Abstract

Background

Cesarean section (CS) rate has become increasingly prevalent worldwide, which has raised concerns about the possible risks as they often result in frequently longer recovery periods for mothers and possible complications for both the mother and the child. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a 10–15% CS rate to maintain its safe use. Conducting trends analysis of CS and its associated factors is crucial in understanding its utilization. There is currently a limited knowledge on the increasing trends of CS and factors related to it that might help improve procedures and practice standards. The present study examined the trends and associated factors of CS use in the Philippines over the last two decades.

Methods

We utilized the Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey (PNDHS) data collected in 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2017. Descriptive and univariate techniques were used to characterize the survey participants and the trends of CS use over time. The data of 2017 PNDHS was used in the logistic regression analysis to assess the associated factors of CS use. Significant factors (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were considered in the logistic regression analysis.

Results

The overall use of CS has been significantly higher than the maximum cutoff of the WHO and increased from 15.8% in 1993 to 18.4% in 2017. Women aged 25 years or older, with higher education, belonged to middle or rich household, with newborn at 1 and 2–3 birth order, and with initial antenatal care visits (ANC) in the first or later trimester of pregnancy were significantly associated with CS use.

Conclusion

In the Philippines, the utilization of CS has continuously surpassed the recommended maximum cutoff of 15%. This increased rate is associated with maternal age, educational attainment, family income, birth order, and the timing of antenatal care visits. The socioeconomic factors demonstrate socioeconomic disparities in accessing CS services. Emphasizing the need for performing medically indicated CS can promote better maternal and child outcome and reduce the rate of unnecessary CS deliveries. Prioritizing initiatives to provide equitable access to CS services is imperative.

Keywords: Caesarean section, Trends, Demographic and health survey, Philippines

Background

Cesarean section (CS) is a surgical emergency obstetrical intervention to save the mother and child’s life [1, 2]. CS is indicated for the management of poor labor conditions such as obstructed labor, placental abnormalities, cephalopelvic disproportion, unsuccessful vaginal delivery, and abruptio placenta [3–5]. When not medically indicated, CS was found to increase the surgical delivery-related risks for both the mother and her child [6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a CS threshold rate between 10% and 15%, and that having < 10% and > 15% CS rate to be under- and over-utilization of maternal and child healthcare services, respectively [7]. However, in 2015, the WHO added that a > 10% CS rate was not associated with a reduction in maternal and newborn death rates [8].

According to a study that analyzed data from 154 countries, 21.1% of women globally gave birth through CS between 2010 and 2018 [1]. By 2030, it is projected that 28.5% or 38 million women worldwide will give birth through CS of which 33.5 million women are from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as sub-Saharan Africa (7.1%) and Eastern Asia (63.4%) [1]. While epidemiologists have raised concerns about the increasing CS rates, disparities in access to and utilization of obstetric care services have also been noted [9]. In Southeast Asian countries, women with higher education and income, live in urban areas, are closer to health facilities, and have family support are more frequently to have better access to maternal health services [10]. In the Philippines, there is a disparity in accessing maternal health services, with higher socioeconomic status being the primary driver of disparities in obstetric care services such as CS utilization [11].

The CS rate was found to be 4% higher in private than in public health facilities, highlighting disparities in access to quality care in the Philippines [12]. Examining CS rate at national level may not be appropriate in developing countries like the Philippines wherein there is disparities of CS utilization due to women’s characteristics. With the significant increase in CS rates globally and in the Philippines, it is necessary to assess differences in CS use across survey periods and various women’s characteristics. Therefore, we aim to examine the trends in CS rate in the Philippines over the last two decades using data from the Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey (PNDHS) conducted between 1993 and 2017. Furthermore, this study seeks to identify the factors associated with the use of CS using the 2017 PNDHS dataset. The findings provide valuable insights into the utilization patterns of CS, facilitating the development of evidence-based interventions to improve maternal and neonatal health.

Methods

Data source and participants

This study used the PNDHS child’s datasets collected in 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2017 with permission from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Data on maternal and childbirth history was gathered from 97,468 women aged 15–49 years, yielding a response rate of 97.9% on average. This study involved women who responded to the PNDHS question about their last CS in the previous 5 years and with complete data on the outcome variable.

Variables

The dependent variable was CS, dichotomously grouped as “Yes” or “No”. Women were asked whether they had undergone a CS procedure within the 5 years preceding the survey. We only assessed childbirths that took place in institutional-based facilities. The independent variables included in the study were identified from a review of literature on factors associated with CS use [1, 9, 13–16]. The independent variables included maternal age at child’s birth (15–24, 25–34, ≥ 35), mother’s marital status (single/not living together, married/living together), mother’s education (primary/below, secondary, higher), mother’s occupation (not working, working), household wealth (poor, middle, rich), residence (urban, rural), child’s birth order (1, 2–3, ≥ 4), time of initial ANC visit (first trimester, second/third trimester, don’t know), frequency of ANC visit (< 4, ≥ 4), and place of delivery (public health institution, private health institution).

In the DHS program, household wealth status is calculated using data on selected household assets, such as televisions, bicycles, and water sources, with principal component analysis (PCA) assigning a weight or factor score to each asset. The resulting asset scores are standardized and used to divide the population into five equal household wealth quintiles: poorest, second poorest, middle, richer, and richest [17]. In this study, the wealth quintiles were further grouped into three categories: ‘rich’ (combining the ‘richest’ and ‘richer’ quintiles), ‘middle’ (the ‘middle’ quintile), and ‘poor’ (combining the ‘second poorest’ and ‘poorest’ quintiles).

Due to the very small number of women initiating ANC visit during the third trimester, we combined the second and third trimesters into one category. This approach ensured sufficient sample size for reliable statistical analysis and more interpretable results.

Data analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis to characterize the survey participants. The chi-square test was used to compare the rates of CS between groups within each survey wave. Significant factors (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were considered in the multivariable logistic regression analysis. The 2017 PNDHS data was used to identify the factors associated with CS use. We performed data analysis through the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.

Results

We included a total of 19,785 women who had given births within five years prior to each interview across the survey periods with participants counts as follows: 2322 in 1993, 2286 in 1998, 2515 in 2003, 2658 in 2008, 4084 in 2013, and 5920 in 2017. The percentage of women with a secondary education increased from 35.5% in 1993 to 49% in 2017. Around half of the women were employed throughout the five waves of survey. However, the percentage of rich women decreased from 54.3% in 2003 to 34.0% in 2017. Household wealth status was not available for the 1993 and 1998 surveys. The percentage of women living in rural areas increased from 28.5% in 1993 to 60.5% in 2017, and the percentage of women giving birth to their second or third child slightly increased from 39.1% in 1993 to 43.0% in 2017. The majority of women had their first ANC in the first trimester of pregnancy, and at least 4 ANC visits in all survey periods. In 2013 and 2017, two-thirds of childbirths took place in public health institutions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of all women grouped by survey periods

| 1993 | 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total participants included | 2322 (%) | 2286 (%) | 2515 (%) | 2658 (%) | N = 4084 | N = 5920 |

| Mother’s age (years) | ||||||

| 15–24 | 471 (20.3) | 425 (18.6) | 579 (23.0) | 610 (22.9) | 1146 (28.1) | 1497 (25.3) |

| 25–34 | 1325 (57.1) | 1297 (56.7) | 1361 (54.1) | 1398 (52.6) | 1967 (48.2) | 2878 (48.6) |

| ≥ 35 | 526 (22.7) | 564 (24.7) | 575 (22.9) | 650 (24.5) | 971 (23.8) | 1545 (26.1) |

| Mother’s marital status | ||||||

| Single/not living together | 70 (3.0) | 90 (3.9) | 131 (5.2) | 202 (7.6) | 365 (8.9) | 482 (8.1) |

| Married/living together | 2252 (97.0) | 2196 (96.1) | 2384 (94.8) | 2456 (92.4) | 3719 (91.1) | 5438 (91.9) |

| Mother’s education | ||||||

| Primary/below | 448 (19.3) | 311 (13.6) | 314 (12.5) | 277 (10.4) | 555 (13.6) | 747 (12.6) |

| Secondary | 825 (35.5) | 835 (36.5) | 980 (39.0) | 1231 (46.3) | 2002 (49.0) | 2905 (49.1) |

| Higher | 1049 (45.2) | 1140 (49.9) | 1221 (48.5) | 1150 (43.3) | 1527 (37.4) | 2268 (38.3) |

| Mother’s occupation | ||||||

| Not working | 1089 (46.9) | 1078 (47.2) | 1299 (51.7) | 1245 (46.8) | 1982 (48.5) | 3020 (51.0) |

| Working | 1233 (53.1) | 1208 (52.8) | 1216 (48.3) | 1413 (51.5) | 2102 (51.5) | 2900 (49.0) |

| Household wealth status | ||||||

| Poor | 593 (23.6) | 772 (29.0) | 1548 (37.9) | 2696 (45.5) | ||

| Middle | 557 (22.1) | 574 (21.6) | 907 (22.2) | 1214 (20.5) | ||

| Rich | 1365 (54.3) | 1312 (49.4) | 1629 (39.9) | 2010 (34.0) | ||

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 1660 (71.5) | 1418 (62) | 1708 (67.9) | 1589 (59.8) | 2011 (49.2) | 2337 (39.5) |

| Rural | 662 (28.5) | 868 (38.0) | 807 (32.1) | 1069 (40.9) | 2073 (50.8) | 3583 (60.5) |

| Child’s birth order | ||||||

| 1 | 808 (34.8) | 834 (36.5) | 1002 (39.8) | 1060 (39.9) | 1549 (37.9) | 2157 (36.4) |

| 2–3 | 907 (39.1) | 896 (39.2) | 1010 (40.2) | 1071 (40.3) | 1705 (41.7) | 2548 (43.0) |

| ≥ 4 | 607 (26.1) | 556 (24.3) | 503 (20.0) | 527 (19.8) | 830 (20.3) | 1215 (20.5) |

| Time of initial ANC visit | ||||||

| First trimester | 1335 (57.5) | 1462 (64.0) | 1226 (48.7) | 1292 (48.6) | 2218 (54.3) | 3394 (57.3) |

| Second/third trimester | 933 (40.2) | 762 (33.3) | 588 (23.4) | 708 (26.6) | 1001 (24.5) | 1307 (22.1) |

| Don’t know | 54 (2.3) | 62 (2.7) | 701 (27.8) | 658 (24.8) | 865 (21.2) | 1219 (20.6) |

| Frequency of ANC visit | ||||||

| < 4 | 551 (23.7) | 436 (19.1) | 939 (37.4) | 861 (32.4) | 1133 (27.8) | 1650 (27.9) |

| ≥ 4 | 1771 (76.3) | 1850 (80.9) | 1576 (62.7) | 1797 (67.6) | 2951 (72.3) | 4270 (72.1) |

| Place of delivery | ||||||

| Public health institution | 1496 (64.4) | 1382 (60.5) | 1647 (65.5) | 1703 (64.1) | 2998 (73.4) | 4206 (71.0) |

| Private health institution | 826 (35.6) | 904 (39.5) | 868 (34.5) | 955 (35.9) | 1086 (26.6) | 1714 (29.0) |

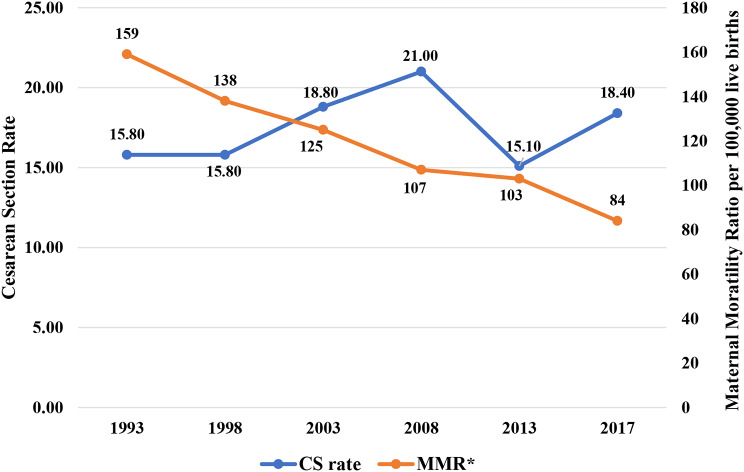

The overall rate of CS use has surpassed the maximum threshold of 15%, showing a rise from 15.8% in 1993 to 18.4% in 2017, peaking at 21% in 2008. Meanwhile, maternal mortality ratio (MMR) has significantly declined from 159 per 100,000 livebirths in 1993 to 84 per 100,000 livebirths in 2017 based on the report of the WHO [18] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overall cesarean section rate and maternal mortality ratio over time from 1993 to 2017

The CS rate shows significant variations across all years based on women’s characteristics, including age, education level, wealth status, timing of initial ANC, and number of ANC visits. Women aged ≥ 35 years had the highest CS use across all survey periods, ranging from 19.2% in 1993 to 25.4% in 2017. Women with higher education has increased from 19.4% in 1993 to 25.8% in 2017 with the highest rate at 27.4% in 2008. CS use among rich women has been consistently greater than 22% for the last decade, from 22.1% in 2003 to 27.4% in 2017. A notable increase in CS use is observed among women with newborns at the 2nd and 3rd birth order, rising from 17.2% in 1993 to 19.8 in 2017, reaching its peak rate of 24.6% in 2008. Regarding antenatal care, the proportion of women who had their first ANC visit during the first trimester of pregnancy rose from 18.2% in 1993 to 21.6% in 2017. Similarly, women who completed at least four ANC visits had the higher CS utilization in the last two decades, with rates of 16.8% in 1993, 17.1% in 1998, 21.4% in 2003, 24.9% in 2008, 17.0% in 2013, and 20.7% in 2017. CS utilization showed an upward trend in private health institutions, with minor declines in 2013 and 1998, respectively. In 1993, among women who gave birth in private health institution, 19.6% underwent CS, which decreased to 18.1% in 1998. However, the rate then exhibited an increase to 23.6% in 2003 and further to 28.8% in 2008. In 2013, CS use among women in private health institution was recorded at 22.7%, followed by a decrease to 21.1% in 2017. Although the CS use fluctuates over time, the rate of CS use remains to be more prevalent (> 18%) among women who gave birth in private health institutions when compared to those delivering in public health institutions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Rate of cesarean section (CS) by selected sociodemographic characteristics in 1993–2017 (* p < 0.001)

In the logistic regression analysis using the 2017 PNDHS data, it was demonstrated that women aged 25–34 years (Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.60–2.40) and those aged 35 and older (AOR 3.99, 95% CI 3.14–5.05) were found to be twice and four times as likely to undergo CS, respectively, when compared to women aged 15–24 years. Women with higher education (AOR 1.37, 95% CI 1.04–1.80) were more likely to deliver through CS compared to women with a primary/below level of education. Women from both middle (AOR 1.45, 95% CI 1.19–1.77) and rich (AOR 1.95, 95% CI 1.63–2.34) households demonstrated a significantly higher likelihood of delivering through CS compared to women from poor household. Similarly, women with newborn at first birth order (AOR 2.97, 95% CI 2.31–3.81), and those with newborn at 2–3 birth order (AOR 2.04, 95% CI 1.64–2.54) have increased probabilities of having CS as compared to women with newborn at 4 or later birth order. Concerning ANC, women who attended initial ANC visit during either the first or later trimester of pregnancy were more likely to deliver via CS as compared with those who were unsure about their first ANC visit (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for the association between cesarean section and selected sociodemographic factors using the 2017 PNDHS data

| COR | 95% CI | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | p-value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age (years) | ||||||||||||||

| 15–24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 25–34 | 1.70 | (1.41 -2.04) | < 0.001 | 1.96 | (1.60-2.40) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| ≥ 35 | 2.61 | (2.15 -3.17) | < 0.001 | 3.99 | (3.14 -5.08) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Mother’s education | ||||||||||||||

| Primary/below | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Secondary | 1.26 | (0.99 -1.62) | 0.062 | 1.01 | (0.77 -1.29) | 0.982 | ||||||||

| Higher | 2.64 | (2.07 -3.37) | < 0.001 | 1.37 | (1.04 -1.80) | 0.024 | ||||||||

| Mother’s occupation | ||||||||||||||

| Not working | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Working | 1.25 | (1.09 -1.42) | 0.001 | 0.93 | (0.81 -1.08) | 0.336 | ||||||||

| Household wealth status | ||||||||||||||

| Poor | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Middle | 1.76 | (1.46 -2.13) | < 0.001 | 1.45 | (1.19 -1.77) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Rich | 2.89 | (2.48 -3.37) | < 0.001 | 1.95 | (1.63 -2.34) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Birth Order | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1.75 | (1.43-2.14) | < 0.001 | 2.97 | (2.31-3.81) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| 2–3 | 1.78 | (1.46-2.17) | < 0.001 | 2.04 | (1.64-2.54) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| ≥ 4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Time of initial ANC visit | ||||||||||||||

| First trimester | 2.17 | (1.79 -2.64) | < 0.001 | 1.98 | (1.41 -2.79) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Second/third trimester | 1.59 | (1.26-2.00) | < 0.001 | 1.94 | (1.40-2.70) | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Don’t know | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Frequency of ANC visit | ||||||||||||||

| < 4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| ≥ 4 | 1.82 | (1.55 -2.15) | < 0.001 | 0.99 | (0.74 -1.32) | 0.942 | ||||||||

| Place of delivery | ||||||||||||||

| Public Health facility | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Private Health Institution | 1.28 | (1.11 -1.48) | < 0.001 | 0.90 | (0.77 -1.05) | 0.166 | ||||||||

COR: crude odds ratio; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; 1.00: Reference category; ANC: antenatal care

Discussion

The CS rate in the Philippine has witnessed an upward trend, rising from 15.8% in 1993 to 18.4% in 2017 with the highest peak at 21% in 2008. The findings of this study showed that over that past 25 years, women aged 35 or older, with higher education, fewer than 4 children, who were employed, and from wealthy households consistently exhibited higher CS rates. In addition, women who had their first ANC visit during the first trimester of pregnancy and completed at least four ANC visits were particularly likely to undergo CS.

Despite progress in reducing maternal mortality to 78 per 100,000 live births in 2020 via increased institutional-based childbirths [19, 20], the Philippines still strives to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of < 70 per 100,000 live births [21]. Previous studies found a comparable CS rate ranging from 19 to 23% [13, 22], but they did not illustrate the trend over the last two decades as our study did. In this study, the year 2008 stood out with the highest rate of CS at 21% which may be influenced by the implementation of a nationwide maternal and child health reform program that was introduced in the same year. As Philippines was one of the Southeast Asia countries that has the highest maternal death in 2008 [20], the government prioritized on improving women’s health through the Department of Health Philippines (DOHP) National Safe Motherhood Program in partnership with Local Government Units (LGUs) which envisions Filipino women to have full access to health services for safe pregnancy and delivery [23]. One of the focus in this program was the utilization of the Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (CEMONC) by providing surgical mode of childbirth, blood transfusion services, and other highly specialized obstetric interventions [19] needed to ensure that mothers and their children receive the care they require for survival. It was noted that facility-based delivery has increased between 2006 and 2009 [24], which could potentially explain the increased CS use in 2008. The trend coincided with a decline in maternal deaths from 2006 to 2009 [24].

This study found that women aged 25 years or older had a higher likelihood of CS compared to those under 25, consistent with findings from previous research [10, 15] Additionally, we observed an increase in advanced maternal age ( 35 years) from 22.7% in 1993 to 26.1% in 2017, with women in this group showing a markedly higher likelihood of cesarean delivery compared to younger women. These findings underscore the importance of considering changes in maternal demographics over time [25]. It was found that women with advanced age were at a higher risk of pregnancy complications which increased their likelihood to undergo CS [16, 26]. In the Philippines, women are becoming more career oriented in terms of obtaining education and participating actively in the workforce, which leads to delayed marriage and pregnancy [27]. The increased maternal age during pregnancy tends to have problems in the later trimester that can potentially lead to a CS [28].

35 years) from 22.7% in 1993 to 26.1% in 2017, with women in this group showing a markedly higher likelihood of cesarean delivery compared to younger women. These findings underscore the importance of considering changes in maternal demographics over time [25]. It was found that women with advanced age were at a higher risk of pregnancy complications which increased their likelihood to undergo CS [16, 26]. In the Philippines, women are becoming more career oriented in terms of obtaining education and participating actively in the workforce, which leads to delayed marriage and pregnancy [27]. The increased maternal age during pregnancy tends to have problems in the later trimester that can potentially lead to a CS [28].

Women who begin ANC in their first trimester of pregnancy have a higher frequency to use CS [29], which is consistent with the findings of this study. Early ANC visits provide access to ANC packages that include CS coverage through Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth), a basic health insurance provider in the Philippines. Finally, we found that women who gave birth in private health institutions were more frequently to use CS than those who gave birth in public health institutions, comparable in some studies from other developing countries [10, 14, 15, 30]. In the Philippines, there are more obstetricians/gynecologists working in private hospitals than in public hospitals, and 60% of the health facilities accredited by PhilHealth are private hospitals [31]. The consistently higher CS rates in private health institutions highlight the disparity in CS access between public and private health facilities. Therefore, the PhilHealth insurance benefit for mothers and children, as well as the limited availability of specialized physicians in public health settings, need to be re-evaluated to address this disparity.

In the Philippines, under the Maternal Care Package of basic health insurance, PhilHealth provides financial assistance to ensure access to essential maternal health services. For cesarean deliveries, accredited level 1 to 3 hospitals reimbursed Php 19,000 (~ USD 325), while normal deliveries are covered at Php 6,500 (~ USD 111) in birthing homes, maternity clinics, infirmaries, or dispensaries, and Php 8,000 (~ USD 137) in accredited hospitals. This financial support aims to promote the survival and well-being of both mothers and their children [32]. Furthermore, the Universal Health Care Act (Republic Act No. 11223), signed into law in 2022, would ensure all Filipinos are automatically enrolled in the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP). This legislation mandates 100% PhilHealth coverage, including the Maternal Care Package for cesarean deliveries [33]. This ensures equitable access to CS services for all Filipino women regardless of financial constraints.

The findings of this study suggest that, in line with previous studies, women with higher education and better household wealth status were more likely to use CS [10, 34]. The increased likelihood of CS use among women with higher socioeconomic status may be attributed to their enhanced financial capacity to access top-tier hospitals with more obstetric providers and willingness to accept private health insurance payments [35]. Studies in other countries, including Pakistan [15], Burundi [36], Nepal [10, 14], and Tanzania [17], have also found that women with higher socioeconomic status have a greater tendency to choose CS. These findings suggest that the choice of CS is influenced more by financial capacity than by medical recommendations for a safe delivery procedure [37, 38]. Higher education level and better wealth status make women have more freedom and decision-making power regarding how they should deliver, however, it may not necessarily enhance their awareness on the pros and cons of CS [39].

It can be assumed that women with better socioeconomic status are more likely to receive better ANC services, such as health education and counseling, which may contribute to higher CS rates. However, a study found that women with low socioeconomic status who lack access to antenatal health education also have an increased likelihood of CS delivery [40]. This highlights the importance of ensuring that information about the risks and benefits of CS is effectively conveyed through public health education and counseling. Additionally, it is crucial to emphasize that CS should only be carried out when medically indicated. Lastly, the implementation of CEMONC services in the public health settings must be reviewed to narrow down the gap of obstetric services in both public and private institution. This way, women of lower education and wealth status may receive quality obstetric services in both health settings similar to the quality of obstetric care received by women with higher education and better wealth status. We proposed several solutions to address this issue. First, our suggestion entails the augmentation of public health programs, implementation of accreditation systems, and consistent monitoring to foster improved hospital performance and ensure patient safety [41–43]. Second, training and periodic supervision by a senior physician in every hospital should be implemented to help maintain standards of medical practices [44]. Third, to ensure effective oversight of both CS rates and healthcare service quality, it is advisable to establish routine clinical audits at all levels of healthcare [9, 45, 46]. By implementing medically indicated and high-quality CS procedures, policymakers, physicians, and allied health providers can collaborate to minimize the disparity in access to CS for all women.

To reduce unnecessary CS, the WHO recommends several non-clinical strategies while ensuring high-quality and respectful care. These include educational interventions, such as childbirth preparation workshops, relaxation programs, and psychosocial support for women with anxiety or fear of pain, along with regular monitoring and evaluation. WHO also highlights the importance of evidence-based clinical guidelines, routine audits of cesarean practices, and timely feedback to health professionals. Additionally, requiring a second medical opinion for cesarean decisions is suggested where feasible [47]. Although literature on reducing unnecessary CS deliveries in the Philippines is limited, these guidelines provide a valuable framework for policymakers to develop and implement effective programs tailored to the local context.

Another strategy to reduce CS rates is the application of trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC), which allows women with a prior cesarean delivery, irrespective of the outcome of their previous cesarean [48]. This approach offers women the opportunity to achieve a normal spontaneous delivery after a prior cesarean. In the Philippines, a study by Garcia-Tansengco [49] evaluated the cost-effectiveness of elective repeat cesarean delivery compared to TOLAC in preventing uterine rupture. The findings revealed that successful TOLAC resulting in vaginal birth was the least expensive option, supporting its safety and cost-effectiveness for pregnant women.

This study had several strengths, including being the first to use population-based data in the previous two decades to show the trend of institutional-based CS in the Philippines over time. The study used six survey periods from the nationally representative sample of Filipino population, making its findings highly generalizable. While previous studies only covered one year [13] and had smaller sample sizes [22], this study showed the proportion of institutional-based CS based on nationwide data over the last 25 years, providing valuable evidence to policymakers. However, the study had limitations, including not providing information about the type of CS whether it was emergency or elective, history of CS among the survey participants, or whether the CS performed was medically prescribed, which would have allowed for better picture of the use of CS. Another limitation is that the data were collected through household interviews, limiting the availability of key obstetric and clinical details, such as data on pregnancy complications and health issues during labor or delivery. As highlighted by Cavoretto et al. (2023), maternal characteristics, clinical health issues, and obstetric history are all closely linked to the rising CS rates, emphasizing the importance of these factors in the CS decision-making process. To address these limitations, future research could employ longitudinal cohort studies or hospital-based data collection to capture more detailed obstetric and clinical factors and provide a more comprehensive analysis of trends in CS rates over time. Nonetheless, this study demonstrated a disparity in CS use in public health sectors and differences in use of CS across sociodemographic characteristics.

Conclusion

Overall, CS rate in the Philippines is consistently exceeds the WHO’s recommended maximum threshold. Factors associated with increased CS use included increased maternal age, higher education, belonging to middle or rich household, 1 and 2–3 birth order, and initial ANC visit during the first or later trimester of pregnancy. Addressing these disparities is critical to improve access to high-quality maternal healthcare access and decrease maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity rates in the Philippines.

Acknowledgements

The authors are gratefully acknowledging the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) Program for the access to the dataset for further analysis.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal care

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CEMONC

Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care

- CS

Cesarean section

- DHS

Demographic and Health Survey

- DOHP

Department of Health Philippines

- LGU

Local Government Units

- MMR

Maternal mortality ratio

- PhilHealth

Philippine Health Insurance Corporation

- PNDHS

Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey

- SDG

Sustainable Development Goal

- USAID

United States Agency for International Development

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

EBFD and FWL wrote the main manuscript and CHY, MJRT, and THL contributed to the interpretation of findings and manuscript revision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Chi Mei Medical Center (grant No. 111CM-KMU-09) and the National Science and Technology Council (grant No. MOST 111-2314-B-037-034-MY2).

Data availability

The PNDHS data analyzed in this study can be requested and obtained from the DHS website https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ICF Macro Institutional Review Board in Calverton, Maryland, USA, provided ethical approval for the 1993–2017 surveys. The DHS data are publicly available, and permission to further analyze the data was obtained from the DHS programs after the study proposal was reviewed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Betran AP et al. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health, 2021. 6(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Nagy S, Papp Z. Global approach of the cesarean section rates. J Perinat Med. 2020;49(1):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byamugisha J, Adroma M. Caesarean section in Low-, Middle-and high-income countries. Recent Advances in Cesarean Delivery; 2020.

- 4.Farag Attia MM, Sarhan A-MM, Abdel-Dayem HME-S. Reverse breech extraction Versus Disimpaction of the Head during Cesarean Section for Obstructed Labor. Zagazig Univ Med J. 2020;26(4):566–73. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louis HS. Cesarean Delivery. 2023 September 06 [cited 2024 October 23]; Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/263424-overview

- 6.Kim AM, et al. An ecological study of geographic variation and factors associated with cesarean section rates in South Korea. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbons L, et al. The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. World Health Rep. 2010;30(1):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betran AP, et al. WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG. 2016;123(5):667–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhandari AKC, Dhungel B, Rahman M. Trends and correlates of cesarean section rates over two decades in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herwansyah H, et al. The utilization of maternal health services at primary healthcare setting in Southeast Asian countries: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2022;32:100726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paredes KP. Inequality in the use of maternal and child health services in the Philippines: do pro-poor health policies result in more equitable use of services? Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sepehri A. Institutional setting and wealth gradients in cesarean delivery rates: evidence from six developing countries. Birth. 2018;45(2):148–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acharya K, Paudel YR. Trend and Sociodemographic Correlates of Cesarean Section Utilization in Nepal: evidence from demographic and health surveys 2006–2016. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:p8888267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amjad A, et al. Trends of caesarean section deliveries in Pakistan: secondary data analysis from demographic and health surveys, 1990–2018. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenabi E, et al. Reasons for elective cesarean section on maternal request: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(22):3867–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibre G, et al. Magnitude and trends in socio-economic and geographic inequality in access to birth by cesarean section in Tanzania: evidence from five rounds of Tanzania demographic and health surveys (1996–2015). Arch Public Health. 2020;78:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The DHS, Program. Wealth Index. 2016 [cited 2025 January 4]; Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/topics/wealth-index/index.cfm

- 18.World Health Organization. Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births). 2023 May 11 [cited 2025 January 18]; Available from: https://data.who.int/indicators/i/C071DCB/AC597B1

- 19.Department of Health Philippines. Administrative Order No. 2008-0029: Implementing Health Reforms for Rapid Reduction of Maternal and Neonatal Mortality. 2008 September 9 [cited 2024 October 23]; Available from: https://www.scribd.com/document/325938865/Administrative-Order-No-2008-0029

- 20.World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nisperos GA, et al. The development of Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (BEmONC) and Maternal Health in the Philippines: a historical literature review. Acta Med Philippina. 2022;56(16):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Festin MR, et al. Caesarean section in four South East Asian countries: reasons for, rates, associated care practices and health outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz KCN. Examining the Department of Health’s National Safe Motherhood Program as a policy addressing the increasing trend in the Philippine maternal mortality ratio. in Int Acad Forum. 2016.

- 24.Huntington D, Banzon E, Recidoro ZD. A systems approach to improving maternal health in the Philippines. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(2):104–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavoretto PI, Candiani M, Farina A. Cesarean Delivery Uptake trends Associated with patient features and threshold for Labor anomalies. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e235436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinheiro RL, et al. Advanced maternal age: adverse outcomes of pregnancy, a Meta-analysis. Acta Med Port. 2019;32(3):219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai S-L, Tey N-P. Socio-economic and proximate determinants of fertility in the Philippines. World Appl Sci J. 2014;31(10):1828–36. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeong Y, et al. Effect of maternal age on maternal and perinatal outcomes including cesarean delivery following induction of labor in uncomplicated elderly primigravidae. Med (Baltim). 2021;100(34):e27063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gedefaw G, Waltengus F, Demis A. Does timing of Antenatal Care initiation and the contents of Care have effect on caesarean delivery in Ethiopia? Findings from demographic and Health Survey. J Environ Public Health. 2021;2021:p7756185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahman MM, et al. Determinants of caesarean section in Bangladesh: cross-sectional analysis of Bangladesh Demographic and Health survey 2014 data. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0202879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callahan S et al. Philippines Private Health Sect Assess. 2019. 28.

- 32.Philippine Health Insurance Corporation. Social health insurance coverage and benefits for women about to give birth revision 1. 2015 [cited 2024 January 9]; Available from: https://www.philhealth.gov.ph/circulars/2015/circ025-2015.pdf

- 33.Philippine Health Insurance Corporation. Stats and Charts 2023. 2023 [cited 2024 January 9]; Available from: https://www.philhealth.gov.ph/about_us/statsncharts/SNC2023_02142024.pdf

- 34.Berglundh S, et al. Caesarean section rate in Nigeria between 2013 and 2018 by obstetric risk and socio-economic status. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26(7):775–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spurlock EJ, et al. Integrative Review of Disparities in Mode of Birth and related complications among Mexican American women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2022;67(1):95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yaya S, et al. Inequalities in caesarean section in Burundi: evidence from the Burundi demographic and health surveys (2010–2016). BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boatin AA, et al. Within country inequalities in caesarean section rates: observational study of 72 low and middle income countries. BMJ. 2018;360:k55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ronsmans C, Holtz S, Stanton C. Socioeconomic differentials in caesarean rates in developing countries: a retrospective analysis. Lancet. 2006;368(9546):1516–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akhter S, Schech S. Choosing caesareans? The perceptions and experiences of childbirth among mothers from higher socio-economic households in Dhaka. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39(11):1177–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milcent C, Zbiri S. Prenatal care and socioeconomic status: effect on cesarean delivery. Health Econ Rev. 2018;8(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al Shawan D. The effectiveness of the Joint Commission International Accreditation in improving quality at King Fahd University Hospital, Saudi Arabia: a mixed methods Approach. J Healthc Leadersh. 2021;13:47–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devkaran S, et al. Impact of repeated hospital accreditation surveys on quality and reliability, an 8-year interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e024514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin HC, Xirasagar S. Institutional factors in cesarean delivery rates: policy and research implications. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(1):128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. Setting performance standards and expectations for patient safety. To err is human: building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press (US); 2000. [PubMed]

- 45.Chen I, et al. Non-clinical interventions for reducing unnecessary caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9(9):pCd005528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohammadi S, Källestål C, Essén B. Clinical audits: a practical strategy for reducing cesarean section rates in a general hospital in Tehran, Iran. J Reprod Med. 2012;57(1–2):43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. Caesarean section rates continue to rise, amid growing inequalities in access. 2021 [cited 2024 January 4]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/16-06-2021-caesarean-section-rates-continue-to-rise-amid-growing-inequalities-in-access

- 48.ACOG Practice Bulletin 205. ACOG Practice Bulletin 205: Vaginal Birth after Cesarean Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(2):e110–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia-Tansengco ML. Effective repeat cesarean section versus trial of labor after a previous cesarean section: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Philippine J Obstet Gynecol, 2000. 25(1).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The PNDHS data analyzed in this study can be requested and obtained from the DHS website https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.