Abstract

Hyperandrogenism—clinical features resulting from increased androgen production and/or action—is not uncommon in peripubertal girls. Hyperandrogenism affects 3–20% of adolescent girls and often is associated with hyperandrogenemia. In prepubertal girls, the most common etiologies of androgen excess are premature adrenarche (60%) and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) (4%). In pubertal girls, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (20–40%) and CAH (14%) are the most common diagnoses related to androgen excess. Androgen-secreting ovarian or adrenal tumors are rare (0.2%). Early pubic hair, acne, and/or hirsutism are the most common clinical manifestations, but signs of overt virilization in adolescent girls—rapid progression of pubic hair or hirsutism, clitoromegaly, voice deepening, severe cystic acne, growth acceleration, increased muscle mass, and bone age advancement past height age—should prompt detailed evaluation. This article addresses the clinical manifestations of and management considerations for non-PCOS related hyperandrogenism in adolescent girls. We propose an algorithm to aid diagnostic evaluation of androgen excess in this specific patient population.

Keywords: hyperandrogenism, adolescent, puberty, girls, androgen

Introduction

Hyperandrogenism is defined as clinical and/or biochemical features of increased androgen production and/or action, and is common in adolescent girls and women. Hyperandrogenism affects 3–20% of adolescents1–3, depending on the population studied, and may be attributed to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in 20–40%1,2,4. The estimated prevalence of non-PCOS-related hyperandrogenism is 3–16%, while the estimated prevalence of non-PCOS-related biochemical hyperandrogenemia is 3–7%1–3,5.

All hyperandrogenism—whether related to PCOS or otherwise—is important to address. Clinical hyperandrogenism (e.g., hirsutism) is commonly an important concern to patients and may negatively impact psychological and social wellbeing. Moreover, non-PCOS-related hyperandrogenism may indicate (or contribute to) risks of elevated body mass index (BMI), metabolic syndrome, and dysglycemia6, much like the well-known association of PCOS with features of metabolic syndrome7. A number of conditions other than PCOS should be considered in each adolescent presenting with hyperandrogenism, in large part because treatment approaches and comorbidities may differ from those of PCOS. Herein we review the clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management of non-PCOS-related hyperandrogenism in adolescent girls.

Clinical Manifestations

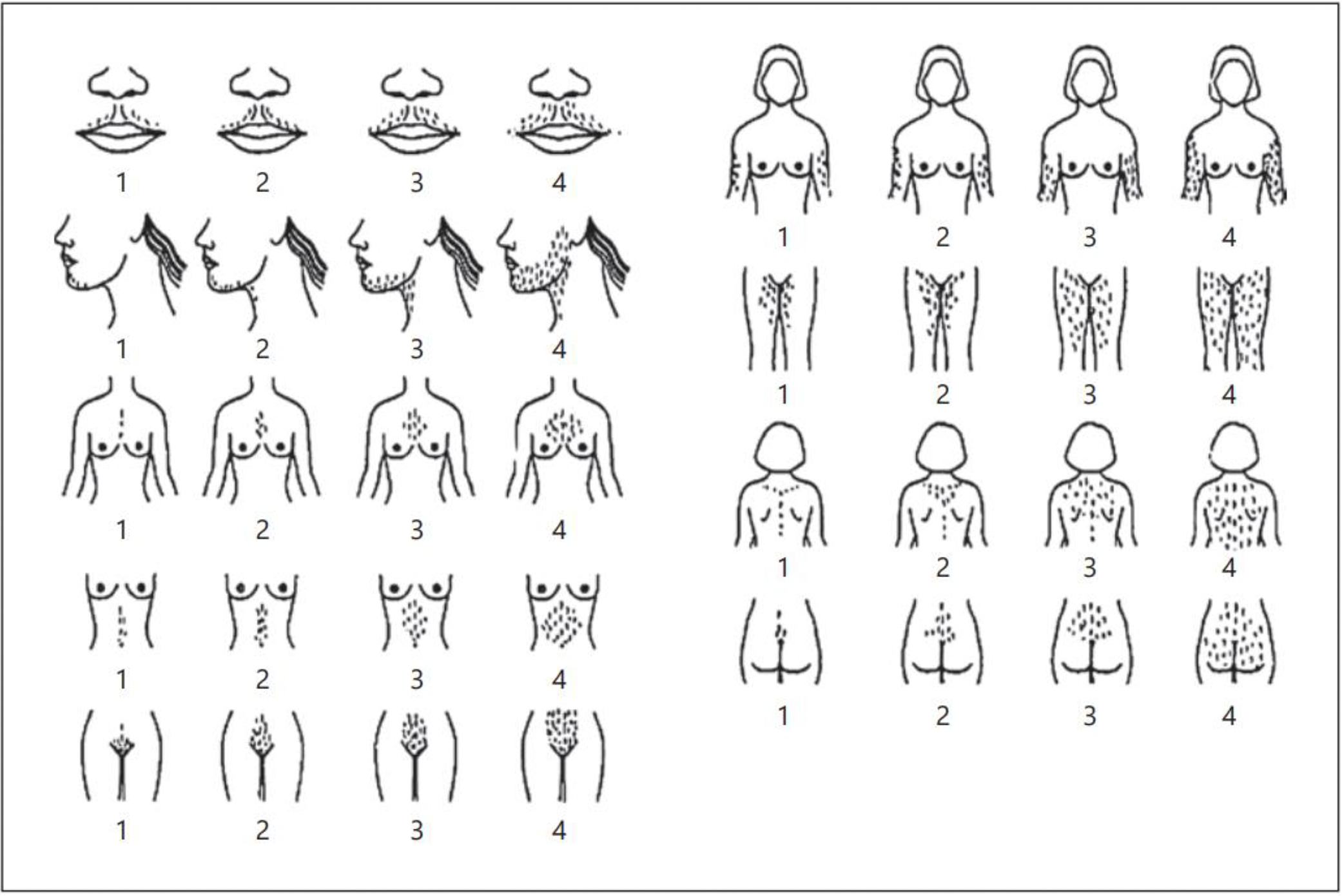

Hirsutism is defined as excess growth of dark and/or coarse terminal hair in a male-like distribution, and must be distinguished from hypertrichosis, the presence of generalized excessive fine vellus hair growth8. The modified Ferriman-Gallwey scoring system is the most common tool to assess hirsutism in women. This system involves grading terminal hair growth by assigning a score—ranging from 0 (absence) to 4 (extensive)—for 9 different body sites: upper lip, chin, chest, upper and lower back, upper and lower abdomen, arm, and thigh (Fig. 1)9. A cut-off sum of scores ≥4–6 has been suggested to define hirsutism in adult women by the 2018 International PCOS Consensus Guideline, based on the 85th percentile of scores and cluster analysis in relation to PCOS features10. Limitations include its subjective nature with high inter-observer variability; lack of scoring for other androgen-sensitive areas (e.g., sideburns, buttocks, and perineum); and inability to capture the impact of severe focused hirsutism. Additionally, it is difficult to score women with blond hair or prior cosmetic surgery10. Importantly, normal scores differ according to ethnicity and have not been established in adolescents, who likely have lower scores for degree of hyperandrogenemia due to limited exposure time. Therefore, the precise role of Ferriman-Gallwey scoring in adolescents remains uncertain.

Figure 1.

Modified Ferriman-Gallwey grading system for terminal hair growth at androgen-sensitive sites. (Reprinted with permission from Yildiz BO, Bolour S, Woods K, Moore A, Azziz R. Visually scoring hirsutism. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(1):51–64.)

Acne is common in adolescents, and androgen excess may contribute to acne via stimulation of sebaceous gland growth and sebum production. However, other non-androgen-related factors—such as colonization with Propionibacterium acnes and tissue inflammatory response—contribute to acne, which may explain the poor correlation between acne symptom severity and androgen levels11.

At the extreme, markedly elevated serum androgen concentrations can lead to virilization, suggested by rapid progression of pubic hair or hirsutism, clitoromegaly, voice deepening, severe cystic acne, growth acceleration, increased muscle mass, frontal balding, and bone age advancement past height age12.

Defining Hyperandrogenemia in Adolescents

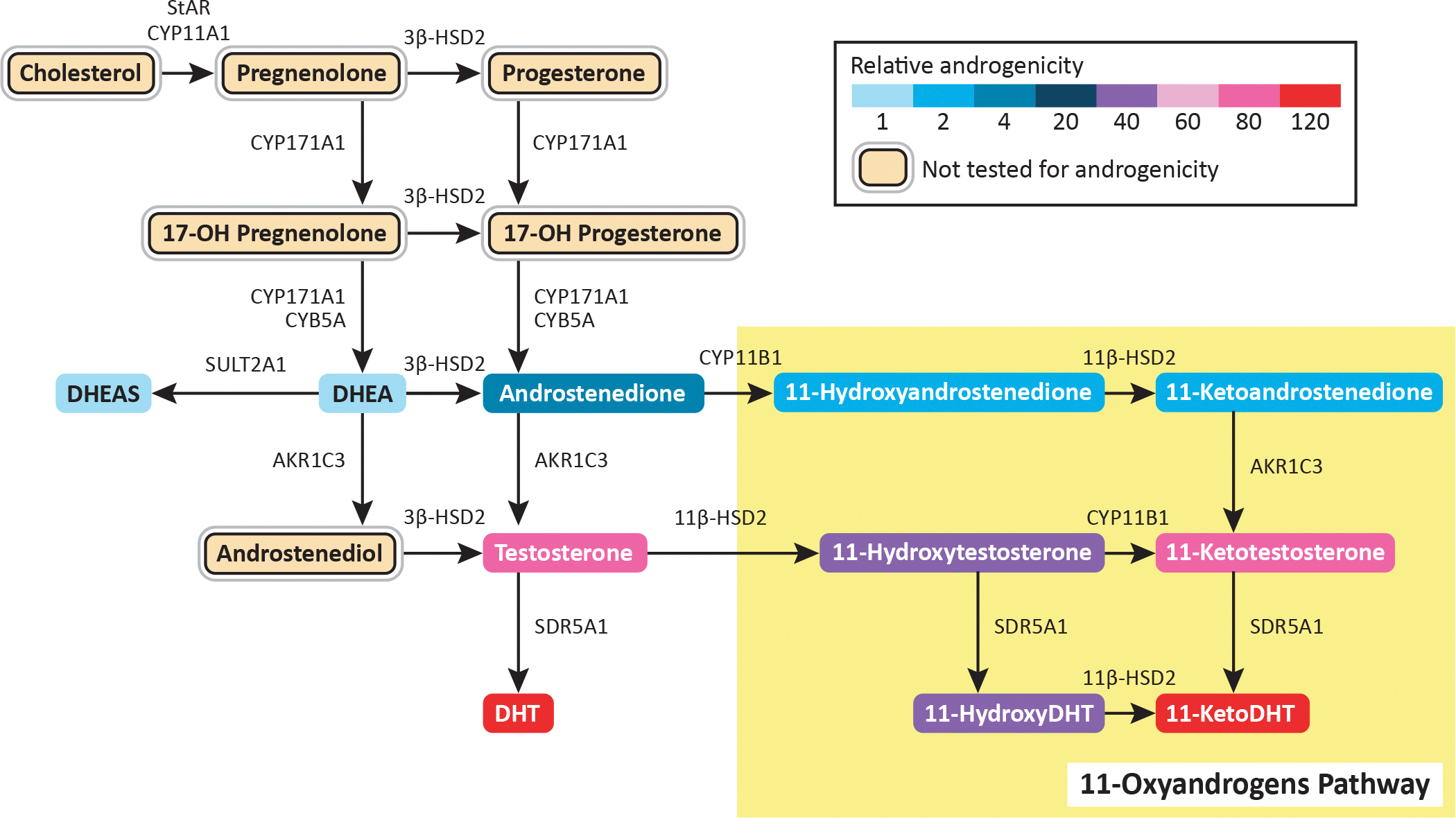

The steroidogenic pathways for the androgens considered most relevant to clinical androgen excess are illustrated in Fig 2. 13,14 The first androgens to increase in girls are adrenal cortical androgens, predominantly dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), due to increases in 17,20-lyase and sulfotransferase activities and a decrease in 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3βHSD) activity, as part of adrenarche. Adrenarche is independent from gonadotropin secretion15 and is characterized biochemically by a distinct rise of DHEA-S to levels ≥ 40 – 60 mcg/dL around age 6 – 8 yr16,17. Adrenarche manifests clinically as the development of pubic hair (pubarche), axillary hair, apocrine odor, oily skin, and often acne.

Figure 2.

Steroidogenic pathways for clinically relevant androgen production in girls. (Adapted with permission from Rosenfield RL. Normal and premature adrenarche. Endocr Rev. 2021 Mar 31:bnab009. Online ahead of print. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/edrv/advance-article/doi/10.1210/endrev/bnab009/6206746. Accessed May 25, 2021; and from Turcu AF, Rege J, Auchus RJ, Rainey WE. 11-Oxygenated androgens in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020 May;16(5):284–296.)

Levels of testosterone (T) also increase throughout puberty in normal girls18, including prior to thelarche19. The precise source of such T increases are unclear, but may be of adrenal origin early in puberty, with increasing ovarian contribution by mid- to late puberty20. It has been recently recognized that 11-oxygenated C19 androgens—generated in part via aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 (AKR1C3) activity in the adrenal gland and adipose tissue—are important contributors to androgen excess in adolescent girls and women. Such androgens include 11-ketotestosterone (11-KT), which binds and activates the androgen receptor with the same affinity as T. 11-KT levels are elevated in girls with premature adrenarche, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), PCOS, and obesity21–24.

Several practical considerations pertain to the assessment of serum androgen levels in adolescent girls. Assessments must consider the patient’s age and pubertal (Tanner) stage. The absence of normal adolescent references ranges for many assays has made determination of hyperandrogenemia in adolescents especially challenging. Serum T levels are much lower in girls compared to women and especially men, and commercial T assays have historically been beset by poor analytical sensitivity and poor specificity at low concentrations. Although some RIA testosterone assays may perform well at low levels25, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry is largely viewed as the assay method of choice when available.

Nearly 98% of circulating testosterone is bound to sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) or albumin, and the unbound (“free”) T is felt to be the biologically active fraction of circulating T. Indeed, free T—measured via equilibrium dialysis techniques or calculated using total T and SHBG levels—has ~50% greater sensitivity to detect hyperandrogenemia compared to total T alone and is widely considered to be the best single indicator of hyperandrogenism26. Testosterone levels may vary according to time of day, being higher in the morning, in addition to cycle stage in post-menarcheal girls, being higher during mid-cycle26. Whenever an accurate assessment of ovarian androgens is required, hormonal contraceptives should be withdrawn 2–3 months before testing because they can suppress ovarian androgen production (via gonadotropin suppression) and because estradiol can increase the production of SHBG by the liver26.

Premature Adrenarche

Premature adrenarche is defined clinically as idiopathic pubarche before age 8 yr in girls (9 yr in boys)27, based on the original clinical observations of Marshall and Tanner. (Although studies of 24-hr urinary androgen metabolites suggest that adrenarche may begin as early as age 3 yr28, pubarche typically occurs much later.) Premature adrenarche is the most common etiology of androgen excess in prepubertal children, affecting 61% of referred children. It occurs mostly in girls—79% of those with premature adrenarche—and is associated with elevations in DHEA-S in 85%, androstenedione (A4) in 26%, and T in 9%4. Clinical signs of premature adrenarche also include increased height growth and moderately advanced bone age (≤ + 2 SD, correlated to height age)27, but girls are not at risk for short stature30,31. Premature adrenarche is unrelated to breast development or gonadotropin release17; some, but not all, studies suggest earlier age of menarche, but within the range of ages considered normal.

Although DHEA-S is a weak androgen, it may be converted to more potent A4 and T by non-adrenal tissues12. A4 and T are moderately elevated for age, but normal for pubic hair stage27. DHEA-S levels may be higher than expected even for pubic hair stage27, but are usually suppressible by dexamethasone30. Importantly, premature adrenarche should not be associated with clitoral enlargement, voice deepening, cystic acne, hirsutism, breast development, vaginal bleeding, bone age greater than height age, or androgen (i.e., A4 or T) levels elevated for pubic hair stage12,27. Premature adrenarche is also a diagnosis of exclusion. Providers should consider central or peripheral precocious puberty, virilizing adrenal or gonadal tumor, non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia, or exogenous androgen exposure as differential diagnoses.

Several risk factors are associated with early adrenarche. Race is associated with earlier adrenarche, as more black girls have pubic hair at ages 6 and 8 (9.5% and 34.3%) compared to white girls (1.4% and 7.7%)33. Nutritional status also contributes to adrenarche, and weight gain, obesity, and insulin resistance in childhood put girls at risk for premature adrenarche34–37.

Premature adrenarche is no longer considered a benign variant of normal puberty, as it portends future metabolic and reproductive endocrine risk. Girls with premature adrenarche in the U.S., Finland, and Spain may demonstrate signs of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, including acanthosis nigricans, hyperinsulinemia, dyslipidemia, increased waist circumference, and increased fat mass (with or without elevated BMI)38–42. Such metabolic abnormalities may persist into adulthood. For example, Finnish women with history of premature adrenarche exhibited more acanthosis nigricans, decreased insulin sensitivity, elevated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and larger central fat depots compared to BMI-matched controls43.

Likewise, premature adrenarche is a risk factor for the development of PCOS. Catalan girls with premature adrenarche demonstrated peripubertal worsening of hyperandrogenemia—including ovarian hyperandrogenemia—along with metabolic derangements, leading to a higher prevalence of ovulatory dysfunction by 3 years after menarche44–46. Similarly, irregular menses, hirsutism, hyperandrogenemia, and exaggerated androgen responses to acute gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist stimulation testing developed in half of such girls by late puberty, suggesting the development of PCOS47. The precise nature of the relationship between premature adrenarche and PCOS is unclear. The relationship may possibly reflect a more general exaggeration of androgen steroidogenesis—including in the ovary—related to inherited enzyme abnormalities or steroidogenesis-modifying factors such as hyperinsulinemia48,49. In addition, early hyperandrogenemia may predispose girls to neuroendocrine dysfunction (e.g., luteinizing hormone [LH] excess) during the pubertal transition, which may promote ovarian dysfunction48.

Since the consequences of premature adrenarche are primarily metabolic with an increased risk of PCOS, healthy lifestyle and maintenance (or achievement) of normal body weight should be encouraged. No specific pharmacological treatment is recommended, however. In Catalan girls with premature adrenarche, metformin was associated with less adiposity, later ages of thelarche and menarche, slowed bone maturation with better height, less hirsutism and oligomenorrhea, lower androgen levels, and lower risk of adolescent PCOS50–52. Nonetheless, additional longitudinal studies in other populations are needed to assess whether this or other pharmacological treatments for premature adrenarche are helpful.

Non-Classical Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

Nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (NCCAH) accounts for 6% of children and adolescents (4% prepubertal; 14% pubertal) presenting with androgen excess, compared to 2–5% of women 4,7,53. Although the overall contribution to girls presenting with androgen excess is relatively low, NCCAH is the most common autosomal recessive endocrine disorder. Incidence rates of NCCAH are known to vary widely in different ethnic populations, occurring in approximately 0.1% of Caucasians, less commonly in African populations, and more commonly in Yugoslav (1.6%), Hispanic (1.9%), and Ashkenazi Jewish (3.7%) populations54,55. Because of these known genetic differences in prevalence, NCCAH will not be applicable to many populations internationally.

NCCAH represents a mild form of CAH: such patients are not born with genital ambiguity, and they are not clinically cortisol deficient because ACTH elevations can adequately compensate for the mild enzymatic defect56. Clinical findings may start from age 5 yr but usually emerge in late childhood, adolescence, and adulthood57. In 220 women with NCCAH, only 11% had symptoms—primarily premature pubarche—before age 10 58. Hyperandrogenemia (elevated A4 in 86%, T in 50%, DHEA-S in 33%) constitutes the main basis for symptoms4. Other than premature pubarche, clinical findings in girls may include labial adhesion, perianal hair, clitoromegaly, increased bone age, early apocrine odor, greasy hair, acne, and a short height prediction versus mid-parental target height57. During adolescence and adulthood, NCCAH may manifest as hirsutism (59–78%), anovulatory menstrual dysfunction (55%), acne (33%), decreased fertility (12%), and androgenic alopecia59,60. Indeed, NCCAH may masquerade as PCOS—NCCAH is an important exclusion criterion for PCOS—and 56%-73% of such patients otherwise appear to meet criteria for PCOS53,61.

Since the most common form of CAH is caused by 21OH deficiency, screening for NCCAH is done via basal (unstimulated) serum 17OHP levels drawn at 8 am during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (when applicable)62. Levels < 200 ng/dL (6 nmol/L) exclude NCCAH with 95% specificity and sensitivity, while levels > 1000 ng/dL (45 nmol/L) are diagnostic60. Afternoon 17OHP measurements can yield false negative results in 2–9% of patients with NCCAH, and luteal phase 17OHP may be > 200 ng/dL in approximately 50% of healthy females without NCCAH61–63. When basal 17OHP is 200–1000 ng/dL, an ACTH stimulation test should be performed with 17OHP drawn before and 60 minutes after cosyntropin (synthetic ACTH) 250 mcg IV57. ACTH stimulation testing should also be considered in girls with premature adrenarche if bone age-to-height age ratio is > 1, if basal androgen levels are elevated (DHEAS > 130 mcg/dL, T > 35 ng/dL), or if there are atypical features such as cystic acne or virilization12,27. ACTH-stimulated 17OHP > 1000 ng/dL (30 nmol/L) confirms NCCAH, although lower levels do not completely exclude NCCAH (or carrier status for classical CAH)62. Some experts suggest also measuring 17-OH pregnenolone, 11-deoxycortisol, cortisol, DHEA, and A4 during the ACTH stimulation test to detect rare forms of CAH or other virilizing disorders12. While genetic testing is not a primary diagnostic tool for NCCAH at this time, it may be helpful for diagnosis if ACTH responses are indeterminate or to inform genetic counseling62,64.

Patients with NCCAH are treated according to their symptoms. Glucocorticoids are used to treat girls with NCCAH if they have early, rapid progression of pubarche with advanced bone age that will adversely affect adult height, or if they develop symptoms of overt virilization suggesting more severe enzymatic dysfunction62. When needed, early initiation of glucocorticoids (i.e., one year prior to puberty, bone age < 9 yr) can protect genetically-determined height potential63. Hydrocortisone, which is preferred over prednisone or dexamethasone due to their growth limiting effects, is administered at a dose of 6–15 mg/m2/day, divided into 3 doses60. Hydrocortisone may be discontinued when such girls reach adult height, especially if there are no findings of hyperandrogenism. While adolescents with irregular menses and acne may benefit from continued low dose glucocorticoid therapy, glucocorticoids can have undesirable long-term effects, and they are unlikely to improve hirsutism62. Accordingly, women with NCCAH and patient-important hyperandrogenism are often treated with oral contraceptives with or without spironolactone, with glucocorticoid therapy reserved for recalcitrant symptoms or infertility62,66–68. When used for NCCAH-related infertility, glucocorticoids that are inactivated by placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 (e.g., prednisone, prednisolone, or hydrocortisone) are recommended68. Glucocorticoid stress dosing for major surgery or serious illness/injury is not required for NCCAH patients unless cortisol response to ACTH stimulation is < 14–18 mcg/dL or if the patient develops iatrogenic adrenal insufficiency from chronic glucocorticoid treatment62,69,70.

Androgen-secreting tumors

Androgen-secreting tumors are rare, occurring in 0.2% of children and adolescents (and 0.2% of women) with symptoms of androgen excess4,7,53, and may arise from the ovaries or adrenal glands. Androgen-secreting ovarian tumors include Leydig-Sertoli cell tumors, other steroid cell tumors, and ovarian thecomas; and adrenal adenomas and carcinomas may secrete androgens. Such neoplasms should be considered in patients with rapidly progressive symptoms (over weeks or months) and/or virilization71. Symptoms of virilization include enlargement of the clitoris (transverse diameter >10 mm), increased muscularity, deepening of the voice, severe cystic acne or seborrhea, and male-pattern balding71,72.

Androgen-secreting tumors should be considered when the serum testosterone is > 150 – 200 ng/dL (5–7 nmol/L, or 2–3 times the upper limit of normal)71,72 or when DHEA-S is > 700 mcg/dL (>19 mmol/L)26,73. Elevated testosterone (often with elevated androstenedione) without an elevation of DHEAS suggests an ovarian source71,72. Small ovarian tumors can demonstrate episodic secretion of androgens, and repeat androgen measurements may be required when index of suspicion remains high71. Androgen suppression by combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) has been suggested as a way to assess for functional ovarian hyperandrogenism, but case reports suggest that OCPs can normalize androgen levels in some cases of androgen-secreting ovarian tumors71,73. Elevated DHEA-S suggests an adrenal source, but an androgen-secreting adrenal tumor is unlikely if DHEA-S can be suppressed to normal levels with dexamethasone12,73.

Imaging is reserved for patients with a high index of suspicion based on clinical and biochemical data, since discovery of incidentalomas is not uncommon (especially in the adrenal gland)74. The adrenal glands are easily visible by CT or MRI71. For ovarian tumors, transvaginal ultrasound is often the first modality used in adult women, but MRI may be better suited for adolescents to avoid vaginal manipulation in young patients and to visualize small or isoechoic Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors71,75.

Other Rare Causes of Hyperandrogenism

Rare causes of hyperandrogenism should be considered in the setting of unexplained androgen excess, but other symptoms usually predominate in such conditions. Central precocious puberty may present with premature pubarche, representing 2.5% of cases of androgen excess, but would also be associated with breast development4,12. Cushing’s syndrome occurs in 0.2% in children and adolescents with androgen excess4 and should be considered in adolescent girls with a PCOS-like phenotype, particularly if they have other symptoms that increase pretest probability (e.g., growth retardation, hypertension, proximal muscle weakness, wide violaceous striae)76. Progressive virilization at the time of puberty can be a sign of a disorder of sexual development, including 5α-reductase deficiency77. Acromegaly-related insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia can lead to hyperandrogenism and may be associated with tall stature in girls who are still growing78. Exogenous androgens may lead to hyperandrogenism in adolescents, especially with exposure to topical testosterone (e.g., male contacts) or nutritional supplements.

Obesity-related hyperandrogenemia

Hyperandrogenemia may be associated with obesity in peripubertal girls, even prior to thelarche, with observed elevations of serum A4, T, and free T levels18,79. According to one study, approximately 60% of obese girls exhibit elevated morning free T levels80. The development of hyperandrogenemia in pre- and early pubertal girls with obesity may suggest an adrenal source, as significant ovarian androgen production is presumably absent in such girls. Increased central activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and direct activity of leptin or insulin on adrenal steroidogenesis have also been proposed as potential mechanisms for obesity-related hyperandrogenemia in early puberty79. By late puberty, girls with obesity demonstrate 4-fold higher post-dexamethasone levels of free T and 2-fold higher A4 and free T responses to cosyntropin, suggesting both ovarian and adrenal contributions to obesity-associated hyperandrogenemia in later puberty20.

In prepubertal obese girls, weight loss of at least 0.5 BMI SDS is associated with improved insulin resistance and decreased A4 and T levels79. However, the relationship between obesity and androgen excess may be bidirectional. For example, testosterone administration can promote visceral fat accumulation and insulin resistance in adolescent female nonhuman primates in the setting of high-fat/calorie diet81,82.

Androgen excess as possible precursor to PCOS

Despite decades of intensive research, the etiology of PCOS remains enigmatic. For many women with PCOS, initial symptoms manifested during or shortly after puberty, and peripubertal hyperandrogenemia has been linked to the eventual development of full-blown PCOS. For example, as described above, girls with exaggerated adrenarche appear to be at higher risk for PCOS48. In addition, some evidence suggests a high prevalence of secondary PCOS—manifesting as ovarian hyperandrogenemia and LH excess—in women with virilizing CAH83.

We and others have raised concerns that peripubertal obesity-associated hyperandrogenemia may put girls at risk for adult PCOS84,85. This putative pathway toward PCOS may be different than for other girls at risk for PCOS. Compared to daughters of women with PCOS, premenarcheal girls with obesity-related androgen excess have lower SHBG and lower anti-Mullerian hormone86, suggesting a distinct phenotype with increased androgen bioavailability and fewer abnormalities of ovarian folliculogenesis.

While peripubertal androgen excess may simply represent an early marker of nascent PCOS, a number of findings indicate that androgen excess may also actively contribute to its development. Perhaps the most robust evidence that androgens contribute to the development of PCOS comes from animal studies. In rodents, sheep, and non-human primates, experimental prenatal androgenization is associated with numerous PCOS-like characteristics in adulthood, including ovulatory dysfunction, endogenous hyperandrogenemia, polyfollicular ovaries, and neuroendocrine abnormalities87. Peripubertal androgen administration in female rats also yields a number of PCOS-like features including ovulatory dysfunction, polyfollicular ovaries, increased adiposity, and insulin resistance87.

Although mechanisms are likely multifactorial, androgen excess may encourage the development of PCOS through neuroendocrine mechanisms88. For example, prenatally-androgenized animals exhibit neuroanatomical and functional neuronal changes that contribute to GnRH neuronal hyperactivity89–91. Peripubertal hyperandrogenemia may impair negative feedback suppression of LH (GnRH) pulse frequency as it does in adult PCOS92, since elevated fasting insulin levels are associated with similar impairment in adolescents93,94. Such effects of androgen excess on GnRH release may be especially relevant during critical developmental windows such as fetal development and puberty. Additional effects of peripubertal hyperandrogenemia—e.g., on adiposity, insulin resistance, and follicular dynamics—may be pertinent to the development of PCOS as well87.

Clinical Strategies

An algorithm to evaluate adolescent girls with symptoms of androgen excess is proposed in Fig 3. Any underlying medical condition related to hyperandrogenism should be treated according to pathology, as discussed above.

Figure 3.

Diagnostic algorithm for adolescent hyperandrogenism. BA = bone age; HA = height age; 17OHP = 17 hydroxyprogesterone; T = testosterone; DHEA-S = dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; DHEA = dehydroepiandrosterone; A4 = androstenedione; PCOS = polycystic ovary syndrome; 21-OH def = 21-hydroxylase deficiency; 3βHSD def = 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency; CAH = congenital adrenal hyperplasia; NCCAH = nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia; DSD = disorder of sexual development; SRY = sex-determining region of the Y chromosome. aIn any girl: clitoromegaly, voice deepening, frontal balding, rapid development of symptoms; in pre-menarcheal girls: moderate to severe comedonal acne (≥ 10 lesions)12, increased growth velocity; in peri-menarcheal girls: rapid onset hirsutism, moderate to severe inflammatory acne99. bGirls should be monitored for clinical worsening or development of irregular menses. cIrregular menses is defined as >90 day cycle length for any one cycle at > 1 yr after menarche; < 21 day or > 45 day cycle length at > 1 to < 3 yr after menarche; < 21 day or > 35 day cycle length at ≥ 3 yr after menarche99. Primary amenorrhea at 15 yr or > 3 yr post-thelarche should raise concerns99. dACTH stimulation test: Cosyntropin 250 mcg IV. Draw serum 17OHP (consider also DHEA, 17OH-Pregnenolone, A4, T) at baseline and 60 minutes12,27. eAssessment for cortisol excess/dexamethasone suppression test: Obtain 24 hr urine for free cortisol or 3 midnight salivary cortisol levels. First, consider a low dose dexamethasone suppression test. Draw at 8 am baseline T, cortisol, DHEA-S, other elevated androgens/precursors. Give dexamethasone 1 mg orally at midnight. Drawn 8 am repeat serum levels. For more definitive test, if androgen levels are not suppressed to normal levels by low dose dexamethasone test, give dexamethasone 1 mg BID × 5 days or 1 mg/m2 divided 3–4 times daily × 4 days with last dose morning day 5, as a definitive test to assess for an adrenal tumor12,73.

The Endocrine Society recommends treating patient-important hirsutism, defined as hirsutism causing patient distress66. The degree of hirsutism may not correlate well with serum androgen levels because the response of androgen-dependent follicles is variable within and among persons66. Initial measures for hirsutism may include shaving, plucking, waxing, or depilatory creams. While these measures work well for many, they can occasionally result in scarring, rashes, folliculitis, or hyperpigmentation.

First line pharmacologic treatment is combined oral contraceptives, which suppress ovarian androgen production and stimulate SHBG production66. However, OCPs may not fully lower non-ovarian androgen production and should not be used in girls who still have growth potential, due to the risk for premature fusion of growth plates, or in girls with medical contraindications for use of OCPs. Pharmacological interventions impact growth at the hair root, but patients may start noticing changes within 6 months and can expect to experience maximal effect after about 9 months95. If patient-important hirsutism persists after 6 months of OCP therapy, anti-androgen therapy with spironolactone may be added66. Finasteride—a 5α-reductase inhibitors—is less or equally effective compared to spironolactone26,66 but may have undesirable side effects, and flutamide is not recommended due to potentially serious hepatotoxicity. Cyproterone acetate (CPA)—a progestin that blocks the androgen receptor and 5α-reductase—is used in countries outside the U.S. and may be cycled with ethinyl estradiol (ethinyl estradiol 20–50 mcg/day × 3 weeks, CPA 50–100 mg/day during first 10 days of cycle) or combined in an oral contraceptive pill (2 mg CPA plus 35 mcg ethinyl estradiol)66. Drosperinone is another progestin with antiandrogen activity: when given at a dose of 3 mg within a combined oral contraceptive pill, its antiandrogen potency equates to approximately 25 mg spironolactone or 1 mg CPA66. Eflornithine—which inhibits a key step in hair growth—can be used topically to slow hair growth and is safe when combined with other therapies.

For patients with NCCAH, glucocorticoid therapy alone is unlikely to improve hirsutism, but may be added to oral contraceptives for recalcitrant symptoms, with or without spironolactone, at doses of prednisone 4–6 mg/day or dexamethasone 0.25 mg/day, titrated to prevent suppression of DHEA-S below 70 mcg/dL62,66–68. GnRH agonists are reserved for patients with severe ovarian hyperandrogenism for whom OCPs and antiandrogens are ineffective. GnRH agonists reversibly produce severe hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, but concomitant estradiol and progesterone therapy can be used to mitigate adverse effects of hypoestrogenism and bone loss26,66. Additionally, direct hair removal methods (e.g., electrolysis or photoepilation with laser or intense pulsed light) may be recommended after or alongside pharmacological treatment in women with patient-important hirsutism66.

Given the association of peripubertal obesity in girls with hyperandrogenemia in most studies18,96,97, weight reduction via lifestyle interventions may help lower androgen levels in peripubertal girls with obesity96 and adolescents with PCOS79,98. These results are likely the result of improved insulin sensitivity and may help girls with non-PCOS hyperandrogenemia, such as premature adrenarche, obesity-related hyperandrogenemia, and idiopathic hyperandrogenemia. Metformin has demonstrated reproductive and metabolic benefits in some studies of girls with premature adrenarche50–52, but is not recommended as a specific treatment for hirsutism due to lack of efficacy66.

Conclusions

Several diagnoses other than PCOS need to be considered in the evaluation of peripubertal girls with androgen excess. Most prepubertal girls presenting with symptoms of androgen excess will have premature adrenarche (61%), but NCCAH occurs in 6% of all peripubertal adolescents; thus, evaluation should include a morning serum 17OHP level. Signs of virilization or markedly elevated androgen levels should raise concern for an androgen-secreting tumor. During later puberty, ovarian androgen overproduction may emerge in girls at risk (e.g., daughters of women with PCOS, girls with obesity, girls with a history of premature adrenarche), and symptoms of PCOS may manifest across adolescence. NCCAH can closely mimic PCOS in older girls and should remain on the differential diagnosis. Hyperandrogenemia without other reproductive manifestations in adolescence may progress to PCOS in adulthood. Treatment strategies should be patient-focused and consider the underlying cause of androgen excess when known. Oral contraceptive pills are generally considered the first-line pharmacological therapy for hirsutism, but should not be used in girls who are still growing. Lifestyle interventions are important to improve androgen overproduction related to hyperinsulinemia and obesity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institutes of Health through R01 HD102060 (CMBS, CRM).

References

- 1.Hickey M, Doherty DA, Atkinson H, et al. Clinical, ultrasound and biochemical features of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents: implications for diagnosis. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(6):1469–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gambineri A, Fanelli F, Prontera O, et al. Prevalence of hyperandrogenic states in late adolescent and young women: epidemiological survey on italian high-school students. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(4):1641–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubey P, Reddy SY, Alvarado L, Manuel SL, Dwivedi AK. Prevalence of at-risk hyperandrogenism by age and race/ethnicity among females in the United States using NHANES III. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;260:189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Idkowiak J, Elhassan YS, Mannion P, et al. Causes, patterns and severity of androgen excess in 487 consecutively recruited pre- and post-pubertal children. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;180(3):213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Hooff MH, Voorhorst FJ, Kaptein MB, Hirasing RA, Koppenaal C, Schoemaker J. Endocrine features of polycystic ovary syndrome in a random population sample of 14–16 year old adolescents. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(9):2223–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torchen LC, Tsai JN, Jasti P, et al. Hyperandrogenemia is common in asymptomatic women and is associated with increased metabolic risk. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(1):106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azziz R, Sanchez LA, Knochenhauer ES, et al. Androgen excess in women: experience with over 1000 consecutive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(2):453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yilmaz B, Yildiz BO. Endocrinology of Hirsutism: From Androgens to Androgen Excess Disorders. Front Horm Res. 2019;53:108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yildiz BO, Bolour S, Woods K, Moore A, Azziz R. Visually scoring hirsutism. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(1):51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1602–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karrer-Voegeli S, Rey F, Reymond MJ, Meuwly JY, Gaillard RC, Gomez F. Androgen dependence of hirsutism, acne, and alopecia in women: retrospective analysis of 228 patients investigated for hyperandrogenism. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(1):32–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenfield RL. Normal and premature adrenarche. Endocr Rev. 2021. Mar 31:bnab009. Online ahead of print. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/edrv/advance-article/doi/10.1210/endrev/bnab009/6206746. Accessed May 25, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turcu AF, Rege J, Auchus RJ, Rainey WE. 11-Oxygenated androgens in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020. May;16(5):284–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pignatelli D, Pereira SS, Pasquali R. Androgens in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Front Horm Res. 2019;53:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wierman ME, Beardsworth DE, Crawford JD, et al. Adrenarche and skeletal maturation during luteinizing hormone releasing hormone analogue suppression of gonadarche. J Clin Invest. 1986;77(1):121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reiter EO, Fuldauer VG, Root AW. Secretion of the adrenal androgen, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, during normal infancy, childhood, and adolescence, in sick infants, and in children with endocrinologic abnormalities. J Pediatr. 1977;90(5):766–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sklar CA, Kaplan SL, Grumbach MM. Evidence for dissociation between adrenarche and gonadarche: studies in patients with idiopathic precocious puberty, gonadal dysgenesis, isolated gonadotropin deficiency, and constitutionally delayed growth and adolescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;51(3):548–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCartney CR, Blank SK, Prendergast KA, et al. Obesity and sex steroid changes across puberty: evidence for marked hyperandrogenemia in pre- and early pubertal obese girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(2):430–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitamura R, Yano K, Suzuki N, Ito Y, Makita Y, Okuno A. Diurnal rhythms of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, testosterone, and estradiol secretion before the onset of female puberty in short children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(3):1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burt Solorzano CM, Helm KD, Patrie JT, et al. Increased adrenal androgens in overweight peripubertal girls. J Endocr Soc. 2017;1(5):538–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Reilly MW, Kempegowda P, Jenkinson C, et al. 11-oxygenated C19 steroids are the predominant androgens in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(3):840–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rege J, Turcu AF, Kasa-Vubu JZ, et al. 11-ketotestosterone is the dominant circulating bioactive androgen during normal and premature adrenarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(12):4589–4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torchen LC, Sisk R, Legro RS, Turcu AF, Auchus RJ, Dunaif A. 11-oxygenated C19 steroids do not distinguish the hyperandrogenic phenotype of PCOS daughters from girls with obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turcu AF, Nanba AT, Chomic R, et al. Adrenal-derived 11-oxygenated 19-carbon steroids are the dominant androgens in classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(5):601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCartney CR, Burt Solorzano CM, Patrie JT, Marshall JC, Haisenleder DJ. Estimating testosterone concentrations in adolescent girls: Comparison of two direct immunoassays to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Steroids. 2018;140:62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenfield RL. Clinical practice. Hirsutism. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(24):2578–2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibanez L, Dimartino-Nardi J, Potau N, Saenger P. Premature adrenarche--normal variant or forerunner of adult disease? Endocr Rev. 2000;21(6):671–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remer T, Boye KR, Hartmann MF, Wudy SA. Urinary markers of adrenarche: reference values in healthy subjects, aged 3–18 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):2015–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sopher AB, Jean AM, Zwany SK, et al. Bone age advancement in prepubertal children with obesity and premature adrenarche: possible potentiating factors. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(6):1259–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pere A, Perheentupa J, Peter M, Voutilainen R. Follow up of growth and steroids in premature adrenarche. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154(5):346–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibanez L, Virdis R, Potau N, et al. Natural history of premature pubarche: an auxological study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74(2):254–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oberfield SE, Amer T, Tyson D, et al. Altered sensitivity to low dose dexamethasone in a subset of patients with premature adrenarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(4):1102–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herman-Giddens ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, et al. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network. Pediatrics. 1997;99(4):505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ong KK, Potau N, Petry CJ, et al. Opposing influences of prenatal and postnatal weight gain on adrenarche in normal boys and girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2647–2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Remer T, Manz F. Role of nutritional status in the regulation of adrenarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(11):3936–3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jabbar M, Pugliese M, Fort P, Recker B, Lifshitz F. Excess weight and precocious pubarche in children: alterations of the adrenocortical hormones. J Am Coll Nutr. 1991;10(4):289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibanez L, Potau N, Marcos MV, de Zegher F. Exaggerated adrenarche and hyperinsulinism in adolescent girls born small for gestational age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(12):4739–4741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Utriainen P, Jaaskelainen J, Romppanen J, Voutilainen R. Childhood metabolic syndrome and its components in premature adrenarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(11):4282–4285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oppenheimer E, Linder B, DiMartino-Nardi J. Decreased insulin sensitivity in prepubertal girls with premature adrenarche and acanthosis nigricans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(2):614–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Potau N, Williams R, Ong K, et al. Fasting insulin sensitivity and post-oral glucose hyperinsulinaemia related to cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents with precocious pubarche. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2003;59(6):756–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ibanez L, Ong K, de Zegher F, Marcos MV, del Rio L, Dunger DB. Fat distribution in non-obese girls with and without precocious pubarche: central adiposity related to insulinaemia and androgenaemia from prepuberty to postmenarche. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2003;58(3):372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vuguin P, Linder B, Rosenfeld RG, Saenger P, DiMartino-Nardi J. The roles of insulin sensitivity, insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), and IGF-binding protein-1 and -3 in the hyperandrogenism of African-American and Caribbean Hispanic girls with premature adrenarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(6):2037–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liimatta J, Utriainen P, Laitinen T, Voutilainen R, Jaaskelainen J. Cardiometabolic risk profile among young adult females with a history of premature adrenarche. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3(10):1771–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ibanez L, Potau N, Zampolli M, Rique S, Saenger P, Carrascosa A. Hyperinsulinemia and decreased insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 are common features in prepubertal and pubertal girls with a history of premature pubarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(7):2283–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ibanez L, Potau N, Zampolli M, Street ME, Carrascosa A. Girls diagnosed with premature pubarche show an exaggerated ovarian androgen synthesis from the early stages of puberty: evidence from gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist testing. Fertil Steril. 1997;67(5):849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ibanez L, de Zegher F, Potau N. Anovulation after precocious pubarche: early markers and time course in adolescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(8):2691–2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ibanez L, Potau N, Virdis R, et al. Postpubertal outcome in girls diagnosed of premature pubarche during childhood: increased frequency of functional ovarian hyperandrogenism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76(6):1599–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burt Solorzano CM, McCartney CR. Polycystic ovary syndrome: ontogeny in adolescence. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2021;50(1):25–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodarzi MO, Carmina E, Azziz R. DHEA, DHEAS and PCOS. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;145:213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ibanez L, Valls C, Ong K, Dunger DB, de Zegher F. Metformin therapy during puberty delays menarche, prolongs pubertal growth, and augments adult height: a randomized study in low-birth-weight girls with early-normal onset of puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(6):2068–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ibanez L, Lopez-Bermejo A, Diaz M, Marcos MV, de Zegher F. Early metformin therapy (age 8–12 years) in girls with precocious pubarche to reduce hirsutism, androgen excess, and oligomenorrhea in adolescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(8):E1262–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Zegher F, Garcia Beltran C, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ibanez L. Metformin for rapidly maturing girls with central adiposity: less liver fat and slower bone maturation. Horm Res Paediatr. 2018;89(2):136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carmina E, Rosato F, Janni A, Rizzo M, Longo RA. Extensive clinical experience: relative prevalence of different androgen excess disorders in 950 women referred because of clinical hyperandrogenism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(1):2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Speiser PW, Dupont B, Rubinstein P, Piazza A, Kastelan A, New MI. High frequency of nonclassical steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37(4):650–667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson RC, Nimkarn S, Dumic M, et al. Ethnic-specific distribution of mutations in 716 patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia owing to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;90(4):414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Speiser PW. Nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2009;10(1):77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Witchel SF. Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012;19(3):151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moran C, Azziz R, Carmina E, et al. 21-Hydroxylase-deficient nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia is a progressive disorder: a multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1468–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chrousos GP, Loriaux DL, Mann DL, Cutler GB Jr. Late-onset 21-hydroxylase deficiency mimicking idiopathic hirsutism or polycystic ovarian disease. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(2):143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Witchel SF. Non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Steroids. 2013;78(8):747–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Livadas S, Dracopoulou M, Dastamani A, et al. The spectrum of clinical, hormonal and molecular findings in 280 individuals with nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia caused by mutations of the CYP21A2 gene. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;82(4):543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Speiser PW, Arlt W, Auchus RJ, et al. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(11):4043–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Azziz R, Hincapie LA, Knochenhauer ES, Dewailly D, Fox L, Boots LR. Screening for 21-hydroxylase-deficient nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia among hyperandrogenic women: a prospective study. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(5):915–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dorr HG, Schulze N, Bettendorf M, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in children and adolescents with nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2020;7(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weintrob N, Dickerman Z, Sprecher E, Galatzer A, Pertzelan A. Non-classical 21-hydroxylase deficiency in infancy and childhood: the effect of time of initiation of therapy on puberty and final height. Eur J Endocrinol. 1997;136(2):188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin KA, Anderson RR, Chang RJ, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hirsutism in premenopausal women: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(4):1233–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bidet M, Bellanne-Chantelot C, Galand-Portier MB, et al. Fertility in women with nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1182–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trakakis E, Dracopoulou-Vabouli M, Dacou-Voutetakis C, Basios G, Chrelias C, Kassanos D. Infertility reversed by glucocorticoids and full-term pregnancy in a couple with previously undiagnosed nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(4):1048–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bornstein SR, Allolio B, Arlt W, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary adrenal insufficiency: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):364–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trapp CM, Oberfield SE. Recommendations for treatment of nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia (NCCAH): an update. Steroids. 2012;77(4):342–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pugeat M, Raverot G, Plotton I. Androgen-ecreting adrenal and ovarian neoplasms. In: Azziz R, Nestler JE, Dewailly D, eds. Androgen Excess Disorders in Women: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Other Disorders. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2007:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brojeni NR, Salehian B. Androgen secreting ovarian tumors. MOJ Womens Health. 2017;5(6):327–330. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Derksen J, Nagesser SK, Meinders AE, Haak HR, van de Velde CJ. Identification of virilizing adrenal tumors in hirsute women. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(15):968–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.LeVee A, Suppogu N, Walsh C, Sacks W, Simon J, Shufelt C. The masquerading, masculinizing tumor: a case report and review of the literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sarfati J, Bachelot A, Coussieu C, Meduri G, Touraine P. Study Group Hyperandrogenism in Postmenopausal W. Impact of clinical, hormonal, radiological, and immunohistochemical studies on the diagnosis of postmenopausal hyperandrogenism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165(5):779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arnaldi G, Martino M. Androgens in Cushing’s syndrome. Front Horm Res. 2019;53:77–91.s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee PA, Nordenstrom A, Houk CP, et al. Global disorders of sex development update since 2006: Perceptions, Approach and Care. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;85(3):158–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rosenfield RL. Hirsutism and the variable response of the pilosebaceous unit to androgen. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10(3):205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reinehr T, Kulle A, Wolters B, et al. Steroid hormone profiles in prepubertal obese children before and after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(6):E1022–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Knudsen KL, Blank SK, Burt Solorzano C, et al. Hyperandrogenemia in obese peripubertal girls: correlates and potential etiological determinants. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(11):2118–2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rosenfield RL, Ehrmann DA. The pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the hypothesis of PCOS as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism revisited. Endocr Rev. 2016;37(5):467–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Varlamov O, Bishop CV, Handu M, et al. Combined androgen excess and Western-style diet accelerates adipose tissue dysfunction in young adult, female nonhuman primates. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(9):1892–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barnes RB, Rosenfield RL, Ehrmann DA, et al. Ovarian hyperandrogynism as a result of congenital adrenal virilizing disorders: evidence for perinatal masculinization of neuroendocrine function in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(5):1328–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rosenfield RL. Clinical review: Identifying children at risk for polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Anderson AD, Solorzano CM, McCartney CR. Childhood obesity and its impact on the development of adolescent PCOS. Semin Reprod Med. 2014;32(3):202–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Torchen LC. Early phenotypes in polycystic ovary syndrome: some answers, more questions. Fertil Steril. 2019;111(2):266–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stener-Victorin E, Padmanabhan V, Walters KA, et al. Animal models to understand the etiology and pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McCartney CR, Campbell RE. Abnormal GnRH pulsatility in polycystic ovary syndrome: recent insights. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2020;12:78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dulka EA, Burger LL, Moenter SM. Ovarian androgens maintain high GnRH neuron firing rate in adult prenatally-androgenized female mice. Endocrinology. 2020;161(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sullivan SD, Moenter SM. Prenatal androgens alter GABAergic drive to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: implications for a common fertility disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(18):7129–7134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Silva MS, Prescott M, Campbell RE. Ontogeny and reversal of brain circuit abnormalities in a preclinical model of PCOS. JCI Insight. 2018;3(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eagleson CA, Gingrich MB, Pastor CL, et al. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: evidence that flutamide restores sensitivity of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator to inhibition by estradiol and progesterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(11):4047–4052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Blank SK, McCartney CR, Chhabra S, et al. Modulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator sensitivity to progesterone inhibition in hyperandrogenic adolescent girls--implications for regulation of pubertal maturation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(7):2360–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Berga SL. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a model of combinatorial endocrinology? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(7):2250–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Matheson E, Bain J. Hirsutism in women. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(3):168–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reinehr T, de Sousa G, Roth CL, Andler W. Androgens before and after weight loss in obese children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(10):5588–5595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.McCartney CR, Prendergast KA, Chhabra S, et al. The association of obesity and hyperandrogenemia during the pubertal transition in girls: obesity as a potential factor in the genesis of postpubertal hyperandrogenism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(5):1714–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lass N, Kleber M, Winkel K, Wunsch R, Reinehr T. Effect of lifestyle intervention on features of polycystic ovarian syndrome, metabolic syndrome, and intima-media thickness in obese adolescent girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(11):3533–3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pena AS, Witchel SF, Hoeger KM, et al. Adolescent polycystic ovary syndrome according to the international evidence-based guideline. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]