Abstract

Background & Aims

Lymph node metastasis (LNM) is a major determinant of recurrence and prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA). LNM disrupts T cell-mediated cytotoxicity, promotes tumor-specific immune tolerance, and facilitates distant metastasis. Despite its importance, extensive research on LMN in iCCA is lacking. This study aimed to systematically explore the heterogeneity of the LNM-associated microenvironment in iCCA by integrating single-cell and multi-omics analyses, identifying metastasis-associated cell subgroups, and validating these findings through multiple cohorts.

Methods

We analyzed single-cell transcriptomics data from primary tumors, cancer-adjacent liver tissues, and tumor-draining lymph nodes of four patients with iCCA who underwent radical surgery. Additionally, we collected 81 tumor and matched lymph node tissue sections from patients with iCCA. We performed single-cell RNA sequencing and multiplex immunohistochemistry, followed by differential gene expression analysis, functional enrichment analysis, single-cell copy number variation assessment, and pseudotime analysis.

Results

Our analysis revealed the complex heterogeneity of the iCCA LNM-associated microenvironment. We found a significant increase in stromal and mature immune cells in the metastatic lymph nodes. T cells constitute the predominant component, with diverse functional subtypes. We identified CD36+ macrophages and SAA1+ tumor cells as key players in the metastatic process. The SAA1-CD36 receptor‒ligand pair may be crucial in forming the LNM-associated microenvironment.

Conclusions

We identified several metastasis-associated cell subgroups. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying LNM in iCCA and lay the groundwork for the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Our study highlights the importance of single-cell technologies in understanding tumor microenvironment complexity and offers valuable resources for future research.

Impact and implications:

The lack of single-cell transcriptome analysis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) lymph node metastases has prevented us from understanding the underlying mechanisms of disease progression. To fill this knowledge gap, we elucidated the unique ecosystem of iCCA lymph node metastases, which is an important advance in clarifying the impact of the immune environment on the development of this disease. The results of this study identified several LNM-related therapeutic targets, which will not only be helpful to basic researchers, but also provide potential diagnostic and treatment ideas for physicians, thereby helping patients and their caregivers develop more personalized treatment plans. This finding is highly important for improving the prognosis of patients with advanced iCCA in the future.

Keywords: Bioinformatics, Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry, Lymph node metastatic microenvironment, Single-cell RNA sequencing

Graphical abstract

Highlights:

-

•

Our study revealed the cell type landscape of LNM and primary iCCA.

-

•

SAA1-CD36 interaction plays a crucial role in forming LNM-associated TME.

-

•

CD36+ macrophages interact with Tex and Treg cells to promote iCCA immunosuppression.

Introduction

Metastasis is a non-random, coordinated progression of malignant tumors and is the most common cause of death from cancer. Lymph node metastasis (LNM) serves as a foothold for further tumor spread and is one of the main determinants of recurrence and prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA). LNM disrupts T cell-mediated cytotoxicity against tumor cells, activates antigen-specific T cells, promotes tumor-specific immune tolerance, and facilitates distant tumor metastasis.1

The propensity of tumors to metastasize results from tissue-specific interactions between tumor cells and various organs.2 Before tumor metastasis, distant organs often establish a premetastatic microenvironment conducive to tumor growth by recruiting myeloid cells and fibroblasts that secrete cytokines and inflammatory factors. For example, in gastric cancer, tumor cells and immune cell subgroups within metastases to the liver, peritoneum, ovaries, and lymph nodes exhibit organ specificity.3 In iCCA, paracrine signaling networks derived from fibroblasts, such as PDGF-BB/PDGFR-β, promote tumor LNM.4 Notably, lymph nodes, secondary immune organs composed of lymphocytes, myeloid cells, and stromal cells, have complex tissue structures and cellular compositions during metastasis, making single-cell transcriptomics an excellent tool for exploring such metastatic tumor microenvironments. To date, extensive research has been devoted to analyzing the complex and highly heterogeneous tumor microenvironment of iCCA. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of iCCA tumor tissues has highlighted the importance of the cell interaction network in the progression of iCCA. For example, cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF)-secreted IL-6 can induce significant epigenetic changes in iCCA cells, especially the upregulation of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) expression, enhancing tumor malignancy.5 Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of iCCA from different tissue types has revealed differences in the tumor microenvironment composition and biomarkers between large bile duct-type iCCA and small bile duct-type iCCA, deepening our understanding of iCCA tumor diversity.6 Most studies have focused on the direct effects of cells in the primary tumor; few have focused on how tumor cells subvert the immune function of normal lymph nodes through LNM, thereby affecting the primary tumor’s microenvironment and promoting tumor progression.

In this study, we used single-cell transcriptomics to analyze the primary tumors, cancer-adjacent liver tissues, and tumor-draining lymph nodes of four patients with iCCA, aiming to systematically explore the heterogeneity of the iCCA LNM-associated microenvironment, identify metastasis-associated cell subgroups, and validate these findings through multiple cohorts and a large number of samples. We hope our study can lay the foundation for elucidating the mechanisms of iCCA LNM.

Patients and methods

Paraffin-embedded patient samples

We retrospectively collected 81 tumor and matched lymph node paraffin sections from patients with iCCA who underwent intraoperative drainage for lymph node clearance at our institution. Two pathologists confirmed the LNM status through H&E staining of the tissues and premarking representative areas in the paraffin blocks. None of the patients with iCCA from which the samples originated received systemic or local treatment before surgical resection. Among these patients, 41 had LNM, whereas the other 40 did not. Patient information is shown in Tables S1 and S2.

Ethics approval and consent to participate was overseen by the Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Renji Hospital Ethics Committee (KY2022–024-B,KY2024-096-C).

Single-cell sequencing of patient samples

In our single-cell transcriptomic sequencing analysis, we included four patients who were diagnosed with iCCA and who underwent radical surgical resection. A total of four tumor samples, four adjacent normal liver samples, and seven lymph node samples were collected from January 1, 2022 to July 30, 2023. For patients with iCCA with lymph node negativity, we confirmed the absence of LNM through multiple rigorous steps. These patients initially underwent thorough physical and radiological examinations before surgery. The lymph nodes were harvested and subjected to intraoperative frozen pathological examination during surgery. These meticulous procedures collectively confirmed the absence of LNM in lymph node-negative patients with iCCA. None of these patients received targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or any other antitumor treatment before surgery. Patient information is shown in Table S3.

Multiplex immunohistochemistry

Multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Opal® Reagent Kit, Akoya Biosciences). The process involved a sequential flow of antibodies and fluorescent dyes for the following panels: 1st panel: PanCK/Opal480, CD4/Opal520, FOXP3/Opal620, PDCD1/Opal690, and CD8/Opal780; 2nd panel: PanCK/Opal480, CD36/Opal520, CD206/Opal690, and DAPI; 3rd panel: α-SMA/Opal520, THBS1/Opal690, DAPI; 4th panel: PanCK/Opal520, SAA1/Opal690, DAPI; 5th panel: CD36/48Opal620, CD68/Opal690, CD36/Opal520, PDCD1/Opal570, CD4/Opal480, FOXP3/Opal780, and DAPI. All the antibodies were obtained from Abcam. The stained slides were scanned at low magnification (10 × ) under fluorescent conditions via the Vectra Polaris 1.0.13 imaging system (Akoya Biosciences) and then observed at high magnification (20 × ) for each core. InForm 2.4.0, digital image analysis software (Akoya Biosciences) was used to analyze each sample. Marker colocalization was used to identify specific cell phenotypes from each mIHC group. The density of each cell phenotype was quantified, and the final data are presented as cell numbers/mm2. Spatial cell distribution analysis was conducted via HALO software with the spatial analysis module (Indica Labs, Albuquerque, NM, USA).

Preparation of single-cell suspensions

Fresh tumor tissues, cancer-adjacent normal liver, and draining lymph node samples were immediately separated after tumor resection and transferred to 50 ml centrifuge tubes containing precooled RPMI 1640 medium (containing 0.04% bovine serum albumin [BSA], Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The samples were then quickly transported to the laboratory on ice to minimize the ischemia time. The samples were chopped into 1-mm3 pieces and digested enzymatically using the Miltenyi Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The samples were then centrifuged at 300 × g for 30 s, after which the supernatant was discarded. Next, 1 × PBS containing 0.04% BSA (400 μg/ml) was added, and the samples were centrifuged again at 300 × g for 5 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of red blood cell lysis buffer and incubated at 4 °C for 10 min. The samples were subsequently resuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing 0.04% BSA and filtered through Scienceware Flowmi 40 μm cell strainers (VWR International). Finally, a 10 μl suspension was examined under an inverted microscope, and cells were counted using a hemocytometer. Trypan blue was used to quantify live cells.

Droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing

The cell suspensions were subjected to library preparation via the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kit (version 3.1; 10 × Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Single-cell libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Nova-Seq 6000 PE150 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) through paired-end sequencing. cDNA was obtained after GEM (gel bead-in-emulsion) generation and barcoding, followed by a GEM reverse transcription reaction. The cDNA was appropriately amplified via PCR depending on the number of recovered cells. The amplified cDNA was then fragmented, end-repaired, A-tailed, adaptor-ligated, and further amplified.

Acquisition of public datasets

Bulk transcriptome RNA sequencing data (n = 399) with prognostic information were obtained from the E-MTAB-6389 (n = 78), TCGA (n = 36, https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga), GSE107943 (n = 30), and CPTAC (FU-iCCA cohort, n = 255) datasets.[7], [8], [9],[7], [8], [9] Proteomic data (n = 262) from the CPTAC (FU-iCCA cohort) were also collected to elucidate cross-omics correlations and potential molecular mechanisms.

Single-cell transcriptome sequencing data processing

The CellRanger software pipeline (version 5.0.0) was used for demultiplexing, barcode processing, alignment, and initial clustering of the raw single-cell sequencing profiles. The raw sequencing reads were mapped, annotated, and quantified using the GRCh38 reference annotation file (ENSEMBL, https://cf.10xgenomics.com/supp/cell-exp/refdata-gex-GRCh38-2020-A.tar.gz). The UMI count matrix was processed using the R package Seurat (version 5.0.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), which applies uniform criteria to filter out cells with UMI/gene counts exceeding the average ±2 standard deviations of the median absolute deviation, assuming a Gaussian distribution for each cell’s UMI/gene count.10 After visually inspecting the cell distributions, we discarded low-quality cells in which over a quarter of the counts were mitochondrial genes. Additionally, potential doublets were identified via the DoubletFinder package (version 2.0.2). After these quality control standards were applied, 123,127 high-quality single cells were used for the downstream analysis. The R package Harmony (version 1.2.0) was used to combine the normalized expression profiles of all the samples. Library size normalization was subsequently performed using the NormalizeData() function in Seurat to obtain normalized counts, followed by log transformation. The top 2,000 highly variable genes were identified via the FindVariableFeatures() function, as previously described.

Principal components were calculated according to the expression profiles of the top 2,000 highly variable genes. The FindNeighbors() and FindClusters() functions in Seurat were used for cell clustering. The RunUMAP() function was used for visualization when appropriate. The cells were visualized via the 2D uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) algorithm and the RunUMAP() and DimPlot() functions. The marker genes for each cluster were identified via the FindAllMarkers() function in Seurat. For a given cluster, the FindAllMarkers() function identified positive markers compared with all remaining clusters.

Dimensionality reduction, clustering, and cell type annotation

Given the presence of cell types from multiple lineages in the dataset, clustering was performed hierarchically. The first round of clustering was optimized to distinguish lineages. Given the successful coarse clustering, subsetting cells by lineage was relatively reliable and resulted in minimal information loss. After subsetting cells by lineage, highly variable genes were recalculated within each lineage, optimizing biologically relevant features for each lineage and thus producing more accurate clustering. The recalculated sets of highly variable genes were used for additional dimensionality reduction and reclustering rounds. This strategy allowed us to optimize the features selected for each round of clustering and avoid noise that may arise from the use of many principal components in a single round of clustering. We performed a first round of dimensionality reduction and clustering and then zoomed in on heterogeneous cell groups for additional refinement.

Calculation of differentially expressed genes and functional enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis were performed using the R package ClusterProfiler to identify enriched functional pathways between the two subgroups. Differentially expressed genes under different conditions were calculated via the R package limma. Genes with an adjusted p value <0.05 and a fold change >1.5 (log2FC >0.58) were considered to have significantly upregulated expression, whereas those with an adjusted p value <0.05 and a fold change <0.67 (log2FC <-0.58) were considered to have significantly downregulated expression. Another method of functional enrichment analysis, gene set variation analysis (GSVA), was used to analyze differentially regulated pathways using the R package ClusterProfiler. The gene sets for GSVA analysis were downloaded from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB, v7.1) at the Broad Institute.

Single-cell copy number variation assessment

The R package inferCNV (version 1.0.4) was used to assess copy number variants (CNVs) in each cell on chromosomes. The CNV levels of these main cell types were calculated according to the gene expression levels in their scRNA-seq data, with a cut-off value of 0.1. Genes were sorted according to their chromosomal positions, and the moving average of gene expression was calculated using a window size of 101 genes. Expression was centered at zero by subtracting the mean. iCCA cells were chosen as malignant cells, leaving all remaining cells as normal cells. The parameters for inferCNV analysis included "denoising",’default hidden Markov model settings, and a "cut-off" value of 0.1.

Pseudotime analysis

Developmental pseudotime analysis was performed using the Monocle3 software package (version 3.0.0) to infer the developmental trajectories of specified cells.11 Monocle's ImportCDS() function was first used to convert the raw counts from the Seurat object into a CellDataSet object. The DifferentialGeneTest() function was used to select ordered genes (q value <0.01) that might provide information for ordering cells along a pseudotime trajectory. Dimensionality reduction clustering analysis was performed via the reduceDimension() function, followed by trajectory inference via the OrderCells() function with default parameters. Visualization was performed using the ClusterGvis package function to analyze gene changes following pseudotime.

Deconvolution of the tumor microenvironment with BayesPrism

The BayesPrism method allows for the inclusion of cell type-specific marker genes in the deconvolution process with single-cell data as a reference, thereby parsing the cellular composition in bulk RNA sequencing samples.12 This method has shown optimal overall performance and robustness against tumor purity in tumor microenvironment analysis and performs well in immune cell types.13 BayesPrism v2.0 was installed from the GitHub repository https://github.com/Danko-Lab/BayesPrism. In addition to cell types, BayesPrism also allows the specification of cell subtypes (cell states) in the single-cell reference matrix. Deconvolution scores of the cell states for each cell type are summed to produce scores for the cell types. The cell types and states were annotated according to the cell groups, and subgroups were annotated in the Seurat object. All other parameters were set to the algorithm’s default options. Finally, BayesPrism generated two sets of predicted cell type scores, one before and one after the Gibbs sampling steps, using intrasample tumor expression and inter-sampling non-tumor expression to update the reference matrix. We used the post-Gibbs sampling results of BayesPrism in this study. The specific principles of the algorithm are detailed in https://github.com/Danko-Lab/BayesPrism.

Identifying phenotype-associated subgroups with Scissor by integrating bulk and single-cell sequencing data

Scissor is a novel method that uses phenotypic information collected from bulk RNA sequencing data, such as disease stage, tumor metastasis, treatment response, and survival outcomes, to identify cell subgroups most related to the phenotype from single-cell data.14 Scissor v2.1.0s was downloaded from the GitHub repository (https://github.com/sunduanchen/Scissor). The LNM status in the FU-iCCA cohort was used as the phenotype, and bulk RNA expression profiles were used as input data to identify LNM-associated tumor cell subgroups from single-cell data.

Cell-to-cell communication analysis with CellChat

The CellChat R package (version 2.1.1) was used to assess potential cell-to-cell communication.15 The normalized expression matrix was imported to create a CellChat object via the CellChat() function. The data were then preprocessed via the identifyOverExpressedGenes(), identifyOverExpressedInteraction(), and ProjectData() functions with default parameters. The computeCommunProb(), filterCommunication(), and computeCommunProbPathway() functions were then used to determine any potential ligand‒receptor interactions. Finally, the cell communication networks were aggregated via the aggregateNet() function.

Cell culture and reagents

The human cholangiocarcinoma cell line HCCC9810 was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Meilunbio, MA0215) supplemented with 10% FBS (CELLCOOK, CM1002L). The human monocytic cell line THP-1 was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol (ScienCell, CSP005). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (MultiSciences, CS0001) was added to the medium (100 ng/ml) to induce the differentiation of THP-1 cells into macrophages. OxLDL (10 ng/ml) was used to further induce macrophages to differentiate into CD36+ macrophages.

Small interfering RNAs

The transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Co., Ltd., Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. siSAA sequencing: SAA1-forward: 5′-AGGGTACACAATGGGTATCTA-3′, SAA1-backward: 5′-TTACATCGGCTCAGACAATA-3′.

Coculturing of tumor cells and macrophages

HCCC9810 or HCCC9810/siSAA1 cells were seeded into 10 cm2 plates. Twenty-four hours later, when the density reached 50–60%, CD36+ macrophages were added and cocultured with or without sulfo-N-succinimidyloleate (SSO) for 72 h. The supernatant was then collected and frozen at -80 °C.

Transwell assays

Transwell migration assays were performed with Corning® FluoroBlokTM inserts (351152, Corning). The same number (∼105/well) of cells were seeded in the upper chamber with serum-free DMEM, and the lower chamber was filled with supernatant collected from HCCC9810, HCCC9810/siSAA + macrophages or HCCC9810 + macrophages + SSO. Forty-eight hours later, the migrated cells were stained with crystal violet. Images were collected under a fluorescence microscope. All the experiments were performed in biological triplicates.

Protein extraction and Western blotting

Proteins were extracted with RIPA lysis buffer (Yeasen, 20101ES60) in the presence of a protease inhibitor (Epizyme Biotech, GRF101) and protein phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Epizyme Biotech, GRF102). Proteins were separated by SDS‒PAGE and transferred to a Polyvinylidene Fluoride membrane (Millipore, IPVH00010). The following antibodies were used: Santa Cruz (Abcam, sc-52328, Mouse mAb, 1:1,000), N-cadherin (Santa Cruz, Mouse mAb, sc-59987, 1:1,000), vimentin (Santa Cruz, sc-32322, Mouse mAb, ab222320, 1:1,000), SMAD3 (CST, Rabbit mAb #9523), α-SMA (Shanghai BK, Mouse mAb, BK-KT9908) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, Proteintech, 60004-1-Ig, 1:2,000). The samples were then incubated with anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Proteintech, USA) at room temperature for 2 h. An enhanced chemiluminescence agent (LinBio, LP200202) was used to visualize the membrane. Images were captured with a Tanon chemiluminescence imaging system (Tanon, China). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as the internal control.

Statistical analyses

All the statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1. In this study, the primary outcome of the survival analysis was overall survival (OS). OS rates were estimated via the Kaplan‒Meier method and compared via the log-rank test. Categorical data were evaluated using the Χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Differences in quantitative data between the two groups were analyzed using Student’s t test. Comparisons among multiple groups were performed with one-way ANOVA. The quantitative results are presented as the means ± standard deviations. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05.

Results

Single-cell landscape of the metastasis-associated microenvironment in iCCA

The research process is shown in Fig. 1A. Through single-cell RNA sequencing of the samples and rigorous quality control, we generated a comprehensive expression matrix encompassing 123,127 cells and 28,734 genes. Specifically, these cells originate from metastatic lymph nodes (31,486 cells), non-metastatic lymph nodes (9,784 cells), primary tumors (40,310 cells), and cancer-adjacent normal liver tissue (41,547 cells), demonstrating optimal coverage and representativeness of the transcriptome (Fig. 1B). We used the UMAP algorithm within the Seurat package to identify clusters of cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME) with similar expression profiles. By analyzing the characteristic expression genes of different cell types, we classified the cells into 10 main types, including T cells (marked by PTPRC, CD3D, and CD3E), B cells (PTPRC, CD79A, CD19, and MS3A1), dendritic cells (CD1C), endothelial cells (ENG, VWF, and CLDN5), epithelial cells (KRT7, KRT19, and EPCAM), fibroblasts (COL1A1, PDGFRB, COL1A2, and ACTA2), hepatocytes (ALB), macrophages (APOE, CD68, and CD14), mast cells (TPSAB1 and KIT), and neutrophils (S100A8 and S100A9) (Fig. 1C and D). Analysis of the main cell type proportions across the four different metastasis-related tumor ecosystems revealed a high degree of heterogeneity in cell composition. In metastatic lymph nodes, an expanded proportion of stromal and mature immune phenotypes was observed (Fig. 1E). Overall, these cell types were found across all patient samples, albeit with significant interpatient proportional differences, reflecting the high heterogeneity of the iCCA TME.

Fig. 1.

The single-cell landscape of the metastasis-associated microenvironment in iCCA.

(A) The diagram of the study. (B) UMAP map of 123,127 cells, showing the components of normal adjacent tumors, primary tumors, metastases, and normal lymph node microenvironments, color-coded by major cell lineages. (C) Mapping of marker genes of major cell lineages on the UMAP map. (D) Heat map of marker genes of major cell lineages. (E) Line graph of the relative proportions of major cell lineages in normal adjacent tumors, primary tumors, metastases, and normal lymph nodes. LN, lymph node; LNM, lymph node microenvironment; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Lymphocyte subpopulations and their diverse enrichment in the metastatic microenvironment of iCCA

Regarding the cellular composition landscape, T cells are the predominant component of the iCCA tumor microenvironment. To explore the differential functions of T cell subtypes, we analyzed the gene expression of all T cells, classifying them into 24 subgroups according to the average gene expression levels and expression levels of typical marker genes associated with different T cell subtypes and states. This analysis identified 10 T cell subtypes (Fig. 2A). Naïve T cells (TNaive) presented high TCF7, LEF1, SELL, and CCR7 expression levels. Central memory T (Tcm) cells expressed IL7R and shared several marker genes with TNaive, including SELL and TCF7. Subgroups with high IL7R and CD69 expression were defined as tissue-resident memory T cells (TRMs). The effector T cell subtypes (Teff) presented high GZMK and GZMA expression, whereas natural killer T (NKT) cells expressed high levels of FGFBP2. Exhausted T cell subgroups (Tex) were identified by the overexpression of immune checkpoints such as PDCD1 and LAG3 and high levels of TOX1. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) expressed FOXP3, TIGIT, and CTLA4, and active CD4+ T cells (Tactive) expressed TNF, CTLA4, and IFNG. NK cells highly expressed XCL2, while CD4 and CD8 expression levels were weak. Subgroups highly expressing MKI67 and TUBB were defined as proliferating T cells (Tprof) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Lymphocytes subpopulations and their diversified enrichment in the metastatic microenvironment of iCCA.

(A) Differential expression and stacked bar graph of T cell subset functional state characteristics, showing cell numbers of T cells with different states, color-coded by the ecosystem from which they originate. Point size: percentage of cells expressing the gene, point color: average expression to scale. (B) UMAP plot of annotated subpopulations of T cells separated according to their different tissue origins and composition of T cell subpopulations among different tissue types. (C) GSVA functional enrichment analysis heat map of T cell subtypes. (D) Heat map showing the dynamics of known functional feature proportion scores along pseudotime and the distribution of T cell subclusters during differentiation. (E) Significant correlation between cell function score (exhaustion, cytotoxicity, immunosuppression, and proliferation) and pseudo-chronology. Pearson’s correlation. (F) Relative pseudo-chronology of T cells from different sample sources. (G) Causes of LNM and non-metastasis differences in the composition of T cell subtypes in tumor lesions. (H) mIHC representative images of CD4, FOXP3, PDCD1, CD8, and PanCK in LN+ and LN- lesions. Scale bar 50 μm. (I) Quantitative analysis of CD8+PDCD1+ cells, CD4+FOXP3+ cells, PanCK+ cells and comparison between LN+ and LN- lesions. Student’s t tests. ns, not significant, ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p <0.01. GSVA, gene set variation analysis; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection; mIHC, multiplex immunohistochemistry.

We depicted the distribution of T cell subtypes in different types of samples (Fig. 2B). The results revealed that TNaive cells appeared in almost all non-metastatic lymph nodes, whereas tumors and metastatic lymph nodes included mainly Teffs and TRMs activated by antigens, suggesting good differentiation potential in non-metastatic lymph nodes. Tex cells were found only in primary tumors, and the proportion of TRMs with proliferative potential was very low in tumors, indicating that tumor-specific T cells in iCCA depend on extratumoral immune organs. Additionally, the source of immunosuppressive signals was more abundant in primary tumors (Fig. 2B). GSVA also revealed that multiple immunoregulatory pathways, including the interferon-gamma response and IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, were enriched in Texs and Tregs (Fig. 2C). To further explore the dynamic differentiation process of T cells in iCCA, we used Monocle3 to infer the trajectory of T cells from differential expression profiles and estimated their relative pseudotime along trajectories. We observed the dynamic trajectories of T cells, starting from a naïve state, mediating to memory, regulatory, or effector states, and finally terminating in an exhausted state (Fig. 2D). Combining pseudotime analysis with T cell functional module analysis revealed that as T cells developed, the suppression, cytotoxicity, exhaustion, and proliferation scores increased (Fig. 2E). When the average pseudotime was classified by sample type, the overall differentiation sequence of T cells was non-metastatic lymph nodes, cancer-adjacent normal tissue, metastatic lymph nodes, and primary tumors (Fig. 2F). We also analyzed T cell proportions in the FU-iCCA cohort via BayesPrism (Fig. S1A), revealing that naïve B cells, TNaive cells, NKTs, TRMs, and Teffs were associated with better OS, whereas Tregs were associated with poor prognosis (Fig. S1B).

To explore whether LNM affects the function and quantity of T cells in primary tumors, we grouped tumor samples according to the presence or absence of draining LNM. We detected a greater proportion of TRMs in tumors without LNM, whereas primary tumors with LNM presented significantly greater proportions of Tregs and Texs (Fig. 2G). These findings suggested that the antitumor immunity of LN+iCCA patients is notably weakened. We conducted mIHC staining on paraffin-embedded tissue sections from 81 patients with iCCA collected from Renji Hospital, including paired tumor tissues and draining lymph nodes, with 41 LN+ and 40 LN– samples. The clinicopathological information of the patients is summarized in Table S1. The staining panel included CD8, CD4, PDCD1, FOXP3, and PanCK (Fig. 2H). Quantitative analysis revealed that tumors from LN+ patients had more CD8+PDCD1+ Tex cells and CD4+FOXP3+ Treg cells, with no significant difference in tumor cell density (Fig. 2I). Thus, we propose that LNM significantly weakens the antitumor immune response in iCCA patients.

We also identified six B-cell subtypes, including naïve B cells, memory B cells, activated B cells, germinal center B cells, interferon (IFN)-induced B cells, and plasma cells (Figs. S1C and D).

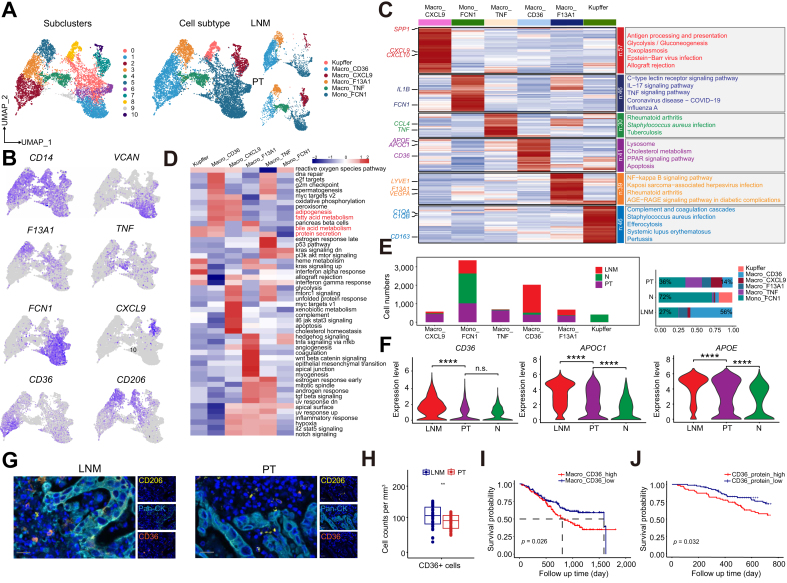

Abnormal accumulation of metastasis-associated macrophages in the lymph node metastases of iCCA

Regarding myeloid cells, 13,873 cells were collected, and over half were derived from monocytes and macrophages, categorized into 11 subclusters (Fig. 3A). After marker gene analysis, six subtypes were defined: CXCL9+ macrophages, CD36+ macrophages, TNF+ macrophages, F13A1+ macrophages, FCN1+ monocytes, and Kupffer cells (Fig. 3A and B). These subgroups presented distinct gene expression characteristics, and gene function enrichment varied. The genes highly expressed in CD36+ macrophages were related mainly to lysosomes, cholesterol metabolism, the PPAR signaling pathway, and apoptosis, indicating their role in regulating lipid metabolism and cell death. CXCL9+ macrophages are involved mainly in immune activation pathways such as antigen processing and presentation, allograft rejection, and Epstein‒Barr virus infection (Fig. 3C and D). Macrophages secrete various cytokines, including interleukins, growth factors, and chemokines, at different stages of differentiation to regulate the tumor immune response and inflammatory reaction or promote tumor cell migration and proliferation. We found that the composition of mononuclear/macrophages significantly changed from the normal microenvironment to the tumor tissue and metastatic lymph nodes (Fig. 3E). The proportion of FCN1+ monocytes decreased from 72% in normal tissue to 36% in primary tumors and 27% in metastatic lymph nodes, accompanied by an increase in the proportion of macrophages. These findings suggest a potential transition from monocytes to macrophages throughout the entire iCCA metastasis-related microenvironment. In normal liver, macrophages are predominantly Kupffer cells, with other macrophage subtypes constituting less than 10% of all macrophages. In primary tumors, however, there were four other macrophage subtypes in addition to Kupffer cells, with similar proportions (12–22%). Interestingly, in metastatic lymph nodes, CD36+ macrophages dominated, increasing from 5% in normal tissue and 14% in primary tumors to 56%. We identified these metastasis-associated macrophages via the expression of APOE, APOC1, and CD36, with the upregulation of the expression of genes related to pathways such as lipid synthesis, fatty acid metabolism, cholesterol metabolism, endocytosis, and protein secretion (Figs. S2A and B). Similarly, the expression levels of the CD36, APOE, and APOC1 genes in metastatic lymph nodes were significantly greater than those in primary tumors and normal adjacent tissues (Fig. 3F). We also observed that in FU-iCCA samples, CD36 gene expression was highly positively correlated with immune checkpoint and M2-like macrophage polarization-related genes, indicating that CD36 expression was positively correlated with adverse immune characteristics (Fig. S2C).

Fig. 3.

The abnormal accumulation of metastasis-associated macrophages in the LNM of iCCA.

(A) UMAP of monocytes and macrophages, showing the composition and relative abundance of cell subtypes, color-coded by subclusters (left) and annotated cell subtypes (middle), and sample sources (right). (B) Mapping of marker genes of macrophages in the UMAP map. (C) Heat map of characteristic genes of macrophage subtypes and KEGG functional enrichment analysis. (D) Heat map of GSVA functional enrichment analysis of macrophage subtypes. (E) Changes of the various macrophage proportions in different tissues of iCCA patients. (F) Violin plots of gene expression levels of APOE, APOC1, and CD36 in different samples (Student’s t test). (G) Representative images of CD36, CD206, and PanCK mIHC in LNM and primary tumor sections. Scale bar 50 μm. (H) Quantitative analysis of CD36+ macrophages in LNM and primary tumor lesions (Student’s t test). (I) KM curves for overall survival of 255 patients in the FU-iCCA cohort, stratified by high and low scores of the selected marker signature. Log-rank Mantel–Cox test. (J) KM curves for 2-year overall survival of 255 patients in the FU-iCCA cohort, stratified by high and low CD36 protein (log-rank Mantel–Cox test). ns, not significant, ∗∗p <0.01, ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001. GSVA, gene set variation analysis; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; LNM, lymph node metastasis; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection; mIHC, multiplex immunohistochemistry.

In pathological sections, we used mIHC to quantitatively analyze the differences in the infiltration of CD36+ macrophages between iCCA lymph node metastatic foci and primary tumors, revealing a significantly greater density of CD36+ macrophages in metastatic lymph nodes (Fig. 3G and H). To explore the prognostic characteristics of different macrophage subtypes, we used BayesPrism to deconvolute the cellular composition of tumor samples in the FU-iCCA transcriptome cohort. We found that a high proportion of CD36+ macrophages was associated with poor prognosis (Fig. 3I), and a high protein level of CD36 in the FU-iCCA proteomic database also indicated poor survival outcomes (Fig. 3J). In addition, the same results were obtained in the quantitative analysis of CD36 IHC staining in the samples from the cohort of patients from our center (Fig. S2D). These results suggest that one of the characteristics of the iCCA metastatic tumor microenvironment is the presence of a high density of TAMs, and these metastasis-associated macrophages could serve as a potential therapeutic target to prevent the progression of iCCA and LNM.

Cancer-associated fibroblasts related to iCCA metastasis

A total of 8,764 stromal cells were classified as fibroblasts or endothelial cells (Fig. 4A). Endothelial cells express common tumor-associated endothelial cell markers, including PLVAP and ACKR1, whereas the fibroblast population includes multiple signature markers of CAFs (Fig. 4B). Among them, we identified 13 subgroups totaling 5,752 fibroblasts with specific expression markers (ACTA2, COL1A2), including two vascular smooth muscle cell subgroups, one pericyte subgroup, one normal activated fibroblast (NAF) subgroup, and nine CAF subgroups (Fig. 4C and D). The CAFs (C0, C2, C4–8, C10, and C12) were further divided into five clusters according to the differential expression of classic CAF markers (Fig. 4E). C0 expressed high levels of VEGFA and VEGFB. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses revealed that the genes with upregulated expression were enriched in extracellular structure formation, muscle tissue development, and the regulation of vascular system development. Therefore, C0 cells were defined as vascular CAFs (vCAFs). C2 was characterized by high levels of inflammatory factors and chemokines, including IL-6, CCL8, and CCL2, with GO and KEGG enrichment analyses suggesting enrichment in leukocyte transendothelial migration and tumor necrosis factor signaling pathways; thus, C2 cells were defined as inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs). The C6 subgroup expressed mesothelial markers (MSLN, EZR, and UPK3B) and was defined as mesothelial CAFs (mesCAFs). C7 cells are defined as antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs), which are characterized by antigen presentation and express high levels of major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II) genes (CD74, HLA-DRA, HLA-DPB1, and HLA-DQB1), with gene enrichment pathways related primarily to antigen presentation, myeloid cell activation, and MHC II-mediated antigen processing. Myofibroblastic cancer-associated fibroblasts (myCAFs) have the most complex composition, with internal gene expression and spatial distribution heterogeneity. All five myCAF subgroups (C4, C5, C8, C10, and C12) expressed high levels of the markers SERPINF1, POSTN, and THY1.16

Fig. 4.

CAFs related to iCCA metastasis.

(A) UMAP mapping of stromal cells. (B) Mapping of stromal cell-related genes in the UMAP map. (C) UMAP map of fibroblast subsets. (D) UMAP map of fibroblast subtypes (left) and mapping of metastatic lymph node (middle) and tumor (right) sample-derived cells in the UMAP map. (E) Heat map of characteristic genes of fibroblast subtypes. (F) Differences of various fibroblast proportions in different samples. (G) Distribution of five-cell subclusters of myCAFs in tumors and metastatic lymph nodes and heat map of characteristic genes. (H) THBS1 expression in five-cell subclusters of myCAFs. One-way ANOVA. (I) GO enrichment analysis of characteristic genes of C5 myCAF. (J) Representative images of α-SMA and THBS1 mIHC staining in LNM, primary tumor, and non-metastatic lymph nodes sections. Scale bar 50 μm. (K) and (L) Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival of 255 patients in the FU-iCCA cohort stratified by THBS1 protein expression level (K) and C8 myCAF score calculated by BayesPrism (L) (log-rank Mantel–Cox test). ∗∗p <0.01, ∗∗∗p <0.001, ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001. CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; GO, Gene Ontology; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; LNM, lymph node metastasis; myCAFs, myofibroblastic cancer-associated fibroblasts; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection; mIHC, multiplex immunohistochemistry.

In primary tumors and metastatic lymph nodes, more than 60% of the fibroblasts consisted of CAFs, whereas NAFs and pericytes were predominant in normal tissues (Fig. 4F). Using BayesPrism, we found that three fibroblast subtypes (mesCAFs, iCAFs, and myCAFs) were associated with poor prognosis, whereas two (vCAFs and pericytes) were associated with better prognosis in patients with FU-iCCA (Fig. S3A). Among these subgroups, C8_myCAFs were found only in metastatic lymph nodes. Compared with other myCAFs, C8_myCAFs were characterized by the upregulation of genes related to matrix restructuring, the promotion of fibroblast activation proliferation (PI16, FBLN5, HAS1, THBS1, and MFAP5), and the secretion of various cytokines (CCL2, CXCL2, CXCL12, and IL6) that mediate macrophage recruitment and promote iCCA progression (Fig. 4G). Previous studies have shown that PI16 in the metastatic lymph nodes of patients with esophageal cancer can reduce tumor cell apoptosis, conferring tumor cell resistance to cisplatin.17 MFAP5 can promote the aggressiveness of iCCA by activating the Notch pathway, and IL-6 plays a central role in the tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, proliferation, and metastasis of iCCA and is significantly associated with poor prognosis.18,19 More importantly, THBS1 can directly inhibit iCCA angiogenesis and promote tumor-associated lymphangiogenesis and LNM.20 C8 myCAFs presented the highest expression of THBS1 (Fig. 4H). KEGG functional enrichment analysis revealed that C8 myCAFs were enriched in multiple pathways, such as matrix remodeling and immune/inflammatory regulation, which may be related to their special spatial localization in the lymph nodes (Fig. 4I). These results are highly consistent with our findings, suggesting that this group of metastatic THBS1+ myCAFs can potentially promote iCCA LNM. mIHC staining confirmed that THBS1+α-SMA+ CAFs were significantly increased in metastatic lymph nodes compared with primary tumors and non-metastatic lymph nodes (Fig. 4J). In the FU-iCCA cohort, more THBS1+ CAFs and higher THBS1 protein expression in tumors were associated with shorter OS in patients (Fig. 4K and L).

iCCA epithelial cell heterogeneity

To explore the heterogeneity among 14,320 epithelial cells, we analyzed their transcriptomic profile and performed clustering analysis. The results revealed that epithelial cells can be divided into three groups according to their tissue-specific expression profiles: normal epithelial cells (N), primary tumor cells (PT), and lymph node metastatic tumor cells (LNM) (Fig. 5A). We focused on epithelial cells from PT samples and further divided them into 16 subclusters (Fig. 5A). Using inferCNV analysis, with the remaining normal cells used as a reference, we found that 16 tumor-derived epithelial cell subclusters exhibited heavy CNV burdens (Fig. 5B). To further explore the heterogeneous functions of the coexpression modules of different genes in the tumor ecosystem, we applied a non-negative factorization (NMF) matrix algorithm. After multiple permutation tests and stability and error trade-off evaluations, seven GEPs were identified (Fig. 5C and D). We used the Scissor method to identify key cell subclusters driving LNM, which leverages bulk data phenotype information to identify phenotype-associated cell subclusters.14 We utilized the transcriptomic data of 255 samples with survival information from the FU-iCCA cohort, which included 56 LN+ patients and 199 LN– patients as references. We subsequently identified LNM-associated cells (Scissor+) among the 12,784 epithelial cells (Fig. 5F). We found that Scissor+ cells expressed higher levels of GEP3 and GEP4 module genes than did Scissor- cells. Additionally, tumor cells from LNMs expressed higher levels of GEP3 and GEP4 than did those from PTs (Fig. 5F). Therefore, we performed KEGG functional enrichment analysis on genes in GEP3 and GEP4 and found that GEP3 was related mainly to immune regulation, whereas GEP4 was related mainly to cell proliferation, division, DNA repair, and cell function regulation (Fig. 5G). These two factors may affect the antitumor killing effect in lymph nodes and promote different aspects of tumor colonization and proliferation. Among all the tumor cell subclusters, C9 and C11 presented the highest expression of GEP3 and GEP4, and KEGG enrichment analysis of their characteristic genes revealed similar results (Fig. 5G). Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the seven GEPs in the FU-iCCA cohort revealed that GEP3 and GEP4 were associated with poor clinical outcomes (Fig. 5H). Interestingly, GEP3, GEP4, C9, C11, and Scissor+ cells were consistently associated with poor prognosis in the FU-iCCA cohort (Fig. 5I). Serum amyloid A1 (SAA1) expression was upregulated in C9, C11, LMN, and Scissor+ cells (Fig. 5J; Fig. S4A). SAA1 and serum amyloid A2 (SAA2, collectively referred to as SAA) are highly expressed in invasive areas near the borders of liver malignancies (including hepatocellular carcinoma and iCCA) and induce macrophage recruitment and M2 polarization through the SAA–TLR axis, leading to local immunosuppression and tumor progression.21 Therefore, we performed mIHC staining on paired PT and LNM samples (Fig. 5K). Compared with those in PTs, the proportions of PanCK and SAA1 double-positive PanCK+ cells in metastatic lymph nodes were significantly greater (Fig. 5L). SAA1 protein expression was significantly elevated in LN+ tumor samples (Fig. 5M). High expression of the SAA1 gene was associated with poor prognosis in three independent iCCA datasets, GSE107943, TCGA, and FU-iCCA (Figs. S4B–D).

Fig. 5.

The heterogeneity of iCCA tumor epithelial cells.

(A) UMAP plot of epithelial cells, color-coded by sample sources (left) and subclusters from the primary tumor (right). (B) Heat map showing the large-scale CNVs of epithelial cells from primary tumor compared with non-tumor epithelial cells. Red: amplification and blue: deletion. Epithelial cells from different subclusters and the range of different chromosomes are labeled by different color bars on the left and top to the heat map, respectively. (C) The stability and error curve of inferred GEP numbers with the range from 3 to 10, implemented by a consensus non-negative matrix factorization algorithm. The optimal number is 7. (D) Heat map showing the Euclidean distance of programs across replicates. (E) The violin plot of expression level of 7 GEPs across distinct cell clusters. (F) The mapping of cells associated with LNM identified by Scissor in the UMAP map (top) and violin plots of the expression of 7 GEPs in Scissor-positive and -negative, lymph node-derived epithelial cells and tumor-derived epithelial cells (bottom). (G) KEGG enrichment analysis of GEP3, GEP4, C9 epithelial, and C11 epithelial characteristic genes. (H) Prognostic values of 7 GEPs in the 255 patients in FU-iCCA cohort. Forest plots show Hazard Rations and horizontal ranges derived from Cox regression survival analyses for overall survival. (I) Kaplan–Meier curves for OS in 255 patients from the FU-iCCA cohort stratified according to high vs. low score of the GEP3 and GEP4 (left), C9 epithelial and C11 epithelial (middle), Scissor+ and Scissor- epithelial signatures (right) (log-rank Mantel–Cox test). (J) Venn diagram of the intersection of characteristic genes of epithelial cells from Scissor+, C9 epithelial, C11, epithelial, and LNM. (K) Representative images of SAA1 and PanCK mIHC in LNM and primary tumor sections. (L) Quantification of SAA1+ tumor cells in LNM and primary tumor lesions. (M) Levels of SAA1 protein and gene in LN+ and LN- patients in the FU-iCCA cohort (Student’s t test). ns, not significant, ∗p <0.05, ∗∗∗p <0.001. CNVs, copy number variants; GEP, gene expression program; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; LNM, lymph node metastasis; OS, overall survival; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection; mIHC, multiplex immunohistochemistry.

Differential cell communication in the metastasis-associated tumor microenvironment of iCCA

We utilized CellChat to decipher cell communication within the iCCA ecosystem. Compared with normal tissue, cell-to-cell communication between tumors and metastatic lymph nodes was more extensive and complex (Fig. 6A). Compared with matched normal tissues, PTs and LNMs share common tumor-promoting signals. Multiple tumor-promoting and immunosuppression interaction pathways, including MIF-CD74, MIF-CXCR4, MIF-IL6, MIF-VEGF, and MIF-TIGIT, were activated in both the iCCA tumor microenvironment and the LNM microenvironment (Figs. S4E and F). Tumor and stromal cells were the main signal senders and immune cells were the primary recipients. In metastatic lymph nodes, the number and strength of interactions exceeded those in primary tumors (Fig. 6A and B).

Fig. 6.

Differential cell communication in metastasis-associated tumor microenvironments of iCCA.

(A) Comparison of the differential number and strength of interactions between primary tumors and LNMs. The red line represents the number or strength of interactions that are enhanced in lymph nodes, and the blue line represents the number or strength of interactions that are reduced. (B) The scatter plot showing the strength of incoming and outgoing interactions of different cell types in LNMs and primary tumors. (C) Chord diagram of cancer-promoting signaling pathways enhanced in lymph nodes. (D) Bubble plot showing the significant ligand–receptor pairs between epithelial, macrophages and fibroblasts types calculated by CellChat. (E) Bubble chart showing the gene expression levels of SAAs receptors, including CD36, FPR1/2, TLR2, and TLR4, in the main cell types (left) and different sample types (right). (F) Correlation analysis between CD36 and SAA1 gene expression in the FU-iCCA cohort. Pearson’s correlation. (G) The mIHC staining of macrophages + Hucc9810 or macrophages + Hucc9810/siSAA1 cocultures. (H, J) Wound healing assays evaluating the migration areas of Hucc9810 cells cultured with media from macrophages + Hucc9810, macrophages + Hucc9810/siSAA1 or macrophages + Hucc9810 + SSO cocultures. One-way ANOVA. (I, K) Transwell assays. The upper well: Hucc9810 + DMEM; the lower well: media from macrophages + Hucc9810, macrophages + Hucc9810/siSAA1 or macrophages + Hucc9810 + SSO cocultures. One-way ANOVA. (L) Immunoblotting of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin, SMAD3, and α-SMA of different cells. ∗p <0.05. iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; LNM, lymph node metastasis; PT, primary tumor; mIHC, multiplex immunohistochemistry.

We analyzed cell-to-cell communication differences across normal, primary tumor, and LNM ecosystems (Fig. 6C). The APOE-Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) pathway regulates inflammation and enhances tumor proliferation, as confirmed in neurological diseases and various malignancies.22,23 The transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) communication network is multifunctional in tumors and promotes metastasis, attenuates CD8+ T cell activation, enhances myofibroblast differentiation, and enhances extracellular matrix deposition.24,25 Another significantly activated pathway in LNM is the cyclophilin A (CypA) pathway, which regulates various cell functions, such as promoting cell growth in small cell lung cancer.26,27 Importantly, previous evidence has shown that the overexpression of CypA in 68% of cholangiocarcinomas (CCAs) is related to liver fluke infection and leads to a 30–35% increase in the proliferation of CCA cell lines.28 Semaphorin 4 (SEMA4) and the CD45-mannose receptor (MR) pathway are also enhanced in LNM, probably resulting in increased monocyte recruitment and differentiation toward the M2 macrophage phenotype.29

Interactions between SAA1 and CD36, which are exclusively found in LNMs, suggest that CD36 may limit antitumor immune responses through the metabolic regulation of macrophages, influencing procarcinogenic microenvironment formation (Fig. 6D). We further focused on SAA receptors and identified CD36, TLR2, TLR4, FPR1, and FPR2 expression in macrophages (Fig. 6E). CD36 was particularly highly expressed in LNM (Fig. 6E). The transcriptomic data of the FU-iCCA cohort revealed a positive correlation between the expression of SAA1 and that of CD36 (R = 0.38, p <0.01; Fig. 6F).

To gain deeper insights into the function of SAA1-CD36 in iCCA, we cocultured macrophages with the CCA cell line Hucc9810 under the following conditions: macrophages + Hucc9810, macrophages + Hucc9810/siSAA, and macrophages + Hucc9810 + SSO, a CD36 inhibitor. Compared with that in untreated tumor cells, the expression of CD36 in macrophages was significantly lower after tumor cells with siRNA-mediated SAA1 knockdown were cocultured with macrophages (Fig. 6G). After 48 h, we extracted the conditioned media from the cocultures. Media from macrophages + Hucc9810/siSAA and macrophages + Hucc9810 + SSO significantly reduced tumor cell migration and invasion abilities, as suggested by wound healing and transwell assays (Fig. 6H–K). The levels of invasion-related proteins, including N-cadherin, vimentin, and SMAD3, increased in tumor cells cultured with media from the macrophage + Hucc9810 group (Fig. 6L). These findings revealed that the SAA1-CD36 pathway could promote tumor cell invasion and metastasis.

CD36+ macrophages interact with Tex and Treg cells to promote immunosuppression in iCCA

To further determine the mechanism by which CD36 macrophages influence lymphocytes in LNMs, we explored the interactions among the nine cell types by studying different intercellular communications in iCCA (Fig. 7A). CD36 macrophages and CD8 Texs are involved in most types of cellular communication. Additionally, the interactions of immune checkpoints, such as NECTIN2-TIGIT, CD86-CTLA4, and LGALS9-HAVCR2, with CD36+ macrophages were strong (Fig. 7B). To confirm the role of CD36+ macrophages in the iCCA immunosuppressive microenvironment, we calculated the corresponding CD36, Tex, and Treg scores via the GSVA method. In the FU-iCCA, E-MTAB6389, and TCGA cohorts, the CD36, Tex, and Treg scores were positively correlated (Fig. 7C and D). Survival analysis of the FU-iCCA cohort revealed that the Tex.score high/CD36.score high and Treg.score high/CD36.score high subgroups had the worst survival outcomes (Fig. 7E and F), indicating that CD36+ macrophages interact with Texs and Tregs and thus influence patient prognosis. We performed additional spatial analysis of the mIHC images, measuring the distances between Tex cells and Tregs and between Tex cells and CD36 macrophages (Fig. 7G). With 50 μm as the boundary, the number of Texs and Tregs around CD36+ macrophages was the greatest within 0–50 μm (Fig. 7H and I). In patients who were N1, Texs and Tregs were more closely related to CD36 macrophages than patients who were N0 (Fig. 7J and K). These results suggest that CD36 macrophages might interact with Tregs and Texs, affecting the formation of an immunosuppressive TME and the poor prognosis of patients with iCCA.

Fig. 7.

CD36 macrophages interact with Tex cells and Treg cells and promoted immunosuppression in iCCA.

(A) Cell–cell interactions among CD36 macrophages, myCAFs, and distinct T cell subtypes. (B) Immune-related ligands and receptors for signal communication between CD36 macrophages, myCAFs and distinct T cell subsets. (C) Correlation of Treg.scores with CD36+Macro.scores in iCCA from FU-iCCA, E-MTAB6389, and TCGA cohorts (Pearson’s correlation). (D) Correlation of Tex.scores with CD36+Macro.scores from the FU-iCCA, E-MTAB6389, and TCGA cohorts (Pearson’s correlation). (E) OS analysis of patients with different Treg.scores and CD36+Macro.scores from the FU-iCCA cohort (log-rank Mantel–Cox test). (F) OS analysis of distinct Tex.scores and CD36+Macro.scores from the FU-iCCA cohort (log-rank Mantel–Cox test). (G) The mIHC images of CD36+ macrophages, Tex cells, and Treg cells in iCCA tumor sections (left) and the measurement of their distance (right). Scale bar, 50 μm. (H, J) The distances and its measurement between CD36 macrophages and Treg cells (Student’s t tests). (I, K) The distances and its measurement between CD36 macrophages and Tex cells (Student’s t tests). ns, not significant, ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p <0.01, ∗∗∗∗p <0.0001. iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; mIHC, multiplex immunohistochemistry; myCAFs, myofibroblastic cancer-associated fibroblasts; OS, overall survival; Tex, exhausted T cells; Tregs, regulatory T cells.

Discussion

A systematic analysis of the iCCA TME could assist in the design of effective targeted therapy strategies. Although numerous studies have analyzed the iCCA TME from a single-cell perspective, the role of the LNM microenvironment in iCCA remains unclear. Our study provides a high-resolution landscape of tumor, immune, and stromal cells in metastatic lymph nodes, highlighting their differences from those of the primary tumor. We discovered that T cells in primary tumors express high levels of immune checkpoint genes and have a relatively high exhaustion score, consistent with the findings of previous studies indicating that proliferating CD8+ T cells in tumors predominantly exhibit an exhausted phenotype.30 These findings suggest that tumor metastasis affects antitumor immunity at the primary site by impairing the function of draining lymph nodes. Importantly, we described the composition and characteristics of the LNM microenvironment; identified several metastasis-associated cell subgroups, including SAA1+ tumor cells, CD36+ macrophages, and THBS1+ CAFs; revealed the high heterogeneity and complex cell communication in iCCA metastatic lymph nodes and tumors; and validated the differential expression and prognostic value of these subgroups in multiple cohorts.

Previous studies have demonstrated high heterogeneity within and among iCCA tumors, classifying iCCA into different subtypes according to various criteria. Bao et al.31 identified three iCCA molecular subtypes related to chromatin remodeling, metabolism, and chronic inflammation via single-cell RNA sequencing combined with multiomics analysis. Another study classified iCCA into five subtypes according to the microenvironment: classical immune, inflammatory, immune desert, liver stem cell-like, and classical.32 Song et al.6 emphasized tumor cell typing in iCCA according to tissue origin, identifying markers and molecular characteristics of the perihilar large bile duct type and peripheral small bile duct-type iCCA. Wang et al.33 presented cell subgroups and their core transcription factors in the iCCA development and progression stages in an animal model, revealing two iCCA molecular subtypes. Our study focused on the LNM status of iCCA tumor cells. We identified the gene expression program of iCCA tumor cells and characterized dual GEPs associated with lymph node metastasis related to cell proliferation and immune regulation. These findings suggest that tumor cells can respond to early metastasis to lymph nodes by altering their metastatic tendencies and immune regulatory capacities. Moreover, we identified SAA1 as a key marker for iCCA metastasis. SAA1 is associated with the occurrence and metastasis of various tumors. SAA1+ cells constitute a characteristic subpopulation of endometrial tumorigenesis.34 Increased serum SAA1 expression can also predict ovarian cancer metastasis.35 Livers with upregulated SAA1 and SAA2 expression provide a prometastatic niche for liver metastasis in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer.36 Large-scale proteomics has identified SAA1 as a marker distinguishing iCCA from other liver diseases.37 Our study revealed the role of SAA1 in iCCA metastasis, providing important clinical insights for targeting SAA1 in iCCA treatment.

Many studies have focused on the primary tumor site of the iCCA microenvironment. Zhang et al.5 used single-cell RNA sequencing to depict the transcriptomic landscape of iCCA at the cellular level for the first time, identifying major cell subtypes and describing the mechanisms of cell communication between CAFs and tumor cells that promote tumor progression. Another study on the late-stage biliary malignancy microenvironment composition revealed T cell exhaustion in late-stage tumors and described the cellular composition and functional characteristics of metastatic foci.38 However, owing to sample accessibility, this study could not distinguish between different subtypes of biliary tumors, and all iCCA samples included had no matched lymph node samples.38 Our study is the first to comprehensively analyze the iCCA metastatic microenvironment using paired primary tumor and LNM samples. Our study complements previous studies and was validated by quantitative staining of public data and cohorts. Additionally, we delved deeper into macrophages and CAFs, finding that a group of CD36+ macrophages closely interact with tumor cells and are associated with an immunosuppressive microenvironment. The overactivation of CAFs is another intriguing discovery often accompanied by tissue structural changes before lymph node function impairment. THBS1 + CAFs express high levels of myCAF markers and have high levels of proliferation- and matrix restructuring-related gene expression, indicating their significant role in disrupting the normal lymph node structure. Targeting the lymph node structural abnormalities caused by metastasis may be an important potential approach to restoring lymph node immune function.

Cell communication in iCCA paired samples is complex, and communication among cell types can differ significantly. Overall, stromal and tumor cells assume the role of signal outputs, whereas immune cells act as signal receptors. T cells are the main receptors in tumors, whereas macrophages receive the most signals in lymph nodes, indicating that macrophage communication is involved in tumor lymph node dissemination. The enriched pathways in the lymph nodes included GALECTIN, COLLAGEN, APOE, TGFβ, and SAA, involved in inducing T cell dysfunction, promoting tumor proliferation, and restructuring the microenvironment. These specific pathways may shape the unique microenvironment of iCCA metastatic lymph nodes.

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size for scRNA-seq was limited; thus, we used formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples and multiple large-scale transcriptome cohorts for validation. Second, the lack of suitable spontaneous tumorigenesis animal models limits the analysis of dynamic changes in microenvironment composition from iCCA tumorigenesis to LNM stages. Third, we omitted analyses of other distant metastatic sites. In future work, we plan to comprehensively analyze the dynamic process of tumor dissemination from the primary site to the lymph nodes and other organs. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the heterogeneity states between primary and metastatic lesions in iCCA, especially the potential role of macrophages and CAFs in LNM. Our study contributes to a deeper understanding of the mechanisms related to LNM and the development of more effective therapeutic targets in patients with iCCA.

Abbreviations

apCAFs, antigen-presenting CAFs; BSA, bovine serum albumin; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; CCAs, cholangiocarcinomas; CNVs, copy number variants; CypA, cyclophilin A; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GEP, gene expression program; GO, Gene Ontology; GSVA, gene set variation analysis; iCAFs, inflammatory CAFs; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; mIHC, Multiplex immunohistochemistry; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; LNM, lymph node metastasis; mesCAFs, mesothelial CAFs; MHC II, major histocompatibility complex II; mIHC, multiplex immunohistochemistry; MR, mannose receptor; myCAFs, myofibroblastic cancer-associated fibroblasts; N, normal epithelial cells; NAF, normal activated fibroblast; NKT, natural killer T cells; NMF, non-negative factorization; OS, overall survival; PT, primary tumor; SAA1, serum amyloid A1; SAA2, serum amyloid A2; SEMA4, Semaphorin 4; SSO, succinimidyloleate; Tactive, active CD4+ T cells; Tcm, central memory T cells; Teff, effector T cells; Tex, exhausted T cells; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TME, tumor microenvironment; TNaive, naïve T cells; Tprof. proliferating T cells; Tregs, regulatory T cells; TRMs, tissue-resident memory T cells; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection; vCAFs, vascular CAFs.

Financial support

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170646,82370644 to HH). Scientific Research Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (20214Y0087 to LM).

Authors’ contributions

Joint first authors and contributed equally to the research: ZL, LM, MC, XC. Obtained funding: HH. Designed the study: ZL, LM, HH.Collected the data: MS, ZL. Involved in data cleaning: ZL. Analyzed the data: ZL, MC. Drafted the manuscript: ZL, LM. Contributed to the interpretation of the results and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript: HH. Study guarantor: HH. Read and approved the final manuscript: all authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Footnotes

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101275.

Contributor Information

Meng Sha, Email: Simonsha23@163.com.

Hualian Hang, Email: hanghualian@shsmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Reticker-Flynn N.E., Zhang W., Belk J.A., et al. Lymph node colonization induces tumor-immune tolerance to promote distant metastasis. Cell. 2022;185:1924–1942.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoshino A., Costa-Silva B., Shen T.L., et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527:329–335. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang H., Yu D., Yang P., et al. Revealing the transcriptional heterogeneity of organ-specific metastasis in human gastric cancer using single-cell RNA Sequencing. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12 doi: 10.1002/ctm2.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan J., Xiao G., Yang C., et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote lymphatic metastasis in cholangiocarcinoma via the PDGF-BB/PDGFR-beta mediated paracrine signaling network. Aging Dis. 2024;15:369–389. doi: 10.14336/AD.2023.0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang M., Yang H., Wan L., et al. Single-cell transcriptomic architecture and intercellular crosstalk of human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1118–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song G., Shi Y., Meng L., et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis suggests two molecularly subtypes of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1642. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29164-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Job S., Rapoud D., Dos Santos A., et al. Identification of four immune subtypes characterized by distinct composition and functions of tumor microenvironment in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2020;72:965–981. doi: 10.1002/hep.31092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong L., Lu D., Chen R., et al. Proteogenomic characterization identifies clinically relevant subgroups of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:70–87.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn K.S., Kang K.J., Kim Y.H., et al. Genetic features associated with (18)F-FDG uptake in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2019;96:153–161. doi: 10.4174/astr.2019.96.4.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stuart T., Butler A., Hoffman P., et al. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell. 2019;177:1888. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031. 902.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu X., Mao Q., Tang Y., et al. Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat Methods. 2017;14:979–982. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu S.Z., Al-Eryani G., Roden D.L., et al. A single-cell and spatially resolved atlas of human breast cancers. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1334–1347. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00911-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu T., Wang Z., Pe'er D., Danko C.G. Cell type and gene expression deconvolution with BayesPrism enables Bayesian integrative analysis across bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing in oncology. Nat Cancer. 2022;3:505–517. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00356-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun D., Guan X., Moran A.E., et al. Identifying phenotype-associated subpopulations by integrating bulk and single-cell sequencing data. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40:527–538. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-01091-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin S., Guerrero-Juarez C.F., Zhang L., et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1088. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Affo S., Nair A., Brundu F., et al. Promotion of cholangiocarcinoma growth by diverse cancer-associated fibroblast subpopulations. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:866. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.03.012. 82.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang L., Zhang X., Su X., et al. Fibroblasts in metastatic lymph nodes confer cisplatin resistance to ESCC tumor cells via PI16. Oncogenesis. 2023;12:50. doi: 10.1038/s41389-023-00495-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J.H., Zhu X.X., Li F.X., et al. MFAP5 facilitates the aggressiveness of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by activating the Notch1 signaling pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:476. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1477-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou M., Na R., Lai S., et al. The present roles and future perspectives of Interleukin-6 in biliary tract cancer. Cytokine. 2023;169 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2023.156271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpino G., Cardinale V., Di Giamberardino A., et al. Thrombospondin 1 and 2 along with PEDF inhibit angiogenesis and promote lymphangiogenesis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1377–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu L., Yan J., Bai Y., et al. An invasive zone in human liver cancer identified by Stereo-seq promotes hepatocyte-tumor cell crosstalk, local immunosuppression and tumor progression. Cell Res. 2023;33:585–603. doi: 10.1038/s41422-023-00831-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obradovic A., Chowdhury N., Haake S.M., et al. Single-cell protein activity analysis identifies recurrence-associated renal tumor macrophages. Cell. 2021;184:2988–3005.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao Y., Li H., Chen J., et al. TREM-2 serves as a negative immune regulator through Syk pathway in an IL-10 dependent manner in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:29620–29634. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiang L., Hoffman M.T., Ali L.R., et al. Transforming growth factor-beta blockade in pancreatic cancer enhances sensitivity to combination chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:874. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.038. 90.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang X., Zhang G., Liang T. Cancer environmental immunotherapy: starving tumor cell to death by targeting TGFB on immune cell. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yurchenko V., Constant S., Eisenmesser E., Bukrinsky M. Cyclophilin-CD147 interactions: a new target for anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:305–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard B.A., Furumai R., Campa M.J., et al. Stable RNA interference-mediated suppression of cyclophilin A diminishes non-small-cell lung tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8853–8860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obchoei S., Weakley S.M., Wongkham S., et al. Cyclophilin A enhances cell proliferation and tumor growth of liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:102. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neufeld G., Mumblat Y., Smolkin T., et al. The role of the semaphorins in cancer. Cell Adh Migr. 2016;10:652–674. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2016.1197478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Q., Wu X., Wang Z., et al. The primordial differentiation of tumor-specific memory CD8(+) T cells as bona fide responders to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in draining lymph nodes. Cell. 2022;185:4049. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.020. 66.e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bao X., Li Q., Chen J., et al. Molecular subgroups of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma discovered by single-cell RNA sequencing-assisted multiomics analysis. Cancer Immunol Res. 2022;10:811–828. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-21-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin-Serrano M.A., Kepecs B., Torres-Martin M., et al. Novel microenvironment-based classification of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with therapeutic implications. Gut. 2023;72:736–748. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang T., Xu C., Zhang Z., et al. Cellular heterogeneity and transcriptomic profiles during intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma initiation and progression. Hepatology. 2022;76:1302–1317. doi: 10.1002/hep.32483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren X., Liang J., Zhang Y., et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis highlights origin and pathological process of human endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6300. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33982-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Y., Chen Y., Wan Q., et al. Identification of SAA1 as a novel metastasis marker in ovarian cancer and development of a graphene-based detection platform for early assessment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:16391–16406. doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-05296-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J.W., Stone M.L., Porrett P.M., et al. Hepatocytes direct the formation of a pro-metastatic niche in the liver. Nature. 2019;567:249–252. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1004-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mocan L.P., Grapa C., Craciun R., et al. Unveiling novel serum biomarkers in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a pilot proteomic exploration. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1440985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi X., Li Z., Yao R., et al. Single-cell atlas of diverse immune populations in the advanced biliary tract cancer microenvironment. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2022;6:58. doi: 10.1038/s41698-022-00300-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.