Abstract

Background

Pemetrexed is a key treatment for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and its usage is increasing. However, owing to treatment-related fatality in a patient with severe renal impairment observed during an initial clinical trial, such patients were excluded from further studies. Consequently, data on the safety and efficacy of pemetrexed in these patients are limited. This study aimed to assess the use of pemetrexed in this patient group in a clinical setting.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients with lung cancer treated with pemetrexed at Kyoto University Hospital from April 2008 to April 2023. The patients were categorized into two groups: those who received pemetrexed with platinum derivatives (n = 349) and those who received pemetrexed alone (n = 142). Both groups were further divided into creatinine clearance (CCr) > 45 and ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups, and safety and efficacy were compared between the subgroups. The correlation between renal impairment and adverse events was evaluated through chi-square test. Univariate and logistic regression analyses were used to identify the independent risk factors for severe adverse events (SAEs) related to renal impairment. We also analyzed the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) using log-rank test.

Results

A significant increase in the incidence of grade 3 or higher anemia was observed in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups of both the platinum-concomitant and pemetrexed-alone groups (p = 0.03 and p < 0.01, respectively). No significant differences were observed in other SAEs. Multivariate analysis showed that baseline hemoglobin levels were an independent predictor of grade 3 or higher anemia across both treatment groups, alongside a baseline CCr ≤ 45 mL/min in the pemetrexed-alone group. No significant differences were observed in the overall response rate, PFS, or OS between the CCr > 45 and CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups in either treatment group.

Conclusions

Although severe anemia was more common in patients with renal impairment, the efficacy of treatment did not differ, indicating that pemetrexed remains a viable treatment option for this population with proper management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-025-13785-x.

Keywords: Pemetrexed, Non-small cell lung cancer, Safety and efficacy, Renal impairment, Creatinine clearance

Background

Pemetrexed is widely used because of its relatively low toxicity profile and remarkable efficacy, particularly in patients with non-squamous non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) [1–3]. Its use in combination therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab and atezolizumab has increased [4, 5]. However, pemetrexed has safety concerns, especially in patients with renal impairment, leading to its cautious use. In a phase 1 study involving patients with solid tumors, one patient with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 19 mL/min died of treatment-related toxicity, prompting the discontinuation of inclusion of patients with a GFR < 30 mL/min [6]. Another study indicated that patients with a creatinine clearance (CCr) ≤ 45 mL/min experienced increased serum concentrations of pemetrexed and were at a higher risk of hematological toxicities [7]. Consequently, patients with renal impairment are generally excluded from clinical trials, and treatment with pemetrexed is no longer recommended in clinical practice.

However, the relatively small number of patients in previous studies and the limited data available suggest that some patients may be missing out on potentially optimal treatment. This study aimed to retrospectively evaluate the safety and efficacy of pemetrexed in combination with platinum derivatives and as a standalone treatment in a large cohort of patients with renal impairment.

Methods

Patients and clinical data

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 584 consecutive patients with NSCLC who were treated with pemetrexed in combination with platinum derivatives or as monotherapy at Kyoto University Hospital from April 2008 to April 2023. We excluded patients who initiated treatment at other hospitals or were transferred shortly after starting pemetrexed (n = 39), those who received pemetrexed as a rechallenge therapy (n = 35) or in combination with bevacizumab (n = 11), those diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma (n = 1), and those with large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma or pleomorphic carcinoma (n = 7). Finally, 491 patients were included in the final analysis. The patients were categorized into two groups: those receiving pemetrexed with platinum derivatives (n = 349) and those receiving pemetrexed alone (n = 142). Patients were further divided into CCr > 45 and ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups for safety and efficacy evaluations (Fig. 1). We used CCr to evaluate renal function because it is commonly used in clinical practice. CCr was calculated using the Cockcroft–Gault formula, as previously reported [8]. A CCr cutoff of 45 mL/min was used based on previous research linking this threshold to increased adverse events and blood concentration levels in patients with lower CCr [9] and because the use of pemetrexed in patients with CCr < 45 mL/min is not recommended in Japan. We compiled data from patient records for the final analysis, including age, sex, smoking status, performance status (PS), clinical staging, oncogenic driver mutation status, therapeutic regimens and lines, dose adjustment, blood test results, and clinical courses. Standard doses were defined as 500 mg/m2 of pemetrexed combined with either carboplatin (area under the curve, 5 or 6) or cisplatin (75 mg/m2). Dose adjustment was defined as a reduction in dosage at initiation. Baseline hemoglobin levels were assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 and were considered indicative of the baseline anemia grade. This study was approved by the Kyoto University Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number 023–00932).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patients. LCNEC, large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; CCr, creatinine clearance

Adverse events

We collected data on objectively evaluable adverse events from the clinical records, including hematological toxicities, elevated liver enzymes, infections, drug-induced pneumonitis, anorexia, elevated creatinine, skin rash, fatigue, acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease, and treatment-related deaths. The severity of these events was assessed using CTCAE version 5.0. Each adverse event was categorized into one of two groups, severe (grade 3 or higher) or non-severe, because severe adverse events (SAEs) are important in clinical practice.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were analyzed using Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Dichotomous variables were evaluated using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Multivariate analysis identified independent risk factors for adverse events that significantly varied with renal function. Factors that showed significant differences in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), with subgroup comparisons using the log-rank test. PFS was defined as the time from the initiation of pemetrexed-containing regimens until lung cancer progression, death from any cause, or end of the follow-up period. OS was calculated from the same starting point until the date of death or the end of the follow-up period. The data cutoff date was December 14, 2023. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 16 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 491 patients studied, 349 and 142 were included in the platinum-concomitant and pemetrexed-alone groups, respectively. The platinum-concomitant group had 300 and 49 patients with CCr > 45 and ≤ 45 mL/min, respectively. Meanwhile, in the pemetrexed-alone group, 99 and 43 patients had CCr > 45 and ≤ 45 mL/min, respectively. In both treatment groups, a significantly higher percentage of patients older than 75 years was observed in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup, with approximately 70% in the pemetrexed-alone group. The CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup also had more female patients. Regarding smoking status, no differences in the platinum-concomitant group was observed, whereas the ratio of never-smokers significantly increased in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup of the pemetrexed-alone group. The histopathological type, PS, oncogenic driver status, and clinical stage showed no significant differences between the groups. Regarding oncogenic drivers, 13 patients had anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion and 5 patients had ROS-1 fusion-positive lung cancer. The therapeutic lines did not significantly differ in the platinum-concomitant group. However, there was a variance in the tendency of therapeutic lines between the CCr > 45 and ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups in both treatment groups. In the platinum-concomitant group, most patients were treated with carboplatin, with only one patient receiving cisplatin in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup. There was no statistical difference in the ratio of patients on a bevacizumab-containing regimen between the CCr > 45 and CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups. The need for dose adjustment at the initiation of chemotherapies was significantly higher in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups of both treatment groups. The details of the adjusted dose and number of patients are shown in Additional Table 1. Baseline hemoglobin levels were significantly lower in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups of both groups. Specifically, in the platinum-concomitant group, the baseline hemoglobin level was 12.9 ± 1.7 g/dL in the CCr > 45 mL/min subgroup versus 11.8 ± 1.3 g/dL in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup (p < 0.01), and in the pemetrexed-alone group, it was 12.5 ± 1.7 g/dL in the CCr > 45 mL/min subgroup versus 11.6 ± 2.0 g/dL in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup (p = 0.02). Three patients in the pemetrexed-alone group and one patient in the platinum-concomitant group had baseline anemia equivalent to grade 3. The baseline CCr of the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups were statistically lower than that of the CCr > 45 mL/min subgroups in both treatment groups. Pemetrexed-based chemotherapy was initiated in patients with a CCr of 20–40 mL/min. Additional details on the distribution of patients with baseline CCr ≤ 45 mL/min are shown in Additional Fig. 1. With regard to comorbidities, we analyzed hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral vascular diseases, which can cause renal impairment. The ratio of comorbidities was significantly frequent in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup of the platinum-concomitant group, whereas no significant increase was found in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup of the pemetrexed-alone group.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Platinum-concomitant (n = 349) | Pemetrexed-alone (n = 142) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCr > 45 mL/min (n = 300) | CCr ≤ 45 mL/min (n = 49) | p | CCr > 45 mL/min (n = 99) | CCr ≤ 45 mL/min (n = 43) | p | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≥ 75 years | 21 (7.0) | 17 (34.7) | < 0.01 | 27 (27.3) | 30 (69.8) | < 0.01 |

| < 75 years | 279 (93.0) | 32 (65.3) | 72 (72.7) | 13 (30.2) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 178 (59.3) | 14 (28.6) | < 0.01 | 57 (57.6) | 15 (34.9) | 0.01 |

| Female | 122 (40.7) | 35 (71.4) | 42 (42.4) | 28 (65.1) | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never | 119 (39.7) | 25 (51.0) | 0.14 | 35 (35.4) | 24 (55.8) | 0.02 |

| Current or former | 181 (60.3) | 24 (49.0) | 64 (64.6) | 19 (44.2) | ||

| Histology | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 291 (97.0) | 48 (98.0) | 0.70 | 94 (94.9) | 41 (95.3) | 0.92 |

| NSCLC, NOS | 9 (3.0) | 1 (2.0) | 5 (5.1) | 2 (4.7) | ||

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 0 or 1 | 285 (95.0) | 45 (91.8) | 0.74 | 81 (81.8) | 34 (79.1) | 0.19 |

| 2 | 11 (3.7) | 3 (6.2) | 13 (13.2) | 9 (20.9) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Unknown | 3 (1.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Stage | ||||||

| III | 28 (9.3) | 6 (12.2) | 0.54 | 22 (22.2) | 9 (20.9) | 0.86 |

| IV | 272 (90.7) | 43 (87.8) | 77 (77.8) | 34 (79.1) | ||

| Oncogenic driver a | ||||||

| Wild type or unknownb | 168 (56.0) | 24 (49.0) | 0.36 | 75 (75.8) | 31 (72.1) | 0.65 |

| EGFR | 118 (39.3) | 22 (44.9) | 0.46 | 20 (20.2) | 11 (25.6) | 0.48 |

| Others | 14 (4.7) | 3 (6.1) | 0.67 | 4 (4.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0.60 |

| Therapeutic lines | ||||||

| First line | 214 (71.3) | 28 (57.1) | 0.05 | 27 (27.3) | 21 (48.8) | 0.01 |

| ≥ Second line | 86 (28.7) | 21 (42.9) | 72 (72.7) | 22 (51.2) | ||

| Platinum derivatives | ||||||

| Cisplatin | 36 (12.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0.01 | |||

| Carboplatin | 264 (88.0) | 48 (98.0) | ||||

| Bevacizumab | ||||||

| With | 123 (41.0) | 21 (42.9) | 0.81 | |||

| Without | 177 (59.0) | 28 (57.1) | ||||

| Dose adjustment | ||||||

| With | 25 (8.3) | 30 (61.2) | < 0.01 | 1 (1.0) | 11 (25.6) | < 0.01 |

| Without | 275 (91.7) | 19 (38.8) | 98 (99.0) | 32 (74.4) | ||

| Baseline Hb (g/dL) | 12.9 ± 1.7 | 11.8 ± 1.3 | < 0.01 | 12.5 ± 1.7 | 11.6 ± 2.0 | 0.02 |

| Grade ≥ 2 | 11 (3.7) | 2 (4.1) | 0.02 | 7 (7.1) | 10 (23.3) | 0.02 |

| Grade 1 | 13 (4.3) | 7 (14.3) | 3 (3.0) | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Within normal range | 276 (92.0) | 40 (81.6) | 89 (89.9) | 32 (74.4) | ||

| Baseline CCr (mL/min) | 67.7 ± 17.6 | 39.3 ± 4.2 | < 0.01 | 63.5 ± 15.5 | 36.6 ± 5.3 | < 0.01 |

| Comorbiditiesc | ||||||

| Yes | 83 (27.7) | 22 (44.9) | 0.02 | 43 (43.4) | 18 (41.9) | 0.86 |

| No | 217 (72.3) | 27 (55.1) | 56 (56.6) | 25 (58.1) | ||

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%)

CCr creatinine clearance, NSCLC non-small cell carcinoma, NOS not otherwise specified, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, Hb hemoglobin

aEGFR mutations in 437 patients were evaluated using the Cobas or peptide nucleic acid-locked nucleic acid polymerase chain reaction clump test. Of the 491 patients, 50 did not undergo gene mutation evaluation. Four patients were evaluated with next-generation sequencing (Oncomine CDx®☐; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion-positive cases (n = 13) were diagnosed using immunohistochemistry and fluorescent in situ hybridization. In the five patients who were c-ros oncogene 1 fusion-positive, polymerase chain reaction was used in four cases and next-generation sequencing was used in one case (Oncomine CDx®☐)

bWild type was defined as negative for EGFR mutations and other driver oncogenes if tested

cComorbidities include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral vascular diseases

To evaluate the characteristics of Cockcroft–Gault CCr, we additionally analyzed the correlation between CCr and age or body weight using simple regression analysis, in addition to the comparison of body weight, age, serum creatinine, and CCr between sexes. A negative correlation was observed between CCr and age (R2 = 0.42), whereas CCr and body weight were positively correlated (R2 = 0.43) (Additional Fig. 2). Body weight, serum creatinine, and CCr were significantly lower in female patients (Additional Table 2).

Adverse events in each group

Table 2 presents the adverse events related to blood toxicities. The difference in the incidence of grade 3 or higher neutropenia and thrombocytopenia did not reach statistical significance. However, the incidence of grade 3 or higher anemia was significantly higher in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups of both treatment groups. No significant differences in the incidence of grade 3 or higher adverse events, including elevated liver enzyme levels, skin rashes, drug-induced pneumonitis, and treatment-related deaths, were found. No cases of grade 3 or higher treatment-related creatinine elevation were observed. Two instances of treatment-related deaths were recorded. One patient in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup of the pemetrexed-alone group succumbed to drug-induced pneumonitis. Another patient in the CCr > 45 mL/min subgroup of the platinum-concomitant group died from disseminated intravascular coagulation following severe infection. In addition, with the exception of patients with grade 2 or 3 anemia at the initiation of therapy (because it is a common exclusion criterion in clinical trials), we compared the efficacy of pemetrexed-based chemotherapies between patients with and without renal impairment [3]. The frequency of only grade 3 or higher anemia was statistically higher in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup of both treatment groups (Additional Table 3).

Table 2.

Adverse events in the platinum-concomitant and pemetrexed-alone groups

| Platinum-concomitant (n = 349) | Pemetrexed-alone (n = 142) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCr > 45 mL/min (n = 300) | CCr ≤ 45 mL/min (n = 49) | p | CCr > 45 mL/min (n = 99) | CCr ≤ 45 mL/min (n = 43) | p | |

| Neutropenia | ||||||

| Grade < 3 | 211 (70.3) | 38 (77.6) | 0.29 | 79 (79.8) | 31 (72.1) | 0.32 |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 89 (29.7) | 11 (22.4) | 20 (20.2) | 12 (27.9) | ||

| Anemia | ||||||

| Grade < 3 | 268 (89.3) | 38 (77.6) | 0.03 | 93 (93.9) | 30 (69.8) | < 0.01 |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 32 (10.7) | 11 (22.4) | 6 (6.1) | 13 (30.2) | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | ||||||

| Grade < 3 | 266 (88.7) | 40 (81.6) | 0.19 | 95 (96.0) | 41 (95.3) | 0.87 |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 34 (11.3) | 9 (18.4) | 4 (4.0) | 2 (4.7) | ||

| Othersa | ||||||

| Grade < 3 | 265 (88.3) | 40 (81.6) | 0.21 | 89 (89.9) | 35 (81.4) | 0.17 |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 35 (11.7) | 9 (18.4) | 10 (10.1) | 8 (18.6) | ||

CCr creatinine clearance

a “Others” included objectively evaluable adverse events, such as elevated liver enzymes, infections, drug-induced pneumonitis, anorexia, elevated creatinine, skin rash, fatigue, acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease, or treatment-related death

Evaluation of independent risk factors of SAEs

Univariate analyses were performed for each treatment group to identify risk factors for severe anemia (Additional Table 4). In both groups, baseline anemia of grade ≥ 2 and CCr ≤ 45 mL/min were statistically significant risk factors. In addition, cisplatin treatment was associated with a significantly higher risk in the platinum-concomitant group. Subsequently, we conducted multivariate analyses adjusted for age, sex, baseline anemia grade, baseline CCr, and type of platinum derivatives (Table 3). These analyses revealed that baseline anemia of grade 2 or higher was a significant risk factor for treatment-related grade 3 or higher anemia in both treatment groups. Additionally, a baseline CCr ≤ 45 mL/min was identified as a risk factor in the pemetrexed-alone group.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis to determine risk factors of grade 3 or higher anemia

| Parameters | Platinum-concomitant (n = 349) | Pemetrexed-alone (n = 142) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| Age | ||||

| ≥ 75 years | 1.33 (0.47–3.78) | 0.59 | 0.97 (0.18–5.07) | 0.97 |

| < 75 years | Reference | Reference | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.13 (0.52–2.44) | 0.77 | 0.88 (0.19–4.14) | 0.87 |

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Baseline anemia | ||||

| Grade ≥ 2 | 15.6 (5.38–45.4) | < 0.01 | 46.2 (8.17–261) | < 0.01 |

| Grade 1 | 1.55 (0.70–3.42) | 0.28 | 0.50 (0.07–3.29) | 0.47 |

| Within normal range | Reference | Reference | ||

| Baseline CCr | ||||

| ≤ 45 mL/min | 1.91 (0.74–4.89) | 0.18 | 6.82 (1.32–35.1) | 0.03 |

| > 45 mL/min | Reference | Reference | ||

| Platinum derivatives | ||||

| Cisplatin | 0.27 (0.04–2.04) | 0.20 | ||

| Carboplatin | Reference | |||

CI confidence interval, CCr creatinine clearance

Comparison of best response, PFS, and OS according to renal function

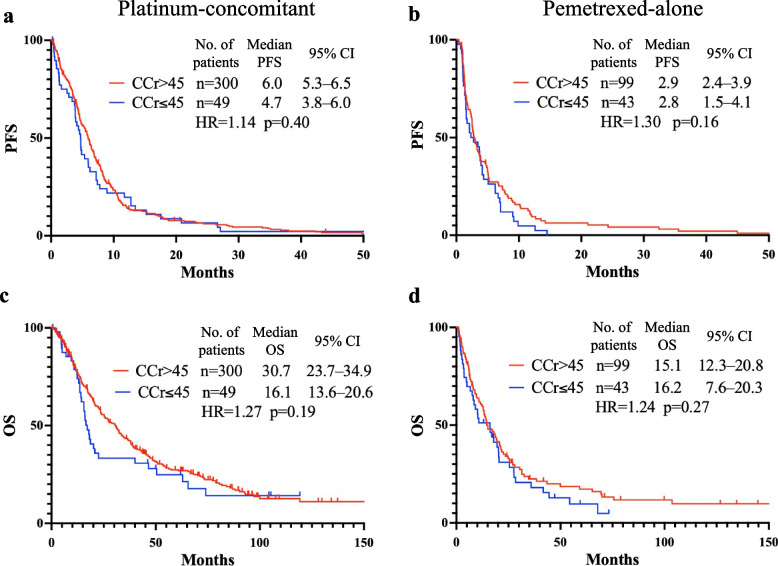

The responses to each treatment in the first and second or later lines are detailed in Table 4. The overall response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) were higher in the CCr > 45 mL/min subgroup than in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups in both treatment groups; however, the differences were not statistically significant, regardless of therapeutic lines. PFS and OS are shown in Fig. 2. In the platinum-concomitant group, the median PFSs were 6.0 months (95% CI, 5.3–6.5) for CCr > 45 mL/min and 4.7 months (95% CI, 3.8–6.0) for CCr ≤ 45 mL/min (hazard ratio [HR], 1.14; 95% CI, 0.84–1.55, p = 0.40). The median OSs were 30.7 months (95% CI, 23.7–34.9) for CCr > 45 mL/min and 16.1 months (95% CI, 13.6–20.6) for CCr ≤ 45 mL/min (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.89–1.81, p = 0.19). Although both PFS and OS were longer in the CCr > 45 mL/min group, the differences were not statistically significant. In the pemetrexed-alone group, the median PFSs were 2.9 months (95% CI, 2.4–3.9) for CCr > 45 mL/min and 2.8 months (95% CI, 1.5–4.1) for CCr ≤ 45 mL/min (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.90–1.88, p = 0.16). The median OSs were 15.1 months (95% CI, 12.3–20.8) for CCr > 45 mL/min and 16.2 months (95% CI, 7.6–20.3) for CCr ≤ 45 mL/min (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.84–1.83, p = 0.27). Furthermore, PFS and OS comparisons showed no statistically significant differences when the therapeutic line was divided into first and second or later (Additional Fig. 3). No statistical differences in ORR and DCR depending on renal function were observed when patients with grade 2 anemia at the initiation of chemotherapy were excluded (Additional Table 5). Moreover, the median PFS and OS did not differ significantly between patients with grade 2 or 3 anemia at enrollment (Additional Fig. 4).

Table 4.

Efficacy of pemetrexed-containing chemotherapies

| Best response | Platinum-concomitant (n = 349) | Pemetrexed-alone (n = 142) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCr > 45 mL/min | CCr ≤ 45 mL/min | p | CCr > 45 mL/min | CCr ≤ 45 mL/min | p | |

| First linea | n = 193 | n = 27 | n = 27 | n = 19 | ||

| ORR | 104 (53.9) | 11 (40.7) | 0.20 | 8 (29.6) | 2 (10.5) | 0.11 |

| DCR | 175 (90.7) | 24 (88.9) | 0.77 | 18 (66.7) | 12 (63.2) | 0.81 |

| CR | 3 (1.6) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| PR | 101 (52.3) | 10 (37.0) | 7 (26.0) | 2 (10.5) | ||

| SD | 71 (36.8) | 13 (48.2) | 10 (37.0) | 10 (52.6) | ||

| PD | 18 (9.3) | 3 (11.1) | 9 (33.3) | 7 (36.9) | ||

| Second or later lineb | n = 78 | n = 18 | n = 71 | n = 20 | ||

| ORR | 30 (38.5) | 5 (27.8) | 0.39 | 13 (18.3) | 5 (25.0) | 0.52 |

| DCR | 55 (70.5) | 12 (66.8) | 0.75 | 48 (67.6) | 12 (60.0) | 0.53 |

| CR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| PR | 30 (38.5) | 5 (27.8) | 13 (18.3) | 5 (25.0) | ||

| SD | 25 (32.0) | 7 (38.9) | 36 (50.7) | 7 (35.0) | ||

| PD | 23 (29.5) | 6 (33.3) | 22 (31.0) | 8 (40.0) | ||

CCr creatinine clearance, ORR overall response rate, DCR disease control rate, CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease

aTwenty-three patients in the platinum-concomitant group and two patients in the pemetrexed-alone group were excluded from the ORR and DCR analyses because their responses were not evaluable

bTen patients in the platinum-concomitant group and three patients in the pemetrexed-alone group were excluded from the ORR and DCR analyses because their responses were not evaluable

Fig. 2.

Comparison of progression-free and overall survival according to renal function. Progression-free survival in the platinum-concomitant (a) and pemetrexed-alone groups (b). Overall survival in the platinum-concomitant (c) and pemetrexed-alone groups (d). CCr, creatinine clearance. No., number; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

Discussion

This comprehensive retrospective study evaluated the safety and efficacy of pemetrexed-containing chemotherapy in patients with renal impairment. Regarding safety, grade 3 or higher anemia was significantly more frequent in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups. Higher grades of baseline anemia in both treatment groups and a baseline CCr ≤ 45 mL/min in the pemetrexed-alone group were identified as independent risk factors for treatment-related severe anemia. Regarding efficacy, there were no significant differences between the CCr > 45 and CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups in both the platinum-concomitant and pemetrexed-alone groups.

A plausible explanation for the notable frequency of treatment-related severe anemia in the CCr < 45 mL/min subgroups is that chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression may be exacerbated in patients with renal impairment. Myelosuppression is a common complication of chemotherapy, and previous clinical trials have reported rates of grade 3 or higher anemia between 1.1% and 6.4% [3, 10–12]. Compared with these studies, the incidence of severe anemia in our study was higher, with approximately 20%–30% of patients in the CCr < 45 mL/min subgroups of both treatment groups experiencing grade 3 or higher anemia. One study showed that 22% of patients with CCr < 45 mL/min had grade 3 or higher anemia, indicating that renal impairment is a risk factor for severe hematological toxicity [7]. These findings are consistent with our results, suggesting that increased myelosuppression related to chemotherapy can lead to severe treatment-related anemia in patients with renal impairment.

Lower baseline hemoglobin levels and treatment-related severe anemia may be associated with poor renal function. Our study identified a higher baseline anemia grade as an independent risk factor for treatment-related grade 3 or higher anemia in both treatment groups. Multivariate analyses further revealed that a lower baseline CCr was also an independent risk factor for severe anemia, but only in the pemetrexed-alone group. However, its effect was less significant than that of grade 2 or higher baseline anemia. Meanwhile, a lower CCr was not an independent risk factor for severe anemia in the platinum-concomitant group. However, univariate analysis indicated that treatment-related severe anemia was significantly more common in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup (P = 0.02), even in the platinum-concomitant group. The link between anemia and impaired renal function is likely due to renal anemia, which is commonly observed in patients with chronic kidney disease. Several studies have reported that the prevalence of renal anemia increases in patients with renal impairment, specifically with creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL or CCr < 20–35 mL/min. This increase is often attributed to the reduced production of hematopoietic factors in the kidneys or decreased responsiveness in the bone marrow [13–15]. Renal anemia is particularly prevalent in patients with CCr < 45 mL/min, particularly those with diabetic nephropathy [16]. Indeed, our study found significantly lower baseline hemoglobin levels in the CCr < 45 mL/min subgroup. Drawing on existing research on the relationship between treatment-related severe anemia and renal impairment, it is evident that both baseline and treatment-related anemia are influenced by renal function [7].

Dose adjustment during chemotherapy may be crucial in reducing the incidence of SAEs. A study in which pemetrexed was administered with dose reduction based on renal function reported no SAEs [7]. In our study, a relatively high proportion of patients underwent dose adjustments at initiation, including dose reduction and treatment postponement, at the physician’s discretion. These findings suggest that pemetrexed is relatively safe, even in patients with renal impairment.

The efficacy of pemetrexed-containing chemotherapy appears to be independent of the renal function. In both treatment groups in our study, the ORR and DCR, in addition to PFS and OS, were not significantly different, regardless of renal function. These results are comparable to or better than those previously reported. For example, a previous study noted an ORR of 9.1%, a DCR of 54.9%, a median PFS of 2.9 months, and a median OS of 8.3 months [1]. Another clinical trial reported a median PFS and OS of 4.8 and 10.3 months, respectively [3]. The Keynote-189 clinical trial documented in the control arm an ORR of 18.9%, a DCR of 70.4%, a median PFS of 4.9 months, and a median OS of 10.6 months [4]. The median PFS in our study was similar to that of previous findings. However, the ORR, DCR, and median OS in our study were notably higher, even in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups, than those in earlier studies. These results indicate that renal function does not influence the efficacy of pemetrexed-containing treatments.

Patient characteristics such as sex and age were significantly different in this study. A possible explanation for the difference in age between the two CCr subgroups is the difference in the prevalence of lung cancer depending on age. Consistent with another study that found a higher proportion of older patients with CCr ≤ 45 mL/min [17], it is logical that a significant portion of the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups in our study comprised older individuals, reflecting the increased prevalence of lung cancer in the older population. The reason why older female patients were significantly common in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups may be explained by the characteristics of CCr. Older female patients tended to have lower serum creatinine level, which is related to lower body weight and muscle mass. In such a population, CCr calculated using the Cockcroft–Gault formula might be overestimated, compared with CCr calculated using creatinine measured from urine storage [18]. However, a previous report revealed that female patients have a lower CCr than their counterparts, and older patients showed the same trend, regardless of their body weight [19]. Our findings revealed the approximately 70% of the patients in the CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroup were female, and this trend aligns with that of a previous report [20]. Moreover, we observed that CCr calculated using the Cockcroft–Gault formula was negatively and positively correlated with age and body weight, respectively (Additional Fig. 2), which is consistent with a previous report [19]. In addition, female patients had lower body weight, serum creatinine, and CCr than male patients (Additional Table 3). Taken together, the CCr of older female patients may be evaluated as lower, although the CCr calculated using the Cockcroft–Gault formula tended to be overestimated compared with that calculated by other methods. These might be the reasons for the disparities in sex and age in the patient characteristics.

Our study did not include patients treated with recent standard therapies combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors, but our findings support the use of pemetrexed-containing therapies in patients with renal impairment. The safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor-combined therapies for patients with renal impairment have not been clarified. A recent integrated analysis of the safety and efficacy of IMpower130 and IMpower132 revealed no evident changes in the safety profile and efficacy of patients treated with or without atezolizumab, regardless of their relatively lower renal function [21], but this report did not treat patients with CCr ≤ 45 mL/min; hence, further investigation of the safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with renal impairment is needed.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study conducted at a single institution, and there was an imbalance in patient characteristics such as age and sex. Consequently, the confounding factors that may affect the safety and efficacy of pemetrexed-containing therapies should not be ruled out. Efforts were made to adjust for the effects of these imbalances using multivariate analysis. Second, the number of patients with CCr ≤ 45 mL/min was relatively small, which might not sufficiently assess the purpose of this study. Furthermore, the study did not include patients receiving the current mainstream treatment for lung cancer, platinum-derivative-based chemotherapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors, owing to the limited number of patients with renal impairment. Further large-scale studies are needed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these therapies in patients with renal impairment.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the safety and efficacy of pemetrexed-containing treatments in patients with renal impairment. Although the incidence of grade 3 or higher anemia was higher in patients with CCr ≤ 45 mL/min, no difference in treatment efficacy was observed. Therefore, pemetrexed-containing treatment is a possible choice for patients with renal impairment, but clinicians should pay close attention to treatment-related severe anemia.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Additional Table 1. Distribution of patients who underwent pemetrexed dose adjustment at chemotherapy initiation. CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 2: Additional Table 2. Comparison of body weight, age, serum creatinine, and CCr between sexes. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 3: Additional Table 3. Adverse events in the platinum-concomitant and pemetrexed-alone groups, excluding patients with grade 2 anemia at treatment initiation. Values are presented as n (%). a“Others” include objectively evaluable adverse events, such as elevated liver enzymes, infections, drug-induced pneumonitis, anorexia, elevated creatinine, skin rash, fatigue, acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease, or treatment-related death. CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 4: Additional Table 4. Univariate analysis of each parameter involved in grade 3 or higher anemia. Baseline anemia was significantly different in both treatment groups, whereas baseline CCr was significantly different only in the pemetrexed-alone group. The platinum-concomitant group showed a significant difference in the type of platinum derivatives used. aNo patient with NSCLC, NOS (n = 7) experienced grade 3 or higher anemia. bComorbidities include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral vascular diseases. CI, confidence interval; NSCLC, non-small cell carcinoma; NOS, not otherwise specified; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 5: Additional Table 5. Efficacy of pemetrexed-containing chemotherapy, excluding patients with grade 2 anemia at treatment initiation. Values are presented as n (%). aTwenty-one patients in the platinum-concomitant group and one patient in the pemetrexed-alone group were excluded from the ORR and DCR analyses because their responses were not evaluable. bTen patients in the platinum-concomitant group and two patients in the pemetrexed-alone group were excluded from the ORR and DCR analyses because their responses were not evaluable. CCr, creatinine clearance; ORR, overall response rate; DCR, disease control rate.

Supplementary Material 6: Additional Fig. 1. Distribution of patients with CCr ≤ 45 mL/min. Histogram showed the number of patients with CCr ≤ 45 mL/min in both treatment groups. CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 7: Additional Fig. 2. Correlation between CCr and age or body weight evaluated by simple regression analysis. Correlation between CCr and (a) age and (b) body weight in male patients. Correlation with CCr and (c) age and (d) body weight in female patients. CCr, creatinine clearance; BW, body weight.

Supplementary Material 8: Additional Fig. 3. Comparison of progression-free and overall survival of first-line and second-or-later-line chemotherapies between the CCr > 45 min and CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups. Progression-free (a) and overall survival (b) of first-line treatment in the pemetrexed-alone group. Progression-free (c) and overall survival (d) of second-or-later line treatment in the pemetrexed-alone group. Progression-free (e) and overall survival (f) of first-line treatment in the platinum-concomitant group. Progression-free (g) and overall survival (h) of second-or-later line treatment in the platinum-concomitant group. CCr, creatinine clearance; No., number; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Supplementary Material 9: Additional Fig. 4. Comparison of progression-free and overall survival according to renal function, except in patients with grade 2 anemia at chemotherapy initiation. Progression-free survival in the platinum-concomitant (a) and pemetrexed-alone groups (b). Overall survival in the platinum-concomitant (c) and pemetrexed-alone groups (d). CCr, creatinine clearance; No., number; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language editing.

Abbreviations

- CCr

Creatinine clearance

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- CI

Confidence interval

- DCR

Disease control rate

- GFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- HR

Hazard ratio

- NCSLC

Non-squamous non-small cell lung carcinoma

- ORR

Overall response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PS

Performance status

- SAEs

Severe adverse events

Author’s contributions

Y.S. contributed to the data curation, investigation, validation, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, and writing of the original draft. H.Y. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, funding acquisition, supervision, validation, and writing (review and editing). T.H. and H.O. contributed to the funding acquisition, supervision, validation, writing, review, and editing. K.S., H.A., and T.N. contributed to the data curation, resource acquisition, investigation, writing, reviewing, and editing. K.H., H.Y., K.H., and T.F. contributed to formal analysis, data curation, investigation, and writing (review and editing). All authors contributed to the resources, writing (review), and editing, and have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by internal funding from the Kyoto University Hospital.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at Kyoto University.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Kyoto University Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number 023–00932). The requirement for informed consent for the use of clinical records was waived due to the retrospective study design. However, all patients were guaranteed opportunities to learn about the study and withdraw from it through notification.

Consent for publication

The requirement for informed consent to use clinical information was waived because this was a retrospective study without intervention or preserved specimens.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, Pereira JR, De Marinis F, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scagliotti G, Hanna N, Fossella F, Sugarman K, Blatter J, Peterson P, et al. The differential efficacy of pemetrexed according to NSCLC histology: a review of two phase III studies. Oncologist. 2009;14:253–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2078–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishio M, Barlesi F, West H, Ball S, Bordoni R, Cobo M, et al. Atezolizumab Plus Chemotherapy for first-line treatment of nonsquamous NSCLC: results from the randomized Phase 3 IMpower132 trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:653–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mita AC, Sweeney CJ, Baker SD, Goetz A, Hammond LA, Patnaik A, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of pemetrexed administered every 3 weeks to advanced cancer patients with normal and impaired renal function. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:552–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill J, Vargo C, Smith M, Streeter J, Carbone DP. Safety of dose-reduced pemetrexed in patients with renal insufficiency. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019;25:1125–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Rouw N, Boosman RJ, Huitema ADR, Hilbrands LB, Svensson EM, Derijks HJ, et al. Rethinking the application of pemetrexed for patients with renal impairment: a pharmacokinetic analysis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021;60:649–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paz-Ares LG, de Marinis F, Dediu M, Thomas M, Pujol JL, Bidoli P, et al. PARAMOUNT: final overall survival results of the phase III study of maintenance pemetrexed versus placebo immediately after induction treatment with pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scagliotti GV, Gridelli C, de Marinis F, Thomas M, Dediu M, Pujol JL, et al. Efficacy and safety of maintenance pemetrexed in patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer following pemetrexed plus cisplatin induction treatment: a cross-trial comparison of two phase III trials. Lung Cancer. 2014;85:408–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barlesi F, Scherpereel A, Rittmeyer A, Pazzola A, Ferrer Tur N, Kim JH, et al. Randomized phase III trial of maintenance bevacizumab with or without pemetrexed after first-line induction with bevacizumab, cisplatin, and pemetrexed in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAPERL (MO22089). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3004–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakim RM, Lazarus JM. Biochemical parameters in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1988;11:238–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandra M, Clemons GK, McVicar MI. Relation of serum erythropoietin levels to renal excretory function: evidence for lowered set point for erythropoietin production in chronic renal failure. J Pediatr. 1988;113:1015–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGonigle RJ, Boineau FG, Beckman B, Ohene-Frempong K, Lewy JE, Shadduck RK, et al. Erythropoietin and inhibitors of in vitro erythropoiesis in the development of anemia in children with renal disease. J Lab Clin Med. 1985;105:449–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locatelli F, Aljama P, Bárány P, Canaud B, Carrera F, Eckardt KU, et al. Revised European best practice guidelines for the management of anaemia in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(Suppl 2):ii1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ando Y, Hayashi T, Ujita M, Murai S, Ohta H, Ito K, et al. Effect of renal function on pemetrexed-induced haematotoxicity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:183–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otani T, Kase Y, Kunitomo K, Shimooka K, Kawazoe K, Sato Y, et al. What is the correct adjustment protocol for serum creatinine value to reflect renal function in bedridden elderly patients? Jpn J Nephrol Pharmacother. 2018;7:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira A, Lapa R, Vale N. A retrospective study comparing creatinine clearance estimation using different equations on a population-based cohort. Math Biosci Eng. 2021;18:5680–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutluk Cenik B, Sun H, Gerber DE. Impact of renal function on treatment options and outcomes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;80:326–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishio M, Watanabe S, Udagawa H, Aragane N, Nakagawa Y, Kobayashi Y, et al. Integrated analysis of older adults and patients with renal dysfunction in the IMpower130 and IMpower132 randomized controlled trials for advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2024;196:107859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Additional Table 1. Distribution of patients who underwent pemetrexed dose adjustment at chemotherapy initiation. CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 2: Additional Table 2. Comparison of body weight, age, serum creatinine, and CCr between sexes. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 3: Additional Table 3. Adverse events in the platinum-concomitant and pemetrexed-alone groups, excluding patients with grade 2 anemia at treatment initiation. Values are presented as n (%). a“Others” include objectively evaluable adverse events, such as elevated liver enzymes, infections, drug-induced pneumonitis, anorexia, elevated creatinine, skin rash, fatigue, acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease, or treatment-related death. CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 4: Additional Table 4. Univariate analysis of each parameter involved in grade 3 or higher anemia. Baseline anemia was significantly different in both treatment groups, whereas baseline CCr was significantly different only in the pemetrexed-alone group. The platinum-concomitant group showed a significant difference in the type of platinum derivatives used. aNo patient with NSCLC, NOS (n = 7) experienced grade 3 or higher anemia. bComorbidities include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral vascular diseases. CI, confidence interval; NSCLC, non-small cell carcinoma; NOS, not otherwise specified; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 5: Additional Table 5. Efficacy of pemetrexed-containing chemotherapy, excluding patients with grade 2 anemia at treatment initiation. Values are presented as n (%). aTwenty-one patients in the platinum-concomitant group and one patient in the pemetrexed-alone group were excluded from the ORR and DCR analyses because their responses were not evaluable. bTen patients in the platinum-concomitant group and two patients in the pemetrexed-alone group were excluded from the ORR and DCR analyses because their responses were not evaluable. CCr, creatinine clearance; ORR, overall response rate; DCR, disease control rate.

Supplementary Material 6: Additional Fig. 1. Distribution of patients with CCr ≤ 45 mL/min. Histogram showed the number of patients with CCr ≤ 45 mL/min in both treatment groups. CCr, creatinine clearance.

Supplementary Material 7: Additional Fig. 2. Correlation between CCr and age or body weight evaluated by simple regression analysis. Correlation between CCr and (a) age and (b) body weight in male patients. Correlation with CCr and (c) age and (d) body weight in female patients. CCr, creatinine clearance; BW, body weight.

Supplementary Material 8: Additional Fig. 3. Comparison of progression-free and overall survival of first-line and second-or-later-line chemotherapies between the CCr > 45 min and CCr ≤ 45 mL/min subgroups. Progression-free (a) and overall survival (b) of first-line treatment in the pemetrexed-alone group. Progression-free (c) and overall survival (d) of second-or-later line treatment in the pemetrexed-alone group. Progression-free (e) and overall survival (f) of first-line treatment in the platinum-concomitant group. Progression-free (g) and overall survival (h) of second-or-later line treatment in the platinum-concomitant group. CCr, creatinine clearance; No., number; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Supplementary Material 9: Additional Fig. 4. Comparison of progression-free and overall survival according to renal function, except in patients with grade 2 anemia at chemotherapy initiation. Progression-free survival in the platinum-concomitant (a) and pemetrexed-alone groups (b). Overall survival in the platinum-concomitant (c) and pemetrexed-alone groups (d). CCr, creatinine clearance; No., number; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at Kyoto University.