Abstract

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are hazardous air pollutants with well-documented carcinogenic, mutagenic, and toxic effects. This study investigates the chemical composition and sources of PAHs in Kraków, a city characterized by diverse air quality challenges. PM10 and PM2.5 samples were collected during the winter seasons of 2014 and 2015, enabling a detailed assessment of PAH concentrations and their atmospheric transformations. The results indicate that PAH levels frequently exceeded European Union and World Health Organization limits, with benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) reaching peak concentrations of 38.8 ng m−3 in PM10 and 30.2 ng m−3 in PM2.5, highlighting significant health risks. To determine PAH sources, a chemical-based framework integrating diagnostic ratios, receptor modeling, and backward trajectory analysis was applied. The findings reveal that coal and biomass combustion were dominant PAH contributors, with additional influences from vehicular emissions and industrial activities. The BaP/(BaP + BeP) ratio suggested that PAHs in PM2.5 underwent more atmospheric aging than those in PM10, indicating that finer particles play a crucial role in PAH transport and transformation. Furthermore, correlations with inorganic and organic PM constituents, such as chloride and levoglucosan, underscored the mixed influence of fossil fuel and biomass burning. The study also evaluated the toxicological implications of PAHs, demonstrating that mutagenic activity exceeded toxicity levels, and finer particles posed a greater carcinogenic risk. While the exposure index suggested that short-term exposure remained within acceptable limits, long-term effects require further assessment. Given the complex interplay of emission sources and atmospheric processes, continuous monitoring and targeted mitigation strategies are essential for improving urban air quality.

Keywords: Atmosphere pollution, Atmosphere chemistry, Particulate matter, Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, Organic PM components, Inorganic PM components

Subject terms: Atmospheric chemistry, Environmental impact

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are a group of organic compounds composed of multiple aromatic rings, primarily generated during the incomplete combustion of organic matter such as fossil fuels, biomass, and waste. PAHs are of significant environmental concern due to their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and well-documented toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic properties. They are also considered critical indicators of air quality in urban areas, as they are often associated with particulate matter (PM) and can cause adverse health effects through inhalation exposure1.

The challenges posed by PAHs are particularly acute in urban environments, where diverse emission sources coexist and interact. Major sources of PAHs in cities include vehicular emissions, residential heating using biomass or coal, industrial activities, and transboundary pollution. The complexity of these emission sources, coupled with atmospheric processes such as photochemical reactions and deposition, makes it difficult to identify and quantify the contribution of individual sources. This necessitates chemical-based approaches to achieve accurate source apportionment2. Out of many cities that face the problem elevated pollution levels, Kraków is one unique due to many factors that influence the air quality within the city. Despite the emission of pollution from industrial and automotive sources, during the heating season it also faces a problem of outworn residential heating systems3,4 and long-range transport of pollutants. Furthermore, the city is located in a bad-ventilated basin, which often causes pollution entrapment due to the effect of air mass temperature inversion5.

Diagnostic ratios (DRs), derived from the relative abundances of PAH isomers, have emerged as a widely used tool in environmental studies to distinguish between PAH sources. For instance, anthracene/(anthracene + phenanthrene), fluoranthene/(fluoranthene + pyrene, and benzo-a-pyrene/(benzo-a-pyrene + benzo-e-pyrene) are commonly used ratios to identify sources such as petroleum combustion, biomass burning, and coal combustion. These ratios also provide insights into the aging and transformation of PAHs in the atmosphere. Specifically, BaP/(BaP + BeP) is sensitive to atmospheric degradation, as benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) degrades faster than benzo[e]pyrene (BeP), making it a key indicator of photochemical aging6,7.

In addition to diagnostic ratios, chemical-based receptor models, such as Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF), have been widely applied to quantify the contribution of various sources to PAH concentrations. These models utilize chemical profiles of pollutants to identify and apportion sources, providing a more holistic understanding of emission dynamics8. In particular, the integration of diagnostic ratios with receptor modeling enhances the robustness of source apportionment studies by combining empirical data with statistical methods.

Studies consistently reveal significant differences in PAH concentrations between urban and rural settings, pointing out to the coal combustion and transportation as main sources of these contaminants emission with different patterns depending on the examined area9. These findings were confirmed in other studies where multivariate statistical techniques supported by diagnostic ratios or air masses backward trajectories analysis were applied to provide detailed characteristics of sources and processes related to the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, i.e. in Poznań (Central Poland)10, over the coastal region in Poland11,12 or in Upper Silesia13. The detailed studies on specific source related particulate matter enabled to determine the characteristic patterns, like i.e. for derived by traffic PAHs14 or for PAHs emitted during combustion of different materials15 and fuels3.

The study city presents a unique case of diverse air quality challenges. Its pollution profile is shaped by a mix of local emissions, such as residential heating and vehicular traffic, and regional pollution, including long-range atmospheric transport. This mixed-emission environment not only complicates source identification but also amplifies the need for chemical-based methods to disentangle local and regional contributions. The seasonal variations in PAH concentrations, driven by meteorological factors and heating practices during winter, add another layer of complexity to understanding PAH behavior in this urban setting.

The results presented in this paper addresses these challenges by employing a comprehensive chemical-based framework to investigate the sources and atmospheric transformations of PAHs in the city. By integrating diagnostic ratios, chemical modeling, and atmospheric data, this work aims to provide a detailed characterization of PAH sources, quantify their relative contributions, and evaluate the impact of photochemical aging on PAH profiles. Furthermore, the study investigates the relationship between PAH concentrations and particulate matter fractions (PM10 and PM2.5), offering insights into the partitioning behavior of PAHs and their interaction with atmospheric aerosols. This scientific investigation contributes to the growing body of literature on PAH source apportionment in several innovative ways:

chemical-based framework through the integration of diagnostic ratios and receptor modeling what provided a multi-faceted approach to source identification, combining the strengths of empirical and statistical methods,

assessment of diagnostic ratios which allowed for the evaluation of atmospheric transformation processes, a relatively underexplored aspect in urban PAH studies,

case study in a complex urban environment representing a rare example of a mixed-pollution scenario, combining local and regional influences. The findings have broad implications for other cities facing similar air quality challenges,

methodological contribution by the integration of diagnostic ratios with receptor models bridging the gap between theoretical approaches and practical applications, offering a replicable framework for future studies.

The outcomes of the presented work are expected to enhance the understanding of PAH sources and transformations in urban environments, providing valuable insights for policymakers and environmental managers tasked with designing effective air quality management strategies.In this exploration we aimed to provide a detailed characterization of the aerosol chemistry in the Kraków metropolitan area based on particulate matter samples collected during the winter. The concentrations of various particulate matter constituents, such as humic-like substances, polysaccharides, organic and elemental carbon, as well as inorganic ions, were analysed. Conducting these analyses enabled statistical data mining, which together with air masses backward trajectory and diagnostic ratios analysis allowed to identify the origin of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the city in that time.

Materials and methods

Site description and sample collection

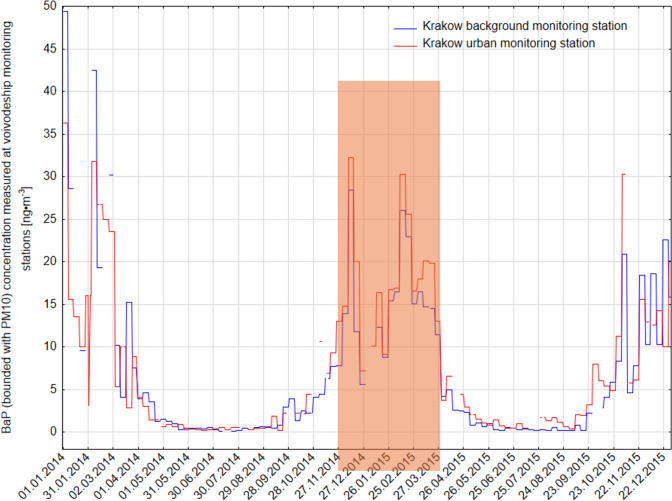

The PM10 and PM2.5 fractions were alternately collected during two distinct measurement campaigns: November–December 2014 and February–March 2015. In total, 11 samples were collected for each fraction. To maintain consistency and ensure high-quality data, real-time monitoring of meteorological conditions was performed during the sampling periods. This allowed for dynamic adjustments in flow rate, ensuring a constant air velocity at the inlet, thereby minimizing potential variations due to environmental fluctuations. As presented in Table 1, the selected measurement periods were chosen deliberately to coincide with the seasons of the highest atmospheric concentrations of benzo[a]pyrene (BaP), as recorded by Krakow’s urban and background air quality monitoring stations (Fig. 1). The heating season, characterized by intensive coal and biomass combustion, is well-documented as a time of significantly elevated PAH emissions, particularly BaP, which is a key indicator of air pollution from residential heating sources.

Table 1.

The temporal context and meteorological conditions of PM10 and PM2.5 samples gathering in wintertime in Kraków. Source: AGH Weather Service available at www.meteo.ftj.agh.edu.pl).

| PM10 sampling period | PM10 sampling duration (h) | PM2.5 sampling period | PM2.5 sampling duration (h) | Wind velocity (m s−1)* | Temperature (°C)* | Humidity (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nov 14/15 2014 | 36 | Nov 15/16 2014 | 36 | 1.6 | 8.8 | 79.0 |

| Nov 19/20 2014 | 24 | Nov 20/21 2014 | 24 | 1.9 | 4.9 | 85.7 |

| Nov 24/25 2014 | 36 | Nov 25/26 2014 | 36 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 72.8 |

| Dec 01/02 2014 | 36 | Dec 02/03 2014 | 36 | 3.7 | − 2.5 | 63.4 |

| Dec 08/09 2014 | 36 | Dec 09/10 2014 | 36 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 79.4 |

| Dec 15/16 2014 | 24 | Dec 16/17 2014 | 24 | 0.7 | 5.7 | 75.7 |

| Feb 02/03 2015 | 48 | Feb 03/04 2015 | 48 | 1.7 | − 1.3 | 67.0 |

| Feb 12/13 2015 | 36 | Feb 13/14 2015 | 36 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 66.2 |

| Feb 19/20 2015 | 48 | Feb 20/21 2015 | 48 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 63.2 |

| Feb 26/27 2015 | 48 | Feb 27/28 2015 | 48 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 83.2 |

| Mar 05/06 2015 | 48 | Mar 06/07 2015 | 48 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 65.0 |

*The meteorological parameters are presented as a average for the entire sampling episode PM10 + PM2.5

Fig. 1.

The concentration of benzo-a-pyrene measured at Krakow background and urban monitoring stations in 2014 and 2015.

This seasonal trend is clearly observed in Fig. 1, where BaP concentrations at the urban monitoring station reached peak levels, exceeding 32 ng m−3 in late November 2014, while remaining significantly elevated throughout the winter months. In contrast, during the non-heating season, BaP concentrations dropped below 5 ng m−3, highlighting the dominant impact of residential heating on urban air quality. Given these seasonal variations, conducting measurements exclusively during the cold season was essential for capturing the peak emission periods and gaining insights into the contribution of combustion sources to atmospheric PAH loads. The timing of the campaign thus ensures a representative assessment of the impact of solid fuel combustion, which is the primary driver of BaP pollution in Krakow during winter.

Particulate matter samples were collected of quartz fibre filters (Pallflex, 47 mm of a filter diameter). Prior to sampling, all quartz fibre filters were preheated for 6 h at 550 ± 8 °C and then maintained at a temperature of 20 ± 1 °C and relative humidity of 50 ± 5% for at least 24 h. Once the PM samples are collected, all filters were conditioned for 48 h, weighted in microbalance (A&D HM-202-EC, United States) up to an accuracy of 0.01 mg and then stored in a freezer at − 20 °C until analysis. A low-volume sampler Twin Dust (Model PF 11045-02, Zambelli Inc., Italy), equipped with two heads (Digitel) PM2.5 and PM10 in compliance with European standards EN 1234116 was placed on the roof of a three-storey building (in approximately 15 m height). The sampler operated at a flow rate equal to 2.3 m3 h−1 in the cyclical system of sampling (PM10/PM2.5) in ambient conditions in 24-, 36- or 48-h intervals (Table 1). The selection of different sampling durations was primarily dictated by the need to accumulate a sufficient mass of particulate matter on each filter, ensuring adequate material for multiple subsequent chemical analyses. The PM mass was determined through gravimetric measurements by calculating the difference between the average masses of three consecutive weights after and before the PM sampling on each filter.

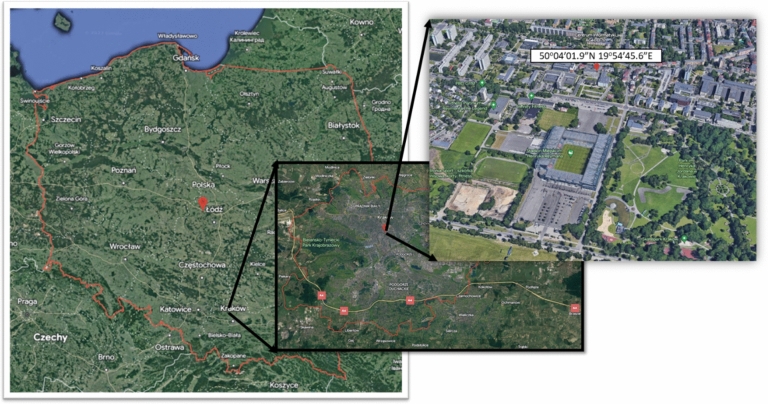

The sampling site was located in the centre of Kraków (50° 04′ 01.9″ N 19° 54′ 45.6″ E), the second largest city of Poland (near 1 million inhabitants). Kraków, located in the South of Poland, is an agglomeration with a high intensity of transport, a power plant and some industrial sites. In the heating season, low-stack emission (residential heating) and on-road pollution are considered as the most serious emitters of particles to the atmosphere in the area4. The sampling site is a built-up area and represents a typical urban location characterised by high traffic intensity on the one hand, and a settlement area with a big park, on the other hand (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Location of the sampling site. Source: Google Earth).

Chemicals

The EPA 610 PAH mixture, which is a certified reference material, was used in this study and was supplied by Sigma Aldrich. The molecular formulae, physical and chemical properties of the compounds are summarised in Table S1. Two stored in hexane deuterium-labelled PAH solutions, benzo(a)pyrene-d12 (d12-BaP) and perylene-d12 (d12-Per), serving as internal and surrogate standards respectively, were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich. To validate the analytical methods, the standard reference materials (SMR 1649a, Urban Dust) were purchased (NIST). Dichloromethane and cyclohexane (analytical grade, Sigma-Aldrich) were used as extracting agents paired with ultrasonic attrition.

Determination of the content of organic and inorganic components of PM10 and PM2.5

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

The concentration of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons was determined using a gas chromatograph equipped with a mass spectrometer (GC/MS). The concentrations of a 18 PAHs were determined, including 16 PAHs defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as priority PAHs17. The retention times, characteristic ions and instrumental quantification limits for all analytes are shown in Table 2. The applied analytical method was similar to these ones described in previous works of authors18–20.

Table 2.

Chromatographic and mass spectrometric characterization of target compounds.

| Compounds | Abbreviations | Retention time (min) | Characteristic ions (m/z) | LOD (ng m−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naphthalene | Naph | 8.46 | 128, 115 | 0.14 |

| Acenaphthylene | Aceny | 13.00 | 152, 126 | 0.22 |

| Acenaphthene | Acene | 13.26 | 154, 126 | 0.18 |

| Flourene | Flu | 14.49 | 166, 139 | 0.19 |

| Phenanthrene | Phe | 17.14 | 178, 152 | 3.71 |

| Anthracene | Anth | 17.22 | 178, 152 | 0.60 |

| Flouranthene | Fla | 20.16 | 202, 174 | 0.15 |

| Pyrene | Pyr | 20.49 | 202, 174 | 2.69 |

| Benz(a)anthracene | BaA | 23.55 | 228, 200 | 1.20 |

| Chrysene | Chr | 24.00 | 228, 202 | 0.77 |

| Benzo(e)pyrene | BeP | 25.05 | 252, 125 | 1.25 |

| Benzo(b)flouranthene | BbF | 26.30 | 252, 224 | 0.44 |

| Benzo(k)fluoranthene | BkF | 26.35 | 252, 224 | 0.44 |

| Benzo(a)pyrene | BaP | 27.18 | 252, 225 | 1.22 |

| Perylene | Per | 28.06 | 252, 126 | 0.34 |

| Benzo(ghi)perylene | BghiP | 30.06 | 276, 248 | 7.20 |

| Dibenz(a,h)anthracene | DBA | 30.17 | 278, 248 | 1.94 |

| Indeno(1,2,3cd)pyrene | IcdP | 30.55 | 276, 248 | 0.82 |

Two small discs (10 mm Ø) were cut out of each filter and were then spiked with 50 µl (25 ng µl−1) of d12-Per in Petri dishes. Deuterated perylene served as a surrogate standard to ensure that the extraction and sample preparation process is performing correctly. After 20 min, the discs were placed in 20 ml vials and ultrasonically extracted twice with 5 ml of dichloromethane/cyclohexane (3:2, v/v) mixture for 30 min. The combined extracts were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 30 min and then spiked with 50 µl (10 ng µl−1) of d12-BaP. Deuterated BaP served as an internal standard to ensure that the final quantification in GC analysis is precise and not affected by instrumental fluctuations. The volume of the extract was reduced to 500 µl using a gentle stream of nitrogen in the multiport condenser at 35 °C for about 35 min. The concentrate was successively transferred into 2 ml chromatographic vials equipped with 300 µl inserts for analysis by means of GC/MS.

The chromatographic separation was performed by HP 6890 GC system equipped with a model 7683 autosampler. A DB5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.25 μm film thickness) fitted with uncoated deactivated fused silica was used to separate target analytes with 1 ml min−1 helium (6.0 quality) as a carrier gas. The oven temperature program was as follows: isothermal hold at 70 °C for 1 min, temperature ramp of 10 °C min−1 to 270 °C and then 15 °C min−1 to 300 °C, isothermal hold at 300 °C for 5 min. The injection was performed with a split/splitless injector at a temperature of 300 °C. Splitless time was 2 min. The injection volume was 2 μl. The total analysis time for one GC run was approximately 25 min. The GC/MS interface temperature and ion source were kept at 280 °C and 250 °C, respectively.

Detection was performed with a quadrupole mass spectrometer (HP MSD5973) operated in the positive electron impact mode at 70 eV. The mass spectra were obtained in total ion current (TIC) mode over a mass range (m/z) of 50–600 amu and in the single ion monitoring (SIM) mode. Identification of the target compounds in the analysed samples was based on the retention time, the quantitative ion, the confirmation ion and the quantitative/confirmation ion ratio.

The quality assurance and quality control of PAHs determination

Ensuring the accuracy and reliability of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons determination in environmental samples requires a robust quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) framework. This section outlines the key QA/QC procedures implemented in this study, including recoveries, detection limits, and the quantification method used for PAHs analysis.

D12-perylene was added as a surrogate standard to each sample before extraction to assess method efficiency and potential losses during sample processing. Surrogate recoveries were evaluated by comparing the measured concentrations to the known spiked amounts. Acceptable recovery limits were set at 70–120%. Samples with surrogate recoveries outside this range were flagged, and reanalysis was performed if necessary.

For accurate quantification, deuterated benzo-a-pyrene (d12-BaP) was added to all samples, calibration standards, and quality control samples immediately before instrumental analysis. The internal standard was used to correct for instrumental variability and ensure precision in PAH quantification. A five-point calibration curve was constructed using certified PAH standard solutions, with correlation coefficients (R2) exceeding 0.995. The response factor for each PAH was calculated and used for final concentration determination.

To ensure the actual instrument performance and the sensitivity of the method for detecting PAHs at at environmentally relevant concentrations the limits of detection were calculated. LOD was defined as three times the standard deviation (3σ) of blank samples. These values for each analyte are summarized in Table 2.

Field and laboratory blanks were analyzed alongside the samples to assess potential contamination during sample collection, extraction, and analysis. No significant PAH contamination was detected in the blanks, confirming the integrity of the analytical process.

Certified reference materials were used to validate the method’s accuracy. The PAH determination method was validated using the NIST 1649a Urban Dust Standard Reference Material (SRM). The measured BaP concentrations (as a representative of organic pollutants from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons group) in the NIST 1649a standard were within ± 10% of the certified values, confirming the method’s accuracy and applicability for real-world environmental samples. This validation step ensured that the analytical approach provided reliable and reproducible results in line with internationally recognized standards.

Analytes were identified positively in a case identical retention times and mass ratios similar to the mass ratios retrieved through calibration (allowing a variation of ± 15%). Quantitative analysis was based on the peak areas of the quantitative ions recorded in SIM mode according to Eq. (1):

|

1 |

where APAH—peak area of the specific PAH in the sample; AIS—peak area of the internal standard; CIS—Concentration of the internal standard in the sample; Vfinal—final volume of the extract; Rsurr—surrogate recovery factor; Vair—sample volume of air; Rinstr—instrumental response factor.

Determination of the content of levoglucosan on PM10 and PM2.5

In order to monitor biomass-related combustion, the concentration of levoglucosan was measured using ion exchange chromatography combined with pulsed amperometry detection (HPAC-PAD) equipped with a CarboPac MA1 column and a NaOH gradient (480–650 mM). The applied analytical method was previously described by Iinuma et al.21. For quantification external standards were used at 5 different concentrations. The circular punch with a diameter of 10 mm was cut out from the quartz filter containing the PM sample and placed in a test tube. 3 ml of carbon-free deionized water (Mili-Q 185) was added and the sample was extracted for 20 min in an ultrasonic bath. After the extraction, the sample was centrifuged for 20 min at 1500 rpm. After centrifuging the extracts were passed through filters injectors. Finished sample was placed in the HPAC-PAD instrument for the analysis. The limit of detection was equal to 0.006 μg m−3.

Determination of the content of humic-like substances in PM10 and PM2.5

The procedure started with punching out a set amount of smaller circles (3 or more) out of the filter and placing it into a 12 ml vial. The sample material was then extracted from the filter with deionized water (Mili-Q 185) and 0.1 M solution of sodium hydroxide. The extraction process consisted of two steps: triple extraction of water-soluble species by the addition of 3 ml of Mili-Q water with ultrasonic mixing for 20 min. The collective sample was then acidified with 0.9 ml of diluted HNO3 solution (pH = 2). The second step consisted of triple extraction of remaining on filter alkali-soluble species with 3 ml 0.1 M NaOH solution (pH = 13) and subsequent ultrasonic bath mixing for 20 min each. The resulting sample was then acidified with 0.9 ml of diluted HNO3 solution (pH = 0). Extracted high-molecular-weight organics including HULIS were then separated on solid phase extraction (SPE) system (Biotage) under vacuum pressure resulting in SPE column speed of 20 ml min−1. The SPE cartridges (Isolute C18, IST 500-0020) were cleaned with 10 ml deionized of water and 3 ml of methanol each beforehand. The fraction absorbed on the column was eluted with 0.2 ml of methanol (liquid of lower polarity than water). The probe with methanol-extracted solution was then filled with up to 2 ml with a mixture of diluted sodium hydroxide and nitric acid with a pH of 2.5.

Both alkali-soluble and water-soluble HULIS samples were quantified with a measurement device developed for this purpose. The method was then described by Limbeck et al.22. The device utilised a switchable flow of nitric acid and ammonia in order to separate HULIS species from other organic constituents on a strong ion exchanger (Isolute SAX, IST 500-0020) and then release it in order to quantify its concentration with the use of Total Organic Carbon Analyser (GO TOC 100, Groger & Obst). The relative standard deviation of the measurement was 5%. The limit of detection for HULIS determination was equal to 3.26 µg.

Determination of the content of the carbonaceous compounds in PM10 and PM2.5

The content of organic carbon (OC) and elemental carbon (EC) was determined with thermal-optical analysis (OC/EC Analyzer, Sunset Laboratory Inc.). Eusaar 2 thermal analysis protocol was applied. Circular aliquots with 10 mm diameter were cut from the quartz filters and were analysed directly. Content of carbon compounds was calculated on the basis of the instrument internal calibration using a mixture of helium and methane (Air Liquide, Austria) as calibration gas and via regular analyses of a sucrose solution. The detection limit for total carbon, organic and elemental was 0.32 μg m−3, 0.32 μg m−3, 0.01 μg m−3, respectively. Reproducibility was controlled by the carbon content of the total reference material (PM10 particles collected on Quartz filter). The relative standard deviation was 5%. The applied analytical method was previously described by Jankowski et al.23 and Szramowiat et al.24.

Determination of the content of the inorganic ions in PM10 and PM2.5

The analytical protocol applied for the determination of inorganic ions was previously described by Szramowiat-Sala25 and Pacura et al.26. An isocratic ion chromatography was used to determine the concentration of the following inorganic cations and anions: Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, NH4+, NO3−, NO2−, Cl−, SO42−. For the purpose of extraction of anions, the sample aliquot punch (ø 10 mm) was cut and placed in a plastic tube to which 2 ml of deionised water (Milli-Qplus proteome 185, Millipore, 18.2 MΩ) were added. The tube was then placed in the ultrasonic bath for 20 min. Cations were extracted with the addition of 3 ml of 12 mM metasulfonic acid (MSA).

To determine the content of inorganic cations and anions ion chromatograph was used (DX-3000, Thermo Scientific) equipped with an ion exchange column and conductivity detection. For anions, Ion Pac AS17A with 1.8 mM Na2CO3 + 1.7 mM NaHCO3 mobile phase column was used, while Ion Pac CS12A with 48 mM MSA mobile phase column was used for cations determination.

Prior to the analysis, the plot calibration with external stock solutions of Merck standards was prepared. The limit of detection methods was equal to 0.1 μg m−3 for Na+ and Cl−, and 0.01 μg m−3 for other ions.

Data mining methods

Determination of statistical data was carried out using Statistica v. 13.3 (TIBCO Software) software. Spearman’s rang correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between the content of the individual components of the particulate matter. A test of the t-distribution was used to assess statistically significant differences in concentrations of particulate matter between fractions of the dust particles. Statistical procedures were carried out on a 95% confidence level. The Lagrangian approach based HYSPLIT model27 was used to determine the backward trajectories of air masses and establish source–receptor relationships with PAHs occurrence in the atmosphere.

Results and discussion

This section presents the findings from our investigation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in particulate matter during winter in Kraków, Poland. The results provide an insight into the concentration levels, composition, and potential sources of PAHs in the ambient air, with a focus on variations between different particulate matter fractions (PM10 and PM2.5). This comprehensive analysis allows for a deeper understanding of the factors affecting PAH levels in the urban atmosphere, contributing to the broader field of aerosol chemistry and air quality management.

PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations during the sampling campaign

In exploring the chemistry of aerosols, the study notably focused on the particulate matter concentrations within Kraków’s atmosphere. To further understand the dynamics of airborne particulates, an examination of PM10 and PM2.5 levels was conducted throughout the sampling campaign. During the sampling period, PM10 concentrations exhibited a significant variability, ranging from 32.4 to 134.7 µg m−3, with an average concentration of 77.8 µg m−3. Concurrently, PM2.5 concentrations ranged from 18.2 to 101.7 µg m−3, with an average concentration of 62.0 µg m−3. Figure 3 presents the variations in PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations measured during the sampling campaign. To validate the reliability of the sampling procedure, the results obtained in this study are compared with data from two air quality monitoring stations in Kraków, representing both urban background and urban environments. The monitoring station data were averaged for time periods corresponding to the study’s sampling episodes, ensuring comparability.

Fig. 3.

PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations measured during the study sampling campaign in the opposite to the PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations measured at two monitoring sites in Kraków (data bank available at https://powietrze.gios.gov.pl/, access: August 13th 2024).

The data demonstrate that PM concentrations measured in this study generally followed the temporal variation trends observed at both monitoring stations, confirming the representativeness of the collected samples. However, some deviations were noted, particularly for PM10, where values recorded in this study were occasionally higher or lower than those reported by the monitoring stations. The most noticeable discrepancy occurred on February 2/3, 2015, when PM10 concentrations significantly differed from both urban and background monitoring station values. A similar pattern was observed for PM2.5, where our measurements were generally consistent with the monitoring station trends, except for February 3/4, 2015, when the recorded PM2.5 concentration was substantially lower than the station measurements.

These variations can be attributed to several factors, including differences in measurement locations and local emission sources during the sampling period. The monitoring stations are positioned at fixed locations that may be more influenced by traffic emissions, whereas the study’s sampling sites may have been subject to localized variations in emissions and atmospheric dispersion processes. Additionally, variations in wind patterns, boundary layer height, and pollutant dispersion mechanisms can contribute to discrepancies between point measurements and station averages.

The highest concentration of PM10 was recorded on December 15/16, 2014. This peak was likely associated with the prevailing meteorological conditions that favored the accumulation of particulate matter. As shown in Table 1, during this period, wind velocity was at its lowest level, which, when combined with low temperatures and low relative humidity, created conditions conducive to PM accumulation in the atmosphere. The lack of strong wind flow likely limited the dispersion of pollutants, leading to an increase in particulate concentrations. For PM2.5, the highest concentration was observed in early February 2015, coinciding with a period of decreasing relative humidity. This suggests that atmospheric dry conditions may have influenced PM2.5 levels, potentially enhancing the suspension of fine particles in the air. Additionally, this period aligns with increased domestic heating activities, a dominant source of PM2.5 emissions during winter in Kraków. The lower humidity may have also reduced particle coagulation and wet deposition processes, leading to sustained high concentrations in the air28.

Atmospheric concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in PM10 and PM2.5

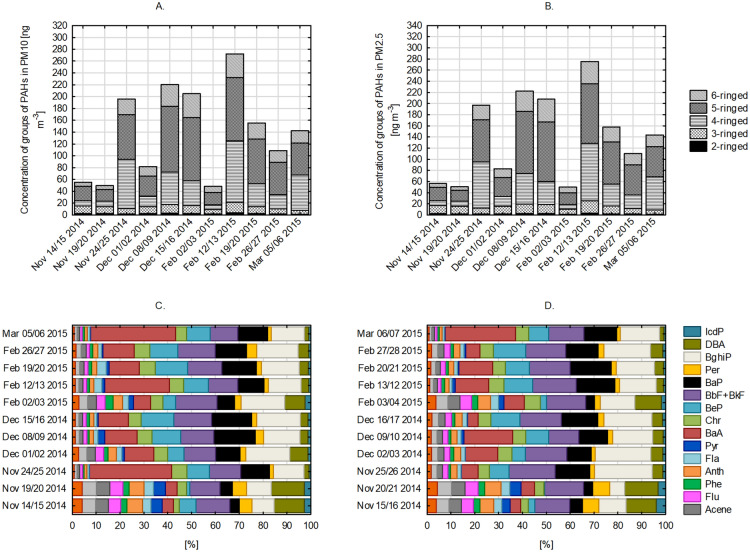

The research resulted in the evaluation of 18 different PAHs substances for 11 sampling short episodes from November 14th, 2014 to March 07th, 2015. Figure 4 summarizes the results of the concentration of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with ambient PM10 (Fig. 4A and C) and PM2.5 (Fig. 4B and D). The concentrations of benzo(b)fluoranthene and benzo(k)fluoranthene were presented jointly due to their inseparability during the chromatographic measurement.

Fig. 4.

Concentration of groups of PAHs in PM10 (A) and PM2.5 (B) and PAHs profiles in ambient PM10 (C) and PM2.5 (D)

The sampling period revealed PAHs patterns with different ring structures. Specifically, 4-ringed PAHs (Fla, Pyr, BaA, and Chr), 5-ringed PAHs (BeP, BbF + BkF, BaP, and Per), and 6-ringed PAHs (BghiP and IcdP) were the primary constituents throughout the study. This trend was consistent for both PM10 and PM2.5 fractions. In fact, these three groups of PAHs collectively accounted for a substantial portion, constituting 85.5% of the total PAHs in PM10 and 83.6% in PM2.5. The authors are aware of the challenges associated with the quantitative analysis of 2- and 3-ringed PAHs. These compounds are characterized by higher volatility and susceptibility to degradation during sampling and analytical procedures, potentially leading to underestimation of their concentrations. For this reason, the concentrations of 2- and 3-ringed PAHs may be slightly higher than it was reported in the paper. However, we may assume that this underestimation do not influence the conclusions of the research presented here.

During the initial days of sampling in November, concentrations of these 4-, 5-, and 6-ringed PAHs remained relatively low, ranging from 0.7 ng m−3 (BeP) to 8.0 ng m−3 (BbF + BkF) in association with PM10 and from 0.1 ng m−3 (BeP) to 6.4 ng m−3 (BbF + BkF) in association with PM2.5 (Table S2). However, as the concentrations of both PM10 and PM2.5 increased on November 24/25, 2014, the total PAH concentrations followed suit.

Notable episodes of significantly elevated concentrations of PM10-bound PAHs occurred on December 08/09, 2014, and December 15/16, 2014, with the sum of PAHs reaching 222.2 ng m−3 and 207.8 ng m−3, respectively. A similar pattern emerged in February 2015, with elevated concentrations of PAHs, particularly on February 12/13, 2015. During this period, concentrations ranged from 2.4 ng m−3 (IcdP) to 74.8 ng m−3 (BaA), resulting in a summarized PAHs value of 275.6 ng m−3 (Table S2). For PM2.5-bound PAHs, episodes of elevated concentrations were observed on December 09/10, 2014, February 03/04, 2015, and February 20/21, 2015, with average values of 145.7 ng m−3, 187.1 ng m−3, and 132.3 ng m−3, respectively (Table S3). The results obtained within this study are comparable with other works. For instance, Rogula-Kozłowska et al.29 examined the concentrations of PAHs in three different locations in Katowice city (Silesian Voivodeship, Poland). The sum of PAHs related with PM2.5 was equal to 107.26 and 196.80 ng m−3 at urban background and urban site of Katowice city.

Among the various PAHs examined, benzo(a)pyrene (BaP) stood out as one of the most concentrated PAHs. The consistent ratio of BaP to total PAHs, both for PM10 (0.11 ± 0.03) and PM2.5 (0.11 ± 0.04), underscores BaP’s effectiveness as a reliable reference substance for assessing overall PAH concentrations30. It exhibited an average concentration of 18.2 ng m−3 when associated with PM10 and 12.6 ng m−3 when associated with PM2.5 (Tables S2 and S3). This values are similar or slightly lower to these ones obtained by Kaleta and Kozielska31. They measured PM-bound BaP concentration in several cities in Silesia Voivodeship in Poland. In the 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021 heating seasons in Rybnik city, the concentrations were 23.5, 27.7, 15.9 and 15.7 ng m−3.

The prevalence of 4-, 5-, and 6-ringed PAHs can be a suggestion of the influence of specific sources and contributing factors during the sampling period. During periods with the lowest PM/PAHs concentrations (specifically on Nov 14/15, 2014, Nov 19/20, 2014, and Feb 02/03), a noticeable shift in the PAHs profile was observed. This shift was observed in both fractions PM10 and PM2.5 (Fig. 4C and D). During these days, the proportion of lighter PAHs (2- and 3-ringed PAHs) increased to approximately 20–30% of total mass concentration of PAHs. Moreover, the share of PM2.5-bound PAHs in PM10-bound PAHs differed even in episodes of elevated total concentrations. On Nov 24/25, 2014 PAHs associated with smaller PM fraction contributed in 42.5% in PM10-bound PAHs mass, whereas on Feb 12/13, 2015—in 83.9%. This observation can be a hint for the origin of PAHs in the atmosphere. This will be discussed in 3.3.

Comparing these results with our data, we observe similar patterns, where PAHs with a higher number of rings dominate in both particulate matter fractions, indicating a significant influence of fossil fuel combustion and traffic emissions. In a study conducted in Nanjing32, PAHs associated with PM10 and PM2.5 were analyzed in different functional areas of the city. It was found that PAHs with a higher number of rings (5- and 6-ring compounds) dominated in both particulate matter fractions, suggesting a significant contribution from vehicle emissions and coal combustion. In a comparative study conducted in various cities in China33, PAHs associated with PM2.5 were analyzed to identify major emission sources and assess health risks. It was found that the dominant sources were coal combustion, industrial emissions, and traffic, with higher PAH concentrations observed during winter, which was attributed to the increased use of fossil fuels for heating.

The study of potential origin of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

Examination of correlations to other PM components

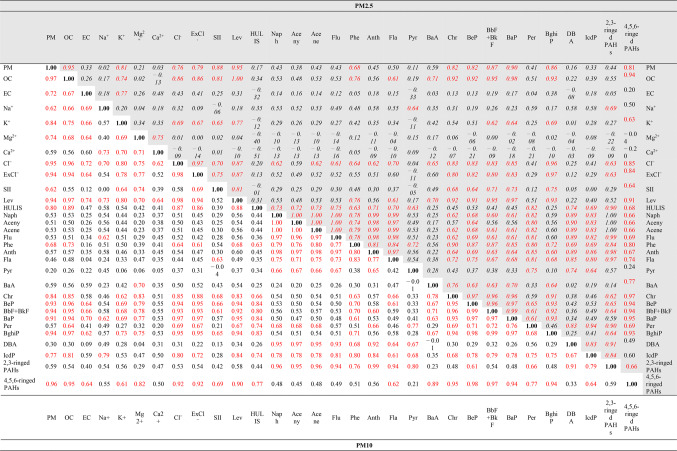

The examination of statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05), encompassing both positive and negative associations, has unveiled numerous interdependencies among PAHs within both the PM2.5 and PM10 fractions. When considering the total PAH content, we identified a total of 10 statistically significant correlations (with R2 values equal to or greater than 0.6) for PM10 and 5 for PM2.5 (Table 3). The most pronounced correlation was observed between organic carbon and total PAHs (0.89 for PM10 and 0.95 for PM2.5). This indicates a direct link between variations in PAH concentrations during the winter and factors responsible for organic carbon production, such as the combustion of fossil fuels. Interestingly, a similar relationship was not identified for elemental carbon, mitigating the potential influence of transportation34.

Table 3.

Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficients between analytically determined components of PM10 fraction (straight font) and PM2.5 fraction (italics in a gray-shaded rows and columns) measured at the sampling site in Kraków in 2014–2015 (significant correlation coefficients for p < 0.05 are marked in red).

SII—the sum of the concentrations of NH4+, NO3−, NO2−, SO42−

ExCl−—the excess of chlorides calculated as the discrepancy between equivalent concentrations of total chlorides and chlorides bound with sodium cations to form NaCl and then transformed to µg m−3.

Furthermore, a substantial correlation (0.87 for PM10 and 0.84 for PM2.5) was identified concerning the excess of chlorine ions (ExCl−), calculated as the discrepancy between equivalent concentrations of total chlorides and chlorides bound with sodium cations to form NaCl. As reported by Szramowiat-Sala et al.4 combustion processes involving coal and coal-related fuels generate elevated chloride concentrations. Therefore, based on the significant correlation of PAHs with ExCl−, we can infer that the combustion of fossil fuels serves as a primary source of PAHs. Additionally, the correlation between PAHs and levoglucosan (0.88 for PM10 and 0.94 for PM2.5) suggests the combustion of biomass as a further potential origin for PAHs. This finding is further substantiated by the significant correlation between PAHs and K+ (0.65 for PM10).

However, in addition to the strong correlation between PAHs and ExCl− it is important to consider the potential influence of biomass burning as well. Biomass combustion, particularly from wood burning in residential heating, is a significant source of chloride emissions in atmospheric aerosols35. Studies have shown that biomass burning releases substantial amounts of chlorinated organic compounds and inorganic chlorides, including KCl, which can undergo chemical reactions in the atmosphere, leading to the formation of secondary chlorine-containing species28. The observed correlation between PAHs and ExCl⁻ could, therefore, be partially linked to biomass combustion processes, which co-emit both species.

The simultaneous presence of levoglucosan, a widely recognized tracer of biomass burning36, in the analyzed samples further supports this hypothesis. The correlation between levoglucosan and PAHs (0.88 for PM10 and 0.94 for PM2.5) suggests that part of the PAH load may derive from biomass rather than exclusively from fossil fuel combustion. Furthermore, potassium (K⁺), another key marker of biomass combustion, also exhibits a moderate correlation with PAHs (0.65 for PM10), reinforcing the idea that biomass burning plays a non-negligible role in PAH emissions in Kraków.

It is essential to consider that the chemistry of biomass burning emissions differs from that of coal combustion. While coal-related emissions are often enriched in sulfur compounds (such as SO₂), biomass combustion produces a distinctive mixture of organic compounds, including oxygenated PAHs and chlorinated derivatives35. These differences could influence the atmospheric processing and deposition of PAHs, potentially altering their reactivity, transport dynamics, and toxicological impacts. Given the high correlation of PAHs with ExCl⁻, further chemical characterization of chloride-containing species in PM could help delineate the relative contributions of coal versus biomass burning, improving source apportionment efforts and air quality mitigation strategies.

An intriguing aspect worth noting is the correlation between PAHs and another component of organic carbon, namely HULIS (0.69 for PM10). This correlation becomes even more pronounced when considering heavier PAHs, with 5 and 6-ringed PAHs associated with PM10 showing correlations with HULIS ranging from 0.66 to 0.84, and 6-ringed PAHs associated with PM2.5 exhibiting correlations with HULIS in the range of 0.63 to 0.82. The production of humic-like substances is linked to both combustion processes and the formation of secondary organic aerosols in heterogeneous atmospheric reactions37,38. This suggests that PAHs may undergo secondary formation processes, similar to humic-like substances, especially on days when PAH concentrations are relatively low (e.g., Feb 02/03, 2015, and Nov 14–20, 2014). During periods of elevated PAH concentrations, which coincide with increased PM10 and PM2.5 levels, the origin of PAHs is likely more complex. In addition to emissions related to combustion and secondary reactions within Kraków, consideration must be given to transboundary long-range transport as a factor contributing to pollutant origins. To illustrate this, Fig. 5A–C displays backward trajectories (calculated over 72 h for three different altitudes: 300, 800, and 1200 m above sea level) for three sampling periods characterized by varying PAH profiles: December 15/16, 2014, Feb 12/13, 2015, and Mar 05/06.

Fig. 5.

Backward trajectories for three sampling periods: Dec 15/16 2014 (A), Feb 12/13 2015 (B), Mar 05/06 2015 (C)

During these periods, air masses arrived from both the West (Fig. 5A and C) and the South (Fig. 5B). In Fig. 5A and C, the trajectory of the highest air mass appears quite typical. However, in Fig. 4B, the lowest air masses initially arrived from higher altitudes and then descended even lower than 300 m above sea level. Conversely, the highest air masses originated from lower altitudes. This observation suggests the occurrence of temperature inversion phenomena and the substantial accumulation of pollutants above the city, resulting in elevated concentrations of PM and PAHs on Feb 12/13, 2015. During this period, the origin of PAHs likely had a predominantly local character.

A similar situation occurred on Mar 05/06, 2015, when the proportion of heavier PAHs was highest (as depicted in Fig. 4C and D). However, the extended green line in Fig. 5C serves as evidence of long-range transport, which, in addition to local emission sources, evidently contributed to PAH formation.

Investigation of PAHs origin through diagnostic ratios analysis

To ascertain the source of PAHs, researchers commonly employ diagnostic ratios (DRs) derived from the profiles of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. This practice is rooted in the understanding that varying combustion conditions result in distinct PAH profiles3 and different compositions of particulate matter4. Binary diagnostic ratios of PAHs, constructed from pairs of isomeric individual PAHs, serve as effective tools for pinpointing potential sources39. The indicators used and their potential associations with specific sources are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mean values for selected diagnostic ratio indicators for PAHs associated with particulate matter.

| Diagnostic ratio | Value | Potential PAH origin | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) | < 0.2 | Petrogenic emission | 40 |

| 0.35–0.7 | Diesel fuel combustion in a compression-ignition (CI) engine | ||

| > 0.5 | Biomass and coal combustion | ||

| Flu/(Flu + Pyr) | > 0.5 | Diesel fuel combustion in a CI engine | 40,41 |

| < 0.5 | Gasoline fuel combustion in a spark ignition (SI) engine | ||

| BbF/BkF | > 0.5 | Diesel fuel combustion in a CI engine | 40 |

| Pyr/BaP | ~ 1 | Gasoline fuel combustion in a SI engine | 8 |

| Phe/(Phe + Anth) | 0.65; 0.75; 0.73 | Diesel fuel combustion in a CI engine | 41 |

| 0.76; 0.85 | Coal combustion | ||

| Anth/(Anth + Phe) | > 0.1 | Organic matter incomplete combustion | 34,41 |

| < 0.1 | Petrogenic origin of PAHs, petroleum emissions | ||

| > 0.1 | Pyrogenic origin of PAHs, biomass combustion | ||

| Fla/(Fla + Pyr) | > 0.5; 0.57 | Coal combustion | 41 |

| > 0.5; 0.6–0.7 | Diesel fuel combustion in a CI engine | ||

| > 0.5; 0.52 | Gasoline fuel combustion in a SI engine | ||

| 0.52 | Fuel oil | ||

| 0.51; 0.7 | Wood combustion | ||

| > 0.5 | Coal, grass, wood combustion | ||

| 0.4–0.5 | Combustion of natural gas | ||

| BaP/(BaP + Chr) | 0.18–0.49; 0.46; 0.5 | Coal combustion | 41 |

| 0.23 | Steel production | ||

| BaA/(BaA + Chr) | < 0.2 | Petrogenic emission | 41 |

| 0.2–0.35; 0.46; 0.5 | Coal combustion | ||

| 0.5 | The burning of fuel oil | ||

| 0.22–0.55 | Diesel fuel combustion in a CI engine | ||

| 0.5 | Gasoline fuel combustion in a SI engine | ||

| > 0.5 | Biomass and coal | ||

| BaP/(BaP + BeP) | > 0.5 | Combustion-related sources like biomass or coal | 6 |

| < 0.5 | Fresh emissions, particularly from traffic sources |

The diagnostic ratio Anth/(Anth + Phe) less than 0.1 signifies petroleum emissions, whereas values greater than 0.1 indicate biomass combustion. Similarly, a Fla/(Fla + Pyr) ratio below 0.4 is associated with petroleum emissions, values between 0.4 and 0.5 indicate natural gas combustion, and values exceeding 0.5 suggest biomass or coal combustion. For IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) and BaA/(BaA + Chr), ratios below 0.2 signify petrogenic sources. Ratios between 0.2 and 0.35 for BaA/(BaA + Chr) and between 0.2 and 0.5 for IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) suggest mixed sources, such as fossil fuel combustion, crude oil, or vehicle emissions. Ratios exceeding 0.5 for IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) and BaA/(BaA + Chr) are indicative of biomass and coal combustion.

Additionally, the ratio BaP/(BaP + BeP) provides insights into the aging of PAHs. Values greater than 0.5 indicate aged emissions, typically associated with biomass and coal combustion. In contrast, values less than or equal to 0.5 represent fresh emissions, commonly linked to traffic and vehicular sources. BaP/(BaP + BeP) is sensitive to photochemical degradation, as BaP degrades faster than BeP in the atmosphere due to its higher reactivity6.

Table 5 presents the mean values and ranges of specific DRs calculated for PM10 and PM2.5. The results consistently indicate that biomass and coal combustion were the dominant PAH sources, with some influence from vehicular emissions. The Flu/(Flu + Pyr) and Fla/(Fla + Pyr) ratios, which help differentiate between fossil fuel combustion and biomass/coal burning, show values exceeding 0.5 for both PM10 and PM2.5, confirming that combustion processes were the primary contributors to PAH pollution. The IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) ratio, which distinguishes between fossil fuel combustion and biomass/coal combustion, shows low values (0.09 for PM10 and 0.10 for PM2.5), suggesting a strong influence of fossil fuel combustion, likely from coal and traffic emissions. Similarly, the BaP/(BaP + Chr) and BaA/(BaA + Chr) ratios exceed 0.35, further reinforcing the dominance of pyrogenic sources, particularly biomass and coal burning.

Table 5.

The mean values and ranges of diagnostic ratios calculated for PM10 and PM2.5

| PM10 | PM2.5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | Mean | Range | |

| IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) | 0.09 | 0.05–0.23 | 0.10 | 0.04–0.34 |

| Flu/(Flu + Pyr) | 0.64 | 0.35–0.86 | 0.74 | 0.52–0.93 |

| Pyr/BaP | 0.27 | 0.01–1.16 | 0.26 | 0.01–1.24 |

| Phe/(Phe + Anth) | 0.37 | 0.29–0.47 | 0.35 | 0.29–0.44 |

| Anth/(Anth + Phe) | 0.63 | 0.53–0.71 | 0.65 | 0.56–0.71 |

| Fla/(Fla + Pyr) | 0.63 | 0.37–0.82 | 0.68 | 0.45–0.91 |

| BaP/(BaP + Chr) | 0.66 | 0.57–0.75 | 0.65 | 0.36–0.77 |

| BaA/(BaA + Chr) | 0.70 | 0.56–0.89 | 0.64 | 0.45–0.85 |

| BaP/(BaP + BeP) | 0.56 | 0.36–0.79 | 0.63 | 0.50–0.94 |

| BaP/BghiP | 0.75 | 0.40–1.14 | 0.68 | 0.26–1.08 |

Differences between the two particulate fractions indicate that PM2.5 was more affected by atmospheric aging and long-range transport, while PM10 contained relatively fresher emissions from local combustion sources. The BaP/(BaP + BeP) ratio, which assesses photochemical aging, is higher in PM2.5 (0.63) than in PM10 (0.56), suggesting that PAHs bound to fine particles underwent more atmospheric degradation. Additionally, the BaP/BghiP ratio, which differentiates between traffic-related and non-traffic sources, remains close to 0.7 in both fractions, pointing to a mixed influence of vehicle emissions and other combustion sources.

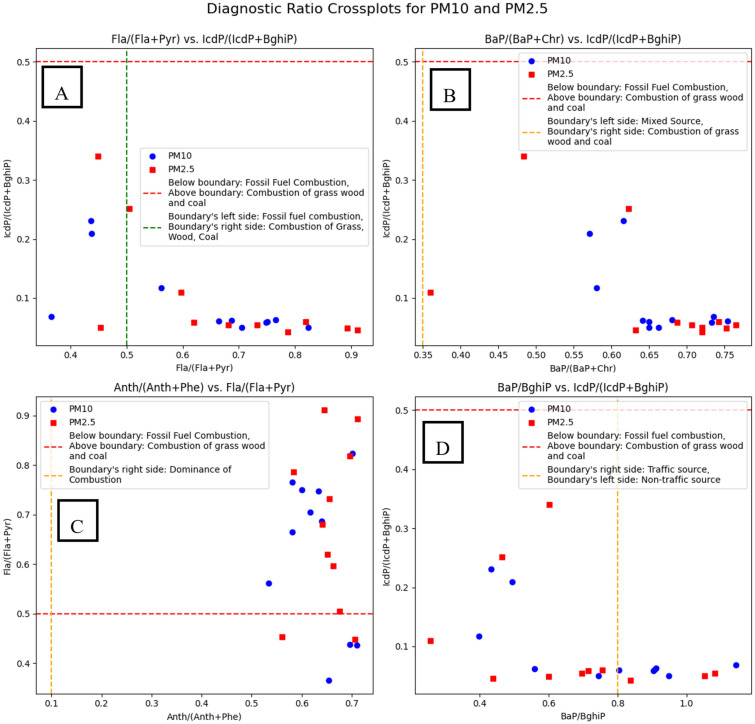

In order to enhance the PAHs source apportionment the diagnostic ratio cross plots have been created (Fig. 6). The Flu/(Flu + Pyr) vs. IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) (Fig. 6A) plot allows differentiation between petrogenic and pyrogenic sources. In the studied samples, values of Flu/(Flu + Pyr) exceeding 0.5 suggest that PAHs originated predominantly from biomass and coal combustion, while values below 0.5 indicate contributions from fossil fuel combustion. Similarly, the IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) ratio helps distinguish between fossil fuel combustion (values below 0.5) and biomass/coal combustion (values above 0.5). The clustering of data points in the pyrogenic region further confirms that incomplete combustion processes, particularly residential heating with coal and biomass, were dominant PAH sources in the study area. Another important plot, BaP/(BaP + Chr) vs. IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) (Fig. 6B), provides insights into the emission sources by distinguishing between petrogenic emissions (BaP/(BaP + Chr) < 0.2), mixed sources (0.2–0.35), and biomass/coal combustion (> 0.35). The results indicate that most data points fall into the biomass and coal combustion category, with only a few samples showing indications of mixed-source pollution. This suggests that domestic heating emissions significantly contributed to PAH levels during the sampling period, which aligns with the peak wintertime pollution episodes recorded in Kraków. The Anth/(Anth + Phe) vs. Flu/(Flu + Pyr) plot (Fig. 6C) supports these findings by further distinguishing between biomass burning and fossil fuel combustion. The Anth/(Anth + Phe) ratio exceeding 0.1 in most samples confirms the dominance of combustion-related PAHs, while Flu/(Flu + Pyr) values between 0.4 and 0.5 indicate a mix of fossil fuel and biomass burning. These observations align with the region’s known pollution sources, where both coal-fired heating and wood burning contribute significantly to ambient air quality deterioration. Lastly, the BaP/BghiP vs. IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) plot (Fig. 6D) provides additional evidence of source contributions, specifically differentiating between traffic-related and non-traffic sources. The results show that BaP/BghiP values are generally above 0.8, suggesting a dominant non-traffic source, such as residential heating and industrial emissions. The IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) values confirm this trend, with most values exceeding 0.5, further reinforcing the strong influence of biomass and coal combustion.

Fig. 6.

Cross plots of different diagnostic ratio used for source identification of PAHs in atmosphere.

The diagnostic ratio analysis in this study aligns well with previous research on PAH source apportionment, reinforcing the dominance of biomass and coal combustion as primary contributors to air pollution. Consistent with Sofowote et al.42, the Ant/(Ant + Phe) and BaA/(BaA + Chr) ratios effectively differentiate combustion sources from petrogenic emissions, though our results indicate a stronger influence of residential heating rather than industrial emissions. Similar to Tobiszewski and Namieśnik7, our study highlights the importance of combining multiple diagnostic ratios, allowing for a clear distinction between vehicular emissions and biomass/coal burning. The Flu/(Flu + Pyr) and IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) ratios confirm the predominance of pyrogenic PAHs, with a notable contribution from coal combustion. Moreover, in agreement with Onaiwu and Ifijen43, our findings reveal that major contributors to PAHs included gasoline combustion, diesel combustion, traffic emissions, and emissions from vehicle panel welding. However, they also concluded that application of diagnostic ratios has some limitations. Mainly due to the fact that PAHs can originate from various sources, and ratios may not always definitively indicate the primary source.

PAHs toxicity and their relative carcinogenicity

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons belong to the group of most hazardous chemical substances that can be found in the environment due to their carcinogenic and mutagenic properties. Their influence is especially dangerous when their concentrations, either in the atmosphere, water or other media are elevated continuously44.

The carcinogenicity of PAHs usually increases with the number of organic rings in the structure. Thus, five-ringed aromatic hydrocarbons, such as benzo(a)pyrene, benzo(b)fluoranthene and dibenzo(a,h)anthracene have the strongest mutagenic and carcinogenic properties45. Benzo(a)pyrene was classified as a PAHs presence indicator due to its common occurrence, high concentrations among them and relatively high carcinogenicity.

The relative carcinogenicity coefficient is a base for the determination of the PAHs exposure index which indicates the intensity of adverse affection for the mixture of given PAH compounds, giving information about the potential hazard of carcinogenic air pollutants. The Interdepartmental Commission on NDS and NDN Registration (ICNNR) in Poland introduced a specific index to describe the level of PAH exposition (A) which is defined as shown in Eq. (2):

|

2 |

where:

|

3 |

where Ai—reference index of carcinogenicity for given i-PAH. Ci—i-PAH average concentration during the study period; ki—relative carcinogenicity coefficients for given i-PAH46.

The reference index of carcinogenicity for Kraków during the study period was calculated using the average PAHs concentrations measured for PM2.5 fraction due to its probably higher hazardous impact on human health. The reference index of carcinogenicity reached the value of 0.001 mg m−3. Table 6 shows the results of exposition indexes computed for every sampling day. It can be noticed that both daily and summary emissions do not exceed the specified ICNNR limit of 0,002 mg m−3. As the computations proceeded for 11 samplings, the obtained results cannot be compared to the annual limit of PAHs exposition as mentioned before.

Table 6.

The level of exposition on PAH in Kraków.

| Sampling date | A [mg/m3] | Sampling date | A [mg/m3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nov 14/15 2014 | 6.7 · 10–5 | Feb 05/06 2015 | 4.9 · 10–5 |

| Nov 19/20 2014 | 7.0 · 10–5 | Feb 12/13 2015 | 1.6 · 10–4 |

| Nov 24/25 2014 | 9.3 · 10–5 | Feb 19/20 2015 | 1.1 · 10–4 |

| Dec 01/02 2014 | 7.0 · 10–5 | Feb 26/27 2015 | 8.2 · 10–5 |

| Dec 08/09 2014 | 1.4 · 10–4 | Mar 05/06 2015 | 7.1 · 10–5 |

| Dec 15/16 2014 | 1.3 · 10–4 |

The mutagenic and toxic health hazard of the PAHs mixture were quantitatively expressed as the MEQ and TEQ, respectively, relating to the mutagenic potential of BaP46 and toxicity of the 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD)47. The TEQ and MEQ were calculated as expressed by Eqs. (4) and (5) for each site, separately for PM2.5 and PM10, based on concentrations and toxicity/mutagenicity equivalence factors for given PM-bound PAHs. In addition, the contribution of carcinogenic PAHs to total measured PAHs content (ΣPAHcarc/ΣPAH) was also determined for PM10 and PM2.5 fractions (Table 7), with the approach described by Eq. (6).

|

4 |

|

5 |

|

6 |

Table 7.

The ranges of diurnal values (first column) and average values determined during measuring period (second column) expressed as contribution of carcinogenic PAH to total PAH (ΣPAHcarc/ΣPAH), mutagenic (MEQ) and TCDD-toxic (TEQ) equivalents for PM2.5 and PM10 in Kraków.

| November | December | February | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM10 | ||||||

|

0.41–0.69 | 0.51 | 0.5–0.56 | 0.55 | 0.48–0.60 | 0.54 |

| MEQ, [mg m−3] | 7.49–40.77 | 18.59 | 16.49–56.49 | 31.34 | 8.85–53.25 | 30.51 |

| TEQ, [mg m−3] | 0.04–0.12 | 0.07 | 0.06–0.15 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.1 |

| PM2.5 | ||||||

|

0.44–0.51 | 0.47 | 0.48–0.56 | 0.53 | 21.37–66.37 | 0.53 |

| MEQ, [mg m−3] | 8.99–31.46 | 20.52 | 35.90–73.21 | 37.37 | 0.48–0.59 | 35.09 |

| TEQ, [mg m−3] | 0.05–0.34 | 0.16 | 0.30–0.53 | 0.30 | 0.15–0.39 | 0.24 |

As presented in Table 7, the carcinogenic PAHs contributed to the total PAHs in ca. 50% both in PM10 and PM2.5 in November, December and February. The mutagenic activity of PAHs was mostly visible in the PM2.5 fraction exhibiting the higher mean values of MEQ in the contrary to MEQPM10. A similar relation was reported in the toxic activity of PAHs: PM2.5-bound PAHs were more toxic during the conducted measuring campaigns than PM10-bounded PAHs. On the basis of comparison of MEQ and TEQ values, it may be stated that mutagenic activity was from ca. 20 to 30 times higher than toxic activity of these pollutants. Liu et al.32 calculated the toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) to assess the carcinogenic risk of PAH mixtures, expressing the toxicity in terms of benzo[a]pyrene equivalent concentrations (BaPTEQ). They found that the average BaPTEQ concentrations were 3.14 ± 1.27 ng/m3 for PM2.5 and 8.23 ± 1.55 ng/m3 for PM10, indicating significant health risks associated with PAH exposure in these particulate fractions. The toxicity and mutagenicity values reported by Kozłowska and Kozielska29 were significantly lower than those observed in our study, with differences reaching several orders of magnitude. Despite this discrepancy in absolute values, both studies indicate a consistent trend—PAH mutagenicity was found to be stronger than its toxicity, suggesting that PAHs have a considerable potential to induce genetic mutations, even at lower toxicity levels. Furthermore, their findings revealed that PAHs bound to PM1 exhibited higher carcinogenic potential compared to those associated with PM2.5, a pattern that aligns with our results. This observation supports the hypothesis that finer particles (PM1 and ultrafine fractions) pose a greater risk to human health, as they not only contain a higher proportion of high-molecular-weight PAHs but also have an increased ability to penetrate deeper into the respiratory system. Our study reinforces this conclusion, as PAHs bound to smaller particulate fractions demonstrated a greater carcinogenic and mutagenic impact, highlighting the importance of monitoring fine and ultrafine PM-bound PAHs in air pollution assessments.

Conclusions

The city of Kraków copes with poor air quality, due to industrial and automotive pollution, outworn residential heating systems, and long-range transport of pollutants. The city’s geographical location in a basin exacerbates pollution trapping due to temperature inversion effects. The study was conducted to assess the levels of PM10 and PM2.5, as well as various particulate matter constituents, organic and elemental carbon, and inorganic ions and to find relationship between the analytic results. This campaign spanned three months during the winter of 2014 and 2015. PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations in Kraków were found to be significantly elevated during the study period. These high levels pose a risk to public health. The concentration of 18 different PAHs was quantified and it was found that 4-, 5-, and 6-ringed PAHs were the predominant constituents in both PM10 and PM2.5. These PAHs collectively accounted for a significant portion of the total PAHs measured. The concentrations of PAHs exhibited temporal variability, with notable increases during specific episodes in December 2014 and February 2015. The study highlighted the complexity of the origins of PAHs in the atmosphere. The analysis of backward trajectories and PAH-diagnostic ratios suggested a combination of local and transported sources during certain periods. Incomplete combustion and coal combustion, along with potential contributions from diesel exhaust and steel production, were possible sources of PAHs in Kraków. PAHs in Kraków’s atmosphere were found to have high mutagenic activity, as indicated by the mutagenic equivalent quotient (MEQ), and lower toxic activity, as indicated by the toxic equivalent quotient (TEQ). Carcinogenic PAHs contributed significantly to the total measured PAH content. The calculated exposure index for PAHs in Kraków did not exceed the specified ICNNR limit, suggesting that daily and summary emissions during the study period were within acceptable limits.

In summary, the study underscores the significant presence of PAHs in Kraków’s atmosphere, with potential health implications due to their carcinogenic and mutagenic properties. It highlights the need for continued monitoring and mitigation efforts to reduce PAH emissions and improve air quality in the city, especially during episodes of elevated pollution. Additionally, the study emphasizes the complex nature of PAH sources in urban environments, with both local and transported contributions playing a role.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of AGH University of Kraków (Grant Number: 16.16.210.476). Research was partly supported by program “Excellence initiative—research university” for the AGH University of Kraków.

Author contributions

Katarzyna Szramowiat-Sala: Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Data Curation, Investigation, Validation, Visualization Marta Marczak-Grzesik: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation Mateusz Karczewski: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation Magdalena Kistler: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing Anneliese Kasper-Giebl: Resources ,Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing Katarzyna Styszko: Resources ,Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Data availability

Data presented in this paper are not available in any data repository. They may be shared on a special request sent to Katarzyna Szramowiat-Sala (katarzyna.szramowiat@agh.edu.pl) or Katarzyna Styszko (styszko@agh.edu.pl).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-91018-8.

References

- 1.Kim, K. H., Jahan, S. A., Kabir, E. & Brown, R. J. C. A review of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their human health effects. Environ. Int.60, 71–80 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hien, T. T., Thanh, L. T., Kameda, T., Takenaka, N. & Bandow, H. Distribution characteristics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with particle size in urban aerosols at the roadside in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Atmos. Environ.41, 1575–1586 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szramowiat-Sala, K. et al. The properties of particulate matter generated during wood combustion in in-use stoves. Fuel253, 792–801 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szramowiat-Sala, K. et al. Comparative analysis of real-emitted particulate matter and PM-bound chemicals from residential and automotive sources: A case study in Poland. Energies10.3390/en16186514 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danek, T., Weglinska, E. & Zareba, M. The influence of meteorological factors and terrain on air pollution concentration and migration: A geostatistical case study from Krakow, Poland. Sci. Rep.12, 11050 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yunker, M. B. et al. PAHs in the Fraser River basin: A critical appraisal of PAH ratios as indicators of PAH source and composition. Org Geochem33, 489–515 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tobiszewski, M. & Namieśnik, J. PAH diagnostic ratios for the identification of pollution emission sources. Environ. Pollut.162, 110–119 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravindra, K., Sokhi, R. & Van Grieken, R. Atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source attribution, emission factors and regulation. Atmos. Environ.42, 2895–2921 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaciera, M., Kurek, J., Feist, B. & Pyta, H. The exposure profiles, correlation factors and comparison of PAHs and nitro-PAHs in urban and non-urban regions in suspended particulate matter in Poland. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd.39, 374–382 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siudek, P. & Frankowski, M. The role of sources and atmospheric conditions in the seasonal variability of particulate phase PAHs at the urban site in central Poland. Aerosol Air Qual. Res.18, 1405–1418 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siudek, P. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in coarse particles (PM10) over the coastal urban region in Poland: Distribution, source analysis and human health risk implications. Chemosphere311, 137130 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siudek, P. Seasonal distribution of PM2.5-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as a critical indicator of air quality and health impact in a coastal-urban region of Poland. Sci. Total Environ.827, 154375 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogula-Kozłowska, W. et al. PM2.5 in the central part of Upper Silesia, Poland: Concentrations, elemental composition, and mobility of components. Environ. Monit. Assess185, 581–601 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ćwiklak, K., Pastuszka, J. S. & Rogula-Kozłowska, W. Influence of traffic on particulate-matter polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban atmosphere of Zabrze, Poland. Pol. J. Environ. Stud.18, 579–585 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bralewska, K. & Rakowska, J. Concentrations of particulate matter and PM-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons released during combustion of various types of materials and possible toxicological potential of the emissions: The results of preliminary studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health.10.3390/ijerph17093202 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Committee for Standardization (CEN). Ambient Air - Standard Gravimetric Measurement Method for the Determination of the PM10 or PM2,5 Mass Concentration of Suspended Particulate Matter. (2023).

- 17.U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. Priority pollutants. https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/rwqcb7/board_decisions/adopted_orders/orders/2005/05_0082g.pdf.

- 18.Styszko, K. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their nitrated derivatives associated with PM10 from Kraków city during heating season. E3S Web Conf.10, 00091 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szramowiat-Sala, K. et al. The properties of particulate matter generated during wood combustion in in-use stoves. Fuel253, 792–801 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skiba, A. et al. Source apportionment of suspended particulate matter (PM1, PM2.5 and PM10) collected in road and tram tunnels in Krakow, Poland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.31, 14690–14703 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iinuma, Y., Engling, G., Puxbaum, H. & Herrmann, H. A highly resolved anion-exchange chromatographic method for determination of saccharidic tracers for biomass combustion and primary bio-particles in atmospheric aerosol. Atmos. Environ.43, 1367–1371 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limbeck, A., Handler, M., Neuberger, B., Klatzer, B. & Puxbaum, H. Carbon-specific analysis of humic-like substances in atmospheric aerosol and precipitation samples. Anal. Chem.77, 7288–7293 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jankowski, N., Schmidl, C., Marr, I. L., Bauer, H. & Puxbaum, H. Comparison of methods for the quantification of carbonate carbon in atmospheric PM10 aerosol samples. Atmos. Environ.42, 8055–8064 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szramowiat, K., Styszko, K., Kistler, M., Kasper-Giebl, A. & Gołaś, J. Carbonaceous species in atmospheric aerosols from the Krakow area (Malopolska District): Carbonaceous species dry deposition analysis. E3S Web Conf.10, 00092 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szramowiat-Sala, K. et al. Comparative analysis of real-emitted particulate matter and PM-bound chemicals from residential and automotive sources: A case study in Poland. Energies10.3390/en16186514 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pacura, W., Szramowiat-Sala, K., Macherzyński, M., Gołaś, J. & Bielaczyc, P. Analysis of micro-contaminants in solid particles from direct injection gasoline vehicles. Energies10.3390/en15155732 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urbančok, D., Payne, A. J. R. & Webster, R. D. Regional transport, source apportionment and health impact of PM10 bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Singapore’s atmosphere. Environ. Pollut.229, 984–993 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitby, K. T. The physical characteristics of sulfur aerosols. Atmos. Environ.1967(12), 135–159 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogula-Kozłowska, W., Kozielska, B. & Klejnowski, K. Concentration, origin and health hazard from fine particle-bound PAH at three characteristic sites in Southern Poland. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.91, 349–355 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rolle, F., Maurino, V. & Sega, M. Metrological traceability for benzo[a]pyrene quantification in airborne particulate matter. Accreditat. Qual. Assur.17, 191–197 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaleta, D. & Kozielska, B. Spatial and temporal volatility of PM2.5, PM10 and PM10-bound B[a]P concentrations and assessment of the exposure of the population of Silesia in 2018–2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health20, 138 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, X. et al. Analysis of PAHs associated with PM10 and PM2.5 from different districts in Nanjing. Aerosol Air Qual. Res.19, 2294–2307 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, D. et al. Concentration, source identification, and exposure risk assessment of PM2.5-bound parent PAHs and nitro-PAHs in atmosphere from typical Chinese cities. Sci. Rep.7, 10398 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birch, M. E. & Cary, R. A. Elemental carbon-based method for occupational monitoring of particulate diesel exhaust: Methodology and exposure issues. Analyst121, 1183–1190 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen, J. et al. A review of biomass burning: Emissions and impacts on air quality, health and climate in China. Sci. Total Environ.579, 1000–1034 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidl, C. et al. Chemical characterisation of fine particle emissions from wood stove combustion of common woods growing in mid-European Alpine regions. Atmos. Environ.42, 126–141 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Limbeck, A., Kulmala, M. & Puxbaum, H. Secondary organic aerosol formation in the atmosphere via heterogeneous reaction of gaseous isoprene on acidic particles. Geophys. Res. Lett.10.1029/2003GL017738 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellis, E. C., Novakov, T. & Zeldin, M. D. Thermal characterization of organic aerosols. Sci. Total Environ.36, 261–270 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tobiszewski, M. & Namieśnik, J. PAH diagnostic ratios for the identification of pollution emission sources. Environ. Pollut.162, 110–119 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delgado-Saborit, J. M., Stark, C. & Harrison, R. M. Carcinogenic potential, levels and sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mixtures in indoor and outdoor environments and their implications for air quality standards. Environ. Int.37, 383–392 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ravindra, K., Sokhi, R. & Van Grieken, R. Atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source attribution, emission factors and regulation. Atmos. Environ.42, 2895–2921 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sofowote, U. M., Allan, L. M. & McCarry, B. E. Evaluation of PAH diagnostic ratios as source apportionment tools for air particulates collected in an urban-industrial environment. J. Environ. Monit.12, 417–424 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Onaiwu, G. E. & Ifijen, I. H. PM2.5-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): Quantification and source prediction studies in the ambient air of automobile workshop using the molecular diagnostic ratio. Asian J. Atmos. Environ.18, 6 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organisation. Health Risks of Persistent Organic Pollutants from Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution. (2003).

- 45.Sakshi, A. K. & Haritash,. A comprehensive review of metabolic and genomic aspects of PAH-degradation. Arch. Microbiol.202(8), 2033–2058. 10.1007/s00203-020-01929-5 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nisbet, I. C. T. & LaGoy, P. K. Toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.16, 290–300 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willett, K. L., Gardinali, P. R., Sericano, J. L., Wade, T. L. & Safe, S. H. Characterization of the H4IIE rat hepatoma cell bioassay for evaluation of environmental samples containing polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.32, 442–448 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this paper are not available in any data repository. They may be shared on a special request sent to Katarzyna Szramowiat-Sala (katarzyna.szramowiat@agh.edu.pl) or Katarzyna Styszko (styszko@agh.edu.pl).