Abstract

Little is known about the evolution of vestibular dysfunction and health-related quality of life in bilateral vestibulopathy patients over time. Furthermore, it is unknown whether etiology influences the evolution. A retrospective study was performed investigating the vestibular function at two different time points during a median follow-up time of 24 months in 97 bilateral vestibulopathy patients. Additionally, to evaluate the quality of life and symptoms, validated questionnaires were analyzed. The sum of the caloric testing on the right side and the gain of the rotatory chair torsion swing test significantly decreased over time (p = 0.020 and p = 0.017, respectively). The left-sided caloric tests remained stable, but the median was already 0°/sec at baseline testing. On the contrary, vHIT gain significantly improved on both sides during follow-up (right: p = 0.003, left: p = 0.000). However, the median differences were not clinically relevant. Only two patients (2%) who improved on caloric testing, failed to reach the criteria for bilateral vestibulopathy at follow-up. Both patients had idiopathic bilateral vestibulopathy. At baseline, these patients did already not comply with the criteria for bilateral vestibulopathy based on the vHIT and/or torsion swing test. There was no significant change in the total DHI, EQ-5D-5 L VAS, or HADS scores. The EQ-5D-5 L index significantly increased (p = 0.034). No significant relationship could be determined between etiology and the evolution of vestibular function, quality of life, and symptoms. In conclusion, in the majority of bilateral vestibulopathy patients, vestibular function, health-related quality of life and symptoms did not show a clinically relevant improvement over time.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-92109-2.

Keywords: Bilateral vestibulopathy; Bilateral vestibular hypofunction; Bilateral vestibular loss; Bilateral vestibular areflexia; Vestibular implant; Vertigo; Balance; Vestibular testing; Caloric test; Video head impulse testing, VHIT; Rotatory chair testing; Torsion swing test; Dizziness handicap inventory

Subject terms: Auditory system, Epidemiology, Disability

Introduction

Bilateral vestibulopathy (BV) is a disabling disorder characterized by a significantly reduced or absent vestibular function bilaterally. BV can present with a broad spectrum of symptoms, such as unsteadiness, blurred vision during head movements (oscillopsia), and impaired spatial orientation1–4. It can lead to a decrease in physical and social activities and an increased risk of falling. Consequently, BV can negatively affect quality of life5,6. BV is a heterogeneous condition with various underlying etiologies, such as toxic, infectious, traumatic, congenital, genetic, Meniere’s disease, etc7–9. In approximately 30–50% of patients, the etiology remains idiopathic7,8. Idiopathic cases are often associated with migraine8. BV can be diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria of the Bárány Society. These criteria require both symptoms (unsteadiness and oscillopsia), and a bilaterally reduced or absent lateral semicircular canal function. The latter should be documented by the caloric test (slow phase caloric-induced nystagmus for stimulation with warm and cold water on each side < 6°/s), or Video Head Impulse Test (bilateral vestibulo-ocular reflex gain < 0.6), or rotatory chair testing (vestibulo-ocular reflex gain ≤ 0.1 and/or a phase lead ≥ 15degrees)10,11.

Unfortunately, disabling symptoms persist in most of the patients, despite vestibular rehabilitation12,13. Therefore, a vestibular implant is currently being developed to (partially) restore vestibular function. A vestibular implant stimulates the vestibular nerve, using surgically implanted electrodes near the vestibular nerve branches. It was previously demonstrated that the vestibular implant is able to (partially) restore vestibulo-ocular and vestibulo-collic reflexes, decrease oscillopsia, and improve gait and quality of life14–18. Currently, vestibular implantation is performed in patients with almost no residual vestibular function19, as electrode insertion could lead to a loss of residual vestibular function20. However, a delay in implantation and consequently delayed stimulation of the vestibular nerves, might lead to atrophy of the cortical representation of the non-used systems and a cortical reorganization, which might decrease the efficacy of the implant21. Knowledge about the natural evolution of vestibular function of BV patients over time could help to define the best timing of vestibular implantation.

Currently, little is known about the evolution of vestibular function and symptoms in BV patients over time. Only a few studies were published on this topic22–24. A case study investigating vestibular function and symptoms over time described complete or partial recovery in some cases22. On the contrary, two other studies demonstrated that the prognosis of BV is poor: vestibular function does not improve in the majority of BV patients (≥ 80%)23,24. However, these studies were conducted before the diagnostic criteria of BV were published. This implies that different BV criteria were used for patient inclusion. Results of these studies might therefore not directly be translated to the BV population, as it is currently defined.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the natural evolution of vestibular function, health-related quality of life, and symptoms over time, in a large cohort of BV patients, diagnosed according to the Bárány Society criteria. More specifically, this study aims to investigate if patients with BV can improve to a normal to near-normal vestibular function, contraindicating vestibular implantation.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

This cross-sectional study was performed at a tertiary referral center (Maastricht University Medical Center). Patients were included if they met the diagnostic criteria for BV established by the Bárány Society10. All patients who had at least two vestibular examinations at the same center, at different time points were included. Patients below the age of 18 years and patients who were using vestibulo-suppressive medication were excluded. All patients were counseled at the first presentation to move a lot and physiotherapy was proposed. It was not reported whether a patient did actually perform vestibular exercises or not, and if so at which time point.

Vestibular testing

Vestibular testing included the caloric test, video Head Impulse Test (vHIT), and torsion swing test. Testing paradigms were described elsewhere25–27. In short, the caloric test involved bi-thermal caloric irrigations (44◦C and 30◦C) with a volume of at least 250 ml of water (Variotherm Plus device, Atmos Medizin Technik GmbH, Lenzkirch, Germany). The maximum peak slow phase eye velocity at the culmination phase (◦/s) was measured using electronystagmography (KingsLab 1.8.1, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands). Video Head Impulse Testing of the lateral semicircular canals was performed using Otometrics (GN Otometrics, Taastrup, Denmark) or EyeSeeCam (Interacoustics, Munich, Germany). Head impulses were applied while the patient fixated on an earth-fixed target at a distance of 1.5 m. VHIT Vestibulo-ocular reflex gains (vHIT VOR gains) were calculated by the software of the systems. The torsion swing test was performed at 0.1 Hz with a peak velocity of 60° per second (Ekida GmbH, Buggingen, Germany). Eye movements were recorded with electronystagmography and the vestibulo-ocular reflex gain was calculated by Kingslab (see above). All tests were performed by trained personnel.

Questionnaires

Quality of life and symptoms were measured using the Dutch versions of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI)28, the Visual Analogue Score (VAS) and Index score of the EQ-5D-5 L29 and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)30. The DHI is a questionnaire that is commonly used in patients with vestibular complaints to quantify the impact of dizziness on daily life by measuring three subdomains: physical, functional, and emotional28. In the literature, a change of 11 points in the total DHI score is described as a minimally important change at two different time points31. The EQ-5D-5 L is used for measuring general health status. For this study, the EQ-5D-5 L index and the visual analog scale of the patient’s general health were used29. A value of 1 for the Index and 100 for the VAS score represents the best possible health status, and a score of 0 on both scores represents the worst imaginable health. No minimal clinically important difference in EQ-5D-5 L is established for vestibular disorders. Therefore, a change of > 0.25 on the index score or > 7.5 on the VAS score was chosen to be a clinically relevant change. This was based on the mean of the values found for other pathologies32–35. The HADS questionnaire reports the anxiety and depression levels of a patient. Anxiety and depression subscores of more than 8 point out a possible anxiety or depression30. A change of more than 2 points was defined as a relevant change, based on previous research in other fields36–39.

Data analysis

Patients’ age, gender, duration of symptoms at baseline assessment, BV etiology, results of vestibular tests (caloric test, vHIT, torsion swing test), the time between vestibular tests (follow-up duration), and outcomes of questionnaires were analyzed. When data from multiple assessments was available, the first and last obtained results were analyzed.

Outcome measures of the vestibular tests included the bi-thermal caloric maximum peak slow phase velocities at both sides, vHIT VOR gains (impulses to left and right separately analyzed), and torsion swing test VOR gain. Outcome measures of the questionnaires included: total DHI score, VAS and Index score of EQ-5D-5 L, and HADS anxiety and depression subscores.

During follow-up, BV patients were sometimes tested with different vHIT systems. In case the vHIT at follow-up was performed with multiple systems, the results of the initially used system were considered for the analyses. In the case follow-up vHIT was only performed with another system than initially used (18%, N = 11) vHIT results were compared between these two different systems. After all, it was previously demonstrated that no significantly different results were found between the vHIT of the EyeseeCam and Otometrics system in BV patients27.

Regarding questionnaires, not all patients completed all questionnaires at baseline and follow-up assessments. This resulted in missing data. Reasons for missing data included: (1) not all questionnaires were part of the standard clinical protocol at baseline assessment, and (2) mistakes were made when filling out the questionnaires (e.g., not all questions were answered, or more than one answer was given for a single question). Missing data were not imputed in the statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac. Armonk 2015, NY: IBM Corp.) and R statistics v4.3.3 (R Core Team (2024), R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics of patient characteristics and follow-up duration were performed. Median outcomes and interquartile ranges (IQR) of vestibular tests and questionnaires were calculated at baseline and follow-up assessment. Additionally, the median differences between baseline and follow-up assessments were investigated. The majority of the data was not normally distributed (according to the Shapiro-Wilk test), non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used for paired data, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed for the analysis of unpaired data. For continuous data, Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated. P-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the legislation and ethical standards on human experimentation in the Netherlands and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines. Ethical approval was obtained (METC: NL52768.068.15 and METC: NL72200.068.19) and patients provided written informed consent.

Results

Study population

Ninety-seven BV patients were included in this study. The median age at the time of baseline assessment was 56 years (IQR = 15 years, range = 19–76 years). Fifty-one patients were male (53%) and 46 patients were female (47%). The median time of vestibular symptoms at the time of baseline assessment was 4 years (IQR = 9 years, range = 0.25-61 years) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The median follow-up time between baseline and last vestibular assessment was 24 months (IQR = 39 months, range = 1-138 months) for the whole population (Suppl. Figure 2). Etiologies of BV patients included toxic/metabolic (n = 20, 21%), genetic (n = 13, 13%), infectious (n = 8, 8%), autoimmune (n = 6, 6%), Menière’s disease (n = 3, 3%), congenital/syndromal (n = 1, 1%), and idiopathic (n = 46, 47%). The idiopathic cases were further subdivided into purely idiopathic (n = 33, 34%), and idiopathic with associated vestibular migraine (n = 13, 13%).

Follow-up of vestibular function

The number of tested patients, median and IQR of all vestibular tests at baseline and follow-up testing, and the percentage of patients who changed from being diagnosed as BV based on a particular test are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Vestibular tests over time.

| Test | N | FU Time (m) | Baseline median (IQR) | Follow-up median (IQR) | P-value | Improved (n (%)) | Worse (n (%)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caloric R Caloric L |

96 | 24 (1-138) |

0.5(3) 0(3) |

0 (2) 0 (2) |

0.028 0.204 |

6 (6) 5 (5) |

3 (3) 6 (6) |

|

vHIT R vHIT L |

62 | 18 (1–66) |

0.20 (0.38) 0.24 (0.36) |

0.29 (0.33) 0.30 (0.40) |

0.003 0.000 |

4 (6) 7 (11) |

1 (2) 2 (3) |

| TS | 89 | 24 (1-138) | 0.05 (0.11) | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.017 | 6 (7) | 15 (17) |

Number of patients, median and IQR at baseline and follow-up, and number of patients who improved or got worse over time for each specific vestibular test. Patients who at baseline met the BV criteria for this specific test, but at follow-up did not comply with the BV criteria anymore were categorized as improved. When the specific test of a patient was not yet within the criteria for BV at baseline, but results deteriorated under the level of BV diagnosis at follow-up, the patient was categorized as worse.

N number of patients tested, m months.

Caloric test

Follow-up caloric testing was performed in 96 patients (99%). In one patient, caloric testing was not performed because of a tympanic membrane perforation.

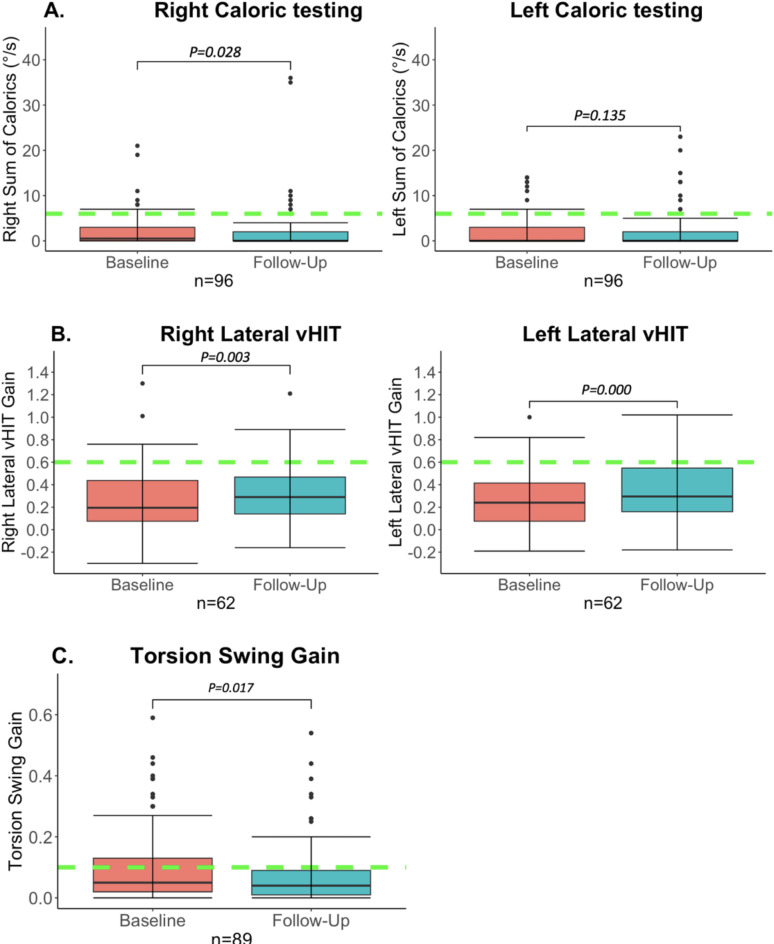

At baseline assessment, the median total caloric response (= sum of bi-thermal maximum peak slow phase velocity) was 0.5°/sec (IQR = 3°/sec, range 0–21) on the right side and 0 °/sec (IQR = 3°/sec, range 0–14) on the left side. Thirty-seven patients (39%) demonstrated a complete bilateral caloric areflexia already at baseline. On the right side, six patients (6%), who at baseline reached BV criteria (< 6°/sec), did not fulfill the criteria of BV at follow-up anymore. On the left side, this was seen in 5 patients (5%). Only two of those patients did not meet the diagnostic criteria of BV anymore, based on other vestibular tests. It should be noted that already at baseline assessment vHIT and torsion swing responses did not meet the diagnostic criteria in those two patients. At follow-up assessment, the median caloric response was 0°/sec (IQR = 2°/sec, range 0–20) on both sides. A complete bilateral caloric areflexia was found in 56 patients (58%). The median difference in caloric response between baseline and follow-up assessment was 0°/sec on both sides (right: IQR = 2°/sec, range= -12-35/ left: IQR = 1°/sec, range= -14-18). A Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that the median total caloric response significantly decreased over time on the right side (Z = -2.196, p = 0.028), but not on the left side (Z = -1.494, p = 0.135) as illustrated in Fig. 1a. More detailed information can be found in Supplementary Materials, Figs. 3, 4.

Fig. 1.

Vestibular test results over time. Baseline assessment versus follow-up. Follow-up represents the last available test of each patient. The whiskers represent the maximum values which are not outliers. The dots represent outliers (values that are more than 1.5 x IQR below Q1 or above Q3). The green dotted lines represent for each test the cut-off values used for diagnosing BV10. (A) Bithermal right- and left-sided caloric test results over time. This box plot demonstrates the significant overall reduction of the right sum of the slow phase eye velocity over time with a floor effect. On the left side, there was no significant difference during follow-up. However, on this side, the median was already 0°/sec at baseline. (B) Right- and left horizontal vHIT VOR gain over time. A significant improvement was found over time on both sides. Nevertheless, this improvement was very small and most likely not clinically relevant. (C) Torsion Swing test gain over time. A significant reduction of the torsion swing test gain over time was found.

Video head impulse test

Follow-up of vHIT testing of the lateral canals was performed in 62 patients (63%). In 36 patients, no vHIT was performed at baseline assessment, since it was not part of the standard clinical testing protocol at that time. The median follow-up time of vHIT was 18 months (IQR = 24 m, range = 1–66 m). At baseline assessment, the median vHIT VOR gains were 0.20 (IQR = 0.38, range=-0.14-1.3) and 0.24 (IQR = 0.36, range=-0.19-1) for impulses to the right and left, respectively. In 4 patients (6%) on the right side and 7 patients (11%) on the left side the vHIT VOR gains that were within BV criteria at baseline, did not comply anymore with the vHIT diagnostic criterion of BV at follow-up. Nevertheless, these patients were still diagnosed with BV based on the caloric test and/or torsion swing test results. At the follow-up assessment, the median vHIT VOR gains of the whole group for impulses to the right and left were 0.29 (IQR = 0.33, range= -0.16-1.21) and 0.30 (IQR = 0.40, range=-0.18-1.00) respectively (Fig. 1b). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed significantly higher median vHIT VOR gains bilaterally at follow-up compared to baseline assessment (Rightwards impulses: Z = 3.002, p = 0.003; Leftwards impulses: Z = 4.157, p = 0.000). However, in most patients, vHIT VOR gain differences were very small between baseline and follow-up assessment. The median differences in vHIT VOR gains were 0.05 (IQR = 0.16, range=-0.35-0.49) for impulses to the right and 0.09 (IQR 0.19, range=-0.36-0.43) for impulses to the left (Supplementary Materials, Figs. 5 and 6).

Torsion swing test

Follow-up of torsion swing testing was performed in 89 patients (92%). Missing baseline data was present in eight patients. The median follow-up time of torsion swing testing was 24 months (IQR = 38 months, range = 1-138). At baseline assessment, the median torsion swing test VOR gain was 0.05 (IQR = 0.11, range = 0-0.59). Six patients (7%) did not meet the torsion swing test diagnostic criterion of BV at follow-up. However, these patients were still diagnosed with BV based on the caloric test and/or vHIT results. At the follow-up assessment, the median torsion swing test VOR gain of the whole group was 0.04 (IQR = 0.08, range = 0-0.44), as illustrated in Fig. 1c. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that the median torsion swing test VOR gain significantly decreased over time (Z = -2.386, p = 0.017). More detailed information can be found in Supplementary Materials, Figs. 7 and 8.

Follow-up of health-related quality of life and symptoms

Table 2 presents the number of tested patients, the median and IQR of all questionnaires at baseline and follow-up testing, and the percentage of patients who had a significant change over time.

Table 2.

Quality of life and symptoms over time.

| Test | N | FU time (m) | Baseline median (IQR) | Follow-up median (IQR) | P-value | Improved (n (%)) | Worse (n (%)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total DHI | 69 | 19 (1–92) | 54 (24) | 56 (22) | 0.447 | 12 (17) | 10 (14) |

|

EQ-5D-5 L VAS EQ-5D-5 L index |

44 | 20 (1–92) |

65 (34) 0.66 (0.35) |

65 (26) 0.74 (0.36) |

0.556 0.034 |

15 (34) 5 (11) |

13 (30) 3 (7) |

|

HADS A HADS D |

77 | 19 (1–95) |

6 (6) 6 (8) |

6 (4.25) 5.5 (8) |

0.167 0.415 |

9 (12) 12 (16) |

21 (27) 20 (26) |

Number of patients, median and IQR at baseline and follow-up, and percentage of patients with a minimally important change on the questionnaires over time.

N number of patients tested, m months.

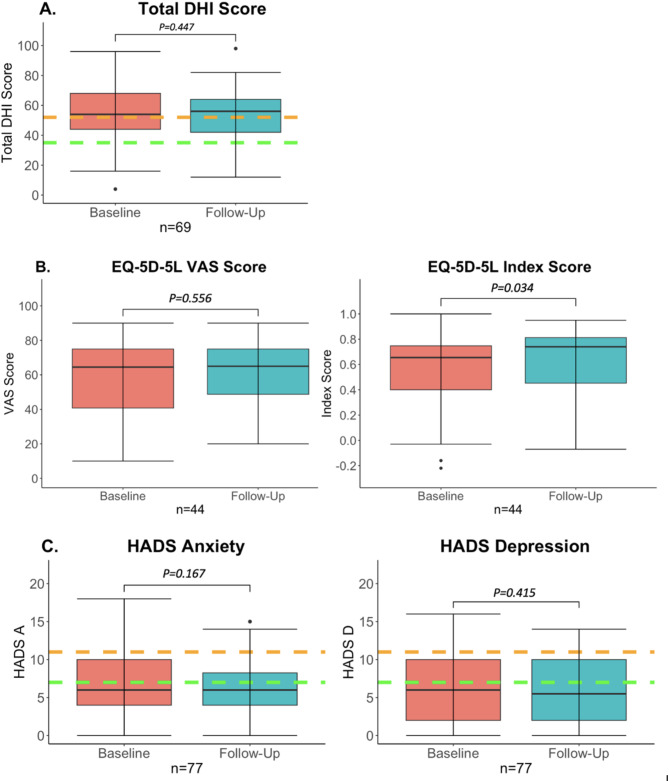

Dizziness handicap inventory

Sixty-nine patients (71%) completed the DHI at baseline and follow-up assessment. The median follow-up time of completed DHI questionnaires was 19 months (IQR = 22 months, range = 1–92). The median total score DHI score was 54 (IQR = 24, range = 4–84) at baseline and 56 (IQR = 22, range = 12–98) at follow-up assessment (Fig. 2a). The total DHI score did not significantly change over time in the study population (Z = =-0.844, p = 0.447). In 12 patients (17%) a clinically relevant increase of ≥ 11 points on the total DHI score was found at follow-up assessment. A decrease of 11 points was observed in 10 patients (14%) (Supplementary Materials Figs. 9, 10).

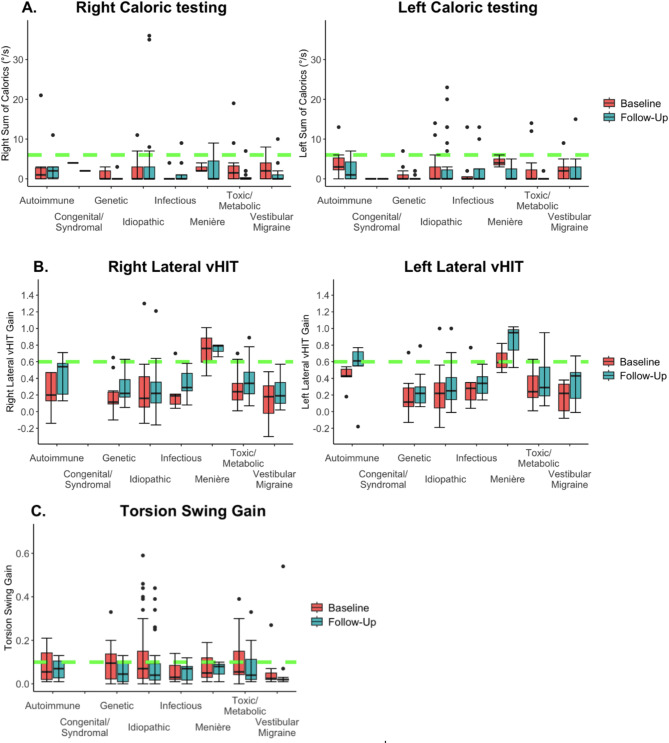

Fig. 3.

Vestibular tests over time grouped by etiology. The whiskers represent the maximum values which are not outliers. The dots represent outliers (values that are more than 1.5 x IQR below Q1 or above Q3). Follow-up represents the last available test of the patient. The green dotted lines represent for each test the cut-off values used for diagnosing BV10. (A) Bithermal right- and left-sided caloric test results. No significant difference was found between baseline and follow-up when studying different etiologies separately. (B) Right- and left horizontal vHIT VOR gain. No significant difference was found when studying the difference between baseline and follow-up in different etiology groups. The vHIT gain was especially high at both baseline and follow-up in patients with Menière’s disease. (C) Torsion Swing test gain. No significant difference was found when studying the difference between baseline and follow-up in different etiology groups.

EQ-5D-5 L

The EQ-5D-5 L was completed by 44 patients (45%) at baseline and follow-up assessment. The median follow-up time of the EQ-5D-5 L was 20 months (IQR = 19 months, range = 1–92). The median VAS score was 65 at both baseline and follow-up (IQR = 34 and 26, range = 10–90 and 20–90, respectively). This was not significantly different (Z = -0.588, p = 0.556) (Fig. 2b). The median Index score was 0.66 (IQR = 0.35, range=-0.22-0.91) at baseline and 0.74 (IQR = 0.36, range=-0.07-0.95) at follow-up assessment. This improvement was significant (Z = -2.117, p = 0.034) (Fig. 2b). Regarding the VAS score, a clinically relevant increase (difference of more than 7.5 points) was found in 15 patients (34%). A clinically relevant decrease was seen in 13 patients (30%). Regarding the index score, a clinically relevant increase was found in five patients (11%). Interestingly, only in two of those five patients, the VAS score increased as well. In two patients the VAS decreased and in one it remained the same. A clinically relevant decrease in the index score was seen in three patients (7%). These three patients all reported improved VAS scores (Supplementary Materials Figs. 11, 12).

HADS anxiety and depression subscores

Seventy-seven patients (79%) completed the HADS at baseline and follow-up assessment. The median follow-up time of completed HADS questionnaires was 19 months (IQR = 25 months, range = 1–95). Regarding the HADS anxiety subscores, the median anxiety subscore was 6 (IQR = 6, range = 0–18) at baseline and 6 (IQR = 4.25, range = 0–16) at follow-up assessment (Fig. 2c). The anxiety subscore did not significantly change over time in the study population (Z =-1.382, p = 0.167). Regarding the HADS depression subscores, the median depression subscore was 6 (IQR = 8, range = 0–16) at baseline and 5.5 (IQR = 8, range = 0–14) at follow-up assessment. The depressions subscore did also not significantly differ over time in the study population (Z =-0.816, p = 0.415). A minimal clinical difference (2 points) in HADS anxiety subscores was found in 30 patients: nine patients improved (12%) and 21 patients became worse over time (27%). Regarding the HADS depression subscores, 12 patients improved by more than 2 points (16%), and in 20 patients (26%) their scores decreased by more than 2 points over time (Supplementary Materials Figs. 13, 14).

Influence of etiology on vestibular function, quality of life, and symptoms

Figure 3a–c presents vestibular test results (caloric test, vHIT, torsion swing test) at baseline and follow-up assessment, divided into etiology categories. There were no significant differences between etiologies regarding the evolution over time of the caloric function (right; p = 0.117, left: p = 0.165), vHIT (right: p = 0.182, left: p = 0.753), or torsion swing gain (p = 0.929). Furthermore, no significant effects of etiology were found on the evolution over time of DHI Total scores (p = 0.488), EQ-5D-5 L VAS (p = 0.397) and Index (p = 0.181) scores, and HADS Anxiety (p = 0.268) or depression (p = 0.606) scores. The only two patients that did not comply anymore with the diagnostic criteria of BV at follow-up assessment, were previously diagnosed with idiopathic BV.

Fig. 2.

Questionnaire scores over time. Baseline assessment versus follow-up. Follow-up represents the last available questionnaire of each patient. The whiskers represent the maximum values which are not outliers. The dots represent outliers (values that are more than 1.5 x IQR below Q1 or above Q3). (A) Total DHI scores over time. The area under the green dotted line represents mild impairment. The area between the green and orange dotted lines represents moderate impairment. The area above the orange dotted line represents severe impairment. No significant increase in DHI total score was found over time. (B) EQ-5D-5 L VAS (right) and Index scores (left) over time. The VAS score remained stable, but the index score significantly improved over time. (C) HADS anxiety and depression scores over time. The area under the green dotted line represents ‘no anxiety or depression’. The area between the green and orange dotted lines represents ‘possible anxiety or depression’. The area above the orange dotted line represents ‘probable anxiety or depression’. No significant differences were found between baseline and follow-up.

Discussion

This study investigated the natural evolution of vestibular function, health-related quality of life, and symptoms over time, in a large cohort of BV patients, diagnosed according to current criteria.

Follow-up of vestibular function

After a median follow-up time of 24 months, in 98% of the patients, the vestibular function remained within the criteria for BV. This implies that in the majority of BV patients, the vestibular function does not improve over time. This is also congruent with the most recent literature24. In the current study, only two patients (2%) who improved on caloric testing, failed to reach the criteria for BV at follow-up. Both patients had idiopathic BV. At baseline, these patients did already not comply with the criteria for BV based on the vHIT and/or TS test. Both tests showed normal/near-to-normal values at the first presentation. These findings might imply fluctuating vestibular function, or measurement artifacts in these two patients42. This highlights the importance of confirming the diagnosis of BV on more than one vestibular test or repeating vestibular testing, before planning invasive procedures such as vestibular implantation19.

Concerning the absolute values of the vestibular tests, the SPV of the caloric test on the right side and torsion swing gain significantly decreased over time. The median SPV of the caloric test on the left side showed no significant difference but was already 0°/sec at baseline. The vHIT gain on both sides, on the contrary, increased over time. Overall the changes on vestibular testing were small, not clinically relevant and there might be also some influence of the test-retest variability. For example, the median differences in the vHIT gain between baseline and follow-up were very small (0.05 on the right and 0.09 on the left). Patients in which the vHIT gain increased above the cut-off value of 0.6, were still diagnosed with BV based on the other vestibular tests. This small VOR gain increase might (partially) be explained by a possible increase in covert saccades40. These saccades are not always reliably detected by vHIT software, challenging VOR gain calculation41. It was beyond the scope of the present study to investigate this phenomenon in detail.

Follow-up of health-related quality of life and symptoms

No significant change over time was found for the total DHI total score, EQ-5D-5 L VAS, and both HADS anxiety and depression subscales. Surprisingly, a significant improvement in the EQ-5D-5 L Index score was found over time. Patients who showed a potentially clinically relevant improvement of the EQ-5D-5 L Index score, however, often reported a decrease in VAS score. In some patients, the improved quality of life might (partially) be related to a phenomenon called ‘adaptation’: in a chronically changed situation, patients might change their view of what they consider normal. Some questionnaires might capture this aspect differently than other questionnaires. This could possibly contribute to the discrepancies found between the EQ-5D-5 L index and the other questionnaires3. Some patients reported a decreased quality of life. This could be related to many factors, including the progression of the disease itself and the lack of further treatment options. Additionally, non-vestibular related factors could play a role, e.g. other co-morbidities and their social environment. It should also be taken into account that the median age distribution at baseline assessment was very large (19–76 years). The quality of life and demands of a patient of his/her vestibular system might also depend on the patient’s age.

Overall, these findings are congruent with the literature. It was previously42 demonstrated that BV patients had the least favorable outcome of all vestibular pathologies43. Furthermore, most questionnaires do not seem to capture the whole spectrum of symptoms related to BV. Therefore, The Bilateral Vestibulopathy Questionnaire (BVQ) was recently developed to overcome this limitation44.

Influence of etiology on vestibular function, health-related quality of life, and symptoms

In this study, no significant relationship could be determined between etiology and the evolution of vestibular function, health-related quality of life, and symptoms. The only 2 patients that were not anymore classified as BV at follow-up, however, were idiopathic. This is also in line with previous literature24.

Taking all results into account, it can be concluded that on a group level, vestibular function, health-related quality of life, and symptoms of patients diagnosed with BV, did not significantly improve over time. Especially vestibular function did never show any clinically relevant improvement, when the diagnosis was based on more than one vestibular test, and when BV was not of idiopathic origin. This means that in those patients, no improvement is to be expected that could contraindicate early vestibular implantation. After all, an early intervention might be beneficial. Delaying vestibular stimulation could potentially lead to vestibular deprivation, decreasing the efficacy of the stimulation over time, as with cochlear implantation45.

Limitations

Currently, the literature is unclear about criteria to determine significant/clinically relevant improvements/deteriorations of vestibular test results. This is a challenging topic, since vestibular test results differ between laboratories and reproducibility can be hindered by measurement artifacts10,42. Research concerning test-retest variability of vestibular tests focused on patients with normal vestibular function, and not on patients with poor vestibular function46,47. It is, however, known that vestibular tests are especially susceptible to artifacts when the vestibular function is very low48. This limitation was mitigated as much as possible, by using trained personnel and using the same laboratory with its own normative data.

Additionally, the retrospective nature of this study implied that follow-up times differed between patients. Nevertheless, since most patients did not show any significant improvement, the timing of follow-up most likely did not play a significant role. Lastly, in the current study, the function of the otolith organ was not tested, as it is not part of the standard clinical vestibular investigation protocol and therefore, it was not available at baseline testing. It is also currently not part of the criteria for BV of the Barany society. The addition of information about cVemp testing would have been an interesting addition, however, it was previously published that the vHIT and caloric testing seemed to be more sensitive for measuring vestibular impairment and the TS is the most suitable for measuring residual vestibular function25. Moreover, it is still not clear if the otolith organs can be selectively tested with present-day vestibular tests49. Nevertheless, it is recommended to perform cVemp testing before and after vestibular implantation, to study the potential effects of vestibular implantation on this specific test.

Conclusion

In the majority of BV patients, vestibular function, health-related quality of life, and symptoms did not show a clinically relevant improvement over time, especially when the diagnosis was based on more than one vestibular test and when BV was not of idiopathic origin.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

EL collected and analyzed the existing data, drafted the manuscript, and designed the figures. LVS and FL performed the vestibular tests and gathered the questionnaires during follow-up. LVS and RvdB designed the study. SD aided in analyzing the results and statistical analysis. NV and CD supervised the work of EL. All authors discussed the results, gave critical feedback and contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding

EL is funded by the Klinische Onderzoeks- en OpleidingsRaad (KOOR) of the University Hospitals Leuven. NV received a senior clinical investigator fund 1804816 N from the Flemish Research Foundation. The authors declare that LVS and FL received financial support from MED-EL (Innsbrück, Austria) for their research. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information filesIf further information is needed the corresponding author (elke.loos@kuleuven.be) can be contacted.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects for additional vestibular testing (for studies METC: NL52768.068.15 and METC: NL72200.068.19), although due to the retrospective nature of the study the Maastricht medical ethical committee waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

E. Loos and L. Van Stiphout contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Starkov, D., Strupp, M., Pleshkov, M., Kingma, H. & van de Berg, R. Diagnosing vestibular hypofunction: an update. J. Neurol.268, 377–385. 10.1007/s00415-020-10139-4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucieer, F. et al. Full spectrum of reported symptoms of bilateral vestibulopathy needs further investigation-A systematic review. Front. Neurol.9, 352. 10.3389/fneur.2018.00352 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucieer, F. M. P. et al. Bilateral vestibulopathy: beyond imbalance and oscillopsia. J. Neurol.267 (Suppl 1), 241–255. 10.1007/s00415-020-10243-5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paredis, S. et al. DISCOHAT: an acronym to describe the spectrum of symptoms related to bilateral vestibulopathy. Front. Neurol.12, 771650. 10.3389/fneur.2021.771650 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobbels, B. et al. Prospective cohort study on the predictors of fall risk in 119 patients with bilateral vestibulopathy. PLoS ONE15 (3), e0228768. 10.1371/journal.pone.0228768 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward, B. K., Agrawal, Y., Hoffman, H. J., Carey, J. P. & Della Santina, C. C. Prevalence and impact of bilateral vestibular hypofunction: results from the 2008 US National health interview survey. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.139 (8), 803–810. 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3913 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zingler, V. C. et al. Causative factors and epidemiology of bilateral vestibulopathy in 255 patients. Ann. Neurol.61 (6), 524–532. 10.1002/ana.21105 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucieer, F. et al. Bilateral vestibular hypofunction: insights in etiologies, clinical subtypes, and diagnostics. Front. Neurol.7, 26. 10.3389/fneur.2016.00026 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zingler, V. C. et al. Causative factors, epidemiology, and follow-up of bilateral vestibulopathy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1164 505-8. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03765.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Strupp, M. et al. Bilateral vestibulopathy: diagnostic criteria consensus document of the classification committee of the Bárány society. J. Vestib. Res.27 (4), 177–189. 10.3233/ves-170619 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strupp, M. et al. Erratum to: Bilateral vestibulopathy: Diagnostic criteria consensus document of the classification committee of the Bárány society. J. Vestib. Res.33 (1), 87. 10.3233/VES-229002 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Kingma, H. et al. Vibrotactile feedback improves balance and mobility in patients with severe bilateral vestibular loss. J. Neurol.266 (Suppl 1), 19–26. 10.1007/s00415-018-9133-z (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porciuncula, F., Johnson, C. C. & Glickman, L. B. The effect of vestibular rehabilitation on adults with bilateral vestibular hypofunction: a systematic review. J. Vestib. Res.22 (5–6), 283–298. 10.3233/VES-120464 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fornos, A. P. et al. Cervical myogenic potentials and controlled postural responses elicited by a prototype vestibular implant. J. Neurol.266 (Suppl 1), 33–41. 10.1007/s00415-019-09491-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez Fornos, A. et al. Artificial balance: restoration of the vestibulo-ocular reflex in humans with a prototype vestibular neuroprosthesis. Front. Neurol.5, 66. 10.3389/fneur.2014.00066 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guinand, N. et al. Restoring visual acuity in dynamic conditions with a vestibular implant. Front. Neurosci.10 577. 10.3389/fnins.2016.00577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Chow, M. R. et al. Posture, gait, quality of life, and hearing with a vestibular implant. N. Engl. J. Med.384 (6), 521–532. 10.1056/NEJMoa2020457 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stultiens, J. J. A. et al. The next challenges of vestibular implantation in humans. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol.24 (4), 401–412. 10.1007/s10162-023-00906-1 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Berg, R. et al. The vestibular implant: Opinion statement on implantation criteria for research. J. Vestib. Res.30 (3), 213–223. 10.3233/VES-200701 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Golub, J. S. et al. Prosthetic implantation of the human vestibular system. Otol. Neurotol.35 (1), 136–147. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000003 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun, Z. et al. Cortical reorganization following auditory deprivation predicts cochlear implant performance in postlingually deaf adults. Hum. Brain Mapp.42 (1), 233–244. 10.1002/hbm.25219 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vibert, D., Liard, P. & Häusler, R. Bilateral idiopathic loss of peripheral vestibular function with normal hearing. Acta Otolaryngol.115 (5), 611–615. 10.3109/00016489509139375 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baloh, R. W., Enrietto, J., Jacobson, K. M. & Lin, A. Age-related changes in vestibular function: a longitudinal study. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.942, 210–219. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03747.x (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zingler, V. C. et al. Follow-up of vestibular function in bilateral vestibulopathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry79 (3), 284–288. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.122952 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Stiphout, L. et al. Patterns of vestibular impairment in bilateral vestibulopathy and its relation to etiology. Front. Neurol.13, 856472. 10.3389/fneur.2022.856472 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Stiphout, L. et al. Bilateral vestibulopathy decreases self-motion perception. J. Neurol.269 (10), 5216–5228. 10.1007/s00415-021-10695-3 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Dooren, T. S. et al. Comparison of three video head impulse test systems for the diagnosis of bilateral vestibulopathy. J. Neurol.267 (Suppl 1), 256–264. 10.1007/s00415-020-10060-w (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson, G. P. & Newman, C. W. The development of the dizziness handicap inventory. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.116 (4), 424–427. 10.1001/archotol.1990.01870040046011 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janssen, M. F., Bonsel, G. J. & Luo, N. Is EQ-5D-5L better than EQ-5D-3L? A head-to-head comparison of descriptive systems and value sets from seven countries. Pharmacoeconomics36 (6), 675–697. 10.1007/s40273-018-0623-8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.67 (6), 361–370. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamber, A. L., Wilhelmsen, K. T. & Strand, L. I. Measurement properties of the dizziness handicap inventory by cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. Health Qual. Life Outcomes7, 101. 10.1186/1477-7525-7-101 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Del Corral, T. et al. Minimal clinically important differences in EQ-5D-5L index and VAS after a respiratory muscle training program in individuals experiencing long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms. Biomedicines11 (9). 10.3390/biomedicines11092522 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Tsai, A. P. Y. et al. Minimum important difference of the EQ-5D-5L and EQ-VAS in fibrotic interstitial lung disease. 76 (1), 37–43. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-214944 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Zheng, Y., Dou, L., Fu, Q. & Li, S. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference of EQ-5D-5L in patients with coronary heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention: A longitudinal study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.10, 1074969. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1074969 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bilbao, A. et al. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: reliability, validity and responsiveness. Qual. Life Res.27 (11), 2897–2908. 10.1007/s11136-018-1929-x (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan, K. S. et al. Distribution-based estimates of minimal important difference for hospital anxiety and depression scale and impact of event scale-revised in survivors of acute respiratory failure. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry42, 32–35. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.07.004 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puhan, M. A., Frey, M., Büchi, S. & Schünemann, H. J. The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual. Life Outcomes6, 46. 10.1186/1477-7525-6-46 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wynne, S. C. et al. Anxiety and depression in bronchiectasis: response to pulmonary rehabilitation and minimal clinically important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Chron. Respir. Dis.17, 1479973120933292. 10.1177/1479973120933292 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Longo, U. G. et al. Establishing the minimum clinically significant difference (MCID) and the patient acceptable symptom score (PASS) for the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in patients with rotator cuff disease and shoulder prosthesis. J. Clin. Med.12 (4). 10.3390/jcm12041540 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Mantokoudis, G. et al. Adaptation and compensation of vestibular responses following superior canal dehiscence surgery. Otol. Neurotol.37 (9), 1399–1405. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001196 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Dooren, T. et al. Suppression head impulse test (SHIMP) versus head impulse test (HIMP) when diagnosing bilateral vestibulopathy. J. Clin. Med.1110.3390/jcm11092444 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.van de Berg, R., van Tilburg, M. & Kingma, H. Bilateral vestibular hypofunction: challenges in establishing the diagnosis in adults. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec.77 (4), 197–218. 10.1159/000433549 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Obermann, M. et al. Long-term outcome of vertigo and dizziness associated disorders following treatment in specialized tertiary care: the dizziness and vertigo registry (DiVeR) study. J. Neurol.262 (9), 2083–2091. 10.1007/s00415-015-7803-7 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Stiphout, L. et al. Construct validity and reliability of the bilateral vestibulopathy questionnaire (BVQ). Front. Neurol.14, 1221037. 10.3389/fneur.2023.1221037 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fallon, J. B., Irvine, D. R. & Shepherd, R. K. Cochlear implants and brain plasticity. Hear. Res.238 (1–2), 110–117. 10.1016/j.heares.2007.08.004 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Money-Nolan, L. E. & Flagge, A. G. Factors affecting variability in vestibulo-ocular reflex gain in the video head impulse test in individuals without vestibulopathy: A systematic review of literature. Front. Neurol.14, 1125951. 10.3389/fneur.2023.1125951 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhansali, S. A. & Honrubia, V. Current status of electronystagmography testing. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.120 (3), 419–426. 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70286-X (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hermann, R. et al. Bilateral vestibulopathy: vestibular function, dynamic visual acuity and functional impact. Front. Neurol.9 (555). 10.3389/fneur.2018.00555 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Kjærsgaard, J. B., Hougaard, D. D. & Kingma, H. Thirty years with cervical vestibular myogenic potentials: a critical review on its origin. Front. Neurol.15, 1502093. 10.3389/fneur.2024.1502093 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information filesIf further information is needed the corresponding author (elke.loos@kuleuven.be) can be contacted.