Abstract

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is used universally for accurate exponential amplification of DNA. We describe a high error rate at mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeat sequence motifs. Subcloning of PCR products allowed sequence analysis of individual DNA molecules from the product pool and revealed that: (1) monothymidine repeats longer than 11 bp are amplified with decreasing accuracy, (2) repeats generally contract during PCR because of the loss of repeat units, (3) Taq and proofreading polymerase Pfu generate similar errors at mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeats, and (4) unlike the parent PCR product pool, individual clones containing a single repeat length produce no “shadow bands”. These data demonstrate that routine PCR amplification alters mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeat lengths. Such sequences are common components of genetic markers, disease genes, and intronic splicing motifs, and the amplification errors described here can be mistaken for polymorphisms or mutations.

Keywords: polymerase chain reaction, nucleotide repeat sequences, shadow bands

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is one of the most widely used techniques in molecular biology and has made possible a great variety of both diagnostic and research applications. Examples are the detection of gene mutations, the analysis of polymorphic markers and microsatellite loci, analysis of gene expression, DNA cloning, and site directed mutagenesis. Because PCR involves the exponential amplification of target sequences, a high degree of polymerase fidelity is essential if the introduction of a large number of replication errors during the PCR reaction is to be avoided. Most commercially available Taq polymerases introduce errors at the rate of approximately 10−5 to 10−6 point mutations/bp/duplication, with higher fidelity polymerases such as Pfu and Deep Vent generating up to eight times fewer errors.1 In contrast, we found that mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeats were not faithfully reproduced during PCR.

Methods and results

A stretch of 26 A nucleotides in intron 5 of the hMSH2 gene, termed Bat-26,2 was amplified from the genomic DNA of several healthy individuals under routine PCR conditions (200 ng genomic DNA and 1.25 U AmpliTaq (Perkin Elmer, Branchburg, New Jersey, USA) in 50 μl containing 1.5mM MgCl2, 300 ng each primer,2 and 200μM dNTPs). Direct sequencing of the PCR product produced an illegible sequence after the mononucleotide repeat, indicating a possible difference between two alleles. Such allele differences, along with any polymerase slippage incurred during the PCR reaction, can both be visualised using gene scanning technology. However, for our study a strategy of subcloning and sequencing of individual clones of the PCR product was used for the qualitative determination of the composition of the PCR product pool, by identifying the sequences of individual DNA molecules. This revealed differences in the length of the Bat-26 poly-A stretch, which varied from 19 to 28 bp, which is incompatible with the concept of simple polymorphism or mutation (table 1 ▶). The sequencing of more than 30 individual clones revealed that the repeat was predominantly shortened, with only 35% of the clones containing the predicted sequence of (A)26 (table 1 ▶). These data suggested that a systematic polymerase error had taken place during the PCR reaction, which was specific to the mononucleotide repeat.

Table 1.

Repeat length of individual DNA sequences subcloned from a PCR product pool after amplification of mononucleotide or dinucleotide repeat markers

| Locus | Repeat | Repeat length and corresponding number of clones | N | % Correct | |||||||||

| RAC1 | (T)9 | 9 | |||||||||||

| (Taq) | 10 | 10 | 100 | ||||||||||

| RAC1 | (T)11 | 10 | 11 | ||||||||||

| (Taq) | 1 | 9 | 10 | 90 | |||||||||

| Bat–13 | (T)13 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |||||

| (Taq) | 9 | 8 | 20 | 19 | – | 1 | 1 | 58 | 33 | ||||

| (Pfu) | – | – | 2 | 16 | 1 | – | – | 19 | 84 | ||||

| Bat–21 | (T)21 | 16 | 17 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | ||

| (Taq) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | – | 6 | 5 | 19 | 3 | – | 29 | 3 | |

| (Pfu) | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 19 | 0 | |

| Bat–21 | (TA)11 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||||||

| (Taq) | 1 | 2 | 21 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 29 | 7 | |||||

| (Pfu) | – | 4 | 12 | 3 | – | – | 19 | 16 | |||||

| Bat–21 | (T)21 + (TA)11 | 35 | 36 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | |||

| (Taq) | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 10 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 29 | 34 | ||

| (Pfu) | – | – | – | 2 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 19 | 16 | ||

| Bat–26 | (A)26 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | ||

| (Taq) | – | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 34 | 35 | |

| (Pfu) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | – | 1 | 40 | 23 | |

| D15S128 | (CA)18 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||||||

| (Taq) | – | 1 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 14 | 64 | ||||||

| (Pfu) | 2 | – | 2 | 6 | 5 | 15 | 33 | ||||||

Each locus was amplified by PCR with either Taq or Pfu, as indicated.

The number of clones found containing varying numbers of repeat units is shown, with the correct number of repeats for each locus shown in bold.

N, total number of cloned inserts sequenced for each locus; % Correct, the percentage containing the exact repeat length.

To determine in more detail the performance of PCR amplification at similar sequences, repeats of 21, 13, 11, and nine monothymidines were amplified and subcloned. The polypyrimidine tract of the hMLH1 intron 11 splice acceptor site contains a (T)21 monothymidine repeat, termed Bat-21 (AcNb U40971),3 with an adjacent (TA)11 dinucleotide repeat. The polypyrimidine tract preceding exon 2 in the gene hMSH2 contains a (T)13 stretch, termed Bat-13 (AcNb U41207),3 and intron 4 of the human RAC1 gene contains both (T)9 and (T)11 runs (AcNb AJ132695).4 As shown in table 1 ▶, sequencing of individual cloned PCR products revealed incorrect amplification of the (T)21 and (T)13 repeats, whereas (T)9 was replicated faithfully. The limit for correct amplification was reached with (T)11, where 90% of the cloned products contained the predicted number of thymidines. The predominant observation was of repeat contraction; the (T)21 repeat appeared to expand, but this tendency was accounted for upon inspection of individual Bat-21 clones by A-T transversions in the adjacent TA repeat. Two different amplification errors at this combined repeat therefore led to an overall expansion of the poly-T stretch.

To determine the performance of the high fidelity Pfu polymerase at such sequences, the strategy was repeated for the above markers (with 200 ng genomic DNA and 2.5 U Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) in 100 μl containing 2mM MgCl2, 600 ng of each primer, and 250μM dNTPs for 30 cycles (95°C for 45 seconds; annealing at 60°C for one minute; 72°C for two minutes) and showed that the limit for correct amplification by Pfu was raised from (T)11 to (T)13, but that longer repeats were also incorrectly amplified (table 1 ▶).

Dinucleotide repeats are another group of frequently amplified genetic markers. We amplified the dinucleotide repeat D15S128 (AcNb Z17197)5 in an individual previously determined to be homozygous for (CA)18, the allele with the highest frequency. PCR was carried out with both Taq and Pfu polymerases, followed by subcloning and sequencing of individual inserts. Both enzymes were found to amplify this repeat with a high error rate (table 1 ▶), as seen for the longer mononucleotide repeats.

Trinucleotide (CAG)n repeats occur in the coding regions of disease causing genes, such as the androgen receptor6 or Huntington's and Machado Joseph disease genes. Expansion of the triplets is associated with severe neurodegeneration,7, 8 and genetic analysis of patients relies on PCR amplification of the repeats from genomic DNA. To test for possible errors introduced by in vitro amplification, the (CAG)n and (GGC)n trinucleotide repeats in the first coding exon of the androgen receptor gene (AcNb NM_000044)6 were amplified by both Taq and Pfu, revealing that over 80% of clones contained the correct sequences (data not shown), a level of error compatible with direct sequencing. These data are also consistent with previous observations that longer nucleotide repeat units are associated with less polymerase error.29

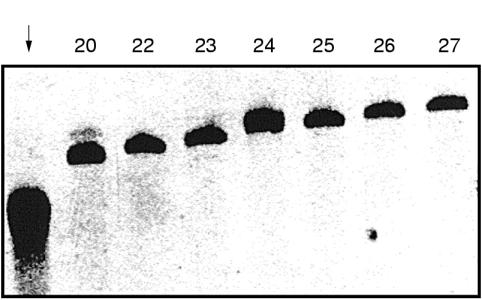

An accepted feature of nucleotide repeat marker analysis, both in mutation detection or analysis of genetic polymorphisms, is the occurrence of staining patterns called “shadow bands”.10–12 When PCR products of such markers are separated by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis they appear as broad bands or separate into a series of individual shadows. To determine the contribution of PCR polymerase errors to this phenomenon, a Bat-26 PCR product amplified with Taq was run on a polyacrylamide gel alongside several individual clones of the same product with a known number of A nucleotides. The latter were excised from the cloning vector by restriction digestion. As shown in fig 1 ▶, the PCR product appeared as a broad, smeared area of adjacent shadow bands, whereas the cloned fragments of defined length migrated as discrete single bands, forming a size ladder according to the length of the poly-A stretch. This demonstrates that the phenomenon of shadow bands commonly observed in PCR based genetic analysis of microsatellite loci can be attributed at least in part to artefactual PCR amplification errors. In addition, others have shown that improper annealing of PCR products during non-denaturing gel electrophoresis can further compound the occurrence of multiple band patterns.13

Figure 1.

Non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis comparing the Taq polymerase amplified Bat-26 marker and individual clones obtained after subcloning this PCR product. The original PCR product (indicated by the arrow) was a pool of molecules with different repeat lengths and it migrates as a blurred area composed of “shadow bands”. In contrast, cloned individual molecules containing a known number of repeated adenines (indicated by numbers) are seen as discrete bands. The individual clones contain an extra 11 bp of vector sequence after restriction digestion of the cloned insert with EcoRI and thus migrate more slowly than the original PCR product.

Discussion

In our study, we describe a high error rate in PCR amplification of mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeats from genomic DNA. Our findings relate mainly to monothymidine/monoadenosine repeats, and suggest that the longer the repeat, the greater the errors made during amplification. Although our additional data include only TA and CA dinucleotide repeats, we believe it is possible to extrapolate the general rule that PCR amplification of mononucleotide or dinucleotide repeats results in error. Use of the high fidelity proofreading polymerase Pfu in place of Taq restricted the occurrence of such errors only in the case of short monothymidine repeats. We think that contraction of the repeat itself is the most common type of error occurring during PCR amplification. This type of error is commonly referred to as polymerase “slippage” and is probably caused by slipped strand mispairing.14, 15 Alternatively, the loss or gain of nucleotide repeat units without affecting the surrounding sequence10, 12 can be explained by mega-priming. In this case, fragments that were either incompletely synthesised or broken in their repetitive element during PCR can anneal under formation of mismatches, then extend, resulting in repeat length variation, independent of polymerase type or PCR conditions. This conclusion was drawn from work using synthetic oligonucleotides in the absence of genomic DNA.16, 17 Previous work has suggested that such polymerase error can be reduced by optimisation of PCR reaction conditions and buffer composition.1, 13, 18–20 In our present study, a fixed set of routine PCR conditions were used to determine the effect that repeat size and length alone would have on polymerase error rate. Our data lead to the conclusion that polymerase performance itself imposes considerable constraints upon PCR amplification fidelity independent of PCR conditions, primer composition, or PCR product length.

Although the molecular mechanism of the described errors during amplification of repetitive DNA sequence motifs remains a matter of discussion, such errors are frequently encountered during cloning or genetic analysis of introns, polypyrimidine tracts, or microsatellite markers. In addition, they are of great interest during analysis and diagnosis of various diseases. For example, mononucleotide and dinucleotide microsatellite sequences are hotspots for mammalian polymerase error during in vivo DNA replication,21 and are highly unstable in tumours resulting from mismatch repair deficiency.22, 23 On this basis, they are widely used as markers for certain cancer syndromes,24 including hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer.25 Furthermore, dinucleotide repeats are used as polymorphic markers to determine heterozygosity. With the increased use of automated DNA sequencing, the described in vitro amplification errors at repeat motifs can easily be mistaken, in research and diagnostics, for polymorphism or mutation.

Acknowledgments

We thank C Caldas for comments on the manuscript, L Vieira for donating D15S128 primers, S Pedro for running the ABI sequencing apparatus, and S Beck and S Vieira for assistance with high performance liquid chromatography analysis. This study was supported by PRAXIS XXI grant 2/2.1/SAU/1397/95 from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, and PRAXIS XXI postdoctoral fellowship BPD/4140/96 to LAC.

References

- 1.Cline J, Braman JC, Hogrefe HH. PCR fidelity of Pfu DNA polymerase and other thermostable DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res 1996;24:3546–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoang JM, Cottu PH, Thuille B, et al. Bat-26, an indicator of the replication error phenotype in colorectal cancers and cell lines. Cancer Res 1997;57:300–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou XP, Hoang JM, Cottu P, et al. Allelic profiles of mononucleotide repeat microsatellites in control individuals and in colorectal tumours with or without replication errors. Oncogene 1997;15:1713–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matos P, Skaug J, Mârques B, et al. Small GTPase Rac1: structure, localisation and expression of the human gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000;277:741–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissenbach J, Gyapay G, Dib C, et al. A second-generation linkage map of the human genome. Nature 1992;359:794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lubahn DB, Brown TR, Simental JA, et al. Sequence of the intron/exon junctions of the coding region of the human androgen receptor gene and identification of a point mutation in a family with complete androgen insensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989;86:9534–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuji S. Molecular genetics of triplet repeats: unstable expansions of triplet repeats as a new mechanism for neurodegenerative diseases. Intern Med 1997;36:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoghbi HY, Orr HT. Glutamine repeats and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci 2000;23:217–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh PS, Fildes NJ, Reynolds R. Sequence analysis and characterization of stutter products of the tetranucleotide repeat locus vWA. Nucleic Acids Res 1996;24:2807–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauge XY, Litt M. A study of the origin of “shadow bands” seen when typing dinucleotide repeat polymorphisms by the PCR. Hum Mol Genet 1993;2:411–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litt M, Hauge XY, Sharma V. Shadow bands seen when typing polymorphic dinucleotide repeats: some causes and cures. Biotechniques 1993;15:280–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray V, Monchawin C, England PR. The determination of the sequences present in the shadow bands of a dinucleotide repeat PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 1993;21:2395–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bovo D, Rugge M, Shiao YH. Origin of spurious multiple bands in the amplification of microsatellite sequences. J Clin Pathol: Mol Pathol 1999;52:50–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levinson G, Gutman GA. Slipped-strand mispairing: a major mechanism for DNA sequence evolution. Mol Biol Evol 1987;4:203–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krawczak M, Cooper DN. Gene deletions causing human genetic disease: mechanisms of mutagenesis and the role of the local DNA sequence environment. Hum Genet 1991;86:425–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamdan H, Tynan JA, Fenwick RA, et al. Automated detection of trinucleotide repeats in fragile X syndrome. Mol Diagn 1997;2:259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behn-Krappa A, Doerffler W. Enzymatic amplification of synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides: implications for triplet expansions in the human genome. Hum Mutat 1994;3:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brail L, Fan E, Levin DB, et al. Improved polymerase fidelity in PCR-SSCPA. Mutat Res 1993;303:171–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyons-Darden T, Topal MD. Effects of temperature, Mg2+ concentration and mismatches on triplet-repeat expansion during DNA replication in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res 1999;27:2235–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu MJ, Chow LW, Hsieh M. Amplification of GAA/TTC triplet repeat in vitro: preferential expansion of (TTC)n strand. Biochim Biophys Acta 1998;1407:155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunkel TA. The mutational specificity of DNA polymerase-β during in-vitro DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem 1985;260:5787–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu B, Nicolaides NC, Markowitz S, et al. Mismatch repair gene defects in sporadic colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability. Nat Genet 1995;9:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marra G, Schär P. Recognition of DNA alterations by the mismatch repair system. Biochem J 1999;388:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Boland CR, Hamilton SR, et al. National Cancer Institute workshop on hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome: meeting highlights and Bethesda guidelines. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:1758–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lynch HT. Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Cytogenet Cell Genet 1999;86:130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]