Graphical abstract

Keywords: Thyme essential oil (TEO), Mannosylerythritol lipid-A (MEL-A), Ultrasonic emulsification, Microencapsulation, Antioxidant activity, Antibacterial activity

Abstract

Mannosylerythritol lipid-A (MEL-A) is a kind of novel biosurfactant and has great potential to apply into food and pharmaceutical field with its outstanding physicochemical and biological property. In this study, Thyme essential oil (TEO) microcapsules based on MEL-A were prepared through ultrasonic emulsification and characterized by size, morphology, structure, antioxidant and antibacterial activity. The results showed the optimal preparation condition was the duration of 15 min and power intensities of 400 W/cm2 through ultrasound treatment, improving the solubility and applicability of TEO. Further experiment explored the physicochemical properties and biological activity of TEO microcapsules, measuring a particle size of 276.19 ± 1.72 nm with good dispersibility. FT-IR, X-ray, and TEM confirmed the successful encapsulation of the essential oil within the microcapsules. Meanwhile, the antioxidant and antibacterial properties of microcapsules were assayed and microcapsules with 7 % MEL-A exhibited better antioxidant properties, while those containing 13 % MEL-A showed better antibacterial performance. In conclusion, MEL-A showed obvious structural stability and functional enhancement in TEO-loaded microcapsules, indicating that its potential applications in food preservation and food machinery sterilization are numerous.

1. Introduction

Essential oils are widely recognized for their safety, high efficiency, and non-toxicity. However, their strong taste and aroma affect the sensory quality of food. Additionally, essential oils are sensitive to external conditions and have characteristics, such as, easy decomposition, high volatility, and poor water solubility, which can impact their antibacterial activity [1]. In order to better utilize essential oils in the food industry for their antibacterial effects, nano-microencapsulation technology has been developed and widely used. This technology can enhance the antioxidant and antibacterial activities of foods, increase the distribution of essential oils in formulations, thus increased storage time for food products, making it an excellent antibacterial agent for food preservation. Thymol, found in TEO, is capable of multiple pharmacological activities such as anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and preservative effects. Strong antibacterial action of thymol is demonstrated against Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Listeria monocytogenes) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Salmonella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [2], as well as fungi (Candida albicans, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus ochraceus) [3], demonstrating its excellent antibacterial activity. Therefore, thymol is registered in the European Union list of flavourings and its edibility has been notarised by the FDA [4].

Biosurfactants are surface-active biomolecules with favorable pharmacological properties and emulsifying properties [5]. The biosurfactants have several advantages over chemical surfactants, including low toxicity, great biodegradability, broad application and superior performance in severe pH, salinity, and temperature ranges. [6]. Mannosylerythritol lipids (MELs) can be used as an excellent biosurfactant, at the same time, its antimicrobial activity has been demonstrated on a diverse array of bacteria, and some of these have been applied as effective substitutes for microbial agents and synthetic drugs [7]. MELs also exhibit favorable biological features, including microbial inhibitory and anticancer activity, as well as biodegradability and emulsification capabilities. There is significant potential for implementation in the fields of food, medicine, cosmetics, and so on [8]. MELs are made of two parts (Fig. 1) [5], hydrophilic and hydrophobic groups, respectively [9]. It is the various physiological functions of MEL-A that it has attracted people's attention. Studies have shown that MEL-A significantly disrupts cell membranes and cell morphology [10], and also, alters the water-retaining capacity and rheological properties of frozen dough [11]. Additionally, MEL-A can be used as an anti-biofilm agent to reduce food contamination [12]. Typically, the raw materials for glycolipid surfactants are inexpensive and readily available. Furthermore, compared to synthetic emulsifiers, glycolipid biosurfactants demonstrate a stronger ability to emulsify hydrocarbons, making them excellent candidates as emulsifiers [13]. Chen et al. [14] found that MEL-A has a significant emulsifying effect on chicken myofibrillar protein.

Fig. 1.

The chemical structures of the MELs [5].

The innovation of this study lies in the selection of MEL-A instead of Tween 80 as the emulsifier for the preparation of TEO microcapsules. The study aims to explore the optimal conditions for successfully encapsulating essential oil in microcapsules and to examine the changes in their physicochemical and functional properties (antioxidant and antibacterial activities). On this basis, the findings can provide valuable references for improving the utilization rate of various essential oils. Additionally, further research can be conducted to evaluate the antibacterial mechanism of MEL-A, thereby providing a theoretical framework for its extensive application in the food industry.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

MEL-A were obtained from the laboratory, and all the reagents used in this experiment were analytically pure.

2.2. Preparation of microcapsule

Microcapsules were prepared using the ultrasonic emulsification method. Ultrasonication is a low-cost and energy-efficient technique that can transform coarse emulsions into microemulsions through mechanical vibration and cavitation effects during the process, resulting in a relatively stable emulsion. Referring to Wu et al. [15] experimental protocol with slight modifications. For the preparation of microcapsule forming solution, 0.1 % (w/v) chitosan solution was prepared and set aside. Under the action of magnetic stirrer, different concentrations of (0.05 %, 0.075 %, 0.1 %) sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) solution were added drop by drop into the chitosan solution in the ratio of 2:1. The effects of different concentrations of TPP solutions on the particle size of microcapsules were investigated.

Different concentrations (5 %, 7 %, 9 %, 11 %, 13 %) of MEL-A were added to the prepared chitosan solution and stirring was continued for 1 h, after which TEO was added. Then the crude emulsion was prepared by shearing at 10,000 r/min for 3 min using a high-speed shear disperser under ice bath conditions. The microemulsion was subjected to ultrasonic treatment at a power intensity of 400 W/cm2 for fifteen minutes (JY92-2D Ultrasonic Cell Pulverizer). Finally, TPP solution was added to the prepared oil-in-water emulsion. The emulsion was centrifuged at 10,000 r/min for 20 min, and the precipitation was collected as microcapsules and then freeze-dried for the further characterization.

2.3. Determination of particle size and zeta potential

According to Zhang's [16] method. The particle size, PDI (polydispersity index) and zeta potential of the microcapsule samples were determined using a DLS (Dynamic Light Scattering). The measurement temperature was 25 °C and the measurement angle was 90°.

2.4. Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR)

According to the method of Bashir et al. [17]. The FT-IR spectra of the microemulsion samples were recorded using an FT-IR spectrometer in the attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode, with air as the background.

2.5. X-ray diffraction (XRD) evaluation

According to the method of Du et al. [18]. XRD was applied to analyze the physical properties of microcapsules. The sweep of XRD was in the range of 2θ = 5–90°.

2.6. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) characterization of microcapsules

Learning from the methods of Zhu and others [19]. The prepared microemulsion was diluted to 1 % concentration, and a small amount of the suspension was pipetted by a pipette gun. The solution was poured on a copper grid and entirely evaporated until completely dry. Afterwards, the internal structure and particle size of the nanocapsules were observed under TEM.

2.7. Thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) determination

Applying the method of Liu et al. [20].The thermal degradation process of the samples was determined using a TGA. The temperature scanning range of the microcapsules is 50 ∼ 500 °C, the heating process is conducted at a rate of 5 °C/min, with a nitrogen flow rate of 60 mL/min.

2.8. Antioxidant experiment

2.8.1. Determination of DPPH radical scavenging ability

According to the method of Li et al. [21].Pipette different concentrations of microemulsion each 2.0 mL, equal volume added 0.2 mmol/L DPPH solution, shaking well and avoiding light reaction for 30 min, the absorbance measurements at 517 nm were A1, and calculated according to Eq. (1).

| (1) |

where A0, A1 and A2 are the absorbance at 517 nm of DPPH solution and an equal volume of ethanol, microemulsion and DPPH solution; microemulsion and an equal volume of ethanol, respectively.

2.8.2. Assessment of ABTS free radical scavenging capability

According to the method of Zielinska et al. [22].The ABTS stock solution was obtained by mixing equal volumes of ABTS solution (7.0 mmol/L) and K2O8S2 solution (2.45 mmol/L). The ABTS working solution was placed at 25 °C and protected from light for 16 h. The ABTS stock solution was diluted with 80 % ethanol until the absorbance at 734 nm was 0.70 ± 0.02, and then ABTS working solution was obtained.

Add 8 mL of ABTS working solution into 2 mL of microemulsion, shake well, and then react for 60 min at 25 °C, dark reaction, and measure the absorbance at 734 nm. The radical scavenging rate of ABTS was calculated according to Eq. (2)

| (2) |

where A0, A1 and A2 are the absorbance values of 80 % ethanol and ABTS working solution, sample and ABTS working solution, and sample and 80 % ethanol at 734 nm, respectively.

2.9. Determination of antimicrobial activity

The bacteriostatic effect of TEO microcapsules on S. aureus and E. coli was determined by the method of Ge et al. [23]. Firstly, the two bacteria were taken out from −80 °C refrigerator and resuscitated, and after 12 h, the bacterial suspension was injected into conical flasks for passaging culture, followed by making slant medium for storage and spare.

To determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of the microcapsules, we used sterile 96-well plates. Diluted bacterial solution was added along with the microcapsule solution, 100 µL of each per well. By monitoring the change in absorbance within each well, we were able to determine the MIC and MBC of the microcapsules. Subsequently, we confirmed the results using the plate spreading method to ensure their validity. Pure MEL-A was used as a positive control.

2.10. Bactericidal effect of microcapsule against S. aureus

Referring to the method of Dong et al. [24] with minor modifications. A suspension of S. aureus was stocked with a concentration of 107 CFU/mL. Then, the two groups with added microcapsules are the MIC and the MBC treatment group, and the last group without microcapsule was the control group. The mixture was thoroughly mixed and then incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. The cells were stained with OA/EB staining solution for 5 min, and finally the cell survival status was observed by inverted fluorescence microscope.

2.11. Data analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Differences between the means were analyzed using Duncan's test in SPSS Statistics 27, with a P value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Particle size and potential analysis

To determine the optimal concentration of MEL-A in the system, different concentrations of MEL-A were added to the chitosan solution under the same conditions, with the TEO concentration set at 0.05 %. It can be observed from Fig. 2 that when no MEL-A and TEO were encapsulated in the emulsion, the unloaded microcapsules formed with the smallest particle size, (201.43 ± 14.94 nm). With an increase in MEL-A concentration, the particle size of the microcapsules decreased. Similar trends were observed in the study by Wu et al. [15], indicating that the biosurfactant MEL-A can enhance the solubility of essential oils. When 7 % MEL-A was added, the microcapsules reached to the smallest particle size at 276.19 ± 1.72 nm with the best stability. When the content of MEL-A exceeds 7 %, the particle size of the microcapsules increases, and their stability also changes. The study by Álvarez [25] and others showed that: smaller nanoparticles exhibit higher inhibition against all pathogenic strains. This may be due to an excess of emulsifier, which causes an uneven distribution of surface charges on the droplets, increasing the probability of droplet collisions and resulting in larger particle sizes. Therefore, microcapsules with 7 % MEL-A were selected for subsequent experiments.

Fig. 2.

Particle size, PDI, and potential of MEL-A microcapsules with different concentrations added. Different letters indicate significant differences between each group. (P < 0.05).

The PDI value reflects the dispersity of the sample in the microemulsion system, PDI < 0.3 indicates uniform particle distribution within the system [26]. When 7 % MEL-A was added, the entire emulsion system reached the most stable state, with the smallest PDI value. As the MEL-A content increased, the PDI value also increased, which means the stability of the system is gradually being compromised. The larger the absolute value of the Zeta potential, the stronger the repulsion and the more stable the particles. As the MEL-A content increased from 0 % to 7 %, the potential also increased from 90.11 ± 1.22 mV to 98.39 ± 1.24 mV. Unlike the results of Wu et al. [27], it is inferred that the increase in the emulsifier made the droplets of the microemulsion more uniform and dispersed.

The ultrasonic emulsification method used in this study, demonstrates a more uniform particle size distribution and higher energy efficiency. Based on these findings, further research can be conducted to explore the detailed mechanisms of action of MEL-A. Moreover, this study provides insights for the development of novel microencapsulation technologies and the utilization of biosurfactants such as MEL-A to enhance the efficiency and expand the application scope of essential oils.

To investigate the optimal concentration of TPP, 0.05 % essential oil and 7 % MEL-A were added to the emulsion. Various concentrations of TPP (0.05 %, 0.075 %, 0.1 %) were slowly introduced to the chitosan solution in a dropwise manner utilizing a syringe, all while maintaining same conditions. We can observe from Fig. 3 that the size of the microcapsules was the smallest when the TPP concentration was 0.075 %. The mechanism of crosslinking relies on ionic interactions formed between the positively charged segments of chitosan and the negatively charged portions of TPP, resulting in the formation of small particles [28]. It has been reported that among the many crosslinking agents used for preparing chitosan nanoparticles/microparticles (including sulfates, citrates, and TPP), TPP is the most widely used [29]. When TPP is in excess, chitosan molecules may crosslink with an excess of TPP molecules, potentially leading to an increase in particle size. Similarly, an excess of chitosan can result in a similar outcome.

Fig. 3.

Particle size of microcapsules with different concentrations of TPP (0.05 %, 0.075 %, 0.1 %) added. Different letters indicate significant differences between each group (P < 0.05).

The ultrasound time was determined by pre-experimentation to be 15 min, microcapsules spiked with 7 % MEL-A were selected to investigate the particle size at different ultrasonic power intensity, which were selected as 200, 300 and 400 W/cm2. Observing Fig. 4 reveals that, the particle size of the microcapsules and the PDI value decreases as ultrasonic intensity rises. When the ultrasonic intensity was 400 W/cm2, the minimum particle size of TEO microcapsules was 276.19 ± 1.72 nm and the PDI value was 0.23. Thus, the optimum ultrasonic intensity was determined to be 400 W/cm2. Agrawal et al. [30] found that the greater the amplitude of ultrasound, the greater the reduction in droplet size. However, the power intensity of ultrasound is positively correlated with the amplitude, indicating that the higher the power intensity of ultrasound, the higher the amplitude, which results in a smaller droplet size of the microemulsion. It has also been shown that high power intensities can have a reverse effect on the emulsion size and over-treatment [31], therefore higher power intensities were not chosen for sonication in this experiment.

Fig. 4.

Particle size of microcapsules produced using different ultrasonic power intensity (200, 300, 400 W/cm2). Different letters indicate significant differences between each group (P < 0.05).

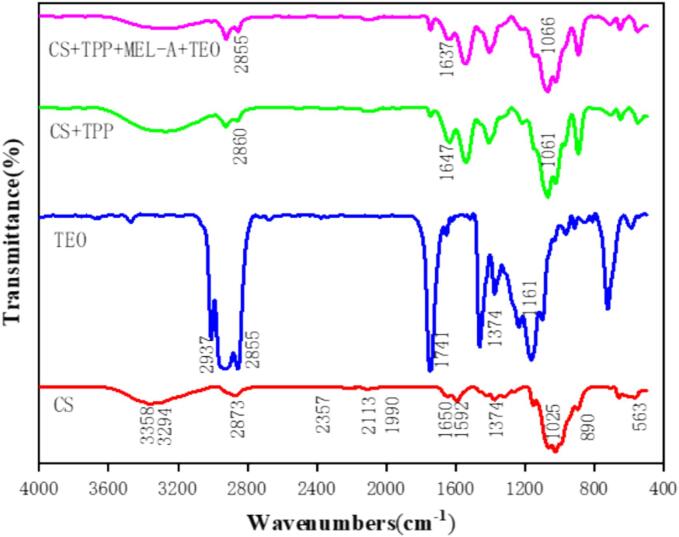

3.2. FTIR analysis

FTIR was used to analyze the properties of chitosan microcapsules and to confirm the successful formation of chitosan microcapsules encapsulated with TEOs. As shown in the Fig. 5, the peak at 3358 cm−1 is owing to the axial stretching of the O–H bond and N–H. The C–H bond stretching produces the characteristic peak at 2873 cm−1. Characteristic absorption peaks centred at 1650 cm−1 and 1592 cm−1 in chitosan were produced by amide I, amide II and amide III groups [32]. N-H bond angle shift produces the characteristic peak at 1592 cm−1. The axial stretching of C O in the acetamido group resulted in a characteristic peak at 1650 cm−1, the band seen at 1373 cm−1 associated with CH3 symmetrical distortion [33].

Fig. 5.

FTIR of CS, TEO, empty microcapsules, and essential oil-loaded microcapsules.

Compared with chitosan, the characteristic peaks at amide I of empty microcapsule and microcapsules loaded with TEO are left migrate from 1650 cm−1 to 1647 cm−1 and 1637 cm−1, respectively, the interaction between the phosphate group of TPP and the amino group of chitosan is mainly responsible for this[27].

3.3. XRD analysis

X-rays are primarily used to determine changes in the crystal structure of a substance, the peak intensities were observed to determine whether the interplay between chitosan and TPP affected the crystal structure of the microcapsules. As shown in the Fig. 6, chitosan has two special peaks at 2θ = 10° and 20°, which mainly originate from the crystalline region formed by hydrogen bonding on the amino and hydroxyl groups of the chitosan chain[34]. In the XRD pattern of the microcapsule, it was found that the original characteristic peaks basically disappeared, and new characteristic peaks appeared around 2θ = 15°, which indicated that the cross-linking reaction between chitosan and TPP occurred, and the microcapsules were successfully formed. Song et al. [35] study also showed that the incorporation of TEO may result in intricate structural alterations in chitosan nanoparticles. Meanwhile, Peng [36] and others showed that the drying method would have an effect on the crystallinity of the dried material.

Fig. 6.

XRD of CS, empty microcapsules, and essential oil loaded microcapsules.

3.4. TEM analysis

The microstructure of the prepared TEO microcapsules is presented in Fig. 7, it can be observed that the microcapsules are in the shape of regular spheres under TEM of different resolutions. Eman [37] et al. also observed in TEM that the essential oil nanoemulsions were spherical and moderately mono- or bi-disperse. And it should be pointed out that most of the droplets have the diameter of less than 500 nm, which is basically the same as that of the measurement results of the DLS, and there will be a few large droplets. In the preparation of food-grade nanoemulsions with added essential oils, Ines et al. [38] also observed that the particle size measurements derived from TEM and DLS were generally consistent, with discrepancies noted only for a few larger droplets. The cavitation effect of ultrasound and the shearing action of the homogeniser can further reduce the droplets in microemulsions.

Fig. 7.

TEM images of microcapsules. a. magnification 10,000×; b. magnification 50,000×; c and d. magnification 30,000×.

3.5. TGA analysis

The TGA curves of microcapsules are shown in Fig. 8. It can be seen that the degradation of the microcapsules consists of three main stages: 50 ∼ 100 °C is the initial weight change stage of the microcapsules, which is mainly caused by water evaporation. The second stage is at 220 ∼ 250 °C, which is analyzed due to the decomposition of dissociative chitosan and TEO [39]. At 350 ∼ 400 °C, the third stage was the main stage of weight loss for all samples, where the degradation of encapsulated TEO, chitosan, and TPP cross linked with them reduced the quality of the microcapsules.

Fig. 8.

The TGA (a) and DTG (b) curves of microcapsules.

The corresponding DTG curve also shows the maximum peak at this time. However, at this point, it can be noticed that the Tmax of microcapsules loaded with essential oil is reduced compared to empty microcapsules. This may be due to the presence of essential oil, which causes the thermal degradation temperature of the microcapsules to decrease. Some Hernández et al. [40] found that the prepared chitosan membranes loaded with oregano essential oils exhibited a lower temperature for reaching the peak rate of thermal degradation compared to a single chitosan membrane.

All in all, the thermal stability of the microcapsules loaded with essential oils was not affected compared to the unloaded ones.

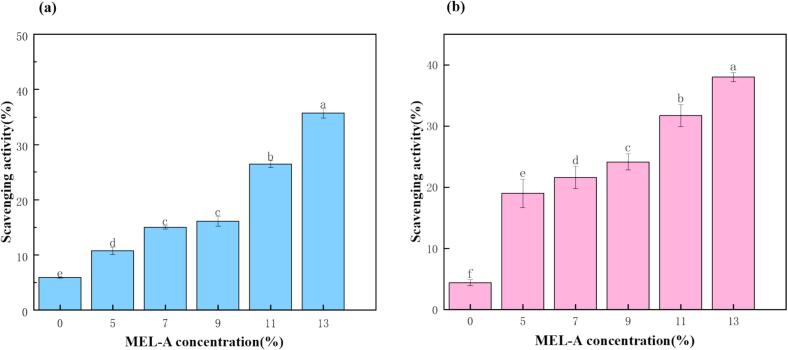

3.6. Antioxidant activity analysis

The free radical scavenging activity of microcapsules spiked with five different concentration gradients of MEL-A in DPPH system was determined [41]. It turns out that under the same reaction conditions, the antioxidant effectiveness of the microcapsules steadily grows with the rise in MEL-A concentration (Fig. 9). Compared to the control group without MEL-A, the antioxidant activity of the microcapsules is significantly improved. This is because the chitosan added during the microcapsules preparation process also possesses certain antioxidant properties. The above results illustrate that the primary source of the microcapsules' antioxidant activity is MEL-A, with chitosan also playing a certain synergistic role [42], [43]. Simultaneously, previous studies have shown that wall materials with high antioxidant properties have a positive protective effect on encapsulated essential oils [44].

Fig. 9.

Scavenging activity of microcapsules on DPPH radicals (a) and ABTS + radicals (b). Different letters indicate significant differences between each group (P < 0.05).

3.7. MIC and MBC of MEL-A against S. aureus and E. coli

To determine the antibacterial capability of the microcapsules, the inhibition rate was measured. As shown in the Fig. 10, using pure TEO as a positive control, it was observed that at a concentration of 0.49 g/mL. Apparently, microcapsules inhibit the growth of S. aureus and E. coli. Therefore, the MIC is 0.49 g/mL, and the MBC is 0.98 g/mL. Furthermore, the concentration of the microcapsules showed a favorable correlation with the inhibition rate. This finding contrasts with the conclusion of Shu et al. [5], which stated that MEL-A exhibits better antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria. It is speculated that this is due to differences in the selection of bacterial strains.

Fig. 10.

Shows the inhibition rate of microcapsules against S. aureus (a) and E. coli (b) Different letters indicate significant differences between each group (P < 0.05).

Although the article demonstrates the antibacterial and antioxidant activities of MEL-A microcapsules, the discussion on the specific mechanisms of these activities is relatively limited. For instance, how MEL-A inhibits bacterial growth by disrupting cell membranes, as well as the specific molecular mechanisms underlying its antioxidant effects, have not been thoroughly explored. Further experimental validation could be conducted in subsequent studies.

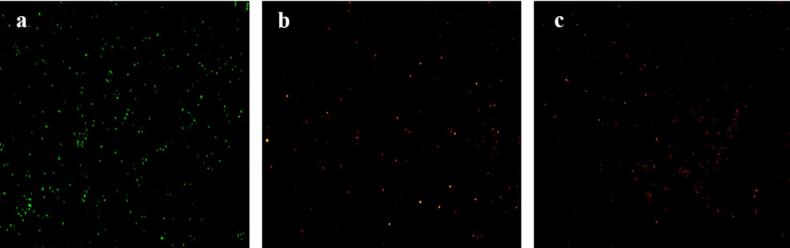

3.8. Inverted microscope analysis

The staining results of S. aureus suspensions (MIC and MBC, respectively) treated with microcapsules of TEO are shown in Fig. 11. AO/PI staining was applied to treat different bacterial suspensions for observation. Dye OA is cell membrane permeable and can penetrate the cell membrane, causing live cells to fluoresce green [24]. The dye PI, as a DNA-binding dye, does not have cell membrane permeability. It can only enter damaged cells, causing them to emit red fluorescence, and it cannot penetrate the cell membrane of living cells. Therefore, the observed fluorescence can be used to identify dead or alive cells [45].

Fig. 11.

Inverted fluorescence microscopy images of microcapsules: a. control group (without microcapsule treatment); b. MIC treatment group; c. MBC treatment group.

As shown in Fig. 11(a), most cells in the control group emit green fluorescence, indicating that the cell membranes are intact. In the MIC-treated group, a small amount of orange fluorescence is observed Fig. 11(b), suggesting partial cell membrane damage. In cells treated with MBC, the orange fluorescence increases sharply, indicating that the cell membranes have been destroyed [46]. Our findings are consistent with reports on the antibacterial effects of garlic essential oil nanoemulsions [47], indicating that essential oils and their nanoemulsions can alter cell membrane permeability and disrupt cell membrane integrity.

4. Conclusion and prospect

In the present study, microcapsules were prepared by ionic gelation method using TEO, chitosan and acetic acid as raw materials and MEL-A as emulsifier. It was found that the microcapsules with the smallest particle size and the best stability was prepared when the amount of essential oil added was 0.05 %, the concentration of TPP was 0.075 %, and the ultrasonic power intensity of 400 W/cm2. Finally, the microcapsules without added MEL-A was chosen as the control group, and the comparison of its antioxidant and bacteriostatic properties showed that the microcapsules with added MEL-A had better antioxidant and bacteriostatic properties, and provided a theoretical basis for the subsequent preservation treatment of food. Specifically, the food preservative based on TEO microcapsule can be further developed and its preservation function and antibacterial mechanism are deeply explored.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shunjie Kang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Qihe Chen: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Haorui Ma: Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Jiwei Ding: Visualization, Software, Methodology, Data curation. Changchun Hao: Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Qin Shu: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Yongfeng Liu: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by Shaanxi Science and Technology Plan Projects of China (2022KXJ-010, 2024NC-YBXM-156, 2024NC-YBXM-169), Xi’an City Science and Technology Plan Projects of China (24GXFW0008, 23KGDW0021-2022, 24NYGG0018, 2022JH-RYFW-0117), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities in China (GK202306005, GK202406001), the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12474472)

Contributor Information

Qin Shu, Email: shuqin@snnu.edu.cn.

Yongfeng Liu, Email: yongfeng200@126.com.

References

- 1.Cui H., Yuan L., Ma C., Li C., Lin L. Effect of nianoliposome-encapsulated thyme oil on growth of Salmonella enteritidis in chicken. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017;41(6) doi: 10.1111/jfpp.13299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marino M., Bersani C., Comi G. Antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of Thymus vulgaris L. measured using a bioimpedometric method. J. Food Prot. 1999;62(9):1017–1023. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-62.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dzamic A.M., Nikolic B.J., Giweli A.A., Mitic-Culafic D.S., Sokovic M.D., Ristic M.S., Knezevic-Vukcevic J.B., Marin P.D. Libyan Thymus capitatus essential oil: antioxidant, antimicrobial, cytotoxic and colon pathogen adhesion-inhibition properties. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015;119(2):389–399. doi: 10.1111/jam.12864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchese A., Orhan I.E., Daglia M., Barbieri R., Di Lorenzo A., Nabavi S.F., Gortzi O., Izadi M., Nabavi S.M. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of thymol: a brief review of the literature. Food Chem. 2016;210:402–414. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.04.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shu Q., Niu Y., Zhao W., Chen Q. Antibacterial activity and mannosylerythritol lipids against vegetative cells and spores of Bacillus cereus. Food Control. 2019;106 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Rienzo M.A.D., Stevenson P.S., Marchant R., Banat I.M. Effect of biosurfactants on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in a BioFlux channel. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;100(13):5773–5779. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Jesus Cortes Sanchez A., Hernandez Sanchez H., Eugenia Jaramillo Flores M. Biological activity of glycolipids produced by microorganisms: new trends and possible therapeutic alternatives. Microbiol. Res. 2013;168(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuoka T., Morita T., Konishi M., Imura T., Sakai H., Kitamoto D. Structural characterization and surface-active properties of a new glycolipid biosurfactant, mono-acylated mannosylerythritol lipid, produced from glucose by Pseudozyma antarctica. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007;76(4):801–810. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aranda F.J., Teruel J.A., Ortiz A. Recent advances on the interaction of glycolipid and lipopeptide biosurfactants with model and biological membranes. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;68 doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2023.101748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X., Shu Q., Chen Q., Pang X., Wu Y., Zhou W., Wu Y., Niu J., Zhang X. Antibacterial Efficacy and Mechanism of Mannosylerythritol Lipids-A on Listeria monocytogenes. Molecules. 2020;25(20) doi: 10.3390/molecules25204857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu S., Gu S., Shi Y., Chen Q. Alleviative effects of mannosylerythritol lipid-A on the deterioration of internal structure and quality in frozen dough and corresponding steamed bread. Food Chem. 2024;431 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X., Liu S., Wang Y., Shi Y., Chen Q. New insights into the antibiofilm activity and mechanism of Mannosylerythritol Lipid-A against Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e. Biofilm. 2024;7 doi: 10.1016/j.bioflm.2024.100201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mnif I., Ellouz C.S., Ghribi D. Glycolipid biosurfactants, main classes, functional properties and related potential applications in environmental biotechnology. J. Polym. Environ. 2018;26(5):2192–2206. doi: 10.1007/s10924-017-1076-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J., Chen Q., Shu Q., Liu Y. Application of a novel naturally-derived emulsifier mannosylerythritol lipid-A for improving emulsification and gel property of myofibrillar protein based on biosurfactant-protein interaction. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024;96 doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2024.103785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu J., Shu Q., Niu Y., Jiao Y., Chen Q. Preparation, characterization, and antibacterial effects of chitosan nanoparticles embedded with essential oils synthesized in an ionic liquid containing system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66(27):7006–7014. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W., Al W.M., Shu Q., Hu J., Li L., Liu Y. Enhancement effect of kale fiber on physicochemical, rheological and digestive properties of goat yogurt. LWT. 2024;207 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bashir I., Wani S.M., Jan N., Ali A., Rouf A., Sidiq H., Masood S., Mustafa S. Optimizing ultrasonic parameters for development of vitamin D3-loaded gum arabic nanoemulsions – an approach for vitamin D3 fortification. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du X.X., Ge Z.T., Hao H.S., Bi J.R., Hou H.M., Zhang G.L. An antibacterial film using κ-carrageenan loaded with benzyl isothiocyanate nanoemulsion: characterization and application in beef preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;276 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Y.a., Sun P., Duan C., Cao Y., Kong B., Wang H., Chen Q. Improving stability and bioavailability of curcumin by quaternized chitosan coated nanoemulsion. Food Res. Int. 2023;174 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu T., Liu L. Fabrication and characterization of chitosan nanoemulsions loading thymol or thyme essential oil for the preservation of refrigerated pork. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;162:1509–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q., Chen Z., Zeng L., Bi Y., Kong F., Wang Z., Tan S. Characterization, in-vitro digestion, antioxidant, anti-hyperlipidemic and antibacterial activities of Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim essential oil nano-emulsion. Food Biosci. 2023;56 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2023.103082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zielinska E., Baraniak B., Karas M. Identification of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory peptides obtained by simulated gastrointestinal digestion of three edible insects species (Gryllodes sigillatusTenebrio molitor Schistocerca gragaria) Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018;53(11):2542–2551. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge Y., Liu H., Peng S., Zhou L., McClements D.J., Liu W., Luo J. Formation, stability, and antimicrobial efficacy of eutectic nanoemulsions containing thymol and glycerin monolaurate. Food Chem. 2024;453 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.139689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong Y., Yang C., Zhong W., Shu Y., Zhang Y., Yang D. Antibacterial effect and mechanism of anthocyanin from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.974602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Álvarez Chimal R., García Pérez V.I., Álvarez Pérez M.A., Tavera H.R., Reyes C.L., Martínez H.M., Arenas Alatorre J.Á. Influence of the particle size on the antibacterial activity of green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using Dysphania ambrosioides extract, supported by molecular docking analysis. Arab. J. Chem. 2022;15(6) doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romero Pérez A., García G.E., Zavaleta M.A., Ramírez Bribiesca J.E., Revilla V.A., Hernández Calva L.M., López A.R., Cruz Monterrosa R.G. Designing and evaluation of sodium selenite nanoparticles in vitro to improve selenium absorption in ruminants. Vet. Res. Commun. 2010;34(1):71–79. doi: 10.1007/s11259-009-9335-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu C., Wang L., Hu Y., Chen S., Liu D., Ye X. Edible coating from citrus essential oil-loaded nanoemulsions: physicochemical characterization and preservation performance. RSC Adv. 2016;6(25):20892–20900. doi: 10.1039/c6ra00757k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sang Z.C., Qian J., Han J.H., Deng X.Y., Shen J.L., Li G.W., Xie Y. Comparison of three water-soluble polyphosphate tripolyphosphate, phytic acid, and sodium hexametaphosphate as crosslinking agents in chitosan nanoparticle formulation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;230 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shu X.Z., Zhu K.J. Controlled drug release properties of ionically cross-linked chitosan beads: the influence of anion structure. Int. J. Pharm. 2002;233(1–2):217–225. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal N., Maddikeri G.L., Pandit A.B. Sustained release formulations of citronella oil nanoemulsion using cavitational techniques. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;36:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dybowska B.E. The effects of temperature and homogenization pressure on flow characteristics of whey protein-stabilized O/W emulsions. Milchwissenschaft-Milk Sci. Int.. 2000;55(4):194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yadav M., Ahmad S. Montmorillonite/graphene oxide/chitosan composite: synthesis, characterization and properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015;79:923–933. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu Y., Wu T., Wu C., Fu S., Yuan C., Chen S. Formation and optimization of chitosan-nisin microcapsules and its characterization for antibacterial activity. Food Control. 2017;72:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samah B.O., Djamel T., Assia N.K., Mohamed M., Yasmina H., AbdErrahim G., Salima K.G. Chitosan nanoparticles with controlled size and zeta potential. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023;63(3):1011–1021. doi: 10.1002/pen.26261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song X., Wang L., Liu T., Liu Y., Wu X., Liu L. Mandarin (Citrus reticulata L.) essential oil incorporated into chitosan nanoparticles: characterization, anti-biofilm properties and application in pork preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;185:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.06.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng Y.C., Gardner D.J., Han Y., Kiziltas A., Cai Z.Y., Tshabalala M.A. Influence of drying method on the material properties of nanocellulose I: thermostability and crystallinity. Cellul. 2013;20(5):2379–2392. doi: 10.1007/s10570-013-0019-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashem A.H., Doghish A.S., Ismail A., Hassanin M.M.H., Okla M.K., Saleh I.A., AbdElgawad H., Shehabeldine A.M. A novel nanoemulsion based on clove and thyme essential oils: characterization, antibacterial, antibiofilm and anticancer activities. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2024;68:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbt.2023.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ines Guerra Rosas M., Morales Castro J., Araceli Ochoa Martinez L., Salvia Trujillo L., Martin Belloso O. Long-term stability of food-grade nanoemulsions from high methoxyl pectin containing essential oils. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;52:438–446. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z., Bi X., Xie X., Shu D., Luo D., Yang J., Tan H. Preparation and characterization of Iturin A/chitosan microcapsules and their application in post-harvest grape preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;275 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hernandez M.S., Luduena L.N., Flores S.K. Citric acid, chitosan and oregano essential oil impact on physical and antimicrobial properties of cassava starch films. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2023;5 doi: 10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao J.S., Cai Y.Z., Sun M., Wang G.Y., Corke H. Anthocyanins, flavonols, and free radical scavenging activity of Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra) extracts and their color properties and stability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53(6):2327–2332. doi: 10.1021/jf048312z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi M., Morita T., Fukuoka T., Tomohiro I., Kitamoto D. Glycolipid biosurfactants, mannosylerythritol lipids, show antioxidant and protective effects against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in cultured human skin fibroblasts. J. Oleo Sci. 2012;61(8):457–464. doi: 10.5650/jos.61.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu J.A., Niu Y.W., Jiao Y.C., Chen Q.H. Fungal chitosan from Agaricus bisporus (Lange) Sing. Chaidam increased the stability and antioxidant activity of liposomes modified with biosurfactants and loading betulinic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;123:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teng X.X., Zhang M., Mujumdar A.S., Wang H.Q. Garlic essential oil microcapsules prepared using gallic acid grafted chitosan: effect on nitrite control of prepared vegetable dishes during storage. Food Chem. 2022;388 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu M., Guo W., Feng M., Bai Y., Huang J., Cao Y. Antibacterial, anti-biofilm activity and underlying mechanism of garlic essential oil in water nanoemulsion against Listeria monocytogenes. LWT. 2024;196 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.115847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma H., Chen X., Zhang X., Wang Q., Mei Z., Li L., Liu Y. Transcriptomic analysis reveals antibacterial mechanism of probiotic fermented Portulaca oleracea L. against Cronobacter sakazakii and application in reconstituted infant formula. Food Biosci. 2024;58 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.103721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu M., Pan Y., Feng M., Guo W., Fan X., Feng L., Huang J., Cao Y. Garlic essential oil in water nanoemulsion prepared by high-power ultrasound: Properties, stability and its antibacterial mechanism against MRSA isolated from pork. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;90 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]