Abstract

This report describes the concomitant occurrence of the JC virus (JCV) induced demyelinating disease progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) and a primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNS-L) in a patient with AIDS. Postmortem neuropathological examination revealed characteristic features of PML including multiple lesions of demyelination, enlarged oligodendrocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei (many containing eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions), and enlarged astrocytes with bizarre hyperchromatic nuclei. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated the expression of the JCV capsid protein VP-1 in the nuclei of infected oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. The PCNS-L lesion located in the basal ganglia was highly cellular, distributed perivascularly, and consisted of large atypical plasmacytoid lymphocytes. Immunohistochemical examination of this neoplasm identified it to be of B cell origin. Moreover, expression of the JCV oncogenic protein, T antigen, was detected in the nuclei of the neoplastic lymphocytes. This study provides the first evidence for a possible association between JCV and PCNS-L.

Keywords: JC virus, progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy, primary central nervous system lymphoma, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, demyelination, T antigen

Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) is a human demyelinating disease that results from the selective destruction of myelin producing oligodendrocytes by the human polyoma JC virus (JCV) (reviewed by Major et al).1 Seroepidemiological studies indicate that JCV infection is very common, with approximately 70–90% of adults possessing JCV specific antibodies.2,3 Despite this high rate of infection, PML usually emerges as an opportunistic infection of the central nervous system (CNS) in immunocompromised patients. Although once considered a relatively rare disease, PML has become more common as a result of AIDS (reviewed in Berger and Concha),4 and is estimated to occur in up to 5% of all patients with AIDS.5 In addition to CNS opportunistic infections such as PML, CNS neoplastic diseases occur with increased frequency in immunosuppressed patients, including primary CNS lymphoma (PCNS-L). Although PML and PCNS-L are common in immunosuppressed patients, their concomitant occurrence is relatively rare. Here, we describe the rare co-occurrence of PML and PCNS-L and demonstrate expression of JCV large tumour antigen (T antigen) in the tumour cells. In the light of earlier observations of the presence of JCV in B cells and the oncogenic potential of the JCV early protein, we discuss the importance of these findings in the pathogenesis of PCNS-L.

Case report

A 33 year old homosexual man with a five year history of AIDS was admitted to Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia after being found with altered mentation in his parked car. AIDS had been complicated by three episodes of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), gastroparesis, pancreatitis related to pentamidine, herpes, and candida oesophagitis. The patient completed a course of antibiotics for pseudomonas septicaemia six weeks before admission.

On admission, the patient was awake but disoriented to time and place and unable to follow commands. His temperature was 101.5°F, blood pressure was 115/70 mm Hg, heart rate was 84 beats/minute, and respiration was 16 breaths/minute and unlaboured. The patient was not able to cooperate fully with the neurological examination, but cranial nerves II–XII were intact and the deep tendon reflexes were symmetric and 3+ in the upper extremities and 2+ in the lower extremities. Gait was unsteady. On admission, complete blood cell count revealed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/litre, haemoglobin was 86 g/litre, haematocrit 24.6, and platelets were 134 × 103. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was clear and colourless, with a normal glucose of 500 mg/litre (normal, 400–700), and a slightly increased protein concentration of 1010 mg/litre (normal, 150–550). Gram stain, acid fast stain, and India ink preparation of the CSF revealed no microorganisms, and bacterial antigens were negative for Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Toxoplasmosis titre, serum cryptococcal antigen, and blood cultures for bacteria and Mycobacterium avium intracellulare (MAI) were negative. Cytomegalovirus titre was positive one week before admission.

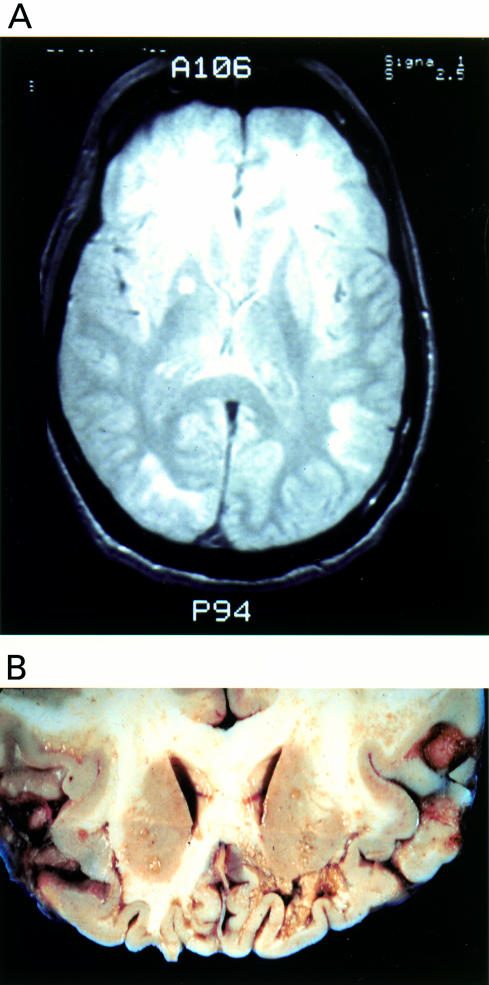

Axial computed tomography (CT) images of the brain were obtained on admission and compared with images obtained three months previously. CT scan showed new bilateral, inferior frontal white matter hypoattenuation with no enhancement, stable cortical and central atrophy, and worsening sphenoid sinus inflammation. Chest radiographs were within normal limits. Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium two days after admission revealed atrophy, prominence of the right temporal horn, and abnormal T2 weighted images in the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes (fig 1A ▶).

Figure 1.

Neuroimaging and macroscopic features. (A) T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showing extensive hyperintense signal abnormalities in the subcortical white matter of the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes. (B) A coronal section of the brain at necropsy demonstrating demyelinating lesions in the white matter ranging from discolouration to severe cavitation.

Soon after admission the patient experienced a tonic clonic seizure and was treated with valium and dilantin without subsequent seizure activity. The patient received an empirical 11 day course of intravenous vancomycin, mezlocillin, and gentamycin. Chest radiographs five days after admission revealed upper lobe infiltrates and clindamycin and primaquin were administered at therapeutic doses to treat possible PCP (because the patient had an allergy to sulphur and a history of pancreatitis related to pentamidine). Although his mental status improved 10 days after admission, it worsened progressively over the next weeks. Twelve days after admission, ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin were started as empirical treatment for MAI because of a persisting temperature increase to 105°F. The patient developed swallowing difficulty and eventually was unable to take anything by mouth. Parenteral morphine was administered as needed to maintain comfort and the patient died 29 days after admission.

Postmortem examination

Postmortem examination of the brain revealed multiple diffuse patches of discolouration and softening of the subcortical white matter in the frontal lobe, especially towards the ventral surface of the brain, where they had a cavitary appearance (fig 1B ▶). This destructive process extended caudally into the right parietal and temporal lobes, below the right putamen, and into the occipital lobe.

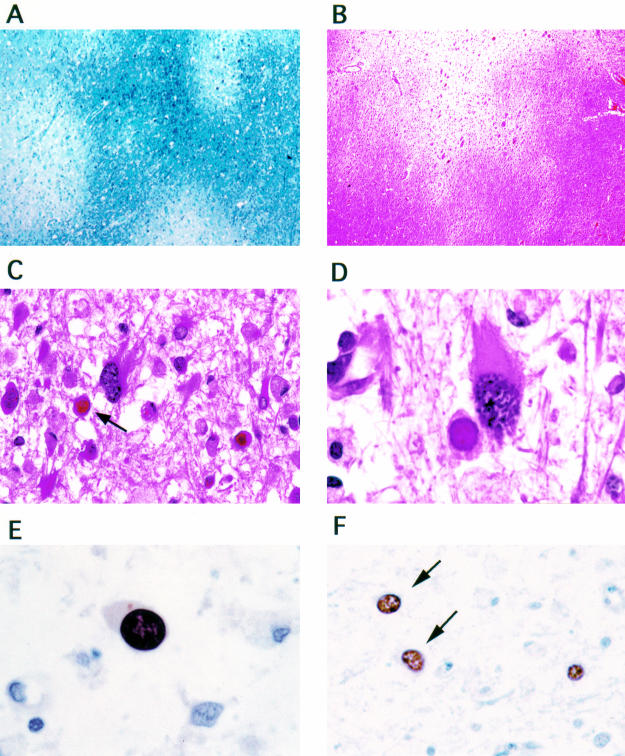

Histological sections of these lytic areas showed multiple, small and moderate sized areas of demyelination, some of them confluent, with relative good preservation of axons (fig 2A, B ▶). In the areas of demyelination, there were multiple enlarged oligodendrocytes, many containing eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions, and numerous enlarged bizarre astrocytes with pleomorphic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (fig 2C, D ▶). Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated the expression of the viral capsid protein VP-1 in the nuclei of oligodendrocytes and transformed astrocytes (fig 2E, F ▶). In the cortex of the frontal and temporal lobes, small collections of reactive lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils consistent with microabscesses were present.

Figure 2.

Histological and immunohistochemical characteristics of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy lesions. Extensive areas of demyelination in the white matter are evident (A, luxol fast blue; B, haematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×10). Infected oligodendrocytes with eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions (arrow) and transformed bizarre astrocytes are present in the demyelination areas (C: original magnification, ×40; D: original magnification, ×100; haematoxylin and eosin). Immunohistochemistry using antisera raised against JC virus VP-1 demonstrates expression of the capoid protein VP-1 in the intranuclear viral inclusions of oligodendrocytes (E: original magnification, ×100) and in the nuclei of transformed astrocytes (F: arrows; original magnification, ×40).

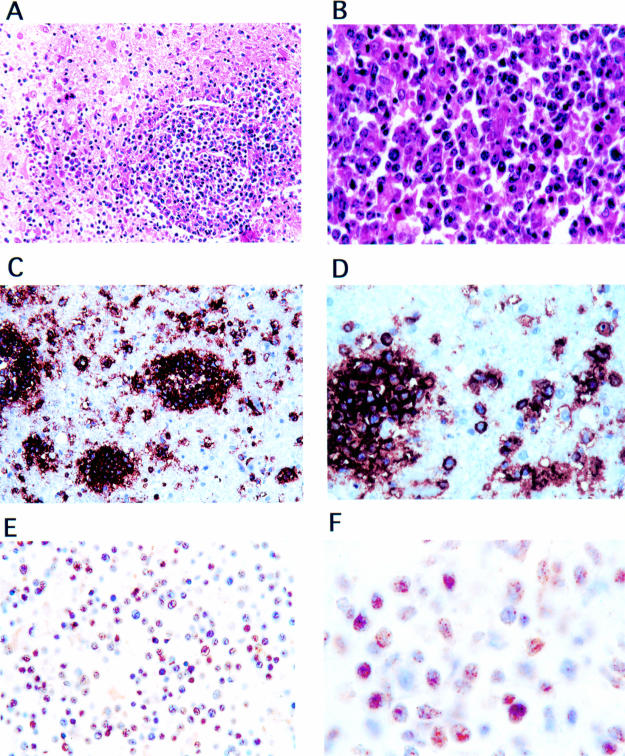

Sections from the basal ganglia revealed a highly cellular neoplasm, characterised by a homogenous population of small round cells with pleomorphic nuclei, which diffusely infiltrated the surrounding tissue (fig 3A, B ▶). Some mitotic figures were present. There were also small necrotic patches within the neoplasm. In the periphery of the tumour, the neoplastic cells had a perivascular concentric distribution and formed collars around blood vessels. Immunohistochemical examination using monoclonal antibodies specific for B cell surface antigens CD20 and CD79α showed that this neoplasm was of B cell origin (fig 3C, D ▶). According to the Working Formulation and latest World Health Organisation classification of tumours of the CNS,6 this neoplasm was classed as a diffuse large cell immunoblastic lymphoma. Because numerous studies have detected JCV within B cells (reviewed by Gallia et al),7 we next investigated the expression of JCV in the PCNS-L. As shown in fig 3E, F ▶, JCV T antigen was expressed in the nuclei of the neoplastic lymphocytes, with approximately 60% of the tumour cells being immunopositive for JCV T antigen.

Figure 3.

Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neoplastic cells have an angiocentric pattern, forming collars around blood vessels (A; original magnification, ×20; haematoxylin and eosin). At higher magnification the neoplastic cells are round with big nuclei and moderate eosinophilic cytoplasm (B; original magnification, ×100; haematoxylin and eosin). Immunohistochemical staining with anti-CD20 and anti-CD79α antibodies shows intense cytoplasmic and membrane associated reactivity in the neoplastic perivascular cells (C; original magnification, ×20; D, original magnification, ×100). Immunohistochemical staining with an antibody detecting JC virus T antigen shows expression in the nuclei of approximately 60% of the neoplastic lymphocytes (E; original magnification, ×40; F; original magnification, ×100).

Other notable pathological findings included AIDS cardiomyopathy, focal pulmonary fibrosis, candida septicaemia with multiple abscesses in the kidneys, heart, lungs, and brain, and secondary testicular atrophy, Sertoli cell only.

Discussion

CNS dysfunction is a prominent feature in patients with AIDS. Involvement of the CNS occurs clinically in approximately 30–40% of patients with AIDS,8–11 and postmortem examination reveals neuropathological abnormalities in up to 80–90% of patients.12–15 In addition to neurological disease caused by direct infection, the CNS of individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is susceptible to a unique constellation of opportunistic infections and neoplasms. Moreover, multiple CNS infections and neoplasms are reported to occur in between 10% and 15% of patients with AIDS.16,17 We describe a patient with AIDS and concomitant PML and PCNS-L. Moreover, we demonstrate the expression of the early viral protein, T antigen, within the nuclei of the neoplastic lymphocytes.

The concomitant occurrence of PML and PCNS-L in patients with and without AIDS is a relatively rare event. Table 1 ▶ summarises the reported co-occurrences of these two CNS diseases. There are several reports describing the co-occurrence of these two diseases in patients without AIDS.21a,22–25 Davies et al reported a patient with PML and a small granulomatous lesion consisting of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and large binucleate cells in the frontal white matter.25 A similar cellular infiltrate was present around many intracerebral blood vessels and leptomeninges. The authors considered these lesions as possible evidence of Hodgkin's disease or other reticulosis limited to the CNS. The description of the granulomatous lesion is consistent with PCNS-L. GiaRusso and Koeppen24 described a small PCNS-L in a patient with atypical progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy. The PCNS-L in this case was thought to arise directly within the foci of demyelination. Concomitant PML and PCNS-L have also been reported in patients treated with immunosuppressive agents after renal transplantation.22,23 In addition to these non-AIDS associated cases, several larger studies have reported the co-occurrence of these two CNS diseases in the background of AIDS.5,18–21

Table 1.

Association of PML and primary CNS lymphomas

| Patient | Underlying disease | CNS lymphoma reported | Other neuropathological features | Ref |

| 33 M | AIDS | B cell immunoblastic lymphoma | PML | Our study |

| Candida encephalitis | ||||

| NR | AIDS | NR | PML | Berger et al (1998)5 |

| NR | AIDS | NR | PML | Martinez et al (1995)18 |

| NR | AIDS | NR | PML | Martinez et al (1995)18 |

| HIV related encephalopathy | ||||

| 44 M | AIDS | Large cell lymphoma | PML | Morgello (1992)19 |

| CMV | ||||

| 56 M | AIDS | Large cell lymphoma | PML | Morgello et al (1990)20 |

| CMV encephalitis | ||||

| 36 | AIDS | B cell immunoblastic sarcoma | PML | Loureiro et al (1988)21 |

| Toxoplasma | ||||

| CMV | ||||

| 46 M | NR | Malignant lymphoma | PML (atypical) | Liberski et al (1982)21a |

| 68 F | Immunosuppression secondary to renal transplant | Histiocytic lymphoma | PML | Ho et al (1980)22 |

| 53 M | Immunosuppression secondary to renal transplant | Reticulum cell sarcoma | PML | Egan et al (1980)23 |

| 82 M | CLL | Immunoblastic sarcoma (reticulum cell sarcoma) | PML (atypical) | GiaRusso and Koeppen (1978)24 |

| 41 F | NR | ? Hodgkin's disease | PML | Davies et al (1973)25 |

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CNS, central nervous system; F, female; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; M, male; PML, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; NR, not reported; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

The relatively low frequency with which each disease occurs in AIDS—5% for PML and 2% for PCNS-L—makes it difficult to evaluate any pathogenetic relation between JCV, PML, and PCNS-L. This issue is further clouded by the fact that many CNS lymphomas remain clinically occult and are only detected at necropsy, when performed. In fact, 40–45% of tissue diagnoses of AIDS related PCNS-L are made at necropsy.15,26 Nonetheless, several observations about the biology of JCV warrant the investigation of a participatory role of this virus, directly or indirectly, in the formation of PCNS-L.

The high JCV seroconversion coupled with the selective emergence of PML in immunocompromised individuals indicates that JCV establishes a latent infection in immunocompetent individuals and becomes reactivated upon immune suppression. Many studies have demonstrated that JCV can infect lymphocytes, particularly B cells (reviewed by Gallia et al).7 Moreover, JCV positive lymphocytes have been detected within the CNS of patients with PML.27,28 Our current findings extend these initial observations, demonstrating expression of JCV T antigen within the nuclei of a primary CNS B cell lymphoma.

Another noteworthy feature of JCV is its oncogenic potential (reviewed in Gallia et al).29 JCV can transform various cells in vitro and cause neuroectodermal tumours in rodents and non-human primates. In addition, mice transgenic for the large tumour antigen of JCV develop dysmyelination as well as neuroectodermal tumours. Furthermore, JCV DNA and T antigen have recently been detected in human medulloblastomas.30,31 Given the existence of JCV in B cells, coupled with its oncogenic potential, it is tempting to envision a participatory role for JCV in B cell lymphomas. This is particularly interesting in light of observations indicating that JCV is associated with lymphocytes that contain multiple chromosome-type aberrations.32,33

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of AIDS related PCNS-L, with between 50% and 100% of AIDS related CNS lymphomas containing various EBV sequences.19,34,36 The existence of EBV negative PCNS-L suggests that other factors may be involved in the pathogenesis of at least some AIDS related PCNS-L cases and, recently, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) has been detected in CNS lymphomas from patients with and without AIDS.37 Together, these observations raise the possibility that several viruses may contribute to the development of PCNS-L.

JCV may indirectly influence the development of PCNS-L. Morgello et al reported an increased incidence of viral CNS infections in patients with AIDS and CNS lymphomas, suggesting that viral infection might play a role in the pathogenesis of CNS lymphoma in the immunocompromised individual.20 Although PML was only detected in one of 15 patients with primary CNS lymphoma, and that patient also had CMV encephalitis, perhaps several CNS viral infections can provide an initiating event for the development of PCNS-L in the immunocompromised patient.

In this report, we describe the co-occurrence of PML and PCNS-L in a patient with AIDS and demonstrate the presence of T antigen within the nuclei of the neoplastic lymphocytes. Although our study is limited to one case report, our findings provide evidence for a possible association of JCV with primary B cell lymphomas. Moreover, although the expression of JCV protein in CNS lymphomas may not establish a causal relation, our observations, along with the transforming ability of JCV, invite future studies to evaluate the participatory role JCV may play in the pathogenesis of PCNS-L.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr B Fenderson for assistance in retrieving some of the patient records, S Enam for assistance with immunohistochemistry, Drs S Morgello and J Martinez for helpful suggestions, and Ms C Schriver for editorial assistance. This work was supported by grants from the NIH awarded to KK. Dr G Gallia's current address is: Department of Neurosurgery, John Hopkin's University Hospital, Baltimore, USA.

References

- 1.Major EO, Amemiya K, Tornatore CS, et al. Pathogenesis and molecular biology of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, the JC virus-induced demyelinating disease of the human brain. Clin Microbiol Rev 1992;5:49–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padgett BL, Walker DL. Prevalence of antibodies in human sera against JC virus, an isolate from a case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis 1973;127:467–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taguchi F, Kajioka J, Miyamura T. Prevalence rate and age of acquisition of antibodies against JC virus and BK virus in human sera. Microbiol Immunol 1982;26:1057–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger JR, Concha M. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: the evolution of a disease once considered rare. J NeuroVirol 1995;5:5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger JR, Pall L, Lanska D, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with HIV infection. J Neurovirol 1998;4:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleihues P, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. The new WHO classification of brain tumors. Brain Pathol 1993;3:255–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallia GL, Houff SA, Major EO, et al. JC virus infection of lymphocytes revisited. J Infect Dis 1997;176:1603–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Britton CB, Miller JR. Neurological complications in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Neurol Clin 1984;2:315–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koppel BS, Wormser GP, Tuchman AJ, et al. Central nervous system involvement in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Acta Neurol Scand 1985;71:337–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy RM, Bredesen DE, Rosenblum ML. Neurological manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): experience at UCSF and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 1985;62:475–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snider WD, Simpson DM, Nielsen S, et al. Neurological complications of acquired immune deficiency syndrome: analysis of 50 patients. Ann Neurol 1983;14:403–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lantos PL, McLaughlin JE, Scholtz CL, et al. Neuropathology of the brain in HIV infection. Lancet 1989;i:309–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moskowitz LB, Hensley GT, Chan JC, et al. The neuropathology of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1984;108:867–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petito CK, Cho ES, Lemann W, et al. Neuropathology of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): an autopsy review. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1986;45:635–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkes MS, Fortin AH, Felix JC, et al. Value of necropsy in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Lancet 1988;ii:85–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chimelli L, Rosemberg S, Hahn MD, et al. Pathology of the central nervous system in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV): a report of 252 autopsy cases from Brazil. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 1992;18:478–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang W, Miklossy J, Deruaz JP, et al. Neuropathology of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS): a report of 135 consecutive autopsy cases from Switzerland. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1989;77:379–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez AJ, Sell M, Mitrovics T, et al. The neuropathology and epidemiology of AIDS. A Berlin experience. A review of 200 cases. Pathol Res Pract 1995;191:427–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgello S. Epstein-Barr and human immunodeficiency viruses in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related primary central nervous system lymphoma. Am J Pathol 1992;141:441–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgello S, Petito CK, Mouradian JA. Central nervous system lymphoma in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Neuropathol 1990;9:205–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loureiro C, Gill PS, Meyer PR, et al. Autopsy findings in AIDS-related lymphoma. Cancer 1988;62:735–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Liberski PP, Alwasiak J, Wegrzyn Z. Atypical progressive mulifocal leucoencephalopathy and primary cerebral lymphoma. Neuropatologia Polska 1982;20:413–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho KC, Garancis JC, Paegle RD, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and malignant lymphoma of the brain in a patient with immunosuppressive therapy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1980;52:81–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egan JD, Ring BL, Reding MJ, et al. Reticulum cell sarcoma and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy following renal transplantation. Transplantation 1980;29:84–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.GiaRusso MH, Koeppen AH. Atypical progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and primary cerebral malignant lymphoma. J Neurol Sci 1978;35:391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davies JA, Hughes JT, Oppenheimer DR. Richardson's disease (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy). Q J Med l973;42:481–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.So Y, Beckstead JH, Davis RL. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in acquired immune deficiency syndrome: a clinical and pathological study. Ann Neurol 1986;20:566–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houff SA, Mijor EO, Katz DA, et al. Involvement of JC virus-infected mononuclear cells from bone marrow and spleen in the pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 1988;318:301–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Major EO, Amemiya K, Elder G, et al. Glial cells of the human developing brain and B cells of the immune system share a common DNA binding factor for recognition of the regulatory sequences of the human polyomavirus JCV. J Neurosci Res 1990;27:461–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallia GL, Gordon J, Khalili K. Tumor pathogenesis of human neurotropic JC virus in the CNS. J Neurovirol 1998;4:175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalili K, Krynska B, DelValle L, et al. Medulloblastomas and the human neurotropic polyomavirus JC virus. Lancet 1999;353:1152–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krynska B, DelValle L, Croul S, et al. Detection of human neurotropic JC virus DNA sequence and expression of the viral oncogenic protein in pediatric medulloblastomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:11519–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lazutka JR, Neel JV, Major EO, et al. High titers of antibodies to two human polyomaviruses, JCV and BKV, correlate with increased frequency of chromosomal damage in human lymphocytes. Cancer Lett 1996;109:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neel JV, Major EO, Awa AA, et al. Hypothesis: “rogue-cell”-type chromosomal damage in lymphocytes is associated with infection with the JC human polyoma virus and has implications for oncogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:2690–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aboody-Guterman KS, Hair LS, Morgello S. Epstein-Barr virus and AIDS-related primary central nervous system lymphoma. Clin Neuropathol 1996;15:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacMahon EME, Glass JD, Hayward SD, et al. Epstein-Barr virus in AIDS-related primary central nervous system lymphoma. Lancet 1991;338:969–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meeker T, Shiramizu B, Kaplan L, et al. Evidence for molecular subtypes of HIV-associated lymphoma: division into peripheral monoclonal, polyclonal and central nervous system lymphoma. AIDS 1991;5:669–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corboy JR, Garl PJ, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Human herpesvirus 8 DNA in CNS lymphomas from patients with and without AIDS. Neurology 1998;50:335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]