Abstract

Background

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease caused by the genus, Leptospira. Leptospira interrogans is the most common genomospecies implicated in the disease. Epidemiological investigations are needed to distinguish outbreak situations or to trace reservoirs of the organisms. Current methodologies used for typing Leptospira have significant drawbacks. The development of an easy to perform yet high resolution method is needed for this organism.

Methods

In this study we have searched the available genomic sequence of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain Fiocruz L1-130 for the presence of tandem repeats [1]. These repeats were evaluated against reference strains for diversity. Six loci were selected to create a Multiple Locus Variable Number of Tandem Repeats (VNTR) Analysis (MLVA) to explore the genetic diversity within L. interrogans serovar Australis clinical isolates from Far North Queensland.

Results

The 39 reference strains used for the development of the method displayed 39 distinct patterns. Diversity Indexes for the loci varied between 0.80 and 0.93 and the number of repeat units at each locus varied between less than one to 52 repeats. When the MLVA was applied to serovar Australis isolates three large clusters were distinguishable, each comprising various hosts including Rattus species, human and canines.

Conclusion

The MLVA described in this report, was easy to perform, analyse and was reproducible. The loci selected had high diversity allowing discrimination between serovars and also between strains within a serovar. This method provides a starting point on which improvements to the method and comparisons to other techniques can be made.

Background

Leptospirosis, is the zoonotic disease caused by the spirochete Leptospira. Leptospirosis is characterised either as a febrile illness with sudden onset, or a 'flu like' illness. Patients present with chills, headaches, myalgia, and abdominal pain. In addition, patients may present with renal and pulmonary complications. It is considered an emerging infectious disease with large documented outbreaks occurring world-wide [2]. The majority of isolates detected in Queensland, Australia belong to the genomospecies, L. interrogans, with the dominant serovars being Zanoni or Australis. Typically Leptospirosis infections in Queensland are a result of occupational exposure with the majority of cases occurring in farming or animal based industries [3].

The genus Leptospira contains 17 genomospecies as shown by DNA-DNA hybridisation [4]. Under the current genotypic classification system, pathogenic and non pathogenic serovars may reside within the same genomospecies [2]. Many animals both domesticated and native serve as the reservoir for this bacterium. Leptospires are shed into the environment via the urine of these animals, where they survive in the soil or freshwater. Human infections result from contact with the contaminated soil/water or from direct contact with animals or their infectious body fluids [5].

Epidemiological investigation of this organism is important for the ability to distinguish individual cases from related cases such as in an outbreak situation. Also of importance is determining which animal is the likely common source of the infection, as containing or preventing the spread of the vector is paramount to controlling the disease.

Molecular typing methods have been described for L. interrogans including Randomly Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) [6-9], Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) [10], Arbitrarily Primed PCR (AP-PCR) [11,12] and most recently Fluorescent Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (FAFLP) [13]. Each of these methods have their disadvantages such as insufficient discriminatory power, poor inter-lab and intra-lab reproducibility, difficulties with database and dissemination of data [14]. They may also require specialised equipment such as DNA sequencers or contour-clamped homogeneous electric field electrophoresis systems. In addition leptospires have their own particular problems when using the above methods, the fastidious nature of the organism does not easily allow for the large volume of culture material required for PFGE and cultures can be quite prone to contamination with other bacteria, which may influence the accuracy of low stringency PCR methods or AFLP. As an alternative to the above methods, investigation of Variable Number of Tandem Repeats (VNTR) has been described for various organisms. These include Salmonella enterica [14,15], Staphylococcus aureus [16], Yersinia pestis [17], Mycobacterium tuberculosis [18], Francisella tularensis [19], Legionella pneumophila [20], Brucella spp. [6,21], Escherichia coli O157:H7 [22]and Borrelia spp[23]. VNTR are repeated DNA sequences of varying copy number. They are caused by slipped strand mispairing during DNA replication [24,25]. VNTRs can provide information relating to both the evolutionary and functional areas of bacterial diversity[25]. The ability to detect VNTRs in micro-organisms has been greatly enhanced by the availability of whole genomic sequences and software that can search for VNTR loci from these sequences. 1, [26,27] Once these polymorphisms are located, flanking primers can then be designed to amplify these variable length regions thus allowing differentiation of copy numbers using the size of the resultant amplicon. This can be done using standard agarose gel electrophoresis and if a higher resolution is required, fluorescent labelling and fragment sizing via a DNA sequencer can be used. VNTR is therefore applicable to a wide range of laboratories, including those which may have simple equipment such as thermal cyclers and agarose gel electrophoresis but do not have access to sophisticated equipment such as DNA sequencers. Furthermore when VNTR is applied to multiple loci as a typing scheme such as in Multiple Locus VNTR Analysis (MLVA) greater discriminatory power and more accurate determination of genetic relatedness is achieved [17,19,28,29]. Recently Majed et al [30]described a MLVA typing scheme for L. interrogans Sensu Stricto, this research highlighted the value of using VNTR as a typing scheme but was limited to the identification of serovar by comparing the size of the repeat to that of known reference strains. It should be noted that in that study several reference strains had identical VNTR patterns including serovars Australis and Bratislava, serovars Copenhageni and Icterohaemorragiae and serovars Romanica and Wolffi. It was subsequently validated against a small number of clinical isolates. In this paper, we report on the development of a MLVA scheme using novel VNTR loci selected from the sequence of a published L. interrogans genome [1] and evaluate its usefulness as a phylogenetic typing method using reference strains and clinical isolates from Far North Queensland, Australia.

Methods

Bacterial Strains

Thirty-nine reference strains of L. interrogans were obtained from the reference culture collection maintained by the WHO/FAO/OIE Collaborating Centre for Reference & Research on Leptospirosis, Brisbane, Australia (Table 1). In addition to the reference strains, ninety-eight isolates of L. interrogans serovar Australis were analysed [Additional File One]. These isolates were recovered from human and animal specimens. Human isolates were cultured using 0.2–0.5 mL of whole blood inoculated into 3 mL of semi solid Ellinghausen McCollugh Johnson Harris broth supplemented with 0.15% agar (EMJH, Difco lab, USA). These were then sub-cultured into EMJH broth within one week of receipt at the laboratory. Cultures were incubated for a further six weeks at 30°C and inspected weekly using dark ground microscopy. Positive cultures were identified using hyperimmune antisera and the Cross Agglutination Absorption Test (CAAT). 3 mm cubes of kidney or 100 μL of urine from rodents were inoculated into 3 mL semi solid EMJH media, these were incubated at 30°C for six weeks and inspected weekly using dark field microscopy. Positive cultures were identified as above. Once identified, isolates were stored in liquid nitrogen using EMJH media containing 2.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Table 1.

Leptospira interrogans reference strains used for VNTR loci selection.

| Serogroup | Serovar | Strain | Area of isolation | Source |

| Australis | Australis | Ballico | Australia | Human |

| Pomona | Pomona | Pomona | Australia | Human |

| Sejroe | Medanesis | Hond HC | Indonesia | Dog |

| Icterohaemorrhagie | Copenhageni | M20 | Denmark | Human |

| Mini | Swaijak | Swaijak | Australia | Human |

| Sejroe | Hardjo | Hardoprajitno | Indonesia | Human |

| Icterohaemorrhagie | Icterohaemorrhagie | Ictero 1 | Japan | Human |

| Autumnalis | Autumnalis | Akiyami A | Japan | Human |

| Canicola | Canicola | Hond Utrecht IV | Netherlands | Dog |

| Australis | Muenchen | Munchen C90 | Germany | Human |

| Australis | Fugis | Fudge | Malaysia | Human |

| Australis | Lora | Lora | Italy | Human |

| Autumnalis | Weerasinghe | Weerasinghe | Sri Lanka | Human |

| Bataviae | Bataviae | Swart | - | - |

| Bataviae | Paidjan | Paidjan | Indonesia | Human |

| Canicola | Benjamini | Benjamin | Indonesia | Human |

| Canicola | Binjei | Binjei | Indonesia | Human |

| Canicola | Broomi | Patane | Australia | Human |

| Djasiman | Djasiman | Djasiman | - | - |

| Icterohaemorrhagie | Gem | Simon | Sri Lanka | Human |

| Pyrogenes | Abramis | Abraham | Malaysia | Human |

| Pyrogenes | Biggis | Biggs | Malaysia | Human |

| Pyrogenes | Camlo | Lt64-67 | Vietnam | Human |

| Sejroe | Geyaweera | Geyaweera | Sri Lanka | Human |

| Pyrogenes | Zanoni | Zanoni | Australia | Human |

| Pyrogenes | Robinsoni | Robinson | Australia | Human |

| Autumnalis | Bangkinang | Bangkinang 1 | Indonesia | Human |

| Autumnalis | Carlos | C3 | Phillippines | Toad |

| Autumnalis | Mooris | Moores | Malaysia | Human |

| Bataviae | Losbanos | LT101-69 | Phillippines | Rat |

| Canicola | Sumneri | Sumner | Malaysia | Human |

| Canicola | Jonsis | Jones | Malaysia | Human |

| Djasman | Sentot | Sentot | Indonesia | Human |

| Djasiman | Gurungi | Gurung | Malaysia | Human |

| Pyrogenes | Guaratuba | An7705 | Brazil | Opossum |

| Icterohaemorrhagie | Smithi | Smith | Malaysia | Human |

| Sejroe | Wolffi | 3705 | Indonesia | Human |

| Sejroe | Ricardi | Richardson | Malaysia | Human |

| Sejroe | Haemolytica | Marsh | Malaysia | Human |

DNA Extractions

Once the cultures had reached a density equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard (1.5 × 108 cells/mL), cells were harvested by aspirating 500 μL of culture, centrifuged at 12,000 g for 4 minutes and resuspended in 200 μL of Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS). DNA was extracted using the Roche High Pure Template kit as per manufacturer's instruction.

VNTR primer design

The two chromosomes of L. interrogans Copenhageni strain Fiocruz L1-130 deposited in GenBank under accession numbers, NC005823 and NC005824 were used to detect the VNTR Loci. Analysis using the Tandem Repeat Finder (TRF) program http://tandem.bu.edu/[1,26] was used to identify potential VNTR loci. Primer Premier 5.0 (Premier Biosoft) was used to design PCR primers for amplifying the loci. Primers were designed within the flanking regions, with a theoretical melting temperature of 57°C to 60°C (Table 2).

Table 2.

PCR primers used in Study

| Primer Name | Direction | Sequence (5'-3') | Theoretical Melting Temperature (°C) |

| V8 | Forward | CAA GTG TTC GAC AAG AAT GAG | 57.4 |

| Reverse | CTC ACC GGT AGA ACG CTC TTT T | 58.4 | |

| V27 | Forward | TCG TCG GGT GAG CTA AAA TAT | 57.0 |

| Reverse | TTC TTT CGG TGG CAA GG TTT | 59.8 | |

| V29 | Forward | ATC GTT TTG GCA GTT TTT GCT | 57.7 |

| Reverse | CTA GAA AAT TCC GCG TAG GG | 57.2 | |

| V30 | Forward | AAG TAA GAT AGG TTC GGC GTT TA | 57.9 |

| Reverse | ACT TGG GTG TTA ATC GCA AAA | 57.7 | |

| V36 | Forward | TGG TTC TTG GGG TAA TTC TGT T | 58.2 |

| Reverse | CTA CCA GGA GAT TAT CAA AAC GAA | 57.9 | |

| V50 | Forward | CTT GTT GGA TCA CAA TAC GAA CTA TA | 58.4 |

| Reverse | GGTAAGGGACAAAGTAAGTGAAGC | 58.9 |

VNTR PCR amplification

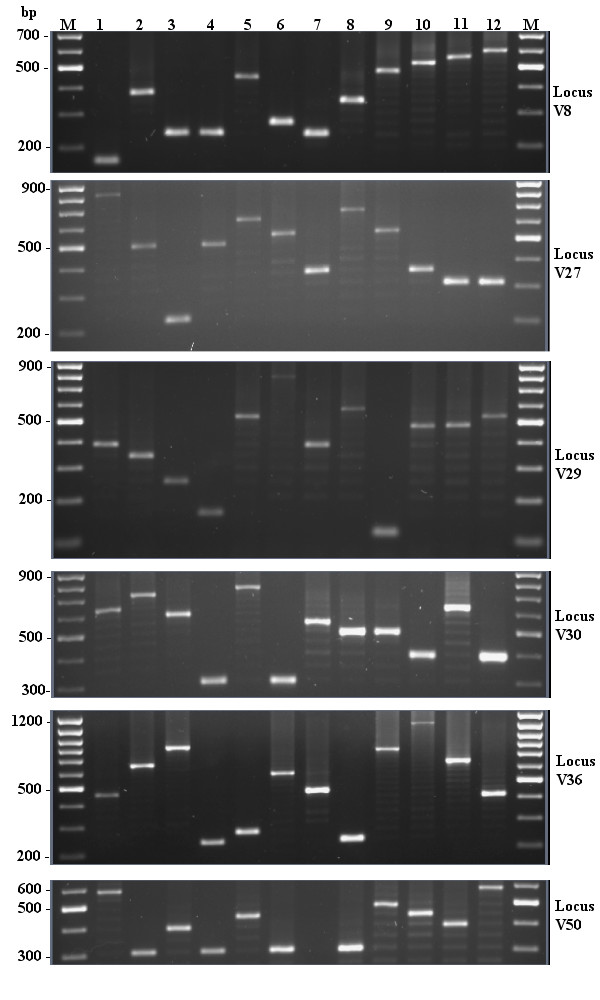

PCR amplification of the VNTR loci was performed in a total volume of 50 μL containing 1X PCR Buffer II (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), 2 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP mix (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J), 10 pmol each of forward and reverse primer (Table 2), 1 unit of Amplitaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), 2 μL of the DNA preparation and double distilled water (ddH2O) making up the volume to 50 μL. The PCRs were run on a GeneAmp 9700 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). An initial denaturation at 95°C for 9 minutes, was followed by 35 cycles of a three step cycle protocol: 94°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 60 seconds and 72°C for 60 seconds and a final extension of 72°C for 7 minutes. Each PCR product (15 μL) was resolved by electrophoresis (2 hours at 80 V) through a 2% agarose gel containing 0.5 ug ethidium bromide and buffered with 1X TBE (90 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8). Allelic sizes were estimated using a 100 bp DNA plus Ladder (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) as a size marker. Gels were visualised using UV transillumination and the images captured using the ChemiDoc XRS System (BioRad, Hercules, Calif.) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PCR products from the six selected VNTR loci of various L. interrogans reference strains. PCR products electrophoresised through a 2% agarose gel. M: 100 bp DNA Ladder plus (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania); 1, Serovar Zanoni strain Zanoni; 2, Serovar Autmnalis strain Akiyami A; 3, Serovar Canicola strain Hond Utrecht IV; 4, Serovar Pomona strain Pomona; 5, Serovar Hardjo strain Hardjoprajitno; 6, Serovar Muenchen strain Muenchen C90; 7, Serovar Weerasinghe Strain Weerasinghe; 8, Serovar Paidjan strain Paidjan; 8, Serovar Biggis strain Biggs; 9, Serovar Bangkinang strain Bangkinang 1; 10, Serovar Jonsis strain Jones.

Sequencing

The PCR products from eight selected references strains were sequenced using the same primers used to amplify the products. PCR product clean-up was performed using an enzyme digestion containing 1 μl of 10X Antarctic Phosphatase buffer (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass), 2 units of Exonuclease I (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania), 2 units of Antarctic Phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass), 7 μL of PCR product and ddH2O to the final volume of 10 μL. This mix was incubated for 20 min at 37°C follow by 5 min at 80°C to inactivate the enzymes. Sequencing was performed using 1 μL of Big Dye Terminator V3.1 ready reaction mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with 7 μL of 2.5x Applied Biosystem sequencing dilution buffer, 3.2 pmol of primer, 3 μL of PCR product and ddH2O to the final volume of 20 μL. The thermal cycling was perform according to the manufacturer's instructions with the exception of increasing the cycles to 45. The sequencing products were cleaned up using sodium acetate-ethanol precipitation before being run on an ABI-373 sequencer. The sequences were aligned and analysed using Vector NTI Suite 9 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.).

Data Analysis

Using the Quantity One 1D Analysis software package (BioRad, Hercules, Calif.), the agarose gel images were analysed and allelic sizes estimated. Allelic sizes were then converted into repeat copy numbers using Microsoft Excel software package [Additional File One], using the formula: Number of Repeats (bp) = [Fragment size (bp) – Flanking regions (bp)] / Repeat size (bp). The repeat copy numbers were then rounded down to form whole numbers. When repeat numbers were less than one, they were rounded down to zero, whilst no amplification was represented by the number ninety-nine. This created a numerical profile which was analysed as a character dataset using Bionumerics software package version 3.5 (Applied-Maths, Sint-Martens-Latern, Belgium). Clustering analysis was done using the categorical parameter and the Ward coefficient. Nei's Diversity Index of the VNTR loci was calculated from the range of alleles generated from the reference strains utilising the formula; D = 1-Σ(allele frequency)2 [31].

Results

Identification of VNTR markers

The Tandem Repeat Finder program identified 189 repeat motifs within the genome of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain Fiocruz L1-130. 186 of the repeats were identified from chromosome 1 and only three were found in chromosome 2. 53 repeats were identified as being suitable for further analysis based upon the size of the repeat, number of repeat units present and also whether the sequence was conserved within the repeats. Preliminary testing against the reference strains identified 25 loci out of the 53 that were polymorphic between different serovars. The remaining 25 loci either failed to amplify any DNA or were amplified but were monomorphic. A subset of the L. interrogans serovar Australis clinical isolates that were considered geographically unrelated was used to determine whether the 25 selected loci were also polymorphic within a serovar. Six loci were found to contain variable repeat copy numbers within a serovar and were then re-applied to the 39 reference strains. Amplification of the six loci was possible from the 39 reference strains tested with the exceptions of locus V8 from serovar Djasiman, locus V27 from serovar Swaijak and Robinsoni, locus V29 from serovars Swaijak, Canicola, Broomi, Robinsoni and Jonsis. Amplification was also not possible for locus V36 from serovars Munchen and Fugis also for Locus V50 in serovars Lora and Geyaweera. PCR amplification was attempted three times for these serovars, no amplicons were detected at each attempt. The different allele sizes were caused by the loss or addition of repeat units confirmed by the sequencing of the PCR products. Sequence data was entered into GenBank [GenBank: DQ023538 – DQ023553].

For the 39 reference strains the number of repeats in the six loci varied between no repeats in all loci up to 52 repeats in the V36 locus. The number of alleles per locus varied between six in V27 and nineteen in V36. The diversity index ranged from the lowest of 0.80 in V27 to 0.93 in V36. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Characteristic of the Six VNTR loci

| Loci | Repeat Motif | Repeat size (bp)a | Total Flanking Regions (bp)a | Repeat range (min-max) | No. of alleles | Diversity (D) |

| 8 | GGAAAACTCAACACAA CGCTCTTTATGAATCG CGTT |

36 | 124 | 0–16 | 14 | 0.88 |

| 27 | TTGTGGGAACTCTTAC AATTTGAGATTTTACA GTAAAACTTGGAAGTT GTGGGAACTCTTACAA TTTGAGATTTTACAGTA AAACTTGGAAATTGTG GGAACTCTTACAACTT GAGATTTTACAGTGGG ACTTTGAAG |

138 | 183 | 0–4 | 6 | 0.80 |

| 29 | GATTTTACAGTTAGAC TTTGAAATTGTGGGAA CTCCCACGGATTTGG |

47 | 90 | 0–17 | 14 | 0.92 |

| 30 | TCCCACATATTCAAGA TTAAACTGTAAAATTGT GATTTGTGGTAGT |

46 | 228 | 0–12 | 12 | 0.88 |

| 36 | CTTAGACTTTGTGTGA GTTCCCACATTTTAAA GTAAAA |

38 | 161 | 0–52 | 19 | 0.93 |

| 50 | AAAATGTAGGAACTAC CACAAACACTGACTTT ACAGATAAATTCTC |

46 | 106 | 012 | 9 | 0.83 |

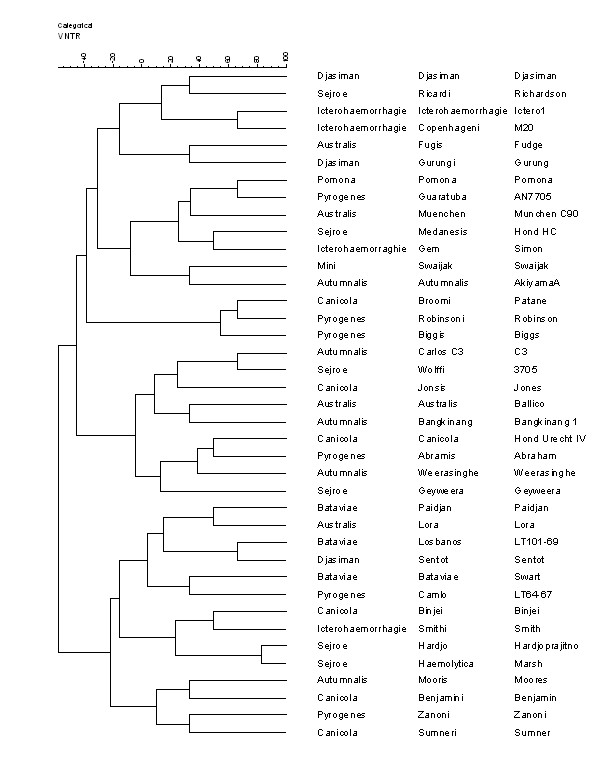

L. interrogans reference strains clustering analysis

Clustering analysis (Figure 1) positioned the reference strains into three large clusters. These clusters each contained a diverse selection of serovars with no bias towards the grouping of serogroups together, with the exception of serovar Iceterohaemorrhagie strain Ictero 1, Copenhageni strain M20, serovar Hardjo strain Hardjoprajitno and Haemolytica strain Marsh. Both of these pairs of serovars belong to the same serogroups: Icterohaemorrhagie and Sejroe respectively.

Figure 1.

Leptospira interrogans reference strains: clustering analysis using MLVA Data. Clustering analysis was done using the categorical and ward options using Bionumerics software package version 3.5 (Applied-Maths, Sint-Martens-Latern, Belgium).

L. interrogans serovar Australis clustering analysis

To further evaluate the VNTR loci selected for the MLVA, the typing scheme was applied to 98 isolates of L. interrogans serovar Australis. All six VNTR loci were amplified from all of these clinical isolates, which varied in geography of isolation and host. Clustering analysis [Additional File Two and Additional File Three] revealed three major clusters, each containing several sub-groups. Three clusters contained a mix of Rattus species and human whilst two contained canine isolates. Two of the major clusters show significant geographical distributions towards the two main townships in the area: Tully and Innisfail, whilst the remaining major cluster was more diverse in geographical distributions. As the isolates were taken over a limited timeframe, not surprisingly there was no discernable pattern in regards to the introduction or extinction of strains over time in the area.

Discussion

The MLVA assay presented was easy to perform and analyse, as it consisted of six individual PCR reactions and agarose gel electrophoresis. Selected reference strain isolates were run in tandem during the initial evaluation by different individuals to assess reproducibility, each time they displayed identical fragment sizes as determined by sequencing and agarose gel electrophoresis (data not shown). Dilutions of the template DNA were used to evaluate whether the fragment sizes were template concentration dependant. Dilutions of 1:10 and 1:100 did not effect fragment size but did result in reduced PCR product yield (data not shown). The MLVA assay was proven to be reproducible under varying laboratory conditions. The two limitations of this assay are firstly the use of agarose gel electrophoresis to separate fragments for allelic sizing, due to inherent inaccuracies of this method to size bands of close molecular weights given that the resolution is dependant on agarose composition and concentration and secondly in rounding partial repeat copy numbers to the nearest whole number to make the data analysis easier, isolates that had partial repeats were treated as if they contained whole repeats. As illustrated in Additional file 1, by simplifying the repeat copy numbers we have artificially reduced the resolution of the method and its ability to distinguish between closely related strains that may only vary by a partial repeat at one or more of the loci.

The diversity index calculated for each locus suggests that the loci selected are of highly polymorphic nature and therefore have greater discriminatory power between similar strains than loci with a lower diversity indexes would have. Whilst it has been previously reported in organisms such as Francisella tularensis [19] and Yersinia pestis [29] that higher copy repeat numbers may confer higher allelic variability, it was not demonstrated with this study. This may be due to the loci having similar repeat copy sizes (36–47 bp) with the exception of locus V27 with a repeat size of 138 bp. The lack of amplification from loci V8, V27, V29, V36 and V50 from certain reference strains may be due to sequence diversity in the flanking regions up or downstream from the repeat regions or the lack of the VNTR loci all together. Further investigations using isolates of these serovars is needed to determine whether there is sufficient diversity in the remaining loci for it to be valid as a typing method. In the study by Majed et al. [30], they noted from the dendrogram that the isolates had clustered into distinct global geographical regions. Interestingly in this study, we found that the dendrogram showed no bias towards this global geographical clustering of reference strains.

The different genomospecies of Leptospira were not used in the selection and development of the VNTR loci for this typing scheme. The basis for this decision was that the other genomospecies are considered to be significantly different from L. interrogans based upon DNA-DNA Hybridisation [32,33] and may not possess the same primer binding sites or indeed the same VNTR loci. In addition due to the use of a serologically based Leptospiral taxonomy system, several serovars belong to more than one genomospecies [32,33], thus it would be doubtful that the MLVA typing scheme described in this article would be useful in determining the genomospecies of these related serovars due to the significant genetic differences[34]

When the MLVA assay was applied to L. interrogans serovar Australis isolates collected from 1995 to 2004, the six selected loci appeared to show less diversity. This could be due to the fact that the isolates were taken from within a limited geographical area of Far North Queensland. Despite this apparent limited diversity, the phylogenetic analysis revealed several large albeit weakly linked clusters. All of these clusters contained a mixture of hosts, and it would be possible to speculate that the transmission of serovar Australis to humans in that area is via the native rodent population indigenous to that area. Another possible risk whilst not proven in Australia, is that transmission of the organism may occur via canines to humans [2]. Indeed in this study the two strains isolated from canines are genetically similar to two strains isolated from humans. Also of interest, the reference culture for serovar Australis; strain Ballico which was isolated from a patient in North Queensland in 1934, shows homology with LT958 and QHR371A a human and Rattus sordidus isolate respectively, both from the Tully region. Further investigations using MLVA of isolates, could add further detail to the depth of knowledge into the population of serovar Australis and to determine other possible transmission sources to humans.

Further improvements to this method are possible to increase both practicality and discriminatory power for typing of L. interrogans isolates. These improvements could include the use of fluorescently labelled primers and fragment analysis using a DNA sequencer to accurately assign repeat sizes. Multiplexing of the six targets would rationalise the number of PCR reactions needed to complete the MLVA and would also decrease costs in terms of reagents and labour. Improvements that could be introduced to the analysis of the data may include using an allele designation system as described by Lindstedt et al [34]. In addition to improving the method, comparisons between other molecular typing methods such as FAFLP or a sequence based typing scheme, would ultimately determine the validity of the MLVA assay as molecular epidemiology tool for L. interrogans.

The method has potential application in furthering the understanding of Leptospiral molecular epidemiology. As this method can be performed without specialised equipment, a broader range of laboratories including those in developing countries could potentially use this scheme as part of their isolate typing. This method was also easily standardised within our laboratory, with multiple users and different thermal cyclers employed to achieve the same results. This level of standisation at an inter laboratory level would allow the transfer of the method into another laboratory more effectively than that of a method that was operator or equipment specific. The simplification of MLVA data into a concise and portable numerical format as suggested in this article makes it easier to be comprehended by non-technical staff such as public health authorities. In addition, the format of allele data is similar to the allele string that is used for Multiple Locus Sequence Typing (MLST). As an alternative to using Bionumerics, software freely available on the internet such as Sequence Type Analysis and Recombinational Tests (START) http://pubmlst.org/software/analysis/[35] could be used for the phylogenetic analysis. Bionumerics was ultimately selected over START due to the advanced features of Bionumerics including evolutionary and population modelling.

Further assessment of L. interrogans isolates globally is required to confirm that the selected VNTR loci possess sufficient diversity to be used a typing scheme on an international level.

Conclusion

We have developed a novel MLVA typing scheme which is simple, robust reproducible and cost effective. The six VNTR loci chosen for this assay showed a high level of diversity between reference strains. When this method was applied to a collection of clinical isolates, it was possible to observe distant relationships between suspected reservoirs and humans. This method provides a starting point for further investigations into the molecular epidemiology of L. interrogans infections.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests

Authors' contributions

AS had primary responsibility for study design, conducting the typing work and preparation of the manuscript. MD provided laboratory support by culturing and maintaining culture collections. MS provided laboratory support by performing serological identification of isolates. LS had intellectual contributions. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Characteristics of Leptospira interrogans reference strains and serovar australis strains and allelic profiles for all strains tested.

Leptospira interrogans serovar Australis: clustering analysis of MLVA data part one.

Leptospira interrogans serovar Australis: clustering analysis of MLVA data part two.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Mr Shane Byrne for reviewing the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Andrew T Slack, Email: Andrew_slack@health.qld.gov.au.

Michael F Dohnt, Email: michael_dohnt@health.qld.gov.au.

Meegan L Symonds, Email: Meegan_symonds@health.qld.gov.au.

Lee D Smythe, Email: lee_smythe@health.qld.gov.au.

References

- Nascimento AL, Ko AI, Martins EA, Monteiro-Vitorello CB, Ho PL, Haake DA, Verjovski-Almeida S, Hartskeerl RA, Marques MV, Oliveira MC, Menck CF, Leite LC, Carrer H, Coutinho LL, Degrave WM, Dellagostin OA, El-Dorry H, Ferro ES, Ferro MI, Furlan LR, Gamberini M, Giglioti EA, Goes-Neto A, Goldman GH, Goldman MH, Harakava R, Jeronimo SM, Junqueira-de-Azevedo IL, Kimura ET, Kuramae EE, Lemos EG, Lemos MV, Marino CL, Nunes LR, de Oliveira RC, Pereira GG, Reis MS, Schriefer A, Siqueira WJ, Sommer P, Tsai SM, Simpson AJ, Ferro JA, Camargo LE, Kitajima JP, Setubal JC, Van Sluys MA. Comparative genomics of two Leptospira interrogans serovars reveals novel insights into physiology and pathogenesis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2164–2172. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.2164-2172.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:296–326. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.296-326.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe LBLSMDMHC. National Leptospirosis surveillance report number 12 January-December 2003. , WHO/FAO/OIE Collaborating Centre for Reference & Research on Leptospirosis, Queensland Health Scientific Services (QHSS), Brisbane, Australia.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, Matthias MA, Diaz MM, Lovett MA, Levett PN, Gilman RH, Willig MR, Gotuzzo E, Vinetz JM. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:757–771. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo TH, Patel BK, Smythe LD, Symonds ML, Norris MA, Dohnt MF. Identification of pathogenic Leptospira genospecies by continuous monitoring of fluorogenic hybridization probes during rapid-cycle PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3140–3146. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3140-3146.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corney BG, Colley J, Djordjevic SP, Whittington R, Graham GC. Rapid identification of some Leptospira isolates from cattle by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2927–2932. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2927-2932.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corney BG, Colley J, Graham GC. Simplified analysis of pathogenic leptospiral serovars by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:927–932. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-11-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen MA, Smits MA, Olyhoek T. Random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting for rapid identification of leptospiras of serogroup Sejroe. J Med Microbiol. 1995;42:336–339. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-5-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadass P, Meerarani S, Venkatesha MD, Senthilkumar A, Nachimuthu K. Characterization of leptospiral serovars by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:575–576. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann JL, Bellenger E, Perolat P, Baranton G, Saint Girons I. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of NotI digests of leptospiral DNA: a new rapid method of serovar identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1696–1702. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1696-1702.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Biswas D, Vijayachari P, Sugunan AP, Sehgal SC. A 22-mer primer enhances discriminatory power of AP-PCR fingerprinting technique in characterization of leptospires. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:1203–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perolat P, Merien F, Ellis WA, Baranton G. Characterization of Leptospira isolates from serovar hardjo by ribotyping, arbitrarily primed PCR, and mapped restriction site polymorphisms. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1949–1957. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1949-1957.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayachari P, Ahmed N, Sugunan AP, Ghousunnissa S, Rao KR, Hasnain SE, Sehgal SC. Use of fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism for molecular epidemiology of leptospirosis in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3575–3580. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3575-3580.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramisse V, Houssu P, Hernandez E, Denoeud F, Hilaire V, Lisanti O, Ramisse F, Cavallo JD, Vergnaud G. Variable Number of Tandem Repeats in Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica for Typing Purposes. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5722–5730. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5722-5730.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Lee MA, Ooi EE, Mavis Y, Tan AL, Quek HH. Molecular typing of Salmonella enterica serovar typhi isolates from various countries in Asia by a multiplex PCR assay on variable-number tandem repeats. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4388–4394. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4388-4394.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabat A, Krzyszton-Russjan J, Strzalka W, Filipek R, Kosowska K, Hryniewicz W, Travis J, Potempa J. New method for typing Staphylococcus aureus strains: multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis of polymorphism and genetic relationships of clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1801–1804. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1801-1804.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adair DM, Worsham PL, Hill KK, Klevytska AM, Jackson PJ, Friedlander AM, Keim P. Diversity in a variable-number tandem repeat from Yersinia pestis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1516–1519. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1516-1519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frothingham R, Meeker-O'Connell WA. Genetic diversity in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex based on variable numbers of tandem DNA repeats. Microbiology. 1998;144 ( Pt 5):1189–1196. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow J, Smith KL, Wong J, Abrams M, Lytle M, Keim P. Francisella tularensis strain typing using multiple-locus, variable-number tandem repeat analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3186–3192. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3186-3192.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourcel C, Vidgop Y, Ramisse F, Vergnaud G, Tram C. Characterization of a tandem repeat polymorphism in Legionella pneumophila and its use for genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1819–1826. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.1819-1826.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker BJ, Ewalt DR, Halling SM. Brucella 'HOOF-Prints': strain typing by multi-locus analysis of variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) BMC Microbiol. 2003;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noller AC, McEllistrem MC, Pacheco AG, Boxrud DJ, Harrison LH. Multilocus variable-number tandem repeat analysis distinguishes outbreak and sporadic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5389–5397. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5389-5397.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow J, Postic D, Smith KL, Jay Z, Baranton G, Keim P. Strain typing of Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii by using multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4612–4618. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4612-4618.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzymek M, Lovett ST. Instability of repetitive DNA sequences: the role of replication in multiple mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8319–8325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111008398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belkum A, Scherer S, van Alphen L, Verbrugh H. Short-sequence DNA repeats in prokaryotic genomes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:275–293. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.275-293.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://tandem.bu.edu/

- Keim P, Price LB, Klevytska AM, Smith KL, Schupp JM, Okinaka R, Jackson PJ, Hugh-Jones ME. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis reveals genetic relationships within Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2928–2936. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.10.2928-2936.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevytska AM, Price LB, Schupp JM, Worsham PL, Wong J, Keim P. Identification and characterization of variable-number tandem repeats in the Yersinia pestis genome. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3179–3185. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3179-3185.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majed Z, Bellenger E, Postic D, Pourcel C, Baranton G, Picardeau M. Identification of variable-number tandem-repeat loci in Leptospira interrogans sensu stricto. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:539–545. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.539-545.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir BS. Genetic data analysis: methods for discrete population data analysis. Sunderland, Mass., Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1990. pp. 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Feresu SB, Steigerwalt AG, Brenner DJ. DNA relatedness of Leptospira strains isolated from beef cattle in Zimbabwe. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49 Pt 3:1111–1117. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-3-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner DJ, Kaufmann AF, Sulzer KR, Steigerwalt AG, Rogers FC, Weyant RS. Further determination of DNA relatedness between serogroups and serovars in the family Leptospiraceae with a proposal for Leptospira alexanderi sp. nov. and four new Leptospira genomospecies. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49 Pt 2:839–858. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstedt BA, Vardund T, Aas L, Kapperud G. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeats analysis of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium using PCR multiplexing and multicolor capillary electrophoresis. J Microbiol Methods. 2004;59:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley KA, Feil EJ, Chan MS, Maiden MC. Sequence type analysis and recombinational tests (START) Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1230–1231. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characteristics of Leptospira interrogans reference strains and serovar australis strains and allelic profiles for all strains tested.

Leptospira interrogans serovar Australis: clustering analysis of MLVA data part one.

Leptospira interrogans serovar Australis: clustering analysis of MLVA data part two.