Highlights

-

•

Low acetate kinase (AckA) confers resistance to arsenite in Lacticaseibacillus paracasei.

-

•

Expression of acetate kinase (ackA) is indirectly controlled by PhoPR two component system.

-

•

PhoP appears to affect a significant portion of Lc. paracasei genesPhoP directly regulates pst and phn operons as well as glnA gene.

Keywords: Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, Arsenite, Phosphate, Acetate kinase, Pho regulon

Abstract

In bacteria, the two-component system PhoPR plays an important role in regulating many genes related to phosphate uptake and metabolism. In Lacticaseibacillus paracasei inactivation of the response regulator PhoP results in increased resistance to arsenite [As(III)]. A comparative transcriptomic analysis revealed that the absence of PhoP has a strong effect on the transcriptome, with about 57.5 % of Lc. paracasei genes being differentially expressed, although only 92 of the upregulated genes and 23 of the downregulated genes reached a fold change greater than 2. Among them, the phnDCEB cluster, encoding a putative ABC phosphonate transporter and the acetate kinase encoding gene ackA (LCABL_01600) were downregulated tenfold and sevenfold, respectively. In vitro binding assays with selected PhoP-regulated genes showed that phosphorylation of PhoP stimulated its binding to the promoter regions of pstS (phosphate ABC transporter binding subunit), phnD and glnA glutamine synthetase) whereas no binding to the poxL (pyruvate oxidase) or ackA putative promoter regions was detected. This result identified for the first time three genes/operons belonging to the Pho regulon in a Lactobacillaceae species. Mapping of the reads obtained in the transcriptomic analysis revealed that transcription of ackA was severely diminished in the PhoP mutant after a hairpin structure located within the ackA coding region. Inactivation of phnD did not affect As(III) resistance whereas inactivation of ackA resulted in the same level of resistance as that observed in the PhoP mutant. These finding strongly suggests that PhoP mutant As(III) resistance is due to downregulation of ackA. Possible mechanisms of action are discussed.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Arsenic (As) is a widespread contaminant present in food and drinking water, with its inorganic forms, arsenite [As(III)] and arsenate [As(V)], being the most toxic species found. Many Lactobacillaceae species are associated with food products, plants, and animals and are consequently also exposed to As, albeit at low levels. As(III) is a potent inhibitor of a number of enzymes due to its high affinity for sulfhydryl groups such as those exposed by reduced cysteine residues in proteins (Shen et al., 2013). As(III) binding to a protein can modify its conformation, block its activity and alter its interactions with other cell components. On the other hand, arsenate [(AsV)], which structurally resembles the orthophosphate anion (Pi), can possibly enter the cells by the same natural mechanisms as phosphate and replace it in some biochemical reactions (Shen et al., 2013). The main assimilable form of phosphorus in bacteria is phosphate (Santos-Beneit, 2015). Maintenance of Pi levels is of fundamental importance for the cell physiology. This process requires the concerted action of numerous proteins whose expression in bacteria is usually controlled by a global regulatory mechanism designated as the phosphate (Pho) regulon. The Pho regulon was first characterized in Escherichia coli (Gardner and McCleary, 2019; Wanner and Latterell, 1980) and subsequently in other model bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis (Hulett, 1996; Salzberg et al., 2015) or Streptomyces coelicolor (Barreiro and Martínez-Castro, 2019; Sola-Landa et al., 2005).

The Pho regulon is controlled by a two-component signal transduction system (TCS) which consists of a membrane histidine kinase sensor protein (HK) and a cytoplasmic transcriptional response regulator (RR). These two proteins are named PhoB and PhoR in E. coli although they have been named differently in other bacteria (Santos-Beneit, 2015). The Pho sensor kinase responds to Pi shortage phosphorylating its cognate RR. The phosphorylated RR recognizes specific DNA sequences, PHO boxes, thereby regulating the expression of the corresponding genes. The PHO box consensus sequences varies from one species to another and, even within the same organism, they may display considerable differences that results in different RR-DNA binding affinities (Santos-Beneit, 2015). In E. coli, the PHO box consists of two direct repeats of 11 bp (Blanco et al., 2002) where the most conserved motif is CTGTCAT (Yoshida et al., 2012). In B. subtilis, it consists of four TT(A/T/C)ACA-like sequences with an 11-bp periodicity (Eder et al., 1999). Regulatory circuits can also widely vary between different bacteria. In E. coli, the activity of the PhoBR TCS is linked to the activity of the phosphate ABC transporter PstSCAB2. Under low-phosphate conditions, the conformational changes derived via transport through PstSCAB1B2 are sensed by the auxiliary regulator PhoU, that interacts with the sensor kinase PhoR and activates its phosphorylation function on PhoB (Gardner et al., 2014; Gardner and McCleary, 2019). In contrast, synthesis of wall teichoic acids (WTA) controls the activity of PhoR in B. subtilis (Botella et al., 2014). An intermediate of WTA synthesis interact with the PAS domain of PhoR thereby inhibiting its autokinase activity. When phosphate becomes limiting, PhoR kinase activity is initially triggered by an unknown mechanism that leads to a low-level PHO response. Its phosphorylated cognate RR PhoP (PhoP∼P) diminishes WTA synthesis by repressing the expression of tagAB thus amplifying the PHO response (Botella et al., 2014).

Information on phosphate metabolism is far more limited in other bacterial groups such as Lactobacillales. Order Lactobacillales is a group of low-GC gram-positive, nonsporulating, fermentative and generally acid tolerant bacteria. The group encompasses relevant pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, commensal or opportunistic pathogens such as Enterococcus faecalis, bacteria involved in food fermentation processes such as Lactococcus lactis, or probiotic bacteria, such as Lacticaseibacillus paracasei. First studies in organisms of this group, i.e. E. faecalis and L. lactis, established that phosphate transport was dependent on ATP (Harold and Spitz, 1975; Poolman et al., 1987). The first evidence of the involvement of a Pho TCS and Pst ABC transporter in phosphate homeostasis in Lactobacillales was reported in S. pneumoniae by Novak et al. (1999). They identified a gene cluster consisting of a Pho TCS (pnpRS) followed by an operon encoding a Pst transporter (pstSCAB) and a putative auxiliary regulator (phoU). Inactivation of pstB had pleiotropic effects: in addition to decreased uptake of phosphate, the mutant displayed decreased transformation and lysis (Novak et al., 1999). A subsequent study showed that expression of the pst operon increased with decreased levels of Pi (Orihuela et al., 2001). A Pho TCS has been studied in Lacticaseibacillus paracasei BL23 (originally named TC04; PhoP RR, LCABL_10,480, PhoR HK, LCABL_10,490), showing that inactivation of phoP resulted in slow growth and acid sensitivity in MRS medium (Alcántara et al., 2011). This TCS was adjacent to a pstSCAB1B2-phoU gene cluster. A phylogenetic analysis of TCS encoded by Lactobacillaceae revealed that Pst transporter encoding genes are present in most members of this family (Zúñiga et al., 2011). In contrast, its cognate TCS is absent in some lineages, i.e. genus Lactobacillus, or incomplete. For example, Limosilactobacillus fermentum and Limosilactobacillus reuteri lack of PhoR homologs and their PhoP proteins widely diverge from other PhoP homologs (Zúñiga et al., 2011).

Recently, it has been shown that uptake of arsenate is possibly mediated by the Pst transporter in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum (Corrales et al., 2024). Remarkably, the inactivation of the PhoPR TCS resulted in increased resistance to As(III) in Lc. paracasei BL23 (Corrales et al., 2024). No obvious mechanism behind this phenotype has been identified. The mechanisms of As resistance have been minimally explored in Lactobacillaceae. However, the presence of plasmid-encoded arsA, arsB, arsD (two genes), and arsR genes, as well as a chromosome arsC gene, has been reported in Lp. plantarum WCFS1, where they have been shown to confer resistance to As (Kleerebezem et al., 2003; Kranenburg et al., 2005). The arsR, arsB and arsC genes code for a transcriptional regulator, an As(III) efflux antiporter, and an arsenate reductase, respectively. The arsA gene encodes an ATPase that associates with ArsB, enabling it function as an ATP-driven As(III) efflux pump. Additionally, arsD encodes a second regulator that also acts as an As(III) chaperone for ArsA (Andres and Bertin, 2016). Clusters of ars genes are present in other Lactobacillaceae species, often encoded in plasmids (Davray et al., 2021); however, Lc. paracasei BL23 lacks ars genes.

This study aims to gain insight into this effect by characterizing the PhoP RR and by a comparative transcriptomic analysis of Lc. paracasei BL23 and a cognate mutant derivative carrying an in-frame deletion of phoP. Although the evidence available so far suggest that the Pho system may play a relevant physiological role in Lactobacillaceae, no information is available about the genes under control of PhoPR and the regulation of its activity. The results obtained has allowed us to identify some members of the Pho regulon in this species and identify the downregulation of the expression of acetate kinase as responsible of the observed As(III) resistance.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial strains and culture media

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. Lacticaseibacillus strains were grown in MRS medium (BD-Difco) at 37 °C and in modified MEI medium (Landete et al., 2010) with high or low phosphate concentration [MEI (60 mM Pi) and LP-MEI (1 mM Pi), respectively]. E. coli strains were grown in LB medium at 37 °C with shaking. Agar (Condalab) was added at 1.8 % (w/v) for plates. When required, erythromycin was added at 5 µg/mL for Lacticaseibacillus strains. Ampicillin was added at 100 µg/mL and chloramphenicol at 34 µg/mL for E. coli strains.

Table 2.

Lacticaseibacillus strains and plasmids used in this work.

| Strain/plasmid | characteristics | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| Lc. paracasei BL23 | Wild type | Mazé et al. (2010) |

| Lc. paracasei DC399 | BL23 ΔphoP | Corrales et al. (2024) |

| Lc. paracasei DC491 | BL23 phnD::pRV300; Eryr | This work |

| Lc. paracasei DC492 | BL23 ΔackA | This work |

| pRV300 | Integrative vector for lactobacilli; Ampr, Eryr | Leloup et al. (1997) |

| pQE80 | 6 × (His) tagged proteins expression vector, lacIq; Ampr | Qiagen |

| pQEphoP | pQE80 expressing L. paracasei 6 × (His)PhoP | This work |

| pRVphnD | pRV300 with internal 520 bp phnD fragment | This work |

| pRVackA | pRV300 with flanking ackA fragments for deletion | This work |

Eryr, erythromycin resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistance.

2.2. Cloning, expression and purification of PhoP

Gene phoP was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of strain BL23 with primers PhoP-F/PhoP-R (Supplementary file 1, Table S4) using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific). The PCR product was purified with PureLink™ Quick Gel Extraction and PCR Purification Combo Kit (Invitrogen) and cloned into expression plasmid pQE-80 L (Qiagen) digested with BamHI and SmaI by using the GeneArt™ Gibson Assembly EX kit (Invitrogen). In this way, a gene encoding a fusion protein with a N-terminal 6 × (His) tag was obtained. The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli NZYa (NZYtech) following the instructions of the supplier. Transformants were selected in LB agar plates with ampicillin by colony PCR with primers pQE-F and pQE-R. Clones producing fragments of the expected size were selected and the integrity of the phoP sequence was verified by DNA sequencing. One plasmid (pQEphoP) was used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) (dcm ompT hsdS(rB-, mB-) gal λ(DE3)) carrying plasmid pLysS for use as an expression host.

For protein production, cultures (0.5 L) were grown in LB broth supplemented with ampicillin and chloramphenicol at 37 °C with shaking to an OD595 0.5. Protein expression was induced by adding 0.3 mM IPTG and incubation at 27 °C for 3 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with one volume of A buffer (sodium phosphate 20 mM [pH 7.4], NaCl 500 mM, imidazol 40 mM) and resuspended in 30 ml of A buffer supplemented with phenymethysulfonyl fluoride 1 mM. The cell suspension was sonicated at 200 W for four cycles of 60 s followed by 60 s of cooling with a Labsonic V sonicator (B. Braun). The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant filtered through a 0.45 μm pore size Filtropur S membrane (Sarstedt). The cleared extract was directly loaded onto a HisTrap FF crude column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated with buffer A and coupled to an Äktaprime FPLC system (Cytiva). After the passage of the sample, the column was washed with 10 mL of A buffer and the protein was eluted with an imidazole gradient (40 mM to 2 M) in A buffer. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and those containing purified protein were pooled and subjected to buffer exchange (Tris–HCl 50 mM pH 7.4; NaCl 100 mM; glycerol 10 %) with Amicon Ultra-15 10 K centrifugal filter device (Millipore). The protein was stored at −80 °C until use.

2.3. Gene expression experiments

Lc. paracasei BL23 and its derivative strain ΔphoP were grown in MEI or LP-MEI medium to OD595 of 0.3 and 0.6. Cells were washed with 50 mM EDTA pH 8 and total RNA was extracted with TRIzol according to the instructions of the supplier (Life Technologies). RNA samples were treated with TURBO DNA-free™ kit (Invitrogen) using the routine DNase I treatment outlined by the supplier in order to remove contaminating DNA. and analyzed for its integrity with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Samples with 23S/16S ratios lower than 0.85 were discarded. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg RNA using the SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer. Real-time qPCR was performed using a LightCycler®480 Real-Time PCR system (Roche Diagnostics, USA) with the NZYSpeedy qPCR Green Master Mix (2x) (NZYtech) and primer pairs targeting genes pstA, pstB2, pstC, pstS and phoU (Supplementary file 1, Table S4). Primers were designed by using the Primer-BLAST service (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast) in order to generate amplicons ranging from 100 to 150 bp in size. The housekeeping genes fusA, ileS, mutL and recA were used as reference (Landete et al., 2010). The cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of three steps consisting of denaturation at 94 °C for 10 s, 55 °C for 10 s, and 65 °C for 10 s. For each set of primers, the cycle threshold values (crossing point [CP]) were determined by the automated method implemented in the Lightcycler 480 software 1.5 (Roche). The relative expression based on the expression ratio between the target genes and reference genes was calculated using the software tool REST 2009 (relative expression software tool) (Pfaffl et al., 2002). REST takes into account the different PCR efficiencies of the gene of interest and reference genes and estimate differences in expression between control and treated samples in group means for statistical significance by randomisation tests. Linearity and amplification efficiency were determined for each primer pair. At least six replicates of every sample were assayed.

For transcriptomic analyses, three RNA samples of each strain grown in LP-MEI to OD595 of 0.6 from independent cultures were used. Library construction, sequencing and analysis was carried out at the Genomics Unit and the Omics Data Analysis Unit of the Central Service for Experimental Research (SCSIE) of the University of Valencia. Libraries were obtained from 250 ng of RNA by using the Illumina stranded total RNA libraty preparation with Ribo-Zero Plus kit (Illumina) according to the instructions of the supplier. Libraries were sequenced on an NextSeq 500 platform and 2 × 74 pb pair-end reads generated. Raw sequence reads were checked for quality, adapter trimmed and quality filtered using fastp v0.21 (Chen et al., 2018) and FastQC v0.11.5 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) tools. Alignment and quantitation was performed for trimmed data using STAR software ver. 2.7.9a (Dobin et al., 2012) and Htseq v2.03 (Anders et al., 2014) using Lc. paracasei BL23 genome (Acc. NC_010999.1). Alignment quality was evaluated with QualiMap (Okonechnikov et al., 2015). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified with the DESeq2 R/Bioconductor package (Love et al., 2014). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Subramanian et al., 2005) was performed using the tools implemented in the OmicBox software (BioBam). The RNAseq dataset used in this work has been deposited at NCBI (biosamples SAMN42836912 to SAMN42836917) and is available under Bioproject PRJNA1141229.

2.4. Identification of putative PhoP binding sites

The core Pho sequence identified in B. subtilis (Eder et al., 1999; Qi et al., 1997) was used to search similar sequences in closely related bacteria. A set of fourteen non-identical sequences was selected (Supplementary file 1, Table S2) and used to determine a conserved motif with the GLAM2 program (Frith et al., 2008) implemented in the MEME suite ver. 5.5.5. This motif was used to scan a dataset of upstream regions of all genes in the BL23 genome sequence (Acc. N° ASM2648v1) with GLAM2Scan for potential Pho binding sites. The procedure was repeated using three sequences from Lc. paracasei BL23 which were recognized by PhoP (see Results section) to search for additional putative PhoP binding sites.

2.5. Gene inactivation

An internal 520 bp fragment of gene phnD was amplified with NZYTaq II DNA polymerase (NZYtech) from Lc. paracasei BL23 chromosomal DNA with primers PhnDc-F and PhnDc-R (Supplementary file 1, Table S4). The PCR product was purified as indicated above and cloned into pRV300 digested with SmaI by using the GeneArt™ Gibson Assembly EX kit (Invitrogen). To inactivate gene ackA, an 18 bp deletion encompassing bases 48 to 65 of the gene coding sequence was introduced. This deletion generates a stop codon that results in premature translation termination. For this purpose, two flanking regions were amplified [primers AckAd1-F/AckAd1-R (857 bp) and AckAd2-F/AckAd2-R (865 bp), respectively] and cloned into pRV300 digested with SmaI with the GeneArt™ Gibson Assembly EX kit (Invitrogen). The ligation mixtures were transformed into E. coli NZYa (NZYtech) following the instructions of the supplier. Transformants were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with ampicillin, X-Gal (50 µg/mL) and IPTG. White colonies were checked by colony PCR with primers pRV300-F/pRV300-R. Clones producing fragments of the expected sizes were selected and the integrity of the insert sequences were verified by DNA sequencing. One clone was selected for each resulting plasmid (pRVphnD and pRVackA, respectively) and used to transform Lc. paracasei BL23. The strain was electroporated with a Gene Pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad) as previously described (Posno et al., 1991). For phnD transformants, plasmid integration at the correct locus was checked by PCR with one oligonucleotide which hybridized in the targeted gene outside the cloned fragment and an oligonucleotide hybridizing in the pRV300 plasmid (PhnD-chk/pRV300-R). Transformants were isolated on MRS plates with 5 μg/L erythromycin incubated at 37 °C. The use of pRVphnD led to obtain phnD disruption mutants by single cross-over integration. An integrant obtained with pRVackA was grown for approximately 200 generations in the absence of antibiotic and strains were selected where the plasmid was lost by a second recombination event leading to loss of antibiotic resistance and ackA deletion, as confirmed by sequencing.

2.6. PhoP phosphorylation

Purified 6 × (His)PhoP (10 µg) was incubated in 20 μl of Tris–HCl 50 mM pH 7.4, NaCl 100 mM, MgCl2 100 mM with or without acetyl-P 20 mM at 37 °C for 30 min. After this incubation period, samples were mixed with protein loading buffer and loaded onto 8 % SDS-PAGE gels containing 10 µM Phos-tag reagent (Fujifilm Wako Chemicals) and 20 µM Cl2Mn. Gels were run at 100 V and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue solution.

2.7. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

Different DNA fragments spanning the putative promoter regions of selected genes were amplified by PCR (Supplementary file 1, Table S4; Supplementary file 2, Figure S7). Binding reactions were carried out in 15 μl of binding buffer (2.5 mM Tris–HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 25 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM EDTA, 0.25 mM dithiothreitol, 15 % glycerol) containing 1 μg of salmon sperm DNA, 50 ng of the target DNA and varying amounts of His-tagged PhoP (0–7.2 μM final concentration). Acetyl-phosphate 20 mM was added to check the effect of phosphorylation on PhoP DNA binding activity. After 30 min at 37 °C, protein-DNA complexes were resolved by electrophoresis in 6 % polyacrylamide gels in TAE buffer at 100 V and stained with RedSafe™ (iNtRON Biotechnology).

3. Results

3.1. Expression of the pstSCAB1B2-phoU genes in Lc. paracasei under high and low phosphate conditions

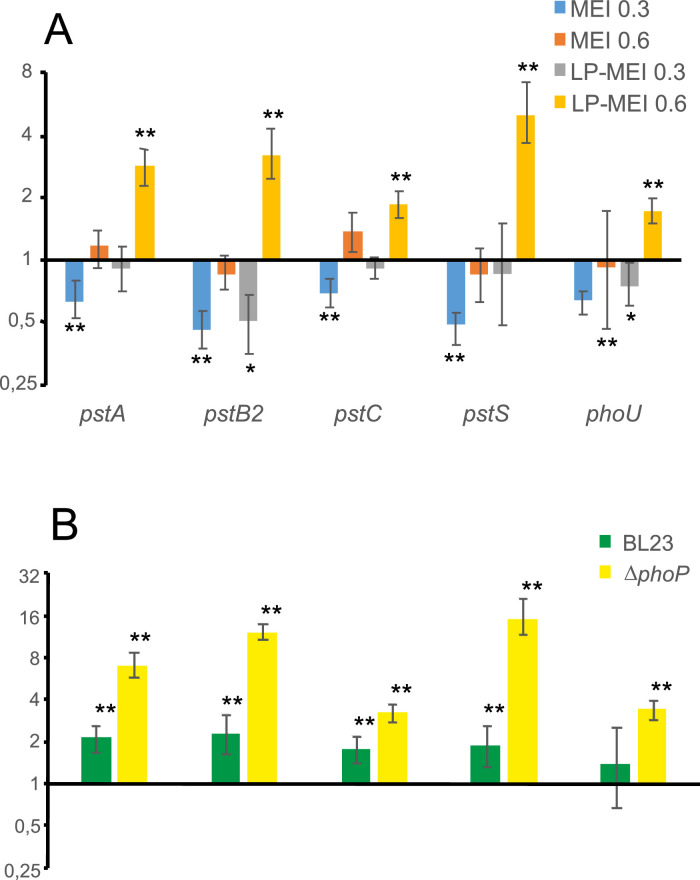

We hypothesized that the pst operon in Lc. paracasei is under control of the PhoPR system as described in other organisms. Therefore, to gain insight into the role of PhoPR, the relative abundance pst gene transcripts in the wild type and a deletion mutant lacking the response regulator PhoP (ΔphoP) were determined. For this purpose, samples obtained from cells grown to early or mid-exponential phase in either high- or low-Pi media (MEI and LP-MEI media, respectively; Fig. 1) were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Data obtained revealed a slight downregulation of pst transcripts, specially in MEI, at early exponential phase in ΔphoP compared to BL23 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, at mid exponential phase, pst genes were upregulated in LP-MEI, whereas no differences were observed in MEI. On the other hand, comparison of the expression in either MEI or LP-MEI of each strain showed a slight increase in expression of pst genes in the parental strain and a strong induction in the ΔphoP strain (Fig. 1B). These results suggested that PhoP regulates the expression of pst genes in response to the availability of phosphate and in a growth-phase-dependent manner.

Fig. 1.

Expression analysis of pst genes in wild-type Lc. paracasei and a ΔphoP strain. (A) Relative transcript levels of pst genes in Lc. paracasei BL23 compared to its derivative mutant ΔphoP in MEI or LP-MEI media at early (DO595 0.3) or mid exponential phase (DO595 0.6); (B) Expression of pst genes in Lc. paracasei BL23 or ΔphoP strains in MEI medium compared to LP-MEI at mid exponential phase (DO595 0.6). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

3.2. Transcriptome analysis of Lc. paracasei and its derived ΔphoP mutant

The transcript levels in Lc. paracasei BL23 and its derivative ΔphoP strain were estimated in cells grown to mid exponential phase in LP-MEI medium since a greater difference in pst gene expression between the two strains was observed in this condition. Three biological replicates were analyzed for each strain. Approximately 20 million mapped raw reads per sample were obtained (Supplementary file 2, Figure S1) with medians of reads per gene ranging from 1251 to 1562 (Supplementary file 1, Table S1). Analysis of the density of reads counts showed very similar distributions for each set of replicates, supporting the robustness of the obtained data (Supplementary file 2, Figure S2). Furthermore, a principal component analysis (PCA) showed a clear separation of the samples belonging to BL23 and PhoP strains, with the first component accounting for 94.55 % of the variance (Supplementary file 2, Figure S3).

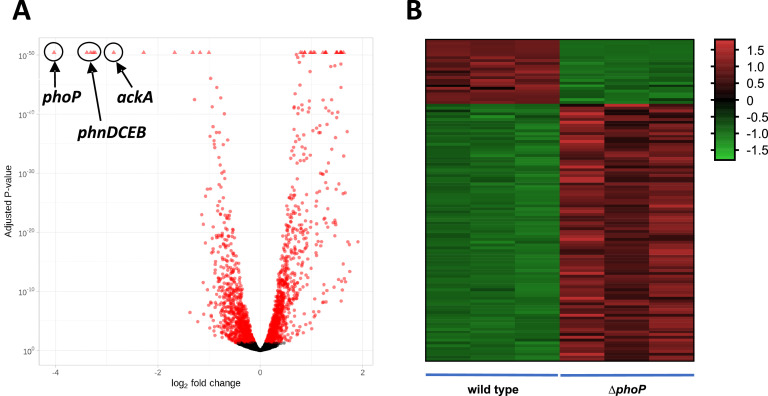

A remarkable number of genes showed significant differences under these conditions, indicating a pleiotropic effect of PhoP in gene expression (Fig. 2). Approximately 57.5 % of the annotated genes showed statistically significant changes in their transcription, including both upregulated (968) and dowregulated (869) genes when the ΔphoP strain was compared to the wild type (Supplementary file 3). However, although statistically significant, these changes were generally small so that only 92 upregulated and 22 downregulated genes reached fold changes greater than 2.

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional analysis of Lc. paracasei ΔphoP versus wild-type strains. (A) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes in red. The positions of the phnDCEB cluster, ackA and phoP genes are indicated. The open reading frame of the phoP gene was not completely deleted in strain ΔphoP, explaining the presence of reads mapping to it in RNAseq experiments; (B) Heat map clustering of differentially expressed genes with greater fold changes. Data from the three experimental replicates from each strain are represented.

An analysis of the gene functional categories affected by the phoP mutation revealed that while ribonucleotide metabolism, cell wall biogenesis, transport, and peptidase processes were upregulated, categories such as cell wall organization, morphogenesis, and peptide biosynthesis were downregulated (Fig. 3). Among the specific upregulated genes, those with higher expression in the phoP mutant were notably enriched in genes encoding phage proteins from prophages present in the BL23 genome (e.g., LCABL_09800 to LCABL_10,010 or LCABL_11,090 to LCABL_11,270). Additionally, gene clusters encoding oligopeptide transporters and peptidases (e.g., those from LCABL_22,420 to LCABL_22,460, LCABL_21,440 to LCABL_21,470, and LCABL_03060 to LCABL_03070) were also upregulated, exhibiting fold changes between 2.4 and 4 (Supplementary file 3). The most significantly downregulated genes in the absence of PhoP included a cluster (phnDCEB; LCABL_26,140 to LCABL_26,170) encoding a putative phosphonate transporter, which was downregulated by as much as to 10.6-fold. Additionally, ackA (acetate kinase) was downregulated 7.4-fold and LCABL_16,090, annotated as a haemolysin, was downregulated 5-fold (Supplementary file 3). Of note, LCABL_16,090 had been previously identified as strongly upregulated in BL23 cells subjected to bile stress (Alcántara and Zúñiga, 2012). Other downregulated genes comprised genes putatively involved in arginine synthesis (argG, LCABL_30,160, 2.5-fold; argH, LCABL_30,170, 3.3-fold) or a putative DNA polymerase IV involved in DNA repair (LCABL_08410).

Fig. 3.

Enrichment analysis of different gene functional categories upon phoP deletion in Lc. paracasei. Lolliplot of GSEAS analysis showing the degree of enrichment (up and down) as NES (normalized enrichment score) of different GO terms.

The transcriptome data corroborated the previous qPCR findings, showing that the pst genes exhibited only slight upregulation in the ΔphoP strain (pstS, 1.8-fold; pstC, 1.5-fold; pstA, 1.3-fold; pstB1, 1.3-fold; pstB2, 1.3-fold; phoU, 1.2-fold; Supplementary file 3). An orphan pstS paralog (LCABL_15,130), not grouped with the other genes coding for the components of the Pst ABC transporter, was downregulated by 2.2-fold.

3.3. Analysis of PhoP binding to promoter regions of genes differentially expressed in a phoP strain

A search for putative PhoP binding sites in the promoter regions of Lc. paracasei BL23 genes was carried out using a set of PHO boxes from B. subtilis and related species, since this organism is the closest related species with experimentally determined PHO boxes (Supplementary file 1, Table S2; Supplementary file 2, Figure S4). This search revealed several matches (Table 1) among genes detected as differentially expressed, including pstS (LCABL_10,500; 1.8-fold upregulated in the ΔphoP strain), the first gene of the pstSCAB1B2 cluster, as the candidate with the highest score, followed by glnA (LCABL_05060, encoding a putative Gln synthase) and poxL (LCABL_20,020, pyruvate oxidase). Gene glnA was detected as significantly downregulated (fold change 0.83) whereas poxL was upregulated (fold change 1.475) in the ΔphoP strain. A hit with low score were also found upstream of phnD, in which phoP elimination caused a 9.5-fold downregulation effect. However, no PHO boxes could be identified in the ackA gene or other genes/operons that also displayed relevant changes in transcription (from 2.5- to 5-fold). The identified pstS PHO boxes consisted of four repetitions of the consensus (T/A)T(T/G)ACA separated by 4–6 bp. These four boxes presented some deviations from this consensus in the glnA, poxL and phnD promoters and they were oriented in the opposite direction to transcription (nonsense strand) in this last gene (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hits found with GLAM2Scan using the motif derived from Bacillus PHO boxes (Supplementary file 2; Figure S7) in Lc. paracasei BL23.

| Locus tag | Gene | Sequence* | Strand** | Score | Fold change*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCABL_10,500 | pstS | tttacacaatctttacattcaatgacatgaacatttaca | +(44) | 18.9 | 1.752 |

| LCABL_05060 | glnA | tttagacaatctttccttttatttaaaatcat.gtaaca | +(90) | 15.4 | 0.830 |

| LCABL_15,710 | fruR | ttcagaaaaacatgtcatttgattatacgcgatgtttata | + | 8.74 | |

| LCABL_15,720 | obgE | ttcagaaaaacatgtcatttgattatacgcgatgtttata | – | 8.74 | |

| LCABL_20,020 | poxL | atcaccacgccataacatgcttggtaaacctttttcaca | -(197) | 7.09 | 1.475 |

| LCABL_30,470 | ttcaccaaatgcctaaaattgggttaaactgaatttaacc | + | 6.06 | ||

| LCABL_30,470 | ttcaccaaatgcctaaaattgggttaaactgaatttaacc | – | 6.06 | ||

| LCABL_13,260 | ttgacaaagctttaaccaacattcaaaaggatattaatt | + | 6.04 | 1.456 | |

| LCABL_11,830 | glmS | tttatcaaaaatttaaactttattttaaccgagttgtca | + | 5.68 | 1.148 |

| LCABL_22,160 | atcaaaaaaacagctgatttgctttaaacgaatttacca | – | 4.10 | 0.689 | |

| LCABL_10,310 | ymfH | atgacaaccgattatggttcgattgatacgcaatttgca | + | 4.05 | 1.113 |

| LCABL_17,120 | rexB | ttcacaaaacca.aattttttatttagtccctaatcata | + | 3.63 | |

| LCABL_29,240 | tctgaaacatcgttaccttcaaat.aaaccaatttcacc | – | 3.34 | ||

| LCABL_28,610 | kduI | ttttcaaaaagaacacaagccactaaaacaaatttttta | – | 3.02 | 0.816 |

| LCABL_26,140 | phnD | tttataatatctgaatcaataactttacaataattttaca | -(117) | 3.00 | 0.107 |

* Putative PHO boxes are underlined and in bold for DNA fragments that were tested by EMSA.

** The distance to the translational start site is shown in parenthesis for pstS, glnA, poxL and phnD genes.

*** Only statistically significant fold change values are indicated.

Subsequently, we selected fragments corresponding to the promoter regions of pstS, glnA, poxL, phnD and ackA and assessed their interaction with PhoP. For this purpose, this regulator was purified as a 6 × (His) tagged protein after overexpression in E. coli. In vitro PhoP phosphorylation assays using acetyl-phosphate as a phosphodonor were carried out, showing that the protein could form a phosphorylated and thermolabile derivative when incubated with acetyl-phosphate (Fig. 4A). This evidenced a phosphate transfer, most likely at the level of the phosphorylatable regulatory Asp-52 residue. In EMSA assays (Fig. 4B), PhoP bound to the promoter region of the pst cluster, upstream of pstS, and this binding was enhanced by PhoP phosphorylation mediated by acetyl-phosphate. PhoP∼P also displayed a similar interaction with the phnD promoter. Binding of PhoP∼P to the glnA promoter required about ten-fold more PhoP when compared to pstS or phnD, indicating a weaker interaction, whereas no binding was detected between PhoP or PhoP∼P and the poxL or ackA regions. A search for additional PhoP binding sites using a motif derived from the putative sites found in pstS, glnA and phnD did not detect any of the genes found in the first screening, excluding the three genes used to obtain the motif (Supplementary file 1, Table S3; Supplementary file 2, Figure S5). This result suggests that sequence similarity is not enough to reliably identify PhoP binding sites in Lc. paracasei BL23. Additional hits found with this second motif were not investigated in this study.

Fig. 4.

Phosphorylated PhoP binds to promoter regions of some PhoP-regulated genes. (A) In vitro phosphorylation of 6 × (His)PhoP by acetyl-phosphate (20 mM). Protein samples were incubated with acetyl-phosphate and resolved in Phos-tag polyacrylamide gels. Some samples were heated at 95 °C before loading, which dephosphorylates the thermolabile Asp∼P bond. Mw, molecular weight (NZYColour Molecular Weight Marker II); (B) EMSA assays of pstS, phnD, poxL, glnA and ackA promoter fragments with 6 × (His)PhoP. Samples were incubated with or without acetyl-phosphate before loading onto polyacrylamide gels that were run in TAE buffer. The numbers indicate the concentration of 6x(His)PhoP in µM. “C” indicates the position of the competitor DNA used in the assays (E. coli genomic DNA).

3.4. Characterization of candidate genes to account for the As(III) resistance phenotype

We decided to focus on the genes that showed the greatest variation as possible candidates to explain resistance to As(III). The phn genes identified by transcriptome analysis and found to be downregulated (log2 fold change −3.389 to −3.229) upon phoP mutation were arranged in an operon, phnDCEB, which likely encodes a complete ABC transporter. This transporter includes the substrate-binding protein PhnD, the ATPase subunit PhnC, and two permease components, PhnE and PhnB, putatively involved in the transport of phosphonates, which are esters of phosphorous acid with organic compounds. Gene ackA (LCABL_01600) encodes a putative acetate kinase, which catalyzes the reversible dephosphorylation of acetyl-phosphate to acetate and the transference of the phosphate group to ADP to synthesize ATP. Lc. paracasei BL23 harbors a second ackA gene (LCABL_23,490) which was not affected by inactivation of phoP.

To test the functionality of phn genes in the BL23 strain, we constructed an insertional mutant with an inactivated phnD gene. Gene ackA is possibly cotranscribed with gen cshA2, which encodes a putative recombination factor of the RarA superfamily. Although this gene was identified as downregulated in the PhoP strain, the difference between the two strains was minimal, with a log2 fold change of −0.129 compared to −2.863 for ackA. Notwithstanding, to avoid possible effects on cshA2 expression, a small fragment of the ackA gene was deleted, resulting in the loss of the reading frame and premature termination of translation. Inactivation of phnD did not result in apparent growth defects compared to the wild type in MEI medium and the strain was as sensitive to As(III) as the wild-type strain (Fig. 5). Remarkably, inactivation of ackA caused a high resistance level to As(III) as observed in the PhoP mutant strain (Fig. 5). This result indicated that the resistance to As(III) in the PhoP strain is due to low expression of AckA.

Fig. 5.

Growth of Lc. paracasei BL23 and derivative mutants in MEI medium supplemented with different amounts of AsIII. The names of the corresponding strains are indicated in each graph.

4. Discussion

A characterization of Lp. plantarum and Lc. paracasei mutants defective in pst genes and its putative regulator TCS PhoPR revealed that inactivation in Lc. paracasei of PhoP, the transcriptional regulator partner of the TCS led to increased resistance to arsenite As(III) (Corrales et al., 2024), although the mechanism remained undetermined. A previous study had shown that inactivation of PhoP led to slow growth and a differential response to different stress conditions (Alcántara et al., 2011), indicating that this mutation has a pleiotropic effect. These antecedents led us to investigate the transcriptomic changes associated with the inactivation of PhoP in order to gain insight into the mechanism of resistance to As(III).

Our results led us to identify the diminished expression of the ackA gene as responsible of the As(III) resistance phenotype. This result is perplexing as acetate kinase activity, which converts acetyl-phosphate to acetate, does not involve any obvious metabolite targeted by As(III). However, coenzyme A (CoA), which possess a reactive sulfhydryl group, is a key intermediary in most pathways leading to the synthesis of acetyl-P (Fig. 6). Poor expression or lack of AckA may lead to accumulation of acetyl-P which in turn may affect the levels of CoA and acetyl-CoA via substrate inhibition of the phosphotransacetylase Pta. In Staphylococcus aureus, inactivation of either ackA or pta leads to a massive increase of acetyl-CoA levels (Sadykov et al., 2013). Similar results have been reported for Bacillus anthracis (Won et al., 2021). Although not measured, accumulation of acetyl-CoA possibly results in decreased CoA intracellular levels. Due to the affinity of As(III) for thiol groups, it is possible that it may react with CoA. Unfortunately, we have not found any report on this reaction or its toxic effects. It must be also taken into account that the thiol group of CoA is less reactive than those found in other low molecular weight thiol compounds such as cysteine or glutathione (Gout, 2019). Other possibilities should also be considered. Acetyl-P plays a significant role as a signalling molecule in many bacteria as a phosphodonor, for instance, to TCS response regulators (Wolfe, 2010), or as a protein acetylating agent (Lammers, 2021). An increase in acetyl-P levels may therefore affect a wide range of metabolic or signalling pathways.

Fig. 6.

Pyruvate catabolic pathways leading to acetyl-P present in Lc. paracasei BL23. AckA, acetate kinase; Pdh, pyruvate dehydrogenase; Pfl, pyruvate:formiate lyase; Pox, pyruvate oxidase; Pta, phosphotransacetylase.

The mechanism of regulation of PhoP on ackA expression also raises a number of questions. EMSA assays did not detect binding of PhoP to the cshA2 ackA intergenic region. The inspection of the transcriptomic data from the ackA gene showed that the decrease in RNAseq reads in the ΔphoP strain did not expand the entire ackA open reading frame and it was only identifiable starting around 100 bp from the ackA translational start site. This region contained a 23-bp palindromic sequence with the inverted repeat sequence TGCCAGCTGA (Fig. 7). This result strongly suggests that regulation of ackA by PhoP is mediated by another factor that recognizes this hairpin structure and blocks elongation of transcription. A search for similar structures indicates that this regulatory mechanism is specific of Lc. paracasei strains since the hairpin structure is absent in ackA genes of closely related species such as Lc. casei, Lc. rhamnosus or Lc. zeae (Supplementary file 2; Supplementary figure S6).

Fig. 7.

Mapping of reads from the transcriptomic analysis in the ackA gene region. The reads of RNAseq experiments along the ackA and surrounding genes are shown. Blue lines indicate reads in the 5′ to 3′ orientation; red lines represent reads in the opposite direction. A transcriptional terminator located between ackA and pphA genes is displayed, together with a 10 bp inverted repeated sequence located in the 5′ region of ackA, both represented by hairpins. The numbers in the ackA displayed sequence are nucleotide positions with respect to the ackA translational start point.

This study has also allowed us gaining insight into the Pho regulon of Lc. paracasei. Phosphate transport and metabolism in the Lactobacillaceae family has not been extensively studied. Previous research identified pst genes and the TCS phoPR in different species of this group (Zúñiga et al., 2011) but, how these genes coordinate the bacterial response to Pi availability remains unclear. The small differences in pst genes transcription under high and low Pi conditions and their upregulation upon phoP mutation in Lc. paracasei apparently contradicts the proposed model of regulation in E. coli or other model microorganisms. In this model, PhoP activates genes involved in Pi acquisition and metabolism, including the pstSCAB cluster, under Pi-limiting conditions (Gardner and McCleary, 2019). In Lc. paracasei BL23, on the contrary, results obtained suggest that PhoP inhibits the expression of the pst operon. PhoP generally acts as a transcriptional activator, but in many bacteria, some set of genes are repressed by PhoP in order to optimize bacterial survival and adaptation under Pi-limited conditions. These included genes involved in a wide range of functions such as motility, virulence, stress responses and secondary metabolism (Chekabab et al., 2014; Martín et al., 2017). We showed here that some specific functions that were repressed by PhoP in Lc. paracasei BL23 (i.e. upregulated in the ΔphoP strain) were related to specific functions that might need to be tuned down under low Pi conditions (e.g. peptide and amino acids metabolism). In other microorganisms the PhoPR signalling is integrated with other regulatory processes such as sporulation, respiration, stress response or virulence (Hulett, 1996; Lamarche et al., 2008). Transcription of the pst genes in the BL23 strain is upregulated by 3 to 4-fold in the presence of bile (Alcántara and Zúñiga, 2012) and expression of pstS in Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus was induced by basic pH (Wallenius et al., 2011), suggesting that expression of these genes respond to other stress signals beyond phosphate scarcity. Our results indicate that the absence of PhoP in Lc. paracasei leads to significant pleiotropic effects, as evidenced by substantial transcriptome changes. However, most of the direct targets of PhoP control remain to be identified, and how PhoP modulates or integrates its signal in other processes in the Lactobacillaceae requires further investigation.

In B. subtilis the Pho regulon encompasses >30 genes (Allenby et al., 2005), whereas around 10 genes/operons are directly regulated by PhoP in E. coli (Fitzgerald et al., 2023; Gardner and McCleary, 2019). The limited success of the search for PHO boxes using conserved motifs suggests that PhoP may recognize PHO boxes with a high degree of variation. Furthermore, although four PHO boxes are generally found in Pho-regulated promoters, in some instances an even number from two to eight have been shown to be functional (Allenby et al., 2005). EMSA assays confirmed binding of PhoP∼P to the pstS, glnA and phnD promoter regions. Furthermore, the differential binding affinity of PhoP∼P to the three promoters suggest a hierarchical binding to different promoters as described for other organisms (Martín et al., 2012; Santos-Beneit, 2015). These findings identify for the first time three genes/operons belonging to the Pho regulon in a Lactobacillaceae species.

The binding of PhoP∼P to the glnA promoter suggests a possible regulatory link between phosphate and nitrogen metabolism in Lc. paracasei. Glutamine synthetase GlnA activity plays a major role in the regulation of nitrogen levels as a major way of ammonium assimilation and by modulating the DNA binding activity of nitrogen regulators such as GlnR in S. pneumoniae (Kloosterman et al., 2006) or TnrA in B. subtilis (Wray et al., 2001). In S. coelicolor, PhoP controls the expression of a number of nitrogen metabolism genes including glnA (Martín et al., 2011). Lc. paracasei BL23 encode two putative glutamine synthetases (LCABL_05060 and LCABL_18,680). Expression of both genes is affected by PhoP inactivation. LCABL_05060 is downregulated in the PhoP mutant whereas LCABL_18,680 is upregulated (Supplementary file 3). Unfortunately, none of them has been characterized. On the other hand, a key regulatory system of nitrogen metabolism in Lc. paracasei is the TCS system PrcRK which affect the expression of numerous peptide and amino-acid metabolic genes (Alcántara et al., 2016), but GlnA encoding genes were not detected among them.

In contrast to the weak effect on the expression of the pst operon, a remarkable downregulation of the phn cluster in ΔphoP strain was detected. In E. coli, the phnCDEFGHIJKLMNOP operon (Metcalf and Wanner, 1991) codes for an ABC transporter (phnCDE), a transcriptional regulator (phnF) and genes encoding enzymes involved in the transport and catabolism of phosphonates, phosphite ([HPO₃]²⁻) and Pi esters, encoded by phnGHIJKLMNOP. The C-P bond present in phosphonates is broken by an enzyme complex with C-P lyase activity (PhnGHIJKLM). In E. coli K-12, the phn cluster is cryptic due to an 8-bp insertion at the level of the phnE gene. However, in strains carrying ΔpitA, coding for a low affinity metal-Pi/H+ symporter permease (Harris et al., 2001), and Δpst deletions, revertants in phnE which are able to use Pi as a P source can be obtained (Stasi et al., 2019). In Mycolicibacterium smegmatis, both Pst and Phn systems coexist and they function as high affinity (Km for both in the μM range) Pi transporters (Gebhard et al., 2006) and its transcription is controlled by Pi availability through the PhnF regulator (Gebhard et al., 2014). The absence of phosphonate catabolic genes in many Streptomyces phn operons also suggest that they may function as surrogates for Pi transporters (Martín and Liras, 2021). The lack of catabolic genes (e.g. C-P lyases) in the Lc. paracasei genome questions its function in phosphonate catabolism. Thus, the participation of phn genes in Pi transport in the BL23 strain cannot be excluded. The occurrence of several systems for the incorporation of Pi has been suggested for Lc. paracasei BL23, where similar to a phnD mutant, deleting the pstC, had no strong effect on growth in medium containing low Pi (Corrales et al., 2024). The contributions of the Pst and Phn transporters to Pi uptake in Lc. paracasei remain to be established. An inspection of Lactobacillaceae genomes showed that phnDCEB clusters with similar structures are present in many species within this family. However, with some exceptions, this cluster was not adjacent to or did not form operon structures with other genes involved in phosphonate catabolism. Notable exceptions included some species of Agrilactobacillus, Companilactobacillus, Lentilactobacillus, Schleiferlactobacillus and Lactiplantibacillus, where phnDCEB formed operon structures with phnX and phnW genes, coding for putative phosphonoacetaldehyde hydrolases and 2-aminoethylphosphonate-pyruvate transaminases, respectively.

In summary, our results have identified AckA as the protein responsible for the As(III) resistance phenotype observed in a ΔphoP mutant strain. However, the mechanism of action explaining this effect remains to be determined. Furthermore, the Pho regulon of Lc. paracasei has been studied for the first time and three gene/operons belonging to this regulon have been identified. This study opens new paths to characterize As(III) toxicity and the regulation of phosphate metabolism as well as its links with other regulatory pathways in this organism.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Daniela Corrales: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Cristina Alcántara: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis. Dinoraz Vélez: Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. Vicenta Devesa: Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Vicente Monedero: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Manuel Zúñiga: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades/Agencia Estatal de Investigación (MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) from Spain, grant number RTI2018–098071-B-I00, and it was co-funded by the European Commission through the European Regional Development Fund (Multiregional operative program for Spain 2014–2020). The Accreditation as Center of Excellence Severo Ochoa CEX2021–001189-S funded by MCIU/AEI is also fully acknowledged.

D. Corrales is grateful for her doctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación of Colombia (Convocatoria 906 de 2021). We thank J.M. Peña Carrera for his help in the construction of the ackA mutant strain.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2025.100357.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

The RNAseq dataset used in this work has been deposited at NCBI and is available under Bioproject PRJNA1141229 (https://w.w.w.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1141229). Other data generated in this study will be made available on request.

References

- Alcántara C., Bäuerl C., Revilla-Guarinos A., Pérez-Martínez G., Monedero V., Zúñiga M. Peptide and amino acid metabolism is controlled by an OmpR-family response regulator in Lactobacillus casei. Mol. Microbiol. 2016;100:25–41. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara C., Revilla-Guarinos A., Zúñiga M. Influence of two-component signal transduction systems of Lactobacillus casei BL23 on tolerance to stress conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:1516–1519. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02176-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara C., Zúñiga M. Proteomic and transcriptomic analysis of the response to bile stress of Lactobacillus casei BL23. Microbiology. 2012;158:1206–1218. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.055657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allenby N.E.E., O'Connor N., Prágai Z., Ward A.C., Wipat A., Harwood C.R. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of the phosphate starvation stimulon of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:8063–8080. doi: 10.1128/jb.187.23.8063-8080.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Pyl P.T., Huber W. HTSeq—A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2014;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres J., Bertin P.N. The microbial genomics of arsenic. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016;40:299–322. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro C., Martínez-Castro M. Regulation of the phosphate metabolism in Streptomyces genus: impact on the secondary metabolites. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019;103:1643–1658. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-09600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco A.G., Sola M., Gomis-Rüth F.X., Coll M. Tandem DNA recognition by PhoB, a two-component signal transduction transcriptional activator. Structure. 2002;10:701–713. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00761-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella E., Devine S.K., Hubner S., Salzberg L.I., Gale R.T., Brown E.D., Link H., Sauer U., Codée J.D., Noone D., Devine K.M. PhoR autokinase activity is controlled by an intermediate in wall teichoic acid metabolism that is sensed by the intracellular PAS domain during the PhoPR-mediated phosphate limitation response of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;94:1242–1259. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekabab S.M., Harel J., Dozois C.M. Interplay between genetic regulation of phosphate homeostasis and bacterial virulence. Virulence. 2014;5:786–793. doi: 10.4161/viru.29307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrales D., Alcántara C., Clemente M.J., Vélez D., Devesa V., Monedero V., Zúñiga M. Phosphate uptake and its relation to arsenic toxicity in lactobacilli. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024;25:5017. doi: 10.3390/ijms25095017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davray D., Deo D., Kulkarni R. Plasmids encode niche-specific traits in Lactobacillaceae. Microb. Genom. 2021;7 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2012;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder S., Liu W., Hulett F.M. Mutational analysis of the phoD promoter in Bacillus subtilis: implications for PhoP binding and promoter activation of pho regulon promoters. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:2017–2025. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2017-2025.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, D.M., Stringer, A.M., Smith, C., Lapierre, P., Wade, J.T., 2023. Genome-wide mapping of the Escherichia coli PhoB regulon reveals many transcriptionally inert, intragenic binding sites. MBio. 14, e02535–02522. doi:10.1128/mbio.02535-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Frith M.C., Saunders N.F.W., Kobe B., Bailey T.L. Discovering sequence motifs with arbitrary insertions and deletions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner S.G., Johns K.D., Tanner R., McCleary W.R. The PhoU protein from Escherichia coli interacts with PhoR, PstB, and metals to form a phosphate-signaling complex at the membrane. J. Bacteriol. 2014;196:1741–1752. doi: 10.1128/jb.00029-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner S.G., McCleary W.R. Control of the phoBR regulon in Escherichia coli. EcoSal Plus. 2019;8 doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0006-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhard S., Busby J.N., Fritz G., Moreland N.J., Cook G.M., Lott J.S., Baker E.N., Money V.A. Crystal structure of PhnF, a GntR-family transcriptional regulator of phosphate transport in mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 2014;196:3472–3481. doi: 10.1128/jb.01965-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhard S., Tran S.L., Cook G.M. The Phn system of mycobacterium smegmatis: a second high-affinity ABC-transporter for phosphate. Microbiology. 2006;152:3453–3465. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gout I. Coenzyme A: a protective thiol in bacterial antioxidant defence. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019;47:469–476. doi: 10.1042/bst20180415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold F.M., Spitz E. Accumulation of arsenate, phosphate, and aspartate by Streptococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 1975;122:266–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.1.266-277.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R.M., Webb D.C., Howitt S.M., Cox G.B. Characterization of PitA and PitB from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:5008–5014. doi: 10.1128/jb.183.17.5008-5014.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulett F.M. The signal-transduction network for pho regulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;19:933–939. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.421953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleerebezem M., Boekhorst J., van Kranenburg R., Molenaar D., Kuipers O.P., Leer R., Tarchini R., Peters S.A., Sandbrink H.M., Fiers M.W.E.J., Stiekema W., Lankhorst R.M.K., Bron P.A., Hoffer S.M., Groot M.N.N., Kerkhoven R., de Vries M., Ursing B., de Vos W.M., Siezen R.J. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1990–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337704100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman T.G., Hendriksen W.T., Bijlsma J.J.E., Bootsma H.J., van Hijum S.A.F.T., Kok J., Hermans P.W.M., Kuipers O.P. Regulation of glutamine and glutamate metabolism by GlnR and GlnA in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:25097–25109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranenburg R.v., Golic N., Bongers R., Leer R.J., Vos W.M.d., Siezen R.J., Kleerebezem M. Functional analysis of three plasmids from Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:1223–1230. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1223-1230.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche M.G., Wanner B.L., Crépin S., Harel J. The phosphate regulon and bacterial virulence: a regulatory network connecting phosphate homeostasis and pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008;32:461–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers M. Post-translational lysine ac(et)ylation in bacteria: a biochemical, structural, and synthetic biological perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.757179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landete J.M., García-Haro L., Blasco A., Manzanares P., Berbegal C., Monedero V., Zúñiga M. Requirement of the Lactobacillus casei MaeKR two-component system for l-malic acid utilization via a malic enzyme pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:84–95. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02145-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leloup L., Ehrlich S.D., Zagorec M., Morel-Deville F. Single-crossover integration in the Lactobacillus sake chromosome and insertional inactivation of the ptsI and lacL genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:2117–2123. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2117-2123.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J.F., Liras P. Molecular mechanisms of phosphate sensing, transport and signalling in Streptomyces and related actinobacteria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:1129. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J.F., Rodríguez-García A., Liras P. The master regulator PhoP coordinates phosphate and nitrogen metabolism, respiration, cell differentiation and antibiotic biosynthesis: comparison in Streptomyces coelicolor and Streptomyces avermitilis. J. Antibiot. 2017;70:534–541. doi: 10.1038/ja.2017.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J.F., Santos-Beneit F., Rodríguez-García A., Sola-Landa A., Smith M.C.M., Ellingsen T.E., Nieselt K., Burroughs N.J., Wellington E.M.H. Transcriptomic studies of phosphate control of primary and secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;95:61–75. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J.F., Sola-Landa A., Santos-Beneit F., Fernández-Martínez L.T., Prieto C., Rodríguez-García A. Cross-talk of global nutritional regulators in the control of primary and secondary metabolism in streptomyces. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011;4:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazé A., Boël G., Zúñiga M., Bourand A., Loux V., Yebra M.J., Monedero V., Correia K., Jacques N., Beaufils S., Poncet S., Joyet P., Milohanic E., Casarégola S., Auffray Y., Pérez-Martínez G., Gibrat J.-F., Zagorec M., Francke C., Hartke A., Deutscher J. Complete genome sequence of the probiotic Lactobacillus casei strain BL23. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:2647–2648. doi: 10.1128/jb.00076-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf W.W., Wanner B.L. Involvement of the Escherichia coli phn (psiD) gene cluster in assimilation of phosphorus in the form of phosphonates, phosphite, pi esters, and pi. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:587–600. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.587-600.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak R., Cauwels A., Charpentier E., Tuomanen E. Identification of a Streptococcus pneumoniae gene locus encoding proteins of an ABC phosphate transporter and a two-component regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:1126–1133. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1126-1133.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonechnikov K., Conesa A., García-Alcalde F. Qualimap 2: advanced multi-sample quality control for high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;32:292–294. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela C.J., Mills J., Robb C.W., Wilson C.J., Watson D.A., Niesel D.W. Streptococcus pneumoniae PstS production is phosphate responsive and enhanced during growth in the murine peritoneal cavity. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:7565–7571. doi: 10.1128/iai.69.12.7565-7571.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M.W., Horgan G.W., Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST©) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. -e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poolman B., Nijssen R.M., Konings W.N. Dependence of Streptococcus lactis phosphate transport on internal phosphate concentration and internal pH. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:5373–5378. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5373-5378.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posno M., Leer R.J., Luijk N.v., Giezen M.J.F.v., Heuvelmans P.T.H.M., Lokman B.C., Pouwels P.H. Incompatibility of Lactobacillus vectors with replicons derived from small cryptic Lactobacillus plasmids and segregational instability of the introduced vectors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991;57:1822–1828. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.6.1822-1828.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y., Kobayashi Y., Hulett F.M. The pst operon of Bacillus subtilis has a phosphate-regulated promoter and is involved in phosphate transport but not in regulation of the Pho regulon. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:2534–2539. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2534-2539.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadykov M.R., Thomas V.C., Marshall D.D., Wenstrom C.J., Moormeier D.E., Widhelm T.J., Nuxoll A.S., Powers R., Bayles K.W. Inactivation of the pta-AckA pathway causes cell death in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:3035–3044. doi: 10.1128/jb.00042-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzberg L.I., Botella E., Hokamp K., Antelmann H., Maaß S., Becher D., Noone D., Devine K.M. Genome-wide analysis of phosphorylated PhoP binding to chromosomal DNA reveals several novel features of the PhoPR-mediated phosphate limitation response in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2015;197:1492–1506. doi: 10.1128/jb.02570-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Beneit F. The pho regulon: a huge regulatory network in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S., Li X.-F., Cullen W.R., Weinfeld M., Le X.C. Arsenic binding to proteins. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:7769–7792. doi: 10.1021/cr300015c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sola-Landa A., Rodríguez-García A., Franco-Domínguez E., Martín J.F. Binding of PhoP to promoters of phosphate-regulated genes in streptomyces coelicolor: identification of PHO boxes. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:1373–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasi R., Neves H.I., Spira B. Phosphate uptake by the phosphonate transport system PhnCDE. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:79. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1445-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S.L., Golub T.R., Lander E.S., Mesirov J.P. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallenius J., Uuksulainen T., Salonen K., Rautio J., Eerikäinen T. The effect of temperature and pH gradients on Lactobacillus rhamnosus gene expression of stress-related genes. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2011;34:1169–1176. doi: 10.1007/s00449-011-0568-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner B.L., Latterell P. Mutants affected in alkaline phosphatase expression: evidence for multiple positive regulators of the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1980;96:353–366. doi: 10.1093/genetics/96.2.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe A.J. Physiologically relevant small phosphodonors link metabolism to signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010;13:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won H.I., Watson S.M., Ahn J.-S., Endres J.L., Bayles K.W., Sadykov M.R. Inactivation of the pta-AckA pathway impairs fitness of Bacillus anthracis during overflow metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 2021;203 doi: 10.1128/jb.00660-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray L.V., Zalieckas J.M., Fisher S.H. Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase controls gene expression through a protein-protein interaction with transcription factor TnrA. Cell. 2001;107:427–435. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00572-4. Jr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y., Sugiyama S., Oyamada T., Yokoyama K., Makino K. Novel members of the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli O157:H7 identified using a whole-genome shotgun approach. Gene. 2012;502:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga M., Gómez-Escoín C.L., González-Candelas F. Evolutionary history of the OmpR/IIIA family of signal transduction two component systems in Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011;11:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNAseq dataset used in this work has been deposited at NCBI and is available under Bioproject PRJNA1141229 (https://w.w.w.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1141229). Other data generated in this study will be made available on request.