Abstract

Objectives

The “5-microskills” instructional method for clinical reasoning does not incorporate a step for learners’ critical reflection on their predicted hypotheses. This study aimed to correct this shortcoming by inserting a third step in which learners conduct critical self-examinations and furnish evidence that contradicts their predicted hypotheses, resulting in the “6-microskills” method.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, changes in learners’ confidence in their predicted hypotheses were measured and examined to modify confirmation bias and diagnoses. A total of 108 medical students were presented with one randomly assigned clinical vignette from a set of eight, having to: (1) describe their first impression; (2) provide evidence for it; and (3) finally identify inconsistencies/state evidence against it. Participants rated their confidence in their diagnosis at each of the three steps on a 10 point scale, and results were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures for two between-participant levels (correct or incorrect diagnosis) and three within-participant factors (diagnostic steps). The Bonferroni method was used for multiple comparison tests.

Results

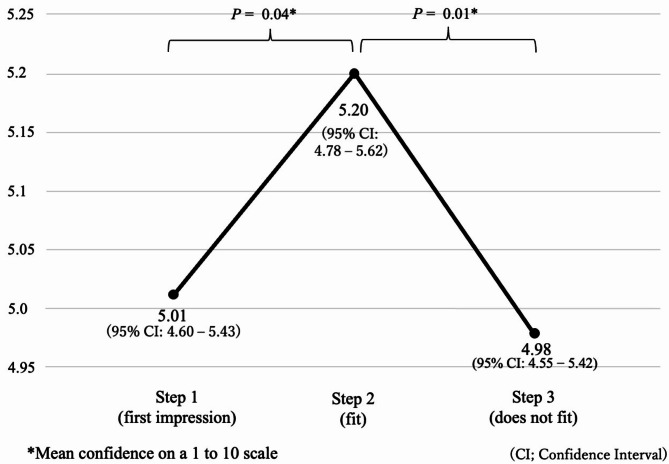

Mean confidence scores were 5.01 (Step 1), 5.20 (Step 2), and 4.98 (Step 3); multiple comparisons showed a significant difference between Steps 1–2 (P =.04) and 2–3 (P =.01). Verbalization of evidence in favor of the predicted hypothesis (Step 2) and against it (Step 3) prompted changes in diagnosis in four cases of misdiagnosis (three at Step 2, one at Step 3).

Conclusions

The 6-microskills method, which added a part encouraging learners to verbalize why something “does not fit” with a predicted diagnosis, may effectively correct the confirmation bias associated with diagnostic predictions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-06869-6.

Keywords: “5-microskills” method, “6-microskills” method, Critical reflection, Diagnoses, Clinical reasoning education, Cognitive bias, Confirmation bias

Introduction

A major challenge in teaching clinical reasoning is overcoming the pressure of time. Although outpatient facilities offer a large number of patients with common medical conditions representative of general medical practice [1], the time available for care and education in ambulatory care is more limited than in hospital wards. Therefore, efficient strategies are needed to teach clinical reasoning to medical students, residents, and physicians in outpatient settings. There are several methods that educators can implement in a short period to teach clinical reasoning, such as the one-minute preceptor model (OMP; also known as the 5-microskills method) [2] and the SNAPPS model [3]. These models guide appropriate teaching and make use of immediate, specific feedback, or engage the learner directly to identify learning needs within a short time. Subsequent research has shown that the 5-microskills model is more satisfying for learners and easier for the instructor to evaluate in comparison with traditional teaching methods [4, 5]. This method offers a strategy for effective clinical education within a short time. It consists of five steps: (1) stating the predicted hypothesis; (2) stating the evidence for this hypothesis; (3) teaching general rules; (4) reinforcing what had been done right; and (5) correcting mistakes. Learners perform the first two steps, and instructors perform the last three.

Additionally, clinical reasoning is related to critical thinking skills, which are defined as one’s capacity to engage in higher cognitive skills such as analysis, synthesis, and self-reflection [6]. Trainers usually provide specific instructions in critical thinking through case-based discussions and other forms of communication between the supervising physician and the learner. The 5-microskills and SNAPPS models are quick and easy teaching methods; however, they do not provide specific strategies for critical thinking through self-reflection. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a tool to teach critical thinking in a short time and in a concrete manner. Croskerry [7] stated that cognitive errors leading to misdiagnosis are associated with failures in perception, heuristics, and biases, and collectively referred to these as CDRs (cognitive dispositions to respond), presenting a list of CDRs along with strategies to reduce misdiagnosis. The CDRs, including various biases, are highly diverse, with the list containing as many as 32 items. Recognizing these biases and finding effective debiasing methods contribute to patient safety by reducing misdiagnoses. Confirmation bias, according to Pilditch and Custers [8], is defined as “the retention of an erroneous belief through the overweighting of belief-congruent evidence,” and is said to involve cognitive and motivational mechanisms. Graber et al. [9] found that cognitive factors accounted for the greatest number of diagnostic errors in internal medicine, with premature closure (i.e., not considering differential diagnoses beyond the initial diagnosis) being the most common cause. Therefore, encouraging critical thinking about the initial hypothesis or first impression can help reduce diagnostic errors. Accordingly, we developed the “6-microskills” method, based on the 5-microskills model, with an additional step performed by the learner, namely Step 3 (“does not fit”), to encourage critical reflection on the predicted diagnosis (Fig. 1). We measured the change in confidence in one’s disease hypothesis and the effect of diagnosis review when learners were asked to verbalize the evidence in favor of (Step 2) and against (Step 3) the diagnosis. This validation clarifies whether the 6-microskills method, which can be administered with only a minimal addition of time over the 5-microskills, may have cognitive psychological effects that encourage re-evaluation of diagnoses or improve diagnostic accuracy.

Fig. 1.

Steps of the “6-microskills” method

Method

We conducted a cross-sectional study following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statement.

Participants

At Chiba University School of Medicine, students undertake a one-year clinical clerkship from the second half of the fourth year through the first half of the fifth year. This study targeted a single cohort of students from the same academic year who were in rotation in the Department of General Medicine between November 30, 2020, and November 12, 2021. Eight staff members at the Department of General Medicine, who had been physicians for at least six years, participated as facilitators. In this study, students were randomly assigned one of the eight cases and the students participated individually.

Study design and procedure

Medical students performed clinical reasoning on prepared clinical vignettes, and received one-on-one instructions from facilitators. The clinical vignettes comprised eight case summaries of diseases frequently encountered in daily practice, which were based on the Japanese book Pitfalls in Daily Medical Practice Learned from Missed Cases [10]; we assigned one vignette to each medical student. The selection of cases was conducted by the authors, focusing on diseases within the scope of those potentially included in the Japanese National Medical Licensing Examination. Each clinical vignette was characterized by its difficulty in intuitively recalling the correct diagnosis based solely on the chief complaint. We selected these cases because we thought they had the potential to induce cognitive biases such as availability bias, where students tend to prioritize familiar diagnoses, and confirmation bias, where they overlook disconfirming evidence. Medical students were allowed 15 min to read and review the clinical vignette. During this time, they were permitted to research the medical case using any resources, including the internet. This study examines confirmation bias as a cognitive bias that arises during the rapid diagnostic process under time constraints. This type of confirmation bias includes a tendency to focus on known information due to limited opportunities to seek contradictory evidence. Subsequently, they performed the following three steps: in Step 1 (first impression), the respondents stated the most likely diagnosis (predicted hypothesis); in Step 2 (“fit”), the respondents had to state the point(s) that fit the predicted hypothesis; and in Step 3 (“does not fit”), respondents articulated the point(s) that did not fit the predicted hypothesis. Thus, Step 3 required medical students to list points that contradicted or could not be explained by their initial hypothesis. Students rated their confidence level regarding the predicted hypothesis at each step on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being the lowest and 10 being the highest confidence level). If the disease they considered to be most likely changed at any step, they were asked to record the changed diagnosis and their confidence level at that point in time.

Only the date, time, case number, and name of the supervising physician were written on the survey form, and the students did not write down their names. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Chiba University.

Study size

We calculated the sample size to be 28 with α = 0.05, 1-β = 0.80, partial eta squared = 06, and correlation between repeated measures = 0.50. All students participated voluntarily after having provided informed consent.

Data analysis

Students who recorded the correct diagnosis in the final step were classified into the correct diagnosis group, while those who recorded an incorrect diagnosis were classified into the misdiagnosis group. We compared confidence levels in the predicted hypothesis that participants considered most consistent with the vignette at each step. First, we used a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a two-level between student factor (correct or incorrect diagnosis), and a three level repeated measure (Steps 1–3). Next, as a sub analysis, a one-way ANOVA with repeated measures was performed for the correct and misdiagnosis groups, respectively, to compare the three factors in Steps 1–3.

The Bonferroni method was then applied to adjust P-values for multiple comparison tests. In addition, a participant was counted as having made a change in diagnosis if they amended the diagnosis they considered most likely at each step. We performed statistical analyses using SPSS Statistics for Windows 28.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA), setting the significance level for each analysis at adjusted P <.05.

Results

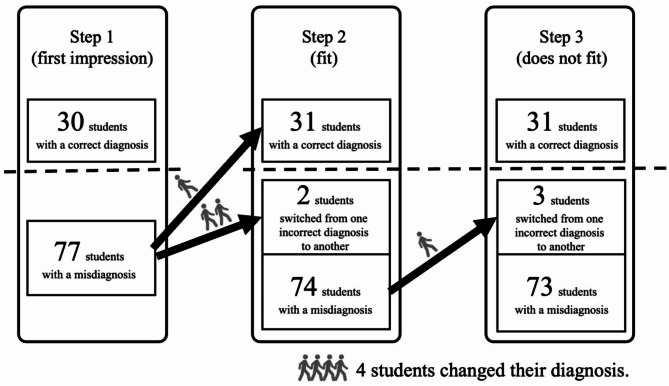

The total number of participants was 108; 107 (99%) provided valid responses (one participant did not complete the survey form; not stating confidence levels of the original diagnosis), with 12–15 responses per vignette (Fig. 2). A total of 31 participants (29%) arrived at the correct diagnosis by the end of Step 3. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures revealed no interaction between the correct diagnosis group and the misdiagnosis group, F(2, 210) = 0.37, P =.64, ηp2 = 0.004. The mean confidence level regarding the predicted hypothesis at each step was 5.01 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.6–5.43) for Step 1, 5.20 (4.78–5.62) for Step 2, and 4.98 (4.45–5.42) for Step 3. Multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method showed significant differences between Steps 1 and 2 (P =.04, Cohen’s d = 0.25, df = 106) and between Steps 2 and 3 (P =.01, Cohen’s d = 0.29, df = 106) (Fig. 3). The correlation between confidence levels across the steps (Step 1, Step 2, and Step 3) was analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Spearman’s rho) for both the correct and incorrect diagnosis groups. In the incorrect diagnosis group, the correlation coefficient between Step 1 and Step 2 was 0.933 (95% CI: 0.895–0.958, P =.000). Similarly, the correlation coefficient between Step 1 and Step 3 was 0.867 (95% CI: 0.795–0.915, P =.000), and between Step 2 and Step 3, it was 0.939 (95% CI: 0.904–0.962, P =.000). In the correct diagnosis group, the correlation coefficient between Step 1 and Step 2 was 0.945 (95% CI: 0.887–0.974, P =.000). The correlation coefficient between Step 1 and Step 3 was 0.864 (95% CI: 0.729–0.934, P =.000), while that between Step 2 and Step 3 was 0.930 (95% CI: 0.856–0.967, P =.000). In addition, a comparison between the correct diagnosis group and the misdiagnosis group showed that the correct diagnosis group was significantly more confident (P =.038) and, while there was no significant difference in confidence between Steps 1–2 (P =.93, Cohen’s d = 0.18, df = 30) and 2–3 (P =.21, Cohen’s d = 0.33, df = 30) in the correct diagnosis group, there was a significant difference in confidence between Steps 1–2 (P =.01, Cohen’s d = 0.36, df = 75) and 2–3 (P =.03, Cohen’s d = 0.31, df = 75) in the misdiagnosis group (Fig. 4). The outcome of significantly higher confidence levels in the correct diagnosis group was similar to a previous study by Friedman et al., who reported that the concordance between correct and incorrect diagnosis and confidence was κ = 0.314 [11].

Fig. 2.

Number of study participants and breakdown of answers for each case

Fig. 3.

Mean confidence level at each of steps 1–3 (first impression ⇒ fit ⇒ does not fit)

Fig. 4.

Mean confidence level by correct and incorrect diagnosis

We then examined changes in the predicted hypotheses from Steps 1 to 3. Four participants had misdiagnosed in Step 1, and changed their first impression in Steps 2 or 3: one changed the diagnosis in Step 2 to a correct diagnosis; two changed their diagnoses in Step 2, but still misdiagnosed; and the remaining one participant changed the diagnosis in Step 3, but still misdiagnosed (Fig. 5). Four participants each completed clinical vignettes for case 2 (carotid sinus syndrome), case 4 (reflux esophagitis), case 6 (acute pericarditis), and case 8 (polymyalgia rheumatica). No participants changed their diagnoses from correct to incorrect.

Fig. 5.

Timing of the diagnostic change and the number of students at each step who changed as a result of a single case of instruction

Discussion

This study developed the 6-microskills method by adding to the 5-microskills technique a further learner-performed step involving the verbalization of evidence against the predicted hypothesis. We found that this additional step could cause a slight yet statistically significant decrease in learners’ confidence levels regarding their diagnosis.

The first noteworthy finding in this study is the cognitive psychological changes that occur when learners were asked to state the diagnostic evidence for (Step 2) and against the predicted hypothesis (Step 3). We found that Step 2, which is also included in the 5-microskills method, increased learners’ confidence levels. This suggests that self-verbalization, a method to help learners think more deeply [12], may have contributed to the increase in confidence by encouraging learners to self-verbalize. In addition, Step 3: verbalization of discordance, which was added in the 6-microskills method, reduced learners’ confidence level compared to Step 2. All of these changes in confidence levels were slight but statistically significant. In psychology, cognitive dissonance is a well-known concept that describes the state of having contradictory cognitions at the same time in the self, and the discomfort experienced when this happens. When humans experience cognitive dissonance, they alter their thinking and behavior to resolve it [13]. This effect is thought to be related to the cognitive dissonance caused by having learners self-reflect on the “fit” and “does not fit” points to their predicted hypothesis.

The second interesting point is that for students who had the correct answer, confidence levels increased only slightly even when prompted by the instructor to list supportive features. However, for students who had the incorrect answer, confidence levels increased significantly (Fig. 4). In the correct diagnosis group, there were no significant changes in confidence levels between Steps 1–2 or Steps 2–3. Although the number of participants in the correct diagnosis group was more than twice as large as in the incorrect diagnosis group, as stated in the Methods section, the required sample size for this study was 28, and the correct diagnosis group included 31 participants, meeting this requirement. Therefore, the lack of significant differences in the correct diagnosis group is unlikely to be due to a β error but rather reflects the actual characteristics of the data. Confirmation bias refers to the tendency to attend to or seek only information that supports a hypothesis or belief when testing it, and to ignore or not look for information that disproves it. This suggests that when students have an incorrect answer, prompting them to list supportive features might strengthen their confidence levels through the occurrence of confirmation bias, not leading them toward the correct diagnosis. However, it is uncertain whether this finding would be replicated in another population. Especially in the case of a misdiagnosis, confirmation bias was considered to have the risk of increasing the confidence level in Step 2, where the learner was asked to state the basis for the diagnosis, thereby inducing the confirmation bias. In contrast, Step 3, which we incorporated in the 6-microskills method, may have the effect of reducing confirmation bias, especially when learners predict a misdiagnosis.

The third major finding is that in the self-reflective part of the 6-microskills, a single question has the potential to prompt diagnostic changes for a given case. In Step 2 (also included in the 5-microskills), wherein we asked participants to provide evidence for their predicted hypothesis, a revision of the first impression was conducted, albeit by a small number of participants. Previous studies have not clarified this point. Therefore, even in the 5-microskills method, which does not have a step for critical examination, the verbalization of diagnostic evidence in Step 2 can lead to a review of the diagnosis through self-reflection.

On the other hand, the expected effect of improving diagnostic accuracy by prompting learners to consider why a hypothesis might be incorrect and to switch to the correct answer did not occur. This may be because this study targeted students, and most of the eight cases were highly challenging for them, leading to no observed improvement in diagnostic accuracy. In this study, eight cases were prepared to mitigate the impact of differences in vignette difficulty on the results. For example, the diagnostic accuracy rate for Case 1 (acute sinusitis) was 71%, while for Case 7 (ovarian bleeding), it was 7%. In Case 1, no change in confidence level was observed during Step 3, which involves presenting evidence against the diagnosis, whereas in Case 7, a decrease in confidence level was noted. When the initial confidence level is high, learners tend to adopt the predicted diagnosis as the final diagnosis. On the other hand, when confidence is low, particularly in high-difficulty cases, the Step 3 intervention may influence learners’ confidence. However, as this study did not compare differences based on difficulty levels, this remains a topic for future research.

Additionally, while students were free to research the cases, including internet searches, they had to complete their answers within a limited 15-minute timeframe, which may have hindered sufficient analysis. Allowing more time for consideration or targeting junior doctors with clinical experience, such as residents, may offer a more accurate measurement of diagnostic accuracy improvement. As an alternative to paper tests, incorporating the 6-microskills method into the feedback process for new outpatient cases examined by residents and comparing the diagnostic concordance rate between residents and supervisors before and after feedback may be a useful approach. Furthermore, although the students in this study were largely exposed to the 6-microskills for the first time, instructing students at the beginning of their clinical training using the 6-microskills method and encouraging them to apply Steps 2 and 3 through self-questioning could enhance the utility of the 6-microskills and, as a result, improve the quality of clinical reasoning.

Additionally, the cognitive mechanism of confirmation bias includes an “asymmetry in evidence exposure,” meaning that a bias may arise when collecting information that has not been provided. In the study by Kostopoulou et al. [14], confirmation bias was examined in a context where physicians could request additional information. In contrast, in the present study, all information was presented to the students, observing only the effects of “selective attention to and integration of already known evidence consistent with the favored hypothesis.” Therefore, this study does not evaluate confirmation bias that may occur during information gathering in actual clinical practice.

Regarding the effect on correcting misdiagnoses, this study observed only slight changes. Of the 107 students, 72% made a misdiagnosis; in Step 2, one student changed to the correct hypothesis, but no students changed to the correct diagnosis in Step 3. In Step 2, two students changed to another incorrect diagnosis, and in Step 3, one student switched to an incorrect diagnosis. A noteworthy point is that only one student changed their diagnosis in Step 3. This suggests that while Step 3 may lead to a decrease in confidence levels, it does not produce enough of a change to prompt students to revise their diagnoses. As mentioned earlier, this may be due to students not being familiar with the method of Step 3, or because the students’ level of knowledge made it difficult for them to recall alternative differential diagnoses. Similarly, for confidence levels, although statistically significant in the predicted direction, the effect size was less than one point, indicating a small effect. In this study, confidence levels showed positive and/or negative changes in 50.5% of the 107 students; however, the overall small change could also be influenced by extreme changes from a few individuals (e.g., from 10 to 1), though no such cases were observed in this study. Moving forward, it may be necessary to evaluate using more objective indicators, such as the number of diagnostic changes made, rather than relying solely on confidence levels.

In this study, we examined the effectiveness of the 6-microskills method, which is based on the 5-microskills method with an additional Step 3 that requires students to provide evidence against the diagnosis as a short clinical reasoning educational tool. To our knowledge, no previous studies have used the OMP model to test the modification of confirmation bias. Although the observed effect of Step 3 is small, we consider this to be an important new finding in the right direction. Moving forward, more effective teaching interventions or a more sensitive measurement method will be necessary. Educators can provide clinical reasoning education using the 6-microskills method in a short time and in a concrete manner, by utilizing self-reflection. We plan to conduct further studies with residents and instructors to collate additional evidence, and to establish this approach as a tool that plays a part in lifelong education for physicians.

Conclusion

This study suggests that the 6-microskills method, which adds the verbalization of evidence against the diagnosis to the conventional 5-microskills method, may have the potential to correct confirmation bias. In particular, while confirmation bias may be reflected in high confidence in an incorrect diagnosis, adding Step 3, which encourages reflection on evidence inconsistent with the diagnosis, demonstrated a reduction in that overconfidence. However, there was no observed improvement in diagnostic accuracy, likely due to the limited clinical experience of the students and the high difficulty level of the cases. Future studies should include evaluations involving residents, as well as objective indicators such as the frequency of diagnostic changes. The results of this study suggest that the 6-microskills method could serve as a useful educational tool for correcting bias in clinical reasoning.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

JK, TU and MI conceptualized the study. JK, TU, and YO led the design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and the paper writing. JK, TT, KS, DY, YL, YY, and RS collected the data under supervision from JK and TU. JK, TU, and YO conducted the data analysis. All authors contributed to interpreting the data, and the drafting and critical revision of the paper. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The Research Ethics Committee of Chiba University Hospital approved this study (No. 4061, March 11, 2021). We provided each student with a document explaining the ethical considerations of the study. Participants provided informed consent before participation.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dent JA. AMEE Guide 26: clinical teaching in ambulatory care settings: making the most of learning opportunities with outpatients. Med Teach. 2005;27(4):302–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neher JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step microskills model of clinical teaching. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5(4):419–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolpaw TM, Wolpaw DR, Papp KK. SNAPPS: a learner-centered model for outpatient education. Acad Med. 2003;78(9):893–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furney SL, Orsini AN, Orsetti KE, Stern DT, Gruppen LD, Irby DM. Teaching the one-minute preceptor: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):620–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salerno SM, O’Malley PG, Pangaro LN, Wheeler GA, Moores LK, Jackson JL. Faculty development seminars based on the one-minute preceptor improve feedback in the ambulatory setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(10):779–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richards JB, Hayes MM, Schwartzstein RM. Teaching clinical reasoning and critical thinking: from cognitive theory to practical application. Chest. 2020;158(4):1617–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):775–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pilditch TD, Custers R. Communicated beliefs about action-outcomes: the role of initial confirmation in the adoption and maintenance of unsupported beliefs. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2018;184:46–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(13):1493–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikusaka M. Pitfalls in daily medical practice learned from missed cases. Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman CP, Gatti GG, Franz TM, et al. Do physicians know when their diagnoses are correct? Implications for decision support and error reduction. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(4):334–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hattie JAC, Donoghue GM. Learning strategies: a synthesis and conceptual model. NPJ Sci Learn. 2016;1(1):16013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostopoulou O, Sirota M, Round T, Samaranayaka S, Delaney BC. The role of Physicians’ first impressions in the diagnosis of possible cancers without alarm symptoms. Med Decis Mak. 2017;37(1):9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.