Abstract

Life satisfaction predicts lower risk of adverse health outcomes, including morbidity and mortality. Research on life satisfaction and risk of dementia has been limited by a lack of comprehensive clinical assessments of dementia. This study builds on previous research examining life satisfaction and clinically ascertained cognitive impairment and dementia. Participants (N = 23070; Meanage = 71.83, SD = 8.80) from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center reported their satisfaction with life at baseline. Incident dementia was ascertained through clinical assessment over up to 18 years. Life satisfaction was associated with about 72% lower risk of all-cause of dementia, an association that remained significant accounting for demographic (age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, marital and living status), psychological (depression), clinical (obesity, diabetes, hypertension), behavioral (current and former smoking), and genetic risk (APOE ϵ4) factors. The association was not moderated by demographics, depression, and APOE ε4 status groups. The association was similar when cases occurring in the first five years were excluded, reducing the likelihood of reverse causality. Life satisfaction was also linked to specific causes of dementia, with a reduced risk ranging from about 60% to 90% for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia to > 2-fold lower risk of Lewy Body and frontotemporal dementia. Older adults who were satisfied with their lives were also at 61% lower risk of incident mild cognitive impairment and at 22% lower risk of converting from mild cognitive impairment to dementia. Being satisfied with one’s life is associated with a lower risk of dementia. Improving life satisfaction could promote better cognitive health and protect against dementia.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-024-01443-2.

Keywords: Life satisfaction, Dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease, Vascular dementia, Frontotemporal dementia, Cognitive impairment

Introduction

Life satisfaction, a component of subjective well-being (SWB), is the global cognitive judgment of one’s life [1, 2] and is crucial to many outcomes, including health and longevity. Individuals who are more satisfied with their lives, for example, tend to have a reduced risk of developing diabetes, cardiovascular problems, depressive symptoms, and live longer compared to their less satisfied counterparts [3–5]. Yet, limited work has examined the association between life satisfaction and incident dementia [6–8] with the recommendation for further research on this association [9].

Previous longitudinal work on life satisfaction and incident dementia was limited by relatively younger participants (except [7]) and short follow-up (with a range of 5 to 12 years of follow-up) [6–8, 10, 11]. Examining older participants is important because they are the age group at greater risk of developing dementia, with rates rising dramatically after the age of 65 [12], and long follow-up can help identify more incident cases, increase power, and reduce the risk of reverse causality, particularly given the long preclinic and prodromal stages of dementia. Most importantly, a limitation of most previous research [6, 8, 10] is the lack of clinical diagnosis when assessing dementia status. Many studies relied on measurements like the Mini-Mental State Examination, which can result in misclassification of some participants and a consequent loss of statistical power [10]. Clinical diagnoses can reduce measurement biases and provide more robust estimates of the association. Indeed, a meta-analysis on purpose in life, another component of well-being, found the largest effect in the study that used a clinical diagnosis compared to the studies that used brief screening tools for dementia classifications [13]. Additionally, clinical diagnosis provides information on the etiology of dementia, and we are unaware of any study that has examined the association of life satisfaction with specific causes of dementia. A recent study revealed that some life domains (e.g., health satisfaction) were associated with lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and a stronger association with Vascular Dementia (VD) [9]. Even less is known for Lewy Body (LBD) and frontotemporal dementia (FTLD).

Previous studies have found conflicting results on the protective role of life satisfaction on dementia risk, particularly when controlling for other risk factors: One study (N = 10099 with up to 8 years follow-up) reported that the association of life satisfaction with risk of dementia was not independent of depressive symptoms [8], while a more recent study (N = 8021 with up to 12 years of follow-up) revealed that the association was independent not only of depressive symptoms but also of other risk factors [10]. Of note, other studies either did not account for depressive symptoms in the model or combined depression with other risk factors [7, 11]. These contradictory findings highlight the uncertainty of whether the protection of life satisfaction on dementia persists in the context of depression.

The present research adds to the emerging literature in several ways. First, the current study examines whether life satisfaction in older adults is associated with incident mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia based on clinical assessments over up to 18 years of follow-up in one of the largest studies to date. Second, the study tests whether life satisfaction is associated with dementia risk after accounting for potential demographic, clinical, and behavioral factors related to either life satisfaction or incident dementia, including depression. Third, the study investigates whether the association extends to cause specific dementia (AD, LBD, VD, FTLD). Lastly, the study explores whether the association was moderated by demographic variables, depression, and genetic vulnerability.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC), an ongoing longitudinal study that includes over 50000 participants from the collaboration of more than 37 Alzheimer's Disease Research Centers (ADRC) across the United States. Since 2005, ADRCs have provided annual comprehensive clinical evaluations of individuals participating in the National Institute on Aging’s ADRC Program. These evaluations include medical, psychiatric, and neurologic histories; neuropsychological test results and clinical diagnosis of cognitive status. During the standardized visit, trained clinicians or clinical personnel complete Uniform Data Set (UDS) forms for each participant through direct observation and/or examination. All NACC participants provided informed consent before each assessment.

The current study used the NACC data freeze of March 2024. Exclusion criteria were individuals who withdrew from the study after baseline (n = 9505), were younger than 50 (n = 552), had a dementia diagnosis at initial visit (n = 14146), or missing data on life satisfaction at baseline (did not respond/no data is available) (n = 3689). The final sample included 23070 individuals with data on life satisfaction and without dementia at baseline. The flowchart of the selection of study participants is in Fig. 1. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study participants selection

Measures

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was assessed using the item “Are you basically satisfied with your life?” (yes/no) from the Geriatric Depression Scale (GAS) [14]. This variable was coded in the direction of being satisfied (no = 0, yes = 1), such that participants who reported not being satisfied with their lives were coded as the reference group.

Incident dementia

Trained clinicians determined whether participants met the criteria for all-cause dementia at the time of assessment (0 = no, 1 = yes). Dementia criteria changed over UDS versions. In versions 1 (September 2005-February 2008) and 2 (until March 2015), specific diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of dementia were not provided. However, most centers used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fourth Edition (DSM-IV [15] criteria for dementia; Researchers Data Dictionary: https://naccdata.org/). In version 3, implemented in March 2015, dementia diagnosis was based on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [16]. CDR training was required for ADC personnel and provided by the Washington University ADC (https://knightadrc.wustl.edu/cdr-training-application/). Dementia diagnosis was made by either a consensus team or an examining physician. Clinicians were also asked to mark the primary etiological diagnoses assessed as part of the UDS exam, including AD, LBD, VD, and FTLD.

Covariates and moderators

Demographic covariates were sex (0 = female, 1 = male), baseline age (in years), race (0 = white, 1 = not white), Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (0 = no, 1 = yes), education (in years), marital status (0 = non-married, 1 = married/living as married), and living alone (0 = not alone, 1 = live alone). Depression was based on a single item assessing whether individuals had depression in the last two years (0 = no, 1 = yes). Clinical risk factors were obesity (BMI ≥ 30; based on staff-assessed weight and height, 0 = no, 1 = yes), reported diagnoses of diabetes (0 = no, 1 = yes), and hypertension (0 = no, 1 = yes). Behavioral risk factors were current (0 = no, 1 = yes) and former smoking (0 = no, 1 = yes). Genetic vulnerability was based on APOE ϵ4 carrier status (0 = no ϵ4 allele, 1 = ϵ4 allele present).

Data analysis

Cox Proportional Hazards Regression was used to test the association between life satisfaction and incident dementia. Survival time was calculated in years from baseline assessment to the date of earliest dementia diagnosis for both all-cause and cause-specific dementia analyses. Participants who did not develop dementia were censored at the last visit date.

We examined the risk of dementia for individuals satisfied with life (reference: not being satisfied). Model 1 included age and sex. Model 2 further included race, ethnicity, education, marital status, and living alone. Model 3 was Model 2 plus depression. Model 4 was Model 3 plus clinical (obesity, diabetes, hypertension), behavioral (current and former smoking), and genetic risk (APOE ϵ4) factors associated with dementia risk. We further examined whether demographic variables, depression, and genetic vulnerability moderated the association between life satisfaction and dementia by testing interaction terms (e.g., sex-by-life satisfaction) in the basic model. Finally, we tested the association between life satisfaction and cause-specific dementia (AD, LBD, VD, FTLD).

We then ran sensitivity and supplemental analyses to examine the robustness of the findings and the role of MCI. First, we stratified study participants by follow-up time < 5 years (Model 1.1) and ≥ 5 years (Model 1.2). Second, we excluded participants with MCI and cognitive impairment-not MCI at baseline. Third, we examined life satisfaction as a predictor of conversion from any MCI to dementia. Fourth, we tested whether life satisfaction was associated with incident MCI. Two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used the Percentage of Excess Risk Mediated (PERM) formula: [(HRmodel1—HRmodel > 1)/(HRmodel1—1)] × 100 to estimate to what extent each group of covariates explained the association between life satisfaction and dementia.

Results

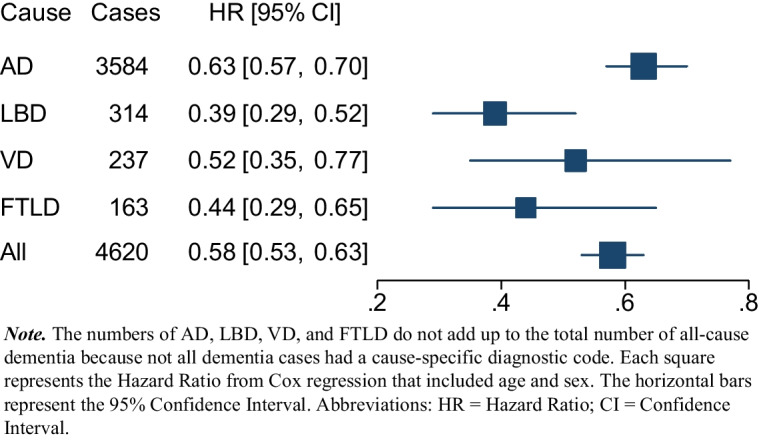

At the baseline assessment, 23070 NACC participants (13814 female, 9256 male) ranged in age from 50 to 109 years (mean [SD] age, 71.83 [8.80]. During the 18.23 years of follow-up (mean [SD], 5.06 [4.00]) years; 116803 person-years), 4620 participants (20.0%) developed dementia, including 3584 (77.6%) AD, 314 LBD (6.8%), 237 VD (5.1), and 163 FTLD (3.6%). The numbers of AD, LBD, VD, and FTLD do not add up to the total number of all-cause dementia because not all dementia cases had a cause-specific diagnostic code. Among the 2258 individuals who reported not being satisfied with their life, 594 (26.3%) developed dementia; among 20812 participants who reported satisfaction with their life, 4620 (19.3%) developed dementia. At baseline, the 4620 individuals who were later diagnosed with dementia were more likely to be male, older, white, depressed, married, and had genetic vulnerability compared to individuals who were not diagnosed with dementia at follow-up (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study variables for the full sample and by incident dementia

| Total | All-cause dementia | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Variables, No. (%) | 23070 | 18450 (80.0) | 4620 (20.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 13814 (59.9) | 11411 (61.8) | 2403 (52.0) |

| Male | 9256 (40.1) | 7039(38.2) | 2217 (48.0) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 71.83 (8.80) | 71.00 (8.70) | 75.12 (8.39) |

| Education, mean (SD), y (n = 22979) | 15.72 (3.08) | 15.77 (3.03) | 15.51 (3.24) |

| Race (White) (n = 22967) | 18347 (79.9) | 14388 (78.4) | 3959 (85.9) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino) (n = 22995) | 1657 (7.2) | 1407 (7.7) | 250 (5.4) |

| Marital status (n = 22897) | |||

| not married | 8297(36.2) | 6886 (37.6) | 1411 (30.5) |

| Married | 14610 (63.8) | 11412 (62.4) | 3198 (69.5) |

| Living alone (n = 23005) | |||

| Alone | 6628(28.8) | 5503 (29.9) | 1125 (24.4) |

| not alone | 16377 (71.2) | 12889 (70.1) | 3488 (75.6) |

| Life satisfaction | |||

| Yes | 20812 (90.2) | 16786 (91.0) | 4026 (87.1) |

| No | 2258 (9.8) | 1664 (9.0) | 594 (12.9) |

| Depression (active depression in the last two years) (n = 22916) | 5037 (22.0) | 3684 (20.1) | 1353 (29.5) |

| Diabetes (n = 22991) | 3024 (13.2) | 2428 (13.2) | 596 (12.9) |

| Obesity | 5536 (24.0) | 4748 (25.7) | 788 (17.1) |

| Hypertension, yes (n = 22980) | 11569 (50.3) | 9131 (49.7) | 2438 (52.9) |

| Smoking | |||

| Current (n = 22519) | 9768 (43.4) | 7828 (43.4) | 1940 (43.3) |

| Never (n = 22530) | 13517 (60,0) | 10853 (60.2) | 2664 (59.4) |

| APOE ϵ4 present (n = 19940) | 7019 (35.2) | 5028 (31.8) | 1991 (48.4) |

In parenthesis are SD or %

Participants who reported satisfaction with their life were at lower risk of dementia in Model 1; those who were satisfied with their life at baseline had 72% (1/0.58 = 0.72) lower risk of dementia (Table 2). The association was similar in Models 2 and 3, and attenuated by roughly one-third accounting for depression, clinical, and behavioral covariates in Models 3 and 4. The overall pattern of results was similar for specific causes of dementia in Model 1 and 2, with effects ranging from about 60% to 90% for AD and VD to > 2-fold lower risk of LBD and FLTD (Fig. 2). After controlling for depression, the association became non-significant for VD, while the associations remained significant for AD, LBD, and FTLD. The findings were essentially the same in the fully adjusted model (Table 3).

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards regression results of life satisfaction predicting incident dementia

| Cases (n) / total (No.) | HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 4620/23070 | 0.58 (0.53–0.63) |

| Model 2 | 4562/22624 | 0.56 (0.51–0.61) |

| Model 3 | 4533/22488 | 0.71 (0.65–0.78) |

| Model 4 | 3828/18624 | 0.69 (0.62–0.76) |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||

| Model 1.1, follow-up < 5 years | 3314/13907 | 0.64 (0.58–0.70) |

| Model 1.2, follow-up ≥ 5 years | 1306/9163 | 0.64 (0.53–0.77) |

| Participants without cognitive impairment | ||

| Model 1 | 1174/14307 | 0.54 (0.45–0.66) |

| Model 2 | 1155/14024 | 0.53 (0.44–0.65) |

| Model 3 | 1153/13946 | 0.62 (0.51–0.76) |

| Model 4 | 1038/11802 | 0.63 (0.51–0.78) |

| Conversion from CI to dementia | ||

| Model 1 | 3446/8741 | 0.82 (0.75–0.91) |

| Model 2 | 3407/8589 | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) |

| Model 3 | 3380/8521 | 0.86 (0.78–0.95) |

| Model 4 | 2790/6810 | 0.82 (0.73–0.92) |

| Incident cognitive impairment | ||

| Model 1 | 2985/13887 | 0.62 (0.55–0.70) |

| Model 2 | 2913/13605 | 0.64 (0.56–0.73) |

| Model 3 | 2904/113528 | 0.73 (0.64–0.83) |

| Model 4 | 2520/11427 | 0.73 (0.63–0.85) |

Model 1 included age and sex. Model 2 is Model 1 plus race, ethnicity, education, marital status, living alone. Model 3 is Model 2 plus depression. Model 4 is Model 3 plus physical health (diabetes, hypertension, obesity), smoking behavior (current and former), and APOE ϵ4

Fig. 2.

Associations of life satisfaction and specific cause of dementia

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards regression results of life satisfaction predicting AD, LBD, VD, FTLD

| Reference (not satisfied) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | LBD | VD | FTLD | |

| Model 1, # dementia | 3584/22351 | 314/19041 | 237/18993 | 163/18935 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | 0.63 (0.57–0.70) | 0.39 (0.29–0.52) | 0.52 (0.35–0.77) | 0.44 (0.29–0.65) |

| Model 2, # dementia | 3537 /21924 | 310/18658 | 236/18613 | 159/18551 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | 0.61 (0.55–0.67) | 0.35 (0.26–0.48) | 0.53(0.36–0.79) | 0.38 (0.25–0.58) |

| Model 3, # dementia | 3515/21781 | 309/18536 | 234/18490 | 159/18430 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | 0.77 (0.69–0.86) | 0.48 (0.35–0.66) | 0.73 (0.48–1.10) | 0.40 (0.26–0.61) |

| Model 4, # dementia | 2974/18042 | 243/15287 | 197/15260 | 140/15210 |

| Model 4, HR (95% CI) | 0.74 (0.65–0.83) | 0.43(0.30–0.62) | 0.90(0.54–1.49) | 0.38(0.24–0.61) |

Model 1 included age and sex. Model 2 is Model 1 plus race, ethnicity, education, marital status, living alone. Model 3 is Model 2 plus depression. Model 4 is Model 3 plus clinical (diabetes, hypertension, obesity), behavioral (current and former smoking), and genetic factors (APOE ϵ4)

Moderation

There was no moderation by sex, age, race, ethnicity, marital status, depression, and APOE ϵ4. There was a weak but significant interaction of life satisfaction with education (p = 0.015): life satisfaction had a 45% protective effect among individuals with high school or less (12 years) versus a 79% reduced risk among those with higher education (Table S1).

Sensitivity analysis

Accounting for demographic variables, the association between life satisfaction and risk of all-cause dementia was similar when follow-up was < 5 and ≥ 5 years (Table 2). In analyses that excluded participants with cognitive impairment-not-MCI or MCI at baseline, participants who were satisfied with their life were about 85% lower risk of all-cause dementia in the basic model and Model 2. After accounting for depression, the association was attenuated by roughly one-fifth, but still significant in Model 3, and in the fully adjusted Model 4 (Table 2).

In the analysis that included only participants with any cognitive impairment at baseline, participants satisfied with their life were about 22% lower risk of progressing to dementia in Model 1. The association remained similar across Model 2 to 4, but notably, depression attenuated by roughly one-third the association of life satisfaction and dementia (Table 2).

To examine the association between life satisfaction and risk of incident MCI, we further excluded participants with cognitive impairment (MCI or cognitive impairment-not-MCI) at baseline and those who progressed directly to dementia. Individuals who were satisfied with their lives had almost 61% lower risk of incident MCI. The association was similar in Model 2. The association attenuated by roughly one-quarter, but held after accounting for depression in Model 3 and clinical and behavioral covariates in Model 4 (Table 2).

Discussion

This study examined the association between life satisfaction and incident dementia over 18 years in a US sample of older adults. We found that life satisfaction at baseline was prospectively associated with a lower risk of incident dementia. The association was significant in models that progressively accounted for demographic (age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, and living alone), physical (diabetes, hypertension, obesity), psychological (depression), behavioral (current and former smoking), and genetic (APOE ϵ4) risk. With the exception of education, most interactions were not significant, indicating that the association was similar across demographic variables, depression, and genetic risk status. The cause-specific analyses indicated that life satisfaction was associated with each specific cause, but slightly stronger with FTLD and LBD than AD and VD. Furthermore, the overall pattern of association was similar when cases occurring in the first five years were excluded, a finding that is contrary to what would be expected with reverse causality. Additionally, follow-up analyses found evidence that individuals satisfied with their lives were at lower risk of incident MCI. And among those with MCI at baseline, individuals satisfied with their lives were at lower risk of converting from MCI to dementia.

Our results suggest that life satisfaction is protective against incident MCI and dementia, which is consistent with the notion that life satisfaction is a health asset [17, 18] and consistent with the well-being literature on the importance of life satisfaction for better cognitive functioning [6, 7, 11]. The current study provides novel evidence that life satisfaction is also protective against specific diseases leading to dementia. Further, the protective role of life satisfaction persists from normal cognition to MCI as well as from MCI to dementia. Thus, even in the prodromal stage, being satisfied with life is protective and helps delay the progression to dementia.

Previous work on life satisfaction and dementia has yielded mixed results in the context of depression: While one study found no significant association of life satisfaction with incident dementia after accounting for depression [8] another study reported a significant association even after accounting for depression, cardiovascular and functional risk factors, health behaviors, and social contact [10]. In line with the latter study, depressive symptoms appeared to partly account for the association between life satisfaction and incident dementia, reducing the effect size of life satisfaction by about 34%, but the associations remained mostly significant, with the only exception for the smaller subsample with VD. Zhu and colleagues' study was based on a Korean sample, and they discussed the possibility of cultural factors influencing the association between life satisfaction, depression, and risk of dementia [10]. Our findings, based on the largest US sample to date, suggest that life satisfaction could have a protective effect independent of depression also in the US cultural context.

The association between life satisfaction and risk of dementia was not modified by other risk factors like older age, living alone, depression, or presence of the APOE ϵ4. This finding replicates previous work that found no interaction with sex, age, race, ethnicity, marital status [7, 8, 11], depression [10] and APOE ϵ4 [8]. However, the association was stronger among people with higher education, contrary to some smaller studies [7, 8]. Besides education, the moderation analyses suggest that the role of life satisfaction in dementia tends to be similar across segments of the population, including those at high risk of dementia, such as older individuals, those who live alone, depressed, and even those with a genetic vulnerability.

There were differences in the strength of the associations across the causes of dementia that were examined. However, such differences should be interpreted in the context of the relatively small sample sizes for VD, LDB, and FTLD. These findings need to be replicated in other samples. The comparatively weaker effect observed for VD in the NACC sample is inconsistent with a study based on a UK sample that found health satisfaction and the breadth of satisfaction to have slightly stronger association with VD compared to AD risk [9]. Thus, based on the relatively small samples, the inconsistency with a previous study, and given that most dementia cases have multiple pathologies, it could be premature to draw conclusions about potential differential effects.

Some potential mechanisms through behavioral and biological pathways could partly explain the association between life satisfaction and incident dementia. First, life satisfaction is linked to health-promoting behaviors such as physical activity, less smoking, and a healthier diet [19, 20] as well as better health outcomes (e.g., diabetes) [4, 5], which in turn are protective against dementia [21, 22]. Additionally, individuals who are satisfied with their lives also tend to have better stress responses [23, 24], which may protect against dementia [22, 25]. Life satisfaction is likewise associated with healthier inflammatory profiles [26] that are associated with lower risk of dementia [27]. Future studies would benefit from understanding the functional role of life satisfaction on individuals’ health.

The findings provide some implications for intervention and policy. Health issues, unstable social support, and financial strain are important determinants of (low) life satisfaction [28], while regular exercise and physical activity can enhance life satisfaction among older adults [29]. Screening studies to identify targeted groups, particularly among vulnerable groups (e.g., individuals with less education), and support programs to improve life satisfaction could be beneficial. Further, developing health and social policies to enhance life satisfaction through promoting a healthier lifestyle could help reduce the risk of dementia among older adults. Lastly, while this study focused on life satisfaction as a protective factor before the onset of dementia, our MCI-related findings suggest that life satisfaction is likely to contribute to quality of life and more desirable health trajectories even after the onset of cognitive impairment.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, including the clinical diagnoses of dementia by clinicians based on comprehensive cognitive assessments, recruitment and assessment at ADRCs across the US, a large sample, older age at baseline, a long follow-up, a broad range of covariates and moderators, and the analyses of cause-specific dementia. However, the study has some limitations. First, despite the sensitivity analysis suggesting that the protective effect of life satisfaction on dementia persists when excluding the first 5 years follow-up, the observational data can not determine causality. Second, while a large cohort recruited across the U.S., the NACC sample is likely older, more educated, and has worse subjective memory and hearing than the U.S. general population [30]. Lastly, life satisfaction was measured by a single binary item. Despite the validity of single-item measures as compared to the Satisfaction with Life Scale [31, 32], levels of satisfaction and domain-specific life satisfaction were not assessed. Future studies investigating how changes in life satisfaction over time, including after experiencing financial difficulties or other life events associated with dementia risk [33], may provide valuable insights into this association.

Conclusions

This study found that older individuals who reported being satisfied with their lives have a lower risk of incident dementia over 18 years. A pattern of stronger associations was observed for LDB and FTLD than AD and VD. These findings suggest that psychosocial interventions to maintain and improve satisfaction with life could promote better cognitive health and protect against the incident MCI and dementia.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted using the NACC Data Request Number 11559.

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U24 AG072122. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADRCs: P30 AG062429 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P30 AG066468 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P30 AG062421 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P30 AG066509 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P30 AG066514 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG066530 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG066507 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P30 AG066444 (PI John Morris, MD), P30 AG066518 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG066512 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG066462 (PI Scott Small, MD), P30 AG072979 (PI David Wolk, MD), P30 AG072972 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P30 AG072976 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P30 AG072975 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG072978 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P30 AG072977 (PI Robert Vassar, PhD), P30 AG066519 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P30 AG062677 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P30 AG079280 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG062422 (PI Gil Rabinovici, MD), P30 AG066511 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG072946 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG062715 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P30 AG072973 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG066506 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG066508 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD), P30 AG066515 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG072947 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P30 AG072931 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG066546 (PI Sudha Seshadri, MD), P20 AG068024 (PI Erik Roberson, MD, PhD), P20 AG068053 (PI Justin Miller, PhD), P20 AG068077 (PI Gary Rosenberg, MD), P20 AG068082 (PI Angela Jefferson, PhD), P30 AG072958 (PI Heather Whitson, MD), P30 AG072959 (PI James Leverenz, MD).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01AG068093, R01AG053297, and R01AG074573. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data availability

The NACC data are available to researchers who apply with a NACC data request (https://naccdata.org/requesting-data/data-request-process). Key elements of the application include a research plan, the goal of the analysis using NACC data, and a listing of requested variables.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Selin Karakose, Email: selin.karakose@med.fsu.edu.

Antonio Terracciano, Email: antonio.terracciano@med.fsu.edu.

References

- 1.Diener E, et al. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucas RE, Diener E. Personality and subjective well-being. The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener, 2009; 37. pp. 75-102.

- 3.Joshanloo M. Longitudinal relations between depressive symptoms and life satisfaction over 15 years. Appl Res Qual Life. 2022;17(5):3115–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martín-María N, et al. The impact of subjective well-being on mortality: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies in the general population. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(5):565–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willroth EC, et al. Being happy and becoming happier as independent predictors of physical health and mortality. Psychosom Med. 2020;82(7):650–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aschwanden D, et al. Predicting cognitive impairment and dementia: A machine learning approach. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(3):717–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peitsch L, et al. General life satisfaction predicts dementia in community living older adults: a prospective cohort study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(7):1101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Psychological well-being and risk of dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(5):743–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu X, et al. Multidimensional assessment of subjective well-being and risk of dementia: Findings from the UK Biobank Study. J Happiness Stud. 2023;24(2):629–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu X, et al. Satisfaction with life and risk of dementia: Findings from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Gerontol: Ser B. 2022;77(10):1831–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawtaer I, et al. Psychosocial risk and protective factors and incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia in community dwelling elderly: Findings from the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(2):603–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrada MM, et al. Dementia incidence continues to increase with age in the oldest old: the 90+ study. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(1):114–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutin AR, et al. Sense of purpose in life is associated with lower risk of incident dementia: A meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;83(1):249–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric depression scale (GDS) recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5(1–2):165–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association A, Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. Vol. 4. Washington: American psychiatric association; 1994.

- 16.Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR) current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412-2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kim ES, et al. Life satisfaction and subsequent physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health in older adults. Milbank Q. 2021;99(1):209–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura JS, et al. Are all domains of life satisfaction equal? Differential associations with health and well-being in older adults. Qual Life Res. 2022;31(4):1043–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boehm JK, et al. Longitudinal associations between psychological well-being and the consumption of fruits and vegetables. Health Psychol. 2018;37(10):959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vijayakumar G, Devi ES, Jawahar PD. Life satisfaction of elderly in families and old age homes: a comparative study. Int J Nurs Educ. 2016;8:94–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloppenborg RP, et al. Diabetes and other vascular risk factors for dementia: which factor matters most? A systematic review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585(1):97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallensten J, et al. Stress, depression, and risk of dementia - a cohort study in the total population between 18 and 65 years old in Region Stockholm. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023;15(1):161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smyth JM, et al. Global life satisfaction predicts ambulatory affect, stress, and cortisol in daily life in working adults. J Behav Med. 2017;40(2):320–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zilioli S, Imami L, Slatcher RB. Life satisfaction moderates the impact of socioeconomic status on diurnal cortisol slope. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:91–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samieri C, et al. Association of cardiovascular health level in older age with cognitive decline and incident dementia. JAMA. 2018;320(7):657–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ironson G, et al. Positive emotional well-being, health behaviors, and inflammation measured by C-Reactive protein. Soc Sci Med. 2018;197:235–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darweesh SK, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(11):1450–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim HJ, et al. Trajectories of life satisfaction and their predictors among Korean older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho D, Cheon W. Older adults’ advance aging and life satisfaction levels: effects of lifestyles and health capabilities. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023;13(4):293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arce Rentería M, et al. Representativeness of samples enrolled in Alzheimer’s disease research centers. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2023;15(2):e12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung F, Lucas RE. Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: results from three large samples. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(10):2809–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobau R, et al. Well-being assessment: An evaluation of well-being scales for public health and population estimates of well-being among US adults. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2010;2(3):272–97. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karakose S, et al. Life events and incident dementia: a prospective study of 493,787 individuals over 16 years. J Gerontol: Ser B. 2024;79:gbae114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The NACC data are available to researchers who apply with a NACC data request (https://naccdata.org/requesting-data/data-request-process). Key elements of the application include a research plan, the goal of the analysis using NACC data, and a listing of requested variables.