Abstract

Aims: Previous studies investigating the link between infection with Borrelia burgdorferi and morphoea have produced conflicting results. Often, these studies have been undertaken in patients from different regions or countries, and using methods of varying sensitivity for detecting Borrelia burgdorferi infection. This study aimed to establish whether a relation could be demonstrated in the Highlands of Scotland, an area with endemic Lyme disease, with the use of a sensitive method for detecting the organism.

Methods: The study was performed on biopsies of lesional skin taken from 16 patients from the Highlands of Scotland with typical clinical features of morphoea. After histological confirmation of the diagnosis, a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers to a unique conserved region of the Borrelia burgdorferi flagellin gene was performed on DNA extracts from each biopsy. A literature search was also performed for comparable studies.

Results: None of the 16 patients had documented clinical evidence of previous infection with B burgdorferi. DNA was successfully extracted from 14 of the 16 cases but all of these were negative using PCR for B burgdorferi specific DNA, despite successful amplification of appropriate positive controls in every test. The results were compared with those of other documented studies.

Conclusions: Examination of the literature suggests that there is a strong geographical relation between B burgdorferi and morphoea. These results, in which no such association was found, indicate that morphoea may not be associated with the subspecies of B burgdorferi found in the Highlands of Scotland.

Keywords: morphoea, Borrelia burgdorferi, polymerase chain reaction

Erythema chronicum migrans, acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA), and lymphocytoma cutis are all cutaneous manifestations of Lyme disease, a multisystem disorder that follows infection with Borrelia burgdorferi.1–4 An aetiological role for B burgdorferi has also been proposed for other skin disorders, including primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma (PCBCL) and morphoea. Although there is increasing evidence to support this hypothesis in the context of PCBCL,5 studies investigating the link between B burgdorferi and morphoea have produced conflicting results, some reports suggesting a positive association, but others not.6 This has led to the proposal that regional variations in B burgdorferi may be important in dictating the spectrum of clinical disease following infection, with morphoea only being caused by certain subspecies endemic to specific geographical areas.7

“Studies investigating the link between Borrelia burgdorferi and morphoea have produced conflicting results, some reports suggesting a positive association, but others not”

Although Lyme disease is endemic in many areas of the UK, only two previous studies have investigated the possible link with morphoea specifically in the UK.8,9 Both gave a negative result, but this was based primarily on patients with morphoea lacking serological evidence of previous infection with B burgdorferi. However, because B burgdorferi infection may occur without the production of specific antibodies these results are inconclusive.10 Therefore, we used a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique to evaluate skin biopsies taken from patients with morphoea in the Highlands of Scotland, an area with endemic Lyme disease, for the presence or absence of B burgdorferi specific DNA. Recently, this approach has been used successfully to demonstrate a significant association between B burgdorferi and PCBCL in patients from the same region.5 A literature review was also performed to interpret our results in the context of the possible geographical variations that may exist in the relation between B burgdorferi infection and the subsequent development of morphoea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case selection

The pathology department, Raigmore Hospital, Inverness, UK, processes all surgical pathology specimens for the Highland and Western Isles regions of Scotland, an area with a population of approximately 250 000 in which Lyme disease is endemic. By searching the surgical pathology files, Raigmore Hospital, Inverness (from 1976 to date), and reviewing case records of all patients with histology compatible with morphoea we were able to identify 16 patients for study, all with histological and clinical features typical of morphoea.

Pathological studies

Sections (5 μm thick) were cut from formalin fixed, routinely processed, paraffin wax embedded tissue blocks of each biopsy and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Each case was assessed to confirm a diagnosis of morphoea and to approximate the stage of the disease using standard criteria.11

Demonstration of B burgdorferi DNA

Sections (6 × 5 μm) cut from formalin fixed, paraffin wax embedded tissue blocks were dewaxed and DNA extracted using the Intergen EX-WAX DNA extraction kit (Intergen, Manhattanville, New Jersey, USA). All DNA extracts were tested by PCR with primers for β globin to ensure that DNA of sufficient quality and quantity was obtained for subsequent analysis.

To detect B burgdorferi, a nested PCR assay was used to amplify a sequence of the highly conserved flagellin encoding region, as described previously.12 The first stage PCR was performed with 20 μl of sample in a reaction volume of 50 μl, containing final concentrations of 10mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5), 50mM KCl2, 3.5mM MgCl2 (Applied Biotechnologies), 0.2mM dNTP (Pharmacia Biosystems, Milton Keynes, UK), 0.5 U Taq polymerase (Applied Biotechnologies), and 0.5 μM of each primer F1 (5′-ATT AAC GCT GCT AAT CTT AGT-3′) and F3 (5′-GTA CTA TTC TTT ATA GAT TC-3′) (Severn Biotech, Kidderminster, UK). The thermal cycling conditions were 35 cycles of one minute at 94°C, two minutes at 41°C, and three minutes at 66°C, followed by a further extension period of five minutes at 72°C. For the nested PCR, 20 μl of a 1/5 dilution of the first stage product was amplified in a 50 μl reaction mix with a reduced concentration of MgCl2 (2.5mM) and primers F6 (5′-TTC AGG GTC TCA AGC GTC TTG GAC T-3′) and F8 (5′-GCA TTT TCA ATT TTA GCA AGT GAT G-3′) (Severn Biotech). The thermal cycling conditions were 35 cycles of one minute at 94°C, one minute at 50°C, and one minute at 72°C, with a final extension of five minutes at 72°C. A positive control (∼ 10 cultured B burgdorferi organisms) and negative control were included in all cases. The PCR products were visualised under ultraviolet transmission of ethidium bromide stained agarose gels.

Literature review

A textword Medline search was conducted for the years 1966 to date using the terms “morphea”, “morphoea”, “Lyme disease”, and “Borrelia” in various combinations. Abstracts of all articles were read and papers selected for inclusion if they were published in English and used laboratory techniques to investigate the relation between B burgdorferi infection and morphoea.

RESULTS

Clinical features

There were five male and 11 female patients ranging in age from 3 to 69 years at diagnosis. According to the classification of Peterson et al,13 there were 13 cases of plaque morphoea (12 morphoea en plaque, one atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini), two cases of linear morphoea (one linear morphoea, one en coup de sabre), and one case of generalised morphoea. None of the patients had a history of antibiotic treatment in their hospital notes and none had a documented history of manifestations of Lyme disease.

Pathological findings

All 16 cases showed histological features consistent with a diagnosis of morphoea, the principle finding being the presence of thickened collagen bundles in the reticular dermis. The histological stage of the lesion was approximated by additional changes.11 Three cases were interpreted as early stage lesions. All displayed a moderate lymphocytic infiltrate with fewer numbers of plasma cells arranged around blood vessels lined by swollen endothelial cells (fig 1 ▶). Six biopsies were regarded as showing features of late stage lesions. In these, there was increased eosinophilia of the thickened collagen bundles, together with homogeneous collagen in the papillary dermis, atrophy of eccrine glands with marked loss of periglandular fat, some fibrous thickening of blood vessel walls, and a minimal or absent chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate (fig 2 ▶). The remaining seven cases displayed features in keeping with lesions of an intermediate duration in which the “late” changes were either less pronounced, or only some were present.

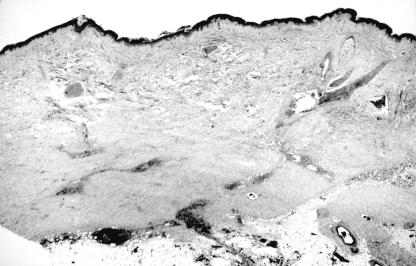

Figure 1.

Haematoxylin and eosin stained section (original magnification, ×20) showing early changes of morphoea. A perivascular infiltrate is present in the dermis and the superficial subcutis. The reticular dermis appears pale owing to the presence of swollen collagen bundles.

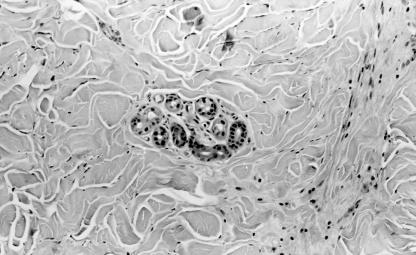

Figure 2.

Haematoxylin and eosin stained section (original magnification, ×100) showing later stage morphoea. Thickened collagen bundles fill the reticular dermis in the vicinity of an eccrine gland that has lost the normal surround of adipose tissue.

PCR analysis

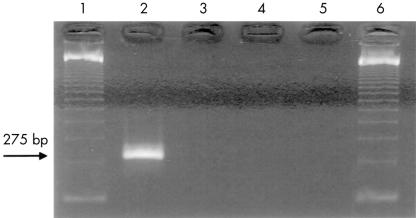

Amplifiable DNA was obtained from 14 of the 16 biopsies, as determined by PCR with primers for β globin. These 14 cases were tested using primers for the B burgdorferi flagellin gene. In each test, there was successful amplification of control DNA extracted from cultured borrelia organisms, giving a product of 275 bp after the nested run. However, all 14 samples from patients with morphoea were negative, as were the negative controls (fig 3 ▶).

Figure 3.

Agarose gel showing results after the polymerase chain reaction with Borrelia burgdorferi flagellin gene. Lanes 1 and 6, DNA molecular weight markers; lane 2, positive control; lane 3, negative control; lanes 4 and 5, negative results from DNA extracts of two cases of morphoea.

Literature review

Table 1 ▶ summarises the results of the literature review.14–37

Table 1.

Summary of previous studies investigating the relation between Borrelia burgdorferi infection and morphoea in different geographical locations

| Reference | Country | Direct visualisation in tissue sections of morphoea biopsies | Serology | Culture from biopsies of morphoeic lesions | PCR analysis of DNA extracts of morphoea biopsies |

| Aberer et al (1987)14 | Austria | 3/18 (immunoperoxidase) | 8/15 | 1/4 | ND |

| Aberer et al (1988)15 | Austria | 3/9 (immunoperoxidase) | 5/9 | ND | ND |

| Aberer et al (1991)16 | Austria | ND | 14/30 | 1/11 | ND |

| Aberer and Stanek (1987)17 | Austria | 4/13 (immunoperoxidase) | 7/13 | 1/3 | ND |

| Breier et al (1996)18 | Austria | ND | 13/39* | ND | ND |

| Aberer et al (1996)19 | Austria | 4/16 (immunoperoxidase) | ND | 0/22 | ND |

| Breier et al (1999)20 | Austria | 0/1 (silver stain) | 1/1 | 1/1† | ND |

| Fujiwara et al (1997)7‡ | Germany | ND | ND | ND | 3/4 |

| Schempp et al (1993)21 | Germany | ND | 0/5 | ND | 9/9 |

| Wienecke et al (1995)22 | Germany | ND | 4/18 | ND | 0/30 |

| Weide et al (2000)23 | Germany | ND | 3/53 | ND | 0/33 |

| Weber et al (1988)24 | Germany | ND | 0/2 | 2/2 | ND |

| Muhlemann et al (1986)8 | UK | ND | 0/22 | ND | ND |

| Lupoli et al (1991)9 | UK | ND | 0/31 | 0/9 | ND |

| Raguin et al (1992)25 | France | 0/14 (immunoperoxidase) | 0/15 | 0/10 | ND |

| Meiss et al (1993)26 | Holland | ND | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 |

| Ranki et al (1994)27 | Finland | ND | 1/7 | ND | 0/7 |

| Alonso-Llamazares et al (1997)28 | Spain | ND | 1/9 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| Trevisan et al (1996)29 | Italy | ND | 3/10 | ND | 6/10 |

| Buechner et al (1993)30 | Switzerland | ND | 10/10§ | ND | ND |

| Ozkan et al (2000)31 | Turkey | ND | ND | ND | 2/5 |

| Ross et al (1990)32 | Puerto Rico | 10/25 (silver stain) | ND | ND | ND |

| Fujiwara et al (1997)7‡ | Japan | ND | ND | ND | 2/5 |

| Fujiwara et al (1997)7‡ | USA | ND | ND | ND | 0/10 |

| Daoud et al (1994)33 | USA | 0/10 (silver stain) | 0/3 | ND | ND |

| Fan et al (1995)34 | USA | ND | ND | ND | 0/30 |

| Dillon et al (1995)35 | USA | ND | ND | ND | 0/20 |

| De Vito et al (1996)36 | USA | ND | ND | ND | 0/28 |

| Colome-Grimmer et al (1997)37 | USA | ND | ND | ND | 0/10 |

*Eleven of 39 cases in this study also showed an increased B burgdorferi induced proliferation of peripheral blood lymphocytes. †This represents the only positive culture where spirochaetes have been subtyped; in this instance PCR analysis confirmed B afzelii. ‡This study investigated patients from Germany, Japan, and USA; the results of each location are presented separately for clarity. §All patients in this study were selected on the basis of positive serology for borrelia infection; 7 of 7 tested also showed an increased B burgdorferi induced proliferation of peripheral blood lymphocytes. ND, not done; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

DISCUSSION

The suspicion that morphoea may occur as a consequence of infection with B burgdorferi was initially aroused by clinical observations of coexisting morphoea and ACA, a cutaneous manifestation of chronic borreliosis.38–40 Subsequently, several different methodologies have been used to investigate this relation, often with confusing and conflicting results (table 1 ▶). Initially, studies used positive serology for B burgdorferi as evidence of previous infection and sought to correlate this with clinical manifestations of morphoea. In several series, all patients with morphoea tested have been seronegative, including 53 patients included in two studies from the UK.8,9,21,25,26,33 Conversely, other studies have found specific antibodies to B burgdorferi in between 6% and 54% of unselected patients with morphoea.14–18,22,23,27–29 In addition to a humoral immune response to the organism, large numbers of patients with morphoea may display specific cellular immunoreactivity.18,30

Because negative serology does not exclude previous infection with B burgdorferi and because positive serology may merely represent coincidental infection, other studies sought more definite evidence of a causal link by seeking to demonstrate the organism in biopsies of lesional skin taken from patients suffering from morphoea. Attempts to visualise borrelia organisms directly in histological sections after silver staining or immunohistochemistry have met with mixed success, and in only a small number of cases have spirochaetes been demonstrated.14,15,17,19,20,25,32,33 In view of problems in evaluating positive results using these methodologies, recent studies have focused on more sensitive and specific PCR techniques to demonstrate the organism. Once more the results have been contradictory. Studies reporting a positive association between B burgdorferi infection and morphoea have shown evidence of the organism in between 26% and 100% of cases,7,21,29,31 whereas in a further 10 reports, including our current one, no positive cases have been identified in a total of 190 cases tested.22,23,26–28,34–37 Lastly, the culture of borrelia from biopsies of morphoeic lesions has also been attempted. Although several studies have produced completely negative results,9,19,25,26,28 success has been achieved in a small number of cases,14,16,17,20,24 and the negative results may be partly or wholly attributable to the fastidiousness of the organism in culture.

Two possible conclusions can be drawn from this diaspora of results. The less charitable argument is that all of the positive findings reported are the result of one or more of the following: clinical and/or histological misdiagnosis of ACA as morphoea, because both entities share several common features; the chance occurrence of B burgdorferi infection and morphoea, especially in cases from areas of endemic Lyme disease; the presence of another causative agent that may be transmitted at the same time as B burgdorferi; and contamination of samples, especially with regard to PCR studies. However, it is difficult to envisage that all positive results to date can be explained in this way. This is particularly so for one group of Austrian researchers who have consistently found positive titres for B burgdorferi in a significantly higher proportion of patients with morphoea than in controls, and who have successfully demonstrated B burgdorferi in biopsies of morpheoic skin by immunoperoxidase with specific antibodies, in addition to the use of culture and typing.14–20 If the positive results are taken at face value then an alternative explanation, as previously proposed, is that subspecies variations in B burgdorferi, which occur between different geographical locations, dictate the clinical manifestations that follow infection, with only certain strains possessing the characteristics required to initiate the development of morphoea.7 This phenomenon is already well documented for other accepted facets of borrelia infection. For example, ACA rarely occurs during the course of Lyme disease in North America where B burgdorferi sensu stricto is the dominant species, but is commonly seen in Europe where B afzelii and B garinii are more prevalent.41

“These results indicate that in the Scottish Highlands there is no association between infection with indigenous strains of Borrelia burgdorferi and the subsequent development of morphoea”

If this hypothesis is correct, then the literature suggests that B burgdorferi is implicated in the pathogenesis of at least some cases of morphoea in Austria (especially in the vicinity of Vienna),14–20 but almost certainly not in the USA or some, but possibly not all, parts of Germany.7,21–24,33–37 Isolated studies reporting a positive association in countries such as Italy, Switzerland, Puerto Rico, Turkey, and Japan, and a negative association in Spain, Finland, Holland, and France7,19,25–32 require corroboration before definite conclusions can be drawn about these geographical locations.

The results of our study can be assessed in a similar light using the Austrian studies as reference for an example of a population in which B burgdorferi plays a role in the pathogenesis of morphoea. Given the cohort of patients studied, a similar positive result should have been forthcoming if the strains of borrelia endemic in the Scottish Highlands also possessed the potential to initiate the development of morphoea, because this region has the highest incidence of Lyme disease in Scotland, and probably the UK.42 The breakdown of morphoea subtypes studied was similar to that described in one of the Austrian papers in which a positive association was also demonstrated, meaning that case selection was unlikely to have biased our results.16 In addition, we are confident that although PCR is prone to false negative results, our technique is sufficiently sensitive to have detected the organism were it present. Positive controls were amplified in each reaction and we have also used this technique to identify B burgdorferi in archival material from patients with PCBCL.5 In addition, our cases were not biased towards late stage morphoea and, coupled with the fact that B burgdorferi has been identified in biopsies of patients with morphoea up to 20 years after the onset of cutaneous lesions, this means that the age of the lesions sampled was unlikely to have produced a false negative result.14,21 Moreover, although not directly questioned, there was no evidence that our patients were receiving antibiotic treatment before biopsy and none had a history documenting previous manifestations of Lyme disease. These results indicate that in the Scottish Highlands there is no association between infection with indigenous strains of B burgdorferi and the subsequent development of morphoea.

Whether or not this negative result is entirely attributable to the particular strains of B burgdorferi encountered in the highlands, as compared with Austria, remains to be determined. However, the data currently available do not disprove this theory. We have recently typed 12 isolates of B burgdorferi sensu lato grown from highland ticks, five as B afzelii and seven as B burgdorferi sensu stricto, and discovered two different strains of the first organism and four of the second.43 Of particular interest to our current study was the finding that all strain types differed from reference strains derived from mainland Europe. In fact, such genomic heterogeneity appears to be normal, both within and between geographical areas.44–46 In view of this, and considering the expanding spectrum of disease attributed to B burgdorferi, further studies are warranted to investigate the effect of strain type on the clinical manifestations of infection.

Take home messages.

None of the 16 patients with morphoea had clinical evidence of previous infection with Borrelia burgdorferi

All of the 14 cases tested were negative for B burgdorferi specific DNA (using the polymerase chain reaction), despite successful amplification of appropriate positive controls in every test

Because the literature suggests that there is a strong geographical relation between B burgdorferi and morphoea, these results suggest that morphoea is probably not associated with the subspecies of B burgdorferi found in the Highlands of Scotland

Acknowledgments

This work was part funded by a grant from Raigmore Hospital, Research and Endowments Fund and part funded by grant K/MRS/50/C2774 awarded by the Chief Scientist Office, Edinburgh. The authors would also like to thank Dr J McPhie, Head of Pathology, Raigmore Hospital, Inverness, for his support and I Christie for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

ACA, acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

PCBCL, primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma

PCR, polymerase chain reaction

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashbrink E, Hovmark H. Successful cultivation of spirochetes from skin lesions of patients with erythema chronicum migrans Afzelius and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [B] 1985;93:161–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hovmark A, Asbrink E, Olsson I. The spirochetal etiology of lymphadenosis benigna cutis solitara. Acta Derm Venereol 1986;66:479–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgdorfer W, Barbour AG, Hayes SF, et al. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 1982;216:1317–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell PD, Reed KD, Vandermause MT, et al. Isolation of Borrelia burgdorferi from skin biopsy specimens of patients with erythema migrans. Am J Clin Pathol 1993;99:104–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodlad JR, Davidson MM, Hollowood K, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma and Borrelia burgdorferi infection in patients from the Highlands of Scotland. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1279–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weide B, Walz T, Garbe C. Is morphoea caused by Borrelia burgdorferi? A review. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:636–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujiwara H, Fujiwara K, Hashimoto K, et al. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA (B. garinii or B. afzelii) in morphoea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus tissues of German and Japanese but not of US patients. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:41–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhlemann MF, Wright DJM, Black C. Serology of Lyme disease. Lancet 1986;1:553–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lupoli S, Cutler SJ, Stephens CO, et al. Lyme disease and localized scleroderma—no evidence for a common aetiology. Br J Rheumatol 1991;30:154–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steere AC, Taylor E, McHugh GL, et al. The overdiagnosis of Lyme disease. JAMA 1993;269:1812–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaworsky C. Connective tissue diseases. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, et al, eds. Lever’s histopathology of the skin, 8th ed. New York: Lippincott-Raven, 1997:253–85.

- 12.Davidson MM, Evans R, Ling CL, et al. Isolation of Borrelia burgdorferi from ticks in the Highlands of Scotland. J Med Microbiol 1999;48;59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen LS, Nelson AM, Su WP. Classification of morphoea (localized scleroderma). Mayo Clin Proc 1995;70:1068–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aberer E, Stanek G, Er HM, et al. Evidence for spirochetal origin of circumscribed scleroderma (morphoea). Acta Derm Venereol 1987;67:225–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aberer E, Kollegger H, Kristoferitsch W, et al. Neuroborreliosis in morphoea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988;19:820–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aberer E, Klade H, Stanek G, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi and different types of morphoea. Dermatologica 1991;182:145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aberer E, Stanek G. Histological evidence for spirochetal origin of morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Am J Dermatopathol 1987;9:374–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breier F, Klade H, Stanek G, et al. Lymphoproliferative responses to Borrelia burgdorferi in circumscribed scleroderma. Br J Dermatol 1996;134:285–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aberer E, Kerstan A, Klode H, et al. Heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the skin. Am J Dermatopathol 1996;18:571–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breier FH, Aberer E, Stanek G, et al. Isolation of Borrelia afzelii from circumscribed scleroderma. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:925–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schempp C, Bocklage H, Lange R, et al. Further evidence for Borrelia burgdorferi infection in morphoea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus confirmed by DNA amplification. J Invest Dermatol 1993;100:717–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wienecke R, Schlupen EM, Zochling N, et al. No evidence for Borrelia burgdorferi-specific DNA in lesions of localized scleroderma. J Invest Dermatol 1995;104:23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weide B, Schttek B, Klyscz T, et al. Morphoea is neither associated with features of Borrelia burgdorferi infection, nor is this agent detectable in lesional skin by polymerase chain reaction. Br J Dermatol 2000;143:780–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber K, Prac-Mursic V, Reimers CD. Spirochaetes isolated from two patients with morphoea. Infection 1988;16:25–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raguin G, Boisnic S, Souteyrand, et al. No evidence for a spirochetal origin of localized scleroderma. Br J Dermatol 1992;127:218–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meiss JF, Koopman R, van Bergen B, et al. No evidence for a relationship between Borrelia burgdorferi infection and old lesions of localized scleroderma. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:386–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranki A, Aavik E, Peterson P, et al. Successful amplification of DNA specific for Finish Borrelia burgdorferi isolates in erythema chronicum migrans but not in scleroderma lesions. J Invest Dermatol 1994;102:339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alonso-Llamazares J, Persing DH, Anda P, et al. No evidence for Borrelia burgdorferi infection in lesions of morphoea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in Spain. A prospective study and literature review. Acta Derm Venereol 1997;77:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trevisan G, Stinco G, Nobile C, et al. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi in skin biopsies from patients with morphoea by polymerase chain reaction. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1996;6:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buechner SA, Winklemann RK, Lautenschlager S, et al. Localized scleroderma associated with Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Clinical, histologic and immunohistochemical observations. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;29:190–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozkan S, Atabey N, Fetil E, et al. Evidence for Borrelia burgdorferi in morphea and lichen sclerosus. Int J Dermatol 2000;39:278–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross SA, Sanchez JL, Taboas JO. Spirochetal forms in the dermal lesions of morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Am J Dermatopathol 1990;12:357–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daoud MS, Su WP, Leiferman KM, et al. Bullous morphea: clinical, pathologic, and immunopathologic evaluation of thirteen cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30:937–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan W, Leonardi CL, Penneys NS. Absence of Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with localized scleroderma (morphea). J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;33:682–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dillon WI, Saed GM, Fivenson DP. Borrelia burgdorferi DNA is undetectable by polymerase chain reaction in skin lesions of morphoea, scleroderma, or lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of patients from North America. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;33:617–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Vito JR, Merogi AJ, Vo T, et al. Role of Borrelia burgdorferi in the pathogenesis of morphoea/scleroderma and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a PCR study of thirty-five cases. J Cutan Pathol 1996;23:350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colome-Grimmer MI, Payne DA, Tyring SK, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi DNA and Borrelia hermsii DNA are not associated with morphea or lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in the southwestern United States [letter]. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abele DC, Bedingfield RB, Chandler FW, et al. Progressive facial hemiatrophy (Parry-Romberg syndrome) and borreliosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:531–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asbrink E, Hovmark A, Olsen I. Clinical manifestations of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans in 50 Swedish patients. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie Mikrobiologie und Hygiene/Reihe A 1986;263:253–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asbrink E, Brehmer-Anderson E, Hovmark A. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans—a spirochaetosis. A clinical and histological picture based on 32 patients: course and relationship to erythema chronicum migrans Afzelius. Am J Dematopathol 1986;8:209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 1998;352:557–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho-Yen DO, Davidson MM, Joss AWL. How prevalent is Lyme disease in Scotland? SCIEH Weekly Report 1999;33:214–15. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ling CL, Joss AWL, Davidson MM, et al. Identification of different Borrelia burgdorferi genomic groups from Scottish ticks. Mol Pathol 2000;53:94–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang G, van Dam AP, Spanjaard L, et al. Molecular typing of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting analysis. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:768–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mathiesen DA, Oliver JH, Jr, Kalbert CP, et al. Genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States. J Infect Dis 1997;175:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Junttila J, Peltomaa M, Soini H, et al. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ricinus ticks in urban recreational areas of Helsinki. J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:1361–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]