Abstract

Re-oxidation of Cr(III) in treated Cr-contaminated sites poses a considerable source of Cr(VI) pollution, necessitating stable treatment solutions for long-term control. This study explores the immobilization of Cr(VI) into chromite, the most stable and weathering-resistant Cr-bearing mineral, under ambient conditions. Batch experiments demonstrate chromite formation at pH above 7 and Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratios exceeding 1, with Fe(III) occupying all tetrahedral sites, essential for stability. A theoretical model is developed to evaluate the effects of pH and Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratios on chromite crystallinity, resulting in AI4Min-Cr, a publicly accessible platform offering real-time intelligent remediation strategies. To tackle the complexities of non-point source Cr pollution, we employ microbial methods to regulate on-site Eh and pH, optimizing chromite precipitation. Long-term stability tests confirm that chromite remained stable for over 180 days, with potential for magnetic separation recovery. This study presents a mineralogical strategy to address re-oxidation and Cr resource recovery in Cr-contaminated water and soil.

Subject terms: Pollution remediation, Soil microbiology, Water microbiology, Geochemistry

Integration of mineralogy and biology leads authors to develop the Al4Min-Cr platform to stabilize chromium as chromite in contaminated soils and water for point-to-point remediation and long-term Cr pollution control.

Introduction

Chromium (Cr) is abundant in the Earth’s crust, with a mass content of 0.01%, primarily existing in the form of trivalent chromium (Cr(III)) oxides. Chromite, an oxide of Cr(III) and Fe(II) with standard chemical formula FeCr2O4, serves as the principal Cr mineral phase and exclusive raw material for industrial Cr. Mining and industrial activities generate substantial quantities of Cr-containing waste gas, wastewater and residues, leading to the annual release of approximately 75,000 tons of Cr into the environment1. Cr is prone to oxidation into hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) by O22, manganese oxide minerals3, and H2O24, which contaminates surface water, groundwater, and drinking water in most countries worldwide5 due to its high toxicity and mobility6,7, posing a long-term threat to humans and environment.

Over the past five decades, a wide range of physical, chemical, and biological strategies have been applied to Cr pollution8–10. The remediation products mainly include Cr(III) oxides and hydroxides11,12, isomorphous substitutes in amorphous iron compounds13,14, complexes on the surface of iron-containing oxides15, and organometallic complexes16. Unfortunately, these products exhibit metastability and susceptibility to re-oxidation back to Cr(VI)17,18, serving as a major challenge in Cr pollution control19.

Notably, natural chromite demonstrates extraordinary resistance to weathering oxidation, remaining structurally stable even after exposure to oxidizing environments for over 2.5 billion years20. This remarkable stability stems from the strong metal-oxygen covalent bonds in the spinel structure of chromite21. Immobilizing Cr pollutants as stable chromite would effectively solve the bottleneck problem of long-term Cr pollution control. However, current chromite mineralization processes require high temperatures22 and pressures23 under both geological and laboratory conditions, making in-situ and non-point source treatment of Cr pollution impractical. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a low-cost, high-efficiency, and widely adaptable method to precipitate chromite.

This study aims to establish a Cr lifecycle loop from natural chromite resources to artificial chromite through the concept of geoengineering recovery. We successfully achieve chromite mineralization under ambient conditions, and determine the conditions necessary for the complete precipitation of Cr as chromite. Additionally, we develop a dual pathway involving both biologically induced and controlled mineralization to promote chromite formation in Cr-contaminated water and soil. Experimental results spanning over 180 days demonstrate the long-term effectiveness of this method in preventing Cr re-oxidation. This offers a cost-effective solution to the persistent issue of re-oxidation encountered in Cr-pollution control.

Results

Abiotic precipitation of chromite under normal temperature and alkaline conditions

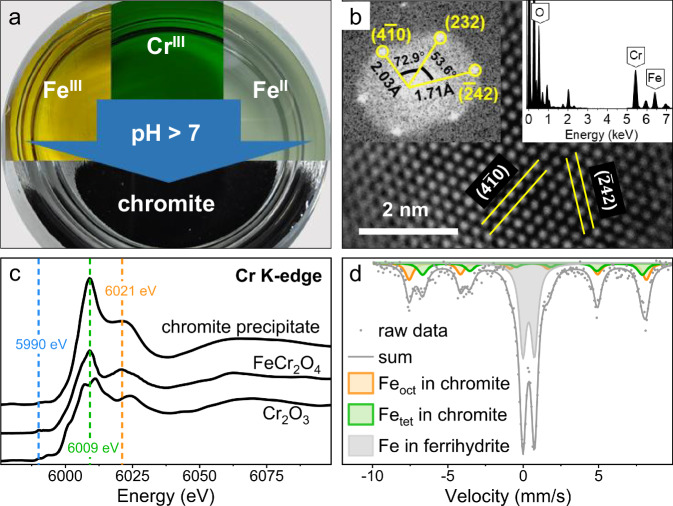

Given that chromite (FeCr2O4) consists of Fe and Cr, it naturally prompts an initial investigation into the coprecipitation of Fe(II), Fe(III), and Cr(III) ions in aqueous solutions. At normal temperature and pressure with pH above 7, Cr(III) can co-precipitate with Fe(III) and Fe(II) to form black solids (Fig. 1a). Analysis of high-resolution morphology and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) indicates that the precipitates consist of Cr and Fe-containing crystals. Statistical analysis on 126 particles reveals that their particle size follows a normal distribution (Supplementary Fig. 1). The mean particle size is concentrated in the range of 20–30 nm, accounting for more than half of the particles. The crystal structure, identified as cubic one based on interplanar spacing and angle, exhibits distinct regular lattice fringes with spacings of 2.03 Å, 1.71 Å, and 2.03 Å, corresponding to the (40), (42), and (232) planes of Cr-spinel, respectively. X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra at Cr K-edge (Fig. 1c) show the characteristic pre-edge peak (5990 eV), the white line (WL) peak (6009 eV) and the post-WL shoulder (6021 eV)24, resembling the characteristics of a standard chromite (FeCr2O4) sample rather than Cr2O3 and thus confirming the presence of Cr(III) in octahedral sites of the spinel structure. Mössbauer spectroscopy under normal temperature reveals specific spectral features of a doublet and two sextets (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 1). The doublet at isomer shift (IS) = 0.34 mm/s and quadrupole splitting (QS) = −0.22 mm/s, and sextet at IS = 0.31 mm/s and QS = −0.01 mm/s are assigned to the tetrahedral coordination of Fe(III) in ferrihydrite and spinel structures, respectively25. The other sextet at IS = 0.61 mm/s and QS = −0.06 mm/s should be allocated to the octahedral structure of Fe(II) & Fe(III) in spinel. All above results indicate both Cr(III) and Fe(II) occupy the octahedral sites (denoted as oct) of spinel, whereas Fe(III) occupies the remaining octahedral sites along with all tetrahedral sites (denoted as tet). Therefore, the successful synthesis of chromite under normal temperature and alkaline conditions has a structural formula of , where the undetermined coefficient x ranges from 0 to 1.

Fig. 1. Abiotic precipitation and characterizations of black precipitates under normal temperature and alkaline conditions.

a Fe(III), Cr(III), and Fe(II) co-precipitate under alkaline conditions to form black precipitates. b TEM-EDS analysis of the precipitates. c Cr K edge XANES spectra of the precipitates, FeCr2O4 and Cr2O3. d Mössbauer spectra analysis of the precipitates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We conducted control experiments to simulate the conditions of Cr-contaminated sites so as to assess the influence of environmental factors on chromite precipitation (Fig. 2). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the precipitates (Fig. 2a, 2b) show that pH and Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio are key factors in determining chromite precipitation and its yield with respect to the impurity goethite (FeOOH). Moreover, according to the fact that the narrower diffraction peaks in XRD patterns result from the higher crystallinity, it clearly demonstrates that these two factors also play critical roles in influencing the crystallinity of the precipitates. Chromite formation is favored at a pH greater than 7 and in the case with a Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio exceeding 1. Within the pH range from 7 to 10.7, increasing pH leads to higher chromite crystallinity. However, there is a sharp decrease in chromite crystallinity once the pH surpasses 10.7 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2). With respect to the Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio, an elevated Fe(III) concentration results in increased crystallinity of chromite, exhibiting a rapid escalation rate before reaching a Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio of 3. Notably, chromite formation is impeded when the Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio falls below 1 (Fig. 2b), and the initial concentration of Cr(III) does not affect chromite formation under constant Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratios and pH conditions (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Factors influencing the precipitation of chromite and the crystallinity of precipitates.

a XRD patterns of precipitates at different pH levels. b XRD patterns of coprecipitates of Fe(III), Cr(III) and Fe(II) at varying Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratios. c XRD patterns of products obtained through different precipitation mixing sequences. d XRD patterns of the precipitates. “(FeIII:CrIII = 1.3)s → FeIII:CrIII = 3” refers to transferring precipitates with a Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio of 1.3 to 3. “(FeIII:CrIII = 3)s → FeIII:CrIII = 0.3” refers to transferring precipitates with a Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio of 3 to 0.3. The pH of these reaction systems is maintained at 10.7. The ratio of FeIII to CrIII in (b) and (d) refers to the initial ratio of added substances, which closely approximates the ratio in chromite due to the negligible presence of goethite as an impurity. In all experiments, the concentration of Fe(II) was added as half of that of total trivalent metal ions to keep an overall valence of zero. Unless otherwise specified, the molar ratio of Fe(III):Cr(III):Fe(II) is set at 1.5:0.5:1, and the pH for all precipitation events is maintained at 9. The right and left shading in each panel indicate the position of (311) and (220) diffraction peaks, respectively, shown as gradients that fade to reflect decreasing crystallinity. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the process of remediating Cr-contaminated sites, multiple mixing sequences exist among Cr(III), Fe(III), and Fe(II). Figure 2c illustrates that different mixing sequences of these substances can lead to the successful formation of chromite. Results show that co-precipitates containing Fe(III), Cr(III), and Fe(II), or sequential addition of different precipitates, can result in the formation of well-crystallized chromite with or without other minerals like goethite present. Notably, prior to the addition of Cr(III), Fe(II) and Fe(III) can coprecipitate to produce magnetite, which is then converted into chromite with enhanced crystallinity following the introduction of Cr(III) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, compared with those systems adding Fe(III) first, the system with the final addition of Fe(III) yields poorly crystallized chromite. This sharp contrast suggests the remarkable and positive role of Fe(III) in chromite formation.

Furthermore, due to geological26 or human activities27, previously formed chromite may migrate from Cr-contaminated sites to environments. We found that chromite formed with low crystallinity (Fe(III)/Cr(III) = 1.3) increases its crystallinity when introduced into environments conducive to mineralization (Fe(III)/Cr(III) = 3) (Fig. 2d). By contrast, it retains its well-crystallized structure (Fe(III)/Cr(III) = 1.3) in those environments that are less favorable for further mineralization (Fe(III)/Cr(III) = 0.3). Therefore, even if formed chromite migrates to those environments with different Fe(III) and Cr(III) concentrations, it can always maintain the high structural stability.

Thermodynamic mechanism of chromite formation

Visual MINTEQ software simulations and Density Functional Theory (DFT) computations were utilized to calculate the Gibbs free energy of reactions involving Fe(III), Cr(III), and Fe(II), and to investigate the thermodynamic mechanisms governing chromite formation under ambient conditions. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, the Gibbs free energy of reactions involving Fe(III), Cr(III), and Fe(II) ions in various chemical states varies depending on their respective occurrence phases. When the Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio remains constant, a decrease in acidity (i.e., the increase of pH) leads to an increase in total ion activity (Supplementary Fig. 5), resulting in a reduction in reaction free energy (Fig. 3a). As the pH approaches 7, the Gibbs free energy becomes negative, enabling chromite to precipitate spontaneously. Further increasing the pH to ~10 causes a corresponding increase in the total ion activity and a decrease in Gibbs free energy, thus improving the product’s crystallinity. However, when the pH exceeds 10.7, the total ion activity of Fe(II) and Cr(III) decreases, based on the simulations from Visual MINTEQ software (Supplementary Fig. 5). All of the calculation results regarding the effect of pH and Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio on the Gibbs free energy accord well with the crystallinity of the experimental products, especially identifying the same optimal pH for chromite precipitation (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, the standard Gibbs free energy is utilized to investigate the reaction pathways of all their derived species with pH. Our findings indicate that species such as Fe2+, Fe(OH)2+ and Cr(OH)3(aq), which are predominantly present in alkaline solutions (Supplementary Fig. 5), play a crucial role in reducing the standard Gibbs free energy of the reaction (Fig. 3b). The decrease or disappearance of these species at other pH levels, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, would cause a rapid increase in the Gibbs free energy and a corresponding decline in product crystallinity. Although the resulting optimal pH for chromite precipitation (~10.7) differs slightly from that calculated from the standard Gibbs free energy (~9.0), their consistent trends observed in both methodologies validate the roles of alkalinity in controlling ion species and chromite formation.

Fig. 3. Mechanism of chromite precipitation under ambient temperature and pressure.

a Effects of Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratios and pH on the negative Gibbs free energy of reactions (3D plot, obtained through DFT computations) and the crystallinity of experimental products (2D plot). The 2D plot indicates crystallinity through the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the (311) plane in XRD patterns, with the color spectrum transitioning from blue to white to red, denoting increased crystallinity. A negative correlation is evident between Gibbs free energy and product crystallinity. b Variation in standard Gibbs free energy of the reactions involving Fe(III), Fe(II), and Cr(III) forming chromite across different pH levels. c Gibbs free energy value and the schematic diagram of the reaction between Cr-O tetrahedra ([CrIIIO4]) and Fe-O octahedra ([FeIIIO6]) in the framework of a spinel structure. d Conceptual diagram of the AI4Min-Cr platform, which provides real-time intelligent strategies for effectively managing Cr-contaminated sites. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The octahedral site preference energy (OSPE) elucidates why chromite fails to form when the Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio is below 1. The higher OSPE of Cr(III) (37.7 kcal/mol) compared to that of Fe(II) (4 kcal/mol) and Fe(III) (0 kcal/mol) in the spinel structure28 results in Cr(III) ions would like to occupy octahedral sites exclusively. This is supported by Gibbs free energy calculations, demonstrating that a strong spontaneous reaction (∆G = -122.6 kJ/mol) forming CrIIIO6 octahedron and FeIIIO4 tetrahedron rather than the opposite direction (Fig. 3c). Cr(III) preferentially occupies octahedral sites and can replace Fe(III), facilitating the spontaneous conversion of magnetite into chromite, as observed in our experiments (Supplementary Fig. 4). Consequently, when the Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio is less than 1 (e.g., Fe(III):Cr(III) = 0.5:1.5), Fe(II) at octahedral sites is less competitive than Cr(III) and it would be pushed towards tetrahedral sites. This results in the crystal chemical formula of the precipitates being (FeIII0.5FeII0.5)tet[FeII0.5CrIII1.5]octO4 due to Fe(II) ions were added as half of trivalent metal ions. Although the OSPE of Fe(II) is positive, some Fe(II) remaining in the tetrahedral sites will lead to the elevated system energy and thus destabilize the precipitates. However, with an increasing Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio above 1, all Fe(II) can occupy octahedral sites. At this time, the Gibbs free energy of the reaction turns negative (Fig. 3a), suggesting that chromite can keep stable. As for the role of Fe(III), both concluded from experiments and calculations (Fig. 2c and Fig. 3), it has a relatively strong preference of occupying tetrahedral sites due to its lowest OSPE, and it could be quite critical for chromite formation under ambient conditions, in contrast to Fe(III)-free chromite (FeIICrIII2O4 with Fe(II) in tetrahedral sites), which is typically produced under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions. Notably, DFT computations confirm the absence of Cr(III) in the goethite lattice due to a positive Gibbs free energy associated with its incorporation (Eq. 1). In this case, one Fe atom is replaced with a Cr atom in a fabricated supercell of goethite ([FeOOH]24). Even if Cr(III) is present in goethite, it will spontaneously migrate into the octahedral sites in the spinel structure due to a negative Gibbs free energy (Eq. (2)).

So, pH and Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio influence the Gibbs free energy of mineralization reactions by modulating the ion activity and species of Fe(III), Cr(III), and Fe(II), ultimately determining the potential for chromite precipitation and the crystallinity of precipitates. Chromite can form when Fe(III)/Cr(III) ratio exceeds 1 and pH is above 7. Cr(III) predominantly occupies chromite’s octahedral sites due to thermodynamic preference, even in the presence of other phases such as goethite, resulting in minimal presence of Cr(III) in their structures.

| 1 |

| 2 |

Based on the Gibbs free energy dataset for chromite precipitation reactions under normal temperature and pressure conditions, an open-access online platform named AI4Min-Cr (http://cr.ai4mineral.com/) has been established. This platform offers real-time intelligent solutions for effectively managing Cr-contaminated sites (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 6). Users can input key parameters related to Cr-contaminated sites, including pH values, Fe concentrations (with options for Fe(III), Fe(II), or total Fe), and Cr concentrations (offering choices for Cr(III), Cr(VI), or total Cr). Additionally, users can specify the desired pH range to ensure that the remediated site meets the land use criteria. By selecting abiotic or biotic remediation alternatives, this platform generates remediation strategies such as adding Fe(III) into the site, employing Fe(III)-reducing bacteria, or adjusting soil pH. Given the complexities of Cr-contaminated sites, it is recommended to conduct continuous monitoring of pH, Fe and Cr concentrations after the remediation, and adjust the treatment strategies promptly.

Chromite precipitation achieved by low-cost biological strategy

The introduction of additional Fe(III) and Fe(II) into Cr-contaminated sites (mainly consisting of Cr(VI) and minor Cr(III)) presents several drawbacks such as operational complexity, high costs, resource wastage, and potential secondary pollution10. Remediation of existing Cr-contaminated sites using Fe-based reducing stabilizers, primarily FeSO4, often leads to excessive Fe(III) content in the soil29. To effectively utilize Fe(III) in Cr-contaminated sites for in-situ remediation and achieve cost-effective Cr fixation as chromite, the biomineralization process utilizing Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 (S. MR-1) was attempted, which is capable of reducing Cr(VI) and Fe(III) to Cr(III) and Fe(II), respectively.

S. MR-1, a strain capable of thriving in environments with Cr(VI) concentrations up to 500 mg/L and a pH value of 11, was obtained following long-term domestication (Supplementary Fig. 7). A comparative analysis (Fig. 4a, 4b) demonstrates that treating neutral wastewater containing 100 mg/L Cr(VI) for 7 days using Fe(III), S. MR-1, or their combination (with Fe(III) at a concentration of 700 mg/L) yields distinct outcomes. Fe(III) forms hydroxide precipitates and adsorbs only about 6% of Cr(VI), resulting in minimal changes in the solution. In contrast, S. MR-1 reduces all Cr(VI) within 7 days; however, approximately 90% of the reduced Cr(III) remains in the solution, imparting a light green color. The synergistic action of S. MR-1 with Fe(III) accelerates Cr(VI) reduction, achieving complete reduction within 3 days (Supplementary Fig. 8). This combined approach removes all Cr from the solution within 7 days and forms black precipitates identified as chromite (Supplementary Fig. 9). The addition of S. MR-1 also results in the alkalization of the solution due to OH- generation during organic matter decomposition.

Fig. 4. Microbial synergy with Fe(III) for enhanced Cr(VI) reduction and Cr(III) fixation in Cr-containing wastewater.

a Comparison of conditions pre- and post-5-day reaction under various treatments (centrifuged at 4390 × g for 5 min). b Temporal evolution of total Cr concentration under different scenarios: “S. MR-1+FeIII” indicates the addition of both bacteria and Fe(III) to the Cr(VI)-contaminated solution, “S. MR-1” represents the introduction of bacteria alone, and “Fe(III)” illustrates the addition of Fe(III) alone. All experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3), and data are presented as mean values +/− standard deviation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. c Chromite can either aggregate into small suspended particles, be adsorbed by EPS to form dendritic structures, or be adsorbed onto microbial surfaces. d Intracellular chromite particles are observed in the periplasmic space on the fifth day, migrate to the inner membrane by the tenth day, and are expelled from the cells by the fifteenth day. e Flowchart of microbial chromite synthesis, divided into three stages: 1) Complete reduction of Cr(VI) by bacteria, 2) Partial reduction of Fe(III) by bacteria, and 3) Microbial synthesis of chromite. More than 10 independent images were captured by TEM in each experiment and all they have similar results, and the displayed images in c and d are without any selection bias.

To gain insight into the mechanism of chromite synthesis by the “S. MR-1 + Fe(III)” group, scanning electron microscope (SEM) and TEM observations were conducted. The distribution of chromite outside the cell is depicted in Fig. 4c. Cr(III) and Fe(II) in solution co-precipitate with Fe(III) to form chromite. This chromite can either aggregate into fine suspended particles, be adsorbed by extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) to form dendritic structures, or be adsorbed onto microbial surfaces. These mineralization processes belong to bio-induced mineralization (BIM)30, and the underlying mechanism is summarized by Eqs. (3)–(6).

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

Remaining chromite is observed inside the bacteria. During the initial stage of the reaction, S. MR-1 captures Cr(III), Fe(III), and Fe(II), synthesizing chromite within the periplasmic space and on the cell membrane. As the reaction progresses, chromite begins to appear on the surface of various cellular structures. In the final stage of the reaction, chromite becomes concentrated and is released from the cell into the surrounding environment. Figure 4d shows the comprehensive process of intracellular synthesis of chromite by S. MR-1 and its subsequent release into the environment. These mineralization processes are categorized as bio-controlled mineralization (BCM)31, with the underlying mechanism summarized by Eq. (7).

| 7 |

Essentially, S. MR-1 decomposes organic matter to produce OH-, creating an alkaline environment and transferring electrons to Cr(VI) and Fe(III), thereby generating Cr(III) and Fe(II). The EPS and bacterial cells serve as nucleation sites for mineral formation, inducing and controlling chromite production (Fig. 4e).

Long-term treatment of Cr residue to form stable and recyclable chromite

We applied our proposed remediation method to the Cr-contaminated site (including Cr-contaminated soil, surface water and groundwater) at the Haibei Chemical Plant in Qinghai Province, China, which has previously been treated with FeSO4 but has suffered from re-oxidation issues32. The initial concentrations of Cr(III), Cr(VI) and Fe(III) in the contaminated soil were detected at approximately 80, 160 and 5200 mg/kg, respectively, with Fe(II) absent, and the pH was around 8.5 (Supplementary Table 2). By utilizing AI4Min-Cr platform, we received swift recommendations for both biotic and abiotic remediation strategies. The biotic strategy suggested that no additional Fe(III) is needed, but it does require the addition of metal-reducing bacteria like S. MR-1 and an adjustment of pH to ~10.7. The abiotic strategy recommended adding 720 mg/kg Fe(II) to completely precipitate all Cr(VI) and Fe(III), along with a pH adjustment to ~10.7. In this case, obviously, the biotic strategy is preferable due to cost-effectiveness and low risk of secondary pollution from excess Fe. After two months of Cr tolerance domestication, S. MR-1 was added to the Cr-contaminated soil for remediation, resulting in a distinct layer of magnetically black precipitates between the pink bacterial solution and the brown soil (Fig. 5a). TEM observation reveals the presence of chromite crystals both in the soil and inside the bacteria (Fig. 5b). Additionally, Cr-XPS analysis demonstrates that almost all Cr(VI) in the soil is reduced to Cr(III) after treatment with S. MR-1 (Fig. 5c). Furthermore, after 180 days of air exposure, no detectable Cr(VI) is observed in solid products, with the valence proportions of Cr(VI) being no more than 1 wt% based on the detection limit of XPS. There is also no detectable Cr(VI) (<0.004 mg/L, based on detection limit of the spectrophotometric method) released into the solution (Supplementary Fig. 10a), proving the long-term stability of chromite.

Fig. 5. Stability and magnetism of chromite.

a Stratification of bacteria-mineral-soil following S. MR-1 treatment of Cr-contaminated sites. b Microbial remediation of Cr-contaminated sites leading to chromite formation. More than 10 independent images were captured by TEM in each experiment and they all have similar results, and the displayed images in b are without any selection bias. c Cr XPS analysis of soil samples before remediation, immediately after remediation, and following 180 days of air exposure post-remediation. The binding energies corresponding to CrVI 2p1/2 and CrVI 2p3/2 are typically located at 589.1 and 579.8 eV, respectively. The binding energies corresponding to CrIII 2p1/2 and CrIII 2p3/2 are typically located at 587.1 and 577.3 eV, respectively. d Time-dependent variation in Cr(III) concentration dissolved from chromite in solution of pH 7, synthesized by various abiotic methods. The gray dashed line represents the maximum total Cr concentration allowed by national standards for industrial wastewater discharge. e Magnetism of precipitates under different conditions. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Considering that complicating real environment of contaminated soil and water with diverse pH and Fe/Cr conditions, the stability and magnetism of precipitated product chromite should be systematically monitored. Ion concentration variation charts show that when synthesized under different Fe/Cr and neutral to alkaline pH conditions, only a small amount of Cr(III) is initially released into the solution due to dissolution, followed by a decline through recrystallization within 180 days post-synthesis. During the whole process, Cr remains in the solid phase as Cr(III) rather than Cr(VI), as verified by XPS (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Additionally, no Cr(VI) is detected and the maximum concentration of total Cr remains below the standard limit of 1.0 mg/L, reaching a peak of only 0.88 mg/L (Fig. 5d). Moreover, in more acidic environments like pH 2, chromite exhibits resistance to acid corrosion (Supplementary Fig. 11). Our findings accord well with previous experimental observations of natural chromite weathering33–35, suggesting that chromite can maintain long-term structural stability across a wide range of environmental conditions, even at the nanoscale (10–80 nm). Furthermore, the aging of these nanoparticles could lead to aggregation over time, effectively reducing their surface area and reactivity, which further mitigates the risk of Cr release. Results of vibration sample magnetization (VSM) confirm the magnetism of chromite products, with a saturation magnetization ranging from 8 to 34 emu/g (compared to approximately 40 emu/g for magnetite36). Additionally, there exists a positive correlation between the magnetization intensity and the crystallinity of chromite (Fig. 5e). It is evident that the on-site precipitated chromite can maintain stable for extended periods and can be efficiently recovered through magnetic separation at low cost (Fig. 5a).

Discussion

Our findings effectively address the challenge of Cr re-oxidation in Cr-contaminated water and soil by immobilizing Cr into chromite with long-term stability, thus providing a robust solution for Cr pollution control. The strategy of sequestering Cr within the chromite lattice has proven highly effective in maintaining enduring and consistent Cr pollution mitigation. Our study on the abiotic formation of chromite highlights the broad range of conditions conducive to chromite mineralization under normal temperature and pressure. By calculating the Gibbs free energy and building the dataset, we have developed a theoretical model for chromite precipitation and transformed it into a publicly accessible platform named AI4Min-Cr, which provides real-time, intelligent strategies for Cr pollution remediation.

Chromite exhibits enduring stability in both composition and structure, ensuring the resolution of the re-oxidation issue. Furthermore, the magnetic properties inherent in chromite present opportunities for the recovery of Cr resources through magnetic separation. The microbial synergistic synthesis of chromite through on-site Fe(III) in Cr-contaminated sites remarkably reduces treatment expenses, facilitating the long-term stabilization and recovery of Cr pollution, especially in developing countries from an economic perspective. In addition, there may be a natural risk of Cr pollution resulting from mining activities of chromite ore and weathering of Cr-rich silicates33–35, along with soil acidification. Our proposed strategy emphasizes the importance of neutralization and moderate alkalization through biotic or abiotic means. AI4Min-Cr can assist in identifying the optimal list of ingredients to facilitate the conversion of Cr pollution back to chromite.

Particularly, our study enhances the comprehension of chromite mineralization processes, providing substantial scientific perspectives on the geochemical dynamics of Cr and Fe. Furthermore, drawing from a nature-inspired mineralogical approach, we present a paradigm with far-reaching implications for the sustainable remediation of various heavy metal pollutants.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

The chemicals used in this study included ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3•6H2O), ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2•4H2O), chromium chloride hexahydrate (CrCl3•6H2O), potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7), LB liquid medium, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium lactate (C3H5O3Na), diphenylcarbazide (C13H14N4O), and ferrozine (C20H13N4NaO6S2), all purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. S. MR-1 (ATCC700550) was provided by Beijing Key Laboratory of Mineral Environmental Function. Cr-contaminated soil was obtained from Haibei Chemical Plant in Qinghai Province. All reagents were used without any purification. Deionized water (Millipore) was used in all experiments.

Theoretical simulation and calculation

Visual MINTEQ software (version 3.1) was employed to simulate the ionic species and quantities of Fe(III), Cr(III), and Fe(II) in aqueous solutions at room temperature and pressure. All density functional theory (DFT) calculations in this study were conducted using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP 6.4.1)37. Bulk optimizations were performed with the generalized gradient approximation plus Hubbard U (GGA + U) method38. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional and the projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials were utilized39. To avoid decimals or fractions in the chemical formula, large stoichiometric numbers are necessary. In this case, the unit cell of magnetite ([Fe3O4]8) and the 3 × 2 × 1 supercell of goethite ([FeOOH]24) were fully relaxed using 4 × 4 × 4 and 4 × 4 × 3 Monkhorst-Pack k-point sampling grids, respectively. The cutoff energy was set to 520 eV. Given the presence of transition metal elements (Fe, Cr), spin-polarized calculations were performed. The force convergence criterion was set to 0.01 eV/Å for lattice parameter relaxation, and the energy convergence criterion was set to 1 × 10−6 eV for atomic position relaxation. U parameters of 5.3 eV for Fe and 3.5 eV for Cr were adopted in this work40.

To correct the formation energy obtained from DFT (GGA/GGA + U)41, we applied the Wang scheme, which has proven effective in converting DFT-calculated formation energies to experimental formation enthalpies at room temperature. For the calculation of Gibbs free energy of formation, it has been demonstrated that the vibration of solids at room temperature contributes minimally to the Gibbs free energy and can be offset by the difference between the solids of the products and reactants (particularly with similar structures). Consequently, the corrected formation enthalpy is approximately equivalent to the Gibbs free energy of formation. Additionally, frequency calculations were conducted to evaluate the vibrational contribution to the formation energy, revealing that the difference is within 0.1 eV (data not shown), thus exerting minimal impact on our analysis. The data for the Gibbs free energy of formation of all ionic and aqueous substances were obtained from the CRC Handbook42.

Abiotic synthesis of chromite experiments

Solutions of Fe(II), Fe(III), and Cr(III) or their corresponding hydroxide precipitates were mixed within an anaerobic glove box (100% argon) and magnetically stirred at 600 rounds per minute for 12 h to form precipitates. The concentration of divalent metal ions (Fe(II)) was added as half of that of total trivalent metal ions, so that the product met the requirement of having an overall valence of zero. These precipitates were subsequently centrifuged, washed multiple times to remove soluble salts, and dried using a freeze-drying apparatus to yield the final product for mineralogical characterization. To check the long-term stability of chromite, the pH of formed suspensions in batch systems with different Fe/Cr and pH were directly adjusted to acidic (pH 2), neutral (pH 7), and alkaline (pH 8&10) by adding HCl solution (1 mol/L). Released Cr(III) and Cr(VI) ions were monitored in air exposure over 180 days.

Bacterial domestication process for tolerating high alkalinity and high-concentration Cr(VI)

Firstly, S. MR-1 was inoculated during the logarithmic growth phase into LB medium containing 10 mg/L Cr(VI) at an inoculation rate of 20%. After approximately 12 h, when the logarithmic growth phase was reached, this step was repeated at least three times to ensure normal growth and reproduction of the bacteria. Then, the inoculation rate was reduced to 10%, and the steps were repeated until normal bacterial growth and reproduction were observed. Next, gradually decreasing the inoculation rate until the bacteria could grow and reproduce normally in LB medium with the same Cr(VI) concentration at an inoculation rate of 5%. Subsequently, gradually increasing the Cr(VI) concentration, initially by 10 or 20 mg/L each time and later by 50 mg/L each time, until the bacteria could grow and reproduce normally in LB medium containing up to 500 mg/L Cr(VI). A similar approach was taken to incrementally increase the initial pH of the LB medium containing 500 mg/L Cr(VI) by 0.5 units each time until normal growth was observed at a pH of 11.

The initial domestication process required approximately two months. For preservation, domesticated bacteria were inoculated into normal LB medium and grown to the logarithmic phase. Then, 1 mL of sterile glycerol was mixed thoroughly with the bacterial suspension to achieve a glycerol concentration of approximately 30%, and the mixture was stored at −80 °C for preservation. Each time the bacteria are to be used, they must be activated and then re-domesticated, with the domestication cycle shortened to one week for this subsequent phase.

This kind of bacteria after domestication can tolerate high alkalinity and high-concentration Cr(VI) (Supplementary Fig. 7), whose growth curve in 500 ppm Cr(VI) is quite similar to the wild strain. By contrast, the wild strain S. MR-1 before domestication had a low-performance cell growth in 500 ppm Cr(VI), which proves the success of our domestication process.

Microbial remediation experiments

Prepare three 100 mL portions of neutral Cr-containing wastewater in serum bottles, each with a Cr(VI) concentration of 100 mg/L and C3H5O3Na as the electron donor at a concentration of 80 mM. Add Fe(III) at a concentration of 700 mg/L to two of the bottles. Cultivate domesticated S. MR-1 in 500 mL of LB medium until the logarithmic growth phase is reached. Centrifuge the bacterial culture at 1580 × g for 10 min, discard the supernatant, and prepare a stationary cell suspension. Centrifuge again at 1580 × g for 10 min, discard the liquid, and resuspend the bacterial cells in one serum bottle containing Fe(III) and one serum bottle without Fe(III). Seal the serum bottles with stoppers and place them on a shaker for the reaction.

A 50 mL centrifuge tube was placed at the Cr-contaminated site for an in-situ remediation experiment, with 30 g of Cr-contaminated soil added to the tube. The domesticated S. MR-1 was cultured in 500 mL of LB medium until it reached the logarithmic growth phase. The bacterial culture was then centrifuged at 1580 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded to prepare a 30 mL stationary cell suspension. This suspension was added to the centrifuge tube, which was subsequently sealed with a lid and allowed to react for 14 days.

After the reaction was complete, open the serum bottle cap and expose the whole system to air for 180 days. During this period, take regular samples to measure the dissolution of Cr(III) and the amount of Cr(VI) oxidized. Freeze-dry the solid product and analyze the valence state and content of Cr.

Quantification of ion concentration

Regularly extract 1 mL of the reaction solution and centrifuge it in a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube at 6890 × g for 5 min. Collect the supernatant for analysis. The concentration of Fe(II) in the solution is determined using phenanthroline spectrophotometry, while the concentration of Cr(VI) is measured using the diphenylcarbazide spectrophotometric method, which has a detection limit of 0.004 mg/L. Total Fe and total Cr concentrations in the solution are quantified using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Agilent 720ES).

Mineralogical characterization

The phase and crystallinity of the product were determined using X-ray diffraction (XRD, SAXsess). The crystallinity of chromite was qualitatively determined through the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the (311) plane in XRD patterns, analyzed by Highscore Plus software (version 3.0.5). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (TEM-EDS, Tecnai F20) was employed to confirm the elemental composition, crystal structure, morphology, and particle size of chromite43. TEM images were analyzed by Digital Micrograph (version 3.5), and particle size of solids was measured and conducted statistical analysis by Nano Measurer (version 3.5). X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS, 1W1B endstation of Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Institute of High Energy Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) was utilized to obtain valence state and coordination information of Cr in chromite. The obtained spectra were analyzed by Athena (Demeter software package, version 0.9.26). The coordination states of Fe(II) and Fe(III) in chromite were determined using Mössbauer spectroscopy (MFD-500AV-04), whose data were fitted by Mosswinn (version 4.0). The valence state of solid Cr was assessed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, 250XI). All the data were processed by XPSPEAK software (version 4.1). The C 1 s peak at 284.8 eV was used as an internal reference for absolute binding energy. Cr 2p peak fitting was performed with a linear background and two unconstrained Gaussian/Lorentzian (70/30) peaks, with FWHM values fixed at ~2.2 eV for CrIII 2p1/2 and ~2.4 eV for CrIII 2p3/2. The magnetic properties of the product were measured using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, VSM3900).

Microbiological characterization

The growth status of bacteria was confirmed by measuring the absorbance of the bacterial solution at a wavelength of 600 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to examine the surface morphology of microorganisms and the distribution of biologically induced mineralization products. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was employed to observe changes in microbial intracellular morphology over the reaction time and the distribution of bio-controlled mineralization products.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42192502 & 92351302 to Y.L., 42302037 to Y.Z.L., 42372049 to Y.L.) and the Deep-time Digital Earth (DDE) Big Science Program. We sincerely appreciate Professor Danian Ye for his pioneering research on the mechanism of chromium enrichment in cast stone experiments, which has greatly inspired our investigation into chromite formation under ambient conditions. We also extend our gratitude to scientists at 1W1B beamline of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility and HAXA beamline of the Canadian Light Source for their great help in data collection.

Author contributions

Y.L., A.L. conceived the study. Y.L., T.H., Y.Z.L., Y.H., X.B. provided methodology and performed modeling. T.H., Y.Z.L., R.Y., Y.Z., B.H., H.L., X.J. processed the data and interpreted the results. T.H., Y.L., Y.Z.L. wrote the paper. Y.L., X.B., A.L. contributed to paper polishing.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Huanwei Wang and the Michael Schindler for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All data in this study are provided in Source Data file. They are also publicly available at https://github.com/rocky-xuan/Back-to-chromite and https://zenodo.org/records/14744274. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source code for locally executing AI4Min-Cr is publicly available at https://github.com/rocky-xuan/Back-to-chromite and https://zenodo.org/records/14744274.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Tianci Hua, Yanzhang Li, Yuxuan Hu.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-57300-z.

References

- 1.Nriagu, J. O. & Evert, N. Chromium in the natural and human environments (John Wiley & Sons Press, 1988).

- 2.Schroeder, D. C. & Lee, G. F. Potential transformations of chromium in natural waters. Water Air Soil Pollut.4, 355–365 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett, R. & James, B. Behavior of chromium in soils: III. Oxidation. J. Environ. Qual.8, 31–35 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rock, M. L. et al. Hydrogen peroxide effects on chromium oxidation state and solubility in four diverse, chromium-enriched soils. Environ. Sci. Technol.35, 4054–4059 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jobby, R. et al. Biosorption and Biotransformation of Hexavalent Chromium [Cr(VI)]: A Comprehensive Review. Chemosphere207, 255–266 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotaś, J. & Stasicka, Z. Chromium occurrence in the environment and methods of its speciation. Environ. Pollut.107, 263–283 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saha, R. et al. Sources and toxicity of hexavalent chromium. J. Coord. Chem.64, 1782–1806 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang, D. et al. Reduction mechanism of hexavalent chromium in aqueous solution by sulfidated granular activated carbon. J. Clean. Prod.316, 128273 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pushkar, B. et al. Chromium pollution and its bioremediation mechanisms in bacteria: a review. J. Environ. Manag.287, 112279 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bao, Z. et al. Method and mechanism of chromium removal from soil: a systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.29, 35501–35517 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kierczak, J. et al. Effect of mineralogy and pedoclimatic variations on Ni and Cr distribution in serpentine soils under temperate climate. Geoderma142, 165–177 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, Y. et al. Remediation of hexavalent chromium contamination in chromite ore processing residue by sodium dithionite and sodium phosphate addition and its mechanism. J. Environ. Manag.192, 100–106 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerth, J. Unit-cell dimensions of pure and trace metal-associated goethites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac.54, 363–371 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwertmann, U. et al. Chromium-for-iron substitution in synthetic goethites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac.53, 1293–1297 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlet, L. & Manceau, A. X-ray absorption spectroscopic study of the sorption of Cr(III) at the oxide water interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci.148, 443–458 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaupenjohann, M. & Wilcke, W. Heavy metal release from a serpentine soil using a pH-stat technique. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J.59, 1027–1031 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apte, A. et al. Oxidation of Cr(III) in tannery sludge to Cr(VI): Field observations and theoretical assessment. J. Hazard. Mater.121, 215–222 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dermatas, D. et al. Ettringite-induced heave in chromite ore processing residue (COPR) upon ferrous sulfate treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol.40, 5786–5792 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang, J. L. et al. A review of the formation of Cr(VI) via Cr(III) oxidation in soils and groundwater. Sci. Total Environ.774, 145762 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusky, T. M. et al. The Archean Dongwanzi ophiolite complex, North China craton: 2.505-billion-year-old oceanic crust and mantle. Science292, 1142–1145 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun, J. et al. Unraveling the synergistic effect of heteroatomic substitution and vacancy engineering in CoFe2O4 for superior electrocatalysis performance. Nano. Lett.22, 3503–3511 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younis, M. et al. Magnetic phase transition and magneto-dielectric analysis of spinel chromites: MCr2O4 (M = Fe, Co and Ni). Ceram. Int.44, 10229–10235 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coulthard, D. A. et al. Petrogenetic implications of chromite-seeded boninite crystallization experiments: providing a basis for chromite-melt diffusion chronometry in an oxybarometric context. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta297, 179–202 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen, N. et al. XAS characterization of nano-chromite particles precipitated on magnetite-biochar composites. Radiat. Phys. Chem.175, 108544 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dyar, M. D. et al. Mössbauer spectroscopy of earth and planetary materials. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci.34, 83–125 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo, B. et al. Mineralogy and geochemistry of the peridotites and high-Cr podiform chromitites from the Tangbale Ophiolite Complex, West Junggar (NW China): Implications for the origin and tectonic environment of formation. Ore Geol. Rev.122, 103532 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das, P. K. et al. Chromite mining pollution, environmental impact, toxicity and phytoremediation: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett.19, 1369–1381 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurepin, V. A. Thermodynamics of cation distribution in simple spinels. Geokhimiya5, 688–697 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han, W. et al. Status and prospect of in-situ remediation technologies applied in hexavalent chromium contaminated sites. J. Environ. Eng. Technol.13, 1486–1496 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang, F. et al. Microbial induced phosphate precipitation accelerate lead mineralization to alleviate nucleotide metabolism inhibition and alter Penicillium oxalicum’s adaptive cellular machinery. J. Hazard. Mater.439, 129675 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong, H. L. et al. A critical review of mineral-microbe interaction and co-evolution: mechanisms and applications. Natl Sci. Rev.9, 128 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, S. Q. et al. Cr(VI)-pollution Mechanism and Control Method of Groundwater in Haibei Chemical Plant of Haiyan County, Qinghai Province. Geoscience23, 94–102 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schindler, M. et al. Previously unknown mineral-nanomineral relationships with important environmental consequences: the case of chromium release from dissolving silicate minerals. Am. Miner.102, 2142–2145 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schindler, M. et al. Dissolution mechanisms of Chromite: Understanding the release and fate of chromium in the environment. Am. Miner.103, 271–283 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClenaghan, N. W. & Schindler, M. Release of chromite nanoparticles and their alteration in the presence of Mn-oxides. Am. Miner.107, 642–653 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rezazadeh, L. et al. Application of oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) as a controlling parameter during the synthesis of Fe3O4@PVA nanocomposites from industrial waste (raffinate). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.27, 32088–32099 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B.54, 11169 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anisimov, V. I. et al. First-principles calculations of the electronic structure and spectra of strongly correlated systems: the LDA+ U method. J. Phys. Condens. Mat.9, 767 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B.59, 1758 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, L. et al. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA+ U framework. Phys. Rev. B.73, 195107 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, A. et al. A framework for quantifying uncertainty in DFT energy corrections. Sci. Rep.11, 15496 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haynes, W. M. CRC handbook of chemistry and physics (CRC Press, 2016).

- 43.Kyono, A. et al. The influence of the Jahn-Teller effect at Fe2+ on the structure of chromite at high pressure. Phys. Chem. Miner.39, 131 (2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data in this study are provided in Source Data file. They are also publicly available at https://github.com/rocky-xuan/Back-to-chromite and https://zenodo.org/records/14744274. Source data are provided with this paper.

The source code for locally executing AI4Min-Cr is publicly available at https://github.com/rocky-xuan/Back-to-chromite and https://zenodo.org/records/14744274.