Abstract

The current article systematically reviews the literature and provides results from 36 studies testing the relation between pubertal stage and depression, as well as moderators and mediators of this relation. Results indicate that there is a significant relation between advancing pubertal stage and depression among girls, and this effect is strongest among White girls. Among boys, risk for depression does not increase with pubertal stage. Importantly, gonadal development appears to be driving the pubertal stage effect. Increasing hormone concentrations, shared environmental stressors, and body esteem appear to be mechanisms of this relation; increases in nonshared environmental stressors (negative life events, peer victimization) moderate the relation between pubertal stage and depression. Inconsistencies in findings across studies can be explained by methodological differences. Future work on this topic should control for age, examine differences by sex, and utilize within-person analyses to evaluate the effect of pubertal stage on depression over time.

Keywords: Puberty, Depression, Adolescence, Sex differences

Introduction

One of the most robust findings in the depression literature is the gender gap in prevalence: women are nearly twice as likely to experience depressive symptoms or meet diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode than men [1, 2]. Rates of depression are nearly equal between boys and girls during childhood, but by adolescence, girls are twice as likely as boys to be depressed [3]. This gender gap emerges around age 13, increases in magnitude across adolescence, persists across the remainder of the lifespan, and is evident across nationalities and cultures [3–5]. Further, this gap is presumed to be a result of increases in rates of depression among women, whereas rates for men remain relatively stable [6]. Notably, the timing of the emergence of this gender gap coincides with the average age of onset of puberty [7]. As a result, it has been hypothesized that pubertal processes play a role in the emergence of the gender gap in depression. Indeed, a vast literature has attempted to delineate the role of puberty in the adolescent increase in depression. However, issues with the measurement of pubertal development and terminology used to describe variation in different pubertal processes have made it difficult to draw clear conclusions and gain a comprehensive understanding of how and why puberty appears to contribute to the preponderance of depression among women. One important question from this research is whether the process of becoming pubertally mature, or simply advancing through puberty, regardless of the timing, tempo, or synchrony of development, can help explain the gender gap in depression. And if so, why?

It is evident that pubertal timing, tempo, and synchrony all confer risk for depression among adolescents [8–10]. However, studying these phenomena assumes that there is a “typical” course of pubertal development—an average age of onset, average rate of tempo, and average degree of synchrony that occurs among youth. But, the facts that rates of depression increase after puberty, primarily among girls, and that the gender gap in depression persists long after puberty is over, suggest that there is something about the changes that result from pubertal development itself that confer risk for depression, particularly for women. Understanding the effect of this normative developmental process is integral to understanding this dramatic increase in depression during adolescence, and perhaps, the gender gap in depression. Furthermore, it is plausible that the mechanisms of risk differ depending on which pubertal construct is assessed. For example, pubertal timing may confer risk via different mechanisms than pubertal stage; pubertal tempo maybe confer risk via different processes than synchrony. Perhaps understanding how and why normative pubertal development confers vulnerability to depression can better inform our investigation of timing, tempo, and synchrony as risk factors.

What is Puberty?

Puberty is a sex-dependent process by which humans develop into sexually mature adults, capable of reproduction. The biological process of puberty is induced by the hypothalamic-pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis and is accompanied by a host of hormonal and morphological changes. This process consists of two distinct but related processes: adrenarche and gonadarche [11]. First, around ages 6–8 in girls and about one year later in boys, the adrenal glands begin to mature and release adrenal androgens (e.g. dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA] and its sulfate [DHEAS]). This rise occurs through the third decade of life and, once concentrations reach high enough levels, is responsible for the growth of ancillary and pubic hair [12, 13]. This process is called adrenarche and is thought to be responsible for the initiation of gonadarche. During gonadarche, the hypothalamus stimulates secretion of Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the pituitary gland to release gonadotropins (luteinizing hormone [LH] and follicle stimulating hormone [FSH]). Increasing levels of LH and FSH lead to the production of estradiol and testosterone by the ovaries and testes, respectively. Finally, the increase in estradiol and testosterone induce morphological changes (e.g. growth of sex organs like ovaries and testes and external changes like breast and genital development), and ultimately, menarche in girls. These external morphological changes typically are assessed using Tanner Staging, which assesses the growth of secondary sexual characteristics and classifies growth into five stages [14]. In addition to the growth of secondary sex characteristics, puberty is accompanied by rapid height and weight changes, as well as neural and cognitive development.

Moreover, the pattern of the relationship between hormonal and morphological changes differs by sex. Among girls, most morphological development occurs in the first half of puberty, during the most rapid increase in hormones (Tanner stages 1–3), prior to the onset of menarche (around Tanner stage 4). For boys, there is a longer period of hormonal development before morphological changes are evident [15]. The average age of onset of puberty (e.g. onset of morphological changes) among girls is 9–10 years old, and the average age at menarche is about 12 years old [16]. The average age of onset of puberty in boys is 11 years old [17]. However, there is significant variability in the age of onset, synchrony, and duration of pubertal development [10, 18, 19].

Terminology and Measurement

There are four widely-studied objective measures used to capture variability in different facets of pubertal development: (1) Pubertal stage or status refers to what stage in development an individual is in at a given point in time; (2) Pubertal timing refers to the level of development an individual has achieved compared to his or her same-aged peers or the age by which a particular milestone is reached (e.g. age at menarche); (3) Pubertal tempo refers to the rate at which one advances through the stages of development; and (4) Pubertal synchrony refers to the degree to which the hormonal and physical processes are synchronized within the individual [15]. It is also worth noting that there have been secular trends toward earlier pubertal development over the past century, which may contribute to increases in rates of psychopathology [20].

Given its developmental, dynamic nature, measuring pubertal processes can be complicated. As the focus of this review is on pubertal stage and depression, this section will review issues relevant to the measurement of pubertal stage (see reference [21] for a review of the measurement of timing, tempo, and synchrony). The extant literature primarily has used four methods to assess pubertal stage: self-report (e.g. Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; [22]) or Tanner Stages [18, 23], physical exam to assess Tanner Stage, hormonal assays (e.g. estradiol, testosterone, LH, FSH, DHEA), and presence vs. absence of menarche (in girls). Self-report and physical exam measures can assess a range of changes, including voice changes, hair growth, genital growth, height changes, and breast growth, and categorize youth into a stage of development (PDS: stages 1–4, Tanner: stages 1–5). Whereas the PDS asks questions about various aspects of development, self-reports of Tanner stages often are assessed using a two-item measure that includes five photographs of breast and pubic hair development for girls and genital and pubic hair development for boys [23].

It is important to interpret findings in light of the way that puberty is assessed. For example, using hormonal assays of estradiol, testosterone, LH, and FSH or self-report on breast growth, genital growth, or menarcheal status speaks to how advanced an adolescent is in gonadarche. On the other hand, self-reported ancillary or pubic hair, or hormonal assays of DHEA are relevant to how advanced an adolescent is in adrenarche. Self-report measures tend to include reports of pubic or ancillary hair and other secondary sex characteristics to offer a wholistic view of overall pubertal development and have been shown to be correlated with levels of hormones [24]. Some studies opt to include just a single indicator from these measures in their analyses to reflect a single pubertal process.

It is important to note that although self-report measures of pubertal development are related to hormone levels, there is no set hormone level/range that clearly maps onto pubertal stage. Pubertal hormones advance pubertal maturation, but individual differences unrelated to puberty influence levels of circulating hormones. Hormone levels fluctuate throughout the day, there are individual differences in the level of a hormone needed to advance puberty, and there is overlap in hormone levels across each pubertal stage [24, 25]. Thus, using hormone levels to assess relative pubertal timing or stage within a sample can be problematic, and results should be interpreted with this limitation in mind.

Inasmuch as pubertal stage is defined as one’s level of development at a specific point in time, the study of the association between pubertal stage and depression lends itself to cross-sectional analyses. An effort to investigate the effect of pubertal stage prospectively, through a developmental lens, has led many researchers to design longitudinal studies that examine pubertal stage predicting depressive symptoms or diagnoses at a later time point [26–30]. However, this design confounds the measurement of pubertal stage with pubertal timing and tempo. In other words, it assesses the level of pubertal development compared to one’s same aged peers at one point in time (pubertal timing). Further, as discussed, youth move through puberty at different rates (pubertal tempo), and this design captures where youth are developmentally compared to their same aged peers and does not account for change that could occur between assessments. Similarly, other studies have tried to resolve this problem by computing a change score in pubertal stage between two time points as a predictor of depression at the second time point [31]. However, because the time between assessments is presumably the same for all participants, youth with more rapid pubertal tempo will have higher change scores. Thus, this design does not adequately tease apart the effects of normative pubertal development and pubertal tempo.

One final issue to consider in the measurement of pubertal stage and its association with depression is the effect of age. Pubertal development and age are highly correlated; however, age progresses in a linear fashion, whereas there is variability in the age of onset and duration of pubertal development [18, 19]. The trajectory of depression by age across adolescence has been well-documented and replicated in the literature [4, 32]. In order to tease apart the independent contributions of age versus pubertal stage on depression, age should be controlled for when investigating the role of pubertal stage in depression.

The Present Study

The current study systematically reviewed and critiqued the literature on the relation between pubertal stage and depression. Additionally, given the evidence for a gender gap in depression that emerges at the same time as pubertal onset and persists across the life span, it also summarized findings with regard to sex differences in this association, as well as other moderators and mediators. In other words, we answered the following questions: (1) Is there consistent empirical support for the idea that progression through puberty is associated with greater risk for depression?; (2) Is the relation between pubertal stage and depression more consistent for girls?; (3) Who is at the greatest risk for depression (what are significant moderators of this relation)?; and (4) Why (what are significant mediators of this relation)?

Methods

This review focused on the relation between pubertal stage or status and depressive symptoms or diagnoses and followed guidelines outlined by the PRISMA statement. Two online databases were searched on September 11, 2019 and October 20, 2019. Databases searched were PsycINFO and PubMed. Search terms included “pubertal stage + depression,” “pubertal status + depression,” “pubertal development + depression,” and “pubertal hormones + depression.” Results from the search were inclusive of related terms, including alternative terms for depression (e.g. internalizing, depressive) and pubertal (e.g. puberty, developmental, hormonal). This search was supplemented with a manual review of citations in articles that were retrieved to be sure that all relevant articles were included. A supplemental review was conducted on June 17, 2020 to check for new articles published since October 20, 2019. No additional articles that met criteria for the present review were identified. The search and review of the articles was conducted by the first author only.

Inclusion criteria were (1) the article was a peer-reviewed empirical study, (2) the article tested the effect of pubertal stage/status on depressive symptoms, depression diagnosis, or a related construct (e.g. negative affect, internalizing problems), (3) the study used an appropriate and valid assessment of pubertal stage (e.g. self-report measures, hormonal assays, physician ratings); studies assessing pubertal timing, tempo, or synchrony were not included unless they also reported analyses with pubertal status. Articles were excluded if (1) they were review articles or meta-analyses, (2) they only reported results from models assessing the effect of pubertal timing, tempo, or synchrony, or (3) they only reported analyses that tested pubertal stage/status as a predictor of depression at a later time point; if they reported both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, they were included. Studies were not excluded based on the age of participants or comorbidities in the study sample. Importantly, studies that included pubertal stage/status as a moderator of the relation between some other variable and depression were included. An interaction between X and Y predicting Z can be interpreted such that X moderates the relation between Y and Z or such that Y moderates the relation between X and Z; mathematically these are identical [33]. Therefore, results from these studies can be interpreted as the relation between pubertal stage/status and depression at varying levels of the other variable in the interaction term.

Results

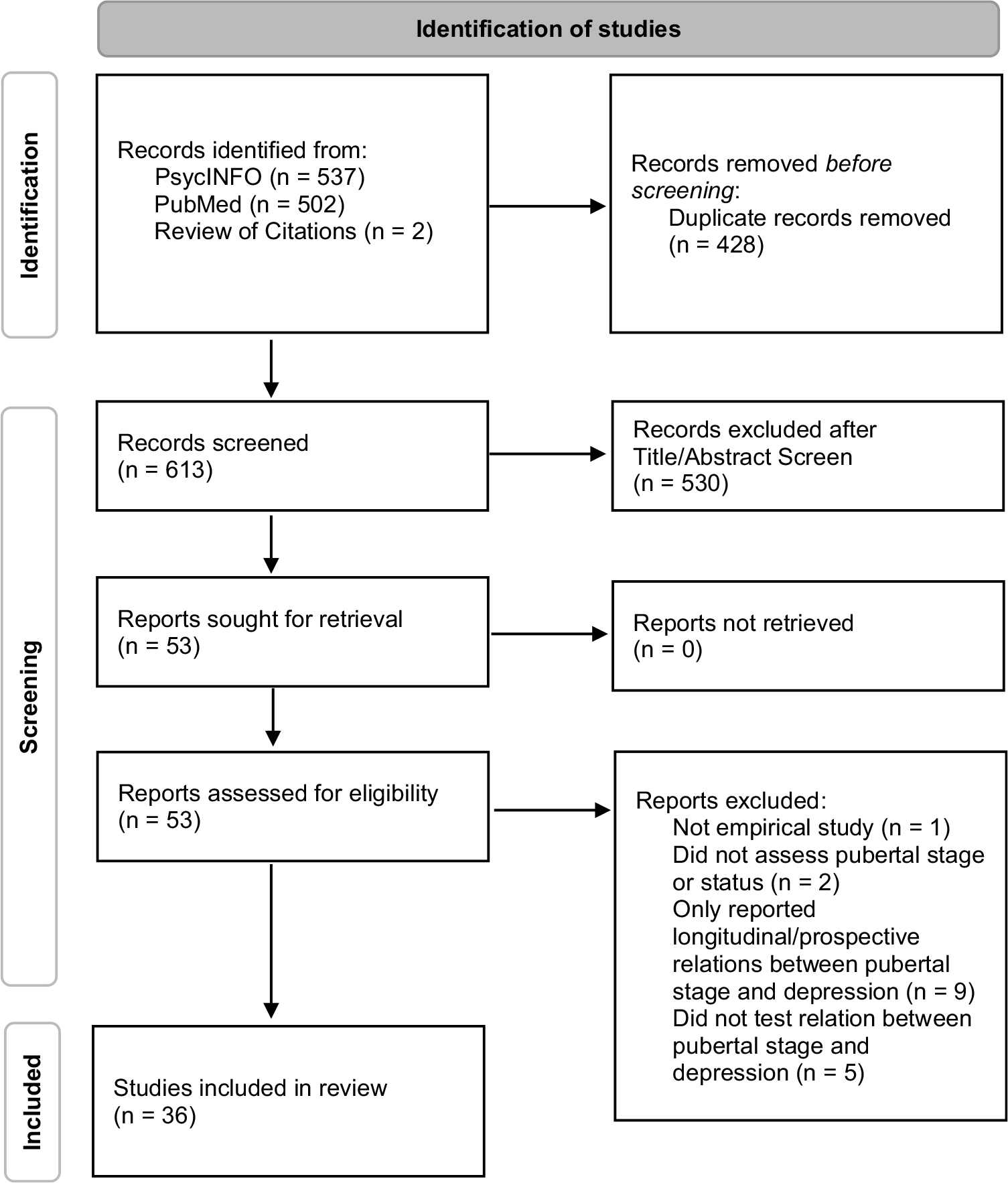

Figure 1 depicts a PRISMA flow diagram of the number of studies identified for the current review, the number excluded, and the number included. The searches in PsycINFO and PubMed yielded 537 and 502 articles, respectively (1039 total), and two additional articles were identified via a review of references in the articles that were retrieved. After duplicate citations were removed, there were 613 unique articles. The first author reviewed the titles and abstracts of these articles; based on the criteria above, most articles (N = 560) clearly did not meet inclusion criteria for the current review because they did not include measures of pubertal stage or status and depression. The remaining 53 articles were read in full to determine their eligibility. Thirty-six articles met eligibility criteria and were included in the present review (Table 1). One article was excluded because it was not an empirical study; 11 articles were excluded because they did not assess pubertal stage or status (two did not conceptualize their measurement as stage/status; nine did conceptualize their measurement as stage/status, but only reported longitudinal/prospective models); and five were excluded because they did not test the relation between pubertal stage or status and depression.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram depicting the number of studies identified for the current review, the number excluded, and the number included

Table 1.

Description of studies included in the systematic review

| Author & year | Sample | Measures | Moderators/Mediators | Tested differences by sex? | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Studies not controlling for age | |||||

| Angold, Costello, Erklani, & Worthman, 1999 [32] | 465 girls aged 9, 11, or 13 at baseline (Great Smoky Mountains Study); used data from 3 annual waves | Pubertal stage: Self-reported Tanner staging (categorized as Stage I/II and III/IV), hormones (testosterone, oestradiol, FSH, LH); Depression: CAPA | Mediator: hormones | No | In independent models, Tanner stage, testosterone, and oestradiol all significantly predicted depression; when entered into the same model, only testosterone & oestradiol were significant predictors; the effect of testosterone was non-linear, such that youth above the 60th percentile were more likely to have depression |

| Canals, Marti-Henneberg, Fernandez-Ballart, and Domenech, 1995 [34] | 507 Spanish youth (N = 334 boys and N = 235 girls); girls were 11 years old at boys were 12 years old at phase 1 | Pubertal stage: Tanner staging based on clinical evaluation; Depression: [stage 1] CDI, DSST, DSSP, [stage 2] CDRS (DSM-III) | - | Yes | Pubertal development did not significantly predict depressive symptoms or episodes |

| Compian, Gowen, & Hayward, 2009 [36] | 261 16th grade girls aged 11–13 | Pubertal stage: self-reported Tanner staging; Depression: CDI | Moderator: Peer victimization | No | There was not a main effect of pubertal status on weight concerns or depression symptoms, but more physically mature girls reported the greatest weight concerns and depressive symptoms when experiencing high rates of relational victimization compared to their less physically mature peers who reported the same rates of relational victimization |

| Conley & Rudolph 2009 [43] | 158 youth aged 9.6–14.8 | Pubertal stage: Composite for parent & child reports of Tanner staging & PDS; Depression: KSADS | Moderator: peer stress | Yes | Depression was associated with more mature pubertal status girls and with less mature pubertal status in boys concurrently; in separate models, age was not a significant predictor of depression |

| Ge, Brody, Conger, and Simons, 2006 [41] | 867 African American youth aged 10–12 (only 2% were 12) | Pubertal stage: child & parent reported PDS; Depression: DISC | - | Yes | A more advanced pubertal status was significantly associated with children's self-reported depression in both boys and girls; Pubertal status was not associated with caregivers' reports of depression in boys or girls |

| Ge, Conger, and Elder, 2001 [37] | Iowa Youth and Families Project; 6-year longitudinal study starting when youth were in 7th grade; 451 middle to lower class white families | Pubertal stage: PDS; Depression: SCL-90 | Moderator: stressful life events | Yes | There was not a significant relation between pubertal status and depressive symptoms in 7th grade |

| Ge, Elder, Regnerus, and Cox 2001 [38] | National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health); N = 3633 (1,863 girls & 1,770 boys); youth in grades 7 or 8 at wave 1 | Pubertal stage: self-report; Depression: CES-D (composite of two assessments, 1 year apart) | Mediator: BMI, perceptions of being overweight | No | A more advanced pubertal status & BMI were associated with perceptions of being overweight; the perception of being overweight was associated with more depressive symptoms; these effects are stronger for girls who identify as White or Hispanic than boys or youth who identify as African American |

| Huerta & Brizuela-Gamino 2002 [42] | 971 girls aged 8–16 years old | Pubertal Stage: Self-reported Tanner staging; Depression: Hamilton-Bech-Rafaelson Test | - | No | Symptoms of depression were highest in girls at Tanner stage V; girls' self-esteem decreased as Tanner stage increased |

| Llewellyn, Rudloph, and Roisman 2012 [44] | 85 youth in grades 4–8 grade (boys: N = 35; girl:s N = 51; 96.5% aged 10–14 | Pubertal Stage: composite of youth & parent reports on the PDS & Tanner staging; Depression: SADS | Mediator: other-sex stress | Yes | A more advanced pubertal status was correlated with higher depression scores girls and lower depression scores in boys; more advanced pubertal status was significantly associated with less other-sex stress in boys but was not significantly associated with other-sex stress in girls; other-sex stress did not mediate the relation between pubertal status & depression |

| MacPhee & Andrews 2006 [39] | 2,014 boys and girls aged 12–13 | Pubertal stage: PDS; Depression: CES-D | - | Yes | Examined quality of peer relationships, parental nurturance, parental rejection, self-esteem, body image, pubertal status, SES, conduct problems and hyperactivity/inattention as predictors of depression; self-esteem emerged as the strongest predictor, and parental behavior also emerged as an important predictor; pubertal status was not a significant predictor in full sample or for females separately & was not included in final models |

| Marceau, Neiderhiser, Lichtenstein, and Reiss 2012 [46] | 2 different samples; (1) The Swedish Twin Study of Child and Adolescent Development (706 same-sex twin pairs aged 13–14 assessed twice); (2) the Nonshared Environment in Adolescent Development sample -US (687 same-sex twin/sibling pairs aged 10–18 assessed four times) | Pubertal Stage: PDS; Depression: [NEAD] WAVE1: composite of twin/sibling report on the CDI, BPI, and BEI, parent report on the BPI and CDI, and observer reports, WAVE2: CES-D; [TSCHAD] composite of parent, twin, and self-reports on CBCL & YSR | - | Yes | Among girls, there was a consistent, modest relation between more advanced pubertal stage and more internalizing problems, and this association was explained entirely by shared environmental influences; Among boys, the association between pubertal maturation and internalizing problems was weak and inconsistent |

| Marcotte, Fortin, Potvin, and Papillon 2002 [38] | 547 French-speaking youth aged 11–18 years | Pubertal Stage: PDS; Depression: BDI | Mediator: stressful, body image, self-esteem | No | There was a main effect of PDS on depressive symptoms among a subsample of youth who had recently transitioned to high school |

| Mrug, King, Windle, 2016 [40] | Birmingham Youth Biolence Study (N = 594, mean age 13.2); 79% AA, 21% white | Pubertal Stage: Self-reported Tanner Staging (breast & pubic hair); Depression: DISC | Moderator: race | No | African American (AA) youth reported more depressive symptoms than white youth, and AA youth were more pubertally advanced than white kids; however, depressive symptoms were not related to pubertal development |

| Negriff, Fung, and Trickett, 2008 [35] | 454 youth (241 males and 213 females) followed over 4 time points; aged 9–12; aged 9–13 years at baseline | Pubertal Stage: self-reported Tanner staging; Depression: CDI | Moderator: Maltreatment | Yes | More advanced pubertal stage was not associated with depressive symptoms; gender and maltreatment were not significant moderators |

| Siegel, Aneshensel, Taub, Cantwell, and Driscoll, 1998 [45] | 877 adolescents + parents; aged 12–17, half male half female; 48.6% latino, 25.9% white, 11.4% AA, 10.6% Asian, 3.5% other; balanced on SES | Pubertal Stage: PDS; Depression: CDI | Moderator: race | Yes | A more advanced stage of pubertal development was associated with more symptoms of depression; There was a significant gender x pubertal status interaction, such that CDI scores increased with pubertal status for girls but not for boys; there were no significant differences by race/ethnicity, but the gender difference was largest among white youth |

| Studies controlling for age | |||||

| Angold & Rutter 1992 [48] | 3,519 8–16 year olds; assessed in outpatient or inpatient psychiatry services in 2 London Hospitals | Pubertal Stage: based on physical exam or superficial observation of child (3 stages; pre-pubescent, pubesent, or sexually mature) Depression: ICD-9 diagnosis & a 50 item checklist assessing a range of symptoms | - | Yes | Depression increased with age in boys and girls, but the increase was steeper for girls; There was no gender difference in depression before age 11, but girls were 2 × as likely to be depressed by age 16; When age was controlled for, pubertal status did not predict depression scores |

| Angold et al. 1998 [32] | 1073 boys & girls aged 9, 11, or 13 at baseline (Great Smoky Mountains Study); used data from 4 annual waves | Pubertal stage: Self-reported Tanner staging; Depression: CAPA | - | Yes | Pubertal status was a better predictor of the sex ratio in depression than age; the sex ratio was only apparent after Tanner stage III; Prior to stage III, boys had higher rates of depression, but by Tanner stage III, girls were significantly more likely to be depressed |

| Booth, Johnson, Granger, Crouter, McHale 2003 [65] | 608 youth aged 6–18; sibling dyads recruited | Pubertal stage: PDS, testosterone; Depression: CES-D | Moderator: Parent-child relationship quality | Yes | Main effect of testosterone was related to risk behavior but not depression in boys; Main effect of testosterone was not related to either in girls; Mother and father relationship quality moderated this relationship: In boys aged 10–18, as parent-child relationship quality increased, testosterone-related risk behavior and depression was less evident, but when parent-child relationship quality decreased, testosterone-linked risk taking and depression was more evident. In girls aged 10–14, there was no relation between testosterone and risky behavior among those with high quality mother-child relationships, but among those with poor mother-daughter relationship quality, risk behavior was positively related to testosterone |

| Brooks-Gunn & Warren 1989 [54] | 100 white girls aged 10–14 | Pubertal stage: Self-reported Tanner staging, hormones (FSH, LH, estradiol, testosterone, DHEAS); Depression: CBCL | Moderator: stressful life events | No | There was a non-linear effect of estradiol only (controlling for age and other hormones), such that depression increased in categories 1–3 (as estradiol increases) and decreased in 4 (as it decreases); when pubertal status was entered it was not significant but nonlinear effect of estradiol was; variance explained by hormones alone was small (4%), life events accounted for more (8%); The occurrence of negative events was more likely to be associated with depressive affect in premenarcheal than post-menarcheal girls |

| Copeland, Worthman, Shanahan, Costello, and Angold 2019 [57] | 630 girls aged 9, 11, or 13 at baseline (Great Smoky Mountains Study); used data from 8 annual waves | Pubertal Stage: Self-reported Tanner staging; Depression: CAPA | Mediator: hormones | No | In univariate models, both age and Tanner stage predicted probability of depression diagnosis; in multivariate models with age, pubertal status, pubertal timing, estradiol and testosterone, the only significant predictors were early pubertal timing and higher testosterone levels; when depression status from previous wave was entered, results were the same, suggesting these two predictors can predict change in depression status |

| Forbes, Williamson, Ryan, and Dahl, 2004 [49] | Children & adolescents with (N = 35, mean age = 12.5) or without (N = 36, mean age = 10.5) MDD | Pubertal Stage: Tanner staging via physical exam (pre-early pubertal, mid-late pubertal); Depression: self-report of 8 affective states via visual analogue scale | - | Yes | There was a main effect of group such that depressed participants experienced less positive affect & more negative affect than controls; there was also an interaction with pubertal status & sex, such that depressed girls who were more pubertally advanced experienced higher rates of negative affect |

| Graber, Brooks-Gunn, and Warren, 2006 [55] | 100 white girls aged 10–14 | Pubertal stage: estradiol, DHEAS; Depression: CBCL | Mediator: stressful life events, attention problems, emotional arousal | No | Higher estradiol concentrations were associated with increases in depressive affect; DHEAS levels were not associated with depressive affect; stressful life events, attention problems, and emotional arousal did not mediate the estradiol-depression relation |

| Hayward, Gotlib, Schraedley, and Litt 1999 [59] | 3216 adolescents in 5th-8th grades; categorized into 3 age groups (10–11, 12, and 13–14) | Pubertal Stage: self-reported menarcheal status; Depression: CDI | Moderator: Race | Yes | Among white kids, post-menarcheal adolescent girls had higher depression scores than same-aged pre-menarcheal girls; boys and pre-menarcheal girls had similar depression scores in most age groups; among African American & Hispanic youth, they were no menarche-associated differences in depressive symptoms |

| Joinson, Heron, Araya, Paus, Cousace, Rubin, Marcus, and Lewis 2012 [50] | 2506 girls from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC); using assessments from ages 8, 10.5, 13, and 14 | Pubertal stage: Self-reported Tanner staging (breast & pubic hair); Depression: SMFQ | Moderator: Age | No | The strength of the relation between Tanner breast stage and depressive symptoms increased with age; there was no evidence of a relation between pubic hair stage and depressive symptoms at 10.5 or 13, but at age 14 there was a nonlinear effect such that those still in stage 1 had higher symptoms than those in stage 3, those in stage 5 also had higher symptoms |

| Koenig & Gladstone 1998 [51] | 392 high school (N = 279) and college (N = 113) students; 14–19 years old | Pubertal Stage: PDS (developing, nondeveloping); Depression: BDI | Moderator: Grade, Age | Yes | Among developing females, 15- and 19-year olds had higher BDI scores than 16-, 17-, or 18-year olds; there were no differences in BDI scores by age among nondeveloping participants; developing and nondeveloping participants did not differ in BDI Scores at 16, 17, or 18; this effect was not significant for males; grade was not a significant predictor of depressive symptoms |

| Lewis, Ioannidis, van Harmelen, Neufeld, Stochl, Lewis, Jones and Goodyer 2018 [56] | ROOTS study (UK); N = 1169 (658 girls and 511 boys); assessed at ages 14.5, 16 and 17.5 (study uses data from T1 and T3) | Pubertal Stage: Self-reported Tanner staging (breast & pubic hair); Depression: BDI; Depression: MFQ, KSADS | - | Yes | There was no relation between DHEA and depressive symptoms in boys or girls; cross-sectional associations: in univariate models, breast status predicted depressive symptoms & pubic hair status marginally predicted depressive symptoms in girls; when entered into the same model & with covariates (age, pubertal timing, other confounding variables), only breast status was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms, such that a 1-stage increase in pubertal stage was associated with 1.54 point increase in depressive symptoms; pubic hair status was not related to depression in boys |

| Negriff, Hillman, and Dorn, 2011 [69] | 262 adolescent girls aged 11–17 | Pubertal Stage: menarcheal status; Depression: self-report and parent-report of internalizing symptoms (CBCL & YSR) | Mediator: perceived competence | No | Menarcheal status was associated with increases in self- and parent-reported internalizing symptoms; perceived competence mediated the relation between menarcheal status and internalizing symptoms |

| Obradovíc and Hipwell, 2010 [52] | Pittsburg girls study—oldest cohort of girls; 622 girls, uses 6 annual assessments starting at age 9 | Pubertal Stage: PDS; Depression: latent variable for internalizing symptoms, CSI-4 & ASI-4 to assess depression | Moderator: Age | No | Cross-sectional relations between pubertal status and internalizing symptoms were significant at age 10, 11, & 13 (but not at 12 & 14); association was stronger at 13 than at 10 or 11 |

| Patton et al. 2008 [53] | samples from Washington & Victoria, Australia; 5469 initially ages 10–15 years old; 3 waves of data collection (bi-annually) | Pubertal Stage: PDS; Depression: SMFQ | Mediator: emotional control | Yes | Among female subjects, there was a consistent trend for depressive symptoms to become more common across pubertal stage, with the clearest increases in late puberty. For the male subjects, there was no similar consistent trend across waves of data collection; In prospective analyses, participants were classified as having made one of five transitions at each follow-up: remained early puberty, early to mid-puberty, remained mid-puberty, mid- to late puberty, and remained late puberty; the clearest increase in depressive symptoms among females was those who moved from mid to late puberty |

| Patton, Hibbert, Carlin, Shao, Rosier, Caust, Bowes, 1996 [60] | 2525 students recruited from 45 schools; youth in grades 7 (age 12–13), 9 (age 14–15), and 11 (age 16–17) | Pubertal Stage: time since onset of menarche; Depression: Clinical Interview Schedule | - | Yes | For girls, the strongest predictor of depression was menarcheal status (age and school year level were significant predictors in univariate analyses, but not when menarcheal status was included in the model); girls in highest category or menarcheal status had the highest risk for depression; for boys, the clearest associations with depression were increasing school year level and high parental education |

| Susman, Dorn, Chrousos 1991 [58] | 10–14-year-old boys (N = 56) and 9–14-year-old girls (N = 52) | Pubertal Stage: self-reported Tanner staging, hormones (LH, FSH, testosterone, estradiol, TeBG, DHEA, DHEAS, androstenedione, coritsol, and CBG); Depression: CBCL & DISC | Mediator: hormones | Yes | Among boys and girls, there were no significant relations between depression symptoms and age or stage |

| Yuan 2007 [61] | Naitonal Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health; N = 8,781 boys and N = 9,011 girls in grades 7–12 (mean age = 15.5) | Pubertal Stage: menarcheal status (girls), voice change (boys); Depression: CES-D | Mediator: body perceptions | Yes | During the transition to puberty boys had higher depressive symptoms than post-pubertal boys, due to perceptions that they were not as physically large and developed as their peers; pre-pubertal and post-pubertal boys did not significantly differ on depressive symptoms; post- pubertal girls had higher depressive symptoms than pre-pubertal girls, due to perceptions that they were overweight and more physically developed than their peers; post-menarcheal girls reported more depressive symptoms than pre-menarcheal girls; Importantly, BMI did not explain these relations |

| Studies with pubertal stage as a moderator | |||||

| Patterson, Grotzinger, Mann, Tackett, Tucker-Drob, and Harden 2018 [66] | 1913 individual twins ages 8–20; analyses did control for age | Pubertal Stage: PDS; Depression: CBCL (self- and parent-report) | Moderator: Pubertal Stage | Yes | Genetic influences did not increase as a function of age or puberty; Shared environmental effects decreased with age |

| Glaser, Gunmell, Timpson, Joinson, Zammit, Smith, and Lewis, 2011 [67] | Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and their Children (ALSPAC); 5250 children and adolescents (2589 boys, 2661 girls) assessed at age 11, 13, 14, and 17; analyses did not control for age | Pubertal stage: PDS; Depression: SMFQ | Moderator: Pubertal Stage | Yes | The effect of IQ was such that higher IQ was associated with lower depressive symptoms in less advanced pubertal stages, but higher IQ was associated with higher depressive symptoms in more advanced pubertal stages |

| Richardson, Garrison, Drangsholt, Mancl, and LeResche 2006 [62] | 3101 youth (1548 females, 1553 males) aged 11–17 randomly selected from Group Health Cooperative (HMO in Washington State); analyses did not control for age | Pubertal Stage: PDS; Depression: SCL-90 | Moderator: Pubertal Stage | Yes | Depressive symptoms increased with pubertal stage for boys and girls, but the increase was larger for girls (bivariate correlations); Pubertal stage did not moderate the relation between depressive symptoms and obesity among girls, but among boys, the relation between depression and obesity was stronger in early- and mid-puberty |

| Sun, An, Wang, Zu, and Tao 2014 [63] | 30,392 youth of Han ethnicity (15,388 girls, 15,011, boys) in grades 1–12 across (aged 8–18.9) recruited from 8 different cities in China; analyses did control for age | Pubertal stage: Tanner staging via physical exam; Depression: CDI | Moderator: Pubertal Stage | Yes | Pubertal stage was significantly related to depressive symptoms in boys and girls; Among girls, participating in vigorous physical activity 1–2 days per week was protective against depressive symptoms across all pubertal stages; Among boys, participating in moderate physical activity 1–2 days per week was protective against depressive symptoms at or after Tanner stage III only |

BDI Beck Depression Inventory, CDI Children's Depression Inventory, PDS Pubertal Development Scale, SCL-90 Symptoms Checklist-90, MFQ Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, SMFQ Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, CBCL Child Behavior Checklist, YSR Youth Self Report, CES-D Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, DISC Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, LH luteinizing hormone, FSH follicle stimulating hormone, TeBG Testosterone-estradiol binding globulin, DHEA dehydroepiandrosterone, DHEAS dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, CBG corticosteroid binding globulin, CSI-4 Child Symptom Inventory-4, ASI-4 Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4, KSADS Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, CAPA The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment, DSST Depressive Symptomatology Scale for Teachers, DSSP Depressive Symptomatology Scale for Parents, CDRS-R Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised, BPI Behavior Problems Index, BEI Behavior Events Inventory

Results are organized as follows: first, we review studies that tested the association between pubertal stage/status and depression and differences by sex. These studies are organized by those that did not control for age, followed by those that did control for age. Age and pubertal development are highly correlated, and it is important to tease apart the independent effects of age and pubertal status on depression. Indeed, there were significant differences between studies that did include age as a covariate and those that did not. Within each of these two sections, the studies are divided according to the method used to measure pubertal development (e.g. self-report, hormonal assays, or menarcheal status). Finally, we review moderators and mediators of the pubertal status—depression association. For studies that reported associations between puberty and depression as well as analyses with moderators or mediators, results are discussed in the appropriate sections.

Associations between Pubertal Stage and Depression, Not Controlling for Age

Self-Report

Several studies that did not control for age in analyses failed to find support for a significant relation between pubertal status and depression. For example, Canals and colleagues (1995; N = 507) and Negriff and colleagues (2008; N = 454) both assessed pubertal stage in community samples using the breast growth and genital growth items from Tanner staging for girls and boys, respectively [34, 35]. Both studies failed to find a significant relation between pubertal stage and depressive symptoms or diagnosis in either sex. Similarly, Compian et al. (2009) did not find a significant main effect of pubertal stage on depressive symptoms in a community sample of 261 girls aged 11–13 [36]. This study assessed pubertal stage using a composite score of both pubic hair and breast growth items from Tanner stage drawings.

Ge et al. (2001a) modeled depressive symptoms over six years from early- to mid-adolescence in a community sample (N = 451) and tested pubertal status (trichotomized into low, medium, and high based on PDS score) in 7th grade as a predictor of depressive symptoms over time [37]. Although this design does not meet inclusion criteria for this review, they also reported cross-sectional associations between pubertal status and depressive symptoms at baseline (when youth were 12 years old on average). They found that girls and boys in the high pubertal status group in 7th grade did not significantly differ from youth who were in the medium or low pubertal status groups in levels of depressive symptoms.

Marcotte and colleagues (2002) found that, in a community sample of youth (N = 547), pubertal stage was not associated with depressive symptoms among the larger study sample [38]. However, pubertal stage was associated with higher depressive symptoms among a subsample of youth who had recently transitioned to high school (N = 276). It is also important to note that this model was tested in a sample of boys and girls together and did not report differences by sex.

In an effort to explore the relative contributions of a number of different well-established risk factors for depression, MacPhee and Andrews (2006) examined the role of peer relationship quality, parental nurturance, parental rejection, self-esteem, body image, SES, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and pubertal status (assessed by a composite score from PDS questions) as predictors of self-reported symptoms of depression in a large sample (N = 2014) of 12 and 13 year-olds [39]. In multivariate analyses, pubertal status was the only variable that did not emerge as a significant predictor and was dropped from subsequent analyses. Similarly, Murg, King, and Windle (2016) investigated mediators of the gap in depression between African American and White youth in a community sample (N = 594). They found that African American youth reported significantly more depressive symptoms and were more advanced in terms of pubertal stage, but pubertal stage was not correlated with depressive symptoms in this sample [40].

However, other studies did find a significant relation between pubertal stage and depression, despite not including age as a covariate. For instance, Ge, Brody, Conger, and Simons (2006) tested the association between pubertal status, per the PDS, and depressive symptoms in a community sample of 867 African American 10–12-year-old youth [41]. Zero-order correlations revealed a more advanced pubertal status was associated with self-reported, but not parent-reported, depressive symptoms for boys and girls. It is important to note that it is easier to find significance with bivariate correlations than in a multiple regression model, which could explain why the study found a significant relationship between the PDS and depressive symptoms even without controlling for age.

Although Ge and colleagues (2006) found support for a relation between pubertal stage and depression in both boys and girls, results from other studies suggest that the relation is more consistent for girls than boys. In a large (N = 971) community sample of girls aged 8–16, Huerta and colleagues (2002) found that self-reported depressive symptoms were highest among youth in the most advanced Tanner stage 5 (as assessed by the breast development item; [42]).

When sex was tested as a moderator of the relation between pubertal stage and depression, several studies demonstrated that a more advanced pubertal stage was associated with increased risk for depression among girls only. Conley and Rudolph (2009) and Llewellyn, Rudolph, and Roisman (2012) tested pubertal stage × sex interactions predicting levels of depression concurrently in the same community sample of youth (Ns = 158 and 85, respectively) aged 9–14 using a pubertal stage latent variable comprised of parent and child reports on both the PDS and Tanner staging [43, 44]. They found that a more advanced pubertal status was associated with higher levels of depression in girls, whereas a more advanced pubertal status was associated with lower levels of depression in boys. Although neither study included age as a covariate, Conley and Rudolph (2009) did test interactions between sex and age predicting depression and found that both the main effect of age and the interaction were not significant. Therefore, the authors concluded that the sex difference in depression is better predicted by pubertal processes than by chronological age.

In univariate analyses, Siegel and colleagues (1995) found that a more advanced pubertal status (as assessed by the PDS total score) was associated with more depressive symptoms in a community sample of 877 adolescents [45]. However, this was qualified by a significant pubertal status × sex interaction, such that pubertal status was associated positively with depressive symptoms among girls only. Another study tested this hypothesis in two different longitudinal community samples (The Swedish Twin Study of Child and Adolescent Development, N = 706 and the Nonshared Environment in Adolescent Development, N = 687) of twins aged 13–14 and 10–18 and found a consistent, modest association between pubertal status (per the PDS) and internalizing problems across samples for girls only [46]. The relation was such that a more advanced pubertal status was associated with more internalizing problems; there was a small, but significant, relation between pubertal status and internalizing problems for boys in one sample, but it was such that a more advanced pubertal status was associated with fewer internalizing problems in boys.

Hormone Levels

Angold and colleagues (1999) analyzed Tanner stages (mean of both breast and pubic hair development) and hormone levels from three different waves of assessment as independent predictors of depression levels in 465 girls aged 9–15 in the Great Smoky Mountains Study sample, which is an epidemiological sample [47]. In independent models testing within person effects, Tanner stages, estradiol, and testosterone all significantly predicted depression, and the effects were substantial (ORs = 1.6, 2.5, 4.0, respectively). However, when they were included in the same model, only estradiol and testosterone remained significant predictors. Notably, the effect of estradiol was linear, but the effect of testosterone was non-linear, such that those in the 60th percentile or higher were more likely to be depressed. The authors concluded that these results suggest that it is the biological and hormonal changes, rather than the morphological changes, associated with puberty that confer risk for depression.

Associations Between Pubertal Stage and Depression, Controlling For Age

Self-Report

One of the first studies to test this hypothesis was by Angold and Rutter (1992). In a large sample (N = 3519) of youth aged 8–16 recruited from inpatient and outpatient psychiatry clinics in two London hospitals, they found that pubertal status, as assessed by physical exam (pre-pubescent, pubescent, or sexually mature) was not associated with the presence of ICD-9 depression diagnosis in boys or girls [48].

However, eight other studies found support for a relation between self-reported pubertal status and depression, and this effect was more consistent for girls than for boys. Angold and colleagues (1998) found that Tanner stage was a better predictor of the sex difference in depression than age, and the sex difference only emerged after Tanner stage 3 or mid-puberty [32]. Further, they found that this sex ratio emerged as a result of decreasing rates of depression in boys, which were not related to transitioning to mid-puberty, and increasing rates of depression in girls, which were related significantly to pubertal status. It should be noted that this study, like Angold and colleagues (1999), also utilized the Great Smoky Mountains sample, but it included a larger sample (N = 1073) of both boys and girls and tested a different question than the previous study.

Another study utilized an ecological momentary assessment (EMA) design to investigate the daily experiences of positive and negative affect (operationalized as a latent variable comprised of self-reported affective states, including happy, sad, drowsy, calm, energized, alert, lethargic, and tense) as a function of pubertal status in 71 boys and girls with a mean age of 12.5 [49]. They found that a more advanced pubertal status, assessed by physician ratings of Tanner stages, categorized as pre-early (stages 1–2) and mid-late (stages 3–5), was associated with more negative affect for girls only.

Joinson and colleagues (2012) analyzed the independent effects of Tanner breast and pubic hair development on depressed mood [50]. The authors tested this in a large sample (N = 2506) of girls assessed at ages 10.5, 13, and 14 in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), a population-based study. This study tested pubertal stage at each assessment as a predictor of a single latent variable capturing self-reports of depressive symptoms at all three assessments and found that the strength of the association between Tanner breast stage and depressive symptoms increased with age. Additionally, there was no relation between Tanner pubic hair stage and depressive symptoms at age 10.5 or 13, but at age 14, youth in stage 1 and stage 5 had the highest levels of depressive symptoms.

The remaining studies assessed pubertal stage using the PDS. In an effort to examine the combined effects of pubertal development and school transition, Koenig et al. (1998) tested the relation between pubertal stage and depression by age and recency of school transition in a community sample of 392 high school and college students [51]. They categorized youth aged 14–19 as being either developing (PDS stage 3–4) or non-developing (PDS stage 1, 2, or 5) and hypothesized that developing adolescents in grades 9 or first year of college (recently transitioned to a new school) would have the highest depression scores. However, they found that developing females aged 15 and 19 had the highest depression scores; this effect was not significant for boys. Grade was not related to depressive symptoms. The independent effects of the earliest and latest stages of pubertal development were confounded due to the way that pubertal development was operationalized in this study, but the results suggest that 15- and 19-year-old girls experience the highest levels of depression during mid-puberty.

One study tested this hypothesis in the oldest cohort of girls from the Pittsburgh Girls Study ([52]; N = 622). They tested cross-lagged models of pubertal stage and depressive symptoms using all six annual assessments (when youth were aged 9–14) and found that the cross-sectional association between pubertal stage and depression was significant at age 10, 11, and 13, and the association was strongest at age 13 (Bs = 0.15–0.24).

Patton and colleagues (2008) tested the relation between PDS scores and depressive symptoms in three waves of assessment in a large sample (N = 2525) of youth, aged 10–15 at baseline, from the US and Australia [53]. This study used a self-report measure of depression (the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire) but dichotomized responses into low (scores of less than 11) or high (scores of 11 or higher) depressive symptoms. They found that a more advanced pubertal stage was associated with more depressive symptoms at all three waves among girls, such that girls in stage 4/5 were 3.5–3.6 times more likely to have high depressive symptoms than girls in pubertal stage 1–2. For boys, there was no consistent relation between pubertal stage and depressive symptoms. Further, age did not significantly predict depressive symptoms when entered into the same model as pubertal stage.

Hormone Levels

Brooks-Gunn and Warren (1989) tested the effects of pubertal status (per physician rated Tanner stages), pubertal timing, hormones, and life stress on depression symptoms in a community sample of White girls aged 10–14 ([54]; N = 100). Girls were categorized into four groups of incrementally higher estradiol concentrations intended to correlate with Tanner stages. They found a non-linear effect of estradiol only, such that depression symptoms increased from estradiol stages 1–3 and decreased in estradiol stage 4. When Tanner stages were entered into the same model, pubertal stage was not a significant predictor. In another study utilizing the same sample, Graber and colleagues (2006) operationalized gonadal development as estradiol levels and adrenal development as DHEAS levels in a sample of girls aged 10–14 and found that estradiol, but not DHEAS, was associated with increases in depressive affect ([55]; B = 0.34).

Lewis and colleagues (2018) hypothesized that Tanner breast stage in girls, which is largely controlled by increases in estradiol, would be more strongly associated with depressive symptoms than pubic hair stage, which is primarily controlled by increases in androgens [56]. They tested this hypothesis in a large sample (N = 1169) of boys and girls aged 14.5. Although they did not measure gonadal hormones directly, they did measure DHEA. There was not a significant association between DHEA and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. In univariate models, a 1-unit increase in breast stage was associated with a 2.00 unit increase in depressive symptoms, and a 1-unit increase in pubic hair stage was associated with a 0.99 unit increase in depressive symptoms; pubic hair stage was not related to depressive symptoms in boys. When breast stage, pubic hair stage, age, pubertal timing, and other confounding variables were entered into the same model, only breast stage was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms among girls. The same pattern of results was found when predicting to depression diagnoses.

Together, the previously reviewed studies suggest a link between increasing estradiol levels, and corresponding breast development, and depression among girls and weak or inconsistent support for a link between hormonal changes and depression among boys. However, results from other studies contradict this conclusion. For instance, in an effort to build on their previous work using the Great Smoky Mountains Study sample, Copeland and colleagues (2019) evaluated the within-person effect of pubertal timing, pubertal stage (Tanner stages—mean of breast and pubic hair development), age, estradiol, and testosterone across all eight waves of data for girls only (aged 9–16; [57]). In univariate models, Tanner stage and testosterone were associated with risk for depression diagnosis across the eight waves (ORs = 1.7 and 2.3, respectively). In adjusted models including previous depression status, pubertal timing, pubertal stage, age, testosterone, and estradiol, the only significant predictors of change in depression status were early pubertal timing and testosterone (OR = 2.0).

Susman, Dorn, and Chrousos (1991) also investigated the effects of pubertal stage, age, and gonadal hormones on internalizing behavior problems and depression symptoms in a community sample of boys aged 10–14 (N = 52) and girls aged 9–14 (N = 56). They repeated assessments every six months for one year (3 times total) and tested concurrent relations at each assessment; however, depressive symptoms were assessed only at the third timepoint. Concurrent multivariate analyses at the third assessment revealed that among boys, there were no relations between hormones and depression symptoms, but a more advanced genital stage was associated with more symptoms. Among girls, there were no significant relations between depression and pubertal stage, pubertal hormones, or age [58].

Menarcheal Status

Some studies operationalize pubertal development as whether a girl has begun to menstruate or not, otherwise referred to as menarcheal status. Menarche is just a single event in the long, dynamic pubertal process, and there is a high degree of variability in age at first menarche. However, it generally occurs around Tanner stage 4, once estradiol levels reach high enough concentrations. Perhaps unsurprisingly, results from studies that tested menarcheal status as a predictor of depression generally are consistent with those that tested breast development or estradiol as predictors of depression.

Hayward and colleagues (1999) found that, in a large community sample of 3216 youth in 5th–8th grades, post-menarcheal girls had higher levels of depression symptoms than pre-menarcheal girls of the same age, and boys had similar depression levels as pre-menarcheal girls [59]. In a large community (N = 5469) sample of youth age 12–17 recruited from Victoria, Australia, Patton and colleagues (1996) coded menarcheal status as an ordinal variable, such that the lowest value meant that the participant hadn’t reached menarche yet, and the highest value meant that the participant began menstruating at least 3 years ago [60]. In models predicting depression and anxiety symptoms that included age and school year, the strongest predictor of depression among girls was menarcheal status, such that levels of depression and anxiety symptoms increased as time since onset of menarche increased. Pubertal development was not assessed in boys. Finally, Yuan (2007) assessed menarcheal status in girls and degree of voice change in boys as indicators of pubertal development in a longitudinal community sample of 17,792 youth [61]. Pre-menarcheal girls had significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms than post-menarcheal girls (d = 0.18). Boys who had experienced “a little” voice change had higher levels of depressive symptoms than those who had experienced “a lot” of voice change. The authors interpreted this to mean that boys had the highest levels of depressive symptoms during the transition into puberty, whereas for girls, advancing pubertal development was associated with worse psychological well-being. These results also are consistent with other studies reviewed above that have shown that depressive symptoms actually decrease for boys across puberty.

In sum, many studies found that a more advanced pubertal stage was associated with a higher risk of depression, particularly among girls, but some studies did not find evidence for this relation. Methodological differences may explain these discrepant findings. For instance, nearly all of the studies that did not find a significant relation between pubertal stage and depression did not control for age in their analyses [34–37, 39], and one study did not separate the analyses by sex [40]. Given evidence that depression actually may decrease across puberty for boys [43], analyzing samples of boys and girls together may confound the effects of sex and lead to null findings.

One study did control for age and still concluded that pubertal stage was not related to risk for depression [48]. However, this study had significant methodological limitations, including a lack of standardized assessments of pubertal stage and depression. Pubertal stage was assessed in some cases by a physical exam, but was not based on standardized ratings. Further, some cases were categorized by superficial observations of the child. In addition, depression diagnoses were made based on ICD-9 nosology and included other affective syndromes, such as bipolar disorder and adjustment disorder. Thus, these measures are not comparable to those used in the majority of other studies included in this review and may play a role in the lack of an effect found in this study.

Furthermore, the inclusion of other variables in models may explain why pubertal stage did not emerge as a significant predictor of depression. For instance, MacPhee and Andrew (2006) entered six other well-established predictors of depression (e.g. self-esteem) into their models before pubertal stage and did not report univariate correlations between pubertal stage and depression. It is possible that pubertal stage simply did not significantly explain the small proportion of variance in depression that remained above the effects of the other variables entered into the models. Importantly, the other variables entered, like parental rejection/nurturance, peer relations, and self-esteem, also may vary as a function of pubertal stage, and may mediate the relation between pubertal stage and depression, explaining the lack of an effect. Similarly, Negriff and colleagues (2008) tested structural equation models with pubertal stage predicting both depression and delinquency. Pubertal stage was not related to depression in these models, but there was a significant univariate association between pubertal stage and depression.

Moderators

Sex

As reviewed above, the majority of studies that tested sex differences in the pubertal stage-depression relation found that a more advanced pubertal stage was associated with an increased risk for depression among girls, but not boys. Some studies even found that depression decreased across puberty for boys [44, 61]. However, three studies found that a more advanced pubertal stage was associated with more depressive symptoms in both boys and girls [41, 62, 63]. An important feature of the sample used in Ge et al. (2006) is that analyses did not control for age, and youth were at the very start of pubertal development (ages 10–11; Mean PDS score boys: 1.88; girls: 2.18). The authors note in the discussion of their findings that pubertal stage, timing, and age are intimately confounded, particularly in samples of youth at the very start of development. Very advanced pubertal development in youth at young ages may reflect early pubertal timing, and there is literature to suggest that boys with early pubertal timing are at risk for depressive symptoms [64]. Analyses did not control for age, so it is difficult to disentange whether pubertal stage or pubertal timing is driving this effect, which could explain why this study found a significant, positive relation between pubertal stage and depression among boys. This further highlights the importance of controlling for age when investigating the effects of pubertal stage. Furthermore, this finding is based on bivariate correlations in all three of these studies, which could explain why an effect was found for both girls and boys.

Race

In addition to reporting the main effect of pubertal stage on depressive symptoms, three studies also reported differences by race/ethnicity. The first, Siegel and colleagues (1998), tested whether pubertal development influences depressed mood similarly across race/ethnicity and whether the gender difference in depressed mood differs by race/ethnicity in a sample of 877 youth aged 12–17. They tested this in a sample of youth who identified as either Latino/a, African American, White, Asian or “other.” They found that a more advanced pubertal stage was associated with depressive symptoms among girls only. There were no significant differences by race, but the mean difference between boys and girls was largest among White youth. In a sample of 3216 youth in 5th–8th grade, Hayward and colleagues (1999) found that post-menarcheal girls had higher levels of depression than boys or pre-menarcheal girls overall, but when they stratified analyses by race, this effect held only for White youth; there were no menarche-related differences in levels of depression between youth who identified as African American or Hispanic. Together, these results suggest that the pubertal stage-depression link is strongest among White girls. However, another study (N = 594) attempted to test whether pubertal stage and a number of well-established risk factors explained the difference in depressive symptoms by race. Results demonstrated that African American youth reported higher levels of depressive symptoms and more advanced pubertal development on average than White youth. However, pubertal stage was not related significantly to depressive symptoms in this sample, and therefore, it was not included in final models [40].

Environmental Moderators

Stressful life events, peer victimization, and parent relationship quality all have been evaluated as moderators of the pubertal stage—depression relation. Results from these studies suggest that these environmental stressors all exacerbate the effect of pubertal development on depressive symptoms. Brooks-Gunn and Warren (1989) tested stressful life events as a moderator of the relation between pubertal factors and negative affect in a sample of 100 White girls aged 10–14. First, there was a significant main effect of stressful life events on negative affect, and this effect accounted for a higher proportion of variance than the effect of hormones (8% vs. 4%, respectively). Further, negative life events were more likely to be associated with negative affect in pre-menarcheal girls than post-menarcheal girls. Although perhaps counter to expectation, this finding can be interpreted to mean that negative life events are most impactful during the earlier stages of puberty, when the most rapid changes are occurring.

Compian and colleagues (2009) tested the effect of peer victimization on the pubertal stage—depression relationship. Although they did not find a significant main effect of pubertal stage on depression in their sample of 261 early adolescent girls, they did find that more physically mature girls who experienced higher levels of peer victimization reported significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms. These youth also reported significantly higher levels of weight concerns.

Finally, Booth and colleagues (2003) investigated parent–child relationships as a moderator of the relation between testosterone and adolescent adjustment in a large (N = 608) community sample of girls and boys aged 6–18 [65]. In models controlling for child age and parents’ testosterone levels, they found that youth testosterone levels were not related significantly to depression symptoms in boys or girls, but there was a significant interaction with parent relationship quality. Among boys with high parent relationship quality, there was not a significant relation between testosterone and depression. However, among boys with low parent relationship quality, lower testosterone was associated with higher depression. There was a similar pattern of results for girls, but it was significant only for father-child relationship quality (not mother).

Pubertal Stage as a Moderator

A number of studies have tested pubertal stage as a moderator of the relation between depression and another variable. For instance, Richardson and colleagues (2006) examined whether pubertal stage (per the PDS) moderated the relation between body mass index (BMI) and depressive symptoms in a large (N = 3101) sample of youth aged 11–17 [62]. They found that there was no difference in the relation between BMI and depression depending on pubertal stage. The study also reported that symptoms of depression were positively correlated with pubertal stage for both boys and girls, but the increase was larger for girls.

Sun and colleagues (2014) tested physical activity as protective against depressive symptoms across puberty in a large, representative sample of Chinese children and adolescents ([63]; N = 30,399). The authors found that vigorous physical activity 1–2 days a week was protective against depressive symptoms in all stages of puberty for girls, but for boys, moderate physical activity 1–2 days per week was protective against depressive symptoms prior to mid puberty (Tanner genital stage 3). Notably, pubertal stage was positively correlated with depressive symptoms in this sample, offering cross-cultural support for a link between more advanced pubertal development and depressive symptoms.

Another study tested whether the environmental (shared and nonshared) and genetic influences on depression and anxiety symptoms differ by chronological age and pubertal stage in a large (N = 1913) diverse sample of twins [66]. The authors concluded that genetic and environmental influences on depression or shared risk for depression and anxiety remained fairly stable across puberty. In an exploratory model predicting risk for depression that allowed simultaneous moderation as a function of both age and puberty, there was evidence that genetic influences increased across puberty. Overall, the authors concluded that the threshold for vulnerability to developing internalizing symptoms may change across development, but the relative importance of genetic and environmental influences remains fairly constant.

Finally, Glaser and colleagues (2011) examined whether the effect of IQ on depressive symptoms varied as a function of pubertal stage or age in a sample of 5250 youth in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and their Children [67]. The pattern of results was similar for both pubertal stage and age: at age 11 and in less advanced pubertal stages, higher IQ was associated with lower depressive symptoms. However, at age 13–14 and in more advanced pubertal stages, higher IQ was associated with more depressive symptoms. It is important to note that models testing age and pubertal stage as predictors were run separately and did not control for each other, so it is difficult to conclude which was driving this effect.

Mediators

Environmental Mediators

In an effort to understand how the social changes associated with puberty may explain the increase in depressive symptoms, studies have examined environment/life stress as a mediator of the pubertal stage—depression relation. Llewellyn and colleagues (2012) tested stress within other-sex relationships as a mediator in a community sample of 85 adolescents and found that other-sex stress decreased with more advanced pubertal stage in boys, but was not related to pubertal stage in girls. Further, other-sex stress partially mediated the relation between pubertal timing and depression in girls, but did not mediate the relation between pubertal stage and depression. Similarly, Graber et al. (2006) found that negative life stress did not mediate the relation between estradiol and depression (nor did attention difficulties or emotional arousal) in a sample of 100 White girls aged 10–14. One study found that stressful life events did mediate the relation between pubertal stage and depression among youth from a subsample of 276 youth who had recently transitioned to high school [38]. However, this study tested this effect in a sample of boys and girls and did not examine whether sex moderated this relationship. Marceau and colleagues (2012) found that shared environmental influences, rather than nonshared environmental or genetic influences, entirely explained the relation between pubertal stage and depression among girls in two separate samples of twins (Ns = 706 and 687). Overall, these results suggest that changes in the shared environment (e.g. home, family, nutrition, societal messages about body size) rather than nonshared environment (friendships, romantic relationships) may play a more important role in the increase in depressive symptoms across puberty.

Body Image/BMI

Researchers also have examined whether the physical changes associated with puberty explain the accompanying increase in depressive symptoms. Yuan (2007) tested whether BMI or perceptions about one’s body changes explained the relation between pubertal stage and depression (N = 17,792). Results revealed that during the transition to puberty, boys had higher levels of depressive symptoms than post-pubertal boys, and this was due to the perception that they were not as physically large or developed as other boys. Conversely, post-pubertal girls had more depressive symptoms than pre-pubertal girls, and this was due to the perception that they were overweight and more physically developed than other girls. Importantly, BMI did not significantly mediate these relations. Ge and colleagues (2001b) examined this same question as well as whether there were differences by race/ethnicity using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health ([68]; N = 3,633). They found that among White and Hispanic girls, more advanced pubertal development and its associated increases in BMI were significantly associated with perceptions of being overweight, which, in turn, were associated with higher depressive symptoms, lower self-esteem, and higher somatic complaints. Similarly, Marcotte et al. (2002) found that self-esteem and body image mediated the relation between pubertal stage and depression among a subsample of youth (N = 276) who had recently transitioned to high school. In sum, the physical changes associated with puberty, particularly weight gain, appear to play a role in the increase in depressive symptoms, but this is largely driven by adolescents’ perceptions about their changing bodies.

Hormones

It can be argued that studies that include both pubertal stage and hormones in models predicting depressive symptoms are testing whether hormone levels actually explain the pubertal stage—depression relation. Several of the studies reviewed above do report findings with both pubertal stage and hormones in the same model. In the Great Smoky Mountains sample, one paper (N = 465) found that both testosterone and estradiol predicted depression diagnosis above and beyond the effect of pubertal stage [47], but when they replicated these analyses with a larger sample (N = 630) and more follow-ups, they found that only testosterone was a significant predictor [57]. Conversely, two other studies found that estradiol significantly predicted depressive symptoms beyond the effect of pubertal stage in a sample of 100 10–14 year old girls, although they did not test the effect of testosterone in their models [54, 55]. Finally, Susman and colleagues (1991) did not find a significant relation between hormones and depression in boys or girls aged 10–14 and 9–14, respectively (N = 108). Furthermore, DHEA/DHEAS did not appear to be related to depression beyond the effect of pubertal stage [56, 58].

There are a number of methodological differences to note among these studies, namely sample composition, how depression was operationalized, and the analyses used to test hypotheses. Most of the studies that have tested hormones as a mediator of the pubertal stage-depression relation and concluded that estradiol is driving this effect or failed to find an effect of hormones utilized community samples, operationalized depression as depressive symptoms, and employed cross-sectional analyses. Copeland and colleagues (2019) tested this hypothesis in a large, epidemiological sample (N = 630) assessed over seven years and used within-person analyses to evaluate the effects of pubertal stage and hormones on depression diagnoses. The characteristics of this study may offer a more robust test of the nature of the relationship between pubertal hormones and depression and provide more generalizable conclusions. However, more work is needed to replicate these findings.

Other Mediators

One other study tested perceived competence in social, academic, and physical domains as a mediator of the relation between pubertal stage and internalizing problems [69] and found support for a mediational model, such that menarcheal girls had lower competence, which, in turn, predicted higher internalizing symptoms.

Discussion

The current study involved a systematic review of the literature on the association between pubertal stage and depression and found that a more advanced pubertal stage is associated with an increased risk for depression above and beyond the effect of age. Further, this relation appears stronger and more consistent for girls, and there is some evidence to suggest that it also is stronger in White youth. Some studies failed to find a significant relation between pubertal stage and depression, but methodological differences, such as not controlling for age or the inclusion of potential mediators of the pubertal stage-depression relation in statistical models, can explain many of these discrepant results (e.g. 36, 39, 35). A quantification of types of results found across studies can be found in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

A visual depiction of the quantification of results from articles reviewed

The finding that depression increases across puberty for girls is consistent with vast epidemiological evidence that shows nearly equal rates of depression in boys and girls during childhood, but a preponderance of depression in girls starting in adolescence. Around age 13, when most youth have already entered puberty, a gender gap emerges, with girls becoming twice as likely to be depressed [4]. Therefore, this age-related increase in depression mirrors the increase across pubertal stage and likely is better explained by pubertal development than by aging. Furthermore, some studies found that rates of depression actually decrease for boys across puberty [44, 61]. Thus, the pubertal transition may play an integral role in the gender gap that emerges at this time. Indeed, there is support for this exact hypothesis [32].