Abstract

Endothelial dysfunction is one of the early triggers of vascular remodeling during pulmonary hypertension (PH) with complex predisposing mechanisms, mainly via an unbalanced generation of vasoactive factors, increased expression of growth factors, prothrombotic elements, and inflammatory markers. Conventional treatment regimens are restricted to a single therapeutic pathway, which usually leads to limited clinical outcomes. Combination therapies targeting multiple cells and several signaling pathways are increasingly adopted in PH treatment. Herein, inspired by the cocrystal pleomorphism theory, we prepared rod-shaped nanococrystals of the endothelin-1 (ET-1) receptor antagonist (bosentan, BST) and the anti-inflammatory drug (andrographolide, AG) for targeting the pulmonary endothelium and alleviating PH. The 525 nm-sized co-delivery system displayed a rod-like morphology, preferentially accumulated in the pulmonary endothelium and alleviated pulmonary artery (PA) remodeling. A three-week treatment with the preparation significantly alleviated the monocrotaline (MCT)- or Sugen 5416/hypoxia (SuHx)-induced PH by reducing the pulmonary artery pressure, increasing the survival rate, improving the hemodynamics, and inhibiting vascular remodeling. Mechanistically, the nanococrystals collaboratively repaired endothelial dysfunction by suppressing the pathways of ET-1/NF-κB/ICAM-1/TNF-α/IL-6. In conclusion, the cocrystal-based strategy offers a promising approach for constructing co-delivery systems. The developed rod-shaped nanococrystals effectively target the pulmonary endothelium and relieve experimental PH.

Key words: Pulmonary hypertension, Inflammation, Endothelial dysfunction, Endothelin, Cocrystals, Nanorods, Bosentan, Andrographolide

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a progressive and fatal cardiopulmonary disorder characterized by hyperproliferative and apoptosis-resistant pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), pulmonary adventitial fibrosis, endothelial dysfunction, and sustained inflammation1,2. Endothelial dysfunction is thought to be one of the early triggers of vascular remodeling, mainly via an unbalanced generation of vasoactive factors and increased expression of growth factors and inflammatory markers3,4. Existing PH therapies primarily aim to restore the mismatched production of vasoconstrictive/vasodilatory factors, dilate pulmonary vessels, and reduce pulmonary artery pressure5. However, few therapies are directed against the dysfunctional and proinflammatory endothelium.

Pulmonary endothelium dysfunction is narrowly linked to the upregulation of endothelin-1 (ET-1), a potent endogenous vasoconstrictor mainly produced by pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs)6,7. ET-1 works via the two ET-1 receptors, endothelin A/B receptors (ETA/B). ETA/B are expressed on PASMCs, while only ETB is present on PAECs6. Besides, ET-1 has been found to activate the NF-κB signaling pathway, contributing to inflammation and endothelial dysfunction8,9. Notably, the upregulation of the NF-κB in PH murine models and PAECs of PH patients has been frequently reported10, 11, 12, 13. Meanwhile, NF-κB knockdown reduces ET-1 secretion14; in contrast, strengthening the pathway upregulates ET-1 in various cell types15.

BST is an ET-1 receptor antagonist approved as the first oral drug against PH in 2001. However, clinical studies demonstrated that single BST treatment often led to an insufficient therapeutic remission rate and significantly reduced therapeutic efficacy for long-term medication16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. AG, a diterpenoid lactone isolated from the plant Andrographis paniculate, has been widely studied as a potent anti-inflammatory agent due to its NF-κB inhibitory action22, 23, 24, 25. Therefore, we propose that combining BST and AG is promising in restoring pulmonary endothelial dysfunction and improving PH treatment.

However, both BST and AG are poorly water-soluble drugs with distinct physicochemical properties, different administration routes, and non-similar in vivo behaviors26,27. Nanocrystals are commonly implemented to improve the physicochemical properties of sparingly soluble drugs, such as solubility, and endow them with superior pharmacokinetic properties28,29. In contrast to other particle carriers (e.g., polymer nanoparticles (NPs) and liposomes), nanocrystals are made only from pure drug crystals and possess a high loading capacity and reduced toxicity30, 31, 32. Nanocrystal engineering is drawing increasing attention to improving drug efficacy due to their promising translation perspectives. Over 20 nano/microcrystal productions were approved for clinical use33. Drug cocrystallization, utilizing more than one therapeutic agent, represents a promising approach for combination therapies, especially for complex diseases. Drug cocrystal offers potential synergistic and/or additive effects, alongside improvements in physicochemical properties, without requiring any chemical modification34,35. Additionally, previous findings indicated that rod-like particles prefer to accumulate in pulmonary vessels30,36. According to the cocrystal pleomorphism theory, two active compounds could assemble into specific-shaped nanococrystals at a fixed ratio, likely through hydrophobic interactions or hydrogen bonds37. Accordingly, we assumed that BST and AG could assemble into rod-shaped nanococrystals at a specific ratio, termed “BST-AG nanorods (NRs)”, effectively restoring pulmonary endothelial dysfunction for PH treatment (Fig. 1). Herein, we studied the two drugs’ assembly ability and capacity to target the pulmonary endothelium. Also, the therapeutic efficiency of the preparation against PH was proved both in vitro and in vivo. The NRs could efficiently target the pulmonary endothelium, reverse the endothelial dysfunction by reducing the production of ET-1 and proinflammatory factors, alleviate pulmonary artery (PA) remodeling and ameliorate PH in the MCT and Sugen 5416/hypoxia models.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the preparation and expected action of codelivery BST-AG NRs. After i.v. administration, the NRs accumulate within the pulmonary artery (PA) and endothelium, enter ECs and release the two drugs. BST blocks the fixation of ET-1 and prevents its pro-inflammatory action. Meanwhile, AG inhibits the NF-κB pathway and downregulates ET-1 and pro-inflammatory factors, restoring endothelial function, ultimately alleviating PA remodeling and ameliorating pulmonary hypertension (PH).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Andrographolide was purchased from Pufeide Biotech (Chengdu, China) and bosentan hydrate from Adamas-Beta (Shanghai, China). Bovine serum albumin (BSA), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), FITC, monocrotaline (MCT), and Sugen 5416 (SU5416) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). DAPI was provided by Solarbio Life Sciences (Beijing, China) and DiR by Shanghai Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai, China). ET-1, IL-6, and TNF-α ELISA kits were procured from Cloud-Clone (Wuhan, China). Antibodies against phosphorylated NF-κB p65, NF-κB p65, α-SMA, and Ki67, were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, USA). BCA protein assay kit, Lyso-Tracker Red, Matrix-Gel™ (Standard), and β-actin antibodies were obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Anti-ICAM-1 and CoraLite 594-labeled antibodies were purchased from Proteintech (Wuhan, China).

2.2. Preparation

BST-AG NRs were prepared using antisolvent precipitation and ultrasonication method using 0.1% BSA (pH = 7.4) as a stabilizer. Briefly, the BSA antisolvent solution was prepared. Then, the two drugs, BST and AG, with different mass ratios, were co-dissolved in 0.1 mL of the organic solvent (DMSO) and poured into 5 mL of the antisolvent solution. Immediately after antisolvent precipitation, the suspension was sonicated with an ultrasonic probe sonicator (20–25 kHz Scientz Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at 350 W for 20 min in an ice bath. Next, nanoparticles were collected by centrifugation and redispersion cycles 3 times to remove the stabilizer residue or any free drug using an ultrafiltration tube. DiR-NRs or FITC-NRs were prepared similarly by co-dissolving the dye with the drugs in the organic phase.

2.3. Cell culture

Human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAECs, ScienCell, San Diego, USA) were cultured in endothelial cell-specific medium (ECM, U.S. Sciencell, San Diego, USA) supplemented with 5% FBS, 1% endothelial cell growth factor, and 100 U/mL penicillin + 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Cells were detached by trypsin and centrifuged at 300×g for 5 min. All the experiments were conducted while the cells were between the 3rd and 5th passages.

2.4. Cell experiments

HPAECs were cultured in 12-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well) for 24 h at 37 °C. Then, cells were treated with FITC-NRs for 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h at 37 °C at different FITC concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 μg/mL. Next, cells were washed, detached by trypsin, and centrifuged (1500×g for 5 min). The fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry (FACS Calibur, BD Biosciences, USA). HPAECs were cultured in 10 mm2 glass bottom culture dishes (2 × 105 cells/dish) for 24 h at 37 °C. Then, the cells were incubated with FITC-NRs at FITC concentration of 5 μg/mL for 1, 2, 4, and 6 h, washed with ice-cold PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and incubated with DAPI (10 μg/mL) for 10 min. Cells were subsequently observed under LSM700 confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Zeiss, Germany).

For the investigation of the cellular entry mechanism, cells were pretreated with different endocytosis inhibitors, including chlorpromazine (CPZ, 10 μg/mL), nystatin (10 μmol/L), methyl-β-cyclodextrin (M-β-CD, 2.5 mmol/L), and nocodazole (20 μmol/L) for 30 min at 37 °C before incubation with 5 μg/mL of FITC-NRs for 6 h. The cells were labeled with Lyso-Tracker Red to observe the entrapment within lysosomes. Finally, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry or observed under CLSM.

For the study of tube formation, cells were pretreated with different formulations for 24 h, followed by incubation with 50 μL of Matrix-Gel at 37 °C for 1 h, exposure to LPS (5 μg/mL) for 4 h, and observation under an inverted microscope at × 100 magnification. Tube formation was assessed using ImageJ software.

2.5. Animals and the establishment of PH models

Male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats weighing 200–250 g, purchased from Nanjing Qinlong Animal Center (Nanjing, China), were used in the experiments. The animals used in all experiments followed the principles of laboratory animal care and the guide for the care and use of the laboratory, as well as the China Pharmaceutical University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (No. 202203002). Rats were housed at a temperature of 25 °C and a light/dark cycle of 12/12 h with free access to food and water. The MCT model was induced by a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of MCT solution (60 mg/kg). The Sugen 5416/hypoxia (SuHx) model was induced by the administration of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor SU5416 (20 mg/kg) and a three-week period of hypoxic exposure (10% oxygen), followed by 2 weeks of normoxic conditions before initiating the treatment. Wild-type (WT) rats, used as negative controls, were intraperitoneally injected with an equal volume of saline 0.9%. The established models were confirmed by echocardiography.

2.6. Pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies

At predetermined time points after i.v. administration of BST-AG NRs or the physical mixture, orbital blood was collected and centrifuged at 1500×g for 10 min. Additionally, tissues of interest (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) were resected at different times, rinsed, weighed, and homogenized in PBS. Drug concentrations were determined by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC‒MS/MS), as previously reported38,39. Briefly, after plasma protein precipitation with acetonitrile, chromatographic separation was achieved on a C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm) using an acetonitrile-0.1% formic acid mixture as the mobile phase, with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min at 40 °C for BST, and detected in positive-ion mode via electrospray ionization. For AG, the separation was achieved with a methanol–water (70:30 v/v) mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min and 30 °C with detection in negative-ion mode. The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using Phoenix WinNonlin 8.1. For ex vivo imaging, rats were sacrificed 24 h after the i.v. injection of DiR preparations at a DiR dose of 1.5 mg/kg and their major organs were harvested. The mean fluorescence intensity of the collected samples was measured using an in vivo imaging system (In-Vivo FX PRO, Carestream, Canada) with an excitation wavelength of 768 nm and an emission wavelength of 789 nm.

2.7. Pulmonary-endothelium targeting

At 4 h after the i.v. injection of free FITC or FITC-labeled NRs at FITC dose of 1 mg/kg, rats were sacrificed and their lungs were harvested. Then, the lung sections (∼3 μm) were washed with PBS and incubated with a blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Next, anti-CD31 primary antibodies (1:500) were added and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, CoraLite 594-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:200) were added and the sections were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, samples were analyzed using Olympus VS200 slide scanner (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

2.8. Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed under a Vevo 3100 LT ultrasound imaging system (VisualSonics Inc., ON, Canada) using parasternal short axis, long axis, and apical 4-chamber views. Pulse-wave Doppler echosonography was performed to record the PA flow at the level of the aortic valve in the parasternal short-axis view to measure pulmonary acceleration time (PAT), pulmonary ejection time (PET), and the ratio PAT/PET. Right ventricular internal diameter (RVID) and right ventricular free wall thickness (RVFWT) were measured during end-diastole using the M-mode of the parasternal long-axis views. Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) was recorded in 2D M-mode echocardiograms from the apical 4-chamber view. Cardiac output and ejection fraction of the left ventricle (LV) were also recorded using M-mode to assess LV function.

2.9. Open-chest hemodynamic and right ventricular hypertrophy measurements

Pulmonary hemodynamic parameters were measured in the open chest by inserting a polyethylene catheter (PE 50) filled with heparinized saline (7 units/mL) into the right ventricle (RV) and then advancing the catheter connected to a pressure transducer into the PA trunk. The right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) and mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) were recorded. Measurements were made using a polygraph (Powerlab, AD Instruments, USA). Ultimately, rats were sacrificed to collect major organs, which were snap-frozen and maintained at −80 °C until further analysis.

The harvested hearts were dissected into the RV and LV plus interventricular septum (S), and weighed separately to determine the right ventricular hypertrophy index (RVHI), which is expressed as the ratio of RV weight to the sum of LV and S weight.

2.10. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

The tissues collected from all the experimental groups were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin for histologic evaluation. The tissue sections (3–5 μm) were stained with H&E and observed under an optical microscope (Olympus, DP27, Hachioji, Japan) at × 200 magnification. Pulmonary vascular remodeling was assessed by estimating the external and internal diameters, lumen, and total vessel areas of over 10 randomly chosen vessels per animal. Then, the ratios of pulmonary vascular wall thickness and wall area were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2):

| Vascular wall thickness (%) = (Outer diameter – Inner diameter)/Outer diameter × 100 | (1) |

| Vascular wall area (%) = (Total vessel area – Lumen area)/Total vessel area × 100 | (2) |

Additionally, the average cross-sectional area per cardiomyocyte was measured using ImageJ software to evaluate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

2.11. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The paraffin-embedded lung sections (∼3 μm) were dewaxed, rehydrated, and treated with peroxidase blocking solution for 10 min at room temperature to inhibit the activity of endogenous peroxidases. Next, the slides were blocked with serum for 10 min at room temperature to inhibit non-specific binding. Subsequently, the tissues were incubated with anti-α-SMA primary antibodies (1:200) or anti-Ki67 primary antibodies (1:1000) overnight at 4 °C, washed with PBS, and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were observed under the microscope and vessels with a diameter < 100 μm in 10 fields of view were selected. The brown parts were considered the α-SMA or Ki67 positive areas.

2.12. Western blotting

The frozen lungs were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer containing 1 μL PMSF inhibitor using a glass homogenizer on ice. Lung homogenates were then sonicated and centrifuged at 15,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C for further use. The total protein concentrations were measured using a BCA protein assay kit. Briefly, aliquots of proteins (30 μg) were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a PVDF membrane at 300 mA for 1.5 h. The protein-loaded membranes were then blocked for 10 min using a blocking buffer at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with 1:1000 diluted primary antibodies. Then, the membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the peroxidase activity was detected using an ECL chemiluminescence kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), imaged under a ChemiDoc platform (Bio-RAD, CA, USA), and analyzed by Image Lab 5.1 (Bio-RAD, CA, USA).

2.13. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). One-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA analysis were used to assess the statistical significance of the differences between the groups. All results were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and characterization

First, we investigated the synergistic effect of the two drugs on downregulating the proinflammatory TNF-α using SynergyFinder, in which the positive and negative scores indicate synergy and antagonism, respectively (See Supporting Information). All the scores of studied ratios are positive values (Supporting Information Fig. S1), indicating that the two drugs could work collaboratively.

Then, we prepared BST-AG NRs using the antisolvent precipitation-ultrasonication method and BSA as a stabilizer. The formulation was optimized by changing the BST/AG mass ratio from 1:1 to 1:5 (Fig. 2A). The 1:3 ratio was selected as the optimized formulation for the subsequent studies because it offers a balance between size, loading capacity, and suitability for intravenous injection and pulmonary-endothelium targeting. Unlike the 1:1 and 1:5 ratios, which proved too large, the 1:3 ratio exhibited favorable characteristics in both size and PDI. Furthermore, the combination 1:3 had a superior synergy score (Fig. S1). The entrapment efficiencies in the formulation were approximately 87% with a drug-loading of 20.5% for BST and 86% with a drug-loading of 54.2% for AG. The NRs displayed a size of 525 nm in length, negative charge (−10.4 ± 2.2 mV), and rod-like morphology (Fig. 2B). PXRD test showed that the lyophilized NRs had a crystalline state (Fig. 2C). The incorporation of AG and BST led to a fluorescence quenching revealing the interaction between BSA and the drug crystals (Supporting Information Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Preparation and characterization of BST-AG NRs. (A) Effect of the BST:AG mass ratio on the particle size and PDI of the NRs (n = 3). (B) TEM image. Scale bar = 500 nm. (C) PXRD assay. BST and AG exhibited distinct sharp peaks between 5° and 40°. The physical mixture displayed typical peaks from the two drugs. The NRs displayed similar peaks as the physical mixture, suggesting that both drugs preserved their crystalline state. (D) Schematic illustration of the drug's assembly mode. BST is presented by sticks, and AG is presented by balls and sticks. The green lines indicate hydrogen bonds, and the black lines represent the hydrophobic bonds with their respective distance (Å). UV–Vis absorbance of NRs or the physical mixture in the presence and absence of (E) DMSO, (F) SDS (0.2%, w/v), and (G) NaCl. (H) Serum stability of the NRs in terms of particle size (nm) and PDI in PBS (pH 7.4) and PBS (pH 7.4) + 10% FBS (n = 3). (I) In vitro drug release from the NRs under pH 7.4 for 24 h (n = 3). Coomassie staining of (J) BSA-free NRs and (K) BSA-NRs before and after incubation with 10% FBS (v/v) at 37 °C. (L) Quantitative analysis of protein corona (PC) adsorbed on the NRs evaluated by bicinchoninic acid assay. The data are given as mean ± SD, n = 3. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, compared to the control group.

To illustrate the cocrystal formation mechanism, we initially conducted an FTIR examination (Supporting Information Fig. S3). The FTIR spectrum of the physical mixture was more similar to the AG spectrum due to the higher mass ratio of AG in the blend (1:3) without shift or apparition of new bands. The formation of NRs led to the change of O–H stretching of BST from 3625 to 3678 cm−1. Also, the C–O stretching of AG recorded at 1219 and 1031 cm−1 shifted to 1247 and 1011 cm−1. These changes are probably due to the formation of hydrogen bonds that might be the main driving force of the two drugs’ assembly. Then, we conducted molecular docking to gain an in-depth insight into the intermolecular interactions between the self-assembled drugs. The binding energy of interactions between AG and BST was −3.9 kcal/mol, with 6 intermolecular interactions detected, including hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds (Fig. 2D). Further, UV–Vis absorbance of NRs was similar to the free drugs dissolved in DMSO and 0.2% SDS, implying the absence of π–π stacking and hydrophobic force (Fig. 2E and F). In contrast, the spectrum of NRs exhibited a red shift and an absorption enhancement in 0.25 mol/L NaCl, indicating the destruction of intermolecular interactions, likely hydrogen bonds formed between the partially negative N or O atoms and partially positive hydrogen atoms (Fig. 2G). The results imply that hydrogen bonds are probably the main driving force of self-assembly.

The stability examination demonstrated that BST-AG NRs were stable against aggregation or sedimentation after 48-h incubation in 10% serum PBS (Fig. 2H). The release study displayed that about 60% of BST and AG were released from BST-AG NRs at 12 h, with an initial burst release of 30% within the first 1 h. Then, the release was continued, but the cumulative release was less than 70% after 24 h for both BST and AG, indicating a sustained and synchronous release profile of the two drugs (Fig. 2I).

Finally, we studied the hemotoxicity and protein corona of the NRs. The NR incubation demonstrated less than 5% hemolysis rate (3.5%) as the BST concentration ranged from 0 to 300 μg/mL (Supporting Information Fig. S4). The data indicated that i.v. administration of the NRs is safe. The attachment of various biomolecules to the nanoparticle surface may influence their circulation, stability, toxicity, and cellular uptake40. The incubation with FBS allowed the NRs to display several bands (Fig. 2J‒K, Supporting Information Fig. S5); however, the most detectable band was about 65 kDa (BSA). The quantification revealed that fewer proteins were adsorbed to the NRs due to BSA coating (P < 0.01 at 72-h incubation, Fig. 2L). The data suggest the beneficial effect of BSA coating in reducing the interaction with blood proteins, in addition to its role as a steric stabilizer.

3.2. Cellular uptake and attenuation of endothelial dysfunction in vitro

As displayed in the Supporting Information Fig. S6, the internalization of BST-AG NRs occurred in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. To investigate the internalization mechanism, we studied the endocytosis using the inhibitors of CPZ, nystatin, M-β-CD, and nocodazole, which suppress clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolin/cholesterol-dependent internalization, and microtubule-related-internalization, respectively41. Pretreatment with nystatin or M-β-CD significantly reduced the NRs’ uptake, demonstrating that nanoparticles were predominantly internalized via caveolin- and cholesterol-dependent endocytosis. Consistently, CLSM images revealed a remarkable reduction in green fluorescence after the pretreatment, confirming the involvement of the endocytosis pathway. The caveolin/cholesterol internalization allows intracellular delivery by bypassing the endo-lysosomes31. An additional CLSM study indicated that FITC-NRs had little colocalization with the endo-lysosomes (Supporting Information Fig. S7). The data revealed that the cellular uptake of NRs primarily occurred through a non-endo-lysosomal route.

The endothelial dysfunction characterized by the upregulation of ET-1 and proinflammatory factors is one of the critical hallmarks observed during PH3. For the in vitro studies, LPS was used to simulate the proinflammatory endothelial phenotype of PH42, 43, 44, 45. The incubation with free BST-AG and BST-AG NRs significantly reduced ET-1 compared to the LPS-induced positive control (Fig. 3A and B, P < 0.05, P < 0.01). The two preparations also decreased the tube number (Supporting Information Figs. S8A and S8B, P < 0.01, P < 0.01), demonstrating a change in the endothelial phenotype. Increased ICAM-1 expression could reduce the function of the endothelial barrier and cell junctions46,47. The treatment using AG-containing preparations allowed significant ICAM-1 reduction (Fig. 3E and G, P < 0.05, P < 0.01). Furthermore, the NRs more profoundly declined the proinflammatory factors, IL-6 and TNF-α (Fig. 3C and D, P < 0.01). Subsequently, the involvement of the NF-κB signaling pathway was investigated. Dosing with AG-containing preparations, free AG, free BST-AG and NRs, downregulated NF-κB p65 (Fig. 3E and F, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001). However, only NR treatment significantly increased the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein (Bax) (Fig. S8C). Collectively, the NRs were the most efficient in restoring endothelial functions in vitro due to the improved intracellular drug delivery.

Figure 3.

In vitro effect of the preparations on endothelium dysfunction. (A) ET-1 level after activating HPAECs using different LPS concentrations (0, 5, 10 μg/mL) for 24 h. (B) The increase in ET-1 levels after 24 h treatment with different preparations at a BST dose of 6 μmol/L and AG dose of 30 μmol/L. (C) IL-6 and (D) TNF-α levels. ET-1, IL-6, and TNF-α were measured using ELISA kits following the manufacturer's instructions. (E) WB bands of p–NF–κB-p65 and ICAM-1. Semi-quantitative analysis of (F) p–NF–κB-p65 and (G) ICAM-1. The data are given as mean ± SD, n = 3. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, compared to the PBS group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, compared to the LPS group. &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, compared to NRs group. ns, not significant.

3.3. Improved pharmacokinetic behavior, biodistribution, and pulmonary-endothelium targeting

Pharmacokinetic studies of the nanoparticles were performed by i.v. injection of free BST-AG and NRs in the MCT-induced animal model. The plasma concentration of the two drugs was measured by LC‒MS/MS. The plasma concentrations of the two drugs in the NRs were higher for 8 h over the free combination (Supporting Information Fig. S9). BST incorporated into NRs displayed a 1.5-fold prolongation of half-life, a 3.5-fold augmentation of the area under the curve (AUC), and a 3.5-fold decrease in clearance compared to the physical mixture (Table 1). Likewise, there was a 1.8-fold extension of half-life, a 2.3-fold increase in AUC, and a 2.3-fold reduction in clearance of AG loaded into NRs compared to the free formulation. These results indicate that the NRs improved the pharmacokinetic behavior of the two drugs.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of BST and AG in NRs and physical mixture formulations (free BST-AG) after i.v. injection in rats at a BST dose of 5 mg/kg and AG dose of 15 mg/kg.

| Parameter | t1/2 (h) | AUC0-∞ (h·μg/mL) | MRT0‒∞ (h) | Vd (L/kg) | CL (L/h/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free BST | 1.40 ± 0.1 | 4.07 ± 2.1 | 1.62 ± 0.4 | 1.99 ± 0.3 | 1.22 ± 0.3 |

| BST-NRs | 2.16 ± 0.4∗∗ | 14.19 ± 3.4∗∗∗ | 2.80 ± 0.6∗∗ | 0.98 ± 0.5∗∗ | 0.35 ± 0.2∗∗ |

| Free AG | 1.84 ± 0.3 | 18.76 ± 5.6 | 2.41 ± 0.7 | 1.93 ± 0.4 | 0.79 ± 0.1 |

| AG-NRs | 3.21 ± 0.5∗∗∗ | 43.94 ± 7.3∗∗∗ | 3.76 ± 0.6∗ | 1.29 ± 0.5ns | 0.34 ± 0.1∗∗∗ |

AUC, the area under the curve; MRT, mean residence time; CL, clearance rate; Vd, volume of distribution. The data are given as mean ± SD, n = 6. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, compared to the free groups. ns, not significant.

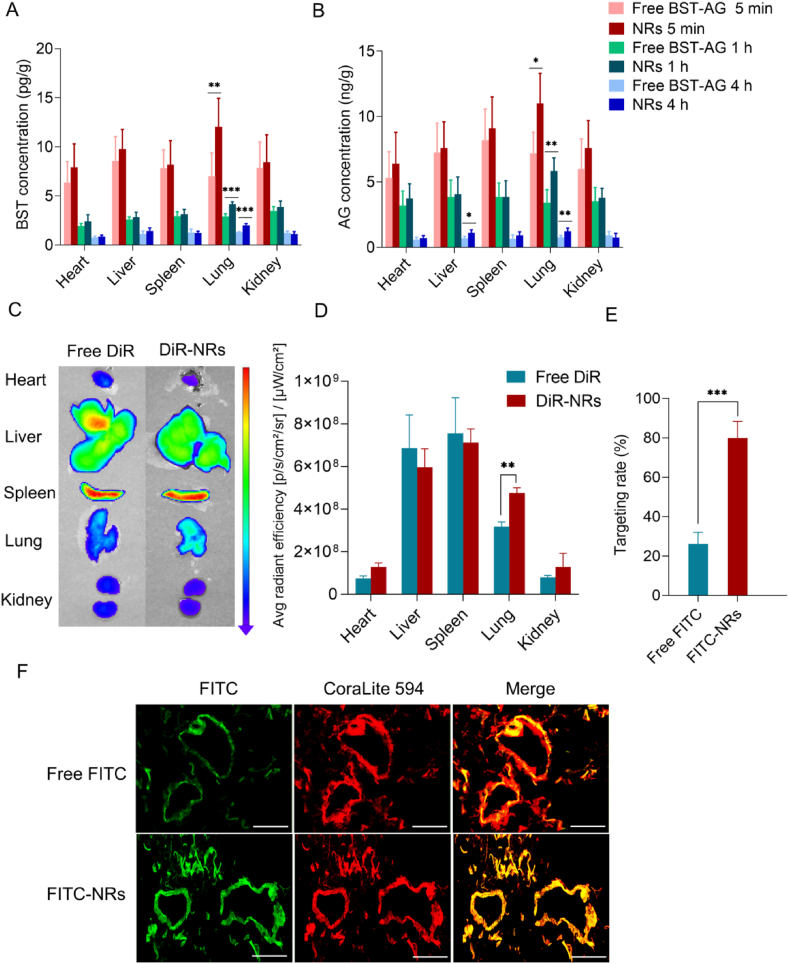

Next, we examined drug biodistribution after injecting the two preparations. The drugs in the two formulations accumulated similarly in the heart, spleen, and kidneys. However, the BST and AG pulmonary concentrations from the NRs were significantly higher than free BST-AG at 5 min, 1 and 4 h post-injection (Fig. 4A and B, P < 0.01, P < 0.001). Consistently, the DiR-NRs’ fluorescence intensity in the lung was significantly higher (1.5 times) than the free dye, indicating an enhanced pulmonary distribution (Fig. 4C and D, P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Biodistribution and pulmonary-endothelium targeting. Biodistribution of (A) BST and (B) AG in different tissues evaluated through LC‒MS/MS at different time points (n = 6). (C) Ex vivo fluorescence images of major organs and (D) semi-quantitative biodistribution of free DiR or DiR-NRs at 24 h post-injection determined by the average radiant efficiency [p/s/cm2/sr]/[μW/cm2] of each organ. The rats were i.v. injected with free DiR or DiR-NRs at a dose of 1.5 mg DiR/kg. (E) Quantified assay of free FITC or FITC-NRs targeting rate and (F) immunofluorescence images showing the colocalization of FITC-labeled NRs (green fluorescence) with CD31 (dilution 1:500, labeled with CoraLite 594 secondary antibodies, red fluorescence). The data are shown as mean ± SD (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001). The rats were i.v. injected with free FITC or FITC-labeled NRs at a single FITC dose of 1 mg/kg. At 4 h post-administration, the rats were sacrificed and the lungs were harvested for fluorescence imaging. Yellow fluorescence indicates colocalization. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Finally, we evaluated NR accumulation in the pulmonary endothelium by colocalizing FITC-BST-AG NRs with the endothelium marker CD31. Yellow fluorescence spots appeared in the merged image and indicated the colocalization (Fig. 4F). Importantly, the accumulation of FITC-NRs increased by approximately 3-fold compared to free FITC (Fig. 4E, P < 0.001). These results demonstrate that BST-AG NRs could target the pulmonary endothelium.

3.4. Ameliorated MCT- and SuHx-induced experimental PH

First, we assessed the treatment efficacy of preparations in the MCT-induced model. The 3-week treatment with combined preparations, free BST-AG or NRs, elevated the rats’ survival rates (Fig. 5A and B). At the end of treatment, we assessed RVSP and mPAP. Remarkably, combining the two drugs in the free mixture or NRs resulted in a more effective reduction of RVSP and mPAP than their monotherapies (Fig. 5C and D). The NR-treated group displayed a maximal decrease of 49% (P < 0.001) in RVSP and 47% (P < 0.001) in mPAP, compared to the model. The data suggest that intravenous injection of BST-AG NRs allowed an effective decline in RVSP and mPAP.

Figure 5.

Therapeutic efficiency in the MCT rat model. (A) Therapeutic schedule. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves, (C) RVSP, (D) mPAP. (E) Echocardiography images of MCT rat model. Pulsed wave Doppler: Pulsed wave Doppler echography. Semi-quantitative echocardiographic data of (F) the PAT/PET ratio and (G) TAPSE. Semi-quantitative analysis of pulmonary vascular (H) wall thickness and (I) wall area. (J) H&E images of paraffin-embedded lung sections. Nuclei are stained in blue while the cytoplasm and extracellular matrix are stained red. (K) Representative IHC images and (L) semi-quantitative analysis of α-SMA expression in the pulmonary vessels. The brown spots represent the positive area. Scale bar = 50 μm. The rats were intravenously injected every 3 days for 3 weeks at a BST dose of 5 mg/kg and AG dose of 15 mg/kg. The data are given as mean ± SD, n = 6. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, compared to the WT group (normal animals). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, compared to the MCT group. &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, &&&P < 0.001, compared to NRs group. ns, not significant.

Next, we assessed the RV functions using echocardiography. The PAT/PET ratio and TAPSE are essential parameters that reflect the RV afterload48,49. Again, BST-AG NRs increased the PAT/PET ratio and TAPSE, while other preparations demonstrated modest effects (Fig. 5E‒G, P < 0.01, P < 0.001). Similarly, treatment with BST-AG NRs reduced RVID (P < 0.01) and RVFWT (P < 0.01) while it increased the LV cardiac output (Supporting Information Fig. S10A‒S10E, P < 0.05). Additionally, BST-AG NRs decreased the cross-sectional area and RVHI to a similar level as the control groups (Fig. S10F‒S10H, P < 0.05). These data suggest that NRs attenuated RV remodeling effectively.

We investigated the PA remodeling after a 3-week treatment in the MCT-induced model. The vascular wall thickness (%) and wall area (%) noticeably increased in the non-treated groups. Among the preparations, only the NR treatment significantly reduced vascular wall thickness (%) and wall area (%) compared to the model group (Fig. 5H‒J, P < 0.01). Moreover, we determined the indicator α-SMA to assess the PA muscularization (Fig. 5K). The α-SMA expression increased in the MCT model compared to the WT group (P < 0.001). Combined treatment using the free mixture or NRs reduced the α-SMA expression compared to the model group (Fig. 5L, P < 0.05, P < 0.001).

Finally, we tested different formulations' anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects in lung tissue. As displayed in the Supporting Information Fig. S11, free drugs alone or in combination inhibited the MCT-induced proliferation without significance compared to the model group, whereas NRs lowered the proliferation significantly (P < 0.05) in the model. Consistent with the lowest proliferation rate obtained in the NRs group, the maximum augmentation of TUNEL-positive cell rates in the lungs of PH rats was induced by BST-AG NRs treatment (P < 0.001), indicating elevated apoptosis. As expected, repeated administration of the NRs demonstrated little histopathological alteration in major organs compared to the WT group, indicating the safety (Supporting Information Fig. S12).

In addition, the therapeutic efficacy of BST-AG NRs was investigated in the SuHx PH model induced by SU5416 combined with 3 weeks of hypoxic conditions (Fig. 6A). The treatment using NRs could alleviate the PH in the model, e.g., improving cardiopulmonary hemodynamics (Fig. 6B‒D and F, Supporting Information Fig. S13, P < 0.05), reducing PA remodeling and proliferation (Fig. 6G‒I, Supporting Information Fig. S14, P < 0.05), although the effect on indicators such as PAT/PET ratio (Fig. 6E) and α-SMA (Fig. 6J and K) is not profound as the MCT model.

Figure 6.

Therapeutic efficiency in the SuHx rat model. (A) Therapeutic schedule. (B) RVSP, (C) mPAP. (D) Echocardiography images of SuHx rat model. Semi-quantitative echocardiographic data of (E) the PAT/PET ratio and (F) TAPSE. Semi-quantitative analysis of pulmonary vascular (G) wall thickness and (H) wall area. (I) H&E images of paraffin-embedded lung sections. Nuclei are stained in blue while the cytoplasm and extracellular matrix are stained red. (J) Representative IHC images and (K) semi-quantitative analysis of α-SMA expression in the pulmonary vessels. The brown spots represent the positive area. Scale bar = 50 μm. The rats were intravenously injected every 3 days for 3 weeks at a BST dose of 5 mg/kg and AG dose of 15 mg/kg. The data are given as mean ± SD, n = 3. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, compared to the WT group (normal animals). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, compared to the SuHx group. ns, not significant.

Overall, the results indicated that treatment with BST-AG NRs could ameliorate experimental PH in MCT- and SuHx-induced models with higher efficacy than monotherapy by improving cardiopulmonary hemodynamics and reducing PA remodeling.

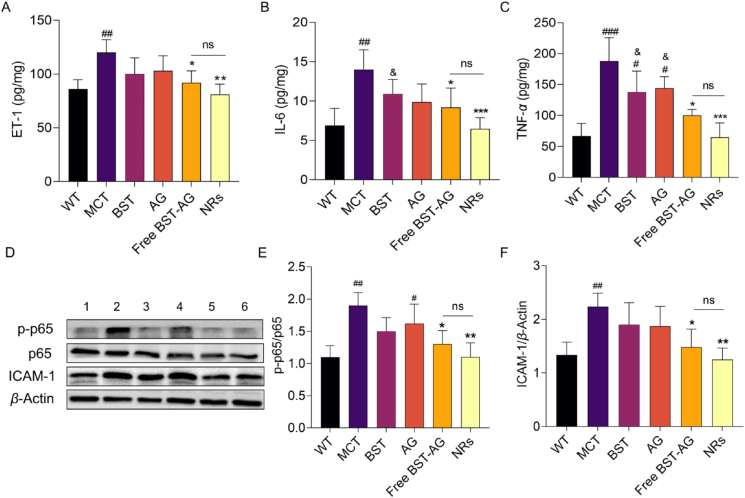

3.5. Mechanism study: strengthened endothelial function in vivo

PH is a progressive disease induced by pulmonary endothelium dysfunction and vascular remodeling. The endothelial function is crucially governed by various factors, such as ET-1, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), inflammation, deposition of extracellular matrix, and vascular remodeling6,45. Initially, we examined the pivotal marker of endothelium dysfunction, lung ET-1. As shown in Fig. 7A, ET-1 levels in the MCT model significantly increased compared to the control group (P < 0.01). BST and AG demonstrated a modest reduction of ET-1 compared to the model. Whereas the combination formulations, especially BST-AG NRs, significantly downregulated ET-1 (P < 0.01).

Figure 7.

Downregulated production of ET-1, proinflammatory factors, and NF-κB expression in the lungs. The (A) ET-1, (B) IL-6, and (C) TNF-α were measured by ELISA following the manufacturer's instructions. (D) WB bands of p–NF–κB-p65 and ICAM-1. Semi-quantitative analysis of (E) p–NF–κB-p65 and (F) ICAM-1. The rats were intravenously injected every 3 days for 3 weeks at a BST dose of 5 mg/kg and AG dose of 15 mg/kg. The data are given as mean ± SD, n = 6. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.01, compared to the WT group (normal animals). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.01, compared to the MCT group. &P < 0.05 compared to the NRs group. ns, not significant.

ET-1 expression is often related to the α-SMA expression on intima cells, potentially promoting EMT50,51. The BST-AG NRs therapy could efficiently repress the PH-induced α-SMA overexpression. ET-1 exacerbates inflammation through the axis of NF-κB/ICAM-1/TNF-α/IL-652, 53, 54. As depicted in Fig. 7B and C, the two inflammatory factors, IL-6 and TNF-α, were decreased after treatment using the combination of free BST-AG or NRs (P < 0.05, P < 0.001). Again, the NR-treated group displayed the most profound reduction of ICAM-1 among the treated groups (Fig. 7D and F, P < 0.01). Then, we measured the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 protein in the lung to confirm the involvement of the NF-κB pathway (Fig. 7D and E). Efficiently, BST-AG NRs reduced the protein expression compared to the model group (P < 0.01).

Taken together, we proved that BST-AG NRs could restore PH-related endothelial dysfunction by suppressing the ET-1/NF-κB/ICAM-1/TNF-α/IL-6 pathways.

4. Discussion

Combining therapies targeting multiple cells and several signaling pathways are increasingly adopted to treat PH5,55. In this work, we proposed a co-delivery platform with suitable properties for pulmonary endothelium-targeting to deliver the two poorly soluble drugs, BST and AG, as a potential combination against PH. Unlike other co-delivery preparations, the present co-delivery system, BST-AG NRs, mainly composed of drugs, exhibited high drug-loading of 20.5% for BST and 54.2% for AG (mass ratio 1:3), in contrast to most of the commonly studied nanoplatforms, such as lipid and polymer-based NPs, that suffer from low payload capacity (<10%, w/w)26,56,57. Moreover, the carrier-free platform is simply synthesized without crosslinkers or additional carrier materials, making them safe and cost-effective58. Additionally, insoluble drugs account for over 40% of drugs used in the clinic and 60% of new chemical entities59. According to the cocrystal theory, two active compounds could bond together with the assistance of supramolecular synthons and assemble into specific-shaped particles at a stoichiometric ratio via various noncovalent bonds, such as van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, and π–π stacking interactions37. Particle geometry significantly affects the in vivo fate, e.g., circulation, biodistribution, intracellular translocation, immune response, vessel flow performance, and targeting of specific tissues60. The study suggests that the hydrogen bonds might be the main driving force behind the assembly of the two drugs. We found that the co-delivery platform had a rod shape and efficiently targeted the pulmonary endothelium to synchronously co-deliver the two small drugs. As a result, two insoluble drug-assembled nanococrystals represent a universal strategy for constructing co-delivery systems.

The significant enhancement in the pulmonary distribution and pulmonary-endothelium targeting of BST-AG NRs could be ascribed to several factors. Large-sized NPs tend to accumulate in the pulmonary vessels better than their smaller counterparts61,62. The NP morphology also plays a critical role in their biodistribution. The anisotropic shape promotes adhesion to lung vasculature and endothelium penetration, owing to their higher contact area compared to same-sized spherical ones36,63, 64, 65. Furthermore, the caveolae-dependent endocytosis of nanorods favors their uptake by endothelium due to the high caveolin content in endothelial cells36,66, 67, 68. The large endothelial surface area of pulmonary vessels, constituting 1/3 of the total endothelial surface, further contributes to pulmonary vessel targeting69. After i.v. injection, pulmonary arterial capillaries are the first major obstacles to entrapping the NPs, thereby potentializing their targeting ability69.

Associating different PH therapeutics, such as ET-1 receptor antagonists and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, often increases the risk of drug–drug interactions and adverse effects, such as hypotension5,55. Combining therapies targeting different disease profiles, including vascular remodeling, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, seems promising. BST is a potent anti-PH drug reported to reduce PH-associated vascular remodeling, inflammation, and cardiac dysfunction16,70. The addition of AG to BST therapy, especially as a nanoscaled co-delivery platform, has significantly boosted the therapeutic effect against PH, as revealed by the enhanced survival rate, reversed vascular remodeling, restored endothelial function, and alleviated lung inflammation. The ameliorated PH is ascribed to the improved pharmacokinetics and lung biodistribution, pulmonary-endothelium targeting ability, and synergism between the two drugs.

Our data suggest that the beneficial effect of the BST-AG combination in reducing endothelial dysfunction is likely mediated by a synergistic action on the ET-1/NF-κB/ICAM-1/TNF-α/IL-6 pathways. The central and pleiotropic action of this axis in several diseases paves the way for associating endothelin-1 antagonists and anti-inflammatory drugs in various therapeutic applications, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, asthma, pulmonary fibrosis, and cancer71, 72, 73.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our study leverages the cocrystal approach to specifically co-deliver BST and AG to the pulmonary endothelium for alleviating experimental PH. The co-delivery system acted collaboratively by suppressing the pathways of ET-1/NF-κB/ICAM-1/TNF-α/IL-6. Promisingly, endothelial dysfunction is associated with several lung diseases besides PH. Therefore, our platform may hold benefits for restoring other lung disorders. Additionally, this nanococrystal-based strategy offers simplicity and controllability, facilitating reproducibility and scalability, thus promising a perspective for successful translation.

Author contribution

Makhloufi Zoulikha: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Jiahui Zou: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Pei Yang: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Jun Wu: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Wei Wu: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Kun Hao: Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Wei He: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82073782 and 82241002), the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (21KJA320003), the Scientific Research Project of Jiangsu Commission of Health (LKZ2023001, China), and the Clinical Competence Improvement Project of Jiangsu Province Hospital (JSPH-MB-2022-13, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2024.11.008.

Contributor Information

Kun Hao, Email: haokun@cpu.edu.cn.

Wei He, Email: weihe@cpu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following is the Supporting Information to this article:

References

- 1.Schermuly R.T., Ghofrani H.A., Wilkins M.R., Grimminger F. Mechanisms of disease: pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:443–455. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan R., Liu M., Cheng Y., Yan F., Zhu X., Zhou S., et al. Biomimetic nanoparticle-mediated target delivery of hypoxia-responsive plasmid of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 to reverse hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. ACS Nano. 2023;17:8204–8222. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurakula K., Smolders V.F.E.D., Tura-Ceide O., Wouter Jukema J., Quax P.H.A., Goumans M.J. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension: cause or consequence? Biomedicines. 2021;9:57. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9010057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranchoux B., Harvey L.D., Ayon R.J., Babicheva A., Bonnet S., Chan S.Y., et al. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension: an evolving landscape (2017 Grover Conference Series) Pulm Circ. 2018;8 doi: 10.1177/2045893217752912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lan N.S.H., Massam B.D., Kulkarni S.S., Lang C. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: pathophysiology and treatment. Diseases. 2018;6:38. doi: 10.3390/diseases6020038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Star G.P., Giovinazzo M., Lamoureux E., Langleben D. Effects of vascular endothelial growth factor on endothelin-1 production by human lung microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. Life Sci. 2014;118:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houde M., Desbiens L., D'Orléans-Juste P. Endothelin-1: biosynthesis, signaling and vasoreactivity. Adv Pharmacol. 2016;77:143–175. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sánchez A., Martínez P., Muñoz M., Benedito S., García-Sacristán A., Hernández M., et al. Endothelin-1 contributes to endothelial dysfunction and enhanced vasoconstriction through augmented superoxide production in penile arteries from insulin-resistant obese rats: role of ET(A) and ET(B) receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:5682–5695. doi: 10.1111/bph.12870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin L.J., Roux S. Bosentan: a dual endothelin receptor antagonist. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;11:991–1002. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.7.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosokawa S., Haraguchi G., Sasaki A., Arai H., Muto S., Itai A., et al. Pathophysiological roles of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in pulmonary arterial hypertension: effects of synthetic selective NF-κB inhibitor IMD-0354. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:35–43. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura S., Egashira K., Chen L., Nakano K., Iwata E., Miyagawa M., et al. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of nuclear factor κB decoy into lungs ameliorates monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;53:877–883. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.121418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price L.C., Caramori G., Perros F., Meng C., Gambaryan N., Dorfmuller P., et al. Nuclear factor κ-B is activated in the pulmonary vessels of patients with end-stage idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang D., Wang X., Chen S., Chen S., Yu W., Liu X., et al. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide sulfhydrates IKKβ at cysteine 179 to control pulmonary artery endothelial cell inflammation. Clin Sci. 2019;133:2045–2059. doi: 10.1042/CS20190514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel H., Zaghloul N., Lin K., Liu S.F., Miller E.J., Ahmed M. Hypoxia-induced activation of specific members of the NF-κB family and its relevance to pulmonary vascular remodeling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;92:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stow L.R., Jacobs M.E., Wingo C.S., Cain B.D. Endothelin-1 gene regulation. FASEB J. 2011;25:16–28. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-161612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beckmann T., Shelley P., Patel D., Vorla M., Kalra D.K. Strategizing drug therapies in pulmonary hypertension for improved outcomes. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15:1242. doi: 10.3390/ph15101242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coons J.C., Pogue K., Kolodziej A.R., Hirsch G.A., George M.P., Pogue K., et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension : a pharmacotherapeutic update. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21 doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bisserier M., Pradhan N., Hadri L. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches to pulmonary hypertension. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020;21:163–179. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.02.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee H.J., Kang J.H., Lee H.G., Kim D.W., Rhee Y.S., Kim J.Y., et al. Preparation and physicochemical characterization of spray-dried and jet-milled microparticles containing bosentan hydrate for dry powder inhalation aerosols. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:4017–4030. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S120356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin Q., Chen D., Zhang X., Zhang F., Zhong D., Lin D., et al. Medical management of pulmonary arterial hypertension: current approaches and investigational drugs. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:1579. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15061579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathai S.C., Girgis R.E., Fisher M.R., Champion H.C., Housten-Harris T., Zaiman A., et al. Addition of sildenafil to bosentan monotherapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:469–475. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00081706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shu J., Huang R., Tian Y., Liu Y., Zhu R., Shi G. Andrographolide protects against endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory response in rats with coronary heart disease by regulating PPAR and NF-κB signaling pathways. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:1965–1975. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgos R.A., Alarcón P., Quiroga J., Manosalva C., Hancke J. Andrographolide, an anti-inflammatory multitarget drug: all roads lead to cellular metabolism. Molecules. 2020;26:5. doi: 10.3390/molecules26010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai Q., Zhang W., Sun Y., Xu L., Wang M., Wang X., et al. Study on the mechanism of andrographolide activation. Front Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.977376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magar K.T., Boafo G.F., Zoulikha M., Jiang X., Li X., Xiao Q., et al. Metal phenolic network-stabilized nanocrystals of andrographolide to alleviate macrophage-mediated inflammation in-vitro. Chin Chem Lett. 2023;34 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giménez V.M., Sperandeo N., Faudone S., Kassuha D. Preparation and characterization of bosentan monohydrate/ε-polycaprolactone nanoparticles obtained by electrospraying. Biotechnol Prog. 2019;35 doi: 10.1002/btpr.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao G., Zeng Q., Zhang S., Zhong Y., Wang C. Effect of carrier lipophilicity and preparation method on the properties of andrographolide–solid dispersion. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11:74. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11020074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y., Lv Y., Li T. Hybrid drug nanocrystals. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;143:115–133. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammad I.S., Hu H., Yin L., He W. Drug nanocrystals: fabrication methods and promising therapeutic applications. Int J Pharm. 2019;562:187–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li B., Teng C., Yu H., Jiang X., Xing X., Jiang Q., et al. Alleviating experimental pulmonary hypertension via co-delivering FoxO1 stimulus and apoptosis activator to hyperproliferating pulmonary arteries. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:2369–2382. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du X., Hou Y., Huang J., Pang Y., Ruan C., Wu W., et al. Cytosolic delivery of the immunological adjuvant Poly I:C and cytotoxic drug crystals via a carrier-free strategy significantly amplifies immune response. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:3272–3285. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thapa Magar K., Boafo G.F., Li X., Chen Z., He W. Liposome-based delivery of biological drugs. Chin Chem Lett. 2022;33:587–596. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarvis M., Krishnan V., Mitragotri S. Nanocrystals: a perspective on translational research and clinical studies. Bioeng Transl Med. 2018;4:5–16. doi: 10.1002/btm2.10122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X., Du S., Zhang R., Jia X., Yang T., Zhang X. Drug-drug cocrystals: opportunities and challenges. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2021;16:307. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banerjee M., Nimkar K., Naik S., Patravale V. Unlocking the potential of drug-drug cocrystals–a comprehensive review. J Control Release. 2022;348:456–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teng C., Li B., Lin C., Xing X., Huang F., Yang Y., et al. Targeted delivery of baicalein-p53 complex to smooth muscle cells reverses pulmonary hypertension. J Control Release. 2022;341:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo M., Sun X., Chen J., Cai T. Pharmaceutical cocrystals: a review of preparations, physicochemical properties and applications. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:2537–2564. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen M., Song W., Wang S., Chen Q., Pan P., Xu T., et al. Simultaneous determination of bosentan, glimepiride, HYBOS and M1 in rat plasma by UPLC‒MS-MS and its application to pharmacokinetic study. J Chromatogr Sci. 2016;54:1159–1165. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmw003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu Y., Ma J., Liu Y., Chen B., Yao S. Determination of andrographolide in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;854:328–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao Q., Zoulikha M., Qiu M., Teng C., Lin C., Li X., et al. The effects of protein corona on in vivo fate of nanocarriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;186 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2022.114356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He W., Xing X., Wang X., Wu D., Wu W., Guo J., et al. Nanocarrier-mediated cytosolic delivery of biopharmaceuticals. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu Y.C., Yeh W.C., Ohashi P.S. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine. 2008;42:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dauphinee S.M., Karsan A. Lipopolysaccharide signaling in endothelial cells. Lab Invest. 2006;86:9–22. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shao D., Park J.E.S., Wort S.J. The role of endothelin-1 in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhaun N., Webb D.J. Endothelins in cardiovascular biology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16:491–502. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark P.R., Manes T.D., Pober J.S., Kluger M.S. Increased ICAM-1 expression causes endothelial cell leakiness, cytoskeletal reorganization and junctional alterations. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:762–774. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y., Zoulikha M., Xiao Q., Huang F., Jiang Q., Li X., et al. Pulmonary endothelium-targeted nanoassembly of indomethacin and superoxide dismutase relieves lung inflammation. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:4607–4620. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu Z., Godana D., Li A., Rodriguez B., Gu C., Tang H., et al. Echocardiographic assessment of right ventricular function in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.1177/2045894019841987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spyropoulos F., Vitali S.H., Touma M., Rose C.D., Petty C.R., Levy P., et al. Echocardiographic markers of pulmonary hemodynamics and right ventricular hypertrophy in rat models of pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2020;10 doi: 10.1177/2045894020910976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wermuth P.J., Li Z., Mendoza F.A., Jimenez S.A. Stimulation of transforming growth factor-β1-induced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and tissue fibrosis by endothelin-1 (ET-1): a novel profibrotic effect of ET-1. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim F.Y., Barnes E.A., Ying L., Chen C., Lee L., Alvira C.M., et al. Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell endothelin-1 expression modulates the pulmonary vascular response to chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L368–L377. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00253.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mauliūtė M., Rugienė R., Zėkas V., Bagdonaitė L. Association of endothelin-1 and cell surface adhesion molecules levels in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Lab Med. 2020;44:343–347. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chai S.P., Chang Y.N., Fong J.C. Endothelin-1 stimulates interleukin-6 secretion from 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson S.H., Simari R.D., Lerman A. The effect of endothelin-1 on nuclear factor kappa B in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:968–972. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandras S., Kovacs G., Olschewski H., Broderick M., Nelsen A., Shen E., et al. Combination therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension-targeting the nitric oxide and prostacyclin pathways. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2021;26:453–462. doi: 10.1177/10742484211006531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang T., Sheng H.H., Feng N.P., Wei H., Wang Z.T., Wang C.H. Preparation of andrographolide-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles and their in vitro and in vivo evaluations: characteristics, release, absorption, transports, pharmacokinetics, and antihyperlipidemic activity. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102:4414–4425. doi: 10.1002/jps.23758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yen C.C., Chen Y.C., Wu M.T., Wang C.C., Wu Y.T. Nanoemulsion as a strategy for improving the oral bioavailability and anti-inflammatory activity of andrographolide. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:669–680. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S154824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Y., Lin J., Cai Z., Wang P., Luo Q., Yao C., et al. Tumor microenvironment-activated self-recognizing nanodrug through directly tailored assembly of small-molecules for targeted synergistic chemotherapy. J Control Release. 2020;321:222–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gu D., O'Connor A.J., G.H. Qiao G., Ladewig K. Hydrogels with smart systems for delivery of hydrophobic drugs. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;14:879–895. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2017.1245290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kapate N., Clegg J.R., Mitragotri S. Non-spherical micro- and nanoparticles for drug delivery: progress over 15 years. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;177 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rawal M., Singh A., Amiji M.M. Quality-by-design concepts to improve nanotechnology-based drug development. Pharm Res (N Y) 2019;36:153. doi: 10.1007/s11095-019-2692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jin F., Liu D., Yu H., Qi J., You Y., Xu X., et al. Sialic acid-functionalized PEG-PLGA microspheres loading mitochondrial targeting modified curcumin for acute lung injury therapy. Mol Pharm. 2019;16:71–85. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marulanda K., Mercel A., Gillis D.C., Sun K., Gambarian M., Roark J., et al. Intravenous delivery of lung-targeted nanofibers for pulmonary hypertension in mice. Adv Healthc Mater Mater. 2021;10 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202100302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kolhar P., Anselmo A.C., Gupta V., Pant K., Prabhakarpandian B., Ruoslahti E., et al. Using shape effects to target antibody-coated nanoparticles to lung and brain endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10753–10758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308345110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Da Silva-Candal A., Brown T., Krishnan V., Lopez-Loureiro I., Ávila-Gómez P., Pusuluri A., et al. Shape effect in active targeting of nanoparticles to inflamed cerebral endothelium under static and flow conditions. J Control Release. 2019;309:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xin X., Pei X., Yang X., Lv Y., Zhang L., He W., et al. Rod-shaped active drug particles enable efficient and safe gene delivery. Adv Sci. 2017;4 doi: 10.1002/advs.201700324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Teng C., Lin C., Huang F., Xing X., Chen S., Ye L., et al. Intracellular co-delivery of anti-inflammatory drug and anti-miR 155 to treat inflammatory disease. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:1521–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Voigt J., Christensen J., Shastri V.P. Differential uptake of nanoparticles by endothelial cells through polyelectrolytes with affinity for caveolae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2942–2947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322356111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Y.X., Wang H.B., Li J., Jin J.B., Hu J.B., Yang C.L. Targeting pulmonary vascular endothelial cells for the treatment of respiratory diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.983816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Knobloch J., Yanik S.D., Körber S., Stoelben E., Jungck D., Koch A. TNFα-induced airway smooth muscle cell proliferation depends on endothelin receptor signaling, GM-CSF and IL-6. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;116:188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee K.S., Kim J., Kwak S.N., Lee K.S., Lee D.K., Ha K.S., et al. Functional role of NF-κB in expression of human endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;448:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu T., Zhang L., Joo D., Sun S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017;2 doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hsieh C.Y., Hsu M.J., Hsiao G., Wang Y.H., Huang C.W., Chen S.W., et al. Andrographolide enhances nuclear factor-κB subunit p65 Ser536 dephosphorylation through activation of protein phosphatase 2A in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5942–5955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.