Abstract

Background and objectives

Silver (Ag) and Copper (Cu) Nanoparticles (NP) are a potential substitute for disinfection during endodontic therapy because of their antibacterial action against an array of pathogens, including resistant strains. This study aimed to assess the antibiofilm efficiency of calcium hydroxide modified with Ag and Cu NP suspension against E. faecalis, using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and colony forming units (CFU) analysis.

Methods

Dentine blocks were inoculated with Enterococcus faecalis for one week and 1 week-old biofilm of E. feacalis were randomly divided into 4 groups, control, calcium hydroxide, calcium hydroxide +2 % Cu NP and calcium hydroxide +2 % Ag NP. Following the incubation of the specimens with the medicament for 24 h at 37C, CLSM was used to evaluate the reduction in biovolume of the biofilm and the CFU was determined to assess the antimicrobial action of the NP-modified calcium hydroxide.

Results

CLSM images revealed a significant reduction in the thickness of biofilm in both Ag and Cu groups compared to calcium hydroxide alone. The CFU results showed that group 4 and group 3 showed significantly less CFU followed by group 2 and group 1 (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Adding Cu and Ag NP to calcium hydroxide intracanal medication significantly increases its antibacterial activity against E. faecalis.

Keywords: Copper nanoparticle, Silver nanoparticle, Calcium hydroxide, Endodontic treatment

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Endodontic infection is predominantly associated with biofilm which comprises microbes, proteins, and polysaccharides. This produces a protective layer that shields bacteria from the host immune response and drugs.1 One of the main reasons for failure in endodontic therapy is persistent apical periodontitis caused by biofilm. Enteroccous. Faecalis is the most prevalent bacteria in persistent periradicular lesions.2 This bacterium can withstand high pH, salt concentration, and nutritional deprivation. Its capacity to infiltrate dentinal tubules and its development of antibiotic resistance have led to its removal from root canals exceedingly challenging.3

The efficient removal of bacteria from the pulp cavity is critical to the outcome of endodontic therapy. Therefore, in order to eradicate any remaining bacteria and get a positive result after root canal therapy, the use of antibacterial medication, and intracanal irrigants is essential.3

Nevertheless, antibiotics usage have an array of concerns, especially when it comes to secondary root infections, when a versatile antimicrobial treatment that can kill a variety of microbes is needed. The efficacy of irrigants and intracanal medications is crucial. Nonetheless, these treatments carry the risk of toxicity and allergic responses, which can result in tissue damage.

There is only a limited amount that mechanical instruments can do to lower the microbes. Thirty-five percent of the apical region of the root canal system remains untreated by endodontic files. Infected conditions necessitate the application of intracanal medication. Calcium hydroxide has been established as the standard intracanal medication, which is administered into the canal between treatment sessions. As long as a high pH is maintained, calcium hydroxide in the root canal system has antimicrobial capabilities.4 Less viscous calcium hydroxide preparations have been more successful than viscous preparations in eradicating E. faecalis.5 It has been demonstrated that E. faecalis cells in the exponential development phase are most susceptible to calcium hydroxide and are destroyed within a duration of three to 10 min.6

Conversely, several studies have demonstrated that calcium hydroxide is ineffective in the eradication of microorganisms. When employed against S. sanguis, two investigations found that calcium hydroxide as a paste had little antibacterial effect.7 Additionally, it was demonstrated that a calcium hydroxide paste was unable to eradicate E. faecalis in dentinal tubules.8 E. faecalis was found to be viable in dentinal tubules even after quite long periods of treatment with a calcium hydroxide/saline mixture, according to Safavi et al.9

Previous studies has shown that the removal of E. faecalis DNA was more successful with a 2 % chlorhexidine treatment followed by canal filling than with calcium hydroxide alone.10,11 Calcium hydroxide was less effective than 2 % Chlorhexidine gel in eliminating E. faecalis.12 Additionally, it is more challenging to eradicate E. faecalis completely from root canals, especially after the formation of a biofilm. Moreover, the microorganisms often become resistant to the root canal irrigants. Nanotechnology enables the synthesis of effective antibacterial nanoparticles, which have emerged as a cutting-edge treatment option for dental infections. Due to their superior properties, nanoparticles—whether produced through chemical or biological methods—are increasingly being used in the pharmaceutical and biomedical industries. The addition of nanoparticles to biomaterials used in endodontics has demonstrated encouraging outcomes in terms of enhancing antibacterial capabilities. The use of medication made from nanoparticles has seen a significant increase in popularity as a way to overcome the drawbacks of currently available intracranial medicaments.13 Improper management of these medications, when extruded beyond apex can result in severe inflammation and consequent tissue loss.

The unique antibacterial actions displayed by nanoparticles disrupt metal ion equilibrium that impedes the growth of microorganisms.13 Reactive oxygen species are generated when nanoparticles attach to a microorganism's cell membrane, destroying the organism and causing oxidative stress. The cell membrane is further disrupted by this activity.14 Moreover, carbonyl, a protein-bound catalyzing agent that is formed by nanoparticles, initiates oxidative reactions in the amino acid chain that result in substantial degradation of protein, catalytic activity disruption, and inactivation of enzyme.15

NP is utilized as a potent antibacterial agent due to its efficacy against a diverse array of organisms. There are many distinct types of nanoparticles that can be categorized as follows: metallic (gold, silver, copper), inorganic (titanium, zinc oxide), polymeric (chitosan), and functionalized with medication or photosensitizers. Ag ions combine electrostatically with the bacteria, changing their permeability and ultimately eliminating the microorganism. Because of its antibacterial activity against different species, Ag NP is among the most investigated,16,17 Ag NP has been tested in endodontics as irrigation solutions, root canal medications, canal sealers, and endodontic retro fill materials.

Conversely, Cu NP demonstrates a broad range of antibacterial action against various microorganism species.18 In addition to being less expensive than silver, Cu has less stability in physical and chemical properties.19 Research indicates that copper nanoparticles (Cu NPs) can combat oral infections. Their antibacterial activity has been demonstrated against oral pathogens, such as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans.,20 as well as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli21 and candida albicans.22

The limited ability of existing drugs to effectively eradicate bacteria from the deeper layers of dentinal tubules and the rising frequency of unexpected cytotoxic effects make it imperative to explore innovative treatments that employ nanoparticles. Numerous nanoparticles have been shown in the literature to have antibacterial and therapeutic qualities, suggesting that they may be used as intracanal medications.16,17,18Therefore, the aim of this present study was to assess the antibiofilm efficiency of Cu and Ag NP incorporated calcium hydroxide as an intracanal medicament in an experimentally created endodontic biofilm model consisting of E. Faecalis.

2. Methodology

2.1. Sample size and grouping

Study included 40 teeth samples in total (Institutional ethical committee - Ref:SRMU/M&HS/SRMDC/2023/S/011). Sample size was determined using GPower software (latest ver. 3.1.9.7; Heinrich-Heine-University Dusseldorf, Germany).23 Samples were randomly divided into 4 groups group 1; control, group 2; calcium hydroxide, group 3; calcium hydroxide +2 % Cu NP and group 4; calcium hydroxide +2 % Ag NP.

2.2. Preparation of test specimens

Using a diamond disk the teeth samples were decoronated and the apex was removed. Sectioning was done at the midsagittal plane to split teeth in the longitudinal direction and dentin slabs measuring 4 × 4 × 1 mm were prepared. To ensure there was no bacterial contamination, dentin slabs were autoclaved, and kept in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth for 24 h at 37 C.2

2.3. Microbial inoculation

Test tubes bearing the sample and broth were opened inside a laminar flow and automated micropipettes were used to transfer 30 μL of 1 × 108 mL−1 E. faecalis suspension into the tubes. It was then incubated at 37 C for 1 week. Every third day, a new BHI broth was added to verify the bacterial viability and eliminate dead cells. The samples were then carefully taken out of the tubes and cleaned with sterile PBS solutions. The samples were then allocated into the experimental groups.2

2.4. Assessment of antibiofilm activity of test materials

Ag and Cu NP suspension was made with a concentration of 20 mg/ml by adding the NPs to sterile saline solution. The calcium hydroxide modified with 2 % silver and Cu NPs was prepared by mixing 990 mg of calcium hydroxide powder and 1 ml of freshly prepared NP.24 Two hundred microliter of freshly mixed calcium hydroxide was coated on dentinal blocks allowed into four groups Group 1: Negative control, Group 2: CaOH + sterile saline, Group 3: CaOH modified with 2 % Cu NP, Group 4: CaOH modified with 2 % Ag NP. The samples were subsequently incubated for 24 h at 37 C. Subsequently, the biofilm containing dentine blocks was carefully cleaned with sterile deionized water. The samples were used to obtain the suspension for CFU and later, stained with rhodamine dye to examine under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Stellaris 5WLL Confocal scanning system, Leica, Germany).

2.5. Assessment of antibiofilm efficacy of Ag NP and Cu NP by CFU

After rinsing the specimens with deionized water to remove the calcium hydroxide coatings, the dentinal block was inserted in a micro test tube containing 1 ml of physiological saline solutions and vortexed for 1 min. The microbial suspension was cultured for 24 h at 37 °C in a 0.1 mL aliquot on a BHI agar plate. Afterwards, the amount of E. Faecalis colony-forming units on BHI agar plates was counted and noted. The findings of the statistical study were tabulated.

2.6. Assessment of antibiofilm efficacy of Ag NP and Cu NP by CLSM

CLSM was used to quantify the biofilms before and after the applications of calcium hydroxide incorporated with NP. The dentine specimens with biofilm were stained with rhodamine dye. The samples were prepared for the CLSM examination after being left in dark conditions for 20 min to enable the dyes to reach the bacteria. Following this, samples were rinsed for 1 min with sterile saline solution25 Stellaris 5WLL confocal scanning system was used. The optical sections were recorded and 3D construction was done.

2.7. Statistical analysis

SPSS software was used to compute statistics with version 24 (SPSS Inc., USA). Using descriptive analysis mean and SD were tabulated. Tukey's test was applied after a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the outcomes between the groups. Kruskal-Wallis test, was used to compare the mean CFU counts across the four groups. A significance level of p < 0.05 with a confidence interval of 95 % was applied to determine statistically meaningful differences. Dunn's post hoc test was performed to identify specific pairwise group differences. Effect size measurement was done by Cohen's d to quantify the magnitude of the differences.

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial colonies on BHI agar plate

The mean CFUs count of E. faecalis was compared between the four groups using the Kruskal Wallis Test and Dunn's post hoc test. A significance value of P < 0.05 was applied. The test results demonstrate that the mean CFUs count for Group 1 was 0.631 ± 0.047, Group 2 was 0.388 ± 0.071, Group 3 was 0.250 ± 0.021 and Group 4 was 0.195 ± 0.011. At p < 0.001, there was a statistically significant difference in the mean CFUs count of E. faecalis across the four groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of mean CFUs of E. Faecalis (x 104) b/w 4 groups using Kruskal Wallis Test.

| Groups | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 10 | 0.631 | 0.047 | 0.60 | 0.70 | <0.001∗ |

| Group 2 | 10 | 0.388 | 0.071 | 0.30 | 0.50 | |

| Group 3 | 10 | 0.250 | 0.021 | 0.22 | 0.30 | |

| Group 4 | 10 | 0.195 | 0.011 | 0.18 | 0.21 |

Note: Group 1: Control; Group 2: Calcium Hydroxide; Group 3: Cu + Calcium Hydroxide; Group 4: Ag + Calcium Hydroxide.

∗Statistically Significant.

Calcium hydroxide +2 % Ag NP exhibited a considerably lower mean CFU count than the other groups. Calcium hydroxide +2 % Cu NP was the next to exhibit a considerably lower mean CFU count than control and calcium hydroxide which had a statistically significant difference. This suggests that calcium hydroxide +2 % Ag NP had the lowest mean CFU count, by a large margin, followed by Calcium hydroxide +2 % Cu NP, calcium hydroxide, and control had the highest (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multiple comparison of mean difference in the CFUs of E. Faecalis b/w groups using Dunn's Post hoc Test.

| (I) Groups | (J) Groups | Mean Diff. (I-J) | 95 % CI for the Diff. |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Group 1 | Group 2 | 0.243 | 0.190 | 0.296 | <0.001a |

| Group 3 | 0.382 | 0.328 | 0.435 | <0.001a | |

| Group 4 | 0.436 | 0.383 | 0.489 | <0.001a | |

| Group 2 | Group 3 | 0.139 | 0.085 | 0.192 | <0.001a |

| Group 4 | 0.193 | 0.140 | 0.246 | <0.001a | |

| Group 3 | Group 4 | 0.055 | 0.001 | 0.108 | 0.04a |

Statistically Significant.

The results show that the mean CFU counts were highest in Group 1 (0.631 ± 0.047), followed by Group 2 (0.388 ± 0.071), Group 3 (0.250 ± 0.021), and Group 4 (0.195 ± 0.011). The analysis yielded a statistically significant difference in CFU counts among the groups (p < 0.001), suggesting meaningful variations in E. faecalis levels across them. The Kruskal-Wallis test confirmed that the CFU counts varied significantly across the groups, and Dunn's post hoc analysis further specified the differences between individual groups. (Table 1).

The pairwise comparison analysis indicates statistically significant differences in mean E. faecalis CFU counts across the groups, revealing a clear, progressive decline from Group 1 to Group 4. Specifically, Group 1 demonstrated significantly higher CFU counts compared to all other groups, with mean differences of 0.243 versus Group 2, 0.382 versus Group 3, and 0.436 versus Group 4, all with p-values <0.001, showing notable reductions in CFU counts relative to Group 1. Group 2 similarly displayed significantly elevated CFU counts compared to Group 3 (mean difference of 0.139, p < 0.001) and Group 4 (mean difference of 0.193, p < 0.001). Although the difference between Group 3 and Group 4 was more modest (mean difference of 0.055, p = 0.04), it remained statistically significant. These results collectively illustrate a consistent and statistically significant downward trend in E. faecalis CFU counts from Group 1 through Group 4, emphasizing distinct variations in bacterial load across consecutive groups. (Table 2).

Effect size was analysed using Cohen's d for pairwise comparisons. Substantial differences were found among all groups. Group 1 and Groups 2, 3, 4 revealed large effect sizes of d = 3.80, 10.61 and 12.46 respectively indicating significant reductions in CFU levels. Similarly, comparisons involving Group 2 and Groups 3, 4 also showed very large effect sizes of d = 2.67 and 3.78, emphasizing notable differences in effectiveness. Additionally, comparison between Groups 3 and 4 demonstrated a very large effect size of d = 3.44. These findings, are similar to the statistically significant values obtained from Dunn's post hoc test, confirming that interventions in Groups 2, 3, and 4 are highly effective in reducing CFU levels of E. faecalis, with progressively greater effects observed in Groups 3 and 4.

The results of the present study showed that the specimens that were not treated with any of the medicaments showed the highest number of bacterial colonies. The specimens treated with calcium hydroxide alone reported reduced bacterial colonies than the former. Ag NP incorporated calcium hydroxide and Cu NP incorporated calcium hydroxide showed better results in the reduction of bacterial colonies compared to specimens treated with calcium hydroxide alone. Thus, the results showed that group 4 and group 3 showed significantly least CFU followed by group 2 and group 1.

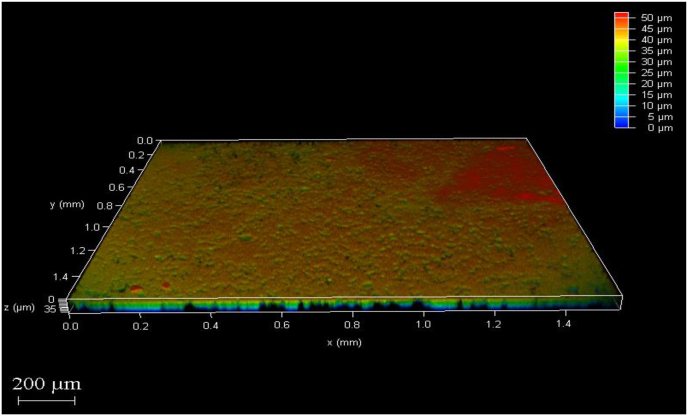

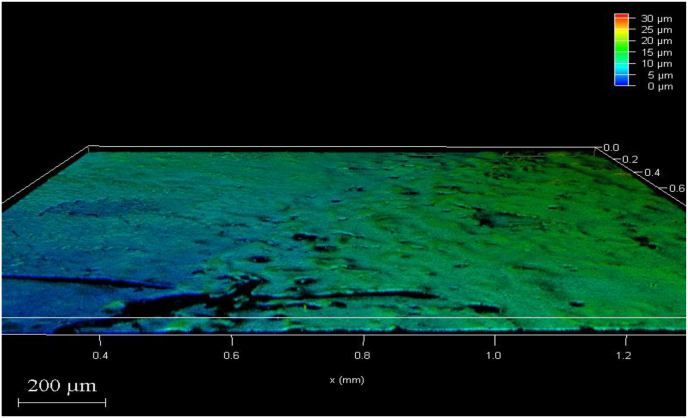

3.2. The 3D CLSM of E. faecalis biofilm

The CLSM images with colour gradient scale explain the various thickness of biofilm on the sample where the areas with maximum thickness are depicted in dark red colour and as the thickness reduces the colour changes according to the scale. The results of the CLSM investigation on the biofilm of E. faecalis reported that Groups 4 and 3 had the greatest reduction in biofilm thickness followed by group 2 and maximum biofilm thickness in group 1. (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

After treatment with Calcium hydroxide +2 % silver nanoparticles.

Fig. 2.

After treatment with Calcium hydroxide +2 % copper nanoparticles.

Fig. 3.

After treatment with Calcium hydroxide.

Fig. 4.

Control.

4. Discussion

Effectiveness of calcium hydroxide-based intracanal medicament mixed with Ag and Cu NP was evaluated against E. faecalis. The ability of calcium hydroxide to discharge hydroxyl ions in a liquid environment is thought to be responsible for its antibacterial activity. Calcium hydroxide denaturates proteins and DNA, then damages the cytoplasmic membrane, eliminating the bacteria.

E. faecalis demonstrates reduced sensitivity to fluctuations in alkaline pH. Furthermore, dentine serves as a buffer for the alkaline pH associated with calcium hydroxide. Consequently, the effectiveness of calcium hydroxide in combating E. faecalis is not particularly pronounced. However, the addition of Ag and Cu NP to calcium hydroxide has significantly increased the antibiofilm efficiency of the medicament against E. faecalis.

Ag NP is used in several medical fields as it prevents the growth of microorganisms, Ag NP with a size range of 10–100 nm has demonstrated substantial bactericidal activity against various pathogens. The results of this investigation corroborate those of Afkhami et al., who found that silver and copper NP had significantly greater antibacterial activity than calcium hydroxide.26 Kim et al. also ascribed Ag NPs' antibacterial action to free oxygen radical production, which triggers the cell's apoptotic process.27 Both studies concluded that free oxygen radicals originating from the surface of NP induce the apoptotic pathway in the bacterial cell.28

Numerous investigations have demonstrated the connection between Ag NP antibacterial properties, oxidative dissolution, and Ag ion release. Electron-donating groups that are abundant on membranes and proteins, such as sulfhydryl, amino, imidazole, phosphate, and carbonyl groups, are very attractive to Ag ions.17 As a result, they affect several bacterial cell components. Through electrostatic attraction, these ions cling to the cytoplasmic membrane and cell wall as well as sulfur-rich proteins, which damages these structures and increases membrane permeability. Additionally, this may cause free Ag ions to enter the cell and break ATP molecules, which would stop DNA replication or cause Ag NPs to produce reactive oxygen species.29 The absorption of Ag NP in Gram-negative bacteria is aided by pores in their outer membrane.30 Furthermore, Ag NP alters the effects of phosphotyrosine, which hinders organelle-to-organelle contact29,31 All of these processes lead to elevated levels of free oxygen radicals and oxidative stress in the cell, as well as protein denaturation-induced cell lysis.17 The huge surface area of nanoparticles is another key characteristic. Ag ion density is higher in Ag NPs with larger surface areas.32 Ag NPs also cause bacterial membranes to become much more unstable, more permeable, and capable of leaking cell components.33

Afkhami et al. also investigated calcium hydroxide in combination with Ag NP solution and Chlorhexidine. The results indicated that, in short term, Ag NPs were more effective against E. faecalis biofilm than the other agents used.34 Silver nanoparticles and calcium hydroxide together exhibit stronger anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and are more effective at eliminating germs from root canals.35 When tested against E. faecalis biofilm, silver and cadmium (Cd) nanoparticles as well as calcium hydroxide were found to be more efficient against bacteria than Cd NPs. However, calcium hydroxide did not produce better action against E. faecalis biofilm.

While certain reports have documented the advantage of using Ag NP, some have not found Ag NP to be particularly effective as an intracanal medication when compared with other endodontic medications. Previous report has shown that antibacterial properties of calcium hydroxide were not enhanced by the use of nanoparticles.36 Ag NPs were found to be less efficient than calcium hydroxide alone or in combination with Ag NP against E. faecalis in another investigation by Al abdul Mohsen et al..37 In their study, the bacterial count was reduced by calcium hydroxide when combined with Ag NP at one and two weeks,. However, the reduction was larger when calcium hydroxide was employed alone.37

The primary mechanism of the bactericidal activity of Cu is its continual electron-donating and electron-accepting capabilities. It generates a hydroxyl radical that can take part in various harmful reactions to macromolecules within the cell, including the oxidation of proteins and lipids. The hydrogen peroxide produced may cause a rise in the harmful hydroxyl radicals. It displaces iron from iron-sulfur clusters, competes with zinc or other metal ions, is crucial for protein binding sites, denatures DNA, and prevents cells from respiring. Bacteria subsequently evolved resistance mechanisms against Cu, including ion sequestration extracellularly, bacterial membrane impermeability on the outside and inside, removal of Cu proteins (metallothionein) from the cytoplasm and periplasm, and Cu efflux from the cell.38

Since Cu is a micronutrient and the immune system is effective in metabolizing it, Cu NPs can be used as an intracanal medicament.39,40 Residual Cu produces reactive oxygen species and attaches to the natural cofactors in metalloproteinases causing destruction to microorganisms.41 Additionally, Cu plays a part in innate immunity. It can boost the bactericidal activity during bacterial phagocytosis by quickening the blasting process inside phagocytes, which produces reactive oxygen species.42 Cu NP enhances the characteristics of pure Cu, which is a significant benefit since they can enter the endodontic biofilm-containing microscopic dentinal tubules, which have an average size of 5 μm.43 According to the results of the previous studies, the antibacterial properties of the combination of calcium hydroxide and Cu were better than those of calcium hydroxide alone, which is consistent with the findings of the current investigation.44,45

A previous study found that utilizing calcium hydroxide paste was less effective against biofilms than incorporating it with silver, copper, zinc, or magnesium. However, the most effective combination turned out to be calcium hydroxide and 1 % Ag NP.46 Because CLSM can measure the spatial arrangement of biofilm and provide a three-dimensional (3D) image of the biofilm, it has been a preferred method for investigating biofilms.47 The bio-volume of the bacteria in E. faecalis biofilms was effectively assessed using CLSM analysis. Comparing specimens treated with calcium hydroxide modified by Ag and Cu NP to specimens treated with conventional calcium hydroxide, the latter revealed the highest degree of biofilm containing E. faecalis.

A systemic investigation of the antibacterial effect of calcium hydroxide as an intracanal medicine by Sathorn et al. revealed limited disinfection action within the root canal system.48 According to a previous study, the antibacterial effects of copper and silver in conjunction with calcium hydroxide were greater than the individual agent when used alone.49 Ag has always shown superior antibacterial properties than Cu, both when used alone and in combination with other materials.50,51 The Cu NP accumulates on the cell surface, causing alteration of membrane potential and damage to cell integrity, it also destroys the balance of reactive oxygen species and develops oxidative stress. While, the Ag NP interrupts ATP production, and DNA replication, and disrupts the cell wall and cell membrane by reactive oxygen species. Because these antibacterial nanoparticles interact with a variety of sites in microbial cells, including DNA and cell walls, they prevent bacteria from developing resistance to the NP. Free silver ion content is closely proportional to their toxicity. Ag NPs can readily change the typical action of bioactive chemicals, eukaryotic cells, and tissues because of their nanoscale size. Ag NP-induced oxidative stress gives rise to free radicals that build up in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm. Because of its huge contact area, Ag NPs are more hazardous, but when they interact with organic substances in vivo, their toxicity gradually diminishes.

Quantification of Ag and Cu NP ions release into the tubules of dentin at the level of apical constriction is crucial to assess how it affects the cytotoxic response in the apical tissues. Their special qualities allow improved disinfection, efficient destruction of biofilms, and even tissue regeneration. It is certain that more advancements and improvements will result from ongoing research and development in this area. To guarantee the responsible and safe application of nanoparticles in clinical practice, care must be taken. Dental practitioners can ultimately improve patients' oral health and well-being by offering more individualized and effective treatment options by carefully adopting these innovations.

4.1. Limitations and future directions of the study

Endodontic biofilm consists of a diverse array of microbial species; however, the current study has specifically concentrated on Enterococcus faecalis which highlights need for further investigations in multispecies biofilm. Synthesis of nanoparticles is still a limitation and is not being routinely employed in clinical practice. Clinical translation of nanoparticle-based disinfection is still limited in endodontics. There are potential concerns about the cytotoxicity of the particles and especially its effectiveness in patients is scarce. Hence, in the future more clinical studies are warranted with the usage of this agent. Until the agent is clinically explored to its full potential, its usage is questionable.

5. Conclusion

Within the limitations of the study,it can be concluded that, combining Ag and Cu NP with calcium hydroxide intracanal medication substantially enhances its antibacterial activity against E. faecalis. These NPs increase the root canal treatment success rate by eliminating E. faecalis from the root canal system. Nevertheless, additional in vivo research is required to determine whether these medications are suitable for clinical use due to the limitations of the in vitro situation.

Consent

Not available.

Funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- 1.Stewart P.S., Costerton J.W. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Lancet. 2001;358:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balto H., Bukhary S., Al-Omran O., BaHammam A., Al-Mutairi B. Combined effect of a mixture of silver NP and calcium hydroxide against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm. J Endod. 2020 Nov 1;46(11):1689–1694. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nair N., James B., Devadathan A., Johny M.K., Mathew J., Jacob J. Comparative evaluation of antibiofilm efficacy of chitosan NP- and zinc oxide NP-incorporated calcium hydroxide-based sealer: an in vitro study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018;9:434–439. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_225_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siqueira Jr JF., Lopes H. Mechanisms of antimicrobial activity of calcium hydroxide: a critical review. Int Endod J. 1999 Sep;32(5):361–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behnen M.J., West L.A., Liewehr F.R., Buxton T.B., McPherson I.I.I.J.C. Antimicrobial activity of several calcium hydroxide preparations in root canal dentin. J Endod. 2001 Dec 1;27(12):765–767. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portenier I., Waltimo T., Ørstavik D., Haapasalo M. The susceptibility of starved, stationary phase, and growing cells of Enterococcus faecalis to endodontic medicaments. J Endod. 2005 May 1;31(5):380–386. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000145421.84121.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siqueira Jr JF., Lopes H.P., de Uzeda M. Recontamination of coronally unsealed root canals medicated with camphorated paramonochlorophenol or calcium hydroxide pastes after saliva challenge. J Endod. 1998 Jan 1;24(1):11–14. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(98)80204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haapasalo M., Ørstavik D. In vitro infection and of dentinal tubules. J Dent Res. 1987 Aug;66(8):1375–1379. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660081801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safavi K.E., Spngberg L.S., Langeland K. Root canal dentinal tubule disinfection. J Endod. 1990 May 1;16(5):207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)81670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook J., Nandakumar R., Fouad A.F. Molecular-and culture-based comparison of the effects of antimicrobial agents on bacterial survival in infected dentinal tubules. J Endod. 2007 Jun 1;33(6):690–692. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballal V., Kundabala M., Acharya S., Ballal M. Antimicrobial action of calcium hydroxide, chlorhexidine and their combination on endodontic pathogens. Aust Dent J. 2007 Jun;52(2):118–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krithikadatta J., Indira R., Dorothykalyani A.L. Disinfection of dentinal tubules with 2% chlorhexidine, 2% metronidazole, bioactive glass when compared with calcium hydroxide as intracanal medicaments. J Endod. 2007 Dec 1;33(12):1473–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao W., Zhang Y., Wang X., et al. Development of a novel resin-based dental material with dual biocidal modes and sustained release of Ag+ ions based on photocurable core-shell AgBr/cationic polymer nanocomposites. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2017 Jul;28(7):103. doi: 10.1007/s10856-017-5918-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal P., Hall J.B., McLeland C.B., Dobrovolskaia M.A., McNeil S.E. Nanoparticle interaction with plasma proteins as it relates to particle biodistribution, biocompatibility and therapeutic efficacy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009 Jun 21;61(6):428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antimicrobial activity of iron oxide nanoparticle upon modulation of nanoparticle-bacteria interface | Sci Rep [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/srep14813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Samiei M., Farjami A., Dizaj S.M., Lotfipour F. Nanoparticles for antimicrobial purposes in Endodontics: a systematic review of in vitro studies. Mater Sci Eng C. 2016 Jan 1;58:1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang S., Zheng J. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: structural effects. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2018 Jul;7(13) doi: 10.1002/adhm.201701503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramyadevi J., Jeyasubramanian K., Marikani A., Rajakumar G., Rahuman A.A. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of copper nanoparticles. Mater Lett. 2012 Mar 15;71:114–116. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cava R.J. Structural chemistry and the local charge picture of copper oxide superconductors. Science. 1990 Feb 9;247(4943):656–662. doi: 10.1126/science.247.4943.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massa M.A., Covarrubias C., Bittner M., et al. Synthesis of new antibacterial composite coating for titanium based on highly ordered nanoporous silica and silver nanoparticles. Mater Sci Eng C. 2014 Dec 1;45:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren G., Hu D., Cheng E.W., Vargas-Reus M.A., Reip P., Allaker R.P. Characterisation of copper oxide nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009 Jun 1;33(6):587–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Usman M.S., Zowalaty M.E., Shameli K., Zainuddin N., Salama M., Ibrahim N.A. Synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial properties of copper nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed. 2013 Nov;21:4467–4479. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S50837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devaraj S., Jagannathan N., Neelakantan P. Antibiofilm efficacy of photoactivated curcumin, triple and double antibiotic paste, 2% chlorhexidine and calcium hydroxide against Enterococcus fecalis in vitro. Sci Rep. 2016 Apr 21;6 doi: 10.1038/srep24797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yousefshahi H., Aminsobhani M., Shokri M., Shahbazi R. Anti-bacterial properties of calcium hydroxide in combination with silver, copper, zinc oxide or magnesium oxide. European journal of translational myology. 2018 Jul 7;28(3) doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2018.7545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tülü G., Bü Kaya, Çetin E.S., Köle M. Antibacterial effect of silver NP mixed with calcium hydroxide or chlorhexidine on multispecies biofilms. Odontology. 2021 Oct;109(4):802–811. doi: 10.1007/s10266-021-00601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javidi M., Afkhami F., Zarei M., Ghazvini K., Rajabi O. Efficacy of a combined nanoparticulate/calcium hydroxide root canal medication on elimination of Enterococcus faecalis. Aust Endod J. 2014;40:61–65. doi: 10.1111/aej.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingle A.P., Duran N., Rai M. Bioactivity, mechanism of action, and cytotoxicity of copper-based NP: a review. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:1001–1009. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mikhailova E.O. Silver NP: mechanism of action and probable bio-application. J Funct Biomater. 2020 Nov 26;11(4):84. doi: 10.3390/jfb11040084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bapat R.A., Chaubal T.V., Joshi C.P., et al. An overview of application of silver nanoparticles for biomaterials in dentistry. Mater Sci Eng C. 2018 Oct 1;91:881–898. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radzig M.A., Nadtochenko V.A., Koksharova O.A., Kiwi J., Lipasova V.A., Khmel I.A. Antibacterial effects of silver nanoparticles on gram-negative bacteria: influence on the growth and biofilms formation, mechanisms of action. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013 Feb 1;102:300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shrivastava S., Bera T., Singh S.K., Singh G., Ramachandrarao P., Dash D. Characterization of antiplatelet properties of silver nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2009 Jun 23;3(6):1357–1364. doi: 10.1021/nn900277t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qing Y.A., Cheng L., Li R., et al. Potential antibacterial mechanism of silver nanoparticles and the optimization of orthopedic implants by advanced modification technologies. Int J Nanomed. 2018 Jun;5:3311–3327. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S165125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Annie S. Antibacterial nanoparticles endodontics: a narrative review. Int Endod J. 2016;42(10):1417–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afkhami F., Pourhashemi S.J., Sadegh M., Salehi Y., Fard M.J.K. Antibiofilm efficacy of silver nanoparticles as a vehicle for calcium hydroxide medicament against Enterococcus faecalis. J Dent. 2015 Dec;43(12):1573–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nasim I., Shamly M., Jaju K., Vishnupriya V., Jabin Z. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of a nanoparticle based intracanal drugs. Bioinformation. 2022;18(5):450–454. doi: 10.6026/97320630018450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antimicrobial Efficacy of Silver Nanoparticles with and with... : Dental Hypotheses [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 26]. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/dhyp/fulltext/2017/08040/antimicrobial_efficacy_of_silver_nanoparticles.3.aspx.

- 37.Alabdulmohsen Z.A., Saad A.Y. Antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles against Enterococcus faecalis. Saudi Endod J. 2017 Apr;7(1):29. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grass G., Rensing C., Solioz M. Metallic copper as an antimicrobial surface. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011 Mar 1;77(5):1541–1547. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02766-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rojas B., Soto N., Villalba M., Bello-Toledo H., Meléndrez-Castro M., Sánchez-Sanhueza G. Antibacterial activity of copper nanoparticles (Cunps) against a resistant calcium hydroxide multispecies endodontic biofilm. Nanomaterials. 2021 Aug 31;11(9):2254. doi: 10.3390/nano11092254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Şahin M., Koçak N., Erdenay D., Arslan U. Zn(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Pb(II) complexes of tridentate asymmetrical Schiff base ligands: synthesis, characterization, properties and biological activity. Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013;103:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu Y., Chang F.M., Giedroc D.P. Copper transport and trafficking at the host–bacterial pathogen interface. Accounts Chem Res. 2014 Dec 16;47(12):3605–3613. doi: 10.1021/ar500300n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dupont C.L., Grass G., Rensing C. Copper toxicity and the origin of bacterial resistance—new insights and applications. Metallomics. 2011 Nov;3(11):1109–1118. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00107h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vergara Llanos D., Koning T., Pavicic M., et al. Antibacterial and cytotoxic evaluation of copper and zinc oxide NP as a potential disinfectant material of connections in implant provisional abutments: an in vitro study. Arch Oral Biol. 2021;122 doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.105031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuss Z., Mizrahi A., Lin S., Cherniak O., Weiss E. A laboratory study of the effect of calcium hydroxide mixed with iodine or electrophoretically activated copper on bacterial viability in dentinal tubules. Int Endod J. 2002;35:522–526. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knappwost A. Das Depotophorese-Verfahren mit Kupfer-Calciumhydroid, die zur systematischen ausheilung fuhrende alternative in dir endodontie. Das Deutsche Zahnärzteblatt. 1993;102:618–628. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yousefshahi H., Aminsobhani M., Shokri M., Shahbazi R. Anti-bacterial properties of calcium hydroxide in combination with silver, copper, zinc oxide or magnesium oxide. Eur J Transl Myol. 2018 Jul 10;28(3):7545. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2018.7545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Multiple Factors Modulate Biofilm Formation by the Anaerobic Pathogen Clostridium difficile Tanja Ðapa, a Rosanna Leuzzi, a Yen K. Ng, B Soza T. Baban, B Roberto Adamo, a Sarah A. Kuehne, B Maria Scarselli, a Nigel P. Minton, B Davide Serruto, a Meera Unnikrishnana. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Sathorn C., Parashos P., Messer H. Antibacterial efficacy of calcium hydroxide intracanal dressing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J. 2007;40:2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McLean R.J., Hussain A., Sayer M., Vincent P.J., Hughes D.J., Smith T.J. Antibacterial activity of multilayer silver–copper surface films on catheter material. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:895–899. doi: 10.1139/m93-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du W.-L., Niu S.-S., Xu Y.-L., Xu Z.-R., Fan C.-L. Antibacterial activity of chitosan tripolyphosphate NP loaded with various metal ions. Carbohydr Polym. 2009;75:385–389. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Top A., Ülkü S. Silver, zinc, and copper exchange in a Na-clinoptilolite and resulting effect on antibacterial activity. Appl Clay Sci. 2004;27:13–19. [Google Scholar]