Significance

The deep sea is the most extensive region on Earth, covering 90% of the ocean floor. Modern deep-sea ecosystems have been barely explored, and their evolutionary origin is poorly understood. Since most body fossils occur in rocks formed in shallow water, reconstructing the evolution of deep-sea biotas has been challenging. We overcome these difficulties by examining the burrows, trails, and trackways left by organisms in the sea floor and preserved in rocks formed between 635 and 359 Mya. We show that the modern-style deep-marine benthos was established during the Ordovician after a protracted evolution that spanned 100 My. Fluctuations in diversity may have been controlled by oceanic circulation linked to climate.

Keywords: bioturbation, evolutionary paleoecology, evolutionary radiations, mass extinctions, climate

Abstract

Our understanding of the patterns and processes behind the evolution of deep-marine ecosystems is limited because the body-fossil record of the deep sea is poor. However, that gap in knowledge may be filled as deposits are host to diverse and abundant trace fossils that record the activities of benthic deep-marine organisms. Here, we built a global dataset of trace-fossil occurrences from a comprehensive survey of 720 Ediacaran–Devonian units and show that the establishment of a modern-style deep-marine benthic ecosystem was protracted and coincident with global cooling and increase in oxygenation during the Ordovician. The formation of open burrows may have increased bioirrigation in the uppermost sediment zone, promoting ventilation and generating an ecosystem engineering feedback loop between bioturbation and pore-water oxygenation. Sharp changes in deep-marine bioturbation during the Devonian may have originated from oxygen variations resulting from climate-controlled oceanic circulation.

The body-fossil record is biased toward shallow-marine platforms. However, the deep sea (i.e., from slope break to basin plain) is the most extensive region on Earth, covering approximately 90% of the ocean floor (1). The origin of modern deep-sea ecosystems and its diversity remain topics of debate (2), with one major hypothesis stating that modern high diversity resulted from relatively rapid evolution (3) and a second (i.e., “steady-state” hypothesis) viewing it as emerging from stable conditions over a long period of time (4). Assessing this topic has been hampered by the poor body-fossil record of the deep sea and the logistic difficulty of sampling in the modern deep ocean (5). Notably, deep-marine deposits are host to diverse and abundant trace fossils resulting from animal–substrate interactions, providing a valuable proxy for the past ecology of the deep sea (6–13). Bioturbation refers to all kinds of particle displacement and physicochemical sediment modifications by organisms, whereas trace fossils are distinctive structures of biogenic origin (e.g., trackways, burrows, trails), somehow related to the morphology of the producer, which can be seen as the products of such process [(14) and references therein]. This rich record opens a window to local, regional, and global scales of analyses. In fact, in most Paleozoic successions, trace fossils represent the only evidence of the deep-sea benthos (6–8). The deep-sea community is epitomized by some of the most complex trace fossils (i.e., graphoglyptids), which are inferred to record feeding strategies such as bacterial farming and microorganism trapping (11, 15, 16) in well-oxygenated settings (17, 18). Bioturbation has been considered a potential driver of diversification, and its role as a major player in geobiologic feedbacks and geochemical cycles during early evolutionary radiations has been stressed for shallow-marine ecosystems (19–22). However, its importance in the early deep sea has received less attention.

The objectives of this paper are to 1) reconstruct the trajectory leading to the establishment of modern-style deep-marine ecosystems based on a comprehensive trace-fossil database for deep-marine settings and 2) discuss potential links between bioturbation in benthic ecosystems and deep-ocean oxygenation. Ichnodiversity, ichnodisparity, maximum alpha ichnodiversity, beta ichnodiversity, ecospace utilization, and ecosystem engineering were the main proxies used to assess the early colonization of the deep sea. Ichnodisparity and the different metrics for ichnodiversity reflect aspects of the trace fossil themselves, whereas metrics of ecospace utilization and ecosystem engineering show a much closer relationship with bioturbation and the effects on the ecosystem and environment.

Results

There are a greater number of stratigraphic units and trace-fossil occurrences from siliciclastic compared to carbonate deep-marine environments. The majority of units span more than one stage and several span more than one series (SI Appendix, Tables S4 and S5), and so the temporal precision of our dataset is limited to the series. Colonization of deep-marine siliciclastic environments was extremely limited during the Ediacaran–Terreneuvian (635-521 Ma), and no substantial increases in the analyzed metrics (i.e., global ichnodiversity, ichnodisparity, modes of life, ecosystem engineering, and maximum alpha ichnodiversity) are detected (Figs. 1A and 2). Tests show that there is no statistically significant correlation between observed ichnodiversity and the number of stratigraphic units for deep-marine siliciclastic environments from Cambrian Series 2 to the Upper Devonian (SI Appendix, Table S3). As such, we omit the Ediacaran and Terreneuvian from substantial analysis and discussions of these results, although we include them in the diagrams for completeness. Similarly, the colonization and number of stratigraphic units hosting trace fossils in carbonate deep-marine environments prior to the Middle Ordovician is so low that it prevents any meaningful inferences from those series (Figs. 1B and 2). There is no statistically significant correlation between observed ichnodiversity and the number of stratigraphic units for deep-marine carbonate environments from the Middle Ordovician to Upper Devonian (SI Appendix, Table S3). As such, we omit the Ediacaran to Lower Ordovician from substantial analysis and discussions of these results, although we include them in the diagrams for completeness.

Fig. 1.

Changes in ichnologic metrics in Ediacaran–Devonian deep-marine environments. (A) Siliciclastics. (B) Carbonates. GI, global ichnodiversity; ID, ichnodisparity; ML, modes of life; EE, ecosystem engineering; MAI, maximum alpha ichnodiversity. Data are plotted at the end of each series as they are cumulative across a series.

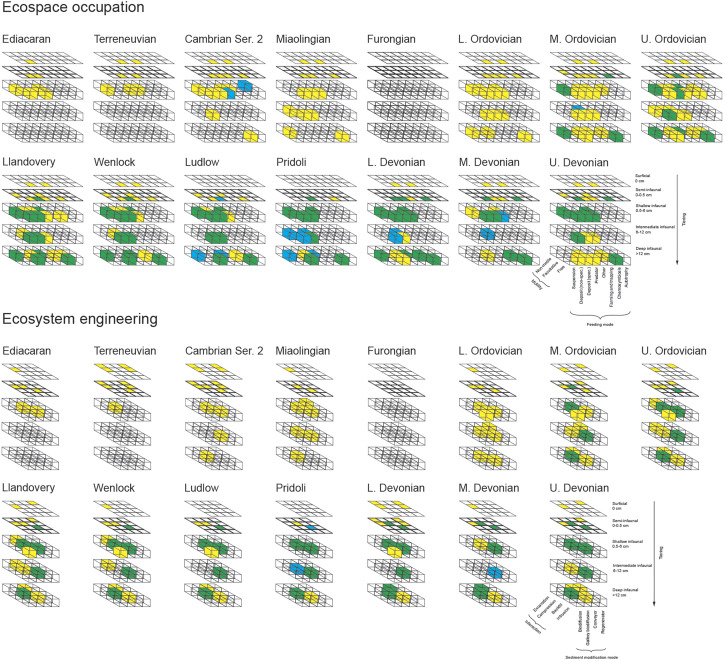

Fig. 2.

Changes in ecospace occupation and ecosystem engineering in Ediacaran–Devonian deep-marine environments. Bioerosion structures are not included in this diagram. Yellow, present in siliciclastic environments; blue, present in carbonate environments; green, present in both siliciclastic and carbonate environments.

All metrics are moderately high for siliciclastic deep-marine ichnofaunas in Cambrian Series 2 (521-509 Ma), followed by a rapid and dramatic decline during the rest of the Cambrian (509-485 Ma) (Fig. 1A). No trace fossils were detected in any of the twenty-three late Cambrian deep-marine units compiled (SI Appendix, Table S1 and Supporting Text), likely illustrating the Furongian gap (23, 24). A continuous increase in all metrics, particularly global ichnodiversity, to maximal levels is shown in siliciclastics up until the end Ordovician (485-443 Ma) and carries on for carbonates up until the Early Devonian (Fig. 1 A and B). A subtle decrease in all ichnologic metrics is apparent in deep-sea siliciclastics in the Llandovery (443-433 Ma), followed by a persistent decline during the rest of the Silurian (433-419 Ma) (Fig. 1A). Notably, ichnologic metrics in deep-sea carbonates show either no change (i.e., maximum alpha ichnodiversity and ecosystem engineering) or an increase (i.e., global ichnodiversity, ichnodisparity, and modes of life) during that time (Fig. 1B). Metrics in these two settings show for the most part similar trends during the Devonian (419-358 Ma), essentially an overall increase during the Early Devonian (419-393 Ma) followed by a decrease during the Middle Devonian (393-382 Ma). By the Late Devonian (382-358 Ma), all metrics in carbonates (other than modes of life which display a slight increase) show a plateau, whereas all those in siliciclastics display an increase (Fig. 1 A and B). Anyway, global ichnodiversity levels in siliciclastics by the Late Devonian were approximately still half of those by the Late Ordovician. Overall, colonization of carbonate turbidites lagged that of siliciclastic turbidites. If both siliciclastic and carbonate data are plotted together, the resulting curves are like those of the former as the larger number of stratigraphic units with trace fossils in siliciclastics drove the results (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Beta ichnodiversity follows the same trends as the other metrics (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), showing that global, alpha, and beta ichnodiversity do not decouple across any of the extinction and diversification events through the Ediacaran to Devonian. Standardizing the ichnodiversity data against the number of stratigraphic units reveals the same overall pattern but the peak of diversity is earlier, during the Early Ordovician, there is a decrease corresponding with the end-Ordovician extinction, and the differences during the Devonian are less pronounced (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B).

Evaluation of the proportion of the different feeding types across the different assemblages in thin- to very thin-bedded sandstone turbidites (St) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) shows that matground feeding was dominant in the Ediacaran and Cambrian (averaging 49% and reaching up to 67%). The Ordovician was characterized by the dominance of deposit and detritus feeding (averaging 54%, 53%, and 56% and reaching up to 75%, 75%, and 72%, for the Lower, Middle, and Upper Ordovician, respectively), but with increased participation of farming and trapping (averaging 16%, 9%, and 18% and reaching up to 27%, 20%, and 50%, for the Lower, Middle, and Upper Ordovician, respectively). Although the Silurian continued to be dominated by deposit and detritus feeding (averaging 48% and reaching up to 80%), the participation of farming and trapping became increasingly more important (averaging 24% and reaching up to 50%). These trends persisted in the Devonian (deposit and detritus feeding averaging 49% and reaching up to 75%; farming and trapping averaging 22% and reaching up to 33%).

Plotting occurrences in paleogeographic maps (SI Appendix, Figs. S3–S17) shows that even the initial and sparse Ediacaran colonization of the deep sea was globally widespread. Displacement of Laurentia toward low latitudes during the Terreneuvian and Cambrian Series 2 was accompanied by further expansion of the deep-sea benthos in this region. A dramatic contraction of deep-water communities was apparent during the Miaolingian and Furongian. This contraction trend was reverted during the Early Ordovician with colonization taking place along the continental slope and the base of the slope of all major continents (i.e., Gondwana, Laurentia, Baltica, and Avalonia). Diversification proceeded then in every ocean. An expansion into low- and high-latitude areas of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean facing Gondwana was apparent during the Middle to Late Ordovician, including regions close to glaciated margins. These trends continued during the Silurian, albeit with an increase in the areas colonized in Laurentia and Baltica during the Llandovery and Wenlock, and of the slopes of Gondwana facing the Paleo-Tethys during the Pridoli. The deep-sea regions of the Paleo-Tethys oceans facing Siberia evidence of colonization being achieved by the Early Devonian. A trend toward further colonization in low to mid-latitudes was apparent during the Middle to Late Devonian.

Analysis of the Principal Coordinates (PCoA) space represented by the trace-fossil assemblages shows changes in the locations and expansions and contractions through time (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). There is partial overlap in the distributions of trace-fossil assemblages from thin- to very thin-bedded sandstone turbidites (St) and thin- to very thin-bedded mudstone turbidites (Mt) throughout the studied time interval. The volume of PCoA space represented by trace-fossil assemblages from Mt initially expands from the Early to Middle Ordovician but subsequently remains similar or contracts through the Silurian before expanding again in the Early Devonian before contracting in the Middle Devonian and expanding in the Late Devonian. The PCoA space represented by trace-fossil assemblages from St expands through the Ordovician to Llandovery; following this though, they show the same pattern as that of Mt, with gradual contraction through the rest of the Silurian before expanding, contracting, and expanding again through the Devonian.

Discussion

This analysis allows a test of the competing hypotheses on the pace of the colonization of the deep sea. The trace-fossil record shows that the establishment of the deep-sea benthic ecosystem was a protracted process that took place relatively early in the history of the biosphere, in which the Ordovician radiation played a pivotal role (8–10, 25, 26) (Fig. 3). Analysis of our dataset also supports the idea of a gradual build-up of alpha ichnodiversity since the Cambrian (6) but, in contrast with this early view, this increase is only apparent since the second half of the early Cambrian and with a dramatic drop by the late Cambrian. Our analysis also confirms initial ideas, which were based on a very limited amount of data, that there were high levels of global ichnodiversity in the Ordovician (7). Ediacaran deep-marine trace fossils consist of very simple trails and burrows (27). Global and alpha ichnodiversity, as well as ichnodisparity, were extremely low (SI Appendix, Fig. S19). Unspecialized grazing trails reveal exploitation of microbial mats. These strategies persisted in the Cambrian, although with an increase in ichnodiversity (both global and alpha) and ichnodisparity later in the early Cambrian (SI Appendix, Fig. S19). An increase in the complexity of morphologic patterns, as illustrated by the undermat mining ichnogenus Oldhamia, is apparent during the Cambrian (8, 28). Arthropod trackways are also common in Cambrian turbidites (8, 28). Therefore, ichnologic evidence reveals the dual nature of the deep-marine Cambrian, which on one hand is characterized by the persistence of Ediacaran-style relict ecosystems (i.e., matground-dominated ecology) and on the other by the appearance of trace fossils that reveal the presence of key players of the Cambrian explosion (29). Graphoglyptids, which characterized younger deep-sea ichnofaunas, were present in shallow water during the Cambrian, further supporting the hypothesis that evolutionary innovations occurred first in proximal areas of the depositional profile and later expanded or retreated into deep water (21, 30, 31).

Fig. 3.

Ediacaran–Devonian colonization of the deep sea, summarizing evolutionary trends in ichnodiversity, ichnodisparity, feeding strategies, benthic paleoecology, and paleoclimates. Drawing by Kaitlin Lindblad.

The face of the deep sea started to change in a more definitive fashion by the beginning of the Ordovician with the protracted expansion of farming and trapping strategies. The main architectural designs of deep-marine trace fossils (graphoglyptids) were established by the Early Ordovician (SI Appendix, Fig. S19), recording the first appearance of the Nereites Ichnofacies (8, 32, 33) in mudstone turbidites. Other than biramous meandering graphoglyptids, whose oldest representatives are from the Llandovery, the other five categories of graphoglyptid architectural designs have been present since the Ordovician (SI Appendix, Fig. S19). The fact that these categories experienced a remarkable post-Paleozoic diversification (9, 10) supports a disparity-first pattern (34). Lower to Middle Ordovician deep-marine ichnofaunas were moderately diverse. They were dominated by feeding traces of deposit and detritus feeders instead of graphoglyptids reflecting trapping and farming. A significant and continuous ichnodiversity and ichnodisparity increase occurred all through the Ordovician, with ichnofaunas recording higher proportions of graphoglyptids and evidencing the establishment of a deep-marine ecosystem of modern aspect (8–10, 25, 26). This ichnodiversity increase and the overall participation of graphoglyptids parallel an increase in ocean ventilation and global cooling and a major perturbation in the global carbon cycle (21, 35, 36). Recent studies have calculated bottom water oxygen content in the different oceans according to different conditions of pCO2 (37). Ichnologic data serve to constrain oxygen models and are partially consistent with those based on estimations of intermediate values of pCO2. However, to support the presence of an infauna, oxygen content should have been higher in the Paleo-Tethys Ocean around Gondwana than envisaged in the available models (SI Appendix, Fig. S10).

The increase in abundance and diversity of graphoglyptids resulted in a more predominant role of gallery biodiffusers. This faunal turnover was coincident with an increase in oxygenation in slope and base-of-slope settings, which is thought to have been a driver of Ordovician biodiversification (21, 35, 36). Modern Paleodictyon showing a shield-like mound morphology helps to deflect bottom flows into the sediment (38, 39). Therefore, the formation of permanent open burrows may have increased bioirrigation in the uppermost zone of the deep-sea sediment, thereby increasing ventilation and potentially generating a feedback loop between bioturbation and pore-water oxygenation, with the endobenthos engineering its environment.

The distinction between the Nereites and Paleodictyon ichnosubfacies, with the former characterized by the dominance of feeding traces in muddy turbidites and the latter by the dominance of graphoglyptids in sandy turbidites (6, 40), can also be tracked back to the Ordovician radiation (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). As revealed by analysis of the PCoA space occupied by trace-fossil assemblages from these two types of deposits, the partial overlap among them confirms them as ichnosubfacies. The overall expansion of assemblages from St through the Ordovician to Llandovery corresponds with the rise and expansion of the Paleodictyon ichnosubfacies, while those from Mt generally stay similar or contract through this time interval.

In contrast to shallow water, the impact of the end-Ordovician mass extinction in the deep sea was minimal at a global scale (SI Appendix, Fig. S20A). In shallow-marine environments, two phases have been identified, the first linked to the glaciation and the second resulting from the expansion of anoxic waters on the shelves during postglacial times (41). As diversification of deep-sea ichnofaunas paralleled global cooling, glaciation may have even been beneficial for this benthos. In turn, anoxia on the shelves may have coexisted with oxygenated waters at the base of the slope, therefore failing to impact the deep-sea biotas significantly.

The disparate trajectories of ichnologic metrics in carbonates and siliciclastics during the Silurian and, to a lesser extent the Devonian, are hard to interpret, with metrics in carbonate settings increasing during this time, while those in siliciclastic settings decreased. These discrepancies may be due in part to the different preservational styles and constraints in carbonates with respect to siliciclastics, such as role of early cementation, influence of bioturbators on early diagenesis, role of color contrast, and heterogeneity in sediment texture and composition (14). In contrast to the semirelief preservation that is typical of trace fossils in siliciclastic turbidites, diagenetic processes may favor preservation of full-relief burrows in some cases (42). When these carbonates and siliciclastics are plotted together, there is a trend of constant and marked decrease in metrics starting in the Wenlock and reaching a significant minimum by the end of the Silurian. Notably, the decreasing trend persists if global ichnodiversity is standardized by the total number of stratigraphic units analyzed (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). In turn, the Devonian displays rapid changes in all metrics (SI Appendix, Fig. S20B). These rapid fluctuations do not support the view of the deep sea as a stable setting. Deep-sea trace-fossil assemblages reflect for the most part the activity of climax communities comprising populations that are characterized by K-selection and that flourished under stable conditions, diversifying through keen competition. Graphoglyptids are known to have relatively little tolerance to oxygen depletion (17). These characteristics may have made them particularly vulnerable to environmental fluctuations.

Information from modern environments indicates that the deep-sea benthos and biogeochemical cycling of elements are strongly affected by hypoxia (43, 44). Oxygen minimum zones extend from the outer shelf to the slope, reaching as deep as 1,500 m (45). Hypoxia may occur less commonly in deeper water (46, 47). These zones can shrink and expand, being controlled by ocean circulation, temperature, and productivity (45, 47). Their impact on the benthos is complex as hypoxia negatively affects the least oxygen-tolerant taxa but may promote speciation at a regional scale by enhancing gradients in selective pressures and establishing barriers to gene flow (44).

Glacial periods may have promoted more intense circulation of deep, oxygenated water, whereas warmer times were characterized by more sluggish circulation and less oxygenated sea bottoms (48, 49). In addition, cooling increases oxygen solubility in water, making more oxygen available for respiration. Because graphoglyptids are negatively affected by deoxygenation (17), changes in ichnodiversity in deep-marine environments were likely influenced by changes in overall temperature. For example, a late middle to late Eocene diversity increase in graphoglyptids in high latitudes of the southern hemisphere has been linked to water cooling and oligotrophy (50). The increase in graphoglyptid diversity through the Ordovician took place in a similar scenario. Similarly, the Late Devonian increase in all ichnologic metrics is coincident with global cooling and the onset of a glacial event (51).

The Devonian has been regarded as a time of profound instability, punctuated by short periods of crises, some of them characterized by widespread anoxia during warming times, including the Middle Devonian Kačák Event (51, 52). This event is coincident with a drop in ichnologic metrics in the deep sea. Although the impact of anoxia at that time has been essentially explored in shallow water and its effects on the deep sea are less known (52), occurrence of black shale not only in neritic settings but also in pelagic environments, points to widespread anoxia at that time (53). The Silurian-Devonian expansion of vascular plants resulting in the greening of the land (54) was probably conducive to a dramatic rise in the delivery of phytodetrital material to marine basins. Because decomposition of sinking organic matter depletes water of dissolved oxygen (45, 47), this increased delivery may have enhanced the likelihood of eutrophication and hypoxia, negatively impacting on graphoglyptid diversity during the middle Paleozoic. As with the end-Ordovician event, no decrease in ichnodiversity has been detected in connection with the Late Devonian mass extinction (SI Appendix, Fig. S20B). Although the Devonian trend of increase, decrease, and increase in ichnologic metrics is shown in all plots, greater temporal precision for the stratigraphic units is required to investigate the links between environmental change and the deep-sea trace-fossil record more fully.

Methods

Dataset Compilation.

We constructed a global dataset of trace-fossil occurrences from a survey of 720 Ediacaran–Devonian stratigraphic units representing slope and basin environments (SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2 and Supporting Text). Of these units, 147 contain trace fossils. Five hundred and sixteen units correspond to siliciclastic deep-marine settings and 209 to carbonate deep-marine settings. Five units contain both carbonate and siliciclastic deposits. Trace fossils have been recorded from 120 and 27 siliciclastic and carbonate deep-marine settings, respectively. The dataset is used to compute time series of ichnodiversity, ichnodisparity, ecospace utilization, and ecosystem engineering (including dominant ethologies). We used GPlates (https://www.gplates.org; SI Appendix, Figs. S3–S17) to generate a series of time slices and plot trace-fossil occurrences on paleogeographic maps using PALEOMAPS (55) to evaluate paleoclimatic controls and help to reveal any paleolatitudinal patterns.

The compilation was based on a systematic literature review, including stratigraphic units formed in deep-marine environments with or without records of trace fossils. The absence of trace fossils in the latter may in some cases simply reflect lack of studies and not necessarily the absence of trace fossils. Pertinent literature in different languages on Ediacaran–Devonian deep-marine units was collated by using various search engines (e.g., Google Scholar) and by assessment of publication series on stratigraphy and regional geology (e.g., Geological Society “Geology of” series). A critical evaluation of the literature was undertaken to refine information about the age and paleoenvironment of the pertinent stratigraphic units.

A consistent ichnotaxonomic approach, based on the analysis of widely accepted ichnotaxobases for each group of trace fossils, was adopted (14, 56). Each ichnotaxonomic assignment in the original literature was checked accordingly. Synonymies were evaluated in each case, and ichnotaxonomic reviews were taken into consideration to update assignments in the original sources (57–59). Ichnotaxa listed in the literature, but not figured, were not considered unless access to the specimens had been obtained. The dataset was compiled at ichnospecies rank but analyzed at ichnogenus rank as ichnotaxonomy is more firmly established at the latter (60). Trace fossils in open nomenclature were not included in the analysis. A total of 89 ichnogenera are identified in the deep-marine Ediacaran–Devonian record.

Paleoenvironmental assessment for each of the stratigraphic units compiled was based either on the original papers documenting the trace-fossil content or on sedimentologic studies of the same unit. In case of discrepancies (e.g., units interpreted as shallow-marine by some authors, but as deep-marine by others), the available evidence was carefully weighed, and a deep-marine origin was discarded if the evidence was regarded as insufficient. In the case of units containing trace fossils, subdivisions were established between 1) slope hemipelagites and mass transport deposits, 2) very thick- to medium-bedded sandstone turbidites (Tst), 3) thin-to very thin-bedded sandstone turbidites (St), 4) thin-to very thin-bedded mudstone turbidites (Mt), and 5) basin plain hemipelagites. In the ichnofacies model, these five types of deposits broadly correspond to the Zoophycos ichnofacies (slope), the Ophiomorpha rudis ichnosubfacies (St forming channel fills or proximal lobe deposits), the Paleodictyon ichnosubfacies (St from frontal splays, levee, and crevasse splays of the submarine fan complex), the Nereites ichnosubfacies (Mt from distal overbank and the transition between the frontal splays and the basin plain), and an abyssal trace-fossil association (basin plain), which have been recurrently identified in the stratigraphic record (6, 14, 61–63). This paleoenvironmental framework allows us to track the origin and early evolution of these ichnofacies early in the Phanerozoic. The proportion of the different feeding types was plotted for St, which are characteristic of terminal and crevasse splays (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). These are the most suitable subenvironments to assess evolutionary breakthroughs in the deep-sea benthos as they contain the richest trace-fossil record of the whole deep sea (6, 9–11, 40).

Ages of the units plotted have been obtained either from the original study documenting the trace-fossil content or from biostratigraphic and geochronologic studies performed in the same unit. Official subdivisions of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart have been adopted. In the cases in which the age in the primary source was stated in local subdivisions, conversions to the official chart were performed. Some units were poorly constrained, often covering more than one stage and potentially spanning several series. In such cases, occurrences of ichnotaxa were ascribed to each of the spanning series for a unit.

Ichnologic Metrics.

We have used the currently accepted definitions of ichnodiversity and ichnodisparity (60). Global ichnodiversity refers to the total number of ichnogenera in the deep sea at a certain time, whereas alpha ichnodiversity corresponds to the number of ichnogenera in each trace-fossil assemblage. Beta ichnodiversity is calculated as the global ichnodiversity divided by the average alpha ichnodiversity. Architectural designs reflect the basic morphologic plans involved in animal–substrate interactions. Each ichnogenus is included in one category of architectural design in agreement with previous proposals (SI Appendix, Table S1).

The analysis of multidimensional ecospace and ecosystem engineering put forward in previous studies (64, 65) has been used. To assess ecospace utilization, we have adopted a previous scheme based on body fossils (66) but adjusted this to reflect the specificities of trace fossils (21, 64, 65). Tiering, motility, and feeding mode are used to quantify the number of modes of life, as a proxy to occupied ecospace (66). Each ichnogenus was categorized based on these three parameters (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Tiering (i.e., position occupied by an animal vertically with respect to the sediment surface) is subdivided into five categories: surficial, semi-infaunal, shallow infaunal, intermediate infaunal, and deep infaunal, in agreement with previous proposals (19, 21, 64–66). The surficial tier corresponds to animals living on the sediment surface. The semi-infaunal tier refers to animals that are partly infaunal and exposed to the overlying water. The shallow infaunal tier corresponds to animals living as deep as 6 cm within the sediment. The intermediate infaunal tier refers to those animals inhabiting depths between 6 and 12 cm within the sediment. The deep infaunal tier includes those animals living at depths between 12 and 100 cm. A very deep infaunal tier corresponds to animals occupying depths greater than 1 m.

Motility is classified into motile, facultatively motile, and nonmotile (21, 64–66). Any animal producing temporary structures that reflect continuous or semicontinuous movement, such as trails and trackways, but also some burrows, is considered motile. Organisms that are generally stationary, for example, those living in dwelling burrows, but are capable of movement are regarded as facultatively motile.

The most common feeding modes reflected in the trace-fossil record are suspension feeding, deposit feeding (both unspecialized and specialized), and predation; and these have been expanded upon from previous frameworks (64, 65) to incorporate chemosymbiosis, farming and trapping, and matground feeding. Less common feeding modes include autotrophy and parasitism. Assigning ichnotaxa to feeding modes requires variable degrees of interpretation. Suspension feeding is displayed by those animals that gather food particles from the water column, being typically recorded by permanent vertical burrows or borings. Deposit feeding corresponds to those animals that actively ingest food particles from the sediment. These include both deposit feeding sensu stricto (i.e., processing particles within the sediment) and detritus feeding (i.e., processing particles from the sediment surface, also referred to as surface deposit feeding). These feeding modes are commonly recorded by trails and burrows of variable morphology (e.g., spreite burrows, branching burrows, concentrically filled burrows). Unspecialized deposit feeding typically corresponds to animals leaving simple and self-overcrossing trails and specialized deposit feeding to those leaving nonovercrossing and meandering trails). Predation involves those animals able to capture prey, which in the trace-fossil record tend to be represented by bioerosion structures (e.g., durophagy, drilling), open burrows, and diffuse bioturbation structures. Chemosymbiosis corresponds to animal endosymbiosis with chemo-autotrophic bacteria and has been inferred for burrows with shafts or bunches with downward radiating probes. A few ichnotaxa have been interpreted as reflecting this feeding mode, most notably Chondrites, whose branching pattern may be regarded as “sulfide wells” and the shallow-marine Solemyatuba ypsilon, whose U-shaped morphology may have allowed burrow ventilation, and its downward blind extension may have been used for pumping hydrogen sulfide from the sediment (as in the bivalve Solemya) (67). Farming refers to the culturing of suitable bacteria or fungi for feeding purposes, an activity that occurs on large internal surfaces of burrows or chambers. Trapping corresponds to the passive capture of migrating meiofauna or other microorganisms. These two feeding modes are in practice difficult to differentiate based on the analysis of trace fossils. In general, farming and trapping are recorded by a group collectively known as graphoglyptids, which comprise regular, patterned, meandering, spiral, radiating, and network structures (15). Farming and trapping are the classic feeding modes inferred for deep-marine trace fossils. All feeding modes associated with matground exploitation are included in matground feeding (68). This includes mat grazing (organisms browsing through the microbial mat), undermat mining (organisms constructing tunnels below the active mat), mat scratching (organisms rasping on the microbial mats), and mat digestion (organisms feeding from direct external digestion of the mat). Although these different matground feeding categories were counted separately for the analysis, they have been plotted as a single category in the diagrams. In the present analysis, matground feeding has been inferred for several Ediacaran and Cambrian trace-fossil occurrences. Autotrophy refers to organisms capable of synthesizing their own food from inorganic substances by means of light or chemical energy. This feeding mode is illustrated in the trace-fossil record by microborings produced by algae and cyanobacteria. In parasitism, one species benefits to the detriment of the other. No ichnotaxa attributed to parasitism have been identified in the present analysis.

Ecosystem engineering is assessed based on tiering, mode of sediment interaction, and mode of sediment modification, and the details of this approach have been discussed elsewhere (64, 65). Each ichnogenus was categorized based on these three parameters (SI Appendix, Table S1). Tiering categories have been characterized above. Classification in terms of mode of sediment interactions for bioturbation follows a previous scheme and comprises intrusion, compression, backfilling, and excavation (56). Intrusion consists of sediment displacement as the animal moves through, but the sediment closes behind it. Compression represents sediment movement and compaction around the animal as it passes through. Backfilling corresponds to active backward sediment movement around or through the animal. Excavation comprises active loosening and bulk transport of sediment from one spot to another. Modes of interaction for bioerosion are represented by mechanical penetration, chemical dissolution, or a combination of both mechanisms.

Modes of sediment modification are assessed based on the way animals impact on and rework sediment, using a framework that has been adapted from marine benthic ecology (56). The proposed scheme comprises biodiffusors, gallery biodiffusors, conveyors, and regenerators (64, 65). Biodiffusors are animals that move sediment particles over short distances, being analogous to molecular or eddy diffusion. Gallery biodiffusors are those animals that produce rapid redistribution of sediment particles from one spot of the sediment profile to another, typically constructing dwelling burrows, resulting in diffusive local biomixing of particles. Conveyors (including both upward and downward conveyors) are animals oriented vertically that actively transport sediment particles across and within tiers. In this category, particle movement is nonlocal, beyond that capable by just biodiffusion. Regenerators are those animals that construct actively maintained burrows, constantly moving sediment from below to the surface, where it may be transported away by currents.

Data Analysis.

Confidence in the observed patterns of ichnodiversity through time was tested by analyzing whether observed global ichnodiversity is correlated with different sampling proxies: i) the total number of stratigraphic units (combined total of ichnofossiliferous and nonichnofossiliferous stratigraphic units), ii) the number of ichnofossiliferous stratigraphic units, and iii) the number of trace-fossil assemblages. In addition, correlations between the different sampling proxies were investigated. It is anticipated that there will be correlations between global ichnodiversity and the number of ichnofossiliferous stratigraphic units and number of trace-fossil assemblages, as well as between the number of ichnofossiliferous stratigraphic units and number of trace fossil assemblages because they are not independent measures. The lack of independence between measures of diversity and counts of ichnofossiliferous stratigraphic units or assemblages has been demonstrated using simulations (69), whereas, instead, the number of stratigraphic units in which a particular fossil could be found is considered a better measure of sampling intensity. We followed Buatois et al. (21) and collated the total number of deep-marine stratigraphic units (combined total of ichnofossiliferous and nonichnofossiliferous stratigraphic units) as a proxy for sampling intensity of such settings through the Ediacaran to Devonian. Analyses were performed separately for data from siliciclastic and carbonate deep-marine depositional settings, as well as for their combined totals. Sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate trade-offs between the temporal range of the global ichnodiversity data with its reliability to reflect real patterns rather than sampling intensity (SI Appendix, Table S3). In addition, plots of global ichnodiversity standardized by the number of ichnofossiliferous stratigraphic units and total number of stratigraphic units for each time slice were compared against the patterns from the raw data (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The total number of stratigraphic units was considered as the best means of standardization as this is a proxy for available rock volume. Standardization by the duration of each series was discounted as this placed substantial emphasis on the comparatively short-duration Ludlow, Wenlock, and Pridoli series despite them having similar or greater numbers of stratigraphic units compared to earlier series with greater global ichnodiversity. As such, the lower values for global ichnodiversity during the Ludlow, Wenlock, and Pridoli are demonstrably not due to lower available rock volume for sampling. As the data include small numbers both of ichnogenera and of sampling proxies and are non-normally distributed, we used the Spearman rank-order correlation to test the null hypotheses that there are no correlations between and among global ichnodiversity and the different sampling proxies. The Spearman rank-order correlation was used because it is not sensitive to outliers and does not assume a normal distribution to the data. P-values for Spearman’s rho of > 0.05 will mean that it is not possible to reject the null hypothesis that measures are uncorrelated.

To visualize patterns in the multivariate space occupied by trace-fossil assemblages through time, a presence–absence matrix of occurrences of ichnogenera across trace-fossil assemblages from St and Mt was analyzed using PCoA. Euclidean distance was used as the similarity index. The PCoA was conducted for all trace-fossil assemblages and then the convex hulls represented by the assemblages from the two different facies were isolated and plotted for each series-level time slice (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). Trace fossils from the St facies are anticipated to correspond to the Paleodictyon ichnosubfacies and trace fossils from the Mt facies are anticipated to correspond to the Nereites ichnosubfacies. All statistical analyses were conducted using PAST 4.11 (70).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This manuscript has been improved by careful revisions by Andrew Rindsberg, an anonymous referee, and the Associate Editor. Kaitlin Lindblad is tanked for drawing Fig. 3. We thank funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grants 311727-20 and 422931-20 awarded to M.G.M. and L.A.B., respectively. Mángano recognizes additional funding from the George J. McLeod Enhancement Chair in Geology.

Author contributions

L.A.B. and M.G.M. designed research; L.A.B., M.G.M., M.P., and N.J.M. performed research; L.A.B., M.G.M., M.P., N.J.M., and K.Z. analyzed data; and L.A.B., M.G.M., and N.J.M. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Gage J. D., Tyler P. A., Deep-Sea. Biology. A Natural History of Organisms of the Deep-Sea Floor (Cambridge University Press, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClain C. R., Schlacher T. A., On some hypotheses of diversity of animal life at great depths on the sea floor. Mar. Ecol. 36, 849–872 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herring P., The Biology of the Deep Ocean (Oxford University Press, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders H. L., Marine benthic diversity: A comparative study. Am. Nat. 102, 243–282 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClain C. R., Rex M. A., Etter R. J., “Patterns in Deep-Sea Macroecology” in Marine Macroecology, Witman J. D., Roy K., Eds. (University of Chicago Press, 2009), pp. 65–99. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seilacher A., Flysch trace fossils: Evolution of behavioural diversity in the deep-sea. Neues Jb. Geol. Paläontol. Monat. 1974, 233–245 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crimes T. P., Colonisation of the early ocean floor. Nature 248, 328–330 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orr P. J., Colonization of the deep-marine environment during the early Phanerozoic: The ichnofaunal record. Geol. J. 36, 265–278 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchman A., Trends in diversity, frequency and complexity of graphoglyptid trace fossils: Evolutionary and palaeoenvironmental aspects. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 192, 123–142 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchman A., “Phanerozoic history of deep-sea trace fossils” in The Application of Ichnology to Palaeoenvironmental and Stratigraphic Analysis, McIlroy D., Ed. (Geological Society, 2004), pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchman A., Wetzel A., “Deep-sea ichnology: The relationships between depositional environment and endobenthic organisms” in Deep-Sea Sediments, vol. 63 of Developments in Sedimentology, HüNeke H., Mulder T., Eds. (Elsevier, 2011), pp. 517–556. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehane J. R., Ekdale A. A., Pitfalls, traps, and webs in ichnology: Traces and trace fossils of an understudied behavioral strategy. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 375, 59–69 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodríguez-Tovar F. J., Ichnological analysis: A tool to characterize deep-marine processes and sediments. Earth-Sci. Rev. 228, 104014 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buatois L. A., Mángano M. G., Ichnology: Organism-Substrate Interactions in Space and Time (Cambridge University Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seilacher A., “Pattern analysis of Paleodictyon and related trace fossils” in Trace Fossils 2, vol. 9 of Geological Journal Special Issue, Crimes T. P., Harper J. C., Eds. (Seel House Press, 1977), pp. 289–334. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller W. III, Mystery of the graphoglyptids. Lethaia 47, 1–3 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leszczynski S., Oxygen-related controls on predepositional ichnofacies in turbidites, Guipúzcoan Flysch (Albian–lower Eocene), northern Spain. Palaios 6, 271–280 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miguez-Salas O., et al. , Northernmost (Subarctic) and deepest record of Paleodictyon: Paleoecological and biological implications. Sci. Rep. 13, 7181 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mángano M. G., Buatois L. A., Decoupling of body-plan diversification and ecological structuring during the Ediacaran-Cambrian transition: Evolutionary and geobiological feedbacks. Proc. B Roy. Soc. 281, 1–9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyle R. A., Dahl T. W., Bjerrum C. J., Canfield D. E., Bioturbation and directionality in Earth’s carbon isotope record across the Neoproterozoic-Cambrian transition. Geobiology 16, 252–278 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buatois L. A., et al. , Quantifying ecospace utilization and ecosystem engineering during the early Phanerozoic – the role of bioturbation and bioerosion. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb0618 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cribb A. T., et al. , Ediacaran-Cambrian bioturbation did not extensively oxygenate sediments in shallow marine ecosystems. Geobiology 21, 435–453 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harper D. A., et al. , The Furongian (late Cambrian) biodiversity gap: Real or apparent? Palaeoworld 28, 4–12 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du M., Li H., Tan J., Wang Z., Wang W., The bias types and drivers of the Furongian Biodiversity Gap. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 612, 111394 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mángano M. G., Droser M., “The ichnologic record of the Ordovician radiation” in The Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event, Webby B. D., Droser M. L., Paris F., Percival I. G., Eds. (Columbia University Press, 2004), pp. 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mángano M. G., Buatois L. A., Wilson M. A., Droser M. L., “The Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event” in The Trace-Fossil Record of Major Evolutionary Changes, Vol. 1: Precambrian and Paleozoic, Topics in Geobiology 39, Mángano M. G.,Buatois L. A., Eds. (Springer, 2016), pp. 127–156. [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacNaughton R. B., Narbonne G. M., Dalrymple R. W., Neoproterozoic slope deposits, Mackenzie Mountains, northwestern Canada: Implications for passive-margin development and Ediacaran faunal ecology. Can. J. Earth Sci. 37, 997–1020 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buatois L. A., Mángano M. G., Early colonization of the deep sea: Ichnologic evidence of deep-marine benthic ecology from the Early Cambrian of northwest Argentina. Palaios 18, 572–581 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mángano M. G., Buatois L. A., “The Cambrian explosion” in The Trace-Fossil Record of Major Evolutionary Changes in Precambrian and Paleozoic, Topics in Geobiology 39, Mángano M. G., Buatois L. A., Eds. (Springer, 2016), vol. 1, pp. 73–126. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crimes T. P., Fedonkin M. A., Evolution and dispersal of deepsea traces. Palaios 9, 74–83 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen S., Palacios T., A peri-Gondwanan cradle for the trace fossil Paleodictyon? Evol. Biol. 6, 121–156 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crimes T. P., García Hidalgo J. F., Poiré D. G., Trace fossils from Arenig flysch sediments of Eire and their bearing on the early colonisation of the deep seas. Ichnos 2, 61–77 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buatois L. A., Mángano M. G., Brussa E., Benedetto J. L., Pompei J., The changing face of the deep: Colonization of the Early Ordovician deep-sea floor, Puna, northwest Argentina. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 280, 291–299 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erwin D. H., Disparity: Morphological pattern and context. Palaeontology 50, 57–73 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edwards C. T., Links between early Paleozoic oxygenation and the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE): A review. Palaeoworld 28, 37–50 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kozik N. P., Young S. A., Lindskog A., Ahlberg P., Owens J. D., Protracted oxygenation across the Cambrian-Ordovician transition: A key initiator of the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event? Geobiology 21, 323–340 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pohl A., Nardin E., Vandenbroucke T. R., Donnadieu Y., “The Ordovician ocean circulation: A modern synthesis based on data and models” in A Global Synthesis of the Ordovician System: Part 1, Harper D. A. T., Lefebvre B., Percival I. G., Servais T., Eds. (Geological Society, London, Special Publications 532, 2023), pp.157–169. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rona P. A., et al. , Paleodictyon nodosum: A living fossil on the deep-sea floor. Deep Sea Res. 56, 1700–1712 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kikuchi K., Naruse H., Morphological function of trace fossil Paleodictyon: An approach from fluid simulation. Paleontol. Res. 26, 378–389 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uchman A., The Ophiomorpha rudis ichnosubfacies of the Nereites ichnofacies: Characteristics and constraints. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 276, 107–119 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harper D., “Late Ordovician mass extinctions” in Encyclopedia of Geology, Alderton D., Elias S. A., Eds. (Elsevier, 2021), pp. 617–627. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Powichrowski L. K., Trace fossils from the Helminthoid Flysch (Upper Cretaceous- Paleocene) of the Ligurian Alps (Italy): Development of deep marine ichnoassociations in fan and basin plain environments. Eclogue Geol. Helv. 82, 385–411 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paulmier A., Ruiz-Pino D., Oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) in the modern ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 80, 113–128 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gooday A. J., et al. , Habitat heterogeneity and its influence on benthic biodiversity in oxygen minimum zones. Mar. Ecol. 31, 125–147 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helly J. J., Levin L. A., Global distribution of naturally occurring marine hypoxia on continental margins. Deep Sea Res. 51, 1159–1168 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobs D. K., Lindberg D. K. D. R., Oxygen and evolutionary patterns in the sea: Onshore/offshore trends and recent recruitment of deep-sea faunas. PNAS 95, 9396–9401 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rex M. A., Etter R. J., Deep-Sea Biodiversity (Harvard University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayward B. W., Global deep-sea extinctions during the Pleistocene ice ages. Geology 29, 599–602 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas E., “Cenozoic mass extinctions in the deep sea: What perturbs the largest habitat on Earth?” in Large Ecosystem Perturbations: Causes and Consequences, Monechi S., Coccioni R., Rampino M. R., Eds. (GSA Special Paper, 2007), vol. 424, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 50.López Cabrera M. I., Olivero E. B., Carmona N. B., Ponce J. J., Cenozoic trace fossils of the Cruziana, Zoophycos and Nereites ichnofacies from the Fuegian Andes, Argentina. Ameghiniana 45, 377–392 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Becker R. T., Königshof P., Brett C. E., “Devonian climate, sea level and evolutionary events: An introduction” in Devonian Climate, Sea Level and Evolutionary Events, Becker R. T., Königshof P., Brett C. E., Eds. (Geological Society, London, Special Publications 423, 2016), pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Königshof P., et al. , “Shallow-water facies setting around the Kačák Event: A multidisciplinary approach” in Devonian Climate, Sea Level and Evolutionary Events, Becker R. T., Königshof P., Brett C. E., Eds. (Geological Society, London, Special Publications 423, 2016), pp. 171–199. [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Hengstum P. J., Gröcke D. R., Stable isotope record of the Eifelian-Givetian boundary Kačák–otomari Event (Middle Devonian) from Hungry Hollow, Ontario Canada. Can. J. Earth Sci. 45, 353–366 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Capel E., et al. , The Silurian-Devonian terrestrial revolution: Diversity patterns and sampling bias of the vascular plant macrofossil record. Earth-Sci. Rev. 231, 104085 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scotese C. R., An atlas of Phanerozoic paleogeographic maps: The seas come in and the seas go out. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 49, 679–728 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bromley R. G., Trace Fossils. Biology, Taphonomy and Applications (Chapmam & Hall, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uchman A., Taxonomy and palaeoecology of flysch trace fossils: The Marnoso-arenacea Formation and associated facies (Miocene, Northern Apennines, Italy). Beringeria 15, 1–115 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uchman A., Taxonomy and ethology of flysch trace fossils: Revision of the Marian Ksiazkiewicz collection and studies of complementary material. Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol. 68, 105–218 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uchman A., Eocene flysch trace fossils from the Hecho Group of the Pyrenees, northern Spain. Beringeria 28, 3–41 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buatois L. A., Mángano M. G., Ichnodiversity and ichnodisparity: Significance and caveats. Lethaia 46, 281–292 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ekdale A. A., “Abyssal trace fossils in worldwide Deep Sea Drilling Project cores” in Trace Fossils 2, vol. 9 of Geological Journal Special Issue, Crimes T. P., Harper J. C., Eds. (Seel House Press, 1977), pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uchman A., The Ophiomorpha rudis ichnosubfacies of the Nereites ichnofacies: Characteristics and constraints. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 276, 107–119 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wetzel A., Uchman A., “Hemipelagic and pelagic basin plains” in Trace Fossils as Indicators of Sedimentary Environments in of Developments in Sedimentolog y, Knaust D., Bromley R. G., Eds. (Elsevier, 2012), vol. 64, pp. 673–701. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Minter N. J., Buatois L. A., Mángano M. G., “The conceptual and methodological tools of ichnology” in The Trace-Fossil Record of Major Evolutionary Changes, Vol. 1: Precambrian and Paleozoic, Topics in Geobiology 39, Mángano M. G., Buatois L. A.. Eds. (Springer, 2016), pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Minter N. J., et al. , Early bursts of diversification defined the faunal colonization of land. Nature Ecol. & Evol. 1, 0175 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bush A. M., Bambach R. K., Erwin D. H., “Ecospace utilization during the Ediacaran radiation and the Cambrian eco-explosion” in Quantifying the Evolution of Early Life, Topics in Geobiology 36, Laflamme M., Schiffbauer J., Dornbos S., Eds. (Springer, 2011), pp. 111–133. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seilacher A., Aberrations in bivalve evolution related to photo-and chemosymbiosis. Hist. Biol. 3, 289–311 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Buatois L. A., Mángano M. G., “The trace-fossil record of organism–matground interactions in space and time” in Microbial Mats in Siliciclastic Depositional Systems Through Time, Noffke N., Chafetz H., Eds. (SEPM Special Publication, 2012), vol. 101, pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dunhill A. M., Hannisdal B., Brocklehurst N., Benton M. J., On formation-based sampling proxies and why they should not be used to correct the fossil record. Palaeontology 61, 119–132 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hammer Ø., Harper D. A. T., Ryan P. D., PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 1–9 (2001). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.