ABSTRACT

Background

Although some guidelines recommend Renal denervation (RDN) as an alternative to anti‐HTN medications, there are concerns about its efficacy and safety. We aimed to evaluate the benefits and harms of RDN in a systematic review and meta‐analysis of sham‐controlled randomized clinical trials (RCT).

Methods

Databases were searched until September 10th, 2024, to identify RCTs evaluating RDN for treating URH versus sham control. The primary outcomes were the change in office and ambulatory 24‐h systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Secondary outcomes were changes in daytime and nighttime SBP and DBP, home BP, number of anti‐HTN drugs, and related complications. Mean differences (MD) and relative risks (RR) described the effects of RDN on BP and complications, respectively, using random effects meta‐analyses. GRADE methodology was used to assess the certainty of evidence (COE).

Results

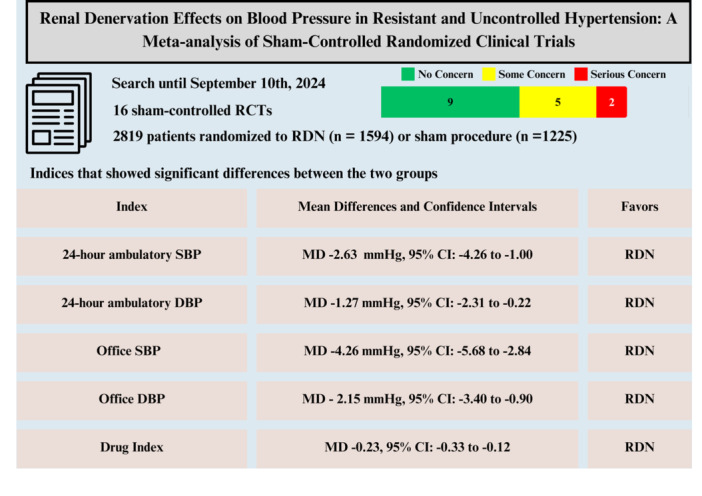

We found 16 included sham‐controlled RCTs [RDN (n = 1594) vs. sham (n = 1225)]. RDN significantly reduced office SBP (MD −4.26 mmHg, 95% CI: −5.68 to −2.84), 24 h ambulatory SBP (MD −2.63 mmHg), office DBP (MD −2.15 mmHg), 24‐h ambulatory DBP (MD −1.27 mmHg), and daytime SBP and DBP (MD −3.29 and 2.97 mmHg), compared to the sham. The rate of severe complications was low in both groups (0%–2%). The heterogeneity was high among most indices, and CoE was very low for most outcomes.

Conclusion

RDN significantly reduced several SBP and DBP outcomes versus sham without significantly increasing complications. This makes RDN a potentially effective alternative to medications in URH.

Keywords: cardiovascular events, meta‐analysis, renal denervation, resistant hypertension, sham‐controlled

Renal denervation (RDN) holds great promise as a treatment for lowering blood pressure in patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension. It demonstrates significant improvements in both office and ambulatory blood pressure measurements. The procedure is generally safe and effective, with no notable rise in adverse events. Moving forward, future studies should prioritize randomized clinic trials involving diverse populations to improve the applicability of results across different demographics.

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin‐converting enzyme

- ACM

all‐cause mortality

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- AMBP

ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

- anti‐HTN

antihypertensive

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

blood pressure

- CENTRAL

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

- CI

confidence interval

- COE

certainty of evidence

- CVA

cerebrovascular accidents

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- DMII

diabetes mellitus type II

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESC

European Society of Cardiology

- ESRD

end‐stage renal disease

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

- HAF

hospitalization for atrial fibrillation

- HHF

hospitalization for heart failure

- HTN

hypertension

- IQR

interquartile range

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular events

- MD

mean difference

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- RCT

randomized clinical trial

- RDN

renal denervation

- REML

restricted maximum likelihood

- RoB 2

risk of bias in randomized trials (Version 2)

- RR

relative risk

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- TRH

treatment‐resistant hypertension

- UCH

uncontrolled hypertension

- URH

uncontrolled resistant hypertension

1. Introduction

Hypertension (HTN) is a main risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), playing a fundamental role in almost one‐fifth of deaths in 2019 [1, 2]. Despite improvement in the pharmacologic treatment of HTN, a substantial percentage of patients have uncontrolled HTN (medicated by two drugs) or drug‐resistant HTN (medicated by three or more drugs, including diuretics). The main causes of these conditions are determined to be nonadherence to medications and insufficient or inappropriate selection of drugs [3]. One of the contributing factors in the development of resistant HTN is sympathetic nerve hyperactivity, especially in obese patients [4]. One of the modern methods of treating HTN is based on deactivating these nerves, a minimally invasive percutaneous procedure called renal denervation (RDN) [5]. Specific types of RDN have been approved by recent guidelines and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), mentioned as a supplementary or alternative treatment for resistant HTN [6, 7]. However, absolute indications of RDN for treating HTN have not been proposed [8].

Based on the 2023 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, RDN can be considered as an option in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) > 40 mL/min/1.73 m2 who have uncontrolled blood pressure (BP) despite the use of antihypertensive drug (anti‐HTN) combination therapy [9]. RDN is becoming an alternative treatment for patients whose BP cannot be controlled with anti‐HTN medications (resistant HTN). Moreover, previous studies have shown that those with poor medication compliance would benefit from this procedure, considering the decreased or resolved need to take routine drugs after this procedure [10, 11].

Although previous meta‐analyses that investigated the effectiveness and the safety of RDN for the treatment of resistant and uncontrolled and a subgroup analysis of only sham‐controlled trials consistently showed that RDN reduced office and 24‐h SBP [3, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14], there are still unanswered questions. The range of changes differs based on the systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressures (DBP), up to 60 mmHg in SBPs and 40 mmHg in DBPs. One of these dilemmas is the superiority of various types of RDN. Three main types of RDN (radiofrequency (RF), ultrasound (US), and alcohol‐mediated denervation) have been evaluated in several RCTs during recent years. Still, the optimal method in various subgroups of patients has yet to be determined [15]. Another reason for conducting this analysis is that, although previous meta‐analyses have been performed, methodological differences between the systematic reviews and the trials included make it challenging to draw generalizable conclusions. In addition, three significant recent trials—TARGET BPI [16], SMART [17], and the Iberis‐HTN Trial by Jiang and colleagues [18]—were not included in two of the most recent meta‐analyses in this field [14, 19]. Hence, we performed a comprehensive meta‐analysis of randomized, sham‐controlled clinical trials investigating the beneficial and harmful effects of RDN on BP across different devices.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This systematic review and meta‐analysis adhered to the PRISMA guidelines [20]. The review protocol, with the registration number CRD42024546447, was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were considered for inclusion if they satisfied the following criteria: (1) RCTs evaluating any RDN versus a sham procedure in adults aged 18 years or older with resistant HTN; (2) studies providing data SBP and DBP; and (3) studies published in the English language. The exclusion criteria encompassed nonrandomized studies, observational studies, case reports, review articles, editorials, and studies that did not include a sham procedure as a control.

2.3. Study Searches

A thorough literature search was performed using PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from their inception to July 1st, 2024. The search strategy incorporated terms related to RDN, treatment‐resistant HTN (TRH), resistant and uncontrolled HTN, and randomized controlled trials. The detailed search strategies are available in Supporting Information S2: Table 1. Additionally, reference lists of included articles and relevant reviews were manually screened to identify further studies.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Management

Duplicate records were identified and removed using the Rayyan web application, facilitating an efficient and accurate screening process. Rayyan was also used to screen titles and abstracts, allowing independent reviewers (S.H. and E.S.) to classify studies as included, excluded, or marked for further consideration [21]. Full‐text articles of potentially relevant studies were assessed for inclusion. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or consultation with a third reviewer (R.N.).

2.5. Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed using a standardized, predetermined form in Excel. Extracted data included study characteristics (author, year of publication, sample size, follow‐up duration), patient demographics (age, gender, baseline BP, body mass index [BMI]), intervention details (type of RDN, comparator), and outcomes per arm (RDN or sham).

2.6. Outcomes and Definitions

Primary outcomes were office and 24‐h ambulatory SBP and DBP. Secondary outcomes include daytime, nighttime, and home SBP and DBP. Moreover, adverse events such as hypertensive and hypotensive emergencies, acute kidney injury (AKI) (sudden rise in creatinine > 50%), hospitalization for heart failure (HHF), hospitalization for atrial fibrillation (HAF), all‐cause mortality (ACM), adverse event rate, severe adverse event rate, severe cerebrovascular adverse event rate, new end‐stage renal disease (ESRD), embolic events accompanied by end‐organ damage, hospitalization for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (cerebrovascular accidents (CVA), myocardial infarction (MI)), new renal artery stenosis > 70%, major vascular complication (renal artery perforation or dissection). Moreover, the changes in the number of anti‐HTN drugs and anti‐HTN drug index were measured. Definitions of resistant HTN and clinical outcomes followed standard criteria described in the included studies.

-

–

Resistant Hypertension: It is defined as above‐goal elevated BP in patients despite the concurrent use of ≥ 3 anti‐HTN medications from various classes, commonly including a long‐acting calcium channel blocker (CCB), a blocker of the renin–angiotensin system (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker), and a diuretic [22].

-

–

Uncontrolled Hypertension: A BP above 140/90, which might be caused secondary to poor adherence or an inadequate treatment regimen, as well as those with true treatment resistance [22].

-

–

Drug Index: It is constructed as Class N (number of classes of antihypertensive drugs) × (sum of doses) [23].

2.7. Risk of Bias Assessment

Two independent authors (H.T. and M.T.) evaluated the risk of bias in individual RCTs using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials (RoB 2) [24]. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by consensus. RoB 2 assessments addressed five domains, including the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of the reported results. Each domain and each RCT was then categorized as having a low, high, or unclear risk of bias [24].

2.8. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with the R software [25] (R for Windows, version 4.1.3, Vienna, Austria) and R Studio version 1.1.463 (Posit PBC, Boston, MA, USA), utilizing the tidyverse [26] and meta [27] packages.

Pooled RDN effects versus medical treatment on BP outcomes were expressed as mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI); binary outcomes were expressed as relative risks (RR) with 95% CI. The between‐study variance was described with the τ 2 estimate. Random‐effect models were used to account for variability across studies. When studies reported medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), the method developed by Lou and colleagues [28] and Wan and colleagues [29] was used to calculate the mean and SD. If the SD of the mean change was not reported, it was calculated using the formula [30]:

Meta‐analyses were performed using a random‐effects model with restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochrane's Q statistic and I 2 statistic [31], with I 2 values classified as low (< 25%), moderate (25%–50%), or high (> 50%) heterogeneity. Visual and statistical assessments for publication bias were conducted using funnel plots and Begg's and Egger's tests [32].

Subgroup analyses by device type (alcohol, RF, and US) and medication status (on vs. off) were conducted. A p for interaction < 0.10 meant a significant subgroup effect for an outcome. Sensitivity analyses were performed using three methods: (1) by using a fixed‐effect model, (2) by using a leave‐one‐out sensitivity analysis, and (3) by excluding the studies that had < 100 participants in each arm. Meta‐regression analysis was conducted for the outcomes of 24‐h SBP and DBP with variables of age, BMI, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), male proportion, baseline mean SBP, and follow‐up duration. Certainty of evidence and strength of recommendations were performed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Guidelines. A summary of COE was performed based on the evaluation of the pooled studies' number for each index and their design, indirectness, imprecision, and the number of included patients.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

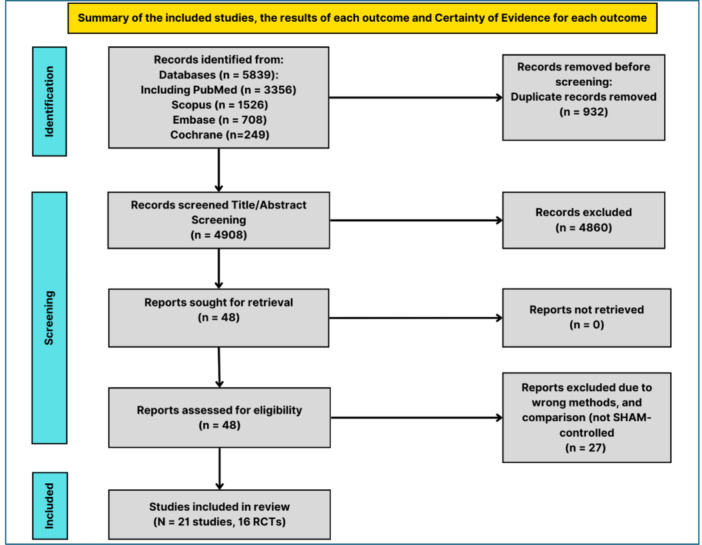

A comprehensive literature search identified a total of 5839 records from various databases, including PubMed (n = 3356), Scopus (n = 1526), Embase (n = 708), and Cochrane CENTRAL (n = 249). After excluding 932 duplicates, 4907 unique records were screened based on titles and abstracts. During this initial screening, 4860 records were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Consequently, 47 full‐text articles were retrieved for a detailed evaluation. After further assessment, 25 articles were excluded due to not aligning with the required methods, population, or intervention/comparison criteria. Ultimately, 21 reports from 16 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in the systematic review and meta‐analysis (Figure 1) [16, 17, 18, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of included studies.

The selected studies comprised a total of 2819 participants (RDN: 1594 and sham procedure: 1225), with sample sizes ranging from 51 to 515 participants per study. Follow‐up periods were varied, with the majority ranging from 2 to 12 months, although some extended up to 36 months. Participants' demographics showed a broad range of ages, with the mean age of participants spanning from 44.5 to 65.5 years. The mean BMI across studies ranged from 28.2 to 34.2 kg/m2. The proportion of male participants also varied; some studies had as few as 18% male participants, while others had up to 95.5%. The included studies also reported diverse distributions of diabetes mellitus (DMII) prevalence and the number of anti‐HTN medications taken by participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primary characteristics of included trials.

| Trials, author/acronym, year (reference) | NCT | Country | Device | Energy source | Scape criteria | FU (M) | Number | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RD | Sham | |||||||

| 1. Symplicity HTN‐3, Bhatt, 2014 [33] | NCT01418261 | USA | Symplicity renal‐denervation catheter (Medtronic) | RF | No escape criteria are defined in this trial | 6 | 364 | 171 |

| 2. Symplicity FLEX, Desch, 2015 [34] | NCT01656096 | Germany | Symplicity Flex catheter (Medtronic) | RF‐RDN | No escape criteria are defined in this trial | 6 | 35 | 36 |

| 3. ReSET, Mathiassen, 2016 [35] | No NCT | Denmark | Simplicity renal denervation catheter (Medtronic) | RF‐RDN | No escape criteria are defined in this trial | 6 | 36 | 33 |

| 4. Wave IV, Schmieder, 2018 [36] | No NCT | Czech Republic, Germany, New Zealand, Poland, UK | Kona Surround Sound system | US‐RDN | No escape criteria are defined in this trial | 6 | 42 | 39 |

| 5. RADIANCE‐HTN SOLO, Azizi, 2018 [37] | NCT02649426 | USA, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, UK | Paradise RDN system (ReCor Medical) | US‐RDN | OBP > 180/110 mmHg or HBP > 170/105 mmHg | 2 | 74 | 72 |

| 5. RADIANCE‐HTN SOLO, Azizi, 2019 [38] | 6 | |||||||

| 5. RADIANCE‐HTN SOLO, Azizi, 2019 [39] | 12 | |||||||

| 6. SPYRAL HTN‐OFF MED Pivotal, Bohm, 2020 [50] | NCT02439749 | Australia, Austria, Canada, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Japan, UK, USA | Symplicity Spyral multielectrode catheter (Medtronic, Mountain View, CA) or Symplicity G3 radiofrequency generator (Medtronic) | RF‐RDN | OBP > 180/110 mmHg or HBP > 170/105 mmHg | 3 | 166 | 165 |

| 7. REINFORCE, Weber, 2020 [40] | NCT02392351 | USA | Vessix Renal Denervation system | RF‐RDN | Office SBP > 180 mmHg at two consecutive visits within 3 days | 2 | 34 | 17 |

| 8. RADIANCE‐HTN TRIO, Azizi, 2021 [41] | NCT02649426 | USA, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Poland, and UK | Paradise RDN system (ReCor Medical) | US‐RDN | OBP > 180/110 mmHg or HBP > 170/105 mmHg | 2 | 69 | 67 |

| 8. RADIANCE‐HTN TRIO, Azizi, 2022 [42] | 6 | 69 | 67 | |||||

| 9. REQUIRE, Kario, 2021 [43] | NCT02918305 | Japan and S. Korea | Paradise RDN system (ReCor Medical) | RF‐RDN | No escape criteria are defined in this trial | 3 | 72 | 71 |

| 10. Heradien 2022 [44] | NCT01990911 | South Africa | Symplicity Flex and Spyral | RF | 6 | 42 | 38 | |

| 11. TARGET BP OFF‐MED, Pathak, 2023 [45] | NCT03503773 | US, several European countries | Peregrine System Infusion Catheter (Ablative Solutions Inc) | Alcohol‐RDN | No escape criteria are defined in this trial | 2 | 50 | 56 |

| 12. RADIANCE II, Azizi, 2023 [46] | NCT03614260 | Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and UK | Paradise system (ReCor Medical, Inch Palo Alto, CA) | US‐RDN | OBP > 180/110 mmHg or HBP > 170/105 mmHg | 2 | 150 | 74 |

| 13. SPYRAL ON MED (expansion) Kandazari 2023 [49] | NCT02439775 | USA, Germany, Japan, UK, Australia, Austria, and Greece | Symplicity Spyral multielectrode catheter (Medtronic) or Symplicity G3 radio‐frequency generator (Medtronic) | RF‐RDN | OBP > 180/110 mmHg or HBP > 170/105 mmHg | 6 | 206 | 131 |

| 13. SPYRAL ON MED, Mahfoud (expansion) 2023 [47] | 24 | 34 | 17 | |||||

| 13. SPYRAL ON MED (expansion) Kario, 2022 [48] | 36 | 36 | 42 | |||||

| 14. TARGET BPI, Kandazari, 2024 [16] | NCT02910414 | USA | Peregrine | Alcohol | 6 | 145 | 146 | |

| 15. SMART, Wang, 2024 [17] | NCT02761811 | China | Catheter | RF | 6 | 109 | 110 | |

| 16. Iberis‐HTN Trial, Jiang, 2024 [18] | NCT02901704 | China | Multielectrode, unipolar Iberis RDN catheter and generator system (AngioCare, Shanghai, China) |

low‐level RF |

Symptomatic hypertension or SBP ≥ 180 mmHg or symptomatic hypotension or systolic BP | 6 | 107 | 110 |

Abbreviations: FU (M), follow‐up (months); HBP, home blood pressure; NCT, National Clinical Trial number; OBP, office blood pressure; RD, renal denervation; RF, radiofrequency; RF‐RDN, radiofrequency renal denervation; SBP, systolic blood pressure; US‐RDN, ultrasound renal denervation.

3.2. Quality Assessment of Included Trials

The quality assessment of the included articles was conducted using the risk of bias in randomized trials (RoB 2) [24]. Overall, five studies' evaluations revealed a high risk of bias, while two others were categorized as having some concerns about bias. Nine others showed a low risk of bias (Supporting Information S1: Figure 1).

3.3. Effects of RDN on Primary Outcomes

3.3.1. 24‐h Ambulatory Blood Pressures

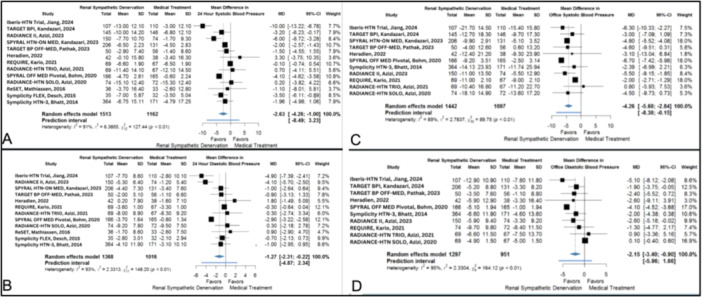

RDN significantly reduced 24‐h SBP (MD −2.30 mmHg, 95% CI: −3.53 to −1.07) (Figure 2A) and DBP (MD −1.21 mmHg, 95% CI: −2.18 to −0.23) compared to medical treatment (Figure 2B). Of the 11 trials pooled in the 24‐h SBP calculation, RADIANCE II (2023) had the most prominent difference between the two groups (MD −6.00 mmHg, 95% CI: −8.72 to −3.28), while four other studies revealed a statistically considerable difference between two categories, but the MD was lower. Ten studies were analyzed in the pooled data of 24‐h DBP; seven trials showed a more prominent decrease in the MD, and three showed an insignificantly higher reduction in this index in the control group. The heterogeneity among studies included in the pooled analyses of these two indices was high, showing I 2 of 90% for 24‐h SBP and I 2 of 93% for 24‐h DBP.

Figure 2.

Effect of RDN versus medical treatment on (A) 24‐h systolic blood pressure, (B) 24‐h diastolic blood pressure, (C) office systolic blood pressure, and (D) office diastolic blood pressure.

3.3.2. Office Blood Pressures

A similar pattern could be seen in the results of the office BP measurements, where RSD significantly reduced office SBP (MD −4.11 mmHg, 95% CI: −5.64 to −2.57) (Figure 2C) and office DBP (MD −1.85 mmHg, 95% CI: −3.15 to −0.55) (Figure 2D) in comparison with medical treatment. However, like 24‐h BPs, the included studies in both pooled analyses showed a high heterogeneity. Among nine studies included in the pooled analysis of office SBP, SPYRAL HTN‐OFF MED Pivotal (2020) demonstrated the most substantial reduction in the SBP (MD −6.70 mmHg, 95% CI: −7.42 to −5.98), while RADIANCE‐HTN TRIO (2022) was the only study which revealed the increased mean of SBP in the RDN group compared to the control group. However, the difference was not significant. Eight studies were included in the pooled analysis of office DBP; six showed a more substantial decrease in DBP, but only three showed significant differences. The measured I 2 for office SBP and DBP were 91% and 96%, respectively.

3.3.3. Effects of RDN on Secondary Outcomes

Among the secondary outcomes, the MD between the RDN and control group was insignificant in the pooled analysis of the night‐time BPs (Supporting Information S1: Figure 2), home BPs (Supporting Information S1: Figure 3), and daytime DBP RDN (Supporting Information S1: Figure 4B). However, this intervention significantly reduced daytime SBP versus medical treatment (MD −3.29 mmHg, 95% CI: −5.43 to −1.15) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 4A). The heterogeneity between studies was significant among the nine included trials in this study (I 2 = 80%) (Supporting Information S2: Table 2).

Although there was no significant difference in the reduction of the number of anti‐HTN medications between RDN and medical treatment (MD −0.08, 95% CI: −0.25 to 0.10) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 5), the drug index pooled analysis showed a significantly lower MD in the RDN group (MD = −0.23, 95% CI: −0.33 to −0.12) (Figure 3 and Supporting Information S2: Tables 3). Six studies included in this index revealed insignificant heterogeneity (I 2 = 38%).

Figure 3.

Effect of renal denervation versus medical treatment on (A) the drug index.

The pooled analysis of the adverse outcomes, including embolic event which caused end‐organ damage, major access site complications, procedure‐related pain > 2 days, severe cerebrovascular adverse event rate, AKI, ACM, major vascular complications, HTN emergency, hypotension emergency, CVA, MI, creatinine rise, renal artery stenosis, percutaneous coronary intervention, HHF and HAF showed an insignificant rate (Supporting Information S2: Table 4) and also a negligible difference between risk ratios (RR) of RDN and medication group. The incidence of HTN and hypotension emergencies also showed insignificant rates and insignificant differences (Supporting Information S1: Figure 6).

3.4. Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

3.4.1. The 24‐h Ambulatory Mean of Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressures

Fixed‐effect and random‐effect (leave‐one‐out) methods were employed for sensitivity analyses. The results from the pooled data for the random‐effect (leave‐one‐out) approach demonstrated a significant difference between groups in 24‐h SBP, with considerable heterogeneity (MD: −2.42 mmHg, 95% CI: −2.74 to −2.11, p < 0.01) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 7). Using a random‐effects model, the MD in larger studies (sample size > 100) was even larger (MD of −3.41 mmHg, 95% CI: −5.10 to −1.72) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 8). The subgroup analysis of the 24‐h SBP outcomes based on device type and medication status revealed significant differences between the intervention and control groups except for the US‐based device group (Supporting Information S1: Figures 9 and 10).

The fixed effect model showed a significant reduction of 24 h DBP (MD; 1.63 mmHg (95% CI: −1.84 to −1.41)) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 11A), and the sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out method resulted in a pooled MD of −1.27 mmHg (95% CI: −2.31 to −0.22, p = 0.02) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 11B). In larger studies, the random‐effects model yielded a MD of −2.36 mmHg (95% CI: −3.75 to −0.97) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 12). The subgroup analysis of the 24‐h SDP outcomes based on the device type and medication status revealed significant differences between intervention and control groups except for US and alcohol‐based devices groups (Supporting Information S1: Figures 13 and 14).

3.4.2. Office Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure

The fixed effect model showed a significant reduction of office SBP (MD: −4.45 mmHg (95% CI: −4.85 to −4.05)) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 15A), and the sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out method resulted in a pooled MD of −4.26 mmHg (95% CI: −5.68 to −2.84, p < 0.01) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 15B). In larger studies, the random‐effects model yielded a MD of −5.44 mmHg (95% CI: −6.93 to −3.95) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 16). The subgroup analysis by the type of device showed significant differences between the intervention and control groups in RF and US‐based devices (Supporting Information S1: Figure 17).

The fixed effect model showed a reduction in office DBP by 2.38 mmHg (95% CI: −2.68 to −2.07), with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 96%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 18A). Sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out method resulted in a pooled MD of −2.15 mmHg (95% CI: −3.40 to −0.90, p < 0.01) with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 96%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 18B). Additionally, a random‐effects model including large studies and a separate supplementary analysis with a reduced data set confirmed a similar significant reduction in office DBP, with a pooled MD of −2.95 mmHg (95% CI: −4.28 to −1.63) and moderate heterogeneity (I 2 = 66%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 19). The subgroup analysis by the type of device showed significant differences between the intervention and control groups in RF‐based methods and insignificant differences between groups in US‐based devices (Supporting Information S1: Figure 20).

3.4.3. Home Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure

The fixed effect model also showed a reduction of home SBP by 1.78 mmHg (95% CI: −2.38 to −1.19), with low heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 21A). Sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out method resulted in a pooled MD of −1.78 mmHg (95% CI: −2.38 to −1.19, p < 0.01) with no heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 21B). The fixed effect model also showed an increase of home DBP by 0.07 mmHg (95% CI: −0.29 to 0.42), with low heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 22A). Sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out method resulted in a pooled MD of 0.07 mmHg (95% CI: −0.29 to 0.42, p = 0.07) with no heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 22B).

3.4.4. Nighttime Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure

The fixed effect model showed a reduction in nighttime SBP by 2.01 mmHg (95% CI: −2.51 to −1.51), with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 90%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 23A). Sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out method resulted in a pooled MD of −2.14 mmHg (95% CI: −4.58 to 0.30, p = 0.19) with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 90%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 23B). The subgroup analysis by the type of device showed insignificant differences between the intervention and control groups in both RF‐ and US‐based devices (Supporting Information S1: Figure 24). The fixed effect model showed an increase in nighttime DBP by 0.28 mmHg (95% CI: −0.12 to 0.68), with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 86%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 25A). Sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out method resulted in a pooled MD of −0.81 mmHg (95% CI: −2.85 to 1.22, p = 0.43) with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 86%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 25B). Interestingly, the subgroup analysis by the type of device showed a significantly lower MD of DBP in the intervention group in RF‐based methods, while the differences between the intervention and control groups in the US‐based devices were insignificant (Supporting Information S1: Figure 26).

3.4.5. Daytime Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure

The fixed effect model reduced daytime SBP by 1.70 mmHg (95% CI: −2.13 to −1.26) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 27A). Sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out method resulted in a pooled MD of −3.29 mmHg (95% CI: −5.43 to −1.15, p < 0.01) with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 80%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 27B). The subgroup analysis by the type of device showed significant differences between the intervention and control groups in the RF‐ and the insignificant differences between the two groups in US‐based devices (Supporting Information S1: Figure 28). The fixed effect model showed a reduction in daytime DBP by 7.92 mmHg (95% CI: −8.24 to −7.59), with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 97%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 29A). Sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out method resulted in a pooled MD of −2.97 mmHg (95% CI: −5.64 to −0.30, p = 0.1) with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 97%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 29B). The subgroup analysis by the type of device showed significant differences between the intervention and control groups in the RF‐based and insignificant differences between the intervention and control groups in the US‐based devices (Supporting Information S1: Figure 30).

3.4.6. Antihypertensive Medications Number and Drug Index

The fixed effect model showed a reduction of the number of anti‐HTN medications by −0.06 (95% CI: −0.16 to 0.03) with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 70%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 31A). Sensitivity analyses further support these results, with a random effects model showing a MD of −0.08 (95% CI: −0.25 to 0.10, P:0.38) and similar heterogeneity (I 2 = 73%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 31B). Additionally, a random‐effects model, including large studies, showed a MD of −0.03 (95% CI: −0.38 to 0.32), with substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 89%, p < 0.01) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 32).

The fixed effect model showed a significant reduction in the drug index in the RDN group compared to the control group by an MD of −0.23 (95% CI: −0.33 to −0.12) with insignificant heterogeneity (I 2 = 38%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 33A). The random effects model, using the leave‐one‐out method, showed a statistically significant difference between the intervention and control group with an MD of −0.23 (95% CI: −0.33 to −0.12, p < 0.01) and similar heterogeneity (I 2 = 38%) (Supporting Information S1: Figure 33B). The comparison between random effect and fixed‐effect analysis revealed differences in some indices. This comparison highlights the variability and consistency in effect size estimates between the two meta‐analytical approaches, indicating that the nighttime results are statistically significant. All effects are MD between RDN and sham in mmHg (Supporting Information S2: Table 5).

Overall, only RF‐based devices demonstrated significant differences in 24‐h DBP, office DBP, and day SBP subgroup analysis (Supporting Information S1: Figures 13, 20, and 28). The subgroup analysis based on the on‐ and off‐med subgroups in 24‐h SBP and DBP showed that although the difference between both subgroups was significant, pooled MD of off‐med subgroup were more prominent than on‐med patients in both mentioned indices (Supporting Information S1: Figures 9 and 14).

3.4.7. Meta‐Regression and Publication Bias

The 24‐h SBP and DBP meta‐regression analyses showed nonsignificant trends for age, BMI, and the proportion of male patients, with wide CI (Supporting Information S1: Figure 34A–F). Significant associations were found for GFR, baseline mean SBP, and follow‐up time, with narrower CI and consistent data patterns (Supporting Information S1: Figure 34G–L).

The sham‐controlled design of some trials may have introduced bias, as it is unclear whether participants in the sham group were effectively blinded, potentially influencing the outcomes. However, a p value of 0.18 (Supporting Information S1: Figure 35) indicates no statistically significant evidence of asymmetry in evaluating the number of anti‐HTN medications. Therefore, publication bias is unlikely. Moreover, a time‐trend analysis of three trials with 2–12‐month follow‐ups showed that the MD of 24‐h AMBP had an overall increasing trend in systolic and diastolic indexes (Supporting Information S1: Figure 36).

3.5. Certainty of Evidence (COE)

Table 2 presents the GRADE summary of the findings table with COE assessments. Moreover, two independent assessors (P.E. and A.E). were invited to assess the certainty of evidence. Disagreements were referred to a third senior author (K.H.), who asked three researchers and a professional coauthor to the GRADE PRO platform to revise the process. We chose the seven most important indicators of the certainty of evidence. However, considering Cochrane's standards, 24‐h office SBP and DBO and changes in the number of anti‐HTN were categorized as very low certainty, and the drug index was classified as low certainty of evidence. The main causes of downgrading of COE were as follows: (1) studies that carried large weight for the overall effect estimate rated high risk of bias due to missed outcomes. (2) The rate of heterogeneity is very high. (3) Many studies have shown bias due to a high rate of missed outcomes and/or lack of appropriate concealment. (4) A lower number of studies report the index.

Table 2.

Certainty of evidence based on GRADE criteria has been determined for indices.

| Certainty assessment | No. of patients | Effect | Certainty | Importance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | RDN | SHAM‐controlled | Absolute (95% CI) | ||

| 24‐h systolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 13 | Randomized trials | Seriousa | Very seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1513 | 1162 | MD 2.63 mmHg lower (4.66 lower to 1 lower) |

⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

| 24‐h diastolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 12 | Randomized trials | Serious | Very seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1368 | 1016 | MD 1.27 mmHg lower (2.31 lower to 0.22 lower) |

⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

| Office systolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 11 | Randomized trials | Seriousa | Very seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1442 | 1097 | MD 4.26 mmHg lower (5.68 lower to 2.54 lower) |

⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

| Office diastolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 10 | Randomized trials | Seriousc | Very seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1297 | 951 | MD 2.15 mmHg lower (3.4 lower to 0.9 lower) |

⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

| Daytime systolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized trials | Serious | Very seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | None | 891 | 732 | MD 3.29 mmHg lower (5.43 lower to 1.15 lower) |

⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

| Daytime diastolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 7 | Randomized trials | Seriousd | Very seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | None | 433 | 345 | MD 2.97 mmHg lower (5.54 lower to 0.3 lower) |

⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

| Night systolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized trials | Seriousd | Very seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | None | 891 | 732 | MD 2.14 mmHg lower (4.58 lower to 30 higher) |

⊕◯◯◯ |

Important |

| Night diastolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 7 | Randomized trials | Seriousc, d | Seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | None | 433 | 345 | MD 0.81 mmHg lower (2.85 lower to 0.22 higher) |

⊕⊕◯◯ |

Important |

| Home diastolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 4 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 540 | 452 | MD 0.17 mmHg lower (2.14 lower to 1.8 higher) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

Important |

| Home systolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | not serious | None | 639 | 476 | MD 1.05 mmHg lower (3.34 lower to 1.24 higher) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

Important |

| Drug index | |||||||||||

| 6 | Randomized trials | Seriousd | Not serious | Not serious | Seriouse | None | 573 | 496 | MD 0.23 mmHg lower (0.33 lower to 0.12 lower) |

⊕⊕◯◯ |

Critical |

| Number of antihypertensive drugs | |||||||||||

| 10 | Randomized trials | Seriousa | Seriousb | Not serious | Seriouse | None | 1297 | 935 | MD 0.08 mmHg lower (0.25 lower to 0.1 lower) |

⊕◯◯◯ |

Critical |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference.

Studies that carried large weight for the overall effect estimate rated a high risk of bias due to missed outcomes.

The rate of heterogeneity is very high (I 2 > 75).

Many studies have shown bias due to a high rate of missed outcomes and/or lack of appropriate concealment.

It is reported by a lower number of studies.

The calculation of this index is based on subjective measures and patients' reports.

4. Discussion

This meta‐analysis represents the largest review of randomized, sham‐controlled trials evaluating RDN for TRH, encompassing 21 articles from 16 trials with 2819 patients. Our findings provide updated insights into the effectiveness of RDN in managing HTN. The analysis reveals that RDN significantly reduces office and 24‐h BP, including systolic and diastolic measures. However, the effect on home and nocturnal BP measurements was inconsistent. RDN significantly lowered 24‐h systolic BP and diastolic BP compared to medical treatment. These results indicate a substantial effect on BP reduction, although the heterogeneity among studies was high. Significant reductions were observed in office BP measurements, though again with high heterogeneity. For secondary outcomes, RDN showed a significant decrease in daytime systolic BP but no significant effect on nighttime BP or home BP measurements. The reduction in the number of anti‐HTN medications was not statistically significant, though the drug index analysis revealed a significant decrease. The adverse events associated with RDN were not significantly different from those in the control group, suggesting that RDN is a safe procedure. However, the high heterogeneity among studies and variability in BP measurement methods indicate the need for further research to refine the use of RDN in clinical practice.

The effectiveness of anti‐HTN treatments in reducing major cardiovascular events is often linked to their impact on ABPM. For example, Dolan and colleagues (2007) reported that reductions in ABPM SBP and nighttime DBP are associated with decreased cardiovascular mortality [51]. Similarly, Mancia and colleagues found that increased erratic variability in DBP was significantly associated with higher cardiovascular death risk [52]. Another trial demonstrated that a ≥ 5 mmHg decline in ABPM was linked to a significant reduction in MACE [53]. Our meta‐analysis supports these findings, showing significant decreases in ABPM with RDN. This aligns with Ogoyama and colleagues's recent meta‐analysis, which found RDN effective in reducing 24‐h SBP [10]. However, our results diverge from studies regarding the effect on daytime BP. While Ogoyama and colleagues [10] reported significant short‐term effects of RDN on daytime SBP, other studies did not find substantial differences [11, 49]. Our subgroup analysis indicates that radiofrequency‐based RDN showed significant differences in daytime BP, while US‐based treatments did not, highlighting the need to consider device type when evaluating RDN efficacy.

Beyond office BP measurements, nocturnal and home BP reductions in TRH (≥ 3 anti‐HTN medications, including at least one diuretic) are associated with fewer cardiovascular events and deaths [54, 55, 56, 57, 58]. For example, Kario and colleagues (2021) found that a nocturnal BP ≥ 120/70 mmHg is linked to a higher risk of heart failure [43]. ESH 2023 guidelines recommend monitoring BP variability, including home BP measurements, to assess treatment efficacy [9]. Our study found RDN significantly affects daytime SBP but not nighttime BP or home BP measurements. In addition, there is conflicting data regarding RDN's effect on daytime BP. Ogoyama and colleagues (2024) reported positive short‐term effects of RDN on daytime SBP [10], while another review, including nine RCTs, did not find significant differences between RDN and control groups [30]. Our study aligns with Ogoyama and colleagues's findings, showing a significant difference in daytime SBP but not DBP. Subgroup analysis indicated that radiofrequency‐based RDN was more effective in reducing daytime SBP than US‐based treatments, highlighting the impact of device type on treatment efficacy.

Our analysis indicates that RDN is effective regardless of concurrent anti‐HTN medication use, consistent with literature suggesting that RDN's benefits are not diminished by medication use [37, 59]. Therefore, it can be understood that taking anti‐HTN medications as a boosting strategy to enhance the decline of BP in patients who have undergone RDN has no negative impact on the therapeutic effect of this intervention [10]. Nonadherence to anti‐HTN medications, common in patients with resistant HTN, can worsen BP fluctuations and cardiovascular outcomes [60]. RDN offers a stable BP reduction, potentially providing a clinical advantage over medication alone by mitigating adherence issues. The dependency on anti‐HTN medications affects their concentration in the blood; the lower level might. Previous studies have suggested that RDN may reduce the average number of anti‐HTN medications and improve quality of life [17, 49, 59, 61]. However, our analysis did not find significant differences in medication numbers between RDN and control groups. More controlled studies are needed to clarify the impact of RDN on medication use. RDN's advantage in providing a stable BP reduction may improve quality of life by reducing medication side effects and concerns about adherence. RDN's long‐term impact on office BP and reduction in MACE incidence is promising [53, 62]. While many RCTs have evaluated MACE composites, direct assessments of RDN's impact on MACE incidence are limited. The Simplicity Registry reported a 35% reduction in MACE incidence with RDN [41]. Our study supports the effectiveness of RDN in reducing office BPs and suggests its potential for improving quality of life and reducing MACE.

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this meta‐analysis. First, the high heterogeneity observed across studies, particularly in 24‐h and office BP measurements, limits the generalization of results. The variation in study design, RDN devices, and patient populations may contribute to this heterogeneity. Second, not all studies consistently reported on secondary BP outcomes such as home, daytime, and nocturnal BP, leading to incomplete data for these parameters. Third, the trials included in this analysis had relatively short follow‐up periods, limiting insights into the long‐term efficacy and safety of RDN.

Additionally, the impact of anti‐HTN medications was not fully addressed, as variations in medication adherence among participants could have confounded the results. The strength of our meta‐analysis lies in its emphasis on sham‐controlled trials, which bolsters the reliability of our conclusions. By incorporating recent studies and applying the GRADE approach to evaluate the quality of evidence, we provide a strong foundation for informed clinical decision‐making.

4.2. Conclusion and Recommendations

In conclusion, RDN is a promising treatment for reducing BP in patients with TRH. It shows significant benefits in office and ambulatory BP measurements. The procedure appears safe and effective, with no substantial increase in adverse events. Further studies should prioritize conducting randomized controlled trials with diverse populations to enhance the generalizability of findings across various demographics. Additionally, research should focus on evaluating variations in study designs, particularly those with narrower CI favoring the intervention, to understand factors influencing outcomes. Finally, performing cost‐effectiveness analyses will provide critical insights to guide clinical decision‐making and resource allocation better. Therefore, future studies should focus on standardizing the measurement of BP outcomes, extending follow‐up durations, and rigorously addressing medication adherence to better define the role of RDN in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Hamidreza Soleimani, Babak Sattartabar, Bahar Parastooei, Reza Eshraghi, Ehsan Safaee, Roozbeh Nazari, Soroush Najdaghi, Pouya Ebrahimi, Kaveh Hosseini, and Sara Hobaby contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing the original draft, review, and editing. Ali Etemadi contributed to formal analysis, supervision, validation, methodology, review, and editing. Mehrdad Mahalleh contributed to data curation, formal analysis, software, validation, writing – review, and editing. Maryam Taheri contributed to data curation, formal analysis, software, validation, writing – review, and editing. Adrian V. Hernandez contributed to the original data curation, project administration, software, and writing draft, review and editing. Toshiki Kuno contributed to writing, reviewing, and editing. Homa Taheri contributed to providing resources for review and editing. Robert J. Siegel contributed to validation, review, and editing. Florian Rader and Mohammad Hossein Mandegar contributed to formal analysis, project administration, providing resources, supervision, validation, review, and editing. Behnam N. Tehrani contributed to methodology, supervision, validation, writing, review, and editing. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Acknowledgments

All authors serve in independent institutions responsible only for education and research. None of the authors is representative of or affiliated with a government agency.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supporting Information. Other data sets associated with the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Bakris G. L. and Weber M. A., “Overview of the Evolution of Hypertension: From Ancient Chinese Emperors to Today,” Hypertension 81, no. 4 (2024): 717–726, 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.124.21953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray C. J. L., Aravkin A. Y., Zheng P., et al., “Global Burden of 87 Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,” Lancet 396, no. 10258 (2020): 1223–1249, 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Silvinato A., Floriano I., and Bernardo W. M., “Renal Denervation by Radiofrequency in Patients With Hypertension: Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira 70, no. 4 (2024): e2023D704, 10.1590/1806-9282.2023d704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lohmeier T. E., Iliescu R., Liu B., Henegar J. R., Maric‐Bilkan C., and Irwin E. D., “Systemic and Renal‐Specific Sympathoinhibition in Obesity Hypertension,” Hypertension 59, no. 2 (2012): 331–338, 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.185074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rey‐García J. and Townsend R. R., “Renal Denervation: A Review,” American Journal of Kidney Diseases 80, no. 4 (2022): 527–535, 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration , Paradise Ultrasound Renal Denervation System‐P220023, 2024, https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/recently-approved-devices/paradise-ultrasound-renal-denervation-system-p220023.

- 7. Barbato E., Azizi M., Schmieder R. E., et al., “Renal Denervation in the Management of Hypertension in Adults. A Clinical Consensus Statement of the ESC Council on Hypertension and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI),” European Heart Journal 44, no. 15 (2023): 1313–1330, 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ramezani P., Amiri M., Bagheri A., and Naderi F., “Renal Denervation; A Promising Alternative for Medications to Ameliorate the Physical and Mental Burden of Hypertension, a Narrative Review,” Jundishapur Journal of Health Sciences 17, no. 1 (2024): e157051, 10.5812/jjhs-157051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mancia G., Kreutz R., Brunström M., et al., “2023 ESH Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension,” Journal of Hypertension 41, no. 12 (2023): 1874–2071, 10.1097/HJH.0000000000003480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ogoyama Y., Abe M., Okamura K., et al., “Effects of Renal Denervation on Blood Pressure in Patients With Hypertension: A Latest Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis of Randomized Sham‐Controlled Trials,” Hypertension Research 47, no. 10 (2024): 2745–2759, 10.1038/s41440-024-01739-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sobreira L. E. R., Bezerra F. B., Sano V. K. T., et al., “Efficacy and Safety of Radiofrequency‐Based Renal Denervation on Resistant Hypertensive Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis,” High Blood Pressure & Cardiovascular Prevention 31, no. 4 (2024): 329–340, 10.1007/s40292-024-00660-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Silverwatch J., Marti K. E., Phan M. T., et al., “Renal Denervation for Uncontrolled and Resistant Hypertension: Systematic Review and Network Meta‐Analysis of Randomized Trials,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 4 (2021): 782, 10.3390/jcm10040782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sesa‐Ashton G., Nolde J. M., Muente I., et al., “Long‐Term Blood Pressure Reductions Following Catheter‐Based Renal Denervation: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Hypertension 81, no. 6 (2024): e63–e70, 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.123.22314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sharp A., Sanderson A., Hansell N., et al., “Renal Denervation for Uncontrolled Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis Examining Multiple Subgroups,” Journal of Hypertension 42, no. 7 (2024): 1133–1144, https://journals.lww.com/jhypertension/fulltext/9900/renal_denervation_for_uncontrolled_hypertension__a.452.aspx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castillo Rodriguez B., Secemsky E. A., Swaminathan R. V., et al., “Opportunities and Limitations of Renal Denervation: Where Do We Stand?,” American Journal of Medicine 137, no. 8 (2024): 712–718, 10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kandzari D. E., Weber M. A., Pathak A., et al., “Effect of Alcohol‐Mediated Renal Denervation on Blood Pressure in the Presence of Antihypertensive Medications: Primary Results From the TARGET BP I Randomized Clinical Trial,” Circulation 149, no. 24 (2024): 1875–1884, 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.069291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang J., Yin Y., Lu C., et al., “Efficacy and Safety of Sympathetic Mapping and Ablation of Renal Nerves for the Treatment of Hypertension (SMART): 6‐Month Follow‐Up of a Randomised, Controlled Trial,” EClinicalMedicine 72 (2024): 102626, 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jiang X., Mahfoud F., Li W., et al., “Efficacy and Safety of Catheter‐Based Radiofrequency Renal Denervation in Chinese Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension: The Randomized, Sham‐Controlled, Multi‐Center Iberis‐HTN Trial,” Circulation 150, no. 20 (2024): 1588–1598, 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.069215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gonçalves O. R., Kelly F. A., Maia J. G., et al., “Assessing the Efficacy of Renal Denervation in Patients With Resistant Arterial Hypertension: Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Herz 50 (2024): 34–41, 10.1007/S00059-024-05268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., et al., “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews,” Systematic Reviews 10, no. 1 (2021): 89, 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., and Elmagarmid A., “Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews,” Systematic Reviews 5, no. 1 (2016): 210, 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carey R. M., Calhoun D. A., Bakris G. L., et al., “Resistant Hypertension: Detection, Evaluation, and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association,” Hypertension 72, no. 5 (2018): e53–e90, 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kandzari D. E., Hickey G. L., Pocock S. J., et al., “Prioritised Endpoints for Device‐Based Hypertension Trials: The Win Ratio Methodology,” EuroIntervention 16, no. 18 (2021): e1496–e1502, 10.4244/EIJ-D-20-01090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Higgins J. P. T., Altman D. G., Gotzsche P. C., et al., “The Cochrane Collaboration's Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials,” BMJ 343, no. oct18 2 (2011): d5928, 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. R Core Team , R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wickham H., Averick M., Bryan J., et al., “Welcome to the Tidyverse,” Journal of Open Source Software 4, no. 43 (2019): 1686. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Balduzzi S., Rücker G., and Schwarzer G., “How to Perform a Meta‐Analysis With R: A Practical Tutorial,” Evidence Based Mental Health 22, no. 4 (2019): 153–160, 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Luo D., Wan X., Liu J., and Tong T., “Optimally Estimating the Sample Mean From the Sample Size, Median, Mid‐Range, and/or Mid‐Quartile Range,” Statistical Methods in Medical Research 27, no. 6 (2018): 1785–1805, 10.1177/0962280216669183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wan X., Wang W., Liu J., and Tong T., “Estimating the Sample Mean and Standard Deviation From the Sample Size, Median, Range and/or Interquartile Range,” BMC Medical Research Methodology 14, no. 1 (2014): 135, 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fernandes A., David C., Pinto F. J., Costa J., Ferreira J. J., and Caldeira D., “The Effect of Catheter‐Based Sham Renal Denervation in Hypertension: Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 23, no. 1 (2023): 249, 10.1186/s12872-023-03269-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Higgins J. P. T., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., and Altman D. G., “Measuring Inconsistency in Meta‐Analyses,” BMJ 327, no. 7414 (2003): 557–560, 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kepes S., Wang W., and Cortina J. M., “Assessing Publication Bias: A 7‐Step User's Guide With Best‐Practice Recommendations,” Journal of Business and Psychology 38, no. 5 (2023): 957–982, 10.1007/s10869-022-09840-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhatt D. L., Kandzari D. E., and O'Neill W. W., “A Controlled Trial of Renal Denervation for Resistant Hypertension,” Journal of Vascular Surgery 60, no. 1 (2014): 266, 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Desch S., Okon T., Heinemann D., et al., “Randomized Sham‐Controlled Trial of Renal Sympathetic Denervation in Mild Resistant Hypertension,” Hypertension 65, no. 6 (2015): 1202–1208, 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mathiassen O. N., Vase H., Bech J. N., et al., “Renal Denervation in Treatment‐Resistant Essential Hypertension. A Randomized, SHAM‐Controlled, Double‐Blinded 24‐h Blood Pressure‐Based Trial,” Journal of Hypertension 34, no. 8 (2016): 1639–1647, 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schmieder R. E., Ott C., Toennes S. W., et al., “Phase II Randomized Sham‐Controlled Study of Renal Denervation for Individuals With Uncontrolled Hypertension‐WAVE IV,” Journal of Hypertension 36, no. 3 (2018): 680–689, 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Azizi M., Schmieder R. E., Mahfoud F., et al., “Endovascular Ultrasound Renal Denervation to Treat Hypertension (RADIANCE‐HTN SOLO): A Multicentre, International, Single‐Blind, Randomised, Sham‐Controlled Trial,” Lancet 391, no. 10137 (2018): 2335–2345, 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Azizi M., Schmieder R. E., Mahfoud F., et al., “Six‐Month Results of Treatment‐Blinded Medication Titration for Hypertension Control After Randomization to Endovascular Ultrasound Renal Denervation or a Sham Procedure in the RADIANCE‐HTN SOLO Trial,” Circulation 139, no. 22 (2019): 2542–2553, 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Azizi M., Daemen J., Lobo M. D., et al., “12‐Month Results From the Unblinded Phase of the RADIANCE‐HTN SOLO Trial of Ultrasound Renal Denervation,” JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 13, no. 24 (2020): 2922–2933, 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weber M. A., Kirtane A. J., Weir M. R., et al., “The REDUCE HTN: REINFORCE: Randomized, Sham‐Controlled Trial of Bipolar Radiofrequency Renal Denervation for the Treatment of Hypertension,” JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 13, no. 4 (2020): 461–470, 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Azizi M., Sanghvi K., Saxena M., et al, “Ultrasound Renal Denervation for Hypertension Resistant to a Triple Medication Pill (RADIANCE‐HTN TRIO): A Randomised, Multicentre, Single‐Blind, Sham‐Controlled Trial,” Lancet 397, no. 10293 (2021): 2476–2486, 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00788-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Azizi M., Mahfoud F., Weber M. A., et al., “Effects of Renal Denervation vs Sham in Resistant Hypertension After Medication Escalation,” JAMA Cardiology 7, no. 12 (2022): 1244, 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kario K., Hoshide S., Narita K., et al., “Cardiovascular Prognosis in Drug‐Resistant Hypertension Stratified by 24‐Hour Ambulatory Blood Pressure: The JAMP Study,” Hypertension 78, no. 6 (2021): 1781–1790, 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Heradien M., Mahfoud F., Greyling C., et al., “Renal Denervation Prevents Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Hypertensive Heart Disease: Randomized, Sham‐Controlled Trial,” Heart Rhythm 19, no. 11 (2022): 1765–1773, 10.1016/j.hrthm.2022.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pathak A., Rudolph U. M., Saxena M., et al., “Alcohol‐Mediated Renal Denervation in Patients With Hypertension in the Absence of Antihypertensive Medications,” EuroIntervention 19, no. 7 (2023): 602–611, 10.4244/EIJ-D-23-00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Azizi M., Saxena M., Wang Y., et al., “Endovascular Ultrasound Renal Denervation to Treat Hypertension: The RADIANCE II Randomized Clinical Trial,” Journal of the American Medical Association 329, no. 8 (2023): 651–661, 10.1001/jama.2023.0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mahfoud F., Kandzari D. E., Kario K., et al., “Long‐Term Efficacy and Safety of Renal Denervation in the Presence of Antihypertensive Drugs (SPYRAL HTN‐ON MED): A Randomised, Sham‐Controlled Trial,” Lancet 399, no. 10333 (2022): 1401–1410, 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00455-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kario K., Mahfoud F., Kandzari D. E., et al., “Long‐Term Reduction in Morning and Nighttime Blood Pressure After Renal Denervation: 36‐Month Results From SPYRAL HTN‐ON MED Trial,” Hypertension Research 46, no. 1 (2023): 280–288, 10.1038/s41440-022-01042-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kandzari D. E., Townsend R. R., Kario K., et al, “Safety and Efficacy of Renal Denervation in Patients Taking Antihypertensive Medications,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 82, no. 19 (2023): 1809–1823, 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Böhm M., Tsioufis K., Kandzari D. E., et al., “Effect of Heart Rate on the Outcome of Renal Denervation in Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 78, no. 10 (2021): 1028–1038, 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dolan E., Staessen J. A., and O'Brien E., “Data From the Dublin Outcome Study,” Blood Pressure Monitoring 12, no. 6 (2007): 401–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mancia G., Parati G., Bilo G., et al., “Assessment of Long‐Term Antihypertensive Treatment by Clinic and Ambulatory Blood Pressure: Data From the European Lacidipine Study on Atherosclerosis,” Journal of Hypertension 25, no. 5 (2007): 1087–1094, 10.1097/hjh.0b013e32805bf8ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ettehad D., Emdin C. A., Kiran A., et al., “Blood Pressure Lowering for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Death: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Lancet 387, no. 10022 (2016): 957–967, 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kario K., Weber M. A., Böhm M., et al., “Effect of Renal Denervation in Attenuating the Stress of Morning Surge in Blood Pressure: Post‐Hoc Analysis From the SPYRAL HTN‐ON MED Trial,” Clinical Research in Cardiology 110, no. 5 (2021): 725–731, 10.1007/s00392-020-01718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kario K., “Nocturnal Hypertension,” Hypertension 71, no. 6 (2018): 997–1009, 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.10971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kario K., Kai H., Rakugi H., et al., “Consensus Statement on Renal Denervation by the Joint Committee of Japanese Society of Hypertension (JSH), Japanese Association of Cardiovascular Intervention and Therapeutics (CVIT), and the Japanese Circulation Society (JCS),” Hypertension Research 39, no. 4 (2024): 376–385, 10.1038/s41440-024-01700-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Staplin N., de la Sierra A., Ruilope L. M., et al., “Relationship Between Clinic and Ambulatory Blood Pressure and Mortality: An Observational Cohort Study in 59 124 Patients,” Lancet 401, no. 10393 (2023): 2041–2050, 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00733-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang W. Y., Melgarejo J. D., Thijs L., et al., “Association of Office and Ambulatory Blood Pressure With Mortality and Cardiovascular Outcomes,” Journal of the American Medical Association 322, no. 5 (2019): 409, 10.1001/jama.2019.9811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Böhm M., Kario K., Kandzari D. E., et al, “Efficacy of Catheter‐Based Renal Denervation in the Absence of Antihypertensive Medications (SPYRAL HTN‐OFF MED Pivotal): A Multicentre, Randomised, Sham‐Controlled Trial,” Lancet 395, no. 10234 (2020): 1444–1451, 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jung O., Gechter J. L., Wunder C., et al., “Resistant Hypertension? Assessment of Adherence by Toxicological Urine Analysis,” Journal of Hypertension 31, no. 4 (2013): 766–774, 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835e2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bhatt D. L., Vaduganathan M., Kandzari D. E., et al., “Long‐Term Outcomes After Catheter‐Based Renal Artery Denervation for Resistant Hypertension: Final Follow‐Up of the Randomised SYMPLICITY HTN‐3 Trial,” Lancet 400, no. 10361 (2022): 1405–1416, 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01787-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Panchavinnin P., Wanthong S., Roubsanthisuk W., et al., “Long‐Term Outcome of Renal Nerve Denervation (RDN) for Resistant Hypertension,” Hypertension Research 45, no. 6 (2022): 962–966, 10.1038/s41440-022-00910-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supporting Information. Other data sets associated with the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.