1. Background

When searching for the term “muscle power” on Google Scholar, about 3.7 million hits come up in 60 ms, and for the past 3 years, there were approximately 225 yearly peer-reviewed publications dealing with muscle power. Muscle power has been used to assess and predict athletic performance, to determine muscle rehabilitation following injury or disease, to measure functional decline as occurs in aging, and many other topics. In 1984, Alan McComas and colleagues from McMaster University organized a conference entitled “human muscle power”. It was the first muscle conference I (Walter Herzog) attended, and probably the first that dealt with muscle power exclusively. The distinct memory that remains from that conference is the confusion the term “muscle power” generated, a confusion that was caused by scientists from different disciplines interpreting power in different ways and rarely defining it.

Advancing 40 years, Ronei Pinto and colleagues organized an international symposium on muscle power at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in 2024. Like for the first conference 40 years earlier, muscle researchers from a variety of fields, including biomechanics, physiology, strength and conditioning, biochemistry, and energetics, were represented. Once again, the use of the term “muscle power” differed from one field to another, and few speakers defined it. Moreover, muscle power was associated with performance criteria such as the height achieved in a vertical jump or the change in kinetic energy and linear momentum of a system, criteria that do not depend on, and do not relate to, muscle power in a causal (mechanical) manner, resulting in misunderstandings between researchers across disciplines.

The purpose of this paper is to clarify what “mechanical power” is, how it is defined, and how it may be used in the proper physical sense in muscle mechanics. This definition may then be a guide for how the term “muscle power” may be/should be used to avoid further confusion.

2. Definition of power

Power (P) is defined as the time rate at which work (W) is done. It is the time (t) derivative of work:

| Eq. (1) |

And the work done by a force (F) is:

| Eq. (2) |

Where ∮ designates a line integral, and dx is an infinitesimal change in displacement (note that vectors are given in bold italic font and scalar quantities in regular font). Work, like power, is a scalar quantity that is based on the scalar product of 2 vectors.

From Eqs. (1) and (2), it follows that:

| Eq. (3) |

Thus, the mechanical power of a force is given by the scalar product of the force and velocity vectors. Power is an instantaneous scalar quantity with the units of Newton meters (N·m) per second (N·m/s); or Joules (J) per second (J/s), which is the definition of Watts (W). Work is a scalar interval quantity with the units of N·m or J.

3. Muscle power

Using Eq. (3), muscle power may then be defined as the scalar product of the muscle force vector, designated here as Fm, and the shortening/lengthening velocity of the muscle, vm. In the case of muscle contraction, we can assume that Fm and vm are on the same line of action. For example, during concentric contraction, the force and velocity are in the same direction (i.e., the angle, α, between the force and velocity vectors is α = 0°) and for eccentric, contraction the muscle pulls in the opposite direction of the length change (i.e., the angle, α, between the force and velocity vectors is α = 180°). Therefore, the scalar product Fm·vm reduces to the product of the force magnitude (Fm scalar) and speed (vm scalar) because the scalar product Fm·vm is equivalent to the product of Fm·vm·cos(α). Since cos(0°) = 1.0 and cos(180°) = –1.0, the original vector scalar product for the power of a muscle reduces to the product of the magnitudes of the muscle force and velocity, and power is positive for a shortening muscle and negative for a lengthening muscle because of the value of cos(α) for these 2 conditions (+1 and –1, respectively).

3.1. Muscle power and the force‒velocity relationship

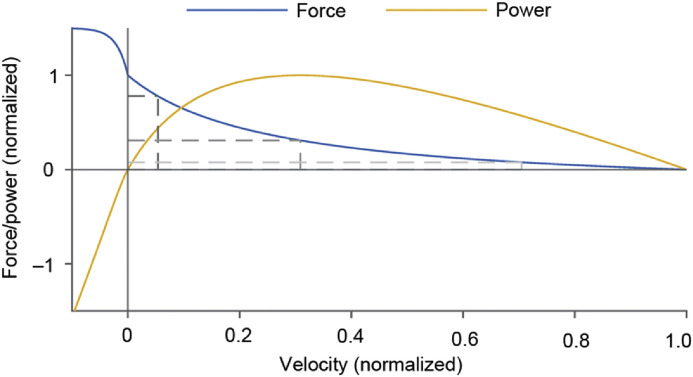

The force‒velocity relationship of skeletal muscles has been described for more than a century but was brought into sharp focus by the seminal paper by Hill.1 While studying the heat of shortening and energetics of muscle contraction, Hill found that the velocity at which a muscle shortens against a constant resistive force decreased in a hyperbolic manner with increasing force or, vice versa, that a muscle's capacity to produce external force decreased with increasing speeds of shortening (Fig. 1). Scientists then determined a power‒velocity relationship by multiplying each force value obtained in force‒velocity experiments by the corresponding value for the speed of shortening or elongation, resulting in a curve that is 0 when either the force or the velocity is 0, reaching a peak value for power at about 30%–35% of the maximal unloaded speed of shortening or 30%–35% of the maximal isometric force, and becoming negative when the muscle is stretched (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of a force‒velocity (blue) and the corresponding power-velocity relationship (yellow) of a muscle. The force is normalized to the maximal isometric steady-state force, the velocity is normalized to its maximal unloaded shortening velocity, and power is normalized to its peak value. The force‒velocity relationship was obtained by multiplying the force and velocity at each point of the force‒velocity relationship to obtain the power value as a function of velocity.

Even though there is nothing wrong with defining muscle power using the force‒velocity relationship, it is prudent to consider what the power‒velocity relationship obtained in this manner signifies. Hill's1 force‒velocity relationship and many others derived in a similar manner contain the following assumptions: (a) the muscle is maximally activated, (b) force and velocity of shortening are at a steady-state when measurement occurs, and (c) the relationship is obtained at optimal muscle length (i.e., a length at which the muscle can produce its maximal active isometric force). Deviations from these assumptions need to be carefully stated and accounted for because they lead to different force‒velocity curves. Obviously, these conditions are rarely if ever satisfied in actual human movements. Therefore, the force‒velocity relationship obtained in this manner should be considered the power “capacity” of a shortening muscle activated maximally at steady state and optimal length as a function of its speed of shortening. But it does not reflect the capacity of a muscle to produce mechanical power in a real-life situation. For example, the maximal power that can be achieved by a muscle in a stretch-shortening cycle can vastly exceed the maximal power obtained from a muscle's force‒velocity property.

Nevertheless, using the force‒velocity approach to derive the corresponding power‒velocity relationship has some undeniable advantages. For example, it allows for the evaluation of power capacity as a function of a muscle's maximal speed of shortening and/or maximal isometric force. For example, in a muscle with a reduced speed of unloaded shortening from an assumed fast fiber type to an assumed slow fiber type, there will not only be a reduction in the peak power capacity of more than 60%, but there will also be a shift in the peak power capacity to a smaller absolute shortening velocity (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Force‒velocity (blue) and corresponding power-velocity scenarios (yellow) of a “fictitious” human vastus lateralis muscle with a maximal force of 1250 N and a maximal shortening velocity of its fibers assumed to be 160 cm/s (fast fibers) and 60 cm/s (slow fibers). (A) depicts the scenario where the maximal force of the muscle remains constant but in one case all fibers are of the fast type, and in the other, they are of the slow type. Note that the peak power of the slow-twitch-fibered muscle is merely 37.5% of that of the fast-twitch-fibered muscle, and that peak power occurs at a much smaller absolute speed of shortening for the slow- compared to the fast-twitch-fibered muscle. (B) depicts the situation where the maximal velocity of shortening of the muscle is maintained, but the maximal force is reduced from 1250 N to 750 N. Here, the peak power is reduced by 40% for the “weak” compared to the “strong” muscle, but in contrast to (A), the peak power occurs at the same shortening velocity for both the weak and the strong muscle. (C) depicts the scenario where one muscle is 30% weaker and has a 30% reduced maximal velocity of shortening, mimicking what happens to a muscle for a person who is about 75 years old. Here, the peak power is reduced by 51% and occurs at a smaller velocity of shortening for the “old” compared to the “young” muscle.

Now consider a muscle with a reduced maximal isometric force. In this case, the muscle will have a corresponding decrease in power at all speeds but will maintain the speed at which maximal power occurs (Fig. 2B). With aging, people lose force capacity and speed of shortening simultaneously. Assuming a decrease of 30% in the maximal isometric force at optimal length as well as a 30% loss in maximal unloaded shortening speed, which are realistic values for people around the age of 75 compared to young people, the corresponding loss in peak power capacity obtained using the force‒velocity property is approximately 51% (Fig. 2C). The loss in peak power capacity (P0) can be calculated readily from the hyperbolic force‒velocity relationship, as proposed initially by Hill1 and is given by:

| Eq. (4) |

Where F0, v0, and C are the maximal isometric force of a muscle at optimal length, the maximal unloaded shortening velocity, and a constant that depends on the curvature of the hyperbolic force‒velocity relationship. Assuming that Hill's1 thermodynamic constants a and b are 0.25F0 and 0.25v0, respectively, as found by Hill1 and obtained in many other studies, the constant C becomes C = 0.095. Therefore, the peak power capacity derived in this manner becomes P0 = 0.095·F0·v0 from Eq. (4). The details of the mathematical derivation of peak power capacity from Hill's force‒velocity relationship are provided elsewhere.2 Note that Hill's1 force‒velocity equation is a rectangular hyperbola with asymptotes –a and –b, where a and b are the thermodynamic constants, as defined by Hill.1

3.2. Muscle power measurements in real life movements

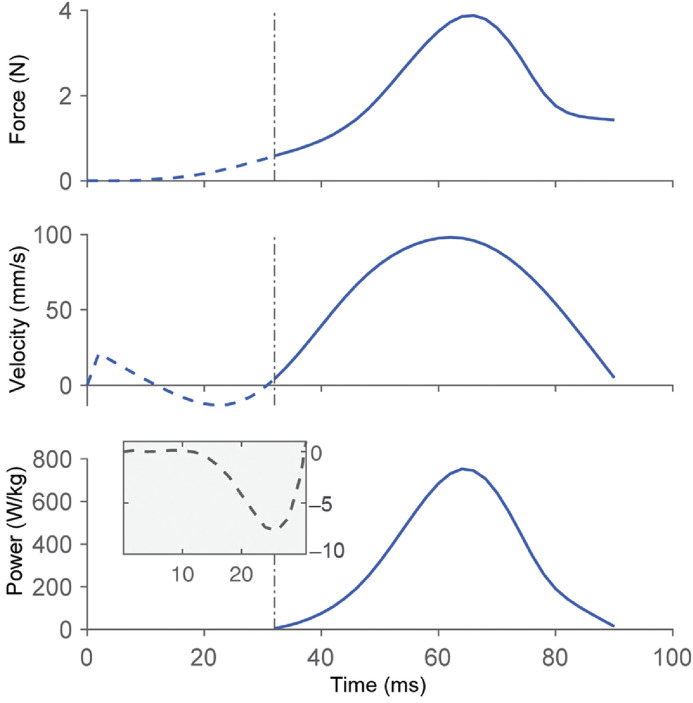

Measuring muscle power requires that the force and instantaneous rate of change in muscle length (velocity) are measured continuously. Direct measurements of power in a human muscle for everyday movements have never been made, although estimates of human muscle power are abundant.3 However, power output in animals can be obtained easily by continuously measuring the muscle force and rate of change in muscle length using, for example, muscle force transducers4 and sonomicrometry,5 respectively. Also, electromyographical recordings in conjunction with muscle length changes in vivo have been used to approximate the mechanical power of muscles by “replicating” the experimentally measured in vivo activation and length profiles ex vivo6,7 and then measuring the muscle forces in these simulated experiments. We measured muscle force and length changes in a variety of muscles and in different animals directly and then calculated the corresponding instantaneous power.8,9 Below is an example of a frog (rana pipiens) jumping (Fig. 3). The peak force for this 22 g frog and 0.5 g plantaris muscle was about 4 N, and the peak shortening velocity was about 100 mm/s; since peak force and peak shortening velocity occurred at almost the same instant in time, the peak power output of the plantaris in this example was about 800 W/kg muscle mass.9 In humans, such direct and accurate measurements of the power of a muscle are presently not possible.

Fig. 3.

Example of direct muscle force and velocity of contraction measurements in a frog (rana pipiens) plantaris muscle-tendon unit. Force was measured with a buckle type force transducer,8 and muscle length with sonomicrometry. Muscle power was then calculated by multiplying the instantaneous force of the muscle with the corresponding instantaneous velocity of muscle shortening or elongation. These data were first published by Moo and colleagues.9

3.3. Human muscle power testing

There are a great number of “field” tests that have been used to assess human muscle power. Two of these are the vertical jump and the Wingate bicycling test. There is no doubt that the height achieved in a vertical jump contains information about athletic ability for many short-term, high-intensity sports. But does it relate to mechanical power of the human system? It has been reported that there is a weak correlation (in the range of 0.04‒0.51) between peak mechanical power (measured using force platforms and high-speed videography) and the height achieved in a vertical jump.10 But why is that? Why do measurements of power, and peak power specifically, not relate closely to the height achieved in a vertical jump?

In a vertical jump, we start from a quiet position (i.e., the initial vertical velocity, v1, of the center of mass is v1 = 0 m/s) and we end with the vertical velocity at takeoff (vto > 0 m/s). The velocity vto uniquely determines the height of the jump or, more precisely, how far the center of mass will move upward from the instant of takeoff to the instant of peak height. Therefore, when a jumper goes from the initial vertical velocity, v1 = 0 m/s to a final velocity, vto, the system (i.e., the jumping subject) undergoes a change in linear momentum (mass multiplied by the linear velocity, m·v) or, equivalently, a change in linear kinetic energy, KE (1/2 mass multiplied by the linear velocity squared, KE = ½ m·v2) in the vertical direction. We can now use Newton's law of motion, F = m·a, as a scalar equation by just looking at the vertical component during a vertical jump and we obtain F = m·a.

From this most fundamental law in physics, we can now derive the impulse momentum relationship, which allows us to calculate the change in linear momentum of a person performing a vertical jump.

Starting with Newton's second law in the vertical direction, we have:

| Eq. (5) |

And since the acceleration a is the time derivative of speed, dv/dt, we rewrite Eq. (5) as:

| Eq. (6) |

Multiplying both sides of Eq. (6) by dt and integrating them, we obtain:

| Eq. (7) |

Where v2 is the vertical takeoff velocity (which we called vto above) and v1 = 0 m/s is the initial velocity for the vertical jump. Thus, we are left with:

Where is the resultant linear vertical impulse on the system, which for the vertical jump is given by the impulse due to the subject's weight and the vertical ground reaction force. In other words, the linear impulse by the external forces acting on the jumper uniquely determines vto, and thus the height achieved in the vertical jump.

The takeoff velocity, vto, can also be obtained using the work-energy principle. Starting again with Newton's second law Eq. (5), rewriting it as shown in Eq. (6), multiplying Eq. (6) by dr/dr = 1 (i.e., applying the chain rule for derivatives), and collecting terms in a convenient manner, we obtain:

| Eq. (8) |

Multiplying Eq. (8) with dr, integrating both sides, rearranging terms, and realizing that

results in:

If we assume again that the vertical jump starts with no vertical velocity (i.e., v1 = 0 m/s), we are left with

Where is the work performed on the system by all external forces, and is the jumper's vertical kinetic energy at takeoff. For both derivations, the impulse-momentum and work-energy principles, we assumed that m, the mass of the subject, is a constant.

In summary, using a force platform for ground reaction force measurements and knowing the mass of a subject, we can either use the impulse-momentum or the work-energy principle to get at the exact performance (height jumped) of a vertical jump. Note that both the impulse of a force and the work done by a force are interval quantities, in contrast to power, which is an instantaneous quantity. Also note that the change in linear momentum has units of kg·m/s or N·s and linear kinetic energy has the units of N·m or J. However, the unit of power is W, N·m/s, or J/s. In other words, the unit of power (W) is different from the units for linear momentum or kinetic energy, and thus “power” cannot be used to derive a change in linear momentum or kinetic energy through the laws of physics. In general, whenever a performance criterion in sport involves a change in the velocity of an athlete or an object, mechanical power cannot be used to calculate that change. Therefore, when we encounter statements in the literature like, “…to produce these rapid increases in kinetic and potential energy, the muscles…must generate a high level of mechanical power”,7 we know what the authors intended to say, but we also know that it is not mechanical power that provides the change in kinetic and potential energy; rather, it is the work done on the system or the impulse that changes the system's momentum.

Wingate test: Exercise physiologists frequently use the so-called Wingate test to measure “anaerobic power”. The test traditionally consists of a 30-s maximal cycling effort on a bike ergometer against a fixed (frictional) resistance. “Peak power” is then calculated for 5 s intervals across the 30-s test and “mean power” is determined over the entire 30-s test duration by multiplying the resistive force by the distance traveled (calculated by the number of wheel revolutions multiplied by the circumference of the wheel, or the “distance traveled per revolution”). The simplicity of the test has led to its wide use and a Google Scholar search for “Wingate test” resulted in almost 100,000 hits in 80 ms and 173 scientific papers published between 2021 and 2023. However, by definition, the peak power calculated in this manner is not an instantaneous value, and thus it is not comparable to “power” as defined in physics. One might call it the mean power over the 5 s evaluation period, or maybe more accurately, the work the athlete performed in the 5 s (or 30 s) testing period.

Furthermore, Wingate tests are performed against a fixed external resistance (frictional force). However, the peak power capacity of a muscle depends strongly on the resistive force (or the speed of contraction; Fig. 1) and so does the peak power capacity of an athlete during the Wingate test (Fig. 4). Specifically, the resistive force at which athletes achieve their true peak power differs depending on the properties of their muscles (e.g., the fiber type distribution). As illustrated in Fig. 2A, a primarily fast-twitch-fibered athlete would be expected to reach peak power at a greater resistive force and a higher velocity of muscle shortening than a primarily slow-twitch-fibered athlete, even if their muscle size and isometric force are the same. Similarly, athletes with different muscle properties may reach their peak power capacity at different resistive forces even though their absolute peak power capacity may be the same, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Force (given as resistive load in kg) and speed of contraction (given here as pedaling rate in revolutions per minute (RPM)) are used in Wingate testing to determine an average “power” over a specific period of time. Two exemplar (linear) functional force‒velocity relationships are shown: one a strong but slow athlete (solid blue line and diamond symbols) and the other a weak but fast athlete (intermittent blue line and filled circular symbols). Note how the strong/slow athlete reaches peak power at a resistive load of 6 kg (solid yellow line and light diamond symbols) while the weak/fast athlete reaches peak power at a resistive force of 5 kg (intermittent yellow line and solid circular symbols). If these 2 athletes were tested at low resistive forces (below 5 kg), the weak but fast athlete would have a greater power capacity than the strong but slow athlete, while the opposite would be true if the athletes were tested at a resistive force of 6 kg or higher. In actuality, the example was chosen such that the 2 athletes have the same peak power capacity if tested at their individual optimal condition (resistive force). This example not only illustrates the importance of the resistive force on the peak power capacity but also demonstrates that the power capacity between 2 athletes when tested at one resistive load might offer a different result than when tested at another resistive load. Please note that the data shown here are fictional, but the values chosen are within physiological limits for human cycling.

4. Summary

Power is defined as the time derivative of work. It is an instantaneous scalar quantity with units of J/s or W. The mechanical power of a muscle is obtained by multiplying the instantaneous force of a muscle by its rate of change (velocity) of shortening or elongation. Power cannot be directly used to determine the system's change in kinetic energy or linear momentum as occurs, for example, in a vertical jump test, which explains the small correlation coefficients between measures of mechanical power and height achieved. In contrast, the work performed, or the impulse generated on a system (e.g., for an athlete performing a vertical jump), will exactly provide the change in kinetic energy or linear momentum, and thus the height achieved, as these relationships are simply direct applications of Newton's second law of motion.

Scientists in different fields of exercise and sports science use the term “power”, measure “power”, or define “power” in different ways — often, ways that are not in accordance with the definition of classical mechanics. This was the situation in 1984 at McMaster University and again 40 years later at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. One could argue that scientists should always use terms from mechanics in the way they are defined to avoid confusion. However, this has proven unsuccessful in the different areas of sport science research over the past 40 years and likely will remain unsuccessful in the future because every scientific field has a “jargon” of its own (i.e., expressions that are not understood by the non-initiated and that sometimes are not used in accordance with precisely defined (mechanical) quantities). But we can and should require definitions for these terms. Specifically, transparency in science requires that when using the term “power” in a way other than its defined mechanical meaning, we must at least explain what we mean by “power” and how it was measured in the given scientific context. Finally, in the field of physics and all areas of mechanics (biomechanics, muscle mechanics, biophysics, etc.), we must insist that scientists adhere to the precise definition of the term “power”.

Authors’ contributions

WH conceived the argument, drafted, and revised the manuscript; AJ reviewed the mathematics, edited the initial draft; and created the figures. Both authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the author order.

Competing interests

Both authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

References

- 1.Hill AV. The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle. P Roy Soc London. 1938;126:136–195. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herzog W. In: Biomechanics of the Musculo-skeletal System. Nigg BM, Herzog W, editors. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, England: 2007. Muscle; pp. 169–225. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sargeant AJ. Human power output and muscle fatigue. Int J Sports Med. 1994;15:116–121. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walmsley B, Hodgson JA, Burke RE. Forces produced by medial gastrocnemius and soleus muscles during locomotion in freely moving cats. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41:1203–1216. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.5.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biewener AA, McGowan C, Card GM, Baudinette RV. Dynamics of leg muscle function in tammar wallabies (M. eugenii) during level versus incline hopping. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:211–223. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Askew GN, Marsh RL. The mechanical power output of the pectoralis muscle of blue-breasted quail (Coturnix chinensis): The in vivo length cycle and its implications for muscle performance. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:3587–3600. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.21.3587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lutz GJ, Rome LC. Built for jumping: The design of the frog muscular system. Science. 1993;263:370–372. doi: 10.1126/science.8278808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herzog W, Leonard TR, Guimaraes ACS. Forces in gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris tendons of the freely moving cat. J Biomech. 1993;26:945–953. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90056-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moo EK, Peterson DR, Leonard TR, Kaya M, Herzog W. In vivo muscle force and muscle power during near-maximal frog jumps. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knudson DV. Correcting the use of the term “power” in the strength and conditioning literature. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:1902–1908. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b7f5e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]