Abstract

Three evolutionarily conserved proteins known as SNAREs (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptors) mediate exocytosis from single cell eukaryotes to neurons. Among neuronal SNAREs, syntaxin and SNAP-25 (synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa) reside on the plasma membrane, whereas synaptobrevin resides on synaptic vesicles prior to fusion. The SNARE motifs of the three proteins form a helical bundle which probably drives membrane fusion. Since studies in vivo suggested an importance for multiple SNARE complexes in the fusion process, and models appeared in the literature with large numbers of SNARE bundles executing the fusion process, we analysed the quaternary structure of the full-length native SNARE complexes in detail. By employing a preparative immunoaffinity procedure we isolated all of the SNARE complexes from brain, and have shown by size-exclusion chromatography and negative stain electron microscopy that they exist as approx. 30 nm particles containing, most frequently, 3 or 4 bundles emanating from their centre. Using highly purified, individual, full-length SNAREs we demonstrated that the oligomerization of SNAREs into star-shaped particles with 3 to 4 bundles is an intrinsic property of these proteins and is not dependent on other proteins, as previously hypothesized. The average number of the SNARE bundles in the isolated fusion particles corresponds well with the co-operativity observed in calcium-triggered neuronal exocytosis.

Keywords: membrane fusion, soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor (SNARE), synaptobrevin, synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25), syntaxin

Abbreviations: α-SNAP, α-soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein; SNAP-25, synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa; SNARE, soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor; VAMP2, vesicle-associated membrane protein 2; TMR, transmembrane region

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of the SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor) fusion assembly comprising syntaxin, SNAP-25 (synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa) and synaptobrevin, also known as VAMP2 (vesicle-associated membrane protein 2), provided a fundamental advance in the understanding of vesicle exocytosis [1]. Homologues of neuronal SNAREs have been identified in numerous eukaryotic cells and in many subcellular compartments [2–4]. Both genetic and biochemical studies have confirmed a direct involvement of SNAREs in the membrane fusion process [5–8]. The majority of information about SNARE properties arises from studies of the soluble truncated proteins, but it is becoming clear that the transmembrane domains affect both the structure and the function of SNAREs. Structural studies using soluble fragments of SNAREs demonstrated that they form an approx. 14 nm parallel four-helical bundle [7,9], whereas brain-derived SNARE complexes isolated on an α-SNAP (α-soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein) affinity column appear as a mixture of monomeric and oligomeric bundles [10]. Numerous studies in vivo of the native SNAREs observed oligomeric highmolecular-mass complexes by SDS/PAGE [11–15] and, importantly, neuronal exocytosis was shown to exhibit a SNARE-dependent co-operativity [8]. A number of models of membrane fusion have been proposed where the SNARE proteins form multiple SNAREpins that execute membrane fusion [16–18]. The number of SNARE complexes required for a fusion event was indirectly estimated, through titrating a synaptobrevin/VAMP2 fragment in a cell-based assay, suggesting the co-operation of at least three SNARE complexes in membrane fusion [19]. In a more recent study, mutagenesis of the syntaxin TMR (transmembrane region) affected exocytosis, leading the authors to hypothesize that either 5 or 8 syntaxin molecules may work together in a single vesicle fusion event [20].

Despite persistent indications for the involvement of multiple SNARE complexes in vesicle fusion, a direct quantitative analysis of the number of SNARE bundles participating in the proposed oligomeric assemblies has not been performed to date. If multiple SNARE bundles are necessary for a fusion event it is very likely that the SNAREs are physically linked, for example, through their TMRs [10,21]. Both synaptobrevin and syntaxin TMRs have been shown to interact [21], although synaptobrevin TMR–TMR interactions are still under debate [22,23]. To characterize quantitatively the oligomeric nature of the neuronal SNARE complex we decided to isolate all brain SNARE complexes and to analyse them using transmission electron microscopy [10]. By using an immunoaffinity approach we achieved total extraction of the SNARE ternary complexes, allowing us to draw conclusions on both the magnitude of oligomerization and the number of SNARE bundles in native complexes. We now show that virtually all SNARE complexes isolated from brain appear as oligomeric particles which predominantly contain three to four, but do not exceed six, bundles. Using highly purified individual SNAREs we reconstituted these star-shaped SNARE complexes, with the same number of SNARE bundles as in the native particles, indicating that SNAREs can readily form the oligomeric structures in the absence of any accessory proteins. We propose that the average number of SNARE bundles in the fusion particles may be an essential factor underlying the co-operativity properties observed in calcium-triggered neuronal exocytosis [24].

EXPERIMENTAL

Antibodies

Mouse ascite containing monoclonal antibodies against SNAP-25 (clone SMI 81) was from Sternberger Monoclonals Inc (Lutherville, MD, U.S.A.). Mouse monoclonal antibody against synaptobrevin (clone 69.1) was from Synaptic Systems GmbH (Goettingen, Germany). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against syntaxin 1A and SNAP-25 were produced using GST (glutathione S-transferase)-tagged recombinant syntaxin 1A (residues 1–261) and SNAP-25.

Immunoaffinity purification and size-exclusion chromatography of SNARE proteins

The native SNARE complex was isolated essentially as described previously [25]. All procedures were carried out at 4 °C. Anti-SNAP-25 antibody (1 mg) was purified from 1 ml of ascite fluid on Protein G beads (GE Healthcare) using a low pH elution protocol. Anti-SNAP-25 antibody was covalently coupled to 1 ml of CNBr-activated Sepharose-4B (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mature bovine cerebral cortex (3.5 g; Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, AR, U.S.A.) was homogenized in 50 ml of PBS containing 2 mM EDTA and membrane material collected by centrifugation at 12000 g for 20 min. Pelleted membranes were solubilized in 50 ml of PBS in the presence of 2% (v/v) Thesit and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The lysate was cleared by centrifugation (45 min at 100000 g) and supplemented with NaCl to 0.5 M. Brain protein (250 mg) was batch-incubated with the anti-SNAP-25–Sepharose for 2 h. The gel was then washed in a column with 30 ml of PBS, adjusted to 1 M NaCl, 0.2 mM EGTA and 0.1% Thesit. The 1 M NaCl wash step removes synaptotagmin and complexin, the two accessory proteins co-isolating with the SNAREs [26]. Bound SNARE proteins were eluted with 12 ml of 0.1 M glycine/HCl buffer, pH 2.5, containing 0.25 M NaCl, 0.2 mM EGTA and 0.1% Thesit, and the eluate was immediately neutralized by the addition of Tris/HCl, pH 8.8. Concentrated eluate was applied to a Superose 6 size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 10 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, 0.1 M NaCl and 5 mM dithiotreitol containing a detergent (0.8% β-octylglucoside, 0.1% Thesit and 0.6% CHAPS or 0.1% Triton X-100) and eluted at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Proteins were analysed by SDS/PAGE, and fractions containing all three SNAREs were pooled for further analysis.

Re-assembly of the SNARE complex

Monomeric syntaxin 1, SNAP-25 and synaptobrevin were isolated as described previously [25]. Briefly, the native SNARE complex was disassembled in SDS and individual proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE (12% gel) with preparative electroelution using a MiniPrep Cell (Bio-Rad) at 200 V. The ionic detergent was removed on a Superdex-200 size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 10 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.1 M NaCl and 0.8% (w/v) β-octylglucoside (buffer A). Protein function was confirmed by re-assembly of the SDS-resistant SNARE complex and by synaptotagmin binding [25,26]. The three monomeric SNAREs were mixed at a final concentration of 1 μM in buffer A and incubated at 25 °C for 30 min. Recombinant syntaxin 1A without its TMR (residues 1–261) was produced as described previously [25].

Transmission electron microscopy of SNAREs

Aliquots (4 μl) of the SNARE samples or buffer A were applied to carbon-coated electron microscopy grids that were rendered hydrophilic by glow discharge. Ferritin, used as a standard in negative stain electron microscopy, was from Sigma. The grids were stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate. Electron micrographs were recorded on a Phillips CM12 using low-dose transmission electron microscopy at a primary magnification of 35000 and an accelerating voltage of 120 kV. The resulting micrographs were digitized using a Zeiss SCAI with a 21 μm×21 μm pixel size. Representative particles were selected by hand with no further processing.

RESULTS

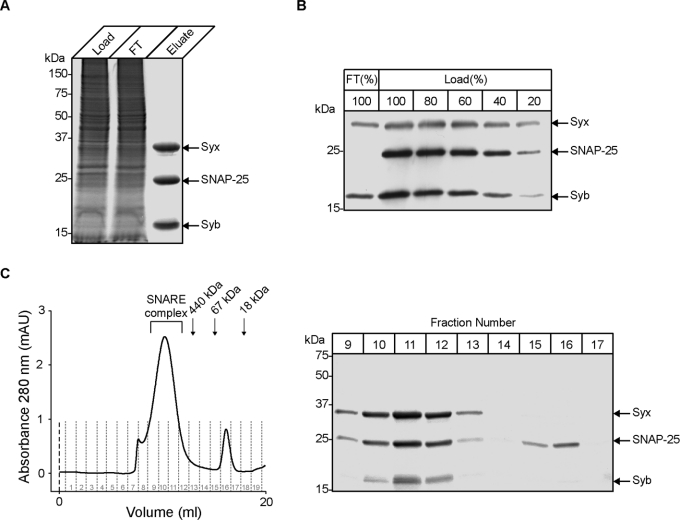

To investigate the native SNARE complex by electron microscopy we isolated it in preparative quantities from bovine brain detergent extract in a single immunoaffinity step. A typical 2-h round of anti-SNAP-25 immunoaffinity chromatography yielded 1 mg of the three SNARE proteins (Figure 1A). To determine the efficiency of the isolation procedure we compared a flow-through sample with a series of dilutions of original loading material. Figure 1(B) shows that the affinity column completely removes SNAP-25 (and thus, all trimeric SNARE complexes) from the loaded material together with 50–60% of syntaxin and synaptobrevin. Following the immunoaffinity step, SNARE complexes were separated from any free SNAP-25 using size-exclusion chromatography in a buffer containing β-octylglucoside (Figure 1C). The three SNARE proteins eluted together in high-molecular-mass fractions preceeding ferritin that has a molecular mass of 440 kDa and, by negative stain electron microscopy, measured approx. 11 nm diameter [27]. The migration of the native SNARE complex ahead of ferritin was identical in four different detergents: 0.8% β-octylglucoside, 0.1% Thesit, 0.6% CHAPS and 0.1% Triton X-100 (results not shown), and provided an indication that all SNARE complexes are likely to possess some supramolecular organization.

Figure 1. Isolated neuronal SNARE complexes migrate in size-exclusion chromatography as high-molecular-mass assemblies.

(A) Isolation of all SNARE complexes on an anti-SNAP-25 immunoaffinity column. Aliquots of bovine brain detergent extract load (Load), flow-through material (FT) and the eluate were analysed by SDS/PAGE and the proteins were revealed by Coomassie Blue stain. (B) Comparison by immunoblotting of the load in indicated dilutions, and the flow-through material indicates full removal of SNAP-25 and 50–60% depletion of syntaxin 1 (Syx) and synaptobrevin (Syb) on the anti-SNAP-25 column. (C) The native SNARE complex migrates with an apparent molecular mass greater than 440 kDa. The anti-SNAP-25 eluate was run on a Superose 6 column and the fractions were analysed by SDS/PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. The chromatogram of the SNARE complex elution on the column also shows the elution positions for the following markers: ferritin (440 kDa), BSA (66 kDa) and myoglobulin (18 kDa).

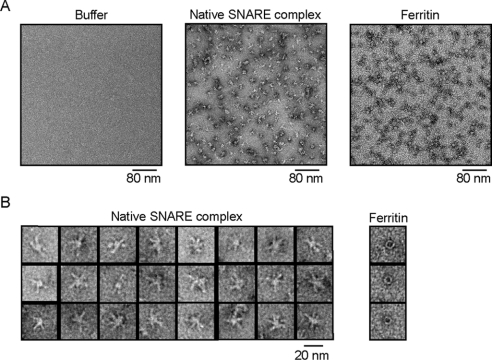

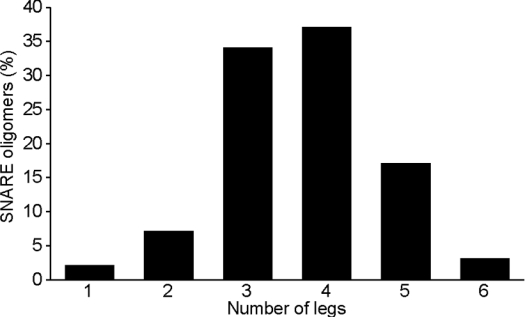

SNARE bundles can be visualized by negative stain transmission electron microscopy [7,10]. Despite the fact that the negatively stained SNAREs have a very low contrast, the field view in the presence of the SNARE complex was littered with approx. 30 nm particles, whereas in a control experiment with the elution buffer alone the grids had a uniform staining (Figure 2A). Transmission electron microscopy of negatively stained ferritin revealed smaller particles compared with the SNARE material. When viewed at higher magnification the SNARE particles are observed as star-shaped assemblies, whereas ferritin appears as a ring (Figure 2B). We quantified the number of legs in the isolated SNARE particles. Between three and five bundles per particle were observed in nearly 90% of particles (n=256), with the most frequent numbers being three and four (Figure 3). The percentage of native particles with a single bundle was very low (2%), contrasting with the SNARE material isolated by an α-SNAP affinity approach [10].

Figure 2. Negative stain electron microscopy of the neuronal SNARE complexes.

(A) Uniformly sized SNARE particles are seen in a survey view by transmission electron microscopy (middle panel), whereas the control grids present a uniform background (left-hand panel). Ferritin at the same magnification is shown for comparison (right-hand panel). (B) Panels showing typical shapes of the approx. 30 nm SNARE particles and approx. 11 nm ferritin.

Figure 3. Quantification of the oligomeric organization of the neuronal SNARE complex.

SNARE particles (n=256) were analysed for the number of legs and the percentage of the particles with a given number of legs is presented. The predominant numbers of SNARE bundles in the neuronal SNARE complex are 3 and 4.

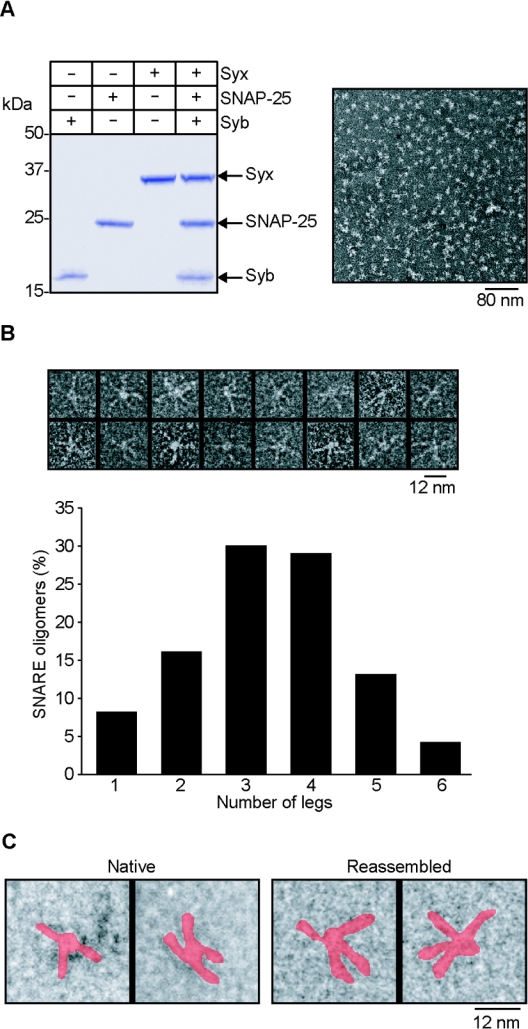

Does oligomerization of SNARE proteins require additional factors? Vesicular synaptotagmin and cytosolic complexin co-purify with the SNAREs [26] and were directly implicated in oligomerization of the SNARE complexes [14,28], but later studies shed doubt on these hypotheses [29,30]. Nevertheless, the oligomeric structure observed for the native SNARE complex could still be a consequence of the previous action of another brain protein. In addition, isolation of native SNARE complex in an oligomeric state could be due to concentration of SNARE bundles in detergent-resistant membrane microdomains. To test whether SNAREs themselves are sufficient to assemble into the star-shaped oligomers we isolated full-length syntaxin, SNAP-25 and synaptobrevin in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of β-octylglucoside detergent and incubated the three individual proteins for 30 min. This revealed that the three SNAREs were able to form the same size particles as observed for the purified complex (Figure 4A). However, individual proteins and the stable syntaxin–SNAP-25 binary assembly in control experiments were beyond the resolution of electron microscopy (results not shown). Quantification of the number of legs per re-assembled SNARE particle showed a non-random distribution with 3–4-spoked structures prevailing (Figure 4B), similar to the native SNARE complexes (Figure 3). Analysis of the shape of individual particles showed a star-shaped appearance for the newly formed SNARE complex, mirroring that of the native SNARE oligomers isolated from brain (Figure 4C). We conclude, therefore, that the SNARE fusion proteins, in the absence of any additional proteins, are capable of spontaneous assembly into the star-shaped oligomers containing most often 3 or 4 SNARE bundles.

Figure 4. Self-assembly of full-length SNARE proteins into star-shaped particles.

(A) A gel showing monomeric syntaxin 1, SNAP-25 and synaptobrevin before and after mixing. The samples were heated prior to analysis by SDS/PAGE and Coomassie staining (left-hand panel). A survey view of the SNARE particles is shown in the right-hand panel. (B) Higher magnification reveals star-shaped oligomers which measure approx. 30 nm. The quantification of the number of legs per star-shaped oligomer is shown (n=216). (C) The re-assembled SNARE particles appear identical to the native SNARE complexes. The SNAREs are false-coloured red.

DISCUSSION

Although the SNARE proteins are now known to be intimately involved in vesicle exocytosis, the precise mechanisms underlying the protein-driven fusion of two opposing membranes are still under investigation. A deeper understanding of intracellular membrane fusion critically depends on a quantitative characterization of the elements driving this process. On the basis of the existence of high-molecular-mass SDS-resistant bands in gel electrophoresis it was hypothesized that SNARE complexes function as oligomers in vivo [11,12,31], and independent theoretical models depicted multiple SNARE bundles driving a singular fusion event [16,18]. Using genetic and electrophysiological approaches, Stewart et al. [8] demonstrated that not only the probability, but also the co-operativity of the calcium-triggered vesicle fusion, exhibits a clear dependence on the number of SNAREs. Since multimerization of SNAREs may be an essential step in vesicle exocytosis, with the number of participating proteins directly determining either the speed of opening or diameter of the fusion pores [20], we sought to quantitatively analyse the brain SNARE complex. Our finding that the majority of the native SNARE particles contain 3 to 4 SNARE bundles is in close agreement with the Hill coefficient observed for calcium-triggered vesicle fusion [8,24]. As we did not observe any particles containing more than 6 bundles it is unlikely that 8 ternary complexes would act together, as has been suggested in previous models [16,18,20].

Hohl et al. [10] observed previously only a proportion of brain-purified SNARE particles with several SNARE bundles which can be decorated by α-SNAP and NSF (N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein); however, the magnitude of oligomerization has not been investigated to date. It is possible that their use of α-SNAP to purify the SNARE complexes led to the enrichment of individual bundles leading the authors to conclude that monomeric SNARE bundles predominate in brain material [10]. Several observations argue against the possibility that the oligomeric appearance of the SNARE bundles is a consequence of protein concentration in detergent micelles. If detergents can indiscriminately concentrate various membrane proteins then one would expect that it would not be possible to isolate pure SNAREs in a single step from the total brain extract. This is clearly not the case and Figure 1 demonstrated a high degree of purity of the SNAREs obtained on the anti-SNAP-25 antibody immunoaffinity column. Furthermore, the non-uniform distribution of the SNARE bundles per SNARE particle is also not consistent with such a possibility (Figures 3 and 4B). Both native and reassembled SNARE complexes behave as high-molecular-mass assemblies in the presence of a 100-fold excess of micellar β-octylglucoside (micelles per bundle ratio). A concentration of bundles in one particular micelle would be thermodynamically unlikely unless formation of oligomeric SNARE particles involves a protein–protein interaction, for example, involving the TMRs. Indeed, interaction of SNARE TMRs has already been demonstrated [21] and can logically account for the observed oligomeric appearance of the SNARE bundles [10]. Our re-assembly experiments using the bacterially expressed syntaxin 1A lacking its TMR led to the formation of irregular aggregates exceeding 80 nm (see Supplementary Figure 1, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/388/bj3880075add.htm), which precluded further quantitative analysis. It is noteworthy that syntaxin lacking its TMR gives rise to a variety of parallel and anti-parallel structures which may explain formation of these erroneous aggregates [32–34].

The aim of the present study was to define the oligomeric states of both the native and the in vitro re-assembled SNARE complexes. The ability of brain-purified SNAREs to form, on their own, star-shaped particles is a novel observation. Our results strongly support a view that full-length SNAREs readily form oligomeric assemblies which may operate in membrane fusion [20], in a similar manner to oligomeric viral fusion proteins [35,36]. In vivo, the ternary SNARE complexes form only upon the approach of vesicles to their target membranes, and it is likely that their oligomeric characteristics are due to pre-organization of SNAREs in the opposing membranes. Since the current technologies can not visualize thin four-helical bundles on or between phospholipid membranes, it will be essential to develop alternative approaches to uncover when and how the SNARE oligomers form, and quantify the number of fusion complexes participating in a single fusion event. It will also be of interest to compare, using the methods described in the present study, SNARE complexes from other eukaryotic sources to understand whether the oligomeric organization of the fusion complex is a common property throughout evolution. Such quantitative studies will undoubtedly bring us a better understanding of the fusion process.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Rosenthal and M. Stowell for advice on electron microscopy.

References

- 1.Sollner T., Whiteheart S. W., Brunner M., Erdjument-Bromage H., Geromanos S., Tempst P., Rothman J. E. SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature (London) 1993;362:318–324. doi: 10.1038/362318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weimbs T., Low S. H., Chapin S. J., Mostov K. E., Bucher P., Hofmann K. A conserved domain is present in different families of vesicular fusion proteins: a new superfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:3046–3051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferro-Novick S., Jahn R. Vesicle fusion from yeast to man. Nature (London) 1994;370:191–193. doi: 10.1038/370191a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wendler F., Page L., Urbe S., Tooze S. A. Homotypic fusion of immature secretory granules during maturation requires syntaxin 6. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:1699–1709. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szule J. A., Coorssen J. R. Revisiting the role of SNAREs in exocytosis and membrane fusion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1641:121–135. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jahn R., Lang T., Sudhof T. C. Membrane fusion. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2003;112:519–533. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz L., Hanson P. I., Heuser J. E., Brennwald P. Genetic and morphological analyses reveal a critical interaction between the C-termini of two SNARE proteins and a parallel four helical arrangement for the exocytic SNARE complex. EMBO J. 1998;17:6200–6209. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart B. A., Mohtashami M., Trimble W. S., Boulianne G. L. SNARE proteins contribute to calcium cooperativity of synaptic transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:13955–13960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250491397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutton R. B., Fasshauer D., Jahn R., Brunger A. T. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature (London) 1998;395:347–353. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hohl T. M., Parlati F., Wimmer C., Rothman J. E., Sollner T. H., Engelhardt H. Arrangement of subunits in 20 S particles consisting of NSF, SNAPs, and SNARE complexes. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:539–548. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leveque C., Boudier J. A., Takahashi M., Seagar M. Calcium-dependent dissociation of synaptotagmin from synaptic SNARE complexes. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:367–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence G. W., Dolly J. O. Multiple forms of SNARE complexes in exocytosis from chromaffin cells: effects of Ca2+, MgATP and botulinum toxin type A. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:667–673. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Connor V., Heuss C., De Bello W. M., Dresbach T., Charlton M. P., Hunt J. H., Pellegrini L. L., Hodel A., Burger M. M., Betz H., et al. Disruption of syntaxin-mediated protein interactions blocks neurotransmitter secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:12186–12191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokumaru H., Umayahara K., Pellegrini L. L., Ishizuka T., Saisu H., Betz H., Augustine G. J., Abe T. SNARE complex oligomerization by synaphin/complexin is essential for synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2001;104:421–432. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao S. S., Stewart B. A., Rivlin P. K., Vilinsky I., Watson B. O., Lang C., Boulianne G., Salpeter M. M., Deitcher D. L. Two distinct effects on neurotransmission in a temperature-sensitive SNAP-25 mutant. EMBO J. 2001;20:6761–6771. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber T., Zemelman B. V., McNew J. A., Westermann B., Gmachl M., Parlati F., Sollner T. H., Rothman J. E. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho S. J., Kelly M., Rognlien K. T., Cho J. A., Horber J. K., Jena B. P. SNAREs in opposing bilayers interact in a circular array to form conducting pores. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2522–2527. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jahn R., Grubmuller H. Membrane fusion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:488–495. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hua Y., Scheller R. H. Three SNARE complexes cooperate to mediate membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:8065–8070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131214798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han X., Wang C. T., Bai J., Chapman E. R., Jackson M. B. Transmembrane segments of syntaxin line the fusion pore of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Science (Washington, D.C.) 2004;304:289–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1095801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laage R., Rohde J., Brosig B., Langosch D. A conserved membrane-spanning amino acid motif drives homomeric and supports heteromeric assembly of presynaptic SNARE proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17481–17487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910092199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowen M. E., Engelman D. M., Brunger A. T. Mutational analysis of synaptobrevin transmembrane domain oligomerization. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15861–15866. doi: 10.1021/bi0269411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy R., Laage R., Langosch D. Synaptobrevin transmembrane domain dimerization – revisited. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4964–4970. doi: 10.1021/bi0362875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodge F. A., Jr, Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action a calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. J. Physiol. 1967;193:419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu K., Carroll J., Fedorovich S., Rickman C., Sukhodub A., Davletov B. Vesicular restriction of synaptobrevin suggests a role for calcium in membrane fusion. Nature (London) 2002;415:646–650. doi: 10.1038/415646a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rickman C., Davletov B. Mechanism of calcium-independent synaptotagmin binding to target SNAREs. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:5501–5504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ainsworth S. K., Karnovsky M. J. An ultrastructural staining method for enhancing the size and electron opacity of ferritin in thin sections. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1972;20:225–229. doi: 10.1177/20.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Littleton J. T., Bai J., Vyas B., Desai R., Baltus A. E., Garment M. B., Carlson S. D., Ganetzky B., Chapman E. R. Synaptotagmin mutants reveal essential functions for the C2B domain in Ca2+-triggered fusion and recycling of synaptic vesicles in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1421–1433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01421.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ubach J., Lao Y., Fernandez I., Arac D., Sudhof T. C., Rizo J. The C2B domain of synaptotagmin I is a Ca2+-binding module. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5854–5860. doi: 10.1021/bi010340c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pabst S., Margittai M., Vainius D., Langen R., Jahn R., Fasshauer D. Rapid and selective binding to the synaptic SNARE complex suggests a modulatory role of complexins in neuroexocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:7838–7848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pellegrini L. L., O'Connor V., Lottspeich F., Betz H. Clostridial neurotoxins compromise the stability of a low energy SNARE complex mediating NSF activation of synaptic vesicle fusion. EMBO J. 1995;14:4705–4713. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weninger K., Bowen M. E., Chu S., Brunger A. T. Single-molecule studies of SNARE complex assembly reveal parallel and antiparallel configurations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:14800–14805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misura K. M., Scheller R. H., Weis W. I. Self-association of the H3 region of syntaxin 1A. Implications for intermediates in SNARE complex assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:13273–13282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misura K. M., Gonzalez L. C., Jr, May A. P., Scheller R. H., Weis W. I. Crystal structure and biophysical properties of a complex between the N-terminal SNARE region of SNAP25 and syntaxin 1a. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:41301–41309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danieli T., Pelletier S. L., Henis Y. I., White J. M. Membrane fusion mediated by the influenza virus hemagglutinin requires the concerted action of at least three hemagglutinin trimers. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:559–569. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.3.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell R., Paterson R. G., Lamb R. A. Studies with cross-linking reagents on the oligomeric form of the paramyxovirus fusion protein. Virology. 1994;199:160–168. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.