Abstract

Background & Aims

Increasing enthusiasm around integrating locoregional therapy with systemic immunotherapy in primary liver cancer underscores the need for non-invasive imaging biomarkers. In this study, we aimed to establish advanced molecular MRI tools for monitoring T-cell responses to cryoablation in murine models, distinguishing between immunologically "hot" and "cold" hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods

Immunocompetent 7-10-week-old C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice (n = 18 each) received carbon tetrachloride for 12 weeks to induce cirrhosis. Intrinsically immunogenic Hepa1-6 (“hot”) and non-immunogenic TiB75 (“cold”) cells were orthotopically implanted into C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice, respectively, to generate focal HCC lesions. After one week, animals were randomly assigned to (A) partial cryoablation (pCryo) (1.2 mm cryoprobe, -40 °C) or (B) no treatment (n = 8 per group and tumor type). Gadolinium 160 (160Gd)-labeled CD8+ antibody was administered intravenously either 1 week after tumor induction (control) or 1-week post (pCryo) (treatment). T1-weighted MRI scans were performed using a 9.4 T MRI scanner. Radiological-pathological correlation included imaging mass cytometry and immunohistochemistry.

Results

pCryo-treated Hepa1-6 tumors displayed peritumoral ring enhancement on T1-weighted MRI with 160Gd-CD8, correlating with imaging mass cytometry signal patterns. Untreated Hepa1-6 tumors lacked such enhancement. Radiological-pathological correlation confirmed significantly increased tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes in pCryo Hepa1-6 tumors compared with untreated tumors (p <0.001), and a stronger local response compared with systemic lymph nodes (p = 0.0415). Increased T-lymphocyte infiltration was not observed in TiB75 tumors, as indicated by MRI and histopathology.

Conclusion

pCryo induced increased T-cell infiltration in Hepa1-6 tumors compared to TiB75 tumors. T1-weighted MRI, following 160Gd-CD8 antibody administration, reproducibly detected the ablation-induced changes. These findings encourage further investigation of MRI-based molecular imaging biomarkers to assess immune responses to local tumor therapies.

Impact and implications

This study successfully established reliable MR-based molecular imaging tools to visualize CD8+ anti-tumor specific T-cell infiltration following partial cryoablation (pCryo) in murine tumor models. The study's significance lies in advancing our understanding of immune responses within induced cirrhosis and distinguishing between "hot" and "cold" tumor phenotypes. The findings not only build upon previous proof-of-principle data but also extend this technology to include different immune cell types in hepatocellular carcinoma. The study reveals that pCryo may exert specific effects on the tumor microenvironment, augmenting the anti-tumor immune response in immunogenic tumors while displaying a weaker local effect in non-immunogenic tumors.

Keywords: Cryoablation, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Immune Response, In vivo Imaging, Immuno-metabolic interplay

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Partial cryoablation increases CD8+ T-cell infiltration of an immunogenic tumor microenvironment compared to control (p <0.0001).

-

•

Partial cryoablation significantly increased CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration in Hepa1-6 tumors (p = 0.0415).

-

•

CD4⁺ and CD11b⁺ cell responses were also dependent on tumor type, with immunogenic Hepa1-6 tumors showing a more pronounced effect.

-

•

MRI with 160Gd-labeled CD8+ antibodies enabled selective imaging of T cells in immunogenic HCC tumors.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), frequently associated with cirrhosis, ranks third in global cancer-related mortality, often attributed to factors such as viral hepatitis, alcohol-related and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.[1], [2], [3] Cirrhosis-induced chronic inflammation impairs liver immune function, affecting both the local immune microenvironment and the global immune system.4 Minimally invasive locoregional therapies play a significant role in managing early-to intermediate-stage disease. Ongoing clinical trials are investigating the combinations of locoregional therapies with systemic immunotherapy, hoping to improve long-term outcomes and response rates of both modalities.5 Targeted immunotherapies (IMT) have emerged as a powerful strategy for cancer treatment as they can modulate the patient’s own immune system to boost an effective anti-tumor immune response. While successful in melanoma and lung cancers, objective response rates in IMT clinical trials for liver cancer do not exceed 15-30%.6,7 Thus, a pressing question in HCC management revolves around overcoming immunotherapy resistance to extend its benefits to a larger patient population. Currently, patient selection for immunotherapy relies solely on ex vivo tissue-based biomarkers, which fail to consider tumor heterogeneity across lesions or predict treatment outcomes.8 This results in HCC immunotherapy being applied clinically without understanding whether the tumor phenotype is suitable for immunotherapy. While the promise of immunotherapy may materialize, it requires a paradigm shift away from “one size-fits-all” indications to succeed in liver cancer. Consequently, patient management requires the application of refined imaging biomarkers for better clinical decision support and patient selection before and during therapy.

Cryoablation is an emerging and promising therapeutic approach for modulating the tumor microenvironment (TME) in various types of solid tumors.9,10 While its use in the liver has been limited, exploring its potential role in combination therapies could spark a resurgence of this technology in liver-related applications. The tissue necrosis induced by tissue freezing causes the release of tumor-associated antigens that can activate a cytotoxic T cell-mediated specific immune response. In contrast to hyperthermal ablation therapies, cryoablation involves the rapid reperfusion of cryo-injured tumors upon thawing of the frozen tissue ice ball.11 This unique characteristic facilitates increased infiltration of immune cells into the tumor site following therapy, thereby garnering increasing attention towards investigating the immune response after cryoablation.12 Although cryoablation is associated with the release of tumor antigens, the induced anti-tumor immune response is insufficient to eradicate advanced tumors with systemic spread alone.13,14 Preclinical studies combining cryoablation with immunotherapy have shown promising results, demonstrating improved survival compared to individual therapies in murine models of prostate cancer and melanoma.15,16 Additionally, pilot studies in patients with melanoma and breast cancer treated with cryoablation and checkpoint inhibitors have reported good tolerability and favorable immunologic effects.17,18

Nevertheless, the intricate TME poses a challenge to the long-term success of these therapies in HCC.19 Consequently, there is a significant clinically unmet need for non-invasive imaging techniques that can characterize the TME as either immuno-suppressive or immuno-permissive before initiating therapy, especially in advanced tumors that cannot be completely ablated. To address this need, our study investigated previously established 160Gd-based probes for in vivo imaging of CD8+ T lymphocytes in residual tumors after partial cryoablation (pCryo).20 This approach utilizes both non-immunogenic and immunogenic orthotopic syngeneic mouse models of HCC in the context of toxin-induced cirrhosis.

Materials and methods

Animal model and cell lines

This study, approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, followed U.S. Animal Welfare Regulations and adhered to ARRIVE guidelines. C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice (n = 18 each), aged 7-10 weeks (Charles River Laboratories, Boston, MA) were housed in pathogen-free conditions. Sample size calculation for the experiments considered eight mice randomly assigned per group, a potential 5% dropout rate during cirrhosis induction, and a 90% tumor growth rate (8 mice x 2 groups x 1.05 x 1.10 = 18). Mouse-derived HCC cell lines Hepa1-6 and TiB75 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained according to manufacturer’s instructions (supplementary materials and methods). Cell line selection was based on immunogenic characteristics assessed using The Cancer Genome Atlas. Hepa1-6, classified as a "hot" tumor, exhibited the highest T-cell infiltration and a significant presence of M1-skewed tumor-associated macrophages. In contrast, TiB75 displayed an immune-resistant tumor profile with a low percentage of CD8+ T cells and a high abundance of anti-inflammatory M2-like tumor-associated macrophages.21

Cirrhosis induction and tumor implantation

Cirrhosis induction involved repetitive oral administration of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) (CCl4, 50% (vol/vol) in olive oil, three times per week for 12 weeks)22 before orthotopic implantation (Fig. 1) (supplementary materials and methods). A total of 1.5 × 106 Hepa1-6 (immunogenic) and TiB75 (non-immunogenic) cell lines suspended 1:1 (vol/vol) in Matrigel were directly implanted into the laparoscopically exposed subcapsular region of the liver parenchyma in the left lobe in their respective syngeneic mouse strains, C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ. Briefly, the cell suspension was prepared in PBS pH 7.4 (Quality Biological, no.114-058-101) and resuspended in Matrigel immediately before injection using 1-ml insulin syringes with 26-gauge needles (BD, no.309597), limiting the volume to 20-30 μl to prevent leakage or backflow. Needle retraction was followed by saline drops and gauze to minimize bleeding and potential backflow.

Fig. 1.

Schematic view of establishing orthotopic HCC model in cirrhotic background.

C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice (n = 18 each) were subjected to escalating doses of oral CCl4 three times per week for a total of 12 weeks. The dosing schedule consisted of 0.875 ml/kg (1st dose, week 1), 1.75 ml/kg (2nd to 9th dose, week 1 – 4), 2.5 ml/kg (10th to 23rd dose, week 4 – 8), and 3.25 ml/kg (after week 8). Upon completion of the CCl4 regimen, 1.5 x 106 Hepa1-6 or TiB75 cells were orthotopically implanted in their respective syngeneic mouse strains, C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ. Animals were sacrificed and tumor tissues were histopathologically evaluated 7 days post-tumor implantation. CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Ablation protocol

Seven days post-tumor injection, mice with a single targetable lesion were randomly assigned to either pCryo (n = 8) or no treatment (n = 8) groups (Fig. 2). pCryo was performed using a clinical Visual-ICE™ Cryoablation System (Boston Scientific, Boston, MA). A 1.2 mm surface cryoprobe (Galil Medical ICEx Cryoablation System, Boston Scientific, Boston, MA) was carefully placed on the laparoscopically exposed targeted lesion, undergoing two freezing cycles at the targeted temperature of -40 °C for 50 s-active freezing each, with a 1-minute break between cycles. The probe, positioned at an angle of 80-90° with its tip reaching the middle of the tumor’s long axis, ensured pCryo. After the freeze-thaw cycle, warmed saline solution was instilled into the abdominal cavity, and the fascia and skin were closed in layers.

Fig. 2.

Illustrative representation of experimental design for MR-based imaging of T lymphocytes in immunophenotypically diverse HCC mouse models.

(A) Establishment of immunologically “hot” and “cold” syngeneic murine HCC models in toxin-induced underlying cirrhosis. (B) Animals were randomly assigned to receive pCryo on day 7 post- HCC tumors in both syngeneic models. Systemic administration of 2.4 mg/kg 160Gd-CD8 (n = 8/each) was given 7 days post-pCryo. (C) 24 h after systemic administration of 160Gd-CD8, animals were subjected to T1-weighted MRI, revealing hyperintensity in the peritumoral rim and successful in vivo labeling of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Radiological-pathological correlation was confirmed with immunohistochemistry and imaging mass cytometry. 160Gd, gadolinium 160; CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NK, natural killer; pCryo, partial cryoablation; Treg, regulatory T.

Labeling of CD8 antibody with 160Gd

The purified anti-mouse CD8+ antibody (4SM15, ThermoFisher, 14-0808-37) was labeled with gadolinium 160 (160Gd) lanthanide using MAXPAR® X8 Antibody Labeling Kit (Fluidigm, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (supplementary materials and methods). Imaging mass cytometry (IMC) of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples stained with 160Gd-CD8 antibody confirmed labeling efficacy. Constant unchanged binding sensitivity and specificity were confirmed by comparing the spatial signal distribution from 160Gd on IMC and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) on immunofluorescence (IF) of stained samples with an anti-rat FITC-conjugated antibody.

Imaging mass cytometry

Automated ablation of FFPE samples was performed with a Hyperion imaging system coupled with a Helios mass cytometer (Fluidigm, CA). Analysis of distribution and intensity was performed for each pixel using the MCD Viewer (Fluidigm, CA) (supplementary materials and methods). To distinguish the 160Gd-tagged metal signal from the background, untagged CD8 served as a negative control (Fig. S2B).

Ex vivo cross-validation of metal-labeled anti-CD8+ antibody

To confirm antibody binding specificity after metal labeling, FFPE samples previously validated for a CD8+ signal by IHC were stained with the 160Gd-CD8 antibody. IMC analysis was performed to validate successful antibody labeling and assess spatial signal distribution in three regions: the ablated zone, liver parenchyma, and spleen (which served as a positive control).

Systemic delivery of 160Gd-labeled anti-CD8+ antibody

For in vivo MRI of CD8+ T cells, retro-orbital injection of 160Gd-CD8+ was used at a concentration of 2.4 mg/kg body weight, based on previous studies using 160Gd-labeled antibodies.20 Local accumulation of CD8+ T cells was visualized with T1-weighted MRI and cross-validated histologically with IMC and IHC.

Tissue harvesting and processing

Harvested tumor tissues were fixed in 10% formalin at 4 °C, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned into 5 μm-thick slices. H&E staining was used to assess gross histopathology, while immune infiltrates were assessed with IHC staining of T lymphocytes (CD3+ and CD8+), macrophages (CD68+). Masson’s trichome staining evaluated cirrhosis. Samples were digitized at 20X magnification and quantified with ImageScope v12.3 software (Leica Biosystems Imaging, Inc., Vista, CA) using a positive pixel count algorithm23 (supplementary materials and methods).

Flow cytometry

A total of 14 additional mice per tumor type (6 mice per group, with a 5% drop out rate and 10% adjustment for cirrhosis induction loss, resulting in approximately 14 mice) were used for flow cytometry analysis of immune infiltration in intrahepatic and draining lymph node tissues, either under control conditions or following pCryo (Ntotal = 28). Tumor, tumor-adjacent tissues, and draining lymph node tissues (inguinal and mesenteric) were prepared and stained with antibodies specific for surface markers Thy1.2 (clone 30-H12; ThermoFisher), CD3 (clone 17A2; eBioscience), CD4 (clone RM4-5; Invitrogen), CD8 (clone 53–6.7; BioLegend) and CD11b (M1/70; BioLegend). Spleen samples were collected and served as positive controls. Flow cytometric analysis was conducted using a CytoFlex flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and cell percentages were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10.9, BD Life Sciences). The gating strategy is illustrated in Fig. S3, with further details provided in the supplementary materials and methods.

MRI protocol

MRI data were acquired using a horizontal-bore 9.4 T Bruker scanner (Billerica, MA, USA) with ParaVision 6 software. The protocol included respiratory-gated T1-weighted sequences, using FLASH (Fast Low Angle Shot) and RARE (Rapid Acquisition with Relaxation Enhancement) for radiofrequency coil positioning on the liver. T1-weighted MSME (multi-slice/multi-echo) imaging used the following parameters: TR = 1,500 ms, TE = 5.46 ms, resolution = 256 x 128, FOV=28 x 50 mm2, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, 20 slices. The same protocol was applied for both pre-contrast and post-contrast MR sessions.

MRI data analysis

MRI data were quantitatively analyzed using a DICOM-based software (Radiant DICOM-Viewer 2020.2). Changes in signal intensity (SI) before and after contrast administration were determined by measuring the mean SI of three distinct regions of interest (ROI) along the periablational rim. For both the ablation zone and normal liver parenchyma, the mean intensity was calculated for an ROI of 1-3 mm2 at each timepoint. To assess the relative signal intensity (rSI), the mean SI of the peritumoral rim ROI was divided by the mean SI of the normal liver ROI (rSI = [SI of TZ]/[SI of normal liver tissue]). Additionally, the signal-to-noise ratio was calculated as the ratio between the mean ROI signal and its standard deviation.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± standard deviation for replicate measurements. Normality was assessed using appropriate tests. For non-normally distributed data, the independent non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparisons among multiple groups. When data met the assumption of normality, an unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction was applied to compare two variables. Additionally, a two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons test was performed to account for interaction effects. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (Version 10.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

Results

Establishment of syngeneic “hot” and “cold” HCC tumors on a cirrhotic background

Repetitive CCl4 exposure resulted in cirrhosis in all animals. Histopathological evaluation showed the presence of a single intrahepatic tumor growing in a cirrhotic liver in all animals (Fig. 3A). Masson’s trichrome staining demonstrated the presence of cirrhosis throughout the liver tissue (Fig. 3B). Fibrosis index corresponding to Masson’s trichrome staining in ImageScope shows more fibrosis in CCl4-treated animals (46.63 ± 4.1) compared to controls (14.25 ± 2.9) (p <0.00001, by Student’s t test) (Fig. 3C). Further histopathological analysis of both tumors with IHC staining of CD3+ and CD68+ markers revealed less infiltration of pro-inflammatory cells in Tib75 tumors due to their immunosuppressive TME (Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

Syngeneic murine HCC tumor in cirrhotic background.

(A) Gross pathology of CCl4-treated mice showing anterior images of orthotopic HCC tumor in a cirrhotic liver (from Hepa1-6-tumor-bearing mouse). (B) Histopathological evaluation of cirrhosis assessed with Masson’s trichome. (C) Quantification as the ratio of the fibrosis area to the total sample area, expressed in pixels in Masson’s trichome staining. Comparison of two variables was performed with an unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction. ∗p <0.01, ∗∗∗p <0.0001. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0.

Partial cryoablation enhances effector T-cell responses in the immunogenic tumor microenvironment

The impact of pCryo on T-cell recruitment in different tumor types was assessed ex vivo using IHC and analysis. CD8+ expression in histological samples of residual tumors was significantly higher in treated tumors (0.62 ± 0.3) compared to the control group (0.40 ± 0.1) (p <0.005), indicating the immunomodulatory effects of pCryo on the TME (Fig. 4). The presence of CD8+ T lymphocytes was more prominent in Hepa1-6 tumor-bearing mice than TiB75 tumor-bearing mice either before (0.52 ± 0.05, Hepa1-6; 0.30 ± 0.02, TiB75) or after pCryo (0.86 ± 0.03, Hepa1-6; 0.37 ± 0.07, TiB75) (p <0.00001), confirming the immunogenic nature of those cell lines. Due to relatively higher baseline T-cell infiltration and presence of a distinct rim of T cells in the peri-ablational zone, Hepa1-6 was designated as an immunogenic or “hot” tumor. Notably, cryoablation further augmented T-cell infiltration within the TME of “hot” Hepa1-6 tumors (0.86 ± 0.03) (p <0.0001). Meanwhile, due to low baseline T-cell infiltration, TiB75 was designated as a non-immunogenic or “cold” tumor. pCryo failed to induce further T-cell infiltration within TiB75 tumors (0.37 ± 0.07) (p = 0.1). Thus, immunogenic Hepa1-6 tumor-bearing mice were used to test and validate 160Gd-labeled antibody MRI, owing to the formation of a solid rim of infiltrating cytotoxic T cells in the peri-ablational zone. Conversely, TiB75 tumor-bearing mice served as a negative control due to the scarcity of infiltrating CD8+ T cells before and after pCryo treatment.

Fig. 4.

Partial cryoablation enhances cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell response in immunogenic tumor microenvironment.

(A) IHC staining of CD8+ marker at 7 days post-tumor implantation (control, left column) and at 7 days post-pCryo (treated, right column) in both immunogenic (top row) and non-immunogenic (bottom row) HCC cell lines. The boxes represent selected area for 20X magnification (B) CD8+ stain quantification in residual tumor tissue. Percentage of positive CD8+ = Npositive/Ntotal. Comparison of two variables was performed with an independent non-parametric Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis test. ∗p <0.01, ∗∗∗p <0.0001. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0. IHC, immunohistochemistry; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NL, normal liver; pCryo, partial cryoablation; T, residual tumor.

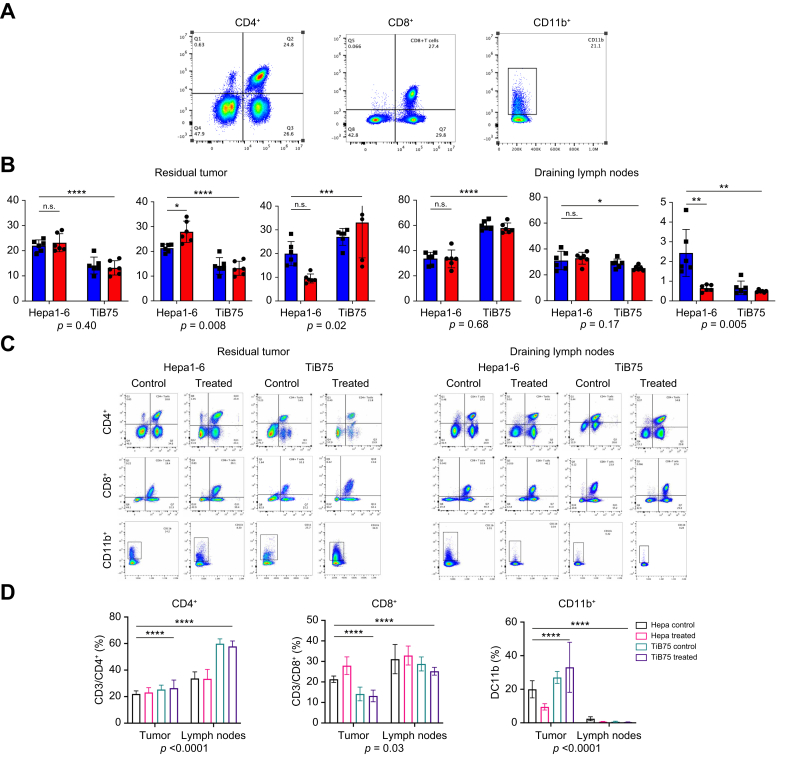

Local and systemic immunomodulatory effects of partial cryoablation are tumor type-dependent

To assess the impact of tumor type and pCryo on immune cell infiltration, we measured the percentages of CD8⁺, CD4⁺, and CD11b⁺ cells in both tumor (local) and lymph node (systemic) samples (Fig. 5). In tumors, pCryo significantly increased CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration compared to controls (20.56% vs. 17.73%; p = 0.0415), with a more pronounced effect in immunogenic Hepa1-6 tumors, suggesting that pCryo enhances CD8⁺ recruitment in pro-immunogenic tumor types, as further confirmed by histology. Additionally, a significant interaction between tumor type and treatment (p = 0.0087) indicates that the effect of pCryo on CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration depends on tumor type. Notably, CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration was significantly higher in lymph nodes compared to tumors (32.00% vs. 24.62%; 95% CI -11.49 to -3.274; p = 0.0013), but pCryo had minimal impact on systemic CD8⁺ recruitment (Fig. 5C). For CD4⁺ T cells, pCryo did not significantly affect infiltration in tumors (p = 0.9312), and no interaction between tumor type and treatment was observed (p = 0.4070). However, baseline CD4⁺ levels differed significantly between Hepa1-6 and TiB75 tumors both locally (22.58% vs. 13.67%, p <0.0001) and systemically (33.57% vs. 58.88%, p <0.0001), with a marked difference between the two tissues (46.23% in lymph nodes vs. 24.23% in tumors; 95% CI -24.69 to -19.30). This demonstrates inherent immunological differences between the tumor types.

Fig. 5.

Local and systemic immunomodulatory effects of partial cryoablation are tumor type dependent.

Immune cell populations in draining lymph nodes and in the tumor microenvironment. (A) Representative flow cytometry staining for CD3+/CD4+, CD3+/CD8+ co-expression in CD90 gate, and CD11b+ cells (spleen sample). (B) Percentages of CD3+/CD4+, CD3+/CD8+, and CD11b+ cells in tumor and lymph node samples from Hepa1-6 and TiB75 tumor-bearing mice, without (control, blue color) and with cryoablation (treated, red color). (C–D) Comparison of immune cell population per group in both tumor and lymph node tissues. p values represent significance of interaction between treatment and tissue type. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, with differences assessed using two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance: ∗p <0.01, ∗∗∗p <0.001, ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001.

CD11b⁺ myeloid cell analysis revealed that pCryo’s effect was tumor type dependent (p = 0.0217), with a stronger response in immunogenic Hepa1-6 tumors. The response to pCryo was significantly stronger in tumors (22.39%) than in lymph nodes (1.06%), with a marked difference between these tissues (95% CI 17.97–24.70) (Fig. 5C). pCryo induced a robust recruitment of CD11b⁺ cells in tumors, particularly in immunogenic tumors, suggesting a potential immune-priming effect that may be more pronounced locally. Both tumor type and treatment also had significant effects systemically (p <0.0001 for both), though the recruitment of CD11b⁺ cells in lymph nodes remained much lower.

In vivo MRI of effector T cells in “hot” and “cold” HCC tumors with dedicated 160Gd-labeled CD8 antibodies

T1-weighted multi-slice/multi-echo MRI was performed at baseline and 24 h after systemic injection of 2.4 mg/kg 160Gd-CD8 antibody. The immunogenic tumor-bearing group exhibited a selective rim enhancement in the peritumoral zone, measuring an average of 176 ± 0.3 μm in the coronal plane. Conversely, no enhancement was observed in the non-immunogenic tumor-bearing mice. The liver-to-muscle ratios before and after contrast administration were determined as 0.97 ± 0.02 and 0.65 ± 0.04, respectively (p = 0.001). Upon systemic administration of 160Gd-CD8 antibody, the peritumoral rim-to-muscle ratio was 0.92 ± 0.07, and the mean rSI was 1.24 ± 0.01. A radiological-pathological comparison of MRI with ex vivo IMC showed that the observed signal distribution of 160Gd on MRI was consistent with the deposition of 160Gd within the peritumoral rim on IMC (Fig. 6). Ex vivo IMC also correlated well with CD8+ T-cell peritumoral infiltration on IHC (0.62 ± p <0.001) (Fig. 7). Ex vivo IF using FITC-conjugated anti-rat secondary antibodies further validated the unchanged binding sensitivity and specificity of 160Gd-labeled CD8 antibodies to their specific target. By comparing the distribution of the 160Gd signal on IMC with that of the FITC signal on IF, metal labeling did not affect binding specificity of the anti-CD8 antibody (Fig. S2A). IMC analysis of FFPE spleen samples, obtained 24 h after the systemic administration of 160Gd-CD8, further confirmed binding specificity, as the 160Gd signal was primarily detected in the splenic red pulp. Paraffin wax without embedded tissue (negative control) showed non-specific background signals without a cellular distribution pattern (Fig. S2B).

Fig. 6.

In vivo molecular imaging of peritumoral infiltrating cytotoxic T cells using 160Gd–labeled CD8+ antibodies.

Radiological-pathological correlation of in vivo labeling of tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic T cells in both immunogenic (top row) and non-immunogenic (bottom row) HCC models. Immunohistochemistry assessment of CD8+ before and after pCryo (two left columns) shows enhanced T-cell tumor infiltration in immunogenic HCC model. A baseline T1-weighted coronal MRI scan of both tumor types (∗)7 days post-pCryo with 0.1 mmol/kg intravenous Dotarem contrast (third column). Peritumoral rim enhancement (arrows) on T1-weighted coronal MRI scan (repetition time, 1,500 ms; echo time, 5.46 ms) obtained 24 h after systemic administration of 160Gd-labeled CD8+ antibody (fourth column) indicates peritumoral cell infiltrate in immunogenic HCC tumors, as observed histologically. Bright field image from ex vivo IMC from animals (fifth column) after ablation of specific in vivo labeling of infiltrating T cells by 160Gd-CD8+. 160Gd, gadolinium 160; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IMC, imaging mass cytometry; LRT, locoregional treatment (pCryo); pCryo, partial cryoablation; T, tumor.

Fig. 7.

160Gd metal concentration in the peritumoral rim by imaging mass cytometry.

(A) Correlation of CD8+ positive signal on IHC and spatial localization of 160Gd metal distribution using IMC. (B) Histopathological analysis of ex vivo IMC and IHC from 7 days pCryo animals following 24 h post-160Gd-CD8+ antibody intravenous injection. Bright field image from IMC (left column) and IHC staining of CD8+ marker (right column). The boxes in upper row of B indicates the area of magnification for the bottom row. 160Gd, gadolinium 160; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IMC, imaging mass cytometry; pCryo, partial cryoablation.

Discussion

This study offers valuable insights into the potential of pCryo as an immunomodulatory therapy in HCC. It also establishes a reliable MR-based molecular imaging method to visualize CD8+ anti-tumor T-cell infiltration following pCryo in both "cold" and "hot" murine tumors within the context of induced cirrhosis. By using CCl4 to induce cirrhosis, the study creates a more clinically relevant environment for modeling HCC, closely mimicking the conditions leading to HCC development. This allows for an accurate assessment of pCryo's impact on immune infiltration on a cirrhotic background. Utilizing immune cell-specific 160Gd-labeled antibodies, the study detected peritumoral infiltrating T cells, correlating curvilinear distribution patterns observed on MRI with histopathological confirmation after pCryo. These findings not only build upon proof-of-principle data using 160Gd-based MRI for macrophage visualization in hepatic radiofrequency ablation (RFA) settings,20 but also extend this technology to encompass various immune cell types in different HCC immune phenotypes.

In this study, “partial cryoablation” was designed to freeze a targeted portion of the tumor, as opposed to full tumor ablation. This approach aimed to induce a local immune response by preserving part of the tumor (residual tumor), which serves as an antigen reservoir to stimulate T-cell recruitment and activation. In general, tumors that provoke an immune response, often known as "hot tumors," are believed to display greater responsiveness to immunomodulatory therapies when compared to "cold" tumors lacking substantial immune cell infiltration.24 Cryoablation is considered the most effective method for triggering an anti-tumor immune response due to its ability to preserve antigen integrity, cellular structure, and increase membrane permeability.25 This stands in contrast to the protein denaturation caused by hyperthermia.26 Nevertheless, the presented data suggest that the immunomodulatory effects of pCryo may be linked to specific TMEs, as it augmented the anti-tumor immune response in already immune-primed tumors, while demonstrating a relatively weak and transient effect in non-immunogenic tumors.

The immunogenic Hepa1-6 tumors showed higher baseline infiltration of CD8⁺ and CD4⁺ T cells, distinguishing them from the non-immunogenic TiB75 tumors, which exhibited lower T-cell infiltration. Given that TiB75 is recognized for its well-established immunosuppressive TME,21 it is plausible that the influence of its stroma could still impact an ablation-induced anti-tumor immune response and impede immunosurveillance. Indeed, pCryo significantly enhanced CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration in Hepa1-6 tumors, reinforcing the concept that pCryo can modulate the TME of immunogenic tumors by augmenting local effector T-cell recruitment. This is critical because effective T-cell infiltration is often associated with better anti-tumor immunity and improved treatment outcomes. In contrast, the limited impact of pCryo on TiB75 tumors, which remained largely devoid of CD8⁺ cells post-treatment, underscores the resistance of non-immunogenic tumors to local immunomodulatory strategies like cryoablation. This differential response suggests that pCryo alone may not be sufficient to stimulate local anti-tumor immunity in "cold" tumors, where additional systemic interventions, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors or adoptive T-cell therapies, might be necessary to overcome the immunosuppressive TMEs.

Despite being extensively used in other cancer types, the application of cryoablation in HCC has been poorly studied and clinically underutilized.27 In comparison to RFA, cryoablation offers distinct benefits such as larger ablative zones, well-defined treatment margins, reduced pain, and better suppression of ectopic tumors.28 Additionally, extensive analysis shows cryoablation’s efficacy and safety for advanced HCC, with lower residual tumor rates and recurrence after partial treatment compared to RFA.29 While cryoablation is less commonly used in HCC treatment compared to other ablative therapies, the findings from this syngeneic mouse model suggest that it could be an effective strategy for enhancing anti-tumor immune responses, particularly in immunogenic tumors. Given cryoablation’s ability to modulate the TME in pre-existing immunogenic tumors, leveraging this local therapy to transform the TME of residual tumors into a more receptive immunological state and integrating it with systemic immunotherapy emerges as an appealing strategy for metastatic HCC treatment. Thus, the proposed MR-based probe for monitoring T-cell infiltration in patients holds significant predictive value as it represents a biomarker for selecting interventions and monitoring treatment success. Furthermore, these tools can help differentiate real tumor growth from unusual post-treatment responses, such as pseudo-progression, induced by immune cells infiltrating the TME.30

Most current preclinical checkpoint imaging studies primarily visualize PD-L1 expression in tumor cells or the TME.31 For instance, Keskamp et al. demonstrated intra-tumoral heterogeneity in xenograft tumor models using specific radiolabeled anti-PD-L1.32 However, these experiments were restricted to xenograft immunodeficient mice, precluding assessment of PD-L1 expression on immune cells. Moreover, the use of radioactive tracers in these studies may pose long-term risks for clinical translation due to repetitive exposure. Additionally, the spatial resolution of CT/PET-based imaging may be insufficient for precise localization in small or deep-seated structures, potentially impacting diagnostic accuracy,33 and leading to inappropriate treatment decisions or delayed interventions. The proposed MR-based imaging technique in this study aims to address these issues associated with PET/CT technologies. With high spatial resolution, MRI can detect small lesions and subtle changes in immune-related structures,34 offering a safer option for patients due to non-ionizing radiation, particularly in repeated or longitudinal imaging studies.35 These advantages position MR-based molecular imaging as a promising, comprehensive, and safer approach to assess immune responses in various diseases and treatment settings.

While this study shows the potential of molecular imaging with MRI, there are some weaknesses that could be addressed in the future. The study utilized a single time point (24 h) for imaging CD8+ T-cell accumulation post-pCryo. Longitudinal imaging at multiple time points would provide insights into the dynamics of T-cell infiltration and assess the persistence of the immune response over time. Additionally, investigating the correlation between CD8+ T-cell infiltration and treatment outcomes, such as tumor regression or overall survival, would further establish the clinical relevance of the imaging technique. Future studies could explore the use of multiplex imaging techniques to visualize and quantify multiple immune cell subsets simultaneously, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the immune landscape in HCC tumors and possibly discerning the degree of immune responses between effective and ineffective immunotherapies.

In summary, this study introduces a novel non-invasive imaging approach for CD8+ T lymphocytes in HCC tumors pre- and post-pCryo using 160Gd-based contrast agents. The findings hold significance for molecular imaging and HCC management, particularly in the context of immunotherapy, suggesting potential advances in patient selection, treatment monitoring, and combining pCryo with immunotherapy. However, further research is required to validate these findings in patients, explore other immune cell subsets, incorporate longitudinal imaging, and establish the clinical relevance of the technique. Addressing these limitations will facilitate the translation of this imaging approach into clinical practice, enhancing patient stratification and personalized treatment decisions.

Abbreviations

160Gd, gadolinium 160; CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; pCryo, partial cryoablation; IF, immunofluorescence; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IMC, imaging mass cytometry; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; ROI, region of interest; (r)SI, (relative) signal intensity; TME, tumor microenvironment.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Society of Interventional Oncology Grant 19-001324, the National Institute of Health grant R01 CA206180, and R21 grant R21CA274152.

Authors’ contributions

Guarantors of integrity of entire study, J.G.S: A.S, and J.C; study concepts/study design: J.G.S, J.C; data acquisition and data interpretation: J.G.S, J.C, D.C; manuscript drafting or manuscript revision for important intellectual content: all authors; approval of final version of submitted manuscript: all authors; agrees to ensure any questions related to the work are appropriately resolved: all authors; literature research: J.G.S., A.S, D.N, J.C, D.C, F.H.; experimental studies: J.G.S., A.S., D.N., J.C; statistical analysis: J.G.S, J.C, D.C; and manuscript editing: all authors.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Data availability statement

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

Please refer to the accompanying ICME disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Yale Liver Cancer Award (NIH P30 DK034989) Microscopy Core for their support with resources and expertise and thank Boston Scientific and Guerbet for providing materials for this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101294.

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Chidambaranathan-Reghupaty S., Fisher P.B., Sarkar D. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): epidemiology, etiology and molecular classification. Adv Cancer Res. 2021;149:1–61. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leong T.Y., Leong A.S. Epidemiology and carcinogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2005;7(1):5–15. doi: 10.1080/13651820410024021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y.S., Lian L.F., Xu Y.H., et al. [Association of glycosylated hemoglobin level at admission with outcomes of intracerebral hemorrhage patients] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2019;40(11):1445–1449. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noor M.T., Manoria P. Immune dysfunction in cirrhosis. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2017;5(1):50–58. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2016.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardarelli-Leite L., Hadjivassiliou A., Klass D., et al. Current locoregional therapies and treatment strategies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Oncol. 2020;27(Suppl 3):S144–S151. doi: 10.3747/co.27.7171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marquardt J.U., Saborowski A., Czauderna C., et al. The changing landscape of systemic treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: new targeted agents and immunotherapies. Targeted Oncol. 2019;14(2):115–123. doi: 10.1007/s11523-019-00624-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Khoueiry A.B., Sangro B., Yao T., et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao Y., Yu C., Chein X., et al. PET/CT molecular imaging in the era of immune-checkpoint inhibitors therapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1049043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu K.F., Dupuy D.E. Thermal ablation of tumours: biological mechanisms and advances in therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(3):199–208. doi: 10.1038/nrc3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cazzato R.L., Garnon J., Ramamurthy N., et al. Percutaneous image-guided cryoablation: current applications and results in the oncologic field. Med Oncol (Northwood, Lond England) 2016;33(12):140. doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0848-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erinjeri J.P., Clark T.W. Cryoablation: mechanism of action and devices. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(8 Suppl):S187–S191. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.12.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yakkala C., Lai-Lai Chiang C., Kandalaft L., et al. Cryoablation and immunotherapy: an enthralling synergy to confront the tumors. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2283. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X., Bischof J.C. Quantification of temperature and injury response in thermal therapy and cryosurgery. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2003;31(5–6):355–422. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v31.i56.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao Q., O'Flanagan S., Lam T., et al. Engineering T cell response to cancer antigens by choice of focal therapeutic conditions. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36(1):130–138. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2018.1539253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He K., Liu P., Xu L.X. The cryo-thermal therapy eradicated melanoma in mice by eliciting CD4(+) T-cell-mediated antitumor memory immune response. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(3):e2703. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benzon B., Glavaris S.A., Simons B.W., et al. Combining immune check-point blockade and cryoablation in an immunocompetent hormone sensitive murine model of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21(1):126–136. doi: 10.1038/s41391-018-0035-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim D.W., Haymaker C., McQuail N., et al. Pilot study of intratumoral (IT) cryoablation (cryo) in combination with systemic checkpoint blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma (MM) J Immunother Cancer. 2015 Nov 4;3(Suppl 2):P137. doi: 10.1186/2051-1426-3-S2-P137. eCollection 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McArthur H.L., Diab A., Page D.B., et al. A pilot study of preoperative single-dose ipilimumab and/or cryoablation in women with early-stage breast cancer with comprehensive immune profiling. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(23):5729–5737. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keenan B.P., Fong L., Kelley R.K. Immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: the complex interface between inflammation, fibrosis, and the immune response. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):267. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0749-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santana J.G., Petukhova-Greenstein A., Gross M., et al. MR imaging-based in vivo macrophage imaging to monitor immune response after radiofrequency ablation of the liver. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023;34(3):395–403.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2022.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zabransky D.J., Danilova L., Leatherman J.M., et al. Profiling of syngeneic mouse HCC tumor models as a framework to understand anti-PD-1 sensitive tumor microenvironments. Hepatology. 2023;77(5):1566–1579. doi: 10.1002/hep.32707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim Y.O., Popov Y., Schuppan D. Optimized mouse models for liver fibrosis. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1559:279–296. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6786-5_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García-Rojo M., Sánchez J.R., de la Santa E., et al. Automated image analysis in the study of lymphocyte subpopulation in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-S1-S7. Suppl 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gajewski T.F., Corrales L., Williams J., et al. Cancer immunotherapy targets based on understanding the T cell-inflamed versus non-T cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1036:19–31. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-67577-0_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z., Meng L., Zhang J., et al. Progress in the cryoablation and cryoimmunotherapy for tumor. Front Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1094009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D.K., Han K., Won J.Y., et al. Percutaneous cryoablation in early stage hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of local tumor progression factors. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26(2):111–117. doi: 10.5152/dir.2019.19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tatli S., Acar M., Tuncali K., et al. Percutaneous cryoablation techniques and clinical applications. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2010;16(1):90–95. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.1922-08.0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y., Wang C., Lu Y., et al. Outcomes of ultrasound-guided percutaneous argon-helium cryoablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19(6):674–684. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0490-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rong G., Bai W., Dong Z., et al. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous cryoablation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma within Milan criteria. PLoS One. 2015;10(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onesti C.E., Frères P., Jerusalem G. Atypical patterns of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors: interpreting pseudoprogression and hyperprogression in decision making for patients' treatment. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(1):35–38. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.12.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bensch F., van der Veen E.L., Lub-de Hooge M.N., et al. 89Zr-atezolizumab imaging as a non-invasive approach to assess clinical response to PD-L1 blockade in cancer. Nat Med. 2018;24(12):1852–1858. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heskamp S., Wierstra P.J., Molkenboer-Kuenen J.D.M., et al. PD-L1 microSPECT/CT imaging for longitudinal monitoring of PD-L1 expression in syngeneic and humanized mouse models for cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(1):150–161. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahl R.L., Herman J.M., Ford E. The promise and pitfalls of positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography molecular imaging-guided radiation therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2011;21(2):88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez de Lizarrondo S., Jacqmarcq C., Naveau M., et al. Tracking the immune response by MRI using biodegradable and ultrasensitive microprobes. Sci Adv. 2022;8(28):eabm3596. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarthy C.E., White J.M., Viola N.T., et al. In vivo imaging technologies to monitor the immune system. Front Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.