Summary

Optimal postoperative pain management is a prerequisite for enhancing functional recovery after surgery. However, many studies assessing analgesic interventions have limitations. Consequently, further improvements in study design are urgently needed. In this focused editorial, we critically review prevalent trial designs and outcome measures including treatment-related adverse events evaluating analgesic interventions. Novel clinical trial designs should improve efficiency and enhance the likelihood of detecting relevant treatment effects. Cohort and database studies using propensity score matching and directed acyclic graphs could provide real-world generalisable information. Procedure-specific and patient-specific trials should allow identification of subpopulations most likely to benefit from a particular intervention after a specific surgical procedure and thus ascertain optimal analgesic strategies in challenging populations.

Keywords: analgesics, enhanced recovery after surgery, evidence base, perioperative pain, research, study design, trials

Optimal postoperative pain management is a prerequisite for enhancing functional recovery after surgery.1 Inadequate control of pain delays discharge from hospital and is one of the reasons for delayed return to activities of daily living.2 However, postoperative pain continues to be inadequately and inappropriately managed. Evidence-based, procedure-specific pain management recommendations, such as those developed by the PROSPECT (PROcedure-SPECific postoperative pain management) collaboration, which consists of surgeons and anaesthetists with broad international representation, should facilitate optimal pain management protocols.3

The PROSPECT methodology involves conducting a systematic review of literature and critically evaluating the available evidence.3 Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) are considered by the PROSPECT group for efficacy and effectiveness, whereas RCTs, observational studies, and large case series are considered for establishing side-effect profiles.3 A modified Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) approach is used for grading the level of evidence and strength of recommendations.3,4 However, guidelines are based on the best available evidence and are often limited by the lack of evidence or poor quality of evidence because of a paucity of well-designed studies. Another challenge for the interpretation of available RCTs is the lack of use of evidence-based baseline analgesia in addition to the trial intervention, hindering interpretation of efficacy of new analgesics.5 Here we critically review prevalent trial designs and outcome measures including treatment-related adverse events in the evaluation of analgesic interventions.

Study design and reporting

The complexity of perioperative pathophysiology and risk of developing complications have been drivers for the introduction of the concept of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS),6,7 but the debate continues regarding the optimal study design to demonstrate the relative importance of different ERAS elements, including pain management.2 Core elements that should guide trustworthy research and recommendations for specific actions and behaviours for different stakeholders in the research have been published recently.8 RCTs have served as a gold standard for assessing efficacy (performance of an intervention under ideal and controlled conditions, such as an exploratory RCT) and effectiveness (performance of an intervention under ‘real-world’ conditions, such as a pragmatic RCT) of interventions. Indeed, randomisation reduces bias and allows examination of cause-effect relationships between an intervention and outcome. However, exploratory RCTs can lack generalisability because they tend to evaluate interventions under ideal conditions among highly selected populations.

In contrast, pragmatic RCTs might be more representative of ‘real-world’ practice as they have broad eligibility and minimal exclusion criteria. They typically have a larger sample size than exploratory RCTs, are more cost-effective, and can have better generalisability as they allow for inclusion of a more diverse patient population. Pragmatic trials have limitations because they allow variability in perioperative care, and even sophisticated statistical analyses used to adjust for perioperative variability might not be adequate to compensate for the complexities of perioperative care.9 Therefore, even the conclusions of pragmatic studies can lack clinical applicability to current evidence-based perioperative care principles and might not serve well to guide current perioperative practice.9

Many novel study designs, such as cluster RCTs, platform trials, adaptive platform enrichment trials, and umbrella trials, are increasingly being used.10,11 These clinical trial designs aim at improving efficiency and enhancing the likelihood of detecting treatment effects. In enriched designs, the study population is selected or modified during the trial based on certain predefined criteria or biomarkers. For example, enrichment strategies could involve selecting patients who are known to be high-pain responders. This would enhance the likelihood of success because of an increase in statistical power (i.e. larger treatment effects) and improved efficiency (i.e. resources focused on patients more likely to benefit from the intervention). In addition, not offering an intervention to patients who either do not need or most likely will not respond to it reduces harm. Results of enriched design studies can be valuable for selected patient groups but might often not be applicable to the general population. Despite several benefits, adaptive platform enrichment trials can be challenging, require upfront planning to avoid potential limitations, and are prone to bias when removing or adding an intervention.12

Of note, novel designs require an understanding of the complexity of the perioperative pathophysiology responsible for the specific morbidity in question (e.g. postoperative pain) to reach clinically relevant conclusions while avoiding waste of resources. This emphasises the need for smaller detailed hypothesis-generating observational studies in a fully implemented ERAS programme on different interventions as a basis for future larger confirmatory trials, which can be limited because they allow variability in perioperative care except for the intervention assessed.7 Significant heterogeneity between the control and intervention groups introduces many confounders that make RCT study design and interpretation challenging.13

It is important to perform pilot or feasibility studies before embarking on large RCTs as these provide information about difficulties in recruitment and insights into how the design for the definitive RCT needs to be modified. Preliminary results also help define relevant endpoints and calculate sample sizes. In general, well-conducted pilot and feasibility studies help refine protocols for large RCTs and avoid wastage of resources. In addition, patient-public involvement, including that of those with lived experience of the condition, in the design, monitoring, interpretation, and dissemination of studies is to be encouraged as it helps provide information about the acceptability of the intervention to the patient and helps determine which patient-relevant outcomes should be studied.

Cohort and database studies

Cohort and database studies can provide useful real-world data, and their results are sometimes more generalisable than those of RCTs. Nevertheless, limitations of database studies include no inference of causality, variation in results (e.g. complication rates) among different datasets, changes in coding systems over time, definitions used for specific variables, and variability in populations studied. There is also an inherent risk of bias, and large sample sizes can make clinically irrelevant differences statistically significant. It is prudent to identify primary endpoints before the start of these studies and calculate an appropriate sample size, as is done for RCTs. Adjustments should also be made to reduce bias and confounding.

The quality of observational studies may be improved by using propensity score matching and directed acyclic graphs (DAGs).14,15 Indeed, DAGs are increasingly popular for identifying confounding variables that require conditioning when estimating causal effects.16 DAGs include the treatment, outcome, and all known or suspected common causes of these variables. They provide a visual summary of the relationships between variables over time. This can help identify variables necessary for reducing bias when the goal is the assessment of a causal relationship.

Outcome measures

The updated CONSORT-Outcomes extension provides important aspects to be considered before choosing and reporting outcomes in a trial.17 The core outcome set (COS) for analgesic studies can be based on guidelines or consensus.17,18 The outcomes assessed need to be meaningful to several stakeholders and should be relevant for recovery after surgery.18 It is accepted that pain trials should assess pain intensity using well-defined procedure-specific pain-evoking manoeuvres.19 Despite the emphasis on the evaluation of movement-evoked pain, most studies continue to assess pain intensity at rest.19,20 A multidimensional pain assessment is proposed; however, relationships between pain intensity scores and other methods of pain assessment (e.g. acceptability of pain or its interference with physical functioning) have not been fully established.21,22 In addition, there remains significant variability in studies that have assessed functional outcomes,20 and there continues to be significant variability in the frequency of data collection for pain studies. Most studies have assessed pain for a short duration (e.g. up to 72 h postoperatively). Following patients until the pain is resolved should allow the identification of pain trajectories, determination of the development of chronic postsurgical pain, and assessment of persistent postoperative opioid use.23, 24, 25, 26 Assessment of pain and opioid use should be evaluated in the immediate and early postoperative period (days to weeks) as well as beyond surgical recovery (e.g. at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 yr).

Minimum clinically important differences (MCIDs) are the smallest meaningful differences an individual patient would identify as important, and they are needed to interpret patient-reported pain outcomes in research and clinical practice.27 Although influenced by several factors, including baseline pain, patient characteristics, and study design,28 MCIDs, rather than statistically significant differences, should be used to determine sample size estimations and the efficacy of an analgesic intervention. For opioid-sparing effects, there is no evidence for a patient-rated MCID, and the choice is somewhat arbitrary.

Assessing global measures of a patient's quality of recovery (e.g. quality of recovery instrument — QoR-15) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in addition to conventional outcome measures can better define postoperative recovery.29 Importantly, PROMs of higher quality need to be developed for assessing the multidimensional aspects of postoperative pain.30 Conventionally, hospital length of stay (LOS) has been a standard in outcome trials, but it is influenced by many elements, including pain and the ability to have adequate support for the patient in the community after discharge. Although LOS is nonspecific for pain, it is still important to supplement results of studies with a detailed analysis of ‘why is the patient still in hospital?’ serving as a basis for future interventional studies of individual relevant ERAS elements.2,31 There are two strategies: one mostly based on PROMs,32 but with additional views from surgical outcome studies emphasising more hard outcome data with complications and society-dependent healthcare burden (Clavien-Dindo Scale and Comprehensive Complication Index)33 potentially supplemented by relevant outcomes such as days alive and out of hospital (DAOH).34 These outcome strategies have mostly been supported by anaesthesia-based stakeholders or surgeon-directed trials, but there is a need for standardisation to compare trials in the future.2,7,33

Treatment-related adverse outcomes

Risk-benefit ratios focus on risks. Similar to all medicines, opioid and nonopioid analgesics have side-effects and can be associated with adverse events. It has been estimated that 50–80% of patients in clinical trials experience at least one side-effect from opioid therapy.35 However, this might be higher in routine use.36,37 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and other analgesics also have adverse effect profiles.37 Hence, it is also necessary to report outcomes related to adverse events and patient safety and understand the barriers to administering appropriate opioid and nonopioid analgesics (e.g. NSAIDS and regional analgesia) to all eligible patients.29

Frameworks for research and the provision of clinical care

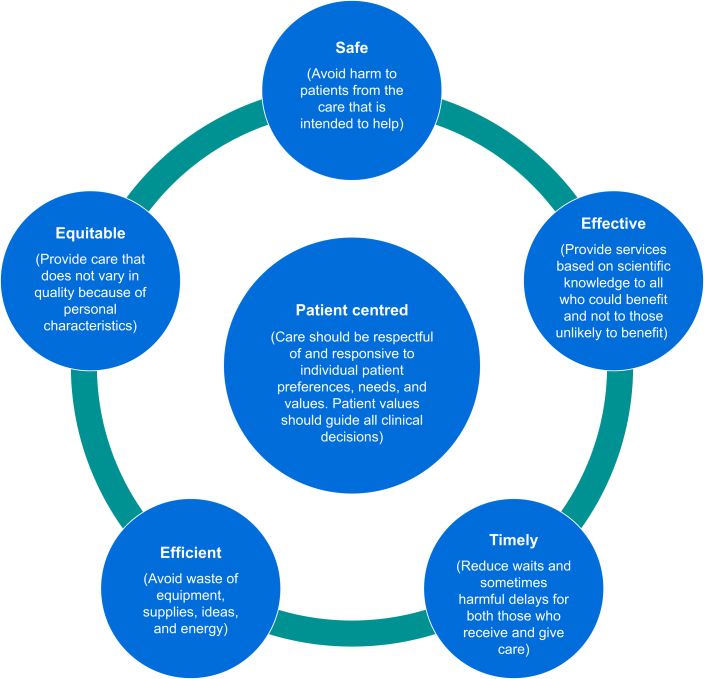

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)38 recommends the six domains of healthcare quality proposed by the Institute of Medicine39 as a framework for the development of healthcare and research strategies in both the public and private care sectors (Fig. 1). Frameworks such as these help both providers and consumers grasp the meaning and relevance of adopting such quality measures and help in the design of future research protocols. Desirable components for research on perioperative pain are summarised in Supplementary Table S1.

Fig 1.

Six domains of healthcare quality based on data from the Institute of Medicine39 and the Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality.38

Clinical trials provide the basis for developing treatment strategies. However, many studies assessing analgesic interventions have significant limitations. Therefore, further improvements in study design are urgently needed. Future analgesic trials should be procedure-specific and patient-specific. This should allow the identification of subpopulations most likely to benefit from a particular intervention after a specific surgical procedure and thus ascertain optimal analgesic strategies in challenging populations. Study designs should allow the determination of optimal patient and procedure-specific analgesic combinations (multimodal analgesia), timing (preventive analgesia), and duration of analgesic administration.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contribution to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, thereby ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: all authors.

Declarations of interest

GPJ has received honoraria for consultation from Merck Sharpe and Dohme Inc., Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Haisco-USA Pharmaceuticals. HB has no declarations to make. DNL has received an unrestricted educational grant from B. Braun for unrelated work. He has also received speaker's honoraria for unrelated work from Abbott, Nestlé, and Corza. EPZ has received financial support for research activities, advisory, or lecture fees from Gruenenthal, MSD/Merck, and Medtronic. In addition, she receives scientific support from the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA), and the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement No. 777500. This Joint Undertaking receives support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA. All money goes to EPZ institutions. AS has no declarations to make. MV has received support for lectures, consultancy, or both, from CSL Behring/CSL Vifor, Werfen, Viatris, and Aquettant. CW and HK have no declarations to make.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

None used.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.11.004.

Contributor Information

Girish P. Joshi, Email: girish.joshi@utsouthwestern.edu.

PROSPECT Working Group of the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy:

Eric Albrecht, Helene Beloeil, Marie-Pierre Bonnet, Dario Bugada, Néel Desai, Geertrui Dewinter, Stephan M. Freys, Girish P. Joshi, Henrik Kehlet, Patricia Lavand'homme, Dileep N. Lobo, Eleni Moka, Esther M. Pogatzki-Zahn, Johan Raeder, Narinder Rawal, Axel R. Sauter, Marc Van de Velde, and Christopher L. Wu

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Joshi G.P. Rational multimodal analgesia for perioperative pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2023;27:227–237. doi: 10.1007/s11916-023-01137-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobo D.N., Joshi G.P., Kehlet H. Challenges in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) research. Br J Anaesth. 2024;133:717–721. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2024.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi G.P., Albrecht E., Van de Velde M., Kehlet H., Lobo D.N., Prospect Working Group of the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia Pain Therapy PROSPECT methodology for developing procedure-specific pain management recommendations: an update. Anaesthesia. 2023;78:1386–1392. doi: 10.1111/anae.16135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guyatt G., Oxman A.D., Akl E.A., et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi G.P., Stewart J., Kehlet H. Critical appraisal of randomised trials assessing regional analgesic interventions for knee arthroplasty: implications for postoperative pain guidelines development. Br J Anaesth. 2022;129:142–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:606–617. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.5.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kehlet H., Lobo D.N. Exploring the need for reconsideration of trial design in perioperative outcomes research: a narrative review. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;70 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Connell N., Belton J., Crombez G., et al. ENTRUST-PE: an integrated framework for trustworthy pain evidence. White Paper. 2024 https://osf.io/preprints/osf/e39ys Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi G.P., Alexander J.C., Kehlet H. Large pragmatic randomised controlled trials in peri-operative decision making: are they really the gold standard? Anaesthesia. 2018;73:799–803. doi: 10.1111/anae.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holder-Murray J., Esper S.A., Althans A.R., et al. REMAP Periop: a randomised, embedded, multifactorial adaptive platform trial protocol for perioperative medicine to determine the optimal enhanced recovery pathway components in complex abdominal surgery patients within a US healthcare system. BMJ Open. 2023;13 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-078711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myles P.S., Yeung J., Beattie W.S., Ryan E.G., Heritier S., McArthur C.J. Platform trials for anaesthesia and perioperative medicine: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2023;130:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenig F., Spiertz C., Millar D., et al. Current state-of-the-art and gaps in platform trials: 10 things you should know, insights from EU-PEARL. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;67 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorgensen C.C., Kehlet H. Center for Fast-track Hip Knee Replacement Collaborative Group. Outcome improvement for anaemia and iron deficiency in ERAS hip and knee arthroplasty: a descriptive analysis. Perioper Med (Lond) 2024;13:60. doi: 10.1186/s13741-024-00426-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheema H., Brophy R., Collins J., et al. Causal relationships between pain, medical treatments, and knee osteoarthritis: a graphical causal model to guide analyses. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2024;32:319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2023.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipsky A.M., Greenland S. Causal directed acyclic graphs. JAMA. 2022;327:1083–1084. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tennant P.W.G., Murray E.J., Arnold K.F., et al. Use of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to identify confounders in applied health research: review and recommendations. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50:620–632. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butcher N.J., Monsour A., Mew E.J., et al. Guidelines for reporting outcomes in trial reports: the CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 Extension. JAMA. 2022;328:2252–2264. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson P.R., Altman D.G., Bagley H., et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18:280. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilron I., Lao N., Carley M., et al. Movement-evoked pain versus pain at rest in postsurgical clinical trials and in meta-analyses: an updated systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2024;140:442–449. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baamer R.M., Iqbal A., Lobo D.N., Knaggs R.D., Levy N.A., Toh L.S. Utility of unidimensional and functional pain assessment tools in adult postoperative patients: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:874–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komann M., Dreiling J., Baumbach P., et al. Objectively measured activity is not associated with average pain intensity 1 week after surgery: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Pain. 2024;28:1330–1342. doi: 10.1002/ejp.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Boekel R.L.M., Vissers K.C.P., van der Sande R., Bronkhorst E., Lerou J.G.C., Steegers M.A.H. Moving beyond pain scores: multidimensional pain assessment is essential for adequate pain management after surgery. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brummett C.M., Waljee J.F., Goesling J., et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy N., Quinlan J., El-Boghdadly K., et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus statement on the prevention of opioid-related harm in adult surgical patients. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:520–536. doi: 10.1111/anae.15262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macintyre P.E., Quinlan J., Levy N., Lobo D.N. Current issues in the use of opioids for the management of postoperative pain: a review. JAMA Surg. 2022;157:158–166. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Boghdadly K., Levy N.A., Fawcett W.J., et al. Peri-operative pain management in adults: a multidisciplinary consensus statement from the Association of Anaesthetists and the British Pain Society. Anaesthesia. 2024;79:1220–1236. doi: 10.1111/anae.16391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myles P.S., Myles D.B., Galagher W., et al. Measuring acute postoperative pain using the visual analog scale: the minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:424–429. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsen M.F., Bjerre E., Hansen M.D., Tendal B., Hilden J., Hrobjartsson A. Minimum clinically important differences in chronic pain vary considerably by baseline pain and methodological factors: systematic review of empirical studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;101:87–106 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pogatzki-Zahn E.M., Liedgens H., Hummelshoj L., et al. Developing consensus on core outcome domains for assessing effectiveness in perioperative pain management: results of the PROMPT/IMI-PainCare Delphi Meeting. Pain. 2021;162:2717–2736. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vollert J., Segelcke D., Weinmann C., et al. Responsiveness of multiple patient-reported outcome measures for acute postsurgical pain: primary results from the international multi-centre PROMPT NIT-1 study. Br J Anaesth. 2024;132:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2023.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang L., Kehlet H., Petersen R.H. Reasons for staying in hospital after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy. BJS Open. 2022;6 doi: 10.1093/bjsopen/zrac050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myles P.S., Boney O., Botti M., et al. Systematic review and consensus definitions for the Standardised Endpoints in Perioperative Medicine (StEP) initiative: patient comfort. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbassi F., Walbert C., Kehlet H., Grocott M.P.W., Puhan M.A., Clavien P.A. Perioperative outcome assessment from the perspectives of different stakeholders: need for reconsideration? Br J Anaesth. 2023;131:969–971. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2023.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang L., Frandsen M.N., Kehlet H., Petersen R.H. Days alive and out of hospital after enhanced recovery video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022;62 doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezac148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore R.A., McQuay H.J. Prevalence of opioid adverse events in chronic non-malignant pain: systematic review of randomised trials of oral opioids. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R1046–R1051. doi: 10.1186/ar1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Side Effects of Opioids. Available from: https://fpm.ac.uk/opioids-aware-clinical-use-opioids/side-effects-opioids (accessed 28 October 2024).

- 37.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence British National formulary. Analgesics. 2024 https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/analgesics/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Six Domains Healthc Qual. 2022 https://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/measures/six-domains.html Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . National Academies Press (US); Washington (DC): 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

@DL08OMD

@DL08OMD