Summary

Amphetamine (AMPH) exerts metabolic and cardiovascular effects. The central melanocortin system is a key regulator of both metabolic and cardiovascular functions. Here, we show that the melanocortin system partially mediates AMPH-induced anorexia, energy expenditure, tachycardia, and hypertension. AMPH increased α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (αMSH) secretion from the hypothalamus, elevated blood pressure and heart rate (HR), increased brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis, and reduced both food intake (FI) and body weight (BW). In melanocortin 4 receptor-deficient (MC4R knockout [KO]) mice, metabolic and cardiovascular effects of AMPH were significantly attenuated. Antagonism of serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmitter systems attenuated AMPH-induced αMSH secretion as well as AMPH-induced metabolic and cardiovascular effects. We propose that AMPH increases serotonergic activation of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons and reduces the noradrenergic inhibition of POMC neurons, thereby disinhibiting them. Together, these presynaptic mechanisms result in increased POMC activity, increased αMSH secretion, and increased activation of MC4R pathways that regulate both the metabolic and cardiovascular systems.

Keywords: amphetamine, food intake, body weight, weight loss, obesity, energy expenditure, BAT, thermogenesis, hypertension, blood pressure, cardiovascular, melanocortin system, MC4R

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Amphetamine indirectly depolarizes a subpopulation of POMC neurons via the activation of excitatory serotonergic inputs and the suppression of inhibitory noradrenergic inputs

-

•

Amphetamine activates POMC neurons, via MC4R, to reduce food intake and body weight

-

•

The tachycardic and hypertensive effects of amphetamine are partially dependent on the melanocortin system

-

•

Antagonism of the melanocortin system prevents AMPH-induced hypertension and tachycardia

Simonds et al. demonstrate that amphetamine (AMPH) causes anorexia, weight loss, tachycardia, and hypertension partially through engagement of the melanocortin system. AMPH activates serotonergic while inhibiting adrenergic pathways to stimulate POMC neurons. Antagonism of the MC4R can prevent these AMPH-induced effects.

Introduction

Amphetamine (AMPH) is a stimulant first synthesized in 1927.1,2,3,4 It is currently prescribed for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, narcolepsy, and obesity.3 Historically AMPH has been used as a nasal decongestant, antidepressant, stimulant, and weight loss agent.3 The drug is widely abused, has a high potential for addiction, and can cause psychosis and other physical and psychological side effects.3 Recent studies have found that the prevalence of AMPH-associated heart failure is increasing and AMPH-associated heart failure is associated with significantly worse co-morbid symptoms.5 This is likely due to AMPH increasing heart rate (HR) and blood pressure; however, the exact mechanism of action of AMPH is unknown.

AMPH increases synaptic concentrations of dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin via agonism of trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1); reversal of plasma membrane monoamine transporters; and inhibition of vesicular monoamine transporters (VMATs) and monoamine oxidase (MAO). Together this leads to increased synaptic release and reduced synaptic reuptake of dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin. Monoamine neurotransmitters are known to impact metabolism; however, the mechanisms by which elevated dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin reduce food intake (FI) and elevate blood pressure remain unclear. Bupropion, a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor, causes modest weight loss.6 The serotonin 2C receptor (5-HT2CR) agonist lorcaserin was previously approved for the treatment of obesity but has recently been withdrawn.7

In animal models, AMPH decreases FI and increases energy expenditure by elevating locomotor activity and thermogenesis.2 At least some of this thermogenic energy expenditure has been attributed to non-CNS mechanisms. Peripherally restricted PEGylated AMPH (PEGyAMPH) increases thermogenesis but does not affect FI, cardiovascular parameters, or locomotor activity.2

Preclinical models have shown that AMPH can modify gene expression in hypothalamic neurons known to regulate metabolism and the cardiovascular system. Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARH) are anorexigenic and signal through the α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH)/melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) pathway to regulate FI, body weight (BW), HR, and blood pressure.8 In rodents, AMPH can modify gene expression in POMC neurons. AMPH can increase expression of cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) mRNA suggesting a mechanistic role of POMC neurons in the inhibition of FI by AMPH.9,10 In rats, AMPH can increase MC4R expression and decrease hypothalamic expression of the orexigenic peptide neuropeptide-Y.11

Here, we investigate the mechanisms by which AMPH induces metabolic and cardiovascular effects. Understanding how AMPH works may lead to identification of new targets for the development of weight loss drugs.

Results

Cellular effects of AMPH

AMPH treatment (5 mg/kg intraperitoneal [i.p.]) significantly increased the number of c-Fos-expressing cells in the mouse hypothalamus (310.8 ± 6.9 vs. 148.7 ± 31.2, p < 0.001; Figure S1A). AMPH treatment significantly increased the percentage of c-Fos-positive POMC neurons in the ARH (20.8 ± 2 vs. 8.3 ± 1.3; Figures 1A and 1B) but did not significantly affect the percentage of c-Fos-positive neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons in the ARH (4.3 ± 1.2 vs. 6.6 ± 2.7; Figures S1B and S1C). In addition to the ARH, a large population of c-Fos-positive cells was found in the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH) after AMPH treatment (113.8 ± 24.5 vs. 33.25 ± 12.5; Figures S1D–S1F).

Figure 1.

Cellular effects of AMPH in vitro

(A) Immunofluorescent image of the mediobasal hypothalamus shows increased colocalization of POMC (green) and c-fos (red) after amphetamine (5 mg/kg i.p.) treatment in mice. Arrows mark cells that colocalize. Scale bar represents 500 microns.

(B) Colocalization of c-Fos and POMC after Vehicle (Veh) or AMPH (5 mg/kg i.p.) treatment in mice. ∗∗p < 0.01, unpaired t test, n = 4, mean ± SEM.

(C) Representative whole-cell current clamp recording of POMC neuron treated with AMPH (10 μM), showing membrane potential depolarization and increased action potential firing frequency followed by washout.

(D) Pie chart showing relative percentages of POMC neurons that were excited (red), inhibited (blue), and did not respond (gray) to bath application of 10 μM AMPH in electrophysiology experiments (n = 46).

(E) αMSH secretion from hypothalamic explants from C57Bl/6J and MC4R KO mice treated with Veh or AMPH (10 mM). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, unpaired t tests, n = 6–19, mean ± SEM (all n are biological replicates).

See also Figure S1.

In visualized patch-clamp electrophysiology experiments, bath application of 10 μM AMPH excited 28% of POMC neurons tested (n = 13; Figures 1C and 1D). 52% of POMC neurons were unaffected by AMPH exposure (n = 24; Figure 1D), and 20% of arcuate POMC neurons were inhibited by AMPH (n = 9) (Figures 1D and S1G). Despite heterogeneous effects of AMPH on POMC electrical activity in vitro, treatment of hypothalamic explants with 10 μM AMPH increased αMSH secretion 2.5-fold, from 11.13 ± 1.4 pg/mL in Veh treatment to 27.93 ± 5.05 pg/mL following AMPH treatment (Figure 1E). There was no effect of AMPH on agouti-related peptide (AgRP) secretion compared to controls (21.7 ± 6.9 pg/mL vs. 13.8 ± 2.4 pg/mL; Figure S1H). In vitro treatment of hypothalamic explants with 10 mM AMPH increased αMSH secretion in MC4R knockout (KO) mice similar to the increase observed in wild-type (WT) mice (14.04 ± 2.34 Veh treatment vs. 24.02 ± 3.93 pg/mL) (Figure 1E). Diet-induced obese (DIO) mice had a significantly lower baseline secretion of α-MSH than lean (chow-fed) mice and obese MC4R KO mice. AMPH caused a 4-fold increase in α-MSH secretion (6.9 ± 2.7 pg/mL) above vehicle treatment (1.7 ± 0.33 pg/mL) (Figure S1I). This increase in α-MSH in response to AMPH was larger than the increase in α-MSH secretion in lean (chow-fed) mice (2.5-fold) and obese MC4R KO mice (1.7-fold) compared to their respective vehicle treatments.

Physiological effects of AMPH

AMPH (5 mg/kg i.p. daily for 3 days) significantly suppressed FI at 24, 48, and 72 h post 1st injection in lean WT, DIO WT, and MC4R KO mice (Figures 2A–2D). The anorexigenic effects of AMPH were most pronounced in WT mice. After 72 h of treatment, average FI for AMPH-treated lean mice was 33.3 ± 2.4 kilocalorie (kcal) compared to 49.6 ± 2.1 kcal in controls (Figure 2A). This amounted to a FI suppression of 16.2 kcal (32.8%) over the 3-day period. At 72 h post AMPH, injected DIO WT mice ate 35.5 ± 2.6 kcal compared to 54.2 ± 2.0 kcal in controls (Figure 2B). This amounted to an 18.7 kcal (34.5%) suppression of FI over the 3-day period. After 72 h of treatment, average FI for AMPH-treated MC4R-deficient mice was also suppressed, but to a lower extent than WT mice; AMPH-treated MC4R mice ate 50.7 ± 3.8 kcal compared to 60.2 ± 3.6 kcal in controls (Figure 2C). This amounted to an AMPH-induced FI suppression of 9.5 kcal (15.7%) over the 3-day period. Pharmacological antagonism of the melanocortin 3 and 4 receptors with SHU9119 (i.p. and intracerebroventricular [i.c.v.]) prevented the hypophagia caused by AMPH (Figures 2E and S1J).

Figure 2.

Blockade or deletion of MC4R reduces the impact of AMPH on blood pressure and heart rate in mice

(A) Cumulative food intake (kcal) of lean C57Bl/6J mice that received daily i.p. injections of Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) daily for 3 days. ∗∗p < 0.01. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multi comparisons test. n = 6, mean ± SEM.

(B) Cumulative food intake (kcal of DIO C57Bl/6J mice that received daily i.p. injections of Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) daily for 3 days. ∗∗p < 0.01. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multi comparison test. n = 6, mean ± SEM.

(C) Cumulative food intake (kcal) of MC4RKO mice that received daily i.p. injections of Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) daily for 3 days. ∗p < 0.05. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multi comparisons test. n = 8, mean ± SEM.

(D) Difference in food intake (kcal) (relative to Veh-treated body weight-matched controls) in lean, DIO and MC4RKO that received daily i.p. injections of Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) for 3 days. ++p < 0.01 DIO vs. MC4R KO, #p < 0.05 lean vs. MC4R KO. Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, n = 6–8, mean ± SEM.

(E) 24 h food intake of DIO following i.p. injection of Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, or SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. One-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, n = 5–17, mean ± SEM.

(F) Percentage change in body weight of lean C57Bl/6J mice that received daily i.p. injections of Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multi comparisons test. n = 6, mean ± SEM.

(G) Percentage change in body weight of DIO C57Bl/6J mice that received daily i.p. injections of Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multi comparisons test. n = 6, mean ± SEM.

(H) Percentage change in body weight of MC4RKO mice that received daily i.p. injections of Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multi comparisons test. n = 8, mean ± SEM.

(I) Percentage difference in body weight (relative to Veh-treated body weight-matched controls) of lean, DIO and MC4RKO mice that received daily i.p. injections of Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) treatment for 3 days. ∗p < 0.05 lean vs. DIO, ++p < 0.01 DIO vs. MC4R KO, #p < 0.05 DIO vs. MC4R KO. Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, n = 6–8, mean ± SEM.

(J) Body weight of DIO mice at baseline and 24 h after i.p. injection of Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, and SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗∗p < 0.01, two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. n = 9–21. mean ± SEM.

(K) Change in BAT temperature (°C), in lean mice treated i.p. with Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) daily for 3 days. ∗∗p < 0.01. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multi comparisons test. n = 4, mean ± SEM.

(L) Change in BAT temperature (°C), in DIO mice treated i.p. with Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) daily for 3 days. ∗p < 0.05. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multi comparisons test. n = 4, mean ± SEM.

(M) Change in BAT temperature (°C) in MC4R KO mice treated i.p. with Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) daily for 3 days. ∗p < 0.05. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s multi comparisons test. n = 6, mean ± SEM.

(N) Change in BAT temperature (∘C) in lean, DIO, and MC4R KO mice that received daily i.p. injections of Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) once daily for 3 days. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 lean vs. MC4R KO, ++p < 0.01 DIO vs. MC4R KO. Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, n = 6–8, mean ± SEM.

(O) Average BAT temperature (∘C) of DIO mice for the 4 h immediately after i.p. injection off Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), Shu9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, and Shu9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05. One-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, n = 5–12, mean ± SEM (all n are biological replicates).

See also Figure S1.

AMPH treatment significantly decreased BW in lean and DIO WT and MC4R-deficient mice at 24, 48, and 72 h post injection, although the effect in MC4R-deficient mice was significantly less than that in lean and DIO mice (Figures 2F–2I). In lean mice 72 h post 1st treatment, average BW for AMPH-treated animals was reduced by 4.1% ± 0.7% and increased by 1.1% ± 0.5% in vehicle-treated mice (Figure 2F). In DIO mice by 72 h post 1st treatment, average BW for AMPH-treated animals was reduced by 4.3% ± 0.6%, while it was increased by 0.6% ± 0.3% in controls (Figure 2G). In MC4R-deficient mice by 72 h post 1st treatment, BW was reduced by 1.7% ± 0.7% in AMPH-treated compared to an increase of 0.4% ± 0.4% in controls (Figure 2H). In DIO mice treated with AMPH, BW significantly decreased by 1.2% over 24 h; however, pre-treatment with SHU 9119 prevented AMPH-induced weight loss (Figure 2J). A similar effect on BW was observed when DIO mice were i.c.v. treated with SHU 9119, blocking AMPH ability to cause as great a weight loss (Figure S1K).

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) temperature was significantly increased by AMPH treatment in lean, DIO, and MC4R KO mice at 24 and 48 h post 1st injection (Figures 2K–2N). However, in all animals, BAT temperature was no longer significantly elevated 72 h post AMPH injection. In lean WT mice, 24 h post 1st injection, BAT temperature of AMPH-treated mice was elevated by 0.90°C ± 0.08°C compared to a change of 0.07°C ± 0.07°C in Veh-treated mice (Figure 2K). In DIO WT mice, 24 h post 1st injection, BAT temperature change of AMPH-treated mice was elevated by 0.60°C ± 0.08°C compared to a change of −0.01°C ± 0.1°C in controls (Figure 2L). In MC4R KO mice, 24 h post 1st injection, BAT temperature of AMPH-treated mice was significantly elevated by 0.30°C ± 0.06°C compared to a change of 0.02°C ± 0.06°C in controls (Figure 2M). This increase in response to AMPH was significantly less in MC4R KO than the increase in lean and DIO WT mice (Figure 2N). In DIO mice, Veh + AMPH treatment significantly increased BAT temperature compared to Veh + Veh-treated mice. SHU 9119 (i.p.) + AMPH treatment still significantly elevated BAT temperature compared to SHU 9119 + Veh treatment (Figure 2O)

Weight-matched MC4R KO (54.5 ± 3.0 g) mice and DIO (57.7 ± 1.9 g) mice were given a single injection of AMPH or Veh. Locomotor activity was significantly increased in both DIO and MC4R KO mice treated with AMPH compared to Veh (Figures S2A–S2D). Pre-treatment with SHU 9119 (i.p.) attenuated the locomotor stimulant effect of AMPH in DIO mice (Figure 3A). AMPH increased systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in DIO and MC4R KO mice compared to Veh-treated mice (Figures S2E–S2L). AMPH increased blood pressure and HR more in DIO mice than in MC4R KO mice (Figures 3B–3G). The average 2 h post injection increase in SBP in DIO mice was 29.6 ± 4.3 mmHg, significantly greater than the increase of 13.6 ± 3.2 mmHg in MC4R KO mice (Figures 3B and 3C). Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was increased by AMPH in DIO and MC4R KO mice (Figures 3D and 3E). In the 2 h after AMPH injection, DIO mice HR was increased by 99.7 ± 25.07 beats per minute (BPM) compared to 37.3 ± 16.3 BPM in MC4R KO mice (Figures 3F and 3G). AMPH did not significantly increase HR in MC4R KO mice compared to Veh-treated mice (Figures S2M–S2P).

Figure 3.

Blockade or deletion of MC4R reduces the impact of AMPH on blood pressure and heart rate in mice

(A) Locomotor activity (arbitrary units) in DIO mice for 3 h post i.p. injection of Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), Shu9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, or Shu9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 4–13, mean ± SEM.

(B) SBP change (mmHg) in DIO and MC4RKO mice. Mice received i.p. injection of AMPH at 60 min. n = 6–12, mean ± SEM.

(C) DIO and MC4KO mice average SBP change (mmHg) over 2 h immediately following i.p. AMPH (5 mg/kg) injection. ∗p < 0.05, unpaired t test, n = 6–12, mean ± SEM.

(D) DIO and MC4R KO mice DBP change (mmHg) over 180 min (i.p. AMPH injected at 60 min). n = 6–12, mean ± SEM.

(E) DIO and MC4R KO mice average DBP change (mmHg) over 2 h immediately following i.p. injections of AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, unpaired t test, n = 6–12, mean ± SEM.

(F) DIO and MC4R KO mice HR change (BPM) over 180 min (i.p. AMPH [5 mg/kg] injected at 60 min). n = 6–12, mean ± SEM.

(G) DIO and MC4R KO mice average HR change (BPM) over 2 h immediately following i.p. injections of AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, unpaired t test, n = 6–12, mean ± SEM.

(H) SBP change (mmHg) of DIO mice that received i.p. injections of Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, or SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg) (1st i.p. injection at 45 min, 2nd at 60 min). n = 6–7, mean ± SEM.

(I) DIO mice average SBP change (mmHg) over 1 h immediately following i.p. injections of Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, or SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 6–7, mean ± SEM.

(J) DBP change (mmHg) of DIO mice that received i.p. injections of Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), or SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, or SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg). (1st i.p. injection at 45 min, 2 nd at 60 min). n = 6–7, mean ± SEM.

(K) DIO mice average DBP change (mmHg) over 1 h immediately following i.p. injections of Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, or SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 6–7, mean ± SEM.

(L) HR change (BPM) of DIO mice that received i.p. injections of Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, or SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg) (1st i.p. injection at 45 min, 2nd at 60 min). n = 6–7, mean ± SEM.

(M) DIO mice average HR change (BPM) over 1 h immediately following i.p. injections of Veh + Veh, Veh + AMPH (5 mg/kg), SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + Veh, or SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) + AMPH (5 mg/kg). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 6–7, mean ± SEM (all n are biological replicates).

See also Figures S2 and S3.

In DIO mice, the effects of AMPH on cardiovascular parameters were significantly blunted by antagonism of the melanocortin system (Figures 3H–3M; Figure S3A). AMPH treatment in DIO mice increased SBP by an average of 27.2 ± 7.3 mmHg 1 h post injection (Figures 3H and 3I). SHU 9119 + Veh treatment decreased SBP by 34.2 ± 7 mmHg in the 1 h post treatment (Figures 3H and 3I). The combination of SHU 9119 + AMPH significantly reduced SBP by 17 mmHg compared to AMPH + Veh treatment alone and reduced SBP by 9.9 ± 12.9 mmHg from baseline (Figures 3H and 3I). In DIO mice, Veh + AMPH treatment significantly increased DBP compared to Veh + SHU 9119, which decreased DBP in the 1st h by an average 32.6 ± 6.6 mmHg, and SHU 9119 + AMPH, which decreased DBP by 13.1 ± 12.8 mmHg (Figures 3H and 3I). SHU 9119 + Veh (−43.9 ± 31.8 BPM) and SHU 9119 + AMPH (−36.5 ± 38.9 BPM) both significantly decreased HR relative to Veh + AMPH (Veh + AMPH treatment significantly elevated HR by 83.2 ± 19.5 BPM over the 1st hour post injection) (Figures 3L and 3M). Central SHU 9119 administration blocked AMPH ability to increase SBP (Figure S3A).

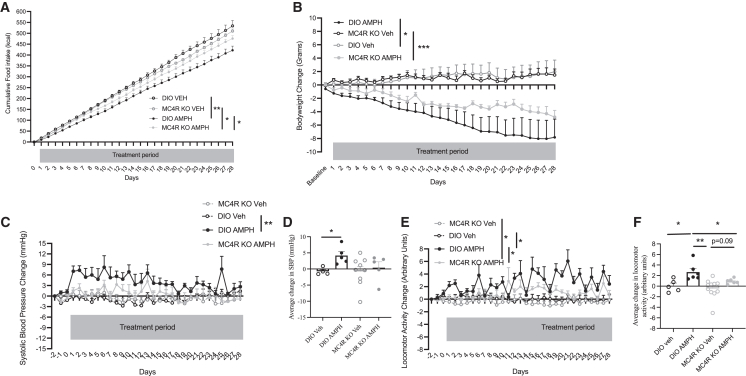

In DIO mice, chronic AMPH administration significantly suppressed cumulative FI from day 4 thereafter, compared to Veh-treated DIO mice (Figure 4A). After 28 days, cumulative FI was 422 ± 24.6 kcal in AMPH-treated DIO mice, 21% lower FI compared to Veh-treated DIO mice, which ate an average 534 ± 25 kcal. 28-day AMPH-treated MC4R KO mice consumed on average 476 ± 14 kcal, which was 11% more than what AMPH-treated DIO mice ate (Figure 4A). Cumulative FI was significantly different between AMPH-treated MC4R KO mice and Veh-treated MC4R KO mice, which ate an average 510 ± 9.45 kcal (Figure 4A). After 28 days of AMPH treatment, DIO mice lost 8 ± 2.7 g (13% from baseline) BW, which was more than what MC4R KO mice lost, i.e., 4.8 ± 1 g (6.4% ± 1%) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of chronic AMPH treatment in DIO and MC4R KO mice

(A) Cumulative food intake (kcal) of DIO and MC4RKO mice, treated with daily i.p. injections of either Veh or AMPH for 28 days. ∗∗p < 0.006, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Two-way ANOVA (mixed effects model), Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. n = 5–7, mean ± SEM.

(B) Body weight change (g) of DIO and MC4RKO mice, treated with daily i.p. injections of either Veh or AMPH for 28 days. ∗∗∗p < 0.006, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 5–7, mean ± SEM.

(C) SBP change (mmHg) of DIO and MC4RKO mice, treated with daily i.p. injections of either Veh or AMPH for 28 days. ∗p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 5–7, mean ± SEM.

(D) Average change in SBP (mmHg) of DIO and MC4RKO mice, injected i.p. daily with either Veh or AMPH for 28 days. ∗∗p < 0.05, unpaired t test. n = 5–7, mean ± SEM.

(E) Activity change (arbitrary units) of DIO and MC4RKO mice, treated with daily i.p. injections of either Veh or AMPH for 28 days. Two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. n = 5–7, mean ± SEM.

(F) Average change in locomotor activity (arbitrary units) of DIO and MC4RKO mice, injected i.p. daily with either Veh or AMPH for 28 days. ∗p < 0.05 unpaired t test. n = 5–7, mean ± SEM (all n are biological replicates).

See also Figure S4.

Average baseline SBP of MC4R KO mice was lower than that of DIO mice (117.1 ± 2.8 mmHg vs. 132.5 ± 1.9 mmHg p < 0.001). After 1 day of AMPH treatment, DIO mice had significantly elevated SBP from baseline (7.1 ± 1.2 mmHg) compared to Veh (0.3 ± 0.6 mmHg)-treated mice; by day 2, it increased by 8.15 ± 1.3 mmHg (AMPH) vs. −0.17 ± 0.4 mmHg (Veh) (p < 0.05) (Figure 4C). The AMPH-induced increase in SBP in DIO mice waned over the 28-day period, likely due to decreasing BW. Nonetheless, the average change in SBP of AMPH-treated DIO mice over the entire 28-day treatment period was 4.1 ± 1.2 mmHg compared to 0.4 ± 1.8 mmHg in Veh-treated DIO mice (p < 0.01) (Figures 4C and 4D). HR was not different between any groups over the entire 28-day treatment period (Figure S4A).

AMPH treatment significantly increased locomotor activity in DIO mice over the 28-day treatment period by an average of 2.7 ± 0.9 arbitrary unit compared to an average change in activity of 0.06 ± 0.5 arbitary unit in Veh-treated mice (p < 0.05) (Figures 4E and 4F). In MC4R KO mice, AMPH treatment across the 28 days did not significantly increase locomotor activity (Figures 4E and 4F). The increase in locomotor activity in DIO AMPH-treated mice was significantly higher than that seen in MC4R KO AMPH-treated mice (p < 0.05) (Figure 4F).

Blockade of AMPH effects

Pre-treatment of hypothalamic explants with SB242084 alone or Carvedilol (CAR) plus phentolamine mesylate (PHE), to antagonize 5-hydroxytryptamin (5-HT)2CR or alpha- and beta-noradrenergic receptors, respectively, prevented AMPH-induced secretion of αMSH (Figure 5A). Pre-treatment with the D2 receptor antagonist, L-741626, significantly increased AMPH-induced αMSH secretion. Pre-treatment with a D1 receptor antagonist (SKF83566 hydrobromide) or D3 receptor antagonist (GR103691) did not significantly change AMPH-induced αMSH secretion (Figure 5B). SB242084 alone or CAR plus PHE or SB242084 plus CAR plus PHE prevented AMPH-induced weight loss (Figure 5C) and blocked AMPH-induced hypophagia (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

AMPH acts through both the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems to impact the melanocortin system actions on metabolism and blood pressure

(A) αMSH secretion from hypothalamic explants in response to artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF), SB242084, CAR and PHE, aCSF + AMPH, SB242084 + AMPH, and CAR and PHE + AMPH. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 6–21, mean ± SEM.

(B) αMSH secretion from hypothalamic explants in response to aCSF, aCSF + AMPH, L-741626 + AMPH, SKF83566 + AMPH, and GR103691 + AMPH. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 6–7, mean ± SEM.

(C) Percentage body weight change of DIO mice, 24 h post treatment with i.c.v. Veh + i.p. Veh; i.c.v. Veh + i.p. AMPH (5 mg/kg i.p.); i.c.v. SB242084 + i.p. Veh; i.c.v. SB242084 + i.p. AMPH (5 mg/kg); i.c.v. CAR and PHE + i.p. Veh; i.c.v. CAR and PHE + i.p. AMPH (5 mg/kg); i.c.v. CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + Veh; or i.c.v. CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + i.p. AMPH (5 mg/kg). One-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, n = 5–8, mean ± SEM.

(D) 24-h food intake (kcal) of DIO mice treated with i.c.v. Veh + i.p. Veh; i.c.v. Veh + i.p. AMPH (5 mg/kg); i.c.v. SB242084 + i.p. Veh; i.c.v. SB242084 + i.p. AMPH (5 mg/kg); i.c.v. CAR and PHE + i.p. Veh; i.c.v. CAR and PHE + i.p. AMPH (5 mg/kg); i.c.v. CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + Veh; or i.c.v. CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + AMPH (5 mg/kg). One-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, n = 5–8, mean ± SEM.

(E) SBP (mmHg) in DIO mice treated with i.c.v. Veh and i.p. Veh or AMPH. n = 9, mean ± SEM.

(F) Average SBP (mmHg) over 3 h post i.c.v. Veh and i.p. Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) treatment in DIO mice. ∗p < 0.05, unpaired t test, n = 9, mean ± SEM.

(G) SBP (mmHg) in DIO mice treated with i.c.v. Veh or SB242084 and i.p. Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg). n = 6, mean ± SEM.

(H) Average SBP (mmHg) over 3 h post i.c.v. Veh or SB242084 and i.p. Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) treatment in DIO mice. ∗p < 0.05, unpaired t test, n = 6, mean ± SEM.

(I) SBP (mmHg) in DIO mice treated with i.c.v. Veh or CAR, PHE and i.p. Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg). n = 7–8, mean ± SEM.

(J) Average SBP (mmHg) over 3 h post i.c.v. Veh or CAR, PHE and i.p. Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) treatment in DIO mice. Unpaired t test, n = 7–8, mean ± SEM.

(K) SBP (mmHg) in DIO mice treated with i.c.v. Veh or CAR, PHE, SB242084 and i.p. Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg). n = 4–6, mean ± SEM.

(L) Average SBP (mmHg) over 3 h post i.c.v. Veh or CAR, PHE, SB242084 and i.p. Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) treatment in DIO mice. Unpaired t test, n = 4–6, mean ± SEM.

(M) Heart rate (BPM) in DIO mice treated with i.c.v. Veh or CAR, PHE, SB242084 and i.p. Veh or melanotan II (MTII) (1 mg/kg i.p.). n = 4–6, mean ± SEM (all n are biological replicates).

See also Figure S4.

In DIO mice, AMPH treatment significantly elevated average SBP (146.5 ± 3 mmHg) 3 h post injection compared to Veh treatment (130 ± 6 mmHg) (Figures 5E and 5F). Over the 3 h time period, AMPH-treated DIO mice had significantly higher DBP of 119 ± 3 mmHg compared to 107 ± 4 mmHg in Veh-treated mice (Figure S4B). AMPH + Veh treatment increased HR to 608 ± 5 BPM vs. 569.5 ± 12.9 BPM in Veh + Veh-treated mice (Figure S4C). Veh + AMPH treatment in DIO mice caused a significant rise in locomotor activity, a 3.6-fold increase, compared to Veh + Veh treatment (Figure S4D). When DIO mice were pre-treated with the 5-HT-2C antagonist SB242084, the AMPH-induced increase in SBP was attenuated (140 ± 4 mmHg) compared to Veh + AMPH (146.5 ± 3 mmHg) treatment but was still significantly elevated compared to i.c.v. SB242084 + Veh treatment (126.6 ± 5 mmHg) (Figures 5G and 5H). i.c.v. SB242084 treatment attenuated the Veh + AMPH 119 ± 3 mmHg induced increase in DBP (115 ± 4 mmHg), but no significant difference was observed between and i.p. Veh (106.3 ± 6.5 mmHg) and i.p. AMPH (115 ± 4 mmHg) treatment in the presence of i.c.v. SB242084 (Figure S4E). i.c.v. SB242084 + AMPH treatment (589 ± 17 BPM) caused no significant difference in HR compared to i.c.v. SB242084 + Veh (619 ± 20 BPM) treatment (Figure S4F). i.c.v. SB242084 + AMPH (7 ± 2 arbitrary unit) treatment decreased locomotor activity compared to i.c.v. Veh + AMPH (15 ± 3 arbitrary unit) treatment (Figures S4D and S4G). i.c.v. SB242084 + AMPH (7 ± 2 arbitrary unit) treatment increased locomotor activity compared to i.c.v. SB242084 + Veh (3 ± 0.6 arbitrary unit) treatment, a significantly attenuated increase in locomotor activity compared to Veh + Veh (4.3 ± 2 arbitrary unit) treatment (Figure S4G).

Pre-treatment with CAR and PHE blocked the AMPH-induced increase in SBP (133 ± 4 mmHg vs. 146.5 ± 3 mmHg) and resulted in no difference in SBP compared to CAR, PHE, and Veh control (132 ± 3 mmHg) (Figures 5I and 5J). i.c.v. CAR and PHE + AMPH treatment blocked the AMPH-induced increase in DBP (112 ± 4 mmHg vs. 119± 3 mmHg), and no difference was detected compared to CAR and PHE + Veh (114 ± 3 mmHg) (Figure S4H). No significant difference in HR was recorded between i.c.v. CAR and PHE + AMPH (604 ± 16 BPM) and i.c.v. CAR and PHE + Veh (586.2 ± 13.8 BPM) treatment (Figure S4I). i.c.v. CAR and PHE + AMPH (4 ± 1 arbitrary unit) abolished the increase in locomotor activity induced by Veh + AMPH (15 ± 3 arbitrary unit) (Figure S4J). The combination CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + AMPH (119 ± 2 mmHg) blocked the increase in SBP induced by AMPH (146.5 ± 3 mmHg), and it was not significantly different from the SBP of CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + Veh (126 ± 4 mmHg)-treated mice (Figures 5K and 5L). i.c.v. CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + AMPH (101.2 ± 2 mmHg) prevented AMPH-induced increase in DBP (119 ± 3 mmHg), and no significance difference between CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + Veh (111 ± 3 mmHg) was detected (Figure S4K). Compared to Veh + AMPH (Figures S4C and S4D) treatment, CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + AMPH attenuated the AMPH-induced increase in HR and locomotor activity compared to CAR, PHE, and SB242084 + Veh (Figures S4L and S4M). However, following i.c.v. aCSF + i.p. MTII treatment over a 3 h period, a significant increase in HR was recorded. i.c.v. 5-HT2CR and noradrenergic antagonism in the presence of i.p. MTII caused an increase in HR, unlike the effects of AMPH that were prevented by 5-HT2CR and adrenergic receptor antagonism (Figures 5M and S4N).

Discussion

In humans, AMPH reduces caloric consumption and causes BW loss.1 Although AMPH remains approved for the treatment of obesity, the magnitude of its long-term (>12 months) effects on BW in humans has not been rigorously investigated, unlike the case for more modern anti-obesity drugs. The magnitude of weight loss shown here in chronic experiments in mice is at least comparable to the glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 receptor agonist liraglutide. We have previously shown that 21 days of daily i.p. liraglutide treatment induces 7.5% weight loss in male DIO mice.12 This suggests that the clinical effect of AMPH on BW will be comparable to that of modern drugs approved for obesity and type 2 diabetes. However, in contrast to GLP-1 agonists, AMPH is known to elevate cardiovascular disease risk and the mechanisms involved are not well understood.

FI, locomotor activity, and BW

In studies presented here, AMPH decreased BW via inhibition of FI, elevated BAT thermogenesis (acutely), and increased locomotor activity. Chronic AMPH treatment reduced BW in both DIO and MC4R KO mice, with a greater reduction in DIO mice. The decrease in food inatke (FI) and increase in locomotor activity were major factors causing chronic weight loss. In MC4R KO mice, AMPH treatment increased locomotor activity and decreased FI—albeit to a lesser extent than in DIO mice—contributing to a smaller weight loss observed in MC4R KO mice compared to DIO mice. This demonstrates that a portion of the weight loss induced by AMPH is via melanocortin circuits, but a proportion is independent of the melanocortin system.

Administration of the MC4R/MC3R antagonist SHU 9119 blocked AMPH-increased locomotor activity but did not block AMPH-induced increases in BAT activity. AMPH increased locomotor activity in MC4R KO mice compared to vehicle, which was significantly less than that seen in DIO mice. The difference in response to AMPH seen in MC4R KO mice and SHU 9119-treated DIO mice may be due to SHU 9119 also antagonizing the MC3Rs, which have been shown to increase locomotor activity.13,14

BAT temperature in response to AMPH was less increased in MC4R-deficient mice compared to weight-matched WT mice indicating that part of the thermogenic effects of AMPH are mediated by the central melanocortin system. Mahu et al. have recently demonstrated a robust BAT thermogenic effect with PEGyAMPH that cannot enter the CNS.2 We did not use PEGyAMPH or administer AMPH i.c.v. in these studies, and so we have not addressed whether BAT effects are central or not or both. i.p. injection of SHU 9119 did not block the AMPH-induced increase in BAT temperature, suggesting direct actions of AMPH on BAT, consistent with the findings of Mahu et al.2 Both genetic KO and antagonism of MC4R had virtually identical effects on FI, BW, and cardiovascular tone; however, differences in BAT temperature were observed. It is likely that AMPH increases energy expenditure in humans because weight loss was still observed in early clinical studies when the patients were not able to reduce FI.1

Blood pressure and HR

It is well documented that AMPH acutely increases blood pressure and HR.15 Chronic abuse of AMPH is associated with significantly increased risks of cardiovascular disease including pulmonary hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure5,16,17,18. Here we have found that the melanocortin system appears to mediate a large proportion of the cardiovascular effects of AMPH since the AMPH-induced pressor and tachycardic responses of MC4R KO mice and SHU 9119-treated DIO mice were significantly attenuated.

Our data clearly show that chronic AMPH treatment in MC4R-deficient mice can effectively induce ∼10% weight reduction within 28 days compared to controls without causing adverse cardiovascular outcomes. AMPH may therefore be an effective therapy for obesity in people who have mutations in the MC4R; however, the safety and efficacy of this remain to be determined.

The melanocortin system has been implicated in adverse cardiovascular responses with hypertension being a troubling side effect of melanocortin agonists in development,19,20 although not all MC4R agonists (e.g., BIM-22493/setmelanotide) cause hypertension.21,22 In studies presented here, i.p. SHU 9119 treatment alone decreased SBP and DBP by 35 mmHg and HR by 50 BPM further highlighting the importance of MC4Rs to cardiovascular control. We and others have previously demonstrated that obesity causes an increase in both blood pressure and HR, and in rodents this obesity-induced hypertension and tachycardia are due to increased activation of central leptin receptors in the DMH and this is in part dependent on MC4Rs.23 Here, we show that many of the cardiovascular effects of AMPH are via the melanocortin system. We also show a dramatic increase of c-Fos expression in the DMH of AMPH-treated mice. DMH neurons are known to be a part of the melanocortin system, so AMPH cardiovascular actions could be occurring in the DMH as well as ARH POMC neurons..23,24,25,26

Cellular effects of AMPH

AMPH derivatives have been shown to increase hypothalamic POMC and CART mRNA expression.9,10 In patch-clamp electrophysiology experiments presented here, only 28% of POMC neurons were excited by AMPH, as evidenced by a similar proportion expressing c-fos immunohistochemically. Despite exciting only some POMC neurons, we showed that, in WT, obese MC4R KO, and DIO mice, AMPH significantly increased α-MSH secretion compared to vehicle treatments. Previous research has demonstrated that knockdown of NPY potentiates the FI and BW effects of AMPH as well as increases hypothalamic expression of CART and melanocortin 3 receptors.27 These findings support the hypothesis that AMPH acts on POMC neurons, which are known to regulate FI, BW, BAT thermogenesis, locomotor activity, and the cardiovascular system.

Experiments did not reveal a clear postsynaptic mechanism of AMPH-induced neuronal depolarization indicating that AMPH acts upstream of POMC neurons. Here, increased presynaptic release of 5-HT, noradrenaline, and dopamine could be responsible for changes to POMC neuron membrane activity (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic of AMPH actions and receptor expression on POMC neurons

This schematic describes monoamine receptor expression and a possible pathway through which AMPH modulates the melanocortin system to regulate energy balance and the cardiovascular system.28

5-HT is known to excite POMC neurons via 5-HT2C receptors, and 5-HT2CR agonists such as lorcaserin cause BW loss through reduced FI and increased energy expenditure.7 Lorcaserin actions are dependent on MC4R for acute weight loss actions.29 Increased noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission are known to induce weight loss. Bupropion, a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor, causes modest weight loss.6 Noradrenaline has been shown to inhibit POMC neurons, and we hypothesize that maybe this accounts for the AMPH-inhibited subpopulation of POMC neurons (Figure 6). AMPH may also indirectly excite POMC neurons by increasing 5-HT-dependent inhibition of noradrenergic neurons responsible POMC inhibition.

Transcriptomics

Our data indicate that AMPH affects the melanocortin system by acting upstream of a subpopulation of AMPH-excited POMC neurons. AMPH mechanisms of action are via agonism of TAAR1; inhibition of VMAT 1, VMAT 2, and MAO; and reversal of monoamine transporters. Previous bioinformatic analysis identified three subpopulations of POMC neurons (clusters), being termed n14, n15, and n21.28,30 TAAR1 was not detected in any of the three POMC clusters in the dataset confirming electrophysiology finding and suggesting that AMPH is not acting directly on POMC neurons. Multiple serotonin, adrenergic, and dopaminergic receptor subtypes are expressed on POMC.28 All three POMC clusters express excitatory 5-HT2CR. In in vivo ;experiments here, antagonism of 5-HT2CR caused a significant decrease in AMPH-induced αMSH secretion and attenuated AMPH-induced weight loss and hypophagia, indicating a critical role for 5-HT2CR in AMPH actions.28 POMC cluster 14 neurons express both 3A and 3B subtypes, while cluster n21 POMC neurons express the 3B subtype only.28 Global 5-HT3A KO increases FI and BW, and the 5-HT3 receptor agonist SR-57227 can inhibit FI in mice and prevent fasting-induced increases in hypothalamic POMC gene expression.31,32

Perforated patch-clamp electrophysiology experiments have revealed that noradrenaline (NA) inhibits POMC neurons via α2A adrenoreceptors33 and all three clusters of POMC neurons express inhibitory α2A adrenoreceptors.33 As noradrenaline inhibits POMC neurons, the excitatory noradrenergic receptors do not appear to be activating POMC neurons. 5-HT is inhibitory at noradrenaline neurons, and hence AMPH stimulation of 5-HT neurotransmission may reduce the inhibitory noradrenergic input onto POMC neurons, disinhibiting them and leading to increased αMSH secretion and hence MC4R activation.33,34

Dopamine appears to tonically inhibit D2-expressing POMC neurons in clusters n14 and n21, as AMPH administration in the presence of the D2 antagonist L-741626 caused significant increases in AMPH-induced αMSH secretion and D2 agonists inhibit POMC neurons.35

Like leptin, AMPH causes weight loss in lean mice in contrast to leptin. AMPH still induces anorexia and weight loss in obese mice.36 Leptin directly activates POMC neurons while AMPH appears to act indirectly at POMC neurons, which may account for AMPH still working in obesity.

Limitations of the study

The study did not directly test if the chronic weight loss effects of AMPH were mediated by the serotonergic and adrenergic systems. There may be questions around the specificity of the pharmacological tools to dissect the neurotransmitter systems that could have been addressed using genetic KO models. The transcriptomic data are from the brains of lean mice, and there may be differences in obese mice and in other animals or humans. While the transcriptomic data showed the identity of various receptors that are expressed in the various clusters, it does not quantify the level of protein expression, and so the transcriptomic data can provide a useful guide but cannot predict how the clusters will respond.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that many of the hypophagic, weight, and cardiovascular effects of AMPH are via POMC/MC4R pathways. We also show that there appear to be additional non-melanocortin pathways involved in the overall metabolic and cardiovascular effects of AMPH. 5-HT2C, noradrenergic, and D2 receptors all contribute to the physiological effects of AMPH actions via POMC/MC4R mechanism.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and request for resources and reagents can be directed to the lead contact, Michael A. Cowley (Michael.Cowley@Monash.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate any new reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

All experimental studies generate data. All data reported in this study will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

No new code was generated in this study.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Monash Microimaging for imaging support and funding agencies for support. S.E.S. was supported by the National Heart Foundation of Australia (NHF) (100910) and The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) fellowship (1107336), and M.A.C. was supported by the NHMRC (1163341 and 1176146).

Author contributions

S.E.S., A.L., D.C.S., and M.A.C. designed experiments. S.E.S., J.T.P., T.M., A.M., K.E., E.B., L.O.C., and D.C.S. conducted experiments. S.E.S., J.T.P., B.Y.H.L., G.K.D., T.M., A.M., E.B., and G.S.H.Y. carried out data analysis. G.S.H.Y., A.L., D.C.S., and M.A.C. provided resources and funding. S.E.S., J.T.P., B.Y.H.L., G.S.H.Y., and M.A.C. wrote and edited the article. All authors reviewed the article before publication.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| rabbit polyclonal c-Fos antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-52-G, RRID:AB_2629503 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| D-Amphetamines | Sigma | |

| SB 242084 (50nM) | Tocris | Cat# 2901, CAS 1049747-87-6 |

| Carvedilol (CAR) (Tocris: 50nM | Tocris | Cat# 2685, CAS 72956-09-3 |

| Phentolamine Mesylate (PHE) (Tocris: 1μM | Tocris | Cat# 6431, CAS 65-28-1 |

| SHU.9119 (Tocris: 1nM) (1 mg/kg) (Tocris) | Tocris | Cat# 3420, 168482-23-3 |

| MTII (1 mg/kg) (Bachem) | Bachem | Cat# 4039778.0005 |

| saline (0.9%) | Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd | Cat#AF123 |

| SKF 83566 hydrobromide (10mM), | Tocris bioscience | Cat#1586, CAS 108179-91-5 |

| GR 103691 (50nM) | Tocris bioscience | Cat# 1109, CAS 162408-66-4 |

| L-741626 (50nM) | Tocris bioscience | Cat#1003, CAS 81226-60-0, |

| carprofen (Rimadyl: Zoetrs) | Zoetis Australia Pty Ltd | Cat# 10001132 |

| bupivacaine | Aspen (Mcfarlane and medical scienfic) | Cat# 11006SY |

| Isoflurane | Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd | Cat# AHN3640 |

| NaCl | Sigma | Cat# S7653 |

| KH2PO4 | Sigma | Cat# P5655 |

| KCl | Sigma | Cat# P9327 |

| NaHCO2 | Sigma | Cat# S5761 |

| Glucose | Sigma | Cat# G8270 |

| Mannitol | Analar | Cat# 10330 |

| CaCl2 | Univar | Cat# 16144786 |

| MgCl2 | Analar | Cat# 101149-40 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| αMSH RIA kit | Phoenix Pharmaceutical | Cat# RK-043-01 |

| AGRP RIA kit | Phoenix Pharmaceutical | Cat# RK-003-57 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse (B6; 129S4-Mc4rtm1Lowl/J) (MC4R KO) | Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 032518 RRID IMSR_JAX: 032518 |

| Mouse (C57BL/6J-Tg(Pomc-EGFP)1Low/J) (POMC eGFP) | Jackson Laboratory | Cat#009593 RRID: IMSR_JAX: 009593 |

| Mouse (B6.FVB-Tg(Npy-hrGFP)1Lowl/J) (NPY-R) | Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 006417 RRID IMSR_JAX: 006417 |

| Mouse (C57Bl/6J) | Monash Animal Research Platform | C57BL6JMARP |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism Graph pad 9 | Prism | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| ImageJ | Fiji Image | https://imagej.net/Fiji |

| Figure 6 | BIO Render. | https://www.biorender.com |

| Electrophysiology software | Molecular Devices – pClamp (Clampex & Clampfit) | www.moleculardevices.com |

| Ponemah software | Data Science International | https://www.datasci.com/products/software/ponemah |

| Other | ||

| Cardiovascular radiotelemetry probes | Data Science International | TA11PA-C10 and HD-X11 |

| BAT temperature and locomotor activity radiotelemetry probes | Mini Mitter Company, OR, USA | N/A |

| cannulas (22 gauge, implanted 0.5 mm posterior and 1 mm lateral to bregma, 2 mm depth) | Plastics one cannula | N/A |

| High fat diet (HFD) 36% carbohydrate, 19% protein, 42% fat | Specialty feeds Australia | SF04-001 |

| Chow diet (mouse and rat rodent chow diet, 5% fat) | Specialty feeds Australia | N/A |

| Confocal microscope | Leica | SP8 |

| Vibrating blade microtome | Leica | VTS 1000 |

| Vibratome | Leica | VT1000P |

| Microscope Axioskop | Zeiss | FS2 |

| Axopatch 1D and Multiclamp 700B amplifiers | Molecular devices | N/A |

| Thin-walled borosilicate glass capillaries | Harvard Apparatus | GC150-TF10 |

Experimental model and study participant details

Mice

B6; 129S4-Mc4rtm1Lowl/J mice were obtained from Professor Elmquist.37 POMC eGFP and NPY-R mice were obtained from Professor Malcolm Low and JAX (006417).38 Male C57Bl/6J mice, B6; 129S4-Mc4rtm1Lowl/J (MC4R KO), POMC eGFP and NPY-R mice were fed a chow diet (Specialty feeds Australia, mouse and rat rodent chow diet, 5% fat) ad libitum. To generate diet induced obese (DIO) mouse model, male C57Bl/6J mice were provided a high fat diet (HFD) (Specialty feeds Australia, SF04-001 special diet or equivalent: 36% carbohydrate, 19% protein, 42% fat) ad libitum for 20–32 weeks. Adult mice aged younger than 40 weeks were used in experiments.

Ethics

All animal procedures were approved by the Monash University Animal Ethics Committee.

Habituation

Mice were individually housed to assess daily food intake. They were acclimatized to individual housing for at least 7 days before the start of experiments. Mice were given 7–14 days post-surgery recovery before experimental intervention. The room had a 12:12h light: dark cycle and was maintained at 20°C–23°C with 40–80% humidity. Food and water were always available ad libitum.

Method details

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed by Transnetyx from tail biopsies based on primers previously reported POMC eGFP,38 NPY-R (van den Pol et al., 2009) and MC4R KO (loxTB Mc4r) mice.37

Food intake and body weight measurements

Food intake and bodyweight were measured daily throughout experiments.

Histology

Lean POMC eGFP and NPY-R mice received an IP injection of 5 mg/kg AMPH or Veh. Animals were euthanatized 45mins post injection and cardiac perfusion performed with 4% PFA. Brains were extracted and stored in 4% PFA for 2 h, then transferred to 4% PFA, 20% sucrose and stored at 4°C overnight. Brains were snap frozen and 30μm coronal brain slices were cut on a cryostat. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using primary c-Fos antibody (Santa Cruz; ((4):Sc-52)). Microimaging of the hypothalamus was performed on a confocal microscope (Leica SP8) and cell counting performed using ImageJ software. As we have previously published, quantification of NPY/POMC and cFos were performed on their respective single channel pictures, each positive cell was marked. Then, colocalizations were further quantified by superposing both single channel pictures with their respective marks pasted in and adding a slight transparency factor for visibility.39

Electrophysiology

Ad libitum fed, (>10 weeks of age) lean POMC eGFP mice were anesthetized with 2% (v/v) isoflurane. The brains removed and coronal slices (250 μm) were cut using a vibrating blade microtome (Leica VTS1000) in ice-cold (<4°C) carbogenated (95% O2/5% CO2) aCSF. Once cut, the slices were then heated for 20 min at 34°C and incubated at room temperature prior to recording. The slices were transferred to the recording chamber and were continuously perfused with oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) aCSF. POMC-eGFP neurons in the arcuate nucleus were visualized using an Axioskop FS2 (Zeiss) microscope fitted with DIC optics, infrared microscopy, fluorescence and GFP filter set. Patch pipettes (8–12 MΩ) were pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass capillaries (GC150-TF10 Harvard Apparatus) and filled with intracellular solution. D-Amphetamine was bath-applied to brain slices at 10 μM. Whole cell recordings were made with Axopatch 1D and Multiclamp 700B amplifiers (Molecular Devices LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

ɑMSH and AgRP secretion radioimmunoassay

Was performed to measure the secretion of αMSH and AgRP from hypothalamic of male C57BL6/J and MC4R KO mice. The mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and their brains were immediately removed. A block of the hypothalamus was cut, and a 2mm slice of the mediobasal forebrain was made using a Leica VT1000P vibratome. Each slice was first incubated with aCSF in an incubator (95% O2; 5% CO2) at 37° for 1 h. This was followed by a 45 min incubation in aCSF, then an 45 min incubation in aCSF (control) or aCSF containing 10μM AMPH. Tissue viability was tested with a final 45-min incubation in KCL (56mM). Supernatants were collected and frozen after every incubation stage. The αMSH and AgRP radioimmunoassay were performed according to the instruction of the Phoenix Pharmaceutical’s RIA kits (αMSH, RK-043-01; AGRP, RK-003-57).36,40,41,42

ɑMSH secretion radioimmunoassay with monoamine receptor antagonists

Lean C57Bl6/J mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and brain slices were prepared as described above. After 1h equilibration period in aCSF at 37°, the brain slices were incubated for 45 min with different monoamine receptor antagonists, SB242084 (CAS 1049747-87-6 Tocris bioscience) (50nM), Carvedilol (CAR) (CAS 72956-09-3 Tocris bioscience) (50nM) and Phentolamine mesylate (PHE) (CAS 65-28-1 Tocris bioscience) (1μM), L-741626 (CAS 81226-60-0, Tocris bioscience) (50nM), SKF83566 hydrobromide (CAS 108179-91-5 Tocris bioscience) (10mM), GR103691 (CAS 162408-66-4 Tocris bioscience) (50nM) or aCSF (control) in aCSF. Sliced were further incubated for 45 min in aCSF containing either SB242084 (50nM) + Veh or AMPH (10 μM), CAV (50nM) and PHE (1μM) + Veh or AMPH (10 μM), L-741626 (50nM) + Veh or AMPH (10 μM), SKF83566 hydrobromide (10mM) + Veh or AMPH (10 μM), GR 103691 (50nM) + Veh or AMPH (10 μM). Tissue viability was tested with a final 45-min incubation in KCL (56 mM). supernatants were collected and frozen after each incubation stage for further RIA analysis using phoenix pharmaceutical RIA kit (αMSH, RK-043-01).

Cardiovascular radiotelemetry probe surgery

Under isoflurane anesthesia, cardiovascular radiotelemetry probes (TA11PA-C10 Data Science International) were implanted into the left carotid artery and the transmitter implanted in a skin pouch over the abdomen, as previously described.23,43 All mice received 7–14 days recovery before any baseline recordings were measured.

BAT radiotelemetry probe surgery

Under isoflurane anesthesia, BAT temperature and locomotor activity radiotelemetry probes (Mini Mitter Company, OR, USA) were implanted into the interscapular region between BAT deposits in lean, DIO and MC4R KO mice. All mice received 7–14 days recovery before any baseline recordings were measured.

ICV surgery

Prior to surgery mice were treated with carprofen (Rimadyl: Zoetrs, ip 5 mg/kg) and bupivacaine (Aspen), anesthetized with isoflurane (1–5%) in oxygen (Baxter) and cannulas (Plastics one cannula, 22 gauge, implanted 0.5 mm posterior and 1 mm lateral to bregma, 2 mm depth) were implanted into the lateral ventricle as previously described.23

Physiological effects of daily AMPH dosing for three consecutive days

Lean, DIO and MC4R KO were implanted with BAT temperature probes as previously described.44 Mice received IP injections of either vehicle or AMPH (5 mg/kg) for 3 consecutive days, before the dark period, at 24-h intervals. BAT temperature and locomotor activity was measured at 1-min intervals via telemetry equipment. Food intake and body weight were recorded daily.

Effects of IP AMPH on SBP, DBP and HR in DIO and MC4R KO mice

DIO and MC4R KO mice were implanted with telemetric CV probes as described previously and provided 7–14 days post-operative recovery (13, 15). Mice received IP injections of either Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg), and SBP, DBP, HR and locomotor activity was measured every minute for the duration of experiments.

IP & ICV injections of SHU9119 in DIO mice; effect of central and peripheral MC4R antagonism on food intake, bodyweight, BAT temperature SBP, DBP & HR

DIO mice were implanted with either telemetric CV probes or BAT temperature probes as described previously (13, 15). Half of the mice with CV probes were also implanted with an ICV cannula (outlined above) and provided 7–14-day post-operative recovery. Mice were treated with either ICV or IP injections of veh/SHU9119, followed 15 min later with an IP injection of vehicle/AMPH as follows; Vehicle (ICV) & Vehicle (IP), Vehicle (ICV) & AMPH (IP), SHU 9119 (ICV) & Vehicle (IP), or SHU 9119 (ICV) & AMPH (IP). Vehicle (IP) & Vehicle (IP), Vehicle (IP) & AMPH (IP), SHU 9119 (IP) & Vehicle (IP), or SHU 9119 (IP) & AMPH (IP). BAT temperature, locomotor activity SBP, DBP, HR, were measured every minute for the duration of experiments.

Chronic (28-day) physiological effects of AMPH

DIO and MC4R KO mice were implanted with telemetric CV probes. Following baseline recordings mice received IP injections of either Veh or AMPH (5 mg/kg) daily for 28 days. SBP, DBP, HR and locomotor activity were measured every minute and body weight and food intake were recorded daily.

Blockade of AMPH effects with monoamine receptor antagonists

DIO mice were implanted with CV probes and ICV cannulas (as outlined above). After post-surgery recovery, mice received an ICV injection of vehicle or monoamine receptor antagonist followed by an IP injection of Veh of AMPH 40 min later. Experimental groups were as follows: Veh and Veh, Veh and AMPH, SB242084 and Veh, SB242084 and AMPH, CAR & PHE and Veh, CAR & PHE and AMPH, CAR & PHE & SB242084 and Veh, CAR & PHE & SB242084 and AMPH, CAR & PHE & SB242084 & MTII and Veh, CAR & PHE & SB242084 & Veh and MTII. SBP, DBP, HR and locomotor activity data was collected every minute for 240 min.

Compounds

D-Amphetamine (5 mg/kg) was dissolved in saline (0.9% Baxter) and injected IP in all in vivo experiments. 10μM D-Amphetamine dissolved in aCSF was used for electrophysiology and radioimmunoassay experiments. For ICV injections, SB242084 (Sigma: 50nM), Carvedilol (CAR) (Tocris: 50nM), Phentolamine Mesylate (PHE) (Tocris: 1μM), SHU. 9119 (Tocris: 1nM) were all dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) and 1μL injected. For IP injection, SHU 9119 (1 mg/kg) (Tocris) and MTII (1 mg/kg) (Bachem) were dissolved in 100μL saline.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Figure 1B (n = 4 animals), Figure S1A (n = 4–5 animals), S1C (n = 4 animals) and S1F (n = 4 animals): Comparison of cfos expression between veh and AMPH treatment was performed via a T-test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01. Figure 1E, Comparison of aMSH expression between treatments was conducted using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test (n = 6–19 hypothalamic explants) ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. S1I unpaired T-test, n = 7–8 hypothalamic explanted, ∗p < 0.05. S1H, AgRP expression comparison unpaired ttest, n = 8–11 hypothalamic explants). S1j and S1k n = number of mice per treatment n = 6–13 (S1J) and n = 7–13 (S1k), One Way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Figure 2: Change in food intake and body weight was calculated as the average change compared to the baseline, relative to that observed in mice treated with the vehicle. Brown adipose tissue (BAT) data were collected every minute, and daily averages represent the average of all data collected in a 24-h or 12-h period (light or dark). n = number of mice. per treatment. group, 2a, 2b. 2f, 2g, 2m n-6: 2c, 2h n = 8: 2days, 2n, 2i n = 6–8: 2e n = 5–17: 2j n = 9–21: 2k, 2L n = 4: 2o n = 5–12: S1i n = 7–8, S1J n = 6–13, S1k n = 7–13. two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (2a, b, c, d, f, g, h, i, k, l, m, n), and one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test (2e, o and Figures 1I and 1J). Figure 2J was a comparison from baseline and 24h post treatment and analysis was repeated measures two-way ANOVA (Sidak multiple comparison test). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ++p < 0.01.

Figure 3: n = number of mice. per treatment. group, 3a n = 4–13: 3b-3g n = 6–12: 3h-3m n = 6–7 (a) Locomotor activity values were collected every minute; all values within the 3-h period were included in the analysis, with a one-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple post hoc test. Figures 3C, 3E, and 3G), Figures S2A, S2B, S2E, S2F, S2I, S2J, S2M, and S2N) line graphs, with values plotted every minute. Change graphs Figures 3I, 3K, and 3M), Figure S3A (n = 7–10). depicting the average recorded data from the time of the 2nd injection and the subsequent hour period, analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Figures S2C, S2D, S2G, S2H, S2K, S2L, S2O, and S2P) were unpaired ttest analysis between veh and AMPH. Figures S2A, S2C, S2E, S2G, S2I, S2K, S2M, S2O n = 6; S2B, S2D, S2F, S2H, S2J, S2L, S2N, and S2P n = 11–12. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Figure 4: Line graph displaying average data collected over a 24-h period for blood pressure and activity recording, with data collected every minute and averaged, two-way ANOVA (. Bar graphs 4 (d and f) and Figures S4A representing the average of the 24-h data over the 28-day period when mice were treated with the vehicle or AMPH, analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. n = number of mice. per treatment, 4a-4f and S4A n = 5–7. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Figures S5A–S5D) and Figure S4N, comparisons between groups made using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. Line graphs presenting minute data collected over the 240-min recording period. Bar graphs Figures 5F, 5H, 5J, and 5L) and Figures S4B–S4M) depicting the average data collected for each animal between the injection time and the following 3 h, analyzed with unpaired t-test. Figures 5A and 5B n = number of hypothalamus per treatment; 5a n = 6–21, 5b n = 6–7. n = number of mice. per treatment Figures 5C–5M. 5C, 5days n = 5–8: 5E, 5F, S4B–S4D n = 9: 5G, 5H, S4E, S4F, S4G n = 6: 5I, 5J, S4H–S4J n = 7–8: 5K, 5L, 5M, S4K, S4L, and S4M n = 4–6. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Published: February 5, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.101936.

Contributor Information

Stephanie E. Simonds, Email: stephanie.simonds@monash.edu.

Michael A. Cowley, Email: michael.cowley@monash.edu.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Harris S.C., Ivy A.C., Searle L.M. The mechanism of amphetamine-induced loss of weight; a consideration of the theory of hunger and appetite. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1947;134:1468–1475. doi: 10.1001/jama.1947.02880340022005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahu I., Barateiro A., Rial-Pensado E., Martinez-Sanchez N., Vaz S.H., Cal P., Jenkins B., Rodrigues T., Cordeiro C., Costa M.F., et al. Brain-Sparing Sympathofacilitators Mitigate Obesity without Adverse Cardiovascular Effects. Cell Metabol. 2020;31:1120–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen N. America's first amphetamine epidemic 1929-1971: a quantitative and qualitative retrospective with implications for the present. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2008;98:974–985. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.110593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulzer D., Sonders M.S., Poulsen N.W., Galli A. Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005;75:406–433. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manja V., Nrusimha A., Gao Y., Sheikh A., McGovern M., Heidenreich P.A., Sandhu A.T.S., Asch S. Methamphetamine-associated heart failure: a systematic review of observational studies. Heart. 2023;109:168–177. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2022-321610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billes S.K., Sinnayah P., Cowley M.A. Naltrexone/bupropion for obesity: an investigational combination pharmacotherapy for weight loss. Pharmacol. Res. 2014;84:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heisler L.K., Cowley M.A., Tecott L.H., Fan W., Low M.J., Smart J.L., Rubinstein M., Tatro J.B., Marcus J.N., Holstege H., et al. Activation of central melanocortin pathways by fenfluramine. Science. 2002;297:609–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1072327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan W., Boston B.A., Kesterson R.A., Hruby V.J., Cone R.D. Role of melanocortinergic neurons in feeding and the agouti obesity syndrome. Nature. 1997;385:165–168. doi: 10.1038/385165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh Y.S., Chen P.N., Yu C.H., Chen C.H., Tsai T.T., Kuo D.Y. Involvement of oxidative stress in the regulation of NPY/CART-mediated appetite control in amphetamine-treated rats. Neurotoxicology. 2015;48:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo D.Y., Chen P.N., Yang S.F., Chu S.C., Chen C.H., Kuo M.H., Yu C.H., Hsieh Y.S. Role of reactive oxygen species-related enzymes in neuropeptide y and proopiomelanocortin-mediated appetite control: a study using atypical protein kinase C knockdown. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2011;15:2147–2159. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh Y.S., Yang S.F., Chen P.N., Chu S.C., Chen C.H., Kuo D.Y. Knocking down the transcript of protein kinase C-lambda modulates hypothalamic glutathione peroxidase, melanocortin receptor and neuropeptide Y gene expression in amphetamine-treated rats. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:982–994. doi: 10.1177/0269881110376692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simonds S.E., Pryor J.T., Koegler F.H., Buch-Rasmussen A.S., Kelly L.E., Grove K.L., Cowley M.A. Determining the Effects of Combined Liraglutide and Phentermine on Metabolic Parameters, Blood Pressure, and Heart Rate in Lean and Obese Male Mice. Diabetes. 2019;68:683–695. doi: 10.2337/db18-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pei H., Patterson C.M., Sutton A.K., Burnett K.H., Myers M.G., Jr., Olson D.P. Lateral Hypothalamic Mc3R-Expressing Neurons Modulate Locomotor Activity, Energy Expenditure, and Adiposity in Male Mice. Endocrinology. 2019;160:343–358. doi: 10.1210/en.2018-00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luquet S., Perez F.A., Hnasko T.S., Palmiter R.D. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science. 2005;310:683–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1115524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lile J.A., Babalonis S., Emurian C., Martin C.A., Wermeling D.P., Kelly T.H. Comparison of the Behavioral and Cardiovascular Effects of Intranasal and Oral d-Amphetamine in Healthy Human Subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;51:888–898. doi: 10.1177/0091270010375956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westover A.N., Nakonezny P.A., Haley R.W. Acute myocardial infarction in young adults who abuse amphetamines. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westover A.N., McBride S., Haley R.W. Stroke in young adults who abuse amphetamines or cocaine: a population-based study of hospitalized patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2007;64:495–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zamanian RT H.H., Greuenwald P., Wilson D.M., Segal J.I., Jorden M., Kudelko K., Liu J., Hsi A., Rupp A., Sweatt A.J., et al. Features and Outcomes of Methamphetamine-associated Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017;197:788–800. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201705-0943OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma S., Garfield A.S., Shah B., Kleyn P., Ichetovkin I., Moeller I.H., Mowrey W.R., Van der Ploeg L.H.T. Current Mechanistic and Pharmacodynamic Understanding of Melanocortin-4 Receptor Activation. Molecules. 2019;24 doi: 10.3390/molecules24101892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenfield J.R., Miller J.W., Keogh J.M., Henning E., Satterwhite J.H., Cameron G.S., Astruc B., Mayer J.P., Brage S., See T.C., et al. Modulation of blood pressure by central melanocortinergic pathways. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:44–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kievit P., Halem H., Marks D.L., Dong J.Z., Glavas M.M., Sinnayah P., Pranger L., Cowley M.A., Grove K.L., Culler M.D. Chronic treatment with a melanocortin-4 receptor agonist causes weight loss, reduces insulin resistance, and improves cardiovascular function in diet-induced obese rhesus macaques. Diabetes. 2013;62:490–497. doi: 10.2337/db12-0598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kühnen P., Clement K., Wiegand S., Blankenstein O., Gottesdiener K., Martini L.L., Mai K., Blume-Peytavi U., Gruters A., Krude H. Proopiomelanocortin Deficiency Treated with a Melanocortin-4 Receptor Agonist. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:240–246. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1512693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simonds S.E., Pryor J.T., Ravussin E., Greenway F.L., Dileone R., Allen A.M., Bassi J., Elmquist J.K., Keogh J.M., Henning E., et al. Leptin mediates the increase in blood pressure associated with obesity. Cell. 2014;159:1404–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sevoz-Couche C., Brouillard C., Camus F., Laude D., De Boer S.F., Becker C., Benoliel J.J. Involvement of the dorsomedial hypothalamus and the nucleus tractus solitarii in chronic cardiovascular changes associated with anxiety in rats. J. Physiol. 2013;591:1871–1887. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.247791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garfield A.S., Shah B.P., Burgess C.R., Li M.M., Li C., Steger J.S., Madara J.C., Campbell J.N., Kroeger D., Scammell T.E., et al. Dynamic GABAergic afferent modulation of AgRP neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:1628–1635. doi: 10.1038/nn.4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rau A.R., Hentges S.T. GABAergic Inputs to POMC Neurons Originating from the Dorsomedial Hypothalamus Are Regulated by Energy State. J. Neurosci. 2019;39:6449–6459. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3193-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu S.C., Chen P.N., Ho Y.J., Yu C.H., Hsieh Y.S., Kuo D.Y. Both neuropeptide Y knockdown and Y1 receptor inhibition modulate CART-mediated appetite control. Horm. Behav. 2015;67:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell J.N., Macosko E.Z., Fenselau H., Pers T.H., Lyubetskaya A., Tenen D., Goldman M., Verstegen A.M.J., Resch J.M., McCarroll S.A., et al. A molecular census of arcuate hypothalamus and median eminence cell types. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:484–496. doi: 10.1038/nn.4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner S., Brierley D.I., Leeson-Payne A., Jiang W., Chianese R., Lam B.Y.H., Dowsett G.K.C., Cristiano C., Lyons D., Reimann F., et al. Obesity medication lorcaserin activates brainstem GLP-1 neurons to reduce food intake and augments GLP-1 receptor agonist induced appetite suppression. Mol. Metabol. 2023;68 doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biglari N., Gaziano I., Schumacher J., Radermacher J., Paeger L., Klemm P., Chen W., Corneliussen S., Wunderlich C.M., Sue M., et al. Functionally distinct POMC-expressing neuron subpopulations in hypothalamus revealed by intersectional targeting. Nat. Neurosci. 2021;24:913–929. doi: 10.1038/s41593-021-00854-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li B., Shao D., Luo Y., Wang P., Liu C., Zhang X., Cui R. Role of 5-HT3 receptor on food intake in fed and fasted mice. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smit-Rigter L.A., Wadman W.J., van Hooft J.A. Impaired Social Behavior in 5-HT(3A) Receptor Knockout Mice. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2010;4:169. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paeger L., Karakasilioti I., Altmüller J., Frommolt P., Bruning J., Kloppenburg P. Antagonistic modulation of NPY/AgRP and POMC neurons in the arcuate nucleus by noradrenalin. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.25770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molderings G.J., Frölich D., Likungu J., Göthert M. Inhibition of noradrenaline release via presynaptic 5-HT1D alpha receptors in human atrium. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;353:272–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00168628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X., van den Pol A.N. Hypothalamic arcuate nucleus tyrosine hydroxylase neurons play orexigenic role in energy homeostasis. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:1341–1347. doi: 10.1038/nn.4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enriori P.J., Evans A.E., Sinnayah P., Jobst E.E., Tonelli-Lemos L., Billes S.K., Glavas M.M., Grayson B.E., Perello M., Nillni E.A., et al. Diet-induced obesity causes severe but reversible leptin resistance in arcuate melanocortin neurons. Cell Metab. 2007;5:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balthasar N., Dalgaard L.T., Lee C.E., Yu J., Funahashi H., Williams T., Ferreira M., Tang V., McGovern R.A., Kenny C.D., et al. Divergence of melanocortin pathways in the control of food intake and energy expenditure. Cell. 2005;123:493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cowley M.A., Smart J.L., Rubinstein M., Cerdán M.G., Diano S., Horvath T.L., Cone R.D., Low M.J. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature. 2001;411:480–484. doi: 10.1038/35078085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balland E., Chen W., Tiganis T., Cowley M.A. Persistent Leptin Signaling in the Arcuate Nucleus Impairs Hypothalamic Insulin Signaling and Glucose Homeostasis in Obese Mice. Neuroendocrinology. 2019;109:374–390. doi: 10.1159/000500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koch M., Varela L., Kim J.G., Kim J.D., Hernández-Nuño F., Simonds S.E., Castorena C.M., Vianna C.R., Elmquist J.K., Morozov Y.M., et al. Hypothalamic POMC neurons promote cannabinoid-induced feeding. Nature. 2015;519:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature14260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Batterham R.L., Cowley M.A., Small C.J., Herzog H., Cohen M.A., Dakin C.L., Wren A.M., Brynes A.E., Low M.J., Ghatei M.A., et al. Gut hormone PYY(3-36) physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature. 2002;418:650–654. doi: 10.1038/nature00887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Claret M., Smith M.A., Batterham R.L., Selman C., Choudhury A.I., Fryer L.G.D., Clements M., Al-Qassab H., Heffron H., Xu A.W., et al. AMPK is essential for energy homeostasis regulation and glucose sensing by POMC and AgRP neurons. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:2325–2336. doi: 10.1172/JCI31516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simonds S.E., Pryor J.T., Cowley M.A. Repeated weight cycling in obese mice causes increased appetite and glucose intolerance. Physiol. Behav. 2018;194:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enriori P.J., Sinnayah P., Simonds S.E., Garcia Rudaz C., Cowley M.A. Leptin Action in the Dorsomedial Hypothalamus Increases Sympathetic Tone to Brown Adipose Tissue in Spite of Systemic Leptin Resistance. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:12189–12197. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2336-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All experimental studies generate data. All data reported in this study will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

No new code was generated in this study.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.