Abstract

Our research aims to understand the adaptive—ergo potentially metastatic—responses of prostate cancer to changing microenvironments. Emerging evidence implicates a role of the polyaneuploid cancer cell (PACC) state in metastasis, positing the PACC state as capable of conferring metastatic competency. Mounting in vitro evidence supports increased metastatic potential of cells in the PACC state. Additionally, our recent retrospective study revealed that PACC presence in patient prostate tumors at the time of radical prostatectomy was predictive of future metastasis. To test for a causative relationship between PACC state biology and metastasis in prostate cancer, we leveraged a novel method designed for flow cytometric detection of circulating tumor cells (CTC) and disseminated tumor cells (DTC) from animal models. This approach provides both quantitative and qualitative information about the number and PACC status of recovered CTCs and DTCs. Specifically, we applied this approach to the analysis of subcutaneous, caudal artery, and intracardiac murine models. Collating data from all models, we found that 74% of recovered CTCs and DTCs were in the PACC state. Furthermore, in vivo colonization assays proved that PACC populations can regain proliferative capacity at metastatic sites. Additional in vitro analyses revealed a PACC-specific partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition phenotype and a prometastatic secretory profile, together providing preliminary evidence of prometastatic mechanisms specific to the PACC state.

Implications: Considering that many anticancer agents induce the PACC state, our data position the increased metastatic competency of PACC state cells as an important unforeseen ramification of neoadjuvant regimens, which may help explain clinical correlations between chemotherapy and metastatic progression.

Introduction

Though early detection of prostate cancer favors the diagnosis of eradicable localized disease, metastatic prostate cancer remains lethal and incurable. Metastatic disease arises when metastatically competent cells in the primary tumor (i) invade local tissue, (ii) intravasate into the vasculature, (iii) survive circulatory transit, (iv) extravasate into a distant organ, and (v) colonize that organ (1). In 2024, it is projected that more than 35,000 men in the United States will die from metastatic prostate cancer (2). Clearly, there remains a large need for a greater understanding of the metastatic process within the prostate cancer field. One approach relies on understanding how tumor microenvironmental stressors constantly influence the adaptive potential of cancer cells, potentially driving phenotypes with increased metastatic potential.

Emerging evidence has highlighted the role of the polyaneuploid cancer cell (PACC) state as a phenotype of metastatically competent cells (3–7). Cells in the PACC state (also termed polyploid giant cancer cells, multinucleate giant cells, and pleomorphic cells, among other names) exhibit a transient and adaptive cellular response to genotoxic stress. Most notably, the PACC state is characterized by an increase in genomic content coincident with an indefinite pause in cell division (8). Multiple mechanisms of PACC formation have been reported, including endocycling, endomitosis, and cell fusion (5). In our prostate cancer models, cultured cells induced to enter the PACC state do so via adoption of an endocycle: an interphase-restricted cell cycle following a canonical stress-induced G2–M pause (9–11). This alternative cell cycle pattern consists of subsequent cycles of G1, S, and G2 phases without any intervening M phases (12). In addition to explaining the increase in genomic content and lack of cell division, an endocycle also explains the nuclear morphology and cytoplasmic enlargement we observe in our PACC state model, which together create a distinct phenotype we and others use to identify PACCs in cell culture and histopathological contexts. Indeed, these morphologic features have been broadly relied on as pseudomarkers of the PACC state phenotype across various cell lines (prostate, breast, ovarian, brain, and melanoma, among others) in response to multiple classes of anticancer stressors (13–15). PACC populations remain nondividing for an extended period of time (on the order of several weeks to months) before reengaging a classic cell cycle capable of repopulating cultures with non-PACCs of typical ploidy, size, and division kinetics (5).

We and others have published data supporting that cells in the PACC state have increased metastatic potential. Functionally, Xuan and colleagues (16, 17) have reported that breast cancer MDA-MB-231 PACCs exhibit a persistent migratory phenotype driven by an enriched vimentin (VIM) filament network. More recently, we have shown that prostate cancer PC3 PACCs demonstrate an identical motility phenotype to that observed by Xuan and colleagues (18) that can be influenced by the presence of a chemotactic gradient. In mice, Zhang and colleagues performed serial metastatic passage of PC3 cells and showed that each cycle of metastatic selection increased the percentage of PACC state cells within tumors as well as the tumors’ metastatic rates.

Clinical research has also indicated a potential role for PACCs in contributing to metastasis. Stromal-invasive PACCs identified via histology were more frequently found in patients with metastatic (vs. nonmetastatic) ovarian cancer: PACCs were found in 18/21 high-grade primary tumors from patients with metastases but in only 6/26 low-grade primary tumors from patients without metastases (19). Similar trends have been reported in prostate cancer. In a phenomenological report of 27 PACC-positive tumors, all 27 were scored as Gleason 9 or 10 disease, indicating that presence of PACC-state cells is associated with more aggressive disease (20). An independent study published nearly identical findings: of 30 patients presenting with PACC-positive cases of prostate cancer, all 30 had Gleason score 9 or 10 disease, and 11 patients were dead at a median of 8 months after diagnosis (21). Furthermore, the Michigan Legacy Tissue Program identified PACCs as present in all 16 osseous and nonosseous metastatic sites of five randomly selected cases of prostate cancer (22). Most recently, we reported that the presence of PACCs in the primary tumor at the time of radical prostatectomy was predictive of future metastatic progression in men with prostate cancer (23). These studies indicate a definite correlation between PACC-state biology and metastasis, yet it remains unknown if PACCs directly contribute to metastatic progression.

To test for a distinctly causative relationship between PACC-state biology and metastasis in prostate cancer, we leveraged our recently published flow cytometry method designed for the detection of rare circulating tumor cells (CTC) and disseminated tumor cells (DTC) in metastatic mouse models (24). This approach provided both quantitative and qualitative information about the number and PACC status of metastasizing CTCs and DTCs recovered from animal tissues. Here, PACC status was defined by a stringent DNA content threshold: Only cells containing >4N DNA content were defined as PACCs, to exclude non-endocycling (G2-M checkpoint-paused) cells. We used various in vivo models to test the metastatic competency of cisplatin-induced PC3 PACCs versus PC3 non-PACCs at distinct steps of the metastatic cascade. We used spontaneous subcutaneous metastasis models to determine the proportion of CTCs and DTCs in the PACC state, by proxy assessing the invasion, intravasation, and circulatory survival capacity of circulating PACCs, as well as the extravasation capacity of distant organ-disseminated PACCs. Next, we designed caudal artery and tail vein injection models to specifically test the extravasation capacity of PACCs. Then we evaluated primary tumor growth kinetics of PACCs injected subcutaneously to distinctly test PACC colonization aptitude. Lastly, we performed intracardiac injections to test the circulatory survival, extravasation, and sequential colonization capacity of PACCs. The experimental details of each of these in vivo models are included in Supplementary Table S1. The number of cells analyzed via flow cytometry per mouse in each applicable model can be found in Supplementary Table S2. In all models, PACCs were induced with a 72-hour treatment of GI50 dose cisplatin, followed by 10-day recovery in fresh media.

Across the various models, 75% of CTCs and 72% of DTCs were in the PACC state. The two in vivo colonization assays proved that PACC populations can regain proliferative capacity following a period of growth latency, a phenomenon frequently observed and yet inadequately understood in the clinic. Further in vitro studies revealed a PACC-specific partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (pEMT) as a likely mechanism of increased metastatic behavior in PACCs. Notably, PACCs identified in the blood of human patients with prostate cancer also demonstrated a pEMT phenotype characterized by coexpression of epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM) and vimentin (VIM). Additionally, an analysis of PACC-conditioned media and its effects on non-PACC cells indicated that a PACC-specific prometastatic secretory phenotype may increase metastatic potential of non-PACCs. Together, our results provide strong evidence that the clinically observed links between PACC presence and risk of metastasis move beyond mere correlation. Our data point to a combination of direct and indirect mechanisms that together support a causative relationship between PACCs and increased metastatic risk in prostate cancer.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee. Human elements of this study were approved by the corresponding institutional review boards and were conducted in accordance with ethical principles founded in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent.

Cell culture

Experiments were performed using either the PC3-Luc prostate cancer cell line or the PC3-GFP-Luc prostate cancer cell line generated as previously described (24) and originally sourced from ATCC (RRID: CVCL_0035). All cells were cultured with RPMI 1640 media containing L-glutamine and phenol red additives (Gibco) and further supplemented with 10% Premium Grade Fetal Bovine Serum (Avantor Seradigm) and 1% 5,000 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic (Gibco) at 37°C and in 5% CO2. Cells were routinely lifted using TrypLE (Gibco) following a single PBS wash (Gibco). Cells were short tandem repeat profile authenticated and tested for Mycoplasma contamination twice yearly (Genetica). The last testing was completed in Summer 2024. All experiments were performed using cells fewer than 20 passages postthaw.

PACC induction

Cells were induced to enter the PACC state as previously described (11, 18). Briefly, 625,000 PC3 cells/T75 flask (scaled for appropriately for larger tissue culture vessels) were treated with 6 μmol/L cisplatin (MilliporeSigma) resuspended in sterile PBS supplemented with 140 mmol/L NaCl (Sigma-Aldrich) for 72 hours. When indicated, PC3-GFP-Luc cells were treated with 12 μmol/L cisplatin for 72 hours. After 72 hours, cisplatin-treated media was removed and replaced with fresh complete media. Cells were injected (or assayed, when appropriate) 10 days after cisplatin treatment removal, unless indicated otherwise. When indicted, cells were filtered through a 10-micron cell strainer (pluriSelect) to either isolate or remove PACCs, which are larger in size, from the other cells in the population, as previously described (18).

Animal models

All murine protocols were approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee. Owing to facility-wide mandate beyond experimenter control, all mice were fed a fenbendazole-containing chow. Most experiments were performed using 8- to 12-week-old male NOD/SCID gamma mice (The Jackson Laboratory, RRID: IMSR_JAX:005557). Intracardiac injections were performed on 6-week-old mice. Subcutaneously injected mice received a 100-μL injection of a 1:1 ratio of 10 mg/mL Matrigel (Corning) to 200,000 PC3-GFP-Luc cells suspended in complete media (or a mock suspension of media alone). Caudal artery-injected mice received a 100-μL injection of 200,000 cells suspended in sterile PBS. Tail vein-injected mice received a 100-μL injection of 200,000 PC3-GFP-Luc cells suspended in sterile PBS. Intracardiac-injected mice received a 100-μL injection of 50,000 PC3-GFP-Luc cells suspended in sterile PBS into the left ventricle. Tumor progression of subcutaneously injected mice was monitored via weekly caliper measurements, and tumor volume was calculated using the following formula: V = 0.5 × L × W2. Progression of caudal artery-injected, tail vein-injected, and intracardiac-injected mice was monitored via bioluminescence imaging (BLI), wherein mice were injected with 100 μL of 30 mg/mL luciferin (Regis) and imaged within 15 minutes using the IVIS Spectrum BLI imager (Revvity). At experimental endpoint, subcutaneous tumors were dissection, fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 hours, washed 3 × 5 minutes in PBS, and embedded into paraffin blocks. Sections that were 4-micron thick were mounted on slides, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, Sigma-Aldrich), and imaged using a 40× objective.

Pathology analysis

An automated methodology using QuPath software integrated with the StarDist extension was used to identify cancer cells with increased genomic content. Raw.ndpi image files of H&E-stained tumor tissue sections were analyzed using a Python script (complete with packages stardist, imagecodecs, tensorflow, pandas, and seaborn) to generate data on cell area, equivalent diameter, mean intensity, and solidity per identified cell. Raw.ndpi images were uploaded into QuPath, and the “Stardist H&E nucleus detection” script was modified at line 21 to include the file path to “he_heavy_augment.pb.” The script was run to identify individual nuclei. Nuclear area data from the Python script were used to set thresholds in QuPath for cell classification. Cells with a nuclear area less than 20 μm were classified as normal, and those equal to or greater than 20 μm were classified as cancer cells. The threshold to identify cells in the PACC state was set as those with an area greater than 3× the mean nuclear area of cancer cells. Circulatory and hematoxylin intensity thresholds were used to exclude noncellular entities. These single measurement classifiers were combined into a composite classifier to automatically categorize each segmented nucleus as belonging to a normal cell, cancer cell, or PACC.

CTC and DTC analysis

Primary tumor collection and processing

To dissociate primary tumors, tumors were dissected from freshly euthanized mice. Each sample was transferred to a Petri dish and minced into small pieces with a fresh, straight-edged razor blade. Each sample was transferred to a 14-mL round-bottom tube and suspended in 5 mL of a solution containing 250-μL collagenase/hyaluronidase (Stemcell Technologies), 375-μL DNase I (Stemcell Technologies) at 1 mg/mL, and 1.875-mL complete media. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes with shaking, before being pushed through a fresh 70-micron strainer placed over a 50-mL conical tube using the rubber end of a fresh 5-mL syringe plunger. Approximately 45 mL of complete media was used per sample to facilitate straining. Following straining, samples were centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature. The cell pellets were resuspended in 2 mL of ACK lysis buffer and incubated at room temperature for 3 minutes before adding 47 mL of complete media. Samples were then centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature, using a slow deceleration setting. Cell pellets were resuspended in 2 mL of complete media and stained with 10 μL of Vybrant DyeCycle Violet.

Blood collection and processing

CTC and DTC detection and analysis were performed as previously described (24). CTCs were defined as GFP-positive cells identified in mouse blood by flow cytometry. Approximately 500 μL of blood was collected via terminal tail bleed. Blood samples were individually transferred to 5-mL Eppendorf tubes and supplemented with ACK lysis buffer (Quality Biological) at a 1:4 blood/lysis buffer ratio. This solution was incubated on an end-over-end turner for 10 minutes. Following incubation, all samples were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1-mL complete media and stained with 1 μL of Vybrant DyeCycle Violet (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Bone marrow collection and processing

DTCs were defined as GFP-positive cells identified in mouse hind limb blood marrow or homogenized lung tissue by flow cytometry. Bone marrow was collected from the hind limb bones of freshly euthanized mice using a standard centrifugation protocol. Briefly, the right and left femurs and tibias of each mouse were dissected. The distal femoral epiphysial plate from each femur and the proximal tibial epiphysial plate from each tibia were removed to ensure access to red bone marrow. Bones were placed marrow-exposed side down in a 0.5-mL tube punctured with a small hole, which was then nested into a 1.5-mL tube. Tubes were centrifuged at maximum speed for 30 seconds to collect bone marrow into the 1.5-mL tube. All samples were resuspended in 200-μL PBS and then supplemented with 800 μL of ACK lysis buffer. This solution was incubated on an end-over-end turner for 10 minutes. Following incubation, all samples were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 3-mL complete media and stained with 15 μL of Vybrant DyeCycle Violet.

Lung collection and processing

To collect lung tissue, all five lobes of the lungs were dissected from freshly euthanized mice. Each sample was transferred to a petri dish and minced into small pieces with a fresh, straight-edged razor blade. Each sample was transferred to a 14-mL round-bottom tube and suspended in 5 mL of a solution containing 250-μL collagenase/hyaluronidase (Stemcell Technologies), 375-μL DNase I (Stemcell Technologies) at 1 mg/mL, and 1.875-mL complete media. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes with shaking, before being pushed through a fresh 70-micron strainer placed over a 50-mL conical tube using the rubber end of a fresh 5-mL syringe plunger. Approximately 45 mL of complete media was used per sample to facilitate straining. Following straining, samples were centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature. The cell pellets were resuspended in 2 mL of ACK lysis buffer and incubated at room temperature for 3 minutes before adding 47 mL of complete media. Samples were then centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature, using a slow deceleration setting. Cell pellets were resuspended in 2 mL of complete media and stained with 10 μL of Vybrant DyeCycle Violet.

Flow cytometry

The entire volume of all stained samples was run on the Attune NxT Acoustic Focusing Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a flow rate of 1,000 μL per minute. As previously described, it was critical to implement the following four modifications to our cytometer to accommodate analysis of cells in the PACC state: (i) The largest commercially available blocker bar was installed. (ii) An alternative optical configuration was used. (iii) Thresholding was performed using side scatter (SSC) rather than the standard front scatter (FSC). (iv) Area scaling factors of 0.6 were used for all lasers, rather than the standard area scaling factors. With these modifications, data were collected in the SSC, VL1-A, VL2-A, and BL1-A channels. All data were analyzed using FlowJo (BD), following our previously published analysis protocol (24).

Patient PACC analysis

Patient bone marrow sampling

Bone marrow aspirate samples were collected from patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer as previously described (25). Briefly, liquid biopsy samples were taken from participants at baseline and immediately started treatment on trial NCT01505868 which evaluated cabazitaxel with or without carboplatin. Samples were collected at MD Anderson at baseline prior to clinical trial treatment administration. The study was approved by the corresponding institutional review boards and was conducted in accordance with ethical principles founded in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent.

Patient sample processing

Samples were processed as previously described (25). In short, bone marrow samples were delivered overnight (7.5 mL) in Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubing (Streck) at the clinical sites and sent to the University of Southern California for processing. Erythrocytes were lysed via ammonium chloride, and the entire nucleated cell population was plated onto a specialized cell adhesion glass slide (Marienfield) at a density of 2 to 3 million cells per slide. Slides were stored at −80°C until use.

Immunofluorescent staining

Slides were fixed with 2% PFA for 20 minutes. Slides were then blocked with 2% BSA in PBS. Slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C with an antibody pan cocktail mixture consisting of mouse IgG1/Ig2a antihuman cytokeratins 1, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 13, 18, and 19 (Sigma, RRID: AB_476839), mouse IgG1 antihuman cytokeratin 19 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, RRID: AB-559775), mouse EpCAM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, RRID: AB_795876), and rabbit IgG antihuman vimentin (VIM): Alexa Fluor 488 (Cell Signaling Technologies, RRID: AB_10695459). Slides were then washed with PBS and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours with Alexa Fluor 555 goat antimouse IgG1 antibody (Invitrogen, AB_2535769) and counter-stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (D1306, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

High-content imaging and analysis

Slides were imaged as previously reported (26). Briefly, an automated high-throughput microscope equipped with a 10× optical lens was used to collect 2,304 images across the slide. An image analysis tool, available at https://github.com/aminnaghdloo/if_utils, was used to identify PACCs. Briefly, each fluorescent channel was segmented individually using adaptive thresholding and merged into one cell mask. PACCs were identified as having a nuclear diameter two times larger than the rare cell population (four times the area).

Single-cell picking

An Eppendorf TransferMan NK2 micromanipulator was used to collect the cell of interest in a 100 μmol/L micropipette. The cell was transferred into a sterile solution of 1× PBS. Single cells were stored at −80°C.

Copy number profiling

Copy number profiling from low-pass whole-genome sequencing samples was conducted as previously described (27, 28). Briefly, the commercially available WGA4 kit (Sigma) was used for single-cell whole-genome amplification. Sequencing libraries were prepared with the NEB Ultra FS II with 50 ng of starting material. Cells were sequenced at a depth of 1 to 2 million reads on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 (Fulgent, Inc.). Raw sequencing reads were aligned with BWA-MEM to the hg19 reference. Count data were segmented via the R package DNAcopy (version 1.70.0), and median values were reported for copy number ratio data.

Western blot

PC3 parental cells or PC3 PACCs were lysed with an appropriate amount of RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 minutes, rotating at 4°C. Lysates were spun at 21,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and the proteinaceous supernatant was stored at −80°C. Approximately 50 ng of protein (measured by Pierce BCA Protein assay, following manufacturer’s protocol; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to a 1:4 mixture of Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and 2-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad) and ran through a 4% to 20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX gel (Bio-Rad). The gel was transferred via Trans-Blot SD Semi-Dry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) onto a 0.2-micron Nitrocellulose Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer Pack using the 7-minute, 2.5-A, 25-V protocol designed for mixed molecular weights. The blot was blocked in Casein Blocking Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour at room temperature with shaking and then transferred to primary antibody diluted in casein and incubated overnight at 4°C with shaking. See Supplementary Table S3 for antibody dilutions and RRIDs. The blot was then washed three times for 5 minutes each with pH 7.4 Tris-buffered saline (Quality Biological) with 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma; TBST) and incubated in secondary antibody diluted 1:20,000 in casein for 1 hour at room temperature. The blot was then washed three times for 5 minutes with TBST and imaged using the Odyssey Western Blot Imager (LI-COR). See Supplementary Table S3 for antibody dilutions and RRIDs. Relative signal intensity was quantified via densitometry using ImageJ.

RT-qPCR

PC3 parental cells or PC3 PACCs were lysed using the QIAshredder Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s protocol. When indicated, PC3 parental cells or PC3 PACCs were incubated in parental-conditioned media or PACC-conditioned media for 24 hours prior to lysis. RNA was extracted from lysates using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was converted to cDNA (1-μg RNA per reaction) using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RT-qPCR reactions were performed using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad), following the manufacturer’s protocols, and assorted primers (Integrated DNA Technologies) at a concentration of 10 μmol/L. See Supplementary Table S4 for primers used. Data were collected using the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) using a standard cycling protocol. Gene expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin and calculated using the delta-delta Ct method. Each biological replicate reported is an average of three technical replicates.

Conditioned media generation

To generate PACC-conditioned media, PC3 PACCs were generated using our standard induction approach as described above, in a T150 tissue culture flask. On day 10 of treatment removal, exactly 20 mL of fresh complete media was added. Exactly 24 hours later, on day 11 of treatment removal, all 20 mL of PACC-conditioned media was collected. Media was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 minutes to remove any debris and then filtered through a 0.45-micron PES filter into 1-mL aliquots that were stored at −80°C.

To generate parental-conditioned media, 1,250,000 PC3 parental cells were seeded in a T150 tissue culture flask. After 12 hours, exactly 20 mL of fresh complete media was added. Exactly 24 hours later, all 20 mL of parental-conditioned media was collected. Media was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 minutes to remove any debris and then filtered through a 0.45-micron PES filter into 1-mL aliquots that were stored at −80°C.

Motility assays

Transwell assays

Transwell assays were performed using 6.5-mm, 8-micron, PES membranes. PC3 parental cells were seeded on the membrane at 100,000 cells/mL in 250 μL of complete media. After 12 hours, 500 μL of testing condition media was placed in the top and bottom wells for 24 hours. When indicated, recombinant IL6 was added to complete media at a concentration of 0.5 ng/mL. After 24 hours, membranes were washed in PBS and nonmigrated cells were removed from the top of the membrane with a cotton-tipped applicator. Membranes were fixed in 100% ice-cold methanol for 10 minutes and then stained in 0.5% crystal violet resuspended in 20% methanol for 10 minutes. Membranes were washed with deionized water to remove excess stain, and tiled imaging of the entire membrane was acquired with an EVOS FL Digital Inverted Fluorescence Microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a 4× objective. Image analysis to calculate percent area coverage was performed using the Phansalkar auto-local threshold method in ImageJ. Each reported biological replicate is an average of two technical replicates.

Wound healing assays

Wound healing assays were performed in 24-well tissue culture plates. PC3 parental cells were seeded at 100,000 cells/mL in 2.5 mL of complete media. After 12 hours, a P1000 pipette tip was used to create a scratch wound. After three washes with PBS, the scratch wounds were imaged on an EVOS FL Digital Inverted Fluorescence Microscope using a 4× phase contrast objective. Approximately 1 mL of testing conditioned media was added for 24 hours, after which the wounds were reimaged. Image analysis to calculate the percent wound closure was performed using the Wound Healing Size Tool Updated plug-in in ImageJ. Each reported biological replicate is an average of two technical replicates.

Single-cell tracking assays

Single-cell tracking assays were performed using live-cell, time-lapse microscopy in 24-well tissue culture plates. PC3 parental cells were seeded at 25,000 cells/mL in 2 mL of complete media. PC3 PACCs were seeded 5,000 cells/mL in 2 mL of complete media. After 12 hours, testing condition media was added for 24 hours. When indicated, tocilizumab (Selleck Chemicals) was added to complete media at a concentration of 2.5 μg/mL. When indicated, recombinant IL6 was added to complete media at a concentration of 0.5 ng/mL. An EVOS FL Digital Inverted Fluorescence Microscope was used to take 10× phase contrast images every 30 minutes for the 24-hour testing condition incubation. An on-stage environment chamber was used to maintain cell conditions at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 20% O2. Images were analyzed using the Manual Tracking and Chemotaxis Tool plug-ins in ImageJ image analysis software. All cells analyzed were randomly selected. Cells that underwent division, apoptosis, or moved out of frame were excluded from analysis.

Cytokine array

Cytokine analysis was performed using a 274-target chemiluminescent human cytokine antibody array, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Abcam ab198496). Nondiluted PACC-conditioned media and parental-conditioned media were tested, using nonconditioned media as a background control. Membranes were imaged using the ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad), and densitometry data were obtained using Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad) with signal-specific automatic background thresholding enabled. Background subtraction, positive control normalization, and differential secretion calculations were performed following the manufacturer’s protocol.

ELISA

Quantification of IL6 present in PACC-conditioned media was performed using an IL6 ELISA, following the manufacturer’s protocol (BioLegend, 430504), with the following alteration: sample incubation time was lengthened from 2 to 3 hours. PACC-conditioned media was diluted 1:4 in protocol buffer assay A prior to analysis. Data was collected using FLUOStar Omega Plate Reader (BMG LABTECH) at 405 nm.

Statistical analysis

Nonparametric t tests (Mann–Whitney) were performed to generate the reported P values. Power calculations were performed to determine the appropriate sample size for in vivo experiments, wherein an α value of 0.05 and a β value of 0.8 were used. NS, nonsignificant P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Data availability

Nearly all data generated in this study are available within the article and its supplementary data files. Detailed data about the 247-panel cytokine array are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Results

The majority of CTCs are in the PACC state

We used size-matched and time-matched subcutaneous murine metastasis models to measure the differential metastatic potential of PACCs through the evaluation of CTCs recovered from the blood. Our previously published analysis strategy (24) was used to quantify CTC presence based on GFP positivity. We validated that our stringent GFP+ gating parameters were appropriately exclusive of autofluorescent blood or bone marrow (relevant to DTC analysis) cells yet simultaneously captured known GFP+ cells dissociated from previously injected subcutaneous tumors (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Following CTC quantification, we analyzed DNA content to determine PACC status of each cell.

Mice were injected subcutaneously with a population of either parental PC3 cells or cisplatin-induced PACC-enriched PC3 cells confirmed to have PACC morphology by microscopy (a greatly enlarged and flattened cell surface area, an enlarged single nucleus, and an optically granulocytic cytoplasm) as well as increased ploidy by flow cytometry (Figs. 1A and 2A). In the time-matched model, blood from each mouse was collected and analyzed 6 weeks after tumor cell injection. In total, three CTCs were recovered, two of which were in the PACC state (66%; Fig. 1D; Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

Time-matched, subcutaneous injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population versus PACC-enriched population. A, Light microscopy photos and flow cytometric ploidy analysis of injected cells per injection group. B, Tumor volume and tumor weight measurements per injection group at experimental endpoint. C, Representative H&E photos of primary tumors per injection group and quantification of normalized PACC proportion, determined by automated QuPath measurement of nuclear sizes. D, Enumeration of CTCs sourced from the blood of each animal and quantification of >4N CTCs versus ≤4N CTCs. E, Enumeration of DTCs sourced from the bone marrow of each animal and quantification of >4N DTCs versus ≤4N DTCs.

Figure 2.

Size-matched, subcutaneous injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population versus PACC-enriched population. A, Light microscopy photos and flow cytometric ploidy analysis of injected cells per injection group. B, Tumor volume and tumor weight measurements per injection group at experimental endpoint. Kaplan–Meier curve indicating when mice reached tumor size-based experimental endpoint. C, Representative H&E photos of primary tumors per injection group and quantification of normalized PACC proportion, determined by automated QuPath measurement of nuclear sizes. D, Enumeration of CTCs sourced from the blood of each animal and quantification of >4N CTCs versus ≤4N CTCs. E, Enumeration of DTCs sourced from the bone marrow of each animal and quantification of >4N DTCs versus ≤4N DTCs.

At experimental endpoint, parental-injected mice produced larger tumors than PACC-injected mice (Fig. 1B) most likely due to the transiently nonproliferative phenotype of PACCs abundant in the PACC-enriched population. At experimental endpoint, the proportion of PACCs to non-PACCs in each tumor equilibrated to similar levels (Fig. 1C, determined by normalized QuPath automated analysis of sample-matched nuclear sizes). This observation aligns with additional data collected when validating the GFP+ gating parameters presented in Supplementary Fig. S1A: When analyzing the ploidy of the GFP+ dissociated tumor cells therein, we found that PACC proportions between parental-injected mice and PACC-injected mice equilibrated to around 20% 6 weeks after injection (Supplementary Fig. S1B).

To increase the number of recoverable CTCs, we repeated the experiment using a tumor size-matched model, in which the experimental endpoint of each mouse was independently determined. Blood was collected and analyzed when tumors reached approximately 350 mm3 (Fig. 2B). Again, at experimental endpoint, the proportion of PACCs to non-PACCs in each tumor equilibrated to similar levels (Fig. 2C, determined by normalized QuPath automated analysis of sample-matched nuclear sizes). In total, 33 CTCs were recovered, 25 of which were in the PACC state (75%; Fig. 2D; Supplementary Fig. S4). Altogether, these data confirm that PACCs can survive as CTCs in the context of spontaneous metastasis and the majority of CTCs recovered in this context are in the PACC state.

The majority of DTCs are in the PACC state

The same two subcutaneous models used to measure blood CTCs were also used to quantify and characterize DTCs recovered from hind limb bone marrow. Across both models, a majority of the DTCs recovered were in the PACC state. In the time-matched model, eight bone marrow DTCs were recovered, six of which were in the PACC state (75%; Fig. 1E; Supplementary Fig. S3). In the size-matched model, 10 DTCs were recovered, 8 of which were in the PACC state (80%; Fig. 2E; Supplementary Fig. S5).

Subcutaneous tumor models are useful for investigating multiple steps of the metastatic cascade (i.e., invasion, intravasation, survival in the circulation, and extravasation) within one animal. However, they limit the ability to specifically query differential extravasation capacity between cell phenotypes owing to potential upstream bottlenecks that may differentially skew the numbers of each cell type surviving in the circulation. To directly measure the differential extravasation potential of PACCs, we used a caudal artery injection model. Mice were injected with a population of either parental cells or PACC-enriched cells confirmed to have increased ploidy at the population level (Fig. 3A). Caudal artery injection introduces cells directly into the vasculature and directs them to the hind limb bone marrow capillaries and lung capillaries, wherein they become lodged due to size. After 72 hours, lodged cells have either been cleared from the vasculature or have extravasated into surrounding tissue. After 72 hours, it can be assumed that any cells recoverable from digested organs are bona fide DTCs that underwent successful extravasation. Accordingly, bone marrow and lung tissue were collected and analyzed 3 days after injection (Fig. 3B). After 72 hours, 81 DTCs were recovered from the bone marrow, 59 of which were in the PACC state (73%; Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. S6). A total of 132 DTCs were recovered from the lung, 111 of which were in the PACC state (84%; Fig. 3D; Supplementary Fig. S7). These data suggest that cells in the PACC state have increased extravasation potential compared with their non-PACC counterparts. As such, PACCs are uniquely adept not only at entering and surviving within the circulatory system as CTCs but also at extravasating into secondary site tissues.

Figure 3.

Caudal artery injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population versus PACC-enriched population. A, Light microscopy photos and flow cytometric ploidy analysis of injected cells per injection group. B, Representative BLI images capturing the cellular distribution and signal intensity immediately following caudal artery injection and 72 hours following caudal artery injection. C, Enumeration of DTCs sourced from the bone marrow of each animal and quantification of >4N DTCs versus ≤4N DTCs. D, Enumeration of DTCs sourced from the lung tissue of each animal and quantification of >4N DTCs versus ≤4N DTCs.

PACCs can be found at a low baseline level (around 5%) in parental populations of the PC3 cell line and are generally thought to reflect the stress inherent to cell culturing. Therefore, it is possible that PACC state DTCs recovered from parental-injected mice result from selection of preexisting PACCs in the parental population and reflect the increased metastatic risk of cells in the PACC state. Alternatively, it is possible that stress experienced during the metastatic process induced non-PACCs in the parental population to access the PACC state in vivo. To investigate the source of the PACC state DTCs recovered from parental-injected mice, we performed a tail vein experiment comparing a population of parental cells (inherently containing a small percentage of PACC) with a population of non-PACC–enriched cells generated by size filtering a parental population through a 10-micron filter to remove PACCs. Mice were injected with either unfiltered (parental) cells or filtered (non-PACC enriched) cells confirmed to contain fewer cells of increased ploidy (Supplementary Fig. S8A). After 72 hours, lung tissues were collected and analyzed for DTCs. Across all mice, 566 DTCs were recovered, 328 of which were in the PACC state (58%; Supplementary Fig. S8B). As seen in our previous experiments, a majority of recovered DTCs are in the PACC state. When comparing the proportion of lung DTCs in the PACC state between the two injection groups, we found no difference (unfiltered: 58% vs. filtered: 57%; Supplementary Fig. S8C). These data show that a reduction in the percentage of baseline PACCs present in the parental population does not change the percentage of PACCs present among recovered DTCs, suggesting a possibility that non-PACCs in the parental population may access the PACC state in vivo. Such a transition could occur in response to stressors experienced during circulatory transit, such as anoikis, fluid shear stress, or changes in oxygen tension from atmospheric to physiologically normoxic levels.

PACCs are capable of colonization following a latent period

Clinically relevant metastatic potential requires colonization capacity. In vitro, cells induced to enter the PACC state become transiently nonproliferative, existing in a nondividing state. It has been observed that PACCs can survive in this state for months, a phenomenon compatible with that of metastatic tumor cell dormancy. Following a period of nonproliferative latency, some cells within the in vitro PACC-induced population return to a proliferative mitotic cell cycle, consistent with delayed metastatic outgrowth frequently observed in human patients. To initially test the short-term survival status of PACCs when introduced in vivo, PACC-enriched cells were injected into the tail vein of mice (Supplementary Fig. S9A). The lungs were analyzed for surviving DTCs in the PACC state after 21 days (Supplementary Fig. S9B). Pooling mice together, 35 DTCs in the PACC state were found still surviving in lung tissue (Supplementary Fig. S9C).

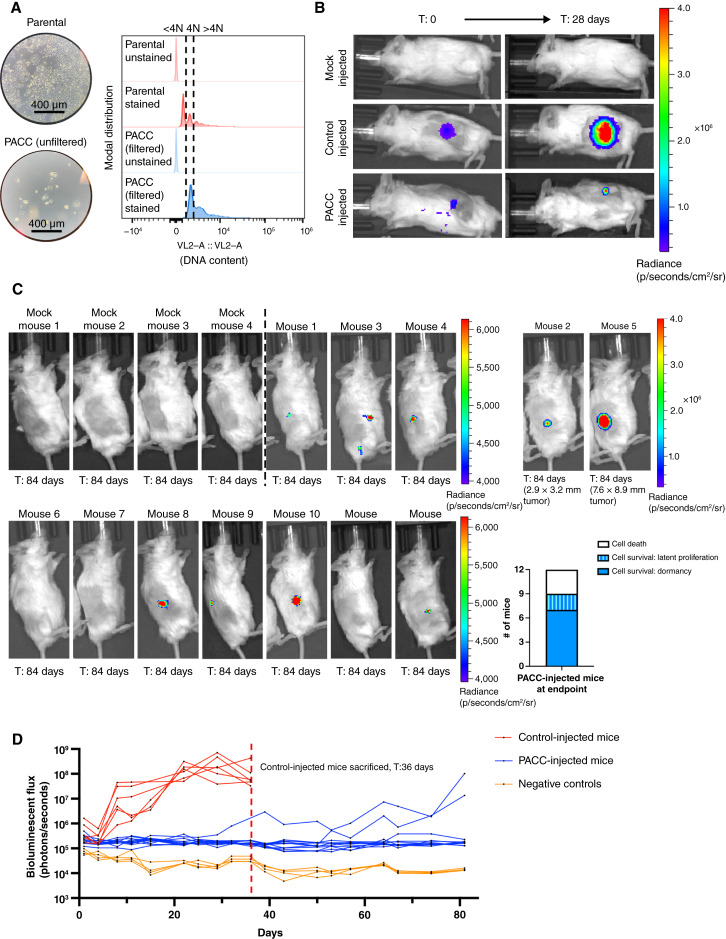

Satisfied that PACCs do not immediately reenter a proliferative cell cycle nor immediately die when introduced in vivo, we sought to understand the long-term survival and growth kinetics of PACCs in vivo. Mice were subcutaneously injected with either a population of parental cells (serving as a positive control of injection technique and a benchmark of PC3 colonization potential) or a population of size-filtered PACCs and monitored for 12 weeks using bioluminescent imaging (BLI). Prior to injection, the size-filtered PACC population was confirmed to contain only cells of at least 4N or greater ploidy (Fig. 4A). Within 4 weeks, 6/6 positive control mice developed appreciable tumors and showed the expected marked increase in BLI flux. At that time, 0/12 PACC-injected mice presented with palpable tumors, but BLI showed evidence of tumor cell survival at the injection site (Fig. 4B). Positive control mice reached ethical tumor burden and were euthanized 6 weeks postinjection. PACC-injected mice were monitored for an additional 6 weeks before they were euthanized. At experimental endpoint, all PACC-injected mice showed greater levels of BLI flux than negative controls. Moreover, 7/12 PACC-injected mice showed BLI evidence of nonproliferative tumor cell survival localized to the injection site, and an additional 2/12 PACC-injected mice had developed slow-growing palpable subcutaneous tumors following a multiweek latent phase (Fig. 4C and D).

Figure 4.

Subcutaneous injection of PC3-Luc parental population vs. size-filtered PACC population. A, Light microscopy photos and flow cytometric ploidy analysis of injected cells per injection group. B, Representative BLI images capturing the cellular distribution and signal intensity immediately following subcutaneous injection and 28 days following subcutaneous injection. C, BLI images of 4 mock-injected and 12 PACC-injected mice 82 days following subcutaneous injection; note the different scale for mouse 2 and mouse 5. Quantification of the status of injected cells across all 12 PACC-injected mice at experimental endpoint. D, Weekly BLI flux of all experimental mice over 84 days.

We next used an intracardiac injection model to test the dormancy and colonization kinetics of PACCs in a metastasis-relevant context (i.e., following survival in the circulation and subsequent extravasation). Mice were injected directly into the left ventricle with either a population of parental cells (serving as a positive control for both injection technique and PC3 colonization potential at distant sites) or a population of PACC-enriched cells confirmed to have increased ploidy at the population level (Fig. 5A). Within 6 weeks, 6/7 positive control mice had evidence of liver and/or bone metastases by BLI, based on the anatomic location of positive signal and confirmed by direct observation of liver nodules at the time of dissection. At that time, 0/7 PACC-injected mice showed any BLI-positive lesions (Fig. 5B). Positive control mice reached ethical tumor burden and were euthanized between 6 and 14 weeks. PACC-injected mice were monitored for an additional 5 weeks. By experimental endpoint, 4/7 PACC-injected mice had showed evidence of liver metastases by BLI, based on anatomic location of positive signal, but none of these metastases reached a BLI flux threshold indicative of rapidly progressive disease (Fig. 5C and D). Taken together, these data indicate that PACCs are capable of both long-term in vivo survival in a nonproliferative state and return to a proliferative phenotype able to seed metastatic colonization following a period of dormancy.

Figure 5.

Intracardiac injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population versus PACC-enriched population. A, Light microscopy photos and flow cytometric ploidy analysis of injected cells per injection group. B, Representative BLI images capturing the cellular distribution and signal intensity immediately following intracardiac injection and 42 days following intracardiac injection. C, BLI images of 4 mock-injected and 4/7 PACC-injected mice that showed their first evidence of colonization between 91 and 112 days post intracardiac injection. D, Weekly BLI flux of all experimental mice over 135 days. Quantification of the status of injected cells across all injected mice at experimental endpoint.

PACCs display a partial EMT phenotype

Previously published in vitro studies by our lab and others’ show that cells in the PACC state display enhanced metastatic phenotypes including motility, chemotaxis, and invasion (17, 18). The present work shows that most CTCs and DTCs recovered across various metastatic models are in the PACC state, supporting the hypothesis that PACCs promote a tumor’s metastatic potential through cell-intrinsic metastatic competency. In the past decade, it has been increasingly reported that metastatic competency relies heavily on a pEMT phenotype. pEMT (also called hybrid EMT and mixed EMT, among others) is a nonbinarized variant of the canonically mutually exclusive epithelial versus mesenchymal phenotypes. As such, pEMT is characterized by the coexpression of proteins typically associated with only epithelial or mesenchymal profiles. We found that at the RNA level, PC3 PACCs show an increase in ZEB1, VIM, and CLDN1 expression and no difference in SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, CDH2, CDH1, or EPCAM expression (Fig. 6A). At the protein level, PACCs show an increase in VIM, CDH2, CLDN1, and CDH1 expression, a decrease in SNAI1, SNAI2, and EPCAM expression, and no change in low-level TWIST1 expression (Fig. 6B; uncropped blots in Supplementary Fig. S10A–S10C). High coexpression of VIM (a classic mesenchymal marker) and CLDN1 (a known epithelial marker) in PACCs indicates a pEMT phenotype. Absence of inverse expression between PACC CDH2 (a classic mesenchymal marker) and PACC CDH1 (a classic epithelial marker) also supports a PACC-specific pEMT phenotype (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

PACCs have a pEMT phenotype. A, RNA expression of a panel of EMT markers by RT-qPCR in a PC3-Luc parental population vs. size-filtered PACC population, in which each biological replicate reported is an average of three technical replicates. B, Protein expression of a panel of EMT markers by Western blot in a PC3-Luc parental population versus size-filtered PACC population and respective quantification by densitometry. Note that the bands for CDH1, VIM, SNAI. and CLDN1 are sourced from the same blot and use the same actin band for protein loading normalization calculations during densitometry. C, Summary table of RNA and protein expression. D, Representative immunofluorescent images of PACCs identified as DTCs in the bone marrow of a patient with castrate-resistant metastatic prostate cancer, stained for DAPI, an epithelial -origin cocktail, and VIM. CNV analyses of the corresponding single cells.

To evaluate the pEMT status of metastatic PACCs in a clinical context, we stained cancer cells isolated from the bone marrow of patients with prostate cancer (29) with (i) a DNA content dye, (ii) a cocktail of epithelial-specific markers (including human cytokeratins 1, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 13, 18, 19, and EpCAM), and (iii) vimentin. Cells with 4× greater than average nuclear area determined by DNA stain were deemed PACCs. Because here, PACC state status was determined using DNA content, it was pertinent to enable the exclusion of other naturally occurring noncancerous polyploid cells (such as megakaryocytes) from our analyses. Accordingly, we used single-cell copy number analysis to confirm that cells deemed PACCs were indeed tumor derived (Fig. 6D). Of 44 patients, 33 were found to have PACC cancer cells. Of those 34, 6 patients were found to have pEMT PACC cancer cells positive for both pan-epithelial (including EPCAM) and VIM stains (representative images: Fig. 6D). These data indicate that our observations of a PACC-specific pEMT process are not limited to prostate cancer cell models and are at times observable directly in patients with prostate cancer. This result suggests that PACC-specific pEMT remains a plausible mechanism for increased metastatic competency among prostate cancer cells in the PACC state.

PACCs have a prometastatic secretory profile

We recently reported that the presence of PACCs in the primary tumor at the time of radical prostatectomy is predictive of future metastatic progression in men with prostate cancer (23). In addition to the hypothesis that PACCs might promote a tumor’s metastatic potential because PACCs themselves are more metastatic, PACCs might otherwise promote a primary tumor’s metastatic potential by increasing the metastatic phenotype of surrounding non-PACC tumor cells. To test this alternative model, we evaluated the motility phenotype of non-PACC cells cultured in PACC-conditioned media compared with control parental cell-conditioned media. We found that PACC-conditioned media increases non-PACC motility by two common motility assays (Fig. 7A; Supplementary Fig. S11A), which was not accompanied by an increased transcriptional EMT phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S11B).

Figure 7.

PACCs have a prometastatic secretory profile. A, Transwell assay comparing the differential motility of a PC3-Luc population exposed to parental-conditioned media vs. PACC-conditioned media, in which each reported biological replicate is an average of two technical replicates. B, Cytokine array comparing the relative abundance of 274 cytokines of interest in parental-conditioned media versus PACC-conditioned media. C, Transwell assay comparing the effect of addition of recombinant IL6 on the motility of a PC3-Luc population. D, Single-cell tracking comparing the effects of addition of recombinant IL6 and/or tocilizumab on the motility of a PC3-Luc population.

We performed a cytokine array on parental cell–conditioned media and PACC-conditioned media to identify abundant cytokines differentially secreted by PACCs. IL6 was the strongest candidate for further study (Fig. 7B). We measured the concentration of IL6 in PACC-conditioned media by ELISA assay and found that an addition of a similar concentration of IL6 to that identified in the PACC-conditioned media was sufficient to produce increased motility in non-PACCs (Fig. 7C). This increased motility phenotype was abrogated by the inhibition of the IL6 receptor (IL6R) via the addition of tocilizumab (Fig. 7D). We and others have previously published that PACCs are more motile than non-PACCs (17, 18). To rule out the possibility that increased PACC motility is the result of autocrine-acting IL6, we applied tocilizumab to PACC samples and observed no change in PACC motility (Supplementary Fig. S11C). These data suggest that in addition to cell-autonomous prometastatic effects, PACCs contribute to a tumor microenvironment that elicits prometastatic phenotypes in non-PACC tumor cells.

Discussion

Recent studies demonstrating the clinical relevance of cells in the PACC state as reliable predictors of the risk of cancer severity and metastasis (19–23) raise important questions about the roles that PACCs may play in metastatic progression. For example, accession of the PACC state may increase intrinsic prometastatic features, making PACCs more metastatically competent than their non-PACC counterparts. Alternatively, PACCs may increase the metastatic competency of nearby non-PACCs via a paracrine-functioning prometastatic phenotype, or perhaps PACCs are merely uninvolved “third-party” cells incidentally produced by an unknown stimulus that itself is driving metastatic risk via an otherwise unrelated mechanism. Here, we sought to test for a direct causative link between PACC presence and metastatic propensity in prostate cancer. We tested for the presence of PACCs throughout various steps of the metastatic cascade using distinct metastatic mouse models.

When testing the blood for metastatic cells capable of invading, intravasating, and then surviving in the circulation, we found that 75% of recovered CTCs were in the PACC state (27/36 CTCs). When testing the bone marrow for metastatic cells capable of invading, intravasating, surviving, and then extravasating, we found that 77% of recovered DTCs were in the PACC state (14/18 DTCs). It was pertinent to test both time-matched and size-matched subcutaneous models to account for any potential effects that the differing growth kinetics of the two injections groups might have had on the initiation of the angiogenic switch. Appropriately, an increased number of total CTCs and DTCs were recovered in the size-based experiment (which at endpoint had larger primary tumors than the time-based experiment).

Across our subcutaneous models, we did not consistently find that PACC-injected mice produced a larger number of metastasizing cells. Similarly, we did not consistently find that PACC-injected mice yielded a greater proportion of >4N metastasizing cells over total recovered metastasizing cells compared with parental-injected mice. Analysis of the proportion of PACCs within the tumors of each injection group at experimental endpoint offered a potential explanation: the initial difference between the proportions of PACCs within each injected population (less than 5% PACCs among parental populations but more than 50% among PACC-enriched populations) equilibrated within 6 weeks. A decrease in PACC proportion over time in the PACC-enriched tumors could be caused by a delayed return to mitotic cell cycle among PACCs or a presence of a small number of mitotic non-PACCs in the injection population. An increase in PACC proportion over time in the parental population could be caused by the accumulation of tumor microenvironmental stressors in vivo, such as hypoxia, which initiate PACC state entry (15, 30, 31). Given the DNA content equilibrium in primary tumors between injection groups at experimental endpoint, it is not surprising that PACC-injected animals occasionally yielded DTCs with non-PACC DNA content or that parental-injected animals occasionally yielded DTCs with PACC DNA content. We hypothesize that any differences between the proportions of >4N recovered cells over total recovered cells between injection groups in our subcutaneous models are merely a reflection of random chance.

The similarity between the proportions of PACCs found among the recovered CTCs and the recovered DTCs (75% vs. 77%) in the subcutaneous tumor models does not adequately support a conclusion of increased extravasation potential among cells in the PACC state. To specifically test for increased extravasation potential among PACCs, we used a caudal artery injection model that allowed for analysis of bone marrow, the most common site of prostate metastasis in patients. When testing the bone marrow for metastatic cells capable of extravasation, we found that 73% of recovered DTCs were in the PACC state (59/81 DTCs). When testing the lung for metastatic cells capable of extravasation, we found that 84% of recovered DTCs were in the PACC state (111/132 DTCs). These data indicate that cells in the PACC state have increased extravasation potential compared with non-PACCs. We and others have previously published that PACCs demonstrate both persistent chemotactic-driven motility and functional deformability, phenotypes which may explain their increased ability to extravasate (17, 18). An alternative explanation for our caudal artery results (which highlights the observation that mice injected with PACCs did not display a greater proportion of >4N DTCs than those injected with parental cells) supposes that extravasated non-PACCs entered the PACC state after entering secondary organ tissue owing to the inherent stressors of that organ site. When comparing the portion of PACCs found among total DTCs in the lungs of animals injected with parental populations with low-level baseline PACCs versus a PACC-depleted population, we found that reduction of baseline PACCs present does not change the percentage of PACCs present among recovered DTCs. These data suggest that it is possible that stress experienced during the metastatic process may induce non-PACCs to access the PACC state in vivo, but further study is necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Interestingly, in the caudal artery model, most of the bone marrow DTCs were sourced from parental-injected mice (though the majority of those DTCs were in the PACC state), but the majority of lung DTCs were sourced from PACC-injected mice. This difference may represent biologically interesting differences in tissue-specific extravasation barriers. For example, potential size or biophysical rigidity restrictions in the bone marrow may select for cells in the PACC state on the smaller end of what is known to be a heterogeneous spectrum: the number of endocycles is inherently linked to the size of a PACC’s nucleus and cell body. Notably, baseline PACCs found in parental populations are frequently smaller than PACCs found in chemotherapy-induced populations. Therefore, it is possible that bone-specific environmental pressure selects for extravasation of small PACCs, which are disproportionately found in parental populations, although further study is necessary.

The presence of CTCs and DTCs alone is not sufficient to claim complete metastatic competency; evidence of functional colonization is also needed. Multiple in vitro studies have reported on the latent depolyploidization (also called ploidy reversal or ploidy reduction) of cells in the PACC state. Following long periods of survival marked by the absence of cell division, PACCs reengage a mitotic cell cycle and produce progeny (32–35). PACC progeny seems to be of typical cancer cell size and genomic content and engages a typical mitotic cell cycle. We used two models to specifically test the colonization potential of PACCs in vivo. In both settings, the PACC state life cycle closely followed what has been observed in vitro. By 12 weeks following subcutaneous injection of size-filtered PACCs (to remove any infiltrating mitotic non-PACC cells), 7/12 mice showed survival of nonproliferative PACCs at the injection site and 2/12 mice showed delayed tumor establishment followed by slow proliferation, indicative of latent in vivo repopulation. By 19 weeks following intracardiac injection of PACCs, 4/7 mice had established metastatic lesions detectable via BLI.

Notably, direct-to-blood metastasis models do not accurately reflect the selective pressures experienced throughout the entire metastatic cascade. Indeed, the results from our spontaneous metastasis models show that most CTCs and DTCs are PACCs, indicating a bottleneck for non-PACCs during the early stages of the metastatic cascade. Ergo, in our in vitro colonization models, injecting equal numbers of PACCs and positive control parental populations does not accurately reflect true metastatic conditions. As such, comparative conclusions about the progression of metastasis between PACCs and positive control populations cannot be made. Rather, these colonization experiments only serve to provide empirical evidence that PACCs are indeed capable of secondary site colonization. The golden standard for testing the entire metastatic cascade, including colonization, within one in vivo model requires the creation of and subsequent removal of a subcutaneous tumor, followed by BLI-mediated monitoring of distant organs for eventual colonization. Our attempts at this model were made impossible by the aggressive nature of the PC3-GFP-Luc cell line. Peritoneally invasive tumors consistently recurred following surgical removal, and mice could not survive long enough to allow for distant metastatic outgrowth.

Taken together, our in vivo data provide strong evidence of a causative relationship between PACCs and metastasis in prostate cancer, substantially strengthening the experimental in vitro and retrospective clinical correlations previously observed in prostate breast and ovarian cancer settings. Next, we sought to establish a preliminary mechanism underlying this cell-intrinsic, prometastatic phenotype. In the past decade, there has been a notable shift away from a binary and mutually exclusive epithelial versus mesenchymal phenotype. Instead, researchers have begun to appreciate the existence—and importance—of hybrid pEMT phenotypes. In fact, many groups have reported that cells with pEMT expression profiles display increased metastatic competency (36, 37), perhaps owning to the needs of successfully metastatic cells to have both the motility programs that mesenchymal cells provide and the proliferative programs that epithelial cells provide. RNA and protein analysis of cells in the PACC state revealed a hybrid pEMT pattern, most strongly supported by the simultaneous expression of CDH1 and VIM. Though the literature lacks a precise definition of pEMT that is characterized by specific EMT marker expression levels, it is generally appreciated that simultaneous coexpression of any canonical epithelial and mesenchymal markers (such as CDH1 and VIM) qualifies a cell as pEMT (37). Notably, others have also reported pEMT phenotypes in PACCs created in other cancer cell lines, indicating this finding is not unique to prostate cancer (38). Analysis of bone marrow from patients with prostate cancer supported our in vitro findings: patient bone marrow contained PACCs coexpressing pan-epithelial markers and VIM at the protein level.

To test for a potentially indirect mechanistic link, we turned to the literature citing the similarities between the PACC state and therapy-induced senescence (39–42). Therapy-induced senescent cells arise in response to treatment and are characterized by a transient pause in cell cycle, among other features. Though therapy-induced senescent cells depart from classic terminally senescent cells in several ways, they have been reported to share the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Most notably, the SASP has been reported to contribute to a more prometastatic tumor microenvironment (43, 44). Accordingly, we thought it possible that PACCs might promote the metastatic phenotype of surrounding non-PACC tumor cells by contributing to a prometastatic tumor microenvironment. We found that PACCs produce a SASP-like secretory profile rich in MIP3-α, GCP-2, DPPIV, IL6, GM-CSF, G-CSF, ENA-78, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-2, and GRO, among many others. Furthermore, coculture with PACC-conditioned media increased the motility of non-PACC cells. A validation of the most differentially secreted cytokine, IL6, showed that it was sufficient to induce motility in a paracrine (PACC to non-PACC) but not autocrine (PACC to PACC) setting. We are not the first to find an IL6-rich PACC secretome (45), and of note, the motility-inducing nature of IL6 has been previously published in other contexts (46).

We acknowledge that the use of only prostate cancer-derived PACCs constitutes a limitation of this study. Given (i) published clinical reports associating PACCs with poor patient outcomes in rectal, colorectal, laryngeal, urinary, and ovarian cancers and buttressed by (ii) in vitro evidence of the enhanced motility, enhanced chemotaxis, unique pEMT phenotype, and abundant IL6 secretions observed in PACCs derived from breast and ovarian cell lines, we hypothesize that the experimental in vivo metastatic phenotypes observed in this study would phenocopy in other cancer cell lines. We also acknowledge that this study only uses an androgen receptor (AR)-negative prostate cancer cell line. Although a clinical study has confirmed the compatibility of PACC induction with AR-positive status (finding that 8/10 cases of prostatic pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma stained positive for AR via IHC; ref. 21), no published data have examined the metastatic potential of AR-positive PACCs.

The PACC state represents an emerging area of cancer research committed to understanding the adaptive phenotypic potential of cancer cells. It has been well established that treatment of cancer with chemotherapeutic agents inevitably leads to the increase in treatment-resistant disease. Though outside the scope of this article, it has been repeatedly shown that cells in the PACC state are broadly resistant to a wide swath of anticancer agents (8, 10, 13, 41, 45, 47, 48). In addition to chemotherapy-induced resistance, evidence has begun to suggest that cancers treated with chemotherapeutics are prone to become more metastatic. For example, emerging evidence show that chemotherapy induces cancer cell–intrinsic changes such as upregulation of antiapoptotic genes and increased migration (49). When tested in mice using spontaneously metastatic orthotopic breast models, it was found that paclitaxel increased metastasis despite decreasing primary tumor burden (49). Karagiannis and colleagues (50) demonstrated that this observation holds true in the patient setting: clinically validated prognostic markers of metastasis in patients with breast cancer were increased in patients who received neoadjuvant paclitaxel after doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide. Considering that nearly all anticancer agents tested have shown to induce the PACC state, our data position the increased metastatic competency of cells in the PACC state as an important unforeseen ramification of neoadjuvant regimens, which may help explain clinical correlations between chemotherapy and metastatic progression.

Supplementary Material

Subcutaneous injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population and PACC-enriched population: A) Raw cytometric data reporting GFP+ signal across all samples, to demonstrate GFP+ intensity of dissociated subcutaneous tumors. B) Quantification of PACC proportion among GFP+ dissociated tumor cells, determined by DNA ploidy analysis.

Relevant details of in vivo metastasis models

Time-matched, subcutaneous injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population vs. PACC-enriched population: A) Raw cytometric data reporting GFP+ signal across all blood samples. B) Raw cytometric data reporting DNA content of GFP+ cells across all blood samples.

Numbers of cells analyzed by flow cytometry per mouse

Time-matched, subcutaneous injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population vs. PACC-enriched population: A) Raw cytometric data reporting GFP+ signal across all bone marrow samples. B) Raw cytometric data reporting DNA content of GFP+ cells across all bone marrow samples.

Western blot antibodies used

Size-matched, subcutaneous injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population vs. PACC-enriched population: A) Raw cytometric data reporting GFP+ signal across all blood samples. B) Raw cytometric data reporting DNA content of GFP+ cells across all blood samples.

RTqPCR primers used

Size-matched, subcutaneous injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population vs. PACC-enriched population: A) Raw cytometric data reporting GFP+ signal across all bone marrow samples. B) Raw cytometric data reporting DNA content of GFP+ cells across all bone marrow samples.

Caudal Artery injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population vs. PACC-enriched population: A) Raw cytometric data reporting GFP+ signal across all bone marrow samples. B) Raw cytometric data reporting DNA content of GFP+ cells across all bone marrow samples.

Caudal Artery injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population vs. PACC-enriched population: A) Raw cytometric data reporting GFP+ signal across all lung tissue samples. B) Raw cytometric data reporting DNA content of GFP+ cells across all lung tissue samples.

Tail Vein injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population vs. PACC-depleted parental population: A) Flow-cytometric ploidy analysis of injected cells per injection group. B) Proportion of lung DTCs with >4N DNA content across all experimental mice. C) Comparative proportions of lung DTCs with >4N DNA content between two injection groups.

Tail Vein injection of PC3-GFP-Luc parental population vs. PACC-enriched population: A) Light microscopy photos and flow-cytometric ploidy analysis of injected cells per injection group. B) Representative BLI images capturing the cellular distribution and signal intensity immediately following tail vein injection and 3 days following tail vein injection. C) Raw cytometric data reporting the presence of >4N Lung DTCs in a pooled sample 21 days following PACC injection.

Uncropped images of western blots for EMT-markers: A) Uncropped blot from which E-Cadherin, Vimentin, Snail, and Claudin-1 signals featured in Figure 6B are taken. B) Uncropped blot from which N-Cadherin and Slug signals featured in Figure 6B are taken. C) Uncropped blot from which EpCAM and Twist signals featured in Figure 6B are taken.

PACCs have a pro-metastatic secretory profile: A) Wound-healing assay comparing the differential motility of a PC3-Luc population exposed to parental-conditioned media vs. PACC-conditioned media, where each reported biological replicate is an average of two technical replicates. B) RNA expression of a panel of EMT markers by RTqPCR in a PC3-Luc parental population exposed to parental-conditioned media vs. PACC-conditioned media, were each biological replicate reported is an average of three technical replicates. C) Single cell tracking comparing the motility of a PACCs treated or untreated with Tocilizumab.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ana Aparicio and Paul Corn for their critical contributions. The authors would also like to thank the patients and their caregivers who consented to this study, as well as the clinical research staff who contributed. The authors also thank the staff of the Johns Hopkins Oncology Tissue Core and the Johns Hopkins Molecular Imaging Service Center and Cancer Functional Imaging Core for their respective contributions, as well as members of the Cancer Ecology Center for their thoughtful conversation and invaluable feedback. P. Kuhn and J. Hicks were supported by the NCI’s Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center (CORE) Support 5P30CA014089-40. K.J. Pienta was supported by the NCI grants U54CA143803, CA163124, CA093900, and CA143055 and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. S.R. Amend was supported by the US Department of Defense Congressionally-Directed Medical Research Program Prostate Cancer Research Program (CDMRP/PCRP W81XWH-20-10353 and W81XWH-22-1-0680), the Patrick C. Walsh Prostate Cancer Research Fund, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Molecular Cancer Research Online (http://mcr.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors’ Disclosures

A.J. Zurita reports grants from Pfizer Astellas, and ABX and other support from Merck, Clarity, Curium, and Fusion outside the submitted work. J. Hicks reports partial support from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (nonprofit). K.J. Pienta reports grants from NIH NCI and the Prostate Cancer Foundation, support from Keystone Biopharma, Inc. during the conduct of the study, as well as other support from Kreftect, Inc. outside the submitted work. S.R. Amend reports grants from the Department of Defense, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation during the conduct of the study, as well as other support from Keystone Biopharma outside the submitted work. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Authors’ Contributions

M.M. Mallin: Conceptualization, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft. L.T.A. Rolle: Investigation, writing–review and editing. M.J. Schmidt: Formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing–review and editing. S. Priyadarsini Nair: Investigation. A.J. Zurita: Writing–review and editing. P. Kuhn: Funding acquisition, writing–review and editing. J. Hicks: Supervision, funding acquisition. K.J. Pienta: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing–review and editing. S.R. Amend: Funding acquisition, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 2003;3:453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Devasia TP, Mariotto AB, Nyame YA, Etzioni R. Estimating the number of men living with metastatic prostate cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2023;32:659–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pienta KJ, Hammarlund EU, Brown JS, Amend SR, Axelrod RM. Cancer recurrence and lethality are enabled by enhanced survival and reversible cell cycle arrest of polyaneuploid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118:e2020838118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu J, Niu N, Li X, Zhang X, Sood AK. The life cycle of polyploid giant cancer cells and dormancy in cancer: opportunities for novel therapeutic interventions. Semin Cancer Biol 2022;81:132–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou X, Zhou M, Zheng M, Tian S, Yang X, Ning Y, et al. Polyploid giant cancer cells and cancer progression. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022;10:1017588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen J, Niu N, Zhang J, Qi L, Shen W, Donkena KV, et al. Polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs): the evil roots of cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2019;19:360–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. White-Gilbertson S, Voelkel-Johnson C. Giants and monsters: unexpected characters in the story of cancer recurrence. Adv Cancer Res 2020;148:201–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Amend SR, Torga G, Lin KC, Kostecka LG, de Marzo A, Austin RH, et al. Polyploid giant cancer cells: unrecognized actuators of tumorigenesis, metastasis, and resistance. Prostate 2019;79:1489–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tagal V, Roth MG. Loss of aurora kinase signaling allows lung cancer cells to adopt endoreplication and form polyploid giant cancer cells that resist antimitotic drugs. Cancer Res 2021;81:400–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Niu N, Zhang J, Zhang N, Mercado-Uribe I, Tao F, Han Z, et al. Linking genomic reorganization to tumor initiation via the giant cell cycle. Oncogenesis 2016;5:e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim CJ, Gonye AL, Truskowski K, Lee CF, Cho YK, Austin RH, et al. Nuclear morphology predicts cell survival to cisplatin chemotherapy. Neoplasia 2023;42:100906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shu Z, Row S, Deng WM. Endoreplication: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Trends Cell Biol 2018;28:465–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Niu N, Mercado-Uribe I, Liu J. Dedifferentiation into blastomere-like cancer stem cells via formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene 2017;36:4887–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fei F, Zhang D, Yang Z, Wang S, Wang X, Wu Z, et al. The number of polyploid giant cancer cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related proteins are associated with invasion and metastasis in human breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015;34:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang D, Yang X, Yang Z, Fei F, Li S, Qu J, et al. Daughter cells and erythroid cells budding from PGCCs and their clinicopathological significances in colorectal cancer. J Cancer 2017;8:469–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xuan B, Ghosh D, Cheney EM, Clifton EM, Dawson MR. Dysregulation in actin cytoskeletal organization drives increased stiffness and migratory persistence in polyploidal giant cancer cells. Sci Rep 2018;8:11935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xuan B, Ghosh D, Jiang J, Shao R, Dawson MR. Vimentin filaments drive migratory persistence in polyploidal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:26756–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mallin MM, Kim N, Choudhury MI, Lee SJ, An SS, Sun SX, et al. Cells in the polyaneuploid cancer cell (PACC) state have increased metastatic potential. Clin Exp Metastasis 2023;40:321–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lv H, Shi Y, Zhang L, Zhang D, Liu G, Yang Z, et al. Polyploid giant cancer cells with budding and the expression of cyclin E, S-phase kinase-associated protein 2, stathmin associated with the grading and metastasis in serous ovarian tumor. BMC Cancer 2014;14:576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bilé-Silva A, Lopez-Beltran A, Rasteiro H, Vau N, Blanca A, Gomez E, et al. Pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma of the prostate: clinicopathologic analysis and oncological outcomes. Virchows Arch 2023;482:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alharbi AM, De Marzo AM, Hicks JL, Lotan TL, Epstein JI. Prostatic adenocarcinoma with focal pleomorphic giant cell features: a series of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2018;42:1286–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mannan R, Wang X, Bawa PS, Spratt DE, Wilson A, Jentzen J, et al. Polypoidal giant cancer cells in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: observations from the Michigan Legacy Tissue Program. Med Oncol 2020;37:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]