Abstract

Background—The process of proteolysis is important at several stages of the metastatic cascade. A balance between the expression of the genes encoding endogenous proteinases and inhibitors exists and when the production of proteinases exceeds that of inhibitors proteolysis occurs.

Aims—To determine whether differences in the profile and activity of proteinases and inhibitors exist within breast tumour tissue (n = 51), surrounding background breast tissue (n = 43), normal breast tissue from breast reduction mammoplasty operations (n = 10), and cells of the breast cancer cell line, MCF-7.

Methods—Proteinase (matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1), MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), and tissue-type PA (tPA)) and inhibitor (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases; TIMP-1 and TIMP-2) expression and proteinase activity were compared using substrate zymography, western blotting, immunohistochemistry, and quenched fluorescent substrate hydrolysis.

Results—The presence of all proteinases and inhibitors was greater in breast tumour tissue when compared with all other types of breast tissue (p < 0.05). The activity of total MMPs as determined by quenched fluorescent substrate hydrolysis was also greater in breast tumours (p < 0.05).

Conclusion—There is increased proteolysis in human breast tumours when compared with other breast tissues.

Keywords: breast cancer, matrix metalloproteinases, metastasis

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women; it affects one in 12 women and over 15 000 women die from breast cancer in the UK each year. Tumour invasion and metastasis formation are the primary causes of cancer treatment failure and death.1 The process of metastasis is a complex cascade of organised, sequential, interrelated steps, including angiogenesis, local invasion, intravasation, and extravasation,1 many of which require active degradation of the host tissue by proteolytic enzymes. The synthesis, secretion, and catalytic activity of proteinases appears to be tightly regulated and most are secreted as inactive zymogens.2 Highly potent natural proteinase inhibitors also exist, which limit the duration of active proteolysis. Under physiological conditions, the balance between proteolytic degradation and the regulatory inhibition of proteolysis controls normal proteolytic events—for example, tissue remodelling and wound healing. In these situations, only selective enzymes, or a cascade of functionally related proteinases, are produced in response to the signal. However, in certain pathological processes, including cancer, the balance between negative regulation and active proteolysis is disrupted so that proteolysis is no longer constrained.2,3

At least four classes of proteinases exist and they are most frequently classified according to their catalytic type.4 These are the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs or matrixins), and the serine, aspartic, and cysteine proteinases.5 The coordinated and synergistic action of these four classes of proteinases can completely degrade all extracellular matrix (ECM) components.3

Of these four classes, the matrix metalloproteinases and the serine proteinase, urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), are most extensively linked to cancer invasion and metastasis. Both the role of the MMP and PA systems in cancer and metastasis and their regulation of these processes have been reviewed previously.5–8

Proteinase expression has been studied extensively in many different human cancers, including breast cancer; however, most of these studies tend to use individual techniques to determine the synthesis of proteinases and/or inhibitors. Previous studies in breast cancer have used zymography,9–11 enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs),9,12,13 immunohistochemistry,3,14,15 and northern blot analysis,16 and have demonstrated the presence of a spectrum of proteinases and inhibitors.

We used a variety of techniques to compare proteinase (MMPs and PAs) and inhibitor (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1) and TIMP-2) expression and proteinase activity between breast tumour tissue and the corresponding background breast tissue from patients undergoing surgical resection for breast cancer, normal tissue from breast reduction mammoplasty operations, and cells of the breast cancer cell line, MCF-7. We used four techniques—substrate zymography, western blotting, immunohistochemistry, and quenched fluorescent substrate hydrolysis—to determine the presence and cellular location of proteinases and inhibitors, in addition to the overall MMP activity in the same samples.

Materials and methods

MATERIALS

Consumables were obtained from the following suppliers. Primary proteinase antibodies (Binding Site, Birmingham, UK), inhibitor antibodies, and protein standards (Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, UK), Elite Vector stain peroxidase kit, DAB substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK), and proteinase standards (TCS Biologicals, Claydon, UK). Membrane blocking agent, Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membrane, and peroxidase labelled secondary antibody (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK). Autoradiography film (Dupont, France), sodium dihydrogen orthophosphate (Fisons, Loughborough, UK), and disodium hydrogen orthophosphate (Rathburn Chemical Limited, Walkerburn, UK). Mca-Pro-Leu-Gly-Leu-Dpa-Ala-Arg-NH2, Mca-Pro-Leu-OH (Calbiochem, Nottingham, UK).

Acrylamide/bisacrylamide, 3-aminopropyltriethoxy silane (APES), ammonium persulphate, calcium chloride, Coomassie blue R-250, gelatin, glycine, Kodak GBX developer and replenisher, GBX fixer and replenisher, lauryl sulphate (sodium dodecyl sulphate, SDS), hydrogen peroxide, phosphate buffered saline (PBS), polyoxyethylene sorbitan monolaurate (Tween 20), sodium chloride, N, N, N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), trizma base, trypsin, and wide range molecular weight marker (Sigma, Poole, Dorset, UK). Xylene, methanol, calcium chloride, DPX mounting fluid, sulphuric acid, and Triton X-100 (BDH from North East Laboratory Supplies, Newton Aycliffe, UK). Alcohol— 70%, 95%, and 100% (the pharmacy at Royal Hallamshire Hospital). Gill's haematoxylin and Scott's tap water (the department of histopathology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital).

TISSUE SAMPLES

Fresh paired tumour (n = 51) and the surrounding normal (“background”; n = 43) breast tissue samples were collected in RPMI medium by a consultant histopathologist from the histopathology department, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield after surgical resection for breast cancer. Normal tissue samples were collected in RPMI medium from the Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, from patients undergoing breast reduction mammoplasty operations (n = 10).

The tissue samples were mechanically disaggregated using scalpel blades and graded needles, to yield a single cell suspension. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 750 ×g for 10 minutes. The pellet was resuspended and the viable cells counted using a haemocytometer (Neubauer; Phillip Harris Scientific, Blyth, UK). After counting, the cell pellet was re-formed and the cells resuspended in lysis buffer (0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.05 M trizma base, 0.2 M NaCl, and 0.005 M CaCl2) at a concentration of 10 × 106 cells/ml buffer.

CELL CULTURE

The breast cancer cell line MCF-7 was obtained from the Institute for Cancer Studies, Sheffield. Cells were cultured in plastic tissue culture flasks at 37°C in 5% CO2 and maintained in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and insulin.

The MCF-7 cells were grown exponentially but passaged at confluence. The spent medium was carefully pipetted off and the cells were washed in 20 ml PBS at room temperature. The cells were then detached from the flask with 0.02% EDTA in PBS for 10 minutes. Cells were counted and lysed as above.

ZYMOGRAPHY

Gelatin zymography

The tissue and cell lysates were mixed 3/1 with non-reducing sample buffer (0.5 M Tris HCl, pH 6.8, SDS, glycerol, and bromophenol blue).

Gelatin zymography was performed to determine the presence of MMP-2 (gelatinase A) and MMP-9 (gelatinase B) for all samples.17 Each tissue sample (20 μl) was run in parallel with a molecular weight marker and MMP-2 and MMP-9 protein standards (where available) on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel (7.5%) containing 0.1% gelatin as the substrate, at 200 V for one hour (mini-V 8.1; BRL Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). After electrophoresis, the gel was washed in 2% Triton X-100 for one hour at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 37°C with MMP incubation buffer (0.05 M trizma base, 0.2 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). After incubation, the gels were stained with a 0.2% (wt/vol) solution of Coomassie blue for 15 minutes and then destained (10% acetic acid and 30% methanol) for 10 minutes. Proteolytic activity was seen as clear lysis bands of degraded protein on a uniformly blue background.

Casein zymography

The presence of stromelysin 1 (MMP-3) was determined using a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide substrate gel containing 0.1% casein as the substrate.18

Collagen I zymography

The presence of interstitial collagenase (MMP-1) was determined using a substrate gel containing 0.1% collagen type I in a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel.18

Control gels for MMPs

Control gels contained either of the MMP inhibitors, 10 mM EDTA or 10 mM 1, 10 phenanthroline, in the MMP incubation buffer to confirm that the lysis bands were the result of MMPs.

Double substrate zymography for PAs

Double substrate zymography was used to determine the presence of PAs in tissue samples.18 The two substrates used were plasminogen (substrate 1) and gelatin (substrate 2). Plasminogen acts as a substrate for any PAs present in the tissue sample by cleaving plasminogen to the active enzyme, plasmin, which subsequently degrades the gelatin. The PA incubation buffer (0.25 M trizma base, pH 8.1) contained 10 mM EDTA to eliminate any gelatinase activity present in the sample.

Control gels for PAs

Each sample was also run on two control gels. The first gel contained gelatin only as substrate (any PAs present in the samples would be unable to degrade the gelatin) and the second contained the serine proteinase inhibitor PMSF in the incubation buffer to determine whether the lysis bands were the result of PAs.

Analysis of the gels

Gels were quantitated using laser densitometry. Gels were scanned and analysed using the Quantity One software (Discovery Series; Pharmacia Biotech, Milton Keynes, UK). The image of the gel was inverted to reveal dark bands on a white background. The molecular weight, area, and optical density of each band were determined. The relative amounts of the different forms of the proteinases (latent and active) were determined by multiplying the area of each band by the optical density.

WESTERN BLOTTING

Western blotting was performed on the remaining breast tissue and cell samples to determine the presence of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2.

Samples were electrophoresed on 15% polyacrylamide gels at 200 V for one hour. The electrophoresed proteins were then blotted on to a nitrocellulose membrane for one hour. The membrane was blocked and then incubated with the primary antibody (TIMP-1 or TIMP-2 mouse antihuman antibodies; 1 μg/ml anti-TIMP-1 or 5 μg/ml anti-TIMP-2) for one hour. After incubation with peroxidase conjugated antimouse IgG the membrane was developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit, exposed to autoradiography film, and then developed. The protein bands on the processed film were analysed by densitometry, as described previously.

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

Because immunohistochemistry was performed retrospectively on the breast tumour samples, no paraffin wax embedded sections were available for the background or normal tissue, or MCF-7 cells.

Immunohistochemistry was used to localise proteinase and inhibitor proteins by means of the avidin–biotin immunoperoxidase technique.19 Formalin fixed breast tumour tissue sections (4 μm thick; the department of histopathology, University of Sheffield) were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in a decreasing series of alcohol. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 2% hydrogen peroxide and the antigens were unmasked with 0.1% trypsin and then washed. Non-specific binding sites were blocked by covering the sections with normal serum—rabbit serum for proteinases and horse serum for TIMPs. Sections were then incubated with each primary antibody for one hour at room temperature. Sections were incubated sequentially with biotinylated secondary antibody (biotinylated rabbit, antisheep antibody for the proteinases and biotinylated horse antimouse antibody for the TIMPs) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The sections were washed with PBS and then incubated with avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex (ABC) for 30 minutes. Sections were washed and then covered with the DAB stain for 10 minutes until the colour reaction was revealed. The sections were counterstained with Gill's haematoxylin and mounted.

The degree of antibody staining—that is, the staining intensity and the cell type stained (tumour cells, fibroblasts, and inflammatory cells)—was determined for all samples by a consultant histopathologist (TJS) blinded to the sections.

Data analysis

The staining intensity of the different cell types within each tumour was determined and this was related to the breast tumour grade. Statistical analysis was not performed because of the small numbers within each tumour grade.

QUENCHED FLUORESCENCE SUBSTRATE HYDROLYSIS

This hydrolysis technique uses the quenched fluorescence substrate Mca-Pro-Leu-Gly-Leu-Dpa-Ala-Arg-NH2, which is cleaved by all secreted activated MMPs tested so far20 at the Gly-Leu bond, releasing the fluorescent Mca group from the internal quenching group Dpa.21 The total MMP activity was determined for each breast tissue sample by incubating 150 μl tissue sample lysate with 2835 μl assay buffer (0.1 M Tris HCl, 0.1 M NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5) and 15 μl of the fluorescent substrate (5 μM). The samples were incubated for three hours at 37°C and the MMP activity was determined using a fluorimeter (Perkin Elmer LS59B; λex 328 nm and λem 393 nm; Perkin Elmer, Beaconsfield, UK) controlled by the FLDM software. Lysis buffer (150 μl) incubated as above acted as the negative control.

The fluorimeter was standardised (maximum fluorescence was set by the addition of 0.5 μM Mca-Pro-Leu-OH) so that the absolute rate of substrate hydrolysis was determined for each sample and expressed as pM/min.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We performed χ2 analysis to compare the proportion of samples producing each proteinase and inhibitor. Proteinase and inhibitor production and total MMP activity in the different breast tissues and between grades of breast tumours were compared using ANOVA followed by Mann Whitney U test for non-parametric data, with 95% confidence limits. The data were considered to be significant at p < 0.05. The number of patients studied was not sufficient to justify statistical comparison of the amounts of proteinase and inhibitor present in the different grades of breast tumour.

Results

BREAST TUMOUR GRADE

The grade of breast tumour was known for 42 of the 51 patients with breast cancer analysed: there were seven grade 1 tumours, 21 grade 2, and 14 grade 3 tumours.

MMP-2

Gelatin zymography showed latent MMP-2 (72 kDa) to be present in all breast tissue samples (100%)—tumours, background samples, normal tissue, and MCF-7 cells. However, active MMP-2 (68 kDa) was found in a significantly greater number of breast tumour samples (p < 0.05; 100%) than any other breast tissue (49% of background samples, 50% of normal tissue, and 0% of MCF-7 cells) and in greater amounts (table 1 ▶).

Table 1.

Differences in proteinase and inhibitor production and MMP activity in the different breast tissues (median (range))

| Breast tumours (n = 51) | Background breast (n = 43) | Normal breast (n = 10) | MCF-7 cells (n = 10) | |

| MMP-9 | ||||

| Latent | 0–33.6 (10.5) | 0–24.9 (6.6) | 0–12.6 (7.8) | 0–23.4 (4.5) |

| Active | 0–23.5 (11.6)* | 0–7.6 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0–70.6 (12.0) | 0–24.7 (7.1) | 0–12.6 (7.8) | 0–23.4 (4.5) |

| MMP-2 | ||||

| Latent | 0.3–20.46 (5.7) | 0.2–18.9 (3.2) | 1.8–14.4 (6.8) | 3.3–26.3 (8.5) |

| Active | 0–34.2 (5.3)* | 0–11.8 (0) | 0–1.1 (0.25) | 0 |

| Total | 0.3–52.0 (8.3) | 0.2–12.1 (3.6) | 2.9–15.4 (7.1) | 3.3–26.3 (8.5) |

| MMP-3 | ||||

| Latent | 0–9.2 (5.0)* | 0–3.7 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Active | 0–27.7 (0) | 0–17.6 (0) | 0–7.7 (2.13) | 0 |

| Total | 0–31.4 (4.0)* | 0–17.6 (0) | 0–7.7 (2.13) | 0 |

| MMP-1 | ||||

| Latent | 0–2.6 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Active | 0–3.3 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0–5.9 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| uPA | 0–56.0 (6.9) | 0–16.0 (1.5) | 0–7.3 (5.2) | 0 |

| TIMP-1 | 0–224.2 (6.0) | 0–24.3 (1.6) | – | 0 |

| TIMP-2 | 3.1–36.5 (11.7) | 0–26.4 (7.7) | – | 0 |

| RSH | 0–8325.0 (808.4)* | 0–2245.0 (225.1) | 6.4–2763.6 (278.7) | 81.5–621.8 (468.2) |

For proteinases and inhibitors, the values are arbitrary units (OD × area of band).

For RSH (rate of substrate hydrolysis) the units are pM/min.

MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; OD, optical density; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator.

*p < 0.05, ANOVA, Mann Whitney, tumour versus other breast tissues

Immunohistochemical staining of MMP-2 within breast tumour samples was greater in tumour cells than in either fibroblasts or inflammatory cells (data not shown).

MMP-9

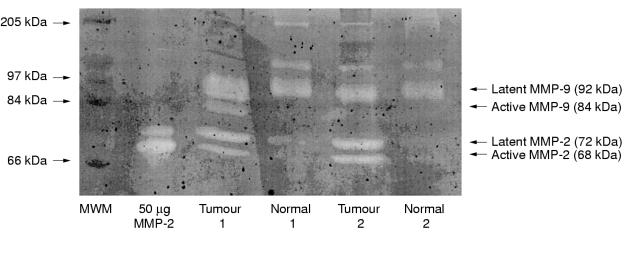

Gelatin zymography showed that latent MMP-9 was present in 100% breast tumour samples, 93% of background samples, 100% of normal tissues, and 100% of MCF-7 cells. However, active MMP-9 was found significantly more frequently and in significantly greater amounts (table 1 ▶) in breast tumours (78%) than in any other breast tissue (7% of background samples, 0% of normal tissues, 0% of MCF-7 cells). Figure 1 ▶ shows a representative gelatin zymogram demonstrating the differences in gelatinase detection between paired breast tumour and background breast tissue samples.

Figure 1.

Gelatin zymogram demonstrating the gelatinolytic activity of two paired breast tumour and background tissue samples. Lane 1, molecular weight marker (MWM); lane 2, matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) protein control; lanes 3–6, the tissue samples. The latent forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were found in both tumour and background breast tissues; however, the active forms of these enzymes were only found in the tumour tissue of these paired samples.

Immunohistochemical staining of MMP-9 was low for all cell types.

MMP-3

Casein zymography demonstrated a band migrating at 57/59 kDa (corresponding to latent MMP-3) in a significantly greater proportion of breast tumour samples (73% of tumours, 16% of background samples, 0% of normal tissues, and 0% of MCF-7 cells), and in significantly greater amounts than any other tissue studied (p < 0.05; table 1 ▶). A band migrating at 45 kDa (corresponding to active MMP-3) was seen in 41% of tumours, 19% of background samples, 50% of normal tissue, and 0% of MCF-7 samples. Immunohistochemical staining of MMP-3 was low for all cell types.

MMP-1

Substrate zymography demonstrated MMP-1 in breast tumour tissue only, and in only 22% of the tumour samples analysed. In addition, immunohistochemical staining of MMP-1 was low for all cell types.

Upa

After double substrate zymography a lysis band migrating at 54 kDa (corresponding to uPA) was seen in 90% of breast tumours, 56% of background samples, 83% of normal breast tissue, and 0% of MCF-7 cells. uPA production was significantly greater in tumour tissue than in the other breast tissues (p < 0.05; table 1 ▶). Immunohistochemical staining of uPA was of moderate intensity for tumour cells and fibroblasts but low for inflammatory cells.

TISSUE-TYPE PA (Tpa)

No lysis band migrating at 70 kDa was seen in any tissue sample after double substrate zymography; however, this is probably attributable to the tissue disaggregation technique used. Immunohistochemical staining of tPA was low for all cell types.

TIMP-1

Western blotting detected TIMP-1 in 82% of tumours, 50% of background samples, and 0% of MCF-7 cells (p < 0.05). We could not determine the presence of TIMP-1 in normal breast tissue because of a lack of samples. Immunohistochemical staining of TIMP-1 was high in tumour cells, moderate in fibroblasts, and low in inflammatory cells.

TIMP-2

TIMP-2 was assessed only in the small proportion of remaining tissue samples. However, of those samples studied, TIMP-2 was detected in 100% of tumours, 80% of background samples, and 0% of MCF-7 cells. Immunohistochemical staining of TIMP-2 was high in tumour cells, moderate in fibroblasts, and low in inflammatory cells.

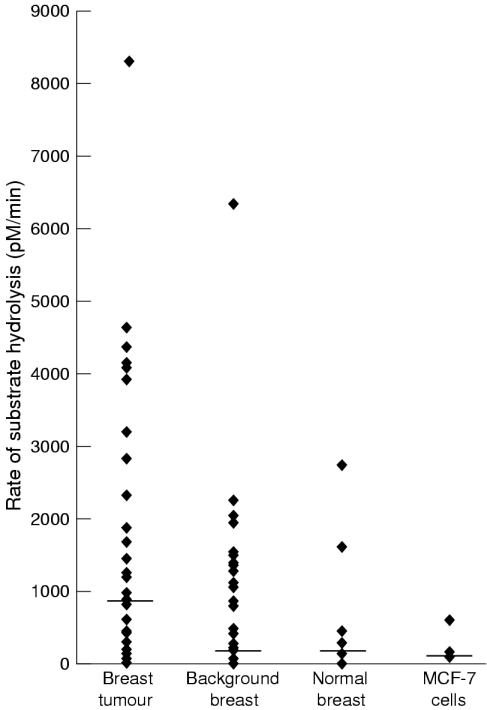

RATE OF SUBSTRATE HYDROLYSIS

The rate of substrate hydrolysis (MMP activity) varied considerably both between tissue samples from the same group and between the different breast tissues (table 1 ▶; fig 2 ▶). The rate of substrate hydrolysis was significantly greater (p < 0.05) in breast tumour tissue than any other breast tissue. In 86% (32 of 37) paired tumour and background breast tissue samples, the rate of substrate hydrolysis (and therefore MMP activity) was greater in the tumour tissue.

Figure 2.

Graph demonstrating the differences in total matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity (rate of substrate hydrolysis) in the different breast tissues studied. The horizontal line corresponds to the median activity for each tissue. Breast tumour tissue had significantly greater MMP activity than the other breast tissues studied (background samples, normal tissue, and MCF-7 cells; ANOVA, p < 0.05, Mann Whitney).

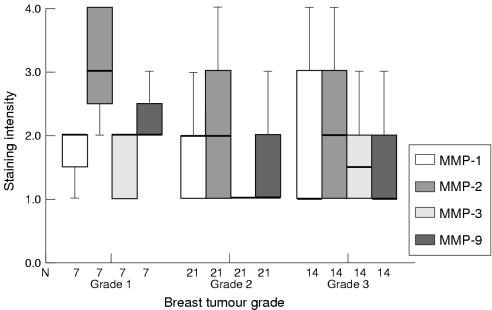

PROTEINASES, INHIBITORS, AND BREAST TUMOUR GRADE

The results of zymography indicated that the amounts of MMP-2 and MMP-9 present correlated positively with breast tumour grade; however, no differences were seen for MMP-1, MMP-3, or uPA. According to western blotting, amounts of TIMP correlated inversely with tumour grade.

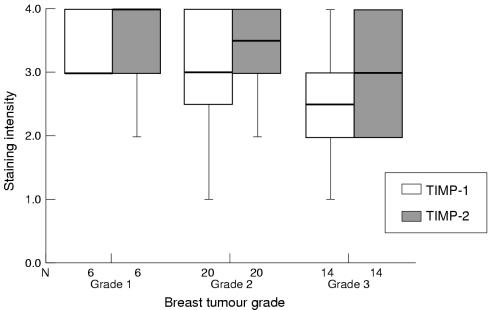

Immunohistochemistry demonstrated associations between the grade of tumour and the staining intensity of MMPs (fig 3 ▶) and TIMPs (fig 4 ▶); however, some associations conflicted with zymography and western blotting results. No obvious associations were seen between staining intensity of PA and breast tumour grade.

Figure 3.

Box plot showing differences in tumour cell staining intensity (by means of immunohistochemistry) of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1), MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 (median and interquartile range) according to breast tumour grade. The line within the box plot represents the median value.

Figure 4.

Box plot showing differences in tumour cell staining intensity (by means of immunohistochemistry) of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1) and TIMP-2 (median and interquartile range) according to breast tumour grade. The line within the box plot represents the median value.

There was no correlation between total MMP activity, as determined by quenched fluorescence substrate hydrolysis, and the breast tumour grade.

Discussion

Previous studies have determined proteinase and inhibitor synthesis in breast cancer using different techniques including zymography,9,10 immunohistochemistry,3,14 ELISA,9 and in situ hybridisation.3,16 However, these previous studies have measured individual proteinases or inhibitors and have usually used a single technique only. To gain an increased understanding of the role of proteinases in breast cancer, we need to know where they are processed (and activated), their cellular localisation, the different forms of each proteinase produced, and whether the proteinases are complexed with the appropriate proteinase inhibitors.

In our study, tissue samples were mechanically disaggregated and cells were counted and lysed; therefore, any differences in the presence of proteinases and inhibitors between samples were the result of differences in the relative proportions of cells—for example, tumour cells compared with stromal cells and/or the tissue's ability to produce, secrete, or activate these factors. Therefore, differences will not be the result of differing cell numbers, as may be the case if tissue is homogenised. The disadvantage of using cell lysates rather than solid tissue homogenates to determine proteinase expression is that the results are likely to be biased towards secreted proteinases, such as MMP-9, and those that have cell surface receptors, such as MMP-2 and uPA. It is unlikely that proteinases bound to the ECM (for example, tPA) will be identified by this method.

We used four different techniques in our study: zymography for proteinase detection; western blotting for inhibitor detection; immunohistochemistry for the cellular localisation of proteinases and inhibitors; and quenched fluorescence substrate hydrolysis to determine the total MMP activity within samples.

Our study described the presence of multiple proteinases in normal and malignant breast tissue. The production of proteinases and inhibitors and the total MMP activity tended to be greater in tumours than in any other breast tissue.

The most pronounced difference was seen using gelatin zymography, where significantly greater amounts of the active forms of both MMP-2 and MMP-9 were found in tumours than in any other breast tissue. Amounts of MMP-2 and MMP-9 appeared to correlate with breast tumour grade, although numbers were small, and this may reflect differences in the secretion, synthesis, and activation of the gelatinases and therefore their involvement at the different stages of tumour progression and metastasis.

Previous studies using gelatin zymography have also reported increased amounts of latent MMP-9, latent MMP-2, and active MMP-2 in breast tumour tissue compared with normal breast; however, the production of active MMP-9 was lower than in our study.9–11 Other groups have detected gelatinases in patients with breast cancer using ELISA,12 northern blotting,16 and immunohistochemistry.3,14,15 Both our study and a previous study detected MMP-2 preferentially in tumour cells using immunohistochemistry.3 In contrast, MMP-2 mRNA expression was found in the stromal cells close to the invasive cancer cells.16 No previous correlations between gelatinase production and breast tumour grade have been observed.11 Possible reasons for discrepancies in gelatinase detection between published studies are the different tissue disaggregation techniques used, the area and size of tumour analysed, and the numbers of samples involved.

Few studies have determined the presence of MMP-1 and MMP-3 in breast tissue.9,16,22 We found the presence of MMP-3 was greater in breast tumours than in any other breast tissue. However, the staining intensity of MMP-3 using immunohistochemistry was low for all cell types. Previously, the presence of MMP-3 has been demonstrated in tumour cells3 and fibroblasts.22

MMP-1 was the least frequently detected MMP; using zymography, MMP-1 was detected in only a few tumour samples and no other breast tissues, consistent with previous studies.9 Immunohistochemical staining of MMP-1 was low for all cell types, as described previously.3,22

The only PA detected in breast tissue was uPA, with significantly greater amounts found in the tumours than the other breast tissues, confirming previous studies.23,24 The presence of high amounts of uPA in breast cancer has been associated with shorter disease free survival,5,25,26 increased recurrence, and death,23,24 and hence an increased tumour associated uPA has become an independent prognostic marker. The absence of tPA on substrate gels may reflect the tissue disaggregation technique used in our study. Immunohistochemistry detected low staining of tPA and moderate staining of uPA in all cell types.

Greater staining intensity of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 than any proteinase was detected by means of immunohistochemistry, which is consistent with a previous study where TIMP-1 was detected more frequently than any MMP, and it was detected in all cell types.3 Amounts of TIMP correlated inversely with breast tumour grade; a previous study correlated increased amounts of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 with distant metastasis.27

We did not determine the presence of the PA inhibitors PAI-1 and PAI-2; therefore, it is not known whether an imbalance occurs in the PA system.

The presence of proteinases and inhibitors was found to be upregulated in breast tumour tissue compared with other breast tissues; however, the most important determinant for proteolysis in vivo is the balance between the production and activation of proteinases and the production of their inhibitors. Quenched fluorescence substrate hydrolysis determined the amount of free active MMPs present within the tissue samples. This is indicative of proteolysis occurring in vivo and has not been determined previously in the different breast tissues. In breast tumours, the total MMP activity was significantly greater than in the other breast tissues; however, all tissues (background samples, normal tissue, and MCF-7 cells) did have some MMP activity, implying that MMPs are involved in normal tissue remodelling of the breast. The presence of the active forms of MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 was also greater in breast tumour tissue and would therefore contribute to the increased activity. This increased MMP activity may be relevant for tumour invasion and metastasis. There was a trend for increased MMP activity to correlate inversely with breast tumour grade, which is in contrast to that found for the individual MMPs; however, the numbers of samples for each tumour grade were not equivalent. Another possible explanation is that the fluorescent substrate was cleaved by MMPs other than those studied, but which are also thought to be involved in tumour progression—for example, MMP-7 and MMP-11.28

Significantly lower amounts of proteinases and inhibitors were present in MCF-7 cells than in breast cancer tissue and there are a number of possible explanations for this. First, the MCF-7 cell line is not a highly invasive or metastatic cell line and, because MMPs are thought to be required for these processes, MCF-7 cells may therefore not require high amounts of MMPs. Second, it has been reported that most MMPs are derived from stromal cells rather than tumour cells,29 with the occasional exception—for example, matrilysin.30 Therefore, MCF-7 cells would not be expected to produce high amounts of MMPs because they are derived from a pure tumour cell culture. Finally, MMPs are secreted in a latent form and require activation extracellularly to become activated. Because the MCF-7 cells were lysed, so that all cells and tissues were disaggregated in the same way, only a minimal amount of active MMP would be present, because the active MMPs, if present, would be in the medium.

In summary, the main difference seen in proteolysis in breast tissue was the degree of activation of MMPs, particularly MMP-2 and MMP-9, and the total MMP activity, all of which were upregulated in tumour tissue. This increased MMP activity might result in increased proteolysis and therefore tumour progression and metastasis in vivo.

References

- 1.Liotta LA, Steeg PS, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Cancer metastasis and angiogenesis: an imbalance of positive and negative regulation. Cell 1991;64:327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Testa JE, Quigley JP. The role of urokinase type plasminogen activator in aggressive tumour cell behaviour. Cancer Metastasis Rev 1990;9:353–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clavel C, Polette M, Doco M, et al. Immunolocalisation of matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitor in human mammary pathology. Bull Cancer (Paris) 1992;79:261–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett AJ. Classification of peptidases. Methods Enzymol 1995;244:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitt M, Janicke F, Graeff H. Tumour associated proteases. Fibrinolysis 1992;6:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baramova E, Foidart JM. Matrix metalloproteinase family. Cell Biol Int 1995;19:239–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cawston TE. Metalloproteinase inhibitors and the prevention of connective tissue breakdown. Pharmacol Ther 1996;70:163–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwaan HC. The plasminogen–plasmin system in malignancy. Cancer Metastasis Rev 1992;11:291–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remacle AG, Noel A, Duggan C, et al. Assay of matrix metalloproteinases types 1, 2, 3 and 9 in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1998;77:926–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown PD, Bloxidge RE, Anderson E, et al. Expression of activated gelatinase in human invasive breast carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis 1993;11:183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies B, Miles DW, Happerfield LC, et al. Activity of type IV collagenases in benign and malignant breast tissue. Br J Cancer 1993;76:1126–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duffy MJ, Blaser J, Duggan C, et al. Assay of matrix metalloproteases types 8 and 9 by ELISA in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1995;71:1025–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zucker S, Lysik RM, Zarrabi MH, et al. Mr 92,000 type IV collagenase is increased in plasma of patients with colon cancer and breast cancer. Cancer Res 1993;53:140–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteagudao C, Merino MJ, San Juan J, et al. Immunochemical distribution of type IV collagenase in normal, benign and malignant breast tissue. Am J Pathol 1990;136:585–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwata H, Kobayashi S, Iwasw H, et al. The expression of MMPs and TIMPs in human breast cancer tissues and importance of their balance in cancer invasion and metastasis [abstract]. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine 1995;53:1805–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polette M, Clavel C, Cockett M, et al. Detection and localisation of mRNAs encoding matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors in human breast pathology. Invasion Metastasis 1993;13:31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heussen C, Dowdle EB. Electrophoretic analysis of plasminogen activators in polyacrylamide gels containing sodium dodecyl sulfate and copolymerised substrates. Anal Biochem 1990;102:196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seftor REB. Electrophoretic analysis of proteins associated with tumour cell invasion. Electrophoresis 1994;15:454–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H. The use of avidin–biotin–peroxidase complec (ABC) in immunoperoxidase technique. A comparison between ABC and unlabelled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem 1981;29:577–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown CJ, Rahman S, Morton AC, et al. Inhibitors of collagenase but not gelatinase reduce cartilage explant proteolglycan breakdown despite only low levels of matrix metalloproteinase activity. J Clin Pathol: Mol Pathol 1996;49:M331–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight CG, Willenbrock F, Murphy G. A novel coumarin-labelled peptide for sensitive continuous assays of the matrix metalloproteinases. FEBS Lett 1992;296:263–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heppner KJ, Matrisian LM, Jensen RA, et al. Expression of most matrix metalloproteinase family members in breast cancer represents a tumour-induced response. Am J Pathol 1996;149:273–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janicke F, Schmitt M, Pache L, et al. Urokinase (uPA) and its inhibitor PAI-1 are strong prognostic factors in node negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1993;24:195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouchet C, Spyratos F, Martin PM, et al. Prognostic value of urokinase type plasminogen activator (uPA) and plasminogen activator inhibitors PAI-1 and PAI-2 in breast carcinomas. Br J Cancer 1994;69:398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duffy MJ, Reilly D, O'Sullivan C, et al. Urokinase plasminogen activator and prognosis in breast cancer. Lancet 1990;335:108–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duffy MJ. Urokinase type plasminogen activator and malignancy. Fibrinolysis 1993;7:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ree AH, Florenes VA, Berg JP, et al. High levels of messenger RNAs for tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1 and TIMP-2) in primary breast carcinomas are associated with development of distant metastases. Clin Cancer Res 1997;3:1623–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liabakk NB, Talbot I, Smith RA, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) type IV collagenases in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1996;56:190–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacDougall JR, Matrisian LM. Contributions of tumour and stromal matrix metalloproteinases to tumour progression, invasion and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 1995;14:351–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf C, Rouyer N, Lutz Y, et al. Stromelysin-3 belongs to a sub group of proteinases expressed by breast carcinoma fibroblastic cells and possibly implicated in tumour progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993;90:1843–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]