Abstract

Background

This study aimed to assess whether a driving pressure-limiting strategy based on positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) titration according to best respiratory system compliance and tidal volume adjustment increases the number of ventilator-free days within 28 days in patients with moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Methods

This is a multi-centre, randomised trial, enrolling adults with moderate to severe ARDS secondary to community-acquired pneumonia. Patients were randomised to a driving pressure-limiting strategy or low PEEP strategy based on a PEEP:FiO2 table. All patients received volume assist-control mode until day 3 or when considered ready for spontaneous modes of ventilation. The primary outcome was ventilator-free days within 28 days. Secondary outcomes were in-hospital and intensive care unit mortality at 90 days.

Results

The trial was stopped because of recruitment fatigue after 214 patients were randomised. In total, 198 patients (n=96 intervention group, n=102 control group) were available for analysis (median age 63 yr, [interquartile range 47–73 yr]; 36% were women). The mean difference in driving pressure up to day 3 between the intervention and control groups was –0.7 cm H2O (95% confidence interval –1.4 to –0.1 cm H2O). Mean ventilator-free days were 6 (sd 9) in the driving pressure-limiting strategy group and 7 (9) in the control group (proportional odds ratio 0.72, 95% confidence interval 0.39–1.32; P=0.28). There were no significant differences regarding secondary outcomes.

Conclusions

In patients with moderate to severe ARDS secondary to community-acquired pneumonia, a driving pressure-limiting strategy did not increase the number of ventilator-free days compared with a standard low PEEP strategy within 28 days.

Clinical trial registration

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, driving pressure, positive end-expiratory pressure, tidal volume, ventilator-induced lung injury

Editor's key points.

-

•

There is continued interest in ventilation strategies that can improve outcomes for patients with ARDS.

-

•

Controlling and reducing ventilator driving pressure is a particular focus of current treatment strategies.

-

•

In this trial, titration of PEEP according to respiratory compliance did not achieve a reduction in driving pressure or in ventilator-free days.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) accounts for 10% of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and is associated with a high mortality rate.1,2 ARDS is characterised by reduction of lung aeration resulting from collapsed, flooded, or consolidated lung units.3 The cornerstone treatment for ventilated ARDS patients is the use of lung-protective mechanical ventilation to minimise ventilator-induced lung injury.4 Over the last decade, driving pressure, calculated as the difference between plateau pressure and positive-end expiratory pressure (PEEP), has been suggested to be associated with pulmonary injury and mortality irrespective of PEEP, tidal volume, or plateau pressure.1,5 Although driving pressure remains a primary consideration, limiting plateau pressure also contributes to a lower probability of lung injury.6

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is the most common cause of ARDS.7 It is debatable whether pulmonary ARDS causes, including pneumonia, have distinct physiologic behaviour when compared with extrapulmonary ARDS.8 Indeed, it has been suggested that lung elastance tends to be higher in pulmonary ARDS,9 which could lead to differences in response to changes in PEEP,8 and that aggressive PEEP titration manoeuvres with alveolar recruitment could be harmful in patients with pneumonia and shock.10 Therefore, investigations that included both pulmonary and extrapulmonary ARDS causes could potentially fail to show any benefit given the expected different responses to treatment among those groups. The landscape of our understanding of PEEP changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, with early reports suggesting that COVID-19 patients, which are patients with ARDS secondary to CAP, could potentially benefit from higher levels of PEEP,11 and others suggesting that high PEEP levels would be potentially harmful.12 Therefore, the question of whether different PEEP approaches could be useful in patients with ARDS secondary to pneumonia is not totally established, and it is also unclear if COVID-19 patients would benefit from it. In this sense, a trial focusing on different ventilatory strategies in the population of CAP patients was warranted.

In addition, considering the broad ARDS picture, only a few randomised clinical trials assessed the feasibility of mechanical ventilation with driving pressure control in patients with ARDS.13,14 Although the reduction in driving pressure was primarily achieved by decreasing tidal volume, PEEP titration could potentially modify driving pressure through an increase in lung compliance obtained with lung recruitment.15 This hypothesis, however, has not yet been assessed in larger studies. It is therefore conceivable that strategies that optimise PEEP according to lung mechanics while also controlling driving pressure could result in meaningful benefits for patients with ARDS secondary to CAP.

The Ventilator Strategy for Community Acquired Pneumonia (STAMINA) study was conducted to compare a driving pressure-limiting strategy to a standard low PEEP strategy in patients with moderate to severe ARDS resulting from CAP, aiming to increase ventilator-free days in 28 days.16

Methods

Study design and overview

This was an investigator-initiated, multicentre, randomised, open-label clinical trial conducted at 29 ICUs in two countries (Brazil and Colombia). The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan have been published10 (Supplementary material S1 and S2). The trial was designed and overseen by a steering committee. An independent external data monitoring committee monitored the trial and reviewed two planned interim analyses when 100 and 200 patients had complete data on primary and safety outcomes (Supplementary material S3). Ethical approval was obtained at all enrolling sites. All patients or their legally authorised representatives provided informed consent. Patients could be included before the informed consent was signed by the patient's legal representative (deferred consent). Details are provided in Supplementary material S3. This trial is reported according to the CONSORT 2010 statement.17

Patients

We enrolled patients aged 18 yr or older who were admitted to the ICU with CAP receiving invasive mechanical ventilation who met ARDS criteria according to the Berlin definition18 and satisfied at least one of the following criteria: (1) FiO2 above 50% with PEEP ≥ 8 cm H2O to maintain peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) above 93% or (2) :FiO2 ratio <200 with PEEP >5 cm H2O. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are fully defined in Supplementary material S3.

Randomisation and masking

Trial participants were randomised in a 1:1 ratio for a driving pressure-limiting strategy (STAMINA strategy) or a low PEEP strategy based on the ARDSNet trial16 through a central, online web-based automated randomisation system available 24 h. The random allocation list was generated by an independent statistician using a computer-generated number list. Randomisation was performed using variable block sizes stratified by centre and COVID-19 diagnosis. Information about the assigned study group was revealed only after the registration of each patient in the web-based randomisation system. Participants, clinicians, and outcome assessors were aware of the assigned treatment.

Interventions

The study protocol was conducted from day 0 (randomisation) through day 3 in all eligible patients. The ventilator procedures are summarised in Supplementary Table S1 from Supplementary material S3. The intervention strategy consisted of a driving pressure-limiting strategy based on PEEP titration according to best respiratory system compliance and tidal volume adjustment at least once a day in the first 3 days. The titration of PEEP was performed after a protective ventilation strategy based on a tidal volume of 6 ml kg−1 of predicted body weight and plateau pressure equal to or lower than 30 cm H2O was implemented and followed a specific protocol.6 First, an incremental phase was performed where PEEP was increased by 2 cm H2O every minute up to 20 cm H2O. The manoeuvre interruption was performed according to specified criteria if peak airway pressure was equal to or higher than 40 cm H2O, plateau pressure was above 33 cm H2O, or haemodynamic instability (defined by new-onset arrhythmia or increase in vasopressor dose of more than 20 μg min−1 of norepinephrine equivalents) occurred (Supplementary Table S1). Then, a decremental phase started, where PEEP was reduced by 2 cm H2O every minute until 8 cm H2O; compliance was measured at each PEEP level (Supplementary Fig. S1 from Supplementary material S3). The titrated PEEP was the value immediately before a drop in compliance of 2 ml (cm H2O)−1 or more in one decremental step or a drop of 1 ml (cm H2O)−1 in two consecutive steps (Supplementary Table S1). After titrating PEEP, reductions in tidal volume down to 4 ml kg−1 could be made to achieve a driving pressure ≤14 cm H2O and a plateau pressure ≤30 cm H2O. If these target mechanical parameters were not reached, PEEP could be reduced by 2 cm H2O to achieve that objective (Supplementary Fig. S2 from Supplementary material S3).

The low PEEP strategy consisted of PEEP and FiO2 adjustments according to the low PEEP:FiO2 table16 (Supplementary Table S1 from Supplementary material S3) to maintain SpO2 between 90% and 94% or ≥7.9 kPa (control group). Subsequently, tidal volume and PEEP could be reduced to keep plateau pressure equal to or lower than 30 cm H2O, regardless of driving pressure (Supplementary Figs S3–S5 from Supplementary material S3).

Data reported

Baseline parameters, blood gas analysis, and adherence to protocol data from day 0 through day 3 are detailed in Supplementary material S3. Day 0 refers to the initial day on which the patient was enrolled in the study and underwent the first PEEP titration.

Adherence to study interventions

The protocol adherence was assessed on day 0 (right after PEEP titration and then at 8, 16, and 24 h) and then daily on days 1, 2, and 3. Adherence definition included the occurrence of PEEP titration manoeuvres, limiting driving pressure in the intervention group, and proper match between PEEP and FiO2 in the control group. Adherence to limited values of tidal volume and plateau pressure were common in both groups (Supplementary material S3).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was ventilator-free days during the first 28 days or until hospital discharge, whichever occurred earlier, defined as the number of days alive and free from mechanical ventilation in 28 days. For patients who died within 28 days, the number of ventilator-free days was assigned as zero. More details on the definitions are provided in Supplementary Table S2 from Supplementary material S3. Secondary outcomes were in-hospital and ICU mortality, and the need for rescue therapies (nitric oxide, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or recruitment manoeuvres) within 28 days. Safety outcomes included the occurrence of barotrauma and any other serious adverse events possibly related to mechanical ventilation (presence of subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, or pneumomediastinum) within 28 days (Supplementary Table S2 from Supplementary material S3). Tertiary outcomes included the following: (1) oxygenation, measured by the :FiO2 ratio during the first 3 days; (2) driving pressure, ventilatory ratio, oxygenation index, and mechanical power measured in the first 3 days; (3) ICU-free days in 28 days; and (4) ICU and hospital length of stay (Supplementary Table S2 from Supplementary material S3).

Power analysis and sample size calculation

Power estimates were obtained from simulations with 2000 iterations. We considered raw data from the CoDEX study19 to estimate ventilation-free days in 28 days in the control group. Assuming a mean of 4.7 (interquartile range [IQR] 3.7–5.8; standard deviation [sd] 8.2) mechanical ventilation-free days in 28 days for the control group and a mean of 7.8 (IQR 6.5–9.2; sd 10.5) mechanical ventilation-free days for the intervention group, 500 patients would be necessary for a power of at least 90%. The cumulative distribution for the primary outcome from a simulation considering the null model (with the effect of the intervention group identical to that of the control group) is shown in Supplementary Figure S6 from Supplementary material S3.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed according to a modified intention-to-treat principle, excluding patients who refused consent and those randomised but not fulfilling eligibility. A mixed ordinal model, adjusted for baseline age, COVID-19 diagnosis, baseline ventilatory ratio, and PEEP, with the site as a random intercept, evaluated the effect of the driving pressure-limiting strategy vs low PEEP strategy on the primary outcome. Results were reported as proportional odds ratios (ORps) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). ORp >1 indicates higher odds of more ventilator-free days for the intervention group compared with the control group. Mean difference and 95% CIs of ventilator-free days between groups were also reported using a zero-inflated beta-binomial model.

For binary secondary outcomes, comparisons were made using odds ratios and 95% CIs. For continuous outcomes, gamma distribution was used to estimate the differences in responses and 95% CIs. Models were adjusted for the same variables above and considered the site a random intercept.

The daily evolution of mechanical ventilation and arterial blood gas parameters were compared using gamma distribution and considering the interaction between group and intervention day and patient as a random intercept to estimate the difference in response and 95% CI.

The intervention's effect on the primary outcome in prespecified subgroups (COVID-19 diagnosis and driving pressure above or below 15 cm H2O) was evaluated using the same model, with added interaction terms. A post hoc subgroup analysis based on ARDS severity was conducted, without considering the site as a random intercept.

All the analyses were performed with R software version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. P-values and CIs were not adjusted for multiplicity, so secondary and tertiary outcomes and subgroups analyses should be interpreted as exploratory.

Results

Patients

The study was terminated before its planned sample size by the steering committee based on a sustained decrease in participants' recruitment rate (Supplementary Fig. S7 from Supplementary material S3) and the input from the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, after the second interim analysis with 196 patients, that the between-group gradient in driving pressure was clinically insignificant. Considering the trial hypothesis that a decrease in driving pressure would result in improved clinical outcomes, a small driving pressure gradient was unlikely to result in substantial changes in clinical outcomes. Between September 4, 2021, and November 11, 2023, a total of 431 patients underwent eligibility screening at 29 ICUs. A total of 217 patients were excluded, and 214 patients were randomised. Sixteen patients were excluded from the analysis (11 refused to provide consent after recovery, and five did not meet all eligibility criteria; Fig. 1). There were no losses to follow up. The final analysis included data from 198 patients, with 96 patients allocated to the intervention group and 102 patients allocated to the control group (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Enrolment, randomisation, and follow-up of the study participants. The screening process, selection, and flow of patients through the trial are presented. Patients or next of kin were asked to provide consent after randomisation. The reason for the post-randomisation exclusions was the death of the participants before their next of kin could provide consent, combined with the lack of authorisation from the ethics committee to include data from these patients. Patients can have more than one reason for exclusion from the trial.

Patient features at baseline are presented in Table 1. The median age was 63 [IQR 47–73] yr, 36% were women, and 60% had pneumonia resulting from COVID-19 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants. FiO2, oxygen inspiratory fraction; IQR, interquartile range; , arterial partial carbon dioxide pressure; :FiO2, arterial partial oxygen pressure divided by oxygen inspiratory fraction; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

| Drivingpressure-limitingwith PEEP titrationgroup (n=96) | Low PEEPgroup(n=102) | Overall (n=198) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 66 (50–73) | 61 (42–73) | 63 (47–73) |

| Women (sex at birth), n (%) | 35 (36) | 37 (36) | 72 (36) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 53(55) | 45 (44) | 98 (49) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31 (32) | 24 (24) | 55 (28) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 15 (16) | 17 (17) | 32 (16) |

| Heart failure | 15 (16) | 11 (11) | 26 (13) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (9) | 13 (13) | 22 (11) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 11 (11) | 8 (8) | 19 (10) |

| Haematological malignancies or solid tumour | 8 (8) | 12 (12) | 20 (10) |

| Transient ischaemic attack or stroke(with or without neurologic deficit) | 9 (9) | 8 (8) | 17 (9) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 7 (7) | 4 (4) | 11 (6) |

| Modified Frailty Index score, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) |

| Status—COVID-19, n (%) | |||

| Pneumonia COVID-19 | 58 (60) | 61 (60) | 119 (60) |

| Pneumonia non-COVID-19 | 38 (40) | 41 (40) | 79 (40) |

| Ventilatory support, median (IQR) | |||

| Days of mechanical ventilation beforerandomisation | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) |

| Tidal volume/predicted body weight (ml kg−1) | 6 (6–6) | 6 (6–6) | 6 (6–6) |

| Positive end-expiratory pressure (cm H2O) | 10 (8–10) | 10 (8–12) | 10 (8–12) |

| FiO2 (%) | 70 (59–100) | 60 (51–90) | 70 (55–94) |

| Respiratory rate (bpm) | 27 (24–30) | 28 (24–30) | 28 (24–30) |

| Plateau airway pressure (cm H2O) | 23 (21–25) (n=92) | 24 (21–26) (n=97) | 23 (21–26) (n=189) |

| Respiratory system static compliance(ml (cm H2O)−1) | 28 (22–37) (n=92) | 27 (22–34) (n=97) | 28 (22–36) (n=189) |

| Driving pressure (cm H2O) | 13 (11–15) (n=92) | 13 (11–16) (n=97) | 13 (11–16) (n=189) |

| Minute ventilation (L min−1) | 10 (8–11) | 10 (8–11) | 10 (8–11) |

| Arterial blood gases, median (IQR) (n) | |||

| pH | 7.28 (7.19–7.32) (n=96) | 7.27 (7.19–7.37) (n=102) | 7.27 (7.19–7.35) (n=198) |

| (kPa) | 11.1 (9.5–14) | 11.5 (9.8–15) | 11.3 (9.5–14.8) |

| (kPa) | 6.3 (5.4–8.0) | 7.0 (5.8–8.4) | 6.6 (5.5–8.1) |

| Bicarbonate (mM) | 22 (19–26) | 24 (20–29) | 23 (20–28) |

| SaO2 (%) | 94 (91–97) | 95 (91–98) | 95 (91–97) |

| :FiO2 | 136 (95–171) | 141 (98–182) (n=102) | 139 (96–175) (n=198) |

| Prone position, n/N (%) | 18/96 (19) | 15/102 (15) | 33/198 (17) |

| Vasoactive drugs use, n (%) | |||

| Norepinephrine | 72 (75) | 70 (69) | 142 (72) |

| Epinephrine | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) |

| Vasopressin | 8 (8) | 7 (7) | 15 (8) |

| Laboratory tests, median (IQR) (n) | |||

| Creatinine (mg dl−1) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) (n=96) | 1.2 (0.7–1.7) (n=100) | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) (n=196) |

| Total bilirubin (mg dl−1) | 0.6 (0.36–1.11) (n=58) | 0.6 (0.36–0.87) (n=59) | 0.6 (0.36–0.92) (n=117) |

| Platelets (103 mm−3) | 209 (169–268) (n=95) | 218 (156–288) (n=101) | 214 (159–278) (n=196) |

Interventions

All patients in the intervention group with no contraindications for the PEEP titration manoeuvre were submitted to at least one manoeuvre per 24-h period from day 0 through day 3 (Supplementary Table S3 from Supplementary material S3). The maximum PEEP of 20 cm H2O was reached in only 34.6% of the attempts. Most interruptions were attributed to elevated plateau or peak pressure. The mean titrated PEEP in the intervention group was 9 (sd 2) cm H2O. Adherence to the low PEEP table was high (96.2% overall), and the mean titrated PEEP was 9.3 (2.6) cm H2O (Supplementary Table S4 from Supplementary material S3). The distribution of ventilatory parameters in both groups is shown in (Supplementary Figs S8–S10 from Supplementary material S3).

Driving pressure and other respiratory variables

The difference in driving pressure between the driving pressure-limiting group and the standard low PEEP group from day 0 through day 3 was –0.7 cm H2O (95% CI –1.4 to –0.1 cm H2O) (Supplementary Table S5 and Figs S11 and S12 from Supplementary material S3). Mean tidal volume was lower (–0.20 ml, 95% CI –0.30 to –0.04 ml), and respiratory rate was higher (mean difference 1.19 bpm; 95% CI 0.2–2.17 bpm) in the intervention group from day 0 through day 3 (Supplementary Table S5 and Fig. S11 from Supplementary material S3). Plateau pressure, mechanical power, respiratory system compliance, PEEP, and blood gas parameters were similar for both groups (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6 and Fig. S11 from Supplementary material S3).

Primary outcome

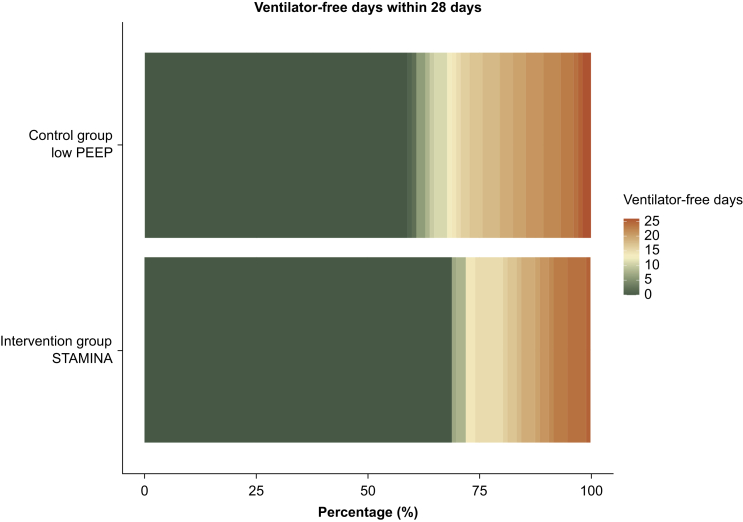

There was no significant difference in ventilator-free days within 28 days between groups: mean of 6 (9) in the intervention group vs 7 (9) days in the control group; ORp of 0.72 (95% CI 0.39–1.32; P=0.28) with a marginal effect of adjusted difference of –1.28 (95% CI –3.60 to 1.26) days (Table 2, Fig 2, Fig 3, and Supplementary Figs S12 and S13 from Supplementary material S3). There were no signs of modification of treatment effect in the predefined subgroups of patients defined by the diagnosis of COVID-19 (P=0.46), baseline driving pressure (P=0.14), or ARDS severity (P=0.93) (Supplementary Table S7 and Fig. S14 from Supplementary material S3). Post hoc subgroup analysis defining ARDS severity (/FiO2 ≤150 mm Hg) also showed no difference.

Table 2.

Outcomes among patients treated with driving pressure-limiting strategy vs low PEEP strategy. CI, confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IQR, interquartile range; MD, mean difference; OR, odds ratio; ORp, proportional odds ratio; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure. ∗ORp from ordinal model adjusted for age, COVID-19 diagnosis, baseline ventilatory rate, and PEEP at randomisation. †MD: zero-inflated beta-binomial model adjusted for age, COVID-19 diagnosis, baseline ventilatory rate, and PEEP at randomisation. ‡OR: logistic mixed-effects model adjusted for age, COVID-19 diagnosis, baseline ventilatory rate, and PEEP at randomisation. ¶One patient from the low PEEP group underwent this rescue therapy three times; two patients from the low PEEP group and one patient from the intervention group were subjected to this rescue therapy twice. §MD: generalised linear mixed-effects model with Gamma distribution adjusted for age, COVID-19 diagnosis, baseline ventilatory rate, and PEEP at randomisation.

| Outcome | Driving pressure-limitingwith PEEP titrationgroup (n=96) | Low PEEPgroup(n=102) | Effectestimate | Effect estimate(95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Ventilator-free days in 28 days | |||||

| Mean (sd) | 6 (9) | 7 (9) | ORp∗ | 0.72 (0.39–1.32) | 0.28 |

| MD† | –1.28 (–3.60 to 1.26) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0–15) | 0 (0–17) | |||

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Death, n events/n total (%) | |||||

| In the intensive care unit | 63/96 (66) | 54/102 (53) | OR‡ | 1.66 (0.87–3.17) | 0.13 |

| In the hospital | 63/96 (66) | 56/102 (55) | OR | 1.48 (0.77–2.85) | 0.24 |

| Rescue therapies, n (%) | |||||

| ECMO | 0/96 (0) | 0/102 (0) | – | – | – |

| Recruitment manoeuvre(outside protocol)¶ | 2/96 (2) | 4/102 (4) | OR | 0.52 (0.09–3.13) | 0.48 |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | 1/96 (1) | 1/102 (1) | OR | 1.09 (0.04–27.13) | 0.96 |

| Safety outcome | |||||

| Barotrauma, n (%) | 4/96 (4) | 3/102 (3) | OR | 1.35 (0.28–6.55) | 0.71 |

| Tertiary outcomes | |||||

| Length of stay (days) | |||||

| In the intensive care unit | |||||

| Mean (sd) | 17 (16) | 17 (15) | MD§ | –0.71 (–4.11 to 2.69) | 0.68 |

| Median (IQR) | 12 (7–21) | 14 (8–22) | |||

| In the hospital | |||||

| Mean (sd) | 20 (19) | 22 (18) | MD | –2 (–6.22 to 2.23) | 0.35 |

| Median (IQR) | 16 (8–25) | 18 (10–28) | |||

| ICU-free days in 28 days | |||||

| Mean (sd) | 4 (8) | 5 (8) | MD | 0.72 (0.39–1.32) | 0.39 |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0–10) | 0 (0–12) | |||

Fig 2.

Primary outcome distribution. Data derived from the intention-to-treat population, consisting of all randomised patients with informed consent, are presented. A primary outcome is defined as ventilator-free days in 28 days. The figure illustrates a line graph mapping the cumulative frequency of ventilator-free days on the y-axis against the number of ventilator-free days on the x-axis, for two distinct groups. The intervention group is represented by a blue line, whereas the control group is depicted with an orange line. Each point along the lines corresponds to the cumulative frequency of patients achieving up to that number of ventilator-free days. Despite the visual trends suggested by the lines, statistical analysis indicates no significant differences between the two groups across the range of categories represented. The graph thus conveys the comparative outcomes of the intervention and control groups with respect to the duration of ventilator-free periods.

Fig 3.

Ordinal primary outcome divided into 28 categories. The figure presents a categorical distribution of mechanical ventilation-free days among patients, depicted across 28 categories. The category representing zero ventilator-free days is highlighted in dark green, signifying the highest frequency within the dataset. Progressively, categories indicating a greater number of ventilator-free days are denoted with progressively more intense shades of orange.

Secondary, tertiary, and safety outcomes and adverse events

There were no differences between groups in any secondary, tertiary, and safety outcomes (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S8 from Supplementary material S3). Barotrauma occurrence within 28 days was no different between groups (4% in the intervention group vs 3% in the control group; odds ratio 1.35, 95% CI 0.28–6.55; P=0.71).

Discussion

In this trial, enrolling adults with moderate to severe ARDS secondary to CAP, a driving pressure-limiting strategy based on PEEP titration according to best respiratory system compliance and tidal volume adjustment did not increase the number of ventilator-free days in 28 days compared with a standard low PEEP strategy. There were no significant differences in secondary outcomes or in the risk of adverse events.

Following the publication of a post hoc analysis of patient-level data from five clinical trials identifying driving pressure as a mediator of mortality in ARDS,5 and observational studies showing an association between driving pressure and survival,1 independently of tidal volume,20 interest grew in limiting of this parameter to reduce mortality beyond low tidal volumes and limited plateau pressure. Nonetheless, randomised clinical trials were needed to determine whether a mechanical ventilation strategy targeting lower driving pressures would improve outcomes. Driving pressure represents the most accessible surrogate index for quantifying dynamic cyclic lung strain.21 Therefore, its limitation is a plausible mechanism to reduce ventilator-induced lung injury. Continuous cyclic opening and closing of collapsed but recruitable pulmonary segments during normal breathing cycles generate substantial local tension forces, leading to alveolar damage.22 Therefore, it is hypothesised that PEEP should be optimised to maintain most of the recruitable, collapsed pulmonary units open to prevent atelectrauma and reduce mechanical variability across lung regions but should be low enough to avoid excessive distention of the aerated lung regions.23 Optimised PEEP with reducing tidal volumes may reduce driving pressure, as it potentially improves respiratory system compliance.5 The driving pressure-limiting strategy of this study aimed to operationalise this concept by acting on the determinants of driving pressure: respiratory system compliance and tidal volume. However, similar to other trials, there were no substantial differences in respiratory system compliance by adjusting PEEP based on best compliance compared with the low PEEP table.2,24 Furthermore, reductions in tidal volume below 6 ml kg−1 were often unnecessary to limit driving pressure or impossible in the most severe cases because of important respiratory acidosis. Conversely, ventilatory parameters in both groups were similar, including PEEP, despite different titration methods. For most patients in the control group, PEEP applied according to the PEEP:FiO2 table paired with a tidal volume of 6 ml kg−1 predicted body weight resulted in driving pressures below the 14 cm H2O limit, the target for the intervention group. Thus, the driving pressure-limiting strategy led to a small, clinically insignificant difference of 0.7 cm H2O in driving pressure between groups. Based on our findings, it is unlikely that further trials solely targeting driving pressure reductions via mechanical ventilation adjustments would find substantial changes in driving pressure itself or clinical outcomes.

Other clinical trials on mechanical ventilation strategies resulting in differences in driving pressure between groups also did not find any beneficial effect on clinical outcomes. Cavalcanti and colleauges2 compared the same PEEP titration technique we used plus high pressures recruitment manoeuvre with the low PEEP table strategy. Modest differences in driving pressure were found, but mortality was higher in the intervention group. Similarly, Hodgson and colleagues25 and Kacmarek and colleagues26 compared open lung strategies involving recruitment manoeuvres and low PEEP strategies and found modest differences in driving pressure between groups without corresponding improvements in clinical outcomes. Richard and colleagues27 compared ultra-low tidal volume with conventional low tidal volume ventilation and found no significant differences in all-cause mortality and ventilator-free days, regardless of significant differences in driving pressure and tidal volume between groups, with respiratory acidosis more frequent in the intervention group. Adding extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCO2R) to facilitate ventilation with ultra-low volume and treating respiratory acidosis resulted in greater decreases in driving pressure and tidal volume but did not improve clinical outcomes.28

Although we aimed to use a more homogeneous ARDS population in our study by including only pulmonary aetiology cases to reduce the heterogeneity of treatment effects, there remain biological, physiological, and clinical differences that help identify consistent subpopulations with distinct functional or pathobiological mechanisms (endotypes) that may respond differently to treatments.20,29, 30, 31, 32 These underlying variations likely influenced our results.

This trial has strengths. There was high protocol adherence in both groups. Bias was controlled using concealed allocation and intention-to-treat analysis and avoiding follow-up losses. Population enrichment with CAP patients may contribute to a more homogeneous response to treatment and increased effect sizes. Strict stopping rules maximise safety during the incremental phase of PEEP titration. This clinical trial pioneers the impact of a personalised ventilator strategy with driving pressure limitation for ARDS patients in a randomised fashion.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, patients, healthcare personnel, and the outcome assessors were not blinded to group assignment. However, the objective feature of the primary outcome and standardisation of co-interventions potentially minimise bias. Second, the study was terminated early, making it underpowered to detect smaller, clinically meaningful differences in the primary outcome. However, the effect on the hypothesised mediator, driving pressure, was small and precise, suggesting that a larger sample would be unlikely to change clinical outcomes. Third, the high ICU mortality difference favouring the control group, along with a wide CI, suggests a greater likelihood of harm in the intervention group. However, this aligns with our previous findings (ART)2 and other studies on extended lung protective ventilation in COVID-19 patients (Costa Annals).33 Fourth, our results may not be applicable to ARDS patients not secondary to CAP. Fifth, although our PEEP titration included an ascending phase that could be interpreted as a recruitment manoeuvre, which is not recommended as first-line therapy, we set a stopping criterion that is below the pressure threshold used in the definition of recruitment manoeuvres.34

Conclusions

In patients with moderate to severe ARDS secondary to CAP, a driving pressure-limited strategy based on PEEP titration according to best respiratory system compliance and tidal volume adjustment compared with low PEEP:FiO2 table did not increase the number of ventilator-free days over 28 days. Further trials assessing strategies based only on mechanical ventilation adjustments to decrease driving pressure are unlikely to achieve substantial differences in driving pressure itself and, thus, in clinical outcomes. It seems advisable to consider other options for ventilator management such as electrical impedance tomography to define PEEP, better understanding and management of ventilator asynchrony that may result in patient harm, and possibly different ventilatory modes.

Authors’ contributions

Had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis: ISM, ABC, JSO

Concept and design: FZ, ISM, ABC, VCV, LPD, MPR, RB, FRM, JCF

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: ISM, ERRS, ABC, JSO, LPD, JCF, FRM Drafting of the manuscript: ISM, FZ, ABC, LT, VCV, JSO, JCF

Acquisition of the data, critical revision of the article, and final approval of the version submitted for publication: VCV, ERRS, LGB, MLN, RMG, KLN, TAM, LNL, CZ, MPP, GAW, RPF, RF, CLSB, LFN, EB, RL, MPR, MCM, MSAF, VCSD, PAB, MEH, CG, ASL, ALM, MB, ACS, RB, FDP, EC, MMT, AAP, RTL, GA, MG, PA, FL, CRHF, LM, EP, GOT, FJCF, BT

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: FZ, ABC, JCF, JSO, LT, VCV, FRM

Obtained funding: FZ, ABC

Administrative, technical, or material support: ERRS, LGB, MLN, RMG, KLN, TAM, LNL, ABC

Supervision: ABC, FGZ, FRM, JCF, MPR, RB, VCV

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professors Rinaldo Bellomo, Michael Bailey, and Paul Young for participating in the data safety monitoring committee. The authors also thank all coordinating site staff, the Brazilian Ministry of Health—Programa de Apoio e Desenvolvimento Institucional do Sistema Unico de Saude (PROADI-SUS), and all members of the Brazilian Research Network in Intensive Care (BricNet).

Funding

This work was supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health—Programa de Apoio e Desenvolvimento Institucional do Sistema Único de Saúde (PROADI-SUS). It did not participate in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Handling Editor: Rupert Pearse

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.10.012.

Data availability

De-identified individual participant data collected during the STAMINA trial (and the data dictionary) will be shared beginning 2 yr after article publication with no end date. These data will be available to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal for the purposes of achieving specific aims outlined in that proposal along with evidence of approval of the proposal by an accredited ethics committee. Proposals should be directed to fzampier@ualberta.ca or ismaia@hcor.com.br. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement and confirm that data will only be used for the agreed purpose for which access was granted.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bellani G., Laffey J.G., Pham T., et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315:788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavalcanti A.B., Suzumura É.A., Laranjeira L.N., et al. Effect of lung recruitment and titrated positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) vs low PEEP on mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1335–1345. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.14171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattinoni L., Marini J.J., Pesenti A., Quintel M., Mancebo J., Brochard L. The “baby lung” became an adult. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:663–673. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan E., Brodie D., Slutsky A.S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2018;319:698–710. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amato M.B., Meade M.O., Slutsky A.S., et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1410639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villar J., Martín-Rodríguez C., Domínguez-Berrot A.M., et al. A quantile analysis of plateau and driving pressures: effects on mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome receiving lung-protective ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:843–850. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bos L.D.J., Ware L.B. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: causes, pathophysiology, and phenotypes. Lancet. 2022;400:1145–1156. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01485-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gattinoni L., Pelosi P., Suter P.M., Pedoto A., Vercesi P., Lissoni A. Acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease. Different syndromes? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:3–11. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9708031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelosi P., D'Onofrio D., Chiumello D., et al. Pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome are different. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;42:48s–56s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00420803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zampieri F.G., Costa E.L., Iwashyna T.J., et al. Heterogeneous effects of alveolar recruitment in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a machine learning reanalysis of the Alveolar Recruitment for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Trial. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mittermaier M., Pickerodt P., Kurth F., et al. Evaluation of PEEP and prone positioning in early COVID-19 ARDS. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roesthuis L., van den Berg M., van der Hoeven H. Advanced respiratory monitoring in COVID-19 patients: use less PEEP. Crit Care. 2020;24:230. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02953-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira Romano M.L., Maia I.S., Laranjeira L.N., et al. Driving pressure-limited strategy for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. a pilot randomized clinical trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17:596–604. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201907-506OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richard J.C., Marque S., Gros A., et al. Feasibility and safety of ultra-low tidal volume ventilation without extracorporeal circulation in moderately severe and severe ARDS patients. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:1590–1598. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L., Jonkman A., Pereira S.M., Lu C., Brochard L. Driving pressure monitoring during acute respiratory failure in 2020. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2021;27:303–310. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brower R.G., Matthay M.A., Morris A., Schoenfeld D., Thompson B.T., Wheeler A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D., Thompson B.T., et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomazini B.M., Maia I.S., Cavalcanti A.B., et al. Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator-free in patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19: the CoDEX randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:1307–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goligher E.C., Costa E.L.V., Yarnell C.J., et al. Effect of lowering Vt on mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome varies with respiratory system elastance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:1378–1385. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202009-3536OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Protti A., Andreis D.T., Monti M., et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation: any difference between statics and dynamics? Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1046–1055. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827417a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slutsky A.S., Ranieri V.M. Ventilator-induced lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2126–2136. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahetya S.K. Searching for the optimal positive end-expiratory pressure for lung protective ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2020;26:53–58. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pintado M.C., de Pablo R., Trascasa M., et al. Individualized PEEP setting in subjects with ARDS: a randomized controlled pilot study. Respir Care. 2013;58:1416–1423. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodgson C.L., Cooper D.J., Arabi Y., et al. Maximal recruitment open lung ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome (PHARLAP). A phase II, multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:1363–1372. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201901-0109OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kacmarek R.M., Villar J., Sulemanji D., et al. Open lung approach for the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a pilot, randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:32–42. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richard J.C., Terzi N., Yonis H., et al. Ultra-low tidal volume ventilation for COVID-19-related ARDS in France (VT4COVID): a multicentre, open-label, parallel-group, randomised trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11:991–1002. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNamee J.J., Gillies M.A., Barrett N.A., et al. Effect of lower tidal volume ventilation facilitated by extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal vs standard care ventilation on 90-day mortality in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: the REST randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1013–1023. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calfee C.S., Delucchi K., Parsons P.E., et al. Subphenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: latent class analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:611–620. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calfee C.S., Janz D.R., Bernard G.R., et al. Distinct molecular phenotypes of direct vs indirect ARDS in single-center and multicenter studies. Chest. 2015;147:1539–1548. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaver C.M., Bastarache J.A. Clinical and biological heterogeneity in acute respiratory distress syndrome: direct versus indirect lung injury. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35:639–653. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dianti J., McNamee J.J., Slutsky A.S., et al. Determinants of effect of extracorporeal CO2 removal in hypoxemic respiratory failure. NEJM Evid. 2023;2 doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2200295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa E.L.V., Alcala G.C., Tucci M.R., et al. Impact of extended lung protection during mechanical ventilation on lung recovery in patients with COVID-19 ARDS: a phase II randomized controlled trial. Ann Intensive Care. 2024;14:85. doi: 10.1186/s13613-024-01297-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grasselli G., Calfee C.S., Camporota L., et al. ESICM guidelines on acute respiratory distress syndrome: definition, phenotyping and respiratory support strategies. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49:727–759. doi: 10.1007/s00134-023-07050-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified individual participant data collected during the STAMINA trial (and the data dictionary) will be shared beginning 2 yr after article publication with no end date. These data will be available to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal for the purposes of achieving specific aims outlined in that proposal along with evidence of approval of the proposal by an accredited ethics committee. Proposals should be directed to fzampier@ualberta.ca or ismaia@hcor.com.br. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement and confirm that data will only be used for the agreed purpose for which access was granted.