Abstract

Background

Device-based embolization is a well-established medical procedure for treating several pathological conditions, including cerebral and peripheral pseudoaneurysms, congenital defects, and active bleeding. Nonetheless, an intriguing and relatively underexplored application of coils and microparticles involves the preoperative reduction of blood supply to ectopic masses.

Case summary

A 58-year-old woman was admitted to our institution with nausea and confusion, with a suspected diagnosis of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. A computed tomography scan revealed a large mediastinal mass receiving blood supply from both the bronchial and coronary arteries. The mass was successfully excised surgically, following the embolization of the major feeding vessels using a combination of coils and microspheres.

Discussion

An uncommon presentation of a paraganglioma characterized by both mass effect and endocrine activity required a "neoadjuvant" treatment to ensure safer surgical management.

Take-home message

The percutaneous reduction of blood supply to tumoral mass could represent an effective strategy to guarantee a radical excision without major complications.

Key Words: cancer, cardiovascular disease, computed tomography, coronary angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention, thoracotomy

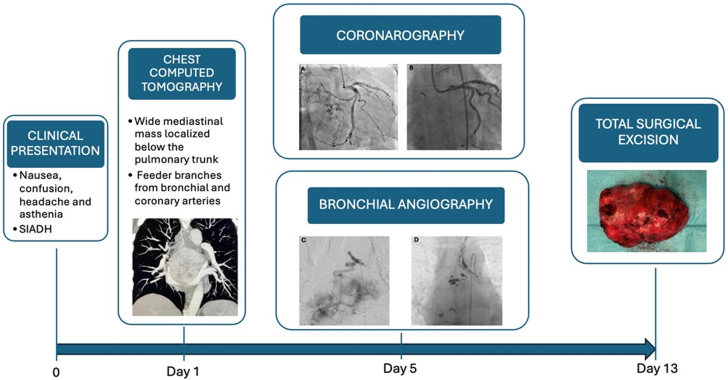

Visual Summary

Visual Summary.

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Steps Timeline From Clinical Presentation to Surgical Resection

History of Presentation

A 58-year-old woman was admitted to our institution with nausea, confusion, headache, and asthenia. Laboratory tests revealed a severe hypotonic hyponatremia (120 mmol/L) with urine hyperosmolarity. Renal, adrenal, and thyroid blood tests yielded normal results, while the water deprivation test produced a positive response. Given these findings, the most likely diagnosis was syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH).

Learning Objectives

-

•

To be able to identify the best therapeutic option for the patient through collaborative efforts within a multidisciplinary team.

-

•

To emphasize device-based embolization as an effective strategy for mitigating substantial blood loss during surgical procedures.

Past Medical History

The patient was a previously healthy and active woman. Her medical history was notable only for chronic urolithiasis. She was not undertaking any home-based therapies.

Differential Diagnosis

The etiology of SIADH encompasses neuropsychiatric disorders, pulmonary diseases, malignant neoplasms, small cell lung cancer, surgical procedures (as intense postoperative pain and nausea are physiological stimuli for antidiuretic hormone secretion), and antidepressant use.

Investigations

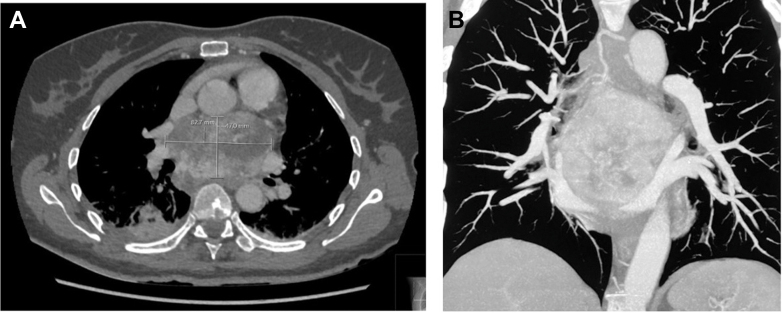

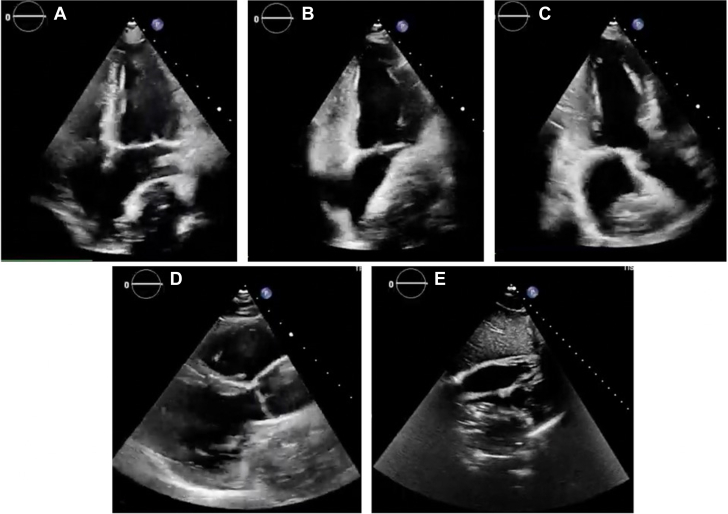

Chest computed tomography revealed a large mediastinal mass (height × width × depth: 84 × 57 × 77 mm) located beneath the pulmonary trunk exhibiting significant necrotic areas and dual blood supply originating from bronchial and coronary arteries (Figure 1). The left atrium was compressed by the mass but not overtly infiltrated. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated normal cardiac function without any relevant valve impairment (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Cardiac Computed Tomography Showing a Huge Mediastinal Mass Below the Pulmonary Trunk

Mass size: 84 × 57 × 77 mm. (A) Axial view. (B) Coronal view.

Figure 2.

Transthoracic Rest Echocardiography With Evidence of an Undefined Mass Compressing the Left Atrium

(A) 4-chamber view. (B) 2-chamber view. (C) 3-chamber view. (D) Long-axis parasternal view. (E) Subcostal view.

Management

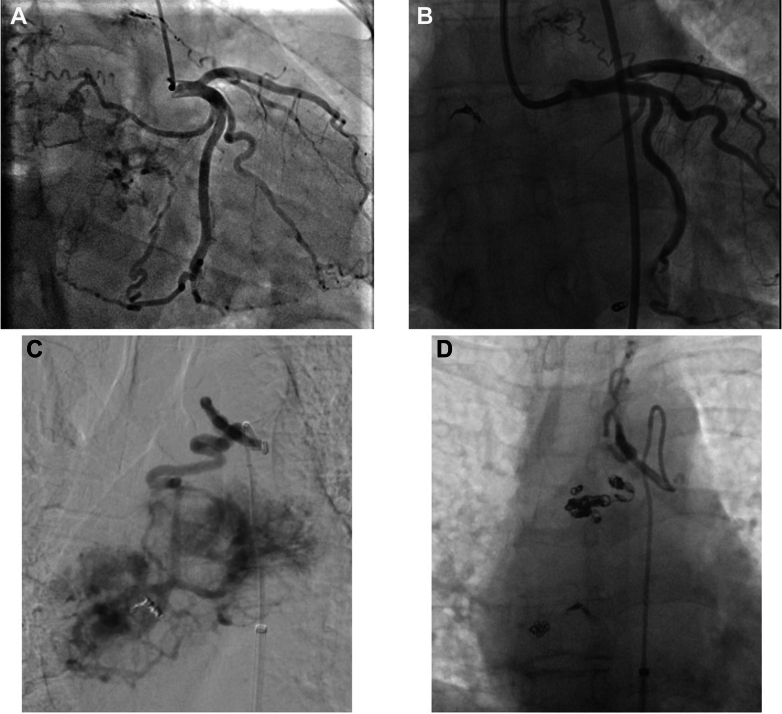

An endobronchial biopsy was planned to obtain a sample for histological analysis. However, the endobronchial approach proved to be unfeasible, and a right thoracotomy was used to acquire tumor specimens. Three biopsies were successfully obtained, despite copious bleeding. Histological examination suggested the presence of an extra-adrenal paraganglioma. Considering the computed tomography findings and the increased risk of substantial bleeding from feeding vessels, the patient underwent coronary and bronchial artery angiography (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Angiography of the Vessels Supplying the Mediastinal Aortopulmonary Mass

(A) Pre-embolization coronary angiography: 2 afferent vessels arising from the circumflex artery and 1 originating from the descending anterior artery leading to the mass. (B) Postembolization coronary angiography of the feeder branches from the circumflex artery. (C) Pre-embolization bronchial angiography. (D) Postembolization bronchial angiography.

Coronary angiography

No significant coronary artery stenosis was found. The coronary blood supply to the mass was provided by two feeding vessels originating from the circumflex artery (Cx) and one from the left anterior descending artery (Figure 3).

Utilizing a 6-F sheath and a Launcher EBU 3.5 guiding catheter (Medtronic) a Finecross microcatheter (Terumo Interventional Systems) was advanced on a SUOH03 guidewire (Asahi Intecc) in the feeding vessel supplied by the Cx. Two detachable coils in the proximal branch (3.0 × 6 and 2.0 × 8 mm) and 1 in the distal branch (3.0 × 6 mm) were successfully released (Target 360 Ultra; Stryker Neurovascular). Multiple unsuccessful attempts were made to reach the last feeding vessel originating from the proximal left anterior descending artery. However, due to its small caliber, the operators decided to leave it untreated. Final angiography showed a successful embolization without residual perfusion from the treated branch vessels originating from the Cx (Figure 3).

Bronchial angiography

A 7-F sheath, 45 cm in length, was positioned in the right common femoral artery. The right superior bronchial artery originating from the terminal part of the aortic arch was catheterized with a 5-F Mikaelsson catheter (Angiodynamics). Subsequently, the mass feeder branch was accessed by a 2.4-F microcatheter (Progreat, Terumo) and embolized using the following embolic agents: 700-μm Embozene microspheres (2 vials) (Boston Scientific), 300- to 500-μm Embozene microspheres (1 vial), and 355- to 500-μm Contour PVA particles (1 vial) (Boston Scientific). Due to the persistent delayed opacification of the mass, 2 additional undersized nondetachable Nester coils (Cook Medical) (3 × 2mm and 2 × 3 mm) were released distally, whereas a larger nondetachable Nester coil (Cook Medical) (4 × 5 mm and 2 × 6 mm) was used proximally.

The embolization was completed using a small amount of 250- to 355-μm Contour PVA particles to fix the remaining supplying vessels originating from the right bronchial artery and intercostobrachial trunk. Final angiography showed no significant mass blood supply from the bronchial artery branches. Femoral access was closed with an 8-F AngioSeal (Terumo). The patient tolerated the procedure without electrocardiographic changes.

The effectiveness of feeding branch embolization to the mediastinal mass was demonstrated by angiography, which showed near-complete cessation of blood flow in the coronary and bronchial branches. This finding was further corroborated by a follow-up contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan, carried out the day after the procedure, which revealed a reduction in the mass size (1 cm in the anteroposterior view) and the presence of liquefied areas indicating complete tumor devascularization. Furthermore, a triangular consolidation in the middle lobe of the lung was observed, suggesting a pulmonary infarct due to an effective embolization of bronchial artery branches.

Surgical procedure

Two days after the interventional procedures, the patient underwent a complete surgical en bloc excision, with median sternotomy, extracorporeal circulation, and cardioplegic arrest. Due to the posterior position of the mass and the absence of a distinct cleavage plane, a complete transection of the pulmonary artery and the ascending aorta at the level of the sinotubular junction along with manipulation of the left atrium was performed. Following tumor excision, reconstruction of the left atrium and the left superior pulmonary vein was achieved using a double pericardial patch (Figure 4). Histological and immunophenotypic (chromogranin A+, synaptophysin+, focal GATA-3+, CA IX, S-100+; Ki67: 3%) analysis confirmed the diagnosis of paraganglioma.

Figure 4.

Specimen of the Mediastinal Mass After Surgical Excision

Outcome and Follow-Up

At the 3-month follow-up, the patient showed no symptoms associated with the mediastinal paraganglioma, with no signs of edema or abnormalities in vital parameters. Blood and urine samples for sodium content evaluation were collected, showing serum sodium levels within the lower limits of normal range. The previously mentioned findings allow us to conclude that the final diagnosis was a paraneoplastic SIADH. A 1-year follow-up visit was scheduled.

Discussion

Paragangliomas are highly vascularized neuroendocrine tumors deriving from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla or extra-adrenal paraganglionic tissue. These tumors can occur in various locations, including the abdomen, pelvis, thorax, head, and neck.1,2 Mediastinal paragangliomas are extremely rare, and frequently found in the middle and posterior mediastinum, with only a few cases in the literature resembling the presentation in our patient.3, 4, 5 The majority of mediastinal paragangliomas (50%-80%) lack endocrine activity, primarily causing mass effects, while functional ones predominantly secrete catecholamines. However, there have been some instances in which patients presented with hyperglycemia or vasoactive intestinal peptide secretion.

In our experience, the diagnosis of paraganglioma was supported by signs and symptoms of a SIADH of paraneoplastic origin.6 Occasionally, mediastinal paragangliomas derive their blood supply from the coronary or bronchial arteries. Such cases pose significant challenges due to the close proximity between the great vessels and trachea and complicate complete resection with negative margins. Paragangliomas are generally highly vascularized, prompting the importance of considering preoperative embolization to facilitate subsequent surgical management, as performed in our case.3, 4, 5 A case reported by Kumar et al7 involved a similar management of a smaller catecholamine-secreting subcarinal paraganglioma with arterial supply provided from the right coronary artery and bronchial arteries. Preoperative embolization using coils and particles was performed on the vessel originating from the right coronary artery, though attempts to embolize the bronchial arteries by interventional radiology were unsuccessful due to technical challenges.7 A small case series by Aydemir et al8 described 9 cases of tumors with different location (1 of which was a paraganglioma) that were treated with successful preoperative coil embolization of feeding branches. Detachable coils are a valuable tool in both acute and elective cases, enabling the management of bleedings and fistulas or anomalous vessel embolization.9,10

Currently, there is no standardized method to reduce the risks associated with surgical resection of vascularized tumors. Existing case series suggest a tailored approach based on tumor location (mediastinal, thoracic, abdominal) and its relationship with major vessels (aorta, vena cava). In the absence of neoadjuvant therapies, the best approach is cautious resection, halting if excessive bleeding occurs. In this instance, the biopsy alone caused significant hemorrhaging that endangered the patient's life. Thus, preoperative arterial embolization proved to be a safe and effective approach for the patient, despite the lack of randomized controlled trials to support its use.

Conclusions

Preoperative embolization of vessels supplying blood to ectopic, highly vascularized masses is a safe and effective strategy to mitigate potentially critical blood loss during surgical procedures. A multidisciplinary approach is strongly suggested to guarantee the best diagnostic and therapeutic approach to the patient.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgment

The patient has provided informed consent to use clinical information for research purposes.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Shi W., Hu Y., Chang G., Zheng H., Yang Y., Li X. Paraganglioma of the anterior superior mediastinum: presentation of a case of mistaken diagnosis so long and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;103 doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.107900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melillo F., Spoladore R., Margonato A. Multimodality imaging of aortopulmonary paraganglioma. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;66(April):e1–e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho M.Y., Fleischmann D., Forrester M.D., Lee D.P. Coil embolization of a left circumflex feeder branch in a patient with a mediastinal paraganglioma. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(12):1345–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumoto J., Nakajima J., Takeuchi E., Fukami T., Nawata K., Takamoto S. Successful perioperative management of a middle mediastinal paraganglioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(3):705–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohra D.V., Srikrishna S.V., Kaskar A. Management dilemma in case of a posterior mediastinal paraganglioma. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2019;27(7):612–615. doi: 10.1177/0218492319862703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelosof L.C., Gerber D.E. Paraneoplastic syndromes: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(9):838–854. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senthil Kumar G., Rokkas C.K., Sheinin Y.M., Linsky P.L. Rare and complicated functional posterior mediastinal paraganglioma. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(6) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2022-250500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aydemir B., Sahin S., Çelik M., Okay T. Preoperative embolization to reduce morbidity and mortality in hypervascular mediastinal tumor surgery. Turkish J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;25(4):627–632. doi: 10.5606/tgkdc.dergisi.2017.13928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loh S.X., Brilakis E., Gasparini G., et al. Coils embolization use for coronary procedures: Basics, indications, and techniques. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;102(5):900–911. doi: 10.1002/ccd.30821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flanagan S., Golzarian J. Coil technology: sizes, shapes, and capabilities. Endovasc Today. 2022;21(4):48–52. [Google Scholar]