Abstract

The increase of antimicrobial resistance constitutes a significant threat to human health. One of the mechanisms responsible for the spread of resistance to antimicrobials is the transfer of plasmids between bacteria by conjugation. This process is mediated by type IV secretion systems (T4SS) and previous studies have provided in vivo evidence for interactions between DNA and components of the T4SS. Here, we purified TraD and TraE, two inner membrane proteins from the Escherichia coli pKM101 T4SS. Using electrophoretic mobility shift assays and fluorescence polarization we showed that the purified proteins both bind single-stranded and double-stranded DNA in the nanomolar affinity range. The previously identified conjugation inhibitor BAR-072 inhibits TraE DNA binding in vitro, providing evidence for its mechanism of action. Site-directed mutagenesis identified conserved amino acids that are required for conjugation that may be targets for the development of more potent conjugation inhibitors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-85446-9.

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Drug discovery, Microbiology, Structural biology

Introduction

Conjugation is a mechanism of horizontal gene transfer between bacteria, and it requires the presence of type IV secretion systems (T4SS)1. These are large nanomachineries that span the entire cell envelope, allowing biogenesis and formation of pili that mediate contact with recipient cells, followed by DNA transfer. T4SS are coded on self-transmissible conjugative plasmids that contain genetic elements for the T4SS machinery (minimal T4SS) and the DNA processing machinery (relaxosome complex).

The minimal T4SS comprises 12 proteins (VirB1 to VirB11 and VirD4), named after the components of the Agrobacterium tumefaciensT4SS2. The outer membrane complex is composed of VirB7, VirB9 and VirB10 and the inner membrane and periplasmic complex is composed of VirB3, VirB5, VirB6 and VirB8. The machinery is powered by three ATPases: VirB4, VirB11 and VirD4 that associate with the inner membrane. A recently published cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure revealed the subatomic architecture of the R388 T4SS3and confirmed interactions between proteins that had previously been shown using various biochemical techniques4–7). The extracellular pili are formed by VirB2 and VirB5 and they also contain phospholipids in their structure8–12. Recent work on the A. tumefaciens and E. coliP-type pilus structure9,10revealed the presence and importance of positive charges in the lumen. This observation raised the question whether DNA is transferred through the pilus. Indeed, recent work provided evidence for this notion using an F-type pilus13,14. There is also indirect evidence for the binding of the translocated DNA to components of the T4SS. Using chemical crosslinking and immunoprecipitation of transferred DNA (TrIP) it was shown that VirB2, VirB6, VirB8, VirB9 and VirB11 may bind DNA, indicating a possible DNA transfer pathway through the A. tumefaciensT4SS15.

Here, we directly tested this hypothesis using purified homologs of VirB6 and VirB8 from the plasmid pKM101 T4SS. In our previous work we showed by negative stain EM and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) that the inner membrane protein VirB8 homolog TraE forms hexameric rings4. DNA may translocate though the 22 Å diameter central pore of this complex. We also solved the crystal structure of TraE, identified the molecular basis of multimerization and described the binding interactions with small molecule inhibitors such as BAR-07216,17. VirB8 interacts with VirB6 that is the most hydrophobic T4SS component4. Due to its hydrophobicity, VirB6 has not been characterized biochemically until now, but according to a long-standing hypothesis in the field it may be part of the DNA transfer pore of the T4SS4,15,18.

We used purified VirB8 and VirB6 homologs TraE and TraD to conduct electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and fluorescence polarization (FP) assays to test DNA binding. Both purified proteins bind single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) in the nanomolar range. We demonstrated that the previously identified T4SS inhibitor BAR-072 inhibits DNA binding to TraE, thus providing insights into its mechanism of action. Finally, we identified conserved amino acids of TraE that are essential for conjugation that may be targets for therapeutic development.

Results

TraE binds to ssDNA and dsDNA

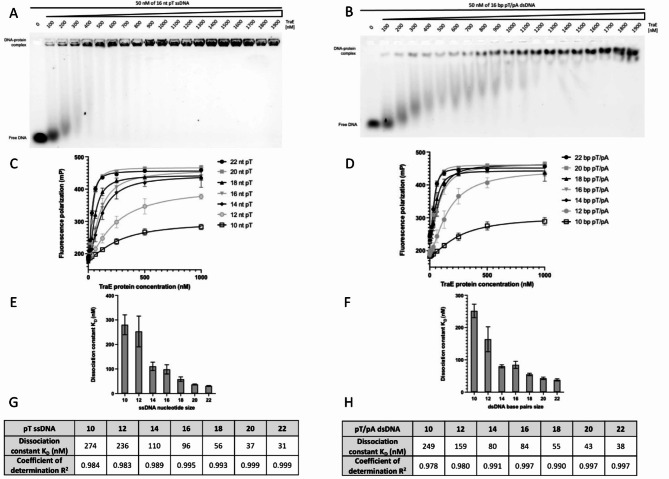

TraE was overexpressed and purified in detergents as previously described4. To assess if TraE can bind to ssDNA, we carried out EMSA experiments by incubating a constant amount of 5’-fluorescein-labelled DNA (the probe) with increasing amounts of TraE prior to gel migration. To maintain the nucleic acid as single-stranded, we used poly-deoxythymidine oligonucleotides (pT) that have a low propensity to form secondary structure that might impact binding. A 16 nucleotide (nt) pT was selected to ensure the DNA is long enough to span the entire 53 Å length of the hexameric ring as measured by SAXS4. We observed slower migration of the 16 nt pT DNA in the presence of TraE in the concentration range of 100–1900 nM (Fig. 1A). This result suggests that TraE binds to ssDNA, as predicted by the results of previous TrIP experiments15. The same experiment was conducted in the presence of dsDNA by annealing the 5’-fluorescein 16 nt pT with 16 nt poly-deoxyadenosine (16 base-pair (bp) pT/pA). Again, we observed slower migration of dsDNA over the same range of TraE concentrations, indicating that TraE also binds dsDNA (Fig. 1B). TraE appears to bind ssDNA with higher affinity than dsDNA based on the range of concentrations that leads to a complete shift of each probe (compare Fig. 1A to Fig. 1B). Finally, the pronounced shift observed in Fig. 1aligns with our previous findings, which demonstrated that purified TraE assembles as a homohexamer4.

Fig. 1.

TraE binds ssDNA and dsDNA. EMSA analysis with 50 nM of 16 nt pT ssDNA (A) and 50 nM of 16 bp pT/pA dsDNA (B) in the presence of TraE gradient from 100–1900 nM. (C) FP mP signal of 10–22 nt pT ssDNA and 10–22 bp pT/pA dsDNA (D) as a function of TraE protein concentration. Representation of the dissociation constant KD as a function of 10–22 length ssDNA (E) or 10–22 length dsDNA (F). Summary of TraE KD and R2 of each pT ssDNA (G) and each pT/pA dsDNA (H). Each experiment was independently repeated three times, and each value represent the mean of those experiments.

Next, an orthogonal FP DNA-binding assay was conducted to corroborate the EMSA results and to quantify TraE affinity for DNA. According to SAXS data, the central pore has a diameter of 22 Å and a length of 53 Å. Therefore, we decided to use a range of DNA oligomers expected to approximate the length of the central pore, ranging from 10 to 22 nt or bp, resulting in theoretical lengths of 34–78 Å. We observed hyperbolic curves for titrations of TraE with ssDNA and dsDNA, which indicated a binding interaction and confirmed our EMSA results. A one-to-one binding model was fit to the data to calculate apparent binding affinities in terms of an equilibrium dissociation constant, KD. The binding affinities are in the nanomolar range, largely following an overall DNA length-dependent binding affinity with longer DNA having higher affinity and thus lower KD values. The longest DNAs used (22 nt/bp) resulted in the highest affinities measured: 31 nM for ssDNA and 38 nM for dsDNA (Fig. 1C–H).

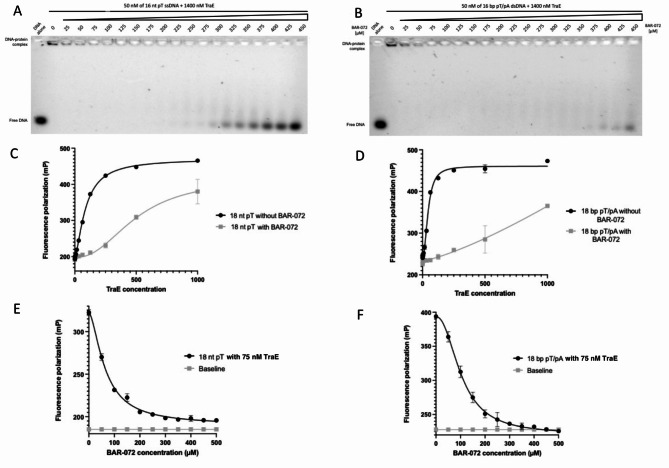

BAR-072 inhibits TraE DNA binding

In our previous study using the periplasmic version of TraE (TraEp)16 we discovered that the small molecule BAR-072 binds to TraEp and inhibits in vivo bacterial conjugation. We tested whether BAR-072 could inhibit TraE interaction with DNA. For EMSA experiments illustrated in Fig. 2A and B, the concentration of TraE was fixed at 1400 nM and then incubated with increasing concentrations of BAR-072. Following incubation and gel migration, we observed more unbound DNA with increasing BAR-072 concentrations, which showed that BAR-072 inhibits TraE-DNA interaction.

Fig. 2.

BAR-072 compound inhibits TraE-DNA binding. EMSA analysis of 1400 nM TraE with 50 nM of 16 nt pT ssDNA (A) and 50 nM of 16 bp pT dsDNA (B) in the presence of BAR-072 gradient ranging from 25–450 µM. FP mP signal of 18 nt pT ssDNA (C) or 18 bp pT dsDNA (D) as a function of TraE gradient concentration in the presence (grey curve) or absence (black curve) of 450 µM BAR-072 compound. (E) FP mP signal of 75 nM TraE incubated with 18 nt pT ssDNA (E) or 18 bp pT dsDNA (F) as a function of BAR-072 gradient (black curve). The baseline (grey line) represents the total fluorescence emission value in the presence of various BAR-072 concentrations. Each experiment was independently repeated three times, and each value represent the mean of those experiments.

The same experiment was conducted using FP in Fig. 2C and D, but now with 18 nt pT ssDNA and 18 bp pT/pA dsDNA, respectively. A control condition without BAR-072 was included (dark curve in Fig. 2E and F). In the presence of BAR-072 (grey curves in Fig. 2E and F), we observed a drop in FP signal that correlated with an increasing amount of the compound. The baseline traces in Fig. 2E and F show that BAR-072 does not emit or influence the total fluorescence, as the FP signal does not change over the concentration range tested. These results indicate that BAR-072 inhibits TraE binding to DNA, and we observe that inhibition has a higher impact on binding to ssDNA than on dsDNA.

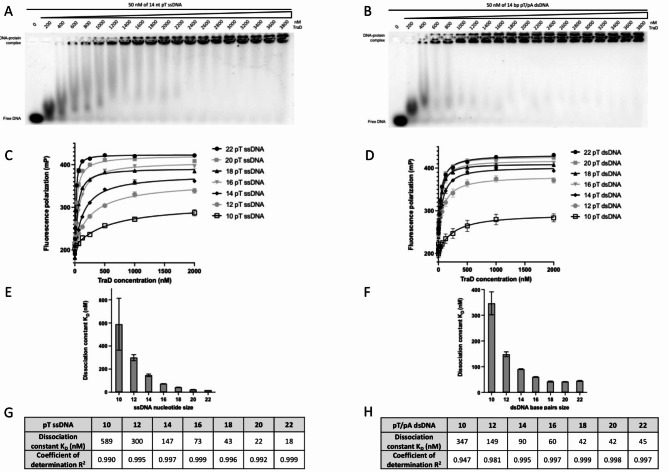

TraD binds to ssDNA and dsDNA

Due to the spatial proximity of TraE and TraD in the T4SS, we investigated whether TraD also binds DNA. TraD was overexpressed and purified in various detergents and among these, Triton X-100 yielded a stable purified protein with a highly homogeneous gel filtration profile (supplementary Fig. 1). As for TraE, an EMSA experiment was first used to evaluate the DNA binding capacity of TraD. In Fig. 3A and B, we observed that TraD retarded DNA migration, indicating its ability to bind both ssDNA and dsDNA, consistent with our prior findings that TraD also multimerizes4. FP experiments were also conducted (Fig. 3C and D) to quantify the binding affinity. These experiments showed a binding affinity in the nanomolar range of TraD for both ssDNA and dsDNA (Fig. 3E–H). Furthermore, as for TraE, TraD has a higher affinity for ssDNA compared to dsDNA for the longest DNA lengths tested.

Fig. 3.

TraD binds ssDNA and dsDNA. EMSA analysis with 50 nM of 14 nt pT ssDNA (A) and 50 nM of 14 bp pT dsDNA (B) in the presence of TraD gradient from 200–3800 nM. FP mP signal of 10–22 nt pT ssDNA (C) and 10–22 bp pT dsDNA (D) as a function of TraD protein concentration. Representation of the dissociation constant KD as a function of 10–22 length ssDNA (E) or 10–22 length dsDNA (F). Summary of TraD KD and R2 of each pT ssDNA (G) and each pT/pA dsDNA (H). Each experiment was independently repeated three times, and each value represent the mean of those experiments.

TraE sequence alignment and mutagenesis

To gain insights into the molecular basis of DNA binding, a multiple sequence alignment of TraE homologs (VirB8 proteins) from different organisms was performed, and several amino acid residues were found to be highly conserved (Fig. 4A). Since TraE binds DNA non-specifically, we created single point mutations of each positively charged and aromatic conserved amino acid by substituting them with alanine. To determine if these 14 single point mutations impact conjugation, we co-expressed the TraE mutants in a donor strain carrying a ΔtraE version of pKM101. We incubated the co-transformed bacterial donor cells overnight with recipient cells and tested the efficiency of complementation by plating on media with selective antibiotics to monitor the transfer of the pKM101 ΔtraE plasmid into the recipients. The efficiency of conjugation was significantly reduced in the case of 13 of 14 TraE mutants (Fig. 4B) and their localization on the X-ray structure of TraE is shown in Fig. 4C. Plasmids carrying mutations W40A, Y106A and Y225A complemented conjugation at strongly reduced levels and no complementation was observed in the case of TraE mutants Y113A, R176A, Y203A and R213A. Western blotting with TraE-specific antisera showed that all mutants were expressed at comparable levels (Fig. 4B), indicating that the mutations do not impact TraE expression. Further work is required to determine if the identified amino acids participate in DNA binding or possibly in another biological role, such as protein-protein interactions.

Fig. 4.

Site-directed mutagenesis on TraE and localization on crystal structure. (A) Amino acids sequence alignment of TraE from pKM101 plasmid with six VirB8 homologs: B. suis (strain 1330, 38% identity), A. tumefaciens (C58 plasmid, 27% identity), E. coli R388 plasmid (42% identity), S. meliloti (SM11 plasmid, 26% identity), B. henselae (ICB.4D7 plasmid, 21% identity), and A. baumannii (Rp428, 35% identity). Strongly positively charged and aromatic amino acids residues are marked in grey. (B) pKM101 conjugation assay to assess the capacity of TraE and its variants to complement a pKM101ΔtraE plasmid. The data represent averages and standard errors of three biological replicate cultures. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences (**** for p < 0.0001, n = 3; *** for p < 0.001, n = 3; ** for p < 0.01, n = 3; ns for non significant, n = 3). Bottom, Western blot using anti-TraE antibody. (C) Crystal structure of TraE dimer (pdb: 5I97) with location of mutation sites. Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with UCSF Chimera (https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimera), developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California., San Francisco, with support from NIH P41-GM103311.

Discussion

Here, we present direct evidence showing that purified TraE and TraD bind DNA. The binding affinities are in the nanomolar range, suggesting that both proteins are part of the transmembrane substrate translocation channel. Considering the biological role of the relaxosome complex13, we expected to observe only ssDNA binding. However, a recent preprint article on the outer membrane protein CagX (VirB9 protein homolog in the Helicobacter pylori T4SS) shows that CagX can bind ssDNA and dsDNA and the dissociation constants are in the micromolar range19. The ability of T4SS-associated proteins to bind DNA at nanomolar affinities might represent an evolutionary adaptation, enabling their functionality in both conjugative and non-conjugative roles. Both ssDNA and dsDNA conjugation systems likely originated from a shared evolutionary pathway, depending on conserved ATPases (such as VirB4, VirD4, and TraB/FtsK) optimized for driving DNA translocation20.

Even if our data demonstrate that TraE and TraD both bind dsDNA, we would have expected a larger difference between the binding affinities for the same size oligonucleotide. Yet, the KDvalues for ssDNA and dsDNA are quite similar with minor variations observed for oligonucleotides of different lengths. Since TraE and TraD are closely juxtaposed in the T4SS3and were shown to interact4,15,18it would be interesting to test for synergy in the future and to assess whether DNA binding affects the conformation of these proteins. The study on TraI relaxase, which shows both high affinity for ssDNA and its ability to adopt distinct conformational states, provides a useful parallel21. TraI transitions between a closed conformation, which stabilizes DNA binding, and an open conformation associated with substrate processing. By analogy, we hypothesize that TraE and TraD may adopt distinct conformations during the DNA translocation process. In cooperation with ATPases, TraE and TraD could bind and stabilize the DNA substrate at the channel entrance, which would explain their high affinity. Once the DNA substrate is bound and processed, the ATPases likely energize the translocation of the ssDNA intermediate through the TraE/D channel. Upon interacting with other T4SS components, the affinity of TraE and TraD might decrease, thereby facilitating the progression of the translocation process.

Whereas we described a hexameric TraE by SEC-MALS and negative stain EM4, the recently published structure of R388 T4SS shows the presence of 24-mer TrwG (VirB8), the homolog of TraE22. However, our work on TraE and TraD was done on the isolated proteins and previous studies show the presence of VirB8 at the cell poles in A. tumefaciensand its importance for the recruitment of T4SS components15,23. We conclude that VirB6 and VirB8 may form intermediate oligomeric states during the assembly of the inner membrane T4SS complex. Hexameric TraE may represent an early state in the formation of higher molecular weight complexes in the mature T4SS. Indeed, a similar phenomenon was observed for VirB4, which forms dimers as well as hexamers24–26.

We have previously shown that the periplasmic domain of TraE forms a dimer disrupted by the conjugation inhibitor BAR-07216, which also blocks TraE multimerization and impairs bacterial conjugation. Here, we demonstrate that at a given concentration, BAR-072 completely shifts the DNA substrate from the gel well to the unbound form, suggesting either that the monomeric form of TraE cannot bind DNA or that the inhibitor directly blocks TraE (whether as multimers or monomers) from binding DNA. Interestingly, BAR-072 interacts with R110, a conserved amino acid that was mutated for the conjugative assay (Fig. 4B). However, the R110A mutation did not significantly impact conjugation, indicating that multiple mutations would be required to mimic the effect of BAR-072.

Sequence similarities between different VirB8 homologs are generally low and range from 20 to 40%, but their overall structures are highly conserved suggesting evolutionary pressure to conserve protein folding27–31). Indeed, mixing purified VirB8 homologs resulted in heterodimers, which is consistent with the close structural similarity among homologs16. We performed site-directed mutagenesis of 14 highly conserved positively charged and aromatic amino acids that may be involved in DNA binding. The locations of these residues on the TraE crystal structure are represented in Fig. 4C. Most mutations are in the NTF2 (nuclear transport factor 2) domain, which is known to be present in proteins with disparate functions, such as small molecule binding and enzymatic activities32–34). According to the sequence alignment in Fig. 4A, conserved residues R176 and R226 (TraE numbering) correspond to B. suis residues R179 (R179bs) and R230 (R230bs), respectively. It was previously shown that R179bsinteracts with VirB1035 and mutating R230bs inhibits interaction with VirB4 and also strongly reduces B. suisintracellular growth36. Our observation of decreased and ablated conjugation with TraE R226A and R176A mutants, respectively, (Fig. 4B) could be explained by breaking similar contacts between components of the pKM101 T4SS.

Bacterial two-hybrid experiments with B. suisVirB8 mutants showed that many impact dimer formation37. This is the case for Y110bs, Y206bs and Y229bs that correspond to TraE residues Y106, Y203 and Y225, respectively. Expression of the Y106A and Y225A TraE mutants led to strongly reduced conjugation, while the Y203A mutant did not complement at all. These mutations likely reduced TraE multimerization, thereby impacting bacterial conjugation. Finally, the VirB8 residue W198bswas involved in binding to an inhibitor that impacts dimerization without inducing detectable conformational changes36. In our study, the corresponding TraE mutant W195A resulted in a 50% loss of conjugation activity (Fig. 4B).

This work confirms the importance of conserved residues among VirB8 homologs, especially residues in the NTF2-like domain that are involved in protein-protein interactions. These amino acids are potential targets for the development of small-molecule inhibitors of T4SS. Since all mutants expressed at wild type levels (Fig. 4B), it would be interesting to purify the mutants to assess whether the TraE mutations impact multimerization and/or DNA binding by gel filtration and FP, respectively. Future research will aim to determine full-length protein structures in the presence of DNA to identify the amino acid residues that are directly implicated in DNA binding.

Materials and methods

Strains, plasmids and DNA manipulation

The strains and plasmids used are described in Table 1. Briefly, the E. coli strain XL-1 blue was used as a host for cloning, and BL21(λDE3) pLEMO was used for TraE and TraD overexpression. The Monarch Plasmid Miniprep kit (NEB) was used to isolate DNA plasmids. All mutations were performed using the QuickChange protocol and the oligonucleotides shown in supplementary Table 1. The mutations were verified by automated Sanger DNA sequencing.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

| Genotype/Description | Source/Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| XL1 Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F´ proAB lacIqZ∆M15 Tn10 (TetR)] | Agilent Technologies |

| BL21(DE3) | E. coli B F–ompT gal [E. coli B is naturally dcm and lon] hsdSB with DE3, a λ prophage carrying the T7 RNA polymerase gene and lacIQ | Sigma-Aldrich |

| MG1655 | ilvG rpb-50 rph-1 DlacU169 | E. coli Genetic Stock Center |

| WL400 | CamR StrepRaraD139 Δ (argF-lac)U169, ptsF25 deoC1 relA1 flbB5301 rpsL150 ΔselD204::cat, conjugation recipient | W. Leinfelder, unpublished data |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLEMO | pACYC184-PrhaBAD-lysY (CamR) | 40 |

| pHT | KanR; pET24d derivative T7 expression vector with N-terminal 6xHis-tag and TEV protease cleavage site | 16 |

| pHT TraE | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE | 16 |

| pKM101ΔTraE | SpecR; pKM101 containing a deletion of the traE locus | Jay E. Gordon & Peter J. Christie, unpublished data |

| pHT TraE R37A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change R37A | This work |

| pHT TraE W40A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change W40A | This work |

| pHT TraE Y106A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change Y106A | This work |

| pHT TraE R110A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change R110A | This work |

| pHT TraE Y113A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change Y113A | This work |

| pHT TraE R176A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change R176A | This work |

| pHT TraE F177A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change F177A | This work |

| pHT TraE W195A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change W195A | This work |

| pHT TraE Y201A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change Y201A | This work |

| pHT TraE Y203A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change Y203A | This work |

| pHT TraE R213A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change R213A | This work |

| pHT TraE F220A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change F220A | This work |

| pHT TraE Y225A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change Y225A | This work |

| pHT TraE R226A | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraE with amino change R226A | This work |

| pHT TraD | KanR; T7 promoter vector for the expression of 6xHis-tagged full-length domain of pKM101 TraD | 16 |

| pMSP1D1 | KanR; pET28a derivate containing mutant (1–11) of MSP1; His-tag on N-terminus followed by spacer sequence and TEV protease site |

Addgene #20,061 |

| pMSP1E3D1 | KanR; pET28a derivate containing extended MSP1D1; contains repeats of helices 4, 5 and 6; N-terminal 7-his tag followed by spacer sequence and TEV protease cleavage site |

Addgene #20,066 |

| pMSP2N2 | KanR; pET28a derivate containing tandem MSP; His-tag on N-terminus followed by spacer sequence and TEV protease site |

Addgene #29,520 |

pMSP1D1, pMSP1E3D1 and pMSP2N2 was a gift from Stephen Sligar (Addgene plasmid #20061, #20066 and #29520, respectively).

Small-scale TraE and TraD protein expression optimization

TraE and TraD overproduction optimization were performed based on the protocol extensively described by Wang et al.38,. Briefly, for screening overexpression, the E. coli strains BL21(λDE3), BL21 Star(λDE3), C41(λDE3) or C43(λDE3) carrying expression plasmids pHTTraE and pHTTraD were grown under aerobic conditions at 37 °C (co-transformed or not with pLEMO plasmid) in 10 mL LB, 2YT or TB media cultures to exponential phase (OD600 0.6–0.8). The expression was induced by the addition of 0, 0.1–1.0 mM IPTG (with 0.1 mM increments); at temperatures of 18 °C, 25 °C, 30–37 °C and cultures were left shaking for 4, 6, 8–18 h at 220 rpm. Cells were collected in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes, the DO600was normalized to 1.0 and centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 10 min. Pellets were kept at −20 °C until further use. Bacterial lysis was performed using the method described by Casu et al.4,. Dot Blot was performed by pipetting and depositing 3 µL of the bacterial lysis supernatant on nitrocellulose membrane and leaving to air dry for 10 min. Blocking and further procedures were the same as for the Western Blot using an anti-His-Tag antibody (1:5000 dilution). Five of the most intense culture conditions visualized by Dot Blot were loaded on SDS-PAGE followed by Western Blot to ensure the protein migrated at the correct molecular weight. For pHTTraE, the best overexpression condition corresponded to the BL21(λDE3) pLEMO induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 30 °C for 6 h in LB media, while for pHTTraD, the best overexpression condition corresponded to BL21(λDE3) pLEMO induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 18 °C for 18 h in TB media.

TraD solubilization tests and purification

Five different detergents (Pluronic F-127, Tergitol NP-40, Triton X-100, DDM, OGNG and LMNG) were used to assess TraD extraction and stabilization. Briefly, bacterial cultures were resuspended at 4 °C in Buffer A (50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 100 mM imidazole) with cOmplete Mini protease Inhibitor mixture and DNase I at 100 µg/mL and lysed twice using One Shot cell disruptor (Constant Systems, Inc) at 27 kpsi and 4 °C. Ultracentrifugation at 250,000 x g for 1 h at 4 °C was performed, and pellets were collected and solubilized overnight at 4 °C in Buffer A supplemented with 20x CMC of the detergent. Debris were removed by centrifugation at 34,000 x g for 30 min at 4 °C. A fraction of the solution was used for Western Blot analysis to assess the quantity of extracted and solubilized TraD, and the rest was loaded on HisTrap Ni-chelate column (GE Healthcare). After extensive washing in Buffer B (Buffer A plus 3x detergent CMC), the protein was eluted into fractions using Buffer C (50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 100 mM arginine, 100 mM glutamate, 10% glycerol, 1 M imidazole and 2x detergent CMC). The fraction with the highest concentration was injected into a Superose 6 10/300 column equilibrated with 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM arginine, 50 mM glutamate, 50 mM imidazole, and 2x detergent CMC.

TraE purification in OGNG detergent

TraE was purified as described by Casu et al.4,.

Protein molarity quantification and visualization

All protein molar quantifications were based on the hexameric form of TraE and the pentameric form of TraD (as described in3). SDS-PAGE gels were visualized with zinc imidazole39.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay for TraE and TraD

The EMSA was conducted using 50 nM of 5’ 6-Fluorescein (5’ 6-FAM) pT labelled DNA (hybridized or not with the complementary non-fluorescent DNA strain to form ssDNA and dsDNA) from IDT. LMNG was used as a detergent for TraE, while Triton X-100 was used for TraD. Proteins were diluted in 10 mM Tris pH 9.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5x detergent CMC and incubated with DNA for 30 min at 4 °C. Samples were loaded on a 0.5% agarose gel and run in the running buffer: 0.5X Tris-Borate-EDTA (TBE) pH 9.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 5x detergent CMC at 90 V, 4 °C for 2 h. Agarose gels were prepared by solubilizing agarose with the running buffer, and gel revelation was acquired using a Fluorescein filter from the ChemiDoc MP imaging system. For BAR-072 inhibition experiments, all solutions and gels were supplemented with 10% DMSO.

Fluorescence polarization of TraE and TraD

As for EMSA experiments, 5’ 6-FAM was used but at 10 nM concentration and all fluorescence polarization experiments were performed at least three times. Protein-DNA binding was performed in FP Buffer: 10 mM sodium phosphate (NaPi) pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 5x detergent CMC (LMNG for TraE and Triton X-100 for TraD). The probe was incubated with the indicated protein concentration, and measurement was made at room temperature on a Victor3Vplate reader (PerkinElmer). For binding and inhibition, curves were fit with saturation binding, specific binding with Hill slope equations.

For inhibition experiments, 10% DMSO was supplemented with the FP buffer.

Conjugative DNA transfer and Western blot

For conjugative assays, pHT plasmids (kanamycin-resistant) and MG1655 pKM101ΔtraE (donor, spectinomycin-resistant) were used with WL400 cells (recipient cell, chloramphenicol-resistant). E. coli strains MG1655 containing pKM101ΔtraE were transformed with the complementation vector pHT (negative control), pHTTraE (positive control), or pHTTraE expressing TraE variants. The same protocol described by Casu et al.16, was used, except the recipient cell was grown in liquid LB media containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin and 100 µg/mL spectinomycin, and the agar plates for conjugation transfer quantification contained kanamycin and chloramphenicol antibiotics. The bacterial conjugation experiments were performed three times, and a Student’s t-test was conducted.

For the Western Blot, MG1655 pKM101ΔtraEtransformed with pHT, pHTTraE and pHTTraE variants were grown on LB agar plates (with 100 µg/mL spectinomycin and 50 µg/mL kanamycin) at 30 °C overnight. Cells were pelleted, and bacterial lysis was performed4. 50 µL of sample was loaded on SDS-PAGE gel and anti-TraE antibody was used (1:5000 dilution).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research grants #274108 and #469471 to (C.B.). pKM101ΔtraE plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Peter J. Christie (University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston). We thank Antonio Nanci (University of Montreal) and the FEMR staff (McGill University) for advice on single-particle EM analysis.

Author contributions

Z.J. - designed and conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared the figures and wrote the main manuscript textA.S - designed experiments, analyzed data and revised the manuscript J.S. - designed experiments, analyzed data and revised the manuscript J.P. - designed experiments, analyzed data and revised the manuscript C.B. - designed experiments, revised the manuscript, oversaw the work and obtained funding.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cabezon, E. et al. Towards an integrated model of bacterial conjugation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.39 (1), 81–95 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa, T. R. D. et al. Type IV secretion systems: advances in structure, function, and activation. Mol. Microbiol.115 (3), 436–452 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mace, K. et al. Cryo-EM structure of a type IV secretion system. Nature607 (7917), 191–196 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casu, B. et al. VirB8 homolog TraE from plasmid pKM101 forms a hexameric ring structure and interacts with the VirB6 homolog TraD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115 (23), 5950–5955 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mary, C. et al. Interaction via the N terminus of the type IV secretion system (T4SS) protein VirB6 with VirB10 is required for VirB2 and VirB5 incorporation into T-pili and for T4SS function. J. Biol. Chem.293 (35), 13415–13426 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villamil Giraldo, A. M. et al. VirB6 and VirB10 from the Brucella type IV secretion system interact via the N-terminal periplasmic domain of VirB6. FEBS Lett.589 (15), 1883–1889 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward, D. V. et al. Peptide linkage mapping of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens vir-encoded type IV secretion system reveals protein subassemblies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 99 (17), 11493–11500 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa, T. R. D. et al. Structure of the bacterial sex F Pilus reveals an assembly of a stoichiometric protein-phospholipid complex. Cell166 (6), 1436–1444e10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amro, J. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-pilus reveals the importance of positive charges in the lumen. Structure31 (4), 375–384 (2023). e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreida, S. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens T4SS-associated T-pilus reveals stoichiometric protein-phospholipid assembly. Structure31 (4), 385–394 (2023). e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng, W. et al. Cryoelectron-Microscopic structure of the pKpQIL conjugative pili from Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Structure28 (12), 1321–1328 (2020). e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vadakkepat, A. K. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the R388 plasmid conjugative pilus reveals a helical polymer characterised by an unusual pilin/phospholipid binary complex. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Couturier, A. et al. Real-time visualisation of the intracellular dynamics of conjugative plasmid transfer. Nat. Commun.14 (1), 294 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldlust, K. et al. The F pilus serves as a conduit for the DNA during conjugation between physically distant bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 120 (47), e2310842120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cascales, E. & Christie, P. J. Definition of a bacterial type IV secretion pathway for a DNA substrate. Science304 (5674), 1170–1173 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casu, B. et al. Structural analysis and inhibition of TraE from the pKM101 type IV Secretion System. J. Biol. Chem.291 (45), 23817–23829 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casu, B. et al. Fragment-based screening identifies novel targets for inhibitors of conjugative transfer of antimicrobial resistance by plasmid pKM101. Sci. Rep.7 (1), 14907 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakubowski, S. J. et al. Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB6 domains direct the ordered export of a DNA substrate through a type IV secretion system. J. Mol. Biol.341 (4), 961–977 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan, M. E. et al. Architectural asymmetry enables DNA transport through the Helicobacter pylori cag type IV secretion system. bioRxiv, (2023).

- 20.Guglielmini, J., de la Cruz, F. & Rocha, E. P. Evolution of conjugation and type IV secretion systems. Mol. Biol. Evol.30 (2), 315–331 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ilangovan, A. et al. Cryo-EM structure of a relaxase reveals the molecular basis of DNA unwinding during bacterial conjugation. Cell169 (4), 708–721e12 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costa, T. R. D. et al. Structural and functional diversity of type IV secretion systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.22 (3), 170–185 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Judd, P. K., Kumar, R. B. & Das, A. Spatial location and requirements for the assembly of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens type IV secretion apparatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102 (32), 11498–11503 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Middleton, R. et al. Predicted hexameric structure of the Agrobacterium VirB4 C terminus suggests VirB4 acts as a docking site during type IV secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102 (5), 1685–1690 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pena, A. et al. The hexameric structure of a conjugative VirB4 protein ATPase provides new insights for a functional and phylogenetic relationship with DNA translocases. J. Biol. Chem.287 (47), 39925–39932 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallden, K. et al. Structure of the VirB4 ATPase, alone and bound to the core complex of a type IV secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 109 (28), 11348–11353 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terradot, L. et al. Structures of two core subunits of the bacterial type IV secretion system, VirB8 from Brucella suis and ComB10 from Helicobacter pylori.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102 (12), 4596–4601 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey, S. et al. Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB8 structure reveals potential protein-protein interaction sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 103 (8), 2582–2587 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goessweiner-Mohr, N. et al. The 2.5 a structure of the Enterococcus conjugation protein TraM resembles VirB8 type IV secretion proteins. J. Biol. Chem.288 (3), 2018–2028 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter, C. J. et al. The conjugation protein TcpC from Clostridium perfringens is structurally related to the type IV secretion system protein VirB8 from Gram-negative bacteria. Mol. Microbiol.83 (2), 275–288 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuroda, T. et al. Molecular and structural analysis of Legionella DotI gives insights into an inner membrane complex essential for type IV secretion. Sci. Rep.5, 10912 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin, C. S. et al. Peptidoglycan binding by a pocket on the accessory NTF2-domain of Pgp2 directs helical cell shape of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Biol. Chem.296, 100528 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katahira, J. et al. NTF2-like domain of tap plays a critical role in cargo mRNA recognition and export. Nucleic Acids Res.43 (3), 1894–1904 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vukovic, L. D. et al. Nuclear size is sensitive to NTF2 protein levels in a manner dependent on ran binding. J. Cell. Sci.129 (6), 1115–1127 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharifahmadian, M. et al. The type IV secretion system core component VirB8 interacts via the beta1-strand with VirB10. FEBS Lett.591 (16), 2491–2500 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paschos, A. et al. Dimerization and interactions of Brucella suis VirB8 with VirB4 and VirB10 are required for its biological activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 103 (19), 7252–7257 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith, M. A. et al. Identification of the binding site of Brucella VirB8 interaction inhibitors. Chem. Biol.19 (8), 1041–1048 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, X. et al. Study of two G-protein coupled receptor variants of human trace amine-associated receptor 5. Sci. Rep.1, 102 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castellanos-Serra, L. & Hardy, E. Negative detection of biomolecules separated in polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels. Nat. Protoc.1 (3), 1544–1551 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner, S. et al. Tuning Escherichia coli for membrane protein overexpression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 105 (38), 14371–14376 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.