Abstract

Objective:

To describe patterns of cancer treatment and live birth outcomes that followed a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy.

Study Design:

The Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Horizon Study is an observational study evaluating outcomes in survivors of the five most common types of cancer in this age group (15–39 years old). Of the 23,629 individuals identified diagnosed with breast, lymphoma, thyroid, melanoma, or gynecological cancer in North Carolina (2000–2015) and California (2004–2016), we identified 555 live births to individuals who experienced cancer diagnosis during pregnancy. Births to individuals diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy were matched ∼1:5 on maternal age and year of delivery to live births to individuals without a cancer diagnosis (N = 2,667). Multivariable Poisson regression was used to compare birth outcomes between pregnancies affected by a cancer diagnosis and unaffected matched pregnancies.

Results:

Cancer diagnosis during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery (prevalence ratio [PR] 2.70; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.24, 3.26); very preterm delivery (PR 1.74; 95% CI 1.12, 2.71); induction of labor (PR 1.48; 95% CI 1.27, 1.73); low birth weight (PR 1.97; 95% CI 1.55, 2.50); and cesarean delivery (PR 1.18; 95% CI 1.04, 1.34) but not associated with low Apgar score (PR 0.90; 95% CI 0.39, 2.06). In our sample, 41% of patients received chemotherapy, half of whom initiated chemotherapy during pregnancy, and 86% received surgery, 58% of whom had surgery during pregnancy. Of the 19% who received radiation, all received radiation treatment following pregnancy.

Conclusion:

We identified an increased risk of birth outcomes, including preterm and very preterm delivery, induction of labor, low birth weight, and cesarean delivery, to those experiencing a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy. This analysis contributes to the available evidence for those experiencing a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy.

Keywords: pregnancy-associated cancer, pregnancy outcomes, chemotherapy in pregnancy, cancer treatment in pregnancy

Introduction

Pregnancy-associated cancer (PAC) is often defined as any cancer diagnosis during pregnancy or within one year postpartum.1–3 Although rare, the incidence of PAC has been increasing over time, from a rate of 1 in 2,000 pregnancies in 1964 to 1 in 1,000 pregnancies in 2000.1,4,5 More recent studies have reported rates of PAC ∼1.5 per 1,000 in Canada in 2015 and in Switzerland in 2017.6,7 This increase is thought to be due to improvements in cancer detection technology as well as the increasing average maternal age as individuals delay childbearing.8,9 Unfortunately, the United States does not yet have systems in place to link pregnancy and cancer information at the national level.10 Additionally, the overall rare incidence of PAC, coupled with the inability to perform large clinical trials examining the effects of cancer treatment in pregnancy, has resulted in a shortage of evidence regarding birth outcomes after cancer diagnosis.11

Research on specific cancer types diagnosed during pregnancy is often descriptive, with most studies focusing on the effect of the pregnancy on the cancer rather than the effect of the cancer on the pregnancy.8 Of the studies that have evaluated adverse birth outcomes, many have included cancers diagnosed during and after pregnancy, the latter of which often comprise the majority of the sample.2,3,12 The small proportion of cancers diagnosed during pregnancy when compared with those diagnosed during the postpartum period creates challenges to providing evidence specific for women who are diagnosed during pregnancy.8 Although a cancer diagnosis during the postpartum period remains devastating, treatment decisions are often more straightforward without the need to account for the developing fetus, and birth outcomes are not affected by cancer treatment.

Few population-based studies have been conducted in the United States evaluating the effect of a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy on adverse pregnancy outcomes. Among 3,168,911 California deliveries during 1992–1997, 2,247 individuals with PAC were identified. Deliveries to those with a PAC had higher age-adjusted odds ratios (OR) for cesarean delivery (OR 1.4), preterm birth (OR 2.0), and low birth weight (OR 2.6) compared with those without, although notably, this study includes those diagnosed with cancer up to 12 months postpartum.3

A recent retrospective cohort study performed in Texas identified 1,271 live births after cancer diagnosis during pregnancy from 1999 to 2015.13 The study reported an increased prevalence of cesarean delivery, preterm and very preterm delivery, low birth weight infants, and low Apgar scores of infants among pregnancies affected by cancer diagnosis when compared with those without. Receipt of chemotherapy was associated with an 82% higher prevalence of preterm birth.13 In international settings, cancer diagnosis during pregnancy has also been associated with increased risk of intrauterine growth restriction, small for gestational age infants, preterm delivery, and delivery via cesarean section, although these results have not been consistent, possibly secondary to small sample sizes or differing sample populations.9,14,15

The goal of this analysis is to describe birth outcomes following a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy in a U.S. population-based setting. We also describe distribution of cancer diagnoses by trimester of pregnancy and patterns of timing of cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

This analysis was conducted within the Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Horizon study, an investigation of birth outcomes among AYA individuals diagnosed with cancer at ages 15–39 years. Study design and population characteristics are described elsewhere.16 Briefly, female individuals were diagnosed with in situ or invasive breast cancer, or invasive thyroid, melanoma, lymphoma, or gynecological cancers (including cervical, uterine, and ovarian cancer) in North Carolina (2000–2015) and the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) and Southern California (KPSC) health systems (2004–2016). In North Carolina, records from the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry (NCCCR) were linked to statewide birth certificate files from the North Carolina Vital Records at the North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics by the University of North Carolina Cancer Information Population Health Resource (CIPHR), which links NCCCR data with public and private payer administrative insurance claims to incorporate cancer treatment information.17 North Carolina Birth Certificate data, including method of delivery and events of labor and delivery, have previously been validated.18 In California, cancer diagnoses during pregnancy and subsequent birth outcomes were identified from KPNC- and KPSC-specific tumor and birth registries. KPNC and KPSC are the two largest sites of the Cancer Research Network, funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and report to the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer registries.19,20 Their pregnancy databases and birth registries have previously been estimated to capture 99% of deliveries, and associated birth outcomes were identified through electronic health record data and ICD codes.16,21 As our cohort was identified through birth certificate data and birth registries, pregnancies that ended in miscarriage or termination are not captured. This study was approved by the University of North Carolina, KPNC, and KPSC institutional review boards with a waiver of informed consent.

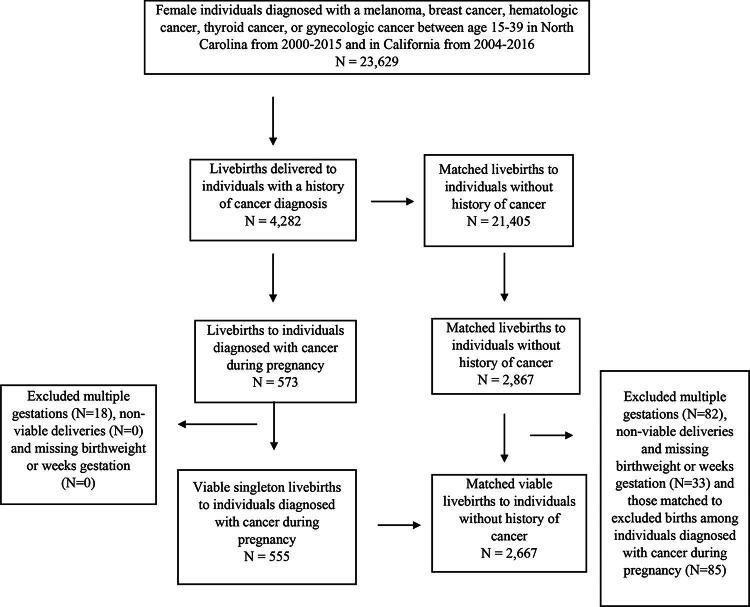

Within each study site, births were matched 1:5 to noncancer births on maternal age (by year of age at delivery), and year of delivery, identified from the original matched sample from the Horizon study.14 From our sample of live births following cancer diagnosis during pregnancy (N = 573) and the corresponding noncancer births (N = 2,867), we excluded births from multiple gestation pregnancies (i.e., twins, triplets; N = 18 cancer, 82 noncancer) as multiple gestations may introduce bias, and those at <23 weeks gestation or <500 g as nonviable births. We also excluded those missing birthweight or weeks of gestation (N = 0 cancer, 33 noncancer) given inability to perform thorough analysis without these variables (Fig. 1). In the final sample, <11 records were missing information on receipt of chemotherapy, date of chemotherapy receipt, or information on radiation therapy and were excluded from descriptive analyses of cancer treatment receipt.

FIG. 1.

Flow chart of inclusion and exclusion criteria of sample of 555 live births to 555 individuals diagnosed with melanoma, breast, thyroid, lymphoma, or gynecological cancer during pregnancy, matched ∼5:1 to 2,667 noncancer births on maternal age and year of birth.

Cancer characteristics, including cancer type, age at diagnosis, stage, first course of cancer treatment, and date of treatment initiation, were obtained from the NCCCR and the KPNC and KPSC cancer registries. To evaluate treatment that could potentially affect a developing pregnancy (i.e., gynecological surgery or pelvic radiation), surgery treatment data were obtained for gynecological cancers, receipt of radiation therapy was obtained for lymphoma and gynecological cancers, and chemotherapy treatment data were obtained for all cancers. Chemotherapy information from the NCCCR has previously been validated with a sensitivity of 86%.22 Among live births, information on maternal marital status, maternal parity (number of prior livebirths), timing of initiation of prenatal care, gestational age at delivery, birth weight, infant sex, mode of delivery, induction of labor, and neonatal Apgar score was obtained from North Carolina birth certificate files and KPNC and KPSC birth records. We defined the following adverse birth outcomes: preterm birth (delivery occurring at <37 weeks of gestation), very preterm birth (delivery occurring <34 weeks gestation), low birth weight (<2,500 g at delivery), small for gestational age (a birth weight of <10th percentile for gestational age and sex-specific nomogram),23 and low Apgar score (<7 at 5 minutes of life).

Descriptive statistics were used to tabulate cancer treatment initiation by trimester of pregnancy. Our sample was limited to live births; therefore, to evaluate the effect of missing cancer diagnoses early in pregnancy due to subsequent termination or miscarriage, we examined the distribution of cancer diagnoses by trimester of pregnancy. To compare the prevalence of birth outcomes between exposed pregnancies and the matched comparison group, we estimated prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using modified Poisson regression models with robust error variance.24 Initial models accounted only for matching factors (maternal age and year of delivery). Due to small sample sizes, both factors were treated categorically (maternal age <30, ≥30 years; year of delivery <2008, ≥2008). Fully adjusted models additionally included the following covariates: race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other race and ethnicity, Hispanic any race, and unknown/missing), marital status (married, not married, and unknown/missing), parity (number of prior livebirths), and timing of initiation of prenatal care (no prenatal care, early [first trimester], late [second or third trimester], missing). Prior studies show an increased risk of preterm birth with chemotherapy treatment during pregnancy, although evidence on whether this observed association is due to spontaneous labor or planned delivery to facilitate chemotherapy treatment is mixed.2,15,25 We therefore examined the prevalence of preterm birth, as well as induction of labor and cesarean delivery according to chemotherapy receipt/timing (during vs. after pregnancy). Any birth that was not an induced or cesarean delivery was considered to be a spontaneous vaginal delivery. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

We identified a total of 4,282 live births to individuals with AYA cancer, including 573 live births that followed a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy. After applying exclusion criteria, our final “exposed” cohort consisted of 555 singleton live births to individuals that were diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy (362 from the North Carolina data and 193 from KPNC or KPSC), and a comparison “unexposed” group consisted of 2,667 singleton live births that were not exposed to a maternal cancer diagnosis (Fig. 1). Median maternal age at delivery after a cancer diagnosis was 32 years. Our sample was largely non-Hispanic White (61% of births following a cancer diagnosis vs. 48% without) and married (68% cancer vs. 66% without). Most initiated prenatal care in the first trimester (81% cancer vs. 77% without). Mean gestational weeks at delivery was lower in births after cancer compared with those not exposed to cancer (37.6 weeks vs. 38.6 weeks) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Obstetric Characteristics of Individuals with Cancer Diagnosis During Pregnancy and an Age- and Birth Year-Matched Sample of Individuals Without Cancer During Pregnancy

| Individuals with cancer diagnosis in pregnancy N = 555 |

Matched individuals with pregnancies without cancer diagnosis N = 2,667 |

|

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Year of delivery | ||

| 2000–2007 | 217 (39%) | 1044 (39%) |

| 2008–2017 | 338 (61%) | 1623 (61%) |

| Age at delivery (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 61 (11%) | 290 (11%) |

| 25–29 | 115 (21%) | 556 (21%) |

| 30–34 | 196 (35%) | 946 (35%) |

| 35–40 | 183 (33%) | 875 (33%) |

| Median age (IQR) | 32 (28, 35) | 32 (28, 35) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic (any race) | 78 (14%) | 575 (22%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 61 (11%) | 367 (14%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 337 (61%) | 1288 (48%) |

| Non-Hispanic, other race | 48 (9%) | 243 (9%) |

| Unknown/missing | 31 (6%) | 194 (7%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 375 (68%) | 1767 (66%) |

| Not married | 101 (18%) | 532 (20%) |

| Unknown/missing | 79 (14%) | 368 (14%) |

| Initiation of prenatal care | ||

| Early (first trimester) | 450 (81%) | 2052 (77%) |

| Late (second or third trimester) | 47 (8%) | 330 (12%) |

| Missing | 55 (10%) | 271 (10%) |

| Parity (number of previous livebirths) | ||

| 0 | 194 (35%) | 867 (33%) |

| 1 | 215 (39%) | 977 (37%) |

| 2 | 85 (15%) | 468 (18%) |

| 3 | 43 (8%) | 208 (8%) |

| 4+ | 18 (3%) | 146 (5%) |

| Gestational weeks at delivery Mean (SD) | 37.6 (2.3) | 38.6 (2.0) |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Preterm birth was more common among exposed pregnancies (25% vs. 9%, PR 2.70; 95% CI 2.24, 3.26), as was very preterm birth (5% vs. 3%, PR 1.74; 95% CI 1.12, 2.71) compared with unexposed pregnancies (Table 2). Neonates delivered to the exposed sample were more likely to be low birth weight (14% vs. 7%, PR 1.97; 95% CI 1.55, 2.50) but were not more likely to be small for gestational age (PR 0.88; 95% CI 0.66, 1.19). There was no significant difference in low APGAR score between groups (1% vs. 1%, PR 0.90; 95% CI 0.39, 2.06). Those in the exposed sample were more likely to undergo induction of labor (28% vs. 18%, PR 1.48; 95% CI 1.27, 1.73) and cesarean delivery (36% vs. 30%, PR 1.18; 95% CI 1.04, 1.34) compared with the unexposed sample (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Maternal and Neonatal Birth Outcomes According to the Presence or Absence of a Maternal Cancer Diagnosis During Pregnancy

| Obstetric outcomes | Live births after cancer diagnosis in pregnancy N = 555 | Matched noncancer live births N = 2,667 | PR (95% CI)a | PR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm birth, n (%) | ||||

| <37 weeks | 136 (25) | 247 (9) | 2.65 (2.19–3.19) | 2.70 (2.24, 3.26) |

| <34 weeks | 25 (5) | 67 (3) | 1.79 (1.14–2.81) | 1.74 (1.12, 2.71) |

| Low birth weight, n (%) | 80 (14) | 198 (7) | 1.94 (1.52–2.48) | 1.97 (1.55, 2.50) |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 46 (8) | 261 (10) | 0.85 (0.63–1.14) | 0.88 (0.66, 1.19) |

| Apgar <7 at 5 minutes, n (%) | <11 | 34 (1) | 0.99 (0.44–2.22) | 0.90 (0.39, 2.06) |

| Induction of labor, n (%) | 156 (28) | 486 (18) | 1.54 (1.32–1.80) | 1.48 (1.27, 1.73) |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 197 (36) | 797 (30) | 1.19 (1.05–1.35) | 1.18 (1.04, 1.34) |

Adjusts for matching factors (maternal age and year of birth).

Adjusts for matching factors (maternal age and year of birth), race/ethnicity, marital status, parity, and prenatal care timing.

CI, confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio.

We evaluated the prevalence of preterm birth according to the receipt of chemotherapy (Fig. 2). In 321 individuals who had no recorded chemotherapy, the prevalence of preterm birth was 11%. The prevalence of preterm birth among those who received chemotherapy at any time was 43%, 49% among those initiating chemotherapy treatment during pregnancy, and 37% among those who initiated chemotherapy treatment after delivery. To consider the potential that the high prevalence of preterm birth among those who received chemotherapy treatment was iatrogenic (due to induction or scheduled cesarean section), we examined preterm birth according to spontaneous births vs. induced or cesarean delivery births. Among the 114 individuals who received chemotherapy during pregnancy, 43% of spontaneous vaginal births and 54% of induced/cesarean births were preterm. Of those who received chemotherapy during pregnancy, 41% experienced spontaneous vaginal birth, while the majority (59%) were either induced or delivered by C-section. Among the 112 individuals who started chemotherapy after pregnancy, 32% of spontaneous vaginal births and 39% of induced/cesarean births were preterm. Of those who did not receive chemotherapy until after the pregnancy, a large majority (78%) were induced or delivered by c-section (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Prevalence of preterm birth among all births, spontaneous vaginal births, and induced or cesarean births, according to receipt of chemotherapy among live births that followed a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy.

Among exposed pregnancies overall, 31% of cancer diagnoses occurred in the first trimester, 37% in the second trimester, and 32% in the third trimester, providing some reassurance that there were not a disproportionate number of missing cancer diagnoses during the first trimester (Fig. 3). Melanoma diagnoses were relatively evenly distributed across all three trimesters of pregnancy, whereas a diagnosis of thyroid cancer occurred more often in the first two trimesters. Gynecological cancers had the greatest proportion of diagnoses in the second trimester (48%) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Distribution of cancer diagnoses by trimester among live births that followed a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy, overall and stratified according to cancer type.

Among exposed pregnancies, the most common type of cancer was breast cancer (33%), followed by melanoma (26%), thyroid cancer (21%), lymphoma (10%), and gynecological cancers (9%). The majority of cancers were localized at diagnosis (60%). Timing of initiation of cancer treatment is shown in Table 3. In our sample, 227 individuals (41%) received chemotherapy, half of which initiated chemotherapy during pregnancy and the other half in the postpartum period. We examined the receipt of surgery in those diagnosed with gynecological cancer (N = 50), as gynecological surgery may affect a developing pregnancy. The majority (86%) received some form of surgery; of these, 58% had surgery during pregnancy and 42% after delivery. Radiation therapy was evaluated for those diagnosed with gynecological cancer or lymphomas as abdominopelvic radiation carries the highest risk for a developing fetus. A minority had radiation (19%), and all initiated radiation after delivery (Table 3).

Table 3.

Maternal Cancer and Treatment Characteristics Among Women with Live Births Following a Cancer Diagnosis During Pregnancy

| Cancer and treatment characteristics | Women with live births following a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy N = 555 N (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of cancer | |

| Breast cancer | 184 (33) |

| Melanoma | 147 (26) |

| Thyroid cancer | 118 (21) |

| Lymphoma | 56 (10) |

| Gynecological cancera | 50 (9) |

| Stage of cancer at diagnosis | |

| In situ/Localizedb | 333 (60) |

| Regional | 181 (33) |

| Distant | 33 (6) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| No | 321 (59) |

| Yesc | 227 (41) |

| Chemotherapy initiated during pregnancy | 114 (50) |

| Chemotherapy initiated after pregnancy | 112 (50) |

| Surgery for gynecological cancer | 43 (86) |

| Underwent surgery during pregnancy | 25 (58) |

| Underwent surgery after pregnancy | 18 (42) |

| Radiation for gynecological cancer or lymphoma | |

| No | 85 (81) |

| Yes | 20 (19) |

| Radiation after delivery | 20 (100) |

Includes cervical, ovarian, and uterine cancer.

Includes 11 births to women with in situ breast cancer; all other births are to women with local invasive disease.

Includes subjects with missing information regarding timing of initiation of chemotherapy.

Discussion

We observed an increased prevalence of induction of labor and cesarean delivery in live births following a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy. Neonates born to those diagnosed with cancer during their pregnancy had a lower mean gestational age at delivery and higher prevalence of preterm and very preterm birth. After maternal cancer diagnosis during pregnancy, neonates had a higher prevalence of low birthweight, although were not more likely to be small for gestational age.

Our analysis adds to the growing body of evidence regarding birth outcomes following a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy and describes patterns in the timing of cancer treatment. Our findings of a lower average gestational age, increased prevalence of cesarean delivery, and preterm birth in live births following a cancer diagnosis are consistent with previous studies both in the United States and worldwide.3,9,13,26–29 It is important to note that although some prior studies are restricted to cancer diagnosis during pregnancy, many include cancer diagnoses up to 1-year postpartum. We did not observe an increased risk of small for gestational age, suggesting that the higher prevalence of low birth weight may be secondary to younger gestational ages at birth. Induction of labor was also more common in exposed pregnancies, potentially to allow for initiation of systemic cancer therapies.2,15,25

Our findings of higher prevalence of low birthweight infants, preterm birth, and cesarean delivery after cancer diagnosis during pregnancy are consistent with a recent U.S. population-based study performed in Texas,13 lending strength to the generalizability of these findings. The Texas investigation also observed higher risk among AYAs who received chemotherapy; however, information was not available to distinguish in utero chemotherapy exposures from those initiated after birth. In our analysis, 50% of individuals who were categorized as having received chemotherapy initiated chemotherapy after delivery. The Texas study also observed a 72% higher prevalence of low infant APGAR scores; this was not supported in our results, although there was overall low incidence of this outcome in our data.13

Cancer treatment during pregnancy is complex, individualized, and has changed over time.11 In an international multi-institutional study evaluating cancer treatment trends between 1996 and 2016, the proportion of patients receiving no treatment during pregnancy decreased from 45% prior to 2005 to 30% by 2016.14 In contrast, the proportion of individuals receiving chemotherapy treatment during pregnancy increased from 25% to 45% over the same time period. Increasing use of chemotherapy during pregnancy coincides with increased safety information and lack of associated birth defects with chemotherapy use in the second and third trimesters.25,30,31 In our sample, 19% of pregnant people diagnosed with gynecological cancer or lymphoma received radiation therapy. All initiated radiation therapy after delivery, consistent with avoidance of radiation therapy during pregnancy due to its known teratogenic effects.32

The use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has previously been associated with increased rates of preterm birth; however, findings on spontaneous preterm labor in this group have been mixed.15,25,33 Administration of chemotherapy within 3 weeks of delivery has been associated with a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including maternal and neonatal myelosuppression, postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, and death.34,35 Therefore, the observed increased risk of preterm birth may be partially due to iatrogenic preterm delivery by planned induction of labor or cesarean section in order to administer chemotherapy, rather than a direct effect of chemotherapy on spontaneous preterm labor.2,26,27 In our sample, 49% of individuals who received chemotherapy during pregnancy experienced preterm birth; in contrast, only 11% of those who never received chemotherapy experienced preterm birth, similar to the 10.5% overall rate of preterm births in the United States in 2021.36

Our analysis found an increased risk of several adverse birth outcomes after a cancer diagnosis that occurs during pregnancy. Due to small numbers of individual cancer types, aggregate numbers of the five most common cancers in our sample were included for analysis. As more data become available, the opportunity to evaluate birth outcomes after specific types of cancer diagnosis will become more feasible. Research into specific cancer treatment and birth outcomes is critical as treatment options for each type of cancer may pose unique risks to pregnancy. Future studies could also consider obtaining hospital coding data or chart review to allow for evaluation of additional maternal and neonatal outcomes.

A strength of our analysis is the use of a large, population-based cohort from two U.S. states with demographically diverse pregnant populations, increasing the generalizability of our study. In addition, we were able to focus solely on those diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy rather than including those diagnosed within the first-year postpartum. Although cancer diagnosed within the first-year postpartum is physiologically relevant to pregnancy due to the unique changes that occur that may play a role in the development of cancer, a diagnosis that occurs after delivery does not impact the management of the pregnancy or subsequent risks to the developing fetus. Restricting our analysis to cancers diagnosed during pregnancy provides relevant birth outcome data for those who are affected by cancer diagnosis and must make decisions while considering risks to the fetus as well. Our analysis should also be interpreted within the confines of its limitations. Our sample was limited to live births; therefore, any pregnancies that ended in miscarriage or abortion, whether spontaneous or induced, were not captured for analysis. Previous studies have shown that diagnosis of cancer early in pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester, is associated with termination of up to 43% of pregnancies.1,27 Therefore, we anticipated that there would be fewer diagnoses occurring in the first trimester as these pregnancies may have been more likely to be terminated after cancer diagnosis. In our overall sample, the proportion of all cancer diagnoses remained stable across all trimesters. However, fewer breast and lymphoma diagnoses were observed in the first trimester (25% and 13%, respectively). A lower proportion of first trimester diagnoses could indicate a higher proportion of terminations or pregnancy loss; or could reflect more frequent medical surveillance that occurs later in pregnancy with corresponding greater opportunities for cancer detection. This pattern was not observed for thyroid cancer, melanoma, or gynecological cancer.

We were able to include information regarding timing of chemotherapy receipt, although we lacked information on specific chemotherapy agents or doses in the North Carolina cancer registry data. Similarly, information on several adverse birth outcomes previously explored by other studies (including length of hospital admission and intrauterine demise) was not available for analysis from birth certificates in North Carolina.

Conclusion

Based on our data, women with a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy are at elevated risk for preterm birth, induction of labor, and cesarean delivery, but are not at increased risk for having a small for gestational age infant or an infant affected by low Apgar scores. These results are consistent with several prior studies evaluating birth outcomes after a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy.9,13,26,27,29 Taken together, our analysis suggests that the observed increased risk of preterm birth may be partially due to intentional preterm delivery to allow for coordination of cancer management, as the optimal timing of delivery to allow for appropriate cancer treatment has not been established. Our observed increased risk of low birth weight may be associated with the risk of being delivered preterm rather than a risk factor of treatment, as our analysis did not demonstrate an increased risk of small for gestational age infants. This may provide reassurance to patients who are concerned about short-term fetal risks of the cancer treatment itself. Ultimately, more research is needed to evaluate long-term effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment during pregnancy on childhood development and risks into adulthood.

A diagnosis of cancer during pregnancy is a traumatic event that raises many questions for the pregnant person and family involved. Study of PAC continues to be limited by small sample sizes given the rarity of the PAC compounded by the rarity of adverse birth outcomes. As health care systems merge and move toward the use of more universal electronic records, large-scale data are becoming more attainable. Future research could further explore adverse outcomes as they relate to individual cancer types with more directed therapy, including use of individual chemotherapy agents. With the observed rise in cancer diagnoses during pregnancy, there is a continued need to supply this population with evidence to help inform decision making.

Authors’ Contributions

C.C.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and visualization. C.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, and writing—reviewing and editing. S.M.: writing—reviewing and editing and project administration. L.G.: Writing—reviewing and editing. C.D.B.: Data curation and writing—reviewing and editing. J.E.M.: Writing—reviewing and editing. D.G.: Data curation and writing—reviewing and editing. M.L.K.: Data curation and writing—reviewing and editing. C.R.C.: Data curation and writing—reviewing and editing. L.H.K.: Data curation and writing—reviewing and editing. H.B.N.: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing and editing, supervision, and funding acquisition.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

This research was supported by NCI grant R01CA204258.

References

- 1. Eibye S, Kjær SK, Mellemkjær L. Incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer in Denmark, 1977-2006. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122(3):608–617; doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a057a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee YY, Roberts CL, Dobbins T, et al. Incidence and outcomes of pregnancy-associated cancer in Australia, 1994-2008: A population-based linkage study. BJOG 2012;119(13):1572–1582; doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03475.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith LH, Dalrymple JL, Leiserowitz GS, et al. Obstetrical deliveries associated with maternal malignancy in California, 1992 through 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184(7):1504–1512; discussion 1512–3; doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.114867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams TJ, Turnbull KE. Carcinoma in situ and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1964;24:857–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wingo PA, Tong T, Bolden S. Cancer statistics, 1995. CA Cancer J Clin 1995;45(1):8–30; doi: 10.3322/canjclin.45.1.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lundberg FE, Stensheim H, Ullenhag GJ, et al. Risk factors for the increasing incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer in Sweden—A population-based study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2023;103(4):669–683; doi: 10.1111/aogs.14677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Metcalfe A, Cairncross ZF, Friedenreich CM, et al. Incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer in two Canadian Provinces: A population-based study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(6); doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dalmartello M, Negri E, La Vecchia C, et al. Frequency of pregnancy-associated cancer: A systematic review of population-based studies. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(6); doi: 10.3390/cancers12061356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shechter Maor G, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Spence AR, et al. Neonatal outcomes of pregnancy-associated breast cancer: Population-based study on 11 million births. Breast J 2019;25(1):86–90; doi: 10.1111/tbj.13156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Janett RS, Yeracaris PP. Electronic medical records in the American health system: Challenges and lessons learned. Cien Saude Colet 2020;25(4):1293–1304; doi: 10.1590/1413-81232020254.28922019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salani R, Billingsley CC, Crafton SM. Cancer and pregnancy: An overview for obstetricians and gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211(1):7–14; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cottreau CM, Dashevsky I, Andrade SE, et al. Pregnancy-associated cancer: A U.S. population-based study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019;28(2):250–257; doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.6962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Betts AC, Shay LA, Lupo PJ, et al. Adverse birth outcomes of adolescent and young adult women diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2023;115(6):619–627; doi: 10.1093/jnci/djad044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Haan J, Verheecke M, Van Calsteren K, et al. International Network on Cancer and Infertility Pregnancy (INCIP) . Oncological management and obstetric and neonatal outcomes for women diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy: A 20-year international cohort study of 1170 patients. Lancet Oncol 2018;19(3):337–346; doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30059-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Calsteren K, Heyns L, De Smet F, et al. Cancer during pregnancy: An analysis of 215 patients emphasizing the obstetrical and the neonatal outcomes. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(4):683–689; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nichols HB, Baggett CD, Engel SM, et al. The Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Horizon Study: An AYA Cancer Survivorship Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2021;30(5):857–866; doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meyer AM, Olshan AF, Green L, et al. Big data for population-based cancer research: The integrated cancer information and surveillance system. N C Med J 2014;75(4):265–269; doi: 10.18043/ncm.75.4.265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buescher PA, Taylor KP, Davis MH, et al. The quality of the new birth certificate data: A validation study in North Carolina. Am J Public Health 1993;83(8):1163–1165; doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.8.1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Field TS, Cernieux J, Buist D, et al. Retention of enrollees following a cancer diagnosis within health maintenance organizations in the Cancer Research Network. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96(2):148–152; doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chubak J, Ziebell R, Greenlee RT, et al. The Cancer Research Network: A platform for epidemiologic and health services research on cancer prevention, care, and outcomes in large, stable populations. Cancer Causes Control 2016;27(11):1315–1323; doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0808-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johnson KE, Beaton SJ, Andrade SE, et al. Methods of linking mothers and infants using health plan data for studies of pregnancy outcomes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22(7):776–782; doi: 10.1002/pds.3443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson C, Baggett CD, Rao C, et al. Validity of state cancer registry treatment information for adolescent and young adult women. Cancer Epidemiol 2020;64:101652; doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2019.101652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Battaglia FC, Lubchenco LO. A practical classification of newborn infants by weight and gestational age. J Pediatr 1967;71(2):159–163; doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(67)80066-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159(7):702–706; doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loibl S, Han SN, von Minckwitz G, et al. Treatment of breast cancer during pregnancy: An observational study. Lancet Oncol 2012;13(9):887–896; doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70261-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lu D, Ludvigsson JF, Smedby KE, et al. Maternal cancer during pregnancy and risks of stillbirth and infant mortality. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(14):1522–1529; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.9439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barrois M, Anselem O, Pierga JY, et al. Cancer during pregnancy: Factors associated with termination of pregnancy and perinatal outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2021;261:110–115; doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Esposito G, Franchi M, Dalmartello M, et al. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes in women with pregnancy associated cancer: A population-based study in Lombardy, Northern Italy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21(1):31; doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03508-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Safi N, Li Z, Anazodo A, et al. Pregnancy associated cancer, timing of birth and clinical decision making-a NSW data linkage study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023;23(1):105; doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05359-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amant F, Han SN, Gziri MM, et al. Chemotherapy during pregnancy. Curr Opin Oncol 2012;24(5):580–586; doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328354e754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cardonick EH, Gringlas MB, Hunter K, et al. Development of children born to mothers with cancer during pregnancy: Comparing in utero chemotherapy-exposed children with nonexposed controls. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212(5):658 e1-8–658.e8; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. American College of O, Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric P. Committee Opinion No. 656: Guidelines for Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy and Lactation. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127(2):e75-80; doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cardonick E, Usmani A, Ghaffar S. Perinatal outcomes of a pregnancy complicated by cancer, including neonatal follow-up after in utero exposure to chemotherapy: Results of an international registry. Am J Clin Oncol 2010;33(3):221–228; doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181a44ca9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brewer M, Kueck A, Runowicz CD. Chemotherapy in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2011;54(4):602–618; doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318236e9f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ngu SF, Ngan HY. Chemotherapy in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2016;33:86–101; doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Osterman MJK, Hamilton BE, Martin JA, et al. Births: Final data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2023;72(1):1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]