuring the consequences of brain conditions in daily life, for instance by developing instruments for the observation of social cognition and awareness of deficits in daily life.

Once the validity and reliability of the CDL have been established, the instrument needs to be integrated into regular healthcare facility procedures. To evaluate whether the CDL is suitable for use in an outpatient clinic, the relevance, comprehensibility, and applicability of the instrument should be evaluated when it is completed outside of a clinical setting, i.e., in community-based care.

Conclusion

The CDL is an observation instrument for assessing the impact of cognitive impairment in daily life. It is designed to be used in conjunction with cognitive tests as part of an NPA to support the diagnostic process by providing standardized information about real-life cognitive functioning. The final CDL consists of 65 items across six cognitive domains (alertness, processing speed and attention; perception; memory; actions (praxis); language and communication; and 6) task behaviour (executive functioning). Future research should focus on assessing the CDL's psychometric properties and identifying potential barriers and facilitators for future implementation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the experts who participated in the current study (in alphabetical order): Dirk Bertens, Jonathan Evans, Jessica Fish, Marthe Ford, Roy Kessels, Tanja Nijboer, Tamara Ownsworth, Jennie Ponsford, Peter Smits, Doriene van der Kaaden, and Jill Winegardner. We would also like to express our gratitude to Stephan Tap for his assistance in establishing the item inventory.

Appendices.

Appendix 1

Figure A1.

Screenshot of Qualtrics questionnaire outlining item relevance per subdomain.

Table A1.

Questions posed to the experts from the face validity questionnaire.

| Face Validity Questions | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Is there an item that you missed in the items that were proposed so far that you think we need to consider? |

| 2. | What is your opinion on the formulation of the items in the instrument? |

| 3. | What is your opinion on the rating scales (frequency and severity) of the instrument and the suggested Likert scale? |

| 4. | Is it clear how you should use the instrument? Are there any ambiguities? |

| 5. | How relevant are the items for the entire study population? |

| 6. | What do you think of the overall correspondence of the instrument to the construct cognition in daily life? |

| 7. | Once available, would you use the instrument in daily practice? |

Appendix 2. Updated manual of the CDL.

The cognition in Daily Life scale (CDL)

Manual

Objective

The CDL-ABI is a tool to observe problems in the daily life of people who suffered brain injury. It focuses on situations that require cognitive functioning and in which problems are likely to be caused by cognitive deficits. The tool helps clinicians to systematically categorise these cognitive problem situations, which is why the problem situations are grouped into six cognitive domains. The tool is not meant to draw conclusions about possible cognitive deficits; these deficits can only be assessed by means of cognitive tests as part of a full neuropsychological assessment. The results of the CDL-ABI should therefore always be interpreted in the light of other results obtained during neuropsychological examination.

Information obtained by means of the CDL-ABI can help to:

Perform diagnostics in a multidisciplinary setting;

Draw up a (cognitive) rehabilitation treatment plan;

Evaluate changes over time;

Provide information to support reintegration.

Instructions

The tool should be filled in after an extended observation period of at least one week. Please read all materials in advance of the observation period. The examination is based on the general impression of the observer during the observation period, not on an incidental observation.

The tool can be filled in by any care provider working with people with acquired brain injury. The tool should preferably be filled in by one care provider, who can consult colleagues if necessary.

The words he/she in the text refer to all genders, as appropriate.

The focus should be on behaviour that is related to cognition. So do not score problems that are caused by visual impairments or hearing difficulties or by motor problems such as hemiparesis/hemiplegia.

The CDL-ABI measures spontaneous behaviour. Please do not give instructions, evoke specific behaviour, or ask the patient how he/she experiences the problem him/herself.

Scoring

Please read all the items on the observation list before you fill in the scores so you know which cognitive problem situations are covered by the tool. The frequency of each observed behaviour and the severity of the problem caused by this behaviour should then be scored based on the behaviour during the observation period.

The frequency of the behaviour is scored on the following scale:

- Never:

This behaviour does not occur, although you have observed situations in which this behaviour could have occurred.

- Sometimes:

This behaviour occurs sometimes (1-2 times a week).

- Often:

This behaviour occurs often (several times a week, but not every day).

- Always:

This behaviour occurs always (every day).

- Not observed:

Situations in which this behaviour could have been observed did not occur in the observation period.

The severity of the problem (behaviour) is scored on the following scale:

- Not present:

The patient does not have any problems in this area.

- Mild problem:

The problem has a mild effect on the patient.

- Moderate problem:

The problem has a moderate effect on the patient.

- Severe problem:

The problem has a severe effect on the patient.

- Not observed:

Situations in which this behaviour could have been observed did not occur in the observation period.

Tick the boxes that correspond to the frequency and the severity of the observed problem. When you have scored all items, multiply the frequency score and the severity score for each item. Subsequently, total the multiplied scores for each cognitive domain.

Scoring example:

|

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the “Gewoon Bijzonder” Programme on behalf of the Organisation of Health Research and Development (ZonMw – The Netherlands; www.zonmw.nl) under grant number 845009002.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Disclosure of interests

The authors report no conflict of interests.

References

- Almanasreh, E., Moles, R., & Chen, T. F. (2019). Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15(2), 214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Árnadóttir, G. (1992). The Árnadóttir OT-ADL neurobehavioral evaluation (A-ONE): concurrent validity. In IVth European congress of ergotherapy, ostend, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Azouvi, P., et al. (2017). Neuropsychology of traumatic brain injury: An expert overview. Revue Neurologique, 173(7-8), 461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, C., & Edwards, D. F. (1993). Cognitive performance in senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: The kitchen task assessment. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 47(5), 431–436. doi: 10.5014/ajot.47.5.431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootes, K., & Chapparo, C. J. (2002). Cognitive and behavioural assessment of people with traumatic brain injury in the work place: Occupational therapists’ perceptions. Work, 19(3), 255–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwens, S. F., et al. (2008). Relationship between measures of dementia severity and observation of daily life functioning as measured with the assessment of motor and process skills (AMPS). Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 25(1), 81–87. doi: 10.1159/000111694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, R., et al. (2016). Development and validation of the nursing profession self-efficacy scale. International Nursing Review, 63(3), 455–464. doi: 10.1111/inr.12291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A.-N., et al. (2014). Computer-assisted direct observation of behavioral agitation, engagement, and affect in long-term care residents. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(7), 514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaytor, N., & Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. (2003). The ecological validity of neuropsychological tests: A review of the literature on everyday cognitive skills. Neuropsychology Review, 13(4), 181–197. doi: 10.1023/B:NERV.0000009483.91468.fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevignard, M., et al. (2000). An ecological approach to planning dysfunction: Script execution. Cortex, 36(5), 649–669. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70543-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicerone, K. D. (2005). The effectiveness of rehabilitation for cognitive deficits. Effectiveness of Rehabilitation for Cognitive Deficits, 43–58. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198526544.003.0005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicerone, K. D., et al. (2019). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Systematic review of the literature from 2009 through 2014. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(8), 1515–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare, L., et al. (2012). Awarecare: Development and validation of an observational measure of awareness in people with severe dementia. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 22(1), 113–133. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2011.640467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, J. (2020). The neuropsychiatric inventory: Development and applications. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 33(2), 73–84. doi: 10.1177/0891988719882102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domensino, A.-F., Evans, J., & van Heugten, C. (2022). From word list learning to successful shopping: The neuropsychological assessment continuum from cognitive tests to cognition in everyday life. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, N. J., et al. (2008). Conceptualizing functional cognition in stroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 22(2), 122–135. doi: 10.1177/1545968307306239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edemekong, P. F., Bomgaars, D. L., & Levy, S. B. (2017). Activities of daily living (ADLs). [PubMed]

- Fernandez, H. H., et al. (2008). Scales to assess psychosis in Parkinson's disease: Critique and recommendations. Movement Disorders, 23(4), 484–500. doi: 10.1002/mds.21875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, P. D. (2022). Clinical applications of neuropsychological assessment. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, P. D. (2022). Domains of cognition and their assessment. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengst, S. B., et al. (2019). Development and content validity of the behavioral assessment screening tool (BASTβ). Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(10), 1200–1206. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1423403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M. P., et al. (1999). Observed affect and quality of life in dementia: Further affirmations and problems. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M. P., Van Haitsma, K., & Klapper, J. (1996). Observed affect in nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 51B(1), P3–P14. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51B.1.P3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak, M. D., et al. (2004). Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Libeson, L., et al. (2020). The experience of return to work in individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI): A qualitative study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30(3), 412–429. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2018.1470987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, M. R. (1986). Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Research, 35(6), 382–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsø, K. G., et al. (2021). Assessing momentary well-being in people living with dementia: A systematic review of observational instruments. Frontiers in Psychology, 5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte, T. D., et al. (2010). Neuropsychology and the prediction of everyday functioning. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K., et al. (2007). Validity and reliability of the behavioural assessment tool for cognition and higher function (BATCH) in neuropsychiatric patients. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 41(8), 697–704. doi: 10.1080/00048670701449203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persoon, A., et al. (2011). Development of the nurses’ observation scale for cognitive abilities (NOSCA). International Scholarly Research Notices. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T., & Owen, S. V. (2007). Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 30(4), 459–467. doi: 10.1002/nur.20199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics, L. (2014). Qualtrics [software]. Qualtrics. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, A. R., & Levin, H. S. (2014). Cognitive sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Psychiatric Clinics, 37(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sireci, S. G. (1998). The construct of content validity. Social Indicators Research, 83–117. doi: 10.1023/A:1006985528729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smits-Engelsman, B., et al. (2020). Feasibility and content validity of the PERF-FIT test battery to assess movement skills, agility and power among children in low-resource settings. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09236-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spikman, J., Van der Kaaden, D., & Herben-Dekker, M. (2014). Handboek Interdisciplinaire Cognitieve Behandeling.

- Stewart, J. L., Lynn, M. R., & Mishel, M. H. (2005). Evaluating content validity for children's self-report instruments using children as content experts. Nursing Research, 54(6), 414–418. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200511000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D. L., Norman, G. R., & Cairney, J. (2015). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels, R. A., et al. (2011). Current use and barriers and facilitators for implementation of standardised measures in physical therapy in The Netherlands. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 12, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. (2016). Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. How to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research (August 10, 2016).

- Ten Brink, A., et al. (2017). De Utrechtse Schaal voor de Evaluatie van klinische Revalidatie (USER): implementatie en normgegevens. Ned Tijdschr Revalidatiegeneeskd, 39(3), 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Terwee, C., et al. (2003). On assessing responsiveness of health-related quality of life instruments: Guidelines for instrument evaluation. Quality of Life Research, 12, 349–362. doi: 10.1023/A:1023499322593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwee, C. B., et al. (2018). COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: A Delphi study. Quality of Life Research, 27, 1159–1170. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D. R. (2003). A general inductive approach for qualitative data analysis.

- Torenbeek, M., et al. (1998). Construct validation of the hoensbroeck disability scale for brain injury in acquired brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Injury, 12(4), 307–316. doi: 10.1080/026990598122610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kemp, J., et al. (2019). Return to work after mild-to-moderate stroke: Work satisfaction and predictive factors. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(4), 638–653. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2017.1313746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heugten, C., et al. (2020). An overview of outcome measures used in neuropsychological rehabilitation research on adults with acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30(8), 1598–1623. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2019.1589533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heugten, C., Groet, E., & Stolker, D. (2003). Cognitieve, emotionele en gedragsmatige gevolgen na een beroerte: Evidence-based richtlijnen voor revalidatie. Neuropraxis, 7(5), 129–139. doi: 10.1007/BF03099826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis, K., et al. (2022). Domains and measures of social cognition in acquired brain injury: A scoping review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(9), 2429–2463. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2021.1933087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, W. (2005). Toward developing new occupational science measures: An example from dementia care research. Journal of Occupational Science, 12(3), 121–129. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2005.9686555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanzadeh, V., et al. (2014). Details of content validity and objectifying it in instrument development. Nursing Practice Today, 1(3), 163–171. [Google Scholar]