Abstract

Background

Dental caries is one of the most common global childhood diseases and is, for the most part, entirely preventable. Good oral health is dependent on the establishment of the key behaviours of toothbrushing with fluoride toothpaste and controlling sugar snacking. Primary schools provide a potential setting in which these behavioural interventions can support children to develop independent and habitual healthy behaviours.

Objectives

To assess the clinical effects of school‐based interventions aimed at changing behaviour related to toothbrushing habits and the frequency of consumption of cariogenic food and drink in children (4 to 12 year olds) for caries prevention.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Oral Health Group's Trials Register (to 18 October 2012), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 4), MEDLINE via OVID (1948 to 18 October 2012), EMBASE via OVID (1980 to 18 October 2012), CINAHL via EBSCO (1981 to 18 October 2012) and PsycINFO via OVID (1950 to 18 October 2012). Ongoing trials were searched for using Current Controlled Trials (to 18 October 2012) and ClinicalTrials.gov (to 18 October 2012). Conference proceedings were searched for using ZETOC (1993 to 18 October 2012) and Web of Science (1990 to 18 October 2012). We searched for thesis abstracts using the Proquest Dissertations and Theses database (1950 to 18 October 2012). There were no restrictions regarding language or date of publication. Non‐English language papers were included and translated in full by native speakers.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of behavioural interventions in primary schools (children aged 4 to 12 years at baseline) were selected. Included studies had to include behavioural interventions addressing both toothbrushing and consumption of cariogenic foods or drinks and have a primary school as a focus for delivery of the intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Two pairs of review authors independently extracted data related to methods, participants, intervention design including behaviour change techniques (BCTs) utilised, outcome measures and risk of bias. Relevant statistical information was assessed by a statistician subsequently. All included studies contact authors were emailed for copies of intervention materials. Additionally, three attempts were made to contact study authors to clarify missing information.

Main results

We included four studies involving 2302 children. One study was at unclear risk of bias and three were at high risk of bias. Included studies reported heterogeneity in both the intervention design and outcome measures used; this made statistical comparison difficult. Additionally this review is limited by poor reporting of intervention procedure and design. Several BCTs were identified in the trials: these included information around the consequences of twice daily brushing and controlling sugar snacking; information on consequences of adverse behaviour and instruction and demonstration regarding skill development of relevant oral health behaviours.

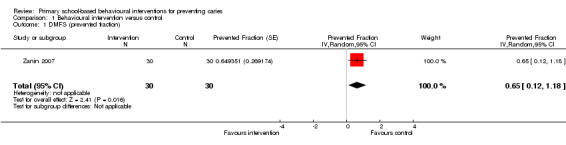

Only one included study reported the primary outcome of development of caries. This small study at unclear risk of bias showed a prevented fraction of 0.65 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.12 to 1.18) in the intervention group. However, as this is based on a single study, this finding should be interpreted with caution.

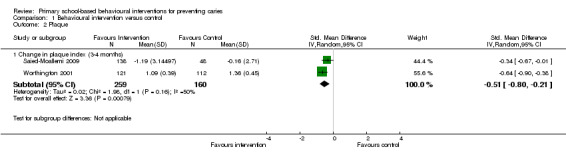

Although no meta‐analysis was performed with respect to plaque outcomes (due to differences in plaque reporting between studies), the three studies which reported plaque outcomes all found a statistically significant reduction in plaque in the intervention groups with respect to plaque outcomes. Two of these trials involved an 'active' home component where parents were given tasks relating to the school oral health programme (games and homework) to complete with their children. Secondary outcome measures from one study reported that the intervention had a positive impact upon children's oral health knowledge.

Authors' conclusions

Currently, there is insufficient evidence for the efficacy of primary school‐based behavioural interventions for reducing caries. There is limited evidence for the effectiveness of these interventions on plaque outcomes and on children's oral health knowledge acquisition. None of the included interventions were reported as being based on or derived from behavioural theory. There is a need for further high quality research to utilise theory in the design and evaluation of interventions for changing oral health related behaviours in children and their parents.

Keywords: Child; Child, Preschool; Humans; Schools; Candy; Candy/adverse effects; Carbonated Beverages; Carbonated Beverages/adverse effects; Cariogenic Agents; Cariogenic Agents/adverse effects; Dental Caries; Dental Caries/etiology; Dental Caries/prevention & control; Dental Plaque; Dental Plaque/etiology; Dental Plaque/prevention & control; Oral Hygiene; Oral Hygiene/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Toothbrushing; Toothbrushing/methods

Plain language summary

Programmes based in primary schools designed to help prevent tooth decay by changing children's behaviour

Improving the dental health of children is a global public health priority. Currently 60% to 90% of 5‐year olds worldwide suffer from tooth decay. Understanding how to intervene early with respect to establishing good dental health habits requires an understanding of the key behaviours which either help prevent decay (toothbrushing, twice a day with a fluoride‐based toothpaste) or encourage decay (sugar snacking) in children's teeth. Primary schools provide a setting in which behavioural interventions designed to encourage and establish good toothbrushing and snacking habits can be tested.

This review examined how successful the interventions in the suitable studies were in improving dental health in children aged from 4 to 12 years. The latest search of relevant studies was carried out on 18th October 2012.

Interventions were programmes that enabled children to.

∙ Making lasting changes to toothbrushing habits. ∙ Reduce the amount and how often food and drink known to cause tooth decay were consumed.

The trials had to include an educational element which taught skills or gave instructions and one or more accepted techniques to change behaviour.

Out of 1518 possible studies found only four were sufficiently relevant and of high enough quality to be included in this review. One small study showed that children who received the behavioural intervention developed fewer caries during the study. Three studies showed that there was less dental plaque (better oral hygiene) in the children in the behavioural intervention groups. More research is needed to confirm these findings.

The dental health of 4 to 12 year olds is an important issue ‐ reducing the amount of decay in this group would have a positive impact on overall health, particularly for those living in the poorest communities. More high quality research with well designed programmes will help to establish which techniques are most effective at changing child and parent behaviour to encourage good toothbrushing and discourage sugar snacking.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Behavioural intervention compared with control for prevention of caries in children | ||||

|

Patient or population: Children aged 4 to 12 years Settings: Primary school Intervention: Behavioural intervention (both oral hygiene and dietary components) Comparison: No intervention or delayed intervention | ||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% confidence interval (CI)) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Caries ‐ DMFS (prevented fraction (PF)) Follow‐up: 15 months |

PF = 0.65 (95% CI 0.12 to 1.18) | 60 participants (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | Small study of children at high risk of caries |

|

Plaque indices Follow‐up: 3 to 15 months |

All 3 RCTs showed a reduction in plaque in the intervention group compared to control group | 827 participants (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | Data not suitable for meta‐analysis |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1 Quality of the evidence was downgraded for risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment) and imprecision.

2 Quality of the evidence was downgraded for risk of bias (1 trial unclear and 2 trials high risk of bias) and inconsistency (heterogeneity due to differences in design, intervention and outcome measurement).

Background

Description of the condition

Oral diseases are common in many societies globally, with dental caries being the most prevalent chronic disease among children (Gussy 2006). Dental caries is present in low‐income, middle‐income and high‐income countries; between 60% and 90% of children in industrialised countries are affected (Petersen 2005). The US Surgeon General report on oral health (Surgeon General 2000) states that oral health problems are five times more likely to occur in children than asthma and seven times more than hay fever. Dental caries is a debilitating condition that can cause a child to suffer a significant degree of pain (Edelstein 2000) and if left untreated the disease may lead to further complications including sepsis (Pine 2006). Severe untreated caries has also been found to have links to general health and well being, affecting young children's body weight and growth (Sheiham 2006). Additionally, good oral health is important in terms of the psychosocial factors which relate to quality of life (Sheiham 2005) and optimum social functioning (Exley 2009) including self expression and communication. The mouth is a highly visible facial feature in most cultures (Goffman 1990). Discoloured and missing teeth have negative connotations in modern culture, being predominantly associated with unhygienic and undesirable lifestyles (Exley 2009) and with severe deprivation (Gibson 2008). Additionally, children who experience dental pain may lose time at school (Jackson 2011) and have difficulties sleeping, eating and playing (Casamassimo 2009). Being prevented from taking part in these and other normal recreational social activities with family and friends may have a detrimental effect on the child's social development and overall well being.

Brought about by dietary factors (such as frequent consumption of sugar) and exacerbated by inadequate oral hygiene routines (lack of brushing with fluoride toothpaste), caries is virtually completely preventable (Edelstein 2006). The impact of dental caries can be extensive and enduring for the child, sometimes impacting on their adult life (Nunn 2006) and potentially, future generations (Amin 2009).

Improving and promoting oral health has become common practice worldwide, both at local and population levels. Oral health is influenced by a myriad of interconnected variables, including socioeconomic status (SES) (Reisine 2001), ethnicity (Shiboski 2003) and attitudes (Blinkhorn 2001) which potentially have a cumulative effect and appear to be most profound in materially and socially deprived populations.

Rates of caries among children in many parts of the world have improved dramatically since the introduction of fluoridated toothpastes in the 1970s (Mullen 2005). Yet while child dental health has improved overall in recent years the gap between the most and least deprived children continues to widen (Armfield 2009; Watt 1999; Watt 2007), suggesting that relative poverty is a moderating factor in terms of rates of dental caries. Children from disadvantaged communities and some ethnic minorities have the highest rates of dental caries. This is particularly significant in light of observed increases in ethnic minorities among some communities and in the interest of halting and reversing the magnification of disparities throughout low SES groups (Pine 2004a).

Description of the intervention

Improving and promoting oral health has become common practice worldwide both at local and population levels. Establishing good routines in childhood is vital for optimum oral health as these behaviours, once established, can endure throughout adulthood (Aunger 2007) and provide lifelong protection against caries (Ramos‐Gomez 2002). Intervention studies related to child oral health have aimed to reduce childhood caries by encouraging children to establish and maintain effective oral health routines (e.g. Worthington 2001). Behaviour change interventions have utilised a number of evidence‐based behavioural change techniques (Michie 2008) including: goal setting, goal review, monitoring specified behaviours, coping planning/strategies, instruction, behavioural rehearsal, homework tasks and reinforcement. The experience of distressing dental treatment in childhood can result in dental fears and phobias which can progress into adulthood (Brukiene 2006). Dental anxiety is a commonly cited reason for adults refusing to attend routine oral health checks with a dentist. Non‐attendance can have a detrimental effect on oral health status (Eitner 2006) and may result in an increased number of patients requiring significant treatment. The cost of treating these patients creates a significant financial burden on the health services, both in terms of the cost of the treatment itself and in dealing with anxious patients. Oral health interventions early on in life could potentially save costs and avoid anxiety among patients later in life.

Patterns of behaviour conducive to positive dental outcomes are not always achieved in the home and this may be attributed to a variety of interconnected variables including SES (Shaw 2009) and cultural factors. For this reason and in the interest of reducing dental health inequalities, it remains necessary to provide effective interventions at the population level.

Primary schools, because of their inclusive nature, provide a suitable environment for dental health behavioural interventions (Kwan 2005). Interventions for preventing caries, which take place in primary schools, are potentially too late to prevent early childhood caries (ECC), particularly in its initial stages. However, targeting interventions at children earlier will reduce the effectiveness of interventions; that is to say, children develop the motor control necessary for effective toothbrushing more fully when they are primary school aged. Additionally children are unlikely to have sufficient control over routines in the home whilst they are very young. It is therefore inappropriate to target interventions for preventing caries (or ECC) at preschool age children (as opposed to targeting their parents).

Behaviours and routines are developed and become established during childhood, and as a result they become more difficult to alter in adulthood due to formed habits and automatic behaviour. Between the ages of 5 and 8 years children progress developmentally in many areas. To facilitate habitual tooth cleaning it is important to ensure the behaviour is established by the end of this life stage. Oral health programmes may be especially relevant at primary school level, particularly for children in their eighth year of life as this is considered to be a latency phase in which the child is more open to absorbing information about how to care for their body (Graham 2005).

Although brushing at home twice a day is optimum, many children do not do this. School‐based interventions not only offer children supervised brushing once a day, they also offer training in a skill that may not be being taught in the home. Although an artificial setting, which may not reproduce individual behavioural triggers for incorporating toothbrushing into a personal morning and evening hygiene routine at home, school‐based interventions facilitate the teaching of toothbrushing as a skill. Additionally, there is potential for translating these behaviours into the home environment on a twice daily basis. In spite of the increase in the number of school‐based oral health programmes in recent years, the majority of school‐based oral health interventions have not produced sustained behavioural change. A systematic review of oral health interventions (Kay 1996; Kay 1998) and a subsequent review by Watt 2001 found there to be an improvement in oral health knowledge but not in the related attitudes, beliefs and behaviours.

Parental habits impact on child behaviour, particularly through modelling actions. However, a parent's perception of their own ability to deliver the behaviour of regular toothbrushing (self efficacy) can also significantly impact on child dental health (Pine 2004b). Primary school‐based interventions rarely target both child and parent behaviour, or parental self efficacy. It remains crucial to the development of effective primary school‐based interventions that specific cultural components around self efficacy are identified so that they can be further refined if necessary and replicated in future interventions.

How the intervention might work

Primary school‐based interventions aiming to improve child oral health may disseminate education and information around developing skills for toothbrushing and managing the consumption of cariogenic foods and drinks. In addition they can provide support to parents and family to facilitate both behaviours occurring at home. This may be achieved through task‐specific behavioural rehearsal and reinforcement and through the application of other documented behaviour change techniques (BCTs). The overall outcome may be to increase child and parental self efficacy for oral health behaviours.

Why it is important to do this review

In many countries, primary schools have a recognised duty to deliver health education of which oral health education and the associated behavioural skills are often components. The purpose of this systematic review is to effectively evaluate research on behavioural interventions delivered in primary schools and to provide an understanding of the components and mechanisms of successful interventions which produce lasting behaviour change concerning toothbrushing and controlling the consumption of cariogenic foods and drinks.

Research has repeatedly found significant associations between SES and caries prevalence. The burden of oral ill‐health is such that it remains crucial to provide every child and their family with the knowledge and behavioural skills necessary to maintain a healthy dental lifestyle in the long term.

Objectives

To assess the clinical effects, in terms of caries prevention, of school‐based interventions aimed at changing behaviour related to toothbrushing habits and the frequency of consumption of cariogenic food and drink in children (4 to 12 year olds).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) where randomisation occurs at the level of the group (cluster by school and/or class) or individual children were included. All other studies were excluded during the screening process or at the point of data extraction.

Types of participants

Children within the age range of 4 to 12 years at the start of the study and attending a primary/elementary/infant or junior school in any country were included. Inclusion was irrespective of dental caries level at the start of the study, fluoride exposure, both topical (e.g. toothpaste, tablets, milk) and via water (both naturally occurring and added), current dental treatment and attendance levels, and nationality. Studies not predominantly taking place in a school setting were also excluded due to the focus of the current review. The review included studies regardless of whether teaching staff or peers were included in the delivery of the intervention.

For the purposes of this review, a 'school' is defined as a place delivering curricular primary education, to children aged between 4 and 12 years. Primary school encompassed the terms: junior, elementary, infant, kindergarten, community and nursery within the specified age range.

Types of interventions

Test or intervention group

Behavioural interventions (including education and/or skills and/or behaviour change) taking place in a school setting around oral health and/or hygiene and frequency of cariogenic food and drink consumption. Studies were included with or without a follow‐up period after the completion of the intervention.

Interventions for inclusion in this review were required to:

have a focus around toothbrushing and cariogenic foods;

use schools as the focal site for intervention delivery;

contain skills, instructions and educational components.

The intervention may be delivered by teachers, dental health professionals, peers, or other educators and must be delivered principally in the school the children are attending. Elements of the intervention may also occur in the home and in clinical settings. Delivery of intervention components can be written, verbal, web‐based or through electronic devices (e.g. video games).

The aim of the intervention must be to improve child oral health. Studies utilising one or more behaviour change techniques (BCTs) were included in the review. Behavioural interventions were coded using the Coding Manual to Identify Behaviour Change Techniques in Behaviour Change Intervention Descriptions, detailed by Abraham 2008. This provided a pre‐validated method to code specific BCTs in interventions. Examples of BCTs that may be included are: reinforcement (brushing charts), modelling (facilitator demonstration of correct brushing technique) and prompts and cues (visual reminders in appropriate settings).

Control group

The control group should receive usual curriculum‐based health education programmes; these may be defined as standard health information and education offered as part of the school curriculum and independent of the study intervention (non‐intervention control). Control groups may also be waiting list control groups.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded where:

the intervention was a change at the level of the school environment ‐ such as change in foods and drinks available in schools;

the intervention was within a nursery school but targeting only children aged 3 to 5 years old.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Changes in caries increment measured by the difference in decayed, missing and filled teeth (dmft/DMFT).

Changes in caries increment on tooth surfaces (dmfs/DMFS).

Changes in plaque scores for permanent and deciduous teeth over the course of the intervention and the follow‐up period.

Primary outcomes for both permanent and deciduous teeth were considered if they measured change from baseline for the same cohort of children. For the purposes of this review, clinical effectiveness is defined as either a change in caries experience (decayed, missing or filled teeth ‐ dmft/DMFT) and/or a change in the amount of dental plaque.

Secondary outcomes

Frequency of toothbrushing: measured using reported data correlated with clinical measures.

Frequency of cariogenic food and drink consumption: reported behaviour.

Behavioural outcomes: reported and/or other measures (e.g. data tracking toothbrushes and collecting food wrappers).

Changes in dental attendance (i.e. frequency of dental check‐ups, increase in dental attendance) during the period of the intervention.

Adverse events were recorded using data extraction forms if they were reported. These were considered by the review team.

Search methods for identification of studies

For the identification of studies included or considered for this review, detailed search strategies were developed for each database searched. These were based on the search strategy for MEDLINE but revised appropriately for each database to take account the differences in controlled vocabulary and syntax rules. No restriction on the language of publication was applied to the inclusion criteria.

The search strategy combined the subject search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying reports of randomised controlled trials as published in box 6.4.c in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) (Higgins 2011).

Electronic searches

The following databases were searched:

The Cochrane Oral Health Group's Trials Register (to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 1)

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, 2012, Issue 4) (Appendix 2)

MEDLINE via OVID (1948 to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 3)

EMBASE via OVID (1980 to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 4)

CINAHL via EBSCO (1981 to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 5)

PsycINFO via OVID (1950 to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 6)

Current Controlled Trials (to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 7)

ClinicalTrials.gov (to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 8)

ZETOC (limited to Conference Proceedings) (1993 to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 9)

Web of Science (limited to Conference Proceedings) (1990 to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 10)

Dissertations and Theses via Proquest (1950 to 18 October 2012) (Appendix 11).

Searching other resources

In addition to conducting systematic searches of electronic databases, handsearches of appropriate journals were conducted where these have not already been searched as part of the Cochrane Journal Handsearching Programme. The following journals have all been identified as those in which trials in the field are likely to be reported:

Acta Odontologica Scandinavica (2004 to October 2012)

ASDC Journal of Dentistry for Children (2004 to October 2012)

British Dental Journal (2006 to October 2012)

Caries Research (2004 to October 2012)

Community Dental Health (2003 to October 2012)

Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology (2003 to October 2012)

Journal of the American Dental Association (2005 to October 2012)

Journal of Dental Research (2005 to October 2012)

Journal of Public Health Dentistry (2004 to October 2012)

Swedish Dental Journal (2002 to October 2012)

International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry (2000 to October 2012).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Citations retrieved were screened for relevance by five review authors independently on titles, keywords and abstracts. For studies where there was insufficient evidence in the title, keywords or abstracts, or the review team did not agree on the inclusion/exclusion of the report, the full study/paper was obtained. References screened as relevant for the review were obtained in full and assessed for inclusion in the review. If disagreement arose, other review authors were consulted to resolve this; such occurrences were documented.

All included studies were subject to a cited reference search aimed at identifying any related publications.

Data extraction and management

Four review authors extracted data for all included studies. The review authors worked in pairs and any discrepancies arising were discussed by the team. Prior to use, the data extraction form was piloted on a sample of articles to allow for any necessary modifications. Following Cochrane guidelines, details of why studies failed to meet the review criteria were documented and are presented in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

For each included study we recorded the following data.

Study identification code.

Number of reports on study.

Year study commenced and finished.

Trial funding, number of sites on which the study has been conducted.

Method: study design, type of randomisation, duration of study.

Participants: recruitment, inclusion/exclusion, demographic characteristics, baseline fluoride exposure and dental health data (dmft, dmfs).

Intervention: description of the programme including intervention facilitator, specific BCTs and components utilised as outlined in the Taxonomy of Behavioural Change Techniques Used in Interventions (Abraham 2008). Information on specific theoretical health models that had been reported to inform the intervention design was also recorded.

Control group(s): number of points of contact with researchers and details.

Outcome measures and outcome data collection time points as reported.

Adverse effects.

Analysis details.

Rates of attrition.

Follow‐ups, including time intervals.

Risk of bias.

Risk of bias specific to cluster randomised trials: recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of cluster, incorrect analyses and comparability with individual randomised trials.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The recommended method for assessing the risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane reviews, set out in chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) was applied.

This is a two‐part tool, addressing seven specific domains (namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and 'other bias'). Each domain includes one or more specific entries in a risk of bias table. Within each entry, the first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry. This is achieved by assigning a judgement of 'Low risk' of bias, 'High risk' of bias, or 'Unclear risk' of bias. The risk of bias assessment was undertaken independently and in duplicate by four review authors in total as part of the data extraction process. Where a consensus was not reached, methods experts within the group were consulted.

After taking into account the additional information provided by the authors of the trials, studies were grouped into the following categories.

Low risk of bias (plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results) for all key domains.

Unclear risk of bias (plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results) if one or more key domains were assessed as unclear.

High risk of bias (plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results) if one or more key domains were assessed to be at high risk of bias.

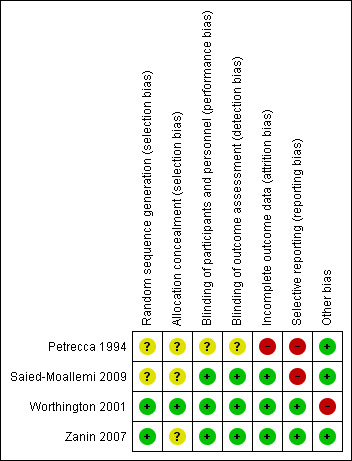

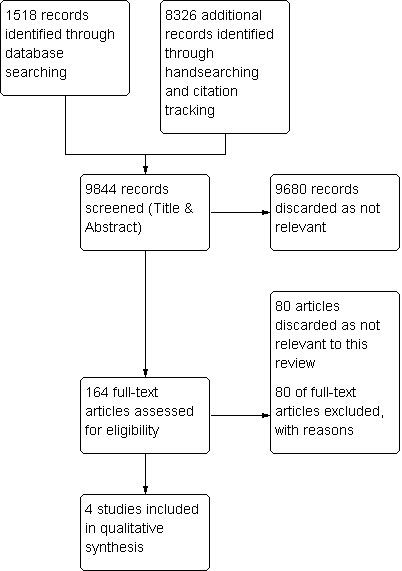

A risk of bias table (Characteristics of included studies) was completed for each included study and the results are presented graphically (Figure 1; Figure 2).

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data were not reported. Although Zanin 2007 reported on prevalence rates, caries increment was calculated.

In dealing with caries increment data, the mean difference and standardised mean difference were calculated and taken as the summary statistic. If multiple studies reporting a variety of measures (dmft, dmfs etc.) had been included in this review, the prevented fraction (i.e. mean caries increment in the treatment group subtracted from that of the control group and divided by the mean increment in the control group) would have been calculated. Use of prevented fraction allows for a more reliable examination of heterogeneity between trials.

Unit of analysis issues

The review included cluster randomised controlled trials, where schools or classes are the unit subject to randomisation. Where appropriate, intra‐cluster correlation coefficients (ICC) were used to estimate variability between and within clusters as detailed in section 16.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Methods of analysis and reporting were reviewed for appropriateness by a review author expert in these methods (Girvan Burnside (GB)).

Dealing with missing data

If data were unavailable and clarification required (e.g. study characteristics and numerical outcome data), corresponding authors of studies were contacted directly in order to obtain missing information.

Where authors could not be contacted, missing standard deviations were estimated using intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses when primary outcome data or participant attrition data are missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where there was poor overlap of confidence intervals of the individual studies, assessments of heterogeneity were carried out using the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic. The I2 statistic was interpreted according to the guide provided in section 9.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), the magnitude and direction of effects and alongside the P value of the Chi2 test. Sources of heterogeneity were explored where the I2 statistic exceeds 25%. If there was unexplained heterogeneity, a meta‐analysis was not conducted.

Assessment of reporting biases

The impact of reporting bias was minimised by undertaking comprehensive searches of multiple sources (including trial registries), increasing efforts to identify unpublished material and including non‐English language publications. Efforts were also made to identify outcome reporting bias in studies by recording all outcomes, planned and reported, and noting where there were missing outcomes. Where evidence of missing outcomes was found, attempts were made to obtain any available data direct from the study authors.

Data synthesis

For the primary outcome variable, the treatment effect was assessed by calculating the relative effect as indicted by the prevented fraction (PF): the mean caries increment in controls minus mean caries increment in the intervention group, divided by the mean caries increment in controls. For the included study, the 95% confidence interval of the PF was calculated.

Each included study was summarised and described according to participant and intervention characteristics and outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were planned on the basis of:

age: 4 to 7 years and 8 to 12 years (best practice advice on child age associated competencies for effective toothbrushing; i.e. it is advised that parents undertake or supervise toothbrushing for children under 7 years);

number of BCTs applied as denoted in the Taxonomy of Behavioural Change Techniques Used in Interventions (Abraham 2008);

frequency and duration of exposure to the intervention; and

gender.

A test to determine the interaction between the subgroup estimates was planned.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was planned on:

risk of bias assessment;

random‐effects modelling;

ICCs estimates where these values were missing in studies.

Only studies at low risk of bias were included in the final analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Further descriptions of the studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies tables. The following section summarising key aspects of the studies.

Results of the search

The processing of the references identified through electronic searches, handsearches and citation tracking is described in Figure 3. After de‐duplication of the results from electronic searching there were 1518 records. A further 8326 records were identified through handsearching and citation tracking (total 9844). Based on the screening of the title and abstracts (Sarah Elison (SE), Lucy O'Malley (LO), Pauline Adair (PA), Rosemary Armstrong (RA), Anna Cooper (AC)), 9680 records were discarded as irrelevant to this review. Articles were rejected on initial screening if the review author could determine from the title and abstract the article did not meet the inclusion criteria. The review authors assessed full‐text copies of 84 articles (SE, LO, PA, RA, AC). Two review authors (Lindsey Dugdill (LD), AC) independently double screened all citations once the initial screening had been completed. Sixty‐four references were discarded as not relevant. Subsequently, 20 articles were indicated as having potentially met the inclusion criteria and were subjected to full data extraction. During this phase, 16 articles were deemed not to have the distinct elements of the intervention that targeted cariogenic food (in addition to toothbrushing) or the study, upon further examination, was found not to be an RCT. In one case, a study was deemed to be so poorly reported that it could not be included in this review.

3.

Review flow diagram.

Included studies

Characteristics of the trial design and setting

Two studies were cluster randomised at the level of the school (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001); with the remaining two trials randomised at the level of the individual (Petrecca 1994; Zanin 2007). One study was conducted in South America (Brazil) Zanin 2007, two in Europe, Petrecca 1994 in Italy and Worthington 2001 in the UK and one in Asia, Saied‐Moallemi 2009 in Tehran.

Sample size: In total 2302 children participated in the four studies, of these 1529 children were subject to behavioural interventions and 773 children acted as controls. Sample sizes ranged from 30 (Zanin 2007) to over 400 per group (Petrecca 1994). For a more detailed breakdown of sample size per study please refer to the Characteristics of included studies tables. Two studies reported that power calculations were conducted to inform the sample size (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Zanin 2007), the remaining two studies did not report how the sample size was arrived at.

Of the included studies, two did not state the source of trial funding, the study by Saied‐Moallemi 2009 was supported by the Iran Centre for Dental Research and the other study by the National Sugar Bureau (Worthington 2001).

Characteristics of the participants

4 to 7 year olds (baseline)

One study was conducted with children aged 4 to 7 years (Zanin 2007). The intervention reported by Zanin 2007, taught an age‐appropriate modified toothbrushing technique to the children. This was done through instruction and demonstration. The technique took into account the limited motor control of children at this age and aimed to improve the children's plaque removal ability. Supervised brushing sessions took place every 3 months. In addition, the intervention involved educational elements which covered dental hygiene and consumption of cariogenic food and drink.

8 to 12 year olds (baseline)

Two studies were conducted with children aged 8 to 12 years (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001). They were both delivered and monitored by dental professionals, with one involving teachers alongside dental professionals (Saied‐Moallemi 2009). Both linked the school programme to the home with varying levels of parental involvement.

Age at baseline unclear

Petrecca 1994 only reported that children at baseline were within primary school age and specified at baseline they were in primary school years one to three. Based on the current Italian school system, this may indicate that the children were aged between 6 and 9 years at baseline, however it is important to note that this cannot be confirmed. Attempts to make contact with the authors were unsuccessful. The intervention was aimed at children and teachers; diagrams and plastic models were used to explain caries to the children and to teach them oral (including dietary) hygiene. Children were asked every 30 days if they were following the oral (and dietary) hygiene regimen. Teachers were involved in the delivery of the intervention. A second intervention group had the same educational programme plus daily fluoride tablets (1 mg).

The number of boys and girls within each group was not outlined in two studies (Petrecca 1994; Zanin 2007). One study randomised eight boys and eight girls schools separately to include two schools of each gender within each of the four clusters (Saied‐Moallemi 2009 ). The remaining study (Worthington 2001) had an overall equal number of girls and boys in intervention and control groups (based on information from Hill 1999).

One study (Petrecca 1994) excluded children who were either unable to follow the instructions provided or had not taken their fluoride tablets. All children within the research area were given the opportunity to participate in the intervention reported by Worthington 2001. This was facilitated by the design with only those with positive consent being sampled for a clinical examination. One study (Zanin 2007) reported that children were excluded from the study at baseline if they were showing signs of severe fluorosis, hypoplasia, or systemic alteration. Children were also excluded from this study if they had fixed braces. One study did not report any exclusion criteria (Saied‐Moallemi 2009).

Characteristics of the interventions

In all cases, interventions took the form of educational programmes, broken down into a series of classroom‐based lessons. Lessons were designed to fit into the UK national curriculum in one study (Worthington 2001). Details of the design of the interventions of the remaining studies were not reported. All interventions included toothbrushing instruction and skill lessons and information on the use of fluoride toothpaste. Supervised toothbrushing practice sessions with the children were carried out in two of the interventions (Worthington 2001; Zanin 2007). Although all interventions included dietary elements (as per inclusion criteria), the strength of this component varied across the interventions. Information around dietary effects was provided through group discussion (Worthington 2001) or lessons (Zanin 2007), or via instruction (Petrecca 1994) and in one study was provided only through leaflets or worksheets (Saied‐Moallemi 2009). In all studies, it appeared that the dietary elements came secondary to dental hygiene in terms of the strength of delivery.

General dental health information and more detailed information around the behaviour health link was included in all interventions. Interventions were delivered by specifically trained dental nurses (Worthington 2001) and by school health counsellors and teachers (Saied‐Moallemi 2009). For the remaining studies, it is unclear who delivered the interventions. Disclosing tablets were used as part of the interventions in one study as part of a classroom activity (Worthington 2001).

Structures for transition of the intervention into the home were absent in two of the studies (Petrecca 1994; Zanin 2007). Saied‐Moallemi 2009 described one intervention arm that provided parents with leaflets and materials (e.g. brushing charts and worksheets) used in the school with the aim of getting the parents to replicate the intervention at home (these children did not receive an intervention in school). The remaining intervention arm in this study included a combination of home and school elements, each intended to reinforce the other. One study encouraged a link to the home with the provision of oral health related home work tasks (along the same theme as the work in schools) lasting around 1 hour. Parents or grandparents were required to complete these with the children (Worthington 2001).

In three of the studies, control groups were non‐intervention controls; no preventive treatment or instruction was provided (Petrecca 1994; Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001). However in one of these studies half the control schools became active at 4 months (Worthington 2001). In the remaining study (Zanin 2007) treatment, including fillings and extractions, was provided as well as an annual supervised toothbrushing session.

Of the included trials, two did not report that pilot work had been carried out prior to the development of the intervention (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Zanin 2007). One study conducted pilot work on a population previously examined by the authors (Petrecca 1994) and the remaining study piloted the intervention with children and teachers to test measures, delivery and materials prior to the RCT (Worthington 2001).

In the included studies post‐intervention outcome measures were reported at 3 months (Saied‐Moallemi 2009), 6 months (Zanin 2007) and 1 year after the intervention (Petrecca 1994). Worthington 2001 employed a cross‐over design and as such reported post‐intervention outcome measures at 4 months within phase one and after 3 months for phase two. Only one of the included studies reported having an additional follow‐up time point (Petrecca 1994).

Excluded studies

The search and screening process is summarised in Figure 3. Studies not included in this review (and the reason for exclusion) can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The most common reason for exclusion was study design. Studies were also excluded where behavioural interventions were provided along side clinical interventions such as sealants or varnish making it impossible to determine the effect of the behavioural intervention alone. Additionally, a substantial number of studies were excluded on the basis that the intervention did not contain the two key components described in the inclusion criteria (oral hygiene and diet) for this review. Most commonly, interventions tended to be based around oral hygiene only.

Risk of bias in included studies

Quality assessment was conducted using The Cochrane Collaboration's 'risk of bias' tool on all included studies. This assesses each study on seven domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and any other bias. Across the domains relating to selection, performance and detection bias, the majority of trials scored low or unclear. Selective reporting bias was deemed to be highest risk of bias, being scored as high for half of the included studies (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Overall the risk of bias was assessed as unclear in Zanin 2007, and high in the remaining three studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

One of the studies reported that a "lottery" was the method of randomisation (Zanin 2007) and for another included study, details were provided by personal communication (Worthington 2001) confirming that randomisation was achieved by way of a computer generated schedule. Both of these studies were assessed as low risk of bias for this domain. The remaining two studies were assessed at unclear risk of bias here.

Allocation concealment

It was unclear who conducted the "lottery" in the study reported by Zanin 2007, so allocation concealment was assessed as unclear. Personal communication confirmed that allocation to intervention and control groups was undertaken by the statistician and concealed from the dental nurse who conducted the intervention in the other study (Worthington 2001). The remaining two studies reported no information about allocation concealment and were assessed at unclear risk of bias. Within these, two of the studies were cluster randomised controlled trials (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001) with the unit of allocation being the school.

Blinding

Participants and personnel

Blinding of deliverers and participants in behavioural interventions is problematic and this has been acknowledged in other Cochrane reviews of behavioural interventions (e.g. Waters 2011). Some of the included studies in this review had attempted to minimise the level of information given to children, however it was not always possible to blind the delivery of the intervention for obvious reasons.

Two studies reported that participants were not aware of the treatment group they were allocated to (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Zanin 2007). Two were cluster randomised hence it was assumed that the risk of performance bias was reduced (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001).

Outcome assessors

Three studies were judged to be of low risk of performance bias (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001; Zanin 2007). Lack of information in the remaining study (Petrecca 1994) meant it was not possible to ascertain the level of bias (Petrecca 1994); this was judged to be unclear.

Of the studies that were judged to have low risk of performance bias, three were also judged to have low risk of detection bias, having reported on blinding (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001; Zanin 2007). For the remaining study (Petrecca 1994) it was not possible to determine the detection bias due to insufficient reporting.

Incomplete outcome data

Three studies included in the review were judged to be of low risk of attrition bias (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001; Zanin 2007). Low levels of participant drop‐out were reported across these studies meant that attrition was unlikely to impact upon the outcomes of interest.

The study described by Petrecca 1994 was judged to be of high risk of attrition bias as some children were taken out of the sample after the initial phase for not adequately following the oral hygiene and nutrition components of the intervention. Rates of attrition were different in each group over the 2 years of this trial.

Selective reporting

Half of the included studies in this review were judged to have low risk of reporting bias (Worthington 2001; Zanin 2007). However, it is important to note that study protocols could not be obtained; it was clear from the papers that all pre‐specified and expected outcomes were reported.

One study was judged to have high risk of reporting bias (Petrecca 1994) because only point estimates with no estimates of variance were reported, meaning that data could not be interpreted accurately.

Other potential sources of bias

Although the study reported by Worthington 2001 was judged to be of low risk of bias for all other domains, bias may have been introduced regarding the outcome data for plaque. Plaque was measured using a subsample of 10 children in each school, selected based on parental consent. It is possible that the children whose parents did not give consent may have had different mean plaque scores to the subsample measured. It was established through communication with the author that the funder of this study (National Sugar Bureau) had no influence over the data reported.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

SeeTable 1.

Primary outcomes

Changes in caries increment measured by the difference in decayed, missing and filled teeth (dmft/DMFT)

One study reported DMFT (Petrecca 1994). While it is unclear as to the precise age of the children in this study, concern about measurement arose from a sentence in the methods section of this paper: "The WHO advises using the same criteria for milk teeth as for permanent dentition, using DMFT but taking into account that teeth lost through caries can be identified only up to the age of 8, since up to that age the absence of a milk molar cannot be due to changeover".

From the DMFT data reported in this study we calculated an estimate of prevented fraction of 0.49 over 2 years, but no standard deviations or standard errors were presented in the paper. Three attempts in total were made to contact the authors of this study for clarification, unfortunately these were unsuccessful. Due to the uncertainty over the measure, this study has not been included in the analysis.

Changes in caries increment on tooth surfaces (dmfs/DMFS)

One study reported on dmfs/DMFS (Zanin 2007). Data presented allowed for the calculation of caries increment, but not standard deviations. This study has been included in the analysis, with estimated standard deviations (SDs) calculated using the regression equation derived by Marinho 2009 in the review of Topical fluorides for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. This equation was based on a regression analysis of 179 treatment arms. The equation is log (SD caries increment) = 0.64 + 0.55 log (mean caries increment).

This study showed evidence of a reduction in caries increment measured by the difference in decayed missing and filled surfaces (preventive fraction (PF) 0.65, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.12 to 1.18, 1 RCT, 60 participants) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Behavioural intervention versus control, Outcome 1 DMFS (prevented fraction).

Changes in plaque scores for permanent and deciduous teeth over the course of the intervention and the follow‐up period

Three studies reported plaque outcome data. All plaque indices were based on variations of the Silness and Löe index, with results reported either as post‐treatment plaque score, or change in plaque score from baseline. While the indices differ, they aim to measure a similar outcome and so standardised mean difference (SMD) was used to measure treatment effect.

One study (Zanin 2007) only reported median plaque index (PI). The median PI at the end of the study (15 months) was reported as 0.93 in the control group and 0.60 in the intervention group, with a Mann‐Whitney test reported as significant (P < 0.05). No means were reported, so we were unable to include this outcome in the analysis.

Saied‐Moallemi 2009 reported change in plaque index between pre‐ and post‐intervention examinations. This study had three intervention groups, all of which were judged to meet the inclusion criteria for this review, so the data from these three groups have been combined for analysis here. The study was cluster randomised, with four clusters per group (so 12 clusters in the combined intervention group). No intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) was reported, although the authors did recognise the cluster design in the analysis of additional outcomes (using generalised estimating equations) the plaque analysis did not adjust for clustering. For the purposes of this review, the ICC has been assumed to be 0.05 (Higgins 2011). After adjustment for clustering, there was a significant difference in change in plaque score, with the intervention groups showing better oral hygiene (SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.67 to ‐0.01, cluster adjusted effective sample size 186).

The remaining study, Worthington 2001, was cluster randomised and analysed using generalised estimating equations to allow for the clustering in the analysis. ICC values were also included in the paper, allowing the SMD to be appropriately adjusted for the clustering, by amending the effective sample size. This study presented outcomes at 4 and 7 months, but after the 4‐month examination, the groups were re‐configured, so data from the 4‐month examination have been included here. After adjustment for clustering, there was a significant difference in plaque score, with the intervention group showing a reduction in plaque (SMD ‐0.64, 95% CI ‐0.90 to ‐0.38, cluster adjusted effective sample size 233).

When the Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001 were combined in a meta‐analysis, there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 0.50) likely to be due to differences in study design and in the details of the interventions, so meta‐analysis has not been presented (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Behavioural intervention versus control, Outcome 2 Plaque.

Secondary outcomes: Non‐clinical

Of the four included studies, three (Petrecca 1994; Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Zanin 2007) did not measure any secondary outcomes. A variety of non‐clinical measures have been reported in one study (Worthington 2001). These measures relied on self report. The data are described below. There is at present no single reliable method for recording toothbrushing or sugar snacking behaviours.

Children's frequency of toothbrushing

Worthington 2001 reported on children's brushing frequency. Almost all children (99%) at baseline reported twice daily brushing prior to the start of the study, and this level was maintained across all groups throughout the intervention. However, in the baseline focus groups, 'most' children reported that they did not brush their teeth more than once a day.

Children's frequency of cariogenic food and drink consumption

Worthington 2001 reported few children had problems identifying foods containing sugar with only 15% of the intervention and 19% of control participants reporting they routinely consumed sugary snacks when they arrived home from school. However, snack consumption prior to bedtime was reported by approximately a third of participants at baseline, with this figure showing a non‐significant decline across the study period.

Change in oral health knowledge and skills

Worthington 2001 reported changes in oral health knowledge and skills following the intervention. Changes were apparent in both the intervention and control groups at the 4‐month follow‐up (phase one); however, this improvement was greater among the intervention group (34% increase) compared to the control group (15% increase). In phase two, post‐intervention measures showed that the new intervention group had a 10% improvement in knowledge and skill and previous increases found in the intervention and control groups were sustained.

No other behavioural outcomes were measured by the four included studies.

Changes in dental attendance

Worthington 2001 found no change in reported dental visits over the course of the programmes, with 97% of children at baseline reporting visiting the dentist every 2 years. When asked in the focus groups however, most children reported being unsure how often dental visits are recommended.

Adverse events

No study reported any adverse events.

Other analyses

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were planned, however these were not conducted due to insufficient studies.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review includes four studies of primary school‐based behavioural interventions aimed at preventing dental caries in children 4 to 12 years of age. Studies were generally less than 2 years in length and there is very limited evidence from these randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the efficacy of the interventions for dental health. Lack of uniformity in describing the interventions and measuring and reporting outcome variables made accurate pooling of evidence difficult. Only one small study, with 60 participants (Zanin 2007), reported a caries outcome, and showed that the children in the intervention group developed fewer new caries over the study period. Although no meta‐analysis was performed for plaque outcomes, three studies reporting plaque (Saied‐Moallemi 2009; Worthington 2001; Zanin 2007) reported statistically significant reductions in plaque in the intervention groups. This provides some limited evidence that these interventions reduce plaque outcomes over the short term. Short term improvements in plaque scores may arguably not be considered a 'true health outcome' and do not provide useful information on long term effects of these interventions.

In summary the key learning from this review in terms of the efficacy of primary school‐based behavioural interventions on clinical and behavioural outcomes is very limited. The included studies were multifarious in terms of intervention design and clinical and behavioural outcomes. Consequently it is difficult to give any clear evidence‐based recommendations as to the best intervention designs with respect to oral health behaviour change.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This is the first Cochrane review that has examined the use of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) in dental clinical trials. Behaviour change science has progressed rapidly over the last decade and has been applied within various areas of public health research including attempts to change multiple behaviours (e.g. diet and physical activity in obesity interventions) (Michie 2012).

Interventions were subject to high levels of heterogeneity and ways of measuring caries and plaque outcomes varied. Meta‐analysis could not be conducted on caries outcomes as data from only one study were eligible. Nor could a meta‐analysis be conducted on plaque outcomes as we judged heterogeneity to be too high. Additionally, subgroup analysis could not be conducted due to the low number of included studies.

The studies included in this review provide a limited means for answering questions around how best to prevent caries through primary school‐based behavioural interventions. The interventions themselves were not described in detail within published reports, however it is recognised that publication limitations may apply.

Several BCTs could be identified in the included studies; these are recorded in Additional Table 2 (theoretical basis of these BCTs is provided in Appendix 12). These were predominantly around.

1. Behaviour change techniques (BCTs).

| Petrecca 1994 | Saied‐Moallemi 2009 | Worthington 2001 | Zanin 2007 | |

| 1. Provide information about behaviour health link (IMB) | ✓ | ✓ (H&S) | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2. Provide information on consequences (TRA, TPB, SCogT, IMB) | ✓ | ✓ (H) | ✓ | ✓ |

| 3. Provide information about others' approval (TRA, TPB, IMB) | ||||

| 4. Prompt intention formation (TRA, TPB, SCogT, IMB) | ✓ (S) | |||

| 5. Prompt barrier identification (SCogT) | ||||

| 6. Provide general encouragement (SCogT) | ||||

| 7. Set graded tasks (SCogT) | ||||

| 8. Provide instruction (SCogT) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9. Model or demonstrate the behaviour (SCogT) | ✓ | ✓ (S) | ✓ | |

| 10. Prompt specific goal setting (CT) | ||||

| 11. Prompt review of behavioural goals (CT) | ||||

| 12. Prompt self monitoring of behaviour (CT) | ✓ | |||

| 13. Provide feedback on performance (CT) | ✓ | |||

| 14. Provide contingent rewards (OC) | ||||

| 15. Teach to use prompts or cues (OC) | ||||

| 16. Agree on behavioural contract (OC) | ||||

| 17. Prompt practice (OC) | ✓ | ✓ (S) | ✓ | ✓ |

| 18. Use follow‐up prompts | ✓ | |||

| 19. Provide opportunities for social comparison (SCompT) | ✓ | |||

| 20. Plan social support or social change (Social support theories) | ✓ (H) | |||

| 21. Prompt identification as a role model | ||||

| 22. Prompt self talk | ||||

| 23. Relapse prevention (Relapse prevention therapy) | ||||

| 24. Stress management (Stress theories) | ||||

| 25. Motivational interviewing | ||||

| 26. Time management |

Extraction: Saied‐Moallemi 2009 ‐ (H) refers to the home intervention only arm with (S) referring to the school only intervention arm.

The BCTs were extracted from the description of the intervention reported in each paper by 3 authors (Pauline Adair (PA), Lucy O'Malley (LO) and Sarah Elison (SE)). All additional resources (obtained through contact with study authors) were incorporated into this phase of data extraction. The taxonomy of BCTs (Abraham 2008), was used to code all published and unpublished information around the content of each intervention. No assumptions were made that BCTs were present if the available information was unclear. It is important to note that the taxonomy defines discrete BCTs meaning that no one element of an intervention can appear as 2 separate techniques.

Instruction ‐ in most cases referred to promoting toothbrushing or demonstration of brushing but also changing sugar consumption.

Demonstration of toothbrushing ‐ which varied from using models (Petrecca 1994) to supervision of the children's technique on a regular basis, in Saied‐Moallemi 2009 by health counsellors. In the intervention reported by Zanin 2007, it was unclear who supervised the brushing sessions and whether they were trained to do so.

In the case of the intervention described by Zanin 2007, the aetiology of caries was explained in order to provide children with the link between behaviour and consequences. In the intervention described by Worthington 2001, general behaviours were described as resulting in particular dental outcomes. In all cases messages were disseminated either through leaflets or through lessons. One study reported that the interventions involved some form of active learning, such as group discussion (Worthington 2001).

The data presented by Zanin 2007 indicate a large effect on caries as a result of the intervention. It is important to note that the intervention included an age specific toothbrushing technique and toothbrushing was practiced at regular supervised intervals. The evaluation period did not extend beyond the length of the intervention and as such we cannot be certain of the long term impact of this intervention on health behaviours.

Many of these interventions targeted knowledge. It is recognized that knowledge increase or indeed instruction will not necessarily lead to sustained behavioural change (Freeman 2009; Kay 1996; Kay 1998; Stillman‐Lowe 2008). The integration of relevant behavioural components may be important in terms of behavioural outcomes. Such components may benefit from inter‐professional delivery or expertise in the integration of the intervention by an appropriately trained team (Watson 2011).

Quality of the evidence

Based on the evidence gathered by this review (four studies incorporating a total of 2302 children at baseline), it cannot be determined that primary school‐based behavioural interventions are effective at promoting behaviours related to caries prevention.

Methodologically, there were inconsistencies in the use of the terms 'post‐intervention' and 'follow‐up' to describe outcome measurement. No study reported considerations related to exit strategies upon completion of supported intervention delivery hence we cannot make any judgements about the sustainability of interventions.

The interventions reported in this review primarily focused on the toothbrushing component, with the cariogenic dietary component carrying much less weight. Only two of the studies reported that a power calculation had been conducted to determine sample size. There was considerable variation in terms of who delivered the interventions (including variation in the training received). No study reported delivery by dietary professionals. The variation in the responsibility for delivery, reinforcement and maintenance of interventions is likely to impact upon the fidelity and hence efficacy of the interventions. Studies reported frequent supervised toothbrushing sessions and in some interventions parents were encouraged to take an active role in supervising their child's toothbrushing (active reinforcement) however, this intensity of intervention was not replicated for the cariogenic food/drink components.

Based on the evidence for school behavioural interventions for preventing caries presented by the studies included in this review, there are significant knowledge gaps. None of the studies included a cost‐benefit analysis, additionally there was limited analysis of the impact of deprivation. Little can therefore be said about the potential financial implications of providing behavioural interventions in a primary school setting. Further research is also required around the impact of deprivation on behavioural interventions targeting primary school children. Child oral health related quality of life and overall health status are not reported as outcome measures or explanatory variables in any of the included studies.

While some studies have reported behavioural measures alongside clinical outcomes, none have attempted to link the various types of evidence to understand the effects of the interventions in a holistic sense. Complex behavioural interventions require process evaluations to explore, in greater depth, how and why they work or do not. Such evaluations "would improve the science of many randomised controlled trials" (Oakley 2006).

None of the interventions were underpinned by theory. Pilot work to inform intervention design appeared limited, a noteworthy finding in consideration of the recent guidance from the MRC 2000 updated to MRC 2008, NICE 2007 and Intervention Mapping Approaches (Bartholomew 2011) which stress the importance of pre‐testing interventions. Difficulties were encountered in obtaining full intervention manuals (although some intervention materials were provided via contact with authors). This was a limiting factor in understanding the more specific components of the interventions. This also has implications for the repeatability and therefore the reliability of these studies.

A major finding from this review is the lack of consistency in the design of interventions in terms of their intensity and optimum length. Indeed, some studies did not report these parameters. We are not yet at a stage of understanding in oral health research to be able to draw conclusions about the key components needed for effective behavioural interventions for caries prevention in primary school aged children. It may be beneficial to draw on the advances currently being made in the field of behavioural science, largely driven by health psychology. Additionally, the social determinants of health is a key area for all research seeking to reduce disparities in health across socioeconomic strata.

Potential biases in the review process

The number of databases searched electronically and journals handsearched was comprehensive. Through the initial title and abstract screening and the full secondary screening, it is felt that all relevant studies have been included in the review. During the review process, we had greater success in contacting authors of more recent studies. This lead to clarification of studies for the purposes of study screening as well as data extraction. Through contact with authors, some intervention materials were also obtained meaning that we gained a more thorough understanding of these interventions.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review partially supports reviews which have examined oral health education interventions (Kay 1996; Kay 1998; Watt 2001) in finding short term improvements in the oral health knowledge of children and adults. A recent review conducted by Harris 2012 around chairside interventions for dietary behaviour change found that the reporting of interventions was greatly varied, with "no studies concerned with dietary change aimed at preventing tooth erosion". The primary focus of the interventions was fruit, vegetable and alcohol consumption. Additionally only one study included by Harris 2012 included a cost analysis for the intervention. Cost benefit analysis is highlighted within this review as important and under‐researched in this field.

A review examining interventions aimed at preventing childhood obesity (Waters 2011) also highlighted the difficulty in determining which component of the intervention was most beneficial, although key areas to promote were identified. Waters 2011 concludes that there is a need to strengthen study and evaluation design as well as the reporting of procedures and intervention implementation. Waters 2011 similarly refers to the need to understand the longer term impacts and the cost of interventions.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Based on this review there is limited evidence that primary school‐based behavioural interventions that promote twice daily toothbrushing and reduce snacking on sugary foods can prevent caries by improving children's oral hygiene. There is some evidence to suggest that these interventions may have a positive impact upon children's knowledge and on plaque removal.

Recognition of the social determinants of health and the pivotal role of the home environment are likely to be key aspects enhancing design and delivery of future interventions (active involvement of parents was found to impact intervention effectiveness in this review) helping to ensure strong links with the home. The results presented within this review suggest that the home is an important influence on clinical outcomes (plaque) in these types of intervention. Through the inclusion of an 'active' home component, the efficacy of primary school‐based behavioural interventions may be increased. However, due to the small number of included studies, it is not possible to determine the extent of this impact. This is an area recommended for further research.

A greater emphasis should be placed on embedding healthy morning and bedtime routines, focusing on relevant environmental cues within the home. Future intervention design should target development of behavioural transition moving from knowledge acquisition to the adoption of habitual behaviour (i.e. knowledge, skill development, reinforcement and practice behaviours in a relevant setting). As yet it is unclear which BCTs are the most effective for dental health related behaviours. Attention must be paid to theoretical detail regarding behaviour change; failure to do so may limit the potential of interventions to bring about sustained health improvement.

This review highlighted that the dietary component of combined oral health behavioural interventions is less developed and tends to come secondary to oral hygiene. There appears to be a lack of integration between dietary and hygiene messages. Only one study had a more active approach to diet and nutrition. Future practice should ensure a balance between these components. Inter‐professional working may help facilitate such practice.

From a sustainability and cost perspective, programmes should be designed to be integrated into current oral health strategies and school curricula using models such as 'train the trainer'. Such models do not rely on specialist staff and can thus be implemented in future years following the end of the evaluated intervention. The interventions in this review were predominantly delivered by teachers however, it was not reported how these teachers were trained.

Implications for research.

This review highlights that there are questions still to be answered around how to effectively change the behaviour of primary school children and their families to reduce dental caries. In terms of expanding the evidence base, future studies should seek to demonstrate the rigorous standards in the design, implementation, delivery and reporting of these interventions thus aiding subsequent systematic reviews in this area. This should result in a more comprehensive interpretation of the specific behavioural components of interventions. As with intervention components, the same weight should be applied to the measurement and reporting of clinical and behavioural outcomes. Within this review the primary aim of the interventions was to change behaviour; however the focus of measurement was based on clinical outcomes that detect the results of lack of behaviour targeted (e.g. poor gingival health and high plaque levels). Only one study reported behaviour measures (Worthington 2001) being collected as part of the study.

New clinical trials conducted in primary schools aimed at reducing caries should include.

Outcomes that allow assessment of dental caries effect (start age 5 to 6 years to allow effect estimates for first permanent molar teeth) as well as behaviour change.

Cost effectiveness measures.

Recognised staged approach to designing and evaluating complex interventions such as the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines for complex intervention.

Theory‐based interventions and incorporate BCTs; reporting of interventions should detail their length.

Multi‐disciplinary teams in addition to dental expertise including health psychologists, dieticians and health economists.

Sample sizes sufficiently powered to measure clinical and behavioural outcomes appropriately.

A significant period of follow‐up (e.g. 2 to 3 years) in order to measure long term impact on caries outcomes.

Data reported according to potentially relevant factors such as age, gender and socio‐economic status allowing for subgroup analysis.

In addition to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) (CONSORT 2010), reporting should detail.

Intervention length, intensity and frequency as well as specific components.

Intervention deliver(s) and information about the setting.

Statistically, future trials should report mean and standard deviations for each outcome, as well as number of participants at each time point in order to improve the opportunity for meta‐analyses to be performed in future systematic reviews.

Increasingly there is an awareness of the publication of intervention manuals in behavioural research. Journals such as Addiction now publish such materials online to supplement study reports. This could make for a more comprehensive evaluation of behavioural interventions in future systematic reviews.

For all but incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and blinding of participants studies were most commonly assessed to have an unclear risk of bias due to limited reported information. In addition to problems highlighted around the reporting of interventions, there is also an ongoing need to address the reporting of randomisation methods and the details of participant blinding.

Within the measurement of behavioural outcomes, and to a lesser extent, clinical outcomes, there is a lack of standardization around best measures. Future research should look at the need to develop a common core indicator set of behaviour measurements for use in dental public health intervention studies.

Key points

The evidence of effectiveness of primary school‐based behavioural interventions on clinical and behavioural oral health outcomes is limited.

All the included studies contained behavioural interventions which lacked a theoretical basis. They also exhibited limited BCTs; those identified tended to relate to information giving rather than support.