Abstract

Industrial waste significantly impacts water and soil quality, restricting their suitability for agricultural and domestic use. This study investigates the distribution of heavy metals (HMs) in groundwater and soils across the Shazand plain under different irrigation methods and rainfed farming systems. It evaluates the Total Hazard Quotient (THQ) and Carcinogenic Risk (TCR) associated with HMs for both children and adults, considering exposure through ingestion, dermal contact, and inhalation. A total of 104 samples were collected, comprising water samples from wells and boreholes, and soil samples. Concentrations of Pb, Cd, Cr, Ni, Hg, Zn, and Cu were analyzed using atomic absorption spectrometry, and the data were assessed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The highest average concentrations of HMs in groundwater samples were observed for Cr (19 µg l−1) and Zn (22.8 µg l−1). In soil samples, Cr (35.28 µg g−1) and Zn (216.52 µg g−1) exhibited the highest values. The Total Hazard Index (HI) indicated a high risk across different age groups, ranging from moderate to very high in the study areas. The Soil Pollution Load Index (PLI) was 18.22 in rainfed farming and 71.17 in irrigated farming, indicating severe HM contamination across the site. Carcinogenic health risks from HMs exceeded acceptable levels, with children showing greater vulnerability compared to adults. This research underscores the urgent need for effective environmental management strategies to mitigate HM contamination, safeguard public health, and ensure sustainable agricultural practices in industrialized regions.

Keywords: Carcinogenic risk assessment, Groundwater quality, Heavy metals contamination, Industrial impact, Soil pollution

Subject terms: Ecology, Environmental sciences, Health care, Risk factors

Introduction

Heavy metals (HMs) have been identified as significant groundwater contaminants. Rapid economic development and industrialization, particularly in developing countries, have led to elevated levels of HMs in soil, surface water, and groundwater1–4. Consequently, HMs from both anthropogenic and natural sources accumulate in soil and plants, causing substantial environmental pollution. These metals can enter water bodies through various human activities, such as mining, smelting, agriculture, vehicle emissions, improper waste disposal, burning fossil fuels, fertilizer and pesticide application, irrigation with untreated wastewater, and atmospheric deposition. This contamination impacts vegetation, the food chain, and water quality, ultimately affecting human health5–11. While excessive HMs can harm plants, animals, and humans, trace amounts are essential for the growth of living organisms12,13.

Many industrial activities contribute to groundwater pollution through discharges into uncovered channels or groundwater systems, which then percolate into shallow depressions. Groundwater pollution is particularly concerning because it often represents the purest and only safe source of drinking water for local communities without any treatment. Consumption of contaminated water poses serious health risks. The detrimental effects of groundwater pollution are primarily due to specific contaminants present in the water14–17. Soil contaminated with HMs affects entire ecosystems when these toxic metals migrate to groundwater or flora and fauna, posing severe threats through translocation and bioaccumulation18–21. Metal concentrations in soil vary significantly across different geographical locations22,23. Analyzing soil profiles can provide insights into the physical and chemical processes occurring at specific sites24.

Previous research has largely focused on the spatiotemporal fluctuations and contamination of HMs in areas impacted by human activity, such as mining regions, polluted farmlands, and irrigation areas using sewage25–27. However, most studies on HMs characteristics in soil profiles have concentrated on specific land uses. Identifying the sources of HMs contamination is crucial for preventing environmental pollution and protecting public health. Health risk assessments, based on exposure methods provided by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA)28, are fundamental for evaluating the potential health impacts of contaminants found in soil, water, and air. These assessments estimate the total exposure to HMs among residents in a particular area, distinguishing between carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic effects2,29–32.

Numerous studies have considered HMs in both soil and crops, but few have examined their interrelationships. For example33, assessed potential ecological and human health risks posed by soil HMs without considering vegetables or their relationships34. evaluated health risks from HMs in soil and wheat but did not consider their interactions. Complex interactive relationships, including synergistic and antagonistic effects, exist among HMs. For instance, Cu and Zn have a synergistic effect on the absorption of Pb and Cd in wheat while showing an antagonistic effect on As absorption. In maize, Ni in soil inhibits Cu and Cd absorption in roots, whereas Cu and Ni in soil promote Cu and Pb absorption in stems and leaves, and Cr and Pb in soil enhance Mn enrichment in grains35. Despite some attempts to explore these interactions, most studies have focused on specific HM combinations in given crops and have been dominated by field experiments, lacking regional-scale analyses. In practice, multiple HMs coexist in soil and necessarily interact during crop absorption34,36,37. Therefore, the relationships among multiple typical HMs in soil-crop systems at a regional scale have not been fully explored. Another study conducted in Pakistan showed that UCP soils were contaminated with PTEs, which could pose a potential health risk to the local population in UCP areas38. Also, another study was conducted in Pakistan regarding the evaluation of the drinking water quality of government, government, and self-funded projects in disaster-affected areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa39.

Many cities worldwide suffer from HM pollution, often classified as megacities. However, some smaller cities also face significant pollution levels. Arak, a city in central Iran with over 3,000 small and major industries and a population of less than one million, is one such example. Known as one of Iran’s main industrial hubs, Arak hosts numerous factories, including petrochemical, aluminum facility, gasoline refinery, Power plant, and other industrial and production companies. It is also one of the most polluted cities in Iran regarding air quality, highlighting the importance of preserving these agroecosystems. In recent decades, assessing public risk factors has become crucial, as pollutant levels alone do not fully capture the actual risks to human health. The serious consequences of HM contamination necessitate evaluating potential risks posed by chemical pollutants in food from agroecosystems. This research aims to gather data and evaluate the contamination of metals (N, P, K, Zn, Cu, As, Cr, Ni, Pb, Cd, and Hg) known for their high health risk potential due to bioaccumulation in barley, in 104 farms, surface water, and groundwater of the Shahzand Plain. HM contamination in soil and groundwater represents a serious threat to public health, particularly in regions impacted by industrial activities. Despite the recognized risks, there is a lack of comprehensive research addressing the long-term exposure and safety of populations residing in proximity to contaminated areas, especially vulnerable groups such as children. This study aims to address this gap by conducting a thorough assessment of HM contamination, focusing on exposure pathways and the associated health risks. The central hypothesis of this research is that industrial activities lead to elevated concentrations of HMs in the environment, thereby increasing ecological and health risks for surrounding communities. The novelty of the study lies in its integrative approach, which combines the analysis of HM concentrations in both soil and groundwater with a detailed assessment of carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks—a dimension that has been insufficiently explored in this region. While previous studies have examined HM contamination, few have conducted a comparative analysis of soil and groundwater contamination in conjunction with an assessment of public health risks. This study contributes to the existing literature by not only quantifying contamination levels but also identifying high-risk areas, thereby offering valuable insights for the development of effective monitoring and mitigation strategies. The primary objectives of this research are: (1) to investigate and compare the concentrations of selected HMs in soil and groundwater, (2) to assess the extent of HM contamination and its spatial distribution, (3) to identify critical contamination hotspots, and (4) to evaluate the total carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks posed by HMs through various exposure pathways, including ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact, for both adults and children. This study is expected to provide crucial scientific support for environmental management practices and to inform public health policies in alignment with the standards of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Materials and methods

Study area and sample collection

Shahzand Plain, located at 33°57’ North in the southwest of the Markazi Province in Iran, faces several environmental challenges. This picturesque region struggles with agricultural waste, including fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, primarily originating from surrounding agricultural fields and three major contaminated industries (petroleum, power plant, and gasoline refinery). Additionally, pollution is exacerbated by ten surface water sources and industrial wastewater discharges from approximately thirty key factories. Spanning an extensive area of 984 km², Shahzand Plain is one of the main agricultural regions and natural habitats for wildlife in central Iran. This ecosystem serves as a crucial breeding ground for various flora and fauna species and provides refuge for both local and migratory organisms. Currently, Shahzand Plain faces a severe threat from the accumulation of various heavy and transition metals, posing a grave danger to its delicate ecosystem40 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the Shazand Plain.

Sampling of soil and crop

Surface soil samples (0–30 cm) and corresponding barley crops were collected from 102 agricultural sites in November 2023 to investigate HM pollution (Fig. 1). At each site, a composite soil sample was created from five individual samples taken within a one square kilometer plot (four samples from the corners and one from the center, each weighing one kilogram). Preliminary investigations were conducted at each farm when the barley crops were ready for harvest, and 500 g of edible parts from both the straw and seed were collected.

In the laboratory, soil samples were cleaned of debris, air-dried at room temperature, and sieved through a two-millimeter mesh. The barley seeds were weighed and dried at 28°C in a drying oven. All dried samples were sealed and stored in high-pressure polyethylene (HPPE) bags at room temperature until analysis, which was conducted within 30 days.

Soil particle size was classified into three categories: sand (2–0.02 mm), silt (0.02–0.002 mm), and clay (< 0.002 mm). The granulometric fractions were determined using a sieve shaker. Soil pH was measured using a pH electrode (Model PB-10, Sartorius, Gottingen, Germany) in a 1:2.5 soil-to-distilled water ratio. Soil organic matter (OM) content was analyzed using the residual titration of K2Cr2O741. The total nitrogen concentration (TNC) of the soil samples was measured using an elemental analyzer (vario EL III, Elementar, Germany).

The pH of the soils ranged from 7.76 to 7.83, indicating neutral to slightly alkaline conditions, which are generally suitable for most crops, although specific crops may have unique pH requirements for optimal growth. Electrical conductivity (EC) was measured to assess soil salinity. Higher EC values in irrigated soils suggest potential salinity buildup due to irrigation practices. Silt loam irrigated soils exhibited the highest EC, which could impact crop yields if salinity becomes excessive42–44. OM content was relatively low across all samples, with slight variations. Loam sand rainfed soils had the highest OM, beneficial for soil structure, nutrient availability, and water retention. Nitrogen levels, crucial for crop growth, were highest in loam sand rainfed soils, supporting robust vegetative growth45. Conversely, silt loam rainfed soils had the lowest nitrogen levels, which might limit crop growth unless supplemented (Fig. 2). Overall, while the soils appear generally suitable for farming, careful management of irrigation practices and soil amendments is necessary to maintain soil health and optimize crop yields. Regular monitoring of soil properties, along with appropriate fertilization and irrigation strategies, can help mitigate potential issues such as salinity buildup and nutrient deficiencies46,47.

Fig. 2.

Situation of pH, EC, OM, and N concentration in different soil textures of the Shazand Plain.

A total of 102 water samples were gathered from various sources within the study area, including surface water, springs, and wells. These samples were collected using polyethylene bottles. Initially, the bottles were filled with water, emptied, and then refilled with fresh samples to eliminate any air present48. To prevent microbial growth, all water samples were acidified with 5% HNO3. Subsequently, the samples were stored in a cool, dark environment before being transported to the laboratory for further analysis. Standard methodologies were employed to assess physicochemical parameters, including total dissolved solids (TDS), pH, electrical conductivity (EC), temperature, and nitrate (NO3), following the procedures outlined by48. Additionally, the taste, odor, color, and turbidity of the samples were evaluated on-site and compared against the standard limits established by49 and 50.

Also, total phosphorus (TP) and total potassium (TK) were determined using a continuous flow analyzer (Bran and Luebbe Autoanalyer, SPX, Charlotte, NC, USA). The soil and crop samples were digested using HNO3–H2SO4–HClO4; then, the Zn, Cu, Cr, Ni, Pb and Cd contents were investigated by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES 3410 ARL). Another soil and crop samples were digested with aqua regia (HNO3: HCl = 1:3) and determined Hg and as by atomic fluorescence spectrometry (AFS). The accuracy of determinations was verified by the different standardized parameter as reference material (Table 1).

Table 1.

Background values (Bv), toxicity response factor (Tir).

| Reference parameter | Hg | Cr | Ni | Pb | Zn | Cu | Cd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bv (mg kg−1 ) | 0.08a | 17c | 75b | 15a | 60a | 30a | 0.20b |

| Tir | 40a | 2d | 5b | 5a | 1a | 5a | 30b |

| MAC (mg kg−1) | 0.5–5 | 75–100 | 100 | 200–300 | 100–300 | 60–150 | 3–8 |

|

Organization Iran’s environment |

7 | 110 | 110 | 75 | 500 | 200 | 5 |

Contamination factor (Cf)

The Cfwas utilized to assess the enrichment of the individual HMs in the soils. It was to begin with utilized by53 to evaluate the levels of heavy metal in sediments in connection to their background values. The Cf was determined for each metal using Eq. (1). Cn (mg kg−1) is the concentration of HMs in the soil sample and Bv (mg kg−1) is the geochemical background value of HMs in the average Earth’s crust (Table 1). The various classifications of the Cfproposed by53 have been shown in Table 2..

Table 2.

Pollution indices and their classifications.

| Cfa | Cdega | PLIb | PERIa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Pollution intensity | Range | Pollution intensity | Range | Pollution intensity | Range | Pollution intensity |

| Cf < 1 | Low contamination | Cdeg < 8 | Low degree of contamination | PLI < 1 | No pollution | RI < 150 | Low |

| 1 ≤ Cf < 3 | Moderate contamination | 8 ≤ Cdeg <16 | Moderate degree of contamination | 1 < PLI < 2 | Moderate pollution | 150 ≤ RI < 300 | Medium |

| 3 ≤ Cf < 6 | Considerable contamination | 16 ≤ Cdeg <32 | Considerable degree of contamination | 2 < PLI < 3 | Heavy pollution | 300 ≤ RI < 600 | significant |

| Cf ≥ 6 | Very high contamination | Cdeg ≥ 32 | Very high degree of contamination | 3 < PLI | Extremely heavy pollution | RI ≥ 600 | Much |

|

1 |

Degree of contamination (Cdeg)

The Cdegwas used to determine the level of pollution at an articular zone of a site53. It was determined by summing the contamination factors of all the HMs as shown in Eq. (2), where n is the number of analyzed HMs (seven in this study). The various classes of the Cdeg, as suggested by53, have been presented in Table 2.

|

2 |

Pollution load index (PLI)

PLI was utilized to assess the level of soil contamination for the whole location. It was decided utilizing Eq. (3) where n is the number of HMs considered. Table 2.indicate the contamination levels based on the PLI55.

|

3 |

Ecological risk

The Potential ecological risk index (PERI) was used to assess the ecological risk of HMs in the soils. It was presented by53, and can be determined utilizing the taking after equation:

|

4 |

Cf is the contamination factor; n is the number of HMs; Eir and Tir are the potential ecological risk factor and the toxicity response factor (Table 1), respectively, for a given HMs. The interpretation of Eir and PERI values are shown in Table 2..

Geoaccumulation index

This index was first proposed by56and is widely used to measure the degree of heavy metal pollution in the soil56. The pollutant extent of HMs in soil is measured using the geoaccumulation index (Igeo). A higher value of Igeo indicates more severe impurity in the studied a region. The geoaccumulation indicator is an instrument for estimating the position of hindrance from human activity to soil contamination and compensating for environmental background value oscillations of metal concentrations. Igeo is computed according to Eq. 5.

|

5 |

Where Cn represents the concentration of metals in soils of the studied region (mg kg−1); Bv represents the background content of metal (mg kg−1). To account for potential fluctuations in the background values, the constant 1.5 is utilized. Table 3 lists the Igeo evaluation standards. The background values of the studied elements are shown in Table 1.

Table 3.

Geoaccumulation index classification.

| Igeoa | Pollution intensity |

|---|---|

| Igeo≤0 | Uncontaminated |

| 0 < Igeo<1 | Uncontaminated to slightly contaminated |

| 1 < Igeo<2 | Uncontaminated to slightly contaminated |

| 2 < Igeo<3 | Slightly contaminated to very contaminated |

| 3 < Igeo<4 | Very contaminated |

| 4 < Igeo<5 | Very contaminated to severely contaminated |

| Igeo>5 | Heavily contaminated |

a56.

Health risk assessment of HMs in soil

A health risk assessment was conducted to help determine the risk of human exposure to HMs57. Health risk assessment includes hazard identification, exposure assessment, dose response, and hazard characterization58. Humans can be exposed to HMs through ingestion, inhalation and dermal contact. Equations (6–8) were used to determine the chronic daily intake (CDI) of metals through these pathways to estimate health risk:

|

6 |

|

7 |

|

8 |

CDIing, CDIinh, and CDIderm are the chronic daily intake of HMs via ingestion, inhalation and dermal contact (mg kg−1 d−1); Csoil is concentration of HMs in soil (mg kg−1); IngRsoil is the ingestion rate (mg d−1); EF is the exposure frequency (d y−1); ED is the exposure duration (y); BW is the body weight of the exposed individual (kg); AT is the time period over which the dose is averaged (d); InhRsoil is the inhalation rate (m3 d−1); PEF is the particulate emission factor (m3 kg−1); SA is exposed skin area (cm2); AF is soil adherence factor (mg cm−2 d−1); ABS is the fraction of the applied dose absorbed across the skin. Table 4 shows the parameters and the corresponding values used to calculate the CDI of the HMs via the different exposure pathways. Based on the CDI, the carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks to humans were calculated.

Table 4.

Parameters used to calculate the chronic daily intake (CDI) of the HMs by adults and children (in Μg kg− 1 d− 1).

| Parameter | Interpretation | Units | Observed concentration | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | Children | ||||

| Csoil | Heavy metal concentration in soil | µg kg−1 | This study | ||

| IngRsoil | Ingestion rate | µg d−1 | 100 | 200 | 59 |

| EF | Exposure frequency | d y−1 | 350 | 350 | |

| ED | Exposure duration | y | 300 | 6 | |

| BW | Body weight | Kg | 70 | 15 | |

| AT | Average time (non-carcinogenic) | D | ED × 365 | ED × 365 | |

| AT | Average time (carcinogenic) | D | 25,500 | 25,500 | |

| SA | Exposed skin area | cm2 | 5800 | 2800 | |

| AF | Soil adherence factor | µg cm−2 d−1 | 0.07 | ||

| ABS(Cd) | Fraction of the applied dose of the HMs absorbed across the skin | - | 0.001 | 0.001 | 28 |

| ABS(Hg) | 0.05 | 0.001 | 59 | ||

| ABS(Cr) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 28 | ||

| ABS(Ni) | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| ABS(Pb) | 0.006 | 0.001 | 59 | ||

| ABS(Zn) | 0.02 | 0.001 | |||

| ABS(Cu) | 0.1 | 0.001 | |||

| IngRsoil | Inhalation rate | m3 d−1 | 20 | 7.3 | |

| PEF | Particle emission factor | m3 kg−1 | 1.36 × 109 | 1.36 × 109 | |

For the non-carcinogenic health hazard, Hazard Quotient (HQ) for each HMs were first determined using the corresponding reference dose as shown in Eq. (9). HQ is the daily exposure of HMs to humans that’s not likely to represent a calculable hazard of pernicious impact amid a lifetime57. To evaluate the in general potential non-carcinogenic health risk, the HQ calculated for each heavy metal for all the exposure pathways was summed and expressed as a Hazard Index (HI) (Eq. 10). For the components that can induce carcinogenesis (Cd, Hg, Cr and Pb), carcinogenic risk (CR) was evaluated by duplicating the CDI by the corresponding cancer slope figure (CSF) to create the carcinogenic hazard for that HMs (Eq. 11). Total carcinogenic risk (TCR) was decided as the entirety of the dangers from all introduction pathways for all individual metals (Eq. 12):

|

9 |

|

10 |

|

11 |

|

12 |

RfD (mg kg−1d−1) and CSF (mg kg−1d−1) refer to reference dose and carcinogenic slope factor, respectively. RfD and CSF values of metals for different exposure routes are shown in Table 5. According to57, if HI < 1, there is no non-carcinogenic health hazard. However, if HI > 1, there may be concern about a potential risk to human health. The range of acceptable total carcinogenic risk for regulatory purposes is 1.0 × 10−6 to 1.0 × 10−4. TCR ≤ 1.0 × 10−6 indicates virtual immunity, and TCR ≥ 1.0 × 10−4indicates a potential risk60.

Table 5.

The reference doses (RfD) and carcinogenic slope factors (CSF) used in health risk assessment.

| RfD (mg kg−1 d−1) | CSF (mg kg d−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | Ingestion | Dermal | Inhalation | Ingestion | Dermal | Inhalation |

| Hga | 3.00 × 10−4 | 3.0 × 10−4 | 8.60 × 10−5 | - | - | - |

| Crb, c | 3.00 × 10−3 | 6.0 × 10−5 | 2.86 × 10−5 | 5.0 × 10−1 | 2.00 × 10−1 | 42.0 × 10−1 |

| Nib, c | 2.00 × 10−2 | 5.4 × 10−3 | 2.06 × 10−2 | 8.4 × 10−1 | - | 8.40 × 10−1 |

| Pba | 3.50 × 10−3 | 5.2 × 10−4 | 3.52 × 10−3 | 8.5 × 10−3 | - | 4.20 × 10−2 |

| Zna | 3.00 × 10−1 | 6.0 × 10−1 | 3.00 × 10−1 | - | - | - |

| Cua | 4.00 × 10−2 | 1.2 × 10−2 | 4.02 × 10−3 | - | - | - |

| Cdb, c | 1.00 × 10−3 | 1.0 × 10−5 | 2.40 × 10−6 | 63.0 × 10−1 | - | 63.0 × 10−1 |

Evaluation of groundwater HMs pollution

Exposure assessment

The average daily dose (ADD) was calculated according to the following equation (Eq. 13):

|

13 |

where ADD is the average daily dose during the exposure (mg kg−1 d−1) and C represent the arsenic concentration in water (mg l−1), IR is water ingestion rate (2 L for adults and one for children’s), ED is exposure duration (70 years for adults and ten for children), EF is exposure frequency (365 d y−1), BW is body weight (72 kg for adults and 32.7 kg for children), and AT is average life time (25,550 days for adults and 3650 days for children).

Human health risk assessment

In this study, carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk levels were assessed. Generally, the hazard quotient (HQ) indices can be calculated by the following equation (Eq. 14):

|

14 |

Where RFD is the reference dose (mg kg−1 d−1). Occurrence of non-carcinogenic effects is possible when HQ values are more than unity. The excess lifetime cancer risk (ELCR) was calculated using following equation (Eq. 15)66,67.

|

15 |

Result and discussion

Concentration and distribution of HMs in soil

The average concentration of HMs in soil samples shows notable variations between irrigated and rainfed farming Fig. 3. In irrigated farming, the average concentration of Zn ranged from 216.52 ± 0 µg kg⁻¹, and Cr from 35.28 ± 1.37 µg kg⁻¹. In rainfed farming, the average concentration of Zn was 111.72 ± 0 µg kg⁻¹. Zinc exhibited the highest average concentration in both farming methods, with significant changes observed in the concentration of HMs. These results indicate spatial changes and heterogeneity based on the type and amount of HMs present at the site. These variations may be attributed to different sources of HMs at the site.

Fig. 3.

Concentration and distribution of heavy metals (HMs) in soil and groundwater.

To assess the suitability of the soil for agriculture, the concentration of HMs in the soil was compared with the maximum permissible concentration (MAC) and the standards set by the Iranian Environmental Organization (IEO) as shown in Table 1. The average concentration of metals in both types of crops was within the permissible range for agricultural soils. Cu and Zn are essential plant micronutrients, mobile in most soils, and readily accumulated by plants72,73. Conversely, Pb and Hg are non-essential plant micronutrients. According to74, less than 5% of Pb in the root is transported to the aerial organs, and excessive Pb absorption can inhibit plant respiration and photosynthesis. Unlike Pb, Hg is easily absorbed by the root system and translocated within plants. High levels of Hg in soil can lead to abnormal seedling growth and root development, affect biomass production, inhibit photosynthesis, and impair water uptake75.

The significant variation in Zn concentrations between irrigated and rainfed soils underscores the influence of agricultural practices on HM distribution. Higher Zn levels in irrigated farming soils may be linked to the use of Zn-enriched fertilizers or irrigation water sources76. The observed heterogeneity in HM concentrations suggests diverse contamination sources, possibly from industrial activities, atmospheric deposition, or agricultural inputs77. Despite these variations, the concentrations of HMs remained within the permissible limits set by the MAC and IEO standards, indicating that the soils are generally suitable for agriculture78. The essential nature of Cu and Zn for plant health highlights the importance of maintaining adequate levels of these micronutrients in soils. However, the presence of non-essential and potentially toxic metals like Pb and Hg requires careful management to prevent adverse effects on plant growth and development. The low translocation of Pb within plants mitigates some risks, but the high mobility and toxicity of Hg necessitate ongoing monitoring and management to avoid negative impacts on crop yield and quality. Ensuring the long-term sustainability of agricultural soils involves not only adhering to permissible HM concentrations but also implementing practices that minimize HM accumulation and enhance soil health. Regular soil testing, appropriate use of fertilizers, and monitoring of irrigation water quality are essential strategies for managing HM levels and supporting productive agricultural systems79–81.

The origin of HMs and their relationship with soil properties

The results of the Pearson correlation analysis for HMs and soil properties revealed intricate interactions. Soil pH exhibited a negative relationship with OM and NC, but a positive relationship with HM concentrations. This suggests that as soil acidity decreases, OM and NC increase, while higher pH levels may enhance the availability and mobility of heavy metals in the soil. Conversely, EC, OM, and NC showed negative correlations with HM concentrations, which could be attributed to increased microbial activity and OM decomposition in more acidic conditions (Fig. 4). The negative relationships between EC, OM, and NC with HM concentrations highlight their potential mitigating effects on HM accumulation. Higher OM content can bind HMs, reducing their bioavailability, while NC may influence microbial processes that immobilize HMs. The role of EC in these interactions suggests that soil salinity can also impact HM dynamics82–84.

Fig. 4.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients among measured traits.

In both rainfed and irrigated farming systems, Hg, Cr, and Ni exhibited the highest correlations with other HM concentrations. Zn had the highest positive correlation with itself, while Pb showed positive correlations with Zn and Cu. Cd displayed positive correlations with Hg and Cr (Fig. 4). The strong correlations between Hg, Cr, and Ni with other HMs in both farming systems indicate common sources or similar behaviors in the soil environment. The significant correlation between Zn and itself may reflect consistent inputs or stable concentrations over time. Pb’s positive correlation with Zn and Cu suggests potential co-contamination sources, possibly from industrial or agricultural activities. Cd’s positive correlation with Hg and Cr points to shared contamination pathways or similar chemical properties that influence their distribution in the soil.

To manage and mitigate HM contamination, it is essential to consider these interactions and their implications for soil health and crop safety. Enhancing soil OM, monitoring soil pH, and managing salinity levels through appropriate agricultural practices can help reduce HM bioavailability and uptake by plants. Implementing these strategies will contribute to sustainable soil management and ensure the long-term productivity and safety of agricultural systems85–87.

Pollution indicators

The contamination factor (Cf) values for HMs are presented in Fig. 5. The results indicate that soil contamination with Hg in both irrigated and rainfed farming is very high, leading to a correspondingly high degree of contamination for this metal. Cr contamination is very high in irrigated farming and moderate in rainfed farming. For Cd, very low pollution was observed in irrigated farming, whereas it was very high in rainfed farming. Cu has caused considerable pollution in irrigated farming, while other metals exhibited very low pollution factors. The degree of contamination (Cdeg) indicates a very high level of HM pollution in all regions. Specifically, the Cdeg of soil in irrigated farming is very high for Cd, Cu, Cr, Zn, and Hg. In contrast, Ni has an average degree of contamination, and Pb has a low Cdeg. The high contamination factor values for Hg in both irrigated and rainfed farming soils suggest significant environmental inputs or historical contamination from industrial or agricultural activities. The elevated Cr levels in irrigated soils could be linked to specific irrigation water sources or the use of Cr-containing agrochemicals. Conversely, the higher Cd contamination in rainfed soils indicates potential atmospheric deposition or localized sources not affecting irrigated farming areas88.

Fig. 5.

Box-plots of the natural logarithm of the Cf values for HMs in soils.

The substantial pollution caused by Cu in irrigated farming soils highlights the need for careful management of Cu-based fertilizers or fungicides, which could contribute to soil contamination. The consistently low pollution factors for other metals suggest that their sources and mobility in the soil are less impactful under current agricultural practices89,90. The overall high degree of HM pollution (Cdeg) across all regions underscores the necessity for comprehensive soil management strategies. The particularly high Cdeg in irrigated farming soils for Cd, Cu, Cr, Zn, and Hg points to the cumulative impact of irrigation practices on HM accumulation. The moderate contamination degree for Ni and low for Pb indicate that these metals are less of a concern but still require monitoring to prevent future escalation. To mitigate HM pollution, it is essential to implement practices such as regular soil testing, use of clean irrigation water, and controlled application of fertilizers and pesticides. Adopting phytoremediation techniques, enhancing organic matter content, and employing crop rotation can also help reduce HM levels in soils. Continuous monitoring of industrial emissions and adherence to environmental guidelines will be crucial in maintaining soil health and ensuring the safety and productivity of agricultural lands91,92.

The determined PLI was 71.17 in irrigated farming and 18.22 in rainfed farming, indicating heavy soil contamination with HMs across the entire site (Fig. 6). The significant difference in PLI values between irrigated and rainfed farming suggests that irrigation practices may exacerbate HM accumulation in soils. The much higher PLI in irrigated farming areas highlights the potential for irrigation water to introduce or mobilize HMs, thereby increasing their concentration in the soil. This could be due to the use of contaminated water sources, irrigation techniques that enhance metal mobility, or the cumulative effect of repeated irrigation cycles93,94. In contrast, the lower PLI in rainfed farming implies that natural precipitation may dilute or distribute HMs more evenly, reducing their overall concentration. However, the presence of contamination even in rainfed farming areas indicates that other factors, such as atmospheric deposition or historical land use, may also contribute to soil contamination.

Fig. 6.

Box-plots of the PLI values for HMs in soils.

To address the heavy soil contamination indicated by the high PLI values, it is crucial to implement effective soil management strategies. This could include the use of clean water sources for irrigation, regular monitoring of soil and water quality, and the application of soil amendments that can immobilize or adsorb HMs. Additionally, integrating phytoremediation techniques, which utilize plants to absorb and accumulate HMs, could help reduce soil contamination over time. By adopting these measures, it is possible to mitigate the adverse effects of HM contamination on soil health and agricultural productivity, ensuring the long-term sustainability of farming practices in the affected areas95–98.

According to Fig. 7, the Igeo results indicate that the soil is unpolluted for Hg in both types of cultivation, for Cr and Cu in rainfed farming, and for Cd in rainfed cultivation. However, Cd in irrigated farming and Pb show slight pollution. In irrigated farming, Cr, Ni, and Cu exhibit slight to moderate pollution, while Zn in rainfed farming shows slight to moderate pollution. Notably, Zn in rainfed farming and Ni in irrigated farming demonstrate significant pollution levels.

Fig. 7.

Igeo values for HMs in soils.

The Igeo results provide valuable insights into the pollution status of various HMs in the soil under different cultivation methods. The unpolluted status for Hg, Cr, and Cu in certain conditions suggests limited anthropogenic influence or effective natural attenuation processes for these metals. The slight pollution observed for Cd and Pb in rainfed farming indicates localized sources of contamination, possibly from atmospheric deposition or residual agricultural inputs99. The presence of slight to moderate pollution for Cr, Ni, and Cu in irrigated farming soils highlights the potential impact of irrigation practices on metal accumulation. This could be due to the use of contaminated water sources or the leaching and mobilization of metals through irrigation processes. Similarly, the significant pollution levels for Zn in rainfed farming and Ni in irrigated farming suggest specific contamination sources or higher mobility of these metals in the respective farming systems100–102.

To mitigate the observed pollution levels, it is essential to adopt targeted soil management practices. For instance, ensuring the use of clean and uncontaminated irrigation water can help reduce the accumulation of metals in irrigated farming soils. Additionally, implementing soil remediation techniques, such as the application of organic amendments or the use of metal-accumulating plants, can aid in reducing HM concentrations. Regular monitoring and assessment of soil health, along with the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices, will be crucial in managing and mitigating HM contamination. By addressing the sources and pathways of metal pollution, it is possible to enhance soil quality and ensure safe and productive agricultural lands103,104.

Ecological risks

The results of the PERI assessments are shown in Fig. 8. For each HM, Ni, Pb, and Zn were found to pose low ecological risk factors in both rainfed and irrigated farming (RI < 150). However, Hg poses a significant ecological risk factor (300 < RI < 600). Cr and Cu in irrigated farming also exhibited low ecological risk (Fig. 8). The PERI assessments provide critical insights into the ecological risks associated with different HMs in agricultural soils. The low ecological risk posed by Ni, Pb, and Zn suggests that these metals, while present, are not currently at concentrations that pose significant threats to the environment or human health in either rainfed or irrigated farming systems. This indicates that current agricultural practices and environmental conditions help maintain these metals at safe levels.

Fig. 8.

Potential ecological risk index (PERI) values for HMs in soils.

In contrast, the significant ecological risk posed by Hg highlights a pressing concern. The high PERI values for Hg suggest that it is present at levels that could adversely affect the ecosystem. This may be due to its high toxicity, persistence in the environment, and ability to bioaccumulate in organisms. The significant risk factor for Hg necessitates urgent attention and mitigation strategies to prevent potential ecological damage105–107. The low ecological risk associated with Cr and Cu in irrigated farming suggests that irrigation practices may not significantly elevate the concentrations of these metals to hazardous levels. However, continued monitoring is essential to ensure that their levels remain within safe limits, as changes in agricultural practices or environmental conditions could alter their risk profiles79. To mitigate the potential ecological risks posed by HMs, particularly Hg, it is crucial to implement targeted soil and water management strategies. These might include using clean water sources, reducing the application of Hg-containing agrochemicals, and employing soil amendments that immobilize or reduce the bioavailability of Hg. Additionally, adopting phytoremediation techniques can help extract and stabilize HMs from contaminated soils. Regular monitoring and assessment of HM concentrations and their ecological risk indices will be essential in maintaining safe and sustainable agricultural practices. By understanding and managing the risks associated with heavy metals, it is possible to protect both the environment and agricultural productivity108,109.

Health risk assessment of HMs in soil

The results of the CDI of metals indicate that ingestion poses a greater risk of absorption for both children and adults compared to skin absorption and inhalation. Among adults, the risk of ingestion was similar in both irrigated and rainfed farming systems. However, for children, except for Cd, the risk of ingestion absorption was significantly higher in rainfed farming soils compared to irrigated farming soils (Fig. 9). These findings underscore that ingestion is the predominant route of metal absorption for both age groups, emphasizing the importance of mitigating soil contamination to reduce health risks. The heightened ingestion risk for children in rainfed soils, excluding Cd, suggests greater bioavailability of certain metals under these conditions, potentially influenced by soil properties specific to rainfed farming. This highlights the need for targeted interventions to minimize metal exposure, particularly among vulnerable populations such as children. The absence of dermal absorption risk in children but its presence in adults for Hg and Cu in rainfed farming soils indicates age-related differences in exposure and absorption rates, possibly due to variations in skin permeability or activities leading to soil contact. This underscores the necessity for age-specific risk assessments and mitigation strategies37,110.

Fig. 9.

The CDI values for HMs in soils.

Additionally, while no dermal absorption risk was observed in children, adults exposed to soils irrigated under rainfed farming practices faced potential dermal absorption risks from Hg and Cu. Children showed a risk of respiratory absorption in irrigated farming soils, with all metals except Hg indicating a higher risk compared to rainfed soils (Fig. 9). This observation suggests that irrigation practices may enhance the inhalation exposure pathway through the generation of dust or aerosols containing metal particles. Implementing measures to reduce dust generation and improve irrigation methods could help mitigate this risk111. Given the industrial context of the study area, with nearby gasoline refineries, petroleum facilities, and fuel oil power plants, these sources likely contribute significantly to observed metal contamination. Therefore, efforts to monitor and regulate emissions from these industrial activities, alongside soil remediation efforts and public health initiatives, are crucial for reducing exposure risks and safeguarding community health. In conclusion, a comprehensive approach encompassing regular soil testing, adoption of safe irrigation practices, and community education on exposure risks is essential for managing metal contamination and protecting health in agricultural areas adjacent to industrial sites.

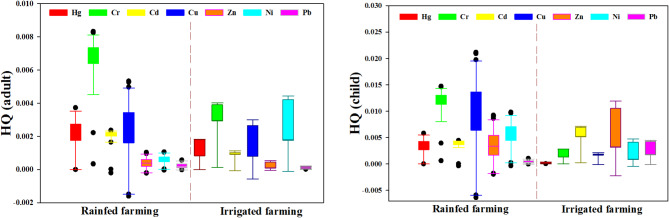

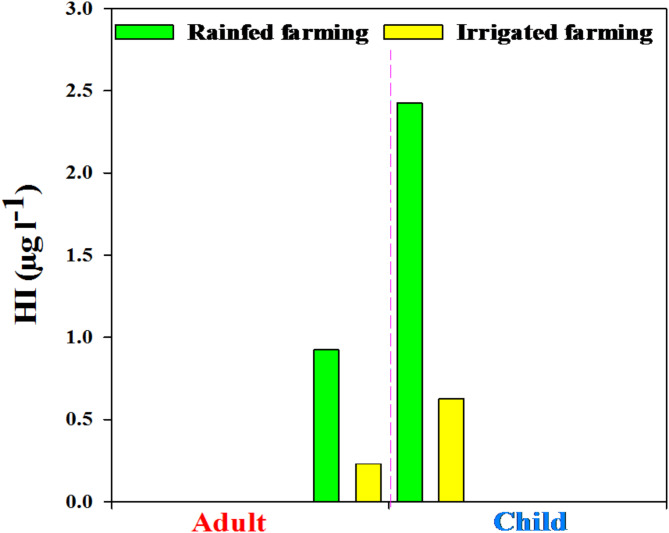

The HQ and HI results from soil samples in the studied area indicate that the risk of non-carcinogenic diseases for both children and adults consuming these soils is below one, suggesting no significant non-carcinogenic risk (Fig. 10). However, the HQ and HI results underscore a potential carcinogenic risk, particularly concerning for children. This higher carcinogenic risk in children emphasizes their heightened vulnerability to environmental contaminants, necessitating stricter safety measures and ongoing monitoring112. The findings highlight the importance of targeted interventions to mitigate potential health risks associated with carcinogenic substances in soils. Strategies such as soil remediation, enhanced monitoring of soil quality, and public health initiatives aimed at reducing exposure pathways are crucial for safeguarding community health, particularly for vulnerable populations like children. Continued research and comprehensive risk assessments will be essential for developing effective policies and practices to manage and minimize carcinogenic risks associated with soil contamination.

Fig. 10.

The hazard quotient (HQ) values for HMs in soils.

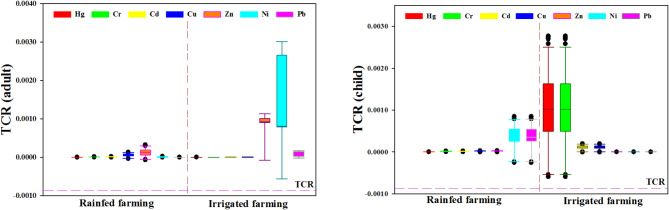

Figure 11presents measurements of total carcinogenic risk. The graphs indicate that for adults, all values remain below standard limits for carcinogenicity in the soil. However, concerning children, all studied metals pose a carcinogenic risk. Specifically, Zn and Cu in rainfed farming exhibit a higher risk of carcinogenesis compared to irrigated farming, whereas Ni shows a higher risk in irrigated farming. The elevated carcinogenic risk of Zn and Cu in rainfed farming suggests these metals are more prevalent or bioavailable under rainfed conditions. This disparity may stem from variations in soil chemistry, water availability, or other environmental factors influencing metal mobility and uptake. Conversely, the heightened carcinogenic risk of Ni in irrigated farming underscores the potential influence of irrigation practices113.

Fig. 11.

Total carcinogenic risk (TCR) values for HMs in soils.

The HI values are depicted in Fig. 12. As shown, the cumulative metal intake (HI) in children and adults consuming soil from water-irrigated areas is approximately double that found in samples from rainfed farming systems. Overall, the HI for metals is higher in children compared to adults. The HI values indicate significant differences in exposure risks between adults and children under varying atmospheric conditions. Adults consistently show higher HI values compared to children, with values in dry air conditions being five times higher for adults than children. Similarly, in the blue atmosphere, adults exhibit HI values that are 4.5 times greater than those observed in children.

Fig. 12.

The hazard index (HI) values for HMs in soils.

These findings highlight several key points. Firstly, they underscore the greater susceptibility of adults to environmental contaminants, potentially due to factors such as higher body weight and different metabolic rates influencing exposure pathways. Secondly, the variations between dry air and blue atmosphere conditions suggest that atmospheric factors play a crucial role in contaminant dispersion and subsequent exposure levels. Dry air conditions may lead to higher concentrations or reduced dispersion of contaminants compared to the blue atmosphere, impacting overall exposure risks114. The elevated HI values in adults also raise concerns about cumulative health risks, including carcinogenicity and non-carcinogenic effects. This emphasizes the importance of effective mitigation strategies and regulatory measures to minimize exposure risks, particularly for vulnerable populations such as children.

Concentration and distribution of HMs in groundwater

The assessment of metals in groundwater reveals that in areas where surface lands are irrigated using rainfed farming systems, Zn shows a concentration range of 23.41 ± 5.65 µg l−1 with an average of 19.12 µg l−1, and Cr ranges from 18.15 ± 10.52 µg l−1 with an average of 16.95 µg l−1. These concentrations are the highest among the metals analyzed. Similarly, in groundwater where surface lands are irrigated with water, Zn exhibits a concentration range of 27.29 ± 8.08 µg l−1 with an average of 22.80 µg l−1, and Cr ranges from 19.54 ± 13.90 µg l−1 with an average of 19 µg l−1, also showing the highest values compared to other metals. Importantly, the concentrations of these two metals in groundwater from areas with irrigated farming are higher than those from rainfed farming systems. These results underscore the impact of agricultural management systems on metal concentrations in groundwater. The elevated levels of Zn and Cr in areas irrigated with water compared to rainfed methods suggest that irrigation may enhance the leaching or mobilization of these metals from soil into groundwater. This phenomenon likely results from increased water movement and the dissolution of soil-bound metals during irrigation, thereby elevating metal content in groundwater115.

The notable presence of Zn and Cr in both agricultural management systems indicates potential implications for groundwater quality, posing risks to both human health and the environment. Given their essential roles in various biological processes, elevated levels of Zn and Cr could lead to adverse health effects if consumed in significant quantities over time. For instance, high concentrations of Cr can be toxic and pose serious health risks, including carcinogenic effects. To address these challenges, it is crucial to implement measures aimed at minimizing metal leaching and accumulation in groundwater. Strategies may include using clean water sources for irrigation, employing soil amendments to reduce metal mobility, and implementing regular monitoring of groundwater quality. Additionally, understanding the sources of metal contamination, such as industrial emissions from nearby gasoline refineries, petroleum facilities, and fuel oil power plants, can inform targeted mitigation strategies. Ensuring sustainable irrigation practices and safeguarding groundwater quality are essential for maintaining the health of agricultural ecosystems and surrounding communities. By adopting these approaches, it is possible to mitigate the risks associated with metal contamination, promoting the long-term sustainability of agricultural practices and environmental health116,117.

Health risk assessment of HMs in groundwater

The HQ results from groundwater samples in the study area indicate that the risk of non-carcinogenic diseases associated with consuming these waters is below one for both children and adults, suggesting no significant non-carcinogenic risk (Fig. 13b). Figure 13a shows the Add values of metals in groundwater, revealing higher Add values in areas irrigated with water compared to rainfed systems, with Zn > Cr > Cu in order. The lifetime carcinogenic risk assessment indicates that among other metals, Hg, Cd, and Cr are carcinogenic and pose a cancer risk across all groundwater samples. These metals demonstrate greater carcinogenic potential in irrigated farming areas than in rainfed farming (Fig. 13c).

Fig. 13.

The ADD, the HQ and, the ELCR values for HMs in groundwater.

The HQ results provide reassurance that groundwater in the studied area does not pose a significant risk of non-carcinogenic diseases for either children or adults. However, the higher Add values in water-irrigated areas underscore the potential for increased metal exposure compared to rainfed systems. This trend suggests that water irrigation practices may facilitate the leaching and accumulation of metals such as Zn, Cr, and Cu in groundwater, highlighting the need for vigilant monitoring and management. The findings from the lifetime carcinogenic risk assessment emphasize the presence of carcinogenic metals—Hg, Cd, and Cr—in all groundwater samples, with heightened risks associated with irrigated farming systems. This is particularly critical in agricultural regions near industrial facilities such as gasoline refineries, petroleum plants, and fuel oil power plants, where industrial emissions may contribute to metal contamination. The elevated carcinogenicity observed in irrigated farming systems suggests that irrigation practices could exacerbate the mobilization and bioavailability of these harmful metals118.

To mitigate these risks effectively, it is crucial to implement robust water management practices and establish regular monitoring protocols for groundwater quality. Strategies may include using cleaner sources of irrigation water, applying soil amendments to reduce metal mobility, and adopting phytoremediation techniques to manage metal contamination effectively. Furthermore, efforts to identify and control industrial emissions are essential to mitigate the introduction of these metals into the environment. In conclusion, the study underscores the importance of a comprehensive approach to manage and monitor groundwater quality in agricultural areas, particularly those in proximity to industrial activities. Such an approach is essential for safeguarding public health and ensuring the long-term sustainability of agricultural practices.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of soil and groundwater samples from agricultural areas surrounding three industrial plants: a gasoline refinery, a petroleum facility, and a fuel oil power plant. The findings reveal significant insights into metal contamination and associated risks. Soil properties exhibited neutral to slightly alkaline pH levels, suitable for most crops, although the higher electrical conductivity (EC) in irrigated farming soils indicates potential salinity buildup that may affect crop yields. Organic matter (OM) and nitrogen content (NC) varied across soil types, with loam and sand in rainfed farming soils displaying higher levels, which are beneficial for soil health. Contamination factor values indicated very high mercury (Hg) contamination in both irrigated and rainfed farming soils, with substantial variations in contamination levels for other metals. The Potential Ecological Risk Index highlighted significant ecological risks posed by Hg, while other metals presented lower risks.

Furthermore, the Pollution Load Index confirmed heavy metal contamination in soils across the sites, particularly within irrigated farming systems. Human health risk assessments indicated that ingestion poses the greatest risk of metal absorption, particularly for children. Although the Hazard Quotient (HQ) and Hazard Index (HI) values suggested no significant non-carcinogenic risk, lifetime carcinogenic risk assessments identified Hg, cadmium (Cd), and chromium (Cr) as carcinogenic threats, especially in irrigated farming systems. Groundwater analysis revealed elevated metal concentrations in irrigated farming systems, with zinc (Zn) and Cr showing the highest levels. The additive effects of metals were more pronounced in these systems, further raising lifetime carcinogenic risk levels. In light of these findings, there is an urgent need for public health policies that address the risks associated with heavy metal exposure in agricultural settings, particularly for vulnerable populations such as children. This study underscores the critical importance of implementing sustainable agricultural practices, stringent environmental monitoring, enhanced industrial regulations, and effective water management strategies. Long-term studies and continuous monitoring are essential to understand the ongoing impacts of metal contamination and to develop intervention strategies that protect public health and ensure the sustainability of agriculture in industrial regions.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted through a collaboration between Arak University and the Department of Agriculture of Markazi Province. The authors wish to thank Arak University for giving us the opportunity to carry out this research. We are immensely thankful for the assistance and cooperation of the Agriculture and Environment Faculty students.

Author contributions

S.S. and F.S. prepared data and performed model runs, designed the study, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

Data are available on reasonable request from the first author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Esmaeili, A., Moore, F., Keshavarzi, B., Jaafarzadeh, N. & Kermani, M. A geochemical survey of heavy metals in agricultural and background soils of the Isfahan industrial zone. Iran. Catena. 121, 88–98 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marufi, N., Conti, G. O., Ahmadinejad, P., Ferrante, M. & Mohammadi, A. A. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic human health risk assessments of heavy metals contamination in drinking water supplies in Iran: a systematic review. Rev. Environ. Health. 39, 91–100 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouhani, A., Shadloo, S., Naqibzadeh, A., Hejcman, M. & derakhsh, M. Pollution and health risk assessment of heavy metals in the soil around an open landfill site in a developing country (Kazerun, Iran). Chem. Afr.6, 2139–2149 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fida, M., Li, P., Wang, Y., Alam, S. M. K. & Nsabimana, A. Water contamination and human health risks in Pakistan: a review. Expo Heal. 15, 619–639 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhtar, N., Syakir Ishak, M. I., Bhawani, S. A. & Umar, K. Various natural and anthropogenic factors responsible for water quality degradation: A review. Water13, 2660 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vareda, J. P., Valente, A. J. M. & Durães, L. Assessment of heavy metal pollution from anthropogenic activities and remediation strategies: A review. J. Environ. Manage.246, 101–118 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thakare, M. et al. Current Research in Biotechnology, (n.d.).

- 8.Verma, N., Rachamalla, M., Kumar, P. S. & Dua, K. Assessment and impact of metal toxicity on wildlife and human health, in: Met. Water, Elsevier: pp. 93–110. (2023).

- 9.Li, C. et al. Occurrence and behavior of arsenic in groundwater-aquifer system of irrigated areas, sci. Total Environ.838, 155991 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharafi, S., Kazemi, A. & Amiri, Z. Estimating energy consumption and GHG emissions in crop production: A machine learning approach. J. Clean. Prod.408, 137242 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goswami, R. & Neog, N. Heavy metal pollution in the environment: impact on air quality and human health implications, in: Heavy Met. Toxic. Environ. Concerns, Remediat. Oppor., Springer, : 75–103. (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor, S. .E. Mechanisms linking early life stress to adult health outcomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.107, 8507–8512 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawut, R. et al. Possibility of optimized indices for the assessment of heavy metal contents in soil around an open pit coal mine area. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf.73, 14–25 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zini, L. B. & Gutterres, M. Chemical contaminants in Brazilian drinking water: a systematic review. J. Water Health. 19, 351–369 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, P., Karunanidhi, D., Subramani, T. & Srinivasamoorthy, K. Sources and consequences of groundwater contamination. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.80, 1–10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reberski, J. L., Terzić, J., Maurice, L. D. & Lapworth, D. J. Emerging organic contaminants in karst groundwater: A global level assessment. J. Hydrol.604, 127242 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharafi, S. & Nahvinia, M. J. Sustainability insights: enhancing rainfed wheat and barley yield prediction in arid regions, agric. Water Manag. 299, 108857 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma, A., Grewal, A. S., Sharma, D. & Srivastav, A. L. Heavy metal contamination in water: consequences on human health and environment, in: Met. Water, Elsevier: pp. 39–52. (2023).

- 19.Lugun, O., Singh, R., Jha, S. & Pandey, A. K. Impact of Heavy Metals on Different Ecosystems, In: Environ. Toxicol. Ecosystpp. 139–164 (CRC, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tauqeer, H. M. et al. The current scenario and prospects of immobilization remediation technique for the management of heavy metals contaminated soils, approaches to remediat. Inorg. Pollut 155–185. (2021).

- 21.Abd Elnabi, M. K. et al. Abd Elaty, toxicity of heavy metals and recent advances in their removal: a review. Toxics11, 580 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong, S., Li, H., Wang, L., Tudi, M. & Yang, L. Concentration, Spatial distribution, contamination degree and human health risk assessment of heavy metals in urban soils across China between 2003 and 2019—a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 3099 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang, J. et al. Spatial distribution and source identification of heavy metals in surface soils in a typical coal mine City, Lianyuan, China, environ. Pollut225, 681–690 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen, Y. et al. Assessing the influence of immobilization remediation of heavy metal contaminated farmland on the physical properties of soil. Sci. Total Environ.781, 146773 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khanal, B. R., Shah, S. C., Sah, S. K., Shriwastav, C. P. & Acharya, B. S. Heavy metals accumulation in cauliflower (Brassica Oleracea L. Var. botrytis) grown in brewery sludge amended sandy loam soil. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Technol.2, 87–92 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong, J. et al. Contamination of heavy metals and isotopic tracing of Pb in surface and profile soils in a polluted farmland from a typical karst area in Southern China, sci. Total Environ.637, 1035–1045 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, G., Sun, G., Ren, Y., Luo, X. & Zhu, Y. Urban soil and human health: a review. Eur. J. Soil. Sci.69, 196–215 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myers, J., Kelly, T., Lawrie, C. & Riggs, K. United State Environmental Protection Agency, USEPA, Method M29 Sampling and Analysis, Environ. Technol. Verif. Report15–22 (Battelle, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pipoyan, D. et al. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk assessment of trace elements and pops in honey from Shirak and Syunik regions of Armenia. Chemosphere239, 124809 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shams, M. et al. Heavy metals exposure, carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic human health risks assessment of groundwater around mines in joghatai. Iran. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.102, 1884–1899 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maleki, A. & Jari, H. Evaluation of drinking water quality and non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risk assessment of heavy metals in rural areas of Kurdistan. Iran. Environ. Technol. Innov.23, 101668 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taghizadeh, S. F., Rezaee, R., Boskabady, M., Mashayekhi Sardoo, H. & Karimi, G. Exploring the carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk of chemicals present in vegetable oils. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.102, 5756–5784 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiang, M. et al. Heavy metal contamination risk assessment and correlation analysis of heavy metal contents in soil and crops. Environ. Pollut. 278, 116911 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, J. et al. Interactions between invasive plants and heavy metal stresses: a review. J. Plant. Ecol.15, 429–436 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu, J. et al. Sources, transfers and the fate of heavy metals in soil-wheat systems: the case of lead (Pb)/zinc (Zn) smelting region. J. Hazard. Mater.441, 129863 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng, R. et al. Underlying mechanisms responsible for restriction of uptake and translocation of heavy metals (metalloids) by selenium via root application in plants. J. Hazard. Mater.402, 123570 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, X. et al. Trinity assessment method applied to heavy-metal contamination in peri-urban soil–crop systems: A case study in Northeast China. Ecol. Indic.132, 108329 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghani, J. et al. Multi-geostatistical analyses of the Spatial distribution and source apportionment of potentially toxic elements in urban children’s park soils in Pakistan: A risk assessment study. Environ. Pollut. 311, 119961 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nawab, J. et al. Drinking water quality assessment of government, non-government and self-based schemes in the disaster affected areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Pakistan Expo Heal. 15, 567–583 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharafi, S., Nahvinia, M. J. & Salehi, F. Assessing the water footprints (WFPs) of agricultural products across arid regions: insights and implications for sustainable farming. Water16, 1311 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao, Z. Materials and fabrication needs for low-cost organic transistor circuits. Adv. Mater.12, 227–230 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan, S., Zhang, T., Zhang, B., Feng, H. & Siddique, K. H. M. Calibration of saline water quality assessment standard based on EC and CROSS considering soil water-salt transport and crack formation. J. Hydrol.633, 130975 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, J. et al. Evaluating the impacts of long-term saline water irrigation on soil salinity and cotton yield under plastic film mulching: A 15-year field study, agric. Water Manag. 293, 108703 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gul, N., Mangrio, M. A., Shaikh, I. A., Siyal, A. G. & Semiromi, M. T. Quantifying the impacts of varying groundwater table depths on cotton evapotranspiration, yield, water use efficiency, and root zone salinity using lysimeters, agric. Water Manag. 301, 108933 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharafi, S., Mohammadi Ghaleni, M. & Dragovich, D. Simulated runoff and Erosion on soils from wheat agroecosystems with different water management systems, Iran. Land12, 1790 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 46.El-Ramady, H. et al. Soil degradation under a changing climate: management from traditional to nano-approaches. Egypt. J. Soil. Sci. 64 (2024).

- 47.Mahgoub, M., Elalfy, E., Soussa, H. & Abdelmonem, Y. Relation between the soil erosion cover management factor and vegetation index in semi-arid basins. Environ. Earth Sci.83, 337 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan, S. et al. Drinking water quality and human health risk in Charsadda district. Pakistan J. Clean. Prod.60, 93–101 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edition, F. Guidelines for drinking-water quality. WHO Chron.38, 104–108 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ra, K. et al. Assessment of heavy metal contamination and its ecological risk in the surface sediments along the Coast of Korea. J. Coast Res. 105–110. (2013).

- 51.Turekian, K. K. & Wedepohl, K. H. Distribution of the elements in some major units of the Earth’s crust. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull.72, 175–192 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor, S. R. Abundance of chemical elements in the continental crust: a new table, geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 28, 1273–1285 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hakanson, L. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control. A sedimentological approach. Water Res.14, 975–1001 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watson, I. Applying case-based Reasoning: Techniques for Enterprise Systems (Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tomlinson, D. L., Wilson, J. G., Harris, C. R. & Jeffrey, D. W. Problems in the assessment of heavy-metal levels in estuaries and the formation of a pollution index. Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen. 33, 566–575 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muller, C. H. Allelopathy as a factor in ecological process, Vegetatio 348–357. (1969).

- 57.USEPA, Soil Screening Guidance: Fact Sheet, Evaluation 1–12. (1996).

- 58.Lee, S., Lee, B., Kim, J., Kim, K. & Lee, J. Human risk assessment for heavy metals and as contamination in the abandoned metal mine areas. Korea Environ. Monit. Assess.119, 233–244 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Obiri-Nyarko, F. et al. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in soils at the Kpone landfill site, Ghana: implication for ecological and health risk assessment. Chemosphere282, 131007 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang, H. et al. Contamination assessment, source apportionment and health risk assessment of heavy metals in paddy soils of Jiulong river basin, Southeast China. RSC Adv.9, 14736–14744. 10.1039/C9RA02333J (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamunda, C., Mathuthu, M. & Madhuku, M. Health risk assessment of heavy metals in soils from Witwatersrand gold mining basin, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 13, 663 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kohzadi, S., Shahmoradi, B., Ghaderi, E., Loqmani, H. & Maleki, A. Concentration, source, and potential human health risk of heavy metals in the commonly consumed medicinal plants. Biol. Trace Elem. Res.187, 41–50 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu, K. et al. Source and potential risk assessment of suspended atmospheric microplastics in Shanghai, sci. Total Environ.675, 462–471 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou, J. et al. A new criterion for the health risk assessment of se and Pb exposure to residents near a smelter. Environ. Pollut. 244, 218–227 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ali, I., Golgeci, I. & Arslan, A. Achieving resilience through knowledge management practices and risk management culture in agri-food supply chains, supply chain Manag. Int. J.28, 284–299 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muhammad, M. Z., Char, A. K., bin Yasoa, M. R. & Hassan, Z. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) competing in the global business environment: A case of Malaysia. Int. Bus. Res.3, 66 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uyanık, N. A. An alternative approach for the excess lifetime cancer risk and prediction of radiological parameters. Open. Chem.21, 20220359 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muhammad, S., Shah, M. T. & Khan, S. Health risk assessment of heavy metals and their source apportionment in drinking water of Kohistan region, Northern Pakistan. Microchem J.98, 334–343 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rim, K. T. Evaluations of carcinogens from comparison of cancer slope factors: meta-analysis and systemic literature reviews. Mol. Cell. Toxicol.19, 635–656 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thompson, C. M., Kirman, C. & Harris, M. A. Derivation of oral cancer slope factors for hexavalent chromium informed by Pharmacokinetic models and in vivo genotoxicity data. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.145, 105521 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jang, S., Shao, K. & Chiu, W. A. Beyond the cancer slope factor: broad application of bayesian and probabilistic approaches for cancer dose-response assessment. Environ. Int.175, 107959 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jayakumar, M., Surendran, U., Raja, P., Kumar, A. & Senapathi, V. A review of heavy metals accumulation pathways, sources and management in soils. Arab. J. Geosci.14, 2156 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vinogradov, D. V. & Zubkova, T. V. Accumulation of heavy metals by soil and agricultural plants in the zone of technogenic impact. Indian J. Agric. Res.56, 201–207 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bharti, R. & Sharma, R. Effect of heavy metals: an overview. Mater. Today Proc.51, 880–885 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singh, A. D. et al. Critical review on biogeochemical dynamics of mercury (Hg) and its abatement strategies. Chemosphere319, 137917 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Raza, S. et al. Effects of zinc-enriched amino acids on rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) for adaptation in saline-sodic soil conditions: growth, nutrient uptake and biofortification of zinc. South. Afr. J. Bot.162, 370–380 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou, H., Yue, X., Chen, Y. & Liu, Y. Source-specific probabilistic contamination risk and health risk assessment of soil heavy metals in a typical ancient mining area. Sci. Total Environ.906, 167772 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dunlap, R. A. Transportation Technologies for a Sustainable Future: Renewable Energy Options for Road, Rail, Marine and Air Transportation (IOP Publishing, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Braine, M. F., Kearnes, M. & Khan, S. J. Quality and risk management frameworks for biosolids: an assessment of current international practice. Sci. Total Environ.915, 169953 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rahman, S. U. et al. Pb Uptake, Accumulation, and Translocation in Plants: Plant Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Response (A review, 2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rashid, A. et al. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soil: environmental pollutants affecting crop health. Agronomy13, 1521 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amini, S., Ghadiri, H., Chen, C. & Marschner, P. Salt-affected soils, reclamation, carbon dynamics, and Biochar: a review. J. Soils Sediments. 16, 939–953 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li, X. et al. High salinity inhibits soil bacterial community mediating nitrogen cycling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.87, e01366–e01321 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jia, J. et al. Relationships between soil biodiversity and multifunctionality in croplands depend on salinity and organic matter. Geoderma429, 116273 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marambe, B. & Silva, P. SUSTAINABILITY MANAGEMENT IN AGRICULTURE—A SYSTEMS APPROACH, in: Handb. Sustain. Manag., World Scientific, : pp. 687–712. (2012).

- 86.Muhamediyeva, D. T., Safarova, L. U. & Mavlyanov, M. T. Environmental protection in the farming system, in: E3S Web Conf., EDP Sciences, : p. 2018. (2024).

- 87.Derpsch, R. et al. Nature’s Laws Declin. Soil. Productivity Conserv. Agric. Soil. Secur.14 100127. (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kulsum, P. G. P. S. et al. A state-of-the-art review on cadmium uptake, toxicity, and tolerance in rice: from physiological response to remediation process. Environ. Res.220, 115098 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gomes, D. G., Pieretti, J. C., Lourenço, I. M., Oliveira, H. C. & Seabra, A. B. Copper-based nanoparticles for pesticide effects, in: Inorg. Nanopesticides Nanofertilizers A View from Mech. Action to F. Appl., Springer, : pp. 187–212. (2022).

- 90.Chen, Z. et al. Toxic elements pollution risk as affected by various input sources in soils of greenhouses, Kiwifruit orchards, cereal fields, and forest/grassland. Environ. Pollut. 338, 122639 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liang, X. et al. Healthy soils for sustainable food production and environmental quality. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng.7, 347–355 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Merfield, C. New Zealand’s monitoring frameworks for agricultural sustainability and assurance, (2024).

- 93.Jia, Z. et al. Occurrence characteristics and risk assessment of microplastics in agricultural soils in the loess hilly gully area of Yan’an, China, sci. Total Environ.912, 169627 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Amjad, M. et al. Accumulation and translocation of lead in vegetables through intensive use of organic manure and mineral fertilizers with wastewater. Sci. Rep.14, 12641 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rashmi, I. et al. Soil Erosion and Sediments: a Source of Contamination and Impact on Agriculture Productivity, In: Agrochem. Soil Environ. Impacts Remediatpp. 313–345 (Springer, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chaudhary, P. et al. Application of synthetic consortia for improvement of soil fertility, pollution remediation, and agricultural productivity: a review. Agronomy13, 643 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhen, H. et al. Long-term effects of intensive application of manure on heavy metal pollution risk in protected-field vegetable production. Environ. Pollut. 263, 114552 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ahmed, T. et al. Current trends and future prospective in nanoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soils: A way forward towards sustainable agriculture. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.227, 112888 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nawrot, N. et al. Trace metal contamination of bottom sediments: a review of assessment measures and geochemical background determination methods. Minerals11, 872 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yu, H. et al. Comparative evaluation of groundwater, wastewater and Canal water for irrigation on toxic metal accumulation in soil and vegetable: pollution load and health risk assessment. Agric. Water Manag. 264, 107515 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 101.Oubane, M., Khadra, A., Ezzariai, A., Kouisni, L. & Hafidi, M. Heavy metal accumulation and genotoxic effect of long-term wastewater irrigated peri-urban agricultural soils in semiarid climate. Sci. Total Environ.794, 148611 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Khan, Z. I. et al. Evaluation of nickel toxicity and potential health implications of agriculturally diversely irrigated wheat crop varieties. Arab. J. Chem.16, 104934 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 103.Selvam, R., Kalaiyarasi, G. & Saritha, B. Heavy metal contamination in soils: risks and remediation, soil fertil. Plant. Nutr. 141. (2024).

- 104.Datta, K., Chakraborty, S. & Roychoudhury, A. Management of Soil, Waste and Water in the Context of Global Climate Change, In: Environ. Nexus Resour. Managpp. 1–26 (CRC, 2025). [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zafar, A., Javed, S., Akram, N. & Naqvi, S. A. R. Health Risks of Mercury, in: Mercur. Toxic. Mitig. Sustain. Nexus Approach, Springer, : pp. 67–92. (2024).

- 106.Yu, J. et al. Major influencing factors identification and probabilistic health risk assessment of soil potentially toxic elements pollution in coal and metal mines across China: A systematic review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.274, 116231 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mai, X. et al. Research progress on the environmental risk assessment and remediation technologies of heavy metal pollution in agricultural soil. J. Environ. Sci. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 108.Ghorbani, A. et al. Nano-enabled agrochemicals: mitigating heavy metal toxicity and enhancing crop adaptability for sustainable crop production. J. Nanobiotechnol.22, 91 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wan, Y., Liu, J., Zhuang, Z., Wang, Q. & Li, H. Heavy metals in agricultural soils: sources, influencing factors, and remediation strategies. Toxics12, 63 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vats, P., Hiranmai, R. Y. & Neeraj, A. Bioconversion of organic waste for solid waste management and sustainable agriculture—emphasized impact of bioelectromagnetic energy. Sustain. Clean. Technol. Environ. Remediat Ave Nano Biotechnol. 193–220. (2023).

- 111.Kong, J. et al. The risk factors and threshold level of subchronic inhalation exposure of reclaimed water. J. Environ. Sci.137, 639–650 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang, S. et al. Human health risk assessment for contaminated sites: A retrospective review. Environ. Int.171, 107700 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]