Abstract

The weeks following an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization are known to be the highest-risk time for suicide. Interventions are needed that are well-matched to the dynamic nature of suicidal thoughts and easily implementable during this high-risk time. We sought to determine the feasibility and acceptability of a novel registered clinical trial that combined three brief in-person sessions to teach core cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) skills during hospitalization followed by smartphone-based ecological momentary intervention (EMI) to facilitate real-time practice of the emotion management skills during the 28 days after hospital discharge. Results from this pilot study (N=26) supported some aspects of feasibility and acceptability. Regarding feasibility, 14.7% of all screened inpatients met study eligibility criteria. Half (50.3%) of those who were ineligible were ineligible because they were not part of the population for whom this treatment was designed (e.g., symptoms such as psychosis rendered them ineligible for the current study). Those who were otherwise eligible based on symptoms were primarily ineligible due to inpatient stays that were too short. Nearly half (48%) of study participants did not receive all three in-person sessions during their hospitalization. Among enrolled participants, rates of engagement with the smartphone-based assessment and EMI prompts were 51.47%. Regarding acceptability, quantitative and qualitative data supported the perceived acceptability of the intervention, and provided recommendations for future iterations. Well-powered effectiveness (and effectiveness-implementation) studies are needed to determine the effects of this promising and highly scalable intervention approach.

Keywords: Ecological momentary intervention, suicide, inpatients, smartphone

Suicide risk is highest immediately following discharge from inpatient psychiatric care (Chung et al., 2017). One possible contributor to this risk is poor continuity of care that does not help extend the skills learned during inpatient care out into the real world post-discharge. Despite this, relatively few interventions have been developed specifically for the post-discharge period. Moreover, the interventions that do exist have overall shown only small effects (Fox et al., 2020).

Limitations of Existing Interventions for STBs

One reason for the overall weak effects of existing psychological interventions for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs), including those delivered after hospital discharge, is that the typical modes of intervention delivery are not well-matched to the dynamic phenomena of STBs (Coppersmith et al., 2022). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data show that suicidal psychiatric inpatients often go from not thinking about suicide to very intense suicidal thoughts in extremely short periods of time (e.g., hours) (Halbesleben et al., 2017; Kleiman et al., 2017). In contrast, the majority of existing interventions are delivered in traditional weekly formats, with little to no contact or support between these sessions. For individuals who do consistently attend psychotherapy, it can be difficult to remember and apply the skills learned in therapy during the highly distressing period leading up to and during a suicidal crisis. Other barriers including limited availability of trained providers, cost and time demands, transportation problems, and stigma may be especially relevant during the often chaotic transition period from a contained hospital environment to “real-world” stressors that may have contributed to the suicidal crisis precipitating hospitalization in the first place (Schechter et al., 2016).

Promise of Mobile Health Interventions for STBs

mHealth apps (like ecological momentary interventions; EMI) are especially promising to address the aforementioned barriers to treatment access and may boost the effectiveness of interventions like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; Lindhiem et al., 2015) forms of which have recently demonstrated positive (albeit small) effects on STBs (Büscher et al., 2020; D’Anci et al., 2019; Tarrier et al., 2008). The potential to access support through smartphones easily, quickly, and frequently may be well-suited to the dynamic nature of suicide risk. For example, an individual may go days without needing much support, but then have a span of a few hours in which distress and suicidal thinking escalate, and immediate support or help practicing skills is urgently needed. Thus, EMIs that provide support during people’s everyday lives may be well-matched to the phenomena of STBs. Given this, we developed and tested a novel smartphone-based intervention (consisting of brief in-person sessions followed by EMI for the remainder of the inpatient period and four weeks post-discharge) for suicidal psychiatric inpatients.

Rationale/Overview of Intervention Content

The EMI content is based on the Unified Protocol for the Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP; Barlow et al., 2011, 2018). The UP is an evidence-based, modular transdiagnostic CBT protocol designed to be applicable across a range of emotional disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression), and conditions with the same functional mechanisms as emotional disorders: frequent and intense negative affect, coupled with aversive reactions to and attempts to avoid or escape affect. Though primarily tested in patients with anxiety and depressive disorders (Barlow et al., 2017; Sakiris & Berle, 2019), preliminary data support the feasibility and acceptability of the UP for targeting STBs (Bentley et al., 2020, In press). Beyond preliminary data, there are several reasons why the skills-based UP may be a promising intervention. First, the UP addresses functional mechanisms that maintain intense, frequent negative affect. Intense negative affect plays a prominent role in the emergence and maintenance of STBs (Abramson et al., 2000; Baumeister, 1990; Beck, 1975; Joiner, 2005; Linehan, 1993; Maltsberger, 2004). Second, STBs can be conceptualized as efforts to avoid or escape aversive internal states (Bentley et al., 2021), and thus, tend to serve similar functions to the maladaptive, avoidant responses that maintain emotional disorders (i.e., relief from intolerable negative affect). UP strategies might be especially effective in targeting STBs in individuals for whom STBs are maintained by affect dysregulation (Coppersmith et al., 2023; Kleiman et al., 2018). Third, the core UP skills modules – mindfulness, cognitive flexibility, and changing emotional behaviors – exist in other evidence-based CBT interventions designed specifically for STBs (Brown et al., 2005; Linehan, 1993), so there is a precedence for their use when treating suicidal individuals.

This intervention provided an abbreviated version of three of the UP’s core skills for adaptive emotional responding (anchoring in the present, thinking flexibly, and changing emotional behaviors) in 30–45 minute in-person sessions on the inpatient unit. During each session, after a didactic presentation and interactive discussion about the content, the study therapist guided the participant using the EMI to practice the skill they had learned. Participants were provided and encouraged to read a workbook that summarized the session material. Following each session, participants began receiving EMI prompts to practice their skills.

Current Study

Our prior work from this study (Bernstein et al., 2022) shows that the intervention was associated with short-term reductions in negative emotion in the time immediately before to the time immediately after using the EMI. Here, we considered aspects of feasibility including study recruitment, delivering the intervention sessions, and responding to smartphone-based EMI skills practice exercises. We considered acceptability from patients’ perspectives, using quantitative and qualitative assessments. Understanding the acceptability and feasibility is crucial when testing any type of new intervention like this one. With any new intervention, there is often an emphasis on efficacy (how the intervention works under ideal conditions) over effectiveness (how the intervention works in the real world). As there is a move from efficacy trials to effectiveness and then finally implementation, it is important to know what types of barriers, if any, may hinder an effective treatment from being implemented in a clinical setting.

Participants

Participants for this IRB-approved (Harvard IRB 18–0855) registered clinical trial (NCT03950765) were recruited from the adult inpatient psychiatry service at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Inclusion criteria focused on appropriateness for structured psychological treatment and ability to be in the study and were: (1) admission due to severe suicidal thinking or suicide attempt, (2) willingness to provide a collateral contact (used in the case of imminent suicide risk), (3) access to a compatible iOS or Android smartphone (nearly all phones produced in the past five years were compatible), (4) absence of any factor that would preclude the capacity to consent (e.g., current psychosis or mania, drug withdrawal).

Procedures

Recruitment.

A study research assistant (JSM) attended the morning meeting for unit clinical staff where new admissions from the prior day were reviewed. If a new admission was potentially eligible, the research assistant would review pertinent information about the patient (e.g., electronic health record) to verify eligibility. At least one member of the study leadership team (EMK or KHB) would confirm eligibility before a clinical staff member (MBS or SB) gave final permission to approach the patient. Once approved, the study research assistant would ask a member of the nursing staff to assess the patient’s interest in being in the study. All visits were conducted within a 3-hour window in the late afternoon (3:00–6:00PM) to avoid interfering with routine clinical programming.

Consent and enrollment.

Eligible/interested participants first completed an informed consent process and baseline measures assessing demographics, history of STBs, and other psychological constructs. Participants were then guided through the process of downloading the EMA/EMI app (LifeData).

In-person sessions.

Within the first few days after enrollment, participants completed up to three sessions with a study clinician (KHB, RFG, KLZ, or ENK). One session was completed per day over three consecutive days, though this was flexible depending on participants’ clinical needs/schedules and study clinician availability. In some cases, two sessions were completed back-to-back with a brief break in between. During these sessions, participants were introduced to the skills and shown how to use the smartphone app-based EMI for skills practice. See Table 1 for an overview of the session content.

Table 1.

Overview of the treatment modules

| Session | Description |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Anchoring in the present | Participants learned and practiced “anchoring in the present”—a strategy designed to foster present-focused awareness of emotional experiences. First, participants practiced breaking down their emotions into three components: thoughts, physical sensations, and behaviors. Then, the implications of focusing on one’s present experience (versus past events or future possibilities) when emotion begins to build was discussed. Last, the study clinician presented the four concrete steps of anchoring in the present: using a cue, doing a “three-point check” (of thoughts, physical sensations, behaviors/urges), assessing if one’s thoughts/physical sensations/behaviors are in line with the present, and if not, gently bringing one’s attention to the here and now. |

| Thinking flexibly | The session first involved highlighting the important role that thoughts play in our overall emotional experience (e.g., influencing how we feel and act), as well as the tendency to interpret situations automatically and over time, fall into unhelpful thought patterns. The concept of “thinking flexibly” was introduced as a way to generate alternative, more balanced thoughts or interpretations, and a series of questions for evaluating unhelpful automatic thoughts and generating alternatives was presented. |

| Changing emotional behaviors | In the session, the notion that emotions drive us to act in certain ways that can be helpful or maladaptive depending on the context was introduced. Participants identified their “go-to” unhelpful emotional behaviors, and corresponding short- and long-term effects. The utility of acting alternatively to emotional behaviors in order to make emotions less overwhelming was discussed, and participants were asked to brainstorm realistic “alternative actions” spanning a few different categories (e.g., acting opposite to avoidance, physical activity, taking steps to prioritize their safety) corresponding to their unhelpful emotional behaviors. |

Inpatient monitoring period.

Immediately after enrollment, participants began the smartphone monitoring portion. Each weekday, the study research assistant (JSM) would visit the participant to check in to see if there were any problems with study. At the end of their inpatient period, participants completed a discharge assessment.

Post-discharge monitoring period.

For the 28 days post-discharge, participants continued to complete EMI.i At the end of the monitoring period, participants were asked to complete a brief end-of-study survey.

EMA and EMI delivery.

Beginning from the day of enrollment, participants were sent six prompts to complete EMAs (3 of which contained EMI), hosted on Qualtrics and delivered using LifeData.ii The prompts were delivered at random times in pre-specified windows. Three prompts (at random) were assessment (i.e., EMA) only. EMAs assessed negative affect or cognitive-affective states shown to be associated with STBs (e.g., hopeless, agitated) and suicidal thoughts. The other three prompts (EMA/EMI) first presented EMA items, then presented an opportunity to practice one of the three skills (chosen at random), and then presented the EMA items again. This allowed us to assess pre-post-EMI changes in real time. In some cases, the randomly chosen EMA/EMI prompt would have included a skill not yet introduced to the participant (i.e., because they had not yet had that in-person session). When this occurred, the software was programmed to deliver an EMA-only prompt instead. Thus, the six prompts each day could have ranged from zero EMA/EMI and six EMA to three EMA/EMI and three EMA. Participants could self-initiate a skills exercise and could choose which skill they wanted to practice or have the platform choose one at random.

Compensation.

Participants could earn up to $250 in Amazon.com gift cards. They were paid $0.50 per EMA (but not the EMIs) and given a $2 bonus for completing 4+ EMAs per day. They were paid $15 for completing the end-of-study survey.

Assessments of Feasibility

Recruitment.

We were interested in (1) the proportion of participants we screened (based on clinical staff meeting and EHR review) eligible for the study treatment and (2) what proportion of eligible participants would be interested in receiving the intervention package. We report descriptive data on the number of participants who were screened, who were eligible, and who participated. For participants who were screened but not eligible (or eligible but not interested), we report greater detail about why participants were not eligible/interested than is typically seen on a CONSORT diagram, given that these reasons are likely relevant for understanding the feasibility of this new intervention package. Specifically, it was important to disentangle reasons that a made patients ineligible because (1) they were not part of the population for whom the intervention was designed, (2) they would not be eligible for the treatment in the context of the research study (e.g., due to factors that would interfere with their ability to consent) and (3) they would not want to engage with the fully-deployed treatment, even outside the context of a research study.

Number of in-person sessions received.

We were interested in whether it would be feasible to deliver a study intervention package that involves three in-person sessions during an inpatient stay (mean length of stay in this sample = 8.89 days [SD=4.51]). Recognizing this was not always possible (e.g., due to patient scheduling, study clinician availability, unanticipated early discharges), clinicians in some cases presented two skills in one day and some study participants did not receive some (or in one case, any) sessions. To address this, we report the number of in-person sessions each participant received and how often sessions included one or more of the three emotion management skills.

EMA and EMI response rates.

Given that the overall number of potential EMA-only vs. EMA/EMI prompts could vary each day (always totaling six, after the first day), we report both the raw number of EMA-only and EMA/EMI prompts completed each day and percentage of possible prompts. Where possible, we report on all activities (EMA-only, EMA/EMI, and self-initiated skills practice exercises) as well as combined rates of EMA-only and EMA/EMI.

Assessments of Acceptability

Quantitative assessment.

To assess acceptability of the EMI at discharge and end-of-study, we used a modified version of the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS; Stoyanov et al., 2015), which assesses the quality of mobile health apps. Our version, shortened to reduce burden, included measures of: engagement, functionality, visual aesthetics, quality of information, subjective quality. It also included questions on the EMI’s ability to address the awareness of the importance of managing emotions, knowledge of how to manage emotions, attitudes towards managing emotions, intention to change emotions, and perceived likelihood of increasing ability to manage emotions. All items on the were on a 1–5 scale with higher scores indicating better acceptability. We also asked participants to give an overall rating of on a 1 (not helpful at all) to 10 (extremely helpful) scale of (1) the sessions’ ability to teach them to manage their emotions and (2) the EMI’s ability to access and practice the skills learned in therapy. Question 1 was given at discharge, question 2 was given at discharge and end of study.

Qualitative assessment.

We asked open-ended questions about participants’ experiences relating to the acceptability of skills sessions and EMI. Questions were rationally derived by the authors (described in results) and embedded in the discharge and end-of-study survey. Answers were coded using Directed Content Analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), a deductive approach aiming to corroborate or extend existing understandings of experience. Participants’ answers were grouped by question, reviewed, and codes characterizing the manifest content contained in each answer (e.g., “No changes needed”) were applied.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

We consented 26 participants to reach our final analyzed sample of 25 participants. One participant’s phone broke shortly after the consent and did not get a replacement before discharge, so did not complete the study. The final sample was 56% female and 44% male. The average age was 33.48 years (SD=13.84 years, range 19–63). 64% of the sample was White, 20% was Asian, 8% was Black/African American, and the remaining 8% were of another or multiple ethnicities. 16% of the sample was Hispanic or Latinx.

Feasibility

Recruitment.

Between the end of July 2019 and the beginning of March 2020 (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic), we screened 292 patients, 249 (85.3%) of whom were not eligible. Of those not eligible, 50.4% were not eligible because they were not part of the population for whom the treatment was designed: (1) suicide risk not meeting severity threshold (24.3%), (2) diagnosis involving psychosis or mania or current psychosis/mania (16.1%), and (3) cognitive impairment (10.0%). Other reasons included: length of remaining stay being too short to participate (24.5%) not fluent in English (9.2%). The remaining participants (15.9%) were ineligible for various other reasons (<2% of patients were ineligible for each reason), including not having a smartphone with them, currently enrolled in another study, or the clinical staff deemed the patient to be unable to engage with structured psychological treatment.

Of the 43 who were eligible for the study, 26 (60.5%) agreed to participate. Of the 17 who declined participation, 12 (70.5%) were not interested or did not want to participate in study procedures, and 2 (11.7%) did not believe they would be able to use a treatment focused on emotion management, and the remainder did not specify a reason.

Number of in-person sessions received.

52% of participants (n=13) received all three sessions, 7 (28%) received two sessions, 4 (16%) received one session, and one participant received no sessions. In all cases, not receiving sessions during inpatient care was related to being discharged before the sessions could be completed. 12 participants (48%) received more than one of the skills on the same day.

Response rates.

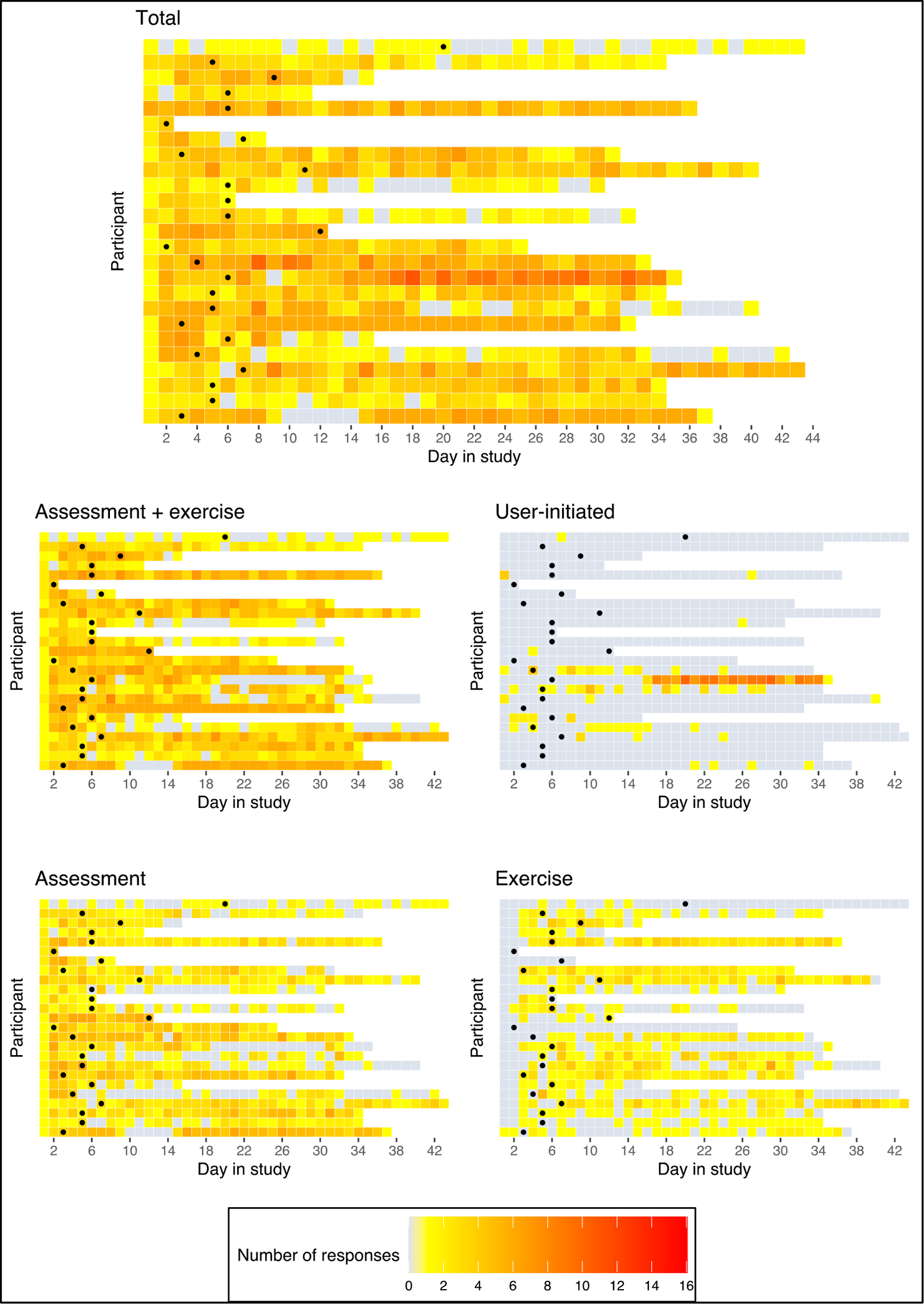

Figure 1 and Table 2 shows response rates by activity type (EMA-only, EMA/EMI, and self-initiated skills practice) as well as number of days in the study by study period (inpatient vs. post-discharge). Participants completed a total of 2,437 prompts and self-initiated exercises. Of the 2,437 responses, 2,199 of were prompted EMA or EMA/EMIs, yielding a response rate of 51.47%. There was a significant but small decrease in the number of EMAs and EMA/EMIs completed each day (IRR=0.9947, 95% CI=.9906, .9989, p=.031). When examining EMA-only and EMA/EMI separately, we only saw the decrease throughout the study for EMA-only (IRR=0.9886, 95%CI= 0.9835, 0.9938, p<.001) but not EMA/EMI (IRR=1.0060, 95%CI=0.9990, 1.0130, p=.095). On average, participants completed 20.77 days of data collection during the post-discharge period before no longer submitting data. Three participants did not complete any EMA/EMI after discharge.

Figure 1. Overview of compliance throughout the study, by participant and activity.

Note: Data are shown from first to last day of data provided. White squares = study period ended or participant stopped providing data. Grey squares = day between first and last day of study where no data were provided. Square with dot = day of discharge from inpatient care. Maximum possible assessment + exercise prompts is 6/day. The scale goes to 16 because participants could self-initiate the exercises as much as they wanted.

Table 2.

Response rates across all study activities

| Activity |

Total | Total Possible | Response Rate (sample average) | Response Rate (range) | M (SD) per person |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment and skills practice exercise completion | |||||

|

| |||||

| All (self-initiated + assessment + exercise) | 2,437 | -- | -- | -- | 113.96 (1.63) |

| Assessment + exercise | 2,199 | 4,272 | 51.47% | 11.1% – 89.6% | 87.96 (1.56) |

| Assessment only | 1,464 | 2,972 | 49.3% | 16.6% – 93.8% | 58.56 (1.32) |

| Exercise only | 735 | 1,305 | 56.3% | 0.00% – 92.1% | 29.40 (0.81) |

| Days in study | |||||

| Total days (inpatient + post-discharge) | 712 | -- | -- | -- | 27.38 (13.79) |

| Total full days inpatient | 146 | -- | -- | -- | 5.84 (3.05) |

| Total full days post-discharge before discontinuing | 540 | -- | -- | -- | 20.77 (13.36) |

Note: Total number of possible surveys was derived by multiplying the number of days in the study (inpatient + post-discharge, adjusting for those who stopped submitting surveys ) × 6 (surveys per day) × 26 (total number of participants). “Full” days indicates that we did not include the discharge day in either the inpatient or post-discharge calculations, but it is included in the total days.

Acceptability

Quantitative assessment.

Table 3 shows the MARS subscales at each assessment and Hedge’s g reflecting change from discharge to end of the study. The mean for all MARS subscales was >3.5. Most MARS subscales showed a small decrease from discharge to end-of-study (g range −.29 to −.49), indicating slightly reduced acceptability. The average score at discharge assessing the intervention’s ability to help participants manage their emotions was 7.95 out of 10 (SD=1.56). The average score assessing the EMI’s ability to help participants access and practice the skills learned in therapy was and 8.15 (SD=1.56) at discharge and 7.42 (SD=2.14) at end of study.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for MARS

| Subscale/item | Discharge Assessment (n=22) | End of Study Assessment (n=17) | g | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rel | M | SD | Range | Rel | M | SD | Range | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Engagement | .46 | 3.58 | 0.65 | 2.00 – 4.50 | .83 | 3.37 | 0.78 | 2.00 – 4.50 | −.29 |

| App is interesting | 3.90 | 0.79 | 2.00 – 5.00 | 3.79 | 0.71 | 2.00 – 5.00 | −.14 | ||

| App is interactive | 3.26 | 0.81 | 1.00 – 5.00 | 2.95 | 0.97 | 1.00 – 4.00 | −.35 | ||

| Functionality (single item) | -- | 4.15 | 0.67 | 3.00 – 5.00 | -- | 4.21 | 0.79 | 2.00 – 5.00 | .08 |

| Aesthetics | .49 | 3.95 | 0.60 | 2.50 – 5.00 | .81 | 3.71 | 0.77 | 2.00 – 5.00 | −.34 |

| Rating of app layout | 4.10 | 0.72 | 3.00 – 5.00 | 3.79 | 0.92 | 2.00 – 5.00 | −.37 | ||

| Rating of visual appeal | 3.80 | 0.77 | 2.00 – 5.00 | 3.63 | 0.76 | 2.00 – 5.00 | −.22 | ||

| Quality of information | .24 | 4.27 | 0.43 | 3.33 – 5.00 | .67 | 3.97 | 0.72 | 2.50 – 5.00 | −.49 |

| Content well written/relevant | 4.05 | 0.60 | 3.00 – 5.00 | 3.79 | 0.71 | 2.00 – 5.00 | −.39 | ||

| Content comprehensive but concise | 4.35 | 0.81 | 3.00 – 5.00 | 4.16 | 0.96 | 2.00 – 5.00 | −.21 | ||

| Visual explanation of concepts clear and logical | 4.40 | 0.50 | 4.00 – 5.00 | 4.21 | 0.54 | 3.00 – 5.00 | −.36 | ||

| Subjective app quality | .65 | 3.70 | 0.91 | 1.00 – 5.00 | .81 | 3.32 | 1.07 | 1.00 – 5.00 | −.38 |

| Would you recommend app to people who might benefit from it? | 3.50 | 1.19 | 1.00 – 5.00 | 3.68 | 1.20 | 1.00 – 5.00 | .15 | ||

| How often would you use app in the next 12 months if relevant to you? | 3.90 | 0.91 | 1.00 – 5.00 | 2.95 | 1.31 | 1.00 – 5.00 | −.83 | ||

| Perceived impact of the app on managing emotions | .82 | 4.09 | 0.55 | 3.17 – 5.00 | .91 | 4.04 | 0.76 | 2.67 – 5.00 | −.07 |

| Awareness of the importance of managing your emotions | 4.30 | 0.66 | 3.00 – 5.00 | 4.16 | 0.83 | 3.00 – 5.00 | −.19 | ||

| Knowledge and understanding of how to manage your emotions | 4.10 | 0.79 | 3.00 – 5.00 | 3.95 | 0.91 | 2.00 – 5.00 | −.18 | ||

| Attitudes toward improving how you manage your emotions | 3.95 | 0.76 | 2.00 – 5.00 | 4.05 | 0.91 | 2.00 – 5.00 | .12 | ||

| Intention and motivation to manage your emotions | 4.10 | 0.64 | 3.00 – 5.00 | 4.05 | 0.85 | 2.00 – 5.00 | −.06 | ||

| Encourage further help seeking for managing your emotions | 3.90 | 0.85 | 2.00 – 5.00 | 4.00 | 1.05 | 2.00 – 5.00 | .10 | ||

| Increase managing your emotions | 4.20 | 0.62 | 3.00 – 5.00 | 4.05 | 0.78 | 3.00 – 5.00 | −.21 | ||

Spearman-Brown split-half reliability was used for reliability given that it is most appropriate for two-item scales (Eisinga et al., 2013). Scale = 1 to 5.

Qualitative assessment.

Table 4 shows questions that participants were asked, the proportion of answers that received each code, and example quotes. Most participants reported finding the sessions helpful. Half of the participants had no specific changes they would make,. Nearly one-third wished for additional and/or more varied content or activities. Participants reported that the EMI prompts helped them practice skills and reflect on their thoughts/emotions, tracked and/or validated progress, or reminded them they had skills they could use. Three-quarters of participants also reported finding at least one aspect of the prompts annoying (e.g., redundant, coming too late at night). Nearly two-thirds advocated for either more variety in questions/content or improvements to app aesthetics.

Table 4.

Qualitative assessment of skills sessions and EMI prompt acceptability

| Code applied to answers | % | Example quote |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1. What did you like or dislike about the modules/sessions? (n=17 total responses) | ||

|

| ||

| Helpful skills/content | 52.9% | I liked the way the cycles of pain that negative thinking induces were broken down. |

|

| ||

| Nothing that I disliked | 41.7% | There is nothing in particular that I disliked about the modules and sessions. |

|

| ||

| 2. What do you wish could have been changed or added in the sessions? (n=17) | ||

|

| ||

| No changes needed | 52.9% | I wouldn’t change the program I think it was very useful very helpful in my predicament. |

|

| ||

| Add examples of how to use skills in crisis | 17.6% | Perhaps some more examples or how and when the skills can be applied in a breakdown or crisis moment could be helpful. |

|

| ||

| Change the modality of sessions | 17.6% | The clinician was great but I still like the old fashion way of therapy then putting it on a tablet. |

|

| ||

| Add more varied content/activities | 11.7% | I would have added more activities maybe, like the first session that was a little bit more clear than the others. |

| Other | 5.8% | More privacy |

|

| ||

| 3. What was the most helpful component about the daily prompts when practicing the skills you learned in the hospital? (n=14) | ||

|

| ||

| Practice/reflect | 35.7% | It was just a consistent reminder to check in with myself and to practice some therapeutic techniques. |

|

| ||

| The skills themselves | 21.4% | Alternatively thinking helped me the most. |

|

| ||

| Tracked changes/progress | 14.3% | The daily questions about my emotions in general, it helped me a lot to see the difference in my emotions. |

|

| ||

| Reminded me I have skills | 14.3% | Most helpful was reminding me I have skills that can lower my anxiety and or depression. |

|

| ||

| Other | 14.3% | The fact that they were very descriptive and clear about what to do and the frequency that the prompts appeared. |

|

| ||

| 4. Are there components of the daily prompts you feel like were annoying or unnecessary? (n=16) | ||

|

| ||

| Yes, too redundant and/or frequent | 50.0% | The surveys were redundant. |

|

| ||

| Nothing annoying/unnecessary | 25.0% | No. |

|

| ||

| Yes, other | 25.0% | Only when the prompts came in after midnight. That’s a little annoying. |

|

| ||

| 5. What do you wish could have been changed or added to any part of this study? (n=15) | ||

|

| ||

| Add more variety | 46.6% | maybe more variety in the questions and approach to the patient. |

|

| ||

| No changes needed | 20.0% | I think it’s fine the way it is, it’s pretty straightforward. |

|

| ||

| Improve aesthetics of app | 20.0% | More images. |

|

| ||

| More personalized features | 13.3% | I wish there was a place to journal my feelings. |

Note. Questions 1 and 2 were asked at discharge, questions 3–5 were asked at the end of the study. % proportion of answers that contained content relating to the code.

Discussion

We examined feasibility and acceptability of a novel intervention, consisting of brief in-person sessions followed by smartphone-based EMI, for managing emotional distress among suicidal psychiatric inpatients. Regarding feasibility, we found that about half of participants were able to receive all three in-person sessions before discharge. Engagement with the EMI component was acceptable, with >50% of prompted exercises completed. Participants found the intervention acceptable while providing valuable recommendations, namely incorporating more variety and improving app aesthetics. Although these findings are promising, we also found a relatively high rate (roughly 40%) of otherwise eligible participants did not wish to participate in the study. Below, we address these key findings in more detail.

Feasibility

Recruitment.

>80% of patients screened were not eligible for or ultimately enrolled in the study; however, this does not necessarily reflect that the intervention itself was not feasible for its target recipients. >50% of those who were ineligible were patients for whom the intervention package was not designed (e.g., they were not suicidal). This reflects the makeup of this particular unit, which treats a wide range of patients, including many who were not necessarily admitted due to suicide risk. Nearly 25% of those who were ineligible were not able to participate in the study because their length of hospitalization was too short for all study activities to take place. In a purely clinical context, however, the intervention could begin much sooner. Nearly 40% of eligible participants declined the study, however, possibly questioning the feasibility (and to an extent, acceptability) of the intervention. However, it is not clear how many of those who declined may have been interested in the intervention if it were not part of a study.

Number of in-person sessions received.

Just under half of participants were unable to receive all three in-person sessions. Almost half of participants received more than one skill in a single session. Although presenting multiple skills per session is feasible, this faster pace of delivering content may not be ideal for all patients. One way to address this concern, which our team is currently pursuing, is to use telehealth to deliver some content after discharge. This may allow better continuity of care across the inpatient to outpatient transition. It is important to note that the issues we faced in making sure participants received all three sessions are likely due to the context of conducting a research trial and would be less relevant to routine inpatient care.

EMA/EMI response rates.

Participants completed roughly half of all EMA and EMI prompts. Given the severity of the sample, and the oftentimes chaotic nature of the high-risk period following psychiatric hospitalization, the fact that the EMA compliance rate was lower than that seen in most EMA research conducted in less psychiatrically severe (or nonclinical) populations (Ottenstein & Werner, 2022) is unsurprising. The observed compliance rate is in line with those from other EMA-only work conducted by both our team and others with suicidal psychiatric inpatients (e.g., Armey et al., 2020; Bentley et al., 2021). Engagement with the EMI was promising, given the well-established problems with mental health engagement (Torous et al., 2018) with >50% of all prompted skills practice exercises completed. Although participants were not compensated for doing the skills practices exercises, since participants were paid for the EMAs, it is possible that participants may have conflated being paid for the EMAs with the EMIs. Future work should make the distinction between payment for study assessments and EMIs clearer given that real-world deployment of the intervention would not include any compensation.

Acceptability

Quantitative findings.

Participants generally found the app/EMI to be acceptable and provided high ratings of helpfulness (in terms of managing emotions) of the in-person sessions and the overall intervention package. Participants’ view of the app used for EMI itself appeared to decline slightly over time. This may be due to the fact that the EMA/EMI content was increasingly perceived as repetitive (as we discuss more below) the more participants used it. Along these lines, it may also be that participants found the EMI more useful in helping them to practice the CBT skills earlier on, but as those skills became more ingrained and potentially accessible to them without the aid of the app over time, they perceived the app as less helpful. Determining the optimal length for a skills-based EMI to be used – with the ultimate goal of promoting skills practice and consolidation in daily life that is not necessarily contingent on an app – is warranted. Of course, this may differ for different people. Finally, it may be that participants did not disentangle the app itself (LifeData) from the web-based content delivered in it. The overall aesthetics and usability of smartphone apps improve every year and thus the underlying technology will likely continue to become more user friendly.

Qualitative findings.

It is encouraging that participants generally found the in-person skills sessions to be helpful, with about half voicing no recommended changes. The most common recommendation about the in-person sessions was to incorporate additional or more varied content/activities, such as working through more examples of how to apply the skills during moments of acute need. This is important to consider in future iterations of this intervention, with a constant challenge being to keep the session content to < 45 minutes. Regarding the EMI, participants most often found that the real-time skills exercises helped them practice their skills, reflect on their emotional experiences, monitor or validate their progress, or remind them that they have skills they can use – all of which are consistent with the underlying conceptual framework of the EMI or the individual CBT skills themselves. Most participants had at least one point of critical feedback on the EMA/EMI prompts – primarily, the assessment questions being redundant or being sent at inopportune hours – and suggested either more variety in the EMA/EMI questions/content or improvements to the app aesthetics. As noted earlier, we built the EMI in Qualtrics and delivered it through LifeData; given the limitations associated with using platforms developed primarily to deliver surveys for an intervention in this study, down the line, a standalone app that is built exclusively to deliver the intervention content would likely improve aesthetics of the EMI.

Limitations

Our findings must be considered in light of a few key limitations that may affect generalizability. First, this was a small pilot study focused on the feasibility and acceptability, thus there was no control condition. Second, the sample was predominantly White and female, limiting generalizability to other racial groups at high risk for suicide. Finally, socioeconomic issues (e.g., insurance coverage leading to early discharge, lack of access to smartphones) may mean that a group at increased risk of suicide due to socioeconomic status (Näher et al., 2020) were less likely to benefit from the intervention. The accessibility of smartphones is increasing constantly, however, due to lower prices and assistance programs like the US Lifeline program.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R34MH113757 (EMK) and K23MH120436 (KHB).

Footnotes

In some cases, participants were in the post-discharge period for more than 28 days, if for example the discharge and/or end of study day fell on a weekend and the study team did not end participation in the app until the next workday.

We used LifeData to deliver Qualtrics surveys because doing so allowed us to have the benefit of the direct customization over randomization of prompts and the aesthetics of the interface allowed in Qualtrics and the delivery methods (e.g., push notifications) available in LifeData.

References

- Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Hankin BL, & Cornette MM (2000). The hopelessness theory of suicidality. In In Joiner TE & Rudd MD (Eds.), Suicide science: Expanding the boundaries (pp. 17–32). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Armey MF, Brick L, Schatten HT, Nugent NR, & Miller IW (2020). Ecologically assessed affect and suicidal ideation following psychiatric inpatient hospitalization. General Hospital Psychiatry, 63, 89–96. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Bullis JR, Gallagher MW, Murray-Latin H, Sauer-Zavala S, Bentley KH, Thompson-Hollands J, Conklin LR, Boswell JF, Ametaj A, Carl JR, Boettcher HT, & Cassiello-Robbins C (2017). The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders Compared With Diagnosis-Specific Protocols for Anxiety Disorders: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(9), 875. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Allen LB, & Ehrenreich-May J (2011). The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treament of Emotional Disorders: Therapist Guide (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Sauer-Zavala S, Murray Latin H, Ellard KK, Bullis JR, Bentley KH, Boettcher HT, & Cassiello-Robbins C (2018). The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Second). Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF (1990). Suicide as escape from self. Psychological Review, 97(1), 90–113. 10.1037/0033-295X.97.1.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT (1975). Hopelessness and Suicidal Behavior: An Overview. JAMA, 234(11), 1146. 10.1001/jama.1975.03260240050026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Coppersmith DL, Kleiman EM, Nook EC, Mair P, Millner AJ, Reid-Russell A, Wang SB, Fortgang RG, Stein MB, Beck S, Huffman JC, & Nock MK (2021). Do Patterns and Types of Negative Affect During Hospitalization Predict Short-Term Post-Discharge Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors? Affective Science, 2(4), 484–494. 10.1007/s42761-021-00058-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Maimone JS, & Nock MK (2021). Addressing self-injurious thoughts and behaviors within the context of transdiagnostic treatment for emotional disorders. In Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Sixth Edition: A Step-by-Step Treatment Manual (6th ed.). Guilford Press, p. 433–479. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Sauer-Zavala S, Stevens KT, & Washburn JJ (2020). Implementing an evidence-based psychological intervention for suicidal thoughts and behaviors on an inpatient unit: Process, challenges, and initial findings. General Hospital Psychiatry, 63, 76–82. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein EE, Bentley KH, Nock MK, Stein MB, Beck S, & Kleiman EM (2022). An ecological momentary intervention study of emotional responses to smartphone-prompted CBT skills practice and the relationship to clinical outcomes. Behavior Therapy, 53(2), 267–280. 10.1016/j.beth.2021.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, & Beck AT (2005). Cognitive Therapy for the Prevention of Suicide Attempts: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA, 294(5), 563. 10.1001/jama.294.5.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büscher R, Torok M, Terhorst Y, & Sander L (2020). Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to Reduce Suicidal Ideation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 3(4), e203933. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung DT, Ryan CJ, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Singh SP, Stanton C, & Large MM (2017). Suicide Rates After Discharge From Psychiatric Facilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(7), 694. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppersmith DDL, Dempsey W, Kleiman EM, Bentley KH, Murphy SA, & Nock MK (2022). Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions for Suicide Prevention: Promise, Challenges, and Future Directions. Psychiatry, 1–17. 10.1080/00332747.2022.2092828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppersmith DDL, Millgram Y, Kleiman EM, Fortgang RG, Millner AJ, Frumkin MR, Bentley KH, & Nock MK (2023). Suicidal thinking as affect regulation. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 132, 385–395. 10.1037/abn0000828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anci KE, Uhl S, Giradi G, & Martin C (2019). Treatments for the Prevention and Management of Suicide: A Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 171(5), 334. 10.7326/M19-0869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisinga R, Grotenhuis M.te, & Pelzer B (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. 10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KR, Huang X, Guzmán EM, Funsch KM, Cha CB, Ribeiro JD, & Franklin JC (2020). Interventions for suicide and self-injury: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials across nearly 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 146(12), 1117–1145. 10.1037/bul0000305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallensleben N, Spangenberg L, Forkmann T, Rath D, Hegerl U, Kersting A, Kallert TW, & Glaesmer H (2017). Investigating the dynamics of suicidal ideation: Preliminary findings from a study using ecological momentary assessments in psychiatric inpatients. Crisis, 39(1), 65–69. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Coppersmith DDL, Millner AJ, Franz PJ, Fox KR, & Nock MK (2018). Are suicidal thoughts reinforcing? A preliminary real-time monitoring study on the potential affect regulation function of suicidal thinking. Journal of Affective Disorders, 232, 122–126. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Turner BJ, Fedor S, Beale EE, Huffman JC, & Nock MK (2017). Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(6), 726–738. 10.1037/abn0000273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhiem O, Bennett CB, Rosen D, & Silk J (2015). Mobile Technology Boosts the Effectiveness of Psychotherapy and Behavioral Interventions: A Meta-Analysis. Behavior Modification, 39(6), 785–804. 10.1177/0145445515595198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maltsberger JT (2004). The descent into suicide. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 85(3), 653–668. 10.1516/3C96-URET-TLWX-6LWU [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näher A-F, Rummel-Kluge C, & Hegerl U (2020). Associations of Suicide Rates With Socioeconomic Status and Social Isolation: Findings From Longitudinal Register and Census Data. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 898. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottenstein C, & Werner L (2022). Compliance in Ambulatory Assessment Studies: Investigating Study and Sample Characteristics as Predictors. Assessment, 29(8), 1765–1776. 10.1177/10731911211032718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakiris N, & Berle D (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Unified Protocol as a transdiagnostic emotion regulation based intervention. Clinical Psychology Review, 72, 101751. 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter M, Goldblatt MJ, Ronningstam E, Herbstman B, & Maltsberger JT (2016). Postdischarge suicide: A psychodynamic understanding of subjective experience and its importance in suicide prevention. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 80(1), 80–96. 10.1521/bumc.2016.80.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, Zelenko O, Tjondronegoro D, & Mani M (2015). Mobile App Rating Scale: A new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 3(1), e27. 10.2196/mhealth.3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Taylor K, & Gooding P (2008). Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions to Reduce Suicide Behavior: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behavior Modification, 32(1), 77–108. 10.1177/0145445507304728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torous J, Nicholas J, Larsen ME, Firth J, & Christensen H (2018). Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone apps: Evidence, theory and improvements. Evidence Based Mental Health, 21(3), 116–119. 10.1136/eb-2018-102891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]